1. Introduction

Burnout syndrome is considered by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) to be the result of chronic stress in the workplace that has not been successfully managed and is characterized by feelings of exhaustion or lack of energy as well as increased distance mental work or negativism and reduced professional efficiency [

1].

In their working lives, healthcare professionals are highly exposed to constant stress conditions due to caring for life-threatening patients, whether in emergency services, hospitalization or intensive care units. The spread of the disease caused by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has exacerbated the global response of health systems and frontline health professionals, as it is a new health event (uncertainty). It has high transmissibility and a high mortality and morbidity rate.

Evaluating the prevalence of burnout according to the indicators of the Maslach Inventory [

2] (Emotional Exhaustion EA, Depersonalization D and Personal Realization RP) among health professionals, doctors or nurses before or during the COVID-19 pandemic is essential for understanding the impact of burnout. burnout in health professionals, doctors or nurses and implement early detection and timely intervention strategies on a large scale in health organizations. The objective of this review of reviews and meta-analyses was to evaluate whether there was a change (increase or reduction) in the prevalence of burnout caused by the COVID-19 pandemic among health professionals, doctors or nurses. The aim was to evaluate the prevalence of burnout in healthcare personnel, doctors and nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is a review of reviews on the prevalence of professional burnout syndrome in healthcare personnel, doctors and nurses before or during the COVID-19 pandemic, without language or date restrictions. The protocol of this research was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) CRD42021283389 platform, and a literature search was carried out in the electronic databases of the Cochrane Library, PubMed/MEDLINE and Web of Science using controlled and noncontrolled terms. controlled for burnout and health professionals.

Rayyan (Intelligent Systematic Review) software was used as a collaborative tool for free-to-use systematic reviews.

The inclusion criteria for systematic reviews of health workers, doctors or nurses were as follows: prevalence of disease according to the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) in each of its three dimensions, namely, emotional exhaustion (EA), depersonalization (DP) and personal realization (PR). The search was carried out without a date or language restriction until October 27, 2023.

Data collection and analysis

Four reviewers screened the publications according to the selection criteria and analyzed the data independently. Two authors developed the “summary of results” tables. The fixed effects prevalence meta-analysis model was used to combine the data, taking into account that the studies estimated the same result (prevalence of burnout according to the MBI subscale) and random effects when the I2 showed heterogeneity. The effect of heterogeneity or I2 was estimated, and the results correspond to the prevalence according to the subscale of the MBI.

Finally, the Critical Appraisal Tool for Systematic Review of Healthcare Interventions (AMSTAR 2) was used as a critical evaluation tool for the systematic reviews of the studies included in this research. It is a questionnaire that contains 16 domains, 7 of which are critical with four levels of confidence: high, moderate, low and critically low; simple response options: “yes”, when the result is positive; “no”, when the standard was not met or there is insufficient information to respond; and “yes partial”, when there was partial adherence to the standard [

3].

3. Results

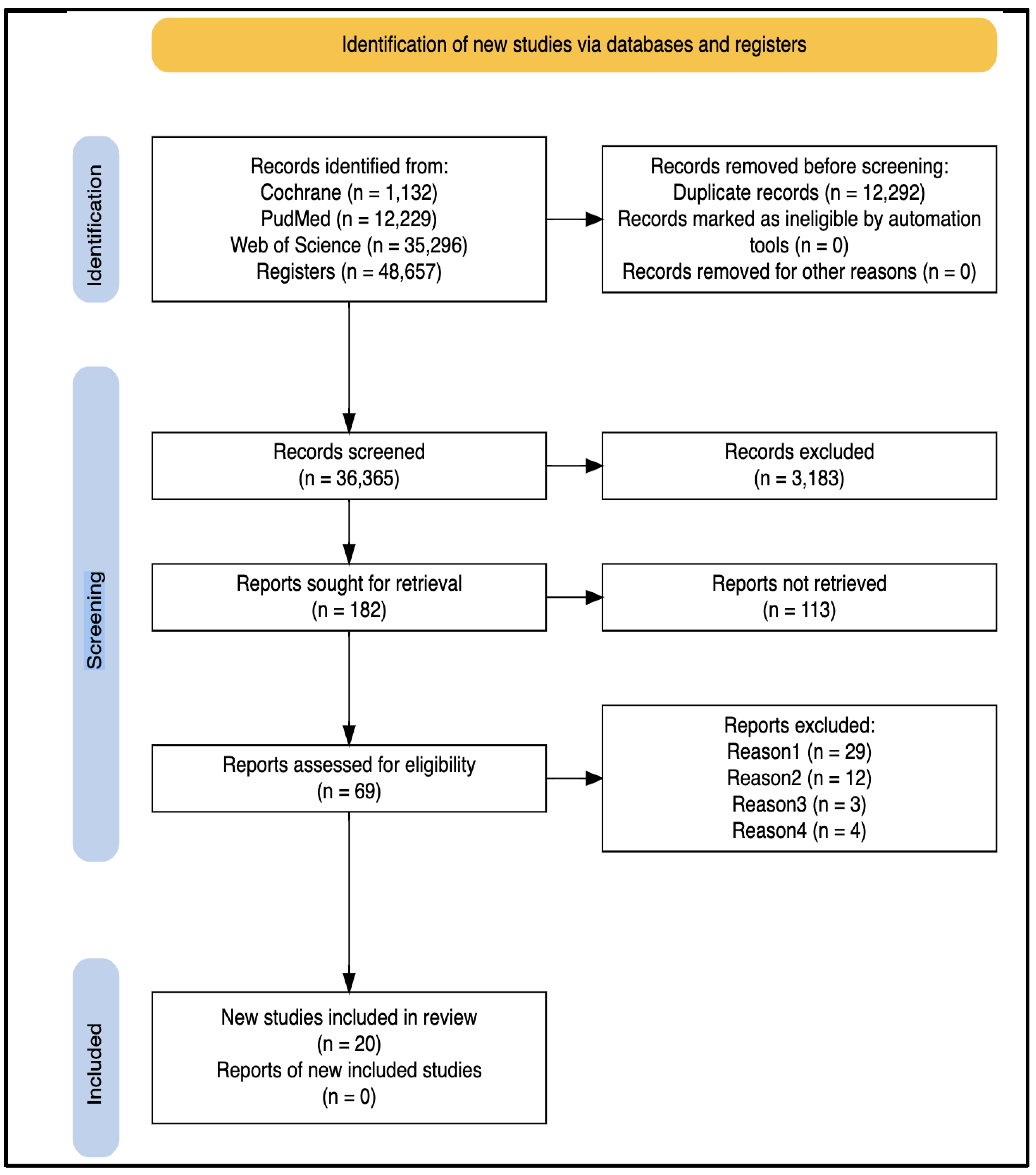

When performing the literature search, a total of 48,657 articles and 12,296 duplicates were obtained. The search was carried out through October 27, 2023, without language or date restrictions.

The population (health professional profile), sample, number of studies, measurement instruments and prevalence of burnout were extracted in an Excel spreadsheet, and the data were disaggregated by subscale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) [

2]. After a complete review of the 59 articles, only 20 articles and their respective subscales of depersonalization, emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment on the MBI for healthcare personnel, doctors and nurses were included in the review (

Figure 1 and

Table 1).

Among the results of the 20 selected articles, 7% included nurses in their study population, 72% included interviewed doctors from different specialties, and the remaining 21% reported data on healthcare personnel as a whole (

Table 1). Overall, 45% of the articles were published from 2019 onward, and the remaining 55% were published from 2020 onward (

Table 3). Moreover, of the 20 articles, 233,087 professionals were distributed across 624 studies, and the sample sizes ranged between 361 and 109,628 participants. See

Table 2.

When the studies in the prepandemic period (before 2019) and the pandemic period (after 2019) due to COVID-19 were compared, 11 of the 20 articles were identified to have been published during the pandemic period (2020-2022); however, of these, only one article contained studies carried out during the pandemic, while the other articles, despite being published in 2022, compiled research developed before the pandemic.

Consequently, and for the purposes of this research, the 20 articles selected for meeting the inclusion criteria for the review were taken into account; however, only 18 of the 20 publications were included in the meta-analysis because two articles, one published in 2022 and another in 2014, had the mean value of each MBI subscale but not the percentage, which is why they were excluded from the meta-analysis.

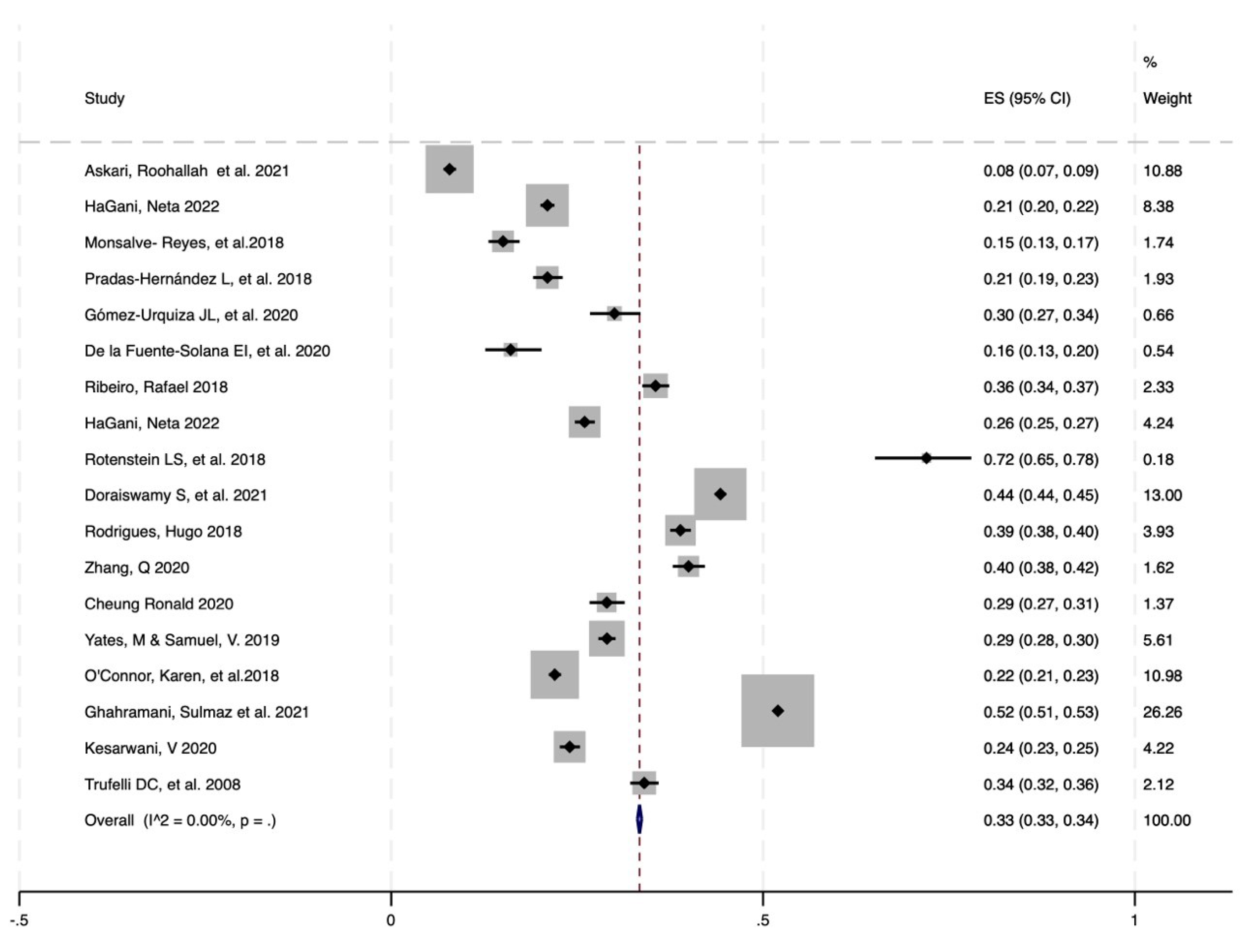

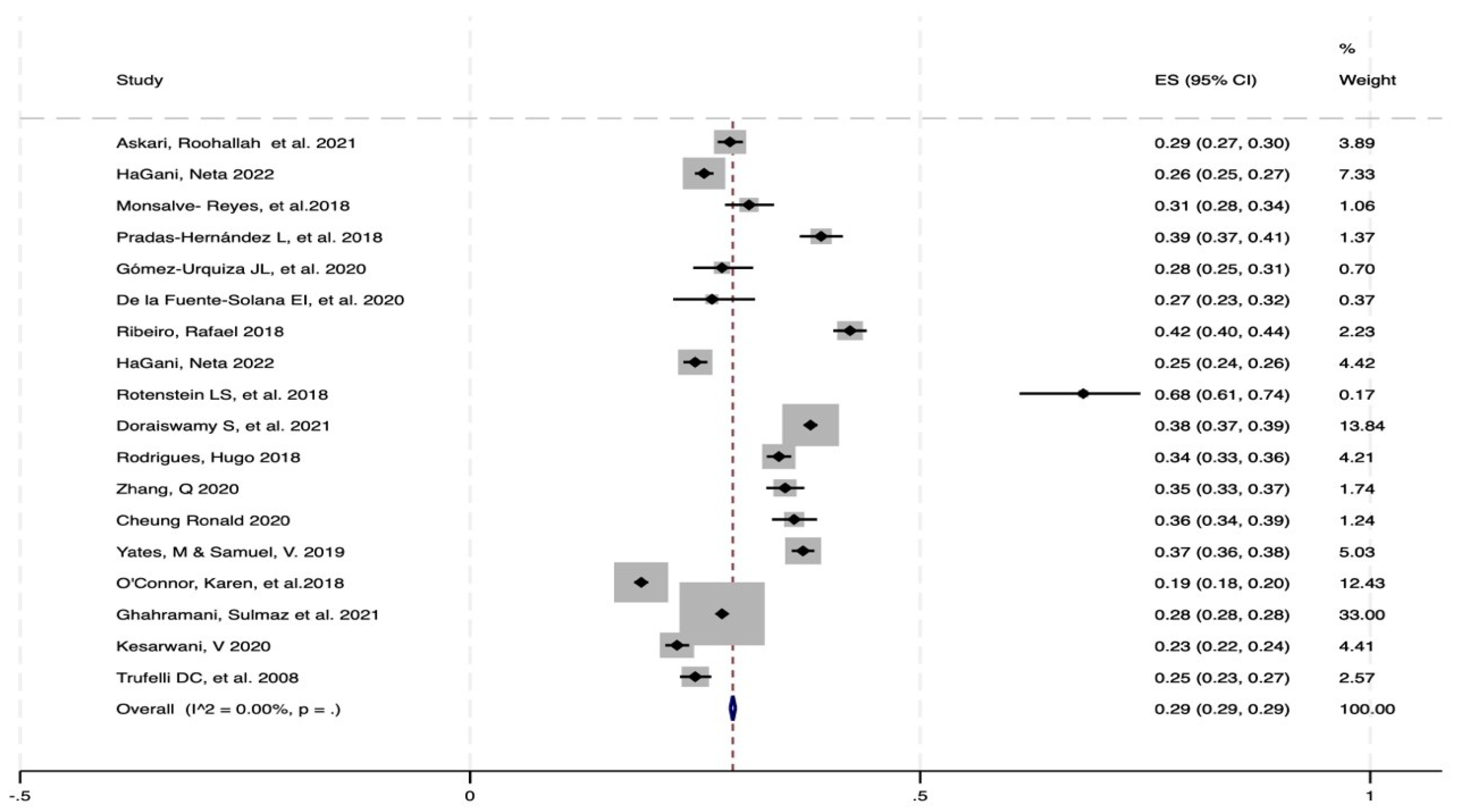

Regarding the prevalence of depersonalization (DP), 18 articles were included in the meta-analysis, and low heterogeneity (I2) was found (0%), with a prevalence of 33% and a confidence interval (CI) between 33% and 34% (

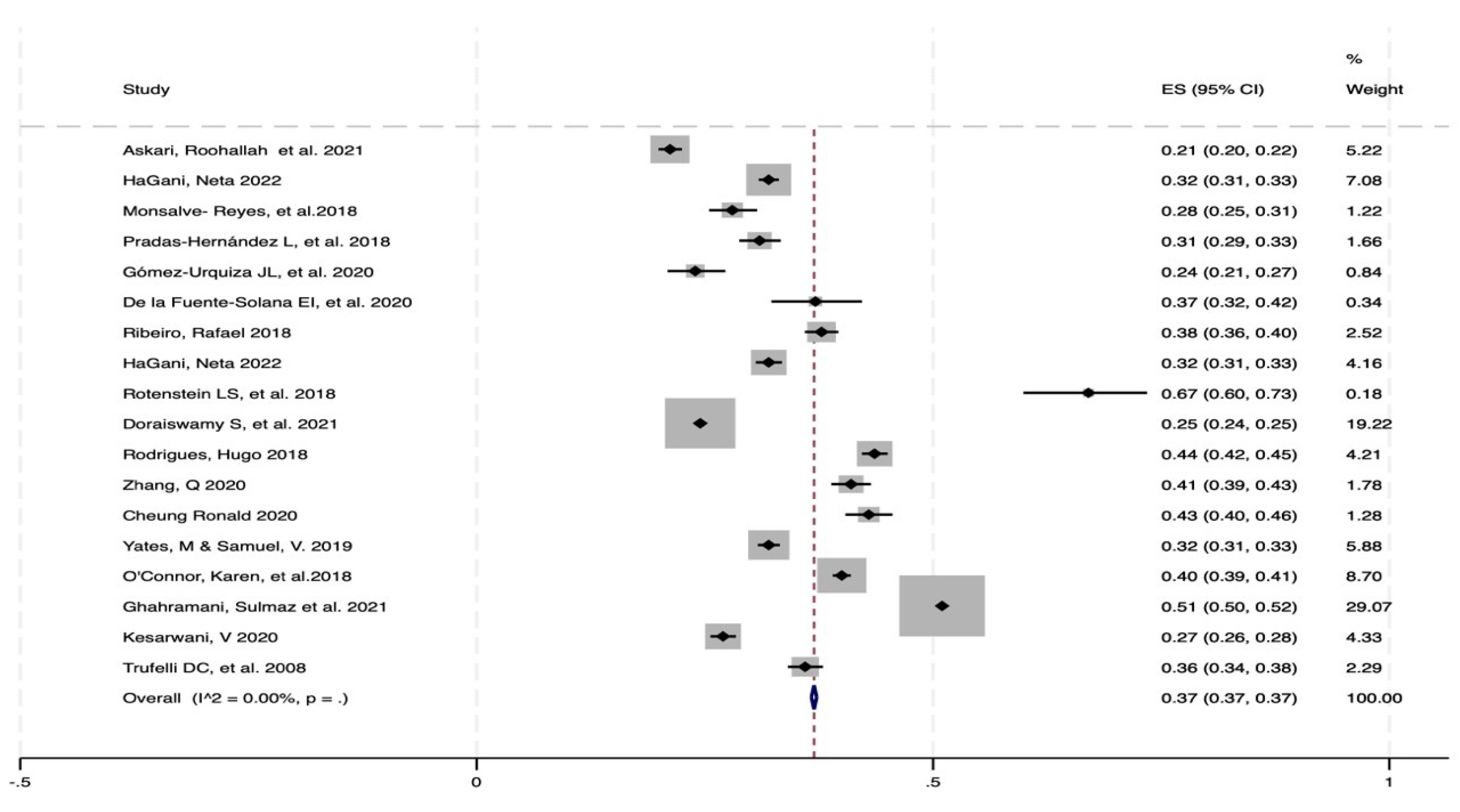

Figure 2). In the Emotional Exhaustion (EA) scale, 18 items were included, for which a low I2 (0%) was found, for a prevalence of 37% and a CI of 37%; see

Figure 3. Among the Personal Realization Scale (PR) scores, 18 were included; these included a low I2 (0%), a prevalence of 29% and a CI of 29% (

Figure 4)

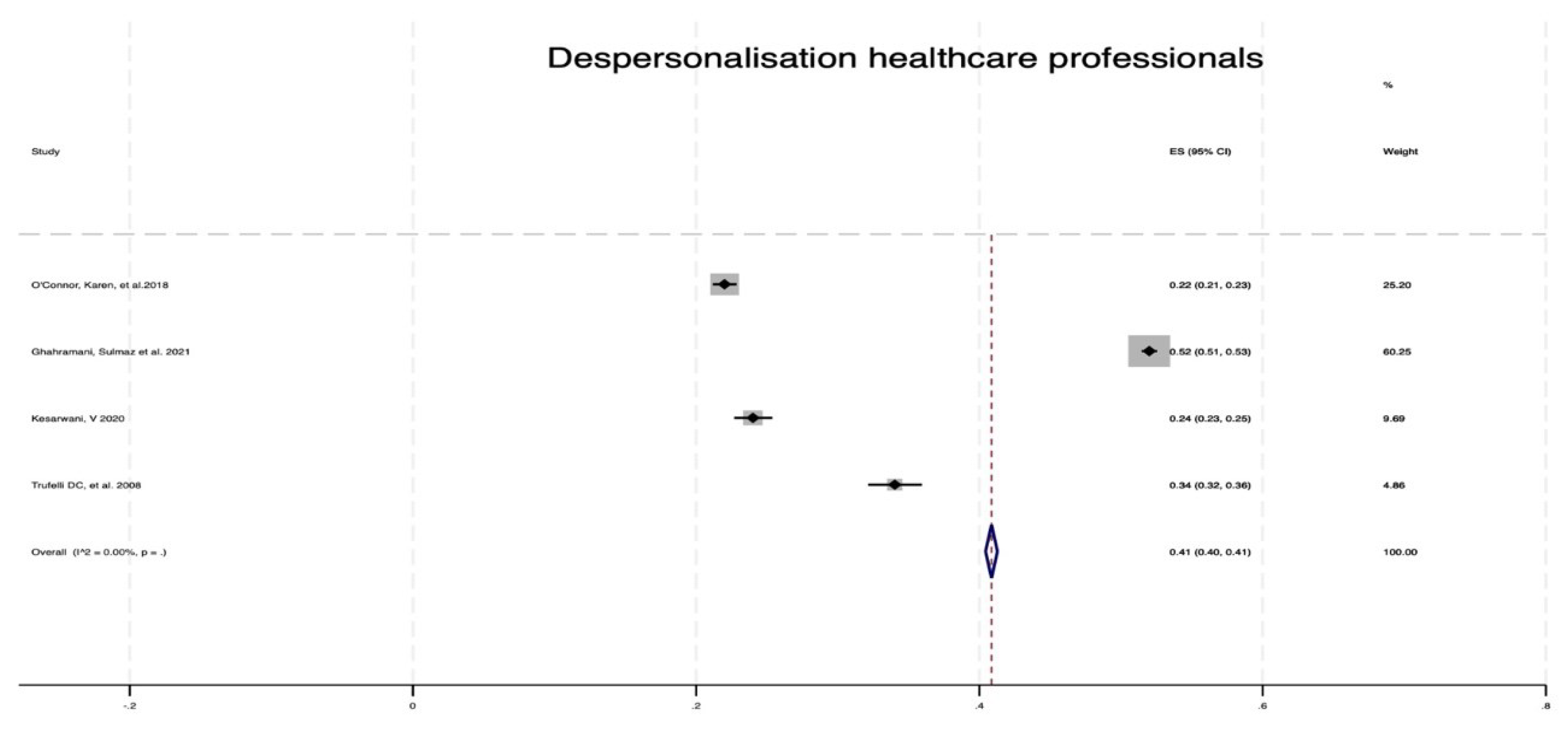

When the studies were compared on the Depersonalization Scale for Health Personnel, Doctors and Needs, 4 studies were included: one for health personnel, with a low I2 (0.00%) and a prevalence of 41% with a CI of 40; and one for 41% (

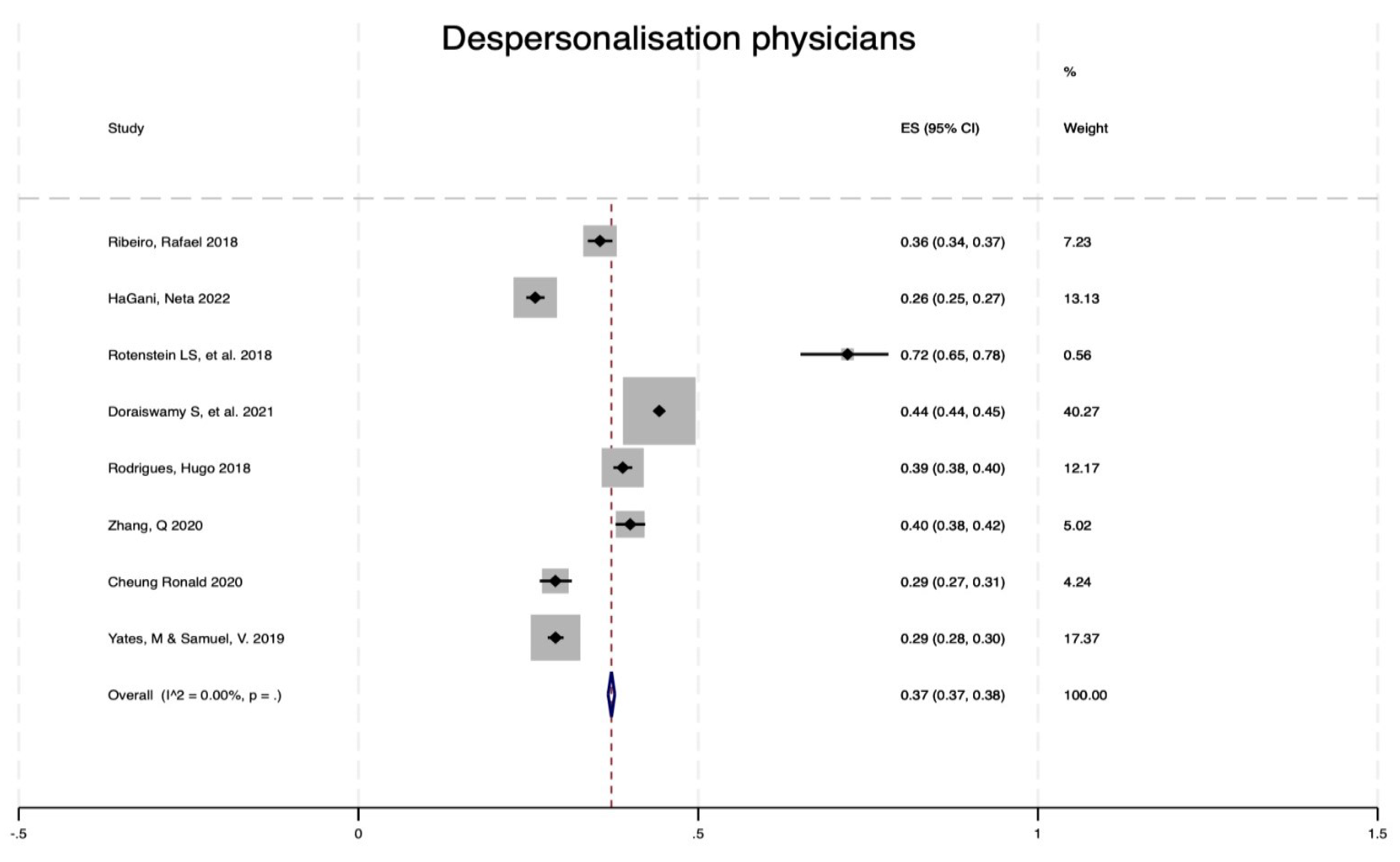

Figure 5). In contrast, for doctors, the depersonalization results included 8 studies, with a prevalence of 37%, a low I2 (0.00%) and a CI between 37% and 38% (

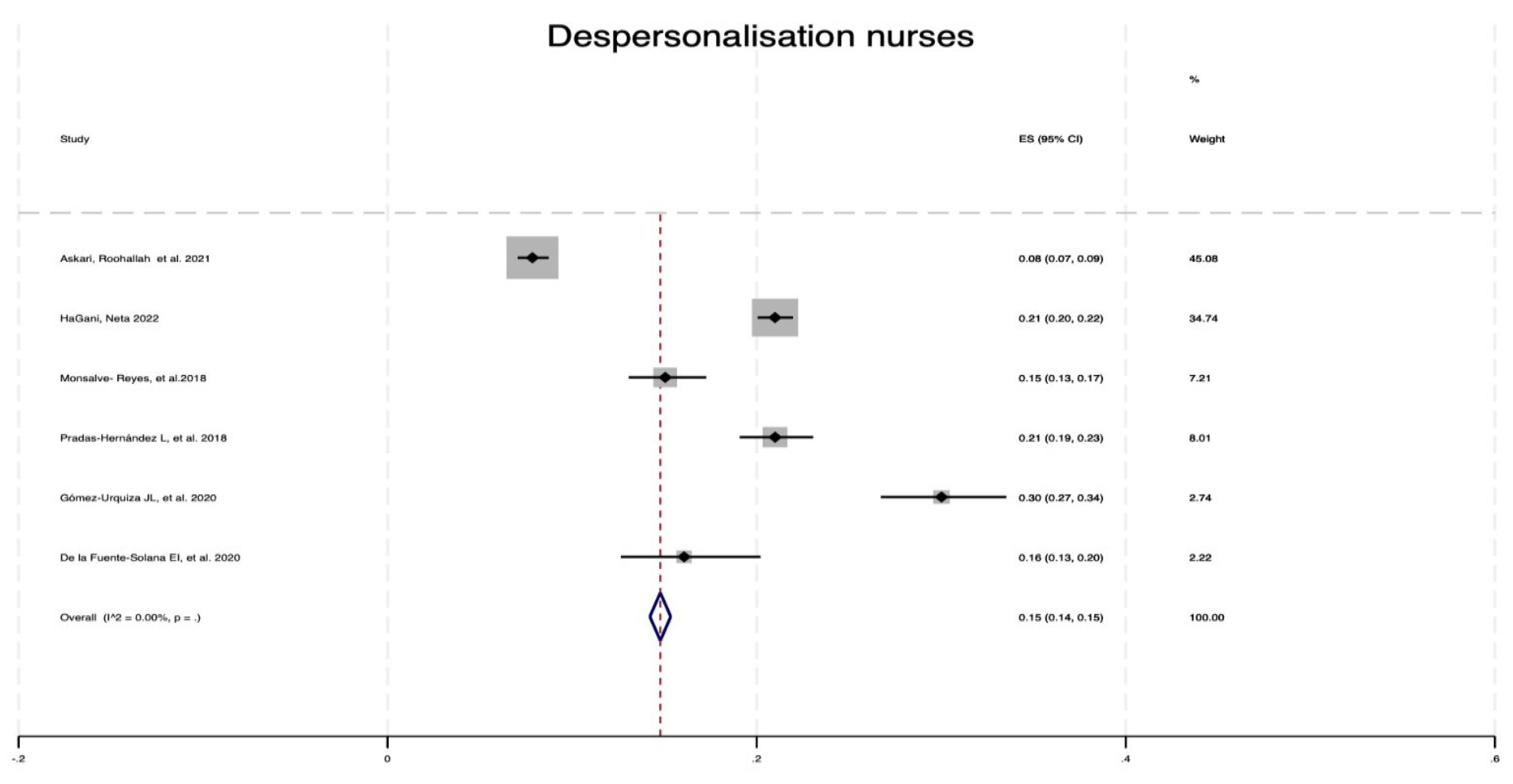

Figure 6), and one study for nurses, with a low I2 (0.00%) and a prevalence of 15%, with a CI of 14% to 15% (

Figure 7).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of depersonalization (MBI) among healthcare personnel from 2008 to 2018.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of depersonalization (MBI) among healthcare personnel from 2008 to 2018.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of depersonalization (MBI) among doctors from 2008 to 2022.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of depersonalization (MBI) among doctors from 2008 to 2022.

Figure 7.

Forest plot of depersonalization (MBI) among nurses from 2008 to 2022.

Figure 7.

Forest plot of depersonalization (MBI) among nurses from 2008 to 2022.

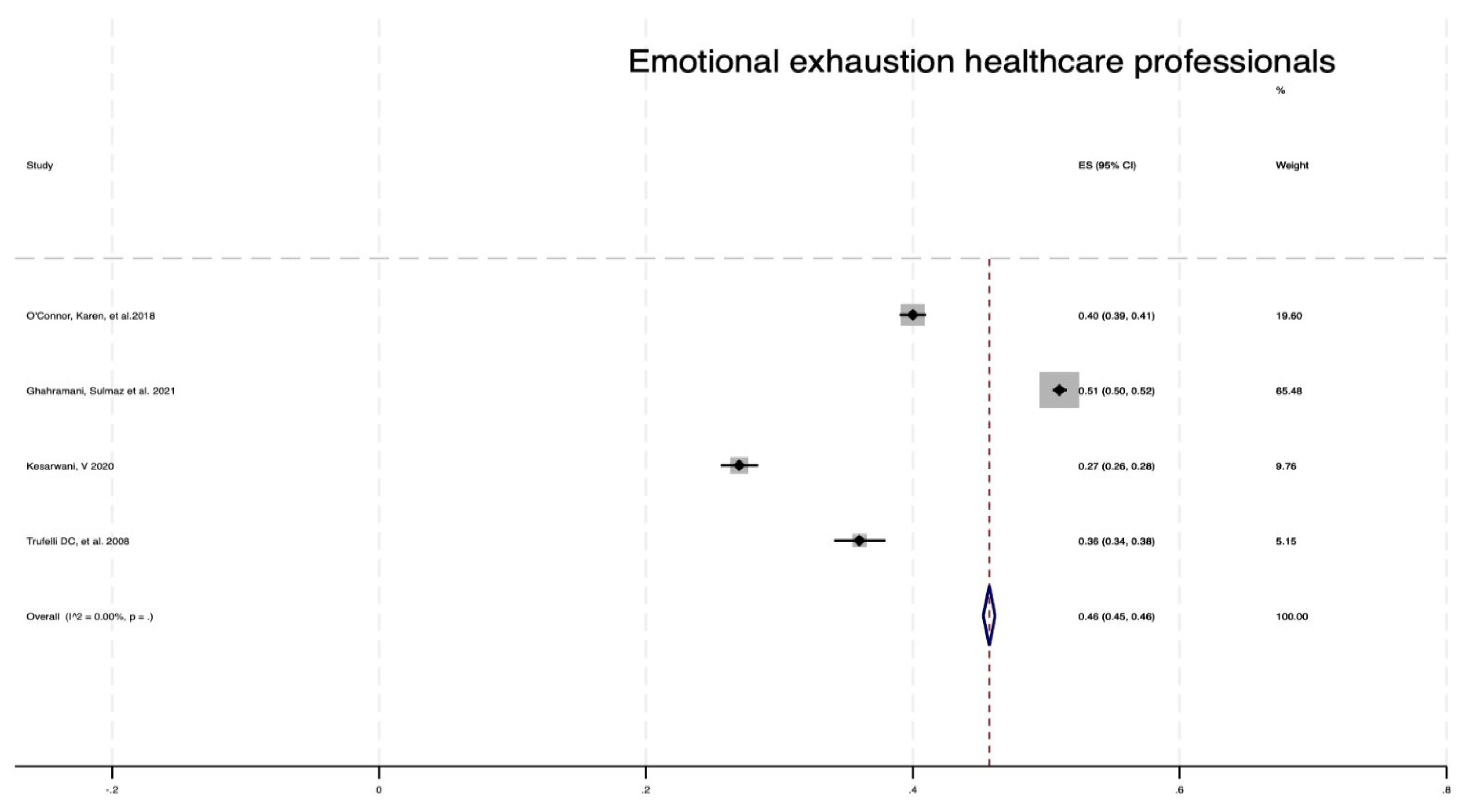

Figure 8.

Forest plot of emotional exhaustion (MBI) in healthcare personnel from 2008 to 2018.

Figure 8.

Forest plot of emotional exhaustion (MBI) in healthcare personnel from 2008 to 2018.

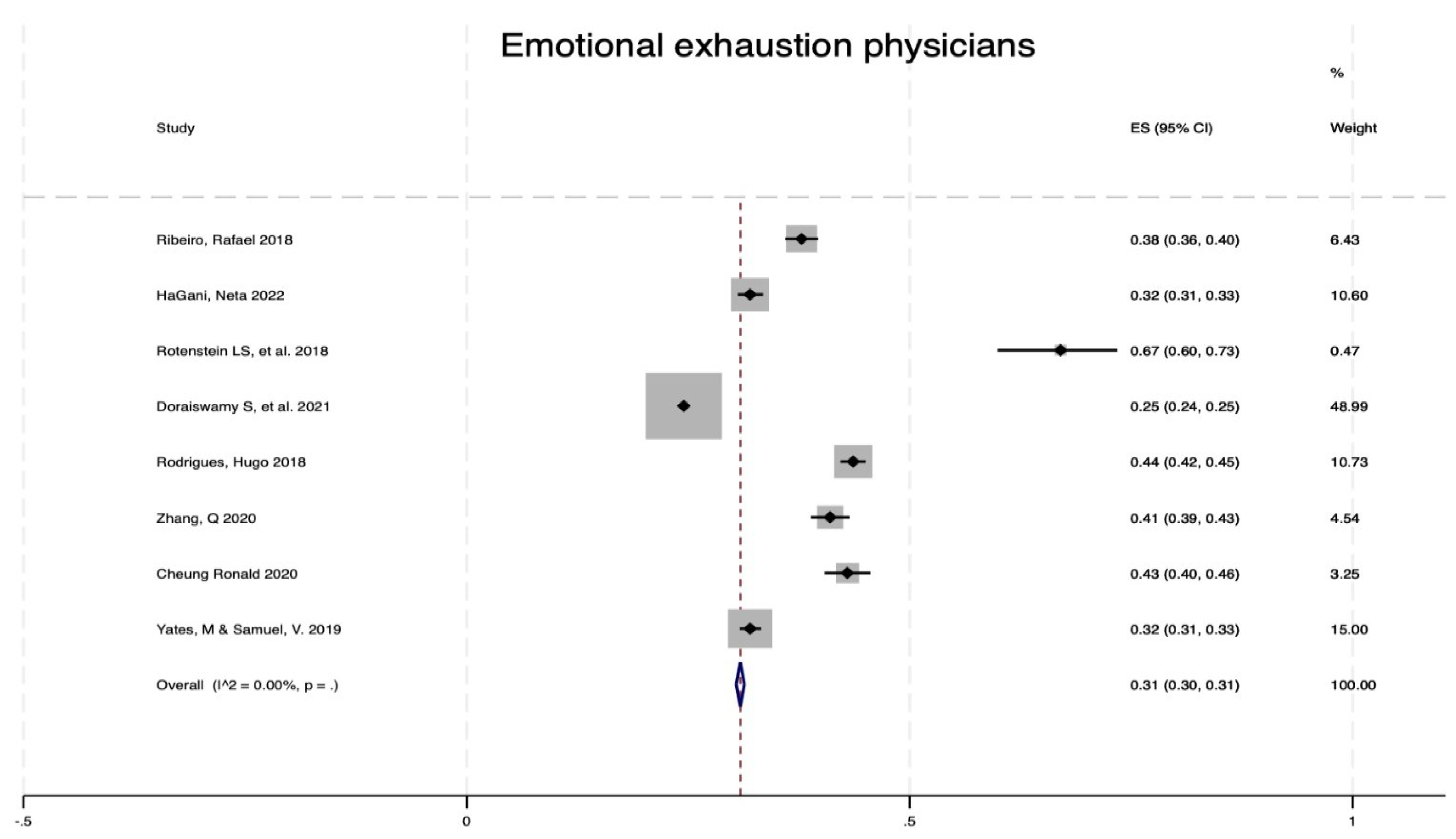

Figure 9.

Forest plot of emotional exhaustion (MBI) among doctors from 2008 to 2022.

Figure 9.

Forest plot of emotional exhaustion (MBI) among doctors from 2008 to 2022.

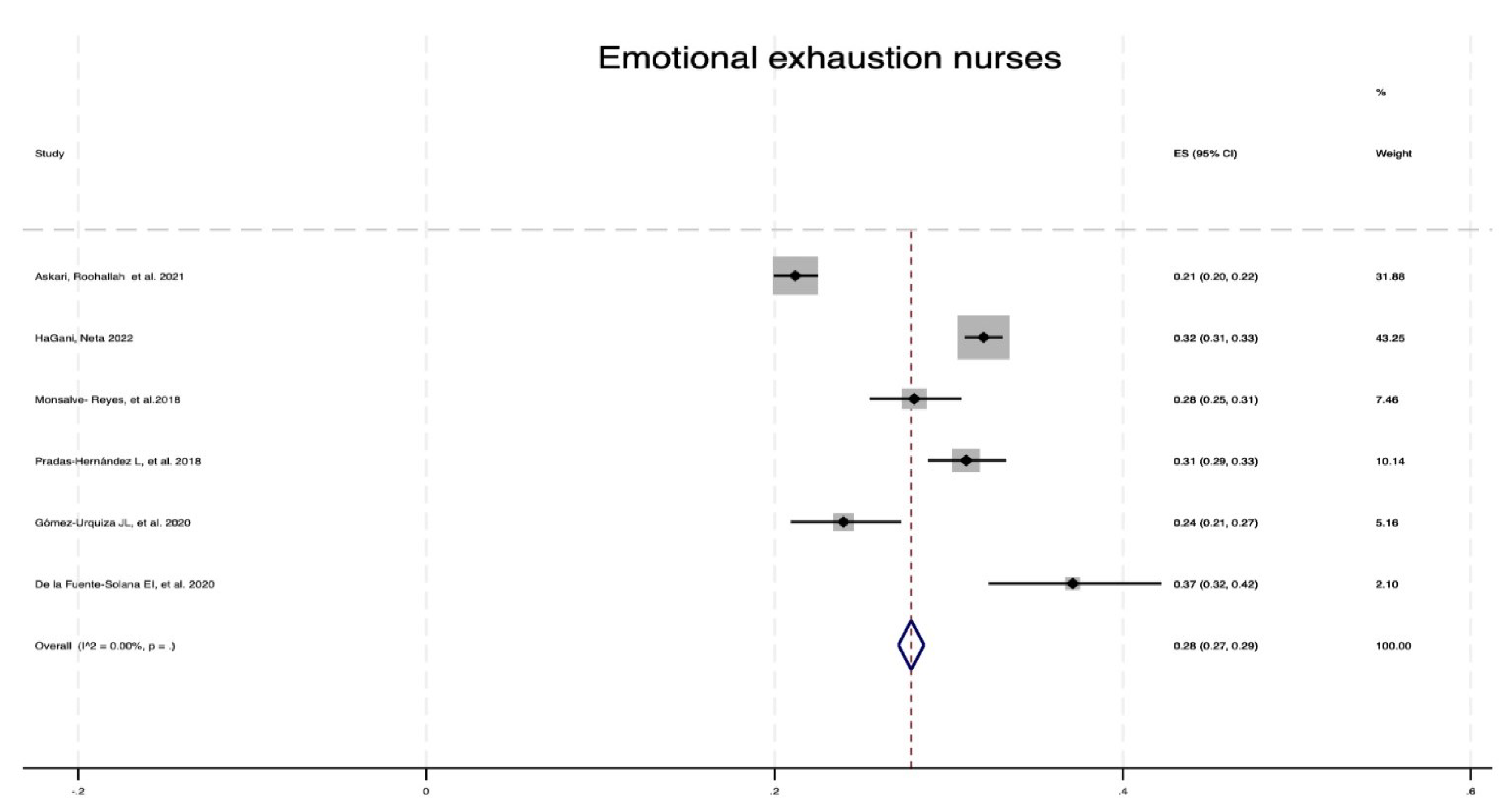

Figure 10.

Forest plot of emotional exhaustion (MBI) in nurses from 2008 to 2022.

Figure 10.

Forest plot of emotional exhaustion (MBI) in nurses from 2008 to 2022.

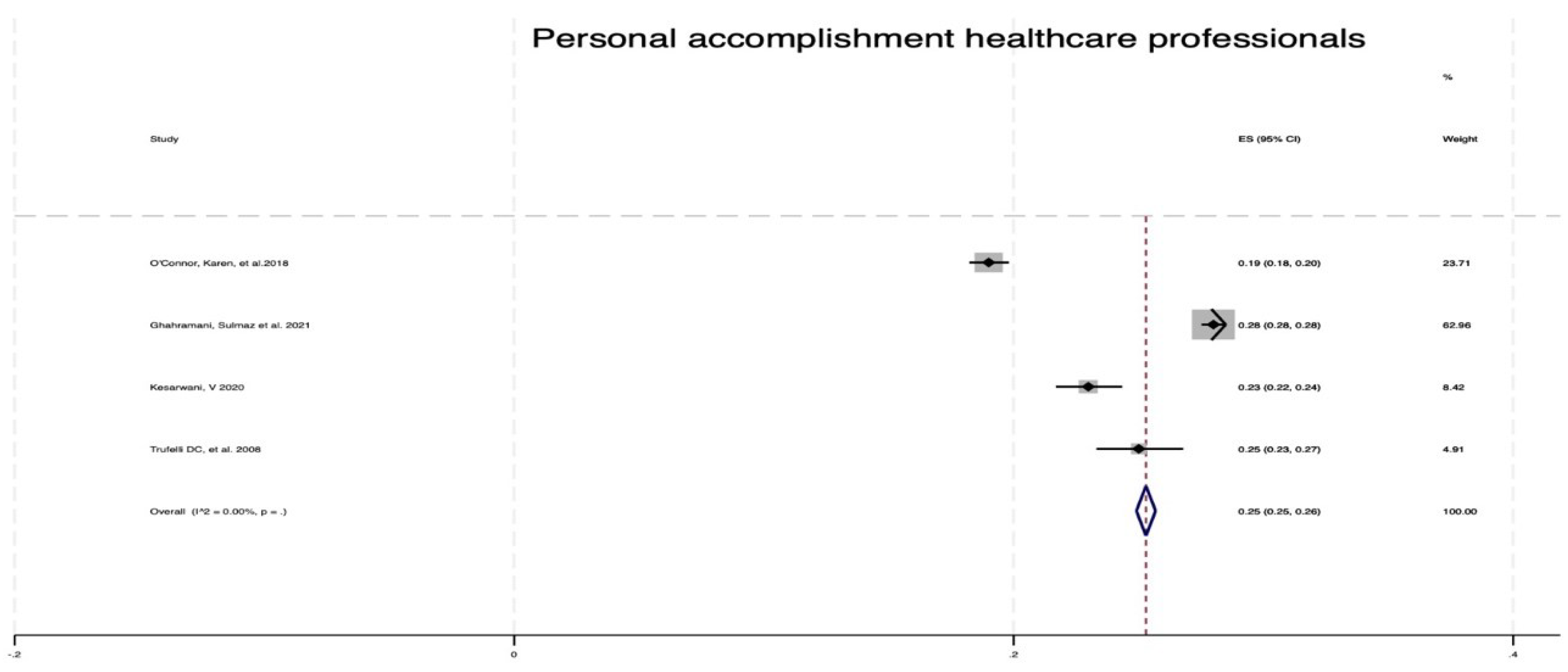

Figure 11.

Forest plot of personal fulfillment (MBI) for healthcare personnel from 2008 to 2018.

Figure 11.

Forest plot of personal fulfillment (MBI) for healthcare personnel from 2008 to 2018.

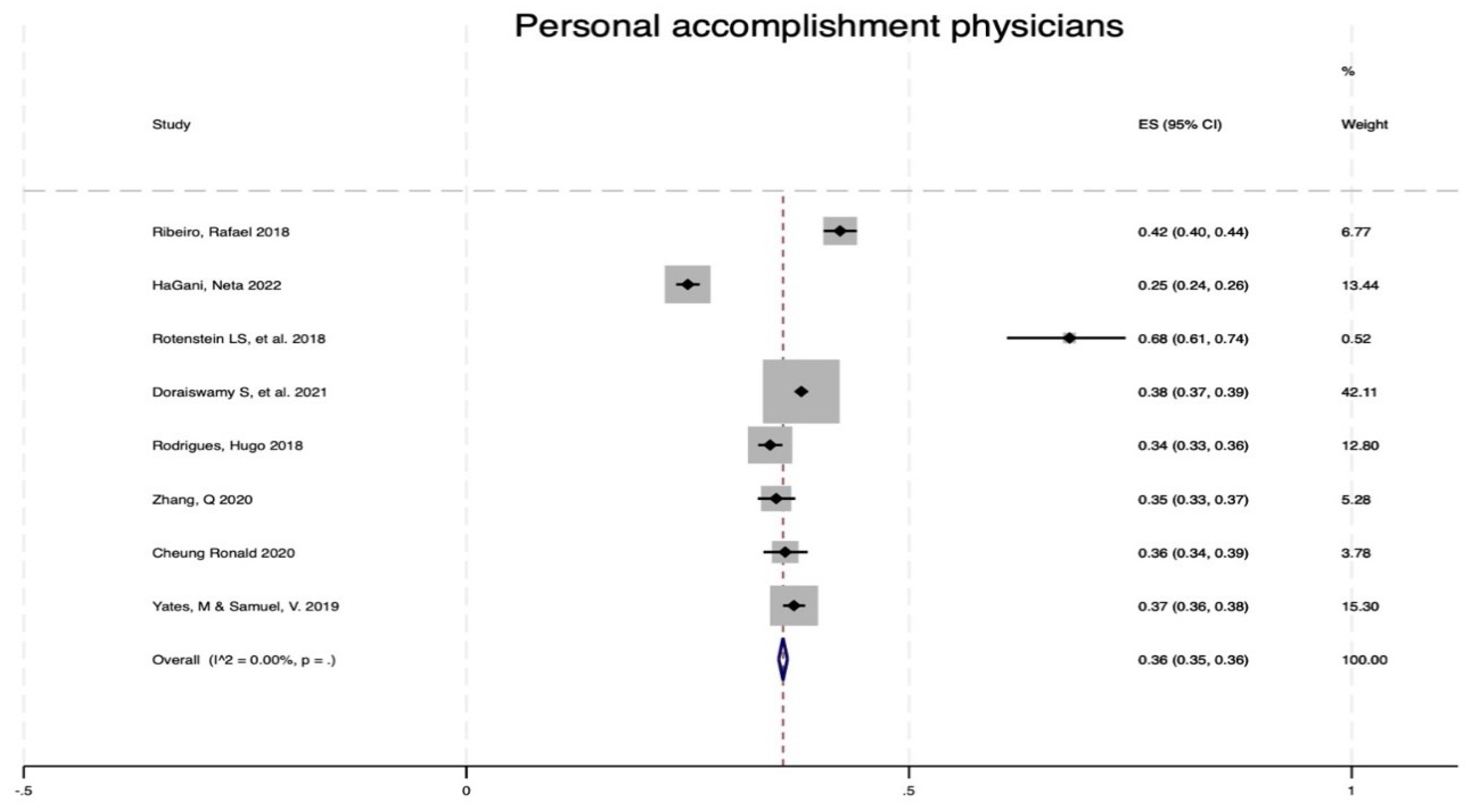

Figure 12.

Forest plot of personal fulfillment (MBI) for doctors from 2008 to 2022.

Figure 12.

Forest plot of personal fulfillment (MBI) for doctors from 2008 to 2022.

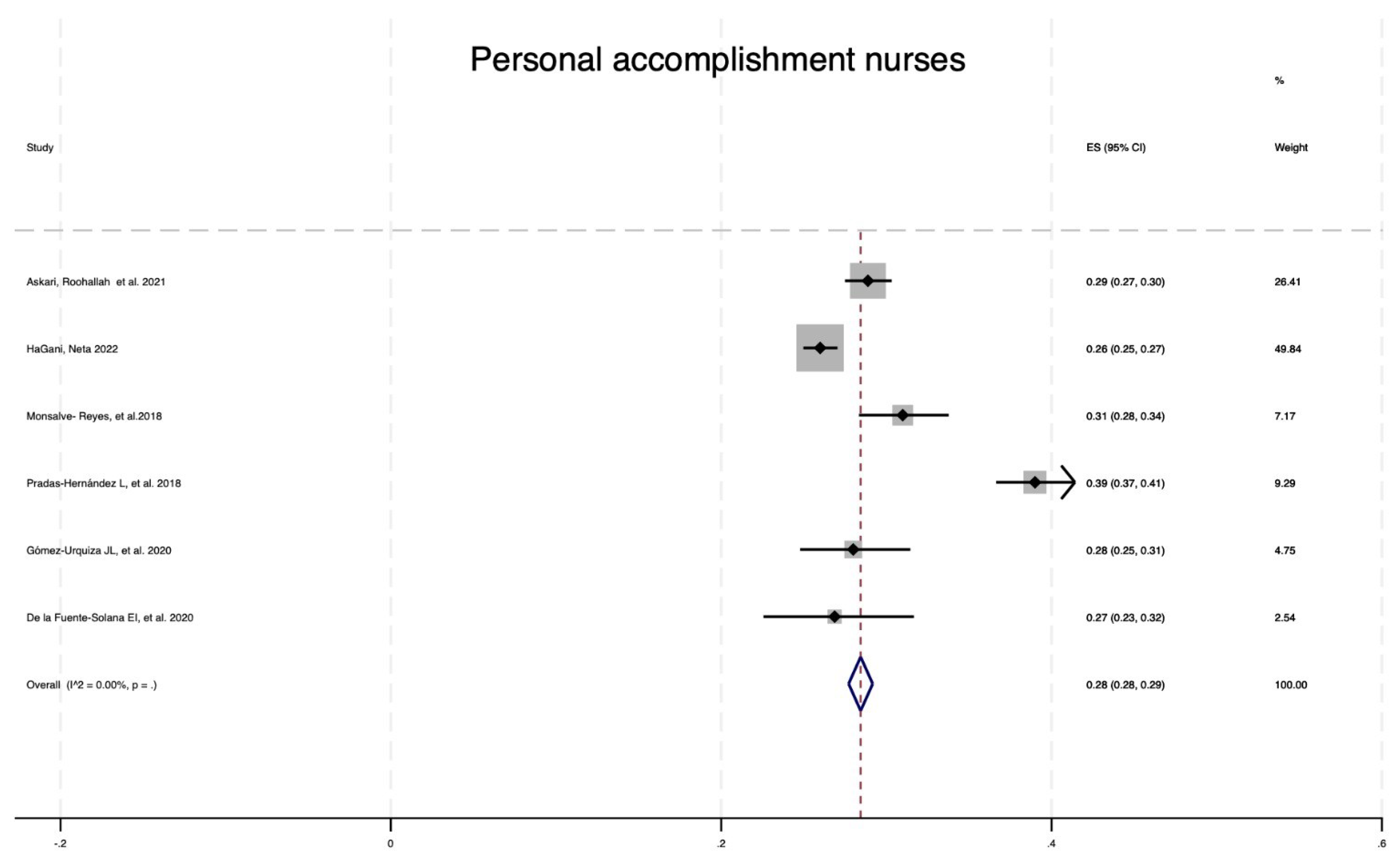

Figure 13.

Forest plot of personal fulfillment (MBI) among nurses from 2008 to 2022.

Figure 13.

Forest plot of personal fulfillment (MBI) among nurses from 2008 to 2022.

When contrasting the prevalence of emotional exhaustion for healthcare personnel, doctors and nurses, 4 studies were found to have a low I2 (0.00%), a prevalence of 46% and a CI of 45% to 46. For example, 8 studies were included, with a low I2 (0.00%), a prevalence of 31% and a CI between 30% and 31% (

Figure 9); for nurses, 6 studies had a prevalence of 28%, a low I2 (0.00%) and a CI between 27% and 29% (

Figure 10).

A comparison of the prevalence of personal fulfillment for healthcare personnel, doctors and nurses revealed that for healthcare personnel, 4 studies were included with a low I2 (0.00%), a prevalence of 25%, and a CI between 25% and 26. For doctors, 8 studies were included, for a prevalence of 36%, a low I2 (0.00%) and a CI of 35-36% were identified; for nurses, 6 studies were included, for a prevalence of 28%, a low I2 (0.00%) and a CI between 28% and 29% were included (

Figure 13).

When generally examining the prevalence of depression by subscale among health personnel, doctors and nurses, it was found that health personnel had the highest prevalence of depersonalization (41%) and emotional exhaustion (46%), while when reviewing only doctors and nurses, the first had a higher prevalence of DE (37%) vs 15% and of AE (36%) vs 28%.

Table 4.

AMSTAR II. Critical evaluation of systematic reviews of selected studies on the prevalence of burnout 2008-2022 in healthcare personnel, doctors and nurses.

Table 4.

AMSTAR II. Critical evaluation of systematic reviews of selected studies on the prevalence of burnout 2008-2022 in healthcare personnel, doctors and nurses.

| Evaluation Question |

Adriaenssens 2014 |

Askari Roohallac 2021 |

Cheung 2020 |

From the Solana Source 2019 |

Doraiswamy 2021 |

From the Solana Source 2020 |

Ghahramani 2021 |

Gomez Urquiza 2020 |

HaGani 2022 |

Kesarwani 2020 |

| 1. Do the research questions and inclusion criteria for the review include the PICO components? |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

| 2. Does the review report contain an explicit statement that the methods were established prior to its performance and are any significant deviations from the protocol justified? |

Yes partial |

Forks |

Yes partial |

Forks |

Partial |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

| 3. Did the authors of the review justify their decision on the study designs to include? |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

| 4. Did the review authors use a comprehensive literature search strategy? |

Yes partial |

Forks |

Yes partial |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

| 5. Did the review authors perform study selection in duplicate? |

Not specified |

Forks |

Not specified |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Not explicitly mentioned |

Forks |

Not explicitly mentioned |

Forks |

| 6. Did the review authors perform data extraction in duplicate? |

Not specified |

Forks |

Not specified |

Forks |

Forks |

Not explicitly stated |

Not explicitly mentioned |

Not explicitly mentioned |

Not explicitly mentioned |

Not explicitly mentioned |

| 7. Did the review authors provide a list of excluded studies and justify the exclusions? |

Yes partial |

Forks |

Yes partial |

Forks |

Partial |

Not explicitly stated |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Table 4.

AMSTAR II. Critical evaluation of systematic reviews of selected studies on the prevalence of burnout 2008-2022 in healthcare personnel, doctors and nurses.

Table 4.

AMSTAR II. Critical evaluation of systematic reviews of selected studies on the prevalence of burnout 2008-2022 in healthcare personnel, doctors and nurses.

| Evaluation Question |

Karuna 2022 |

Monsalve-reyes2018 |

O’Connor 2018 |

Pradas 2018 |

Ribeiro 2018 |

Rodrigues 2018 |

Rothenstein 2018 |

Trufelli 2008 |

Yachts 2018 |

Zhang 2020 |

| 1. Do the research questions and inclusion criteria for the review include the PICO components? |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

| 2. Does the review report contain an explicit statement that the methods were established prior to its performance and are any significant deviations from the protocol justified? |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

| 3. Did the authors of the review justify their decision on the study designs to include? |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

| 4. Did the review authors use a comprehensive literature search strategy? |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

Forks |

| 5. Did the review authors perform study selection in duplicate? |

Not explicitly mentioned |

Not explicitly mentioned |

Forks |

Not explicitly mentioned |

Not explicitly mentioned |

Not explicitly mentioned |

Not explicitly mentioned |

Forks |

Not explicitly mentioned |

No |

| 6. Did the review authors perform data extraction in duplicate? |

Not explicitly mentioned |

Not explicitly mentioned |

Forks |

Not explicitly mentioned |

Not explicitly mentioned |

Not explicitly mentioned |

Forks |

Forks |

Not explicitly mentioned |

No |

| 7. Did the review authors provide a list of excluded studies and justify the exclusions? |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Forks |

4. Discussion

The prevalence of burnout according to the MBI subscales was as follows: high DP (33%), high AE (37%) and low RP (29%). The latter was interpreted in reverse; that is, the lower the achievement or personal achievement score was, the more affected the subject was. For each of the subscales, the I2 was 0%, indicating that there were no discrepancies between the selected items. Similarly, these findings suggest that health professionals, doctors and nurses have a high level of affection in the three subscales, with the exception of doctors, for whom personal fulfillment is located in the intermediate range. Thus, following the literature and in accordance with Ghahramani [

6] 2021, having high scores in the AE and DP indicates the presence of burnout.

In our study, it is evident that the prevalence of burnout according to the MBI subscale is high for depersonalization and emotional exhaustion, as well as low for personal fulfillment, although a comparison of the prevalence according to subscale and professional profile before and during the pandemic could not be made. The 20 articles selected for the review contained data collected only prior to the pandemic. However, when comparing the data from the literature before the pandemic and during the pandemic on the prevalence of burnout, there were no changes or differences in the prevalence of burnout among health personnel, doctors and nurses. These findings contrast with what was identified by Shen [

24], in which the frequency of burnout did not change during the pandemic (high AE 2019 = 53.2% vs high AE 2020 =53.3%; high DP 2019 = 46.8% vs high DP 2020 = 42.4%; and high PR 2019 = 30% vs high PR 2020 = 30.9%). Although there is important discussion about the cutoff point and interpretation of the results of the MBI subscales, in the case of Maslach, the indication is that the dimensions of AE and DP should score high and that of RP should be low in a three-dimensional relationship to determine the presence of burnout

2. There is no consensus regarding this because other authors state that, with only a high mastery, burnout is already considered to be present [

25]. According to other studies, the personal achievement score is considered less important for the presence of burnout; therefore, having high scores in AE and DP is considered to indicate the presence of burnout [

6].

Of the 18 articles included in the meta-analysis, 9 had a low level of confidence as a result of the AMSTAR 2 evaluation; this was also the case for critical questions 5, 6 and 7, which corresponded to the following: Did the review authors perform study selection in duplicate? Did the review authors perform data extraction in duplicate? Did the review authors provide a list of excluded studies and justify the exclusions? These articles are Cheung 2020, Ghahramani 2021, HaGani 2022, Karuna 2022, Monsalve-Reyes 2018, Pradas 2018, Ribeiro 2018, Rodríguez 2018 and Yates 2019.

Among the limitations of this study, the lack of studies with data collected during the pandemic that met the inclusion criteria is recognized, with the exception of Karuna23 et al. (2022), whose data met the criteria; these studies were excluded from the meta-analysis because they included average data. and not by subscale, leaving the study without the possibility of comparing the prevalence of burnout among health professionals before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, other aspects that could be considered when analyzing the prevalence results by subscale include the inclusion of articles from different countries without discriminating cultural practices, health systems, training of health professionals, working conditions, gender and age, factors that can generate important biases and that can modify the prevalence results. On the other hand, the prevalence of burnout by subscale may also vary according to the extent to which health professionals work in urban vs. rural health centers, primary care centers vs. specialized care, large or small hospitals, or economic income. The type of contract and work overload are aspects that influence the performance of the MBI, as are the different translations of the instrument and the multiple nosological concepts regarding burnout syndrome.

Similarly, within the strengths of this review of reviews, it can be highlighted that the studies showed low heterogeneity and discrepancies between articles, as a review of reviews with a fairly robust sample of 233,087 participants was performed. Likewise, the 20 articles included corresponded to systematic reviews that maintained similar inclusion criteria in terms of professional profile, use of the MBI and data collected (Table 4).

The results obtained are similar to those of other studies, demonstrating once again that health professionals, doctors and nurses have a high prevalence of burnout in at least one of the MBI domains (AE, DP or RP), which indicates a greater probability of making medical errors that affect work performance and generate a direct negative impact on the care and subsequent evolution of users of health services. Consequently, it is essential to understand the symptoms of burnout syndrome and detect this clinical condition early to intervene preventively, promote the mental well-being of health professionals and reduce the risk of further medical errors and other undesirable outcomes due to burnout. burnout.

At the public health level, it is essential to address this phenomenon because doctors and nurses are the professionals who deal with everyday health issues on the first line of response; therefore, the health systems and the health authority of each country must establish a roadmap for the early identification of this syndrome, as well as interventions with evidence at the individual and group level that can be developed in health institutions not only to address a large-scale event such as the COVID-19 pandemic but also for daily demands, which, as the results presented here show, is frequent in healthcare personnel due to the nature of clinical practice.

After the results of this study are known, meta-analyses of the prevalence of burnout according to the MBI subscale according to medical specialties (oncologists, anesthesiologists, emergency physicians, primary care physicians) and nursing specialties (pediatrics, oncology, palliative, emergencies) are needed to determine whether there is a difference in these subgroups and relevant information for the development of interventions for each subarea.

Moreover, in practice, attention must be given to warning signs of this syndrome (AE, DP and RP) at the individual and institutional levels because the burden of this disease must be known and understood so that it can be detected. and treat them in a timely manner, avoiding severe cases of burnout and reducing medical errors that impair the quality of health care or service. It is necessary to improve the health systems’ hiring and employment conditions for health workers, with the purpose of guaranteeing stability and well-paid payments in a way that favors the well-being and mental health of these workers.

5. Conclusions

Health professionals, doctors and nurses showed a high prevalence of depersonalization (33%) and emotional exhaustion (37%), as well as a low prevalence of personal fulfillment (29%), which represents a high prevalence of burnout.

Healthcare personnel as a whole had a greater prevalence of burnout than did doctors and nurses, which indicates that interventions should be generally directed at this group of professionals without leaving anyone behind.

The presence of burnout (high scores in AE – DP and low in RP) shows that burnout is a problem of great magnitude and, as such, must be addressed immediately at the individual and group levels by institutions and systems. of health.

There are no publications of systematic reviews during the pandemic that show prevalence data from the MBI subscale but only from the average score, which makes it difficult to perform a meta-analysis to compare prevalence before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is urgent to improve the early detection of burnout in health professionals to promote the mental and occupational well-being of workers and simultaneously avoid clinical errors as part of the undesirable results of burnout.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, ABC. and CB.; methodology, ABC.; software, all authors.; validation, VC., DM. and ES.; formal analysis, JA.; writing—original draft preparation, all authors. Writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, all authors; project administration, all authors; funding acquisition, ABC. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Dirección General de Investigaciones of Universidad Santiago de Cali, grant number 01-2024, and the APC was funded by Dirección General de Investigaciones of Universidad Santiago de Cali.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- WHO. (2022, 02). World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved from ICD-11 for mortality and morbidity statistics. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/lm/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/129180281.

- Maslach, C. Maslach Burnout Inventory. 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, B. AMSTAR-2: Critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews of health intervention studies. Evidence 2018, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor Karen, M.D. Burnout in mental health professionals: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and determinants. European Psychiatry 2018, 53, 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, R.; Martuscelli, O.; Vieira, A.; Vieira, C. Prevalence of Burnout among Plastic Surgeons and Residents in Plastic Surgery: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 2018, 6, e1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghahramani Z, K.B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of burnout among healthcare workers during COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 12, 758849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askary, R., Fllahzadeh, H., Heidarijamebozorgi, M., Keyvanlo, Z., & Kargar, M. Job burnout among nurses in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nursing and midwifery studies 2021. [CrossRef]

- HaGani, N., Yagil, D., & Cohen, M. (2022). Burnout among oncologists and oncology nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Psychological Association, 53-64. [CrossRef]

- Monsalve-Reyes, C., San Luis-Costas, C., Gómez-Urquiza, L., Albendín-Garcia, L., Aguayo, R., & Cañadas-De la Fuente, G. (2018). Burnout syndrome and its prevalence in primary care nursing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC family practice. [CrossRef]

- Pradas-Hernández, L., Ariza, T., Gómez-Urquiza, J., Albendin-García, L., De la Fuente, E., & Cañadas-De la Fuente, G. (2018). Prevalence of burnout in pediatric nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. [CrossRef]

- Gómez, L. Gómez, L., Albendin, L., A, V., Ortega, E., Ramírez, L., Membrive, M., & Suleima, N. (2020). Burnout in palliative care nurses, prevalence and risk factors: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Environmental Research and Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Adriaenssens, J., De Gucht, V., & Maes, S. (2014). Determinants and prevalence of burnout in emergency nurses: a systematic review of 25 years of research. International Journal of Nursing Studies. [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente-Solana, E., Pradas, L., Salmerón, A., Suleima, N., Gómez, J., & Albendin-Garcia and Cañadas-De la Fuente, G. (2020). Burnout syndrome in pediatric oncology nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare. [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L., Torre, M., Ramos, M., Rosales, R., Guille, C., Sen, S., & Mata, D. (2018). Prevalence of burnout among physicians a systematic review. JAMA. [CrossRef]

- Doraiswamy, S., Chaabna, K., Jithesh, A., & Mamtani, R. &. (2021). Physician burnout in the Eastern Mediterranean region: influence of gender and related factors-Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of global health. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, H., Cobucci, R., Oliveira, A., Cabral, J., Medeiros, L., Gurgel, K., . . . Gonçalves, A. (2018). Burnout syndrome among medical residents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Mu, M., He, Y., & Cai, Z. &. (2020). Burnout in emergency medicine physicians: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Kesarwani, V., Hussain, Z., & George, J. (2020). Prevalence and factors associated with burnout among healthcare professionals in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, R., Yu, B., Lordanous, Y., & Malvankar, M. (2020). The prevalence of occupational burnout among ophthalmologists: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Reports. [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente-Solana, E., Suleima-Martos, N., Pradas-Hernández, L., Gomez-Urquiza, J., Cañadas-De la Fuente, G., & Albendin-García, L. (2019). Prevalence, related factors, and levels of burnout syndrome among nurses working in gynecology and obstetrics services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environmental Research and Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Yates, M. &. (2019). Burnout in oncologists and associated factors: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Feature and review paper. [CrossRef]

- Tufelli, D., Bensi, C., Garcia, J., Narahara, J., Abrao, M., Diniz, R., . . . Soares, H. &. (2008). Burnout in cancer professionals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of cancer care. [CrossRef]

- Karuna, C., Palmer, V., Scott, A., & Gunn, J. (2022). Prevalence of burnout among GPs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of General Practice, Online First 2022 , 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Shen, X., Xu, H., Feng, J., Ye, j., Lu, Z., & Gan, Y. (2022). The global prevalence of burnout among general practitioners: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Family practice, 39 , 943-950. [CrossRef]

- Wisetborisut, A. Cancer care workers in Ontario: prevalence of burnout, job stress and job satisfaction. Occupational Medicine 2014, 64, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).