1. Introduction

Living systems (LSs) must solve the serious problem of detecting their environment to act appropriately for maintaining relationships internally and externally for survival and reproduction by adaptation, but how? Natural selection theory does not explain adaptation, but only explains the spread of adaptations if they exist.

How can LSs detect their external reality, whether the reality is biotic or abiotic, and respond accordingly? One might answer that organisms detect stimuli or information from their surroundings and react to them appropriately. This is an externalist perspective, in which an external observer (scientist or experimenter) observes a given LS and its surroundings from the outside. However, any LS cannot take this perspective because it cannot observe itself and its surroundings from the outside. This problem is a biological version of a philosophical enigma of how the self can know the existence of external reality, that is, escape solipsism. There is yet to be consensus on solutions in the scientific community.

Let us consider a perspective from the inside of an LS (i.e., the internalist perspective) in which no external observer is assumed. Our question may be more precise: How can LSs confirm the reality outside by distinguishing it from internal states such as hallucinations? How can passive, inert physical matter compose an LS capable of this? How can such LSs develop the ability to be aware or conscious of their surroundings? Put philosophically, how can LSs, including humans, escape “solipsism” (i.e., a philosophical doctrine that only I exist)?

In this paper, the author proposes a comprehensive theory to solve the problem of adaptation by updating and integrating studies by the author, focusing on the probability of events in LSs [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5], an information theory of semiosis and mind [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10], and hierarchical structures of LSs [

11]. An outline of this paper is provided in

Section 2, and arguments on each specific topic are presented in the following sections.

2. Overview of This Study

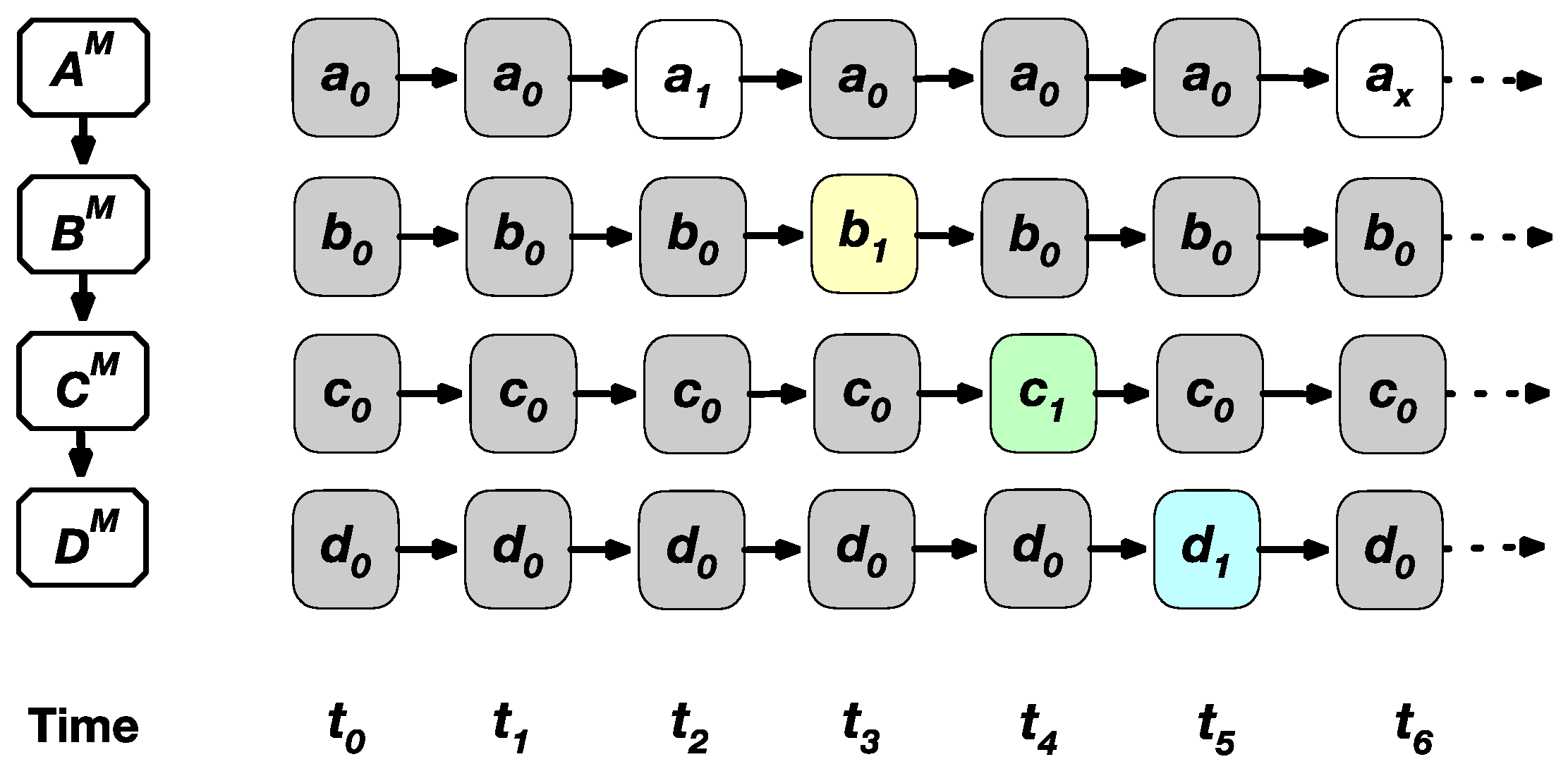

(1) LSs are characterized as systems that have the following properties: (i) making an internal organization, (ii) making a relationship with external states, (iii) reproduction, (iv) formation of ecosystems, and (v) evolution. Adaption is the core concept that concerns all these properties. Adaptation is defined as the property of changing their states to maintain a particular relationship with their environments in ecosystems to maintain internal organizational order for self-making (survival) and reproduction. Differential survival and reproduction lead to the evolution of a population of LSs. Natural selection theory explains the spread of adaptive traits, not adaptation. We have not yet reached a comprehensive theory of adaptation in consensus. [

Section 3]

(2) LSs must solve the serious problem of adaptation by detecting their environment to act appropriately. This problem is a biological version of the philosophical enigma of how the self can escape solipsism. For this problem, a hierarchical extension of the “cognition” concept is proposed. Cognition is a related state change occurring at the three nested hierarchy levels, classified as physical, chemical, and semiotic cognitions. Any entity that cognizes is called a “cognizer.” Cognition at the physical and chemical levels does not mean these entities are aware of the outside or conscious, which can emerge at the semiotic level (discussed in section 7 in detail). By this extension, physical and chemical entities can detect their surroundings by related state changes, which makes semiotic cognition possible. [

Section 4]

(3) Semiotics is necessary for life to emerge and evolve. LSs invented semiotic cognitions based on physical and chemical cognitions to manage the probability of events occurring to an actor. Adaptation is explained in terms of the theory of internal probability. This theory clarifies the probabilities of events occurring to an entity within a system, not to an external observer. The internal probability includes the certainty of events occurring after a particular action, and the relative frequency of events after an overall range of actions [

Section 5]

(4) The mathematical model for the cognizers system (the “CS model”) is presented, in which explicit definitions of cognition, cognizer, system, internal/external observers, the world, the causal principle, event/state, and causation are provided as foundations for theorizing adaptation. [

Section 6]

(5) The model of semiotic cognition is presented using the CS model. A general model is essential to avoid obscure arguments using a mixture of physics, chemistry, and biology languages, if the general model can be translated into those languages. In the CS model, some aspect of semiotic cognition relates to mental processes. For semiotic cognition to operate, LSs must measure the external states and generate symbols that signify the external states, local or global, based on which they change the effector states. For this task, LSs invented a measurement system based on “inverse causality” (not reverse causation or backward causation), the principle operating in a subject LS to produce symbols internally that signify past states of the external reality hidden from the subject. This symbol generation by inverse causality is proposed as a universal principle for a system to be aware of the external world, which is the core function of consciousness. [

Section 7]

(6) In conclusion, mind and matter can be unified as cognizers in a monistic framework of the CS model. Here, physical and chemical entities (cognizers) can generate a higher level of cognition (i.e., semiotic cognition) if they form a specific structure to operate inverse causality, by which the system can produce symbols that signify hidden external states and act (physically or behaviorally) to adapt to the surroundings. This operation makes the living systems aware of the external world. [

Section 8]

In this paper, “external reality,” “external world,” “environment,” “surroundings,” and “outside” are used interchangeably.

3. What is Life?

3.1. Five Properties of LSs

Many definitions and characterizations of life have been proposed [

12]. They vary according to researchers, including various aspects and forms of life depending on their evolutionary stages. According to previous studies, we can characterize five properties of LSs as material systems as follows that distinguish them from nonliving entities:

(i) Making an internal organization: LSs produce system components by metabolism and maintain organizational order in the components’ states, incorporating material/energy resources from outside and discarding waists. This process forms a unity of self-making process (within a generation), separating itself from others (i.e., autopoiesis) with a boundary. Survival refers to the maintenance of this organization.

(ii) Making a relationship with external states: LSs make an external relationship beneficial to maintain the internal organization (i.e., survival), including obtaining resources and avoiding natural enemies and physical risks. LSs sense and respond to their environments (or biotic and abiotic conditions) with which they maintain beneficial relationships for self-making at a high degree of certainty.

(iii) Reproduction: LSs reproduce their self-making organizations, whereby orders are transmitted over generations, forming a population of LSs.

(iv) Formation of an ecosystem: The population of LSs exists as a member of an ecosystem only in which they can obtain material/energy resources (above (i)) by maintaining beneficial relationships with others (above (ii)) characterized as specific ecological niches (positions relative to heterospecific LSs).

(v) Evolution: The population of LSs evolves by generating new types of self-making systems, with some replacing old types by competition by natural selection or by drift; otherwise, coexisting with the old, creating diversity.

3.2. Adaptation

LSs, such as unicellular or multicellular organisms, are an open system. Adaptation of LSs is defined as the property of changing their states to maintain a particular relationship with their environments in ecosystems to maintain internal organizational order, i.e., an internal relationship among components, for self-making (survival) and reproduction. Differential survival and reproduction lead to the evolution of a population of LSs. Therefore, adaptation concerns all the five properties mentioned above.

Organismic traits in morphology, physiology, and behavior inseparably shape adaptations to the environments. For example, the morphology of an organism and its internal organization affect its behavior in relation to the environment. An organism’s digestive system (including anatomy and enzymes) and the preference for food items (as an external relationship) are also inseparable in adaptation. Similarly, an organism’s metabolic systems in neurons and neural networks affect its behavior, generating its relationship with the environment.

Adaptation includes reproductive performance. LSs perform processes for reproduction within a generation at cell or multicellular levels in various forms (such as binary fission, budding, fragmentation, and production of spores/seeds or eggs (ova)/sperms). LSs possess molecular and physiological mechanisms that allocate energy and material resources for reproduction. Reproduction also requires a particular relationship with the environment, such as nutrient acquisition and finding oviposition sites. Organisms in sexual species need to encounter mates in animals and perform seed dispersal and pollination mediated through wind, water, or pollinators in plants.

The external conditions include physical and chemical conditions (e.g., temperature, moisture, pressures, pH, etc.) in addition to biological ones (available resources, abundance, predators, competitors, symbiotic partners, etc.). An LS alone cannot fully determine its relationship with the environment because the complete determination of the relationship requires the determination of the environmental state to be done. For example, an encounter between prey and predators occurs based on their behavior. Similarly, a chemical reaction catalyzed by the enzyme is determined by molecular movements of substrate and enzyme molecules. The relationship between LSs, including the same and different species, and their environments, including living and nonliving entities, forms an organization at a higher level, i.e., an ecosystem. The external relationship, including biotic and abiotic entities, for an LS can characterized as an ecological “niche” [

13,

14,

15]. Organisms cannot fully determine (construct) their niches alone; instead, niches are generated by entire interactions in an ecosystem. (section 5.5).

3.3. Natural Selection Theory Does Not Explain Adaptation

Evolution by natural selection is referred to as adaptive evolution in contrast to neutral evolution. However, the theory of natural selection does not explain how LSs can adapt to their environments; it explains the spread of adaptive traits in a population, given the variation of adaptations. Darwin [

16] summarizes the theory of evolution by natural selection: “As many more individuals of each species are born than can possibly survive; and as, consequently, there is a frequently recurring struggle for existence, it follows that any being, if it vary however slightly in any manner profitable to itself, under the complex and sometimes varying conditions of life, will have a better chance of surviving, and thus be NATURALLY SELECTED. From the strong principle of inheritance, any selected variety will tend to propagate its new and modified form”.

Based on Darwin’s theory, evolutionary biologists have sophisticated it as a standard model, which is summarized as follows: Given a local environment, and if the following “conditions” are met for a given population, the population will evolve automatically as the necessary outcome of a non-random probabilistic process [

17,

18,

19,

20]. (i) a variation of organismal traits (such as physiology, morphology, and behavior) in the population, including the generation of new genetic types; (ii) organisms with different traits exhibiting “differential survival and reproduction” (i.e., natural selection); and (iii) heritability of organismal traits. The degree of survival and reproduction is called “fitness.” The model, including the original Darwin’s theory, does not explain how adaptation arises from organismic traits and interactions with the environment in general terms. In the theory, adaptation is defined as the ability to survive and reproduce, and is not explained in terms of other basic processes [

21]. Natural selection tests adaptations, not produce them.

Fitness must be defined in terms of the potential ability (not actual data) to avoid circular (tautological) explanations; actual data is the evidence for the potential ability [

22,

23,

24]. However, we have yet to have a general theory describing how LSs’ traits generate the ability to survive and reproduce in a given environment. Here, adaptation is inseparable from the environment.

3.4. Is “Information” an Answer for the Adaptation Problem?

Information plays a vital role in science. In the literature, we found that many information-theoretic accounts for adaptation. For example, LSs take information about their surroundings, acting to have beneficial relationships with them. The information obtained from a receptor is processed through signal transduction and regulates gene expression in response to environmental changes. “Information” is reified as a third entity in addition to matter and energy without explicit definition. In this study, we do not use “information” as an explanans (a term by which we explain adaptation) to avoid the risk of a circular explanation. “Information” needs to be defined in terms of more basic concepts. In the framework of CS model, information is defined as a “related (or relational) state change,” whether occurring in an observer in relation to an observed system (i.e., epistemic related state changes, such as ”knowing”) or occurring in material components in a system (ontic related state changes, such as “order formation” or “pattern transmission”). The information thus defined is nothing other than “cognition, ” which is defined in the CS model and explained in the next section.

4. Hierarchical Extension of Cognition

4.1. Cognition as a Related State Change

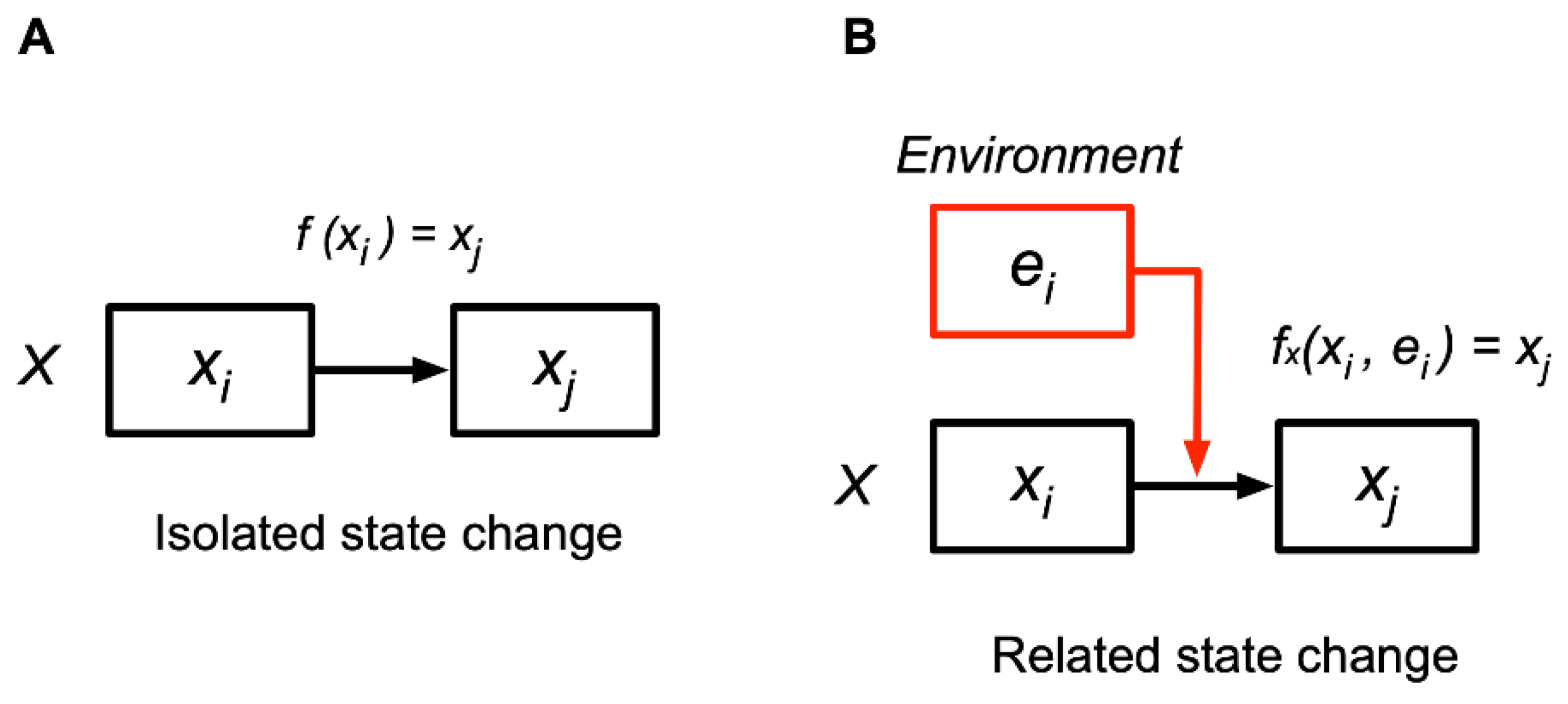

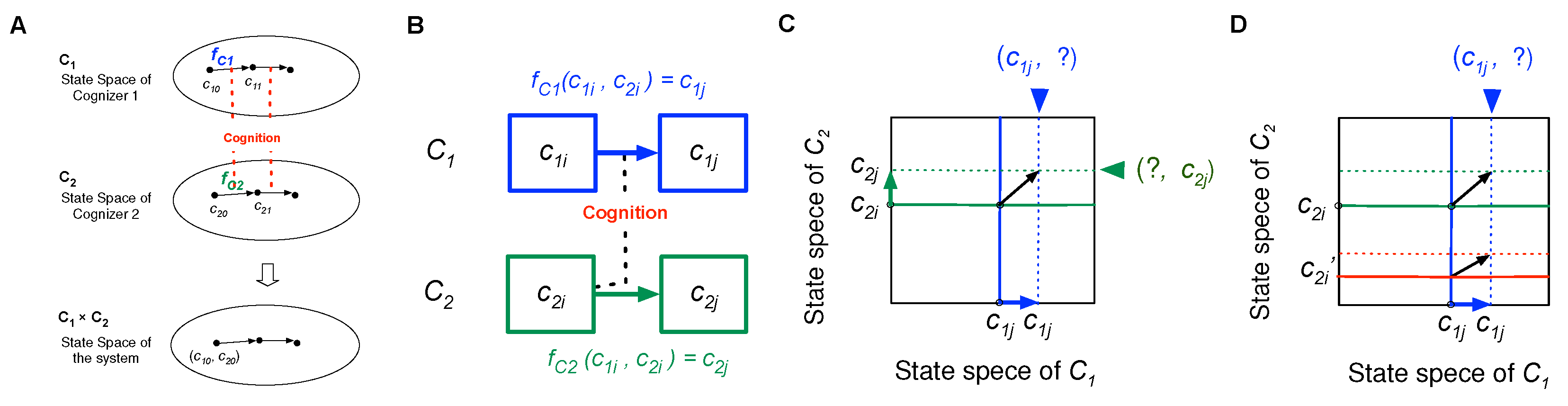

The CS model extends the cognition concept to the physical and chemical levels. “Cognition” is the determination of a succeeding state in relation to the external states, which is a related state change, dependent on others’ states in the world. Cognition is contrasted with “isolated state change” (Fig. 1A). An isolated state change from x to y is represented as xi ⟼ xj (⟼ denotes a state change). A related state change (cognition) from state xi to xj occurs in response to the environment in state ei, denoted as fxi(xi, ei) = xj (Fig. 1 (B)), in which the entity in state xi cognizes the environment in ei, changing to xj. Cognitions among entities make their relations by changing states context-dependently.

Cognition is used as defined above in the CS model, if not otherwise mentioned. Cognition is not identical to sentience, awareness, or consciousness, but cognition conceptually includes awareness or consciousness as a special kind of cognition. For example, when we say that an electron or a billiard ball is a cognizer, this does not mean it is conscious; instead, it changes from a current state to a succeeding state context (environment) dependently. Any entity that cognizes is called a “cognizer.” The world is made of cognizers in the CS model, which is a monistic model.

Cognition is also represented in the same meaning as “acting” as a state change of a cognizer in a current condition. Acting is not “acting on” (having a particular effect on) another cognizer, such as, e.g., pushing and pulling. Every cognizer is acting in the current condition every moment, not forced or controlled by the condition. For example, a stone will move when you push it. The CS mode describes it as your hand cognizing the stone and the stone cognizing your hand (changing in velocity and position).

Cognition has two aspects: discriminability and selectivity. An entity can change from a current state to different succeeding states against some different external states. Discriminability refers to the ability to discriminate between different external states. Selectivity refers to another aspect of state change in that a state change is selecting a succeeding state among possible ones (“Selection” should not be confused with natural selection).

Figure 1.

(A) Isolated state change refers to a change that occurs independent of the environment. (B) Related state change refers to a change that occurs depending on the environment, called cognition.

Figure 1.

(A) Isolated state change refers to a change that occurs independent of the environment. (B) Related state change refers to a change that occurs depending on the environment, called cognition.

4.2. Cognition at Three Levels

Cognition, as defined above, includes state determination at various levels of the hierarchy of natural systems, which are classified into three levels: physical, chemical, and semiotic. Semiotic cognition is inherent to LSs and human-made machines; however, physical and chemical cognitions also operate in living systems.

(1) Physical cognition

Cognition at the physical level (“physical cognition”) refers to changes in the physical state of an atom and subatomic entity in relation to the environmental (outside) states, such as positions, velocities, and quantum states; here “physical” is used in the sense of classical or quantum physics. This cognition occurs by physical forces such as gravity, electromagnetic forces, and weak and strong forces within atoms. Physical cognition includes any state changes occurring at the subatomic and macro scales, including quantum state determination, such as the collapse of wave functions. Physical cognition is discriminative and selective at a physical level.

(2) Chemical cognition

Cognition at the chemical level (“chemical cognition”) refers to changes in the molecular state and configuration of a molecule in relation to the environment (outside) states, leading to chemical reactions/interactions for self-making and reproduction of living cells (i.e., metabolism, protein synthesis from DNA, and replication of DNA). The electromagnetic field generates the major forces operating at this level of cognition, leading to covalent bonds and noncovalent bonding (ionic bonding, hydrogen bonding, metal coordination, hydrophobic forces, van der Waals forces, etc.) to generate order (structure) or relationships among component atoms [

25,

26]. The van der Waals force is important for coupling between molecules of high molecular weights, whereby a molecule “recognizes” the complementary shape of another molecule [

27]. Chemical cognitions occur when interacting with the external states of atoms or molecules under physical conditions, such as pressure and temperature.

Chemical cognition is discriminative and selective at a chemical level. As an example of discriminability (or discrimination), an ion-channel protein or allosteric enzyme changes the molecular structure only when a particular molecule is bound. As an example of selectivity (or selection), the protein changes its molecular structure to make the channel closed (or open) instead of open (or closed) when a given ligand molecule is bound.

(3) Semiotic cognition

External states for LSs may change continuously. If LSs react to all these local states through physical and chemical cognitions, they cannot maintain favorable relationships with the outside. They need to respond to particular external states relevant to survival while ignoring others. Furthermore, LSs are blind to distant external states under the principle of local causation (any causal effect can occur only in the locality;

Section 6). Discrimination between the states of non-local entities through physical and chemical cognitions is impossible owing to action at a distance, putting aside the non-local state correlation of the quantum states in entanglement. LSs have invented semiotic cognition, which can emerge at the level of LSs such as cells and multicellular organisms.

Semiotic cognition is a related state change by semiosis. Semiosis is a process that arises from a system of physical and chemical cognizers in a specific structure (see

Section 7 for details). When a bacterial cell swims toward a denser area of sugar, it is not pulled by the sugar molecules; similarly, when a cat finds a mouse and starts running toward it, the cat is not pushed by photons reflected by the mouse. These state changes related to the environments are examples of semiotic cognition, constituted by physical and chemical cognitions as component processes in LSs. Hoffmeyer [

28] called such a sign-mediated adaptive process “semiotic causation,” which operates through the mechanisms of material efficient causation.

Semiotic cognition is the sign or signal-mediated cognition generated by physical and chemical cognitions connected with a specific structure. Sign and signal are treated as the same concept in the CS model. Both sign and signal are etymologically derived from Latin signum, meaning ‘identifying mark, token, indication, symbol, etc.’ [

29].

Consider a system of physical or chemical components as cognizers. If there is a relatively high state correlation between two entities (i.e., a high amount of mutual information in Shannon’s theory), an LS can determine the state of a distance entity (object) by cognizing a local entity (a sign or sign vehicle for the object) with certainty to the degree of their correlation.

A sign is interpreted (decoded) by a subject system, by which the sign signifies a certain object as its meaning; meanings are subject-dependent, not objectively assigned by the meta-observer. There may be many entities outside and inside the system with which a sign can have state correlations, some of which may be relevant and others irrelevant to the entire system’s teleonomic operation. Therefore, the interpretation (meaning) of a given sign includes the choice of a certain object in correlation and the way the entire system acts to give rise to a certain relationship with the object. For example, a certain kind of molecule is released from a frog. A fly at a distance cognizes the molecule and many kinds of molecules from other origins, and flies away. In this case, the fly interprets a datum from the molecule as a “dangerous frog” (object) and flies away. If a snake cognizes the molecule, it would interpret them as a “delicious frog” and will approach it. Here, the datum on the molecule (sign) indicates not a neutral frog (something cognized by an external observer) but a frog with a specific meaning for the subject to determine the following “action” (i.e., selection of a succeeding state).

To demonstrate the distinction between physical and semiotic cognitions, consider a scenario in which a person is lying down on a street. If the person's eyes open in response to shaking the body or speaking to them, this constitutes a semiotic cognition. In this situation, the body also moves in response to the hand's touch, which represents a physical cognition. It is important to note that physical cognition alone does not necessarily result in semiotic cognition, such as the act of opening one's eyes, which requires a specific structure of system (

Section 7 for details).

Semiotic cognitions, irreducible to lower levels’ laws, are teeming with living processes in signal transduction in regulating metabolism and gene expression within and between cells [

30]. Semiotic cognition is not merely an aggregate of physical or chemical cognitions ruled by natural laws at their levels. Escherichia coli can utilize lactose as an energy source when glucose is absent by producing ß-galactosidase (an enzyme for lactose decomposition), whose gene is transcribed when lactose is present. Monod [

31] pointed out that the fact that lactose causes ß-galactosidase production is not a chemically or physically necessary connection. He called this unnecessary, arbitrary relationship ‘gratuity’ (see

Appendix A for details).

Barbieri [

12] calls such arbitrary connections ‘convention’ or ‘code,’ which operate as conventional rules of correspondence between two independent molecular worlds in LSs, leading to a new idea of “evolution by natural convention” as an essential ingredient of adaptive evolution in addition to natural selection and drift; he also propounded that the cell is a codepoietic system, capable of creating and conserving its own codes [

32]. Such conventions or sign systems must be diverse in the living world, reflecting differences in their semiotic spaces [

33,

34].

5. Adaptation as Managing Probability Distribution of Events Occurring to LSs

5.1. Understanding Adaptation as Managing the Probability of Events

Adaptation enables LSs to reduce the uncertainty of events that occur after taking an action or state change. This reduction is not a goal, but to increase the “probability” of preferable events occurring by the action of teleonomic (i.e., goal-oriented) systems. Probability, entropy, and information are vital concepts in understanding adaptation. However, they contain various meanings under the same name or mathematical representation. Therefore, we must develop a comprehensive adaptation theory using these concepts.

How do organismic trials produce the “potential,” not the actual, ability to survive and reproduce? Intuitively, most researchers agree that organismic trials can affect their ability to survive. However, how and to what degree a given trait affects the ability is unclear. We need a theory for adaptation that will complement the Darwinian theory.

According to Darwin (

Section 3.3), adaptation refers to profitable traits that confer a better “chance of surviving” (or “chance of surviving and of procreating their kind” in another place of the book) on the organism in the environment. This may transform our question into a more tractable one: How can LSs manage the probability of maintaining particular relationships with their environments” and internal order to survive and reproduce? The mathematical theory of probability based on Kolmogorov’s axioms [

35] inspired substantial advances in scientific investigations. Probability is now a common language in science. However, the theory does not present the meaning of probability. This situation creates problems when the mathematical theory is applied to problems in science. Probability has been recognized as having a dual meaning, one aspect of which is subjective (epistemic) and the other objective (ontic) [

36]. In the subjective interpretation, probability measures the degree of certainty of events occurring due to the incompleteness of knowledge (i.e., ignorance) about the object system. The objective interpretations include the relative frequency, actual or hypothetical, of an event in a population of events; and the system’s propensity (or tendency) to yield a long-run relative frequency of an event [

4,

37,

38].

The propensity interpretation of fitness enjoys popularity among philosophers of biology [

24,

39,

40] because fitness is independent of our knowledge. According to propensity interpretation, relative frequency is evidence of such objective propensity to produce a certain statistical average [

37,

38,

41]. The propensity theory interprets probability as the propensity, or tendency, of the system or situation to yield a long-run relative frequency of an event. However, it is unclear what properties of systems or their components determine this probabilistic tendency and how we can know it without an actual measurement (relative frequency). Sober [

21] pointed out the circularity of this interpretation: ‘propensity seems to be little more than a name for the probability concept we are trying to elucidate’.

The traditional interpretations, subjective or objective, described above deal with events for external observers that observe material systems from outside. They do not apply to events that occur to internal observers acting as players, such as LSs. Therefore, we need an alternative framework in which epistemic observations are objectified as the state changes of LSs in relation to their environments. Here, LSs are described as objectified subjects (i.e., cognizers) that experience events within a system. Nakajima [

1] developed a theoretical framework for this type of probability named “internal probability” using the cognizers system model (section 6), in contrast to “external probability,” which refers to the probability of events experienced by an observer external to the system. Internal probability includes two kinds:

(i) The degree of certainty of an event occurring after a specific cognition (i.e., a state change) of the environment by a focal cognizer, named "internal Pcog." Precisely, consider a focal state change of a cognizer in a finite length of a system's temporal state sequence (e.g., "tossing a coin from a height of 1m"; "moving in the left direction") as the specific condition for subsequent events to occur; the degree of certainty is measured by the ratio of the number of a focal event type that occurred (e.g., heads up; encounter with a car) to the total number of all the events that occurred (e.g., {heads, tails}; {encounter with a car, encounter with a bike, ...}).

(ii) The relative frequency of an event occurring after an overall range of cognitions (i.e., a state changes) by a focal cognizer during the system process (i.e., all types of cognition without specifying any particular one) named "internal Poverall." Specifically, consider all types of state changes of a cognizer in a finite length of a system's temporal state sequence (e.g., {tossing from heights of 1m, 2m, ... and 10m}; {moving in the left, right, and straight directions) as the overall condition for subsequent events to occur. The relative frequency is measured by the ratio of the number of a focal event type (e.g., heads; encounter with a car) to the total number of all types of events (e.g., heads and "tails up") that occurred (e.g., {heads, tails}; {encounter with a car, encounter with a bike, ...}).

Notions of Pcog and Poverall apply to external observers; in this case, they are called “external Pcog” and “external Poverall,” respectively (Nakajima, 2019). Whether internal or external, Pcog and Poverall are not descriptions of actual ratios but reflect the properties of a focal cognizer and the cognizers system (Nakajima, 1999, 2001, 2003, 2013), as illustrated using thought experiments in the next section.

5.2. Thought Experiments for Understanding Semiotic Cognition as Adaptation

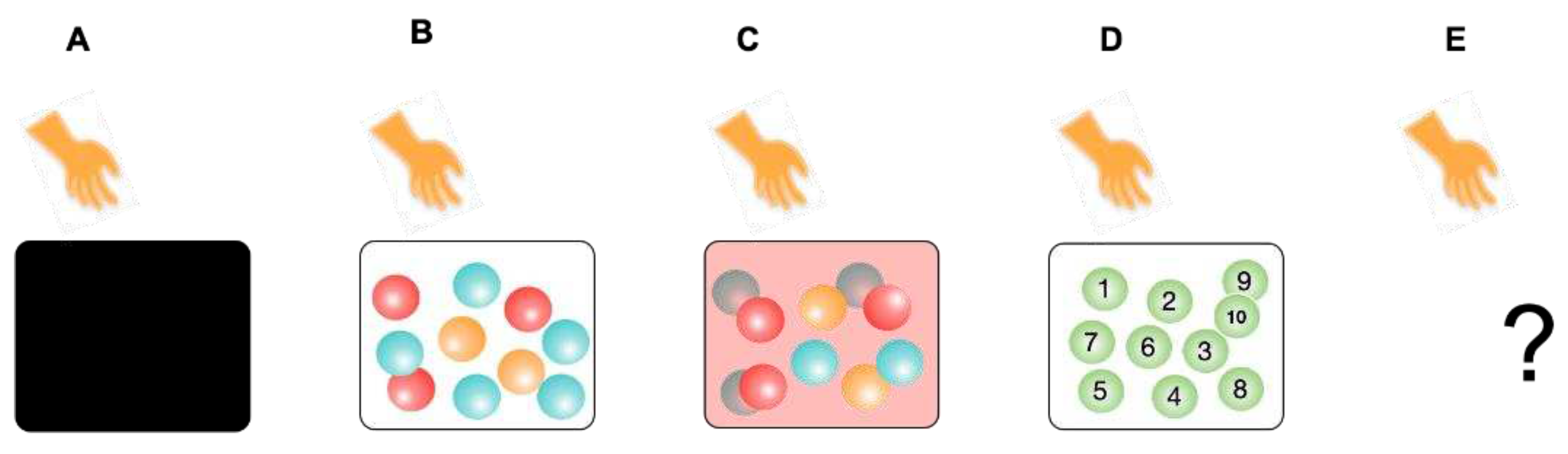

Biological adaptation can be characterized as the property to manage the internal probability of events by cognitions at the three levels operating in LSs. Let us illustrate this idea using a series of thought experiments (

A to

D): A person takes one ball from a box containing ten balls, observes the ball, returns it, and mixes it up; in experiment E, conditions are hidden for us. This trial is repeated many times (

n trials). Here, the person is a player and simultaneously an observer (internal observer), an LS who performs semiotic cognitions in these experiments. The balls and box represent nonliving cognizers who change their states through physical or chemical cognitions.

Figure 2.

A person takes out one ball from a box. What is the probability of taking out a particular ball? (A) The wall is opaque, containing ten balls with two orange, three red, and five blue balls. (B) The wall is transparent, otherwise the same as A. (C) The wall is semitransparent, otherwise the same as A. (D) The wall is transparent, containing ten balls numbered from 1 to 10. (E) Conditions are unknown.

Figure 2.

A person takes out one ball from a box. What is the probability of taking out a particular ball? (A) The wall is opaque, containing ten balls with two orange, three red, and five blue balls. (B) The wall is transparent, otherwise the same as A. (C) The wall is semitransparent, otherwise the same as A. (D) The wall is transparent, containing ten balls numbered from 1 to 10. (E) Conditions are unknown.

5.2.1. Experiment A

The box wall is opaque and contains ten balls of the same size and shape with different colors: two orange, three red, and five blue balls. What is the probability of taking out a red ball? The answer is 3/10 according to the classical theory of probability, in which the probability of an event is given by the ratio of the cases favoring the event to the total number of equally probable cases.

In this experiment, the player has the same cognition about the states of the ball-containing box due to the opaque wall. The player then moves the hand, whose movements are not adjusted specifically in correspondence to the ball’s configurations in the box. The movements may vary due to variations in the initial condition for each trial. However, the conditions are random (they do not correspond discriminatively) to the ball configurations. Therefore, the internal Pcog and Poverall of the red ball are both 3/10. (The actual relative frequency may vary depending on how many times (n) the play is repeated. As n increases, it will approach the value of 3/10 according to the law of the large number.)

How about the external Pcog and Poverall of taking a red ball? External Pcog depends on the cognitions of the external observer in focus. For example, consider an external observer like a Laplacian demon who can discriminate between all the states occurring in the system (the box, balls, and the player) and the laws ruling the state changes. For the demon, nothing is uncertain about what happens next. Given any cognition by the demon, the probability (external Pcog) of taking a red ball is one or zero for this ability. However, for this demon, the relative frequency (external Poverall) of the event will be 3/10. This is because the demon exists external to the system and cannot change the system’s behavior. For external observers with limited cognitive ability, external Pcog may vary depending on their ability, while external Poverall may be the same (3/10) if the external observer can identify the ball colors.

5.2.2. Experiment B

The box wall is transparent in this experiment, and other conditions are the same as in Experiment A. What are the internal probabilities, Pcog and Poverall, of taking out a red ball in this case? We must pay attention to the properties of the players. Here, players discern the colors and positions of the balls through the transparent wall, and the balls may not escape their hands (assumed in this experiment). Therefore, player can take any color that he/she prefers. If he likes red, then the internal Pcog of red will be 1; if he dislikes red, the Pcog will be zero. The degree of certainty of the event (i.e., red balls) is 1 if the handling of balls according to the position data is effective. The relative frequency (internal Poverall) is also 1 for red balls yielded from the overall trials under the condition that every cognition is performed with perfect discrimination of different ball configurations and appropriate actions in the trials.

The action implies the selection of a succeeding state of the player among many possibilities. Here, “selection” does not mean a choice of a specific ball or color of objects, but rather a determination of a “particular succeeding state,” actualization of one among many potential states. The property of selection, selectivity, may vary according to the players involved in this experiment. Players affect the internal and external Poverall.

Consider a modified version of this experiment using balls varying in size, weight, or surface texture, for instance, in the same transparent box. Suppose red balls are heavy or their surface is slippery. The internal Pcog and Poverall of taking out red might be less than 1, even if the player prefers red, and therefore, that of taking the second-best color would increase. These ball characteristics may affect how a ball reacts to the player’s actions (hand/finger movements of grasping and managing balls). In other words, balls are not inert, passive entities but players (cognizers) that perform physical or chemical cognitions, as described in

Section 4.

Similarly, we may use mice instead of balls for this experiment, which can perform semiotic cognitions. Mice may vary in cognitive and behavioral traits, with some being cautious and others not. In this case, a careless or slow-moving type may be taken out with a higher probability than cautious or fast-moving types. Even in the transparent condition, the player cannot necessarily take the most preferable mouse with probability 1.

Players cannot necessarily control balls. In other words, a player cannot fully determine a relation with balls (represented by a subset of the direct product of their state sets) because a relation (subset) is determined when the player and the balls have selected their succeeding states (see

Section 5.4, 6.3 for details).

5.2.3. Experiment C

In this experiment, the box wall is semi-transparent, with pink-colored walls; otherwise, the same as in Experiment A. This semi-transparency reduces the degree to which a player can discriminate between the different states of the ball configuration. What is the probability of taking out a red ball? In this experiment, even if the player prefers red balls and acts to achieve it, he might mistakenly choose an orange or blue ball because of inaccurate color cognition, and the internal Pcog and Poverall of taking out red will be less than one but higher than 3/10.

Acting in a discriminating manner, i.e., selecting different succeeding states against different environmental states (ball configurations in the box), is called “discrimination.” The ability to discriminate between different environment states in a given situation is called “discriminability,” a property of entities such as the player, balls, and the box. As illustrated in the modified version of Experiment B, the properties of balls or mice can also affect the probability (internal Pcog or Poverall) of taking a given color in Experiment C.

5.2.4. Experiment D

In Experiments B and C, the player gave a preference for red balls over other colors. The bodily state changes are physical events, in which the muscles and bone structure of their hand and fingers operate. However, this behavior occurs through semiotic cognition in which “red” may have a certain meaning, such as “beneficial.” In other words, red balls do not physically force their bodies to behave that way; this is similar to the case where people escape when feeling a “bad smell” without being pushed by forces.

Let us introduce another experiment, D, to make semiosis clearer. The box wall is transparent like B, containing 10 balls of the same color but numbered (1 to 10); otherwise, it is the same as A. What is the probability (internal Pcog) of taking out the “ball 1”? Suppose each number corresponds to gifts, e.g., 1: a bike, 2: a car, 3: a candy… Numbers are signs for hidden (distant) entities (cognizers). The answer depends on the player’s knowledge of the links between numbers and these gift items; the situation is similar to that in Experiment B. If a player wants a car and knows this link, he will behave selectively to take out ball No. 2 with probability 1; therefore, the probability of ball No. 1 will be 0. If a player knows nothing about the links, this case resembles Experiment A. In general, the player’s ability to interpret signs is intermediate, similar to Experiment C.

The degree of knowledge regarding the links may vary from entirely unknown to completely known, similar to box wall transparency in Experiments B and C. The degree of knowledge about how local situations (i.e., ball configurations) link with things (gifts) outside the box, i.e., non-local things, may be called “semiotic transparency.” For example, when you visit a town in a foreign country whose language is unfamiliar but whose icons are international, you would play in a semiotically transparent box. Physical and chemical cognitions can discriminate between local states only under the local causation. However, semiotic cognition enables cognizers to discriminate between non-local states mediated through local-global state correlations.

5.2.5. Experiment E

Experiments

A to

D share the framework of external perspective, called the “externalist framework,” in which all components, such as balls, box, and players, are provided, and we (the reader and the author) observe the systems from the meta-level (

Section 6.1). However, any LS as an internal system component cannot cognize itself and the environment from the outside. Experiment

E provides a first-person framework, where only the player is given, called the “internalist framework.” This is similar to the phenomenological approach by Edmund Husserl. No entities besides the subject (the self, “I”) are assumed (but not denied). We suspend the judgment of whether something exists external to the subject in order to discover how the subject (player) can cognize the external reality. Here, we see LSs from the inside out (see [

42] for a similar approach in brain science).

What is the probability of taking a red ball in this case? Only one observer exists within the world: the player. It appears hopeless to answer this question. However, it is not. The player will experience a temporal sequence of the mental states (senses and percepts), i.e., data from repeated trials (the data occur in the player, not described by an external observer). They include, for example, a visual image of a black box, a transparent or semi-transparent box; colored balls, mice, or numbered balls appear in a box. Some players may experience five red and five blue balls in a box, whereas others may have only one object. Note that “data” are phenomena that do not mean that the external reality causes them, which is not assumed. In response to each perceptual image, the player moved the hand and fingers. Therefore, the answer depends on the data sequence given to player. The relative frequency of percepts of “a red ball” to the total number of “a ball” indicates the probability (internal Poverall) of taking a red ball. The ratio of the number of percepts of “a red ball” to the total number of “a ball” occurring under the same perceptual condition is the probability of certainty (internal Pcog) of a red ball.

Bayesian theorem can derive these probabilities by devising hypotheses about how frequently the external worlds will likely produce events. In this scheme, one calculates probabilities using limited options of hypotheses, which are arbitrarily chosen. However, the probabilities in generative models are descriptive, not derived from a mechanistic model of interactions with a hypothetical environment (something illustrated in Experiments B, C, and D). Furthermore, the data do not necessarily refer to real external entities, which might occur in dreams. Therefore, our next problem arising from Experiment E is how LSs can escape solipsism and produce symbols that signify external states and process them to act in a reliable manner. This problem is addressed in section 7.

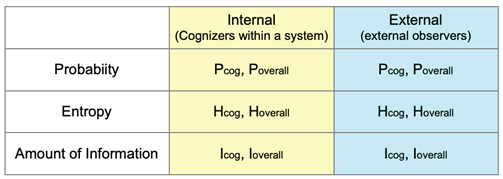

5.3. Probability, Entropy, and the Amount of Information

Concepts of probability, entropy, and information are essential to explore the general principles underlying LSs’ properties and integrate various disciplines in biology. Most researchers have not made it explicit in the literature whether the probability “P( )” is for an internal observer (cognizer) in interaction with the object events (i.e., internal probability), or an external observer, such as an experimenter (i.e., external probability). Furthermore, it is often unclear whether the probability is observation-dependent (Pcog) or relative frequency for the overall range of observations (Poverall). Therefore, we have four types of probability: internal Pcog, internal Poverall, external Pcog, and external Poverall (

Table 1). (The mathematical relationship between Pcog and Poverall in the CS model is presented by Nakajima [

5].

Given an organism, such as an insect. The probability of encountering a particular mate after a given insect’s cognitive action is internal Pcog, while the frequency of encountering potential mates during its lifetime is internal Poverall. For an ecologist who observes the insect, the probability of the insect’s encountering a particular mate after a given observation about the insect is external Pcog, while the frequency of the insect’s encountering potential mates during its lifetime (by the ecologist’s overall observation) is external Poverall; this value may be the same the internal Poverall if the ecologist’s overall observation is correct. The distinctions between these four types of probability can apply to any cognizer, living or nonliving [

5].

Notions of the internal and external probabilities are naturally extended to entropy and the amount of information, either of which uses the probability concept (

Table 1). Entropy (H) is derived from a probability distribution: H = ∑ P

i log

2 P

i; “

i” indicates event

i. Accordingly, depending on probability type, we can distinguish between four types of entropy (H): internal Hcog (e.g., the entropy of ball colors taken by a particular kind of player’s action), internal Hoverall (e.g., the entropy of ball colors taken out by the player’s various kinds of action in the game), external Hcog, and external Hoverall. Internal Hcog measures the uncertainty of events occurring under a given cognition, and Hoverall measures the uncertainty of the subject-dependent environment, which is interpreted as the entropy of umwelt (

Section 5.5, [

43])

Similarly, the amount of information (I) (do not confuse with “information”), is given by I = Hbefore - Hafter,

where Hbefore and Hafter are entropy values before and after receiving the datum (calculated from Pcog distributions) or those before and after interactions among system components (calculated from Poverall distributions) of events or states (

Appendix B for details). Accordingly, depending on the four types of entropy, the amount of information (I) includes internal Icog, internal Ioverall, external Icog, and external Ioverall.

Table 1.

Four types of probability, entropy, and amount of information.

Table 1.

Four types of probability, entropy, and amount of information.

5.4. Cognizers vs. Demons

Maxwell [

44] devised a famous thought experiment of generating order using a vessel divided into two portions (

A and

B) and a “being” (later called Maxwell’s demon). There is a small hole in the wall that divides them. The being can see the individual molecules and opens and closes this hole to allow only the swifter molecules to pass from

A to

B. Only the slower ones pass from

B to

A. “Without expenditure of work,” the being will, thus, raise the temperature of B and lower that of

A, in contradiction to the second law of thermodynamics. The being is similar to the player in Experiment

B (section 5.2). However, unlike the demon, organisms are an open system working thermodynamically, with varying properties.

The CS model conceptualizes material entities as cognizers characterized by specific discriminability and selectivity. Therefore, we can interpret the demon not as a physical entity but as a perspective shift, asking what occurs if molecules are endowed with certain selective discriminative properties and interact with one another, unlike molecules in the ideal gas. Molecules are cognizers with varying such properties (or abilities). They are not conscious but rather doing related state changes based on their physical or chemical properties. Furthermore, unlike human players in our thought experiments, atomic or molecular cognitions are not semiotic. Monod [

31] states that ‘it is by virtue of their capacity to form, with other molecules, stereospecific and noncovalent complexes that proteins exercise their “demoniacal” function.’ (see [

45] for a related argument).

5.5. Environment and Subject-Dependent Environment

Using previous thought experiments, we can distinguish between the environment and subject-dependent environment. In each experiment, a box containing balls is the environment, which is the same for any player with the same box. The environment of a focal entity refers to an entire set of entities in the system from a perspective of an external observer or the meta-observer. In contrast, we can recognize another concept of the surroundings. Different players may have varying preferences for color, finger size, morphology, and behavioral properties. According to players’ characteristics and properties, such as discriminability and selectivity, the probability distributions of events, epistemic or ontic, vary according to players’ properties. Such an event set with a particular probability distribution characterizes the subject-dependent environment. This aspect of surroundings has been conceptualized as “umwelt” (plural: umwelten) by Jakob von Uexküll [

46], who distinguishes umwelt from “umgebung,” similar to “environment” in the above sense. Given two players, for example, in the third experiment, one prefers red and the other orange with similar discrimination ability, the probability distribution of events must differ to them although they share the same “environment.” Similarly, in Experiment

D, they will experience different probability distributions if they have different semiotic actions.

Uexküll developed the concept of the function-circle (or functional circle): “Every animal is a subject, which, in virtue of the structure peculiar to it, selects stimuli from the general influences of the outer world, and to these it responds in a certain way. These responses, in their turn, consist of certain effects on the outer world, and these again influence the stimuli. In this way, there arises a self-contained periodic cycle, which we may call the function-circle of the animal” [

46,

47]. Here, to avoid confusion in terminology, we should note that “selects stimuli” does not correspond to “selection” in the CS model, but rather the “choice of the states to be discriminated.” In this function-circle process, the focal subject and external entities interact with one another in specific ways, depending on their own properties. This function-circle process involving the sensing and acting loop produces the surrounding world, called an “umwelt” for the organism, in which the subject experiences a particular set of events at particular probabilities. Sagan [

47] points out that ‘Uexkull insists that natural selection is inadequate to explain the orientation of present features and behaviors toward future ends-purposefulness. … Natural selection is an editor, not a creator’. Natural selection does not create adaptation; instead, it tests adaptations, leaving some as the basis for additional adaptations modified by new semiotic cognitions constructed by physical and chemical cognitions.

The “subject-dependent environment characterized by an event set with a particular probability distribution” can be understood as a particular distribution of encounter probabilities with various external entities, such as physical and chemical things, prey, predators, parasites, symbionts, etc. [

2,

3]. Such a distribution characterizes a relational position with other entities in an ecosystem, that is, an ecological niche [

13,

14,

15]. Niche describes the position of an organism relative to abiotic (physical and chemical) entities and organisms of the same and different species, from an externalist perspective (i.e., from the ecologist’s viewpoint); umwelt describes the position from the internalist perspective, focusing on how it arises from the semiotic property of a subject organism.

Niche construction theory [

49] claims that organisms are active agents that construct their environment to be suitable for their survival and reproduction, like a thermodynamic engine working to produce less entropic states by consuming free energy. This claim is partly agreeable. However, as demonstrated in the thought experiments, all entities in the world actively determine their states according to their properties. The CS model suggests that organisms cannot fully construct niches; instead, they participate in constructing their niches. In other words, niches are

generated by intercognitions among living or nonliving cognizers in an ecosystem. For example, beavers build dams and lodges for survival and reproduction, such as protection from predators, holding food, and mating. A beaver dam or lodge is constructed from sediment, rocks, sticks, etc. [

50]. They must be manageable for beavers. Concerning a place in the food web in an ecosystem, Elton describes: “Animals have all manner of external factors acting upon them—chemical, physical, and biotic—and the “niche” of an animal means its place in the biotic environment, its relations to food and enemies” [

13](Chap. 5). Suppose that organisms of species

Y eat species

X as prey; they (

Y) are also eaten by organisms of species

Z, forming a food relation:

X-Y-Z. The position of Y in the food relation characterized one aspect of

Y’s niche. Such a position is not constructed by the focal organisms (

Y), but is instead generated by intercognitions of ecosystem components; they all participate in shaping a food web structure.

6. Cognizers in the World

6.1. Overview

The concepts of “information,” “event,” “measurement,” and “observation” are reduced to the idea of cognition in the CS model. Therefore, explicit mathematical formalism is essential for avoiding the risk of replacing what we try to explain with another vague concept that requires explication.

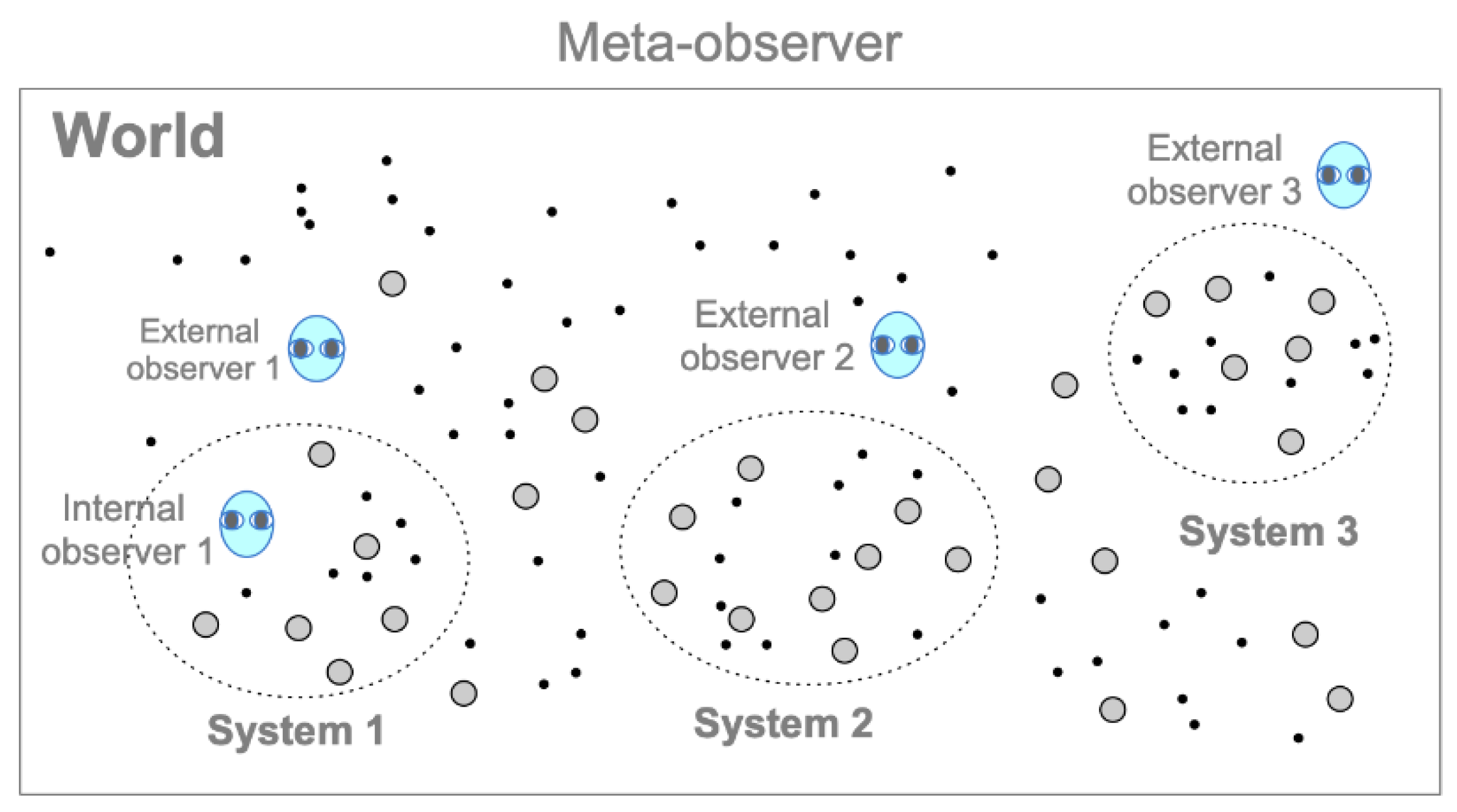

The meta-observer (the model constructer) describes the world that is not a member of the world, standing nowhere and nowhen (Fig. 3). The world comprises cognizers. The world is closed, but systems are open to the outside (If there is only one cognizer, it is the world itself). Cognizers are entities that cognize other cognizers by changing states over time according to their properties. Cognizers may or may not have hierarchical structures composed of sub-cognizers (cognizers at the lower levels of nested hierarchy). Cognition is a related state change characterized by the hierarchical level of a cognizer, such as physical, chemical, and semiotic cognitions (

Section 4). A single cognizer composed of sub-cognizers (e.g., a molecule made of atoms, an organism made of cells) may be called a “cognizer system” (no “s” for cognizer) when the cognizer is described in relation to sub-cognizer.

Figure 3.

The framework of the cognizers system (CS) model. The meta-observer describes the world, which is deterministic. The world comprises cognizers. Dots and gray circles indicate cognizers that perform physical and chemical cognitions; the internal and external observers (1, 2, 3) indicate cognizers (living systems, not restricted to humans) who perform semiotic cognitions. A system of cognizers is called a cognizers system. Systems 1, 2, and 3, respectively, show a subset of cognizers at a focal level that the meta-observer can demarcate as a “system”.

Figure 3.

The framework of the cognizers system (CS) model. The meta-observer describes the world, which is deterministic. The world comprises cognizers. Dots and gray circles indicate cognizers that perform physical and chemical cognitions; the internal and external observers (1, 2, 3) indicate cognizers (living systems, not restricted to humans) who perform semiotic cognitions. A system of cognizers is called a cognizers system. Systems 1, 2, and 3, respectively, show a subset of cognizers at a focal level that the meta-observer can demarcate as a “system”.

The meta-observer can demarcate a subset of cognizers at a focal level as a “system” (called a “cognizers system”), whose members are chosen by the degree of cohesiveness due to inter-discriminative cognitions between cognizers (System 1, 2, 3 in Fig. 3). “External observers” (LSs, not restricted to humans) are cognizers that perform semitotic cognitions of target systems from the outside. By definition, the influence of external observers on the observed system is irrelevant or negligible. For example, experimenters in classical mechanics have been treated as external observers. Note that experimenters in science usually have a dual nature: they are an external observer and simultaneously the meta-observer of a theoretical model. Internal observers are cognizers who perform semitotic cognitions within a system. In this case, the observers observe “their environments” interacting with themselves (e.g., experimenters in quantum mechanics, LSs in an ecosystem). Note that all entities within and without systems are cognizers, that is, physical, chemical, or semiotic cognizers, depending on their hierarchical structures.

To exemplify the above, Experiments

A to

D in

Section 5 can be described as a cognizers system (e.g., system 1 in Fig. 3) composed of a player (“internal observer 1”), balls, and a box. Other entities, such as molecules in the air, can be included in or excluded from the system depending on whether the air conditions affect the behavior of players and balls. An external observer cognizes them through semiotic cognitions without affecting the play.

In the CS model, the meta-observer defines the world as deterministic. Therefore, the temporal sequence of the world must be such that the current state determines only one succeeding state owing to the rule of the world. However, it is worth noting that cognizers systems are not necessarily deterministic because they are open to the outside in the world. A given cognizers system is deterministic only if it is the world. For example, we can define a deterministic system by providing only two cognizers, cognizer A and the rest of the world (i.e., its environment).

The hierarchical extension of “cognition” to all levels of the material world provides a monistic view that

only cognizers exist. Cognizers are models for real entities constructed by a meta-observer, just as elementary particles, quantum fields, and matter in Newtonian mechanics are all models for reality, which have been created and developed with modifications in science. According to [

51], measurement can be categorized into internal and external types: ‘Internal measurement is inherent in realization of a particular pattern of interaction between an arbitrary pair of interacting bodies in the absence of an external observer. Such an internal measurement is ubiquitous in any material system.’ Matsuno's concept of “measurement” aligns with “cognition” defined in the CS model, as it aims to integrate epistemic and ontic state determinations.

6.2. Cognizers System Model

Let us consider a simple case in which the world has only one system that comprises two cognizers, C1 and C2, with state sets C1 and C2, respectively. Cognizers’ names are denoted in italics, with state sets in boldface. C2 is the environment of C1 and vice versa.

As illustrated in Fig. 4(A), the temporal state sequences of C1 and C2 are given, respectively, as

c10, c11, c12, …,

c20, c21, c22, ….

The entire state sequence is given as

where c1i ∈ C1; c2i ∈ C2; (c1i, c2i) ∈ C1×C2.

In the model, temporal sequences are not mere chronicles but are determined by cognitions between cognizers. Cognition is defined as the determination of a succeeding state from the current state according to a deterministic rule called a “cognition function,” which was the same that originally called “motion function” in previous studies published by the author; however, “cognition function” is used in this paper because of consistency.

C1 (in c10) cognizes C2 (in c20), changing to state c11. Similarly, C2 (in c20) cognizes C1 (in c10), changing to state c21, as shown in Fig. 4(B). The state changes in cognizers are determined by their cognition functions, fc1 and fc2 for C1 and C2, respectively, where fc1: C1×C2 ➝ C1; fc2: C1×C2 ➝ C2 (“×” denotes the direct product of sets; “➝” denotes mapping). fc1(c10, c20) = c11, fc2(c10, c20) = c21. Each cognizer is identified with the cognition function, fci, and the state set, Ci.

Therefore, seq. 1 is described as

(c10, c20), (fc1(c10, c20), fc2(c10, c20)), …

Defining (fc1(x, y), fc2(x, y)) ≡ (fc1, fc2)(x, y) ≡ F(x, y), seq. 1 is represented as

which can be written as

u0, F(u0), F(F(u0)), …, Fn(u0), …,

where

u0 = (c10, c20),

F:

U ➝

U,

U ⊂

C1×

C2; in general,

U ⊂ ∏

Ci, where “

i” denotes component cognizers.

F is the cognition function of the world,

U, with the state set

U. The state changes of the world are, therefore, isolated because it has nothing outside to cognize, which changes in states through internal cognitions among components. It may be controversial to call

F a cognition function since it has nothing to cognize; however, we call it a special form of cognition function in that

F is constituted by cognition functions of components, such as

fc1, fc2, …

Figure 4.

(A) cognizers system comprising only two cognizers, C1 and C2, in the world. (B) Related state changes in C1 and C2 by cognition. (C) Determination (selection) of a succeeding state narrow down the relationship to the other cognizer, (D) If C1 cannot distinguish between various states of C2, namely c21 and c2i', then C1 will have uncertainty about the states of C2 that occur after the cognition c1i ⟼ c1j.

Figure 4.

(A) cognizers system comprising only two cognizers, C1 and C2, in the world. (B) Related state changes in C1 and C2 by cognition. (C) Determination (selection) of a succeeding state narrow down the relationship to the other cognizer, (D) If C1 cannot distinguish between various states of C2, namely c21 and c2i', then C1 will have uncertainty about the states of C2 that occur after the cognition c1i ⟼ c1j.

6.3. Selectivity and Discriminability of Cognition

The cognition function for each cognizer represents how it changes a current state in relation to others’ states in the world, i.e., selectivity and discriminability (

Section 4). Determination of a succeeding state represented by a cognition function, implies the selection of one succeeding state (e.g.,

c1j), which narrows down the relationship to the other cognizer, represented by a subset of the direct product

C1×

C2, specifically "

(c1j, ?)" as illustrated in Fig. 4(C). The full determination is completed by all component cognizers.

Any cognizer cognizes all other cognizers wherever they exist. Cognition includes discrimination and nondiscrimination without violating the causal principle. Discrimination refers to changing from a given state to different states against different environmental states. Suppose two or more different environmental states occur, e.g., c2i, c2i’ when a focal cognizer is in a given state, c1i. When fc1(c1i, c2i) ≠ fc1(c1i, c2i’), it is called that C1 in c1i discriminates between the environmental states, c2i and c2i’.

Discriminability affects the uncertainty in events occurring to the cognizer: If C1 does not discriminate between different environmental states, c2i and c2i’; i.e., fc1(c1i, c2i) = fc1(c1i, c2i’), C1 will face uncertainty about the environment, fc2(c1i, c2i) or fc2(c1i, c2i’), as shown in Fig. 4(D). If C1 discriminates between them by changing different states against C2’s different states, C1 will experience a unique C2 state after the cognition (c1i ⟼ c1j). Discrimination reduces the uncertainty of events. However, LSs should ignore unimportant differences and process other differences relevant to maintaining favorable relationships externally and internally.

“Discrimination” refers to the discrimination between different states of a given entity, not between the presence and absence of a target cognizer (in the above case, C2) within the system. However, we can represent this presence/absence case as a discrimination between the positional states of the cognizer (C2) within the locality and those outside the locality.

6.4. Causal Principle (the Principle of Causality) and Freedom

“Causality” refers to the rule-based determination of a succeeding state from a previous state of the world. The “causal principle” (identically, the “principle of causality”) postulates that, given a state of the world, the successor state is uniquely determined by the property of the world as a determination rule from a current world state (Do not confuse “causality” with “causation”). This is called causal determinism. No external agent determines the changes in the cognizer’s state. It is cognizers that determine the world state. Their behavior is not free from others’ states, but they each participate in world dynamics by determining (selecting) their succeeding states based on their properties.

The causal principle is a metaphysical assumption. It is metaphysical because this principle cannot be falsified empirically [

4]. Scientific theories may or may not believe it. The principle is as follows: Given two states of the world,

ui and

ui’ (

ui, ui’ ∈

U). If

ui =

ui’, then

F(ui) =

F(ui’). That is, given a state of

U, only one state succeeds from this state. Indeterminism allows the occurrence of

F(ui) ≠

F(ui’) when

ui =

ui’, indicating that different states can follow the same state.

This principle can be expressed equivalently in terms of the cognizers that comprise the world. Consider a focal cognizer (C1) and its environment (E), the cognition functions of which are fc1 and fe, respectively. The environment is a cognizer, which may be a complex of cognizers external to C1. If (ci, ei) = (ci’, ei’), where ui = (ci, ei) and ui’= (ci’, ei’), then (fc1(ci, ei), fe(ci, ei)) = (fc1(ci’, ei’), fE(ci’, ei’)), that is, the successor states of C1 and E are respectively the same. Indeterminism allows the occurrence of fc1(ci, ei) ≠ fc1(ci’, ei’) when (ci, ei) = (ci’, ei’), indicating that different C1 states can follow the same C1 and E states (the same case is also allowed for E). In the above representation, F: U ➝ U; fc1: C1 × E ➝ C1; fe: C1×E ➝ E.

6.5. State and Event

State and event are different concepts. The meta-observer defines the states that can discriminate every state from the others. An event is a cognition, such as ci ⟼cj, of the environment by a cognizer. Therefore, events are subject-dependent, which can be identified relative to a subject cognizer. When a subject cognizer is a molecule, it cognizes (i.e., changes in state in relation to) other cognizers such as subatomic, atomic, and molecular entities. In this case, cognition is an event that occurs to this molecule. A focal cognizer may be a living cell or an organism; events occurring are nothing but their cognitions.

A cognizer may cognize two or more states of the environment as the same. In this case, the same event can occur for the cognizer against various environmental states (e.g., “heads-up” in coin tosses is the same event for an observer, whereas “heads-up” includes different coin states such as positions it lands on the ground).

Unlike the meta-observer, cognizers cannot directly identify the states of the environment (or other cognizers); they can identify them by a special kind of cognition called “measurement”, which is a related state change occurring from the same baseline state (see

Section 7).

Cognizers are not something existing in the physical space as a container; instead, they are the state spaces (Ci) constituted by their cognition functions manifesting their properties that relate each state with others within and between state sets (Fig. 4(A)).

Ci may not necessarily be described as a metric space in which the distance between two states is defined. However, we can implicitly define the distance between two states (c1i and c1j) of a cognizer by fc1(c1i, c2i) = c1j. That is, the locality (neighborhood) for a given cognizer’s state can be defined by a subset of states to which it can change by one or a small number of cognitions in a system.

6.6. Causation (Cause-Effect Relationship)

Causation is a particular type of relationship in state change between two entities. In the CS model, the cause-and-effect relationship or identically “causation” refers to discriminative state changes (“effects”) against different external states (“causes”). Formally, ci ⟼ cj or cj’ against ei or ei’, respectively (cj ≠ cj’; ei ≠ ei’). Non-discrimination is non-causal or “ignoring.” Formerly, ci ⟼ cj against ei or ei’, respectively. For example, a rolling ball changes its velocity when it collides with another ball. In this case, the first ball discriminates (as an effect: cj or cj’) between different states of the second ball (as a cause: ei or ei’), indicating the second ball causes the velocity change of the first ball. Similarly, a receptor protein changes its molecular configuration when it binds to a ligand. In this case, the protein discriminates (as effects) between different states (as causes) of the ligand, indicating that ligand binding causes the receptor’s configurational change as an effect.

Causation does not indicate a necessary connection between a “state change” (effect) and an “external state” (cause); instead, it refers to the discriminative relationship between them. Therefore, in the above example, causation may include the opposite combination: ci ⟼ cj against ei’, and ci ⟼ cj’ against ei (note the differences in underlined states). For example, a car driver may stop (or go) against a red signal and go (or stop) against a blue signal. Both cases represent causation in the driver’s state changes (stop or go) against external (signal) states. However, their connections are not defined by the discriminability of cognition function. It is “causality,” not causation, that refers to a necessary connection between a given state (ci) and a succeeding state (cj) for a system component under a given environmental state (ei), which is the selectivity aspect of determination by the cognition function (fc1).

6.7. Principle of Local Causation

The principle of local causation asserts that causal effects can occur only in the locality, denying action at a distance. This is a standard assumption in the physical world (the principle does not deny nonlocal correlation), although the local causation principle is optional in the CS model. Locality as a relation between

different cognizers can be defined using the discriminability concept. Based on the principle of local causation, cognizers do not discriminate between different states of cognizers that are distant (non-local) in position. This is based on “causation as a discriminated-discriminating relationship (see below). State correlations are generated by discriminative cognitions by component cognizers. As described previously (

Section 4), under the principle of local causation, semiotic cognition plays a vital role in discriminating between distant cognizers, mediated through state correlations among cognizers.

6.8. Hierarchical Structures of Cognizers Systems

LSs form a hierarchical organization in a nested fashion [

52,

53]. We have not reached a consensus on how the living world is hierarchically organized, which varies according to researchers depending on their purposes. The nested hierarchical structure is based on part-whole relations. Nakajima [

11] clarified the distinction between two types of part-whole relations, synchronic and diachronic part-whole relationships, which have often been confused and not distinctly recognized in the literature.

The synchronic part-whole relation is a standard one, which refers to a relation in which the whole is composed of parts synchronically; parts continue to exist without appearing or disappearing over time. The representation of a cognizers system comprising C1 and C2 (or E) is synchronic.

However, in LSs, such as single-cell or multi-cell organisms, constituent molecules are renewed through catabolism and anabolism, exchanging atoms and molecules across the membrane with the surrounding medium. This process has been formalized as autopoiesis [

54,

55,

56,

57]. The “processes maintaining a particular organizational pattern” by renewing constituent lower-level components can endure certain periods of time and can be each recognized as a “diachronic whole” generated by transient entities as its parts. Synchronic cells are similar to frozen cells, whereas living cells are diachronic cells, each of which retains a specific identity of the process generated by the generation and degradation of parts. Such a process can be described as an entity (cognizer) with a new state space, that is, the density distribution of atoms and molecules. In other words, a living cell can be described as a cognizer that is synchronically composed of sub-cognizers, such as populations of particles that exist in their density spaces. This description is similar to the field concepts in physics [

11].

Unlike Leibniz’s Monads, the CS model provides no fundamental cognizers as the most basic atoms of the world. Monads are the basic units (atoms) of the metaphysical universe. Cognizers can be defined relative to other cognizers in a hierarchical manner. Additionally, unlike cognizers, Monads are causally closed to external entities: ’the natural changes of the Monads come from an internal principle since an external cause can have no influence upon their inner being.’ [

58](Sect. 11).

7. Internalist Model of Semiotic Cognition toward Unification of Matter and Mind

7.1. Discrimination and Measurement by Inverse Causality

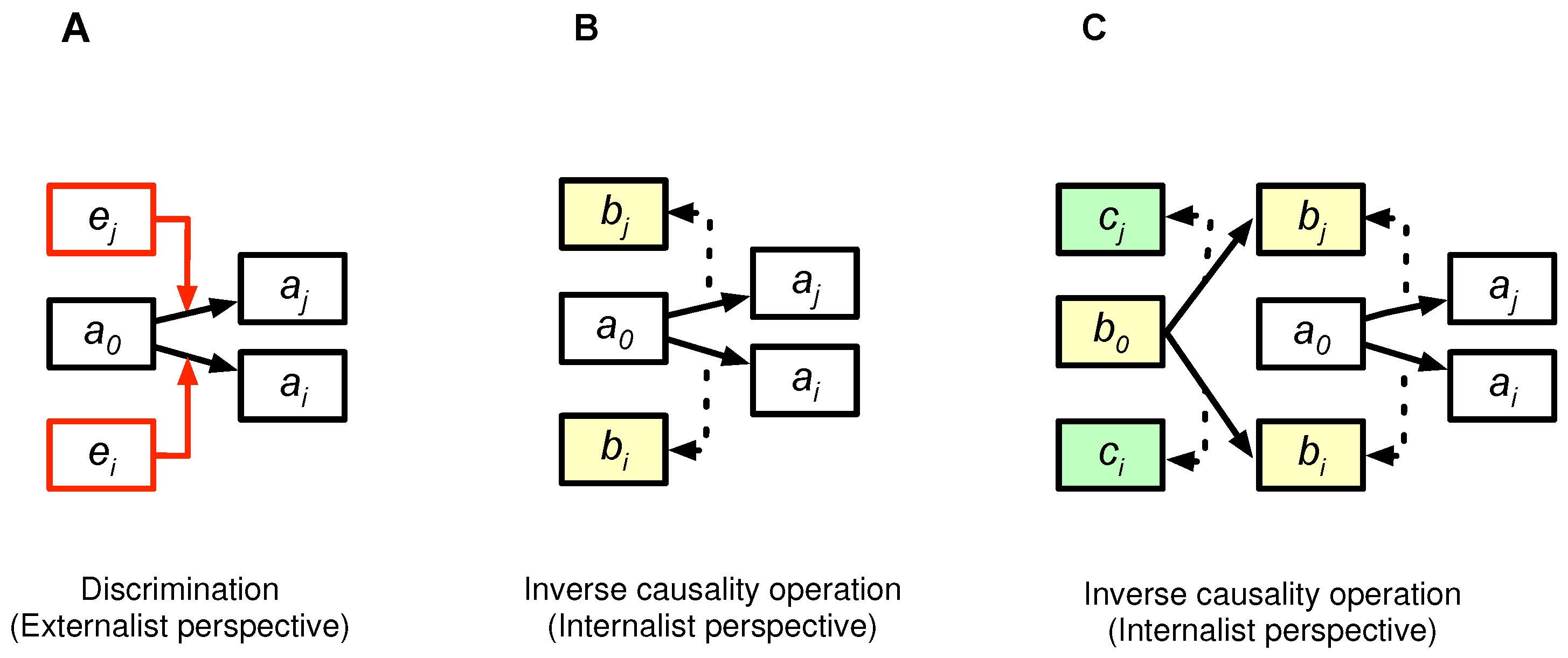

LSs must respond to external states relevant to survival while ignoring others. Furthermore, LSs are blind to distant external states relevant to their survival under the principle of local causation (here, “states” means its relative states to the subject, not absolute). For example, the photoreceptor cells of an organism discriminate between particular states of the electromagnetic field by receiving photons. However, it is necessary to discriminate between the states of something else mediated through photons in correlation in the field. For these tasks, LSs must (i) measure the external states (i.e., the states of the environment that are composed of the states of individual entities) and (ii) generate symbols that signify the external states, local or global, based on which they change the effector states. This function requires a device for measuring the relative states of the environment, called the “measurer,” and a structure for making symbols for the states based on physical and chemical cognitions, through which the states are interpreted to respond.

The ability of the related state changes in physical and chemical cognizers enables them to discriminate between different external states. In Fig. 1(B), from an external observer’s perspective, discriminative state changes (xi ⟼ xj or xj’) of a given cognizer measure the external states, ei and ej, under the condition that they occur from the same state (xi). Therefore, xi ⟼ xj is caused by ei while xi ⟼ xj by ej’. However, this is not viewed from a subject LS. No LS can observe itself and the environment from the outside as an external observer. The environment is hidden from the LS. They must solve the problem of escaping solipsism, a philosophical doctrine that only I exist. How can LSs know the external reality by distinguishing external states from internal ones occurring in hallucinations or dreams?

One might answer that it is a sensor that detects external reality. However, this is unsatisfactory because the sensor conceptually presupposes the existence of the objects to which it responds from an externalist perspective. What guarantees that the sensor’s state changes (xi ⟼ ?) indicate external states? Despite its importance, few studies have addressed this problem.

7.2. Semiotic Cognition by Inverse Causality Operation

Measurement by inverse causality solves this problem [

6,

9,

10]. “Inverse causality” is an epistemic principle operating in a subject system to internally produce symbols that signify past states of the external reality hidden from the subject (note that epistemic/ontic distinctions are unified as cognitive in the CS model). Inverse causality is not “reverse causation,” “retrocausality,” or “backward causation,” asserting that future (or present) states affect past states or that their effects produce causes.

To understand inverse causality, we start with the unique successor principle, asserting that any element in a sequence has only one successor. Formally, if

xi =

xi’, then

G(xi) =

G(xi’), where

G(xi) and

G(xi’) are the successor elements of

xi and

xi’, respectively. This principle is applied to any sequence of elements, but is identical to the causal principle (

Section 6) when it is the sequence of a temporal state change in a material system. The contraposition of the principle in temporal state sequences is called “inverse causality”; If

G(xi) ≠

G(xi’), then

xi ≠

xi’. Inverse causality asserts that any two different states have different predecessors: If

G(xi) ≠

G(xi’), then

xi ≠

xi’.