Introduction and Background

It is now appreciated that all terrestrial and aquatic animals, insects, and plants continuously release DNA into the environment via cellular shedding and decomposition1. Upon cellular membrane rupture, nuclear and mitochondrial DNA is released directly into the local environment2, where it can be detected in soil3,4,5, water6,7,8, or even air samples9.

Following on the discovery that environmental DNA embedded within ancient sediments could be used to survey contemporaneous flora and fauna10,11, and experiments showing that naturally-occurring standing water sources contained mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from vertebrates inhabiting the watershed12, the feasibility of recovering and analyzing environmental DNA from living macro-organisms to determine both species presence and abundance was first demonstrated 15 years ago in the context of the invasive American bullfrog13. Shortly thereafter, using samples from lentic, lotic and marine waters, similar techniques were applied to study fish6,7, mammals14, crustaceans14, insects14, birds15, and reptiles16.

While the earliest studies of macro-organismal environmental DNA utilized targeted amplification of mitochondrial genes using species-specific primers13,17, the past decade has witnessed an explosion in eDNA studies that leverage nuclear genome sequences that are generally conserved across species but harbor sufficient species-specific differences to enable reliable identification from high-quality DNA sequencing. This approach, termed ‘metagenomic barcoding’ or ‘metabarcoding’18,19, essentially parallels earlier metagenomic study paradigms developed for microorganismal surveys20 that rely on targeted PCR amplification of selected genes that exhibit high diversity between species such as the 16S ribosomal subunit or mitochondrial cytochrome genes17. Although individual high-diversity genes or genomic regions may differ between studies, metabarcoding is now being applied to detect and analyze diverse species across a wide range of ecological contexts17. By contrast with micro-organismal studies where it is the norm, direct “shotgun” sequencing of eDNA samples for macro-organismal analysis is still at an exploratory stage21.

Below, we first summarize the major ecological arenas wherein eDNA analysis has been deployed, as well as major use cases. We then review current undersandings of the environmental bioavailability of extra-organismal DNA, on which eDNA studies are critically dependent, as well as common approaches to sample collection and analysis. We discuss the current state and limitations of eDNA studies with respect to sensitivity, reproducibility, and comparability between studies, and the role of sample collection and handling standards. With these topics in view, we propose that many current limitations of eDNA analysis can be addressed by in-field utilization of well-designed synthetic DNA standards or ‘tracers’ that simultaneously control for local environmental conditions and provide objective benchmarks for detection sensitivity.

Ecological Arenas

To date, the major arena of application for eDNA has been aquatic environments, which account for the majority of published eDNA studies18,22,23. Analysis of aquatic species in marine and freshwater contexts (both lentic and lotic), is facilitated by the ready diffusion of eDNA24, and the potential to increase detection sensitivity simply by filtering a greater quantity of water25.

eDNA studies in terrestrial environments have conventionally involved collection of targeted specimens, such as animal residues left on trees, fecal deposits, or samplings from hoof or paw prints in earth or snow26,27, hampering widespread application. However, the challenge of sampling terrestrial environments is currently being reassessed by the transformative discovery that the DNA of animal, insect, and non-anemophilous plants can be reliably recovered from filtered air samples28-32. In a notable study conducted at the Copenhagen Zoo28, Clare et al. showed that airborne eDNA could be collected in a localized manner and analyzed to disclose specific species within a defined geographical radius. Airborne eDNA samples thus appear to share many properties with aquatic samples, including quantitative recovery that can be used for species detection, biodiversity monitoring, and biomass estimates, as discussed below.

Application of eDNA Analysis

Because of the prevalence and high information content of eDNA, the range of potential application areas is extremely broad. Of these, those most widely described to date have focused on assessment of environmental biodiversity, estimation of species abundance or biomass, detection of specific native or invasive species, and species management. More limited but growing application areas include agriculture and forensics. Prior to discussing general aspects of the distribution and fate of eDNA in the environment and approaches to its sampling and analysis, it is useful to review the aforementioned areas of application for context.

Species Detection and Biomass Analysis

eDNA has been widely applied for both aquatic and terrestrial species detection in a variety of ecological contexts. As discussed below, in aquatic samples from lotic environments, eDNA density increases with species density and biomass, although the relationship is not linear29,30. Although data from head-to-head comparisons are limited, several studies suggest that eDNA performs favorably compared with conventional gold-standard methods, and may in some cases produce superior results. For example, several eDNA-based surveys for rare fish or amphibians have reported greater sensitivity than traditional methods6,7,31. In measurements of fish biomass, eDNA analysis performs at least as well as standard (and laborious) electrofishing or trawling catch approaches for target species, and may detect species not found using conventional approaches32,32,33. However, for the vast majority of applications, comparable conventional survey data are unavailable, complicating or precluding quantitative assessment of detection sensitivity.

Environmental Biodiversity

Accurate measurement of species abundance is vital for ecological surveys, and species management and conservation efforts. Conventional approaches to biodiversity surveys involve direct observation and counting of species members by sampling at fixed locations, such as stationary cameras34 or electrofishing from specific bank locations35. eDNA analysis has been applied to quantify and monitor freshwater aquatic biodiversity in both rural and urban lakes36 and in rivers and streams37. It has also been applied to assessment and monitoring of biodiversity in diverse coastal marine environments38–40. Application to terrestrial biodiversity has been more limited, though a number of environmental contexts have been studied ranging from forestlands to caves41–43.

Detection and Monitoring of Invasive Species

As noted above, the feasibility of recovering and analyzing environmental DNA to detect living macroorganisms was first demonstrated in the context of an aquatic invasive species13. Since that time, eDNA has been broadly applied to detection and monitoring of invasive fish, shellfish, and aquatic plant species using both species-targeted (via PCR) and biosurvey (metabarcoding) approaches44. Recent approaches for in-field eDNA sampling and sequencing appear to be of high utility for invasive species detection45, and it has been suggested that eDNA analysis has reached the point where it can be widely used for invasive species management46.

Detection of Rare or Threatened Species

An important component of species conservation efforts is accurate detection of rare or threatened species within a given geographical locale. eDNA has been extensively applied to this problem in the context of rare and hard to detect aquatic species22, and diverse endangered or threatened terrestrial and aquatic species such as Canada lynx27, the greater crested newt 17, the Gouldian finch47, and bull trout32.

Conservation, Environmental Monitoring, and Population Management

eDNA analysis is already playing an impactful role in species conservation and population management23,48, as well as general assessments of population health. Conservation and management of fish populations has been a particularly active area of application49. eDNA has also been applied to various aspects of the assessment and monitoring of population health for diverse species such as the health of kelp forests in marine ecosystems50; health of coral reefs51; tracking of fish spawning behaviors52; diet and feeding behaviors of terrestrial animals53; and control and management of eutrophication54. In the context of species management monitoring, eDNA analysis has seen a number of applications ranging from sportfish55 to monitoring environmental restoration following dam removal56.

Agriculture

Agriculture represents an emerging area of eDNA application57,58, with potential for monitoring of pests and pathogens59,60. However, although the potential is great, to date applications have been limited compared with those targeting wild plant and animal populations.

Forensics

Another emerging area of eDNA application is in forensic analysis, wherein environmental samples such as water or dust can be used to detect human DNA61 or geographically localize human-environment encounters62.

All of the above applications depend on the ability of eDNA to accurately and sensitively detect specific species and to enable estimation of species biomass based on eDNA abundance. A key factor in all eDNA analyses, however, is the availability, state, and fate of DNA released by target species in their natural environments.

Fate of eDNA in the Environment

Despite the critical dependence of eDNA studies on the distribution, persistence, and quantitative representation of macro-organismal DNA released into the environment as either cells or free nucleic acid, surprisingly little is currently known about its environmental kinetics.

Shedding and Decay of eDNA

For any given species, the level of eDNA in the environment reflects a balance between its rate of production via shedding and its rate of decay. These factors have been examined in both observational studies using field samples and controlled or contained aquatic environment studies. Observational studies indicate that the rate at which different aquatic species shed eDNA into the environment varies considerably33, 63, though to date shedding has been examined for only a small number of aquatic species64 and data for terrestrial animals are currently lacking. Apart from water temperature65, the factors that influence the environmental shedding rates of any particular species under normal living conditions are currently unknown.

The rate at which eDNA decays in its natural environment may be influenced by a number of factors related to local conditions. Initial studies indicated that eDNA may be detected in surface water up to 25 days following the disappearance of the originating organism6,66,67. Studies of field samples have identified easily measurable local environmental conditions that impact decay rates for aquatic eDNA, including water temperature65, humidity68, and chlorophyll concentration69. More difficult to measure conditions such as total cross-organism eDNA concentration can also influence degradation rates69, and is likely to vary widely between different locations. UV exposure may also play a significant role70 but is highly time- and location-specific and difficult to quantify. The impact of UV exposure also depends on the physical state of eDNA, as intracellular eDNA appears to be less sensitive to solar radiation than extracellular eDNA71. Finally, the physical state of eDNA itself may play a significant role in environmental persistence.

In general, it appears that DNA fragment size plays a significant role in aquatic eDNA recovery, with longer fragments displaying differential persistence vs. shorter fragments72. How this feature varies further with local conditions, or whether it holds for non-aquatic environments is unknown.

Controlled environment studies of eDNA largely support these conclusions. Controlled tank experiments of eDNA survival have revealed relationships between water temperature and fish biomass, with shorter survival times at higher temperatures that are counterbalanced by higher shedding rates73. In laboratory experiments using collected pondwater or seawater, eDNA in both cellular and free forms decreased exponentially with time74. In controlled aquarium studies using multiple resident species, eDNA from an introduced and then removed species became undetectable after 48 hours75. Controlled environment has been used to assess shedding and decay rates at different levels of biomass76. In general, longer DNA fragments decay more quickly, but conversely represent biomass more accurately77. Experiments in artificial ponds have shown that eDNA detection is related to species density, and that a 2.5-fold increase in the density of fish per cubic meter increases the probability of detection 5-fold at stable temperature78

Analogous results have been obtained from sampling natural environments, although careful studies of the relationship between detectability and species density or biomass are limited. In aquatic samples from lotic environments, eDNA density has been found to increase with species density and biomass as evaluated using standard field sampling methods such as electrofishing32, although the relationship is not linear29,30. Similar results have been obtained from both freshwater lentic environments55 and from comparison with trawling catches in marine environments33. In a review of 63 aquatic eDNA studies spanning an 8-year period (2012-2020), Rourke et al. found that 90% identified positive relationships between eDNA concentration species density or biomass79.

Distribution and Dispersion of eDNA

Following shedding, eDNA is subjected to local forces such as currents or wind that create geographical gradients and influence environmental persistence. In practice, however, such gradients are almost impossible to measure in advance.

The distribution of aquatic eDNA has been studied in a variety of contexts. In lotic systems, eDNA can be detected at surprising distance – up to two kilometers – from its source24. While this may facilitate detection, it must be presumed that eDNAs from different species within lotic systems are highly mixed. By contrast, in lentic systems, eDNA is localized, providing a better measure of relative species abundance80. In marine environments, water stratification impairs vertical dispersion of eDNA81, creating depth-defined ecosystems that can be systematically sampled for eDNA50. Attempts have been made to model aquatic eDNA dispersion in lotic systems82, but such models are difficult to implement as relevant field data parameters are lacking.

Sampling and Analytical Methods

Although the number of eDNA studies has increased rapidly, the sheer diversity of species and environmental conditions sampled is such that most studies are singular reports. Indeed many studies, particularly those employing metabarcoding for biodiversity sampling, use subjective sampling methods and/or ad hoc field collection methods that do not provide sufficient data to reproduce the fundings83.

Sample Collection and eDNA Extraction

A variety of studies have addressed sample collection approaches in both aquatic and terrestrial environments, focusing on strategies for filtration 84; sample preservation85–87; and other aspects of physical collection and handling. These considerations should apply to any study of eDNA, but are particularly important for metabarcoding studies and those that attempt to amplify multiple DNA targets within a sample. Variables that have been investigated and shown to influence sample integrity include water temperature, different eDNA collection approaches, and eDNA separation approaches such as centrifugation or membrane filtration.

eDNA Particle Sizes and Capture Methods

Animal-derived eDNA exists in many environmental forms including intact whole cells or multicellular aggregates; intact free-floating nuclei or mitochondria; cell fragments; free nucleic acids; and nucleic acids or cell fragments complexed with other organic or inorganic substances88. The aforementioned categories of eDNA can be fractionated on the basis of particle size88, though some particles and particularly free eDNA may exhibit preferential adherence to filtration membranes89.

Use of different capture methods can have a significant impact on eDNA recovery90. Using a spike-in strategy employing chicken DNA, Kirtane et al.84 showed that filtered aquatic samples bound to a membrane showed higher integrity and recovery vs. dissolved samples or those bound to an environmental surface that was collected at the same time. Others have also noted the stability on nitrocellulose filters85.

Timing of Sample Collection

As noted above, environmental temperature is negatively correlated with eDNA sample survival, with cool temperatures increasing sample integrity91. Given the demonstrated role of temperature in environmental eDNA persistence, both the timing of sample collection during the day and seasonal variation are expected to play significant roles in eDNA detection via modulation of both eDNA shedding and persistence in the environment92,93, or seasonal variations that impact population health53.

Controls Strategies

In-laboratory controls for PCR are standard practice, and control strategies for other aspects of sample collection and handling have been proposed in the context of standards development (see below). However, published eDNA analysis studies to date do not incorporate any form of environmental or in-field controls.

Sensitivity, Reproducibility, and Standards

Detection Sensitivity

Presently, the sensitivity of most eDNA studies is unknown. As noted above, very few studies have benchmarked eDNA analysis with conventional detection approaches such as camera traps or species enumeration methods such as electrofishing. For example, limit of detection (LOD) is a standard parameter for PCR assays targeting a specific genomic region, yet remains unreported for most targeted eDNA studies94. From the limited data that do exist, a general conclusion that may be drawn is that eDNA shows promising sensitivity, though results from any individual study are highly dependent on specific environmental conditions and locations.

As discussed above, many environmental and experimental variables may impact the sensitivity of eDNA studies. A prominent variable affecting sensitivity across ecological arenas is sampling volume (water, air, or solid matter). Geographical sampling over a wide area can increase sensitivity for detection of multiple species simultaneously, although large numbers of samples may be required 95. Repeated sampling from a given location can likewise increase detection sensitivity96. However, apart from the general principle that more sample volume is better, and apart from adherence to routine sample preservation techniques, it is difficult to identify any factors that would be expected to increase detection sensitivity across environments. A general solution to the problem of detection sensitivity, while critical for biodiversity, species conservation, and management applications, remains elusive.

Detection of Exogenous DNA

Whether in fully controlled environments such as tanks or in the field, a key limitation of the assessment of eDNA detection methods is that there is no way to determine the starting concentration of eDNA used in the experiment. This is particularly important for comparing different methods of eDNA collection. Introduction of exogenous or DNA sequences represents a powerful approach for controlled study of the fate of eDNAs in the environment and, as noted above, during sample collection and processing84. One solution proposed by Bockrath et al. is to use eDNA of a target species that has been cloned into cellular material such as E. coli97. The advantage of this approach is that eDNA recovery can be strictly measured as a function of the number of input cells, which can be diluted to various concentrations. Currently, however, the literature is almost devoid of studies in which exogenous eDNA has been introduced into a natural environment. In a unique study, by introducing eDNA from a non-native fish species into an isolated bay, Ely et al. were able to quantify the diffusion and persistence introduced eDNA98. Presumably this approach could be generalized for other species and environments, as discussed below.

Reproducibility of eDNA Studies

The inability to replicate many field ecological studies regardless of analytical approach post sample collection has recently been highlighted99. It is notable that even a small amount of replication – even the simple collection of >1 sample from a given location – can have a significant positive impact on both the sensitivity and accuracy of results100. In the specific context of eDNA, Dickie et al. concluded that it was only possible to replicate 5% of the metabarcoding studies conducted in their sample83. Even if this represents an extreme, it is probably safe to conclude that the reproducibility of contemporary eDNA studies faces many challenges and is likely to be far less than optimal.

Development of Standards for Sample Collection and Handling

The systematic application of sample collection, handling, and analysis standards would likely be of great benefit to the broader field of eDNA-based research by increasing both the reproducibility of results from a given study as well as the comparability of results across studies. The past few years have accordingly witnessed an increasing frequency of calls for establishment of eDNA standards101, proposals for specific ecological arenas, and the emergence of detailed and instructions and field guides for sample collection and handling 73,87,102, as well as devices for automated sampling103. However, these efforts almost exclusively address mechanical aspects of sample collection and post-sample handling analysis vs. controlling for the local environmental conditions in which samples are obtained.

While helpful, because of their exclusive focus on post-collection handling, none of these proposed standards has the potential to address the key pre-collection environmental factors discussed above.

Summary of Key Challenges

Although potentially powerful, current eDNA studies face three main challenges: (1) detection sensitivity; (2) control for eDNA persistence and dispersion; and (3) inability to compare across studies at different times or locations, including both targeted studies of the same organism and broader environmental biodiversity studies. Numerous reviews and commentaries have advocated for the implementation of standard operating procedures for sample collection and laboratory processing. However, these measures alone have limited potential to surmount the aforementioned key challenges because they do not address a core issue: controlling for environmental context and local conditions that impact the persistence and recovery of eDNA.

Quantifying Detection Sensitivity

As described in the preceding sections, environmental context and local conditions play a dominant role in eDNA studies by modulating the relative availability of eDNA for study. Using current approaches, there is no way to systematically determine the influence of the local environment on eDNA degradation or dispersion, particularly as a function of the DNA molecule size and concentration. As noted, detection sensitivity can be increased by increasing the volume of sampled material (e.g., filtered water or air) or by repeated molecular sampling via PCR amplification from the same sample, though it is notable that this strategy has not yet been applied in the context of the PCR amplification step used for library construction in metabarcoding studies.

Measuring the Unmeasured: Free eDNA

It is notable that the smallest filter size used in conventional eDNA research permits flow through of particles less than 0.2μ in size. As such, virtually all free (i.e., not bound to cellular or other substrates) eDNA molecules are part of the flow-through. Although the proportion of this size compartment relative to all eDNA from a given species is unknown, it is reasonable to presume that it is significant and as such should be assayed to enhance species detection.

Controlling for eDNA Persistence and Dispersion

While sampling and post-sample handling procedures may impact some aspects of detection sensitivity, they cannot control for local factors that determine the availability of eDNA including shedding rates, dispersion, and decay. Of these, the first is an intrinsic feature that cannot be explicitly controlled for. By contrast, dispersion and decay are features of eDNA molecules once they enter the environment and thus could in principle be addressed by introduction and quantification of exogenous DNA controls.

A Potential Solution: Synthetic DNA Tracers

Prefabricated reference nucleic acids have been in use for decades as controls for standardizing molecular detection ranging from gel electrophoresis to PCR. ‘Spiking in’ a synthetic nucleic acid that is amplified simultaneously with the target sequence provides both an internal control and a basis for comparing between separate detection reactions. For example, such spike-in controls are used in common diagnostic tests such as COVID-19 or HIV detection from nasal or blood samples, respectively. Most such standards are either derived from or are synthesized to replicate naturally-occurring sequences.

As noted earlier, very few eDNA studies have attempted to use any types of exogenous DNA sequences as controls added to environmental samples84,98. To date, only one study has reported the use of exogenous eDNA control sequences introduced into the environment prior to sample collection 98, and only a singular study has attempted to use recombinant DNA and synthetic biology techniques to create an enhanced control reagent97,98. By contrast, studies of the fate of synthetic DNA molecules, whether circular plasmids108 or linear molecules106, are more numerous.

Synthetic DNA has been used for many years as a hydrologic tracer, and its environmental stability and advection properties have been shown to be sufficient for this application104–107. It is thus surprising that synthetic DNA has yet to be widely applied in the control of eDNA experiments, particularly in the context of controlling for otherwise difficult-to-ascertain features of the local environment.

Several conclusions can be drawn from the aforementioend studies of DNA tracers. First, synthetic DNA molecules are easily delivered to an aquatic environment, where they can be readily recovered from water samples in the absence of filtration. Second, free DNA molecules can persist in the environment for many days without degradation. Third, free synthetic DNA molecules adsorb to environmental features such as streambeds or sediments, which can preserve them for extended periods. Fourth, synthetic DNA molecules undergo wide dispersion that parallels local hydrological features such as currents or vertical water column turnover.

Manufacture and Molecular Scale of Synthetic DNA

During the past decade, the capability to manufacture any DNA sequence up to hundreds of base pairs in length with high accuracy and high molecular scale has been commoditized. For example, standard synthesis of a 100bp molecule at micromolar scale costs roughly $100-200 and provides a sufficient number of molecules that, if evenly distributed, would reach a concentration of >200 copies per ml (i.e., well within the target range of PCR) in a large lake with a volume of 3 billion cubic meters.

Designing Synthetic DNA Standards for eDNA Research

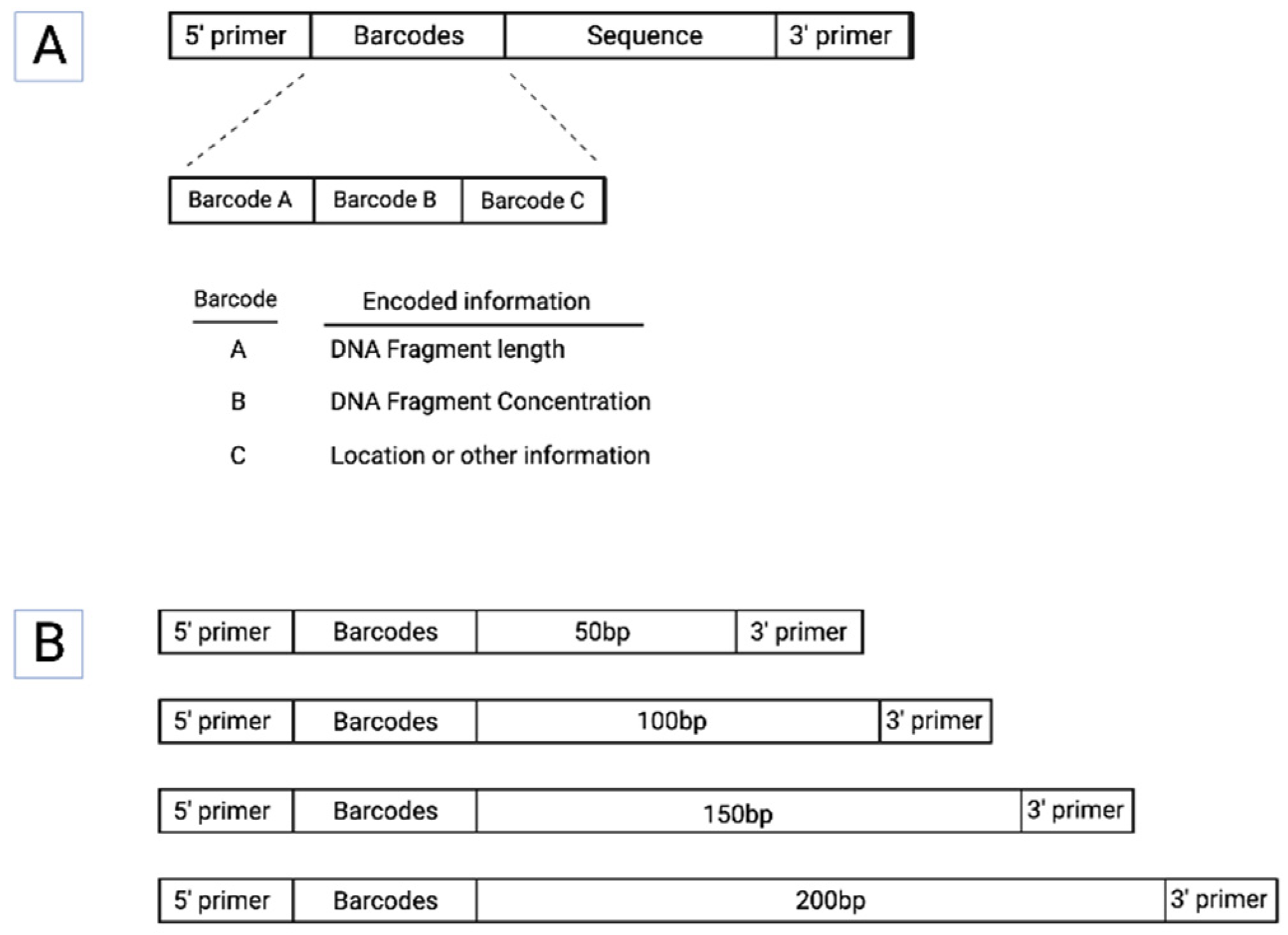

A number of desirable features for synthetic DNA tracers that could be used as in-field standards for eDNA research can be proposed. In addition to 3’ and 5’ PCR primer targets, a key design feature would be the incorporation of DNA barcodes that encode information about individual fragments such as their length and starting concentrations (

Figure 1). Other key design considerations include the following:

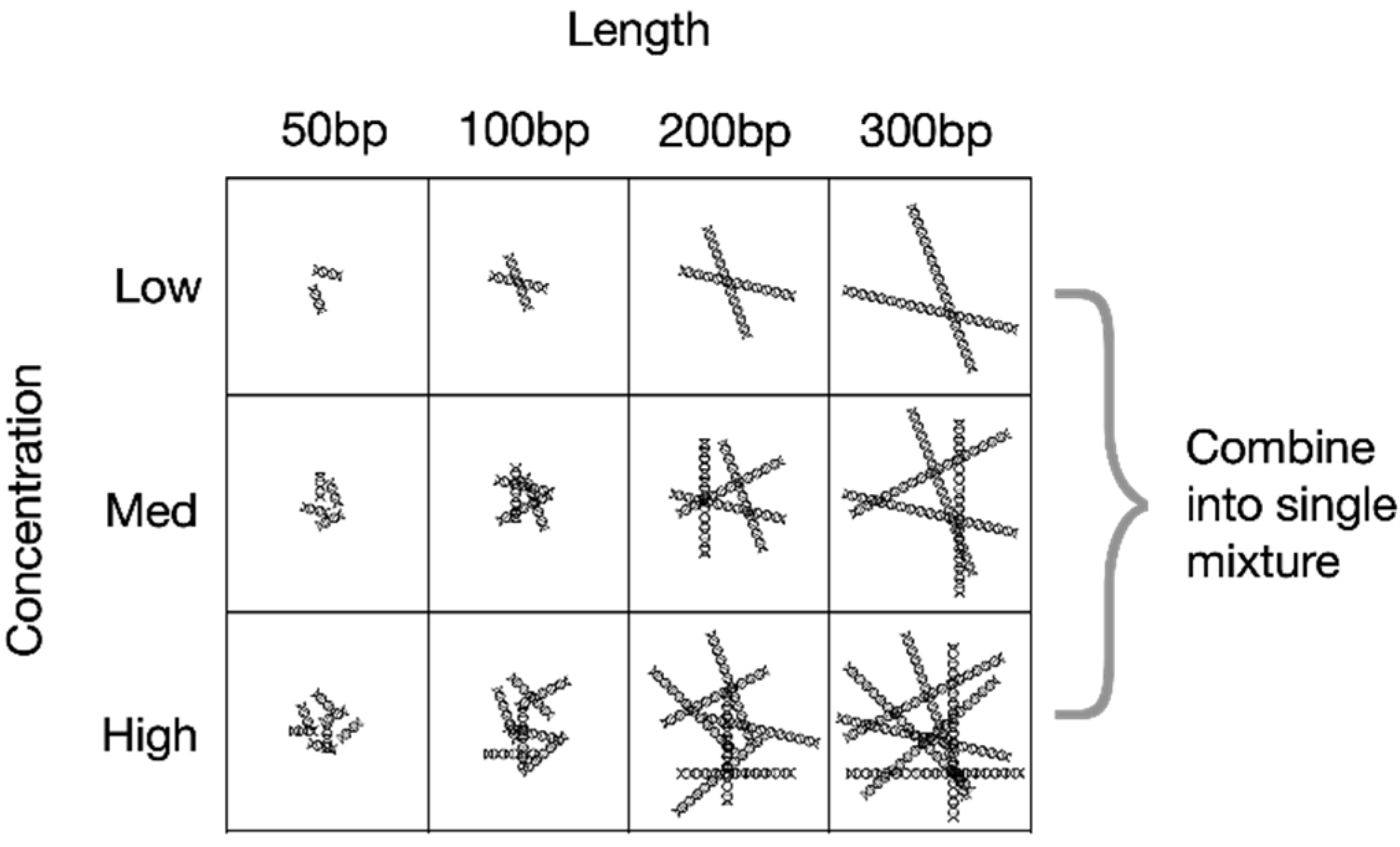

DNA sequence length. As discussed above, the length of a DNA is a major determinant of its environmental survival, with longer sequences disfavored. Given that naturally occurring eDNA is of variable length, it will be ideal to include a range of sequence lengths within a synthetic control. Ideally, sequences of different length could be designed as progressively longer subsequences of the longest fragment.

Amplification efficiency. Synthetic molecular standards should ideally be designed to control for in-reaction features such as amplification efficiency. Sequences that are less efficient to amplify such as those with high G+C content, or longer sequences, will be disproportionately selected against during multiple rounds of amplification, and the opposite is true for sequences that are very easy to amplify. Calculation of amplification efficiency is well-understood and using standard software packages, sequences of different lengths can be designed to maximize uniformity match specific desired target ranges for amplification.

Sequence uniqueness. Using synthetic DNA sequences that are highly similar to naturally occurring sequences can compromise the analysis of results. An approach to creating unique sequences that have the same properties in PCR amplification and bioinformatic processing as naturally occurring sequences is to use the reverse sequence (but not the reverse completment)109. Because their sequence composition and context is identical to the forward form, their behavior during both molecular and computational handling is identical to the original form. Thus, in the case of synthetic controls, this allows for the inclusion of both forward and reverse sequences of a given control within the same reaction, providing an internal control for otherwise difficult to account for aspects of sample or laboratory handling. For example, creating a set of control sequences from a reversed mitochondrial genome would have the same experimental handling properties as the natural sequences while avoiding cross-talk during amplification or processing.

Concentration. DNA fragment concentration is another critical parameter influencing detection. For a given control mixture, the starting concentration of fragments of different lengths could be pre-specified such that each fragment length is present at a range of different concentrations. This would permit not only qualitative (i.e., yes/no) assessment of the detection of a given DNA sequence, but also the power of detection as a function of concentration.

Encoding of length and concentration information. A key advantage of synthetic DNA is that it can be designed to encode a substantial amount of information using sequence ‘barcodes’ comprising the 4 DNA bases. For example, the length of a DNA fragment can be directly encoded into its DNA sequence via a barcode (

Figure 1). Similarly, the concentrations of different batches of the same sequence of the same length can be directly encoded. Pools of barcoded fragments of different lengths could readily be formulated at different concentrations, where each length x concentration pool comprised synthetic standards into which that length and concentration were barcoded (

Figure 2). As such, sequencing of a pool of recovered fragments amplified using generic primers would reveal how well DNA fragments of each length and starting concentration each was being recovered.

Encoding other data and metadata. Because DNA uses base 4 vs. the more familiar binary base 2, it can encode a large number of possible combinations within relatively few bases. Such additional information might include process metadata such as date of synthesis, design version, etc. If DNA standards were to be utilized for different geographical locations, this information (longitude, latitude, etc.) could be directly encoded within all DNA fragments destined to be used at that location.

Synthesis and Packaging

Once designed, synthetic DNA controls can be synthesized very inexpensively and at very large molecular scale. DNA standards could be delivered as naked DNA, or could be encapsulated into lipid nanoparticles which may extend their lifetime in the environment. While the absolute number of molecules in a pool of DNA fragments will be much larger, these fragments will be partitioned into a smaller number of nanoparticles, lowering their effective concentration in the environment. However, the number of nanoparticles that can be produced is also very large and the ability to control the amount of DNA per particle affords additional experimental flexibility. Lipid encapsulation can also produce particles of varying sizes up to 300nm in diameter, which would be recoverable using standard 0.2μm eDNA filtration membranes.

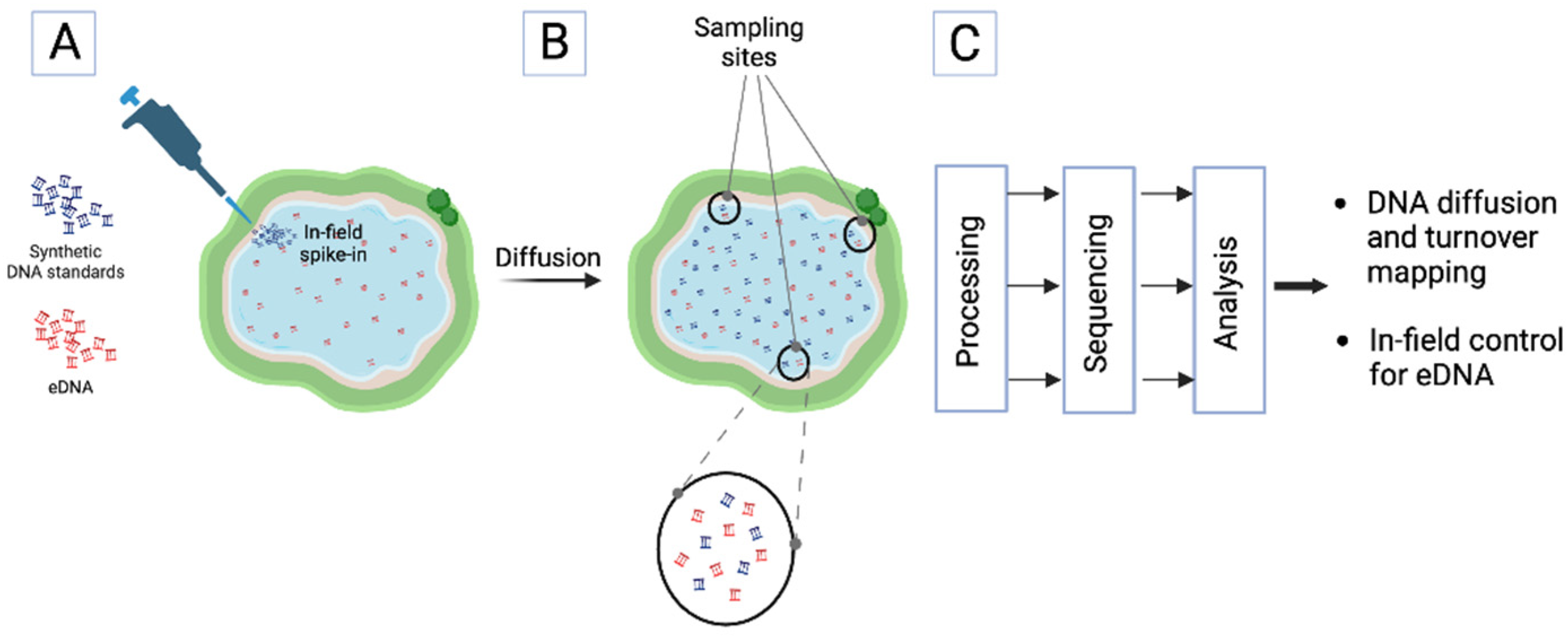

Field Application: Mapping DNA diffusion and turnover

Synthetic DNA standards mixtures could be readily deployed in the environment, most easily for aquatic studies but also in principle for terrestrial or airborne studies. Example applications could include timed diffusion studies in lentic systems. Seeding synthetic DNA standards at specific points along a body of water and then collecting timed samples at different locations could be used to map local eDNA diffusion patterns and survival rates for different fragment lengths and concentrations (

Figure 3). Similar studies could be undertaken in lotic systems by introduction of control samples upstream of sampling locations.

Conclusions and Prospects

eDNA analysis is currently reshaping the landscape of species enumeration and management. While most studies to date have been conducted using aqueous samples, recent successes in harvesting eDNA from filtered air samples indicate that the field is poised for even broader expansion into terrestrial ecosystems. Regardless of the sampling approach and medium, sensitivity of detection and comparability between studies represent two major deficits confronting the field. We have proposed that these may be addressed in part by the in-field application of carefully designed molecular DNA species that can function as both environmental tracers and internal detection standards. Experiments to validate this approach should be readily feasible, and could lead to the development of an inexpensive universal standard mixture that would enable comparability between studies and hence the emergence of consensus conclusions that can strengthen the position of eDNA studies to inform environmental management.

Author Contributions

G.G.S researched and wrote the paper, and designed and created the figures; T.P. oversaw and guided research and edited the paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was performed while G.G.S. was a Research Intern at University of Washington. The authors thank Dr. Christine Queitsch (UW) for providing advice and laboratory opportunities; Dr. Hao Wang for helpful discussions and advice on PCR design and calculations involving synthetic DNA; and Ms. Erin Alm for help managing references.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no competing interest.

References

- Bohmann, K. et al. Environmental DNA for wildlife biology and biodiversity monitoring. Trends Ecol. Evol. 29, 358–367 (2014).

- Harrison, J. B., Sunday, J. M. & Rogers, S. M. Predicting the fate of eDNA in the environment and implications for studying biodiversity. Proc. Biol. Sci. 286, 20191409 (2019).

- Yoccoz, N. G. et al. DNA from soil mirrors plant taxonomic and growth form diversity. Mol. Ecol. 21, 3647–3655 (2012).

- Parducci, L. et al. Ancient plant DNA in lake sediments. New Phytol. 214, 924–942 (2017).

- Lin, M. et al. Landscape analyses using eDNA metabarcoding and Earth observation predict community biodiversity in California. Ecol. Appl. 31, e02379 (2021).

- Thomsen, P. F. et al. Detection of a diverse marine fish fauna using environmental DNA from seawater samples. PLoS One 7, e41732 (2012).

- Jerde, C. L., Mahon, A. R., Chadderton, W. L. & Lodge, D. M. “Sight-unseen” detection of rare aquatic species using environmental DNA. Conserv. Lett. 4, 150–157 (2011).

- Deiner, K., Walser, J.-C., Mächler, E. & Altermatt, F. Choice of capture and extraction methods affect detection of freshwater biodiversity from environmental DNA. Biol. Conserv. 183, 53–63 (2015).

- Johnson, M. D., Cox, R. D. & Barnes, M. A. Analyzing airborne environmental DNA: A comparison of extraction methods, primer type, and trap type on the ability to detect airborne eDNA from terrestrial plant communities. Environ. DNA 1, 176–185 (2019).

- Johnson, M. D. et al. Environmental DNA as an emerging tool in botanical research. Am. J. Bot. 110, e16120 (2023).

- Willerslev, E. et al. Diverse plant and animal genetic records from Holocene and Pleistocene sediments. Science 300, 791–795 (2003).

- Martellini, A., Payment, P. & Villemur, R. Use of eukaryotic mitochondrial DNA to differentiate human, bovine, porcine and ovine sources in fecally contaminated surface water. Water Res. 39, 541–548 (2005).

- Ficetola, G. F., Miaud, C., Pompanon, F. & Taberlet, P. Species detection using environmental DNA from water samples. Biol. Lett. 4, 423–425 (2008).

- Foote, A. D. et al. Investigating the potential use of environmental DNA (eDNA) for genetic monitoring of marine mammals. PLoS One 7, e41781 (2012).

- Thomsen, P. F. et al. Monitoring endangered freshwater biodiversity using environmental DNA. Mol. Ecol. 21, 2565–2573 (2012).

- Piaggio, A. J. et al. Detecting an elusive invasive species: a diagnostic PCR to detect Burmese python in Florida waters and an assessment of persistence of environmental DNA. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 14, 374–380 (2014).

- Rees, H. C., Maddison, B. C., Middleditch, D. J., Patmore, J. R. M. & Gough, K. C. REVIEW: The detection of aquatic animal species using environmental DNA - a review of eDNA as a survey tool in ecology. J. Appl. Ecol. 51, 1450–1459 (2014).

- Deiner, K. et al. Environmental DNA metabarcoding: Transforming how we survey animal and plant communities. Mol. Ecol. 26, 5872–5895 (2017).

- Ruppert, K. M., Kline, R. J. & Rahman, M. S. Past, present, and future perspectives of environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding: A systematic review in methods, monitoring, and applications of global eDNA. Global Ecology and Conservation 17, e00547 (2019).

- Riesenfeld, C. S., Schloss, P. D. & Handelsman, J. Metagenomics: genomic analysis of microbial communities. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38, 525–552 (2004).

- Serite, C. P. et al. eDNA metabarcoding vs metagenomics: an assessment of dietary competition in two estuarine pipefishes. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, (2023).

- Lewis, D. Rare bird’s detection highlights promise of “environmental DNA.” Nature 575, 423–424 (2019).

- Banerjee, P. et al. Reinforcement of Environmental DNA Based Methods (Sensu Stricto) in Biodiversity Monitoring and Conservation: A Review. Biology 10, (2021).

- Baudry, T. et al. Influence of distance from source population and seasonality in eDNA detection of white-clawed crayfish, through qPCR and ddPCR assays. Environmental DNA 5, 733–749 (2023).

- Mächler, E., Deiner, K., Spahn, F. & Altermatt, F. Fishing in the Water: Effect of Sampled Water Volume on Environmental DNA-Based Detection of Macroinvertebrates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 305–312 (2016).

- Bohmann, K., Schnell, I. B. & Gilbert, M. T. P. When bugs reveal biodiversity. Mol. Ecol. 22, 909–911 (2013).

- Franklin, T. W. et al. Using environmental DNA methods to improve winter surveys for rare carnivores: DNA from snow and improved noninvasive techniques. Biol. Conserv. 229, 50–58 (2019).

- Clare, E. L. et al. Measuring biodiversity from DNA in the air. Current biology: CB vol. 32 693-700.e5 (2022).

- Sint, D., Kolp, B., Rennstam Rubbmark, O., Füreder, L. & Traugott, M. The amount of environmental DNA increases with freshwater crayfish density and over time. Environmental DNA 4, 417–424 (2022).

- Coulter, D. P. et al. Nonlinear relationship between Silver Carp density and their eDNA concentration in a large river. PLoS One 14, e0218823 (2019).

- Dejean, T. et al. Improved detection of an alien invasive species through environmental DNA barcoding: the example of the American bullfrog Lithobates catesbeianus. J. Appl. Ecol. 49, 953–959 (2012).

- McKelvey, K. S. et al. Sampling large geographic areas for rare species using environmental DNA: a study of bull trout Salvelinus confluentus occupancy in western Montana. J. Fish Biol. 88, 1215–1222 (2016).

- Kirtane, A. et al. Quantification of Environmental DNA (eDNA) shedding and decay rates for three commercially harvested fish species and comparison between eDNA detection and trawl catches. Environmental DNA 3, 1142–1155 (2021).

- Lyet, A. et al. eDNA sampled from stream networks correlates with camera trap detection rates of terrestrial mammals. Sci. Rep. 11, 11362 (2021).

- Olds, B. P. et al. Estimating species richness using environmental DNA. Ecol. Evol. 6, 4214–4226 (2016).

- Wang, S., Zhang, P., Zhang, D. & Chang, J. Evaluation and comparison of the benthic and microbial indices of biotic integrity for urban lakes based on environmental DNA and its management implications. J. Environ. Manage. 341, 118026 (2023).

- Deiner, K., Fronhofer, E. A., Mächler, E., Walser, J.-C. & Altermatt, F. Environmental DNA reveals that rivers are conveyer belts of biodiversity information. Nat. Commun. 7, 12544 (2016).

- Holman, L. E. et al. Detection of introduced and resident marine species using environmental DNA metabarcoding of sediment and water. Sci. Rep. 9, 11559 (2019).

- McClenaghan, B., Compson, Z. G. & Hajibabaei, M. Validating metabarcoding-based biodiversity assessments with multi-species occupancy models: A case study using coastal marine eDNA. PLoS One 15, e0224119 (2020).

- Port, J. A. et al. Assessing vertebrate biodiversity in a kelp forest ecosystem using environmental DNA. Mol. Ecol. 25, 527–541 (2016).

- Valentin, R. E. et al. Moving eDNA surveys onto land: Strategies for active eDNA aggregation to detect invasive forest insects. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 20, (2020).

- Utzeri, V. J. et al. Entomological signatures in honey: an environmental DNA metabarcoding approach can disclose information on plant-sucking insects in agricultural and forest landscapes. Sci. Rep. 8, 9996 (2018).

- Vörös, J., Márton, O., Schmidt, B. R., Gál, J. T. & Jelić, D. Surveying Europe’s Only Cave-Dwelling Chordate Species (Proteus anguinus) Using Environmental DNA. PLoS One 12, e0170945 (2017).

- Mychek-Londer, J. G., Balasingham, K. D. & Heath, D. D. Using environmental DNA metabarcoding to map invasive and native invertebrates in two Great Lakes tributaries. Environmental DNA 2, 283–297 (2020).

- Thomas, A. C., Nguyen, P. L., Howard, J. & Goldberg, C. S. A self-preserving, partially biodegradable eDNA filter. Methods Ecol. Evol. 10, 1136–1141 (2019).

- Sepulveda, A. J., Nelson, N. M., Jerde, C. L. & Luikart, G. Are Environmental DNA Methods Ready for Aquatic Invasive Species Management? Trends Ecol. Evol. 35, 668–678 (2020).

- Day, K. et al. Development and validation of an environmental DNA test for the endangered Gouldian finch. Endanger. Species Res. 40, 171–182 (2019).

- Huang, S., Yoshitake, K., Watabe, S. & Asakawa, S. Environmental DNA study on aquatic ecosystem monitoring and management: Recent advances and prospects. J. Environ. Manage. 323, 116310 (2022).

- Yao, M. et al. Fishing for fish environmental DNA: Ecological applications, methodological considerations, surveying designs, and ways forward. Mol. Ecol. 31, 5132–5164 (2022).

- Monuki, K., Barber, P. H. & Gold, Z. eDNA captures depth partitioning in a kelp forest ecosystem. PLoS One 16, e0253104 (2021).

- Fraija-Fernández, N. et al. Marine water environmental DNA metabarcoding provides a comprehensive fish diversity assessment and reveals spatial patterns in a large oceanic area. Ecol. Evol. 10, 7560–7584 (2020).

- Tsuji, S. & Shibata, N. Identifying spawning events in fish by observing a spike in environmental DNA concentration after spawning. Environ. DNA 3, 190–199 (2021).

- Tournayre, O. et al. eDNA metabarcoding reveals a core and secondary diets of the greater horseshoe bat with strong spatio-temporal plasticity. Environ. DNA 3, 277–296 (2021).

- Liu, Q. et al. A Review and Perspective of eDNA Application to Eutrophication and HAB Control in Freshwater and Marine Ecosystems. Microorganisms 8, (2020).

- Spear, M. J., Embke, H. S., Krysan, P. J. & Vander Zanden, M. J. Application of eDNA as a tool for assessing fish population abundance. Environmental DNA 3, 83–91 (2021).

- Duda, J. J. et al. Environmental DNA is an effective tool to track recolonizing migratory fish following large-scale dam removal. Environ. DNA 3, 121–141 (2021).

- Soares, S., Rodrigues, F. & Delerue-Matos, C. Towards DNA-Based Methods Analysis for Honey: An Update. Molecules 28, (2023).

- Kestel, J. H. et al. Applications of environmental DNA (eDNA) in agricultural systems: Current uses, limitations and future prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 847, 157556 (2022).

- Bass, D., Christison, K. W., Stentiford, G. D., Cook, L. S. J. & Hartikainen, H. Environmental DNA/RNA for pathogen and parasite detection, surveillance, and ecology. Trends Parasitol. 39, 285–304 (2023).

- Apangu, G. P. et al. Environmental DNA reveals diversity and abundance of Alternaria species in neighbouring heterogeneous landscapes in Worcester, UK. Aerobiologia 38, 457–481 (2022).

- Antony Dass, M. et al. Assessing the use of environmental DNA (eDNA) as a tool in the detection of human DNA in water. J. Forensic Sci. 67, 2299–2307 (2022).

- Foster, N. R. et al. The utility of dust for forensic intelligence: Exploring collection methods and detection limits for environmental DNA, elemental and mineralogical analyses of dust samples. Forensic Sci. Int. 344, 111599 (2023).

- Andruszkiewicz Allan, E., Zhang, W. G., C. Lavery, A. & F. Govindarajan, A. Environmental DNA shedding and decay rates from diverse animal forms and thermal regimes. Environmental DNA 3, 492–514 (2021).

- Moushomi, R., Wilgar, G., Carvalho, G., Creer, S. & Seymour, M. Environmental DNA size sorting and degradation experiment indicates the state of Daphnia magna mitochondrial and nuclear eDNA is subcellular. Sci. Rep. 9, 12500 (2019).

- Schmidt, K. J., Soluk, D. A., Maestas, S. E. M. & Britten, H. B. Persistence and accumulation of environmental DNA from an endangered dragonfly. Sci. Rep. 11, 18987 (2021).

- Dejean, T. et al. Persistence of environmental DNA in freshwater ecosystems. PLoS One 6, e23398 (2011).

- Pilliod, D. S., Goldberg, C. S., Arkle, R. S. & Waits, L. P. Factors influencing detection of eDNA from a stream-dwelling amphibian. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 14, 109–116 (2014).

- Naef, T. et al. How to quantify factors degrading DNA in the environment and predict degradation for effective sampling design. Environ. DNA 5, 403–416 (2023).

- Barnes, M. A. et al. Environmental conditions influence eDNA persistence in aquatic systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 1819–1827 (2014).

- Kessler, E. J., Ash, K. T., Barratt, S. N., Larson, E. R. & Davis, M. A. Radiotelemetry reveals effects of upstream biomass and UV exposure on environmental DNA occupancy and detection for a large freshwater turtle. Environmental DNA 2, 13–23 (2020).

- Valentin, R. E., Kyle, K. E., Allen, M. C., Welbourne, D. J. & Lockwood, J. L. The state, transport, and fate of aboveground terrestrial arthropod eDNA. Environmental DNA 3, 1081–1092 (2021).

- Jo, T. & Yamanaka, H. Fine-tuning the performance of abundance estimation based on environmental DNA ( eDNA ) focusing on eDNA particle size and marker length. Ecol. Evol. 12, (2022).

- Jo, T., Arimoto, M., Murakami, H., Masuda, R. & Minamoto, T. Estimating shedding and decay rates of environmental nuclear DNA with relation to water temperature and biomass. Environmental DNA 2, 140–151 (2020).

- Saito, T. & Doi, H. Degradation modeling of water environmental DNA: Experiments on multiple DNA sources in pond and seawater. Environmental DNA 3, 850–860 (2021).

- Holman, L. E., Chng, Y. & Rius, M. How does eDNA decay affect metabarcoding experiments? Environmental DNA 4, 108–116 (2022).

- Wilder, M. L., Farrell, J. M. & Green, H. C. Estimating eDNA shedding and decay rates for muskellunge in early stages of development. Environmental DNA 5, 251–263 (2023).

- Jo, T. et al. Rapid degradation of longer DNA fragments enables the improved estimation of distribution and biomass using environmental DNA. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 17, e25–e33 (2017).

- Moyer, G. R., Díaz-Ferguson, E., Hill, J. E. & Shea, C. Assessing environmental DNA detection in controlled lentic systems. PLoS One 9, e103767 (2014).

- Rourke, M. L. et al. Environmental DNA (eDNA) as a tool for assessing fish biomass: A review of approaches and future considerations for resource surveys. Environmental DNA 4, 9–33 (2022).

- Li, J. et al. Limited dispersion and quick degradation of environmental DNA in fish ponds inferred by metabarcoding. Environmental DNA 1, 238–250 (2019).

- Jeunen, G.-J. et al. Water stratification in the marine biome restricts vertical environmental DNA (eDNA) signal dispersal. Environmental DNA 2, 99–111 (2020).

- Shogren, A. J. et al. Controls on eDNA movement in streams: Transport, Retention, and Resuspension. Sci. Rep. 7, 5065 (2017).

- Dickie, I. A. et al. Towards robust and repeatable sampling methods in eDNA-based studies. Mol. Ecol. Resour. (2018). [CrossRef]

- Kirtane, A., Kleyer, H. & Deiner, K. Sorting states of environmental DNA: Effects of isolation method and water matrix on the recovery of membrane-bound, dissolved, and adsorbed states of eDNA. Environmental DNA 5, 582–596 (2023).

- Hinlo, R., Gleeson, D., Lintermans, M. & Furlan, E. Methods to maximise recovery of environmental DNA from water samples. PLoS One 12, e0179251 (2017).

- Kumar, G., Eble, J. E. & Gaither, M. R. A practical guide to sample preservation and pre-PCR processing of aquatic environmental DNA. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 20, 29–39 (2020).

- Patin, N. V. & Goodwin, K. D. Capturing marine microbiomes and environmental DNA: A field sampling guide. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1026596 (2022).

- Nagler, M., Podmirseg, S. M., Ascher-Jenull, J., Sint, D. & Traugott, M. Why eDNA fractions need consideration in biomonitoring. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 22, 2458–2470 (2022).

- Barnes, M. A. et al. Environmental conditions influence eDNA particle size distribution in aquatic systems. Environmental DNA 3, 643–653 (2021).

- Peixoto, S., Chaves, C., Velo-Antón, G., Beja, P. & Egeter, B. Species detection from aquatic eDNA: Assessing the importance of capture methods. Environmental DNA 3, 435–448 (2021).

- Sales, N. G., Wangensteen, O. S., Carvalho, D. C. & Mariani, S. Influence of preservation methods, sample medium and sampling time on eDNA recovery in a neotropical river. Environmental DNA 1, (2019).

- Buxton, A. S., Groombridge, J. J. & Griffiths, R. A. Seasonal variation in environmental DNA detection in sediment and water samples. PLoS One 13, e0191737 (2018).

- Bálint, M. et al. Environmental DNA Time Series in Ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 33, 945–957 (2018).

- Klymus, K. E. et al. Reporting the limits of detection and quantification for environmental DNA assays. Environ. DNA 2, 271–282 (2020).

- Pinfield, R. et al. False-negative detections from environmental DNA collected in the presence of large numbers of killer whales (Orcinus orca). Environmental DNA 1, 316–328 (2019).

- Mauvisseau, Q. et al. Influence of accuracy, repeatability and detection probability in the reliability of species-specific eDNA based approaches. Sci. Rep. 9, 580 (2019).

- Bockrath, K. D., Tuttle-Lau, M., Mize, E. L., Ruden, K. V. & Woiak, Z. Direct comparison of eDNA capture and extraction methods through measuring recovery of synthetic DNA cloned into living cells. Environmental DNA 4, 1000–1010 (2022).

- Ely, T., Barber, P. H., Man, L. & Gold, Z. Short-lived detection of an introduced vertebrate eDNA signal in a nearshore rocky reef environment. PLoS One 16, e0245314 (2021).

- Filazzola, A. & Cahill, J. F., Jr. Replication in field ecology: Identifying challenges and proposing solutions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12, 1780–1792 (2021).

- Buxton, A., Matechou, E., Griffin, J., Diana, A. & Griffiths, R. A. Optimising sampling and analysis protocols in environmental DNA studies. Sci. Rep. 11, 11637 (2021).

- Nicholson, A. et al. An analysis of metadata reporting in freshwater environmental DNA research calls for the development of best practice guidelines. Environ. DNA 2, 343–349 (2020).

- Minamoto, T. et al. An illustrated manual for environmental DNA research: Water sampling guidelines and experimental protocols. Environ. DNA 3, 8–13 (2021).

- Hendricks, A. et al. Compact and automated eDNA sampler for in situ monitoring of marine environments. Sci. Rep. 13, 5210 (2023).

- Sabir, I. H., Torgersen, J., Haldorsen, S. & Aleström, P. DNA tracers with information capacity and high detection sensitivity tested in groundwater studies. Hydrogeol. J. 7, 264–272 (1999).

- Foppen, J. W., Orup, C., Adell, R., Poulalion, V. & Uhlenbrook, S. Using multiple artificial DNA tracers in hydrology. Hydrol. Process. 25, 3101–3106 (2011).

- Foppen, J. W. Artificial DNA in hydrology. WIREs Water 10, (2023).

- Zhang, Y. & Huang, T. DNA-Based Tracers for the Characterization of Hydrogeological Systems—Recent Advances and New Frontiers. Water 14, 3545 (2022).

- Matsui, K., Honjo, M. & Kawabata, Z. Estimation of the fate of dissolved DNA in thermally stratified lake water from the stability of exogenous plasmid DNA. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 26, 95–102 (2001).

- Hardwick, S. A. et al. Spliced synthetic genes as internal controls in RNA sequencing experiments. Nat. Methods 13, 792–798 (2016).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).