1. Sustainability – A ‘Prospective’ Introduction

Water is not just a ‘nice to have’. People generally cannot survive without water beyond a few days. Given the situation of exponential growth of the world’s population and the precarious nature of water availability due to concerns such as climate change (e.g., increasing intensities of rainfall events, storm surges, and hurricanes), drought, and the increasing scarcity of accessible potable water, sustainability for its many dimensions is becoming very challenging. Nevertheless, maintaining water sustainability must be recognized as a recurring issue that will become increasingly difficult in the future.

Lack of water has profound implications for the many needs of urban regions. Sustaining an acceptable and functional situation is essential. To be specific, water supply sustainability for urban areas clearly needs ongoing and significant improvements, a situation which is becoming increasingly challenging. Developing more suitable/livable urban areas is also becoming increasingly difficult due to ‘exploding’ populations and rural-to-urban migrations. The result is that to proceed in a positive direction to improve the sustainability of water quantity, there needs to be both improved assessment procedures and an improved understanding of the issues. Sustainability dimensions can be improved by developing feasible management strategies to attain sustainable goals by learning from examples of ‘what has worked’ and ‘what has not’. The intent herein is to provide some recent examples to describe how water sustainability conditions became challenging, examples of what might be improved, and, equally important, the merits of identifying the pitfalls experienced in some locations that have ended up detrimentally.

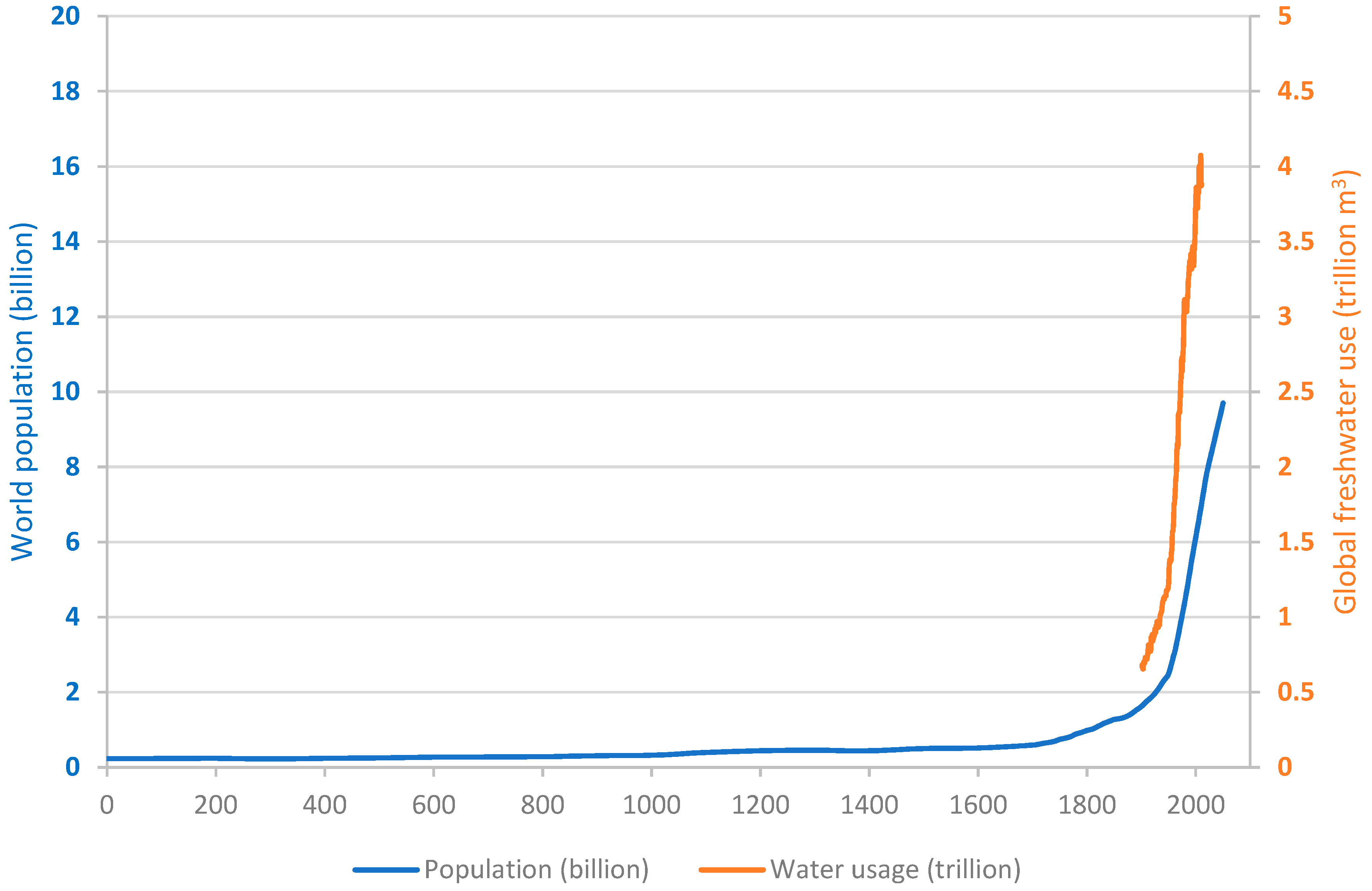

Insights into Earth’s growing water crises are realized when recognizing that while the world’s population has doubled over the last 50 years, water use has tripled during this same period.

Figure 1 schematically depicts how rapidly water use has changed in comparison with the world’s population growth. As will be demonstrated in the text which follows, on a global scale, insufficient water sources are not available for replication of a similar tripling of water use being available, as the world population continues to grow. Current predictions estimate a global population growth of 26% – 7.7 to 9.7 billion from 2019 to 2050 – with 68% of the global population expected to live in urban areas [

1]. Hence, the challenges to setting proper water sustainability goals are enormous.

Clearly, part of the issue of sustainable water availability requires improvement in recognizing the delicate balance between having sufficient water for the intended purpose(s) while avoiding inappropriate quantities (e.g., due to drought and/or flooding). The ability to meet future demands requires an understanding of the trends of water availability, and not relying upon simple historical trends. Instead, there must also be understanding of issues that need to be considered going forward where water availability is a serious issue. While attaining ‘Sustainability for Everyone’ is desirable, deteriorating both water quality and quantity; these are increasingly becoming enormous challenged [

4]. From the water sustainability perspective, this paper describes approaches and challenges that have occurred, and lessons learned that can be utilized for future guidance.

2. Lessons Learned – A ‘Retrospective’ Introduction

This section provides insights describing some historical examples showing responses that helped at the outset but resulted in diminished future opportunities for sustainability. People worldwide must learn from previous approaches to ensure successful water quantity management in a sustainable manner. Specifically, an example is used to demonstrate that what was a grave issue six decades ago, the approach adopted has now become a different issue involving the role of water, namely, the food crisis in the 1960s in India. The pathway followed in India provides a significant opportunity to understand the response adopted to meet irrigation needs was insightful but, as a result of the continuation thereof, has now created more extensive problems.

2.1. Enhanced Water Availability Obtained By Relying On Groundwater Is Now A Very Different Issue

Approximately 60 years ago, the ‘1966 Drought’ drove India into a catastrophic situation with widespread hunger and limitations on water availability for irrigation purposes to ensure sufficient food production. Since hungry mouths could be filled only by food aid, a record high demand was reached, namely 10 million tons of food. Foreign experts opined that India could never feed itself. On January 23rd, 1966, The Hindu newspaper published an alarming article that indicated “Thirty million people in India face ‘dire stress’ in getting food” and “India was surviving from ship-to-mouth”. Fortunately, the development of tube wells was instrumental in making feasible, dramatic improvements to extract water from groundwater for irrigation purposes. The tube wells led to substantial improvements in the ability to pump groundwater, making water available for irrigation and responding to the enormous starvation issues.

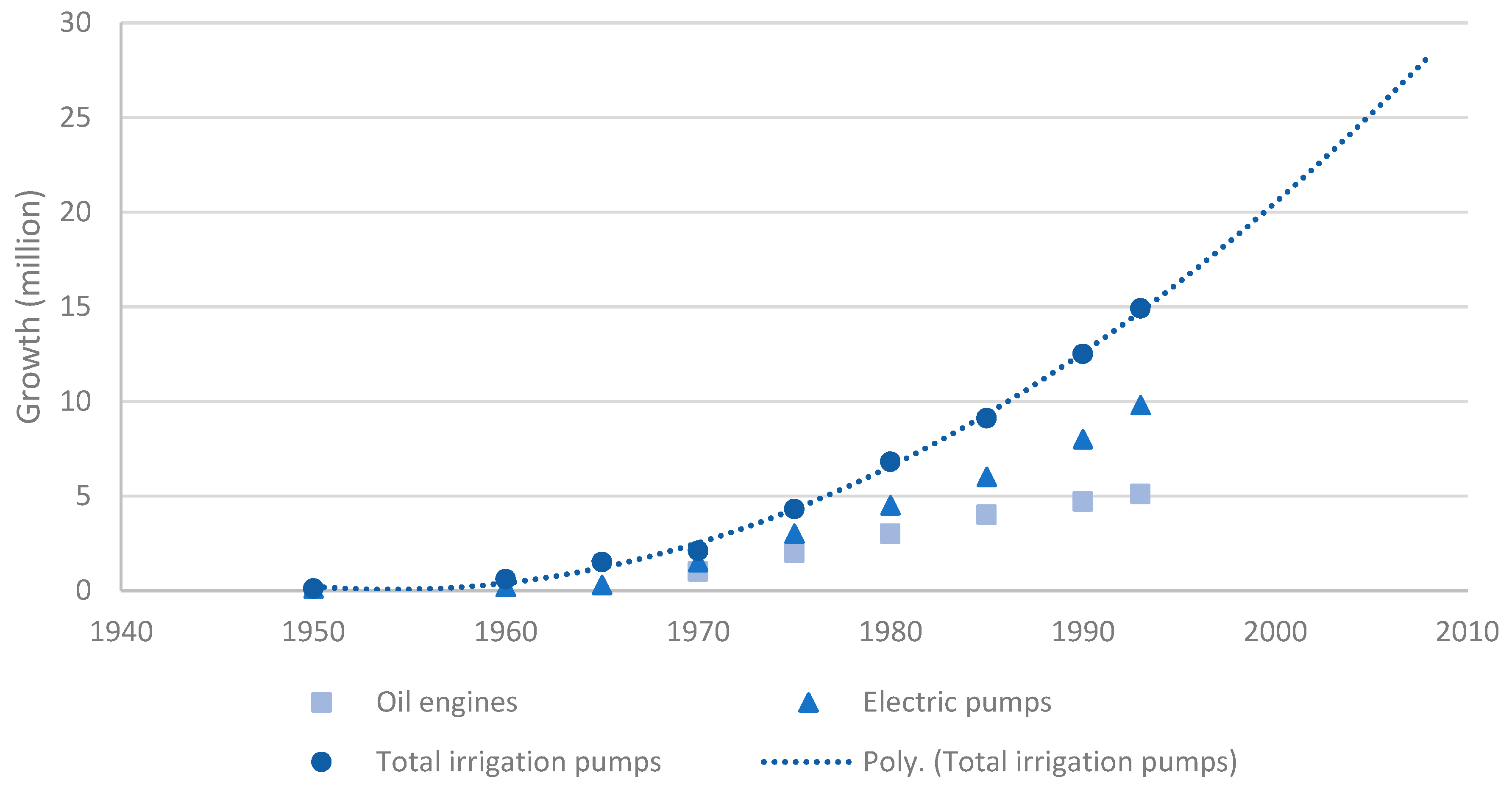

The situation in 1966 was enormously improved by adapting tube wells powered by combinations of diesel and electricity. As indicated in

Figure 2, with rapid increases in the number of irrigation pumps being implemented in India, the response was astounding. The circumstances involving irrigation water through tube well pumping largely improved irrigation quality and made water available via access to groundwater, which offset massive starvation.

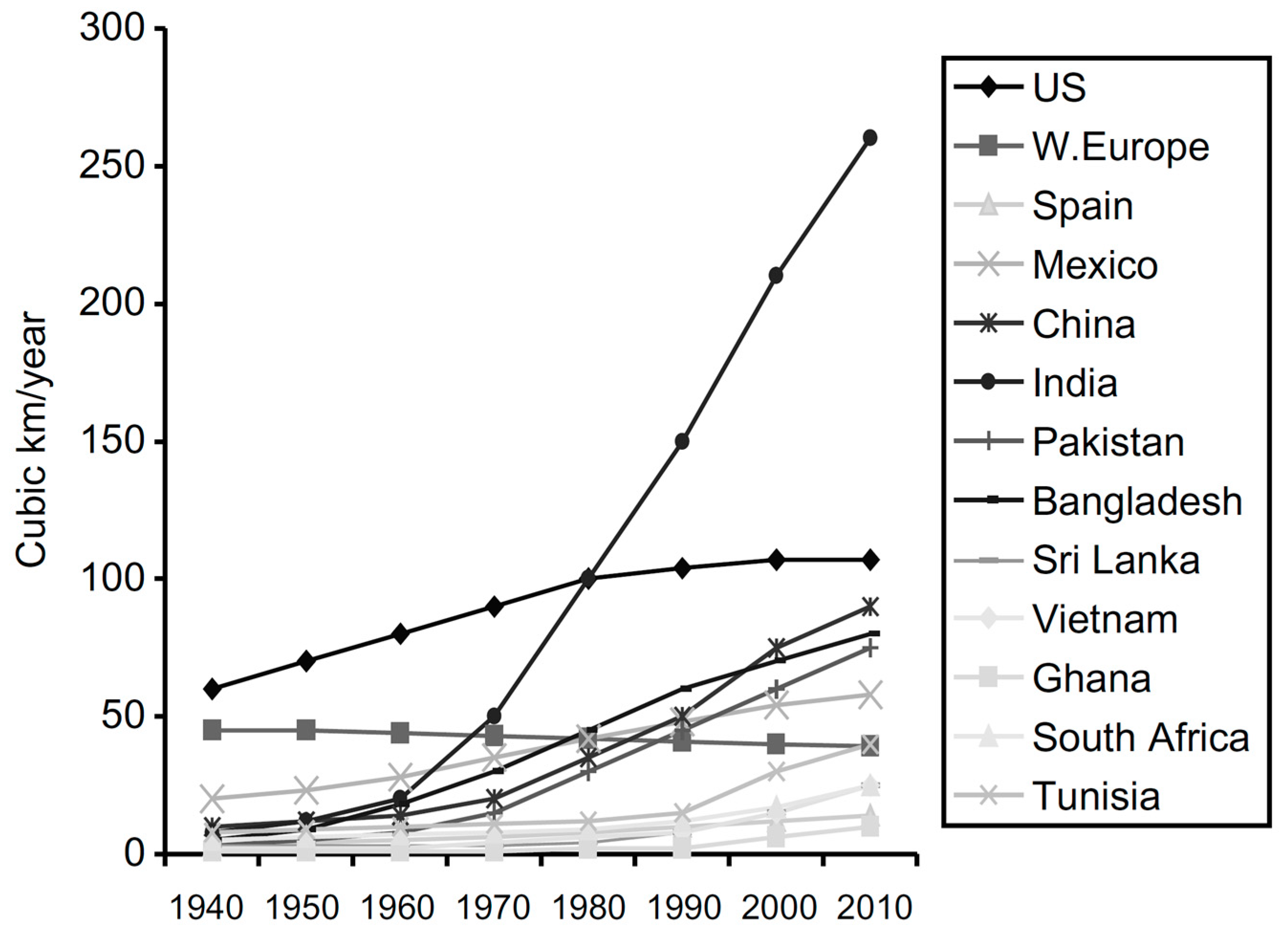

With India proceeding to increase development in groundwater withdrawal, huge improvements in food production in the 1960s and onward (see

Figure 3 for the dramatic rise in groundwater withdrawals for irrigation). However, the ability to access groundwater with continued withdrawals is now been determined as no longer feasible [

6].

As a means of understanding the implications of groundwater depletion: ~70% of groundwater applied for irrigation of crops is lost through evapotranspiration, making this a consumptive use. Only ~30% of irrigation water percolates below the root zone and is added back to groundwater, resulting in groundwater depletion. Meanwhile, most of the infiltrating water to the root zone ultimately discharges from the shallow ground-water zone to nearby creeks/rivers [

8]. Therefore, only minor amounts of irrigation water travel to deep groundwater, with the consequence of declining deep groundwater levels. At present, with an improved understanding of the interconnections between various hydrologic components, it is now realized that the practices shown above for extensive irrigation were detrimental to local groundwater resources [

9].

Declining groundwater levels translate to the need to deepen the extraction wells to ensure continued groundwater access for pumping until, ultimately, the results are depleted groundwater resources. Hence, the initial opportunity to adopt the new initiative (tube wells) was an enormous success, but the continued reliance upon the groundwater ended up causing major issues, including:

Groundwater levels dropped dramatically over time to the present day, to the point where groundwater resources have been depleted essentially throughout India;

The water extraction rate continued to increase over time. In some locations in India, electricity costs of water extraction were not passed on to the farmers. Hence, excessive amounts of pumping were uncontrolled and not regulated, resulting in further lowering of groundwater levels;

Groundwater levels declined over time, causing land subsidence and building and bridge foundations cracking. Subsidence in India now exceeds coastal, absolute sea level rise by a factor of 10 for many coastal cities. Subsidence issues will continue to grow with time and cannot be reversed;

Farmers and industries are the primary users and abusers of groundwater. However, initiatives to control groundwater abstraction rely to a large ex-tent upon government authorities;

As depth-to-groundwater increases, groundwater quality typically results in increasingly poor water quality and requires substantial increases in electricity expenditures due to the depths involved. The inability to continue to pump groundwater (for both irrigation and for water supply to cities) have, in the 2020s, reached issues such that groundwater levels in many locations in India have become depleted.

The need to understand the expanded view of groundwater sustainability is readily apparent. This approach also serves as an example of what worked in the past may represent widespread catastrophic consequences later. Extensive reliance upon groundwater pumping in India has resulted in 21 major cities in India poised to run out of groundwater very soon (e.g., New Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad, Pune, etc. [

10]). Parts of Kolkata are subsiding at a rate of 13.5 mm/year, for which the consequences are profound such that for every 1 m drop in groundwater, the average subsidence is 33mm.

Mass protests by farmers are again taking place in India, but the above situation is not unique. Farmers have a strong sense of ownership of whatever groundwater lies under their farms (this type of circumstance is replicated in many places, including in California [

8,

11]). Farmers resist controls imposed by government departments on their groundwater pumping practices. In many respects and many locations, opportunities to control the degree of pumping are only possible at the village level through mutual surveillance, social pressure, and regulations.

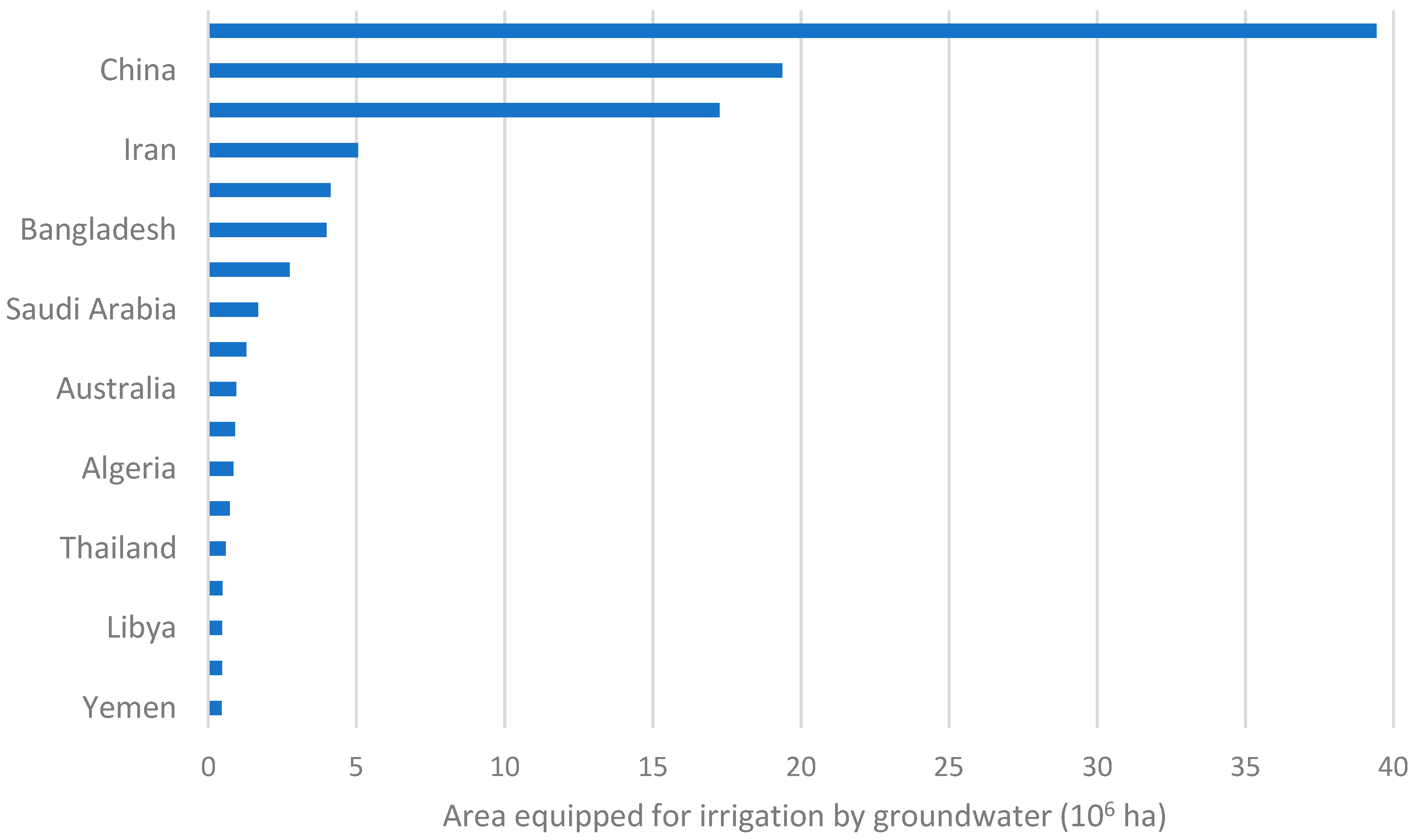

The result of extracting water for irrigation and serving India’s large population is that India became, and continues to be, the largest user of groundwater of any country in the world (see

Figure 4, where the second largest user is using nearly two times less than India). The world population is expected to exceed 9.6 billion by 2050, and food production must be raised by 70 % to feed the growing population [

12]. It can be anticipated from present trends that a major part of the needed supplementary food will have to come from irrigated agriculture. Nevertheless, increased irrigation demands due to climate change will have severe implications for water resources, especially in regions already under water stress. This is because, as an example, climate change will result in elevated temperatures and thus more evapotranspiration which translates to increased needs for irrigation [

13]. This positive feedback loop that connects population, food, irrigation, and groundwater will bring more pressure to water sustainability which is already on the brink. As demonstrated in the 1960s example in India, the tipping point of water sustainability can be quickly reached if there is an absence of proper resource management.

2.2. Changes of Diets and Growth of Populations in Urban Areas

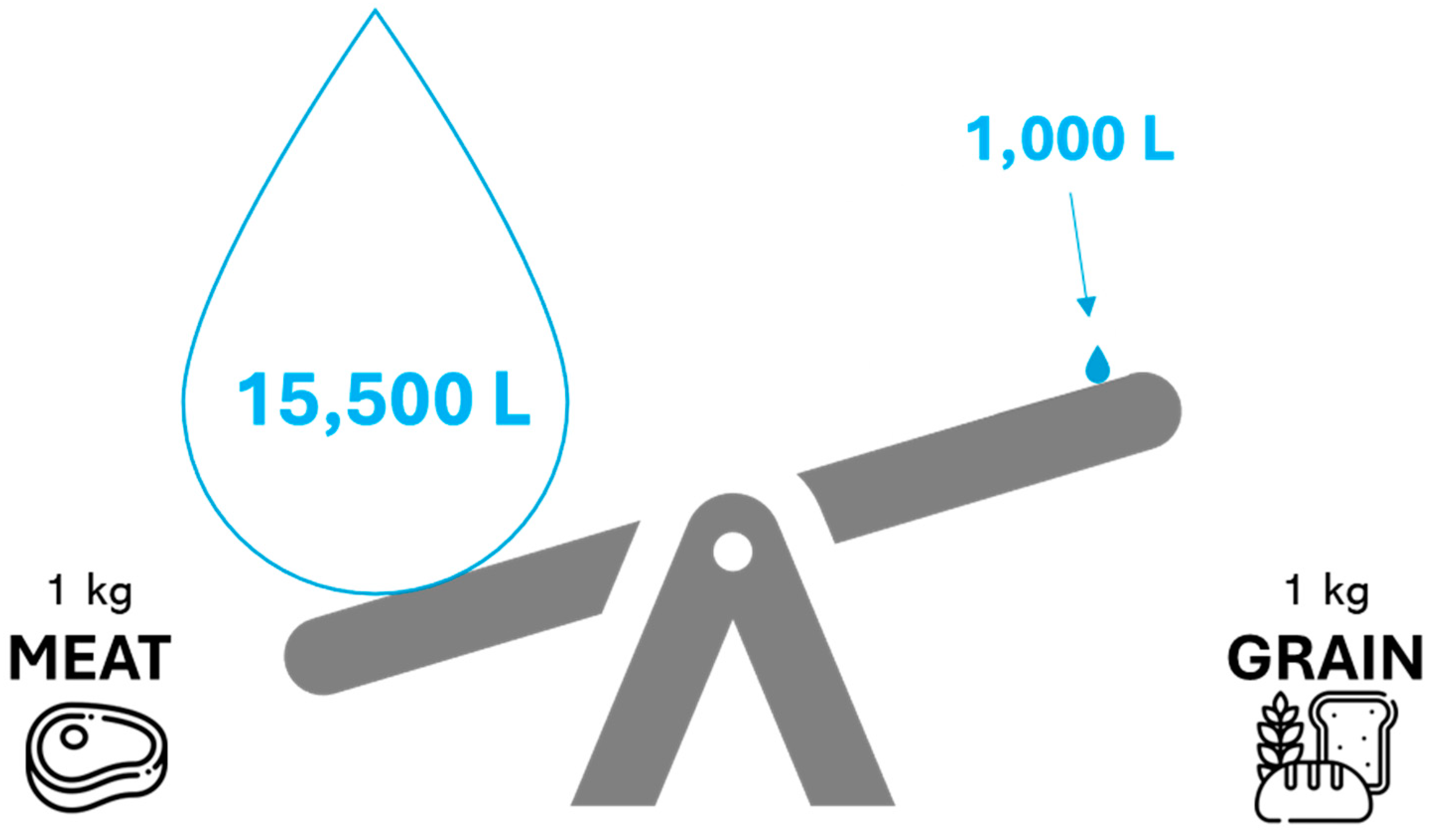

Water demands are also changing in response to people’s dietary adjustments. For example, in China, habits and diets have made dramatic transitions over time where meat consumption in China changed from 20 kg/yr in 1985 to 50 kg/yr in 2009 [

15]. This type of change in dietary adjustment continues with great resistance on the part of people to re-turn to previous eating-habits. For this type of reason, ‘sustainability’ requires adjustments in water usage levels (

Figure 5).

The changes in diet are causing issues in increased water stress and decreased water availability throughout the world, as illustrated in the example in

Figure 5. Hence, the importance of supply issues arising from increasing urbanization causing localized levels of water stress, has resulted in changes in water usage: from 400km

3 per year per billion people in 1965, to 600km

3 per year per billion people in 2015 [

16]. As a result of population growth with its associated adjustments in diet and energy implications, the increased challenges to manage water sustainability are apparent and profound.

Another important example which demonstrates how water demands are changing exists in the Zambezi River basin. Due to the dramatic population growth in Zambezi, water demands for irrigation have dramatically increased. This has resulted in water demands in 2025 projected to be 1500km

3 annually, or 60% more than volumes in 2015. For this circumstance, Zhang and McBean [

17] indicate that while climate change in the Zambezi basin in Africa is projected to involve 25% of the projected impact on future water availability of river water, 75% of the projected water security needs are attributable to population increases (e.g., they are related to food, energy, and dietary habits due to the increased population). Hence, population increases in the Zambezi basin represent a substantially greater threat to water security than climate change. While many people criticize developed countries as responsible for climate change, it is the population increases in the Zambezi basin that are predominantly exacerbating water security issues.

In parallel, water sustainability challenges not only arise from insufficient water access for irrigation but also from massive withdrawals of water for growing megacities’ populations. In India, massive withdrawal by cities to meet the urban water demands as well as for foodstuff irrigation as referred to above, has resulted in many megacities running desperately short of water [

2].

Some of the sustainability issues that need to be addressed are arising in localized areas such as megacities (herein defined as cities with more than 10 million population). Most megacities are experiencing massive migration from rural areas to urban areas, making this type of migration extensive. In 2016, more people were already living in cities than in rural areas, and 70% of the world population will live in urban centers by 2050 [

18].

2.3. Impacts on Water Needs Due to Water Diversions and Limited Access

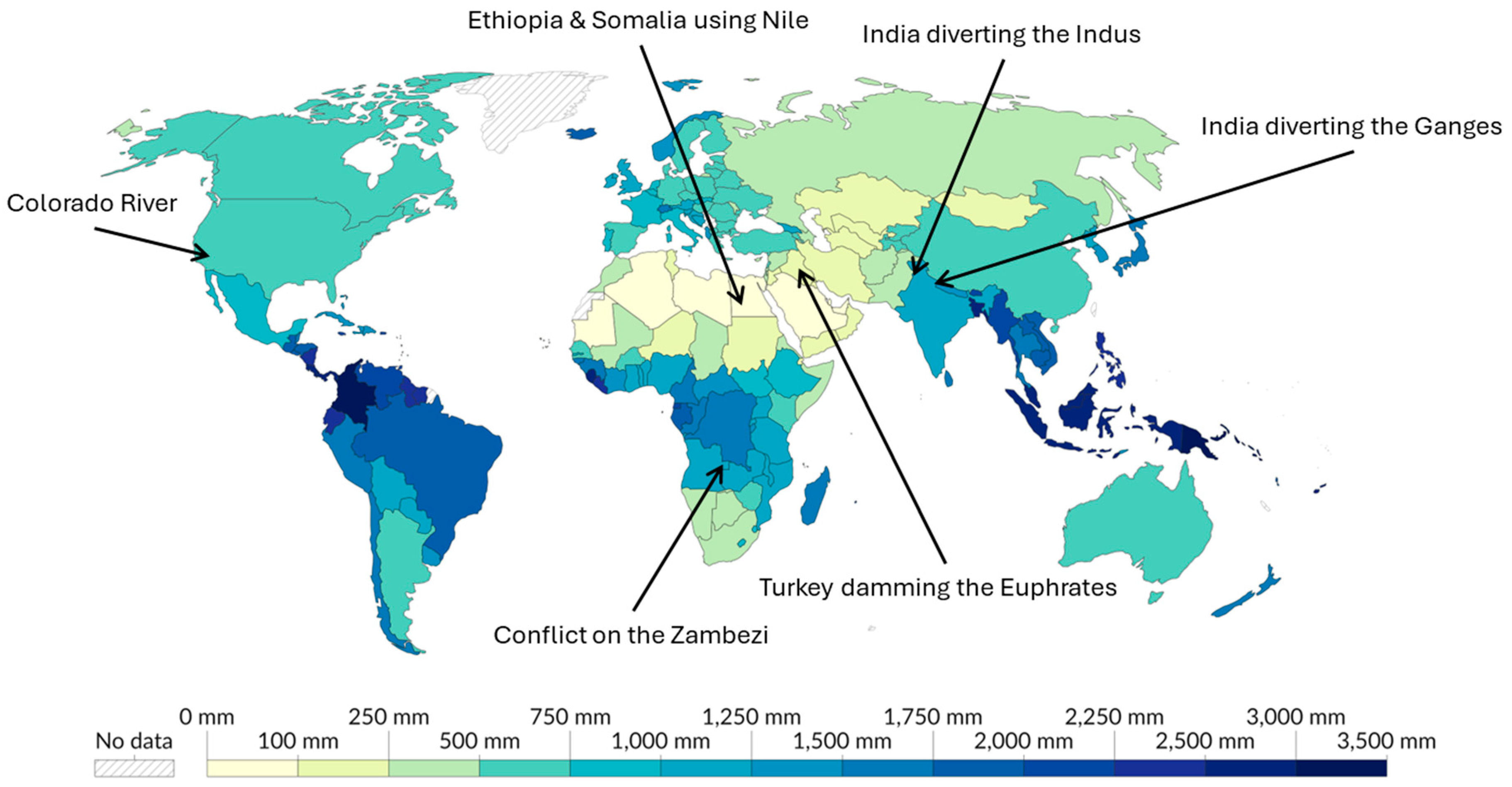

2.3.1. Water Diversions by Upstream Countries

As sustainability of available water quantities in many regions of the world is be-coming increasingly challenging, in many locations water resources are being diverted from an international watercourse rather than a continuation of letting water flow into downstream countries. Water diversions frequently occur where upstream countries utilize impoundment/diversion of water for their purposes. For example, Turkey constructed a series of reservoirs to enhance foodstuff growth in eastern Turkey, creating chaos for downstream countries such as Iraq in the Tigris-Euphrates. Some examples of countries involved in water diversions are depicted in

Figure 6, although many more examples of diversion could be added, some of which are briefly described below.

Of similar character but alternatives to the above are challenges of water diversions described in [

16,

20,

21]. These examples are important as they demonstrate the need for substantial negotiations between countries/regions to arrange water-sharing (e.g., be-tween Afghanistan and Pakistan). The result is that water usage is becoming increasingly less sustainable in many countries/regions. Further, water diversions are becoming increasingly common much to the chagrin of downstream communities/countries. For instance, in the case of the Amu Darya, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan will face the negative impacts of water diversions [

22]. The possibility of any party reaching agreements on sharing water is surprisingly low. Meanwhile, such conflicts exacerbate the continuing catastrophic impacts on the Aral Sea. This can be seen from the Amu Darya, where many locations along this river use water to grow cotton in a desert [

20].

Additional examples of surface water diversions resulting in significant impending shortfalls for downstream countries include (i) shortfalls in Egypt, due to increased water utilization in Ethiopia, and (ii) diversion of water from the Ganga River in India, supplying water to Kolkata to decrease subsidence in the city, but resulting in major issues in downstream areas of the Ganga in Bangladesh. Meanwhile, Bangladeshis are reporting the need to re-drill groundwater withdrawal pumps due to the lowering of groundwater levels in Bangladesh [

23].

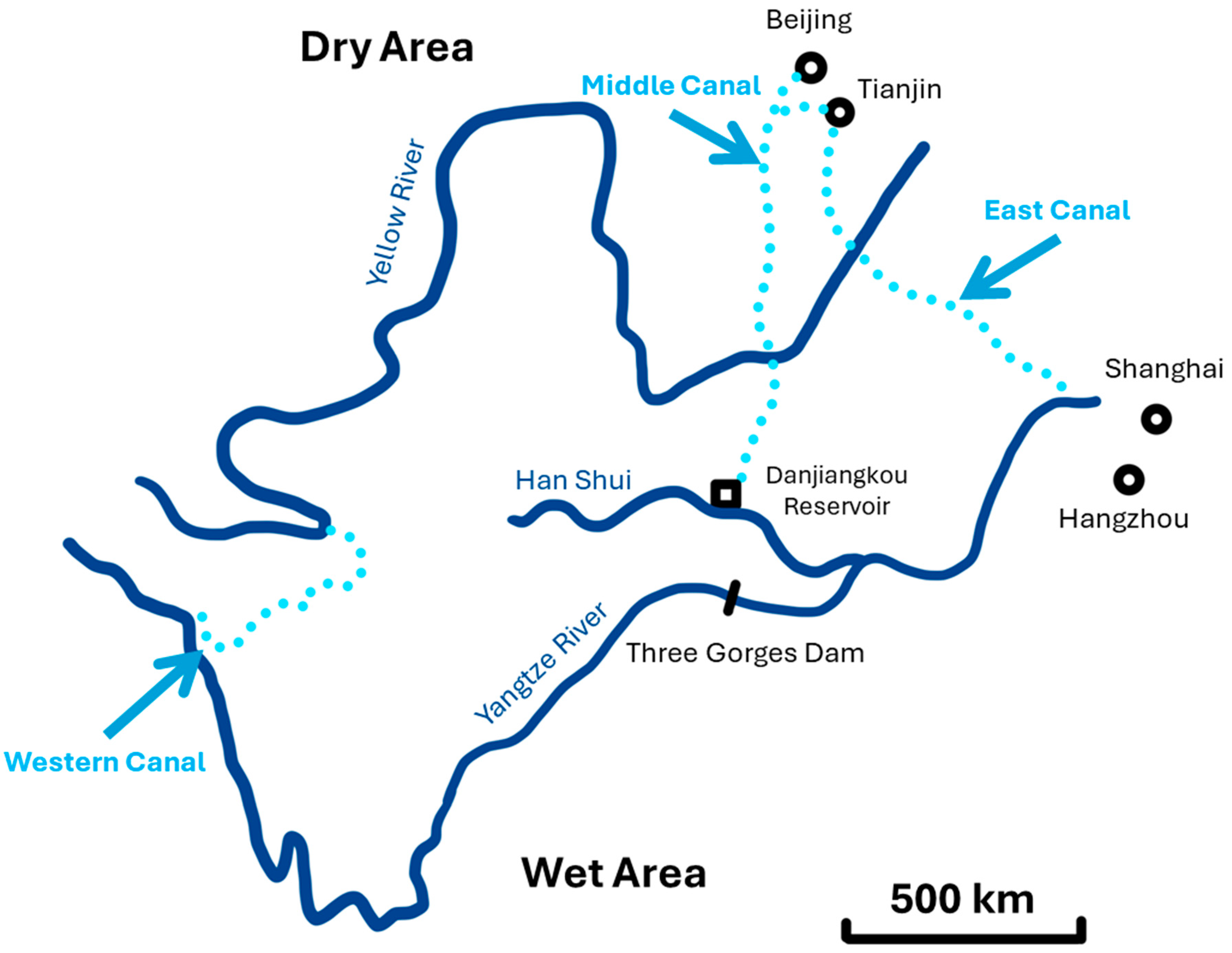

The opportunity has existed in some locations to initiate water diversions from areas with excess within the same country, to areas of shortfall. For example, through the construction of the South-to-North Canal system, China is approaching the successful completion of massive water movement from southern areas where there is excess water available, to the water-short areas in northern China (e.g., to Beijing and Tianjin area). The costs for the South-to-North Canal system are estimated to be US

$20 billion, and an expected construction time of 50 years, involving 300,000 population resettlements.

Figure 7 illustrates the schematic of the South-to-North Canal system, which involves transferring water from wet, southern parts of China to dry, northern areas. Although this is a domestic project, it demonstrates the feasibility of diverting water from ‘water sufficient’ to ‘water scarce’ regions. To implement similar projects between countries/regions, there will necessarily be lengthy negotiations between multiple stakeholders. Under the pressure of climate change, such projects must commence within or beyond the political boundaries [

24].

2.3.2. Water Diversions to Urban Areas from Farming Areas

The results of imposed water diversions also apply to megacities since water supply issues create challenges to obtain sufficient water to serve citizens and industries in these megacities. The result in many situations involve diversions of water away from irrigating crops. The situations from one to another are different but, in many respects, similar. Sustainability is a major issue for both segments: megacities and rural populations.

The result is that two-thirds of the world population live in water-stressed regions, and an estimated 1.8 billion people will live in areas plagued by water scarcity. As apparent from the above, sustainability is multi-faceted, with many dimensions inter-weaved between and affecting each other.

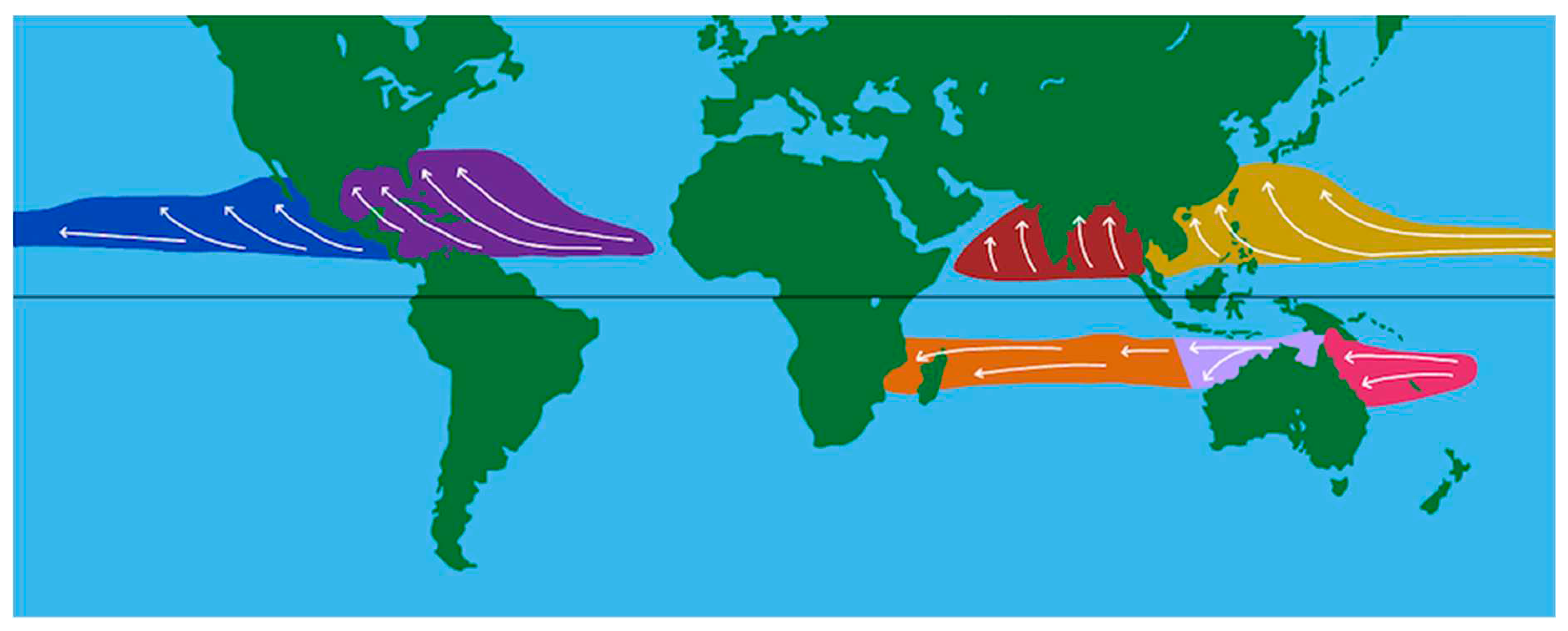

2.4. Sustainability for Coastal Cities

Many coastal cities have undergone transformation from modest densities to become mega-cities, for circumstances including facilitating shipping, recreation, and visual appeal/tourism. Currently, 12% of the world population lives in the low-elevation coastal zone (within 10 m of elevation difference from ocean elevation) [

25]. However, while of enormous interest, many of the 12% of the world population living in the coastal regions are frequently in the pathways of extreme storms. The seven lines of hurricane pathways, as indicated in

Figure 8, show that regions close to the equator are among the most likely to be impacted by hurricanes (Note: the term ‘hurricanes’ is used herein, although an array of names for the same phenomena exist).

Examples of the inability/challenges to protect against hurricanes are described in [

27,

28]. The important takeaway in terms of protecting the coastal cities (many of which are megacities) is that the available opportunities to protect coastal cities against damage and salinity intrusion are extremely difficult. For example, when in the pathway of hurricane, the ability to construct a wall of 7 m in height to protect the cities is infeasible [

29].

2.5. Desalination of Sea Water in Response to Water Needs

Seawater desalination is feasible for coastal cities but expensive, making desalination as a water supply option only available to wealthy countries. It is also important to note that alerts are now being raised for cities employing desalination, because the wastewater (after the water fit for human consumption is removed from seawater) is denser than ambient ocean water. As a result, when the denser wastewater is discharged back into the ocean, changes in ocean currents (and water quality) arise in the receiving area of the oceans, which are only starting to be understood and not yet appropriately dealt with.

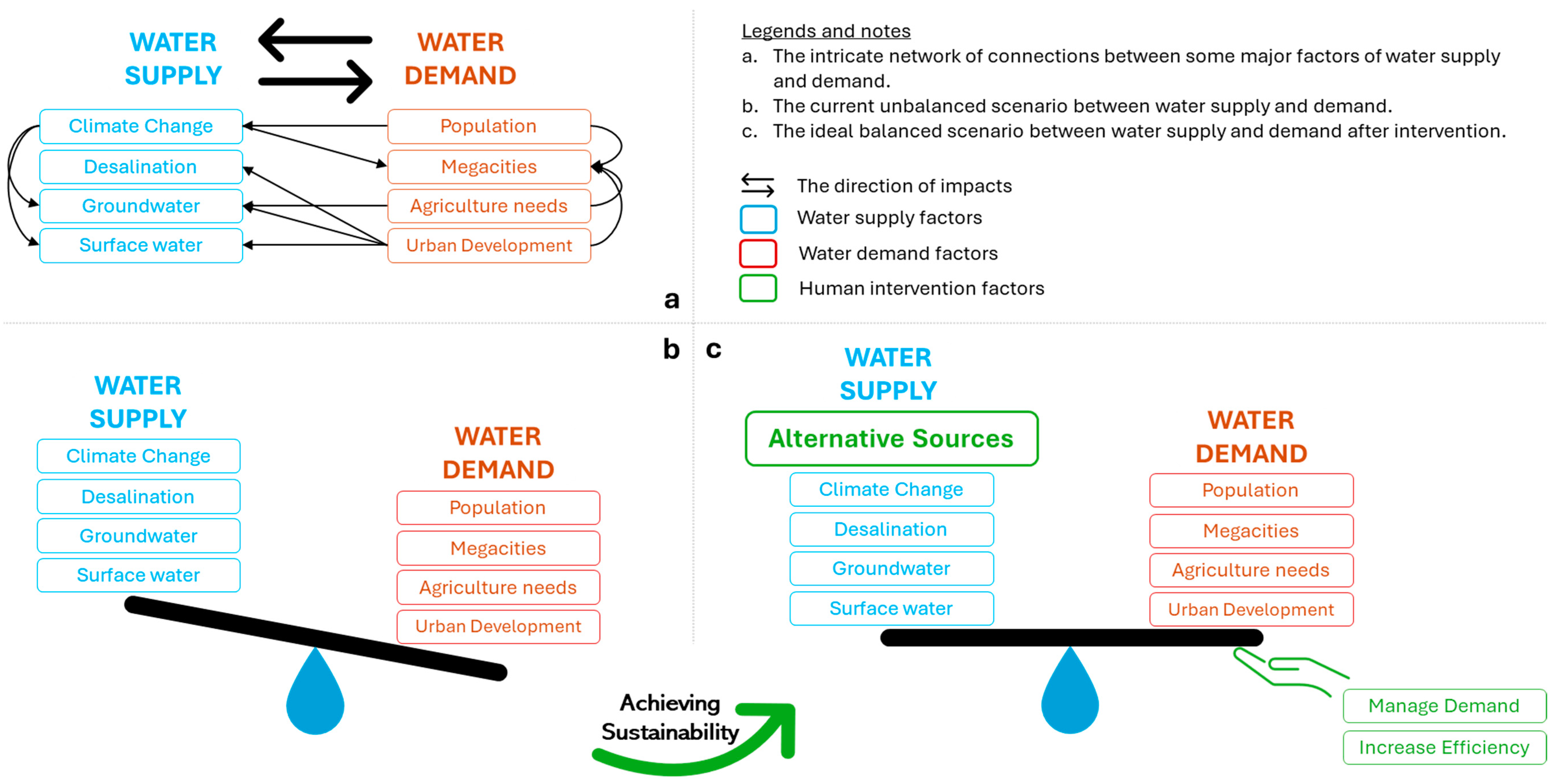

3. Framework of Sustainability

As apparent from the preceding sections, sustainability is multi-faceted, with many dimensions influencing the ability to characterize sustainability [

25]. Clearly, adding a sustainable perspective to water issues is complicated due to interference with efforts/initiatives to attain sustainability, and much uncertainty needs to be characterized. In that same context,

Figure 9 indicates a framework for elements needed for sustainable water management. The key components illustrate the contributing features which need to exist toward managing the water needs to meet water demands. This translates to a series of issues that need to be resolved to identify potential options before improving water quantity sustainability in urban regions.

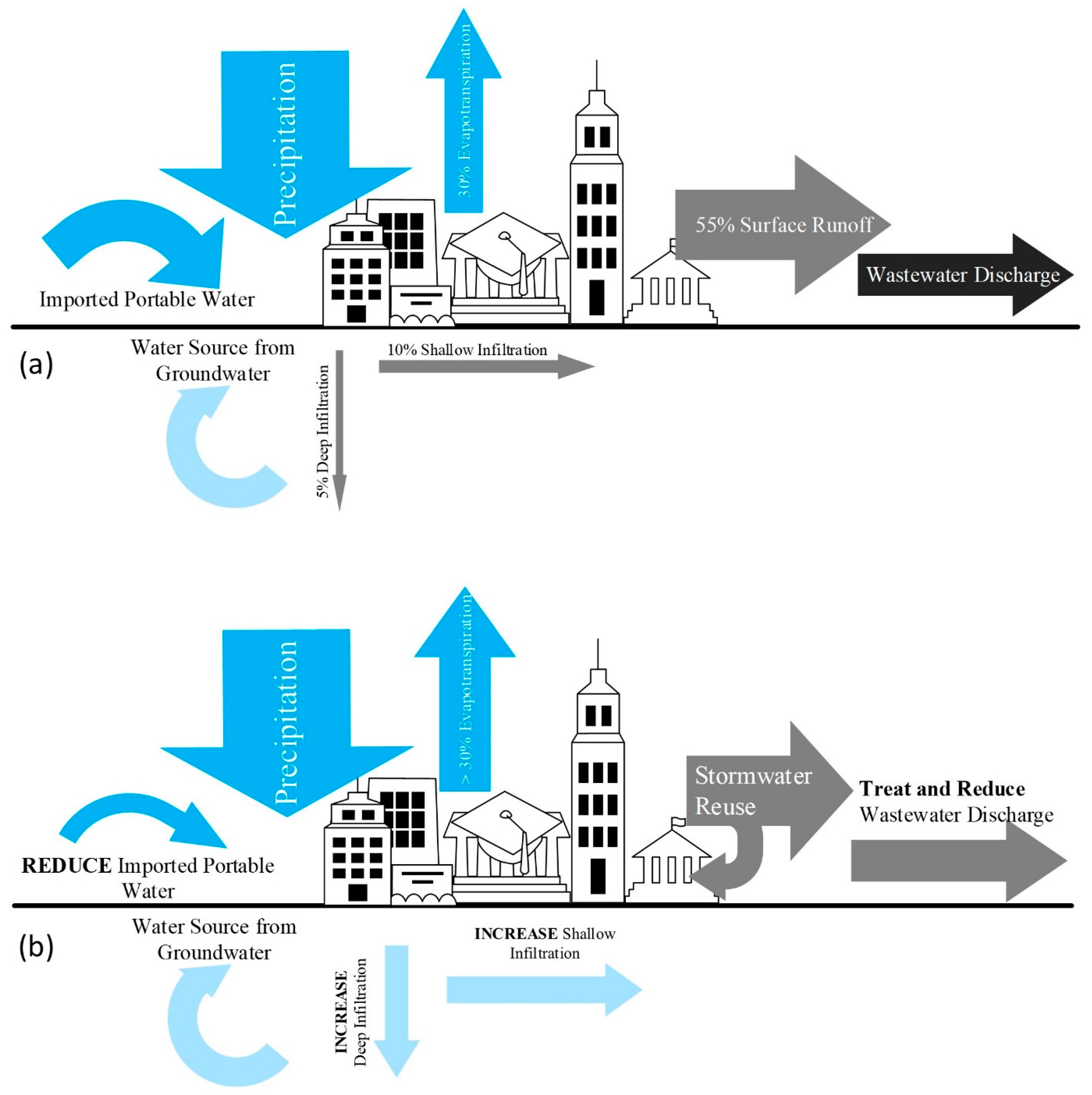

The keys to sustainability of water associated with cities rely upon the transformation of water movement to/from cities as demonstrated in

Figure 10. Without incorporating the elements of sourced water, wastewater treatment, and the matching of groundwater withdrawals to the means of replenishing groundwater sources, will mean that the sustainability of water quantity as relevant to cities is destined to fail. Clearly, the magnitudes of each of the components of water source/receptor will change from one location to another, but the key to the ‘One Water’ approach is that the procedure serves as an effective means of tracking the quantities/qualities and is the key to whether the sustainability of the water quality issues for a city can be accomplished. Further enhancements reflecting components of climate change also need to be considered and incorporated into long-term planning, to ensure the success of the sustainability of water quantity issues can be managed. An important aspect of the One Water approach is that it can be an effective means of portraying to politicians/non-technical people as to how the planning elements for the future can be depicted to improve their understanding of how issues need to be addressed [

9].

As aforementioned, by 2050, 70% of the world population will live in urban areas. This will include dramatic growth in the number of megacities. Clearly, the issue of whether there are sufficient water sources is enormous. In other words, will there be sufficient water? Conditions and opportunities to encourage groundwater replenishment are not universally applicable, but innovative approaches do exist. Examples include:

For example, in Los Angeles, California, with a regional population of approximately 20 million people but in an area where the rainfall is only about 32 cm/yr, the ‘rocky’ aquifers under Los Angeles are used as an ‘underground reservoir’. This magnitude of wastewater is first being pursued to treat the wastewater near the ocean-front, followed by pumping the treated water back to the eastern edge of Los Angeles, then followed by ground-water recharge of the treated wastewater, and finally, followed by extraction and, again, water treatment.

In Singapore, due to concerns with the reliability of their historical source waters coming from Malaysia, they now recover virtually all water that lands on the island country, followed by treatment of the accumulated water and distribution of the treated water back into upgradient groundwater, ultimately being pumped and used for drinking water.

An example of an effective strategy used in Waterloo County, Canada, involves pumping from the nearby Grand River during spring when the water levels in the Grand River are high with discharge into an adjacent former gravel pit. The recharged water becomes part of the groundwater which is then pumped as part of the groundwater supply to the Waterloo region.

Eliat, Israel, is hemmed in between the desert and the Red Sea, and hence, isolated from the rest of Israel, with no natural freshwater. Its drinking water is a combination of desalinated groundwater and seawater. After domestic use turns it into sewage, it is treated and then allocated to farmers, enabling the parched region to support agriculture.

4. Recognizing Water Quality Sustainability Issues for Cities on Coastlines

Coastal cities may face issues such as salinity intrusion into their underlying groundwater, spoiling the aquifer as a water source. This is primarily because wide-spread coastal zone flooding has the potential to result in saltwater infiltration into the soil and groundwater underlying the cities and migration up to nearby river channels, thus contaminating the groundwater. Salinity in groundwater is a massive issue since ocean water has a typical salinity of ~35,000 mg/L whereas, drinking water limitations on salinity are (typically): 600 mg/L (good quality drinkable water), 600-900 mg/L (fair quality), and 900 – 1200 (poor quality). Hence, such intrusion of saline water may seriously damage the usability of groundwater as a resource.

McBean and Huang [

27] described an array of protective measures that may be needed to attain sustainability and protect coastal cities against salinity intrusion [

27,

28]. Issues on the security of water supplies are much more complicated when there is a potential for salinity intrusion into the aquifer when they are being used as a domestic water source.

4.1. The Need to Improve Wastewater Treatment Before Reaching Sustainability

Globally, approximately 80% of wastewater flows back into receiving water eco-systems without treatment or re-use at present [

30]. This indicates the need to treat wastewater to promote appropriate use of wastewater, which represents a major opportunity to use wastewater as a water source. Fortunately, on many occasions, wastewater and stormwater runoff are now recognized as a resource, not as a waste.

Evidence shows that making water resources sustainable requires utilizing wastewater to facilitate productive reuse. Indeed, reuse of wastewater can be multi-faceted, where this could include use as cooling water, or use water injection into an aquifer (e.g., injection into sandy soils, followed by recovery projects such as used in Kakinada, India), or treat and reuse for more beneficial uses [

30]. Given the above, although sufficiently improving the water quality for subsequent use will remain a continuing challenge, there are extensive opportunities to utilize integrated risk management concepts for the future [

31,

32].

4.2. Current Water Sustainability Issues in Urban Areas

Source water protection is an elaborate and complex process that must consider an array of socio-political and technical factors, including jurisdictional considerations, flow and transport of water and contaminants in the natural environment, and building sustainable infrastructures. After the tragic events which occurred in year 2000 in Walkerton, Ontario (see [

27]), the provincial government of Ontario, Canada, took extensive action to ensure protection for the drinking water sources. The result is that the Province of Ontario has now enacted a comprehensive drinking water protection framework so that more than 99.8% of water quality tests meet Ontario’s strict health-based water quality standards [

33].

The circumstances at other locations worldwide vary dramatically, and hence, generalizing urban water sustainability issues is challenging. However, it is clear that the results for different locations are diverse but share some commonalities. For example, Lake Oroomiyeh, Iran, was historically the eighth-largest lake in the world. While precipitation trends decrease and water withdrawals continue to remove water for irrigation prior to arrival into the Lake, the incoming water to Lake Oroomiyeh is declining. As a result, Lake Oroomiyeh is now basically a source of dryland with salt deposits which are then carried by winds to further damage the nearby lands [

34].

4.3. Implications of Groundwater Availability and City Subsidence

Megacities need huge amounts of water. Although sustainability to support the pumping rates needs to be confirmed, groundwater withdrawals have become an important sustainability issue (although continuing withdrawals will result in significant subsidence, as discussed in previous sections). Examples where extraction has exceeded sustainable withdrawals, are listed in

Table 1. For the listed areas where land subsidence has become a major issue are maximum include Jakarta where subsidence 4 m of subsidence in 35 years has occurred, such that 20% of Jakarta is now lower than mean sea level. The implication for Jakarta means that river discharges can only be released to the ocean during low tide periods. The implications are of such a magnitude that the capital of Indonesia is now being moved to the island of Borneo.

Further examples of subsidence are also, unfortunately, all too common, with examples including:

In China, the average total economic loss due to subsidence is ~1.5 billion US dollars annually, and Wuhan is currently experiencing subsidence of 5 cm/year [

35];

Parts of Houston U.S.A. have dropped between 10 and 12 feet since the 1920s in large part because Houston is frequently referred to as ‘a concrete canoe in a swamp’ [

25];

San Joaquin Valley, California, has incurred 8.5 m subsidence in 50 years;

Parts of Mexico City have subsided 40 cm/year, changing flow directions in some sanitary and storm sewers since their original placement.

It is critical to understand that subsidence is infeasible to recover, once incurred, and the residence time of deep groundwater may be 1000 years. As a ‘ballpark’ indicator, groundwater replacement occurs only at 1/10 of 1% annually. Hence, groundwater depletion is difficult to avoid without significant efforts to advance deep groundwater replenishment. Consequently, to put these dimensions into context, subsidence now exceeds coastal, absolute sea level rise by a factor of 10 for many coastal cities [

36]. Nevertheless, the increase in absolute sea level is the aspect receiving the most media attention.

5. Forward Looking

Attempts to deal with the contradicting scenarios of water quality sustainability, as discussed in this paper along with specific examples, demonstrate the need to ensure a comprehensive understanding on how to deal with issues of water quality sustainability. It is paramount to recognize that issues of water security and safety exist worldwide, and are intensifying due to population growth, rapid urbanization, and climate change.

Attaining water sustainability in the 21st century must be one of the top priorities throughout the world. While the world has large amounts of water, much is not readily available and the vast majority of water (97% is in the oceans) and Antarctica and Greenland Ice Sheets contain 99 percent of the fresh water on earth. Hence, with large population growth, and much of the growth occurring in megacities, water sustainability issues arise from an array of issues including a) increasing water demands (e.g., for irrigation, hydropower, and urban areas); b) the deteriorating situation of available water due to the diminishing impacts of climate change, population growth resulting in in-creased water demands, and the challenges of availability of adequate quality of water, all combine to translate to increased challenges of sustainability.

Since issues of sustainability are intense, large, and growing, based on the preceding, the list below presents some general conclusions:

Local water shortages are multiplying in virtually all countries around the world;

Current water uses and abuse patterns involving the amount of water being withdrawn from groundwater are dangerously close to exhaustion. In many cases, the limit/tipping point has been reached; and,

Issues for water, food, energy, and environmental quality are extensively interconnected. The demands for water supply to cities and for irrigation purposes are already exceeding water availability in many locations. Meanwhile, continuing climate change further intensifies the severity of the water sustainability issues.

Sustainability includes the need to fulfill objectives of current generations without compromising the needs of future generations, while ensuring a balance between eco-nomic growth, environmental care, and social well-being. This article demonstrates some of the spatial and temporal issues, and some of the major concerns and indications of which, are rapidly evolving. Clearly, there are many existing challenges, and they will inevitably become more challenging in the future.

Many water management decisions and activities are currently predicated based on the assumption of a stationary climate, despite the reality of ongoing climate change. Attention to climate change will be required to become a major focus and proceed accordingly. The problem in a changing climate will not be easy.

There is still much to be done to attain water sustainability (and becoming more complicated all the time), where issues are going to intensify and ‘water use’ has more than tripled. Insufficient water is available to support the current population growth, considering the temporal and spatial heterogeneity. It is noted that due to water shortages, some governments are now trying to monetize the social value of water to compete with the distribution based on the least cost of water delivery, to allow a better assessment of the trade-offs but that continues to be enormously difficult.

People often do not realize and appreciate the importance of water “until the well runs dry”. However, running out of water is already happening in many locations around the world. As a result, water security will become one of the most critical issues facing the world in the coming decades. Since water is life, there is no post-water economy.

6. Conclusions

This paper connected drivers of water crisis in urban cities especially in developing countries. The history of water crises in India due to groundwater extraction and population growth is presented to demonstrate the competition of irrigation and urbanization in term of water demand. The connection between population growth, as well as diet change, and increasing irrigation demand is highlighted. Drivers such as sea water intrusion and water division conflict are also important to deliver a full picture of water crisis. Overall, this paper depicts a comprehensive picture of the ongoing water crisis. This paper provides insights for policy makers to fully understand the drivers and possible solutions to their water crisis, and also a thought-provoking tool for researchers to explore new strategies or solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J.; E.M. methodology, A.J., E.M.; investigation, A.J.; resources, A.J.,Y.W.; data curation, A.J.,E.M., Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J.; writing—review and editing, A.J.,E.M., Y.W.; visualization, A.J.; project administration, A.J.,E.M.; funding acquisition, A.J., E.M..

Funding

This research was funded by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery grant and NSERC Scholarship funds. The APC for publication was funded by MDPI.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this review paper.

Acknowledgments

The various findings described in the text represent a ‘lifetime of assembly’ in understanding and assembly of issues that influence sustainability. The paper shows the lines of pathways as to what issues and indicates what has been tried (with some successful results and some indications of failure).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 68% of the world population projected to live in urban areas by 2050, says UN. 2018. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html.

- McBean, E. Implications of Climate Change and Urbanization to Sustainability of Urban Water Supplies. in International e-Conference on “Water Source Sustainability”. 2023. IIT-Roorkee, India.

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Water Use and Stress. 2018. https://OurWorldInData.org.

- McBean, E.Sustainability – The Nexus of Water, Energy and Food for the 21st Century, Xi’an Jiatong University, Editor. 2022: China.

- World Development Sources, India - Water resources management sector review: groundwater regulation and management report (English). 1998, World Bank.

- Shah, T.Groundwater: a global assessment of scale and significance, in Water for food, water for life: a Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture. 2007, International Water Management Institute (IWMI): London, UK: Earthscan; Colombo, Sri Lanka. p. 395-423.

- Shah, T. Groundwater and human development: challenges and opportunities in livelihoods and environment. Water Science & Technology 2005, 51, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, E. and E. McBean, Effects of Water Marketing on Physical and Biological Resources, in Sharing Scarcity Gainers & Losers in Water Marketing, H.O. Carter, J. Henry J. Vaux, and A.F. Scheuring, Editors. 1994, University of Caliornia Agriculture Issues Center.

- Jiang, A.Z.; McBean, E.A. Sponge City: Using the “One Water” Concept to Improve Understanding of Flood Management Effectiveness. Water 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NITI Aayog, COMPOSITE WATER MANAGEMENT INDEX. 2019, Ministry of Jal Shakti and Ministry of Rural Development: India.

- Coppock, R.; Gray, B.E.; McBean, E. California Water Transfers: The System and the 1991 Drought Water Bank, in Sharing Scarcity Gainers & Losers in Water Marketing, H.O. Carter, J. Henry J. Vaux, and A.F. Scheuring, Editors. 1994, University of Caliornia Agriculture Issues Center.

- FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS. Review of World Water Resources by Country, in Water Reports 23. 2003: Rome.

- Chen, H.; et al. An enhanced shuttleworth-wallace model for simulation of evapotranspiration and its components. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2022, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO, AQUASTAT Core Database, FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS, Editor. 2020.

- McBean, E.A. Water Security, The Nexus Of Water, Food, Population Growth and Energy. The Global Environmental Engineers 2016, 3, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBean, E., Low-Tech Water Treatment Technology for Producing Safe Water, IIT-Roorkee, Editor. 2023: Bharat Singh Memorial Endowment Lecture.

- Zhang, C.; McBean, E.A. Adaptation Investigations to Respond to Climate Change Projections in Gansu Province, Northern China. Water Resources Management 2014, 28, 1531–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs, World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights. 2019, United Nations.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (via World Bank), Average precipitation in depth (mm per year), Our World in Data, Editor. 2023: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (via World Bank).

- Taraky, Y.M.; et al. The Role of Large Dams in a Transboundary Drought Management Co-Operation Framework—Case Study of the Kabul River Basin. Water 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taraky, Y.M.; et al. Flood Risk Management with Transboundary Conflict and Cooperation Dynamics in the Kabul River Basin. Water 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taraky, Y.M.; et al. Amu Darya Hydrologic Assessment – The Case of Agricultural Land Expansion, Cooperation and Unilateralism in the Basin. International Journal Water Resources Management and Irrigation Engineering Research 2023. Under Review. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.; Mojid, M. Groundwater Withdrawal Trend and Management Considerations in an Intensive Groundwater Irrigation Region in Bangladesh. Journal of Bangladesh Agricultural University 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumilova, O.; et al. Global Water Transfer Megaprojects: A Potential Solution for the Water-Food-Energy Nexus? Frontiers in Environmental Science 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBean, E.A. Climate Change: Impacts to Coastal Cities and the Need for Adaptations. in CWRA 2018. 2018. Victoria, BC, Canada.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Tropical Cyclone Introduction; 2023. Available from: https://www.noaa.gov/jetstream/tropical/tropical-cyclone-introduction.

- McBean, E.; Huang, J. Sustainability Risks of Coastal Cities from Climate Change. The Global Environmental Engineers 2017, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBean, E.; Huang, J. Water Security Implications in the 21st Century for Coastal Cities: The Imperative Need for Action. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 2020, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, H.M.; et al. Hurricane Katrina storm surge distribution and field observations on the Mississippi Barrier Islands. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2007, 74, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeri, H.; Motiee, H.; McBean, E. Forecasting impacts of climate change on changes of municipal wastewater production in wastewater reuse projects. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lange, M.; McBean, E. Modeling Investigation to Support Integrated Water Management in Southern Ontario: Considering Climate Change and Urbanization. Journal of Water Management Modeling 2017. [CrossRef]

- McBean, E. Removal of Emerging Contaminants: The Next Water Revolution. Journal of Environmental Informatics Letters 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of the Environment and Conservation and Parks. Source protection. 2021. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/page/source-protection.

- Motiee, H.; Salamat, A.; McBean, E. Drought As A Water Related Disaster - A Case Study of Lake Oroomiyeh. Lac Journal ( Journal) of the International Hydrological Program for Latin America and Carribean 2012, 4, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Monitoring Land Subsidence in Wuhan City (China) using the SBAS-InSAR Method with Radarsat-2 Imagery Data. Sensors 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaussard, E.; et al. Sinking cities in Indonesia: ALOS PALSAR detects rapid subsidence due to groundwater and gas extraction. Remote Sensing of Environment 2013, 128, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).