1. Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a multifactorial disease often associated with other comorbidities. PE ranks as the third most common cardiovascular disease following acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and stroke [

1]. The annual incidence rate of VTE is 1-2 cases per 1000 individuals in the general population and exponentially increases with age, reaching 1 case per 100 individuals over the age of 80 years [

1,

2]. In recent years, there appears to be a growing trend in incidence [

3], likely due to the aging population and a higher prevalence of comorbidities associated with VTE itself, such as obesity, heart failure (HF), and cancer, as well as immobility associated with surgery or hospitalization for medical illness [

4].

Previous studies have described that HF is an independent risk factor for the development of VTE [

5,

6], largely due to the prothrombotic state observed in these patients [

7,

8]. It is estimated that chronic HF may be present in the medical history of patients who develop a thrombotic event in up to 10-20% of cases [

9]. Furthermore, various studies demonstrate that a thrombotic event within a hospitalization for acute HF is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and readmissions [

10,

11,

12].

However, there are few studies that analyze the implications of a history of HF in patients with acute PE, both in its presentation and in its short- and long-term outcomes. Various prognostic tools have been developed to analyze the risk of recurrence, mortality, and bleeding in patients who develop a thrombotic event, and few include HF among their parameters [

13,

14,

15]. The Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (PESI) [

15] and its simplified version (PESIs) [

16] do include HF as a risk factor for early mortality in patients with PE. However, other studies have been unable to establish HF as an independent prognostic factor in patients with PE [

17]. Regarding the bleeding risk, there is no clear consensus on the impact that a history of HF may have on patients with acute PE. While some authors argue that HF increases the risk of major bleeding in these patients [

18,

19], others do not find a clear association [

20].

There is a growing recognition of prognostic differences among patients with HF based on the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), suggesting that patients with HF and reduced LVEF should be considered as a subgroup with a poorer prognosis [

21]. However, to date, none of the scores used in VTE reflect the prognostic difference between HF patients based on whether they have reduced or preserved LVEF, a consideration that is assessed in other cardiovascular diseases with high prevalence and morbidity-mortality [

22].

The objective of this study is to assess the risk of developing early complications (within the first 30 days) in patients with a history of HF who develop acute PE. The secondary objective is to evaluate the role of LVEF in the early prognosis of patients with HF who develop acute PE.

2. Method

2.1. Study design

An observational and prospective study was conducted at two tertiary hospitals in the same region to assess differences among patients diagnosed with symptomatic acute PE based on the presence or absence of a history of HF. Baseline characteristics, presentation patterns, and outcomes (mortality, major bleeding, recurrence) were compared between both groups. The study included a sub-analysis that evaluated differences among patients based on the presence of HF with reduced LVEF.

2.2. Study population

Consecutive patients aged 18 or older diagnosed with symptomatic acute PE between January 2012 and December 2022 were included, with a follow-up of at least 30 days. Patients with an incidental PE diagnosis or those with a follow-up of less than 30 days were excluded. The diagnosis of PE was confirmed through CT pulmonary angiography or lung scintigraphy. Patients were classified as having HF if they had a documented diagnosis of HF prior to the episode of PE. HF patients were further subclassified based on LVEF into those with preserved LVEF (LVEF ≥50%) and those with reduced LVEF (LVEF <49%).

2.3. Outcomes

The primary objective of the study was the development of a composite event that includes all-cause mortality, major bleeding, and recurrence during the first 30 days following the diagnosis of PE in patients with a history of HF. The secondary objective was the development of the composite event in the subgroup of patients with HF and reduced LVEF. Major bleeding was defined according to ISTH guidelines as fatal bleeding and/or symptomatic bleeding in a critical area or organ, such as intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular, retroperitoneal, intra-articular, or pericardial, or intramuscular with compartment syndrome, and/or bleeding causing a fall in hemoglobin levels of 1.24 mmol/L (20 g/L or greater) or more, or leading to a transfusion of 2 U or more of whole blood or red cells [

23]. PE recurrence was defined as a new intraluminal filling defect on chest CT or a new ventilation–perfusion mismatch on lung scan.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were presented as frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR), depending on the normality and homogeneity of the sample, assessed using the Shapiro-Francia test and Levene’s test for variance homogeneity, respectively. The association between qualitative variables was evaluated using the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test. For numerical variables, the t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was used, depending on the normality of the variable.

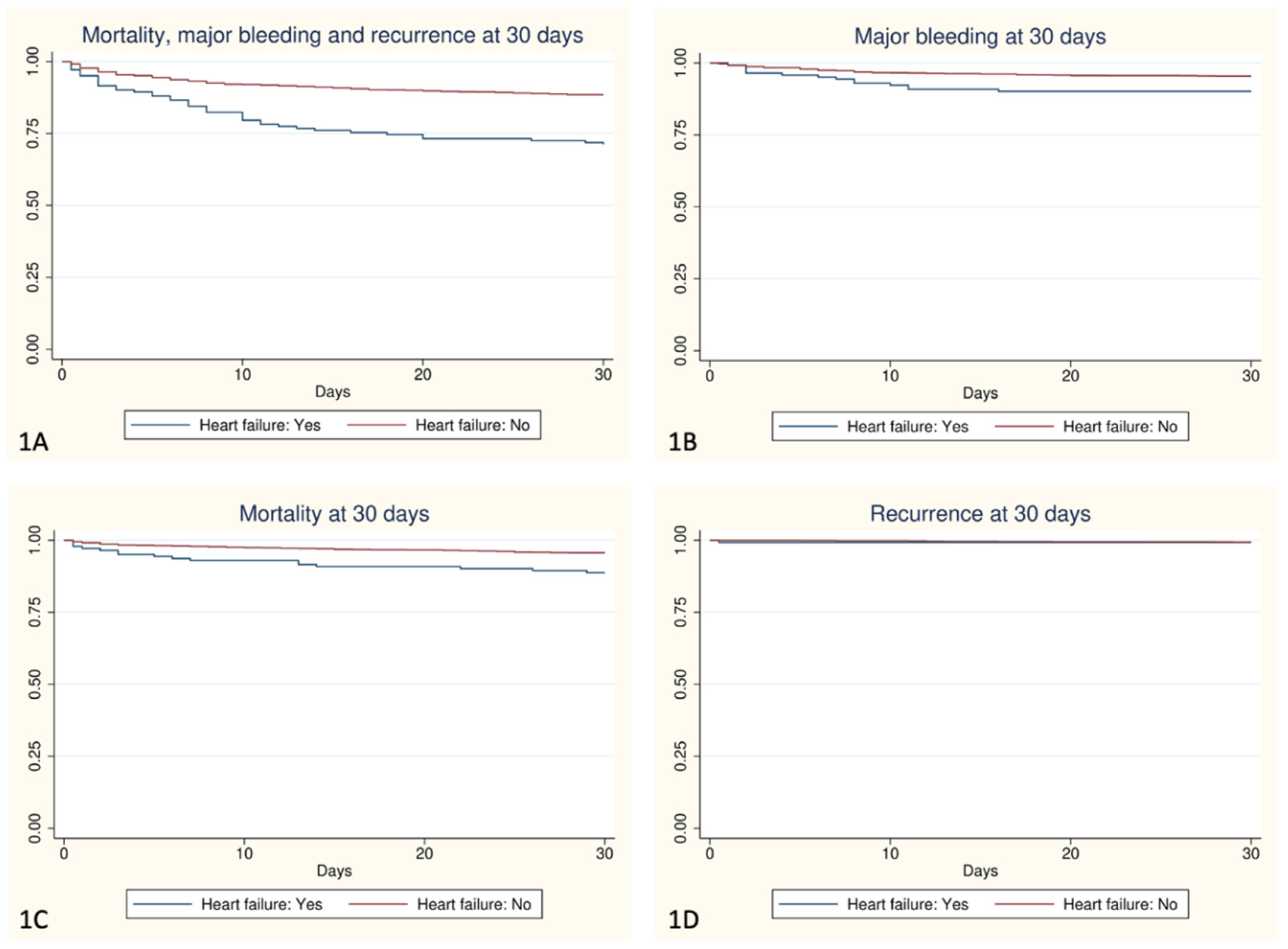

Unadjusted and adjusted Cox regression models were used, adjusting for age, sex, chronic kidney disease (CKD), cancer, thrombocytopenia (platelets <50,000), recent bleeding (in the last month), and anemia (hemoglobin <13g/dL in males and <12g/dL in females), considered as the most important confounders. These models were employed to predict the power of both overall HF and HF with reduced LVEF in relation to the composite event at 30 days (mortality, major bleeding, and recurrence), as well as mortality, major bleeding, and recurrence at 30 days separately. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for graphical representation. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant for all statistical tests. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY), was used for all calculations.

2.5. Ethical considerations

This study was conducted following international ethical recommendations for research involving human subjects, in accordance with the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki, as well as the guidelines established in Good Clinical Practice and current legislation. The study received approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee. All patients provided informed consent to participate in the study.

3. Results

Baseline characteristics and presentation of PE event

A total of 1991 patients with a diagnosis of symptomatic acute PE were included, of whom 142 (7.13%) had a history of HF. Baseline characteristics and provoking factors for VTE are summarized in

Table 1. Patients with HF were significantly older (82.5 vs. 68 years) and had a higher prevalence of ischemic heart disease (20.42% vs. 4.67%), cerebrovascular disease (19.72% vs. 5.21%), peripheral artery disease (9.86% vs. 2.39%), diabetes (28.87% vs. 14.75%), hypertension (88.02% vs. 47.24%), and atrial fibrillation (18.28% vs. 2.02%). Regarding provoking factors for VTE, patients with HF more frequently had prior immobilization before the event (39.44% vs. 28.18%), with no differences in the other factors.

Patients without a history of HF presented at the time of the event with a higher frequency of chest pain (39.97% vs. 26.76%), tachycardia (32.02% vs. 23.94%), and a higher thrombotic burden defined by a higher frequency of PE in main arteries (35.05% vs. 23.94%) and concomitant DVT (26.66% vs. 18.31%). Patients in the HF group had more renal insufficiency (50.70% vs. 21.25%), elevated troponin levels (60.55% vs. 40.78%), and elevated natriuretic peptide levels (77.48% vs. 44.63%). Information regarding the presentation and treatment received is available in

Table 2.

4. Outcomes and follow-up

Clinical outcomes at 30 days are summarized in

Table 3. A total of 96 patients died during the 30-day follow-up, with higher mortality in the HF group (11.27% vs. 4.33%, p <0.001). Both total bleeding and major bleeding were more frequent in the HF group (19.01% vs. 8.06%, p <0.001; and 9.86% vs. 4.54%, p=0.005, respectively). No significant differences were observed in VTE recurrence between both groups (

Figure 1).

In the multivariate analysis adjusted for age, sex, chronic kidney disease, cancer, thrombocytopenia, recent bleeding, and anemia, a higher frequency of the composite event was observed in the HF group (HR 1.93; 95% CI 1.35-2.76). In the bivariate analysis, the HF group showed higher mortality (HR 2.70; 95% CI 1.58-4.63) and major bleeding (HR 2.22; 95% CI 1.26-3.92), but these differences were not present in the multivariate analysis. In the sub-analysis of patients with reduced LVEF (n=24, 20.87% of HF patients), they presented a higher risk of major bleeding in the multivariate analysis (HR 3.44; 95% CI 1.34-8.81), but no differences were found in mortality or recurrence in patients with HF and reduced LVEF (

Table 4).

5. Discussion

In the present study, patients with HF who developed symptomatic acute pulmonary embolism had almost twice the risk of early complications in the first 30 days. This risk was independent of age, sex, or the presence of comorbidities such as renal disease, cancer, thrombocytopenia, recent bleeding, or anemia. Additionally, reduced LVEF was found to be an independent risk factor for the development of bleeding events in the first 30 days after acute pulmonary embolism.

Previous studies have indicated that a history of HF is a risk factor for developing both in-hospital and long-term complications among patients with PE. Death is one of the most frequently described complications; however, the literature is not unanimous in considering heart failure as an independent risk factor [

17,

24]. In our study, we observed in the bivariate analysis a higher mortality in the HF group (HR 2.70; 95% CI 1.58-4.63), but these differences were not present in the multivariate analysis. It is described in the literature [

9,

18,

19,

24,

25,

26] that patients with chronic heart failure who present with acute PE are often older and more frequently have other comorbidities such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), anemia, or ischemic heart disease, which we also observed in our study. This higher observed mortality rate is likely explained by the presence of these comorbidities. However, patients with HF have poorer pulmonary and cardiac reserve, resulting in lower tolerance to the acute PE episode and an inability to cope with its hemodynamic and ventilatory demands [

18,

19,

24,

26]. Additionally, in our study, we observed that patients with HF had a higher frequency of hypoxemia at the time of acute PE, a finding also described in the literature [

18]. In an analysis of clinical predictors of fatal pulmonary embolism, Laporte et al. [

17] observed a 2 to 3 times higher risk in patients with heart disease – including HF – although they could not confirm HF as an independent risk factor in their validation model. Another comparative study of patients with acute PE, conducted by Monreal et al. [

24], found higher crude mortality in patients with COPD (12%) and HF (17%), although they did not perform a multivariate analysis. In contrast, Piazza et al. [

19] did observe that HF was independently associated with higher mortality, both during hospitalization (OR 2.04; 95% CI, 1.15-3.62) and at 30 days of follow-up (OR 1.57; 95% CI, 1.01-2.43).

Regarding the risk of bleeding, there is no consensus on the role that HF might play in patients presenting with acute PE. While some studies describe a history of HF as a risk factor for major bleeding [

18,

19], others do not find such an association [

20]. Additionally, several prediction models have been developed to assess the individual risk of major bleeding during the first three months of anticoagulant therapy initiation in patients with VTE [

13,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]; in these models, chronic HF was assessed as a bleeding risk factor, but none of the studies described heart failure as an independent risk factor. Ducrocq et al. [

34] demonstrated that beyond associated comorbidities, HF itself is a risk factor for major bleeding. In previous research, a history of HF has been identified as a bleeding risk factor in patients presenting with a myocardial infarction [

35,

36], and acute HF is a component of the CRUSADE score to predict bleeding in these patients [

37]. In the bivariate analysis of our study, we observed an association between heart failure and a higher risk of major bleeding (HR 2.22; 95% CI 1.26-3.92), an observation that did not persist in the multivariate analysis. However, we found that LVEF was an independent risk factor for major bleeding (HR 3.44; 95% CI: 1.34-8.81). In this regard, the increased cardiac stress and frailty described in patients with reduced LVEF could contribute to the observed increased bleeding risk [

38].

In exploring prognostic differences in patients with HF, increasing attention has been given to LVEF as a distinguishing factor, and several studies suggest considering patients with reduced LVEF as a subgroup with a worse prognosis [

21,

39]. In the context of PE, some authors claim that the presence of reduced LVEF has independent predictive value for in-hospital mortality, which is not the case for patients with preserved LVEF [

9,

25,

40]. Additionally, the reduction in myocardial contractility and the use of beta-blockers in patients with reduced LVEF can worsen their inotropic and chronotropic response to PE. There is also a significantly reduced capacity to compensate for hypoxemia during PE, which may have an even more detrimental effect on patients with reduced LVEF, causing myocardial ischemia. However, Ovradovic et al. [

9] did not observe a significant association of any heart failure phenotype with 30-day mortality. In our study, we also did not observe differences in mortality based on the presented LVEF. Regarding bleeding risk in patients with acute PE and reduced LVEF, we are not aware of any studies in the literature that analyze this association. The results of our research support the importance of differentiating between patients with a history of heart failure with reduced or preserved LVEF, as bleeding risk at 30 days is higher in the former case.

Among the limitations of the study, the observational design implies that treatment decisions were made by physicians in each case. Additionally, the limited number of patients in the subgroup with reduced LVEF could affect the ability to obtain significant differences in some of the events. Among the strengths, this is the first study that provides a comprehensive assessment of the risk of early complications in patients with a history of HF following symptomatic acute PE. The combined perspective of these risks provides a more complete understanding of the clinical implications in this specific population. The results significantly reinforce the prognostic importance of HF in relation to early complications after symptomatic acute PE and contribute to the clinical understanding of the evolution of patients with this combination of medical conditions. Furthermore, this study reveals that reduced LVEF emerges as an independent risk factor for bleeding events in this context. This discovery provides a new perspective on the relationship between cardiac function and bleeding events, filling a gap in the existing literature.

6. Conclusions

In patients with symptomatic acute pulmonary embolism, heart failure is independently associated with a higher risk of developing early complications. Furthermore, heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction is an independent risk factor for major bleeding.

Author’s Contribution: Conceptualization, Mariam Farid-Zahran Osuna, Manuel Méndez-Bailón, Francisco Galeano-Valle, Javier Marco-Martínez and Pablo Demelo-Rodríguez; Data curation, Mariam Farid-Zahran Osuna, Vanesa Sendín Martín and Pablo Demelo-Rodríguez; Formal analysis, Mariam Farid-Zahran Osuna and Rubén Alonso-Beato; Investigation, Mariam Farid-Zahran Osuna, Manuel Méndez-Bailón, José Pedrajas, Francisco Galeano-Valle and Pablo Demelo-Rodríguez; Methodology, Mariam Farid-Zahran Osuna, Manuel Méndez-Bailón, Francisco Galeano-Valle and Pablo Demelo-Rodríguez; Supervision, Manuel Méndez-Bailón and Pablo Demelo-Rodríguez; Validation, Mariam Farid-Zahran Osuna; Visualization, Mariam Farid-Zahran Osuna and Pablo Demelo-Rodríguez; Writing – original draft, Mariam Farid-Zahran Osuna and Pablo Demelo-Rodríguez; Writing – review & editing, Mariam Farid-Zahran Osuna, Manuel Méndez-Bailón, José Pedrajas, Rubén Alonso-Beato, Francisco Galeano-Valle, Vanesa Sendín Martín, Javier Marco-Martínez and Pablo Demelo-Rodríguez.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Pedrajas has received speaker’s honoraria from the following pharmaceutical companies: Leo Pharma, ROVI and Bayer. Dr. Galeano-Valle has received speaker’s honoraria from the following pharmaceutical companies: ROVI, Techdow, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers, and Daichii-Sankyo. Dr. Sendín Martín has received speaker’s honoraria from Leo Pharma. Dr. Demelo-Rodríguez has received speaker’s honoraria from the following pharmaceutical companies: ROVI, Bayer, Techdow, Menarini, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers, Sanofi, and Daichii-Sankyo. In addition, he has engaged in advisory consultancy work for Techdow, Leo Pharma, and Pfizer. The rest of the authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Di Nisio M, van Es N, Büller HR. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The Lancet. 2016;388(10063):3060-73.

- Khan F, Tritschler T, Kahn SR, Rodger MA. Venous thromboembolism. The Lancet. 2021;398(10294):64-77.

- Heit JA. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(8):464-74.

- Raskob GE, Angchaisuksiri P, Blanco AN, Buller H, Gallus A, Hunt BJ, et al. Thrombosis: A Major Contributor to Global Disease Burden. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(11):2363-71.

- Di Minno G, Mannucci PM, Tufano A, Palareti G, Moia M, Baccaglini U, et al. The first ambulatory screening on thromboembolism: a multicentre, cross-sectional, observational study on risk factors for venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(7):1459-66. [CrossRef]

- Tang L, Wu YY, Lip GYH, Yin P, Hu Y. Heart failure and risk of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3(1):e30-44. [CrossRef]

- Zannad F, Stough WG, Regnault V, Gheorghiade M, Deliargyris E, Gibson CM, et al. Is thrombosis a contributor to heart failure pathophysiology? Possible mechanisms, therapeutic opportunities, and clinical investigation challenges. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(5):1772-82. [CrossRef]

- Kim JH, Shah P, Tantry US, Gurbel PA. Coagulation Abnormalities in Heart Failure: Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Implications. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2016;13(6):319-28. [CrossRef]

- Obradovic S, Dzudovic B, Subotic B, Matijasevic J, Mladenovic Z, Bokan A, et al. Predictive value of heart failure with reduced versus preserved ejection fraction for outcome in pulmonary embolism. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7(6):4061-70. [CrossRef]

- Ng TMH, Tsai F, Khatri N, Barakat MN, Elkayam U. Venous Thromboembolism in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure: Incidence, Prognosis, and Prevention. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3(1):165-73.

- Smilowitz NR, Zhao Q, Wang L, Shrestha S, Baser O, Berger JS. Risk of Venous Thromboembolism after New Onset Heart Failure. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):17415. [CrossRef]

- Darze ES, Latado AL, Guimarães AG, Guedes RAV, Santos AB, de Moura SS, et al. Acute Pulmonary Embolism Is an Independent Predictor of Adverse Events in Severe Decompensated Heart Failure Patients. Chest. 2007;131(6):1838-43. [CrossRef]

- Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, Lip GYH. A Novel User-Friendly Score (HAS-BLED) To Assess 1-Year Risk of Major Bleeding in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Chest. 2010;138(5):1093-100. [CrossRef]

- Franco Moreno AI, García Navarro MJ, Ortiz Sánchez J, Martín Díaz RM, Madroñal Cerezo E, De Ancos Aracil CL, et al. A risk score for prediction of recurrence in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism (DAMOVES). Eur J Intern Med. 2016;29:59-64.

- Aujesky D, Obrosky DS, Stone RA, Auble TE, Perrier A, Cornuz J, et al. Derivation and Validation of a Prognostic Model for Pulmonary Embolism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(8):1041-6. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez D. Simplification of the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index for Prognostication in Patients With Acute Symptomatic Pulmonary Embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(15):1383. [CrossRef]

- Laporte S, Mismetti P, Décousus H, Uresandi F, Otero R, Lobo JL, et al. Clinical Predictors for Fatal Pulmonary Embolism in 15 520 Patients With Venous Thromboembolism: Findings From the Registro Informatizado de la Enfermedad TromboEmbolica venosa (RIETE) Registry. Circulation. 2008;117(13):1711-6.

- Quintero-Martinez JA, Dangl M, Uribe J, Vasquez MA, Vergara-Sanchez C, Albosta M, et al. Impact of Chronic Heart Failure on Acute Pulmonary Embolism in-Hospital Outcomes (From a Contemporary Study). Am J Cardiol. 2023;195:17-22. [CrossRef]

- Piazza G, Goldhaber SZ, Lessard DM, Goldberg RJ, Emery C, Spencer FA. Venous Thromboembolism in Heart Failure: Preventable Deaths During and After Hospitalization. Am J Med. 2011;124(3):252-9. [CrossRef]

- Mebazaa A, Spiro TE, Büller HR, Haskell L, Hu D, Hull R, et al. Predicting the Risk of Venous Thromboembolism in Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure. Circulation. 2014;130(5):410-8. [CrossRef]

- Jones NR, Roalfe AK, Adoki I, Hobbs FDR, Taylor CJ. Survival of patients with chronic heart failure in the community: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21(11):1306-25. [CrossRef]

- Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(3):267-315.

- Franco L, Becattini C, Beyer-Westendorf J, Vanni S, Nitti C, Re R, et al. Definition of major bleeding: Prognostic classification. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(11):2852-60. [CrossRef]

- Monreal M, Muñoz-Torrero JFS, Naraine VS, Jiménez D, Soler S, Rabuñal R, et al. Pulmonary Embolism in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease or Congestive Heart Failure. Am J Med. 2006;119(10):851-8. [CrossRef]

- Bechlioulis A, Lakkas L, Rammos A, Katsouras C, Michalis L, Naka K. Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Heart Failure. Curr Pharm Des. 2022;28(7):512-20. [CrossRef]

- Piazza G, Goldhaber SZ. Pulmonary Embolism in Heart Failure. Circulation. 2008;118(15):1598-601. [CrossRef]

- Fang MC, Go AS, Chang Y, Borowsky LH, Pomernacki NK, Udaltsova N, et al. A New Risk Scheme to Predict Warfarin-Associated Hemorrhage. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(4):395-401. [CrossRef]

- Ruíz-Giménez N, Suárez C, González R, Nieto J, Todolí J, Samperiz Á, et al. Predictive variables for major bleeding events in patients presenting with documented acute venous thromboembolism. Findings from the RIETE Registry. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100(07):26-31. [CrossRef]

- Nishimoto Y, Yamashita Y, Morimoto T, Saga S, Amano H, Takase T, et al. Validation of the VTE-BLEED score’s long-term performance for major bleeding in patients with venous thromboembolisms: From the COMMAND VTE registry. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(3):624-32. [CrossRef]

- Klok FA, Hösel V, Clemens A, Yollo WD, Tilke C, Schulman S, et al. Prediction of bleeding events in patients with venous thromboembolism on stable anticoagulation treatment. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(5):1369-76. [CrossRef]

- Klok FA, Presles E, Tromeur C, Barco S, Konstantinides SV, Sanchez O, et al. Evaluation of the predictive value of the bleeding prediction score VTE-BLEED for recurrent venous thromboembolism. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2019;3(3):364-71. [CrossRef]

- Kuijer PMM, Hutten BA, Prins MH, Büller HR. Prediction of the Risk of Bleeding During Anticoagulant Treatment for Venous Thromboembolism. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(5):457. [CrossRef]

- Beyth RJ, Quinn LM, Landefeld CS. Prospective evaluation of an index for predicting the risk of major bleeding in outpatients treated with warfarin. Am J Med. 1998;105(2):91-9. [CrossRef]

- Ducrocq G, Wallace JS, Baron G, Ravaud P, Alberts MJ, Wilson PWF, et al. Risk score to predict serious bleeding in stable outpatients with or at risk of atherothrombosis. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(10):1257-65. [CrossRef]

- Abramov D, Kobo O, Mohamed M, Roguin A, Osman M, Patel B, et al. Management and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in patients with preexisting heart failure: an analysis of 2 million patients from the national inpatient sample. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2022;20(3):233-40. [CrossRef]

- Desai NR, Kennedy KF, Cohen DJ, Connolly T, Diercks DB, Moscucci M, et al. Contemporary risk model for inhospital major bleeding for patients with acute myocardial infarction: The acute coronary treatment and intervention outcomes network (ACTION) registry®–Get With The Guidelines (GWTG)®. Am Heart J. 2017;194:16-24. [CrossRef]

- Subherwal S, Bach RG, Chen AY, Gage BF, Rao SV, Newby LK, et al. Baseline Risk of Major Bleeding in Non–ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction: The CRUSADE (Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines) Bleeding Score. Circulation. 2009;119(14):1873-82.

- Tromp J, Westenbrink BD, Ouwerkerk W, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Samani NJ, Ponikowski P, et al. Identifying Pathophysiological Mechanisms in Heart Failure With Reduced Versus Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(10):1081-90. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(36):3599-726. [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Cruz P, Vivas D, Rojas A, Font R, Román-García F, Muñoz B. Valor pronóstico del antecedente de insuficiencia cardiaca en pacientes ingresados con tromboembolia pulmonar. Med Clin. 2016;147(8):340-4. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).