Submitted:

06 February 2024

Posted:

06 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

History

2. Toxicity

2.1. Neuroinflammation

2.2. Neurotransmitters

3. Abuse potential

3.1. Self-administration and self-stimulation

3.2. Drug discrimination learning

3.3. Conditioned place preference

4. Current public health perspective

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

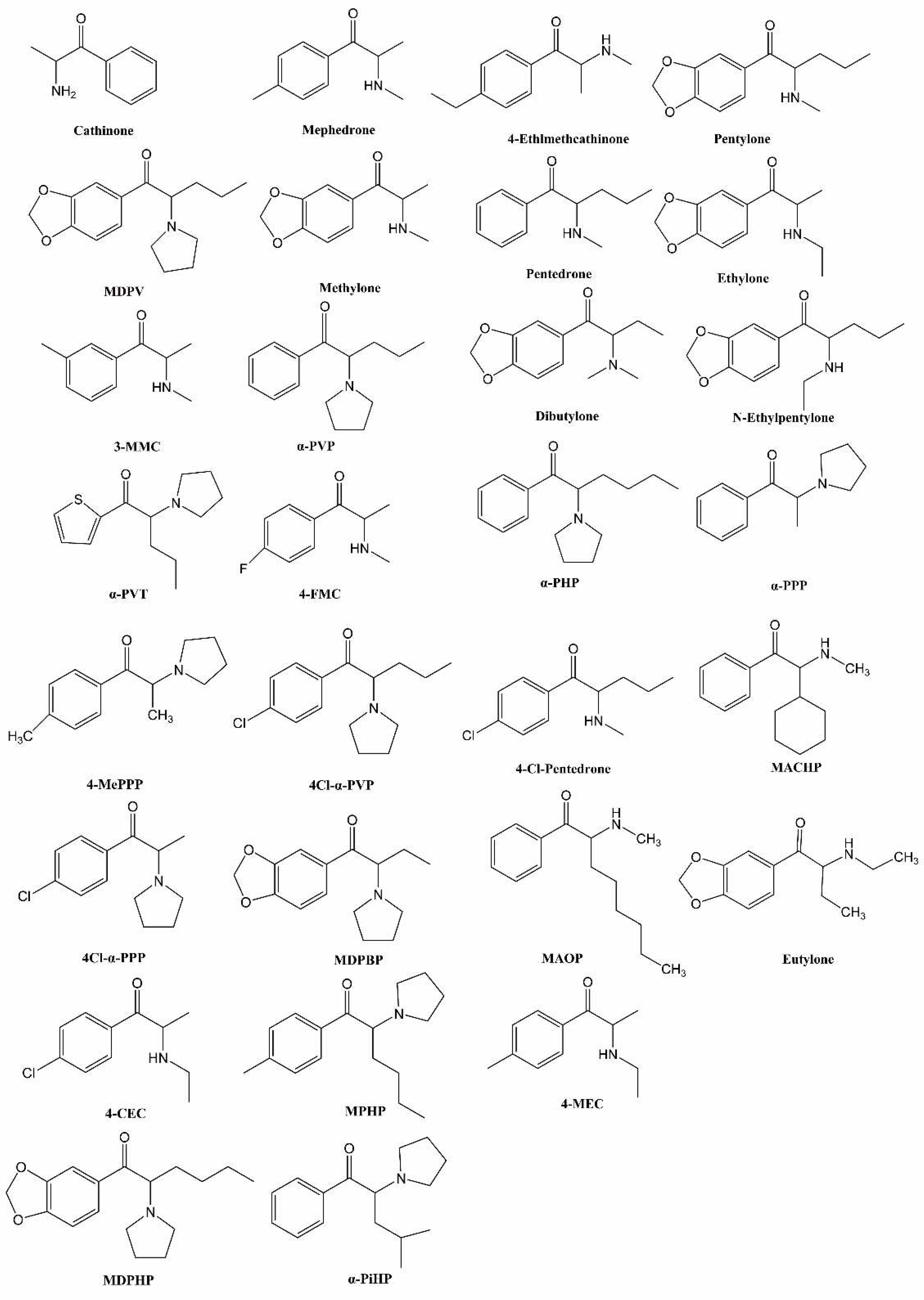

| SCs | synthetic cathinones |

| mephedrone | 4-methylmethcathinone |

| MDPV | 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone |

| methylone | 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylcathinone |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| METH | methamphetamine |

| MDMA | 3,4-methylenedioxymethapmphetamine |

| 3-MMC | 3-methylmethcathinone |

| NA | noradrenaline |

| DA | dopamine |

| 5-HT | serotonin |

| NET | noradrenaline transporter |

| DAT | dopamine transporter |

| SERT | serotonin transporter |

| VMAT2 | vesicular monoamine transporter 2 |

| α-PVP | α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone |

| IL-1α | interleukin-1 alpha |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| α-PVT | alpha-pyrrolidinopentiothiophenone |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| GFAP | glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| 4-FMC | 4-fluoromethcathinone |

| IVSA | intravenous self-administration |

| ICSS | intracranial self-stimulation |

| BSR | brain stimulation reward |

| α-PHP | α-pyrrolidinohexiophenone |

| α-PPP | α-pyrrolidinopropiophenone |

| 4-MePPP | 4-methyl-alpha-pyrrolidinopropiophenone |

| 4cl-α-PVP | 4-chloro-α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone |

| 4cl-α-PPP | 4-chloro-α-pyrrolidinopropiophenone |

| MDPBP | 3,4-Methylenedioxy-alpha-pyrrolidinobutyrophenone |

| 4-CEC | 4-chloroethcathinone |

| MPHP | 4-methyl-α-phrrolidinohexiophenone |

| MDPHP | 3,4-methylenedioxy-alpha-pyrrolidinohexanophenone |

| α-PiHP | alpha-pyrrolidinoisohexiophenone |

| 4-Cl-pentedrone | 4-chloro-pentedrone |

| CPP | conditioned place preference |

| MACHP | 2-cyclohexyl-2-(methylamino)-1-phenylethanone |

| MAOP | 2-(methylamino)-1-phenyloctan-1-one |

| MSM | men who have sex with men |

| GHB | gamma-hydroxybutyrate |

| GBL | gamma-butyrolactone |

| SDU | sexualized drug use |

| 4-MEC | 4-methylethcathinone |

References

- Patel, N.B. Mechanism of action of cathinone: the active ingredient of khat (Catha edulis). East Afr Med J 2000, 77, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillet-Loilier, M.; Cesbron, A.; Le Boisselier, R.; et al. Emerging drugs of abuse: current perspectives on substituted cathinones. Subst Abuse Rehabil 2014, 5, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Valente, M.J.; Guedes de Pinho, P.; de Lourdes Bastos, M.; et al. Khat and synthetic cathinones: a review. Arch Toxicol 2014, 88, 15–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.P. Cathinone derivatives: a review of their chemistry, pharmacology and toxicology. Drug Test Anal 2011, 3, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, J.F.B.E.; Adams, R. Synthetic homologues of d,l-ephedrine. J Am Chem Soc 1928, 50, 2287–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, G.L. Diethylpropion in the treatment of obesity. J Coll Gen Pract 1963, 6, 347–349. [Google Scholar]

- Gardos, G.; Cole, J.O. Evaluation of pyrovalerone in chronically fatigued volunteers. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 1971, 13, 631–635. [Google Scholar]

- Soroko, F.E.; Mehta, N.B.; Maxwell, R.A.; et al. Bupropion hydrochloride ((+/-) alpha-t-butylamino-3-chloropropiophenone HCl): a novel antidepressant agent. J Pharm Pharmacol 1977, 29, 767–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossong, M.G.; Van Dijk, J.P.; Niesink, R.J. Methylone and mCPP, two new drugs of abuse? . Addict Biol 2005, 10, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karila, L.; Billieux, J.; Benyamina, A.; et al. The effects and risks associated to mephedrone and methylone in humans: A review of the preliminary evidences. Brain Res Bull 2016, 126 Pt 1, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafioun, L.; Bonadio, F.A.; Baik, K.D.; et al. Patterns of Use, Acute Subjective Experiences, and Motivations for Using Synthetic Cathinones ("Bath Salts") in Recreational Users. J Psychoactive Drugs 2016, 48, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, A.J.; Vorce, S.P.; Levine, B.; et al. Multiple-drug toxicity caused by the coadministration of 4-methylmethcathinone (mephedrone) and heroin. J Anal Toxicol 2010, 34, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.M.; Davies, S.; Puchnarewicz, M.; et al. Recreational use of mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone, 4-MMC) with associated sympathomimetic toxicity. J Med Toxicol 2010, 6, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.M.; Greene, S.L.; Dargan, P.I. Clinical pattern of toxicity associated with the novel synthetic cathinone mephedrone. Emerg Med J 2011, 28, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council CotEU. Council Decision of 2 December 2010 on submitting 4-methylmethcathinone (mephedrone) to control measures. Offcial Journal of the European Union 2010, 44–45.

- Morris, K. UK places generic ban on mephedrone drug family. Lancet 2010, 375, 1333–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMCDDA-Europol. EMCDDA-Europol 2009 annual report on the implementation of Council Decision 2005/387/JHA. 2009.

- EMCDDA-Europol. EMCDDA-Europol 2010 annual report on the implementation of Council Decision 2005/387/JHA. 2010.

- EMCDDA-Europol. EMCDDA-Europol (2011) EMCDDA-Europol 2011 annual report on the implementation of Council Decision 2005/387/JHA. 2011.

- EMCDDA-Europol. EMCDDA-Europol (2012) EMCDDA-Europol 2012 annual report on the implementation of Council Decision 2005/387/JHA. 2012.

- EMCDDA-Europol. EMCDDA-Europol (2013) EMCDDA-Europol 2013 annual report on the implementation of Council Decision 2005/387/JHA. 2013.

- EMCDDA-Europol. EMCDDA-Europol 2014 annual report on the implementation of Council Decision 2005/387/JHA. 2014.

- EMCDDA-Europol. EMCDDA-Europol 2015 annual report on the implementation of Council Decision 2005/387/JHA. 2015.

- Bonson, K.R.; Dalton, T.; Chiapperino, D. Scheduling synthetic cathinone substances under the Controlled Substances Act. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2019, 236, 845–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Injection of synthetic cathinones (Perspectives on drugs)[N]. Available online: https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/pods/synthetic-cathinones-injection_en.

- Goncalves, J.L.; Alves, V.L.; Aguiar, J.; et al. Synthetic cathinones: an evolving class of new psychoactive substances. Crit Rev Toxicol 2019, 49, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, J.M.; Nelson, L.S. The toxicology of bath salts: a review of synthetic cathinones. J Med Toxicol 2012, 8, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, S.F.; Patel, H.; Mahmoud, M.; et al. Bath salts intoxication: a case series. J Emerg Med 2013, 45, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamal, M.A.; Garcia, I.E.; Pinto, B.I.; et al. Extracellular Cysteine in Connexins: Role as Redox Sensors. Front Physiol 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borek, H.A.; Holstege, C.P. Hyperthermia and multiorgan failure after abuse of "bath salts" containing 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone. Ann Emerg Med 2012, 60, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, L.; Grison-Hernando, H.; Boels, D.; et al. Death following ingestion of methylone. Int J Legal Med 2016, 130, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowicz, P.; Zuba, D.; Byrska, B. Fatal intoxication with 3-methyl-N-methylcathinone (3-MMC) and 5-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran (5-APB). Forensic Sci Int 2014, 245, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirakul, P.; L, S.H.; K, L.B.; et al. Clinical Presentation, Autopsy Results and Toxicology Findings in an Acute N-Ethylpentylone Fatality. J Anal Toxicol 2017, 41, 342–346. [Google Scholar]

- Benzer, T.I.; Nejad, S.H.; Flood, J.G. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 40-2013. A 36-year-old man with agitation and paranoia. N Engl J Med 2013, 369, 2536–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice, L.J.; Glennon, R.A.; Negus, S.S. Synthetic cathinones: chemical phylogeny, physiology, and neuropharmacology. Life Sci 2014, 97, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehr, J.; Ichinose, F.; Yoshitake, S.; et al. Mephedrone, compared with MDMA (ecstasy) and amphetamine, rapidly increases both dopamine and 5-HT levels in nucleus accumbens of awake rats. Br J Pharmacol 2011, 164, 1949–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M.H.; Ayestas, M.A.; Jr Partilla, J.S.; et al. The designer methcathinone analogs, mephedrone and methylone, are substrates for monoamine transporters in brain tissue. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 1192–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liechti, M. Novel psychoactive substances (designer drugs): overview and pharmacology of modulators of monoamine signaling. Swiss Med Wkly 2015, 145, w14043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, B.K.; Moszczynska, A.; Gudelsky, G.A. Amphetamine toxicities: classical and emerging mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010, 1187, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.M.; Walker, P.D.; Benjamins, J.A.; et al. Methamphetamine neurotoxicity in dopamine nerve endings of the striatum is associated with microglial activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2004, 311, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moratalla, R.; Khairnar, A.; Simola, N.; et al. Amphetamine-related drugs neurotoxicity in humans and in experimental animals: Main mechanisms. Prog Neurobiol 2017, 155, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angoa-Perez, M.; Kane, M.J.; Briggs, D.I.; et al. Mephedrone does not damage dopamine nerve endings of the striatum, but enhances the neurotoxicity of methamphetamine, amphetamine, and MDMA. J Neurochem 2013, 125, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Arnau, R.; Martinez-Clemente, J.; Rodrigo, T.; et al. Neuronal changes and oxidative stress in adolescent rats after repeated exposure to mephedrone. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2015, 286, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angoa-Perez, M.; Kane, M.J.; Francescutti, D.M.; et al. Mephedrone, an abused psychoactive component of 'bath salts' and methamphetamine congener, does not cause neurotoxicity to dopamine nerve endings of the striatum. J Neurochem 2012, 120, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Clemente, J.; Lopez-Arnau, R.; Abad, S.; et al. Dose and time-dependent selective neurotoxicity induced by mephedrone in mice. PLoS One 2014, 9, e99002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszalek-Grabska, M.; Zakrocka, I.; Budzynska, B.; et al. Binge-like mephedrone treatment induces memory impairment concomitant with brain kynurenic acid reduction in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2022, 454, 116216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grochecki, P.; Smaga, I.; Lopatynska-Mazurek, M.; et al. Effects of Mephedrone and Amphetamine Exposure during Adolescence on Spatial Memory in Adulthood: Behavioral and Neurochemical Analysis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, P.; Jankowski, K.; Budzynska, B.; et al. Potential pro-oxidative effects of single dose of mephedrone in vital organs of mice. Pharmacol Rep 2018, 70, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marusich, J.A.; Gay, E.A.; Stewart, D.A.; et al. Sex differences in inflammatory cytokine levels following synthetic cathinone self-administration in rats. Neurotoxicology 2022, 88, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noruzi, M.; Behmadi, H.; Halvaei Khankahdani, Z.; et al. Alpha pyrrolidinovalerophenone (alpha-PVP) administration impairs spatial learning and memory in rats through brain mitochondrial dysfunction. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2023, 467, 116497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, O.H.; Jeon, K.O.; Jang, E.Y. Alpha-pyrrolidinopentiothiophenone (alpha-PVT) activates the TLR-NF-kappaB-MAPK signaling pathway and proinflammatory cytokine production and induces behavioral sensitization in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2022, 221, 173484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.J.; Bastos, M.L.; Fernandes, E.; et al. Neurotoxicity of beta-Keto Amphetamines: Deathly Mechanisms Elicited by Methylone and MDPV in Human Dopaminergic SH-SY5Y Cells. ACS Chem Neurosci 2017, 8, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campeao, M.; Fernandes, L.; Pita, I.R.; et al. Acute MDPV Binge Paradigm on Mice Emotional Behavior and Glial Signature. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, E.K.; Leyrer-Jackson, J.M.; Hood, L.E.; et al. Effects of repeated binge intake of the pyrovalerone cathinone derivative 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone on prefrontal cytokine levels in rats - a preliminary study. Front Behav Neurosci 2023, 17, 1275968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anneken JH, Angoa-Perez M, Kuhn DM. 3,4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone prevents while methylone enhances methamphetamine-induced damage to dopamine nerve endings: beta-ketoamphetamine modulation of neurotoxicity by the dopamine transporter. J Neurochem 2015, 133, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadet, J.L.; Krasnova, I.N.; Jayanthi, S.; et al. Neurotoxicity of substituted amphetamines: molecular and cellular mechanisms. Neurotox Res 2007, 11, 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kita, T.; Wagner, G.C.; Nakashima, T. Current research on methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity: animal models of monoamine disruption. J Pharmacol Sci 2003, 92, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann MH, Wang X, Rothman RB. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) neurotoxicity in rats: a reappraisal of past and present findings. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007, 189, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpin, L.E.; Collins, S.A.; Yamamoto, B.K. Neurotoxicity of methamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine. Life Sci 2014, 97, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmler, L.D.; Buser, T.A.; Donzelli, M.; et al. Pharmacological characterization of designer cathinones in vitro. Br J Pharmacol 2013, 168, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gygi, M.P.; Gibb, J.W.; Hanson, G.R. Methcathinone: an initial study of its effects on monoaminergic systems. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1996, 276, 1066–1072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCann, U.D.; Wong, D.F.; Yokoi, F.; et al. Reduced striatal dopamine transporter density in abstinent methamphetamine and methcathinone users: evidence from positron emission tomography studies with [11C]WIN-35,428. J Neurosci 1998, 18, 8417–8422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciudad-Roberts, A.; Camarasa, J.; Ciudad, C.J.; et al. Alcohol enhances the psychostimulant and conditioning effects of mephedrone in adolescent mice; postulation of unique roles of D3 receptors and BDNF in place preference acquisition. Br J Pharmacol 2015, 172, 4970–4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rickli, A.; Hoener, M.C.; Liechti, M.E. Monoamine transporter and receptor interaction profiles of novel psychoactive substances: para-halogenated amphetamines and pyrovalerone cathinones. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2015, 25, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal-Gratacos, N.; Rios-Rodriguez, E.; Pubill, D.; et al. Structure-Activity Relationship of N-Ethyl-Hexedrone Analogues: Role of the alpha-Carbon Side-Chain Length in the Mechanism of Action, Cytotoxicity, and Behavioral Effects in Mice. ACS Chem Neurosci 2023, 14, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriola, M. Synthetic cathinone abuse. Clin Pharmacol 2013, 5, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hursh, S.R.; Silberberg, A. Economic demand and essential value. Psychol Rev 2008, 115, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huskinson, S.L.; Naylor, J.E.; Townsend, E.A.; et al. Self-administration and behavioral economics of second-generation synthetic cathinones in male rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2017, 234, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Lai, M.; Fu, D.; et al. Reinforcing and discriminative-stimulus effects of two pyrrolidine-containing synthetic cathinone derivatives in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2021, 203, 173128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.; Chen, W.; Zhu, H.; et al. Low dose risperidone attenuates cue-induced but not heroin-induced reinstatement of heroin seeking in an animal model of relapse. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2013, 16, 1569–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negus, S.S.; Miller, L.L. Intracranial self-stimulation to evaluate abuse potential of drugs. Pharmacol Rev 2014, 66, 869–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadlock, G.C.; Webb, K.M.; McFadden, L.M.; et al. 4-Methylmethcathinone (mephedrone): neuropharmacological effects of a designer stimulant of abuse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2011, 339, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarde, S.M.; Angrish, D.; Barlow, D.J.; et al. Mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone) supports intravenous self-administration in Sprague-Dawley and Wistar rats. Addict Biol 2013, 18, 786–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, J.D.; Grant, Y.; Creehan, K.M.; et al. Escalation of intravenous self-administration of methylone and mephedrone under extended access conditions. Addict Biol 2017, 22, 1160–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creehan, K.M.; Vandewater, S.A.; Taffe, M.A. Intravenous self-administration of mephedrone, methylone and MDMA in female rats. Neuropharmacology 2015, 92, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J.E.; Agoglia, A.E.; Fish, E.W.; et al. Mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone) and intracranial self-stimulation in C57BL/6J mice: comparison to cocaine. Behav Brain Res 2012, 234, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregg, R.A.; Baumann, M.H.; Partilla, J.S.; et al. Stereochemistry of mephedrone neuropharmacology: enantiomer-specific behavioural and neurochemical effects in rats. Br J Pharmacol 2015, 172, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watterson, L.R.; Hood, L.; Sewalia, K.; et al. The Reinforcing and Rewarding Effects of Methylone, a Synthetic Cathinone Commonly Found in "Bath Salts". J Addict Res Ther 2012. Suppl 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi-Paydar, M.; Nguyen, J.D.; Vandewater, S.A.; et al. Locomotor and reinforcing effects of pentedrone, pentylone and methylone in rats. Neuropharmacology 2018, 134 Pt A, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.; Fu, D.; Xu, Z.; et al. Relative reinforcing effects of dibutylone, ethylone, and N-ethylpentylone: self-administration and behavioral economics analysis in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2022, 239, 2875–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, M.H.; Solis, E.; Jr Watterson, L.R.; et al. Baths salts, spice, and related designer drugs: the science behind the headlines. J Neurosci 2014, 34, 15150–15158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindler, C.W.; Thorndike, E.B.; Goldberg, S.R.; et al. Reinforcing and neurochemical effects of the "bath salts" constituents 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylcathinone (methylone) in male rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2016, 233, 1981–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarde, S.M.; Huang, P.K.; Creehan, K.M.; et al. The novel recreational drug 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) is a potent psychomotor stimulant: self-administration and locomotor activity in rats. Neuropharmacology 2013, 71, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watterson, L.R.; Kufahl, P.R.; Nemirovsky, N.E.; et al. Potent rewarding and reinforcing effects of the synthetic cathinone 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV). Addict Biol 2014, 19, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gannon, B.M.; Galindo, K.I.; Rice, K.C.; et al. Individual Differences in the Relative Reinforcing Effects of 3,4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone under Fixed and Progressive Ratio Schedules of Reinforcement in Rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2017, 361, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonano, J.S.; Glennon, R.A.; De Felice, L.J.; et al. Abuse-related and abuse-limiting effects of methcathinone and the synthetic "bath salts" cathinone analogs methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), methylone and mephedrone on intracranial self-stimulation in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014, 231, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre-Zurano, L.; Lopez-Arnau, R.; Lujan, M.A.; et al. Cannabidiol Modulates the Motivational and Anxiety-Like Effects of 3,4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) in Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.M.; Cargile, K.J.; Lunn, J.A.; et al. Characterization of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone discrimination in female Sprague-Dawley rats. Behav Pharmacol 2021, 32, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarde, S.M.; Creehan, K.M.; Vandewater, S.A.; et al. In vivo potency and efficacy of the novel cathinone alpha-pyrrolidinopentiophenone and 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone: self-administration and locomotor stimulation in male rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015, 232, 3045–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, B.M.; Rice, K.C.; Collins, G.T. Reinforcing effects of abused 'bath salts' constituents 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone and alpha-pyrrolidinopentiophenone and their enantiomers. Behav Pharmacol 2017, 28, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taffe, M.A.; Nguyen, J.D.; Vandewater, S.A.; et al. Effects of alpha-pyrrolidino-phenone cathinone stimulants on locomotor behavior in female rats. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021, 227, 108910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, J.H.; Choi, M.J.; Jang, C.G.; et al. Behavioral evidence for the abuse potential of the novel synthetic cathinone alpha-pyrrolidinopentiothiophenone (PVT) in rodents. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2017, 234, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Moura, F.B.; Sherwood, A.; Prisinzano, T.E.; et al. Reinforcing effects of synthetic cathinones in rhesus monkeys: Dose-response and behavioral economic analyses. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2021, 202, 173112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berquist, M.D., 2nd; Baker, L.E. Characterization of the discriminative stimulus effects of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone in male Sprague-Dawley rats. Behav Pharmacol 2017, 28, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, S.B.; Chen, Z.; Huang, R.; et al. "Ecstasy" to addiction: Mechanisms and reinforcing effects of three synthetic cathinone analogs of MDMA. Neuropharmacology 2018, 133, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, E.L.; Burroughs, R.L.; Baker, L.E. Effects of D1 and D2 receptor antagonists on the discriminative stimulus effects of methylendioxypyrovalerone and mephedrone in male Sprague-Dawley rats trained to discriminate D-amphetamine. Behav Pharmacol 2017, 28, 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantegrossi, W.E.; Gannon, B.M.; Zimmerman, S.M.; et al. In vivo effects of abused 'bath salt' constituent 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) in mice: drug discrimination, thermoregulation, and locomotor activity. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatch, M.B.; Dolan, S.B.; Forster, M.J. Comparative Behavioral Pharmacology of Three Pyrrolidine-Containing Synthetic Cathinone Derivatives. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2015, 354, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatch, M.B.; Dolan, S.B.; Forster, M.J. Locomotor activity and discriminative stimulus effects of a novel series of synthetic cathinone analogs in mice and rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2017, 234, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatch, M.B.; Shetty, R.A.; Sumien, N.; et al. Behavioral effects of four novel synthetic cathinone analogs in rodents. Addict Biol 2021, 26, e12987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, R.A.; Hoch, A.C.; Sumien, N.; et al. Comparison of locomotor stimulant and drug discrimination effects of four synthetic cathinones to commonly abused psychostimulants. J Psychopharmacol 2023, 37, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.T.; Abbott, M.; Galindo, K.; et al. Discriminative Stimulus Effects of Binary Drug Mixtures: Studies with Cocaine, MDPV, and Caffeine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2016, 359, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeford, A.G.P.; Sherwood, A.M.; Prisinzano, T.E.; et al. Discriminative-Stimulus Effects of Synthetic Cathinones in Squirrel Monkeys. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2021, 24, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisek, R.; Xu, W.; Yuvasheva, E.; et al. Mephedrone ('bath salt') elicits conditioned place preference and dopamine-sensitive motor activation. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012, 126, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wronikowska, O.; Zykubek, M.; Michalak, A.; et al. Insight into Glutamatergic Involvement in Rewarding Effects of Mephedrone in Rats: In Vivo and Ex Vivo Study. Mol Neurobiol 2021, 58, 4413–4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, L.; Andersson, M.; Kronstrand, R.; et al. Mephedrone, methylone and 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) induce conditioned place preference in mice. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2014, 115, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.H.; Hempel, B.J.; Clasen, M.M.; et al. Conditioned taste avoidance, conditioned place preference and hyperthermia induced by the second generation 'bath salt' alpha-pyrrolidinopentiophenone (alpha-PVP). Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2017, 156, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botanas, C.J.; Yoon, S.S.; de la Pena, J.B.; et al. The abuse potential of two novel synthetic cathinones with modification on the alpha-carbon position, 2-cyclohexyl-2-(methylamino)-1-phenylethanone (MACHP) and 2-(methylamino)-1-phenyloctan-1-one (MAOP), and their effects on dopaminergic activity. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2017, 153, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manke, H.N.; Nunn, S.S.; Sulima, A.; et al. Effects of Serial Polydrug Use on the Rewarding and Aversive Effects of the Novel Synthetic Cathinone Eutylone. Brain Sci 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.A.; Huang, S.; Manke, H.N.; et al. Conditioned taste avoidance and conditioned place preference induced by the third-generation synthetic cathinone eutylone in female sprague-dawley rats. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2023, 31, 1069–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vari, M.R.; Mannocchi, G.; Tittarelli, R.; et al. New Psychoactive Substances: Evolution in the Exchange of Information and Innovative Legal Responses in the European Union. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Drug Report 2023[N].

- World Drug Report 2022[N].

- Autho.: ESPAD Report 2019: Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs.; 2020.

- The drug situation in Europe up to 2023[N]. Available online: https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/european-drug-report/2023/drug-situation-in-europe-up-to-2023_en#level-5-section4.

- Hibbert, M.P.; Hillis, A.; Brett, C.E.; et al. A narrative systematic review of sexualised drug use and sexual health outcomes among LGBT people. Int J Drug Policy 2021, 93, 103187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.; Shahmanesh, M.; Gafos, M. Chemsex behaviours among men who have sex with men: A systematic review of the literature. Int J Drug Policy 2019, 63, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerras, J.M.; Hoyos, J.; Donat, M.; et al. Sexualized drug use among men who have sex with men in Madrid and Barcelona: The gateway to new drug use? Front Public Health 2022, 10, 997730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incera-Fernandez, D.; Roman, F.J.; Moreno-Guillen, S.; et al. Understanding Sexualized Drug Use: Substances, Reasons, Consequences, and Self-Perceptions among Men Who Have Sex with Other Men in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amundsen, E.; Haugstvedt, A.; Skogen, V.; et al. Health characteristics associated with chemsex among men who have sex with men: Results from a cross-sectional clinic survey in Norway. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0275618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoops, L.; van Amsterdam, J.; Albers, T.; et al. Slamsex in The Netherlands among men who have sex with men (MSM): use patterns, motives, and adverse effects. Sex Health 2022, 19, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).