1. Introduction

The incidence and the prevalence of malignant melanoma (MM) are constantly raising, due to numerous screening campaigns that had let to a more timely diagnosis and earlier surgical treatment [

1]. Consequently, the prognosis of melanoma has benefited, leading to a reduction in recurrence and mortality rates [

2]. This improvement in prognosis is due on the one hand to surgical therapies of primary tumors carried out for melanomas in the early stages of the disease but also to the development and use of increasingly effective oncological protocols [

3].

As suggested by scientific guidelines, following the surgical excision of the primary tumor and the consequent histological diagnosis of MM, a wide excision of the surgical scar must follow, ensuring the removal of adequate margins of neighboring healthy tissue in relation to the initial Breslow thickness [

4]. Like any other surgical procedure, wide excision is burdened by possible surgical complications, such as infections, dehiscence, hematomas, seromas, etc.; moreover, in particular anatomical areas - such as the head, neck or hands - it can lead to significant aesthetic and functional deficits [

5]. The definition of the margins of wide excision indicated by the guidelines has remained unchanged over the years, although the reported indications derived from fairly dated studies [

6]. The populations involved in these studies suffered from melanomas that tend to be thicker or in advanced stages of the disease and the definition of margins has been established with analysis on recurrences and/or mortality in a different era with different melanoma prognosis [7-8].

The authors’ hypothesis is that these indications may no longer be current; especially in those patients affected by in situ or thin melanoma (Breslow thickness less than 1 mm), exposing patients to a possible overtreatment and consequent surgical complications.

The aim of the present study is to retrospectively evaluate the usefulness of wide excision in the local and general control of the disease, identifying the cohort of subjects for whom the wide excision of primary tumor have improved prognosis of MM.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

A retrospective observational study was conducted using data collected from hospital and outpatient medical records, relating to patients who had undergone surgery for melanoma at the Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Unit of the Bari General Hospital. All patients who had a histological diagnosis of melanoma and who subsequently underwent surgical wide excision from 01/01/2013 to 31/12/2019, and with at least three years of regular follow-up visits, were included in this study. Patients who declined the consent for the use of data for scientific aims were removed from the analysis. The main clinical symptoms, anamnestic conditions, histological exams and follow-up diagnostic exams were recorded: date of excision of melanoma, date of diagnosis, length of the excised lozenge, width of lozenge, thickness of lozenge, type of melanoma, site of melanoma, side of melanoma, Breslow thickness, Clark level, presence of ulceration, number of mitosis, presence of peritumoral or intratumoral lymphocytic infiltrate, percent of regression, TNM stage, microscopic distance from the margins, date of wide excision, length of wide excision, width of wide excision, thickness of wide excision, date of Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), site of SLNB, number of tumor-positive SLNB, date of Lymphadenectomy, site of Lymphadenectomy, number of lymph nodes removed, number of lymph nodes with metastasis. The results of the clinical visits and instrumental investigations to which each patient was subjected were also collected, in subsequent checks carried out periodically. The instrumental investigations evaluated were: chest x-ray, ultrasound of the surgical wound and lymph node basis, abdominal and pelvic ultrasound, head computed tomography (CT), chest CT, abdominal and pelvic CT, head magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), chest MRI, abdominal and pelvic MRI and positron emission tomography (PET).

2.2. Endpoints

The primary endpoint was to evaluate which patient demographic characteristics and melanoma histological data were associated with the finding of metastases at the wide excision.

The secondary endpoint was to assess the progression free survival (PFS) in subjects with or without metastases after the wide excision.

PFS was defined as the time interval between the date of histological diagnosis of melanoma and the occurrence of one of the following events, whichever occurs first:

2.3. Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were shown as means and standard deviation (SD) if normally distributed, and as median and interquartile range (IQR) if assumption of normality was not acceptable. Shapiro–Wilk’s statistics was used to test normality. Differences in continuous variables between groups were compared by using Student’s t-test for normally distributed parameters, or the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test otherwise. Categorical data were expressed as frequency and percentage, and the Chi-square test or Fischer’s exact test, as appropriate, was used to compare the groups. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Progression free survival (PFS) was defined as the time interval between the date of histological diagnosis of melanoma and the occurrence of the composite endpoint. Univariable and multivariable Cox regression models were performed to evaluate associations between 3-year PFS and other parameters. The proportional hazards assumptions for the Cox model were tested and the results were expressed as Hazard Ratio (HR) and their 95% confidence interval. HRs were adjusted for the covariates: sex, age at melanoma diagnosis, type of melanoma, presence of metastases after wide excision, lozenge length, lozenge width, lozenge thickness, Breslow thickness (categorized in four classes: <1mm, 1-2mm, 2.1-4mm and over then 4mm), presence of intratumoral infiltrate and presence of peritumoral infiltrate. The survival was described by the Kaplan-Meier curves.

To explore the risk to found metastases at the margin of the wide excision, the univariate and multivariable logistic models were employed; the dependent variable was the presence of metastases at the margin. The variables included in the model were: sex, age at melanoma diagnosis, type of melanoma, time from diagnosis to wide excision, lozenge length, lozenge width, lozenge thickness, Breslow thickness, presence of intratumoral infiltrate, presence of peritumotal infiltrate and presence of ulcerations. The results of the logistic model were shown as odds ratios and their 95% Confidence Interval (CI) for each variable.

The optimal cut point for the melanoma Breslow thickness to predict the presence or absence of metastasis at the site of wide excision was found with the package

cutpointr performed by Thiele Christian et al [

9]. Optimal cut points are estimated by choose Youden index as a metric and select that cut point as optimal for empirically maximizes the Youden index in the sample [

10]. The out of sample performance was estimating to evaluate the optimal cut point, with the bootstrap method [

11]. For calculation of confidence intervals, 1500 repeats of the bootstrap were chosen [

12]. The measures of accuracy were based on the area under the ROC curve (AUC) and on the follow indicators: sensitivity (true positive divided all events), specificity (true negative divided all non-events), accuracy (the sum of true positive and true negative divided the whole sample) and Cohen's kappa coefficient.

2.4. Software

Data management, descriptive statistics and modelling were performed using SAS/STAT version 9.4 for PC (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). To choose the cut-off value the

cutpointr pachage was run in R-Studio version 1.4.1106 [RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA. 2021. Available online:

http://www.rstudio.com/] [Thiele C, Hirschfeld G (2021). “cutpointr: Improved Estimation and Validation of Optimal Cutpoints in R.” Journal of Statistical Software, 98(11), 1–27. doi:10.18637/jss.v098.i11.].

3. Results

The number of melanoma patients registered during the analysis period was 624, but only 460 were included in this study according to the inclusion criteria. The mean age of the study sample was 55 years [IQR 45-66], however the males were older [59, IQR 48-69.5] than the females [51, IQR 42.5-63.5]. Overall, 72 (14.2%) patients had a disease progression for melanoma; these patients formed the group A. The main characteristics among the outpatients with (Group A) or without (Group B) composite endpoint are described in

Table 1.

Male subjects were more frequent in Group A (68.06% vs. 50.96%, p=0.0094). Patients of Group A had principally a nodular melanoma with a Breslow thickness over the 2.1 mm (62.91% vs 30.87%). No significant differences between the sites of melanoma were observed between the two groups. Furthermore, no statistically significant difference was observed between the groups for the presence of metastases at the wide excision (10.45% vs. 4.29%, p=0.0653).

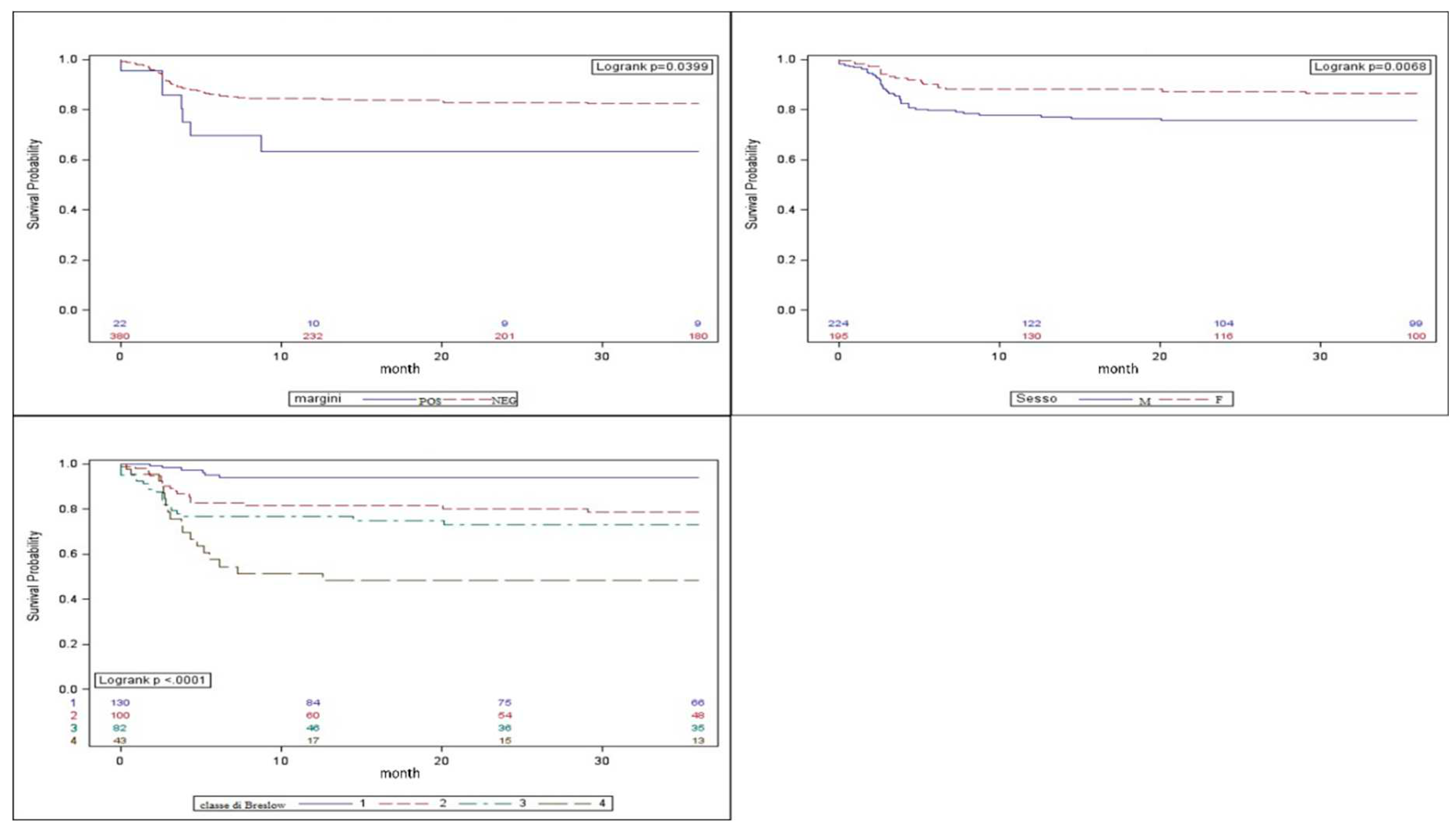

Survival curves for sex, type of melanoma and the presence of metastases at the wide excision were plotted with the Kaplan-Meier method (

Figure 1). Patients with a metastasis have showed a lower survival respect those without metastasis: the mean (± standard error) survival was 6.99 month (0.67) and 24.86 (0.53), respectively in those with and without (p=0.039). Male patients survived less longer than female: mean (standard error) was 16.22 (0.52) and 25.97 ( 0.66) respectively (p=0.006).

A univariate and multivariate Cox regression model was performed to assess factors associated with the composite progression-free survival (PFS) endpoint. All Hazard Ratios and their confidential ranges are reported in

Table 2.

In multivariate analysis, after adjustment for age at diagnosis, sex and the time between the diagnosis of melanoma and the wide excision, the PFS resulted associated with the width of the lozenge (HR 1.46, IC95% 1.03-2.06) and the thickness of Breslow under 1 mm (<1mm vs 1.1-2mm: HR 0.23, IC95% 0.09-0.64; <1mm vs. 2.1-4mm: HR 0.17, IC95% 0.06-0.47; <1mm vs. >4mm: HR 0.11, IC95% 0.04-0.32). Further, even if in the univariate model (HR 2.23, IC95% 1.02-4.89) it was found an association between survival and the presence of metastases at wide excision in the multivariable model it was not confirmed (HR 1.62, IC95% 0.63-4.17).

A univariate and multivariable logistic model were applied to estimate the probability to find a metastasis after wide local excision (WLE) in relation to demographic data of patients and histologic information of the melanoma. In the univariate model, a greater risk was found for each one year increase in age (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02-1.1), lozenge width (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.02-2.2), and Breslow thickness (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.15- 1.61). On the other hand, a reduction in risk was generally found for the histological diagnosis of superficial spreading melanoma compared to the other (superficial spreading vs. ephythelioid: OR 0.07, 95% CI 0.01-0.36; 0.28-0.66; superficial versus lentigo maligna: OR 0.1, 95% CI 0.02-0.65). Furthermore, an increased risk has been observed generally for melanomas located in the head-neck area compared to the other (head-neck vs limb: OR 4.2, IC95% 1.41-12.47; head-neck vs torso: OR 8.17, IC95% 2.57-25.94). In the multivariate model adjusted for patient sex and age, only Breslow thickness was associated with the increase of the risk to found metastases in the WLE area (OR 1.41, IC95% 1.06-1.88). All Odds Ratio are reported in the

Table 3.

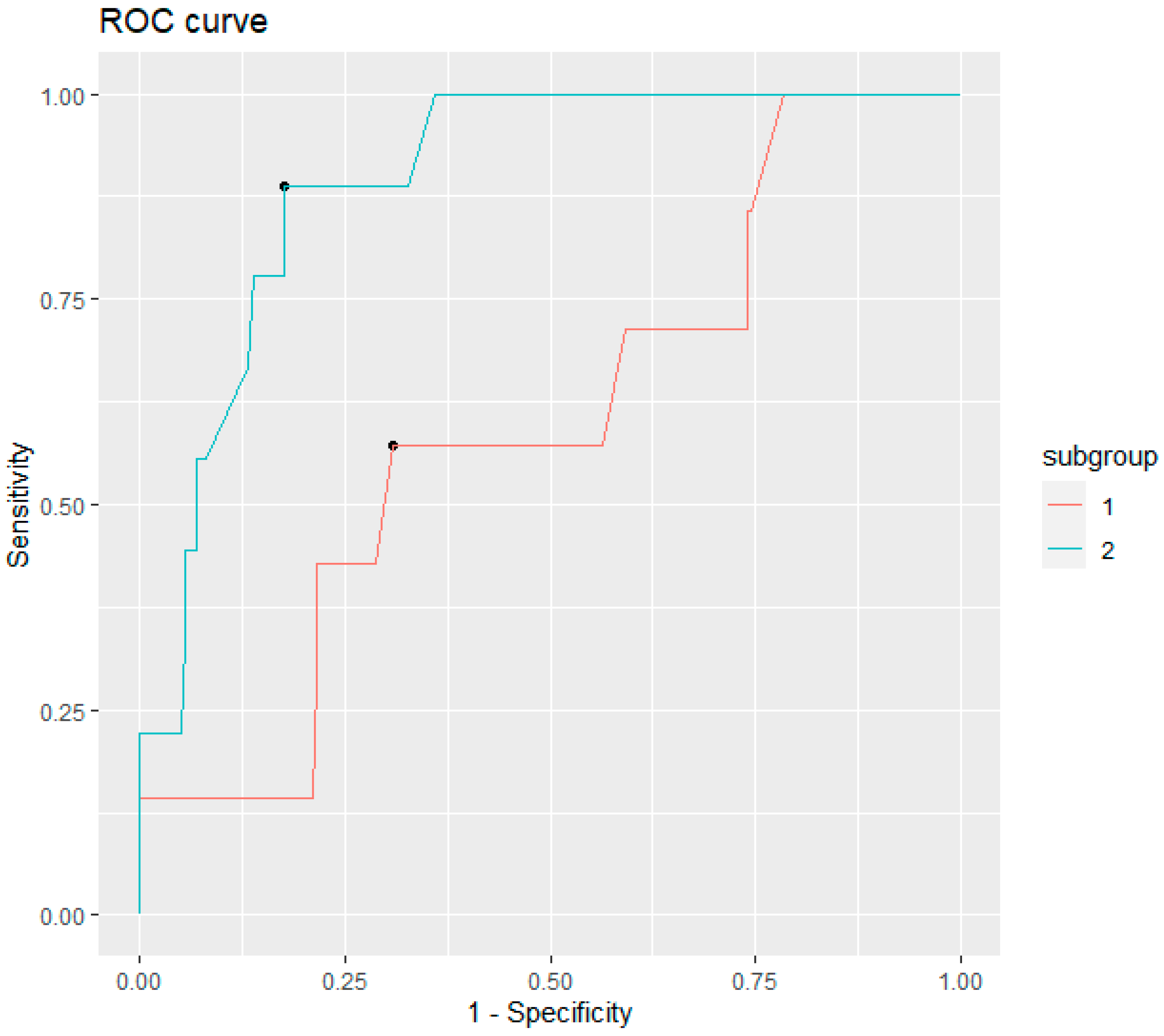

The optimum cut-off value to differentiate patients with respect those without a tumor-positive wide excision, was a Breslow thickness of 2.31mm. This was chosen to the higher value of Youden index, that resulted 0.5 and is associated with a sensitivity 0.75 and a specificity 0.75 (

Table 4).

A 95% bootstrap confidence interval for the optimum cut-off level was 2.31-2.4 mm. The fitting parameters of the model are reported in

Table 5.

A stratified analysis by sex was conducted to verify the cut-off level in males and females. The optimum threshold of Breslow thickness to discriminate metastasis was 2.31mm [IQR 2.31-2.90] in women, and 2.4mm [IQR 0.87-3.2] in men.

Figure 2 shows the ROC curve.

The model for women has showed an higher AUC respect to that for men, respectively 0.9 vs 0.6, and an higher Youden index, that resulted 0.71 in women and 0.26 in men. The fitting parameters of these models are reported in

Table 6.

4. Discussion

Over the last decade, melanoma screening campaigns have led to greater awareness among the population of the problems of cutaneous melanoma, significantly anticipating the diagnosis and leading to the identification and diagnosis of melanomas in earlier stages of the disease [

1]. At the same time, the current guidelines have been significantly modified in relation to oncological treatment, leading to a notable improvement in prognosis [

2]. In relation to this substantial change in the diagnosis and management of MM, surgical therapy has also undergone changes, especially with regard to the treatment of lymph node metastases [

13]. In fact, current guidelines are recommending an increasingly selective use of surgery for the treatment of tumor-positive sentinel lymph nodes, reserving a highly destructive surgical treatment - such as lymphadenectomy - only for cases of lymphatic macrometastases of melanoma [

14]. Therefore, nodal clinical-instrumental observation is currently the prevailing deportment in the management of MM lymphatic involvement. This approach have led to a significant reduction in complications related to surgery without worsening the prognosis of patients [

15].

This change of perspective did not happen in the surgical management of MM primary lesion. In fact, current guidelines continue to suggest to respect the same excision margins at wide excision already defined in previous decades. Specifically, it is recommend for all MMs, regardless of the initial histological characteristics, a wide excision that respects the following surgical margins in relationship with the primary lesion Breslow’ thickness:

In situ melanomas: 0.5 cm of surgical margins of healthy tissue;

Breslow’ thickness <=1 mm: 1 cm of surgical margins of healthy tissue;

Breslow’ thickness 1.01-2.00 mm: 1-2 cm of surgical margins of healthy tissue;

Breslow’ thickness >2 mm: 2 cm of surgical margins of healthy tissue [

16].

It is important to underline that such margins cannot always be ensured; expecially for melanomas arising in cutaneous areas with aesthetic or functional relevance [

17]. Moreover, in wide primary lesion at high clinical-dermatoscopic suspicion for invasive melanoma in anatomical region in which a reconstruction with a skin graft or a flap is required, wide excision could affect reliability of lymphatic mapping, making the utility of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) after skin reconstruction controversial [

18].

Furthermore, the COVID era has forced surgeons to a dramatic reduction in their practices due to a rapidly decreasing hospital admissions for elective surgery; this has led to the need to act a further selection of melanoma patients elegible for surgery.

According to the above considerations regarding the lack of updating of the guidelines about wide excision’s margins and the limitations and problems related to their application, we have retrospectively reviewed the efficacy of wide excision for local and distant control of pathology in MM.

First, our study has shown that the cases in which a wide excision has produced the removal of residual tumor material are very limited. In fact, in the 460 subjects who satisfied the histological, clinical and follow up criteria of completeness, the presence of residual MM tissue after the wide excision was found in only 22 patients (4.78%). Although the frequency of progression for melanoma is higher in patients with tumor-positive wide excision, local or distant MM metastasis have been reported also in patients with a negative wide excision.

Moreover, despite the statistical significant impact on disease progression in univariate analysis, presence of residual melanoma at wide excision lost its significant relevance as independent predictive variable on MM prognosis in cox multivariate analysis. In fact, in the multivariate evaluation of clinical and pathological variables favoring disease progression, only Breslow thickness and width of the lozenge have demonstrate their predictive power. The relationship between the width of the lozenge and the worsening of the prognosis can be explained by the greater depth of MM primary lesion or by the lack of radicality due to anatomical reasons. Therefore, Breslow’ thickness was confirmed to be the only independent predictive factor in progression of melanoma.

Our analysis has also reported the relationship between Breslow’ thickness and presence of residual MM at wide excision. Specifically, roc curves analysis has identified the value of 2.31 mm as the optimum cut-off value of Breslow’ thickness to differentiate patients with respect those without a tumor-positive wide excision, showing a sensitivity 0.75 and a specificity 0.75 (AUC=0.76, Youden index=0.5).

The Breslow’ thickness value of 2.31 mm was confirmed as the optimum cut-off in women, demonstrating a high accuracy (AUC=0.9, Youden index=0.71) in prediction of tumor-positive wide excision; while in men the better cut-off was 2.4 mm, but with a lower accuracy (AUC=0.6, Youden index=0.26).

Therefore, our data suggest the need to more carefully evaluate the routinary preventive use of wide excision in melanomas less than 2.3 mm thick, according to the high rate of negativity after removal and the absence of a significant impact on the prognosis even in case of tumor-positive wide excision. A follow-up scheme with closer clinical, dermatoscopic, and/or ultrasound evaluation could be the solution to avoid surgical overtreatment.

5. Conclusions

Screening campaigns and greater attention to early diagnosis have led to the identification of thinner melanomas at diagnoses as compared to the past. This change in diagnostic timeliness did not correspond to a modification in guidelines on indications and margins of wide excision.

Our data showed a not significant impact of detection of residual MM at wide excision on prognosis of melanoma patients and the low frequency tumor-positive wide excision, furthermore in thin melanomas, suggesting a more selective recourse to wide excision in this cohort of patients.

The limits of our study are related to the retrospective and monocentric nature but – even if prospective multicentric analyses are needed - the large number of involved subjects and the long observation period ensure a sufficient reliability of the results.

Author Contributions

Conceptulization: Giuseppe Giudice, Eleonora Nacchiero; Formal Analysis: Massimo Giotta, Maria Elvira Metta, Paolo Trerotoli; Investigation: Fabio Robusto, Valentina Ronghi, Rossella Elia; Methodology: Eleonora Nacchiero, Fabio Robusto, Massimo Giotta; Supervision: Giuseppe Giudice, Paolo Trerotoli, Rossella Elia; Writing Original Draft: Eleonora Nacchiero, Fabio Robusto, Massimo Giotta, Maria Elvira Metta; Writing - review & editing: Giuseppe Giudice, Paolo Trerotoli.

Funding

No direct funding were received for study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Our research involves healthcare data with clinical and demographical information. There are legal restrictions on the data, which are owned by the Policlinico di Bari and cannot be transferred in their actual format to other entities. An anonymized dataset will be made available upon request for qualified researchers. In this case, the reference person for the is Prof. Giuseppe Giudice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- Bolick NL, Geller AC. Epidemiology of Melanoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2021 Feb;35(1):57-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahlon N, Doddi S, Yousif R, Najib S, Sheikh T, Abuhelwa Z, Burmeister C, Hamouda DM. Melanoma Treatments and Mortality Rate Trends in the US, 1975 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022 Dec 1;5(12):e2245269. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbe C, Amaral T, Peris K, Hauschild A, Arenberger P, Basset-Seguin N, Bastholt L, Bataille V, Del Marmol V, Dréno B, Fargnoli MC, Forsea AM, Grob JJ, Hoeller C, Kaufmann R, Kelleners-Smeets N, Lallas A, Lebbé C, Lytvynenko B, Malvehy J, Moreno-Ramirez D, Nathan P, Pellacani G, Saiag P, Stratigos AJ, Van Akkooi ACJ, Vieira R, Zalaudek I, Lorigan P; European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for melanoma. Part 2: Treatment - Update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Jul;170:256-284. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swetter SM, Thompson JA, Albertini MR, Barker CA, Baumgartner J, Boland G, Chmielowski B, DiMaio D, Durham A, Fields RC, Fleming MD, Galan A, Gastman B, Grossmann K, Guild S, Holder A, Johnson D, Joseph RW, Karakousis G, Kendra K, Lange JR, Lanning R, Margolin K, Olszanski AJ, Ott PA, Ross MI, Salama AK, Sharma R, Skitzki J, Sosman J, Wuthrick E, McMillian NR, Engh AM. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Melanoma: Cutaneous, Version 2.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021 Apr 1;19(4):364-376. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giudice G, Leuzzi S, Robusto F, Ronghi V, Nacchiero E, Giardinelli G, Di Gioia G, Ragusa L, Pascone M. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in head and neck melanoma*. G Chir. 2014 May-Jun;35(5-6):149-55. [PubMed]

- Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Adamus J, et al. Thin stage I primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Comparison of excision with margins of 1 or 3 melanoma. N Engl J Med 1988;318:1159-1162.

- Urist MM, Balch CM, Soong S, et al. The influence of surgical margins and prognostic factors predicting the risk of local recurrence in 3445 patients with primary cutaneous melanoma. Cancer 1985;55:1398-1402.

- Welvaart K, Hermans J, Zwavelig A, et al. Prognoses and surgical treatment of patients with stage I melanomas of the skin: a restrospective analysis of 211 patients. J surg oncol 1986;31:79-86.

- Thiele C, Hirschfeld G (2021). “cutpointr: Improved Estimation and Validation of Optimal Cutpoints in R”. Journal of Statistical Software, 98(11), 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Fluss R, Faraggi D, Reiser B (2005). “Estimation of the Youden Index and Its Associated Cutoff Point.” Biometrical Journal, 47(4), 458–472. [CrossRef]

- Altman DG, Royston P (2000). “What Do We Mean by Validating a Prognostic model?”Statistics in Medicine, 19(4), 453–473.

- Carpenter J, Bithell J (2000). “Bootstrap Confidence Intervals: When, Which, What? A Practical Guide for Medical Statisticians.” Statistics in Medicine, 19(9), 1141–1164.

- Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Final trial report of sentinel-node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:599–609.

- Pathak S, Zito PM. Clinical Guidelines for the Staging, Diagnosis, and Management of Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma. 2023 Jun 26. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan. [PubMed]

- Giuliano AE, Ballman KV, McCall L, et al. Effect of Axillary Dissection vs No Axillary Dissection on 10-Year Overall Survival Among Women With Invasive Breast Cancer and Sentinel Node Metastasis: The ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;318:918–926.

- Ethun CG, Delman KA. The importance of surgical margins in melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2016 Mar;113(3):339-45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giudice G, Leuzzi S, Robusto F, Ronghi V, Nacchiero E, Giardinelli G, Di Gioia G, Ragusa L, Pascone M. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in head and neck melanoma*. G Chir. 2014 May-Jun;35(5-6):149-55. [PubMed]

- Giudice G, Robusto F, Vestita M, Annoscia P, Elia R, Nacchiero E. Single-stage excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy in cutaneous melanoma in selected patients: a retrospective case-control study. Melanoma Res. 2017 Dec;27(6):573-579. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).