Submitted:

26 January 2024

Posted:

29 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background and Objectives

Diagnostic Criteria and Radiological Evidence:

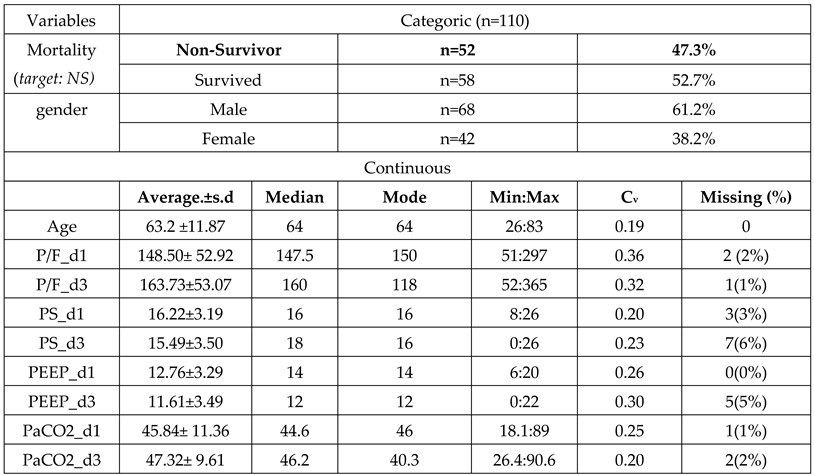

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Primary Outcome

2.4. Data Acquisition

2.5. Sample Split and Imputation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

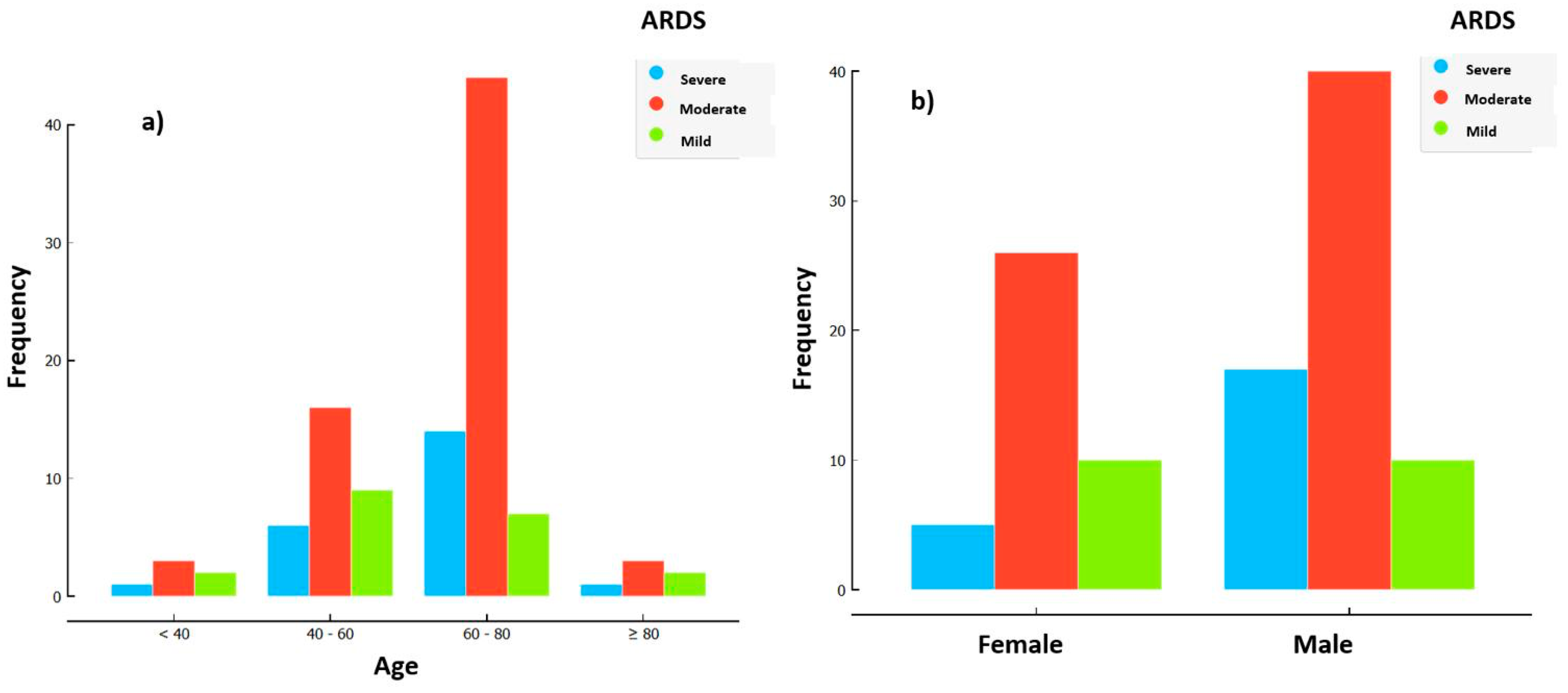

3. Results

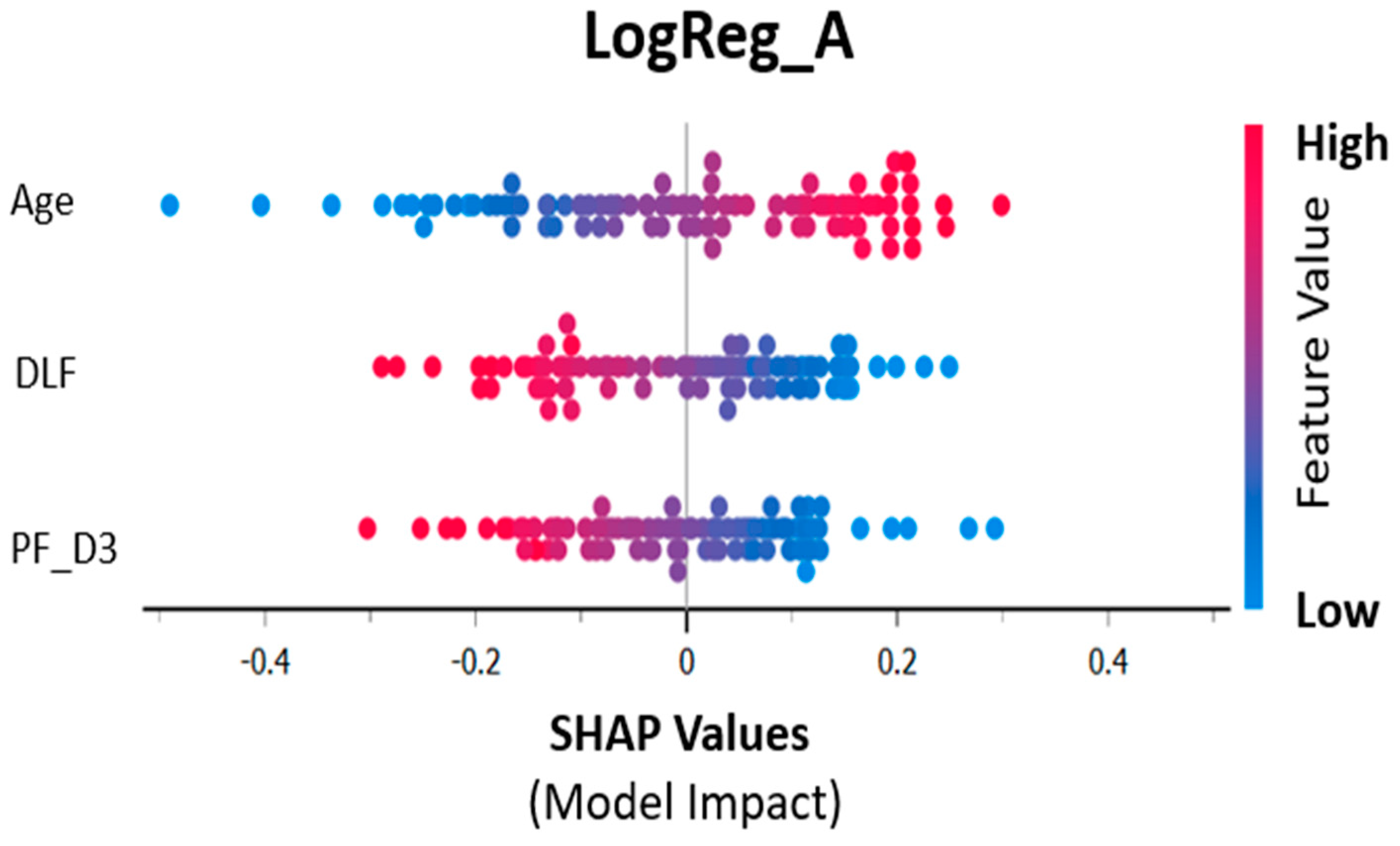

3.1. Logistic Regression Analysis:

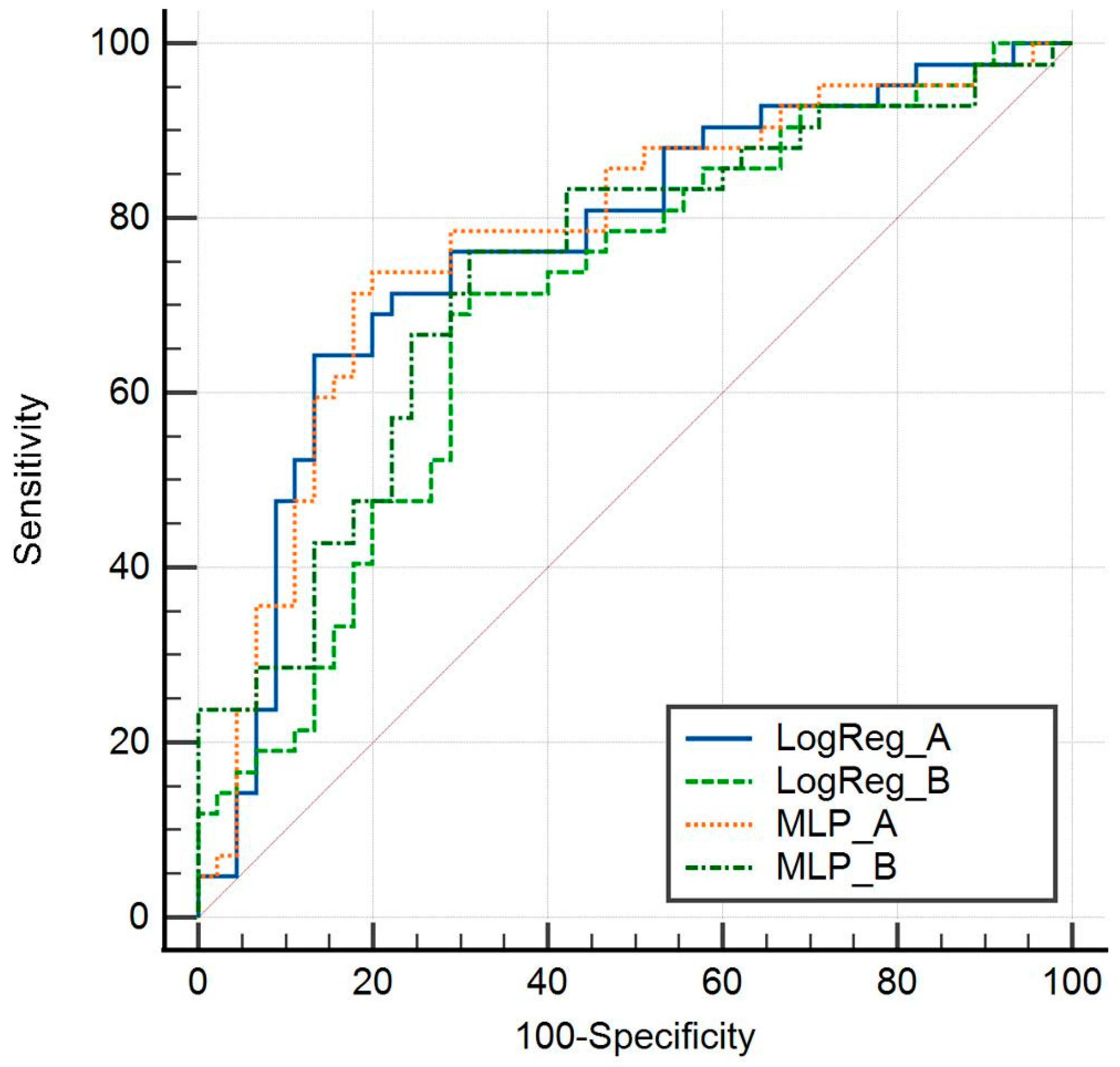

3.2. Model Performance

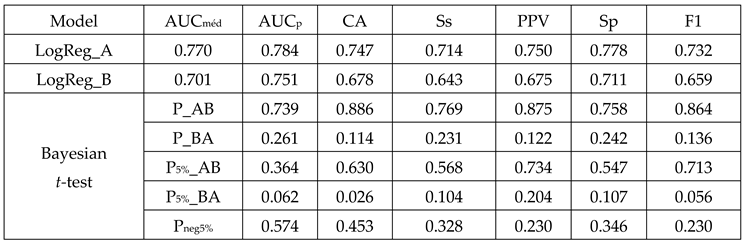

3.3. Comparative Analysis:

3.4. Cross-Validation Significance:

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions:

References

- The ARDS Definition Task Force*., ‘JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526-2533. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Matthay et al., ‘Acute respiratory distress syndrome’, Nat Rev Dis Primers, vol. 5, no. 1, 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Orraine, B. W. Are, and A. M. Atthay, ‘The New Eng land Jour nal of Medicine T HE A CUTE R ESPIRATORY D ISTRESS S YNDROME’, 2000.

- N. J. Meyer, L. Gattinoni, and C. S. Calfee, ‘Acute respiratory distress syndrome’, The Lancet, vol. 398, no. 10300. Elsevier B.V., pp. 622–637, Aug. 14, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Grasselli et al., ‘ESICM guidelines on acute respiratory distress syndrome: definition, phenotyping and respiratory support strategies’, Intensive Care Med, vol. 49, no. 7, pp. 727–759, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Matthay et al., ‘A New Global Definition of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome’, Am J Respir Crit Care Med, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Yndrome and N. Etwork, ‘The New England Journal of Medicine VENTILATION WITH LOWER TIDAL VOLUMES AS COMPARED WITH TRADITIONAL TIDAL VOLUMES FOR ACUTE LUNG INJURY AND THE ACUTE RESPIRATORY DISTRESS SYNDROME A BSTRACT Background Traditional approaches to mechanical’, 2000. [Online]. Available: www.ardsnet.org.

- L. D. J. Bos and L. B. Ware, ‘Acute respiratory distress syndrome: causes, pathophysiology, and phenotypes’, The Lancet, vol. 400, no. 10358. Elsevier B.V., pp. 1145–1156, Oct. 01, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Wildi, S. Livingstone, C. Palmieri, G. LiBassi, J. Suen, and J. Fraser, ‘The discovery of biological subphenotypes in ARDS: a novel approach to targeted medicine?’, Journal of Intensive Care, vol. 9, no. 1. BioMed Central Ltd, Dec. 01, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. V. Maddali et al., ‘Validation and utility of ARDS subphenotypes identified by machine-learning models using clinical data: an observational, multicohort, retrospective analysis’, Lancet Respir Med, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 367–377, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. W. Thille et al., ‘Comparison of the Berlin Definition for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome with Autopsy’, Am J Respir Crit Care Med, vol. 187, no. 7, pp. 761–767, Apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Reilly, C. Calfee, and J. Christie, ‘Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Phenotypes’, Semin Respir Crit Care Med, vol. 40, no. 01, pp. 019–030, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- ‘Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19’, New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 384, no. 8, pp. 693–704, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Lewis, M. W. Pritchard, C. M. Thomas, and A. F. Smith, ‘Pharmacological agents for adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome’, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, vol. 2019, no. 7, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Villar et al., ‘Dexamethasone treatment for the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial’, Lancet Respir Med, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 267–276, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Le et al., ‘Supervised machine learning for the early prediction of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)’, J Crit Care, vol. 60, pp. 96–102, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Bitker, D. Talmor, and J. C. Richard, ‘Imaging the acute respiratory distress syndrome: past, present and future’, Intensive Care Med, vol. 48, no. 8, pp. 995–1008, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Reamaroon, M. W. Sjoding, J. Gryak, B. D. Athey, K. Najarian, and H. Derksen, ‘Automated detection of acute respiratory distress syndrome from chest X-Rays using Directionality Measure and deep learning features’, Comput Biol Med, vol. 134, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. W. Sjoding et al., ‘Deep learning to detect acute respiratory distress syndrome on chest radiographs: a retrospective study with external validation’, Lancet Digit Health, vol. 3, no. 6, pp. e340–e348, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. F. L. Filippini et al., ‘Latent class analysis of imaging and clinical respiratory parameters from patients with COVID-19-related ARDS identifies recruitment subphenotypes’, Crit Care, vol. 26, no. 1, p. 363, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Giełczyk, A. Marciniak, M. Tarczewska, and Z. Lutowski, ‘Pre-processing methods in chest X-ray image classification’, PLoS One, vol. 17, no. 4 April, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Moreno et al., ‘Corticosteroid treatment in critically ill patients with severe influenza pneumonia: a propensity score matching study’, Intensive Care Med, vol. 44, no. 9, pp. 1470–1482, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Tsai et al., ‘Impact of corticosteroid treatment on clinical outcomes of influenza-associated ARDS: a nationwide multicenter study’, Ann Intensive Care, vol. 10, no. 1, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- ‘Comparison of Two Fluid-Management Strategies in Acute Lung Injury’, New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 354, no. 24, pp. 2564–2575, Jun. 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Warren et al., ‘Severity scoring of lung oedema on the chest radiograph is associated with clinical outcomes in ARDS’, Thorax, vol. 73, no. 9, pp. 840–846, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. R. Sedhai et al., ‘Validating Measures of Disease Severity in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome’, Ann Am Thorac Soc, vol. 18, no. 7, pp. 1211–1218, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Jabaudon et al., ‘Early Changes Over Time in the Radiographic Assessment of Lung Edema Score Are Associated With Survival in ARDS’, Chest, vol. 158, no. 6, pp. 2394–2403, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J.-M. Constantin et al., ‘Personalised mechanical ventilation tailored to lung morphology versus low positive end-expiratory pressure for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in France (the LIVE study): a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial’, Lancet Respir Med, vol. 7, no. 10, pp. 870–880, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. M. A. Valk et al., ‘The Prognostic Capacity of the Radiographic Assessment for Lung Edema Score in Patients With COVID-19 Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome—An International Multicenter Observational Study’, Front Med (Lausanne), vol. 8, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Herrmann et al., ‘COVID-19 Induced Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome—A Multicenter Observational Study’, Front Med (Lausanne), vol. 7, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Mongodi, E. Santangelo, B. Bouhemad, R. Vaschetto, and F. Mojoli, ‘Personalised mechanical ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome: the right idea with the wrong tools?’, Lancet Respir Med, vol. 7, no. 12, p. e38, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Pierrakos et al., ‘Lung Ultrasound Assessment of Focal and Non-focal Lung Morphology in Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome’, Front Physiol, vol. 12, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

|

|

| Metrics | LogReg_Train95%CI | LogReg_CV95%CI | LogReg_Test95%CI | ΔCV_Train | ΔTest Train |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUCmed | 0.820 [0.723-0.894] |

0.770 [0.667-0.853] |

0.862 [0.654-0.969] |

-0.092 | 0.042 |

| AUCp | 0.820 | 0.784 | 0.862 | -0.036 | 0.042 |

| CA | 0.782 [0.681-0.863] |

0.747 [0.643-0.834] |

0.783 [0.563-0.926] |

-0.035 | -0.0 |

| F1 | 0.776 [0.672-0.859] |

0.732 [0.623-0.824] |

0.783 [0.563-0.926] |

-0.044 | 0.007 |

| PPV | 0.767 [0.623-0889] |

0.750 [0.588-0.873] |

0.692 [0.385-0.909] |

-0.026 | 0.084 |

| NPV | 0.795 [0.647- 0.902] |

0.744 [0.596- 0.861] |

0.900 [0.555-0.997] |

-0.051 | 0.105 |

| Ss | 0.787 [0.633-0.898] |

0.714 [0.554-0.843] |

0.900 [0.555-0.997] |

-0.073 | 0.113 |

| Sp | 0.778 [0.629-0.888] |

0.778 [0.629-0.888] |

0.692 [0.385-0.909] |

0.000 | -0.086 |

| Metric | LogReg_A | LogReg_B | ΔA-B |

|---|---|---|---|

|

AUCmed |

0.770 95%CI [0.667-0.853] |

0.701 95%CI [0.593-0.794] |

0.069 |

|

CA |

0.747 95%CI [0.643- 0.834] |

0.678 95%CI [0.569-0.774] |

0.069 |

|

PPV |

0.750 95%CI [0.588- 0.873] |

0.675 95%CI [0.509-0.814] |

0.075 |

|

Sensitivity |

0.714 95%CI [0.554- 0.843] |

0.643 95%CI [0.480-0.784] |

0.071 |

|

NPV |

0.744 95%CI [0.596- 0.861] |

0.714 95%CI [0.554- 0.843] |

0.081 |

|

Specificity |

0.778 95%CI [0.629- 0.888] |

0.711 95%CI [0.560-0.834] |

0.067 |

|

F1 |

0.732 95%CI [0.623-0.824] |

0.659 95%CI [0.546-0.760] |

0.073 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).