1. Introduction

The “Rice Bowl of Asia” regularly denotes as Thailand. Agriculture sector is considered as main driver for development [

1,

2] its contribution for livelihoods to more than 30 percent of the country’s population even agriculture accounts for 6 percent of Thailand’s GDP [

2,

3]. More than 70 percent of Thailand population live in rural area and the agriculture is their main source of income. The majority of farmers are smallholders. According to the study [

4], that hold farmland less than 10 rais approximately 50% and greater than 20 rais around 20 % while 40 % did not have land ownership.

To enable food self-sufficiency and to surplus agricultural products for export, the green revolution was introduced in Thailand in 1970 [

5,

6] and the adaptation of new mechanical equipment, heavy machine, hybrid seeds and chemical fertilizers vastly used in monoculture practice to meet the demands, both national and international [

2,

7]. However, this development greatly impacted on various aspects: for example, certain number of farmers face illness due to the side effected of using herbicide and insecticide. For income, the farmers become in the vicious poverty cycle due to the fact that the monoculture practice encourages the farmers buying seed, using chemical fertilizer, herbicide and insecticide and cultivation equipment; as a result, the intensity poverty increase due to over indebtedness [

8]. As such, the environment is degraded and highly contaminated, which affects aquatic animals and groundwater resource. Likewise, the substantial amount of greenhouse gas (GHG) is emitted in the production process, and this greatly contributes to global warming and climate change. [

1,

9,

10]

Due to facing severe impacts of conventional agriculture, the perception of “sustainable agriculture” in Thailand was first created and has been promoted since the 8th National Social and Economic Development Plan (1997 - 2001) to overcome the negative impact of conventional agriculture like insecure economic, environmental degradation, and chemical pollution [

2,

6,

11]. Whereas the alternative agriculture stream came into Thailand, the government foreseen the problems of promoting unfair and unsustainable practice to the smallholder farmers [

12], which led to the shifting towards chemical-free farming and to promote wellbeing for both farmers and consumers. The core concept of organic agriculture was formulated by IFOAM in concerning with health, ecology, fairness, and care, Organic agriculture has to include environmental, economic, and social aspects into the producing process. However, organic agriculture in Thailand mainly emphasizes on exporting [

13] so the third-party certification system is necessary. But the third-party certification system was relatively high cost with complicated operation and important documentation, so the smallholder farmers were excluded from the system because its amount of yields was low. [

14,

15]

The IFOAM developed the participatory guarantee system (PGS) in 2014 as an alternative farming practice and encouraged smallholder farmers to do this practice because it is the combination of indigenous knowledge, technology and science together with boosting farmers to participate in planning, expressing opinion, making decision, and farm assessing [

16]. It created a community- based organization which encourages exchange of knowledge with each other and acted as a tool for empowering smallholders [

17,

18] Thereby, the collaboration participation creates the institutionalized group. There are five important properties in producing process based on PGS: (1) natural resources management; (2) participating in both planning and conducting activities throughout the producing process; (3) the horizontal relationship of the group [

19]; (4) their assurance system; and (5) their network for exchanging information and knowledge.

The Northeast Region in Thailand is the largest region of the country, situated on Khorat Plateau and shallow basin, bordered by the Mekong River [

20]. Regarding to the proportion of poor people, the Northeastern region had number of poor people higher than other regions [

21]. The farmers in this region have an average annual income of only 62,751 baht, which is considerably lower compared to farmers in the central and southern regions, who earn an average of 329,579 and 210,397 bath per capita per year, respectively [

22]. The farmers in this region were encouraged to do organic farming based on PGS to improve their income, to ensure food security, and to restore their biodiversity. To narrow the research gap, this paper, nonetheless, only aims at comparing the smallholder farmers producing process of organic agriculture based on PGS practices in Northeastern Thailand. Like other areas of the country, performing agriculture are practices as a means of generating income. Although the Thai economic has noteworthy growth over the past decades, poverty and inequality endlessly exist in this part of the country.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

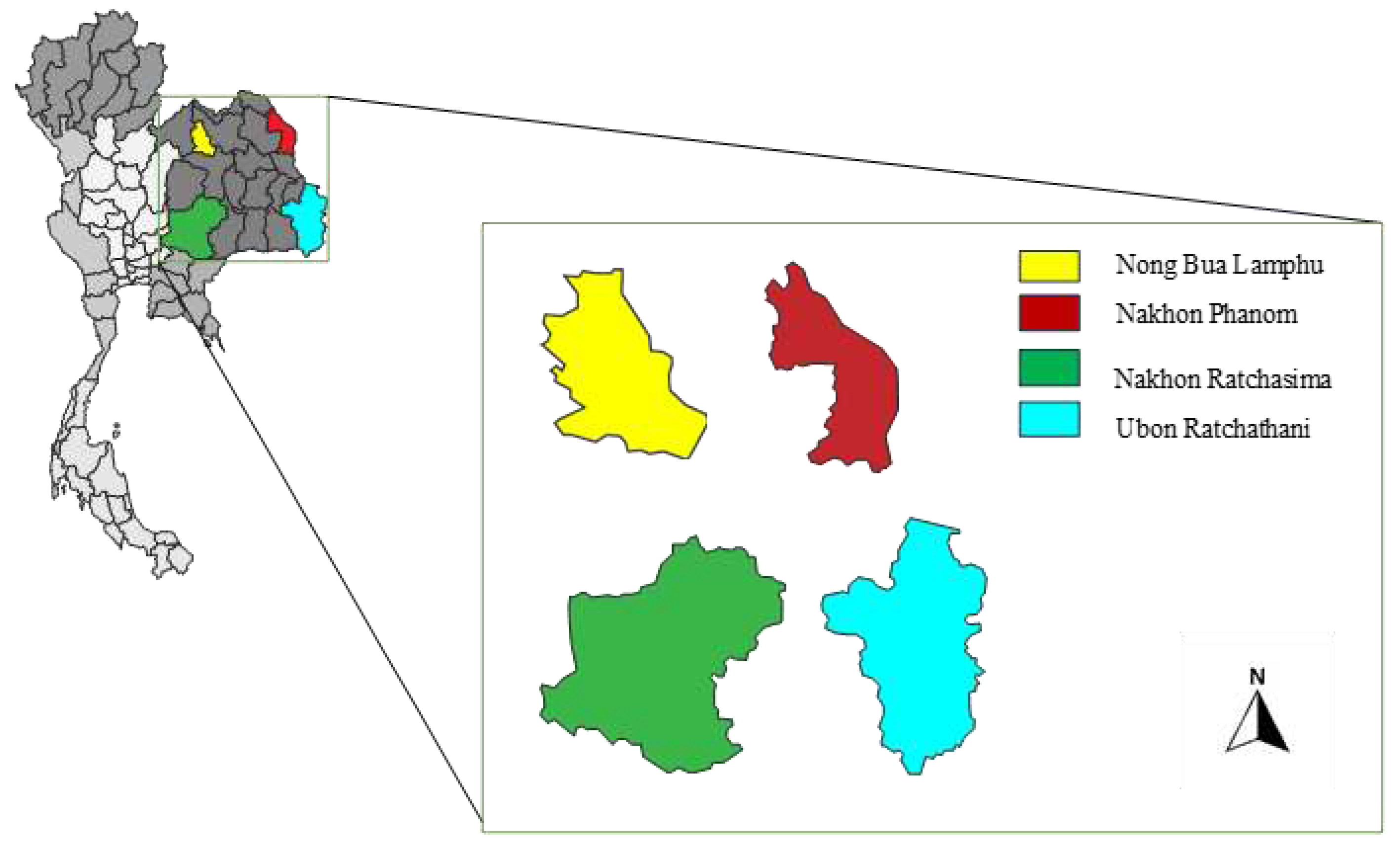

This study was conducted in four northeast provinces of Thailand: Nong Bua LamPhu, Nakhon Phanom, Ubon Ratchathani and Nakhon Ratchasima. These provinces are located both upper and lower part of the region (

Figure 1). They are commonly recognized as pilot provinces for promoting organic agriculture based of PGS as a tool for food security, self – dependence and sustainable practice as they are plentiful water supply from Mekong River, which passes Nong Bua Lamphu and Nakhon Phanom together with The Mun River, which merges with The Mekong River and passes Ubon Ratchathani and Nakhon Ratchasima. On the other hand, these provinces have faced the limitations of agroecological contexts such as poor soil, long duration of dry season and distribution of rainfall because of climate change [

20,

23,

24].

2.2. Sampling Procedure

With the limitation of organic farmers based on PGS in the northeastern Thailand, the purposive sample were employed. The empirical data were provided by each province, which resulted in a total of 135 organic farmers as informants of this study. These informants were divided into 3 case studies: case study 1 the farmers are in shifting stage from chemical agriculture to organic agriculture based on PGS; case study 2 the farmers are doing organic agriculture based on PGS and awaiting for being certified; and case study 3 the farmers are doing organic agriculture based on PGS and are certified.

2.3. Data Collection and Data Analysis

The study was carried out from 2019 – 2022. The data collection was mainly divided into three stages: Firstly, the informants were informed about the PGS concept in the social-ecological systems to transform an abstract idea into a concrete perception for better understanding.

Secondly, individual semi-structured interviews were done. Every informant was asked about his or her agricultural background and other relevant data such as socioeconomic conditions, farming practices, and agricultural histories together with these imperative criteria: (1) natural resources management, which greatly considered their use of on-farm resources and indigenous knowledge to clearly understand their farm management [

13]; (2) participating in both planning and conducting activities throughout the producing process; (3) the horizontal relationship of the group [

19]; (4) their assurance system; and (5) their network for exchanging information and knowledge.

Thirdly, the field research was supplemented by farm visits, or meeting fieldwork to confirm given information.

The interviews and the observations were recorded, and notes taken. These data were transcribed into descriptive and reflective data. This approach was suitable for converting into useful meaning unit with these three processes of qualitative data analysis: (1) data reduction; (2) data display; and (3) drawing conclusions [

25].

3. Results

3.1. Main Characteristics of the Three Case Studies

The majority of the informants was female (70%) and their age mostly was 51 years old, 50 years old and 60 years old, respectively. The size of farms (1 -5 rai per household) are 39 farmers, the size of farms (6- 10 rai per household) are 23 farmers and the sizes of farm over 10 rai per household are 17 farmers; controversially, there are 56 farmers must rent for agricultural practice. They have cultivated various kinds of horticultures, which were categorized into 6 types of organic farming:

- -

Leafy vegetables: morning glory, cabbage, white cabbage, kale, coriander, basil, spring onion, bok choy, lettuce, basil, celery, and licorice

- -

Vegetables: peppers, eggplants, brinjal, pumpkin, lentils, lemons, jujube, tomatoes, zucchini, santol and star fruit

- -

Edible or rooted vegetables: bamboo shoots, ginger, galangal, lemongrass, sweet zucchini, cassava, and yam

- -

Edible vegetables: cayenne flowers, cauliflower, butterfly pea, okra, and horseradish

- -

Herbs: aloe vera, turmeric, kaffir lime, and galingale

- -

Others: rice, deep-leaf, mango, bitter bush flower, lychees, mushrooms, and Chiang Da vegetables

The informants were grouped into these three case studies (

Table 1).

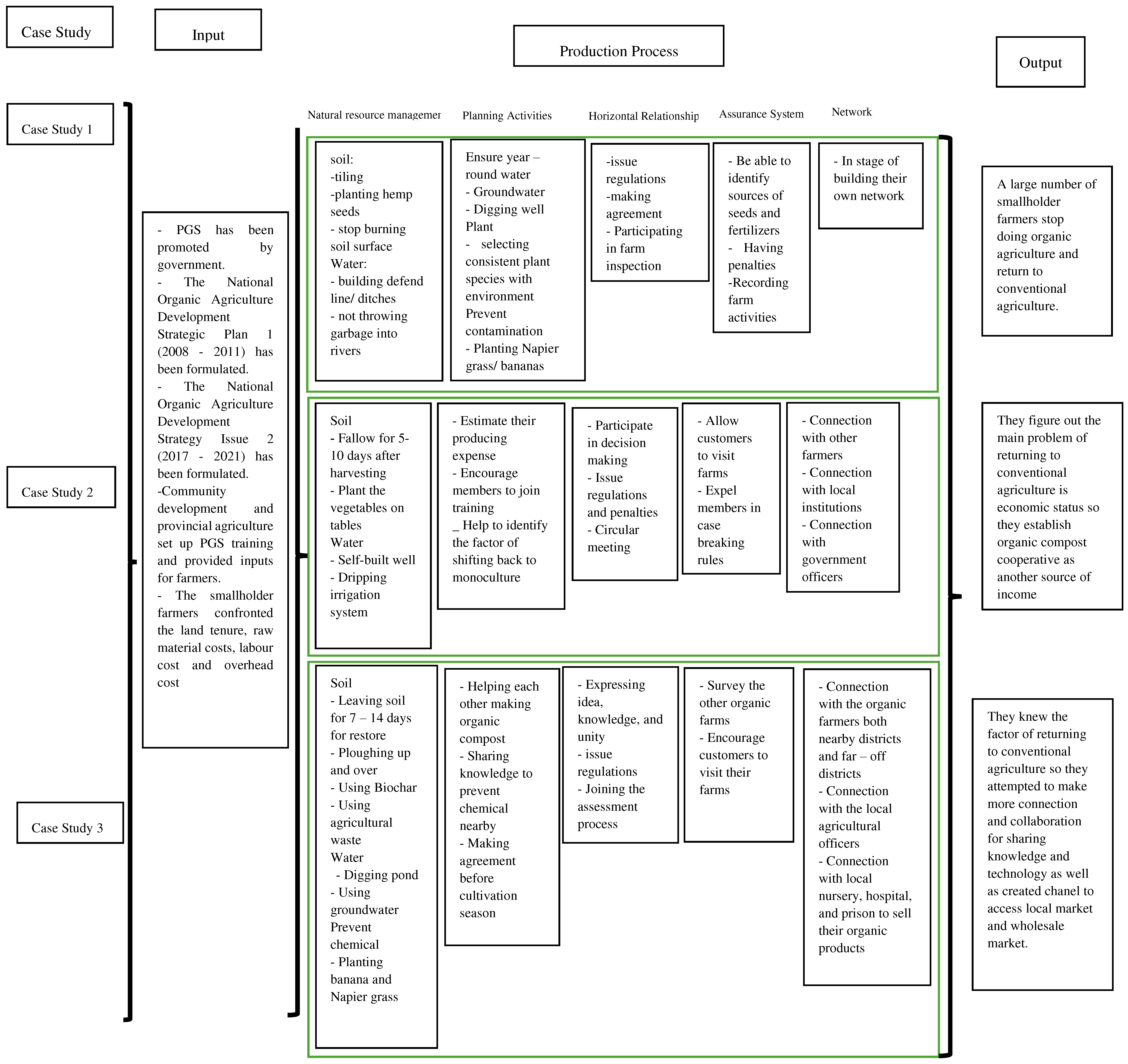

The following are the outcomes, which present the fundamentals of PGS practices that each case study considered. Besides, these five criteria were used for comparative sustainable producing processes of these three case studies (

Figure 2).

3.2. Case Study 1

The interviewees in this case study were in the stage of shifting from chemical agriculture to organic agriculture so there were diverse interviewees, who are interested in organic agriculture based on PGS practices.

3.2.1. Natural Resource Management

This property is associated with the qualities of an individual, which has been proven by their use of on-farm resources and indigenous knowledge integrating modern education. This group was in the transition period, so they were greatly concerned about their soil quality because soil is vital for organic agricultural practices. They had been doing monoculture extensively. The method for rehabilitating their soil quality was by tilling, planting hemp seeds, plowing the rice stubble and drying the soil including sowing dolomite. Moreover, the smallholder farmers seriously cooperated with their groups by not burning the soil, straw, or hay as well as not using any chemicals at all in growing plants because the interviewees perceived the fundamental of organic agriculture should be aware of chemical contamination throughout producing process. Furthermore, the water resource management within this group could be divided into 2 characteristics: the first characteristic, the 10 interviewees who are staying in the city, concerned the community environment by not throwing garbage into the river or canal including throwing garbage into trash bins; moreover, the waste should be kept sanitary because the water from the sewage flew into the river causing contamination. The second characteristic, water management in agricultural plot, the defend line or ditches were built to prevent water from outside flowing into the farm.

3.2.2. Planning and Conducting Activities throughout the Producing Process

The interviewees overall participated in both water and soil management. Regarding water management, the interviewees planned to ensure year-round water using because there was insufficient water during dry season due to climate change. The 80 interviewees used the groundwater mining and digging wells to store water while the others modified the plant species like rice to be more consistent with the environment. About planning soil rehabilitation, all the interviewees highly participated from problem identification till figuring out solutions in terms of planning and resource management, for example, when they confronted pest, they suggested to plant smelly plant. For preventing water contamination, they concerned that even neighbouring farm did organic agriculture, the dike and Napier grass or banana was built and planted to prevent any chemical.

3.2.3. Horizontal Relationship

This vital property focused on the structure of their relationship, which have both formal and informal relationships. Based on the findings, everyone had their own role and rights in their groups in terms of issue regulations and making agreement. In addition, all, head of the group, inspection, agricultural officers, and members, had to participate during farm inspection since preparing organic farm, producing, harvesting, and packaging for gaining knowledge and more understanding assessment process. For instance, the farm inspection process did not indicate whether you were right or wrong. It was in form of exchange knowledge and experience for adapting to their farm.

3.2.4. Assurance System

This property focuses on standardization to assure their production. It is essential to realize that the sources of seeds and fertilizers. They overall recognize that their sources, both seeds and organic fertilizers, were obtained from government organizations, provided during the PGS training. Besides, when they faced running out of inputs (seeds and organic fertilizers), they could buy from the shops or stores that their members agreed because this state tried to guarantee and clearly reveal the source of input. To better collaboration group standard, they had their own penalties. For instance, the farmers had to record farm activities continuously.

3.2.5. Networking

This group was in the shifting stage; therefore, their network mostly were the farmers who joined the same organic training or district agriculture, who was their consultant for organic agriculture based on PGS practices. They were in stage of building their own network not only for sharing knowledge but also for accessing organic market.

3.3. Case Study 2

The interviewees in this case study were doing organic agriculture based on PGS for more than 3 years and were waiting for being certified. As recognized, the number of farmers in this stage vastly decreased because of various factors like low productivity, socio-economic aspect, duration of soil rehabilitation.

3.3.1. Natural Resource Management

This property focuses on integrating indigenous knowledge and modern education for managing their resources. As Northeastern Thailand is known as dry region [

26], they depended on rainfall and irrigation; thus, they had planned to overcome during dry season through self-built well, nearby canals and ground water. However, they applied drip irrigation system in their farm, which reduced water usage, labour, and grass. In addition, most organic farmers used their on-farm to make organic fertilizers. While soil resource management, this case study conducted both traditional and modern means. The soil was fallow for 5 – 10 days after harvesting; in contrast, they planted the vegetables on tables to avoid pest and to reduce time for soil remineralization. This modern means could decreased plant diseases. They have established organic compost cooperative. This provided organic farmers with alternative income opportunity.

3.3.2. Planning and Conducting Activities throughout the Producing Process

This vital property focuses on participating in planning and conducting the farm activities. Regarding agricultural inputs, most organic farmers estimated their expenses before cultivating because if they joined the government or local institution training, they would receive both organic seeds, compost, hays, or bio extract. Thus, they highly encouraged their members to join while they could buy the inputs from stores or shops, which were accepted by the members. Furthermore, the number of organic farmers is crucial for the producing volume and bargaining. They helped each other to identify the key factor that made other farmers returning to chemical agriculture. For instance, there were 40 members at the beginning and the members were gradually reducing because organic agriculture practices needed to be persistence and took time to get returns.

3.3.3. Horizontal Relationship

This horizontal relationship focuses on parallel relationship, which mainly aimed at participating in decision-making, adaptation of regulation in the local context together with farm assessment. Based on the findings, the distance was the constraint of monthly meeting, so they took the form of socializing and circular meeting; consequently, everyone did not feel exclude. Moreover, the regulations and penalties were issued by every farmer; thus, everyone had to follow this agreement.

3.3.4. Assurance System

The monitoring played the essential role for building trust and transparency systems to ensure the standard. The severe penalty was to expel from the group. However, before being expelled, they compromised and warmed, both formal and informal ways. No one was expelled from the group, but they left the group for continuing chemical agriculture. Moreover, this case study allowed the customers to visit their organic farm to show their producing process.

3.3.5. Networking

This pivot property of networking focuses on connection with local farmer organic groups, institutions, and organizations. Based on finding, there were 3 connections in this case study; first was the local organic farmer connection. They have been known since they started organic agriculture based on PGS. They have still communicated for sharing problem, idea, and solution. Second, the local institution set the training and launched a project, enhancing organic products, which taught the organic farmers using their indigenous knowledge with the technology to prevent pest, developing organic compost and organic seeds. Lastly, the government organizations, who are the main organization to promote and support the farmer, provided organic inputs, training the farmer how to do organic agriculture, acting as consultant for helping the organic farmers from producing to accessing to the organic markets.

3.4. Case Study 3

3.4.1. Natural Resource Management

The organic farmers in this case study totally understand the organic agriculture based on PGS criteria because they were certified. Related to focus on soil management, they concerned farm management and environmentally friendly manners. For instance, they left their soil for 7 – 14 days for restore and plough up and over. Moreover, 5 farmers from this case study used “Biochar”, is a kind of organic matter that add into soil for improving soil quality and mitigate climate change with soil carbon [

27]. They were recommended by the agricultural officers. This mean can reduce producing cost. However, they have never forgotten using agricultural waste. They greatly concerned insufficient water resources because of climate change and water contamination. Based on findings, they had a meeting before cultivation to discuss about water scarcity and to solve this problem or to mitigate its severity. For instance, they dig the pond, used ground water or irrigation. Moreover, they planted banana and Napier grass on the dike for preventing chemical from nearby farm; however, they could not sell the banana or bamboo shoot as organic products.

3.4.2. Planning and Conducting Activities throughout the Producing Process

They entirely participated from selecting seeds, sources of seeds besides received from government, and making organic compost. Based on findings, they were encouraged by their groups to help each other making organic compost and sharing it; moreover, consulting how to prevent the chemical from nearby farm. They made an agreement before the cultivation season. Nevertheless, the interviewees in this case study seriously confronted shifting back to chemical agriculture problem because it effected on the producing volume if they wanted to sell at wholesale like Lotus or Makro. They figured out the main problem of shifting back that was economic condition.

3.4.3. Horizontal Relationship

The vital property focuses on the equality of membership; thus, everyone can express their idea, knowledge, and unity. Like the other 2 case studies, every interviewee shared the idea for issue rules and regulations together with join the assessment process to learn and exchange idea.

3.4.4. Assurance System

They had 2 ways to guarantee: first, they surveiled the other organic farmers to follow the rules and regulations if they broke the rules, they would be cautioned for 2 times. However, there was no one be expelled from the organic groups. Second, they encourage the customers to visit their farms to build trust and provide education.

3.4.5. Networking

Networking is essential for organic agricultural practices. In this case, there were three important connections that was firstly, the local agricultural officers were very important. They acted as facilitators to help this group from starting organic agriculture based on PGS, guiding how to be certified and accessing to organic market. Then, the organic farmers both nearby district and far-off districts. They greatly shared technology and market while their organic products were insufficient, they asked for their connections. Lastly, government organizations such as nursery, hospital, or prison, bought their organic products.

4. Discussion

The land tenure was greatly problematic for smallholder farmers in Thailand according to the study [

28], there were 4,070,228 household farmers in Thailand and there were 1,724,091 (42.36%) households do not have land tenure, which implied that they greatly faced the economic crisis such as raw material costs, labour cost and overhead cost [

29]. Moreover, the smallholder farmers had less power for negotiations; therefore, they realized that collaboration was the important for them to motivate the local government or institutions to support [

19] because they could not only depend on the government due to limitation of budget, time, and resources; thus, the organic farmers helped each other that implied their potential and their horizontal relationships. Moreover, if the farmers have the similar purpose or objective and continuously have the activities.

The organic agriculture based on PGS was one of the alternative agricultures which has the holistic management: concerning the natural resources and environment, on- farm management together with the producing with the combination of indigenous knowledge and technology. It promoted the farmers to plant various kind of plants in farm. Moreover, the farmers are capable to express their thoughts and issue regulations in line with their local context through participatory approach [

30]; thus, this practice creates the democratic participation.

Even the organic farming based on PGS is the solution for sustainable environment and safeguard ecosystems, it takes lengthy period to recover soil fertility which means the yields and incomes of farmers dramatically decline [

1] because the soil is vital for organic production; hence, the volume of product depends on the quality and quantity of soil. Consequently, this factor directly impacts on the shifting stage. In fact, the smallholder farmers yield gradually decrease around 40% [

31,

32,

33] due to the soil nutrition decreases, which significantly impacts their income. Thus, the government should have the measures to aid the smallholder farmers during this shifting stage such as financial measure or subsidies money, low interest loan for farmers because even the smallholder farmers used the leftover production or on-farm management, the production cost could not reduce much. [

34,

35]. This mean could mitigate the shifting back to chemical agricultural practice and chemical contamination in soil, water, and air.

In addition, the collaboration between the smallholder farmers and local institution or between the smallholder and agricultural officers in terms of enhancing organic compost or fertilizers and establishing organic fertilizer cooperative with in line the community and spatial context to create another source of income [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Furthermore, the smallholder farmers, who participated in organic fertilizer cooperative, effected on their farmers’ behaviour and interests [

41].

The unique model of PGS provided smallholders the power to carry out activities such as planning, decision making, establishing standard, stipulating penalties, and visiting procedures, gave a chance to farmers to encourage the active participation with variety of stakeholders like producers, consumers, officers and educational institutions. Moreover, the purpose of participation in the assessment was an expression of farmer equality and empowerment in line with the study of [

42], pointing out that farmer participation was empowering. Furthermore, the farm visit was to let the members consult the basic data about farm operation because this was the verification education method and problem identifications. Studies by [

13,

18], reinforced this, the participation in group activities was the fundamental of PGS practice.

To secure the producers were the challenge of doing this practice because of personal differences and problems. Thus, both farmers and government agencies should work together to find solutions and preventing method. This investigation, in agreement with authors, such as [

43,

44], showed that the government agencies have foreseen the impact that the farmers are affected by decreasing yields and incomes, so these caused chance of returning. However, little research has been done on preventing farmers from returning to chemical agriculture again.

5. Conclusions

The organic agriculture based on PGS acted as a tool to mitigate poverty, to restore ecosystems and to collaborate with various stakeholders. The large number of smallholder farmers at first preferred to do organic farming as in case study 1 but they gave up doing organic practice at the end due to the decreasing of yield even though they built their own connection. In case study 2, they tried to figure out this problem so they attempted to establish the compost cooperation as another source of income and applied technology in water management to ensure that they could have water usage all year. In case study 3, they applied biochar technique in soil management to fruitful it as well as they seek more connection not only within district but also far off district to ease leaving groups. However, every related sector should aid because during the transition period was challenging for farmers to give up doing organic agriculture. Thus, financial assistance to smallholder farmers is essential.

Author Contributions

The corresponding author mainly contributed this manuscript and B.T was advisor.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Mahidol University and approved by the Office of The Committee for Research Ethics (Social Sciences) (MUSSIRB2019/280 B1)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request. The data are not publicly available for privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lee, S. (2021). In the era of climate change: moving beyond conventional agriculture in Thailand. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Development, 18(1), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Laohaudomchok, W., Nankongnab, N., Siriruttanapruk, S., Klaimala, P., Lianchamroon, W., Ousap, P., ... & Woskie, S. (2020). Pesticide use in Thailand: Current situation, health risks, and gaps in research and policy. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal, 27(5), 1147-1169.

- International Trade Administration U.S Department of Commerce (2024). Agriculture. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/thailand-agriculture (Accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Attavanich, W., Chantarat, S., Chenphuengpawn, J., Mahasuweerachai, P., & Thampanishvong, K. (2019). Farms, farmers and farming: a perspective through data and behavioral insights (No. 122). Puey Ungphakorn Institute for Economic Research.

- Ahmad, A., & Isvilanonda, S. (2005). Rural poverty and agricultural diversification in Thailand. Rice is life: scientific perspectives for the 21st century. International Research Institute, Los Banos, 425-428.

- Tirado, R., Englande, A. J., Promakasikorn, L., & Novotny, V. (2008). Use of agrochemicals in Thailand and its consequences for the environment. Devon: Greenpeace Research Laboratories.

- Prommawin, B., Svavasu, N., Tanpraphan, S., Saengavut, V., Jithitikulchai, T., Attavanich, W., & McCarl, B. A. (2022). Impacts of Climate Change and Agricultural Diversification on Agricultural Production Value of Thai Farm Households (No. 184). Puey Ungphakorn Institute for Economic Research.

- Rieber, L. (2013). Making the Rice Bowl Bigger: Agricultural Output and Rural Poverty in Thailand. Global Majority E-Journal, 4(1).

- Tippawan, K. (2014). Alternative Agriculture Development in the opinion of People in Sator Subdistrict Administrative organization, Khaosaming District, Trat Province (Master’s Thesis). Rambhai Barni Rajabhat University.

- Seeniang, P. (2013). Problem of Chemical Agriculture. In Extension of Sustainable Agriculture (p.3-11). Kasetsart University.

- Suma, Y., Eaktasang, N., Pasukphun, N., & Tingsa, T. (2022). Health risks associated with pesticide exposure and pesticides handling practices among farmers in Thailand. Journal of Current Science and Technology, 12(1), 128-140.

- Yossuk, P., & Kawichai, P. (2017). Problems and appropriate approaches to implementing organic agriculture policy in Thailand. Journal of Community Development and Life Quality, 5(1), 129-141.

- Athinuwat, D., Indramangala, J., Visantapong, S., Pornsirichaivatana, P., and Mettpranee, L. (2016). What is Participatory Guarantee System of Organic Standard? Thai Journal of Science and Technology. 5(2), 119-134.

- Kirchmann, H. (2019). Why organic farming is not the way forward. Outlook on Agriculture, 48(1), 22-27. [CrossRef]

- De Ponti, T., Rijk, B., & Van Ittersum, M. K. (2012). The crop yield gap between organic and conventional agricul-ture. Agricultural systems, 108, 1-9.

- 16. Iles, A., & Marsh, R. (2012). Nurturing diversified farming systems in industrialized countries: how public policy can contribute. Ecology and society, 17(4). [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, S., & Vogl, C. R. (2018). Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) in Mexico: a theoretic ideal or everyday practice?. Agriculture and human values, 35, 457-472. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E., Tovar, L. G., Gueguen, E., Humphries, S., Landman, K., & Rindermann, R. S. (2016). Participatory guarantee systems and the re-imagining of Mexico’s organic sector. Agriculture and Human Values, 33, 373-388. [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge university press.

- Choenkwan, S., Fox, J. M., & Rambo, A. T. (2014). Agriculture in the mountains of northeastern Thailand: current situation and prospects for development. Mountain Research and Development, 34(2), 95-106. [CrossRef]

- 21. Northeastern Development Plan. (2018). Northeastern Development Plan during The National Economic and Social Development Plan (2017 - 2021). Accessed on September 10, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.nesdc.go.th/ewt_dl_link.php?nid=7526.

- Panpakdee, C. (2023). The social-ecological resilience indicators of organic rice production in Northeastern Thailand. Organic Agriculture, 13(3), 483-501. [CrossRef]

- Lertna S (2014) Strengthening Farmers’ Adaptation to Climate Change in Rainfed Lowland Rice System in Northeastern. Thailand Agricultural Research Repository.

- Anuluxtipun, Y. (2017). Climate change effect on rice and maize production in Lower Mekong Basin. Journal of Geoinformation Technology of Burapha University, 2(3). [CrossRef].

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. sage.

- Kuntiyawichai K, Wongsasri S. Assessment of Drought Severity and Vulnerability in the Lam Phaniang River Basin, Thailand. Water. 2021; 13(19):2743. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Linna, C., Ma, S., Ma, Q., Song, W., Shen, M., ... & Wang, L. (2022). Biochar combined with organic and inorganic fertilizers promoted the rapeseed nutrient uptake and improved the purple soil quality. Frontiers in Nutrition, 9, 997151. [CrossRef]

- Greeta, A., Sombat, P., Jarin, T. & Somsak, P. (2016). ANALYSIS OF THE DISTRIBUTION OF LAND IN THE AGRICULTURAL SECTOR OF THAILAND. Journal of Srinakharinwirot Research and Development (Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences), 8(15), 1-18.

- Nanichakorn, K. (2021). Return Cost of Rice Cultivation of Farmers in Non Thai Distrsict, Nakhon Ratchasima Province. Pathumthani University Academic Journal, 13(1), 185-192.

- Nikolaidou, S., Kouzeleas, S., Goulas, A., & Goussios, D. (2019). Participatory Guarantee Systems for small farms and local markets: involving consumers in the guarantee process.

- Jouzi, Z., Azadi, H., Taheri, F., Zarafshani, K., Gebrehiwot, K., Van Passel, S., & Lebailly, P. (2017). Organic farming and small-scale farmers: Main opportunities and challenges. Ecological economics, 132, 144-154. [CrossRef]

- Crowder, D. W., & Reganold, J. P. (2015). Financial competitiveness of organic agriculture on a global scale. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(24), 7611-7616. [CrossRef]

- Seufert, V., Ramankutty, N., & Foley, J. A. (2012). Comparing the yields of organic and conventional agriculture. Nature, 485(7397), 229-232. [CrossRef]

- 34. Alastair Iles and Robin Marsh. (2012). Nurturing Diversified Farming Systems in Industrialized Countries How Public Policy Can Contribute. Ecology and Society. 17(4). [CrossRef]

- Annop R., Sarawan R., Voranat S. and Pawina S. (2014). Development of the Strengths of the Natural-Agricultural Network of Wat Yannasangwararam Community Amphur Banglamung, Cholburi Province. SDU Res. J. 10(2), 73-90.

- Yingluk K. and Aslam, U. (2017). Enhancing Sustainable Agriculture of Small-scale Farmers Cha Hom District Lamphan Province. Thailand Research Fund.

- Earth Net Foundation. (2001). What Is Organic Agriculture? Kasetkam Journal. 12 (9): 44 – 46.

- Precha P., Nuchanard C., Chalern S., Nattapran K. and Kanoknard R. (2009). Problems and Constraits of Planting Organic Fruits Case Studies Rayong, Chanthaburi and Trat Provinces. Romphruek Journal. 27(2), 136-185.

- Ratee L. (2010). The Comparison of Costs and Returns between Organic Rice Farming and Chemical Rice Farming in Amphoe Sawang Arom, Uthaithani Province. Master Thesis. Faculty of Economics. Kasetsart University.

- Chalisa S. and Kanoknate P. (2016). The Comparison of Costs and Returns between Organic Rice Farming and Chemical Rice Farming. Veridian E-journal, 9(2), 519-526.

- Li, J., He, R., deVoil, P., & Wan, S. (2021). Enhancing the application of organic fertilisers by members of agricultural cooperatives. Journal of Environmental Management, 293, 112901. [CrossRef]

- Home, R., Bouagnimbeck, H., Ugas, R., Arbenz, M., & Stolze, M. (2017). Participatory guarantee systems: Organic certification to empower farmers and strengthen communities. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 41(5), 526-545. [CrossRef]

- Stolze, M., & Lampkin, N. (2009). Policy for organic farming: Rationale and concepts. Food policy, 34(3), 237-244. [CrossRef]

- Michelsen, J. (2002). Organic farming development in Europe—impacts of regulation and institutional diversity. In Economics of Pesticides, Sustainable Food Production, and Organic Food Markets (pp. 101-138). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).