Submitted:

20 January 2024

Posted:

29 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

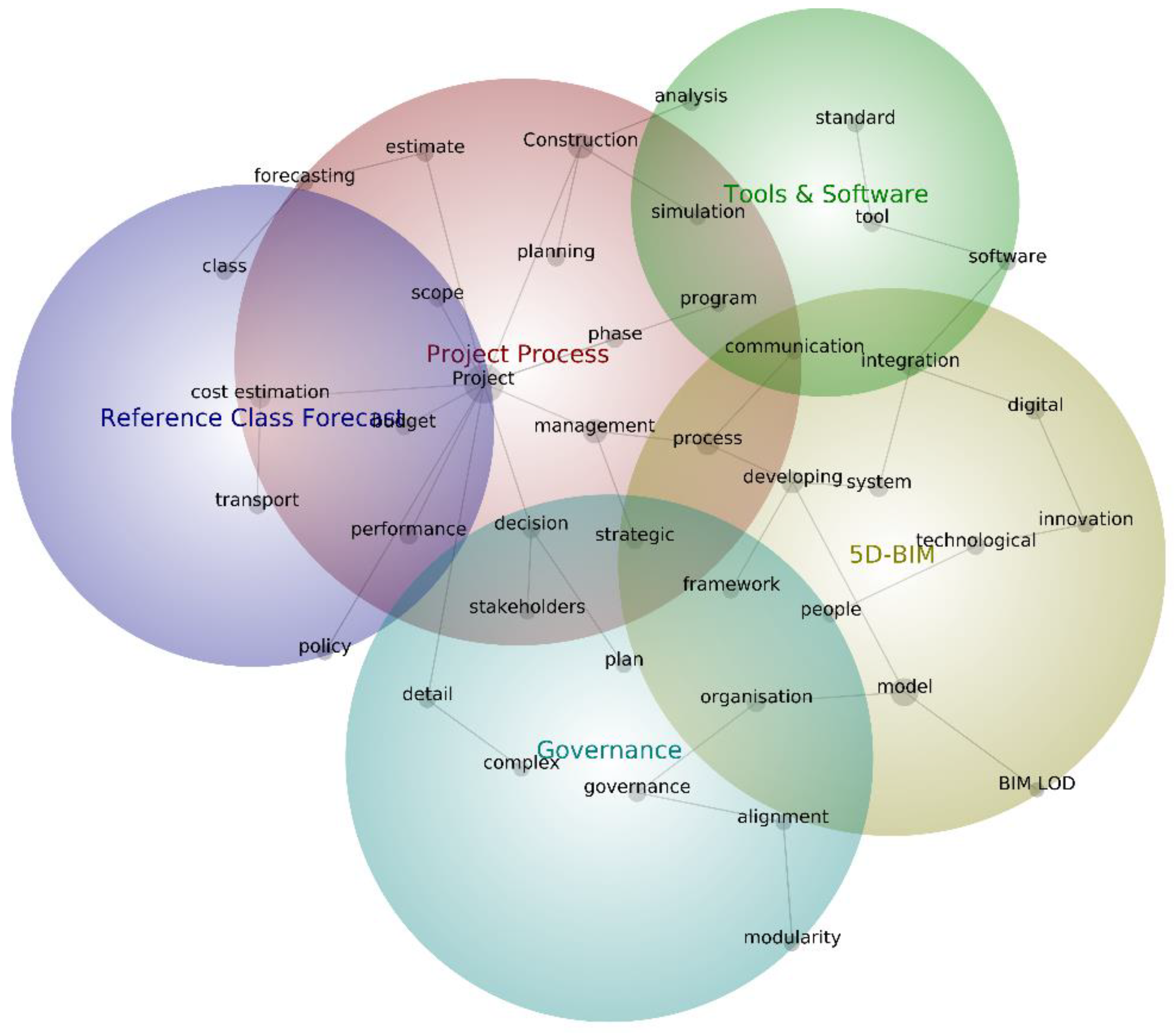

2. BIM-based Governance management frameworks

2.1. Management frameworks

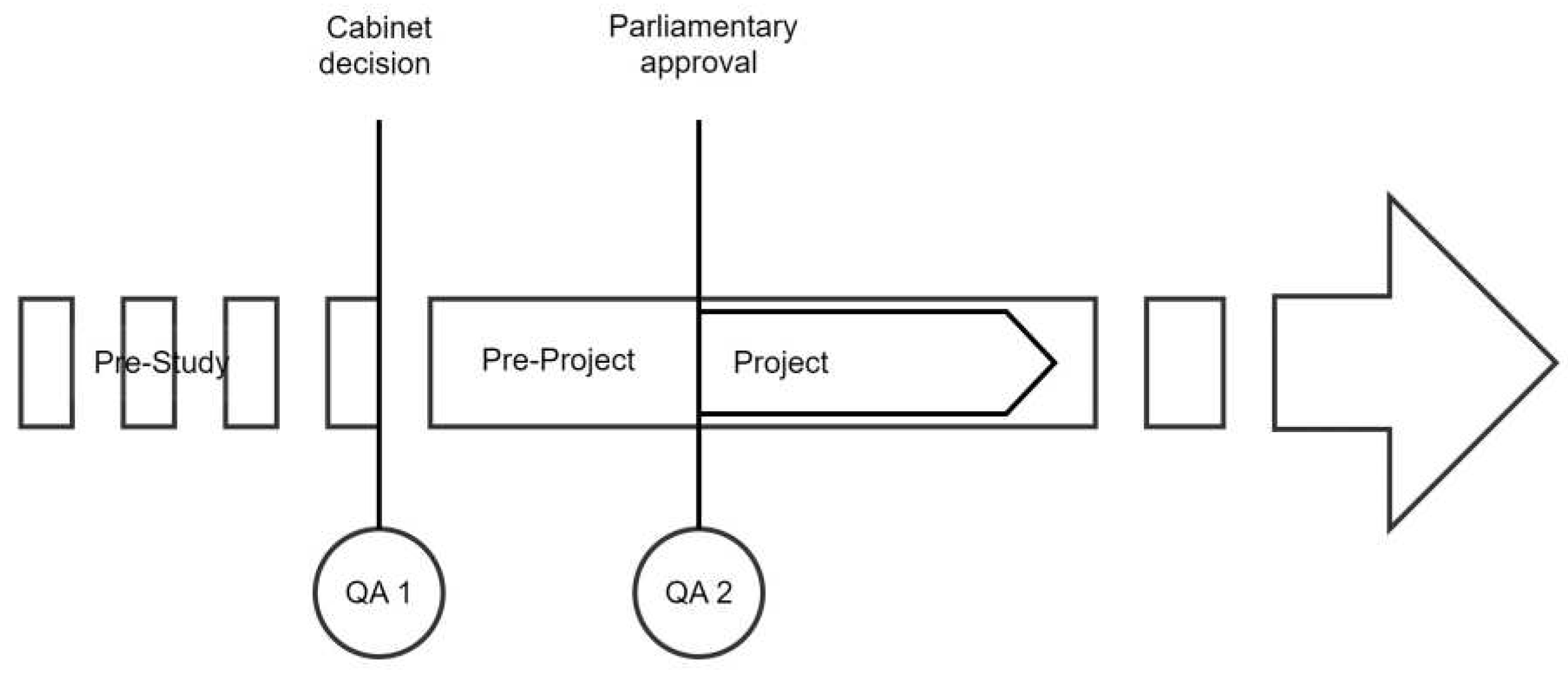

2.2. Project governance

- ▪

- ▪

- Excessive bureaucracy and complexity of decision-making structures and processes. This includes the presence of hierarchical power dynamics within government agencies, which can impede the free flow of information [54].

- ▪

- Absence of data management systems and using outdated or incompatible technology platforms to track and monitor project progress [55].

- ▪

- Poor stakeholder engagement and inadequate communication of project goals, strategies, and performance to the right stakeholders, can create an environment conducive to political maneuvering and corruption [56].

2.3. Five-Dimensional Building Information Modelling (5D-BIM)

| BIM Dimension | Descriptions | Characteristics | Popular software / solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D | 3D-BIM is the foundational level, it represents the geometry dimensions. | 3D building data and information, field layout and civil data, reinforcement and structure analysis, existing model data. | AutoCAD, Revit, Bentley MicroStation, ArchiCAD, Allplan, and Tekla [68]. |

| 4D | 4D-BIM adds the element of time to the 3D model. | Project schedule and phasing, just-in-time schedule, installation schedule, payment visual approval, last planner schedule, critical point. | Synchro PRO, Navisworks, Trimble Vico Office, Fuzor, Asta Power Project, and C3D interactive[69,70]. |

| 5D | 5D-BIM extends the capabilities of the model by incorporating cost estimation and quantity take-off data. | Conceptual cost planning, quantity extraction to cost estimation, trade verification, value engineering, prefabrication. | RIB CostX [17] , Bexel Manager [71], PriMus [72], Cubicost [73], and Contruent (Ares prism) [74]. |

| 6D | 6D-BIM focuses on sustainability and environmental aspects. | Energy analysis, green building element, green building certification tracking, green building point tracking. | Autodesk BIM 360 Ops [75], FM: Systems [76], and EcoDomus [77]. |

| 7D | 7D-BIM integrates the facility management, operation & maintenance data into the model. | Building life cycles, BIM as built data, BIM cost operation and maintenance, BIM digital lend lease planning. | IBM TRIRIGA [78], ARCHIBUS [79], IBM Maximo [80], and FM: Systems [76]. |

- Rail-Specific Components: This includes the design and specification of rails, sleepers (ties), ballast, signaling equipment, electrification systems (like catenaries or third rails), and communication systems.

- Stations and Facilities: Detailed models of station buildings, platforms, canopies, ticketing areas, and other passenger-related facilities.

- Structural Elements: Bridges, tunnels, retaining walls, culverts, and other structural components that support the rail infrastructure.

- Interoperability and Systems Integration: This pertains to integrating various subsystems within the railway infrastructure, such as signaling systems, train control systems, and power supply systems.

- Material Specifications and Libraries:

- Product Libraries: Manufacturer-specific components that are used within the railway industry, such as specific types of rail or signaling equipment.

- Standard Libraries: Commonly used elements and symbols within the rail industry, often adhering to national and international rail standards

- Quantities and Shared Properties: Data for material quantities, lengths of track, numbers of components, and other quantifiable aspects of the railway, which are vital for cost estimation and procurement.

- Non-geometric Data: Information such as maintenance schedules for track and equipment, operation manuals for signaling systems, and warranty information for installed components.

- Analytical Models: These models are used for various types of analysis, including structural analysis of bridges and tunnels, dynamic analysis of track under loading from trains, and capacity analysis for signaling systems.

- Environmental and Contextual Data: Information about the terrain, surrounding environment, and interface with existing infrastructure, which are crucial for planning and environmental impact assessments.

- Construction Sequencing (4D): Integration of the construction schedule to visualize the construction process over time, optimize the sequence of works, and reduce conflicts during the construction phase.

- Cost Estimation (5D): Embedding cost information for budgeting, cost management, and financial tracking throughout the lifecycle of the railway project.

2.4. Common Data Environment (CDE)

2.5. BIM Policies and Standards

| Country | BIM Policy | Approach | Challenges/Support | References |

| China | Outline of Development of Construction Industry Informatisation (2016-2020) Railway BIM Data Standard[102] |

Strong government involvement. | Policy development lags behind practical application | [14,103] |

| USA | National BIM Standard – United States® (NBIMS-US™)[104] | Market-driven, less government enforcement. | Barriers to BIM adoption include size and scale of the project, high training and migration costs, general resistance and reluctance, and the Computer Aided Design (CAD) vs BIM debate | [95,105] |

| UK | Government Construction Strategy (2016-2020)[106] | Government-mandated BIM in public projects. | Setting standards and protocols for collaborative work | [105,107] |

| Singapore | Singapore BIM Guide[99] | Government-led with strategic technology adoption. | Training, standards development, and incentives | [100,108] |

| Japan | - Guidelines for BIM Standard Workflows (MLIT, 2020)[109] -Vision for the Future and Roadmap to BIM[110] |

Combination of government initiative and private sector involvement. | Challenges include difficulty in immediate promotion according to international standards, lack of mandatory BIM use, and reliance on government-led projects | [100,101] |

| Germany | German BIM Implementation Strategy for Federal Buildings[111] | Emphasis on standardisation and industry-driven initiatives. | National BIM standards and guidelines focused on interoperability | [112,113] |

| Australia | - National BIM Guide[96] | Market-driven with some government influence. | Barriers in Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) include ROI concerns and resource limitations | [97,98] |

2.6. 5D-BIM software and tools

| Software/solution | Competitive advantage | Key Features | Training Availability | Additional Notes | Cost (Approx.) | References |

| RIB- Cost-X[117] | Cost-X excels at enabling users to conduct thorough quantity take-offs and cost estimations directly from the BIM model. This functionality automates the generation of quantities and cost data based on the elements within the BIM model, while also facilitating comprehensive cost analysis and reporting. | Construction estimating, takeoff, BIM file support | Online self-paced, day sessions, private training | Integrates with Microsoft Excel | Flexible pricing based on project type/size/No of users. | [17,118,119] |

| Bexel Manager[120] | Bexel Manager stands out by having advanced visualization tools that integrate with the 3D model to represent cost data in intuitive charts, graphs, and dashboards, helping stakeholders to understand complex cost information more easily. | 3D, 4D, 5D, 6D BIM uses, digital construction management | Online, trainer-led, self-paced | Advanced open BIM technologies | Varies, $ 985 /user/year for Bexel Manager Teamworks, 250+ user. | [71,121,122] |

| ARES PRISM (rebranded as Contruent)[123] | ARES PRISM is highly regarded for supporting Earned Value Management (EVM) allowing for better project control, also for its high scalability and customizability. | Integrated cost and scheduling, project management | Instructor-led and online, fundamental to advanced | Executive dashboards | Flexible pricing based on project type/size/No of users. | [74] |

| Cubicost[124] | Cubicost is known for its strong integration capabilities with various BIM platforms, allowing users to leverage 3D models for accurate quantity take-off and cost estimation. | BIM for quantity surveying, 5D BIM cost management | Workshops, online courses, interactive sessions | Supports different modeling and estimation modules TAS, TRB, TBQ, TME modules | Not specified | [73,125] |

| PriMus[126] | PriMus is often praised for its user-friendly interface, making it accessible and intuitive for both seasoned professionals and those new to cost estimation software. It seamlessly integrates with various price books and databases, enabling users to access up-to-date pricing information for materials and resources. | Drag-and-drop interface, integrates with CAD | Online resources and support | Manages quantity surveying, cost estimating, BOQ | Starts at $31.57/month | [74,127] |

2.7. Digital platforms

2.8. 5D-BIM implementation challenges/barriers

| Category | BIM field | 5D-BIM key implementation challenges/barriers | Reference |

| Governance | People | Lack of Leadership and commitment from the project team. | [137,138] |

| Ambiguity in Project Roles and Responsibilities | [137,138] | ||

| Lake of Training and Skill Gaps | [137,138,139,140] | ||

| Resistance to Change | [137,138,139,140] | ||

| Policy | Challenges with quality control | [98,137] | |

| Legal Challenges in Data Ownership and Sharing | [98,137,138,141] | ||

| Need for success measurement and KPIs | [137,138] | ||

| Risk management issues | [137] | ||

| Policy and standards | Policy | Lack of Consistency | [98,137,138,141] |

| Uncertainty in compliance with industry and government requirements | [98,137,138] | ||

| Communication, Processes, and workflow | People | Need for communication Protocols | [98,137,138,139,140] |

| Technology | Data Security and Privacy Risks | [137,138] | |

| Tools and software | Technology | Selecting the right software | [98,137,138,139,141] |

| Data management challenges | [137,138] | ||

| Integration and compatibility | Technology | Difficulties in data migration and integration | [137,138] |

| Hardware requirements and cost | [137,140,141] |

3. Previous studies

4. Contextual background and research method

5. Critical analysis of 5D-BIM implementation in various geopolitical contexts

| Project | Location | BIM Standards and Policy | BIM Maturity Level |

| California High-Speed Rail | USA | NBIMS-US | Advanced: Full collaboration with a shared model, real-time data sharing, and highly integrated processes. |

| Maryland Purple Line | |||

| HS2 | United Kingdom | BS1192/ISO 19650 | |

| Crossrail | BS 1192 | ||

| Riyadh Metro | Saudi Arabia | Emerging BIM adoption, no standardized framework or BIM policy | Moderate: Greater collaboration, shared data through common formats, and more advanced BIM software. |

| Qatar Rail | Qatar | ||

| Etihad Rail | United Arab Emirates | ||

| MTR Northern Link | Hong Kong | HKIBIM, Advanced BIM adoption | |

| Rail Baltica | Baltic States (EU) | Varies by country, moving towards ISO 19650 | |

| Stuttgart-Ulm | Germany | ISO 19650, Moderate BIM adoption | |

| City Rail Link | New Zealand | NZ BIM Handbook, Moderate BIM adoption | |

| Melbourne Airport Rail | Australia | NATSPEC BIM Guide, Moderate to Advanced BIM adoption | |

| Suburban Rail Loop | |||

| Sydney Metro | |||

| Nagpur Metro Rail Project | India | BS 1192:2007+A2:2016, Emerging BIM adoption | |

| Metro Istanbul | Turkey | Emerging BIM adoption, no standardized framework | Developing: Isolated or early-stage BIM usage, limited collaboration, basic BIM tools. |

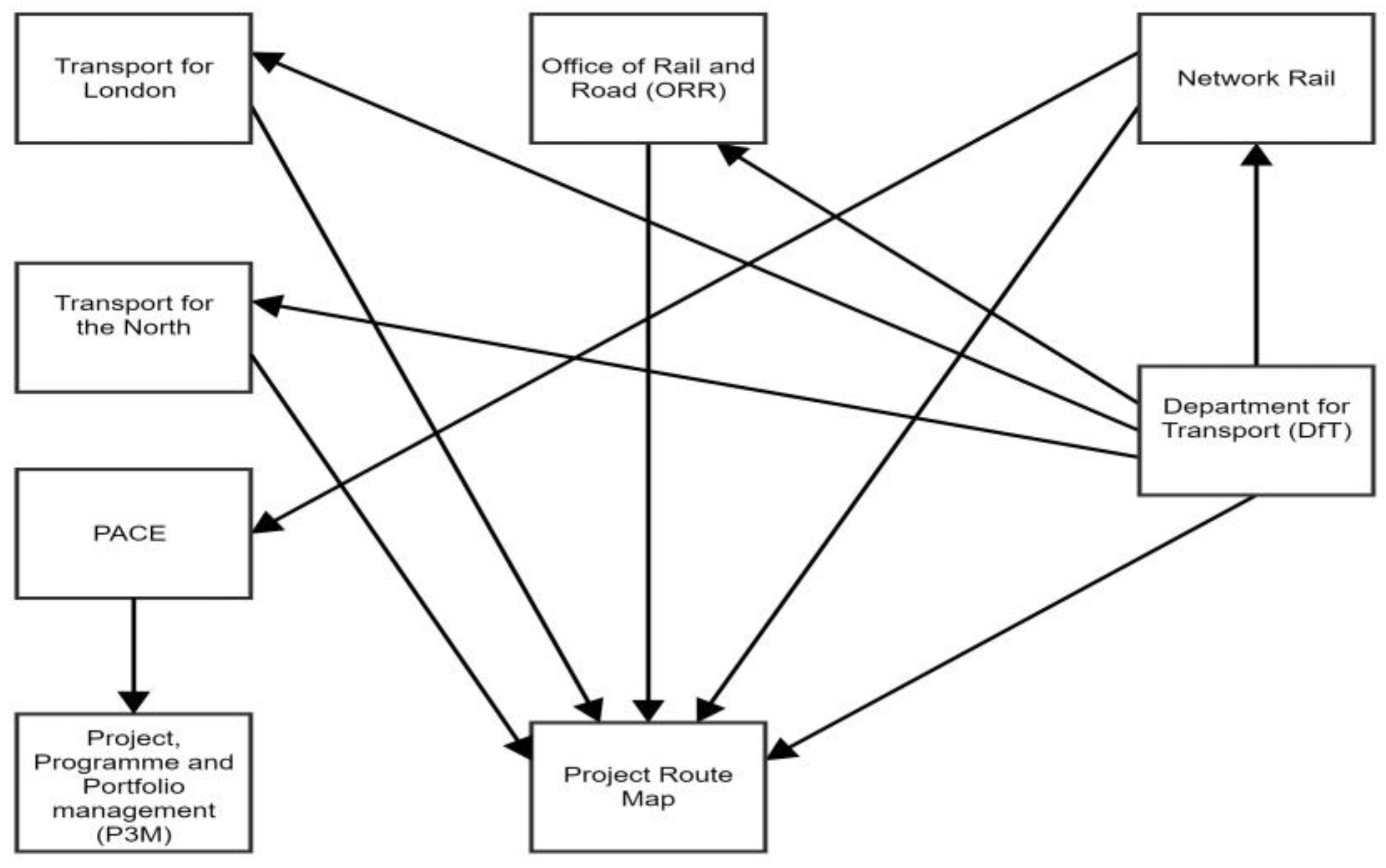

5.1.1. Mega Rail Projects Governance and Delivery in the United Kingdom (UK)

| Dimension | CDE | Governance | 5D-BIM software & Tools | BIM LOD | Cost management & Control standards | BIM Polices & standards | Digital Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK wide standard | ISO 19650 Building Information Modelling BIM [165]. | PACE (Project Acceleration in a Controlled Environment) – replacement of GRIP)[163]. | - | ISO 19650 Building Information Modelling BIM [165]. | Cost Estimating Guidance – Infrastructure and Project Authority [164]. | ISO 19650 Building Information Modelling (BIM) -Replaced BS 1192 [165]. | - |

| Crossrail |

ProjectWise – based on Based on BS 1192 [170] |

Governance for Railway Investment Projects (GRIP) | Contruent (PRISM) [123] | AEC (UK) BIM Protocol [171] | Cost Estimating Guidance – Infrastructure and Project Authority [164]. | BS 1192 [170] | SAP – Axiom- SharePoint |

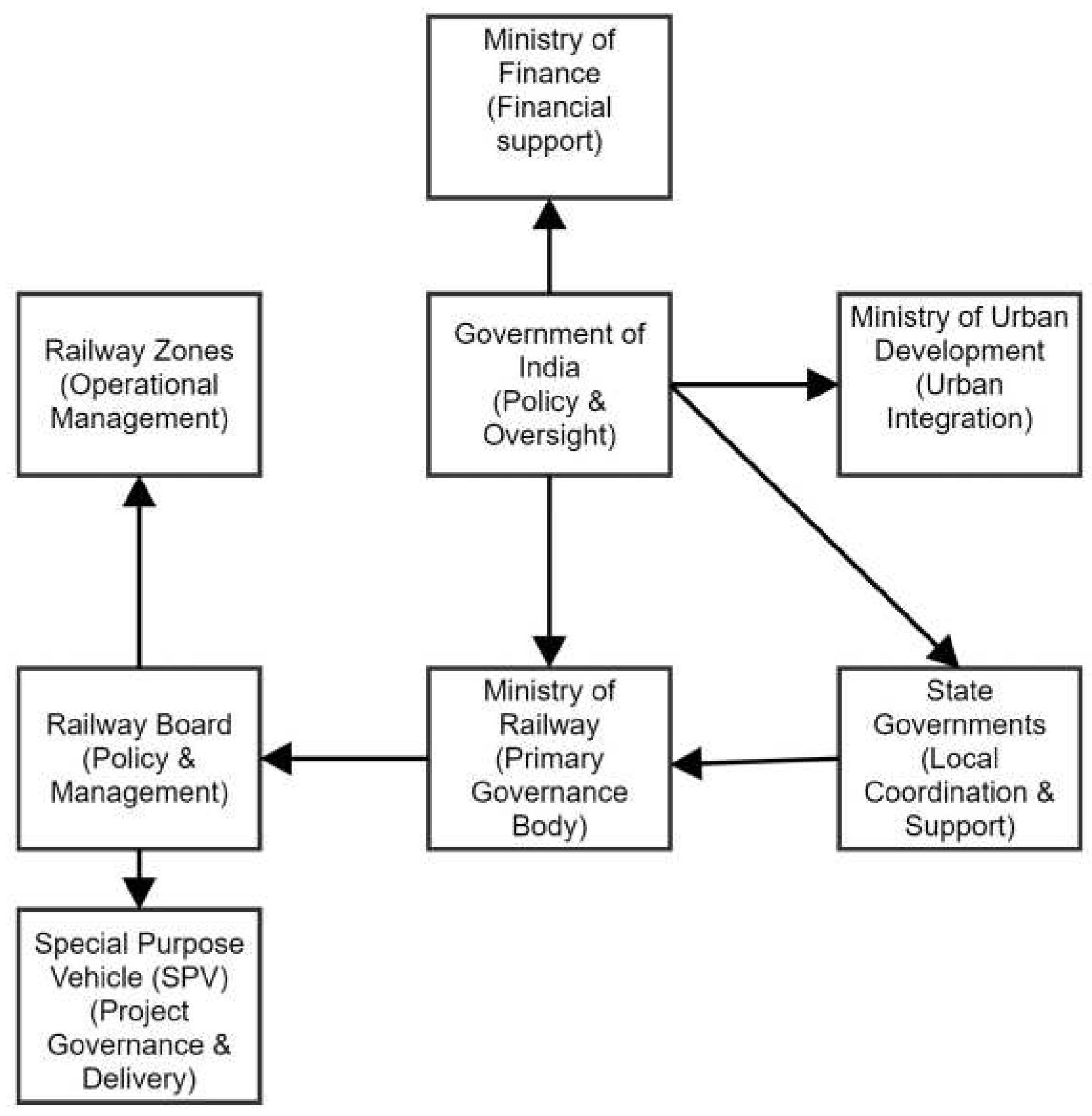

5.1.2. Mega Rail Projects Governance and Delivery in India

| Dimension | CDE | Governance | 5D-BIM software & Tools | BIM LOD | Cost management & Control standards | BIM Polices & standards | Digital Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India wide standard | ISO 19650 BIM [165]. | Hybrid model State Administrative + SPV |

- | ISO 19650 BIM [165]. | Indian Railways – Estimation guideline[181] | ISO 19650 BIM [165]. | - |

| Nagpur Metro Rail Project |

ProjectWise[182] + Asset Wise CDE (eB)[183] |

Hybrid model State Administrative + SPV |

RIBiTWO [180] + Primavera P6 | BS PAS 1199[184] | Indian Railways – Estimation guideline[181] | BS 1192:2007+A2:2016[185] | SAP - ERP |

5.1.3. Lessons learned from case studies in UK and India

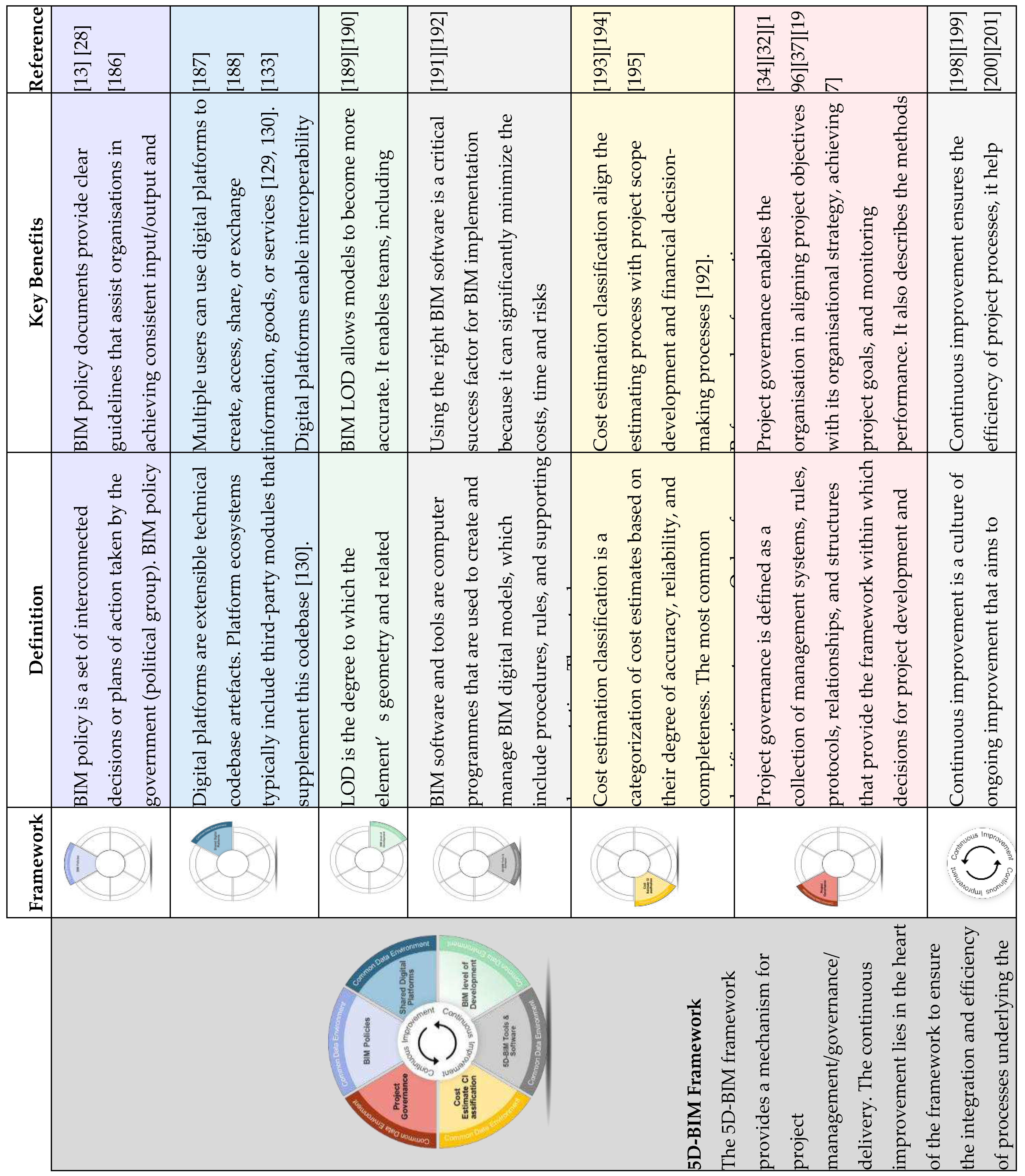

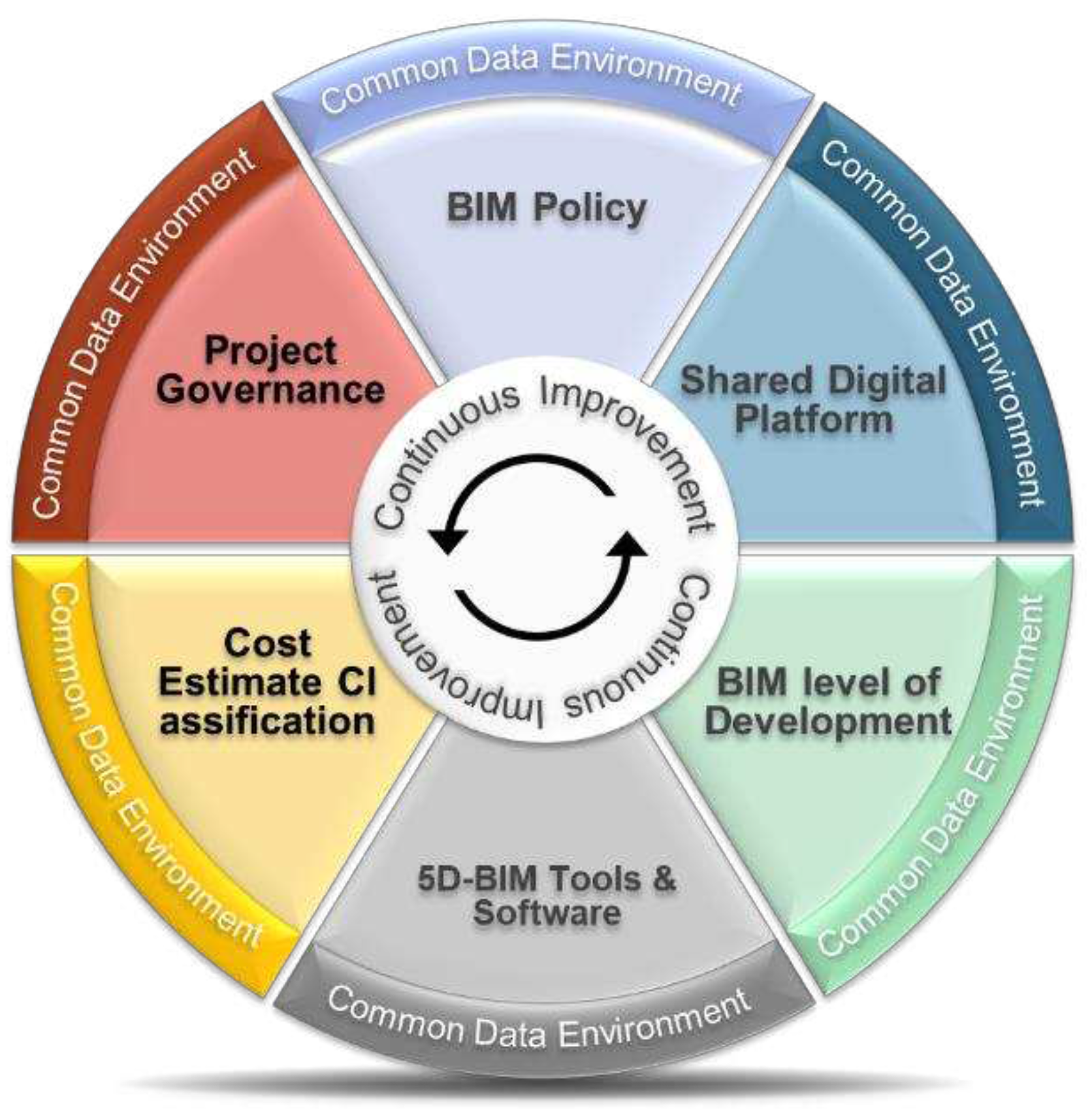

6. The 5D-BIM conceptual framework

6.1. Project Governance:

6.2. BIM policies and standards

6.3. Digital platforms

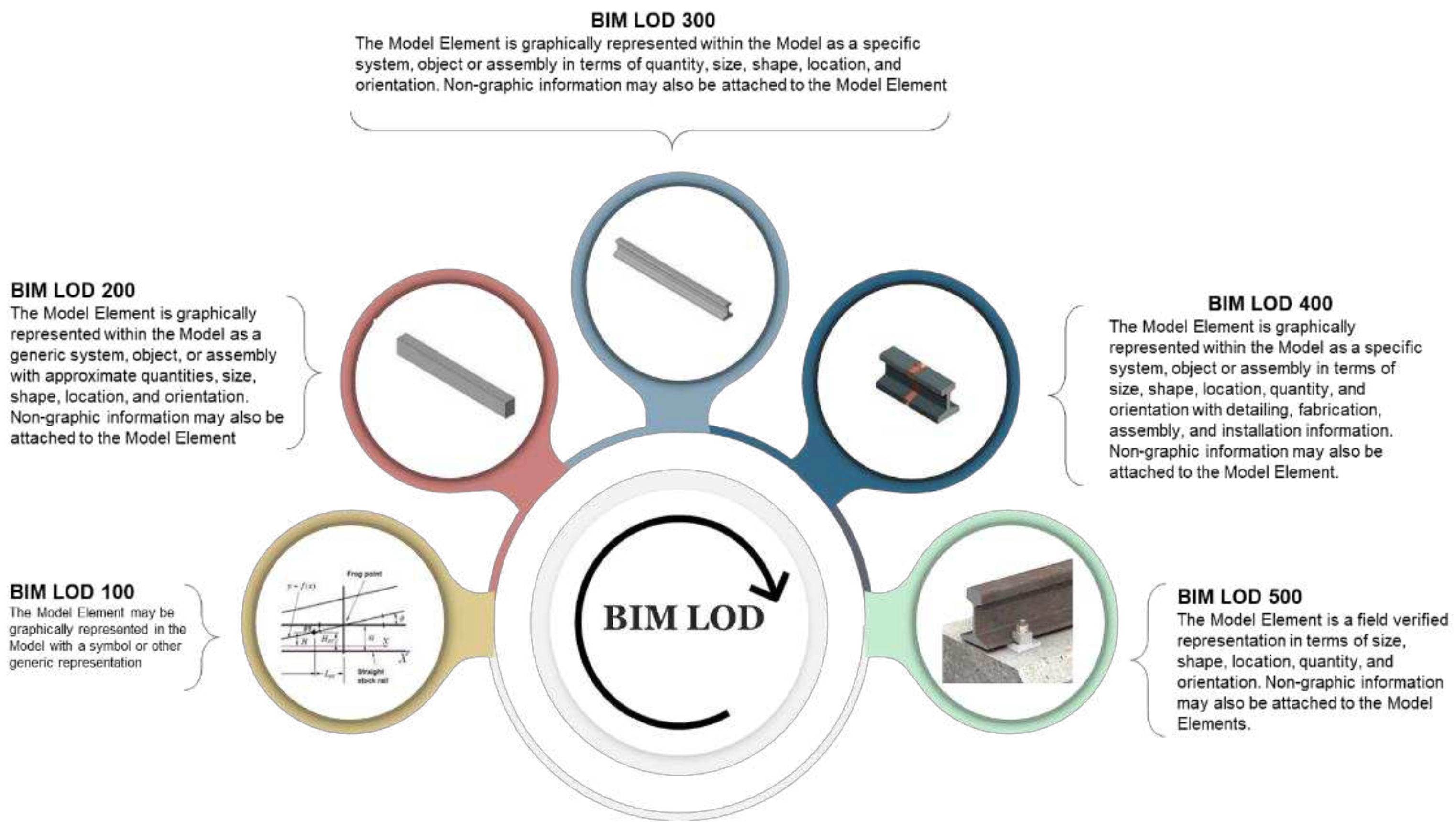

6.4. BIM LOD

6.5. Cost estimation classification

6.6. BIM tools and software

6.7. Common Data Environment (CDE)

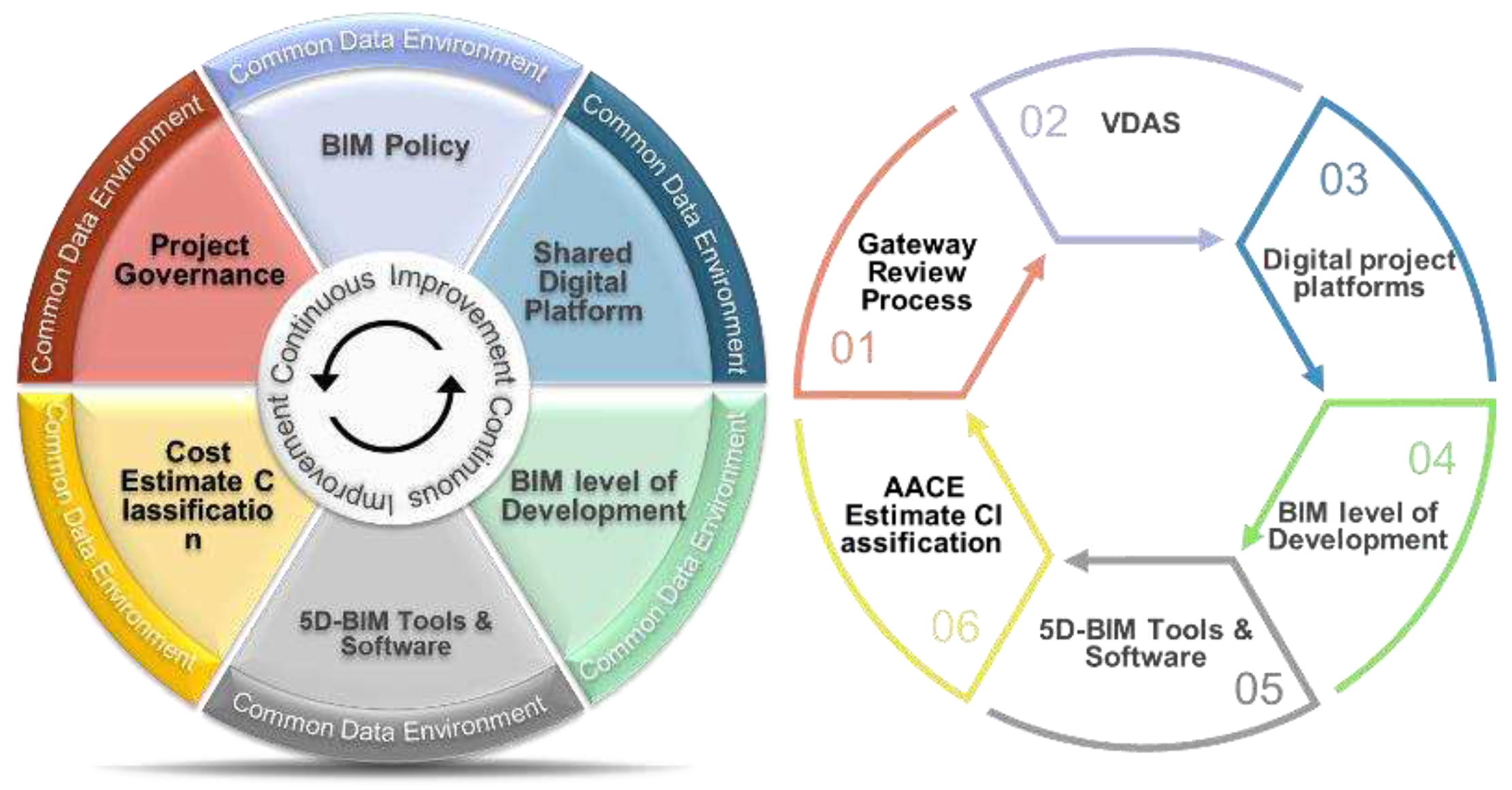

6.8. Global Adaptability of the 5D-BIM conceptual framework

| Key Elements | UK | USA | EU | Victoria (Australia) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project Governance | PACE (Project Acceleration in a Controlled Environment) – replacement of GRIP)[163]. | Stage Gate process (differ by state) – California as an example [230] | Europe’s Rail Joint Undertaking Governance and Process Handbook[231] | Gateway Review process[232] |

| Cost Estimation Classification | Cost Estimating Guidance – Infrastructure and Project Authority[164]. | Cost Estimate Classification System - AACE[233] | ICMS: International Cost Management Standards [234] | Cost Estimate Classification System - AACE[233] |

| BIM policies and standards | ISO 19650 Building Information Modelling (BIM) -Replaced BS 1192[165]. | National BIM Standard-United States® (NBIMS-US™)[235] | ISO 19650 Building Information Modelling (BIM) [165]. | Victorian Digital Asset Strategy (VDAS) [236] |

7. A Victorian perspective

7.1.1.1. Rail Projects governance in Victoria

7.1.1.2. Victorian Digital Asset Strategy (VDAS)

7.1.1.3. Cost estimation classification

7.1.1.4. 5D-BIM software & tools, and Common Data Environment (CDE)

8. Discussion

8.1. 5D-BIM framework development

8.2. Implementing 5D-BIM Across Various Policy and Governance frameworks/Structures

8.3. Application to the Victorian Mega Rail Program Context

8.3.1. Common Data Environment (CDE)

8.3.2. Governance:

8.3.3. BIM policies and standards

8.3.4. BIM level of development (LOD)

8.3.5. 5D-BIM Tools and software

8.3.6. Cost estimation classification

9. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BIM | Building Information Modelling |

| 5D-BIM | Five-Dimensional Building Information Modelling |

| VDAS | Victorian Digital Asset Strategy |

| CDE | Common Data Environment |

| BIM LOD | BIM Level of Development |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

| IT | Information Technology |

| QA | Quality Assurance |

| ISO | International Organisation for Standardization |

| IDD | Integrated Digital Delivery |

| CAD | Computer Aided Design |

| EVM | Earned Value Management |

| DfT | Department for Transport |

| ORR | Office of Rail and Road |

| TfL | Transport for London |

| GRIP | Guide to Railway Investment Projects |

| PACE | Project Acceleration in a Controlled Environment |

| P3M | Programme and Portfolio management |

| HS2 | High Speed Two |

| IFC | the Industry Foundation Class format |

| Maha-metro | Maharashtra Metro Rail Corporation Limited |

| OSO | Owner Support Office |

| ERP | Enterprise Resource Planning system |

| DoT | Department of Transport |

| PTV | Public Transport Victoria |

| RPV | Rail Projects Victoria |

| TIC | Transport Infrastructure Council |

| HVHR | High Value High Risk |

| SRL | Suburban Rail Loop |

| MAR | Melbourne Airport Rail |

| NBIMS | National BIM Standard |

References

- Hussain OAI, Moehler RC, Walsh SDC, Ahiaga-Dagbui DD (2023) Minimizing Cost Overrun in Rail Projects through 5D-BIM: A Systematic Literature Review. Infrastructures 8:93. [CrossRef]

- Capka JR (2004) Megaprojects: Managing a Public Journey. Public Roads 68: 1.

- Ahmad S, Algeo C, Foster S, et al (2019) Review of the key challenges in major infrastructure construction projects: How do project managers ‘skill-up’? In: Annual Conference of the European Academy of Management 2019. European Academy of Management (EURAM),Brussels, Belgium, Lisbon, Portugal, pp 1–39.

- Erkul M, Yitmen I, Celik T (2020) Dynamics of stakeholder engagement in mega transport infrastructure projects. Int J Manag Proj Bus 13:1465–1495. [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg B, Ansar A, Budzier A, et al (2018) Five things you should know about cost overrun. Transp Res Part a-Policy Pract 118:174–190. [CrossRef]

- Love PED, Smith J, Simpson I, et al (2015) Understanding the landscape of overruns in transport infrastructure projects. Environ Plan B Plan Des 42:490–509. [CrossRef]

- Cavalieri M, Cristaudo R, Guccio C (2019) Tales on the dark side of the transport infrastructure provision: a systematic literature review of the determinants of cost overruns. Transp Rev 39:774–794. [CrossRef]

- Ahiaga-Dagbui DD, Love PED, Smith SD, Ackermann F (2017) Toward a Systemic View to Cost Overrun Causation in Infrastructure Projects: A Review and Implications for Research. Proj Manag J 48:88–98. [CrossRef]

- Balali A, Moehler RC, Valipour A (2020) Ranking cost overrun factors in the mega hospital construction projects using Delphi-SWARA method: an Iranian case study. Int J Constr Manag 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Love PED, Sing CP, Carey B, Kim JT (2015) Estimating Construction Contingency: Accommodating the Potential for Cost Overruns in Road Construction Projects. J Infrastruct Syst 21:040140351–0401403510. [CrossRef]

- Ahiaga-Dagbui L (2018) Debunking fake news in a post-truth era: The plausible untruths of cost underestimation in transport infrastructure projects. Transp Res Part A Policy Pract 113:357–368. [CrossRef]

- Musawir A ul, Abd-Karim SB, Mohd-Danuri MS (2020) Project governance and its role in enabling organizational strategy implementation: A systematic literature review. Int J Proj Manag 38:1–16. [CrossRef]

- Lee G, Borrmann A (2020) BIM policy and management. Constr Manag Econ 38:413–419. [CrossRef]

- Xie M, Qiu Y, Liang Y, et al (2022) Policies, applications, barriers and future trends of building information modeling technology for building sustainability and informatization in China. Energy Reports 8:7107–7126. [CrossRef]

- As-Saber SN, Härtel CEJ, As-Saber S, Campus C (2006) Geopolitics and governance: In search of a framework. In: Asia-Pacific Schools and Institutes of Public Administration (NAPSIPAG) conference. 4-5 December 2006, Sydney, Australia, 2006.

- Moses T, Heesom D, Oloke D (2020) Implementing 5D BIM on construction projects: contractor perspectives from the UK construction sector. J Eng Des Technol 18:1867–1888. [CrossRef]

- Vigneault MA, Boton C, Chong HY, Cooper-Cooke B (2020) An Innovative Framework of 5D BIM Solutions for Construction Cost Management: A Systematic Review. Arch Comput Methods Eng 27:1013–1030. [CrossRef]

- Klakegg OJ, Williams T, Magnussen OM, Glasspool H (2008) Governance Frameworks for Public Project Development and Estimation. Proj Manag J 39:S27–S42. [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw AT, Klakegg OJ (2012) Linking policies to projects: The key to identifying the right public investment projects. Proj Manag J 43:14–26. [CrossRef]

- Gillan SL (2006) Recent developments in corporate governance: An overview. J Corp Financ 12:381–402. [CrossRef]

- Mangalaraj G, Singh A, Taneja A (2014) IT Governance Frameworks and COBIT-A Literature Review. In: 20th Americas Conference on Information Systems, AMCIS 2014.

- UK Government (2023) UK BIM Framework. https://www.ukbimframework.org/. Accessed 29 Nov 2023.

- Burton RM, Obel B (2018) The science of organizational design: fit between structure and coordination. J Organ Des 7:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan R, Turner R, Mancini M (2019) Project governance and stakeholders: a literature review. Int J Proj Manag 37:98–116. [CrossRef]

- Papadakis E, Tsironis L (2020) Towards a hybrid project management framework: A systematic literature review on traditional, agile and hybrid techniques. J Mod Proj Manag 8:124–139. [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou MC (2019) An overview of benefits and challenges of building information modelling (BIM) adoption in UK residential projects. Constr Innov 19:298–320. [CrossRef]

- Grundler A, Westner M (2019) Scaling Agile Frameworks vs. Traditional Project Portfolio Management: Comparison and Analysis. In: Proceedings of the International Conferences on Internet Technologies & Society (ITS 2019), Hongkong. pp 51–62.

- Oti-Sarpong K, Leiringer R, Zhang S (2020) A critical examination of BIM policy mandates: implications and responses. In: Construction Research Congress 2020: Computer Applications. American Society of Civil Engineers Reston, VA, pp 763–772.

- UK Government (2023) The Construction Playbook. In: Constr. Playb. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-construction-playbook. Accessed 29 Nov 2023.

- Godager B, Mohn K, Merschbrock C, et al (2022) Towards an improved framework for enterprise BIM: the role of ISO 19650. J Inf Technol Constr 27:1075–1103. [CrossRef]

- Sanderson J (2012) Risk, uncertainty and governance in megaprojects: A critical discussion of alternative explanations. Int J Proj Manag 30:432–443. [CrossRef]

- Ahola T, Ruuska I, Artto K, Kujala J (2014) What is project governance and what are its origins? Int J Proj Manag 32:1321–1332. [CrossRef]

- Williamson OE (1979) Transaction-cost economics: the governance of contractual relations. J Law Econ 22:233–261. [CrossRef]

- Turner R, Müller R (2017) The governance of organizational project management. Cambridge Handb Organ Proj Manag 75–91.

- Samset K, Volden GH (2013) Major projects up front: Analysis and decision-rationality and chance. In: 11th IRNOP conference, Oslo, Norway.

- Soderlund J (2011) Pluralism in Project Management: Navigating the Crossroads of Specialization and Fragmentation. Int J Manag Rev IJMR 13:153–176. [CrossRef]

- Too EG, Weaver P (2014) The management of project management: A conceptual framework for project governance. Int J Proj Manag 32:1382–1394. [CrossRef]

- Code C (1992) The financial aspects of corporate governance. In: London Comm. Financ. Asp. Corp. Gov. Gee Co. Ltd. https://www.ecgi.global/sites/default/files/codes/documents/cadbury.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

- ACID (2010) The Corporate Governance Framework. https://www.aicd.com.au/about-aicd/aicd-membership/director-professional-development/corporate-governance-framework.html. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

- IoDSA (2009) King code of governance. https://www.google.com.au/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwj8uYv1-6_7AhWzx3MBHd1gAsYQFnoECA0QAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fecgi.global%2Fdownload%2Ffile%2Ffid%2F9798&usg=AOvVaw0oN59Ns_TOAALTqf3sXu2f. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

- OECD The OECD principles of corporate governance. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/ed750b30-en/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/ed750b30-en. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

- Gareis R (2010) Changes of organizations by projects. Int J Proj Manag 28:314–327. [CrossRef]

- Muller R (2017) Project governance. Routledge.

- Jonny Klakegg O (2009) Pursuing relevance and sustainability: Improvement strategies for major public projects. Int J Manag Proj Bus 2:499–518. [CrossRef]

- Knodel T (2004) Preparing the organizational ‘soil’for measurable and sustainable change: business value management and project governance. J Chang Manag 4:45–62. [CrossRef]

- Ross JW, Weill P (2002) Six IT decisions your IT people shouldn’t make. Harv Bus Rev 80:84–95.

- Turner JR, Keegan A (2001) Mechanisms of governance in the project-based organization:: Roles of the broker and steward. Eur Manag J 19:254–267. [CrossRef]

- Blomquist T, Müller R (2006) Practices, roles, and responsibilities of middle managers in program and portfolio management. Proj Manag J 37:52–66. [CrossRef]

- Bruzelius N, Flyvbjerg B, Rothengatter W (2002) Big decisions, big risks. Improving accountability in mega projects. Transp Policy 9:143–154. [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg B (2014) What you should know about megaprojects and why: An overview. Proj Manag J 45:6–19. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen KR (2013) Governance of the Megaproject. Advice from Those Who’ve Been There, Done That 5:.

- Flyvbjerg B, Holm MS, Buhl S (2002) Underestimating costs in public works projects: Error or lie? J Am Plan Assoc 68:279–295. [CrossRef]

- Locatelli G, Mariani G, Sainati T, Greco M (2017) Corruption in public projects and megaprojects: There is an elephant in the room! Int J Proj Manag 35:252–268. [CrossRef]

- Van Marrewijk A, Clegg SR, Pitsis TS, Veenswijk M (2008) Managing public–private megaprojects: Paradoxes, complexity, and project design. Int J Proj Manag 26:591–600. [CrossRef]

- He Q, Tian Z, Wang T (2022) Performance measurement methods in megaprojects: An analytical review. Int J Proj Manag 40:634–645. [CrossRef]

- Mok KY, Shen GQ, Yang J (2015) Stakeholder management studies in mega construction projects: A review and future directions. Int J Proj Manag 33:446–457. [CrossRef]

- Kumar K, Simpson G (2015) Phronesis as a Paradigm for ICT-enabled Transparency: The Case of the Nicaragua Canal Megaproject. In: AMCIS.

- Wierzbicki M, De Silva CW, Krug DH (2011) BIM–history and trends. In: 11th International Conference on Construction Applications of Virtual Reality. Bauhaus-Universität, Weimar, Germany. pp 3–4.

- Bensalah M, Elouadi A, Mharzi H (2018) Integrating Bim in Railway Projects: Review & Perspectives for Morocco & Mena. Int J Recent Sci Res 9:23398–23403. [CrossRef]

- Smith P (2014) BIM implementation–global strategies. Procedia Eng 85:482–492. [CrossRef]

- Suchocki M (2017) THE BIM-FOR-RAIL OPPORTUNITY. In: Garrigos AG, Mahdjoubi L, Brebbia CA (eds) Building Information Modelling. pp 37–44. [CrossRef]

- Li Y-W, Cao K (2020) Establishment and application of intelligent city building information model based on BP neural network model. Comput Commun 153:382–389. [CrossRef]

- Tang L, Chen C, Tang S, et al (2017) Building Information Modeling and Building Performance Optimization. Encycl Sustain Technol. [CrossRef]

- Sacks R, Eastman C, Lee G, Teicholz P (2018) BIM handbook: A guide to building information modeling for owners, designers, engineers, contractors, and facility managers. John Wiley and Sons.

- Eadie R, Browne M, Odeyinka H, et al (2013) BIM implementation throughout the UK construction project lifecycle: An analysis. Autom Constr 36:145–151. [CrossRef]

- Wildenauer AA (2020) Critical assessment of the existing definitions of BIM dimensions on the example of Switzerland. terminology 23:24.

- Smith P (2014) BIM and the 5D Project Cost Manager. Procedia - Soc Behav Sci 119:475–484. [CrossRef]

- Onur AZ, Nouban F (2019) BIM Software in Architectural Modeling. Int J Innov Technol Explor Eng 8:2089–2093.

- Doukari O, Seck B, Greenwood D (2022) The creation of construction schedules in 4D BIM: a comparison of conventional and automated approaches. Buildings 12:1145. [CrossRef]

- Bolshakova V, Guerriero A, Halin G (2020) Identifying stakeholders’ roles and relevant project documents for 4D-based collaborative decision making. Front Eng Manag 7:104–118. [CrossRef]

- Abdulfattah BS, Abdelsalam HA, Abdelsalam M, et al (2023) Predicting implications of design changes in BIM-based construction projects through machine learning. Autom Constr 155:105057. [CrossRef]

- D’Amico F (2020) BIM for infrastructure: an efficient process to achieve 4D and 5D digital dimensions. Eur Transp Eur 77:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Fariq N, Ismail S, Ab Rani NI (2022) EFFECTIVE 5D BIM REQUIREMENTS FOR RISK MITIGATION DURING PRE-CONTRACT STAGE. J Surv Constr Prop 13:12–19. [CrossRef]

- El Khatib M, Khadim S Bin, Al Ketbi W, et al (2022) Digital Transformation and Disruptive Technologies: Effect of Blockchain on Managing Construction Projects. In: 2022 International Conference on Cyber Resilience (ICCR). IEEE, pp 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari S, Alaeddin N, Azhar S, Meadati P Analyzing Barriers and Uniformity of Multi-Dimensional BIM Applications. In: Computing in Civil Engineering 2021. pp 1343–1350. [CrossRef]

- Nicał AK, Wodyński W (2016) Enhancing facility management through BIM 6D. Procedia Eng 164:299–306. [CrossRef]

- Soliman KAFMM (2019) Digital Facilities: A Bim Capturing Reality Framework And Integration With Building Management System.

- Hosamo HH, Svennevig PR, Svidt K, et al (2022) A Digital Twin predictive maintenance framework of air handling units based on automatic fault detection and diagnostics. Energy Build 261:111988. [CrossRef]

- Cruz PJS, Azenha M, Mateus R, et al (2019) BIM as a tool for setting and infrastructure management. In: The 5th International Workshop on UI GreenMetric World University Rankings (IWGM 2019). University College Cork, Cork,14-16 April 2019, pp 1–7.

- Al-Fedaghi S, Al-Huwais N (2018) Toward modeling information in asset management: Case study using Maximo. In: 2018 4th International Conference on Information Management (ICIM). IEEE, pp 117–124. [CrossRef]

- Pyrgidis CN (2022) Railway transportation systems : design, construction and operation, 2nd ed. Boca Raton, Florida : CRC Press.

- Alqatawna A, Sánchez-Cambronero S, Gallego I, Rivas A (2023) BIM-centered high-speed railway line design for full infrastructure lifecycle. Autom Constr 156:105114. [CrossRef]

- Bensalah M, Elouadi A, Mharzi H (2019) Railway Information Modeling RIM. Wiley, Mohammadia School of Engineers of Rabat in Mechanical Engineering, Morocco.

- ISO (2018) ISO 19650-1:2018 Organization and digitization of information about buildings and civil engineering works, including building information modelling (BIM) — Information management using building information modelling — Part 1: Concepts and principles. https://www.iso.org/standard/68078.html. Accessed 18 Sep 2021.

- Bucher D, Hall D (2020) Common Data Environment within the AEC Ecosystem: moving collaborative platforms beyond the open versus closed dichotomy. In: EG-ICE 2020 Proceedings: Workshop on Intelligent Computing in Engineering. Universitätsverlag der TU Berlin, pp 491–500. [CrossRef]

- Özkan S, Seyis S (2021) Identification of common data environment functions during construction phase of BIM-based projects. CIB W78-LDAC 2021.

- Radl J, Kaiser J (2019) Benefits of implementation of common data environment (CDE) into construction projects. In: IOP conference series: materials science and engineering. IOP Publishing, p 22021. [CrossRef]

- Ye X, Zeng N, Liu Y, König M (2023) Smart Contract-Enabled Construction Claim Management in BIM and CDE-Enhanced Data Environment. In: International Conference on Construction Logistics, Equipment, and Robotics. Springer, pp 40–47. [CrossRef]

- Preidel C, Borrmann A, Mattern H, et al (2018) Common data environment. Build Inf Model Technol Found Ind Pract 279–291.

- Ahmed İA, Pehlevan EE (2023) Investigation of Effectiveness of Common Data Environments (CDEs) Utilized in Metro Projects. In: International Symposium of the International Federation for Structural Concrete. Springer, pp 1601–1610. [CrossRef]

- Graham ER, Shipan CR, Volden C (2013) The Diffusion of Policy Diffusion Research in Political Science. Br J Polit Sci 43:673–701. [CrossRef]

- Peters M, Schneider M, Griesshaber T, Hoffmann VH (2012) The impact of technology-push and demand-pull policies on technical change – Does the locus of policies matter? Res Policy 41:1296–1308. [CrossRef]

- Filippopoulos N, Fotopoulos G (2022) Innovation in economically developed and lagging European regions: A configurational analysis. Res Policy 51:104424. [CrossRef]

- GSA B (2007) Guide for spatial program validation—GSA BIM guide series 02. US Gen Serv Adm Washington, DC.

- Edirisinghe R, London K (2015) Comparative analysis of international and national level BIM standardization efforts and BIM adoption. In: Proceedings of the 32nd CIB W78 Conference, Eindhoven, The Netherlands. pp 27–29.

- (2022) National BIM Guide. In: NATSPEC. https://bim.natspec.org/documents/natspec-national-bim-guide. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

- Hosseini Mr, Banihashemi S, Chileshe N, et al (2016) BIM adoption within Australian Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs): an innovation diffusion model. Constr Econ Build 16:71–86. 7: Constr Econ Build 16. [CrossRef]

- Aibinu A, Venkatesh S (2014) Status of BIM adoption and the BIM experience of cost consultants in Australia. J Prof Issues Eng Educ Pract 140:4013021. [CrossRef]

- (2013) Singapore BIM Guide. https://www.corenet.gov.sg/media/586132/Singapore-BIM-Guide_V2.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2024. 2024.

- Kaneta T, Furusaka S, Tamura A, Deng N (2016) Overview of BIM implementation in Singapore and Japan. J Civ Eng Archit 10:1305–1312. [CrossRef]

- Kaneta T, Furusaka S, Deng N (2017) Overview and problems of BIM implementation in Japan. Front Eng Manag 4:146–155. [CrossRef]

- (2014) Railway BIM Data Standard. https://www.buildingsmart.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/bSI-SPEC-Rail.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

- Rui, Wang, Liu B, Wang M, et al (2017) Review and prospect of BIM policy in China. In: IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2017, Republic of Korea, 25–27 August 2017, p 22021. [CrossRef]

- National BIM Standard – United States (NBIMS-US). https://www.nationalbimstandard.org/. Accessed 12 Nov 2023.

- Cheng JCP, Lu Q (2015) A review of the efforts and roles of the public sector for BIM adoption worldwide. J Inf Technol Constr 20:442–478.

- Gov. U (2016) Government Construction Strategy (2016-2020).

- Thompson WR (2017) The UK BIM Revolution.

- Liu Z, Lu Y, Nath T, et al (2022) Critical success factors for BIM adoption during construction phase: a Singapore case study. Eng Constr Archit Manag 29:3267–3287. [CrossRef]

- MINISTRY OF LAND, INFRASTRUCTURE TAT (MLIT) (2021) Guidelines for BIM Standard Workflows (MLIT, 2020). https://www.mlit.go.jp/tec/tec_fr_000079.html. Accessed 12 Nov 2023.

- (2019) Vision for the Future and Roadmap to BIM. https://www.mlit.go.jp/jutakukentiku/content/001351970.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

- (2023) German BIM Implementation Strategy for Federal Buildings. https://www.bimdeutschland.de/fileadmin/media/Downloads/Download-Liste/Hochbau/Masterplan_BIM_Bau.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

- Schumacher R, Theißen S, Höper J, et al (2022) Analysis of current practice and future potentials of LCA in a BIM-based design process in Germany. In: E3S Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences, p 10004. [CrossRef]

- Borrmann A, Hochmuth M, König M, et al (2016) Germany’s governmental BIM initiative–Assessing the performance of the BIM pilot projects. In: Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computing in Civil and Building Engineering. pp 871–878.

- Lu W, Lai CC, Tse T, et al (2018) Big data for construction cost management. Routledge.

- Elghaish F, Abrishami S, Hosseini MR, Abu-Samra S (2020) Revolutionising cost structure for integrated project delivery: a BIM-based solution. Eng Constr Archit Manag. [CrossRef]

- Vigneault MA, Boton C, Chong HY, Cooper-Cooke B (2020) An Innovative Framework of 5D BIM Solutions for Construction Cost Management: A Systematic Review. Arch Comput Methods Eng 27:1013–1030. [CrossRef]

- (2023) RIB- Cost-X. https://www.itwocostx.com/. Accessed 15 Oct 2023.

- Mesároš P, Smetanková J, Mandičák T (2019) The fifth dimension of BIM–implementation survey. In: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. IOP Publishing, p 12003. [CrossRef]

- Lim MY (2020) The impact of using measurement software in the quantity surveying consultancy. UTAR.

- (2023) BexelManager. https://bexelmanager.com/. Accessed 15 Oct 2023.

- Garg A, Alothman A, Vilventhan A (2023) Integration of Building Information Modelling and Facility Management for Metro Rail Project: A Case Study. In: Building Construction and Technology. Springer, pp 113–126. [CrossRef]

- Lenart S, Janjić V, Jovanović U, Vezočnik R (2021) Real-time monitoring and analyses of sensory data integrated into the BIM platform. In: Road and Rail Infrastructure VI; Proc. 6th Intern. Conf. on Road and Rail Infrastructure, Zagreb. University of Zagreb Zagreb, pp 20–21.

- (2023) ARES PRISM (Contruent). https://www.contruent.com/resources/blog/ares-prism-rebrands-to-contruent-with-launch-of-innovative-capital-project-management-software-solution/. Accessed 15 Oct 2023.

- (2023) Cubicost. https://www.glodon.com/en/products/tas-%26-trb-1. Accessed 15 Oct 2023.

- Tan YY (2022) Exploring application of e-tendering in Malaysian construction industry during covid-19 pandemic. UTAR.

- (2023) PriMus. https://www.accasoftware.com/en/cost-estimating-software. Accessed 15 Oct 2023.

- Akinshipe O, Aigbavboa C, Oke A, Sekati M (2021) Transforming Quantity Surveying Firms in South Africa Through Digitalisation. In: Advances in Human Factors, Business Management and Leadership: Proceedings of the AHFE 2021 Virtual Conferences on Human Factors, Business Management and Society, and Human Factors in Management and Leadership, July 25-29, 2021, USA. Springer, pp 255–265. [CrossRef]

- Koseoglu O, Keskin B, Ozorhon B (2019) Challenges and Enablers in BIM-Enabled Digital Transformation in Mega Projects: The Istanbul New Airport Project Case Study. Buildings 9:115. [CrossRef]

- Oh S, Syn SY (2015) Motivations for sharing information and social support in social media: A comparative analysis of F acebook, T witter, D elicious, Y ou T ube, and F lickr. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol 66:2045–2060. [CrossRef]

- Tiwana A, Konsynski B (2010) Complementarities between organizational IT architecture and governance structure. Inf Syst Res 21:288–304. [CrossRef]

- Geliskhanov I (2018) Digital platform: A new economic institution. 2: Qual to Success J 19.

- Wijayasekera SC, Hussain SA, Paudel A, et al (2022) Data Analytics and Artificial Intelligence in the Complex Environment of Megaprojects: Implications for Practitioners and Project Organizing Theory. Proj Manag J 53:485–500. [CrossRef]

- Ansar A, Flyvbjerg B (2022) How to solve big problems: bespoke versus platform strategies. Oxford Rev Econ Policy 38:338–368. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen RK, Ganter SA (2022) The power of platforms: Shaping media and society. Oxford University Press.

- Nag B, Singh J, Tiwari V (2012) Choosing the appropriate project management structure, project financing, land acquisition and contractual process for Indian railway mega-projects: a case study of the Dedicated Freight Corridor project. J Proj Progr Portf Manag 3:39–54. [CrossRef]

- Gaur S, Tawalare A (2022) Investigating the role of BIM in stakeholder management: Evidence from a metro-rail project. J Manag Eng 38:05021013. [CrossRef]

- Ariono B, Wasesa M, Dhewanto W (2022) The Drivers, Barriers, and Enablers of Building Information Modeling (BIM) Innovation in Developing Countries: Insights from Systematic Literature Review and Comparative Analysis. Buildings 12:1912. [CrossRef]

- Faisal Shehzad HM, Binti Ibrahim R, Yusof AF, et al (2022) Recent developments of BIM adoption based on categorization, identification and factors: a systematic literature review. Int J Constr Manag 22:3001–3013. [CrossRef]

- Mayouf M, Gerges M, Cox S (2019) 5D BIM: an investigation into the integration of quantity surveyors within the BIM process. J Eng Des Technol 17:537–553. [CrossRef]

- Btoush M, Haron AT (2017) Understanding BIM adoption in the AEC industry: the case of Jordan. In: IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing, p 12044. [CrossRef]

- Ghaffarianhoseini A, Tookey J, Ghaffarianhoseini A, et al (2017) Building Information Modelling (BIM) uptake: Clear benefits, understanding its implementation, risks and challenges. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 75:1046–1053. [CrossRef]

- Boton C, Cooper-Cooke B, Vigneault M-A, et al (2020) An Innovative Framework of 5D BIM Solutions for Construction Cost Management: A Systematic Review. Springer 27:1013–1030. [CrossRef]

- Moses T, Heesom D, Oloke D (2020) Implementing 5D BIM on construction projects: contractor perspectives from the UK construction sector. J Eng Des Technol 18:1867–1888. [CrossRef]

- Lu Q, Won J, Cheng JCP (2016) A financial decision making framework for construction projects based on 5D Building Information Modeling (BIM). Int J Proj Manag 34:3–21. [CrossRef]

- Amin Ranjbar A, Ansari R, Taherkhani R, Hosseini MR (2021) Developing a novel cash flow risk analysis framework for construction projects based on 5D BIM. J Build Eng 44:103341. [CrossRef]

- Dodgson M, Gann D, MacAulay S, Davies A (2015) Innovation strategy in new transportation systems: The case of Crossrail. Transp Res Part A Policy Pract 77:261–275. [CrossRef]

- May I, Taylor M, Irwin D (2017) Crossrail: a case study in BIM. https://ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/baug/igt/tunneling-dam/kolloquien/2016/May_Crossrail_BIM_Implementierung_ohne_Risiko.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

- Pakhale PD, Pal A (2020) Digital project management in infrastructure project: a case study of Nagpur Metro Rail Project. Asian J Civ Eng 21:639–647. [CrossRef]

- (2023) Leximancer. https://www.leximancer.com/. Accessed 14 Oct 2023.

- Champion J (2016) Rail Infrastructure Planning in Wales–a quick guide. https://research.senedd.wales/media/ho3pynai/english.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

- (2023) Department for Transport (DfT). https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-transport. Accessed 5 Nov 2023.

- (2023) Network Rail. https://www.networkrail.co.uk/.

- (2023) Office of Rail and Road (ORR). https://www.orr.gov.uk/. Accessed 5 Nov 2023.

- (2023) Transport for London. https://tfl.gov.uk/. Accessed 5 Nov 2023.

- (2023) Transport for the North. https://transportforthenorth.com/. Accessed 5 Nov 2023.

- Jiang R, Wu C, Lei X, et al (2022) Government efforts and roadmaps for building information modeling implementation: Lessons from Singapore, the UK and the US. Eng Constr Archit Manag 29:782–818. [CrossRef]

- Ghaffarianhoseini A, Tookey J, Ghaffarianhoseini A, et al (2017) Building Information Modelling (BIM) uptake: Clear benefits, understanding its implementation, risks and challenges. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 75:1046–1053. [CrossRef]

- National BIM Standard NBS (2020) NBS’ 10th National BIM Report.

- Moehler RC, Chan P, Greenwood D (2008) The interorganisational influences on construction skills development in the UK. In: Proceedings 24th Annual ARCOM Conference. pp 23–32.

- Moran M (2017) Politics and Governance in the UK. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Fazekas M, Dávid-Barrett E (2015) Corruption risks in UK public procurement and new anti-corruption tools. Eur J Crim Policy Res 23:245–267.

- (2023) UK - Project Routemap. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1080239/Handbook__-_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

- (2023) PACE (Project Acceleration in a Controlled Environment). https://www.networkrail.co.uk/industry-and-commercial/supply-chain/existing-suppliers/rail-speed/. Accessed 20 Oct 2023.

- Infrastructure and projects Authority Cost Estimating Guidance.

- ISO (2018) ISO 19650.

- Smith S (2014) Building information modelling - moving Crossrail, UK, forward. Proc Inst Civ Eng Manag Procure Law 167:141–151. [CrossRef]

- Floros GS, Ruff P, Ellul C (2020) IMPACT of INFORMATION MANAGEMENT during DESIGN &CONSTRUCTION on DOWNSTREAM BIM-GIS INTEROPERABILITY for RAIL INFRASTRUCTURE. In: ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences. ISPRS, pp 61–68. [CrossRef]

- (2023) Crossrail. https://web.archive.org/web/20221228162655/https://www.crossrail.co.uk/project/routeway/. Accessed 7 Sep 2023.

- (2023) Primavera P6. https://www.oracle.com/au/construction-engineering/primavera-p6/. Accessed 8 Sep 2023.

- BS (2022) BS 1192-4:2014. https://knowledge.bsigroup.com/products/collaborative-production-of-information-fulfilling-employer-s-information-exchange-requirements-using-cobie-code-of-practice?version=standard. Accessed 7 Nov 2023.

- (2009) AEC (UK) BIM Protocol. https://aecuk.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/aecukbimprotocol-v2-0.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

- Crossrail project: Application of BIM (building information modelling) and lessons learned. https://learninglegacy.crossrail.co.uk/documents/crossrail-project-application-of-bim-building-information-modelling-and-lessons-learned/. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

- Chakraborty V, Dutta S (2022) Indian railway infrastructure systems: global comparison, challenges and opportunities. In: Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Smart Infrastructure and Construction. Thomas Telford Ltd, pp 127–140. [CrossRef]

- Raghuram G, Gangwar R (2008) Indian Railways in the past twenty years issues, performance and challenges. Ahmedabad.

- Yadava SKS, Chaudharyb KK, Khatalc SK (2012) Issues and Reforms in Indian Railways. Int J Trade Commer 1:106–125. 1: Int J Trade Commer 1.

- Gupta AK, Ramesh G (2014) Project Management Control System of Infrastructure SPVs: DMRC-A Case Study. In: Public Private Partnerships. Routledge India, pp 20–50.

- Gulati M (2009) The Infrastructure Sector in India. In: INDIA Infrastruct. Rep. http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/IIR2009.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

- (2023) SAP ERP. https://www.sap.com/australia/products/erp/what-is-sap-erp.html. Accessed 8 Sep 2023.

- (2023) Bentley. https://www.bentley.com/.

- (2023) RIB. https://www.rib-software.com/en/home. Accessed 8 Sep 2023.

- (2023) Indian Railways – Estimation guideline. https://indianrailways.gov.in/railwayboard/uploads/codesmanual/EngCode/chapter-vii.htm#701. Accessed 8 Nov 2023.

- (2023) ProjectWise. https://www.bentley.com/software/projectwise/. Accessed 8 Nov 2023.

- (2023) Asset Wise (eB). https://www.bentley.com/software/assetwise-alim/. Accessed 8 Nov 2023.

- (2013) BS PAS 1199. https://www.thenbs.com/knowledge/what-is-the-pas-1192-framework. Accessed 8 Nov 2023.

- (2007) BS 1192:2007+A2:2016. https://knowledge.bsigroup.com/products/collaborative-production-of-architectural-engineering-and-construction-information-code-of-practice?version=standard. Accessed 8 Nov 2023.

- Lindblad H, Guerrero JR (2020) Client’s role in promoting BIM implementation and innovation in construction. Constr Manag Econ 38:468–482. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Fan Q, Liu R, et al (2022) How to benefit from digital platform capabilities? Examining the role of knowledge bases and organisational routines updating. Eur J Innov Manag ahead-of-p. [CrossRef]

- Zutshi A, Grilo A (2019) The emergence of digital platforms: A conceptual platform architecture and impact on industrial engineering. Comput. Ind. Eng. 136:546–555. [CrossRef]

- Abualdenien J, Borrmann A (2022) Levels of detail, development, definition, and information need: A critical literature review. J Inf Technol Constr 27:363–392. [CrossRef]

- Seo MB, Lee D (2020) Development of railway infrastructure bim prototype libraries. Appl Sci 10:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Sun CS, Jiang SH, Skibniewski MJ, et al (2017) A LITERATURE REVIEW OF THE FACTORS LIMITING THE APPLICATION OF BIM IN THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY. Technol Econ Dev Econ 23:764–779. [CrossRef]

- Collao J, Lozano-Galant F, Lozano-Galant JA, Turmo J (2021) BIM Visual programming tools applications in infrastructure projects: A state-of-the-art review. Appl Sci 11:8343. [CrossRef]

- Batselier J, Vanhoucke M (2016) Practical application and empirical evaluation of reference class forecasting for project management. Proj Manag J 47:36–51. [CrossRef]

- Leleur S, Salling KB, Pilkauskiene I, Nicolaisen MS (2015) Combining reference class forecasting with overconfidence theory for better risk assessment of transport infrastructure investments. Eur J Transp Infrastruct Res 15:.

- Themsen TN (2019) The processes of public megaproject cost estimation: The inaccuracy of reference class forecasting. Financ Account Manag 35:337–352. [CrossRef]

- Garland R (2009) Project Governance: A practical guide to effective project decision making, 1st ed. Kogan Page Publishers.

- Ul Musawir A, Serra CEM, Zwikael O, Ali I (2017) Project governance, benefit management, and project success: Towards a framework for supporting organizational strategy implementation. Int J Proj Manag 35:1658–1672. [CrossRef]

- Al Ahbabi M, Alshawi M (2015) BIM for client organisations: a continuous improvement approach. Constr Innov. [CrossRef]

- Fryer KJ, Antony J, Douglas A (2007) Critical success factors of continuous improvement in the public sector. TQM Mag 19:497–517. [CrossRef]

- Bessant J, Francis D (1999) Developing strategic continuous improvement capability. Int J Oper Prod Manag 19:1106–1119. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Aleu F, Van Aken EM (2016) Systematic literature review of critical success factors for continuous improvement projects. Int J Lean Six Sigma 7:214–232. [CrossRef]

- Singh J, Singh H (2015) Continuous improvement philosophy – literature review and directions. Benchmarking An Int J 22:75–119. [CrossRef]

- Alshorafa R, Ergen E (2021) Determining the level of development for BIM implementation in large-scale projects. Eng Constr Archit Manag 28:397–423. [CrossRef]

- Grytting I, Svalestuen F, Lohne J, et al (2017) Use of LoD Decision Plan in BIM-projects. In: Creative Construction Conference, CCC 2017. Elsevier Ltd, pp 407–414. [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg B (2008) Curbing optimism bias and strategic misrepresentation in planning: Reference class forecasting in practice. Eur Plan Stud 16:3–21. [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg B, Hon C, Fok WH (2016) Reference class forecasting for Hong Kong’s major roadworks projects. In: Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Civil Engineering. Thomas Telford Ltd, pp 17–24. [CrossRef]

- Servranckx T, Vanhoucke M, Aouam T (2021) Practical application of reference class forecasting for cost and time estimations: Identifying the properties of similarity. Eur J Oper Res 295:1161–1179. [CrossRef]

- Bekker MC, Steyn H (2007) Defining ‘project governance’for large capital projects. In: AFRICON 2007. IEEE, pp 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Shtub A, Globerson S (2006) Project management: Processes, methodologies, and economics. 清华大学出版社有限公司.

- Kaye M, Anderson R (1999) Continuous improvement: the ten essential criteria. Int J Qual Reliab Manag 16:485–509. [CrossRef]

- Howlett M, Cashore B (2014) Conceptualizing public policy. Comp policy Stud Concept Methodol challenges 17–33. [CrossRef]

- Lipsmeier A, Kühn A, Joppen R, Dumitrescu R (2020) Process for the development of a digital strategy. Procedia Cirp 88:173–178. [CrossRef]

- bimforum.org (2023) Level of Development Specification. https://bimforum.org/resource/level-of-development-specification/. Accessed 6 Feb 2023.

- Latiffi AA, Brahim J, Mohd S, Fathi MS (2015) Building information modeling (BIM): exploring level of development (LOD) in construction projects. In: applied mechanics and materials. Trans Tech Publ, pp 933–937.

- ISO (2023) ISO/Information technology — Vocabulary. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso-iec:2382:ed-1:v2:en.

- Amoaha EK, Nguyenb T V (2019) Optimizing the usage of Building Information Model (BIM) interoperability focusing on data not tools. In: ISARC. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction. IAARC Publications, pp 1081–1090.

- Bhuiyan N, Baghel A (2005) An overview of continuous improvement: from the past to the present. Manag Decis 43:761–771. [CrossRef]

- Autodesk I (2023) Autodesk. https://www.autodesk.com/company/autodesk-platform#:~:text=How will Autodesk’s cloud-based,to realize its full value. Accessed 27 Sep 2023.

- Oracle (2023) Oracle Primavera. https://www.oracle.com/au/construction-engineering/primavera-cloud-project-management/service-for-owners-datasheet/. Accessed 27 Sep 2023.

- (2023) Bluebeam. https://www.bluebeam.com/au/. Accessed 27 Sep 2023.

- (2023) ARES PRISM. https://www.contruent.com/resources/blog/ares-prism-rebrands-to-contruent-with-launch-of-innovative-capital-project-management-software-solution/. Accessed 27 Sep 2023.

- Bentley S (2023) OenRail. https://www.bentley.com/software/openrail-conceptstation/. Accessed 27 Sep 2023.

- The American Institute of Architects (AIA) (2013) G202-2013 Project BIM Protocol. https://www.aiacontracts.org/contract-documents/19016-project-bim-protocol. Accessed 18 Sep 2021.

- Gigante-Barrera A, Dindar S, Kaewunruen S, Ruikar D (2017) LOD BIM Element specification for Railway Turnout Systems Risk Mitigation using the Information Delivery Manual. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 245:42022. [CrossRef]

- BIM Forum (2021) LEVEL OF DEVELOPMENT SPECIFICATION. https://bimforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Supplement-to-LOD-Spec-2021-2022-12-29.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

- Akob Z, Zaidee M, Hipni A, Koka R (2019) Coordination and collaboration of information for pan borneo highway (Sarawak) via Common Data Environment (CDE). In: IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing, p 12001. [CrossRef]

- Jaskula K, Papadonikolaki E, Rovas D (2023) Comparison of current common data environment tools in the construction industry. In: Computing in Construction. European Conference on Computing in Construction (EC3).

- Jaskula K, Kifokeris D, Papadonikolaki DE, Rovas D (2022) Common Data Environments in construction: State-of-the-art and challenges for practical implementation. Available SSRN 424 9458.

- Mudholkar V V (2008) Six-Sigma: Delivering Quality to Mega Transportation Projects. In: Transportation and Development Innovative Best Practices 2008. pp 284–289. [CrossRef]

- (2023) California H.Speed rail Authority. https://hsr.ca.gov/about/high-speed-rail-business-plans/2020-business-plan/chapter-6/. Accessed 20 Oct 2023.

- EU-Rail (2022) Governance and Process handbook. https://rail-research.europa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/EU-Rail-Governance-and-Process-Handbook.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2023.

- Department of Treasury and Finance Victoria (2023) GATEWAY REVIEW PROCESS. https://www.dtf.vic.gov.au/infrastructure-investment/gateway-review-process. Accessed 20 Oct 2023.

- American Association of Cost Engineers A (2023) COST ESTIMATE CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS. https://library.aacei.org/pgd01/pgd01.shtml#Table of Contents. Accessed 20 Oct 2023.

- International Cost Management Standard Coalition (2023) ICMS: International Cost Management Standards. I: Cost Management Standard Coalition (2023) ICMS.

- NBIMS-US (2023) The National BIM Standard-United States. https://www.nationalbimstandard.org/. Accessed 20 Oct 2023.

- Office of Projects Victoria (2019) VDAS. http://www.opv.vic.gov.au/Victorian-Chief-Engineer/Victorian-Digital-Asset-Strategy/VDAS-Resources/Frequently-asked-questions/FAQs-Digital-engineering. Accessed 2 Nov 2020.

- Love PED, Zhou J, Edwards DJ, et al Off the rails: The cost performance of infrastructure rail projects. Transp Res Part A Policy Pract 99:14–29. [CrossRef]

- Department of Infrastructure, Transport RD and C (2020) Infrastructure investment response to COVID-19. https://investment.infrastructure.gov.au/infrastructure_investment/infrastructure_investment_response_covid-19/. Accessed 2 Nov 2020.

- Department of treasury and finance - Victoria (2023) High Value High Risk (HVHR) framework. https://www.audit.vic.gov.au/report/high-value-high-risk-2016-17-delivering-hvhr-projects?section=. Accessed 27 Aug 2023.

- VAGO (2016) High Value High Risk 2016–17: Delivering HVHR Projects. D: (2016) High Value High Risk 2016–17.

- Office of Projects Victoria (2019) Victorian Digital Asset Strategy.

- Chen Y, Jupp J (2022) Exploring the Nexus between Digital Engineering and Systems Engineering and the Role of Information Management Standards. In: Australasian Universities Building Education Association Conference.

- Astralian Government, Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development C and the A (2023) Guidance Note 3A - Probabilistic contingency estimation.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).