1. Introduction

The Malaysian government was one of the first countries in Asia to announce the movement control order (MCO) which began on 18 March 2020 as a precautionary measure and a response approach to curb the spread of the COVID-19 epidemic. Among the restrictions implemented through the MCO is the closure of government offices and private premises, except for those related to the country’s main services such as health and safety, telecommunications, retail, finance, and transportation (National Security Council, 2020). Although the MCO approach was able to curb the spread of the virus, the enforcement of restrictions has left a negative impact on the global economy, industry, companies, and micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME). Meanwhile, Hamdan et al. (2021) reported the Global Capital Survey by Ernst and Young (2020) showed that 73 per cent felt a minimal impact. Hamdan et al. (2021) also recorded a Congressional Research Service survey reporting that as of March 2020, the crisis had reduced global economic growth by 0.5 per cent to 1.5 per cent.

For MSMEs, the impact of this pandemic has had a big impact on their business activities. Among the obstacles faced by microentrepreneurs include problems in cash flow due to loss of daily income, operational disruptions, layoffs, and supply chain disruptions (Che Omar et al. 2020) (Fabeil et al. 2020). Furthermore, Bartz and Winkler (2016) emphasize that MSME shows a longer regrowth following the crisis than large companies that grow faster and are more flexible. In addition, the main challenge or obstacle faced by MSMEs is the disruption of business operations where temporary closures during the closure period and some sectors have been closed permanently due to financial problems (Bartik et al. 2020). In addition, Fabeil et al. (2020) also found that small businesses in rural areas experience more significant challenges than enterprises in urban areas and are rapidly developing due to remoteness, especially in terms of infrastructure constraints, labour availability and limited financial reserves. Therefore, the effects of pandemics and challenges are unique and vary to individuals, types of business activities, geographic areas, size and resources (Cassia and Minola 2012) (Lai and Scheele 2018).

Although various efforts and assistance are provided by the government and NGOs, every entrepreneur, especially MSME, has different experiences in facing the COVID-19 epidemic, as well as an uneven level of ability to reduce the impact of the MCO on their business activities. The findings of Cook (2015) show that 75 per cent of MSME businesses without a continuity plan will collapse within three years after a disaster or crisis. However, most previous studies have focused on the concerns of the impact of the crisis alone, and the effectiveness of the mitigation approach to reduce the impact has not been fully explored including the factors that may affect the effectiveness of the mitigation strategy. Therefore, this study aims to explore the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak and MCO on Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM) microfinance MSME entrepreneurs, especially the single mother group and to identify the factors that influence the effectiveness of AIM microfinance programs in dealing with the pandemic crisis.

In dealing with the pandemic and MCO, through a circular with the reference number AIM/JPU/300-02/01(01) dated 24 March 2020, AIM launched an economic stimulus package amounting to RM 682,357,904.00 to help AIM participants, also known as Sahabat AIM, to overcome the challenges of the pandemic and MCO. The economic stimulus package involves (1) the postponement of the collection of weekly repayments or a moratorium involving 373,815 Sahabat AIM, which involves a financial implication of RM 555 million, (2) Authorization to withdraw Compulsory Savings (SW) on a one-off or one-off basis of a maximum of RM 300 to 373,815 Sahabat AIM involving a financial implication of RM 112.5 million, (3) deferment of I-Lestari and I-Usahawan Koop Sahabat installments involving 400 Sahabat AIM involving a sum of RM 300,000, (4) postponement of the Sahabat Ar-Rahnu auction or Islamic mortgage until the end MCO involves 1500 Sahabat AIM with a financial implication of RM 120,000, (5) a Group Fund Loan (PTK) offering involving 10,000 Sahabat AIM with a maximum limit of RM 1000 per borrower, with a financial implication of RM 10 million, (6) distribution of cash donations amounting to RM 250 people to 17,444 Sahabat AIM involving financial implications of RM 4,361,104 channeled through Business Zakat Sahabat Koop RM 621,104, AIM Welfare Assistance Fund RM 2.6 million and AIM Corporate Benefit Fund RM 1.14 million, and (7) the organization of Sahabat AIM Entrepreneurship Workshop 2020 which emphasizes aspects of online business or the digital economy involving 200 Sahabat AIM (AIM, 2020a; 2020b).

Hence, this study shall find answers to the following research questions: (1) What is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO on the empowerment of single mother entrepreneurs among participants in the AIM microfinance program? (2) How effective is AIM's microfinance program when facing the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO? and (3) How does the relationship between the four indicators of empowerment of single mother entrepreneurs - economic, social, digital, and psychological, as well as management and governance factors affect the effectiveness of the AIM microfinance program when facing the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO?

2. Literature review

A crisis can be defined as a situation faced by an individual, group, or organization that results in disruption to management using standard routine procedures (Booth 1993) (Anthony et al. 2019) (Lai 2020) (Ran et al. 2020). From the study, crises are categorized into three types, which are gradual threats, periodic threats, and sudden threats. Regarding the COVID-19 epidemic crisis, it is categorized as a 'sudden threat' that occurs unexpectedly which not only affects health conditions but also causes global economic shock (Booth 1993). A survey by Bartik et al. (2020) found that 5,800 small businesses in America are facing a fragile financial situation, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings of the study found that the median of firms with monthly expenses below $10,000, had cash in hand that lasted for one month, whereas, in pre-pandemic or crisis times, the median for similar firms had cash on hand for less than 15 cash days given the higher level of expenses. This situation reflects MSME spends less during the crisis, and this situation is not good for the firm, and the economy in the long term. In addition, the outbreak also caused negative effects on layoffs and supply chain disruptions. For example, a study by Che Omar et al. (2020) found that respondents were facing difficulties in obtaining raw materials which on average were mostly imported from China and the number of available suppliers was becoming smaller or limited. Meanwhile, Fairlie (2020) provides an analysis of the impact of the pandemic on active small businesses in the United States using national data from April 2020. Findings reveal that the African-American business community experienced a 41 per cent drop. While Latino business owners declined by 32 per cent and Asian business owners decreased by 26 per cent.

Meanwhile, Hamdan et al. (2021) explored the impact of the outbreak during the MCO on MSME entrepreneurs under the AIM microfinance program and the approaches used to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the participants' businesses. This study was conducted using a qualitative approach, in-depth interviews using a semi-structured interview format with six female micro-entrepreneurs. Selection from respondents through a purposive sampling technique by utilising the AIM e-commerce platform known as Bazar Sahabat. The study provides two main themes for impact on micro-entrepreneurs which are financial issues and operational disruptions. As for the mitigation approach, the consensus pattern among respondents is related to adopting new norms, including changing the location of business operations from physical stores to home-based and online platforms. This study has limitations in terms of the generalization of the findings and the focus of the study; however, the researchers believe that the results of this study can be a stepping stone for further research in the future regarding the impact of the pandemic and MCO on microfinance participants. Therefore, future research could further explore using survey analysis on a larger group of respondents to understand the impact and survival mechanisms adopted by them in response to the crisis.

After more than three decades, microfinance has become a key element in economic development strategies around the world, especially in developing and developing countries. In Malaysia, AIM has been launched since 1987 and is a federal government agency that manages microfinance programs to improve the well-being of vulnerable groups. Microfinance facility is a basic component in microfinancing which specifically refers to the provision of loans and credit facilities to the poor and needy. The amount of loans offered is relatively low in most countries and these facilities are developed to channel and meet capital needs and cash movement from surplus units to deficit units. Surplus profits from microfinance will be used as a source of capital for small businesses to increase the income of these poor people, which in turn will help them get out of the cocoon of poverty. Microfinance is also a financial aid to small traders to eradicate poverty and change the standard of family life (Rahman et al. 2018). The use of the concept or theory of empowerment is an idea that is growing now, in the context of advancing the socioeconomics of microfinance program participants (Nazier and Ramadan 2018).

The theory of empowerment includes various dimensions that involve individual changes from the point of view of increasing the will and ability to economic, socio-cultural, legal, political, and psychological (Kaber 2011), and one of them is the process of women's empowerment (Rahman et al. 2018) to build resilience. According to Kaber (2011), women's empowerment is defined as a process in which women obtain resources that can help increase empowerment, thereby improving the well-being of themselves and their families. A person is considered to have empowerment if they successfully achieve psychological control, good social influence and can engage in any decision-making process. In addition, Torri and Martinez (2014) stated that the process of women's empowerment is a process of internal change for individuals who are less powerful in making choices to have the power and ability to do it and the awareness of "meaning, motivation and purpose" in each of their actions. Contemporary studies explain that women's involvement in micro-financing programs has a positive effect on the empowerment and empowerment of this group through several dimensions such as economic, social, legal, and psychological (Addai 2017). Microfinance facilities play a very important role in empowering women's decision-making power in households related to expenses and family planning. It is also able to contribute to women's empowerment in terms of income. In addition, investment in women's empowerment is believed to have a significant impact on economic growth (Sarumathi and Mohan 2011). These studies have shown that the microfinance program has a significant positive effect on the formation and improvement of women's empowerment, including single mother entrepreneurs.

2.1. Economic empowerment

The availability of credit facilities is very important to overcome the financial constraints identified as one of the main causes preventing the growth and sustainability of small and medium enterprises in developing countries (Wellalage and Locke 2017). Therefore, credit facilities play an important role in facilitating the flow of capital which in turn can increase the economic growth of an individual (Mariyono 2019). According to Ferdousi (2015), the policy to stimulate economic growth is necessary to strengthen the financial system, by promoting various financial products and services to produce a positive effect on the savings-investment process and subsequently economic growth. Financial products such as in the form of credit or insurance where these products have been seen to play an important role in increasing financial innovation. Microfinance can also help to increase business in the real sector and stimulate economic growth, lower the unemployment rate through increased labour demand, increase income and lower the poverty rate (Sipahutar et al. 2016). Meanwhile, Fofana et al. (2015) found that borrowers through microfinance on average have higher incomes and higher household asset values than non-borrowers. In addition, microfinance also empowers female borrowers in making household decisions related to mobility, daily expenses, children's schooling, and health expenses (Al-Shami et al. 2017). In a case study on the impact of microfinance on women's empowerment in Sri Lanka, the researcher examined the impact of microfinance on women's poverty and socioeconomic vulnerability as well as the ability to form social capital through group-based microloans. The analysis found that if the woman borrows and acts as a credit channel, it has a positive and significant effect on her ability from a household decision-making point of view (Herath et al. 2015). Next, Al-Shami et al. (2017) studied the effect of productive loans provided by AIM on the welfare and empowerment of women's households. A cross-sectional study was used through the distribution of questionnaires to 495 old and new borrowers. It was found that microfinance facilities have a significant positive effect on the borrower's household income and personal asset ownership. In conclusion, the benefits of microfinance can increase the empowerment of women in making household decisions.

2.2. Social empowerment

The dimension of social empowerment is defined as the process of freedom, self-confidence, and action to change social relationships (Casey et al. 2010). A study by Ab-Rahim et al. (2018) shows that microfinance has a positive effect on women, further offering future studies with recommendations to examine aspects of women's empowerment from an economic and social point of view. Sarumathi and Mohan (2011) used psychological, social, and economic indicators in their study to identify the role of microfinancing in women's empowerment in Pondicherry, India. The findings of the study reveal that microfinance helps increase women's empowerment from a social rather than an economic point of view. In addition, a study in Uganda has proven that women can manage their finances as well as gain greater mobility (Van Rooyen et al. 2012). Some past studies have used various indicators to measure the level of social empowerment. Among them self-esteem (Hansen 2015); self-confidence (Kim et al. 2007); self-efficacy (Kato and Kratzer 2013) (Herath et al. 2015); decision-making (Banerjee et al. 2015) and mobility (Ahmad et al. 2019).

2.3. Psychological empowerment

The psychological aspect is also one of the important factors that contribute to the empowerment of women entrepreneurs in the microfinance program. This psychological aspect can be categorized into self-confidence, self-skills, educational awareness, environment and harmony or well-being of self and family and refers to a person's thinking and behaviour patterns (Ahmad et al. 2019). Sarumathi and Mohan (2011) also used psychological indicators in their study to identify the role of microfinancing in women's empowerment in Pondicherry, India. The findings of the study reveal that microfinancing helps increase women's empowerment from a psychological point of view rather than an economic one. This study is also supported by Henry (2011). He explained that empowerment can only be realized if an individual has a psychological sense of self-control. The level and ability to control oneself are very important in helping women decide or deal with an unexpected environmental situation. Women's involvement in microfinance also contributes to improving the well-being of life. When compared to the ability to access financing formally through banking and financial institutions, this microfinance facility is more accessible in terms of eligibility and application. It is expected to be able to improve the psychological level of women (Salia et al. 2018) and generate additional income to be used to cover daily needs and able to improve the quality and well-being of life (Rokhim et al. 2016). Salia et al. (2018) and Fancina and Joseph (2013) explained in their research findings that microfinance facilities can have a positive effect on women's involvement from a psychological point of view such as increased levels of self-confidence, improvements in life happiness, self-esteem and self-skills, the courage to express opinions or opinion, become more courageous and independent. Batool et al. (2016) reported in a study that 500 women between the ages of 21 and 49 also found that women's empowerment, specifically referring to psychology, has a positive relationship with self-confidence. According to Ab-Rahim et al. (2018), psychology can be expressed in three forms consisting of (1) awareness, knowledge, social power, ability, participation in society and access to financial resources without any form of social discrimination, (2) political power which means freedom and involvement in the process making decisions, and (3) the last form of power is psychological power that takes into account the potential of individuals and their judgments that influence political and social power.

2.4. Digital empowerment

In addition to educational issues, Hamdan et al. (2021) also dive into the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and the MCO against micro and small entrepreneurs. Specifically, for the operational aspect, the main challenge faced by respondents is using digital platforms to continue business activities such as promotion and sales. The study also explains the need for regulators and microfinance scheme operators to conduct more training to build the capacity and skills of respondents to master the digital platform and in preparation for future shocks. According to Gong (2020), although the national mobile broadband penetration rate per 100 people is about 120% in 2019, the fixed broadband penetration rate—which provides faster and more reliable connections—is only about 8% for every 100 people. Other infrastructure weaknesses, such as the lack of fibre optic networks and slow internet speeds have affected connectivity in the country. Based on Kamaruzuki (2020), the issue of internet speed quality in Malaysia started before the presence of the COVID-19 epidemic. In 2018, Malaysia's 4G network download speed ranked 20th lowest in the world. A report from Opensignal reported that in 2019, data download speeds via mobile broadband between telecommunications companies were in the range of 5.4 Mbps to 17.7 Mbps only. Although some telecommunications companies market broadband speeds of up to 100 Mbps with 4G networks, such promotions are good news from the looks of it. The fact is that speed is not enjoyed by most users. Although almost 90% of mobile broadband users in Malaysia can access the 4G network, the quality is still low. This is due to the weakness of the infrastructure when only 40% of the substation towers use optical fibre. Meanwhile, Lythreatis et al. (2021) conducted a systematic review and synthesis of 50 articles from 24 countries about the digital divide. The study consolidates the existence of three levels of the digital divide covering Level 1: access to devices and internet connection, Level 2: digital competence, skills, and literacy, and Level 3: the ability to use digital competence for life mobilization. The study also expressed concern about the potential for a new digital divide in terms of algorithmic awareness and the inequality of data obtained stemming from the type of internet access. The study also classified the factors affecting the digital divide into nine themes, namely socio-demographic, socio-economic, personal elements, social support, types of technology, digital skills, rights, infrastructure, and large-scale phases of life.

2.5. Management and governance of microfinance programs

Ahmad et al. (2019) have assessed the impact of management and monitoring on the effectiveness of the Hijrah microfinance program offered by the Selangor state government. The study has used nine indicators to measure management and monitoring variables. The relevant indicators are (1) Hijrah officers have provided good service without discrimination, (2) the effectiveness of the training provided by Hijrah Selangor, (3) satisfaction with the service provided, (4) good feedback from Hijrah officers, ( 5) confident in the experience possessed by Hijrah officers, (6) confident that Hijrah officers are given sufficient training in understanding the needs of aid recipients, (7) easy complaint channels, (8) swift action when needed and (9) frequency of monitoring by Hijrah officials. The analysis of the study found that the indicator with the highest mean score was the good treatment of the officers without discrimination. Overall, the study found that the management level of Hijrah program monitoring in the state of Selangor is at a moderate level. In addition, Koh et al. (2021) also examined aspects of training conducted by AIM for microfinance participants in the Federal Territories of Kuala Lumpur, Penang, and Johor. Training indicators are measured based on a study by Maru and Chemjor (2013). The study found that the training managed by AIM has succeeded in significantly improving the socio-economic welfare of the participants. The analysis also found that managed training will be able to improve the socioeconomics of microfinance participants indirectly significantly, with the presence of increased income. The management aspect of microfinance participant training and its importance to the effectiveness of the microfinance program was also confirmed by previous researchers such as Al-Mamun et al. (2018), Al-Shami et al. (2014), Paul et al. (2013), Maru and Chemjor (2013), Hamdan and Husin (2012), Saad and Duasa (2010).

2.6. Effectiveness of microfinance programs

Ahmad et al. (2019) also examined the effectiveness of the microfinance program managed by Hijrah - a Selangor state government agency. The study found that the level of effectiveness of the program is high. To measure the level of effectiveness, the researchers have used five indicators consisting of (1) respondents felt that the Hijrah Selangor microfinance program should be participated by all single mothers, (2) the Hijrah Selangor microfinance program helps individuals in eradicating poverty, (3) this program effective in increasing income (4) this program can change lives, and (5) this program is successful in addressing the issue of poverty among single mothers. Meanwhile, Koh et al. (2021) studied the factors that influence the effectiveness of the AIM microfinance program in helping to address the issue of urban poverty. In this study, effectiveness is measured through two indicators - participant income and participant welfare. Five indicators were used to measure the welfare of the participants adapted from the study of Omoro and Omwange (2013), while the income of the participants was measured through lime indicators inspired by the study of Durrani et al. (2011).

3. Research Model

3.1. Research design and research framework

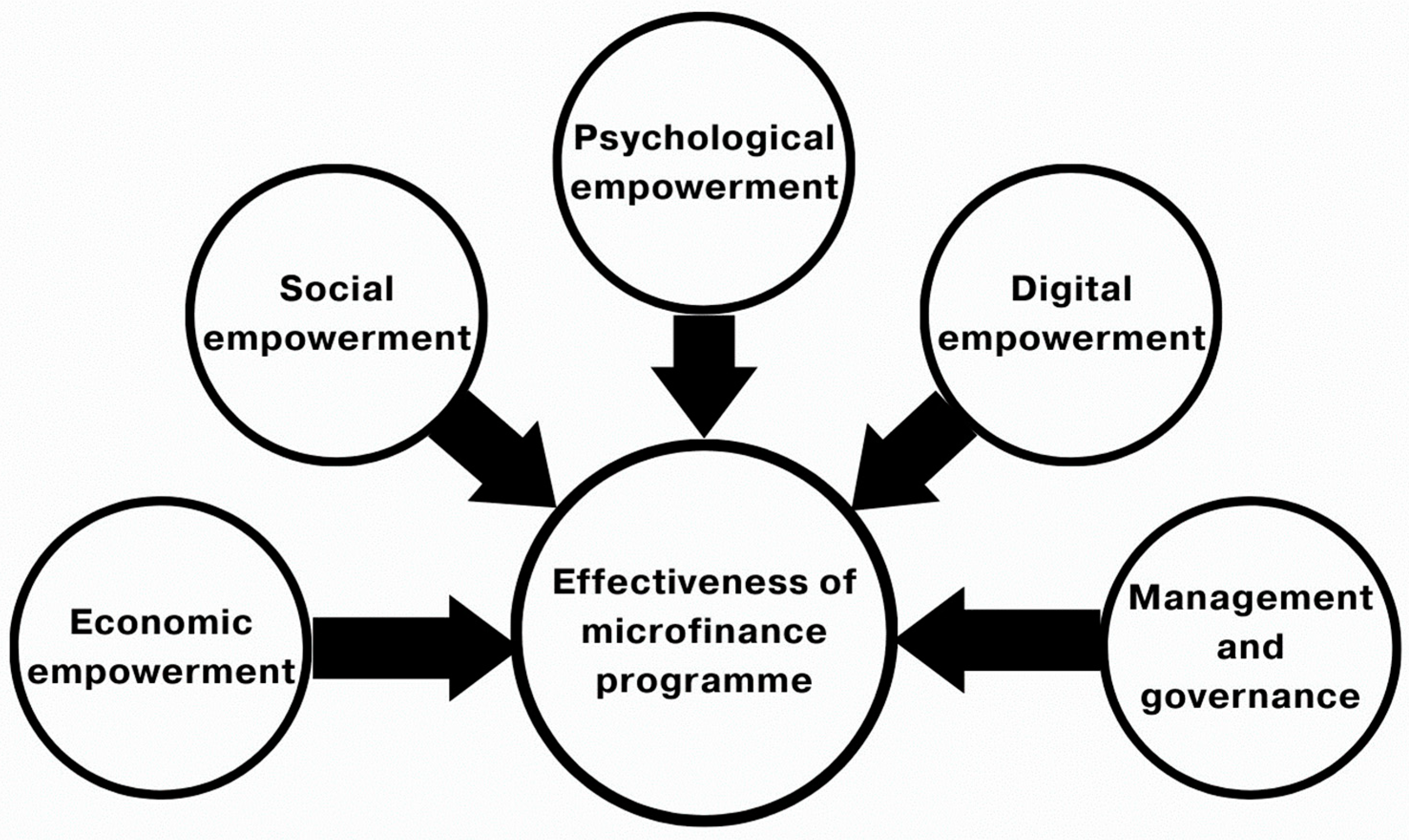

This study decided to adopt a positivist paradigm and deployed a quantitative method through questionnaire distribution. This is consistent with the methodology of previous studies of a similar nature. To facilitate the process of this study, a research framework was formed based on the results of previous studies related to factors that contribute to the effectiveness of microfinance programs (Al-Shami et. al. 2014), as well as considering the background of crises such as epidemics and movement restriction orders (Mohammad et al. 2022) (Hamdan et al. 2021). The focus of this study is to examine the relationship between indicators of empowerment of single mother entrepreneurs participating in microfinance and the level of effectiveness of AIM's microfinance programs when dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic and the MCO. The framework of the study is as follows:

Figure 1.

Antecedents of Program Effectiveness During Pandemic.

Figure 1.

Antecedents of Program Effectiveness During Pandemic.

3.2. Variable measurement

An independent variable (IV) refers to a variable that can be manipulated, and changed, and measures the effect of manipulation on other variables. Based on previous studies, to measure the empowerment of single mother entrepreneurs of microfinance participants, this study has used four (4) main indicators, namely economic, social, digital, and psychological. These four empowerment indicators are expected to impact and influence the effectiveness of the AIM microfinance program during the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO. For this study, the dependent variable (DV) is the effectiveness of the AIM microfinance program during the pandemic and MCO. The variables for this study are summarized in

Table 1.

3.3. Population and sample selection

The population refers to a group of individuals who want to be studied, namely single mother entrepreneurs who participate in the AIM microfinance scheme in the state of Selangor, the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur, and the Federal Territory of Labuan. The single mother in question is a woman who (1) has had her husband die, (2) divorced, or (3) a woman whose husband is sick and unable to earn a living. Based on records and data obtained from the Research and Innovation Unit (UPI), Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia, the population of single mother entrepreneurs participating in the AIM microfinance scheme who meet the respondent criteria is 1677 including 11 branches including Ampang, Cheras, Kepong, Puchong, Sepang, Barat Selangor Sea, Hulu Selangor, Kuala Selangor, Shah Alam, Gombak, and Labuan. The population in question has also been verified and cleared through review by the Research and Innovation Unit (UPI), Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia and was assisted by branch managers, assistant branch managers and supervisors in the area involved. The considerations and criteria for verification or population cleansing include elements such as participants (single mother entrepreneurs) are active participants, as well as personal data especially marital status, address and phone number have been updated.

Table 2 depicts the population and expected size of the sample of the study.

This study uses a quantitative method, where two stages of sampling are used. The first stage is a stratified sampling involving three areas - the state of Selangor, the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur and the Federal Territory of Labuan which contains 11 branches. The second stage is random sampling. Based on UPI records and verification by the branch and supervisor, the total population of respondents is 1677, so using the recommendations of Krejcie and Morgan (1970), the number of samples required is 314. Next, the total population is stratified according to 11 branches, and the percentage of each branch is obtained. By using the same percentage, the total sample for each stratum is also obtained. Next, in the second sampling phase, respondents were randomly invited to respond to the survey form that was distributed.

3.4. Research instruments

To obtain the necessary information, this research instrument uses quantitative methods through questionnaires and interviews to collect data. Next, to increase the validity of the indicators that will be used in this study, the draft survey form was first submitted to the management of the Research and Innovation Unit (UPI), Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia. The draft was also extended to managers, assistant managers and selected supervisors identified by UPI. Feedback, views, and remarks from both parties were considered in the design of the final survey form, before being distributed to respondents. In addition, the research team also sought feedback from experts who had been involved in the field of entrepreneurship and management of micro, small and medium enterprises to further refine the indicators found in the survey form.

The design process of this structured questionnaire item is the result of a survey of previous studies. This questionnaire was used to collect primary data from a sample of single mother entrepreneurs of the AIM microfinance program and is divided into 9 sections, namely (A) Demographic aspects (respondent background), (B) the effectiveness of the AIM microfinance program and initiatives during the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO, (C) AIM microfinance program management and governance factors, (D) Psychological Empowerment, (E) Economic Empowerment, (F) Social Empowerment, (G) Digital Empowerment, (H) Factors choosing the AIM microfinance program during the Covid pandemic -19 and MCO and (I) open questions that gather general views as well as suggestions or feedback from respondents regarding the issue being studied.

Part A touches on the respondent's demographics including aspects of household monthly income, respondent's marital status, family type, total household dependents, type of residence, residence status, and business location. Part B contains 11 indicators related to the level of effectiveness of AIM microfinance programs and initiatives during the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO. Part C contains 13 indicators about the management and governance aspects of the AIM microfinance program. Part D contains 13 indicators of psychological empowerment. Next, Section E contains 12 indicators of economic empowerment. There are 11 indicators of social empowerment in Section F. This is followed by 11 indicators of digital empowerment in Section G. Next, in Section H there are 10 indicators that are factors in the selection of respondents to the AIM microfinance program during the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO. There is only one open question in Part I to allow respondents to give feedback freely about the issue or topic being studied. For Sections B, C, D, E, F, and G, each indicator is measured using four Likert scales. The use of four Likert scales has been used by researchers such as Ahmad et al. (2019) and Riduwan (2012). In fact, according to Garland (1991), the use of even response categories in the Likert scale eliminates the tendency of respondents to show a midpoint response that depicts a neutral response or implies a non-decision to the surveyed item. The four Likert scales used in this study are represented by 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, and 4 = strongly agree.

The average value (mean) was used to analyze the data. The mean score obtained for each indicator is multiplied by a weighting of 2.5, to obtain an average value score (mean) based on a base score of 10. A weighting with a value of 2.5 is used considering that this study uses a four-point Likert scale i.e., 2.5 x 4 = 10. Next, the average mean score for each domain is obtained by adding the mean score for all indicators with the total number of indicators in the domain in question. For example, there are 13 indicators for psychological empowerment, because the mean score of the psychological empowerment domain will be obtained by summing up the mean scores of all indicators of empowerment and dividing by 13. Therefore, the analysis is performed based on the mean score table, which is categorized into four mean interpretations, which are less relevant, low, moderate, and high based on a four-point Likert scale adapted from Ahmad et al. (2019) and Riduwan (2012) as in the following

Table 3.

3.5. Data collection procedure

As explained in the previous section, data collection was done based on a questionnaire. Both primary and secondary data sources will be used to complete the study. Primary data was obtained through a questionnaire distributed through the WhatsApp application and a Google Form link to single mother entrepreneurs participating in AIM microfinance as respondents, while secondary data was obtained from various academic reference sources, journals, articles, documents, newspaper reports and other relevant printed sources. Meanwhile, the main information of single mothers as respondents such as full name, identity card number, residential address, and telephone number, was requested and obtained from the Research and Innovation Unit (UPI) of AIM. For verifying the information of single mothers whether active or inactive, the research team has requested assistance from each Branch Manager and Assistant Branch Manager as well as supervisors in the three states involved - Selangor, the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur, and the Federal Territory of Labuan.

For collecting information and research data, the list of respondents that have been verified by UPI and the branch office was submitted to the research team to form a WhatsApp group based on the branches. A total of 11 WhatsApp groups were created covering Ampang, Cheras, Kepong, Puchong, Sepang, Northwest Selangor, Hulu Selangor, Kuala Selangor, Shah Alam, Gombak, and Labuan. Each member of the research team will be placed in a WhatsApp group of two branches to distribute and get feedback on the questionnaire. The relevant research team members will also be responsible for sending reminders from time to time to improve and speed up feedback. For respondents who are less proficient in using Google Forms, members of the research team will help through telephone interviews based on the questions on the questionnaire.

3.6. Data analysis techniques

Data analysis techniques are a method to process and present data and statistical procedures so that they are easy to understand and provide solutions to research objectives. All data obtained will be totalled and analyzed with the help of Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (SPSS 23). Data analysis is done through two (2) ways which are descriptive analysis and statistical analysis. Descriptive analysis will summarize the data numerically and be presented using tables, graphs, or diagrams. While statistical analysis aims to interpret and produce conclusions for a situation that occurs to the population and sample. These tables will contain items, scores, frequency percentages and mean obtained from the responses of the study respondents. The data of this study will be analyzed using statistical methods such as correlation coefficient and multiple linear regression. The empirical model used in this study is as follows

In this empirical model, the dependent variable is Microfinance Program Effectiveness or for short (KPM). The independent variable consists of four indicators of empowerment of microfinance single mother entrepreneurs including Economic Empowerment (KE), Social Empowerment (KS), Digital Empowerment (KD), and Psychological Empowerment (KP). While FPT is the management and governance factor of AIM, while ε is the error term.

4. Results and discussion

This section discusses in detail the results of the research conducted. Analysis and interpretation are presented to answer the underlying research questions. The results of these findings are divided into three parts, which are the analysis of demographic information of the respondents, descriptive analysis, and empirical analysis. This study has received 422 responses.

4.1. Respondents profile

Table 4 describes the profile of the study respondents based on selected socio-demographic elements including business location, monthly household income, total dependents, respondent status, residential status, residential type, and family status. In terms of business location, most respondents are in the state of Selangor. For the state of Selangor, the existing branches include Sepang, Northwest Selangor, Hulu Selangor, Kuala Selangor, Shah Alam, and Gombak. The total number of respondents who do business in the state of Selangor is 301 or 71.3 per cent, followed by the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur with 99 respondents or 23.5 per cent. Branches in the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur consist of Ampang, Cheras, Kepong and Puchong. While respondents from the Federal Territory of Labuan are 13 or 3.1 per cent and there is only one branch i.e., Labuan in the region concerned. There are 9 respondents or 2.1 per cent who do business in the Federal Territory of Putrajaya. However, there is currently no branch operating in the federal government's administrative centre. Based on monthly household income, most respondents are from the B40 group or in the income range of RM 4,849 and below. The total number of respondents in this group is 379 or 89.9 per cent. The remaining 10.1 per cent consisted of respondents with monthly household incomes in the M40 and T20 groups, respectively covering 37 respondents or 8.7 per cent and 6 respondents or 1.4 per cent. This situation reflects the success of the microfinance program's accessibility to the right target group, especially the B40 group, but still offers equity to the single mother entrepreneur group from M40 and T20 who are capable.

Continuing from the aspect of monthly household income from the B40 group, there are 210 respondents or 49.8 per cent from the B1 group with a household income range of less than RM 2,500 per month, 105 respondents or 24.9 per cent from the B2 group with a household income range between RM 2,501 to RM 3,169 per month, 40 respondents or 9.5 per cent from the B3 group with a household income range of RM 3,170 to RM 3,969 per month, and 24 respondents or 5.7 per cent from the B4 group with a household income range between RM 3,970 to RM 4,849 per month. For the aspect of household dependents, most respondents from single mother entrepreneurs participating in AIM microfinance have dependents between 1 and 4 people covering 303 respondents or 71.8 per cent, followed by the group of household dependents of more than 10 people totaling 77 respondents or 18.2 per cent. These preliminary findings provide an overview of the challenging situation that some microfinance participants must endure to continue their survival and business during the spread of the COVID-19 epidemic and movement restrictions. From the point of view of the respondent's status, 230 or 54.5 experienced divorce. While 133 respondents or 31.5 per cent lost their partner due to death. Next, there are 59 respondents or 14 per cent who took over the responsibility as the head of the family to find the cause of the family's economy since the spouse has become ill, lost the ability to work or is sick.

Touching on the residential aspect, there is the largest group of respondents who still rent and share, respectively 221 or 52.4 per cent and 40 or 9.5 per cent. This situation also illustrates that more than half of the respondents do not yet have their residential assets because they still need to rent or board. There are 117 respondents or 27.7 per cent who own their residence while 12 respondents or 2.8 per cent own a residence jointly (joint ownership), and another 32 respondents or 7.6 per cent own a residence through inheritance. Regarding the type of residence, 121 respondents live in high-rise residences such as flats or 28.7 per cent, 114 respondents live in rural residences or 27 per cent, 40 per cent or 9.5 per cent occupy the People's Housing Project (PPR), and 9 respondents or 2.1 per cent participate in the Poor People's Housing Project (PPRT).

The last respondent's demographic aspect that was studied was the type of family. There are 215 respondents or 50.9 per cent, are single-parent families, and 162 respondents or 38.4 per cent are nucleus families. There are also a total of 14 respondents or 3.3 per cent from extended families, 23 respondents or 5.5 per cent from co-habitation families and mixed families and dyads respectively 6 respondents or 1.4 per cent and 2 respondents or 0.5 per cent. Status of the family living in the current residence. For further explanation, the nuclear family is a family consisting of a father, mother, and children only; A single-parent family is a family that has either a mother or father and a child. This may be due to divorce or even death; A mixed family is a family consisting of a father, wife, and children. However, this family is known as a mixed family if the father is married to 2 or more mothers; a dyad family is a family that only consists of a father and mother and does not have children; An extended family is a family consisting of several generations, for example grandparents, relatives and cousins also live together; A co-habitation family is a family that is not married but lives together.

4.2. Descriptive analysis

Table 5 shows a descriptive analysis of 12 indicators of economic empowerment, based on the responses of single mother entrepreneurs participating in AIM micro

finance when faced with the situation of the COVID-19 pandemic and the MCO. The highest indicator of economic empowerment with a mean score of 8.619 is 'During the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO, I was able to pay back consistently as set by the AIM microfinance scheme'. This finding is very encouraging, even though AIM has provided a program to delay the repayment of financing or loans or called a moratorium. The second highest indicator of economic empowerment with a mean score of 8.309 is 'During the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO, my household income was able to survive by using the AIM microfinance scheme'. The indicator of economic empowerment with the third highest mean score is 8.294 for 'During the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO, my business can still provide for contingency expenses by using the AIM microfinance scheme'. With that, the average mean score of the economic empowerment domain is 7.649 at a moderate level, making the empowerment domain the fifth empowerment factor in terms of order. The Cronbach Alpha for the economic empowerment indicator is 0.910, exceeding a reading of 0.70; as suggested by Nunally and Bernstein (1994); thus, indicating the reliable measurement.

Table 6 also shows a descriptive analysis of social empowerment. There are 11 indicators for social empowerment. The social empowerment indicator with the highest minimum score of 8.738 is 'During the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO, I am still actively communicating online rather than face to face'. The social empowerment indicator with the second highest minimum score of 8.430 is 'In general, during the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO, my social welfare was good'. Then the social empowerment indicator with the third highest min score is 'Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO, I am still active in contact with other AIM microfinance participants', with a min score of 8.324. Thus, the minimum score for the social empowerment domain is 8.903 or at a high level, making this domain the empowerment factor at the top of the ranking. The Cronbach Alpha of the social empowerment domain is 0.925.

Table 7 shows the findings of the descriptive analysis of the digital empowerment factor which consists of 11 indicators. The highest mean score is 8.572 for the indicator 'During the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO, I feel the need for more digital skills training'. Next with a mean score of 8.531 for the indicator 'During the COVID-19 pandemic and the movement control order, I have access to the internet'. The third highest indicator with a mean score of 8.424 is 'During the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO, I have a gadget or digital device to access the internet'. This situation illustrates that respondents have access to the internet and devices or gadgets to follow the digital experience during the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO; however, respondents expressed the need to acquire more digital skills to reap optimal benefits in a digital economy. The overall mean score for the digital empowerment domain is 8.208, making the domain the second factor in the sequence after social empowerment. The Cronbach Alpha for the digital empowerment domain is 0.930.

Table 8 shows the results of the descriptive analysis for the indicators of psychological empowerment which have 13 indicators. The highest indicator with a mean score of 8.602 is 'Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO, I always want to succeed in life'. Next is the indicator 'Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO, I always feel grateful for the life I've lived' with a mean score of 8.584. Meanwhile, the mean score of 8.459 is for the indicator 'I am confident of using my skills throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO'. Hence, the mean score for the psychological empowerment domain is 8.069 or moderate level and ranks fourth. The Cronbach Alpha of the psychological empowerment domain is 0.945.

Next,

Table 9 shows the results of the descriptive analysis for 13 indicators of microfinance program management and governance factors during the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO. The highest mean score indicator is 8.999 for the 'AIM microfinance payment delay incentive to take advantage of business continuity during the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO'. Next, the indicator with a mean score of 8.661 for 'In general, throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO, the management and monitoring of the microfinance program by AIM is good'. The third indicator with a mean score of 8.608 is 'AIM microfinance financing rescheduling incentive to take advantage of business cash flow during the COVID-19 MCO pandemic'. The mean score for the management and governance domain is 8.073 or at moderate level, making the domain the third factor that is expected to influence the effectiveness of microfinance programs and initiatives in helping single mother entrepreneurs overcome the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and movement restriction orders. The Cronbach Alpha value of the domain is 0.928.

Meanwhile,

Table 10 reflects the results of a descriptive analysis of the effectiveness of the AIM microfinance program during the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO, especially in helping single mother entrepreneurs who are also participants in the program. A total of 11 indicators have been evaluated. The highest mean score was 8.555 for the 'Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM) microfinance program is effective in helping businesses survive during the COVID-19 pandemic and movement control order (MCO)'. This was followed by the indicator 'In general, AIM's microfinance programs and services effectively eased the burden during the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO' with a mean score of 8.217. The next indicator is 'AIM's microfinance program is effective in increasing my business income throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO'. The mean score of the AIM microfinance program effectiveness domain is 8.054 or at a moderate level.

4.3. Empirical assessment

Table 11 shows the results of the correlation analysis between dependent variables and independent variables as well as the relationship between independent variables and other independent variables. according to Guildford (1973), the correlation or relationship between one variable and another variable can be classified as weak when the r value or correlation coefficient is between 0.20 and 0.40, at a moderate level between 0.40 and 0.70, at a high level between 0.70 and 0.90, and so on at a high level when the value of r exceeds 0.90. Meanwhile, if the value of r is less than 0.20 it means that the relationship between one variable and another variable can be ignored.

Based on the results of the correlation analysis, it was found that the dependent variable - the effectiveness of the microfinance program (KPM) has a high correlation (r = 0.714) with the management and governance factor (FPT) and a moderate correlation with psychological empowerment (r = 0.490), economic empowerment (r = 0.571), social empowerment (r = 0.418), and digital empowerment (r = 0.436); even all these correlations are significant at the p = 0.01 level. The analysis also shows that the correlation between the independent variable and other independent variables is also significant at the p = 0.01 level; however, at varying degrees of correlation. For example, the correlation between social empowerment is high with economic empowerment (r = 0.843). While the correlation between digital empowerment and management and governance factors is at a moderate level (r = 0.470).

Table 12 reports the results of linear regression analysis on the relationship between the effectiveness of the microfinance program and the indicators of empowerment of single mother entrepreneurs participating in the AIM microfinance from an economic, social, digital, and psychological perspective as well as management and management aspects. Multiple linear regression analysis shows that the two factors of empowerment of single mother entrepreneurs participating in AIM microfinance – economic and digital are positive and significant at the respective levels of 1% and 5%. Meanwhile, the social empowerment factor is negative and significant at the 1% level. The psychological empowerment coefficient was found to be positive but not significant. Meanwhile, the management and management factors are positive and significant at the 1% level. Thus, economic empowerment indicators, digital empowerment indicators and aspects of management and management have a positive and significant relationship to the effectiveness of the AIM microfinance program when dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO. Meanwhile, the social empowerment indicator has a negative and significant relationship to the effectiveness of the AIM microfinance program during a crisis. Another indicator of psychological empowerment was found to be insignificant in influencing the effectiveness of the program regarding helping single mother entrepreneurs navigate challenging situations such as the transmission of the COVID-19 outbreak and orders to restrict movement. The findings of the relationship between single mother entrepreneurs' empowerment indicators and the effectiveness of AIM's microfinance programs and initiatives differ from earlier studies such as Sarumathi & Mohan (2011) and Ahmad et al. (2019) who found a positive and significant relationship between psychological and social empowerment indicators on the effectiveness of microfinance programs. The research team believes that this difference is influenced by the situation experienced by the respondents in each of the studies, moreover, this study evaluates the views of the respondents on the effectiveness of the microfinance program during the spread of the COVID-19 epidemic and the movement restrictions order implemented by the government to curb the spread.

5. Conclusion

This sub-section deliberates the achievement of research objectives, managerial and practical implications, limitations, suggestions for future studies, and a summary of the current study.

5.1. Achievement of research objectives

5.1.1. Objective 1: To identify the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO on the empowerment aspect of single mother entrepreneurs in the AIM microfinance program.

There are four indicators of the empowerment of single mother entrepreneurs participating in the AIM microfinance which were studied as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO covering economic, social, digital and psychology. The results of the study rather than descriptive analysis found that social empowerment indicators with a score of 8.903 were the most important indicators of empowerment. Then there is the digital empowerment indicator with a score of 8.208, the psychological empowerment indicator 7.649 and the economic empowerment indicator 7.649. These four empowerment indicators are at a moderate level.

5.1.2. Objective 2: To assess the effectiveness of the AIM microfinance program in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO.

The results of the study rather than descriptive analysis found that the effectiveness of the AIM microfinance program in the face of the COVID-19 and MCO pandemics was at a modest level with a score of 8.054. In addition, this study also assesses the relationship between management factors and management of the AIM microfinance program on the effectiveness of the relevant program. Descriptive analysis found that the score for the management and administration elements was 8.073 which was also at a moderate level.

5.1.3. Objective 3: To analyze the relationship between the empowerment of single mother entrepreneurs based on four indicators of empowerment which are economic, social, digital, and psychological as well as management and governance factors on the effectiveness of the AIM microfinance program in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO.

Research findings based on linear regression analysis regarding the relationship of empowerment of single mother entrepreneurs measured through four indicators - economic, social, digital, and psychological show that indicators of economic and digital empowerment have positively or directly and significantly influenced the effectiveness of AIM microfinance programs and initiatives during the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO. In addition, the regression analysis also found that management and governance factors are also positively or directly and significantly influencing the level of effectiveness. The findings imply that if the level of economic and digital empowerment of single mother entrepreneurs increases, in addition to more robust management factors, then the situation will contribute positively and significantly to the effectiveness of AIM's microfinance program in facing periods of crisis or shock. However, social empowerment indicators were found to have a negative and significant relationship with the effectiveness of AIM's microfinance programs and initiatives during the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO period. Furthermore, the indicator of psychological empowerment was found to be insignificant in influencing the relationship to the level of effectiveness of the AIM microfinance program.

5.2. Managerial and practical implications

Several policy recommendations are highlighted to increase the capacity and effectiveness of the microfinance scheme. These recommendations aim to better prepare the target group to face future shocks or crises.

5.2.1. Management and governance of the microfinance program

A database that is comprehensive, complete, updated and networked with relevant ministries, agencies or departments should be worked on so that the delivery of financial and non-financial assistance can be done more effectively and systematically and targeted in nature. The characteristics of such a database will enable the implementation of more effective and systematic monitoring, making it easier for interested parties to access information accurately and subsequently be able to channel the necessary support more quickly, thoroughly, and intelligently.

5.2.2. Economic empowerment

Continuous awareness campaigns to create awareness among microfinance participants that they should not rely too much on borrowing practices. A loan that cannot be managed well, will eventually have a bad effect on the borrower. This matter will be strengthened with a series of training, business skills and guidance, market research, financial administration management and financial literacy that can have a great impact on improving living standards, the process of empowerment especially for single mother entrepreneurs and the economic development of the state and the country. In addition, the implementation of targeted aid initiatives for microfinance participants should be strengthened. This targeted assistance method allows microfinance agencies to channel financial and non-financial assistance based on the specific needs or specific challenges faced by the participants. Based on the principle of 'the right medicine, for the specific disease', this approach allows the participants to overcome the challenges they face more thoroughly and quickly. This approach increases economic and cost-effectiveness.

5.2.3. Digital empowerment

Carry out continuous and structured training and digital skills improvement programs, especially with Malaysia stepping into the digital economy era. Participants should be widely exposed to digital marketing techniques, digital payments, and other online transactions. In addition, continuous efforts are needed to increase accessibility or access to the internet and gadgets among single mother entrepreneurs.

5.2.4. Social Empowerment

Strengthen multi-directional cooperation, across agencies and multi-stakeholders to increase the social empowerment efforts of single mother entrepreneurs. A transparent and comprehensive multilateral and multi-agency cooperation framework is needed to avoid duplication of functions, waste of resources, and leakage of funds. In addition, multi-stakeholder collaboration is important to establish a 'mentoring' system and 'networking' program for microfinance participants, especially for single mother entrepreneurs. To ensure that the concerned group continues to benefit for a long time, the mentoring system and networking program are very important because they can have a great impact on the improvement of living standards, the empowerment process, and the development of the country's economy.

5.2.5. Psychological empowerment

Aspects of mental and psychological well-being should be emphasized to ensure that single mother entrepreneurs participating in microfinance programmes have a good level of mental health. The continuous guidance of certified counsellors and easily accessible health experts should be considered since single mother entrepreneurs are often faced with various economic, social, and family management challenges as well as self-development.

5.3. Limitations of study

Although this study has achieved the research objectives outlined, there are at least two limitations or constraints in this study. First, this study focuses on respondents who are in urban areas of three states only - Selangor, Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur, Federal Territory of Labuan which covers eleven branches - Ampang, Cheras, Kepong, Puchong, Sepang, West Selangor, Hulu Selangor, Kuala Selangor, Shah Alam, Gombak, and Labuan. Second, the response of this study focuses on a group of vulnerable communities consisting of single-mother entrepreneurs among microfinance participants.

5.4. Suggestion for future research

Based on the research that has been done and considering the views of the respondents, the researcher would like to put forward some suggestions that can be considered for implementation in the future. Among them (1) the study in the future can be expanded to involve respondents in other states; because involves the analysis of more branches. Next, a comparative analysis regarding the effectiveness of microfinance programs or initiatives during the crisis can be refined between states, branches, and localities such as urban-rural-suburban; (2) future studies can also be expanded by involving more respondents from other vulnerable communities among microfinance participants such as disabled entrepreneurs, communities in public housing projects, and youth from poor urban and rural areas; and (3) future studies can also consider a longitudinal study approach to enable the assessment of the empowerment factors of microfinance participants and the effectiveness of the AIM microfinance program for a longer period compared to cross-sectional studies.

5.5. Summary

Overall, this study has identified the effectiveness of AIM's microfinance programs and initiatives during the COVID-19 pandemic and MCO from the perspective of single mother entrepreneurs who are participants in the program. In addition, the study has been able to identify the relationship between the four empowerment indicators of single mother entrepreneurs participating in the microfinance program - economic, social, digital, and psychological as well as the program's management and governance factors. The findings of the study have been able to give a clear picture to all interested parties, especially Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia as well as the government in general to promote single mother entrepreneurs participating in the microfinance program from a socioeconomic aspect. Generally, change, reform and progress in a society starts with women because this group is the cornerstone of a family institution. To achieve more empowerment, the microfinance program implemented needs to be solidly supported by several other aspects such as training, skills, and educational opportunities for single mothers, especially to create opportunities to obtain digital life-long learning. Various development activities, technical and vocational training, as well as targeted comprehensive financial and non-financial aid initiatives need to be provided as an approach towards increasing women's empowerment, especially among single mother entrepreneurs. Resilient women can transform families, thereby bringing great changes to society and the economy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, ASAS and NMY.; methodology, SMZ.; validation, ASAS, NMY and SMZ; formal analysis, ASAS and SMZ; resources, ASAS, NMY and SMZ.; writing—original draft preparation, ASAS.; writing—review and editing, NMY; supervision, ASAS; project administration, NMY; funding acquisition, NMY. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Multimedia University IR Fund 2022, MMUI/220005. The APC was funded by Multimedia University, Malaysia.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is not publicly available due to copyright.

Acknowledgments

The team acknowledges and expresses gratitude for the funding assistance from the Multimedia University’s Internal Research Fund (MMUI/220005). The team also would like to thank Mr Baktiar Hasnan, Ms Nur Rabikha Zainudin and Ms Hani Suhaila Ramli from PENDIDIK (Association for Digital Community Education) for assisting the data collection process, and the logistical support rendered by the Research and Innovation Unit of Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM) towards the completion of research).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ab-Rahim, R., Shah, S.U.M., & Raki, S. (2018). Impacts of NGOs microfinance on women empowerment in Northern Pakistan. International Journal of Academi Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(12), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Addai, B. (2017). Women empowerment through microfinance: Empirical evidence from Ghana. Journal of Finance and Accounting, 5(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.M., & Ahmad, M.M. (2016). Role of microfinance towards socio-economic empowerment of Pakistani Urban women. Anthropologist, 26(3), 189–197. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.W., Mohd Nor, N.H., Bahari, N.F., Baharudin, N.A., Ripain, N. (2019). Tahap dan indeks keberkesanan program mikrokredit terhadap pemberdayaan ibu tunggal di Selangor. Institut Wanita Berdaya: Petaling Jaya, Selangor.

- AIM. (2020a). Bengkel Keusahawanan Sahabat AIM 2020. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/AmanahIkhtiarMalaysia/videos/345318113531945/?__tn__=%2 Cd%2CPR&eid=ARBJvJYCvKPodUCsvpu2Jq_mKqHS0OHoce3XaNCieNK48oIoKmeAOCTDL WDraIFdf_2IUUPw9En3-Y.

- AIM. (2020b). Pakej Rangsangan Ekonomi Amanah Ikhitar Malaysia (AIM) bagi membantu peminjam-peminjam Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (Sahabat AIM). Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/AmanahIkhtiarMalaysia/photos/pcb.3200868319947214/32008

67069947339/?type=3&theater.

- Al-Mamun, A., Ibrahim, M. A. H. B., Muniady, R., Ismail, M. B., Nawi, N. B. C., & Nasir, N. A. B. M. (2018). Development programs, household income and economic vulnerability: A study among low-income households in Peninsular Malaysia. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 14(4), 353-366. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shami, S.S.A., Majid, I. B. A., Rashid, N. A., & Hamid, M. S. R. B. A. (2014). Conceptual framework: The role of microfinance on the well-being of poor people cases studies from Malaysia and Yemen. Asian Social Science, 10(1), 230-242. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shami, S.S.A., Majid, I., Mohamad, M.R., & Rashid, N. (2017). Household welfare and women empowerment through microfinance financing: Evidence from Malaysia microfinance. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 27(8), 894–910. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shami, S.S.A., Razali, R.M., & Rashid, N. (2017). The effect of microfinance on women empowerment in welfare and decision-making in Malaysia. Social Indicators Research, 137(1), 1073-1090. [CrossRef]

- Anthony, N.T.R., Rosliza, A.M., & Lai, P.C. (2019). The literature review of the governance frameworks in the health system. Journal of Public Administration & Governance, 9(3), 252-260. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee A.V., Duflo E., Glennerster, R., & Kinnan C. (2015). The miracle of microfinance: Evidence from a randomized evaluation. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 7(3) 22–53. [CrossRef]

- Bartik, A. W., Bertrand, M., Cullen, Z.B., Glaeser, E. L., Luca, M., & Stanton, C.T. (2020). The impact of Covid-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), 117(30), 17656-17666. [CrossRef]

- Bartz, W., & Winkler, A. (2016). Flexible or fragile? the growth performance of small and young businesses during the global financial crisis — evidence from Germany. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(2), 196–215. [CrossRef]

- Batool, S.A., Ahmed, H.K., and Qureshi, S.N (2016). Economic and psycho-social determinants of psychological empowerment in women. Pakistan Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 14(1), 21-29.

- Booth, S. A. (1993). Crisis Management Strategy: Competition and change in modern enterprises. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bourletidis, K., & Triantafyllopoulos, Y. (2014). SMEs survival in a time of crisis: Strategies, tactics and commercial success stories. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 148(1), 639–644. [CrossRef]

- Büchi, M. (2020). A proto-theory of digital well-being. Department of Communication & Media Research and Digital Society Initiative. Working Paper. Switzerland: University of Zurich.

- Casey, M., Saunders, J., & O’Hara, T. (2010). Impact of critical social empowerment on psychological empowerment and job satisfaction in nursing and midwifery settings. Journal of Nursing Management. 18(1), 24-34. [CrossRef]

- Cassia, L., & Minola, T. (2012). Hyper-growth of SMEs: Toward a reconciliation of entrepreneurial orientation and strategic resources. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 18(2), 179–197. [CrossRef]

- Che Omar, A.R., Ishak, S., & Jusoh, M.A. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 Movement Control Order on SMEs’ businesses and survival strategies. Malaysian Journal of Society and Space, 16(2), 139–150. [CrossRef]

- Cook, J. (2015). A six-stage business continuity and disaster recovery planning cycle. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 80(3), 22–33.

- Diefenbach, S. (2018). The potential and challenges of digital well-being interventions: Positive technology research and design in light of the bitter-sweet ambivalence of change. Frontiers in. Psychology, 9(331), 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Durrani, M. K. K., Usman, A., Malik, M. I., & Ahmad, S. (2011). Role of microfinance in reducing poverty: A look at social and economic factors. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 21(2), 138-144.

- Fabeil, N.F., Pazim, K. H., & Langgat, J. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis on Micro-Enterprises: Entrepreneurs’ perspective on business continuity and recovery strategy. Journal of Economics and Business, 3(2), 837-844. [CrossRef]

- Fairlie, R. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on small business owners: Evidence from the first three months after widespread social-distancing restrictions. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 29(4), 727-740. [CrossRef]

- Ferdousi, F. (2015). Impact of microfinance on sustainable entrepreneurship development. Development Studies Research, 2(1), 51-63. [CrossRef]

- Fofana, B.N., Antonides, G., Niehof, A. & van Ophem, J.A.C. (2015). How microfinance empowers women in coˆte d’Ivoire. Review of Economics of the Household, 13(4), 1023-1041. [CrossRef]

- Francina, P.X. & Joseph, M.V. (2013). Women empowerment: The psychological dimension. Rajagiri Journal of Social Development, 5(2), 163-176.

- Gong, R. (2020). Coping with Covid-19: Distance learning and digital divide. Khazanah Research Institute: Kuala Lumpur.

- Guilford, J.P. (1973). Fundamental statistics in psychology and education. McGraw Hill: New York, NY.

- Hamdan, H., Othman, P., & Hussin, W.S.W. (2012). The importance of monitoring and entrepreneurship concept as the future direction of microfinance in Malaysia: A case study in the state of Selangor. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship, 3(1), 1-25.

- Hamdan, N.H., Kassim, S., & Lai, P.C. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic crisis on microentrepreneurs in Malaysia: Impact and mitigation approaches. Journal of Global Business and Social Entrepreneurship, 7(20), 52-64.

- Hansen, N. (2015). The development of psychological capacity for action: The empowering effect of a microfinance programme on women in Sri Lanka. Journal of Social Work, 21(71), 597–613. [CrossRef]

- Henry, H.M. (2011). Egyptian women and empowerment: a cultural perspective. Women’s Studies International Forum, 34(3), 251-259. [CrossRef]

- Herath, H.M.W.A., Guneratne, L.H.P., & Sanderatne, N. (2015). Impact of microfinance on women’s empowerment: A case study on two microfinance institutions in Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka Journal of Social Sciences, 38(1), 51–61. [CrossRef]

- Kaber, N. (2011). Between affiliation and autonomy: navigating pathways of women’s empowerment and gender justice in rural Bangladesh. Development and Change, 42(2), 499-528. [CrossRef]

- Kamaruzuki, M.N. (2020). Mutu jalur lebar dalam menghadapi kejutan Covid-19. Khazanah Research Institute: Kuala Lumpur.

- Kato, M. P., & Kratzer, J. (2013). Empowering women through microfinance: evidence from Tanzania. Journal of Entrepreneurship Perspectives, 2(4), 31–59.

- Kim, J.C., Watts, C., Hargreaves, J.R., Ndhlovu, L.X., Phetla, G., Morison, L.A., Busza, J., Porter, J.P.H., & Pronyk, P. (2007). Understanding the impact of a microfinance-based intervention on women’s empowerment and the reduction of intimate partner violence in South Africa. American Journal of Public Health, 97(13), 1794–1802. [CrossRef]

- Koh, H.L, Solarin, S.A., Yuen, Y.Y., Ramasam, S., & Guan, G.G. (2021). The impact of microfinance services on the socioeconomic welfare of urban vulnerable households in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Society, 22(2), 696-712. [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and psychological measurement, 30(3), 607-610. [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.C., & Scheele, W. (2018). Convergence of technology in the E-commerce world and venture capital landscape: South East Asia, global entrepreneurship and new venture creation in the sharing economy. IGIGlobal, 149–168. [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.C. (2020) Intention to Use a Drug Reminder App: A Case Study of Diabetics and High Blood Pressure Patients, SAGE Research Methods Cases: Medicine and Health, 1-19.

- Lythreatis, S., Singh, S.K., & El-Kassar, A. (2021). The digital divide: A review and future research agenda. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 175(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Mariyono, J. (2019). Micro-credit as a catalyst for improving rural livelihoods through the agribusiness sector in Indonesia. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 11(1), 98–121. [CrossRef]

- Maru, L.C., & Chemjor, R. (2013). Microfinance interventions and empowerment of women entrepreneurs’ rural constituencies in Kenya. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 4(1), 84-95.

- Mohammad, Z.Z., Abu Bakar, J., Syed Abu Thahir, S.B., Mohd Salleh, H., & Ishak, K. (2022). Pandemic to endemic: A review of key enablers of small medium enterprise resilience. The Journal of Management and Theory Practice, 3(2), 7-17. [CrossRef]

- Nazier, H., & Ramadan, R. (2018). What empowers Egyptian women: resources versus social constraints? Review of Economics and Political Science, 3(3/4), 153–175. [CrossRef]

- Nunally, J., & Bernstein, I. (1994). Psychometric theory. McGraw Hill: New York, NY.

- Omar, M. Z., Noor, C. S. M., & Dahalan, N. (2012). The economic Performance of the Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia rural microfinance programme: A case study in Kedah. World Journal of Social Sciences, 2(5), 286-302.

- Omora, N. O., & Omwange, A. M. (2013). The Utilization of Microfinance Loans and Household Welfare in the Emerging Markets. European International Journal of Science and Technology, 2(3), 59-78.

- Paul, K. N., Nyaga, J., & Karoki, J. M. (2013). An evaluation of legal, legislative and financial factors affecting the performance of women micro-entrepreneurs in Kenya. European Journal of Business and Management, 5(8), 16-26.

- Riduwan, M.B.A. (2012). Skala Pengukuran Variable-variable: Penelitian. Alfabeta: Bandung.

- Rahman, M.M., Khanam, R. & Nghiem, S. (2018). The effects of microfinance on women’s empowerment: new evidence from Bangladesh. International Journal of Social Economics, 44(12), 1745-1757. [CrossRef]

- Ran, L., Chen, X., Wang, Y., Wu, W., Zhang, L., & Tan, X. (2020). Risk factors of healthcare workers with coronavirus disease 2019: a retrospective cohort study in a designated hospital of Wuhan in China. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 71(16),2218-2221. [CrossRef]

- Roffarello, A.M., & Russis, L.D. (2019). The race towards digital wellbeing: Issues and opportunities. In CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Proceedings of Association for Computing Machinery, Glasgow, Scotland, May 4–9. [CrossRef]

- Rokhim, R., Sikatan, G.A.S., Wibisono Lubis, A. & Setyawan, M.I. (2016). Does microfinance improve wellbeing? Evidence from Indonesia. Humanomics, 32(3), 258-274. [CrossRef]

- Saad, N. M., & Duasa, J. (2010). An Economic Impact Assessment of a Microfinance Program in Malaysia: The Case of Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM). International Journal of Business & Society, 12(1), 1-14.

- Salia, S., Hussain, J., Tingbani, I., Kolade, O. (2018). Is women empowerment a zero-sum game? Unintended consequences of microfinance for women’s empowerment in Ghana. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 24(1), 273-289. [CrossRef]

- Sarumathi, S., & Mohan, K. (2011). Role of Microfinance in Women’s Empowerment (An Empirical Study in Pondicherry Region Rural SHG). Journal of Management and Science, 1(1), 1–10.

- Sipahutar, M.A., Oktaviani, R., Siregar, H. and Juanda, B. (2016). Effects of credit on economic growth, unemployment and poverty. Jurnal Ekonomi Pembangunan: Kajian Masalah Ekonomi dan Pembangunan, 17(1), 37-49. [CrossRef]

- Torri, M.C. & Martinez, A. (2014). Women’s empowerment and micro-entrepreneurship in India: Constructing a new development paradigm? Progress in Development Studies, 14(1), 31-34. [CrossRef]

- Van Rooyen, C., Stewart, R. & de Wet, T. (2012). The impact of microfinance in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of the evidence. World Development, 40(11), 2249-2262. [CrossRef]

- Wellalage, N. & Locke, S. (2017). Access to credit by SMEs in South Asia: do women entrepreneurs face discrimination? Research in International Business and Finance, 41(1), 336-346. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).