1. Introduction

Indigenous People (IP) across the globe share an intimate connection with their lands, territories, and resources which we hereby refer to as the Indigenous Socioecological System (ISES) and formally define for the purpose of this paper as

A system that encompasses the interactions between Indigenous peoples and their surrounding environment. It includes the natural resources that the people rely on, such as land, water, and wildlife, as well as the cultural and spiritual values that they attach to these resources. ISESs are often characterized by their long-term sustainability, as Indigenous people have developed sophisticated knowledge and practices for managing their resources [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

The key features of the ISES include the following:

They are place-based: ISESs are rooted in a specific location, and the knowledge and practices that sustain them are adapted to the local environment.

They are holistic: ISESs view the environment as a complex system, and they take into account the interconnectedness of all its parts.

They are sustainable: ISESs have been able to sustain themselves over long periods, even in the face of change.

They are resilient: ISESs have the ability to adapt to change, and they can recover from disturbances.

They are equitable: ISESs are often characterized by a fair and equitable distribution of resources [

3].

Perhaps an essential facet warranting the exploration and understanding of the intimate relationship that exists between the Indigenous Peoples and their Socioecological System is the concept of Kincentric ecology; a prevailing paradigm inherent to many Indigenous communities. Kincentric ecology, a deeply rooted and holistic worldview, permeates the cultural tapestry of numerous Indigenous societies worldwide [

7,

8,

9,

10]. This perspective, in stark contrast to the prevalent anthropocentric ideologies of contemporary Western societies, emanates from a profound comprehension of the intricate interconnections binding all living entities. In the framework of kincentric ecology, human beings are recognized as integral components of a broader ecological network, redefining their role as stewards and active participants within the complex web of life [

7,

8,

10,

11]. At the core of kincentric ecology resides a profound reverence for non-human entities. Animals, plants, water bodies, geological formations, and even the minutest organisms are regarded as kin, each endowed with unique agency and consciousness [

11]. This perspective transcends the utilitarian standpoint of nature as a mere resource for exploitation, engendering instead a disposition of veneration toward the environment. The spiritual reverence attributed to various species and natural features manifests through ceremonial observances and rituals dedicated to their honor. Often encapsulated within narratives depicting shared origins, Indigenous communities articulate their profound interrelation with the land, thereby underscoring the unity permeating all life forms.

Integral to the construct of kincentric ecology are the principles of stewardship and responsibility that delineate Indigenous communities' rapport with their environment [

12,

13] This philosophy mandates an intimate familiarity with local ecosystems and adherence to sustainable resource management practices. Indigenous populations embrace the mantle of custodianship, entrusted with the imperative of preserving the health and sustenance of the land for generations to come [

13]. This fiduciary role extends to the interdependence of species, as Indigenous perspectives acknowledge that seemingly minor perturbations can reverberate across ecosystems, exerting consequences upon both human and non-human constituents. The cultural identity of Indigenous communities is inextricably interwoven with kincentric ecology [

8]. Natural landscapes, species, and ecosystems transcend mere physicality, serving as integral components of creation narratives, traditions, and ways of life. These environments and their inhabitants underpin Indigenous self-perception and purpose. As stewards of the environment, Indigenous groups shoulder the mantle of preserving their heritage and safeguarding the equilibrium of nature [

9,

14]. This obligation bears profound spiritual implications, as the well-being of the ecosystem reflects the well-being of the community at large.

On the other hand, the sphere of policy and legal frameworks occupies a pivotal role in molding the course of climate adaptation, resilience enhancement, and sustainability within Indigenous socioecological systems. These frameworks wield the potential to either bolster or impede the capacity of Indigenous groups to tackle the repercussions of climate change and preserve their sustainable practices [

15,

16]. Thus, favorable policies and legal structures must acknowledge the distinct knowledge, entitlements, and practices of Indigenous populations [

3,

17]. They should be aimed at facilitating the complete participation of Indigenous communities in decision-making procedures, enabling them to lend their traditional wisdom and proficiency in safeguarding the ISES [

18,

19,

20]. Furthermore, these frameworks must also be aimed at promoting collaboration among Indigenous communities, governmental entities, and other stakeholders, thus nurturing alliances that fortify the resilience of ISES [

21,

22,

23]. Likewise, effective policies and legal frameworks should furnish avenues for safeguarding the land and resource rights of Indigenous Peoples, assuring their access to ancestral territories and essential resources for sustaining their socioecological systems [

15,

16,

24]. By honoring and safeguarding indigenous rights, these policies can contribute to the enduring sustainability of ISES and ITFS, and the perpetuation of traditional practices often characterized by low carbon footprints and heightened ecological efficacy. In contrast, insufficient or inadequately designed policies and legal frameworks can compromise the resilience and sustainability of ISES. Historically, Indigenous societies have grappled with marginalization and exclusion from decision-making processes, engendering policies that disregard their distinct requirements and priorities [

13,

14,

20,

25]. However, evidence has shown that this has culminated in the dislodgment of indigenous communities, relinquishment of ancestral lands, and upheaval of socioecological systems, thereby intensifying the susceptibility of these communities to the impacts of climate change [

13,

14,

25].

From this background, it can be stated that the influence of policy and legal frameworks on climate adaptation, resilience-building, and sustainability of the ISESs, and in particular ITFS, stands as a pivotal consideration when addressing the predicaments faced by Indigenous communities in the wake of climate change. However, comparative studies analyzing the actual effects of current regulatory and legal frameworks in promoting or hindering climate adaptation, resilience-building, and sustainability of ISESs remain scarce [

26,

27,

28]. This is partly due to the diversity of indigenous peoples, making it complex to compare the impact of legal frameworks on different groups. These issues are often politically sensitive, dissuading or limiting researchers from tackling them. Furthermore, the lack of international collaboration among researchers from different countries hinders comparative research in this field [

27,

28,

29]. This situation severely limits our capacity to identify effective mechanisms to advocate for Indigenous rights, inclusivity, and participation in the formation and implementation of legal and regulatory frameworks. To help address this existing knowledge gap, this research study uses a novel comparative case-study approach to comprehensively explore the distinct challenges faced by Indigenous communities when navigating legal and regulatory frameworks in their efforts to address the impacts of climate and environmental change. Our intended focus on ITFS is crucial for several reasons. Firstly, these systems often embody sustainable and locally adapted practices that have evolved over generations, contributing to ecosystem resilience and biodiversity conservation. Recognizing and supporting Indigenous food systems in policy can enhance overall food security by promoting diverse, nutritious, and culturally appropriate diets. Additionally, these systems play a significant role in preserving cultural heritage and maintaining community identity. Policies that protect and promote Indigenous food systems can foster social and economic well-being within Indigenous communities, contributing to broader goals of social justice and equity. Furthermore, sustainable Indigenous food practices are closely tied to environmental stewardship, aligning with global efforts to address climate change and promote sustainable development.

1.2. Relevance of the Indigenous Traditional Food System (ITFS) within the ISES

Indigenous traditional food systems (ITFS) encompass intricate relationships among people, their environments, and food sources, extending beyond mere sustenance. Rooted in accumulated traditional knowledge, ITFS involve ecological understanding, sustainable harvesting techniques, and spiritual beliefs tied to food sources [

30]. These systems foster social cohesion and cultural identity through shared meals and food-related rituals, reinforcing community bonds and transmitting cultural values [

1]. Emphasizing a reciprocal relationship with nature, ITFS prioritizes respect for local biodiversity, relying on sustainable resource management practices like rotational farming and controlled hunting to prevent overexploitation. Adaptable to local conditions, ITFS enhances resilience to environmental changes [

12,

30]. With diverse food sources, including wild plants, cultivated crops, and traditional processing techniques like fermentation, ITFS offers well-balanced, nutritious diets, standing in contrast to industrialized food systems. However, ITFS faces challenges such as historical injustices, climate change, and the allure of modernization, threatening their continuity. Recognizing the importance of ITFS is crucial, as they provide models for sustainable food production, contribute to environmental and social resilience, promote food security and health, and play a vital role in preserving cultural identity and knowledge for future generations. Understanding and supporting ITFS are essential steps toward fostering sustainable food systems and resilient communities in harmony with nature {3].

The multifaceted and profound significance of ITFS in sustaining indigenous socio-ecological systems is underscored by their diverse contributions across various dimensions. Environmental sustainability is one crucial facet, as these systems embody practices characterized by locally adapted resource management [

31]. Through measures like rotational farming, hunting quotas, and fire management, indigenous communities prevent overexploitation and promote biodiversity, thereby maintaining the ecological balance. The reliance on local resources inherent in these traditional food systems enhances food security, rendering indigenous communities more resilient in the face of external disruptions, such as food shortages or price fluctuations [

12,

14]. Moreover, indigenous food systems play a pivotal role in conservation efforts, serving as custodians of both natural resources and cultural heritage. The intricate connection between these systems and social-cultural aspects is evident, as they are intertwined with indigenous identities and knowledge. Communal activities like food gathering and sharing foster community cohesion, providing a foundation for collective identity and cooperation [

29]. Economically, traditional food systems contribute to sustainability by supporting local economies and livelihoods. From a health and well-being perspective, traditional foods offer nutritional value and a profound connection to the land [

32]. Often incorporating medicinal plants and practices, these food systems promote holistic health within indigenous communities.

Despite these merits, the challenges stemming from the historical impacts of colonization, the specter of climate change, and the influence of modernization pose significant threats [

29]. These challenges manifest in the form of potential food insecurity, cultural erosion, and adverse health and environmental outcomes. Recognizing and addressing these challenges is imperative to safeguard the resilience and vitality of indigenous traditional food systems. Thus, effectively navigating the regulatory and legal landscapes while advancing climate adaptation, resilience-building, and sustainability for the ITFS demands a comprehensive grasp of the distinctive challenges and possibilities confronted by indigenous societies [

15,

32]. In the same vein, reviewing and analyzing existing regulatory and legal frameworks in advancing climate adaptation, resilience-building, and sustainability of ITFS can provide insights into effective policy formulation that facilitates the adaptive capacity of the Indigenous People to climate change impacts. Further, this can inform global commitments and efforts in combating climate change by enhancing sustainable lifestyles and meeting sustainable development goals.

1.3. Objectives of this research

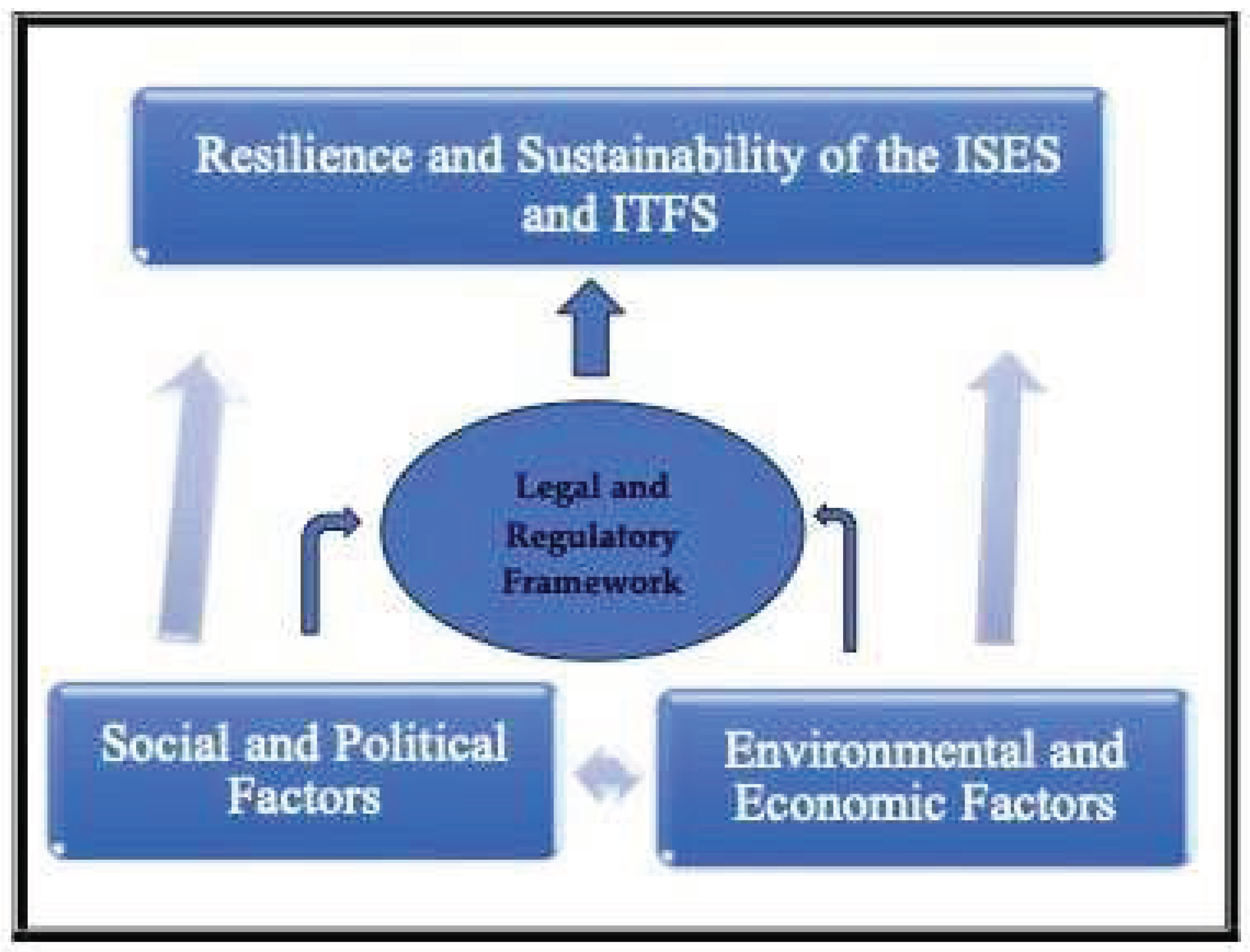

By analyzing the influence of policy and legal frameworks on ISESs, this research paper aims to discern ways by which favorable policies can effectively bolster Indigenous rights, wisdom, and practices, while also investigating the detrimental effects of poorly designed frameworks rooted in historical marginalization. We further examine the potential for inclusive and culturally sensitive policies that integrate Indigenous perspectives, fostering collaboration and partnerships among diverse stakeholders to develop policies that ensure the continuity of ITFS and the sustainability of ISES. Ultimately, this study endeavors to underline the broader implications of well-crafted policy and legal frameworks in sustaining ISES and ITFS in particular, while preserving ecologically efficient traditional practices with low carbon footprints. The following are the main objectives that serve as the guiding pillars of this comprehensive research paper:

Investigate the impact of existing regulatory and legal frameworks on the adaptive capacity, resilience-building, and sustainability of Indigenous Socioecological Systems (ISES), with a specific focus on Indigenous Traditional Food Systems (ITFS).

Establish a theoretical model for the sustainability and resilience of the ITFS: The main goal of this new theoretical model is to facilitate the integration of IP’s concerns and voices into contemporary policies, and legal, and regulatory frameworks.

Foster dialogue and safeguard rights. The overarching goal is to foster meaningful dialogues among Indigenous communities, policymakers, and stakeholders, with the aim of safeguarding and enhancing the rights and sustainability of ISES, particularly in the face of accelerating climate change and widespread environmental exploitation.

1.4. Methodology

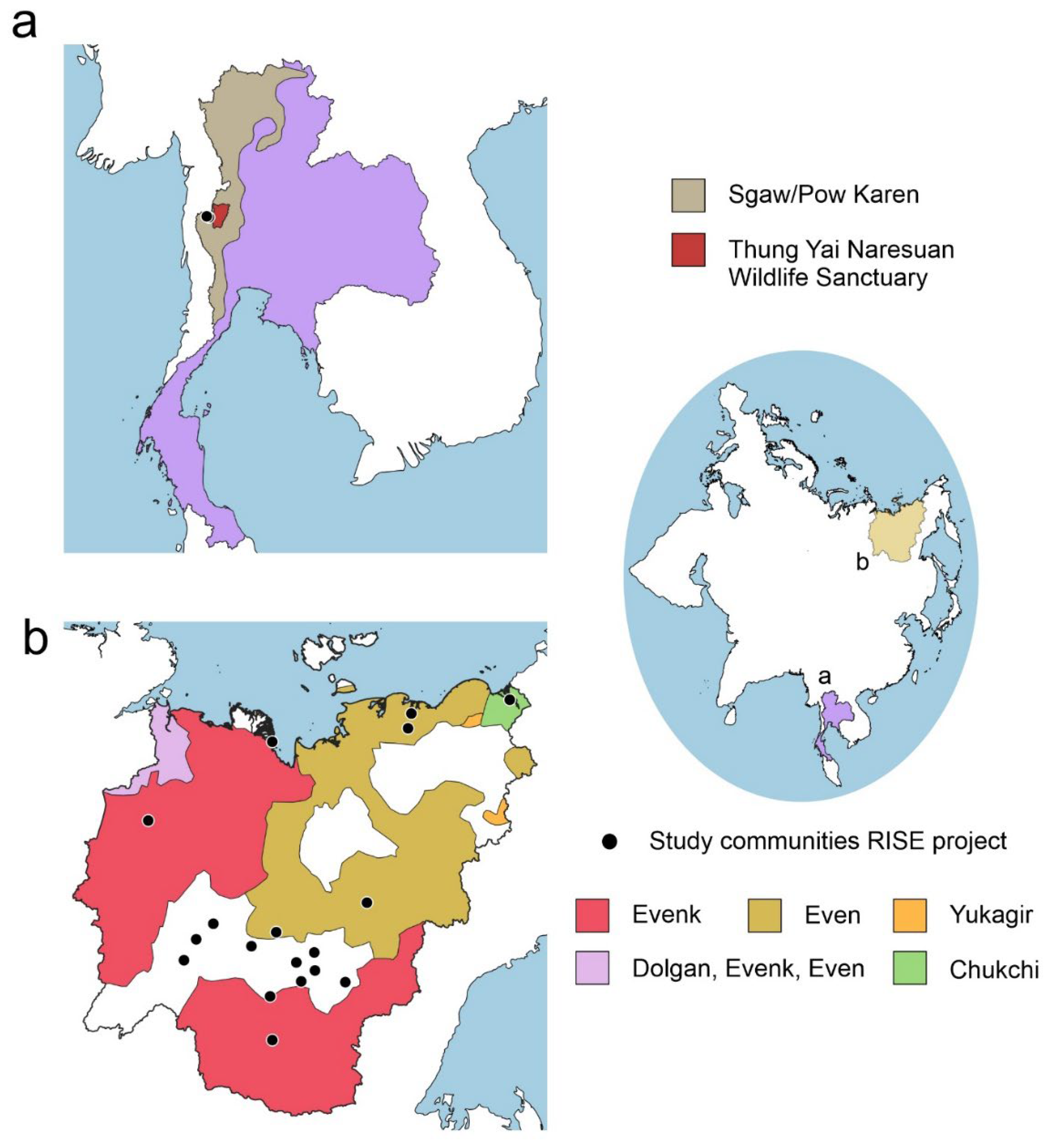

We employ a comparative case study approach to investigate the intricate interplay between legal and regulatory frameworks within Indigenous communities from two distinct geographical and socio-cultural settings: Indigenous communities of Yakutia (Sakha Republic, Russia), including multiple ethnic groups, and the Karen Indigenous People in Thailand (

Figure 1). This approach has been chosen to enable a comprehensive exploration of the multifaceted dynamics that arise from the intersection of legal and regulatory constructs across different socio-cultural and geographical contexts. To this end, we make combined use of desktop research methodology analysis with a focus on existing literature reviews on the topic, national legal and regulatory laws governing the Indigenous territories in our study communities, on-site observations from our ‘RISE’ joint project research [

33] and comprehensive analysis of international Indigenous rights reports. This methodological framework is strategically designed to discern, in a highly refined manner, the nuances of challenges, opportunities, and ultimate outcomes arising from the presence of legal and regulatory frameworks within these unique Indigenous communities. By juxtaposing and analyzing these distinct cases, this comparative inquiry aspires to furnish a comprehensive and insightful understanding of the sophisticated ways in which these legal and regulatory frameworks may shape and influence climate adaptation, resilience enhancement, and sustainable development initiatives within a diverse spectrum of indigenous socioecological systems, spanning diverse cultural and geographical contexts.

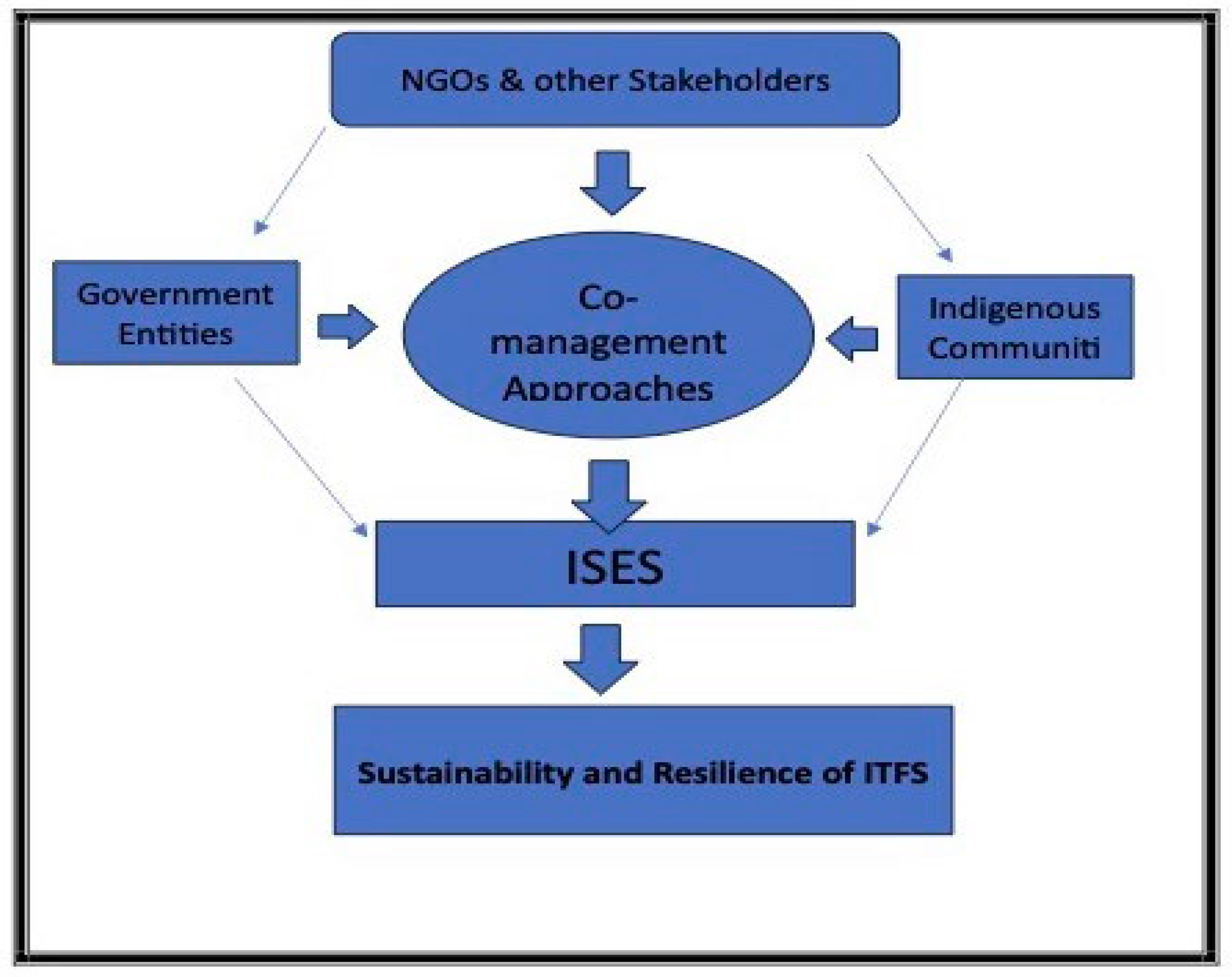

Using these sources of information, this research paper adopts a Political Ecological Theoretical Framework (PETF) to analyze and examine the role of regulatory and legal frameworks in the adaptation and sustainability of the ISES (

Figure 2). Political Ecology examines the intricate interactions between political, economic, social, and environmental factors that shape resource use, distribution, and access [

34,

35]. For our study, Political Ecology provides a lens through which to analyze the power dynamics, socio-political contexts, and environmental implications that can influence the adaptation, resilience-building, and sustainability efforts within Indigenous socioecological systems. We adopt this framework because of its potential to elucidate how policy and legal structures can condition and be shaped by broader societal and ecological contexts, shedding light on issues of indigenous rights, historical marginalization, and unequal resource distribution. Further, PE allows us to delve into the complexities of the interactions between indigenous communities and regulatory and legal systems, revealing the nuanced interplay between local practices, global climate change pressures, and socio-political dynamics that impact the outcomes of climate adaptation and sustainability initiatives.

The PETF is particularly relevant for examining the influence of legal and regulatory frameworks on ISES and climate resilience priorities because of its capacity to unravel the underlying power dynamics, socio-political contexts, and environmental implications that impact the capacity of Indigenous communities to adapt, build resilience, and ensure the sustainability of their socioecological systems. Thus, this approach allows for an examination of indigenous rights, historical marginalization, and unequal resource distribution within the framework of climate resilience and sustainability [

36,

37,

38]. In doing so, it unveils the complexities of indigenous-community interactions with legal and regulatory frameworks and the ways in which these systems can either facilitate or hinder climate adaptation and sustainability initiatives. Ultimately, this approach can inform more equitable and effective legal and regulatory policies that align with the values and needs of Indigenous communities while promoting climate resilience and sustainability within ISESs. Below we discuss three areas where the PETF can be effectively utilized in the context of ISES as applied in our study:

Power dynamics and Indigenous rights: Political Ecology enables the exploration of power dynamics inherent in legal and regulatory structures. These power dynamics can either empower or disempower Indigenous communities in asserting their rights over their lands, resources, and traditional knowledge. It allows for a critical examination of how legal frameworks may perpetuate or challenge historical inequalities and injustices faced by Indigenous peoples.

Socio-political contexts and environmental implications: This framework provides the tools to assess the socio-political contexts in which legal and regulatory decisions are made. It considers how these decisions influence the management of natural resources, land use, and environmental policies, with potential impacts on the ecological integrity of ISES. This understanding is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness and fairness of legal frameworks in achieving climate resilience and sustainability.

Unequal resource distribution and historical marginalization: Political Ecology allows for an analysis of resource distribution within the context of ISES. It helps in uncovering how legal and regulatory systems may perpetuate resource inequities and contribute to the historical marginalization of Indigenous communities. This perspective is essential in advocating for policies that address these historical injustices.

1.5. Recognizing the role of innovative legal and regulatory frameworks in shaping the sustainability and resilience of ISES and ITFS

Properly designed Legal and regulatory frameworks have the potential to play a pivotal role in shaping the sustainability of ISES and ITFS. As discussed in the introductory part of this part the ISES are intricate, interconnected networks of social, cultural, economic, and ecological elements that are profoundly shaped by the relationship between Indigenous communities and their environments. To ensure the sustainability of these systems, it is crucial to understand the impact of thoughtful and carefully designed legal and regulatory frameworks. Below we discuss and emphasize some specific points stressing the need to formulate and implement innovative legal and regulatory frameworks that are based on internationally recognized standards and inclusive of Indigenous people's voices, rights, and freedoms in accessing their traditional lands.

- i.

Land tenure and resource rights. Indigenous communities' ability to manage and sustain their ISES and ITFS depends significantly on secure land tenure and resource rights. Legal recognition of Indigenous land rights is vital as it provides a foundation for sustainable resource management. In many cases, land tenure and resource rights have been eroded or denied, leading to resource exploitation and environmental degradation. Robust legal frameworks that recognize and protect Indigenous land rights can empower communities to steward their lands and resources sustainably [

39,

40,

41,

42]. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) provides a comprehensive framework outlining the collective and individual rights of Indigenous peoples, including their rights to lands, territories, and resources. It emphasizes the importance of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) in decision-making processes that affect Indigenous communities, offering a foundation for sustainable resource management and the preservation of ITFS [

40].

- i.

Traditional knowledge protection. Indigenous communities hold a wealth of traditional ecological knowledge that has been passed down through generations. This knowledge is invaluable for understanding and adapting to environmental changes. Legal frameworks should focus on the protection of TEK, including intellectual property rights for Indigenous knowledge holders. By safeguarding TEK, legal frameworks can promote the continued use of traditional practices that contribute to ISES and ITFS sustainability [

42,

43,

44]. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) recognizes the importance of traditional knowledge, innovations, and practices of Indigenous and local communities in the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity. Furthermore, the Nagoya Protocol, a supplementary agreement to the CBD, specifically addresses access to genetic resources and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from their utilization, providing a legal basis for the protection of ITFS.

- i.

Traditional hunting, gathering, and fishing activities: Legal and regulatory frameworks significantly influence the sustainability and resilience of hunting and fishing activities among indigenous people. In recent decades, global attention has focused significantly on the conservation of biodiversity and wildlife resources. The socio-economic restructuring of hunting, fishing, and gathering practices within many Indigenous communities is facing challenges due to policies introduced by federal governments aimed at conserving these natural resources. In the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), as well as in Russia overall, the state regulation of hunting follows an interdepartmental structure [

45]. The Ministry of Ecology, Nature Management, and Forestry of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) is entrusted with the formation of a regulatory and administrative base, and the Department of Hunting and Specially Protected Territories is the authorized body for organizing activities [

45]. This complex structure necessitates serious coordination among all these entities. A study conducted by [

45] (2021) revealed that despite certain positive advancements in wildlife hunting regulations in the Sakha Republic, which is a common practice among many Indigenous People there are several issues stemming from this complex regulatory structure. These problems include insufficient implementation of the priority rights of small Indigenous peoples to utilize hunting resources and inadequate legislation regarding compensation for damages inflicted on hunting resources due to the economic activities of enterprises impacting the habitats of wild animals. This situation exemplifies a scenario where the traditional local economy and habitat are compromised for the sake of larger enterprise activities, resulting in the loss of the traditional lifestyle of the Indigenous Peoples in this region [

3,

45]. This is an example of poorly drafted policies governing Indigenous territories. Thus, when legal and regulatory frameworks are crafted thoughtfully, these frameworks can foster sustainability by recognizing and respecting indigenous rights, integrating traditional ecological knowledge into conservation strategies, and promoting adaptive management practices. The establishment of territorial use rights, quotas, and seasonal restrictions aligned with indigenous practices can contribute to the resilience of ecosystems and the species targeted. Moreover, a focus on cultural considerations, economic opportunities, and climate change adaptation within legal frameworks can enhance the overall sustainability and resilience of indigenous hunting and fishing activities, ensuring the protection of both cultural heritage and ecological integrity.

- i.

Conservation and environmental management. Legal and regulatory frameworks also influence conservation efforts and environmental management in Indigenous territories. These frameworks can either facilitate or hinder Indigenous-led conservation initiatives. Collaborative approaches that involve Indigenous communities in decision-making processes related to conservation and resource management are more likely to yield sustainable outcomes. Legal recognition of co-management arrangements, where Indigenous communities are equal partners, can enhance environmental stewardship [

40,

42,

46]. Furthermore, legal and regulatory frameworks can foster partnerships and collaborations between Indigenous communities, governments, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) [

47]. Such partnerships can provide essential resources, technical expertise, and funding to support Indigenous-led sustainability initiatives. One notable example is the Māori Resource Management Act of 1991 in New Zealand. This legislation offers Māori people a significant role in the management of natural resources within their traditional territories [

48]. The act's achievements are evident in its effective preservation of Māori cultural heritage and environmental values. The Wairau River Agreement inked in 1999 between the New Zealand government and seven Māori iwi, stands as a remarkable testament to the act's success. This agreement introduced joint management of the Wairau River catchment, where government entities and indigenous iwi collaborated to improve the river's quality and safeguard its biodiversity [

48].

There are many other global examples where innovative legal and regulatory frameworks have led to enhanced resilience and sustainability of both the ISES and the ITFS. For example, the Forest Rights Act (FRA) in India is a landmark legislation that recognizes and vests forest rights and occupation in forest-dwelling Indigenous communities. It empowers communities to protect and conserve forests, promoting sustainable resource management and the continuation of ITFS. Today, the ISES and ITFS in this territory are thriving due to the recognition and implementation of such a robust policy. Similarly, Australia has also its own success story with the Indigenous Land Rights Act of 1993, which grants Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities the ability to assert native title claims over their ancestral lands [

49]. The Mabo decision in 1992 by the High Court of Australia marked a historic moment, as it acknowledged the native title rights of the Meriam people to Murray Island in the Torres Strait. These exemplary instances underscore the power and efficacy of legal and regulatory frameworks in ensuring indigenous participation in the sustainable management of their traditional lands and resources. The outcomes not only contribute to the environmental preservation of these areas but also play a pivotal role in safeguarding the rich cultural heritage and traditions of indigenous communities [

49]. Lastly, we have the Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act 1997 (Philippines): This act recognizes the rights of indigenous peoples to their ancestral domain and self-determination [

50]. The act has been successful in helping to protect the rights of indigenous peoples in the Philippines. One example of the success of this act is the recognition of the ancestral domain of the Dumagat people in the Sierra Madre mountains [

50].

These successful examples vividly demonstrate that it is not only possible but also highly beneficial for national governments to collaborate closely with Indigenous peoples in safeguarding their rights to land territories and respecting their way of life. The cases of the Māori Resource Management Act in New Zealand, the Forest Act in India, and the Indigenous Land Rights Act in Australia underscore that when governments acknowledge and support the active involvement of Indigenous communities in managing their traditional lands and resources, remarkable progress can be achieved. This approach not only ensures the preservation of the environment and Indigenous cultures but also fosters a harmonious and mutually beneficial relationship between governments and Indigenous peoples, ultimately contributing to the sustainability of the ISES and TFS and a more equitable and sustainable society for all.

2. Case study 1: The Karen Indigenous People

2.1. Historical Background

The Karen Indigenous people of Thailand are one of nine officially recognized indigenous ethnic groups in the country. They are believed to have originated in Tibet or Mongolia and migrated southwards through China, to Myanmar and Thailand [

51]. The history of the Karen Indigenous people in Thailand unfolds as a captivating saga spanning over a millennium, characterized by their long migration from faraway lands into the region and the evolution of their distinctive way of life [

52]. Believed to have arrived approximately 1,000 years ago, the Karen people's presence has left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of northern and northwestern Thailand (Tun 2005). Originating from lands beyond Thailand's borders, the Karen embarked on a transformative journey, driven by a myriad of motivations. These included the pursuit of fertile lands for cultivation, escape from political tumult in their places of origin, and the quest for fresh opportunities in a new land [

51]. Upon reaching the hills and dense forests of northern and northwestern Thailand, the Karen founded communities that would become their ancestral homes [

52,

53,

54]. These landscapes not only furnished them with the necessary physical resources for sustenance but also served as the canvas upon which their distinct cultural identity was painted.

The Karen Indigenous people in Thailand are divided into four distinctive subgroups: the Sgaw, Pwo, Kayah, and Toungthu Karen. The Sgaw and Pwo Karen are the two largest subgroups, accounting for around 70% and 25% of the total Thai Karen population, respectively. Here we focus on two Pwo communities (Sanephong and Koh Sadueng) located in the Laiwo subdistrict (Kanchanaburi province) within the Tanowsri mountain range that forms a natural division between Myanmar and Thailand comprising many small hills and narrow valleys (

Figure 2a). Pwo Karen are believed to have moved from China into this area during the 13th century [

55]. These resilient people have inherited a cultural legacy deeply intertwined with the land, preserving their traditional livelihood in distinctively unique ways. Their sustainable circular shifting farming practices, rituals, and beliefs are intimately intertwined with nature and remain still strong today. Traditional livelihoods and food systems continue to provide today essential support for Pow families and communities [

56].

The Sanephong Indigenous settlement, nestled in the breathtaking Mae Hong Son province of Thailand, near the Myanmar border, boasts a rich and storied historical background [

57,

58,

59]. The settlement's origins can be traced back through generations. These resilient people have inherited a cultural legacy deeply intertwined with the land, marked by semi-nomadic traditions and a profound connection to nature. The history of the Karen Indigenous people in Thailand unfolds as a captivating saga spanning over a millennium, characterized by their migration to the region and the evolution of their distinctive way of life [

52]. Believed to have arrived approximately 1,000 years ago, the Karen people's presence has left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of northern and northwestern Thailand (Tun 2005). Originating from lands beyond Thailand's borders, the Karen embarked on a transformative journey, driven by a myriad of motivations. These included the pursuit of fertile lands for cultivation, escape from political tumult in their places of origin, and the quest for fresh opportunities in a new land (Stuart-Fox 1998). Upon reaching the hills and dense forests of northern and northwestern Thailand, the Karen founded communities that would become their ancestral homes [

52,

53]. These landscapes not only furnished them with the necessary physical resources for sustenance but also served as the canvas upon which their distinct cultural identity was painted.

The traditional lifestyle of the Karen people in these regions became intricately woven with the natural environment. They honed their expertise in hunting, gathering, and agriculture, drawing from a profound understanding of the local ecosystem [

58,

60]. Their traditional food systems, deeply rooted in the rhythms of nature, reflected their harmonious coexistence with the land [

56]. Throughout the centuries, the Karen have tenaciously preserved their cultural heritage, passing down their languages, customs, and belief systems from one generation to the next. This enduring legacy has contributed to the rich cultural tapestry of modern Thailand, exemplifying the resilience of indigenous communities and their capacity to adapt and flourish in diverse landscapes [

57,

58,

59,

61]. The Karen people's remarkable history in Thailand serves as a compelling testament to the enduring connection between humans and their environment. It underscores the importance of recognizing and safeguarding the cultural heritage of indigenous communities while also addressing the contemporary challenges they confront in an ever-changing world.

2.2. The introduction of legal and regulatory framework - Colonial era

The onset of the colonial era in the 19th century marked a significant turning point in the history of the Karen people and their ancestral territories. During this period, the Thai kingdom expanded its influence and control over the Karen territories, ushering in a new chapter fraught with profound social, cultural, and political changes [

51,

53,

60]. The Thai government, in its pursuit of territorial expansion and consolidation of power, implemented a series of policies that had far-reaching consequences for the Karen people. These policies were marked by discrimination and a disregard for the unique cultural identity and traditional way of life cherished by the Karen (O’Connor 2014). One of the most salient impacts of Thai colonial rule was the erosion of Karen culture. The imposition of Thai cultural norms and values posed a direct challenge to the Karen's distinct cultural heritage. Efforts were made to suppress the Karen language, customs, and religious practices, aiming to assimilate the Karen into the dominant Thai culture [

62]. This cultural assimilation threatened the rich tapestry of Karen traditions that had been passed down through generations.

Furthermore, land policies introduced during the colonial era exacerbated the challenges faced by the Karen people. Traditional Karen lands, which had sustained their communities for centuries, came under threat as Thai authorities sought to exert control over valuable resources [

57,

58,

59,

61]. Land confiscations and reassignments disrupted the Karen's agrarian way of life, leading to displacement, loss of livelihoods, and social upheaval [

60,

62]. The colonial era also witnessed the Karen people's resistance to these discriminatory policies and the erosion of their cultural identity. They mounted efforts to protect their land, language, and cultural practices, often in the face of significant adversity. These struggles for cultural preservation and land rights would become defining features of the Karen people's history.

2.3. Legal and regulatory framework - post-colonial era

The post-colonial era, following Thailand's independence from French colonial rule in 1949, ushered in a period of continued challenges and discrimination for the Karen people [

52,

62]. Despite the end of colonial rule, the Thai government's policies toward the Karen remained marked by a troubling pattern of marginalization and forced relocation, exacerbating existing tensions between the Karen communities and the central government [

60]. Thailand's newfound independence did not bring about a significant shift in its treatment of the Karen people [

52,

62]. Discriminatory practices have persisted, and the Karen Indigenous communities have continued to face systematic disadvantages in various aspects of life, including access to their land resources, education, healthcare, and economic opportunities. These disparities further entrenched socio-economic inequalities between the Karen and the broader Thai society [

60]. One of the most troubling developments during the post-colonial period was the forced relocation of many Karen people from their traditional homelands to lowland areas [

53,

57,

62]. This policy often carried out under the banner of development and modernization, had profound consequences for Karen communities. The forced relocations disrupted their centuries-old agrarian practices, leading to the loss of land, livelihoods, and cultural connections with their ancestral territories [

60]. Many Karen families found themselves displaced and struggling to adapt to unfamiliar lowland environments [

62]. These forced relocations also had severe repercussions for Karen-Thai relations. They not only intensified existing tensions but also fueled resistance and resentment among the Karen people. Discontent grew as the Karen communities perceived the Thai government's actions as a threat to their way of life and a violation of their basic rights. Consequently, conflict and sporadic insurgent movements emerged as a response to these injustices [

53,

60].

2.4. Implications of existing legal and regulatory frameworks on the ISES and TFS of the Karen Indigenous communities

Historically, the Karen people have faced restrictions on their land rights due to the Royal Thai government's classification of much of their traditional lands as public land (International Crisis Group 2021; Human Rights Watch 2022). Here we delve into examples of some legal and regulatory frameworks in the two Karen communities in our study (Sanephong and Koh Sadueng) and their profound impacts on the ITFS. Firstly, towards the end of the 1930s, there was a growing push by the Royal Thai government to enact policies and laws that were meant for forest and nature conservation in view of the already existing free will of the natural resource use by the Karen IPs. This free will was seen as a fundamental problem to natural resource conservation by the Thai authority, which enacted the Forest Reserve Act in 1941 to designate extensive areas as national forests [

63]. The formulation of this act meant that the Karen IPs were now restricted from accessing vital hunting, gathering, and farming grounds ignoring customary land tenure systems and prioritizing commercial forestry over indigenous Karen practices [

64]. Similarly, the 1961 Land Code Act conflicted with communal land-holding traditions, making it difficult for the Karen to collectively manage their territories for traditional food production (The 1961 Land Code). Concessions for mining and large-scale agriculture further exacerbate the issue by disrupting ecosystems crucial for traditional food sources. This longstanding lack of recognition for customary laws and governance structures significantly undermines the Karen community's ability to sustainably manage their territories, exacerbated by limited representation in decision-making processes [

64].

Water resource management laws and biodiversity conservation laws which have recently been enacted add complexity to the problem, making it challenging for Karen communities to secure water access and restricting traditional practices like swidden agriculture or hunting. This has led to a lot of conflicts between the Royal Thai government and the Karen Indigenous communities particularly within the Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary (TYNWS), where our two study communities (Sanephong and Koh Sadueng) are located. Established in 1974, the history of confrontations and conflicts between the Karen communities and the Natural Park authority within the TYNWS is marked by a complex interplay of socio-cultural dynamics and conservation policies [

60,

65]. These conflicts stem from the establishment of the sanctuary and intensified with the implementation of conservation measures that restrict the traditional practices of the Karen, including swidden agriculture, hunting, and gathering. The Natural Park Authority's imposition of conservation laws has often disregarded the customary land tenure systems and traditional resource management practices of the Karen communities [

65]. These clashes over land use and resource access escalated, leading to forced evictions and displacement of many Karen communities from their ancestral lands within the sanctuary. The abandonment of these originally existing communities resulted from a culmination of confrontations, legal disputes, and the imposition of conservation regulations that disproportionately affected the livelihoods and cultural practices of the Karen people. This historical trajectory underscores the complex challenges at the intersection of conservation efforts and indigenous rights within the Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary [

60,

65].

Furthermore, the 2017 law criminalizing deforestation has been used to unfairly target the Karen people for practicing traditional farming methods that involve land clearance [

63,

66]. This has resulted in arrests and incarceration, further straining their economic and social well-being as their sustenance depends on the forests. In addition, the 2018 law requiring government-appointed village headmen undermines the Karen people's traditional systems of self-governance, eroding their cultural identity and autonomy [

63]. Additionally, restrictions on access to education have led to the closure of Karen schools, forcing children into Thai schools, where they may encounter language and cultural barriers that hinder their educational progress. The declaration of the TYNWS together with the adjacent Huai Kha Khaeng WS as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1991 further exacerbated these problems, reflecting the critical tension between the preservation of natural and cultural heritage and indigenous rights [

60,

65]. According to the nomination document, the people living in these areas are perceived as a threat to the conservation of these sanctuaries, which has led to plans for their resettlement in the near future [

60,

65]. This situation is significant as it raises concerns about how such issues are addressed by international institutions like UNESCO, which are created to preserve natural and cultural diversity and safeguard indigenous rights [

60]. It implies that these international organizations might not always successfully balance these competing interests. The question arises whether these institutions, in their efforts to protect natural spaces and biodiversity, can sometimes overlook or even undermine the very people who have been custodians of these lands for generations [

60]. After all, the indigenous communities living in these regions have historically played a critical role in maintaining and fostering biodiversity. In such cases, the dialogue and collaboration between international institutions, local authorities, and indigenous communities become essential. Therefore, the need to find a balance between conservation and protection of rights while dealing with heritage sites becomes abundantly clear. It is vital to carefully consider these aspects when dealing with such delicate situations. Both the preservation of biodiversity and the protection of indigenous rights are crucial, and one should not be prioritized at the expense of the other. Decisions taken should pay heed to the people directly affected, their traditions, customs, and their historical relationship with the land.

While there have been some recent positive developments, such as the 2019 recognition of the Karen people as an indigenous group, these actions alone are insufficient to address the myriad challenges they face. More comprehensive efforts are needed to safeguard the rights and dignity of the Karen people, including equitable land rights, improved access to education and healthcare, and the eradication of discrimination and violence. Upholding these rights is essential for the Karen people to live with the dignity and respect they deserve within the legal framework of Thailand. Furthermore, understanding the specific impacts of these legal frameworks is crucial for designing effective solutions that promote the resilience and sustainability of the Karen community’s TFS, fostering both cultural preservation and environmental well-being.

3. Case study 2: Indigenous People of Yakutia Region (Sakha Republic, Russian Federation)

3.1. Historical background

While there is a clear distinction between the Indigenous people of Thailand and the rest of the population, in Russia the notion of Indigenous peoples is linked to the size of the population and natural resource use practices [68]. Thus, although about 200 different nations live on the territory of the Russian Federation, the majority being ethnic Russians (Slavic people), only 47 nations are considered by the state to be Indigenous people as officially documented in the register of Indigenous small-numbered peoples, several of which are represented within the Republic of Sakha (

Figure 2b). These are Indigenous nations with populations under 50,000 people and distinct traditional culture and livelihood (see Overland 2005; Donahoe et al., 2008). Of these 47 officially recognized IPs, the Russian legislation geographically groups 40 as ‘Indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East’ (later referred to as Indigenous peoples of the North). These groups of Indigenous peoples often lead natural resource use practices such as reindeer herding, hunting, and fishing [

68]. Other than these officially recognized Indigenous minority groups, several other important ethnic groups live across the Sakha Republic such as the Russian Old-Settlers or Old-Timers (Russkoustinians), descendants of the first European colonists who settled the Arctic shores of Eastern Siberia during the 16th century, or most notably the Yakuts (Sakha People), who are the most populous ethnic group in the Republic of Sakha.

The vast expanse of the Sakha Republic hosts a diverse array of Indigenous settlements, each with its own unique cultural identity and heritage. These remote communities are nestled amidst the breathtaking landscapes that define the Republic [

67]. These settlements are the lifeblood of the Sakha Republic, making substantial contributions to both its economy and cultural diversity. Indigenous residents in these areas have established a deep connection to a range of time-honored activities that have sustained their communities for generations. For many, reindeer herding is not just a livelihood but a way of life that provides sustenance and a profound connection to their cultural heritage. Similarly, fishing along the Lena River is central to their subsistence and traditions, with generations passing down the art of fishing. Furthermore, hunting remains a vital practice, serving not only as a source of nourishment but also as a vessel for preserving traditional skills and wisdom. In addition to their economic contributions, these indigenous communities assume the role of custodians over the natural environment and cultural legacy in Yakutia. Their deep respect for the land and its resources is evident in their sustainable land management practices. They possess a nuanced understanding of the delicate balance required to maintain their ecosystems, often serving as exemplars of responsible resource management [[

68]. Equally noteworthy is their commitment to preserving their cultural heritage. The indigenous peoples' languages, folklore, and traditions are intrinsically tied to their surroundings, reflecting their reverence for the land [

67]. Elders take on the vital role of passing down stories, songs, and rituals to younger generations, ensuring the continuity of their distinctive cultural identities. In doing so, these settlements become living repositories of age-old wisdom and customs, thereby grounding the region's rich heritage firmly in the contemporary world [

68]. In essence, the Indigenous settlements of Yakutia embody not only the resilience of their diverse native populations but also the enduring connection between humanity and the natural world. Their contributions to the economy, cultural preservation, and environmental sustainability are of paramount importance, rendering these communities invaluable not only to the Republic but to the global tapestry of diverse cultures and ecosystems.

Prominent Indigenous people in Yakutia include the Chukchi, Dolgan, the Evenk, and the Russian old-timers. the Sakha, also called Yakut, is one of the major peoples of eastern Siberia of Turkic origin. In the 17th century, they inhabited a limited area on the middle Lena River but progressively expanded throughout Yakutia. Despite the Arctic climate, the Sakha have clung to an economy based on the raising of cattle, and horses, despite their livestock requiring shelter and feeding for a large part of the year. Dairy products occupy a prominent place in their diet, with meat being a part of their daily diet Fishing in rivers and lakes is the second most important economic activity [

68]. Meat, from reindeer herds, wild game, fish, or marine mammals, represents traditionally the main food of the Indigenous groups of the Far North such as Nenets, Dolgan, Evenk, and Chukchi. Meat is consumed raw, from animals that have been freshly killed or merely wounded, as well as cooked (boiled, grilled) and preserved using different techniques such as fermentation and dry-curing. Some groups like the Yukaghir stored meat in the frozen ground. The stroganina is a traditional dish from northern Siberia comprising long, thin slices of frozen raw meat or fish [

68]. Meat-based diets are supplemented with edible herbs and plants, berries, and other types of accessory foods [

69]. For example, the Yukaghir consumes different edible plants, like wild onion, and day lily roots, as well as berries and mushrooms.

The Sakha cuisine is set aside in that it is influenced by elements of both Arctic and Mongolian cuisines [

68]. It relies heavily on meat, although in this case primarily on horse meat as the Yakut are expert horse breeders. They also raise cattle and dairy products historically represent a central part of their diet. The Kymys, for example, is a very popular drink made from fermented mare's milk. Fish is also a prominent product of their diets, especially Siberian sturgeon, broad and northern whitefish, Arctic cisco, muksun, and grayling [

68]. However, it must be noted that Russian colonization of Yakutia and all its IPs, starting in the 1600s, gradually changed the traditional diet structure of all these indigenous groups, especially the Sakha, introducing products like flour, grains, salt, sugar, tea, or alcoholic beverages and borrowing culinary practices, especially soups and mushrooms consumption [

69].

3.2. Legal and regulatory frameworks in the Indigenous settlements of Yakutia (Russia)

Unlike the Karen Indigenous communities in Thailand where the legal and regulatory frameworks on access to forests and natural resources are handled by the Royal Thai Government, access to forests and natural resources by the Yakutian Indigenous communities is governed by formal and informal rules that have been developed over centuries in the context of political and economic changes in Russia [70}. Past and present practices of Indigenous peoples for accessing and using land and natural resources have been guided by informal rules governed by groups of Indigenous peoples that are formed on family, kinship, or tribal proximity [

71]. Formal rules regarding access to and development of natural resources began to be introduced in the 1920s during the Soviet industrialization and collectivization of Yakutia, which was accompanied by a new administrative-territorial division within Yakutia. The state policies on collectivization during the Soviet period in Russia attempted to unite small households into collective farms, including Indigenous peoples in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) and building settlements around the collective farms [

72]. During the Soviet period, the rights to use natural resources for fishing, hunting, collecting plants, reindeer husbandry, and other industries of the Indigenous peoples of the North became formally regulated through the framework of collective farms [

71].

Since the breakdown of the Soviet Union, legal and economic reforms led to the dissolution of many collective farms of Indigenous peoples, although some remnants of these organizations still exist and lead economic activities. However, in the majority, the Indigenous peoples were given a chance to form smaller units or organizations to lead traditional natural resource practices. Along with the law on traditional natural resource use of Indigenous peoples of the North, new forms of organizations emerged, such as tribal communes. A tribal commune is a small organization that allows members of the same family or kin to engage in ‘traditional natural resource use’ practices such as reindeer herding, fishing, and hunting. These tribal communes started to gain legal rights to their traditional land under the regulation on ‘territories for traditional natural resource use’. Thus, as of 2020, Indigenous peoples of the North in Yakutia have registered 62 such territories across 21 districts out of 33 districts of Yakutia [

66]. These territories are not owned by the tribal communes (and other forms of organizations of Indigenous peoples such as limited companies, etc.) but are awarded by the federal state for specific use. Overall, the major branches of legislation on land, forests, fisheries, and hunting are developed at the federal level. Individual regions in Russia (such as the Republic of Sakha) have limited capacity to introduce changes to the implementation of these federal laws. However, some scholars have also noted that this complex structure has created resistance to the decisions made at the federal level in some regions and the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) has been one of those that has resisted rash decisions made at the federal level. This makes the protection of the rights of indigenous peoples stronger than in other regions of Russia, including neighboring ones

3.3. Implications of legal and regulatory frameworks on the ISES and TFS of Indigenous Communities in Yakutia (Russia)

The legal and regulatory frameworks in Yakutia wield considerable influence over the Indigenous communities inhabiting this region, resulting in multifaceted impacts that significantly shape their way of life (Petrov 2018). Access to land and natural resources, essential for the traditional livelihoods of these indigenous groups, has become increasingly challenging due to state or private control over many of these resources {67,73,74]. This shift has impeded the ability of indigenous communities to secure the resources vital for their survival and prosperity. Moreover, the legal and regulatory landscape often prioritizes large-scale economic development projects, occasionally at the expense of the time-honored traditions and cultures of the indigenous communities [

75]. Such projects can have detrimental effects on both the environment and the deeply rooted cultural heritage of these communities. The dearth of adequate protection for the cultural rights of indigenous groups is a significant concern. Frequently, they lack the right to free, prior, and informed consent before development projects are undertaken on their ancestral lands, a key factor undermining their cultural autonomy and their ancestral right to their land which sustains their traditional food system [

76].

Examples of these impacts are evident in several notable cases. For instance, the construction of the Sakhalin-Khabarovsk-Vladivostok oil pipeline has inflicted adversity upon the Evenki and Yakut Indigenous communities in Yakutia [

67,

75,

77]. This massive infrastructure project has disrupted the traditional migration patterns of reindeer and other animals, which serve as essential sources of local traditional food that these communities depend on. The construction has additionally wrought environmental pollution and inflicted damage upon the cultural heritage sites that hold immense significance for indigenous identity and spirituality [

67,

75,

77]. Similarly, the development of the Yakutia gas fields has resulted in the forced displacement of indigenous communities from their ancestral lands. These gas fields, situated in remote regions, have compelled these communities to relocate to towns and cities, where they often grapple with challenges in finding employment and preserving their cultural practices [

67,

75,

77]. The introduction of new fishing laws in Yakutia has compounded the difficulties faced by indigenous communities, particularly in their pursuit of subsistence fishing. These laws have exacerbated conflicts between indigenous communities and the government, creating tensions that challenge the cultural and economic equilibrium [

73,

75].

One of the main difficulties for Indigenous peoples to engage in natural resource use practices relates to the complexity of the relationship between the federal state and regional administrative, executive, and legislative powers. There is a division of ownership, control, and governance for land, forests, and water bodies, including the administration of rights and environmental protection [

74]. For instance, private land ownership is only possible within the boundaries of municipalities such as villages and towns, and almost all forested land in Russia belongs to the federal state. Incidentally, this is where Indigenous peoples lead their traditional natural resource activities. If a river flows through the boundaries of two regions, for example, it is governed federally. Thus, the importance of federal administration in natural resource use is of paramount importance, often overpowering the interests and concerns of regional populations and Indigenous people’s interests and, consequently, affecting the routines and natural resource practices of Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations [

73]. Changes in Russian legislation and accompanying regulations and procedures for natural resource use activities in forests and water bodies such as hunting, fishing, and plant gathering often taken without specific regard to the interests of populations and consideration of regional specifics of the natural environment.

Despite these adversities, the Indigenous communities of Yakutia have exhibited remarkable resilience and determination in protecting their rights and heritage. They continue to engage in efforts to preserve their culture and secure sustainable economic development projects that benefit their entire community. These endeavors underscore the enduring spirit and commitment of these communities to maintain their unique identities and way of life in the face of formidable challenges.

4. Examining the political-ecological theoretical framework (PETF) as applied in our study

Below we revisit and delve into the three main dimensions of PETF that are unique in examining the legal and regulatory framework in the context of the ISES and TFS for our two case studies:

Power dynamics and Indigenous rights: The Yakutia just like the Karen Indigenous communities have witnessed historical disparities in power dynamics. The PETF as discussed earlier facilitates the examination of power dynamics embedded in legal and regulatory frameworks. These power dynamics have the potential to either empower or disenfranchise Indigenous communities as they strive to assert their rights over their lands, resources, and traditional knowledge. It provides a means for critically analyzing how legal structures might perpetuate or contest historical inequalities and injustices experienced by Indigenous peoples. In the case of the Yakutia Indigenous Groups in our study, the legacies of colonization and Soviet-era policies have shaped an environment where Indigenous communities in this region often face challenges in asserting their rights. The centralization of power has historically limited the influence of these people over decisions affecting their lands and resources. Furthermore, the pressure for resource extraction, often driven by external economic interests, has created power imbalances between the government and the Indigenous people of this region. The rights of the Yakutia IPs have in many cases compromised as economic agendas prioritize extraction over the preservation of Indigenous lands and traditional practices, leading to environmental degradation and challenges to sustainable socio-ecological systems. While legal frameworks in Russia recognize Indigenous rights, implementation has proven to be challenging. The recognition of Indigenous land rights and the right to practice traditional livelihoods is crucial, but gaps in enforcement and disparities in legal interpretation may impede the full realization of these rights.

The Karen IPs on the other hand have long grappled with challenges related to land rights. The historical land dispossession and conflicts over territory have led to power imbalances, with Karen people facing difficulties in securing and maintaining their ancestral lands. State policies as discussed have prioritized other interests, leading to marginalization and compromising Indigenous rights. Furthermore, the presence of military forces in regions inhabited by Karen communities has created power dynamics that adversely affect Indigenous rights. Armed conflicts and militarization pose threats to the security and well-being of the Karen people, limiting their agency in decision-making processes related to land use, resource management, and the preservation of their cultural heritage. And lastly, conservation policies in the Karen communities, while aiming to protect natural resources, have come into conflict with Indigenous practices. Forest conservation measures in Thailand and in Karen communities as discussed in this study have restricted access to traditional lands and resources, impacting their ability to sustain their traditional food systems. It can therefore be pointed out that negotiating a balance between conservation goals and Indigenous rights remains a challenge. The power dynamics as discussed in our two study communities can either empower or disempower Indigenous communities in asserting their rights over their lands, resources, and traditional knowledge. In our two case studies, there is clear evidence that power dynamics have disempowered Indigenous communities in asserting their rights over their lands, resources, and the sustainability of their TFS. Thus, understanding these power dynamics is critical as it allows for a robust examination of how legal frameworks may perpetuate or challenge historical inequalities and injustices faced by Indigenous peoples.

Socio-political contexts and environmental implications: this is another dimension in PETF. In the Karen Indigenous communities, the socio-political context is characterized by historical struggles for land rights, militarization, conflicts, and challenges posed by forest conservation policies. Limited political representation contributes to the historical marginalization of the Karen, impacting their ability to advocate for Indigenous rights and preserve their cultural identity. In Yakutia Indigenous communities, resource extraction pressures, centralized power structures, and the impact of Soviet-era policies have tremendously shaped the socio-political dynamics. Climate change further adds complexity, affecting traditional livelihoods, while efforts for cultural preservation persist despite challenges. Limited control over land use and historical inequalities underscores the need for inclusive policies that respect Indigenous rights and cultural heritage in both contexts. In both our case studies the Indigenous communities experience limited political representation, affecting their ability to advocate for their rights at the governmental level. In both our two case studies decisions to protect and govern ISES are made at the top and enforced on the Indigenous communities which hampers their ability to sustainably protect and maintain their lands and TFS. The lack of inclusive decision-making processes has exacerbated the power imbalances, hindering the effective protection of the ITFS and rights. Efforts to preserve the socio-cultural identity and traditional knowledge among the Karen and the Yakutia Indigenous people face challenges due to external pressures and power differentials. Thus, this understanding is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness and fairness of legal frameworks in achieving the resilience and sustainability of ISES and ITFS.

Unequal resource distribution and historical marginalization: in the PETF this dimension allows for an analysis of resource distribution and historical marginalization within the context of ISES. Both the Karen and Yakutia indigenous people have experienced historical marginalization and unequal resource distribution. For the Karen, land dispossession, conflict-induced displacement, and limited political representation have contributed to ongoing challenges in accessing and managing ITFS resources. In Yakutia, historical legacies such as resource extraction prioritizing economic interests, centralized power structures, and the impact of Soviet-era policies have led to economic exploitation and limited control over the benefits derived from the region's resources for the Indigenous Yakutia communities. Addressing these historical injustices requires comprehensive legal reforms, recognition of Indigenous rights, and inclusive decision-making processes that empower these communities.

Discussion

From the combined use of desktop research methodology analysis with a focus on existing literature reviews on the topic, national legal and regulatory laws governing the Indigenous territories in our study communities, our on-site observations, and a comprehensive analysis of international Indigenous rights reports the findings of this research study have shown that the Karen Indigenous people of Thailand have a rich history deeply intertwined with their natural environment, reflecting a profound connection to their land. However, the introduction of legal and regulatory frameworks, particularly during the colonial and post-colonial eras, has had far-reaching consequences for these communities. As discussed in the colonial era, the Karen faced a series of challenges that have resulted in the continuous erosion of their cultural identity and access to their TFS. The Royal Thai government policies that have been aimed at assimilating them into the dominant Thai culture have mainly involved the suppression of the Karen language, customs, and religious practices. These policies, alongside land-related regulations, have continuously disrupted their traditional agrarian way of life. As a result, many Karen people continue to face displacement, loss of their livelihoods, and social upheaval.

The post-colonial period has continued to bring challenges to the Karen people, including forced relocations, marginalization, and discrimination, perpetuating socio-economic inequalities and igniting resistance and resentment among the Karen communities. The impacts of these legal and regulatory frameworks on the well-being of the Karen people as discussed in this study are substantial. These frameworks have not only led to restrictions on land rights but have also caused a lot of identity and damage to the traditional lifestyle which in many cases has led to the limitation in access to and use of their ancestral lands and TFS. The loss of legal ownership has made it challenging for the Karen to engage in traditional livelihoods such as hunting, gathering, farming, and foraging. Moreover, limited access to education and healthcare services compounds the challenges faced by these communities. Often residing in remote areas with underdeveloped infrastructure, many Karen struggle to access quality education and healthcare, affecting their quality of life. Discrimination and violence, both from the government and military, further compound the difficulties faced by the Karen people, leading to forced displacement, torture, and even extrajudicial killings.

Despite these challenges, there have been some positive developments, such as the recognition of the Karen people as an indigenous group. However, significant hurdles persist. To safeguard the rights and dignity of the Karen people, a comprehensive effort is needed. This includes ensuring equitable land rights, improving access to education and healthcare, and addressing the issue of discrimination and violence that continues to affect these communities. This case study of the Karen Indigenous people of Thailand illustrates the profound impacts of poorly framed legal and regulatory frameworks on indigenous communities across the globe. These findings are in line with research conducted by other researchers on the Karen Indigenous communities such as [

53,

57,

61,

62] who have also indicated the aforementioned impacts of the legal and regulatory frameworks on the Karen Indigenous people of Thailand.

It is vital to point out that despite the many challenges being faced; the Karen people of Thailand have exhibited remarkable resilience and determination as they navigate the multifaceted challenges impeding their rights and well-being. To assert their rights, they have adopted a multifaceted approach, employing various strategies rooted in advocacy, legal action, community development, and international collaboration. In their pursuit of justice and equitable treatment, the Karen people have engaged in advocacy and campaigning, which serve as powerful tools for raising awareness about their struggles and promoting their rights. They have employed a range of methods, such as organizing public meetings, staging demonstrations, and harnessing the reach of social media campaigns. Through these endeavors, they aim to amplify their voices, not only within Thailand but also on the global stage. Legal challenges constitute another integral facet of the Karen people's efforts to dismantle discriminatory laws and regulations. They have taken legal action against the Thai government, seeking redress for violations of their land rights and cultural rights. These lawsuits represent a crucial avenue through which the Karen people contest the prevailing legal framework that has perpetuated their marginalization and inequity. Moreover, the Karen community places a strong emphasis on community development as a means to improve their overall livelihoods. Initiatives such as the establishment of schools, healthcare clinics, and agricultural cooperatives form the backbone of their community-building efforts. These ventures not only bolster self-reliance but also foster the preservation of their cultural heritage, ultimately enhancing the overall quality of life within their communities.

In recognition of the global nature of indigenous rights issues, the Karen people have strategically forged international networks. By collaborating with other indigenous communities and human rights organizations worldwide, they access a platform to share information and best practices while garnering support for their cause. These networks extend solidarity and amplify their advocacy, broadening the scope of their influence. In recent years there have been specific organizations that have been playing a pivotal role in advancing the Karen people's rights and interests in Thailand. These include the Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG), a non-governmental organization, that is dedicated to safeguarding the rights of the Karen people by meticulously documenting human rights abuses and advocating for justice at both the national and international levels. Another is the Karen Women's Organization which is a women's rights group that champions the rights of Karen women and girls, offering critical support through education, healthcare, and other services while lobbying for their rights. The third one is the Karen National Union a political organization representing the Karen, which tirelessly works toward securing their right to self-determination. The Karen National Union has also initiated numerous social services, such as schools and healthcare clinics, to enhance the well-being of Karen communities. It can therefore be concluded that the history of the Karen people in Thailand is fraught with challenges, but their unwavering commitment to progress and advocacy has led to significant advancements in their struggle to assert their rights. They have become exemplars of resilience, inspiring hope for a brighter future not only for themselves but also for the generations that will follow. The Karen people's journey reflects the enduring spirit of indigenous communities worldwide as they seek justice, equality, and the preservation of their rich cultural heritage.

In contrast, the indigenous communities of Yakutia in Russia face a different set of legal and regulatory challenges. Their access to forests and natural resources is subject to both formal and informal rules, with an evolving trend towards state or private control over these resources, often at the expense of their traditional way of life. Historically, access to and use of land and natural resources have been guided by informal rules based on family, kinship, or tribal proximity. Formal rules were introduced during the Soviet period when the state aimed to consolidate control over these resources by organizing collective farms. The dissolution of the Soviet Union allowed indigenous communities to form smaller units or organizations to continue their traditional natural resource practices.

As our findings have shown, the legal and regulatory frameworks in the Sakha Republic today have tended to prioritize large-scale economic development projects, sometimes at the expense of indigenous traditions. These have significantly disrupted migration patterns of reindeer and other animals, leading to environmental pollution and damage to cultural heritage sites. Similarly, the development of gas fields has resulted in forced relocations and environmental damage. In the same vein, Indigenous communities in this region have often lacked the right to free, prior, and informed consent before development projects are initiated on their ancestral lands, undermining their cultural autonomy and their traditional ways of life. For instance, the construction of the Sakhalin-Khabarovsk-Vladivostok oil pipeline has adversely affected the Evenki and Yakut Indigenous communities in Yakutia. This massive infrastructure project has disrupted the traditional migration patterns of reindeer and other animals, which serve as essential sources of sustenance for these communities. The construction has additionally wrought environmental pollution and inflicted damage upon the cultural heritage sites that hold immense significance for the indigenous identity and spirituality of these people.