Submitted:

08 February 2024

Posted:

09 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Surveillance and privacy invasion: Drones equipped with cameras can invade privacy by peeping into private spaces, spying on individuals, or capturing unauthorized footage.

- Security threats: They can breach security perimeters of sensitive locations, such as airports, government buildings, or events, posing risks of espionage, smuggling, or even terrorist attacks.

- Harassment of disruption: Drones may harass individuals, disrupt public events, or interfere with emergency services by flying in restricted areas or causing disturbances.

- Delivery of harmful payloads: Malicious drones can be used to transport and deliver illegal substances, weapons, or hazardous materials to specific locations.

- Negligence can be performed by clueless or careless individuals. The first group do not know or understand the applicable regulations and they fly their drones in sensitive or prohibited areas. The second one knows the applicable regulations but may breach them through either fault or negligence. Consequently, their drones fly over sensitive of prohibited areas, but have no intent to disrupt or affect activities of critical infrastructures or others.

- Gross negligence can be committed by reckless individuals or activists/protesters. The first group knows the applicable regulations and restrictions, but deliberately does not follow the rules to pursue personal of professional gain. They can disrupt critical infrastructures or other activities by totally disregarding the consequences of their actions. The second group consists of individuals who, regardless of whether they know the applicable regulations and restrictions, actively seek to use drones to disrupt critical infrastructures or other activities. They have no intent to endanger human lives, although their acts could have unintended consequences to safety.

- Criminal / terrorist motivation. They are individuals who, regardless of whether they know the applicable regulations and restrictions, actively seek to use drones to interfere with the safety and security of critical infrastructures and other activities. Their acts are deliberate and show no regard for human lives and property. These individuals are to be regarded as being criminally motivated or even as terrorists.

2. Commercial counter drone solutions

3. Technology behind detection, tracking and identification

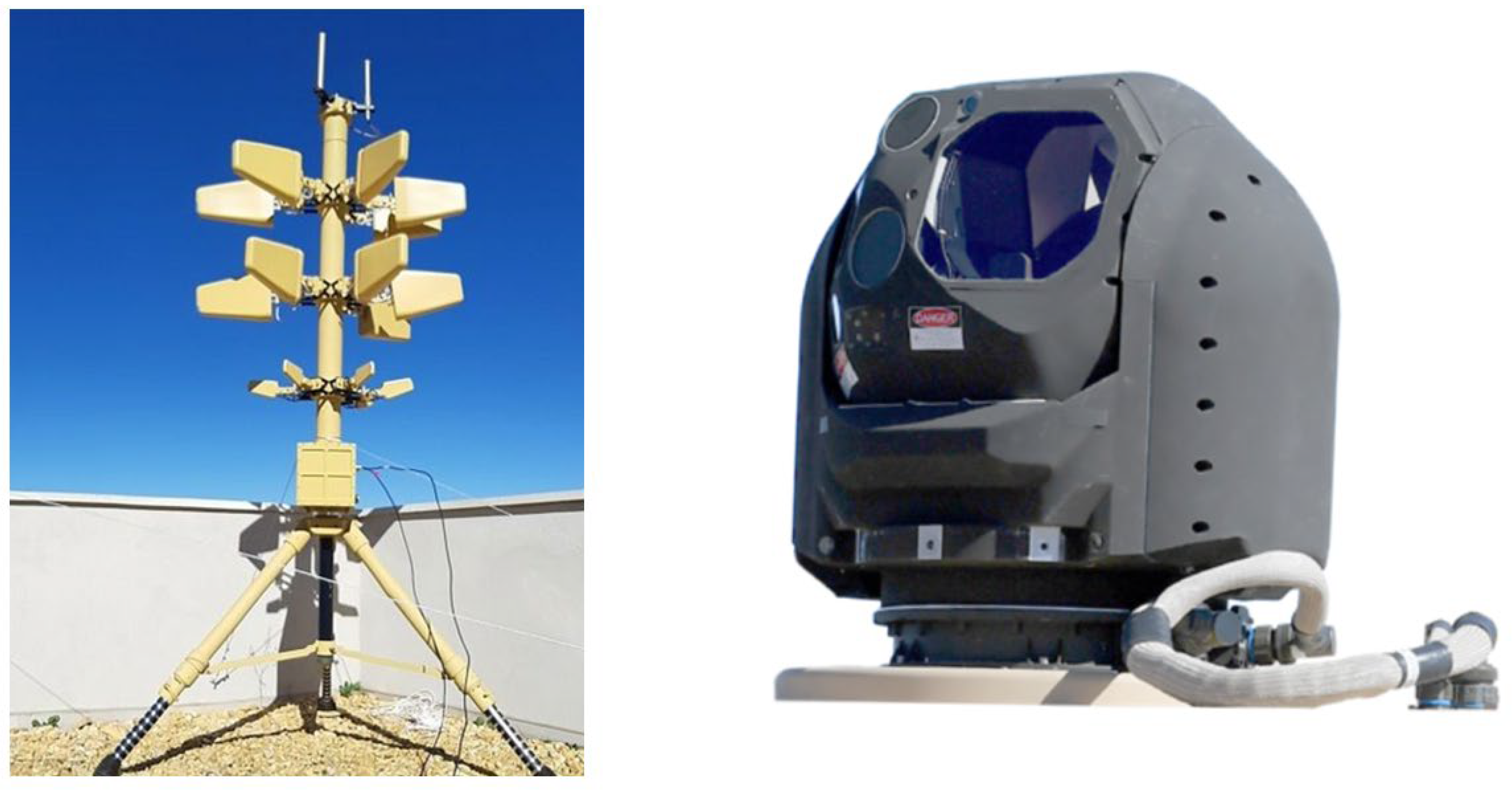

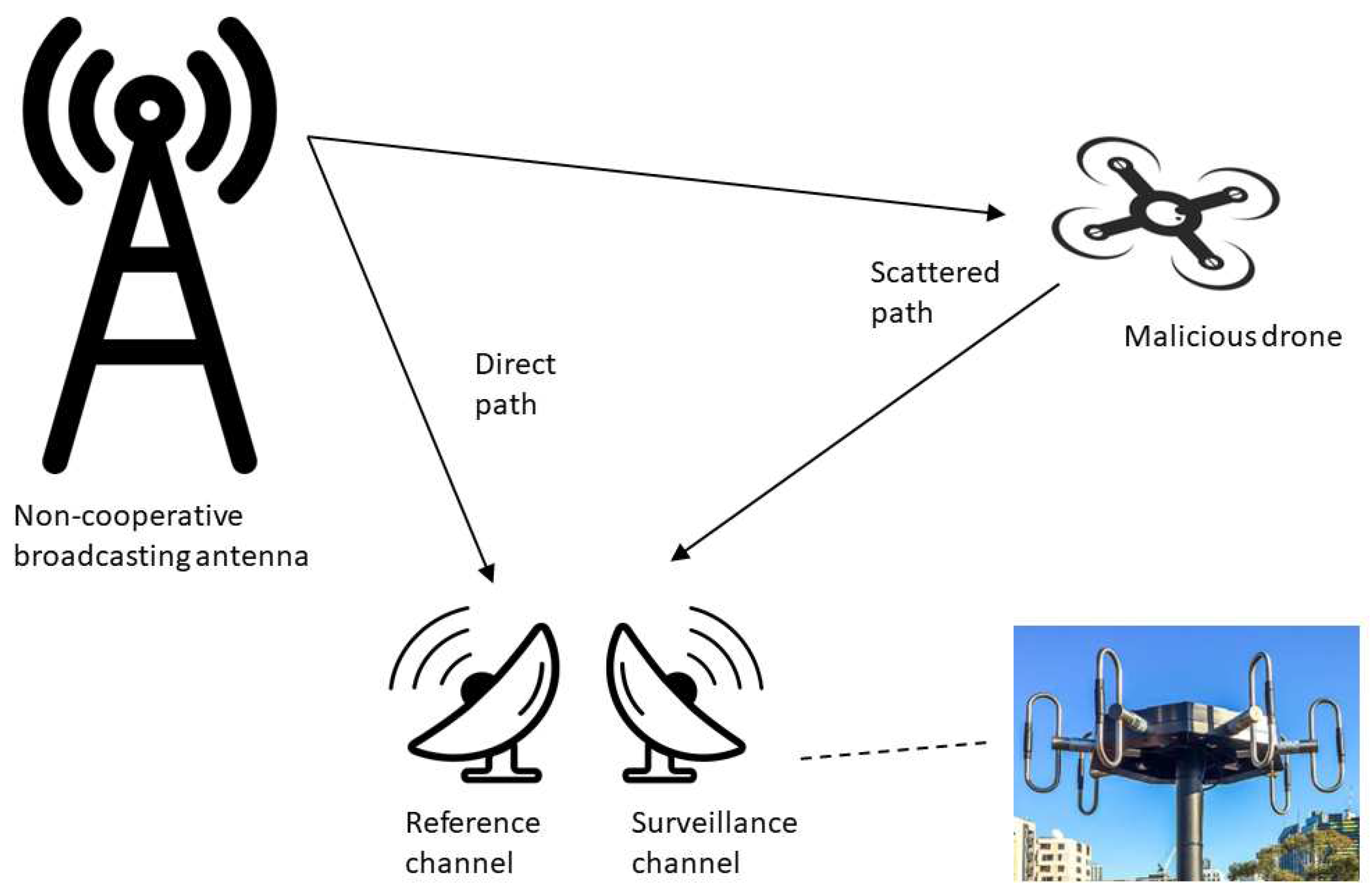

3.1. Passive radar

- Cooperative systems use signals from collaborative sources, like commercial radio or TV stations, where the broadcaster is aware and agrees to support the radar function.

- Non-cooperative systems work with ambient signals from untended sources without their explicit cooperation. They are more challenging as they need to extract information from signals not meant for radar purposes.

- Receivers: These are the main primary components that capture and process the incoming electromagnetic signals. They consist of antennas, RF (Radio Frequency) from-ends and digitizers. Receivers are designed to cover a broad spectrum of frequencies to capture signals from various sources like FM/AM radio, TV broadcasts or other radar systems.

- Signal processing units: Once the signals are captured, sophisticated signal processing algorithms are employed to extract relevant information. This includes filtering, correlation, waveform analysis, and target detection algorithms. Advanced digital signal processing techniques are crucial to separate the desired echoes from background noise or clutter.

- Target detection and tracking: After processing, the system identifies potential targets by analyzing the echoes or reflections within the received signals. Tracking algorithms then determine the position, velocity, and trajectory of the detected targets over time. These algorithms can employ techniques like Kalman filtering or data association methods to track multiple targets accurately.

- Database and signal library: Passive radar systems often rely on databases containing information about known transmitters and their characteristics. These data assists in target identification and discrimination, especially in non-cooperative systems. Signal libraries help in cross-referencing detected signals with known patterns to identify specific aircraft.

- Calibration and synchronization: Ensuring accurate detection and tracking requires precise calibration of receivers and synchronization of signals. Calibration procedures are essential to compensate for differences in receiver characteristics and environmental factors affecting signal propagation.

- Integration and networking: Depending on the application, passive radar systems may need to be combined with other sensor systems or radar networks for comprehensive situational awareness. Networking capabilities enable data sharing and integration with broader defense or surveillance systems.

- Power and cooling systems. Passive radar systems, especially those deployed in mobile or remote locations, require adequate power supply and cooling mechanisms to ensure continuous and reliable operations.

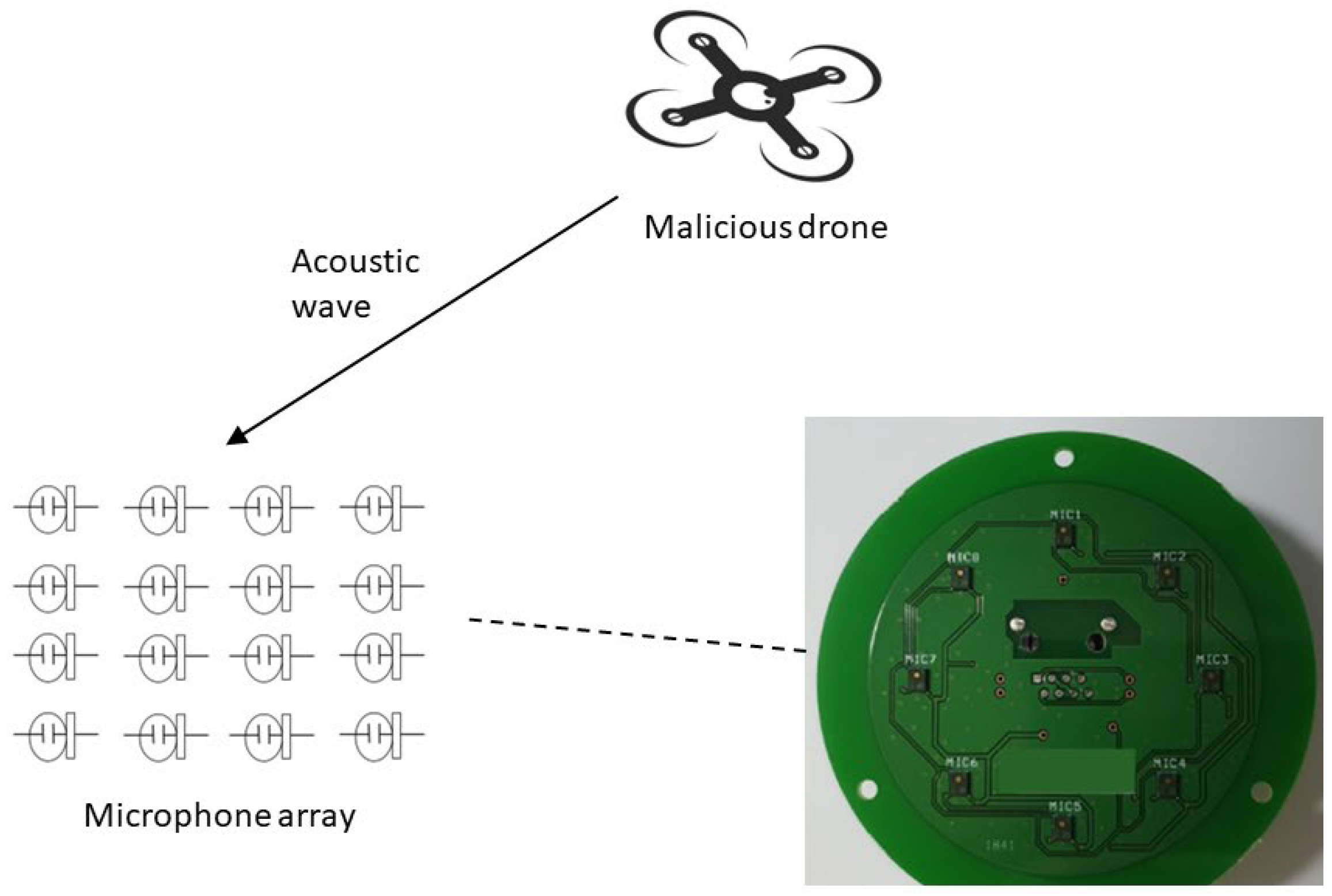

3.2. Microphones

- Detection mechanism: Acoustic sensors detect drones by capturing the distinct sound signatures produced by their motors, rotors, or propellers. Each drone type has a unique acoustic fingerprint, which helps in distinguishing between different models.

- Microphone arrays: These sensors often use arrays of microphones strategically placed to capture sound from various directions. The use of multiple microphones enables to determine the direction and location of the drone based on the differences in sound arrival times and intensities.

- Signal processing: Similar to passive radar systems, signal processing plays a vital role. Advanced algorithms analyze the captured sound data, filter out background noise, and extract relevant features to identify and classify drones. Machine learning and pattern recognition techniques are often employed for more accurate drone classification.

- Integration with other sensors: Acoustic sensors are frequently integrated into multi-sensor C-UAS systems. Combining acoustic sensors with radar, electro-optical or RF sensors enhances overall detection capabilities and provides redundancy in case of sensor limitations or environmental factors.

- Operational considerations: Acoustic sensors can operate effectively in various environments and conditions, including urban settings or areas with relatively high ambient noise. They offer a covert detection method, as they do not emit any signals, making them harder for adversaries to detect or evade.

- Challenges: Acoustic sensors may face challenges in environments with high background noise levels, weather effects, or when drones employ stealthy techniques like flying at low speeds or hovering quietly.

- Scalability and deployment: These sensors are often deigned to be scalable, allowing deployment in various configurations, from fixed installations to portable or mobile units suitable for rapid deployment in different scenarios.

- Regulatory considerations: Deployment of C-UAS systems, including acoustic sensors, often involves compliance with local regulations and privacy concerns regarding the interception of audio signals.

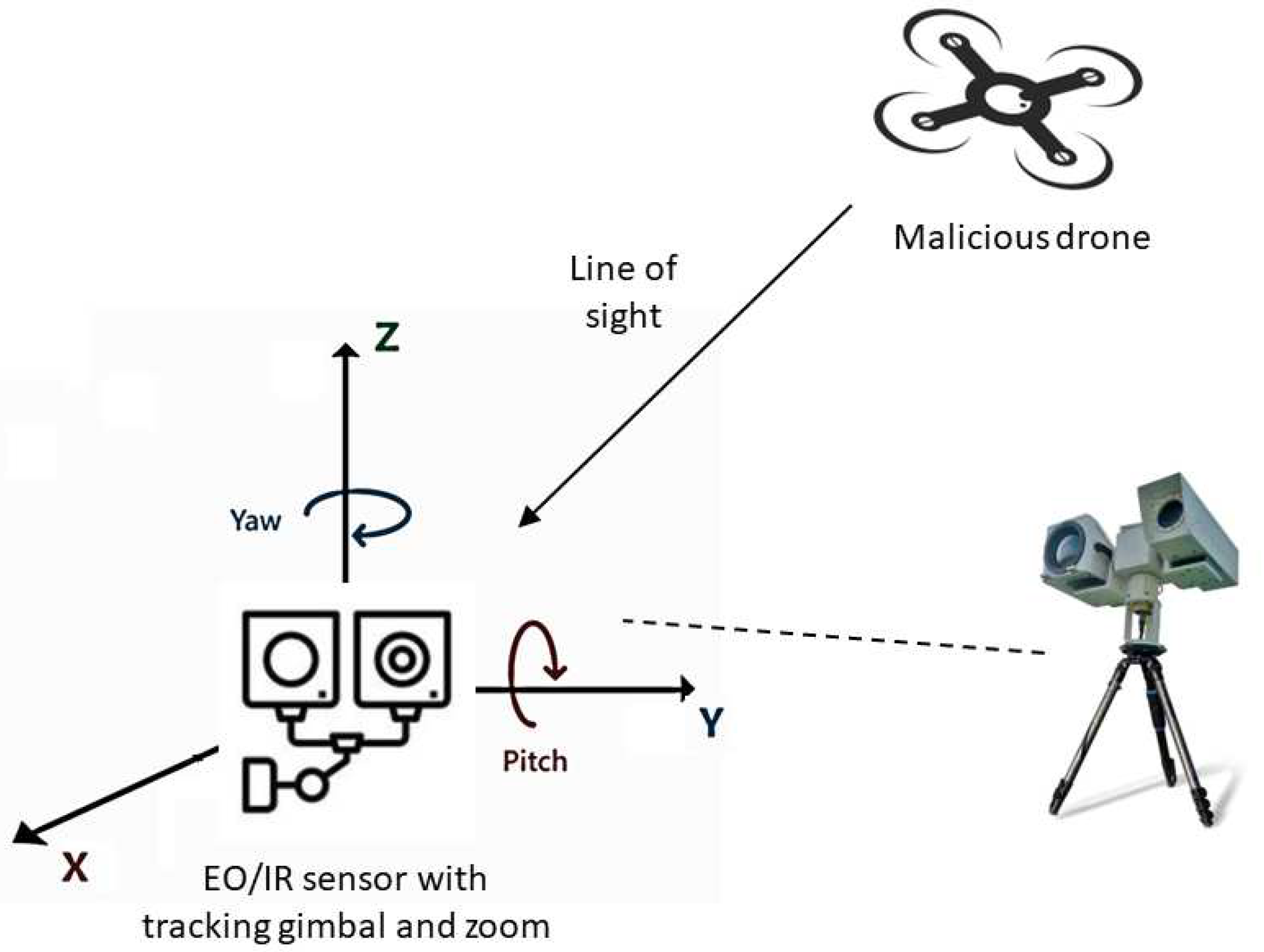

3.3. Electro-optical and infrared sensors

- Near Infrared (NIR) and Short-Wave Infrared (SWIR), with wavelengths between 700 to 1300 nm. These devices are effective in moonlit or starlit conditions and require some ambient light to function properly.

- Thermal Imaging, which operates in the Mid-Wave Infrared (MWIR) and Long-Wave Infrared (LWIR), commonly in the 7 – 17 μm range. These cameras provide images based on temperature differences and are effective even in total darkness or adverse weather conditions.

- Sensors (visible and infrared cameras). These are the primary devices capturing imagery in the visible and infrared spectra. Visible cameras provide visual information, while infrared cameras (thermal sensors) detect heat signatures emitted by drones or their components.

- Optics and lens assemblies: High-quality lenses and optical components focus and direct light onto the sensor arrays, ensuring clarity, sharpness, and optimal image quality.

- Signal processing units. Image and signal processors. These units process the captured data from the sensors. They perform tasks such as noise reduction, image enhancement, digital zoom, and fusion of visible and infrared imagery. Advanced algorithms analyze the processed data, extract relevant features, and aid in target detection, classification, and tracking.

- Tracking and identification: Target trackers use algorithms to maintain the position, trajectory, and other relevant information about detected drones in real-time. Identification features can be applied by analyzing shape, size, movement patterns, and thermal signatures.

- Data fusion and analysis: Fusion engines integrate data from various sensors (e.g., EI, IR radar, acoustic) to improve detection accuracy and reduce false alarms.

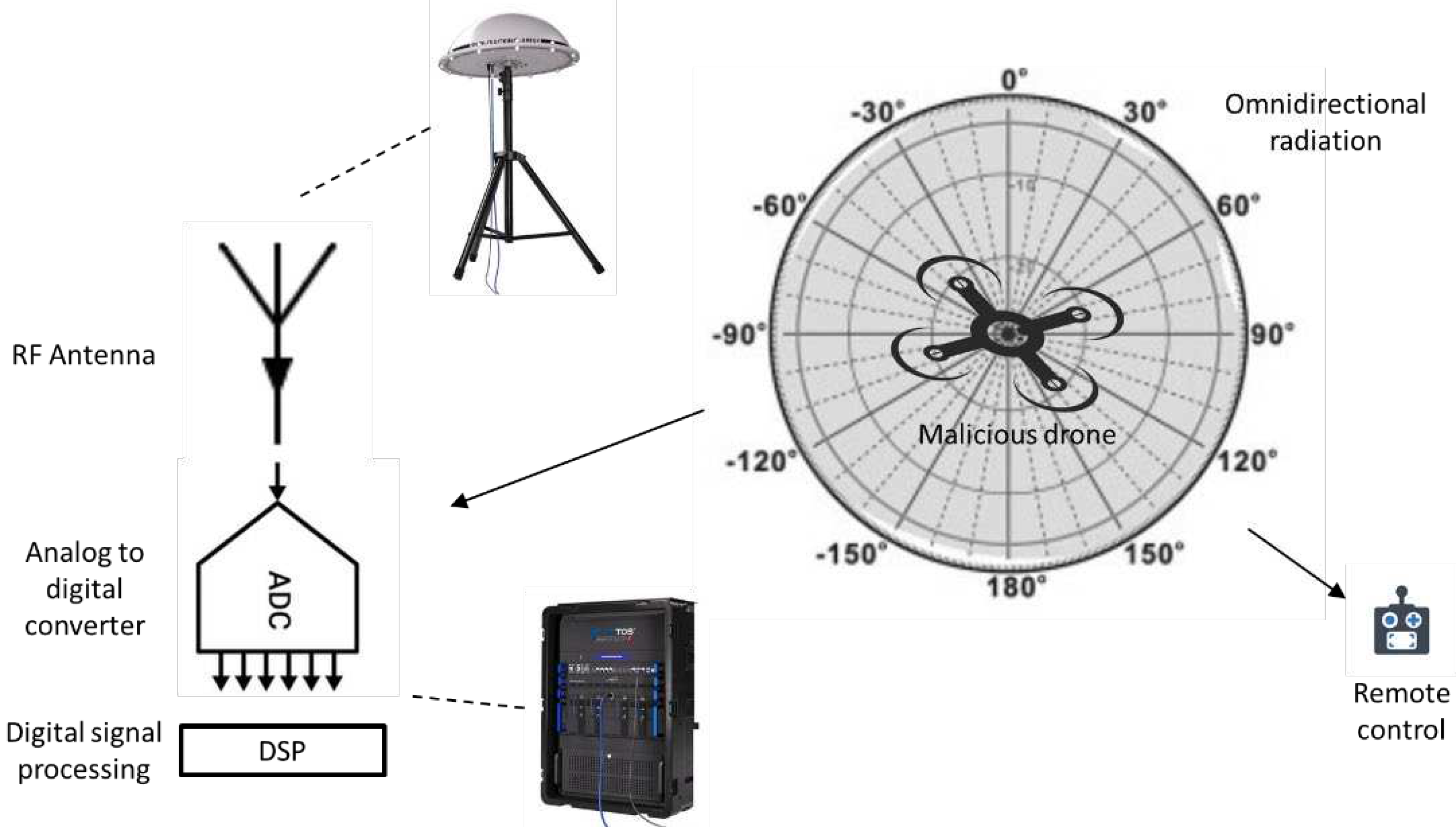

3.4. Radio Frequency (RF) signal analyzer

- The 2.4 GHz band is extensively used for various wireless communications, including Wi-Fi networks, Bluetooth devices, and consumer-grade drones. Its popularity stems from good signal penetration and range, making it a preferred choice for drone control.

- The 5.8 GHz band is often utilized by higher-end or advanced drones due to its capacity to handle more data, potentially offering better performance in areas with high interference.

- Spectrum Analyzers: These devices analyze a wide range of frequencies to detect signals across the RF spectrum, providing a comprehensive view of the frequency spectrum for the identification of signals used by drones within specific frequency bands. Modern spectrum analyzers often use digital signal processing for more accurate and faster analysis.

- Software-Defined Radios (SDR): SDRs offer flexibility by using software to define the functionality of the radio system. They allow for versatile signal processing and analysis, making them suitable for detecting and decoding various RF signals, including those used by drones. SDRs can be reconfigured and updated through software, adapting to changing signal patterns.

- Direction Finding Systems: RF detectors may incorporate direction-finding capabilities to determine the origin of drone control signals. This can be achieved using antenna arrays or specialized antennas to detect signal angles, providing information about the drone's location or the control station direction.

- Signal Processing and Pattern Recognition: Advanced RF detectors use sophisticated signal processing algorithms and pattern recognition techniques to distinguish drone communication signals from background noise or other legitimate wireless communications. Machine learning and artificial intelligence can be employed to accurately identify and classify these signals.

- Networked Sensors: In some cases, multiple RF detectors are strategically positioned and networked to create a more comprehensive detection system. These detectors work together to provide coverage over a wider area, allowing for triangulation and better tracking of drone movements.

- Frequency Hopping and Spread Spectrum Analysis: Some drones use frequency hopping or spread spectrum techniques to avoid detection. RF detectors need to be equipped with the capability to handle and analyze signals that rapidly change frequencies or use wider bandwidths.

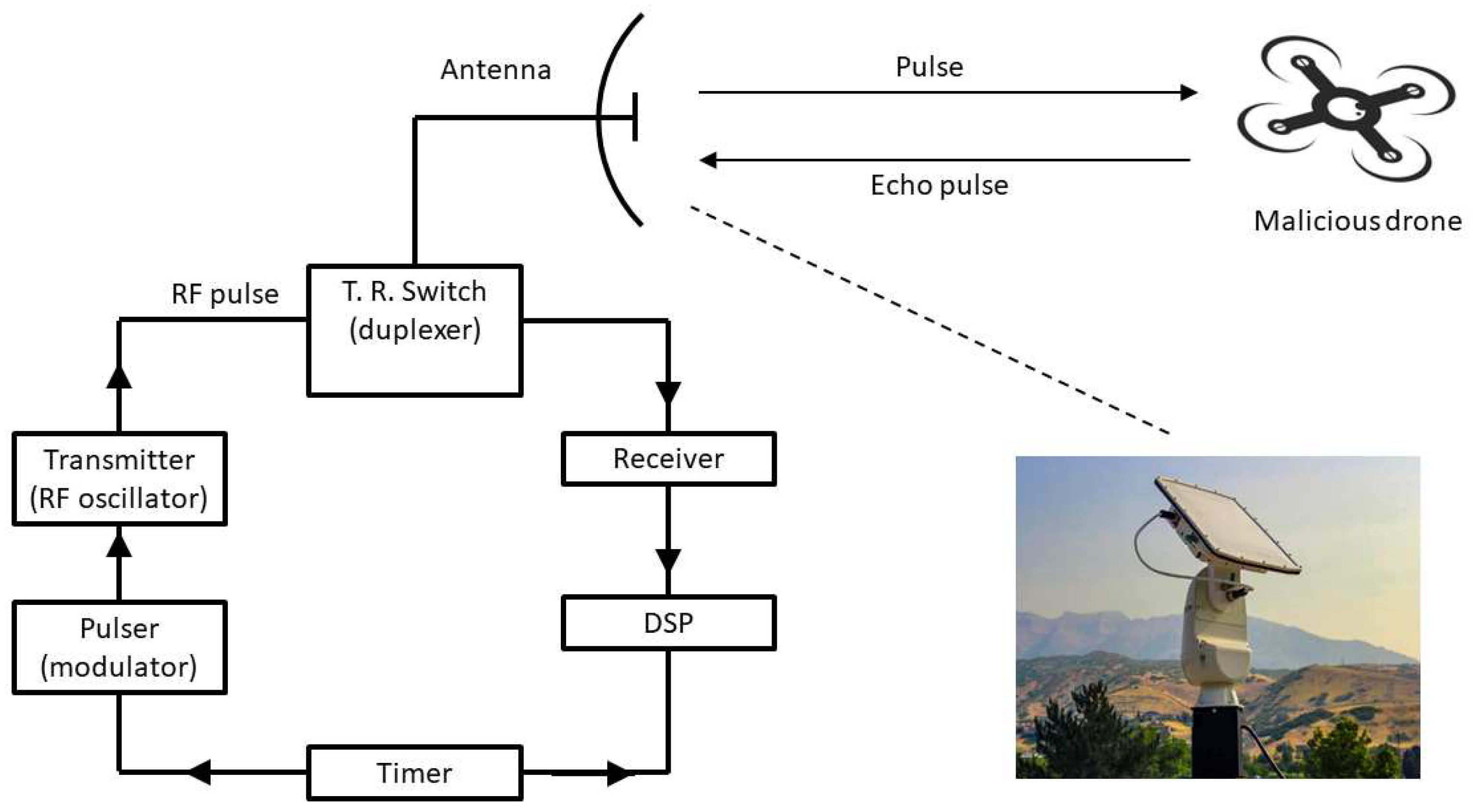

3.5. Active radar

- Transmitter: Emits electromagnetic pulses or continuous waves in a specific direction and frequency range, often using a directional antenna. These emitted waves travel through space. When the radar waves encounter a drone, they interact with the drone surface. Some of the energy is absorbed, some scattered, and the rest is reflected back towards the radar system.

- Receiver: Antennas or receiver capture the reflected signal (echoes) that return from the drone. These signals contain information about the drone position, speed, size, and other relevant characteristics.

- Signal processing unit: Processes the received signals to extract meaningful information. This involves analyzing the time delay, phase shift, and amplitude of the returned signals to determine the drone attributes, such as its distance, velocity, and direction.

- Radar systems can employ different techniques like pulse-Doppler, Frequency -Modulated Continuous-Wave (FMCW) or phased-array radar for improved accuracy, range, and capability to detect and track drones. Signal processing algorithms and machine learning models may be used to classify and differentiate drones from other objects, reducing false positives and improving the system overall effectiveness.

- Small radar cross section: Drones often have small physical dimension and lightweight construction, resulting in a limited radar cross-section. This makes them harder to detect compared to larger objects, requiring radar systems with high sensitivity and resolution.

- Low altitude and maneuverability: Drones can fly at low altitudes and execute erratic maneuvers, apperaring as dynamic and unpredictable targets in radar systems. Tracking such agile and swift movements accurately becomes challenging, especially for traditional radar setups optimized for larger aircrafts with lower maneuverability.

- Clutter and false positives: Radar systems can encounter clutter from various sources such as buildings, trees, birds, and other objects in the vicinity. Distinguishing between drones and these background objects or false targets is crucial to avoid false positives that may lead to unnecessary alerts or alarms.

- Radar cross section variability: The radar cross-section of a drone can vary significantly based on its orientation, material composition, and even flight mode (e.g., hovering, moving forward). This variability makes consistent and reliable detection challenging.

- Stealth technology: Some drones may employ stealth technology or features like radar-absorbing materials, reducing their radar signature intentionally. This makes them even more challenging to detect using conventional radar systems.

- Electronic countermeasures: Advanced drones may be equipped with electronic countermeasures to disrupt radar detection by emitting jamming signals or employing techniques to confuse radar systems, thereby evading detection.

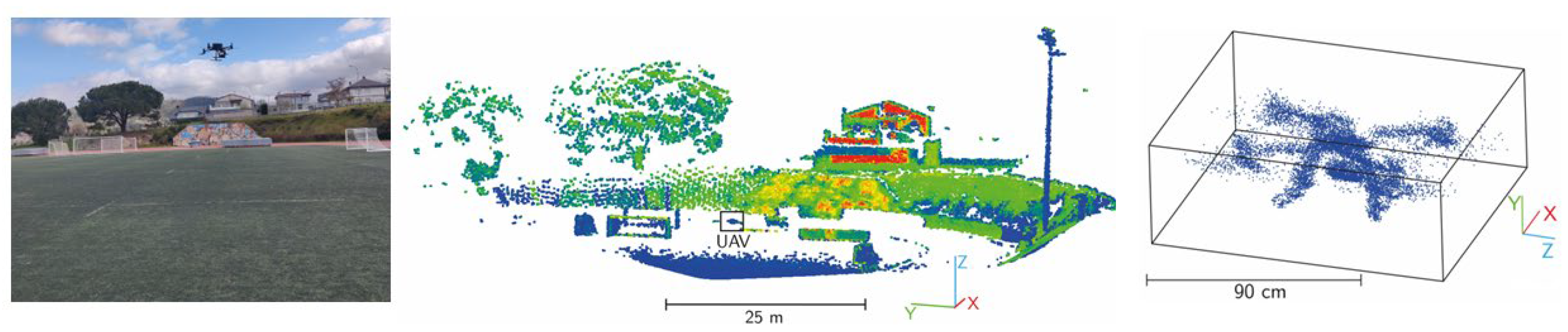

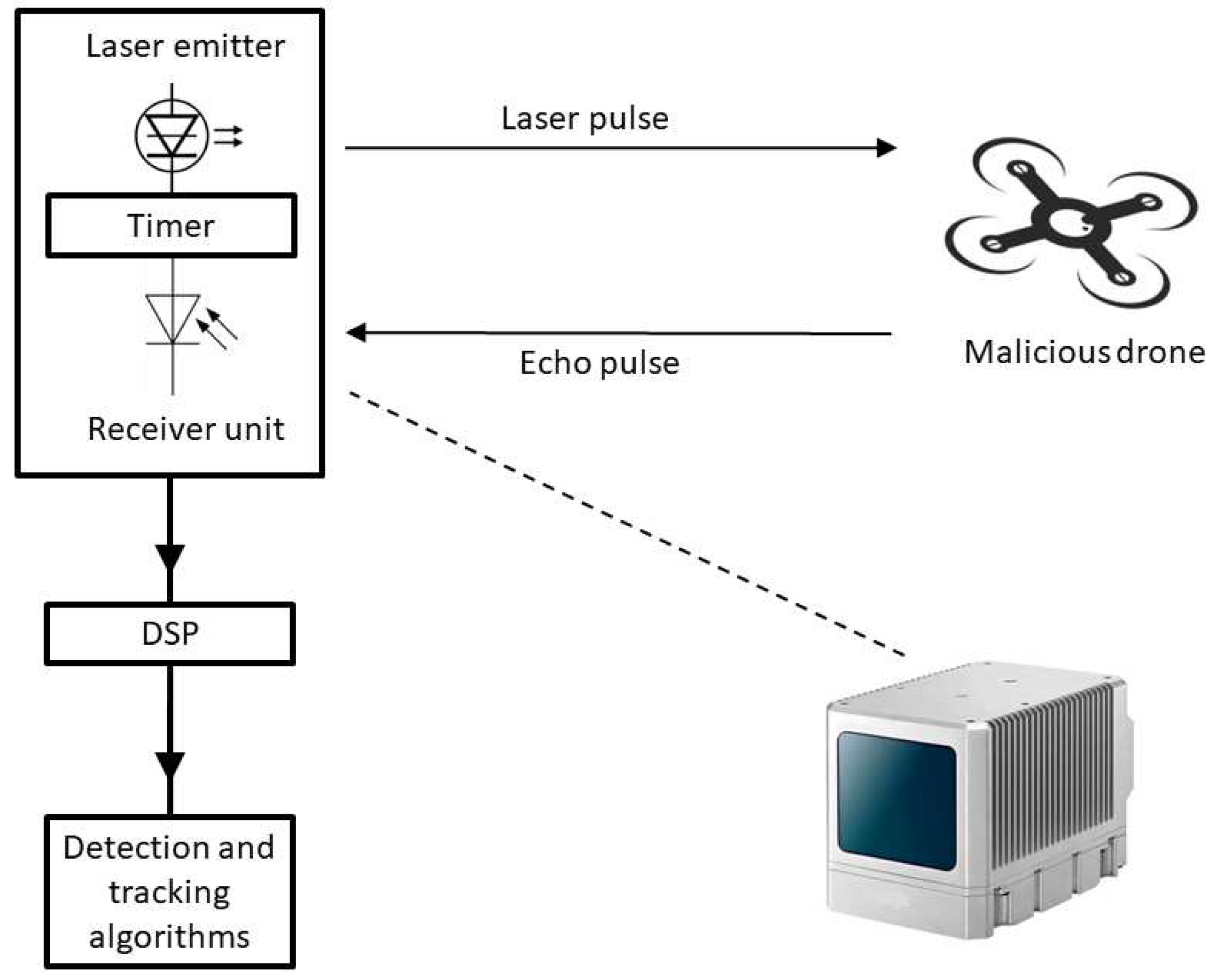

3.6. LiDAR

- Detection principle: LiDAR uses laser pulses to measure distances to objects calculating the time it takes for light to bounce back. It excels in providing highly accurate and precise 3D mapping of the environment. Radar utilizes radio waves to detect objects to detect objects by measuring the measuring the time it takes for radio waves to return after hitting the target. Radar has a longer detection range compared to LiDAR and can operate effectively in various weather conditions.

- Accuracy and resolution: LiDAR provides extremely high-resolution data, offering detailed 3D mapping of the environment with precise measurements. It is highly accurate in determining object shapes, sizes, and positions. Radar offers longer detection ranges compared to LiDAR but generally has lower resolution. While it can detect objects at greater distances, it generally provides less detailed information about the target characteristics.

- Target classification or differentiation: LiDAR can distinguish between different types of targets due to its high resolution. It can identify and classify objects more precisely, making it suitable for differentiating drones from other aerial or ground-based entities. Radar may struggle to differentiate between different types of objects at longer ranges due to lower resolution. It may detect objects but could have limitations in accurately classifying them.

- Environmental factors: LiDAR performs well in clear atmospheric conditions but might face challenges in adverse weather conditions like heavy fog or rain, as these conditions can interfere with light transmission. Radar is less affected by environmental factors like fog or rain compared to LiDAR because radio waves are less impacted by such conditions.

- Laser emitters: The system includes high-powered laser emitters capable of emitting laser pulses. These pulses are reflected in the environment and return to the sensor.

- Receiver unit: This component receives the reflected laser pulses from the environment, including any drones present in the monitored airspace. It measures the time it takes for the pulses to return.

- Digital signal processing: The received data undergoes signal processing to compute the time instant and intensity of the returning laser pulses. This processing includes calculating distances, angles, intensity, and other parameters necessary for 3D mapping and object identification.

- Scanning mechanism: The LiDAR system often includes a scanner that directs the laser pulses over a designated are. This mechanism can be static or rotating, enabling coverage of different angles and regions.

- Data fusion and analysis: The data collected from the LiDAR system are fused and analyzed to create a comprehensive 3D map or point cloud of the environment. This map includes the location and movement of detected drones.

- Detection and tracking algorithms: Specialized algorithms are employed to detect and track drones within the collected data. These algorithms differentiate between drones and other objects, calculate their trajectories, speeds, and potential threat levels.

3.7. Sensor fusion

4. Technology behind mitigation

4.1. RF jamming (soft kill)

- Frequency spectrum: Radio-controlled drones typically operate within specific frequency bands for communication between the drone and its remote controller. RF jamming exploits this by transmitting signals within the same frequency range, disrupting the normal communication.

- Waveform generation: RF jammers generate radiofrequency signals with sufficient power to interfere with or overwhelm the signals exchanged between the drone and its remote controller. These signals can be continuous or modulated in various ways.

- Signal strength and interference. The effectiveness of RF jamming relies on the strength of the interfering signal. If the jamming signal is stronger than the drone's control signal, it can disrupt the communication link, rendering the drone unable to receive commands or transmit data effectively.

- Types of jamming: Wideband jamming involves transmitting interference across a broad range of frequencies, affecting multiple communication channels simultaneously. Narrowband jamming targets a specific frequency, or a narrow range of frequencies used by the drone, allowing for more precise disruption.

- Jamming techniques. Continuous Wave (CW) jamming uses a constant signal transmitted on the target frequency to create a steady interference. Pulse jamming is based on intermittent bursts of jamming signals transmitted, disrupting communication intermittently.

- Electronic warfare principles. RF jamming is a subset of electronic warfare, which involves the use of electromagnetic energy to deny or disrupt an adversary's use of electronic devices. In the case of counter-drone applications, the aim is to deny the drone's operator control and communication.

- Legal and ethical considerations: While RF jamming can be an effective soft kill method, its use is subject to legal and ethical considerations. Jamming signals can unintentionally affect nearby communication systems, potentially causing interference with other devices operating in the same frequency band.

- Evolving technologies: Counter-drone RF jamming technologies continue to evolve. Some systems are designed to intelligently scan for and adapt to the frequency and modulation characteristics of the target drone's communication, enhancing their effectiveness against more sophisticated drones.

4.2. GPS spoofing (soft kill)

- Global positioning system basis: GPS is a satellite-based navigation system that provides location and time information to GPS receivers on Earth. The system relies on a network of satellites orbiting the Earth, each transmitting precise timing signals.

- GPS spoofing techniques: GPS Spoofing involves transmitting false GPS signals to deceive a drone's navigation system. The goal is to make the drone believe it is located in a different position than it actually is.

- Signal generation: Spoofing devices generate fake GPS signals that mimic the signals sent by GPS satellites. These signals are then transmitted to the targeted drone.

- Timing and pseudorandom noise code: GPS satellites broadcast signals that include precise timing information and a Pseudorandom Noise (PRN) code unique to each satellite. The receiver on the drone uses this information to calculate its position.

- Overpowering genuine signals: The spoofer's signals must be strong enough to overpower the genuine signals from GPS satellites received by the drone. If successful, the drone will use the fake signals for navigation.

- Manipulating coordinates: By transmitting altered position data, the spoofer can manipulate the drone's perceived location. This can lead to the drone deviating from its intended course or entering a failsafe mode, such as initiating a return-to-home procedure.

- Dynamic spoofing: Advanced GPS spoofing techniques involve dynamically adjusting the fake signals to match the movement of the drone. This helps maintaining the illusion of a consistent, inaccurate location and makes the spoofing harder to detect.

- Implications to drone navigation: GPS is a crucial component of many drone navigation systems. Spoofing can disrupt a drone's ability to navigate accurately, potentially leading to unintended consequences such as collisions, straying into restricted airspace, or violating safety protocols.

- Mitigation challenges: Detecting GPS spoofing can be challenging because drones typically rely heavily on GPS signals, and sophisticated spoofing methods may be designed to avoid detection.

- Legal and ethical considerations: The use of GPS spoofing raises legal and ethical concerns, as it can impact not only the targeted drone but also other GPS-reliant devices in the vicinity. Unauthorized manipulation of GPS signals may violate laws and regulations.

4.3. Communication signal interception (soft kill)

- Communication systems in UAS: Unmanned Aerial Systems rely on various communication protocols to function. This includes Radio Frequency (RF) communication for commands, telemetry, and possibly video transmission. Drones may use different frequency bands, such as 2.4 GHz or 5.8 GHz, for communication between the remote controller and the drone itself.

- Signal interception techniques: Intercepting drone signals involves the use of specialized equipment to capture and analyze the communication between the remote controller and the UAS. This equipment may include Software-Defined Radios (SDRs), antennas, and signal processing tools.

- Frequency spectrum analysis: Intercepting signals begins with a thorough analysis of the frequency spectrum used by the UAS. The interceptor needs to identify the specific frequencies on which the drone is communicating. This may involve scanning a range of frequencies to detect the signals emitted by the UAV and its controller.

- Decoding protocols: Once the signals are intercepted, the next step is to decode the communication protocols used by the drone. This involves understanding how commands are formatted, how telemetry data is transmitted, and, if applicable, how video signals are encoded. Decoding may require knowledge of encryption methods if the communication is secured.

- Data interpretation: After decoding the intercepted signals, analysts can interpret the data to understand the drone status, location, mission parameters, and any other relevant information. This intelligence can be crucial for assessing the threat level posed by the UAV and planning appropriate countermeasures.

- Counteraction strategies: Intercepted signals can be used to develop counteraction strategies. This may include deploying signal jammers to disrupt communication between the drone and its operator or taking over control of the drone by sending false commands. However, the latter approach requires a deep understanding of the drone's communication protocols.

- Legal and ethical considerations: Intercepting communication signals from drones raises legal and ethical concerns. Depending on jurisdiction, intercepting private communication may violate privacy laws, and interfering with drone operations could have legal consequences. Authorities must carefully consider the legality and ethical implications of using communication interception techniques.

4.4. Cyber-attacks (soft kill)

- UAV control systems: Unmanned Aerial Vehicles are equipped with electronic control systems that manage their flight, navigation, and communication. These systems often include software, firmware, and communication protocols that can be potential targets for cyber-attacks.

- Cyber-attack vectors: Cyber-attacks on UAS can take various forms. Malware injection consists of introducing malicious software into the drone control system to compromise its integrity and functionality. Denial of Service (DoS) attacks overload communication channels of the drone processing capabilities to disrupt its normal operation. Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks intercept and modify communication between the drone and its operator to gain unauthorized control or manipulate data. Finally, the exploitation of software vulnerabilities consists in the identification and exploitation of weaknesses in the software running on the drone control system.

- Targeting communication links: Drones rely on communication links between the operator and the aircraft itself. Cyber-attacks may focus on disrupting or manipulating these links. For instance, attackers might jam or interfere with Radio Frequency (RF) signals, or they could exploit vulnerabilities in the communication protocols.

- GPS spoofing via cyber means: Cyber-attacks can also be employed to conduct GPS spoofing, as discussed previously. By compromising the GPS signals received by the drone, attackers can manipulate its perceived location and potentially alter its flight path.

- Counteraction and mitigation: Cybersecurity measures to counter UAS threats involve implementing robust encryption, authentication, and intrusion detection systems. Regular software updates and patch management are crucial to fixing vulnerabilities that could be exploited in cyber-attacks. Additionally, network segmentation and firewalls can help isolating and protecting critical components of UAV control systems.

- Ethical and legal implications: Performing cyber-attacks on UAS for countermeasures must adhere to legal and ethical standards. Unauthorized access to or manipulation of drone systems may violate laws, and ethical considerations should be taken into account to ensure responsible and lawful use of cyber capabilities.

- Ongoing research and development: As the field of UAS evolves, ongoing research and development efforts are essential to stay ahead of potential cyber threats. This includes analyzing emerging attack vectors, developing robust cybersecurity solutions, and collaborating with experts in both drone technology and cybersecurity.

4.5. Directed energy weapons (DEW) (soft kill)

- Principles of directed energy weapons: Directed energy weapons utilize focused beams of electromagnetic energy, such as lasers or microwaves, to achieve their intended effects. These energy beams can be precisely directed and controlled, providing a high level of accuracy.

- Laser-based directed energy weapons: High-energy lasers, often based on solid-state, fiber, or chemical laser technologies, are employed in DEWs for countering UAS. The laser beam is focused onto the target, typically a vital component of the UAV such as its propulsion system, electronics, cameras, or structural elements.

- Microwave-based directed energy weapons: Microwave-based DEWs use generators to produce intense microwave radiation. Microwaves can interact with the electronic systems of the UAS, disrupting or damaging components like communication systems, sensors, or avionics.

- Target tracking and engagement: DEWs are equipped with advanced sensor systems, such as radar or optical trackers, to detect and track UAVs in real-time. The directed energy beam is precisely directed toward the UAV based on the real-time tracking data, ensuring accurate targeting.

- Effects on UAS: Directed energy weapons can cause structural damage to UAVs by heating and melting critical components. The intense energy can disrupt or damage electronic systems on board, rendering the UAS inoperable.

- Range and limitations: The effective range of DEWs varies depending on the type and power of the weapon. High-energy lasers can have relatively long ranges. However, atmospheric conditions, such as humidity and turbulence, can affect the performance of directed energy weapons.

- Non-lethal options: Directed energy weapons can be designed with varying power levels to offer non-lethal options. Low-power settings may be used for disabling or disrupting UAS without causing permanent damage.

- Ethical and legal considerations: The use of directed energy weapons for countering UAS raises ethical and legal considerations. Ensuring compliance with international laws and rules of engagement is essential.

4.6. Acoustic countermeasures (soft kill)

- Principles of acoustic countermeasures: Acoustic countermeasures leverage the principles of sound propagation and detection to interact with unmanned aerial systems. These countermeasures typically include both detection systems and devices that generate acoustic signals for disruption.

- Acoustic detection systems: Acoustic countermeasures often involve the use of microphones and other sensors to detect the sound signatures produced by UAVs. These sensors can be strategically placed to cover areas where drone activity is expected. Advanced signal processing techniques are employed to distinguish the acoustic signature of drones from background noise and other sounds. This helps in accurate detection and identification of UAVs.

- Acoustic disruption devices: Devices capable of emitting intense sound waves are used as disruptive tools. These can include speakers or transponders that generate specific frequencies or patterns. Acoustic countermeasures may exploit the sensitivity of UAS components, such as inertial sensors and communication systems, to specific frequencies. By emitting disruptive frequencies, the countermeasures aim to interfere with the normal operation of the drone.

- Types of acoustic disruption: Acoustic signals can be designed to interfere with the communication links between the drone and its operator, disrupting control signals. Intense acoustic signals may interfere with the sensors on board the UAV, affecting its ability to navigate or gather information. Acoustic countermeasures can also perturb the flight stability of the UAV by affecting its propulsion system or control surfaces.

- Detection range and limitations: The effectiveness of acoustic countermeasures depends on the detection range of the acoustic sensors and the distance over which disruptive signals can be effectively transmitted. Environmental conditions, such as wind and atmospheric absorption, can affect the propagation of acoustic signals and impact the performance of acoustic countermeasures.

- Integration with other countermeasures: Acoustic countermeasures are often used in conjunction with other counter-UAS technologies, such as radar systems, to provide a comprehensive defense against drone threats.

- Ethical and legal considerations: As with any counter-UAS technology, the use of acoustic countermeasures raises ethical and legal considerations. Authorities must ensure compliance with local regulations and international laws governing the use of such technologies.

4.7. Hard kill

- Projective-based hard kill: Kinetic energy method of hard kill involves using projectiles, such as bullets or specialized ammunition, to physically impact and disable the UAS. This approach requires precise targeting and accurate ballistic calculations to ensure that the projectile intercepts the UAV.

- Directed Energy Weapons (DEWs): High-energy lasers can be employed as directed energy weapons to deliver a focused beam of energy onto critical components of the UAV, causing damage or destruction. Microwave-based directed energy weapons can generate intense microwave radiation to disrupt or damage electronic components on the UAV.

- Explosive-based hard kill: Explosive devices, such as missiles or other munitions, can be employed to physically destroy the UAV. These countermeasures are designed to inflict sufficient damage to render the drone inoperable. Explosive devices may produce fragmentation effects that can effectively disable or destroy the UAV within a certain radius.

- Projectile and missile guidance systems: Hard kill methods often involve advanced guidance systems, such as radar or infrared homing, to ensure the accuracy of projectiles or missiles. These guidance systems enable real-time tracking of the UAV, allowing for precise targeting and interception.

- Range and limitations: The effectiveness of hard kill methods depends on the range of the countermeasure, the speed and agility of the UAV, and the accuracy of the targeting system. Payload capacity of the countermeasure, whether it's a projectile or explosive device, influences the ability to neutralize different types of UAS.

- Integration with sensor systems: Effective hard kill systems often integrate with sensor systems, such as radar and electro-optical sensors, to enhance target detection and tracking capabilities. Rapid data processing and analysis are crucial to ensure timely and accurate responses to UAS threats.

- Ethical and legal considerations: The use of hard kill methods raises ethical and legal considerations. Rules of engagement must be established to govern the use of lethal force against UAS, considering potential collateral damage and adherence to international laws.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- González-Jorge, H.; Martínez-Sánchez, J.; Bueno, M.; Arias, P. Unmanned aerial systems for civil applications: A review. Drones 2017, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konert, A.; Balcerzak, T. Military autonomous drones (UAVs)–from fantasy to reality. Legal and ethical implications. Transportation Research Procedia 2021, 59, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogili, U.R.; Deepak, B.B.V.L. Review on application of drone systems in precision agriculture. Procedia Computer Science 2018, 133, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemas, V.V. Coastal and environmental remote sensing from unmanned aerial vehicles: An overview. Journal of Coastal Research, 2015, 31, 1260–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.; Garg, D.; Narang, P.; Mishra, V. Drone-surveillance for search and rescue in natural disaster. Computer Communications 2020, 156, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, A.; Toy, J. Delivery by drone: An evaluation of unmanned aerial vehicle technology in reducing CO2 emissions in the delivery service industry. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2018, 61, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, S.; Moore, J.; Hovet, S.; Box, J.; Perru, J.; Kirsche, K.; Lewis, D.; Tse, A.T.H. State-of-the-art technologies for UAV inspections. IET Radar, Sonar and Navigation 2018, 12, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreps, S.E.; Wallace, G.P.R. International law, military effectiveness, and public support for drone strikes. Journal of Peace Research 2016, 53, 830–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Swarte, T.; Boufous, O.; Escalle, P. Artificial intelligence, ethics and human values: the cases of military drones and companion robots. Artificial Life and Robotics 2019, 24, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paucar, C.; Morales, L.; Pinto, K.; Sánchez, M.; Rodríguez, R.; Gutiérrez, M.; Palacios, L. Use of drones for surveillance and reconnaissance of military areas. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies 2018, 94, 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- General Atomics MQ-1 Predator. (accessed 16 01 2024). Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Atomics_MQ-1_Predator.

- General Atomics MQ-9 Reaper. (accessed 16 01 2024). Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Atomics_MQ-9_Reaper.

- Russia and Ukraine are fighting the first full-scale drone war. (accessed 16 01 2024). Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/12/02/drones-russia-ukraine-air-war/.

- How the drone war in Ukraine is transforming the conflict. https://www.cfr.org/article/how-drone-war-ukraine-transforming-conflict (accessed 16 01 2024). (accessed 16 01 2024). Available online: https://www.cfr.org/article/how-drone-war-ukraine-transforming-conflict.

- AeroVironment RQ-11 Raven. (accessed 16 01 2024). Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AeroVironment_RQ-11_Raven.

- Orlan-10. (accessed 16 01 2024). Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orlan-10.

- Bayraktar TB2. (accessed 16 01 2024). Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bayraktar_TB2.

- Forpost ISR. (accessed 16 01 2024). Available online: https://www.militaryfactory.com/aircraft/detail.php?aircraft_id=1486.

- Voskujil, M. Performance analysis and design of loitering munitions: A comprehensive technical survey of recent developments. Defence Technology 2022, 18, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAI Harop. (accessed 16 01 2024). Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IAI_Harop.

- AeroVironment Switchblade. (accessed 16 01 2024). Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AeroVironment_Switchblade.

- Bode, I.; Huelss, H.; Nadibaidze, A.; Qiao-Franco, G.; Watts, T.F.A. Prospects for the global governance of autonomous weapons: comparing Chinese, Russian and US practices. Ethics and Information Technology 2023, 25, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaacoub, J.P.; Noura, H.; Salman, O.; Chehab, A. Security analysis of drones systems: Attacks, limitations and recommendations. Internet of Things 2020, 11, 100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drone incident management at aerodromes. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.easa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/dfu/drone_incident_management_at_aerodromes_part1_website_suitable.pdf.

- UAS sightings report. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.faa.gov/uas/resources/public_records/uas_sightings_report.

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Song, H. Counter-unmanned aircraft systems (C-UAS): State of the art, challenges, and future trends. IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine 2021, 36, 4–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Joung, J.; Kim, J.; Kang, J.; Cho, Y.S. Protect your sky: A survey of counter unmanned aerial vehicle systems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 168671–168710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockheed Martin Morphius. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://lockheedmartin.com/content/dam/lockheed-martin/mfc/pc/morfius/mfc-morfius-pc-01.pdf.

- Raytheon Coyote. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.rtx.com/raytheon/what-we-do/integrated-air-and-missile-defense/coyote.

- Northrop Grumman M-ACE. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://cdn.prd.ngc.agencyq.site/-/media/wp-content/uploads/L-0900-MACE-Factsheet.pdf.

- General Dynamics Dedrone. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://gdmissionsystems.com/-/media/general-dynamics/ground-systems/pdf/counter-uas---dedrone/counter-unmanned-aerial-system-c-uas-datasheet.ashx.

- Highpoint Aerotechnologies Liteye. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.highpointaerotech.com/liteye.

- Blighter Surveillance Systems AUDS. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.blighter.com/wp-content/uploads/auds-datasheet.pdf.

- MSI-Defence Systems Terrahakw Paladin. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.msi-dsl.com/products/msi-ds-terrahawk-vshorad/.

- Thales Group EagleShield. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.thalesgroup.com/en/markets/defence-and-security/air-forces/airspace-protection/counter-unmanned-aircraft-systems.

- Elistair Orion 2.2 TW. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://elistair.com/solutions/tethered-drone-orion/.

- Elbit Systems ReDrone. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://elbitsystems.com/media/Redrone_45190331_25052023_WEB.pdf.

- Israel Aerospace Industries Drone Guard DG5. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.iai.co.il/p/eli-4030-drone-guard.

- Rafael Advanced Defense Systems Drone Dome. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.rafael.co.il/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Drone-Dome.pdf.

- CONTROP Precision Technologies TORNADO-ER. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.controp.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/TORNADO-ER.pdf.

- MCTECH RF Technologies MC Horizon. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://mctech-jammers.com/products/mc-horizon/.

- INDRA Crow. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.indracompany.com/en/anti-drone-system.

- SDLE Antridone. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.aeronauticasdle.com/products/.

- Leonardo FalconShield. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://uk.leonardo.com/documents/64103/6765824/Falcon+Shield+LQ+%28mm08605%29.pdf?t=1671446128764.

- SAAB AB 9LV. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.saab.com/globalassets/markets/australia/ip-23/20231030-auscms-cuas_final.pdf.

- HENSOLDT Xpeller. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.hensoldt.net/stories/xpeller-counter-uav-system/.

- Rheinmetall AG Drone Defence Toolbox. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.rheinmetall.com/en/products/air-defence/air-defence-systems/drone-defence-toolbox.

- Department13 Map13. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://department13.com/map13/.

- EOS Slinger. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://eos-aus.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/EOS-Defence-Slinger-flyer.pdf.

- ZALA Aero Group Aerorex. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.overtdefense.com/2019/06/27/zala-aero-rex-2-anti-drone-gun/.

- Roselektronika Zaschita. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.unmannedairspace.info/counter-uas-systems-and-policies/russian-system-uses-passive-signals-to-provide-almost-undetectable-counter-drone-capability/.

- China Electronic Group Corporation YLC-48. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202104/1221903.shtml.

- DJI Aeroscope. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://www.dji.com/es/aeroscope/info#specs.

- ASELSAN iHTAR. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://wwwcdn.aselsan.com/api/file/IHTAR_ANTI_DRONE_ENG.pdf.

- Kongsberg CORTEX Typhon. (accessed 17 01 2024). Available online: https://defence-industry.eu/kongsberg-to-produce-multiple-c-uas-air-defence-systems-for-ukraine/.

- Griffiths, H.; Baker, C. An introduction to passive radar. IEEE, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mattei, F. Enhanced radar detection of small remotely piloted aircraft in U-space scenario. Materials Research Proceedings 2023, 33, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Martelli, T.; Filippini, F.; Colone, F. Tackling the different target dynamics issues in counter drone operations using passive radar. IEEE International Radar Conference 2020, 09114618, 512–517. [Google Scholar]

- Souli, N.; Theodorou, I.; Kolios, P.; Ellinas, G. Detection and tracking of rogue UAS using a novel real-time passive radar system. Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems 2022, 181377, 576–582. [Google Scholar]

- Siewer, S.; Andalibi, M.; Bruder, S.; Buchholz, J.; Fernandez, R.; Rizor, S. Slew-to-cue electro-optical and infrared sensor network for small UAS detection, tracking and identification. AIAA Scitech Forum 2019, 225819. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu, C.; Minea, M.; Costea, I.M.; Chiva, I.C.; Semenescu, A. Development of an acoustic system for UAV detection. Sensors 2020, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Kim, M.Y. Positional estimation of invisible drone using acoustic array with A-shaped neural network. International conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication 2021, 9415272, 320–324. [Google Scholar]

- Kadyrov, D.; Sedunov, A.; Sedunov, N.; Sutin, A.; Salloum, H.; Tsyuryupa, S. Improvements to the Stevens drone acoustic detection system. Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics 2022, 2022 46, 45001. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.; Guo, X.; Peng, T.; Huang, X.; Hong, X. Drone detection and tracking system based on fused acoustical and optical approaches. Advanced Intelligent Systems 2023, 5, 2300251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivancic, J.; Karunasiri, G.; Alves, F. Directional resonant MEMS acoustic sensor and associated acoustic vector sensor. Sensors 2023, 23, 8217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.; Li, Y.; Ji, P.N.; Wang, T. Drone detection and localization using enhanced fiber-optic acoustic sensor and distributed acoustic sensing technology. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2023, 41, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flir 380, hd. (accessed 18 01 2024). Available online: https://www.flir.es/products/tacflir-380-hd/.

- Siewert, S.; Andalibi, M.; Bruder, S.; Gentilini, I.; Buchholz, J. Drone net architecture for UAS traffic management multi-modal sensor networking experiments. IEEE Aerospace Conference Proceedings 2018, 137510, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, T.K.; Yakimenko, O. Assessment of an effective range of detecting intruder aerial drone using onboard EO-sensor. International Conference on Control. Automation and Robotics 2020, 9108102, 653–661. [Google Scholar]

- Goecks, V.G.; Woods, G.; Valasek, J. Combining visible and infrared spectrum imagery using machine learning for small unmanned aerial system detection. Proceedings of SPIE 2020, 11394, 161094. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, T.; Widak, H.; Kollmann, M.; Buller, A.; Sommer, L.W.; Spraul, R.; Kroker, A.; Kaufmann, I.; Zube, A.; Segor, F.; et al. Drone detection, recognition, and assistance system for counter-UAV with VIS, radar, and radio sensors. Proceedings of SPIE 2022, 12096, 180323. [Google Scholar]

- Shovon, M.H.I.; Gopalan, R.; Campbell, B. A comparative analysis of deep learning algorithms for optical drone detection. Proceedings of SPIE 2023, 12701, 192563. [Google Scholar]

- Ojdanic, D.; Sinn, A.; Naverschnigg, C.; Schitter, G. Feasibility analysis of optical UAV detection over long distances using robotic telescopes. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2023, 59, 5148–5157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medaiyese, O.O.; Ezuma, M.; Lauf, A.P.; Guvenc, I. Wavelet transform analytics for RF-based UAV detection and identification system using machine learning. Pervasive and Mobile Computing 2022, 101569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Chakma, A.; Rahman, M.H.; Bin, M.R.; Alam, M.M.; Utama, I.B.K.Y.; Jang, Y.M. RF-enabled deep-learning-assisted drone detection and identification: An end-to-end approach. Sensors 2023, 23, 4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aouladhadj, D.; Kpre, E.; Deniau, V.; Kharchouf, A.; Gransart, C.; Gaquiere, C. Drone detection and tracking using RF identification signals. Sensors 2023, 23, 7650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almubairik, N.A.; El.Alfy, E.M. RF- based drone detection with deep neural network: Review and case study. Communications in Computer and Information Science 2023, 1969, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Riabukka, V.P. radar surveillance of unmanned aerial vehicles (Review). Radioelectronics and Communications Systems 2020, 63, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallentine, S.K.; Jost, R.J.; Reynolds, R.C. Autonomous spherical passive/active radar calibration system. Antenna Measurement Tchniques Association Symposium 2021, 175277. [Google Scholar]

- Schneebeli, N.; Leuenberger, A.; Wabeke, L.; Klobe, K.; Kitching, C.; Siegenthaler, U.; Wellig, P. Drone detection with a multistatic C-band radar. Proceedings International Radar Symposium 2021, 9466299, 171132. [Google Scholar]

- Abratkiewicz, K.; Malanowski, M.; Gajo, Z. Target acceleration estimation in active and passive radars. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2023, 16, 9193–9296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, I.; Pant, S.; Manning, M.; Kubanski, M.; Fox, P.; Rajan, S.; Patnaik, P.; Balaji, B. Time-frequency analysis using V-band radar for drone detection and classification. IEEE Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference 2023, 190690. [Google Scholar]

- Paschalidis, K.; Yakimenko, O.; Cristi, R. Feasibility of using 360º LiDAR in C-sUAS missions. IEEE International Conference on Control and Automation 2022, 181353, 172–179. [Google Scholar]

- Barisic, A.; Ball, M.; Jackson, N.; McCarthy, R.; Naimi, N.; Strassle, L.; Becker, J.; Brunner, M.; Fricke, J.; Markovic, L.; et al. Multi-robot system for autonomous cooperative counter-UAS missions: Desings, integration and field testing. IEEE International Symposium on Safety, Security, and Rescue Robotics, 8623. [Google Scholar]

- Aldao, E.; González-deSantos, L.M.; González-Jorge, H. LiDAR based detect and avoid system for UAV navigation in UAM corridors. Drones 2022, 6, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, P.J.; Larsen, H.E.; Pedersen, C. ; CW coherent detection lidar for micro-Doppler sensing and raster-scan imaging of drones. Optics Express 2023, 31, 7398–7412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abir, T.A.; Kuantama, E.; Han, E.; Dawes, J.; Mildren, R.; Nguyen, P. Towards robust lidar-based 3D detection and tracking of UAVs. Proceedings of the 9th ACM Workshop on Micro Aerial Vehicle Networks, Systems, and Applications 2023, 189616, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, W.; Govaers, F. Counter drones: Tensor decomposition-based data fusion and systems design aspects. Proceedings of the SPIE 2018, 10799, 107990. [Google Scholar]

- Kondru, D.S. R.; Celenk, M. ; Mitigation of target tracking errors and sUAS response using multi sensor data fusion. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 2018, 10884, 194–204. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, M.; Fernandez, L.; Chaves, P. Tracking and classification of aerial objects, Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social-Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering. 2020, 310, 264–276. [Google Scholar]

- Kotesware, R.S.; Jahan, K.; Kavitha, L. Implementation of unscented Kalman filter to autonomous aerial vehicle for target tracking. IEEE India Council International Subsections Conference 2020, 9344509, 204–209. [Google Scholar]

- Sie, N.J.; Xuan Seah, S.; Chan, J.J.; Yi, J.; Chew, K.H.; Hooi Chan, R.; Srigrarom, S.; Holzapfel, F.; Hesse, H. Vission-based drones tracking using correlation filters and linear integrated multiple model. International Conference on Electrical Engineering / Electronics, Computer, Telecommunications and Information Technology: Smart Electrical System and Technology 2021, 170892, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, N.S.J.; Srigrarom, S. Multi-camera multi-target drone tracking system with trajectory-based target matching and re-identification. International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems 2021, 9476845, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Son, S.; Kwon, J.; Kim, H.Y.; Choi, H. Tiny drone tracking framework using multiple trackers and Kalman-based predictor. Journal of Web Engineering 2021, 20, 2391–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montañez, O.J.; Suarez, M.J.; Fernández, E.A. Application of data sensor fusion using extended Kalman filter algorithm for identification and tracking of moving targets from LiDAR-Radar data. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitar, R.A.; Mohsen, A.; Seghrouchni, A.E. Intensive review of drones detection and tracking: Linear Kalman filter versus nonlinear regression, an analysis case. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2023, 30, 2811–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhadhrami, E.; Seghrouchni, A.E.F.; Barbaresco, F.; Zitar, R.A. Drones tracking adaptation using reinforcement learning: Proximal policy optimization. Proceedings International Radar Symposium 2023, 177483. [Google Scholar]

- Evaluating and comparing counter-drone (C-UAS) mitigation technologies. (accessed 19 01 2024). Available online: https://d-fendsolutions.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Mitigation-White-Paper.pdf.

- Castrillo, V.U.; Manco, A.; Pascarella, D.; Gigante, G. A review of counter-UAS technologies for cooperative defensive teams of drones. Drones 2022, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ga-Hye, J.; Ji-Hyun, L.; Yeon-Su, S.; Hyun-Ju, P.; Jou-Jin, L.; Sun-Woo, Y.; Il-Gu, L. Cooperative friendly jamming techniques for drone-based mobile secure zone. Sensors 2022, 22, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mykytyn, P.; Brzozowski, M.; Dyka, Z.; Lagendoerfer, P. GPS-spoofing attack detection mechanism for UAV swarms. Mediterranean Conference on Embedded Computing 2023, 190017. [Google Scholar]

- Souli, N.; Kolios, P.; Ellinas, G. Multi-agent system for rogue drone interception. IEEE Robotics and Automatic Letters 2023, 8, 2221–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.N.; Manickam, S.; Zia, S.S.; Abro, A.A.; Obaidat, M.; Uddin, M.; Abdelhaq, M.; Alsaqour, R. IoT empowered smart cybersecurity framework for intrusion detection in internet of drones. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 18422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja, L.J. High-energy laser directed energy weapons: Military doctrine and implications for warfare. Routledge Handbook of the Future of Warfare 2023, 353–363. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, M.; Zhang, L.; Shen, L.; Zou, X.; Han, J.; Lin, F.; Ren, K. Exploring practical acoustic transduction attacks on inertial sensors in MDOF systems. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameloot, C.; Papy, A.; Robbe, C.; Hendrick, P. Desing of a simulation tool for C-sUAS systems based on fragmentation unguided kinetic effectors. Proceeding of International Symposium on Ballistics 2023, 1, 1188–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Taillandier, M.; Peiffer, R.; Darut, G.; Verdy, C.; Regnault, C.; Pommies, M. Duality safety–Efficiency in laser directed energy weapon applications. Proceedings of SPIE 2023, 194555, 127390A. [Google Scholar]

- Muhaidheen, M.; Muralidharan, S.; Alagammal, S.; Vanaja, N. Design and development of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) directed artillery prototype for defense application. International Journal of Electrical and Electronics Research 2022, 10, 1086–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Anti drone jammer. (accessed 20 01 2024). Available online: https://www.thesmartcityjournal.com/en/companies/indra-produces-the-arms-anti-drone-solution.

- High-energy laser. (accessed 20 01 2024). Available online: https://prd-sc102-cdn.rtx.com/raytheon/-/media/ray/what-we-do/integrated-air-and-missile-defense/hel/pdf/ray_hel6-panel_data_ic23.pdf?rev=d79c063a461246b7bb752674d3534cb0&hash=D3597E8AA47D344FF8CC1465B5C75C1B.

| Company / product / country | Technology |

|---|---|

| Lookheed Martin Morfius [28] USA |

A reusable defensive C-UAS. Enables multi-engagement and swarm defeat at longer ranges than ground-based systems. No specific information about detection sensors, classification and tracking is provided. Mitigation action is categorized as hard kill. |

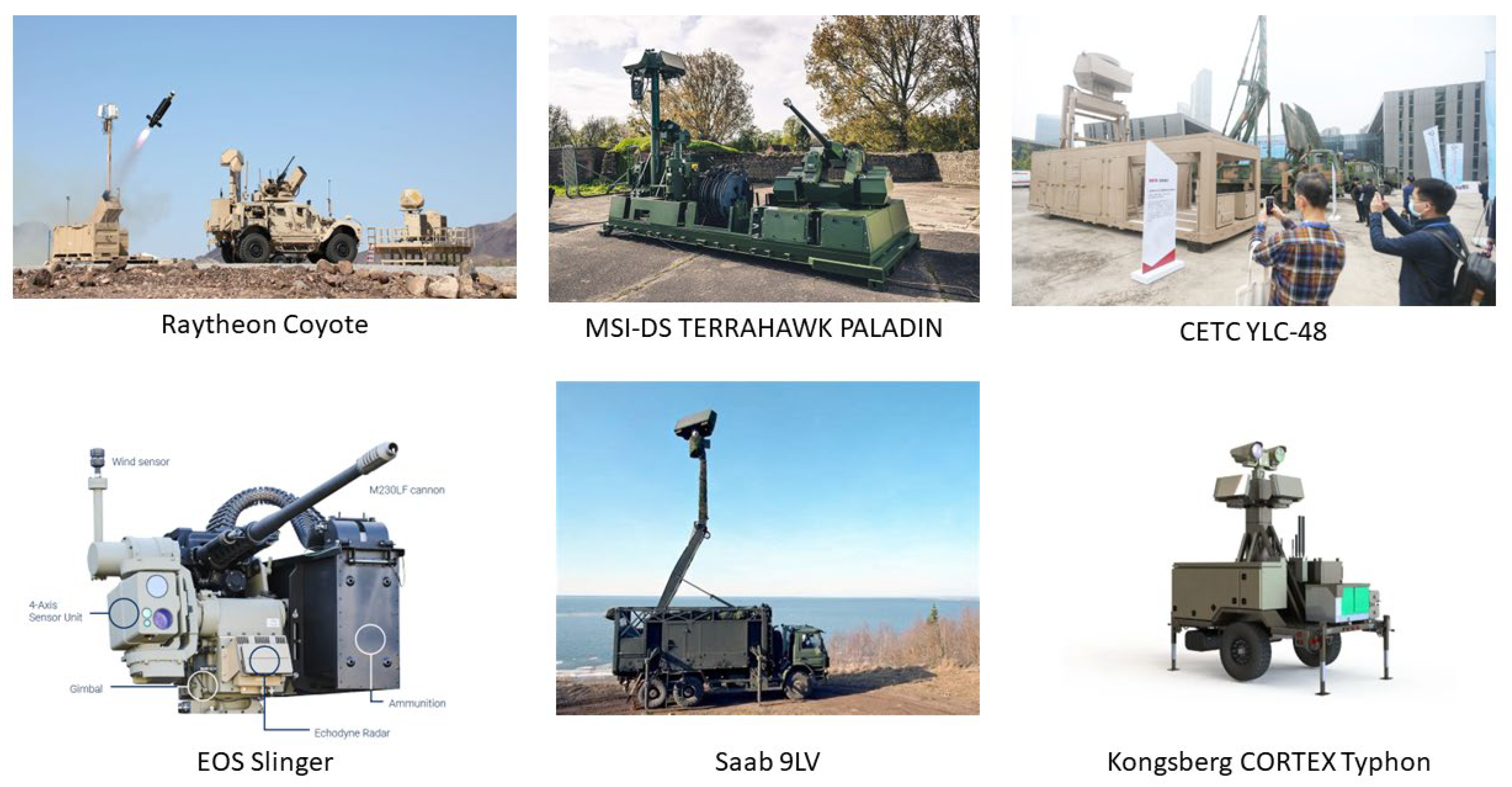

| Raytheon Coyote [29] USA |

A drone used for a near-term C-UAS solution. It is equipped with an advanced seeker and a warhead. It can be operated up to one hour and is designed for interchangeable payloads. No specific information about detection sensors, classification and tracking is provided. Mitigation actions are categorized as hard kill. |

| Northrop Grumman M-ACE [30] USA |

M-ACE is a modular ground-based C-UAS solution. It utilizes three-dimensional radar, radio frequency sensors, electro-optical/infrared cameras, global positioning systems, and secure radio for transmitting information over command-and-control networks. Mitigation actions (hard kill) are conducted by kinetic/non-kinetic defeat options (e.g., bushmaster cannon with advanced ammunition, directed energy solutions). |

| General Dynamics Dedrone [31] USA |

Denominated as Expedicionary Kit, it was developed in response to a mission need for a mobile ground C-UAS capability. It can be deployed in less than an hour. The system includes radio frequency sensors with a range up to 1.5 km (ideal conditions). It uses a classification engine which recognizes and classifies commercial, consumer and hobbyist drones. It is based on drone RF signature. Mitigation action (soft kill) is done by GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite Systems) and remote-control disruption of the system. |

| Highpoint Aerotechnologies Liteye [32] USA |

It is a portable perimeter defense system against autonomous, unmanned and multi-domain threats. The solution can be containerized for a rapid deploy. No specific information about sensing systems is provided. It includes AI & analytics for threat classification. Drone mitigation can be carried out through soft kill (high-precision directional RF jamming) or hard kill (hunter-seeker drones or kinetic weapons). |

| Blighter Surveillance Systems AUDS [33] UK |

AUDS is a strategic C-UAS system, designed to disrupt and neutralize drone threats. It includes detection, tracking and defeat capacities. It uses an air security radar (Ku-band) with a detection range of 10 km and minimum target size of 0.01 m2; and a digital camera tracker (color HD camera with 2.3 MP and optical zoom x30 and thermal camera with 640x512 pixels). Mitigation actions are performed with an intelligent software-defined RF inhibitor with a high gain quad-band antenna system (includes GNSS frequencies). |

| MSI-Defence Systems Terrahawk Paladin [34] UK |

It is a containerized, modular, remote-controlled and re-deployable C-UAS system. It includes sensors (electro optic) and effectors mounted under NATO-standard. Drone tracking is done using AI algorithms. Mitigation is carried out using the MSI-DS Terrahawk LW Series gun mount (hard kill). |

| Thales Group EagleShield [35] France |

It is an integrated nano, micro, mini and small drone countermeasures solution to protect and secure civil and military sites. It combines different sensors, such as radars and cameras, along with warfare technologies to detect, monitor and neutralize drones in the airspace. No specific information about the sensing and mitigation systems is provided. |

| Elistair Orion 2.2 TW [36] France |

It is a tethered drone station that can provide continuous surveillance and security for sensitive sites, offering a passive defense against unauthorized drones. Although it has no mitigation systems and is mainly based on an elevated observation platform, it is included in this work as it presents a disruptive concept far from most existing C-UAS systems. |

| Elbit Systems ReDrone [37] Israel |

ReDrone is a multi-layered defense against UAV threats. It presents multiple deployment options in mobile or stationary configurations. It utilizes different sensing technologies for detection and tracking, such as: 3D radar, electro-optical / infrared (EO/IR) day & night cameras, Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) and acoustic sensors. Mitigation actions are based on soft kill (jamming actuating through GNSS and communications channels). |

| Israel Aerospace Industries Drone Guard DG [38] Israel |

It is a multi-layer, multi-sensor, flexible and scalable solution designed to protect ground sites and mobile convoys. It presents an open architecture which enables the integration of radars, passive Communications Intelligence (COMINT), and EO sensors. Drone Guard DG5 incorporates AI based decision-making tools for target classification, thereby decreasing operator workload. It offers soft and hard kill mitigation. Soft kill is based on the disruption of drone communication and/or navigation protocol. Hard kill is performed with a drone-kill weapon system and high accuracy stabilized gunfire. |

| Rafael Advanced Defense Systems Drone Dome [39] Israel |

Drone Dome is a modular system which can be deployed as C-UAS mobile or stationary unit. The solution integrates radar, SIGINT/RF sensor, and EO sensor. Mitigation actions are based on a jammer (soft kill) which blocks the signal and command from the remote control. It also jams the video transmitted by the drone to the operator and the GNSS signal to disrupt the drone navigation and control. It can also be equipped with hard kill capacities. |

| CONTROP Precision Technologies TORNADO-ER [40] Israel |

It can detect and track drones from large distances up to 12 km. The system was developed for diverse land environmental conditions. Detection system is based on a gyro-stabilized electro-optical and thermal imaging sensors in combination with real-time video algorithms. Mitigation actions can include kinetic or non-kinetic countermeasure. |

| MCTECH RF Technologies MC Horizon [41] Israel |

This system includes a 3D pulse-Doppler radar, RF detection unit and EO/IR tracker. It provides a detection range between 3 km and 15 km with 360º coverage and a recognition range among 1.5 km and 10 km. Mitigation action is based on high power outdoor jamming system (soft kill) with an effective disruption range of 3 km. |

| INDRA Crow [42] Spain |

C-UAS system designed to detect and neutralize drone threats from microdrones (e.g., DJI Phantom) to large drones. It combines a detection radar, RF analysis, a EO sensors. Mitigation is carried out through RF and GNSS jamming (soft kill). |

| SDLE Antidrone [43] Spain |

A portable handheld solution that can be installed in vehicles and moving platforms. The manufacturer does not provide information about detection sensors, threat classification or tracking systems. Mitigation action are done disrupting remote control, telemetry, video link and GNSS navigation. |

| Leonardo FalconShield [44] Italy |

It is a scalable and modular system oriented to slow and small drones. It utilizes a radar and Electronic Surveillance Measures (ESM), combined with Electro Optical (EO) sensors and advanced Radio Frequency (RF) effector technology. Threat detection and tracking includes automatic capabilities to minimize the operator workload. Mitigation actions include electronic attack (capable to deny, disrupt or defeat UAV command, control, navigation) and UAV data downlinks. |

| SAAB AB 9LV [45] Sweden |

It enables the integration of a range of sensors for drone localization, classification, and recognition. These sensors integrate RF protocol detection, micro doppler radar, passive radar and EO/IR to support detection capabilities. Saab classification enables a hierarchy of drone sub-classification based on size, propulsion, and autonomy. It uses a multiple attribute decision making method to combine simple or complex rules, organic sensor classifications including image recognition, signature analysis and protocol detection, kinematic model-based classification, and movement pattern analysis. The threat identification function utilizes positive drone identification with associated trust metrics. It employs non-cooperative kinematic threat intent assessment and incorporates both anomaly detection and spatio-temporal movement pattern analysis. Mitigation actions support the integration of a variety of effectors to enable drone capability, including RF jammers and GNSS denial systems (soft kill) and high energy laser systems, physical capture, fouling drones and small to medium caliber guns with a high rate of fire and air-burst ammunition. |

| HENSOLDT Xpeller [46] Germany |

It is a modular system with includes radar for airspace monitoring and digital cameras, in combination with radio detectors, RF and GNSS countermeasures (soft kill). The system can be deployed in static, mobile and wearable form. |

| Rheinmetall AG Drone Defence Toolbox [47] Germany |

Rheinmetall deploys a combination of different radars in X and S band mode, passive emitter locators, commercial identification technologies (ADSB) and 360º cameras with laser range finders as well as infrared and time of flight cameras in various spectrums. The generated signals are processed, fused and classified in the command-and-control system. The mitigation is provided by a C-UAS jammer (soft kill). In the near future, they will provide autonomous catcher drones and high-energy lasers. |

| Department13 Map13 [48] Australia |

They offer a C-UAS solutions designed to detect, identify and mitigate drone threats using radio frequency-based techniques. There is not specific information about the detection sensors, classification algorithms and tracking capabilities, as well as the mitigation technologies used. No images of the system were found. |

| EOS Slinger [49] Australia |

The system combines 4-Axis electro optical sensor unit with an echodyne radar for drone detection and tracking. Mitigation action is done by a M230LF cannon with proximity sensing ammunition. |

| Zala Aero Group Aerorex [50] Russia |

It is mainly a mitigation system (soft kill) with three signal suppression modules for 2.4 GHz and 5.8 GHz frequencies, as well as for satellite navigation signal suppression. |

| Roselektronika Zaschita [51] Russia |

It consists of a set of passive sensors that do not emit any radiation. To detect the target, they use external signals, such as those from digital television, which bounce off the drone. Permission is not required for the use of radio frequencies, facilitating civilian use. However, passive sensors present lower detection capabilities. EO / IR sensors are likely not integrated in the system. Drone mitigation is performed by radio waves jamming. |

| China Electronic Technology Group Corporation YLC-48 [52] China |

YLC-48 system combines 3D S-band low-altitude surveillance radar and jamming technology to detect and counter unauthorized drones (soft kill). |

| DJI Aeroscope [53] China |

Aeroscope system is designed to identify and monitor drones in restricted areas, providing authorities with information to manage and control UAV operations. It covers a range up to 50 km. It analyzes the electronical signals between drones and remote control. The datasheet does not provide information about the sensing unit and the mitigation actions provided by the system |

| ASELSAN iHTAR [54] Turkey |

C-UAS system to neutralize mini and micro drone threats in urban and rural environments. It is used for protection of critical facilities, prevention of illegal border infiltration and safety of highly populated events. The system includes a Ku-band, pulsed Doppler radar with pulse compression (360º continuous or sector scanning, 30 rpm rotation speed and 40º instantaneous elevation coverage), thermal imaging system developed for long distance surveillance, and high-definition daytime cameras. Mitigation action is provided by a programmable RF jammer system (soft kill). |

| Kongsberg CORTEX Typhon [55] Norway |

It integrates a radar, electro optic and Teledyne FLIR thermal cameras for drone detection. The system works in combination with the Kongsberg Remote Weapon Station for threat mitigation (hard kill). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).