Submitted:

22 January 2024

Posted:

23 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Data Source

2.2.2. Data Preprocessing

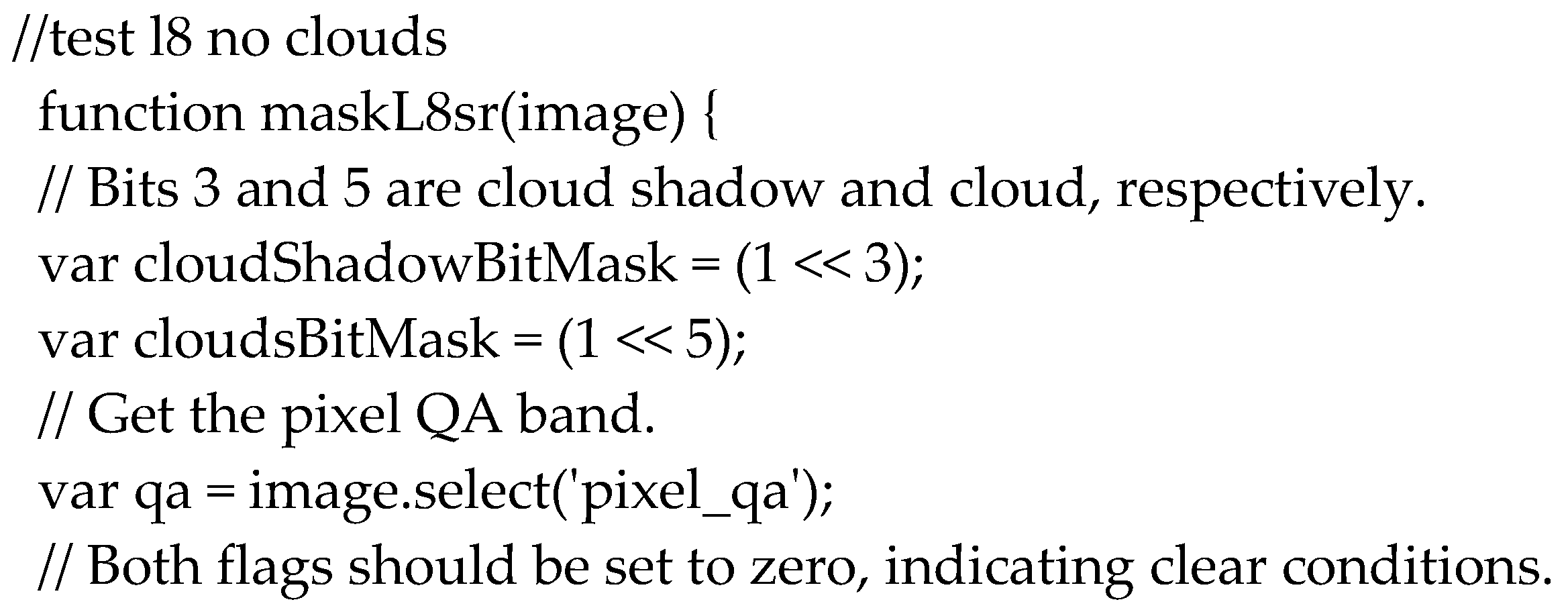

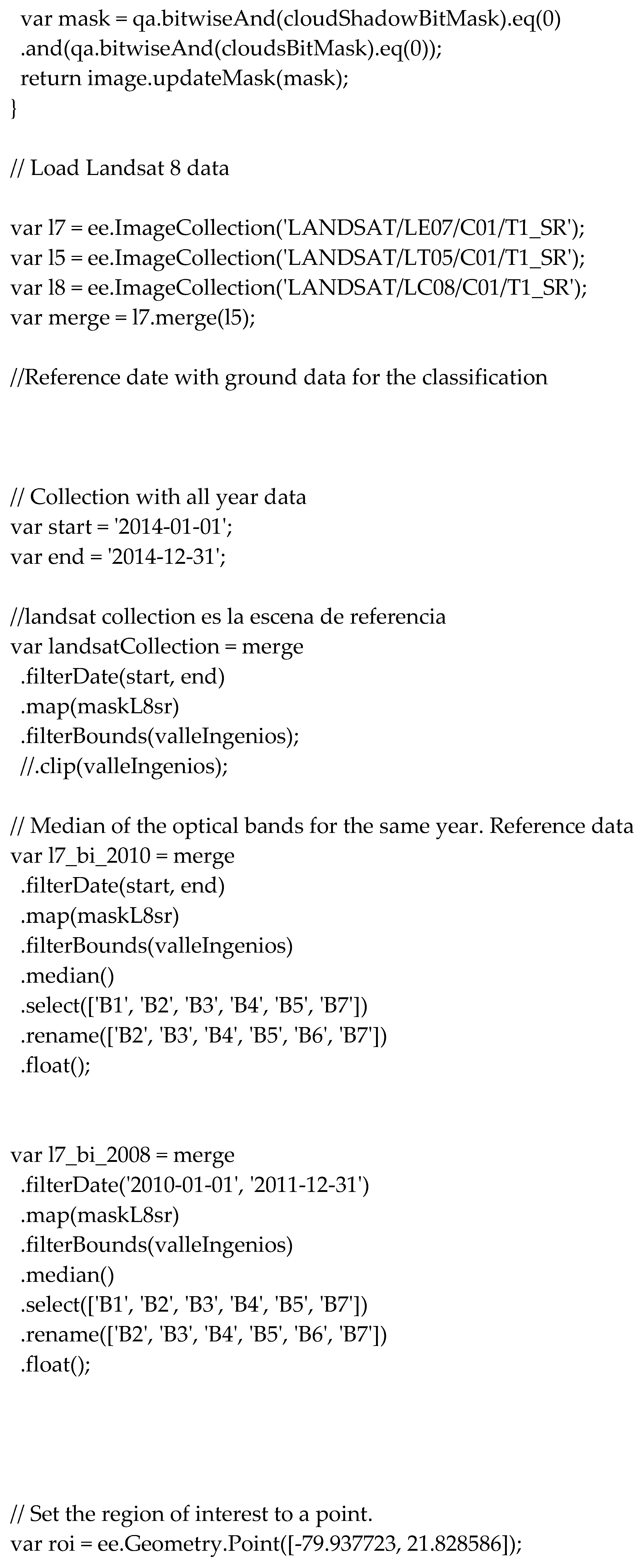

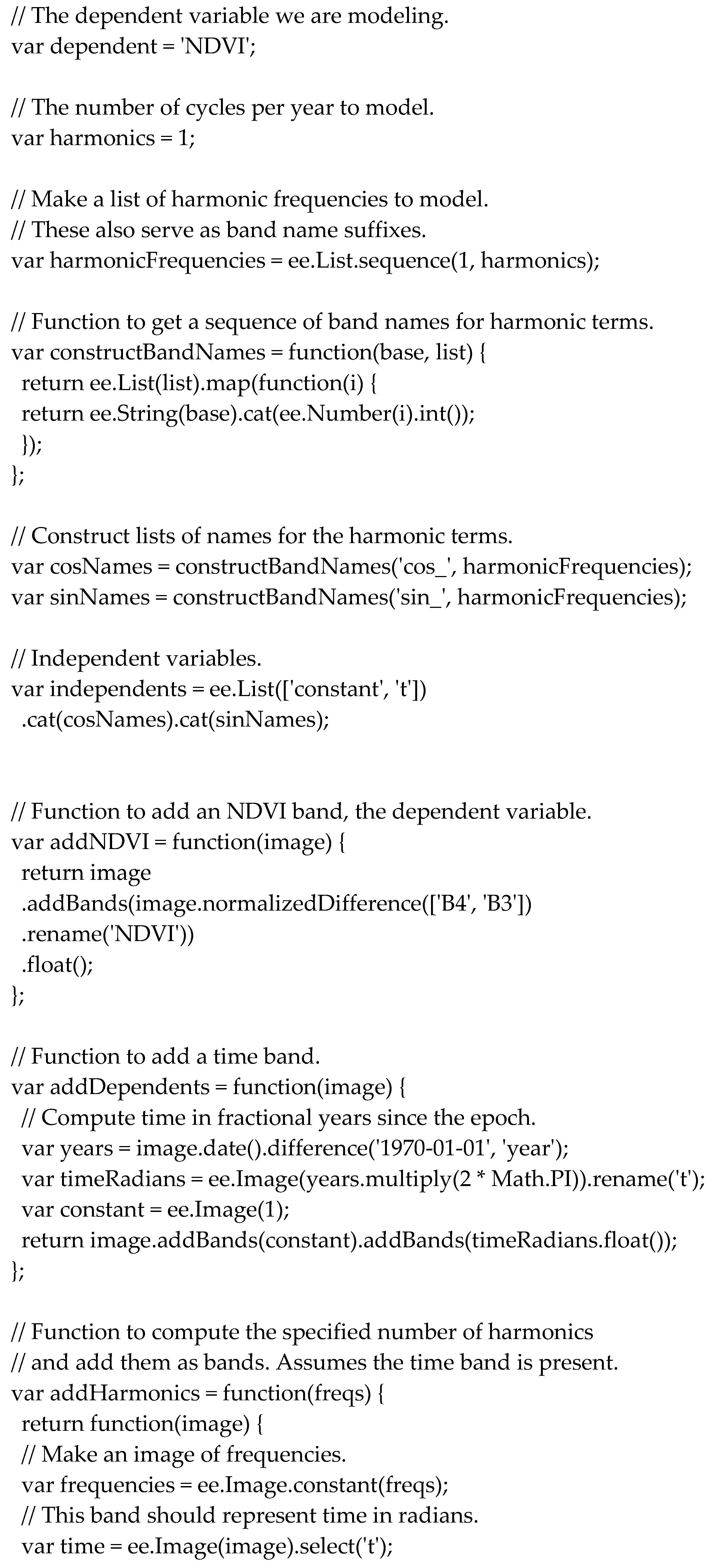

2.2.3. Harmonic Curve Development

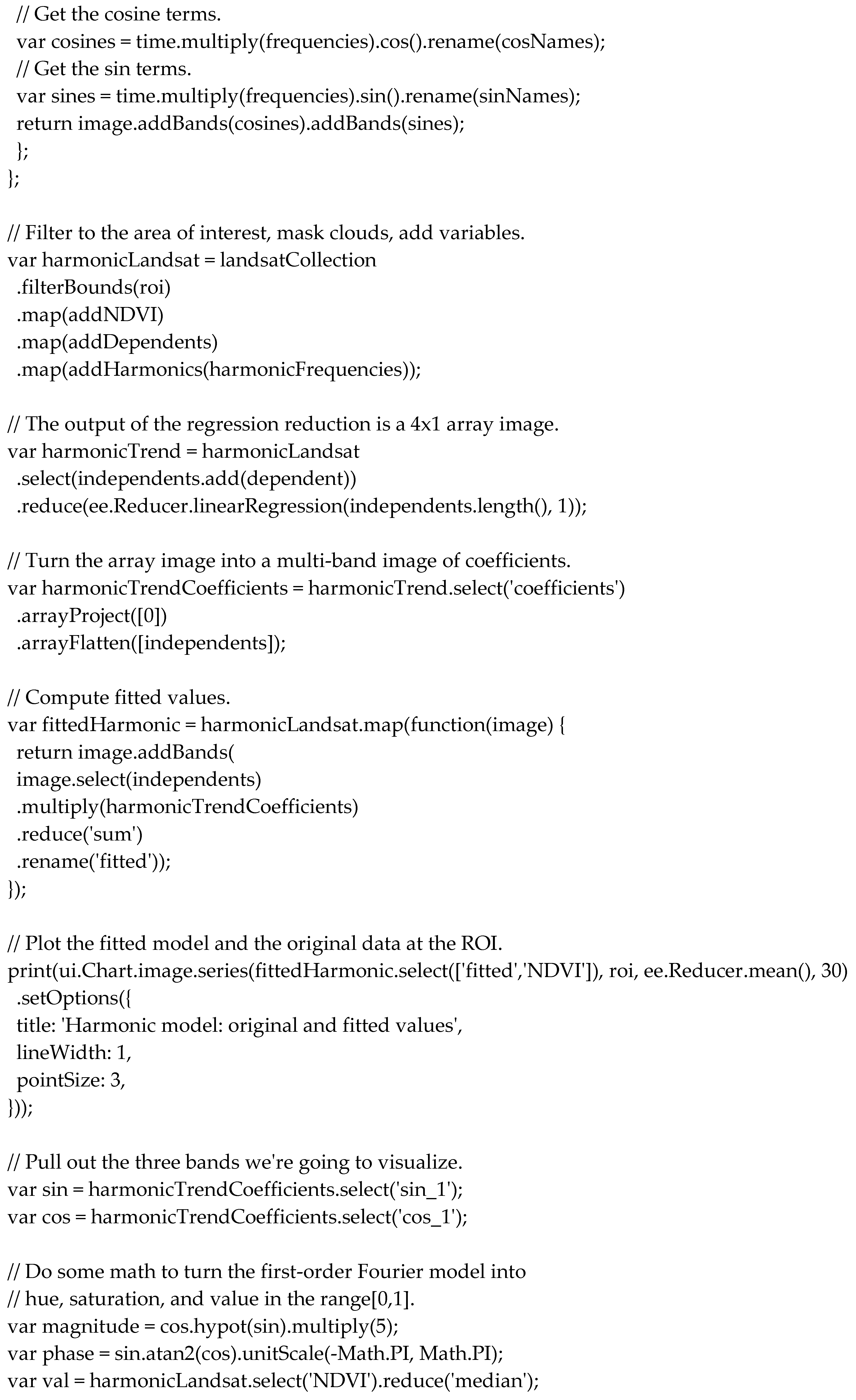

2.2.4. Field Data

2.2.5. Classification Algorithm

2.2.6. Workflow Overview

2.2.7. Temporal Considerations

2.2.8. Code Accessibility

3. Results

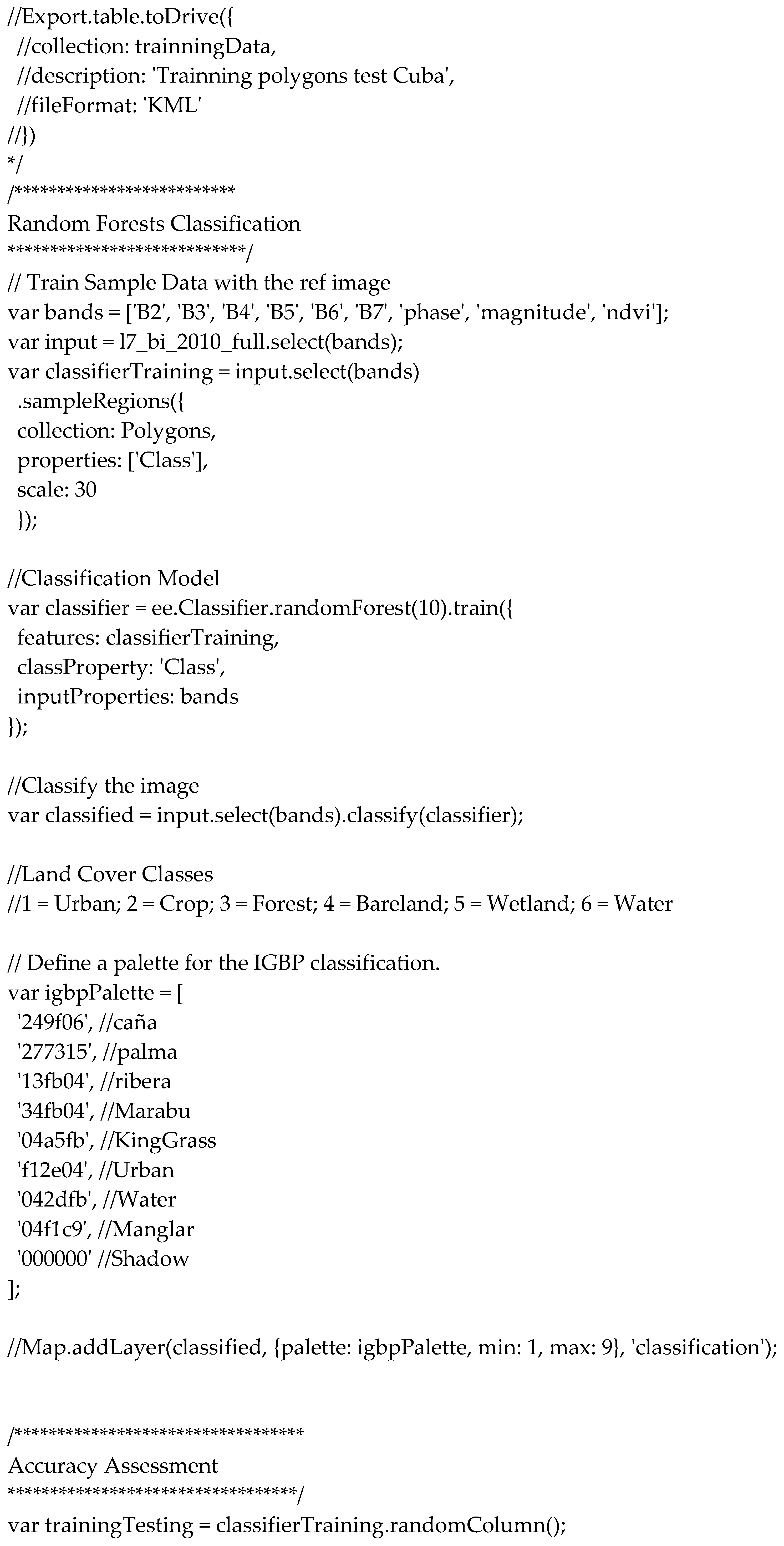

3.1. Valley Mapping at an Elevation Threshold of 100 Meters

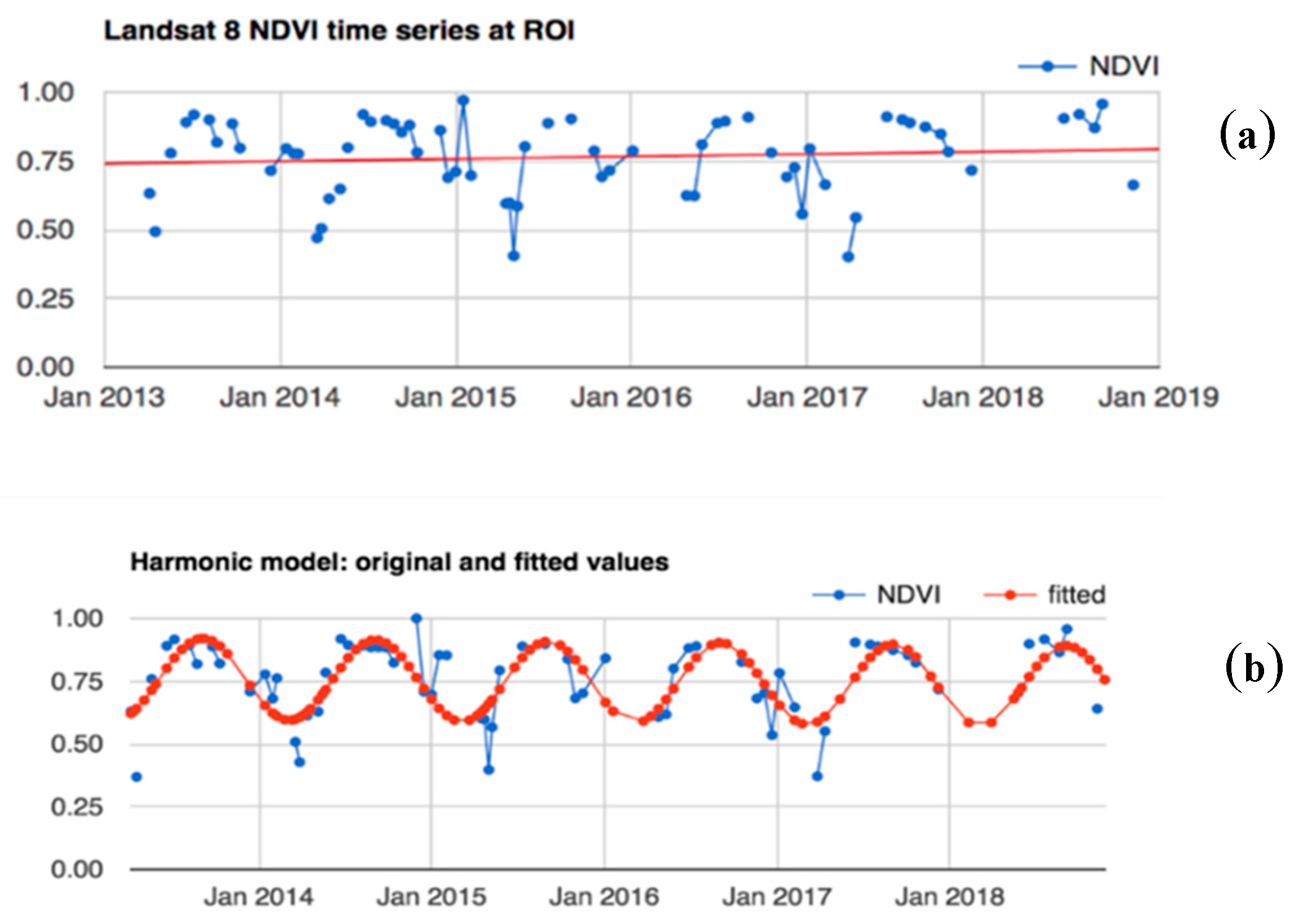

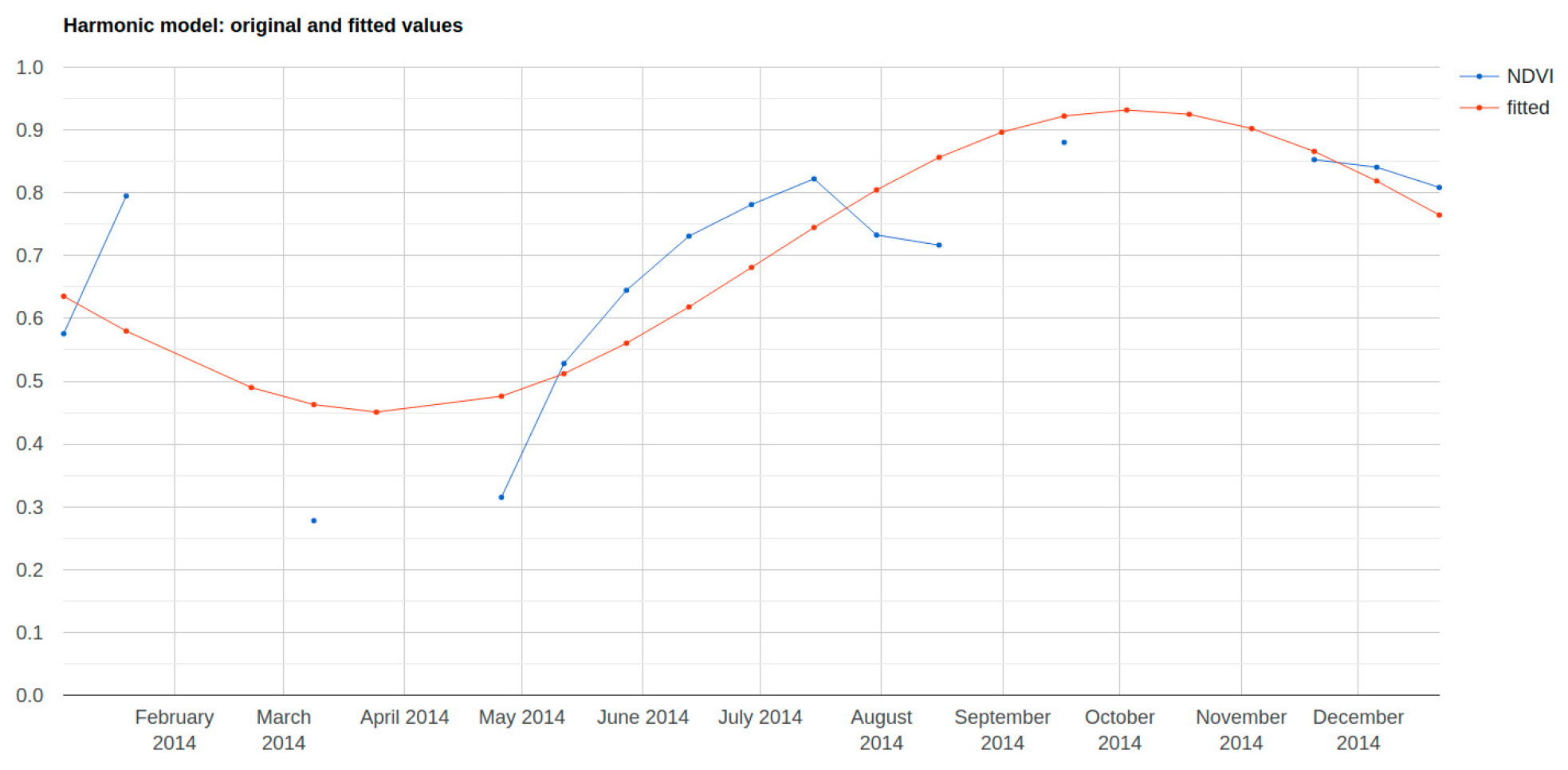

3.2. Harmonic Curves

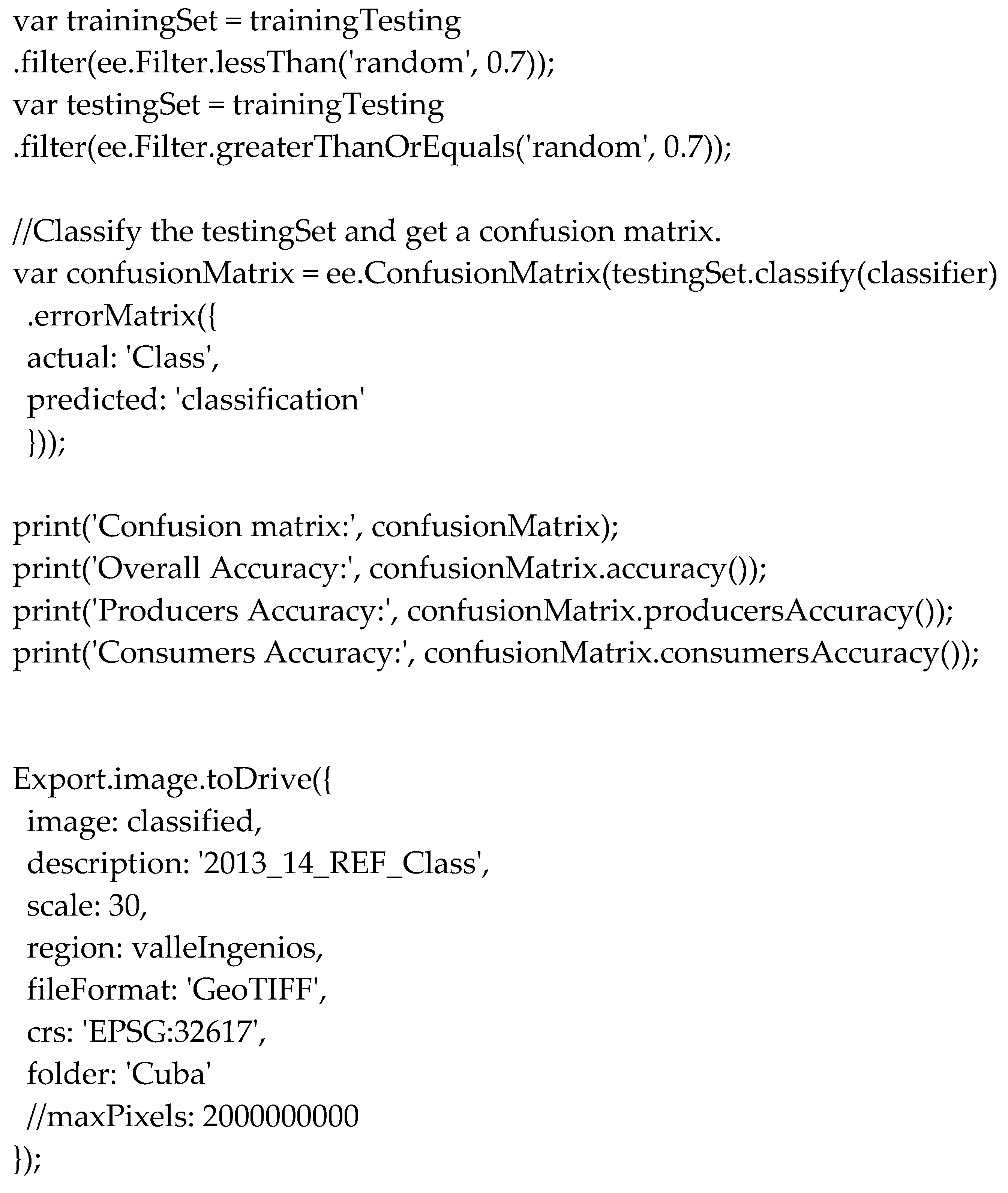

3.3. Confusion Matrix

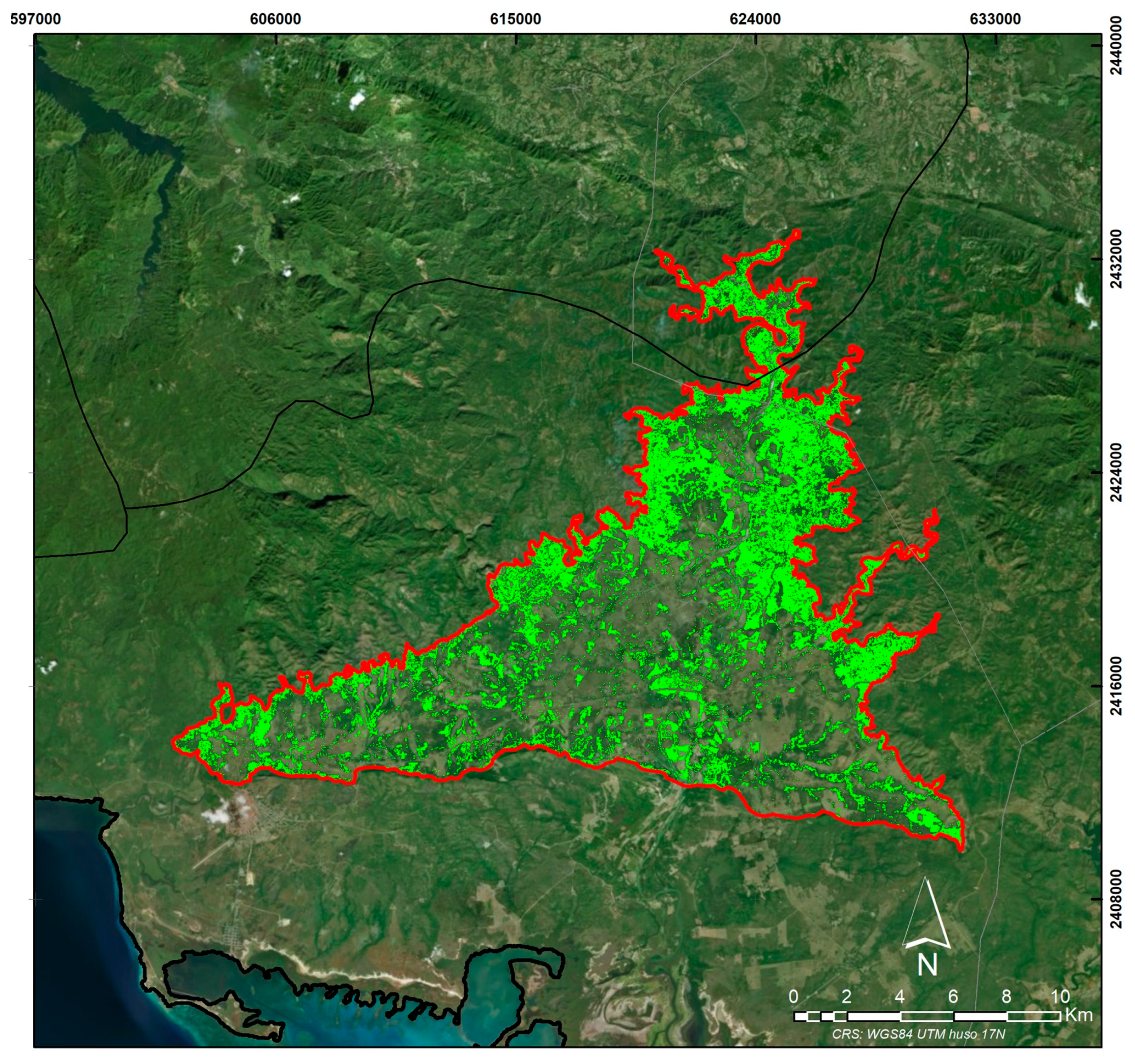

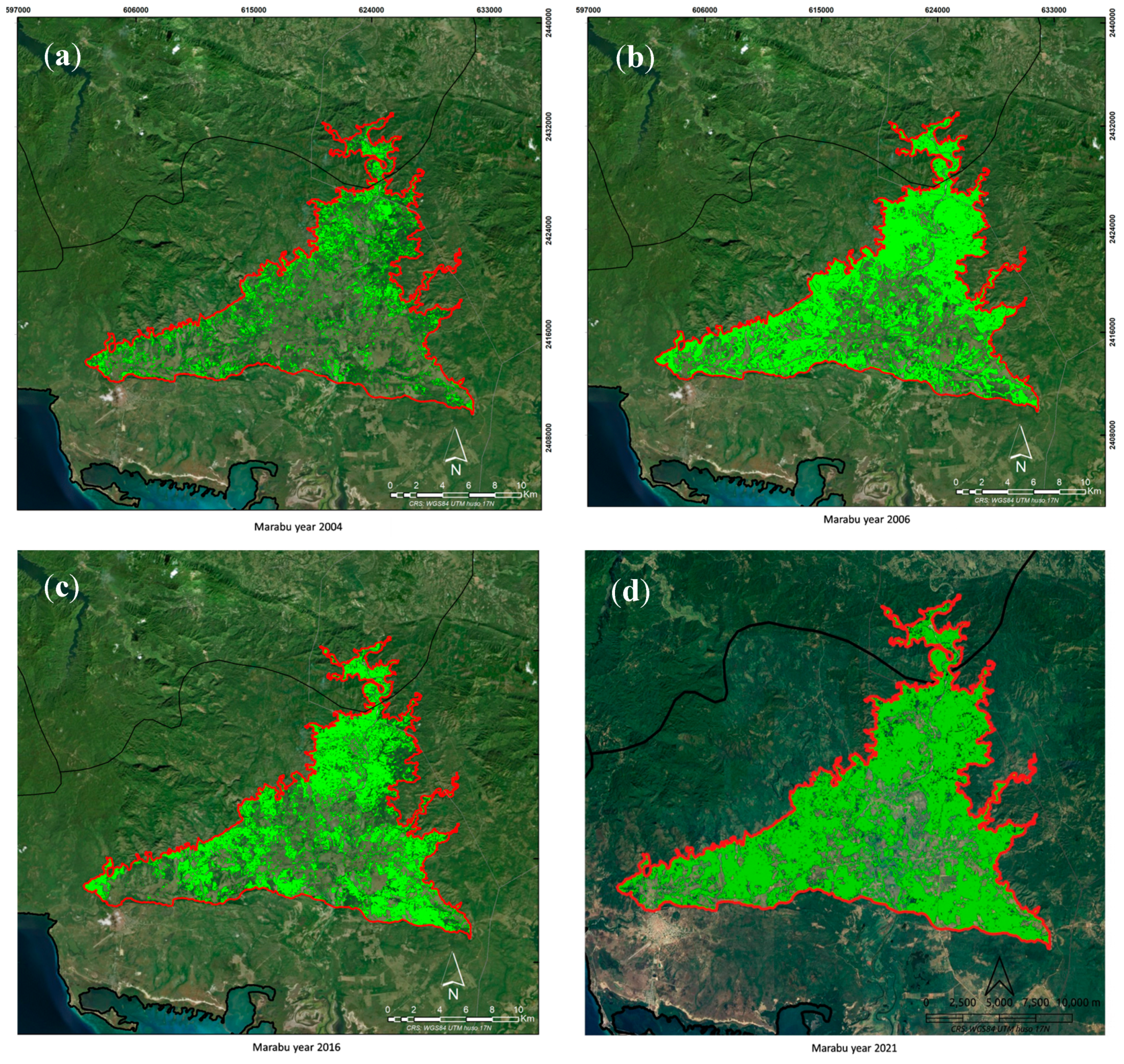

3.4. Coverage Maps and Data

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

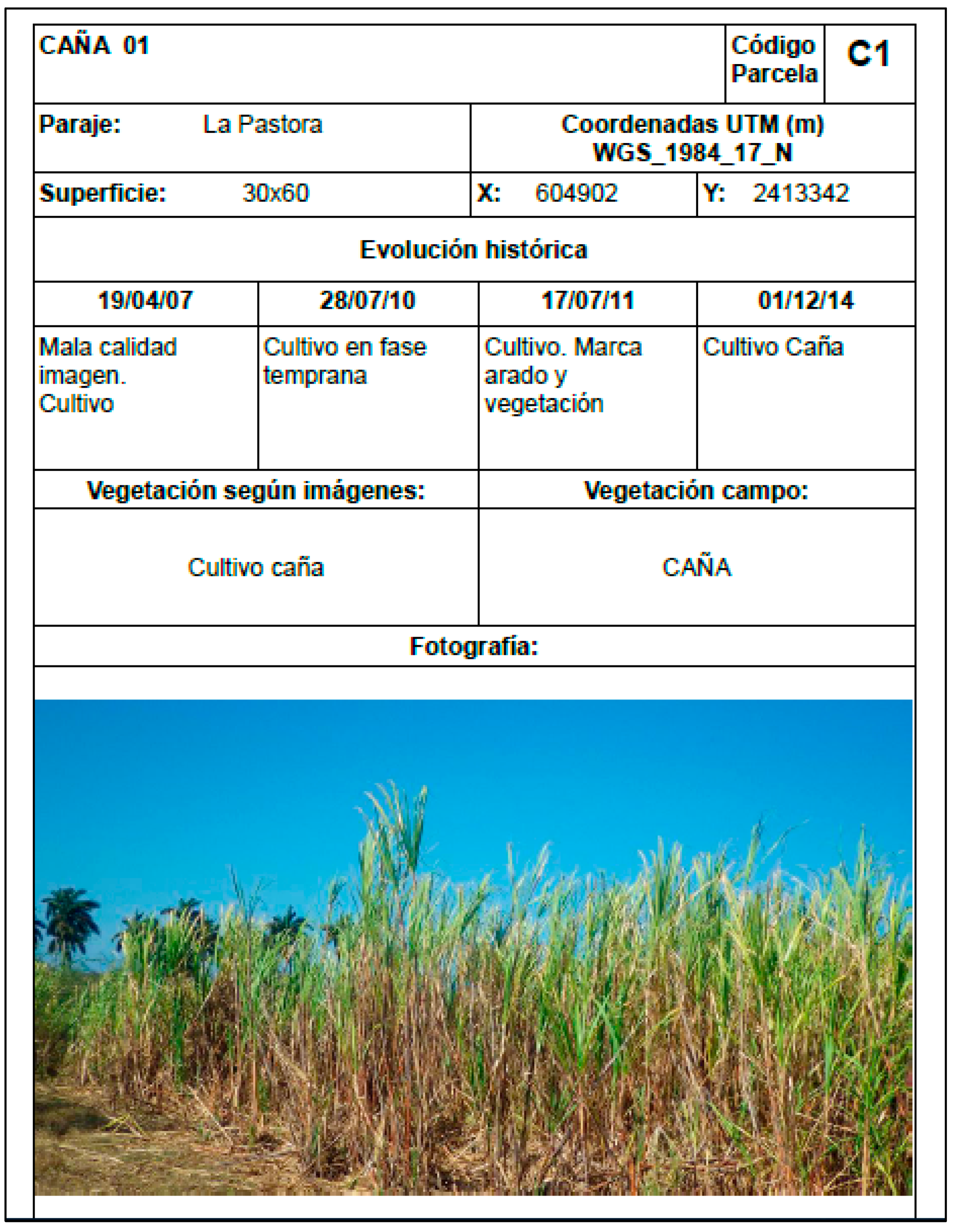

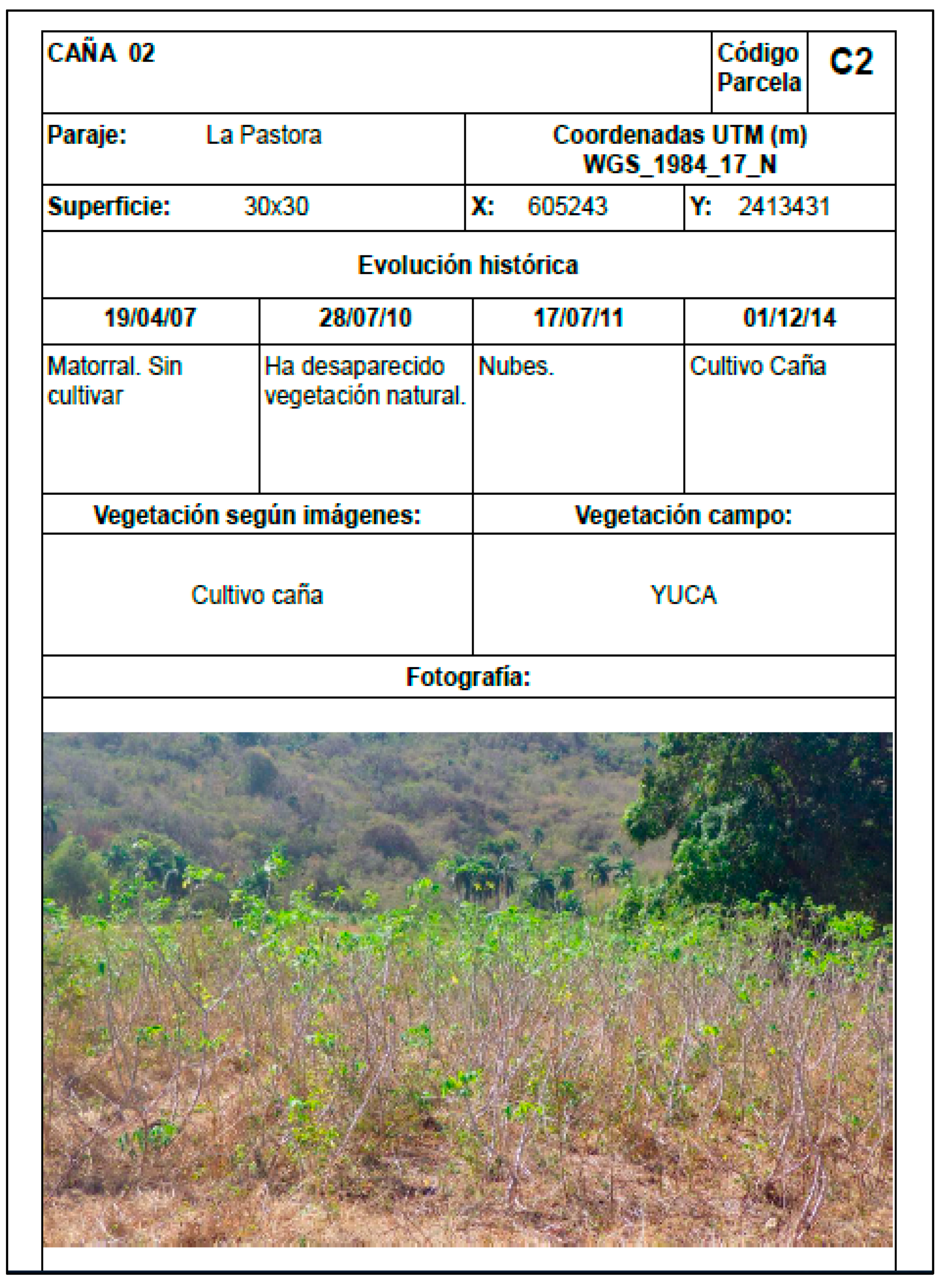

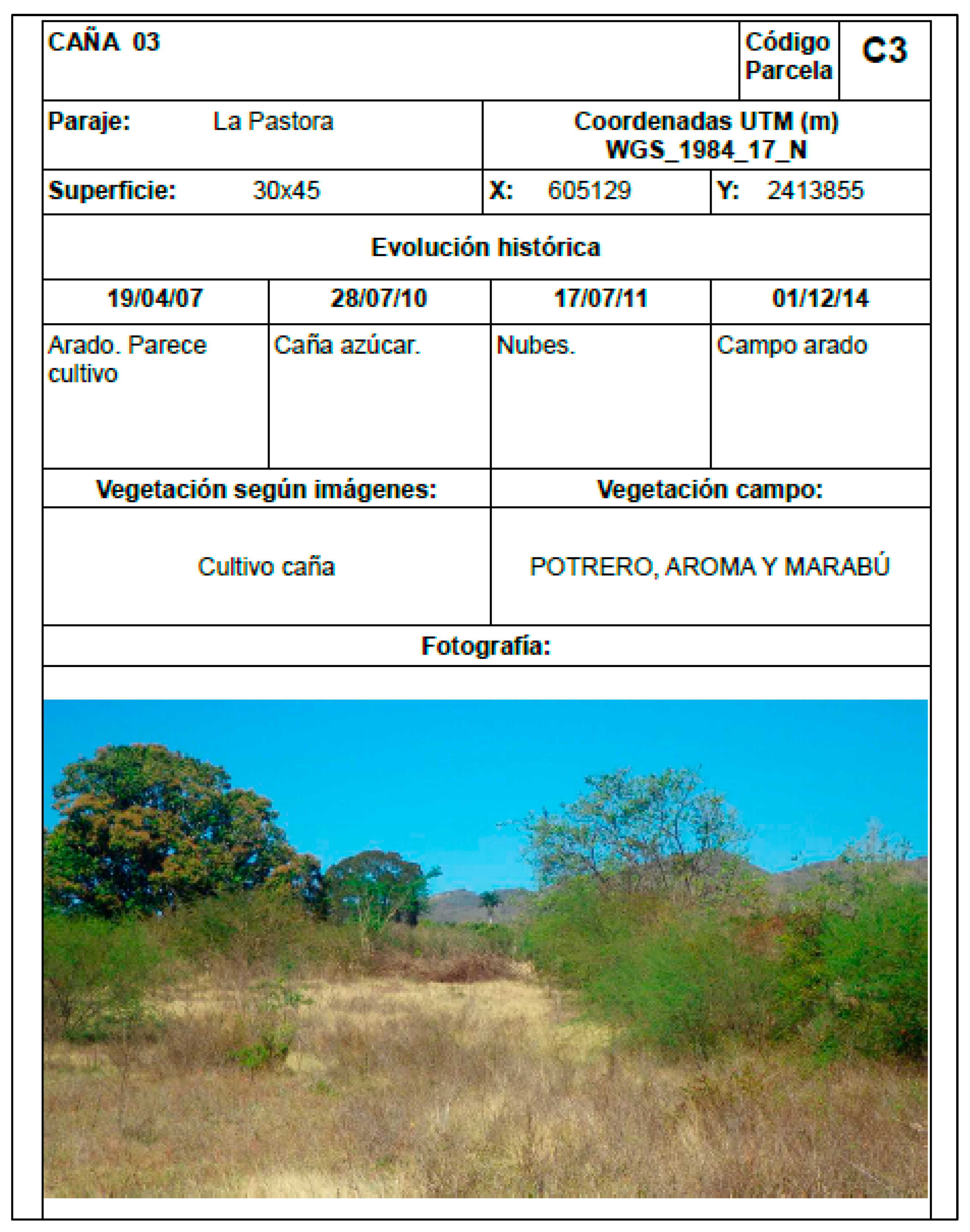

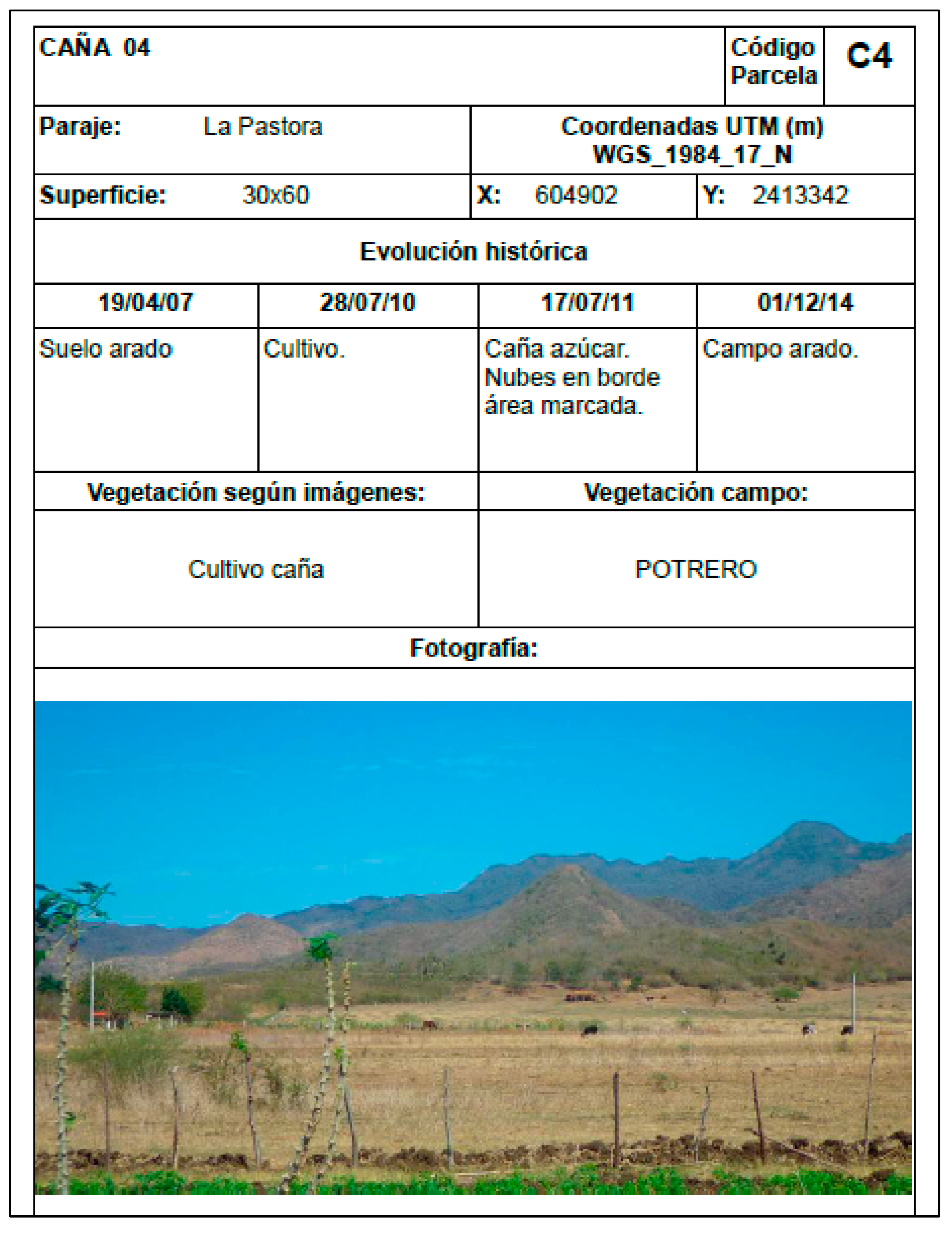

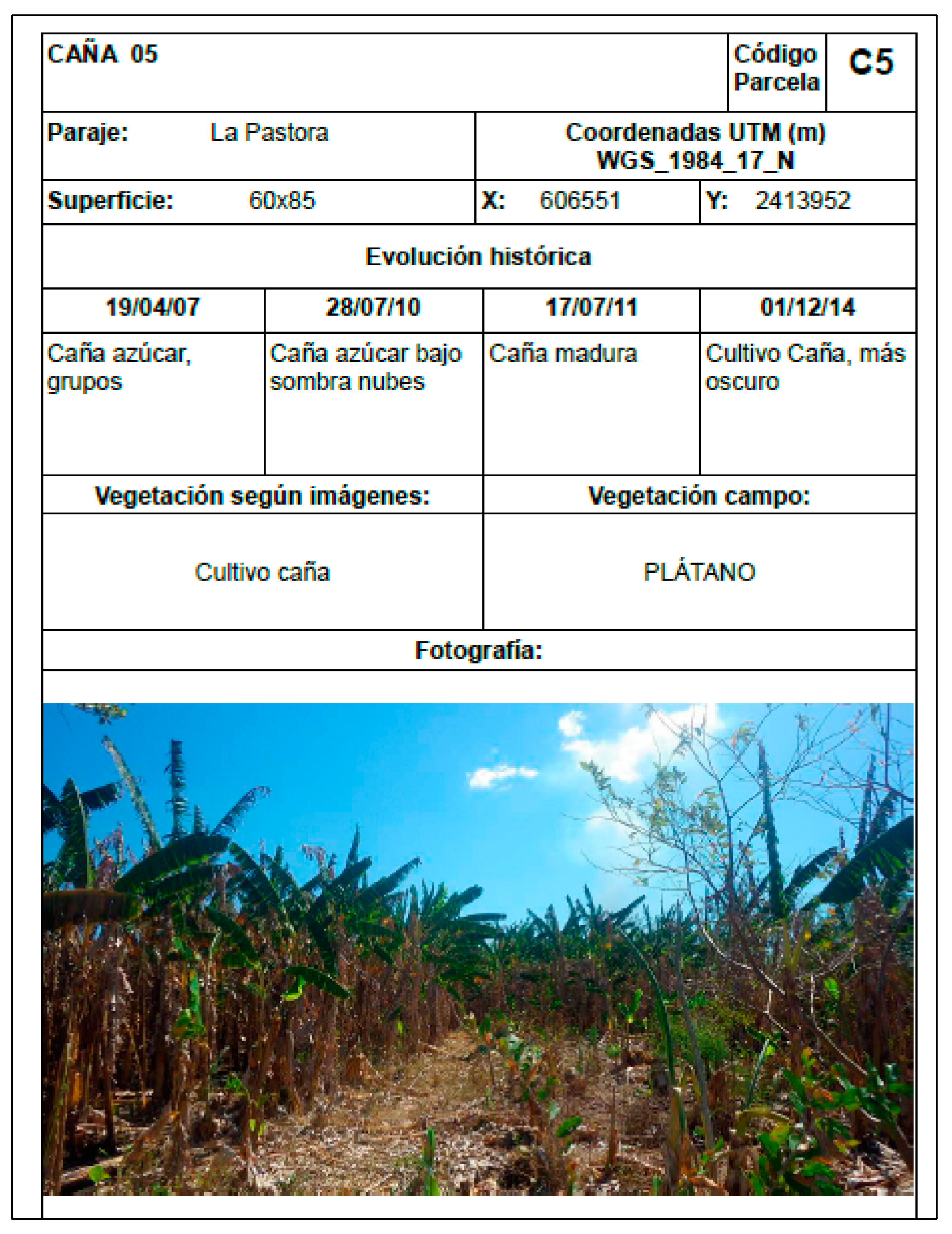

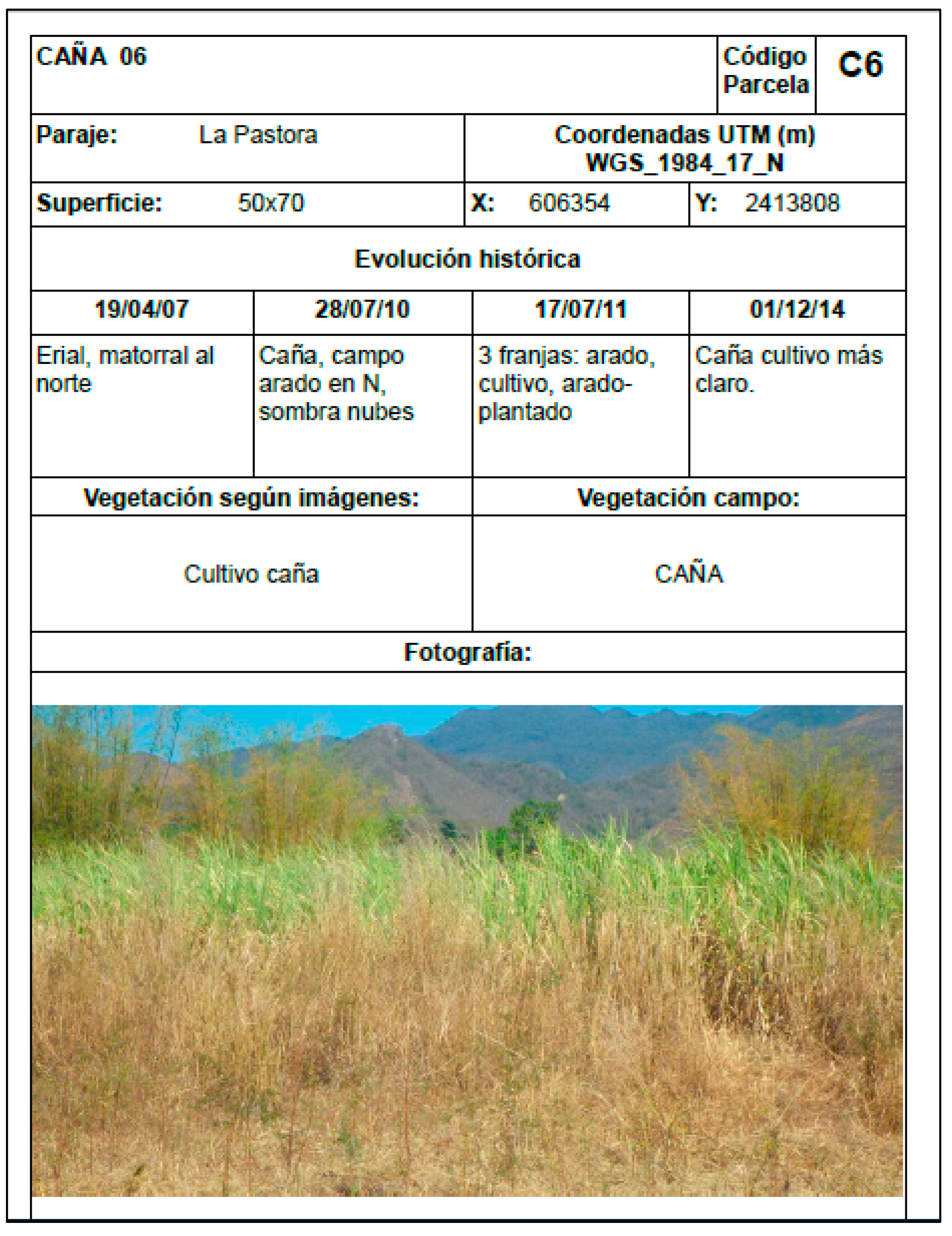

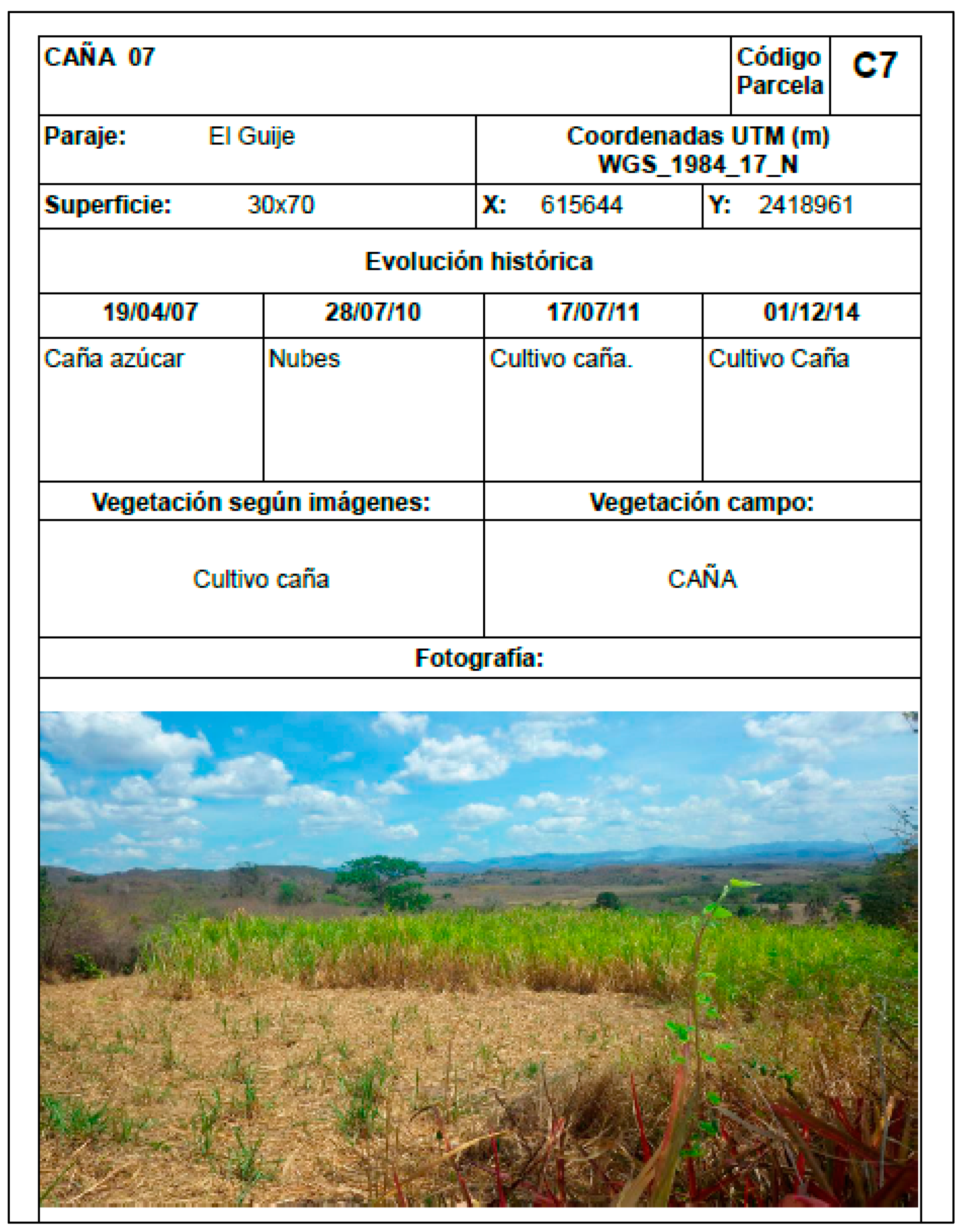

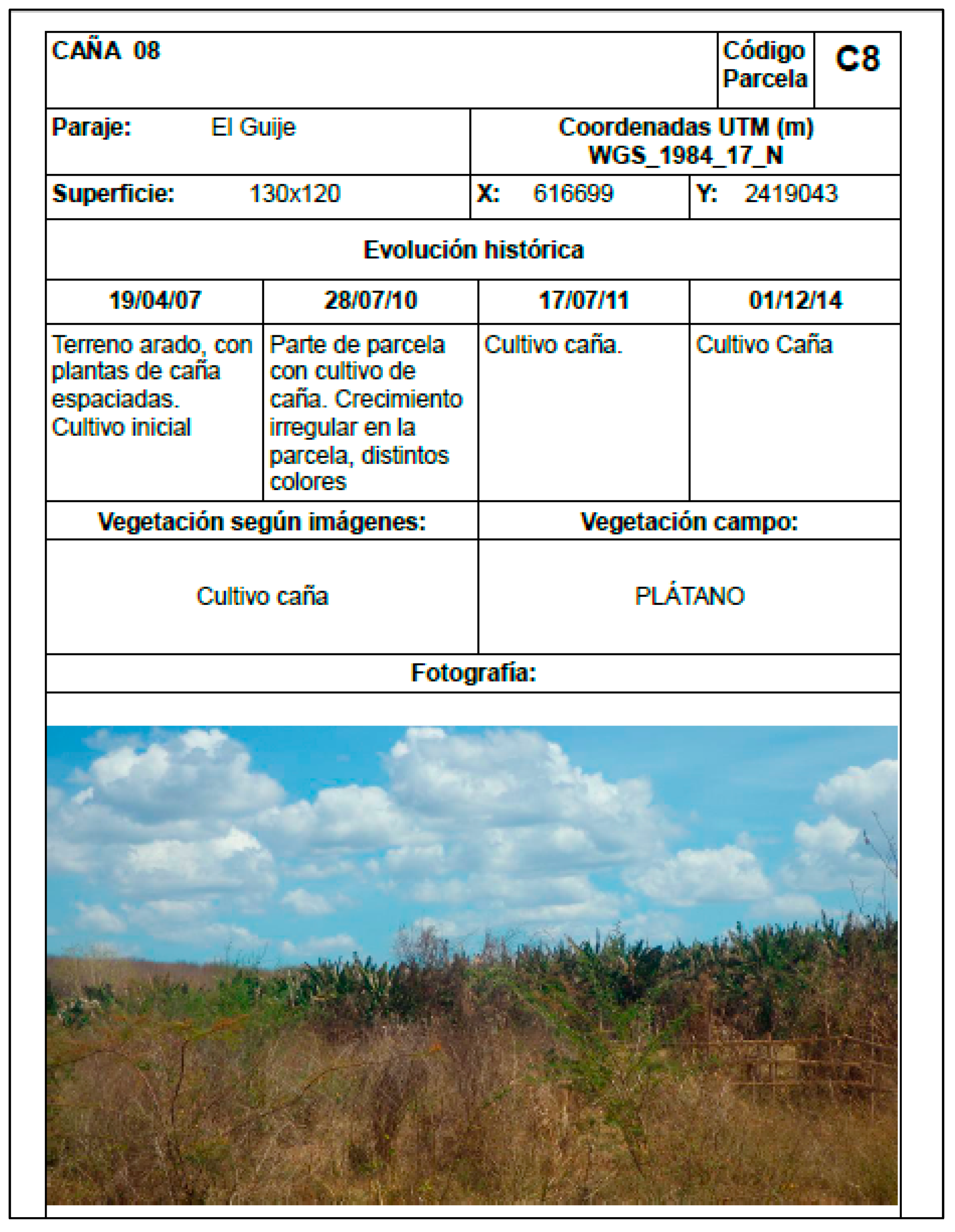

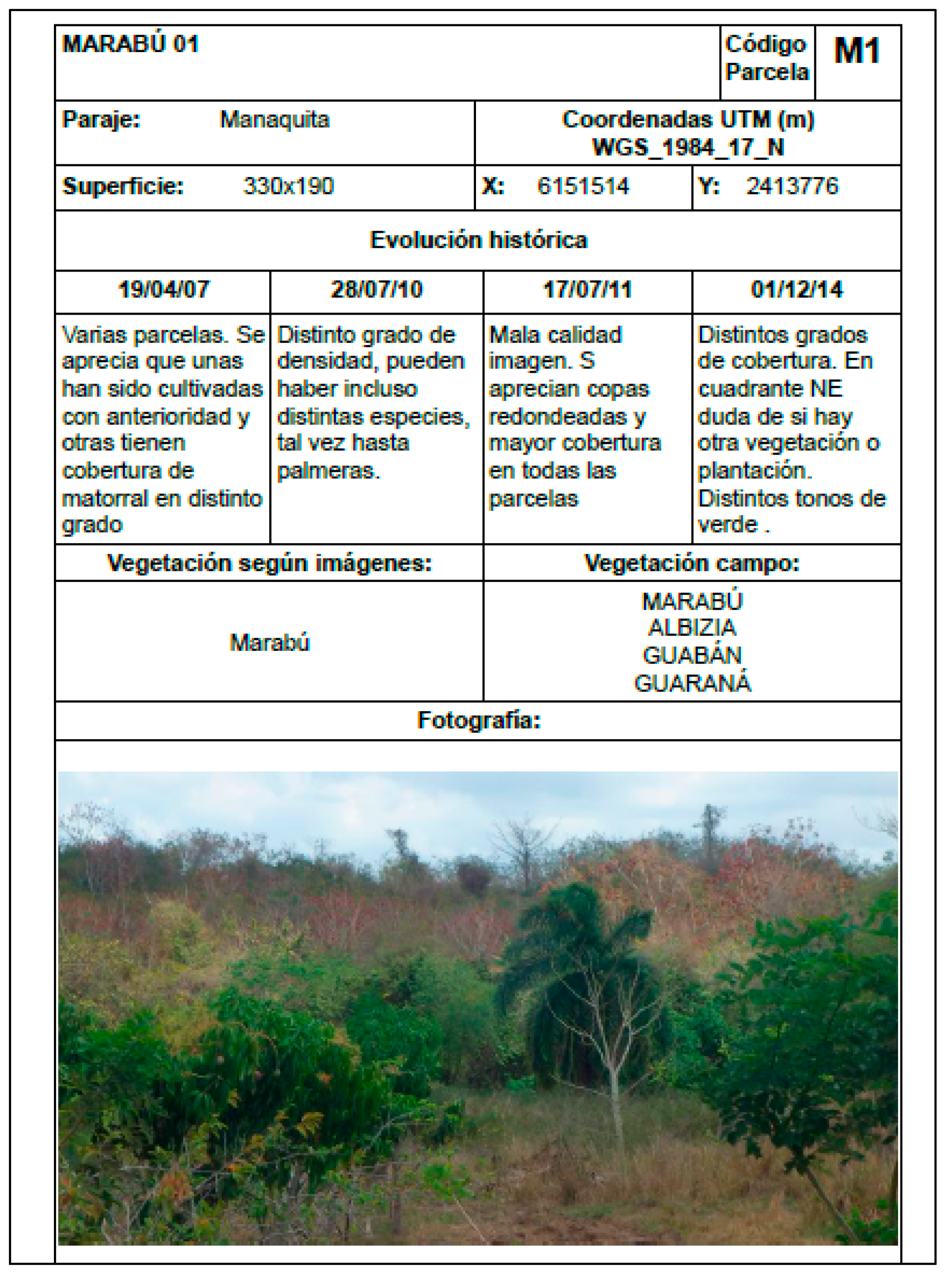

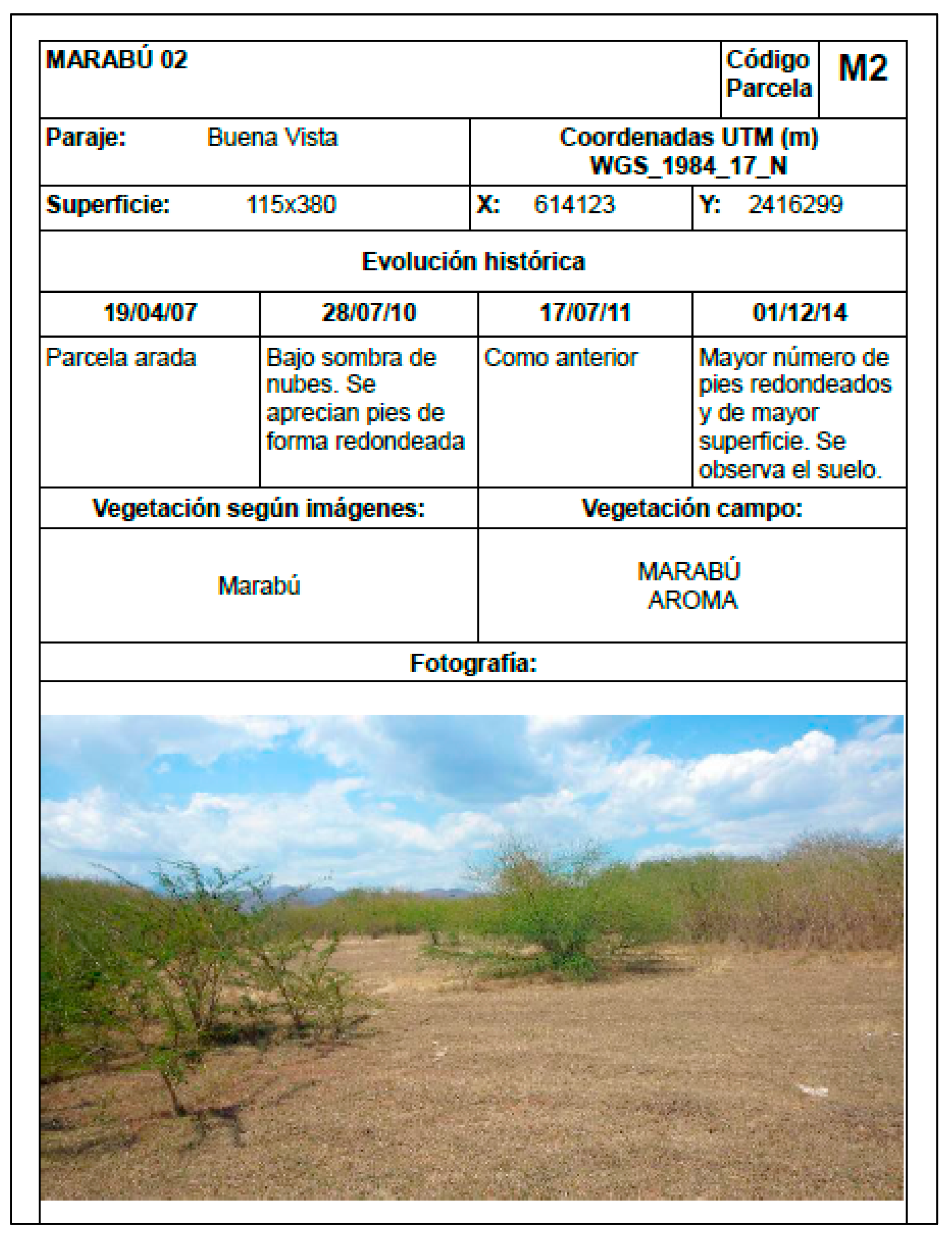

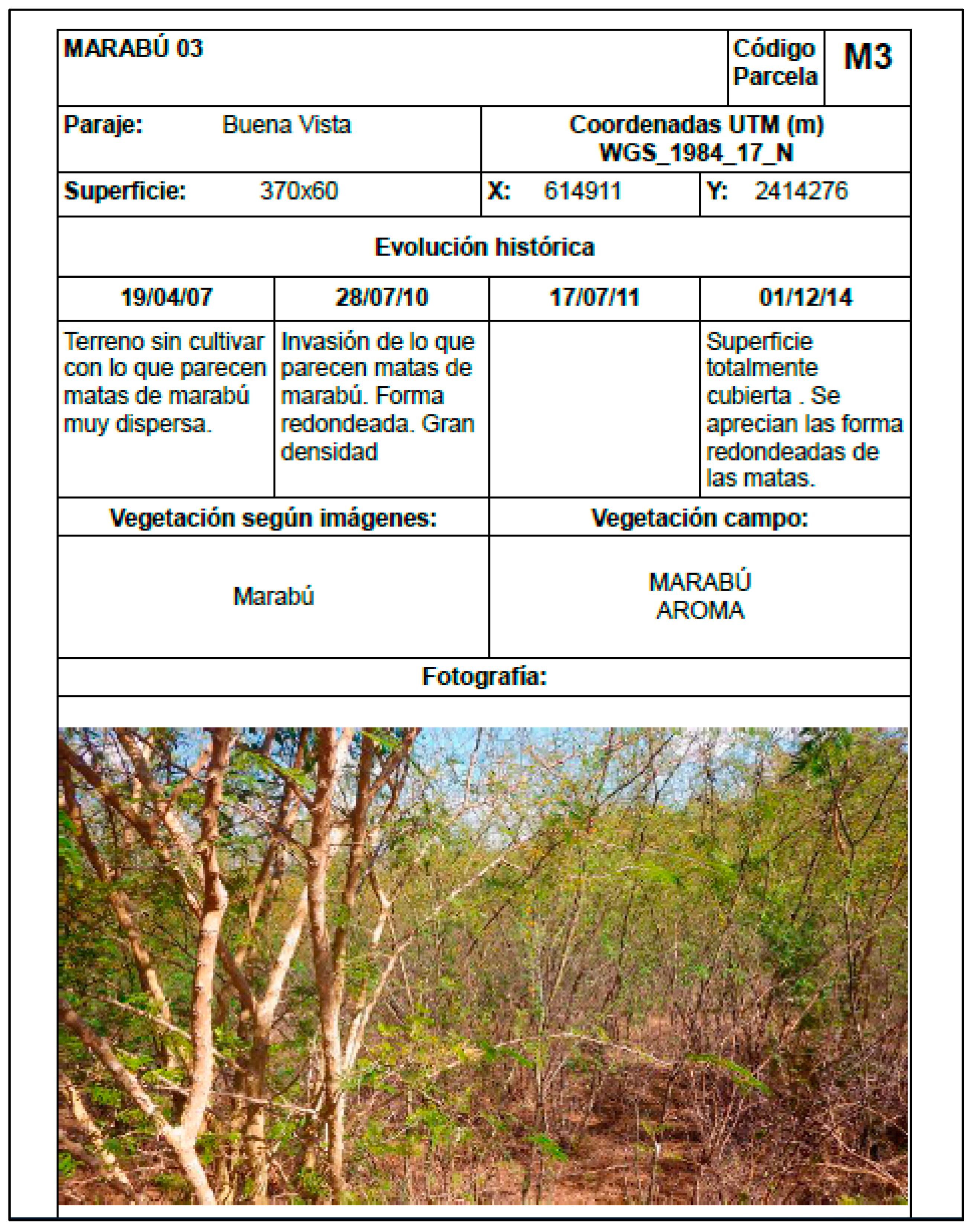

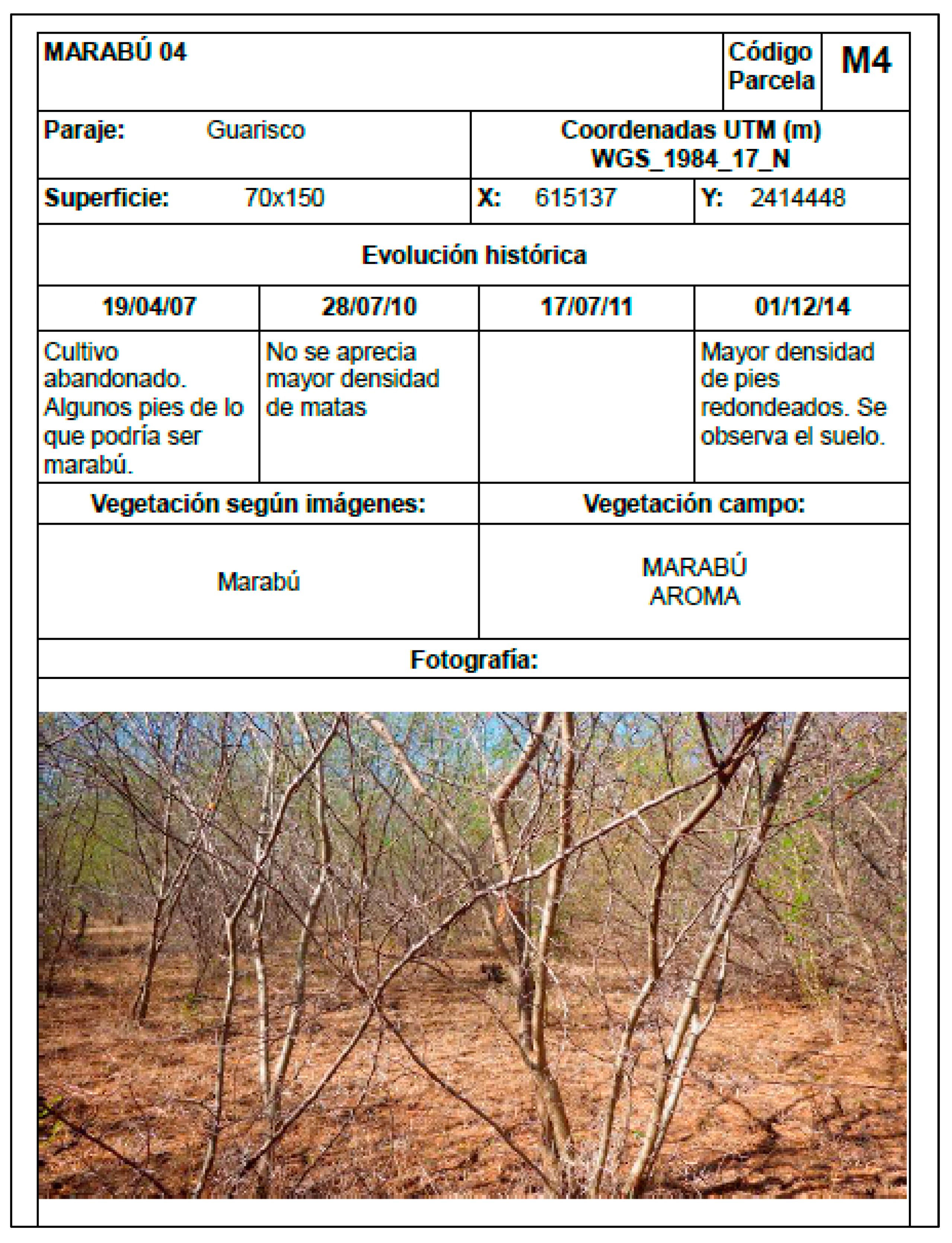

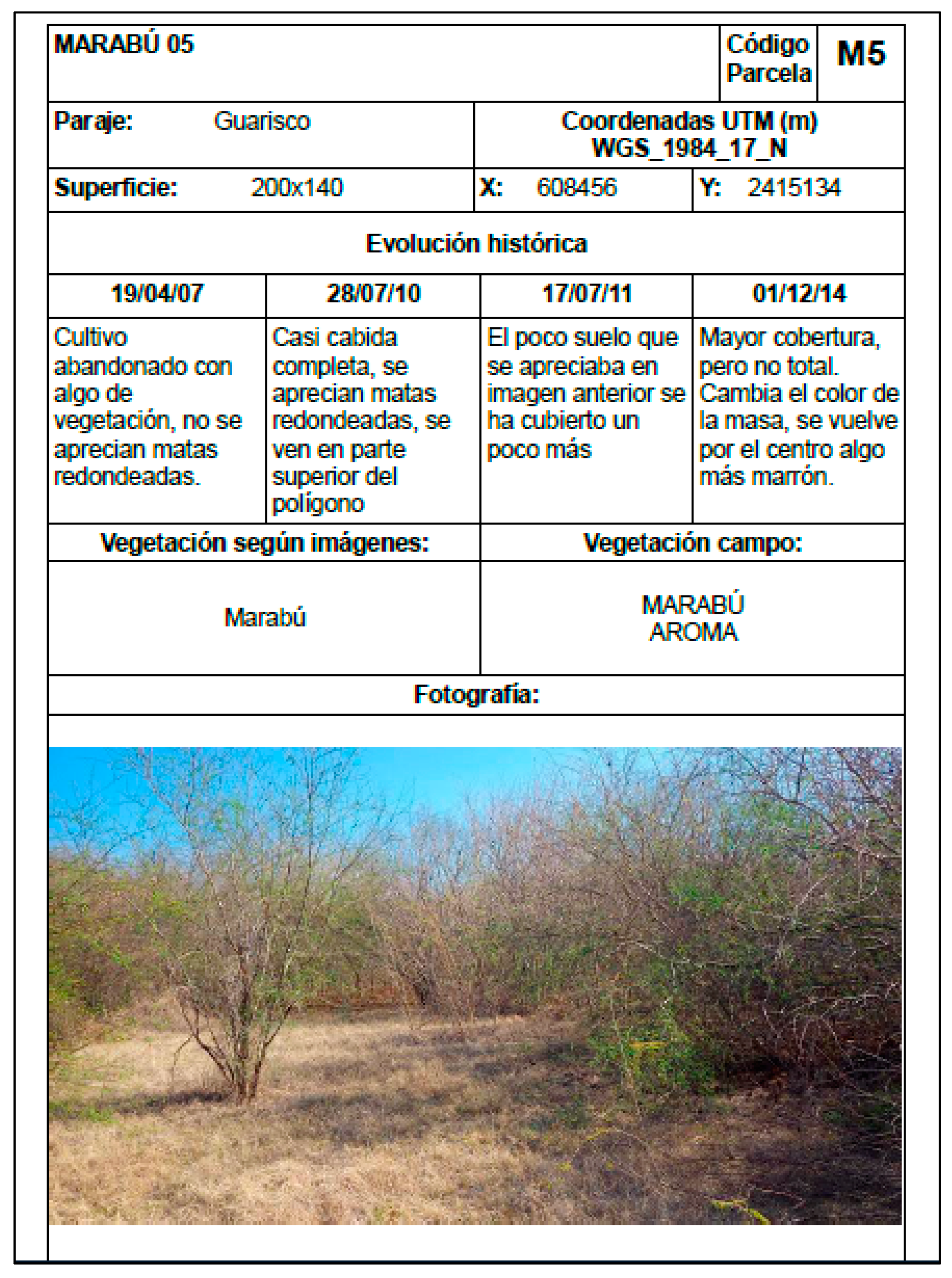

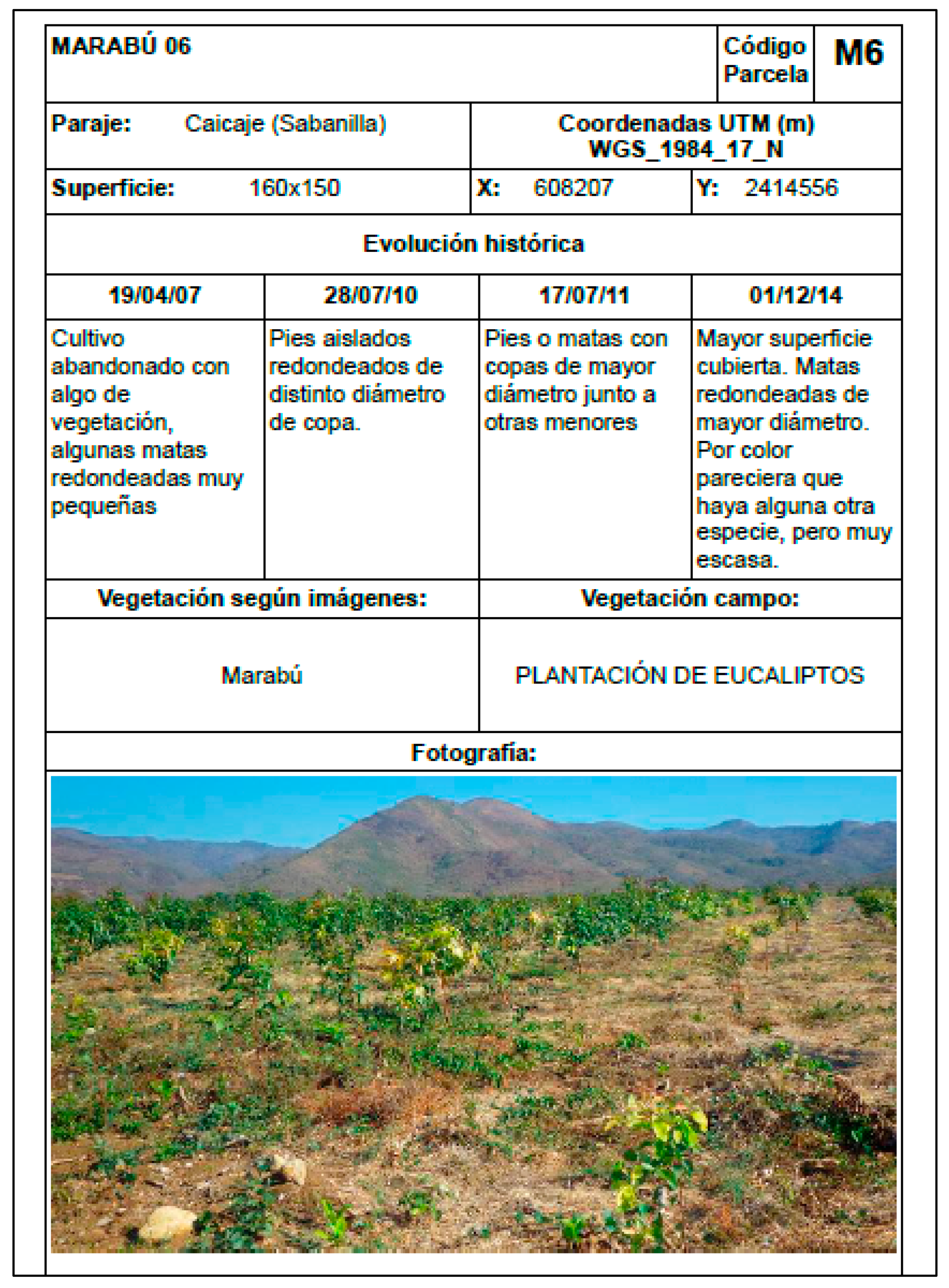

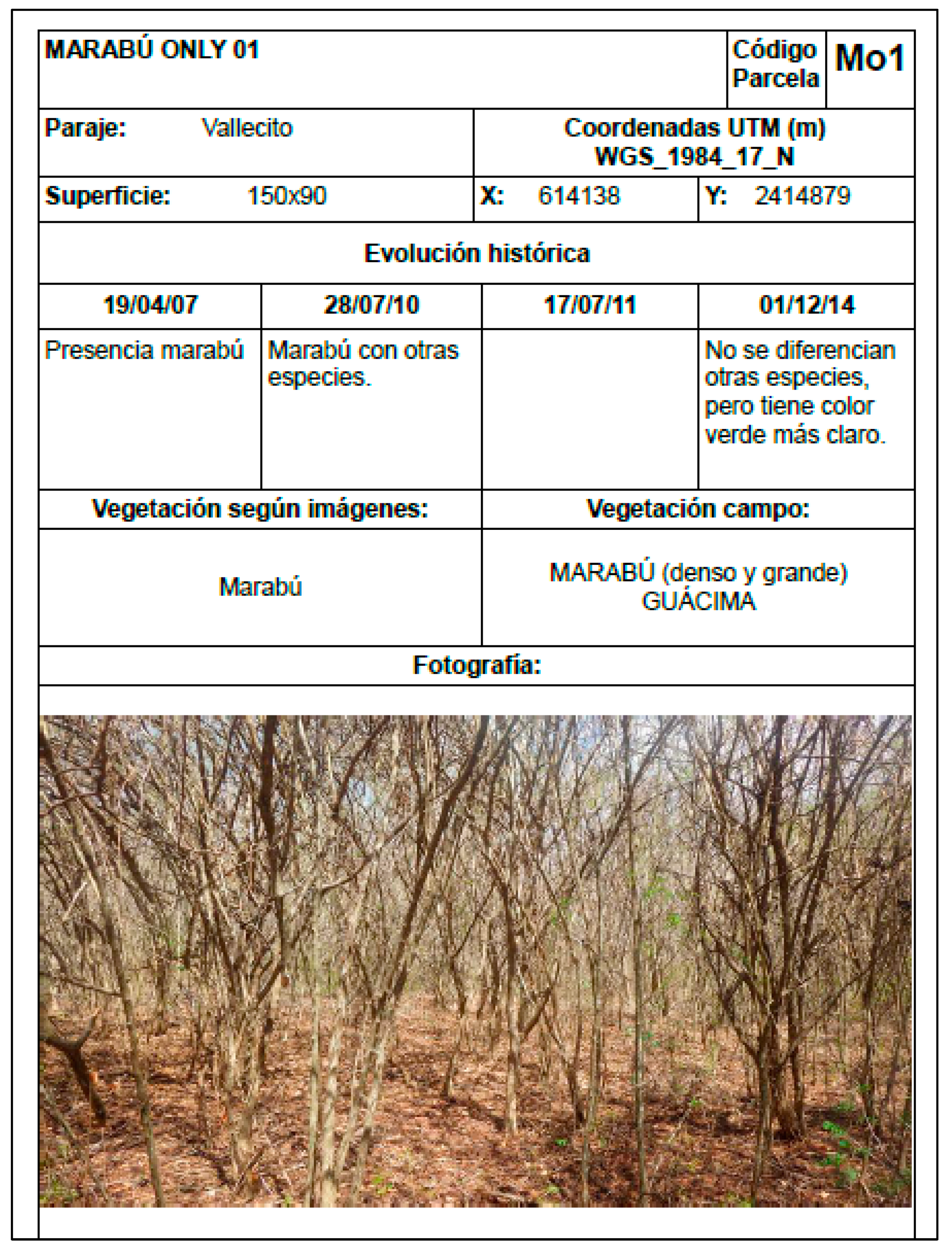

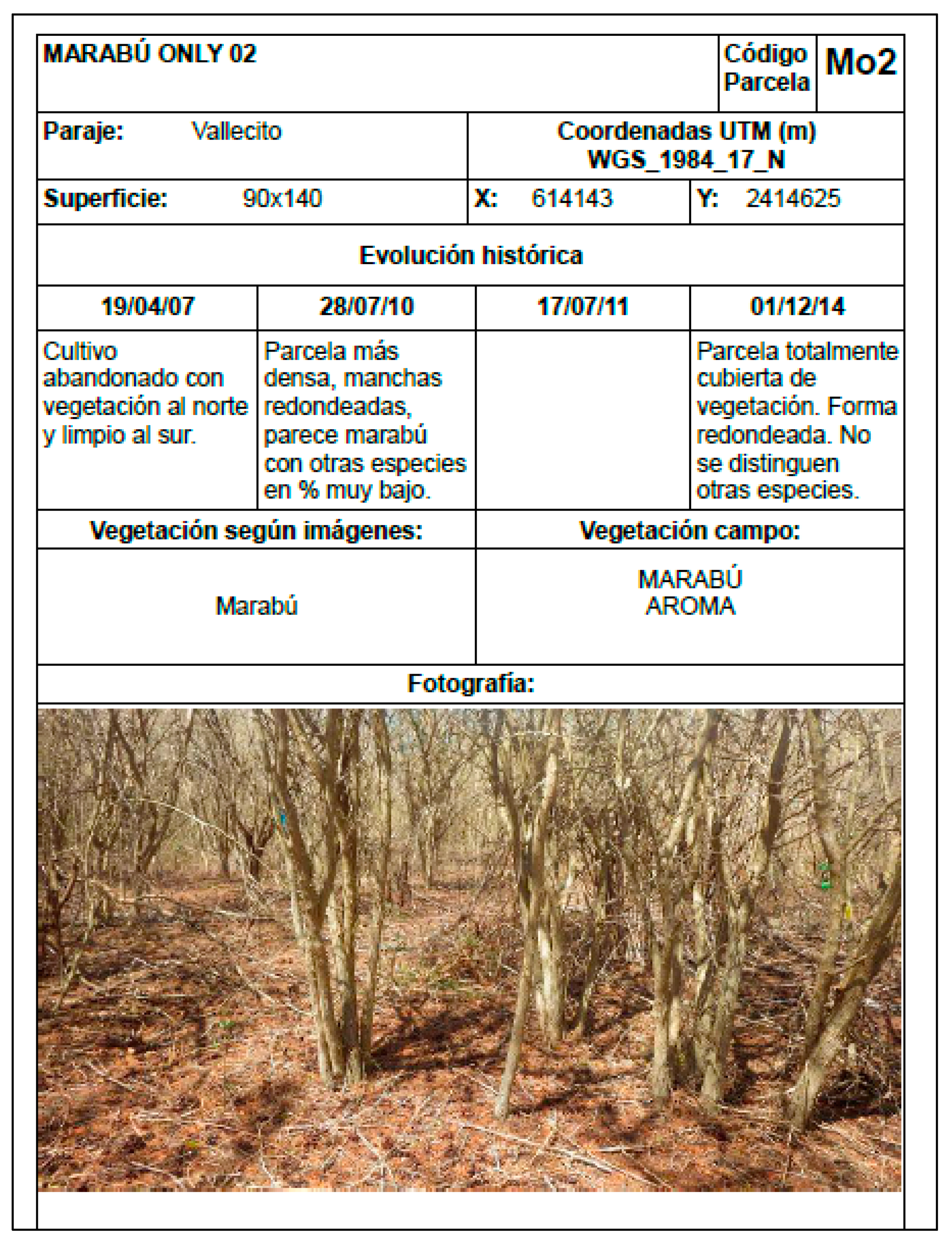

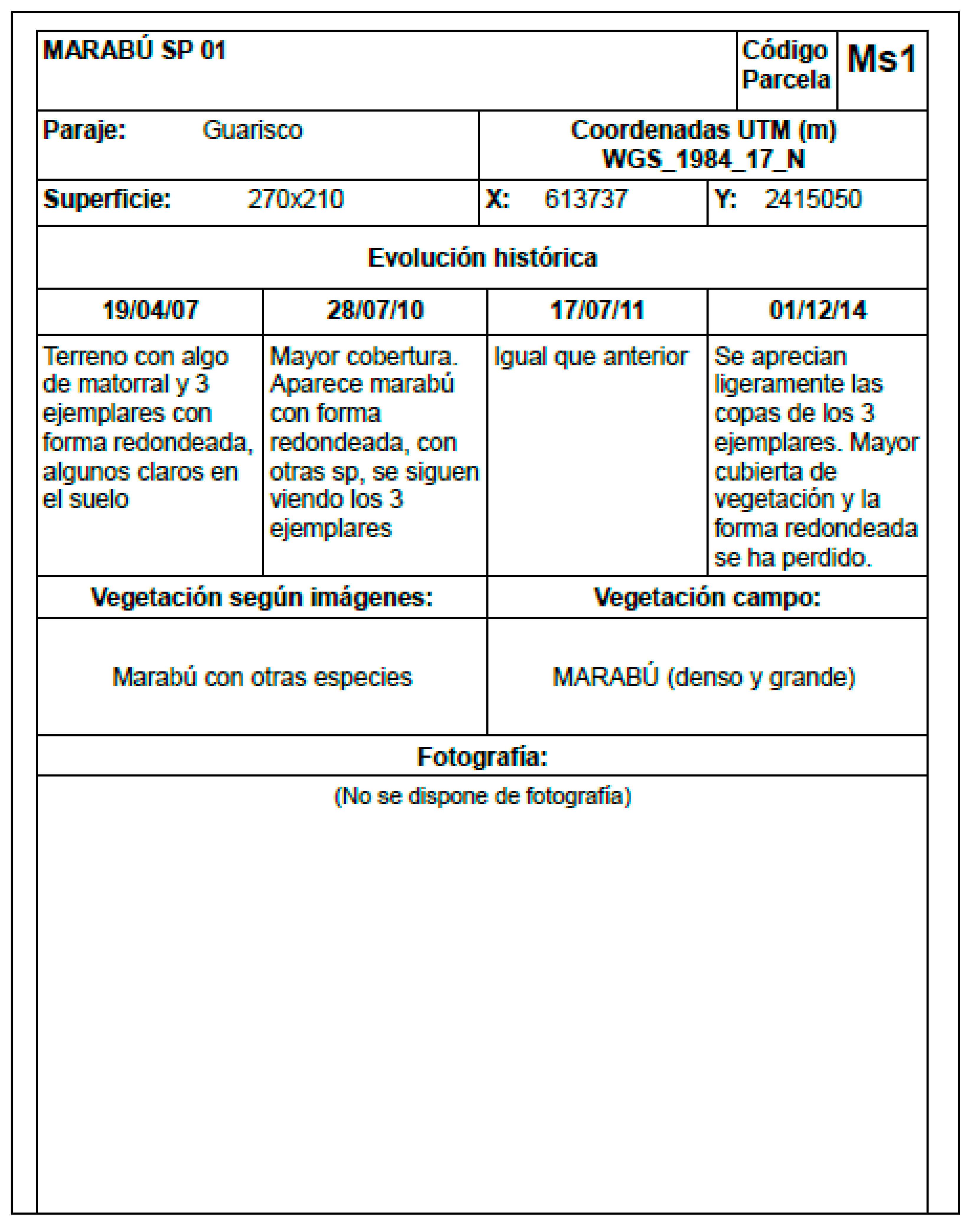

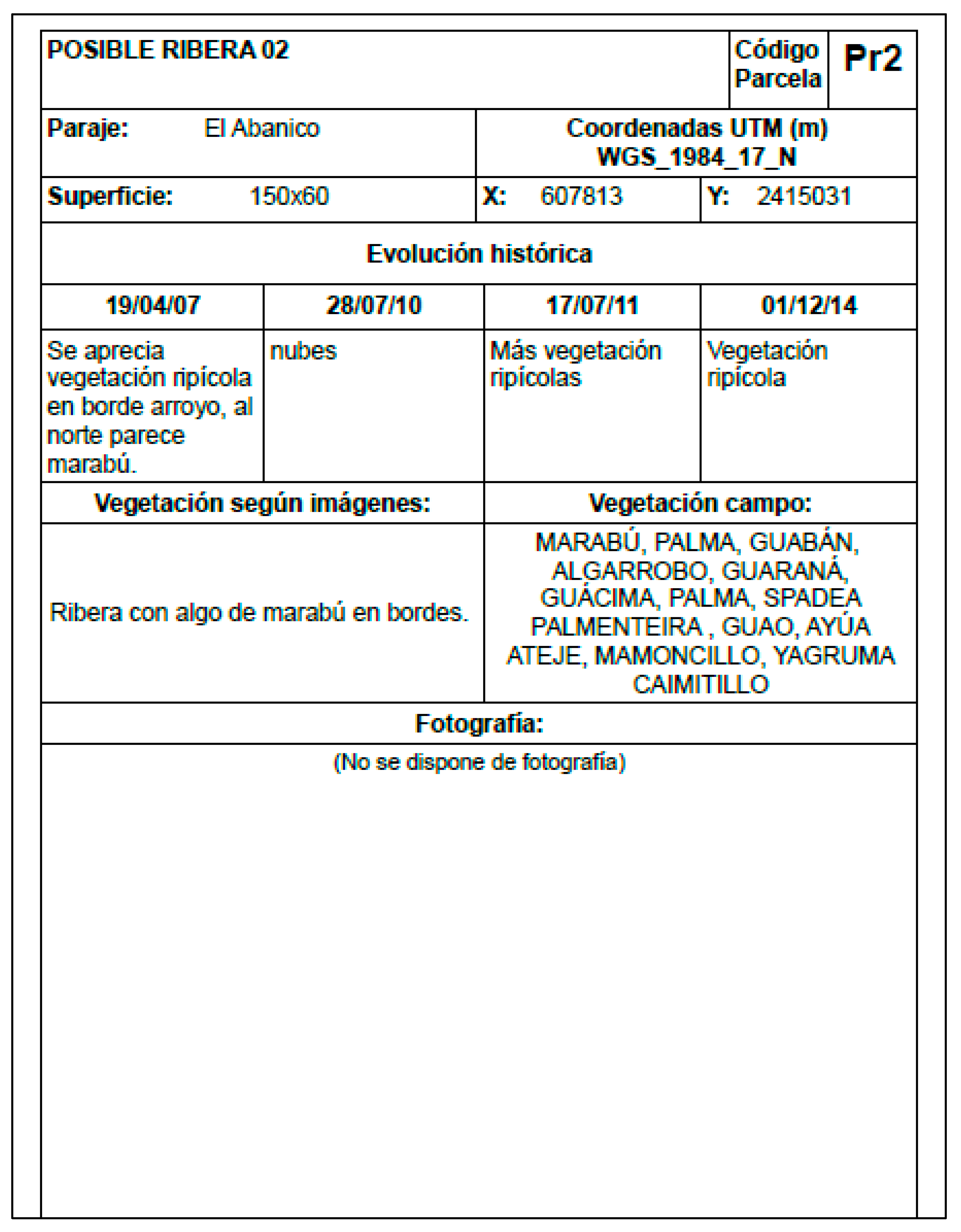

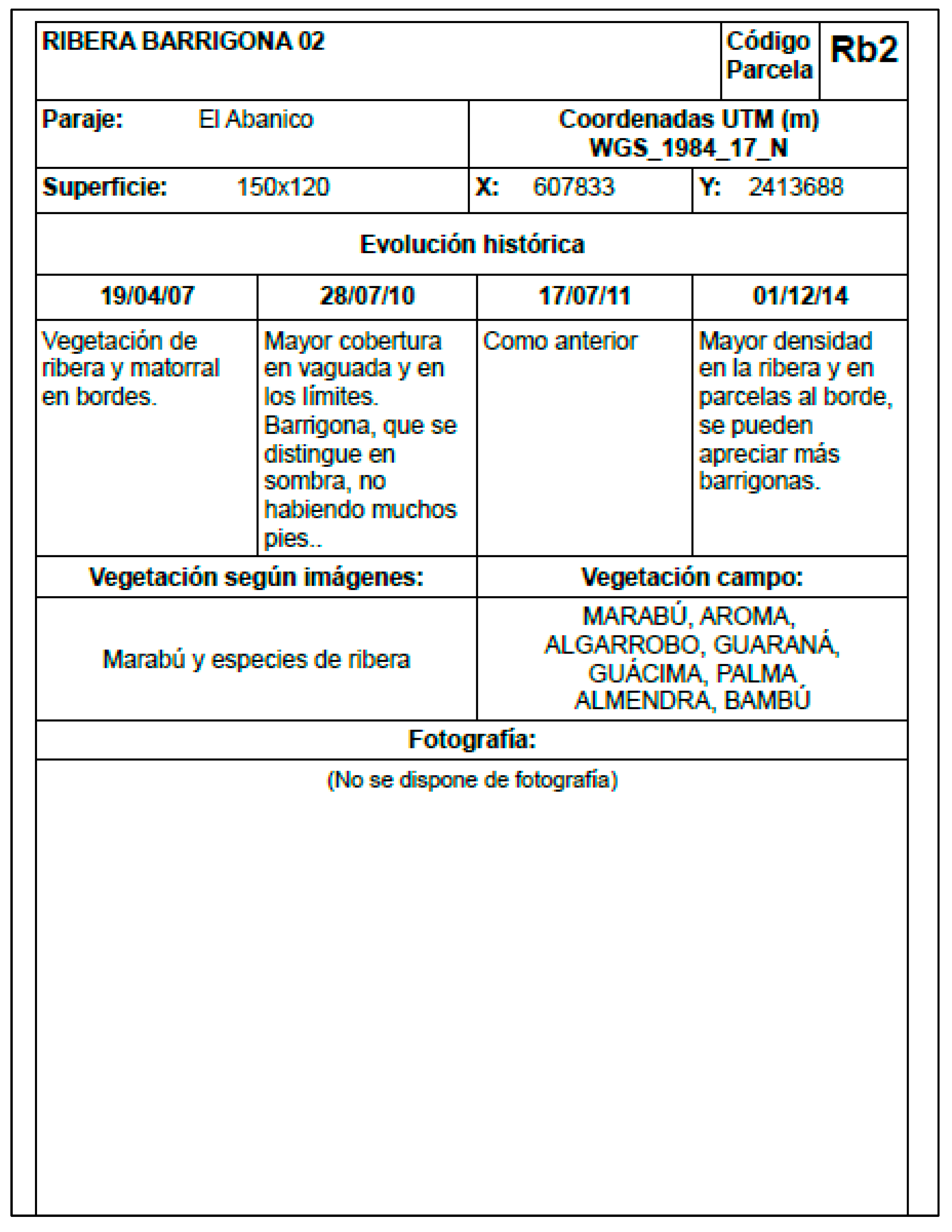

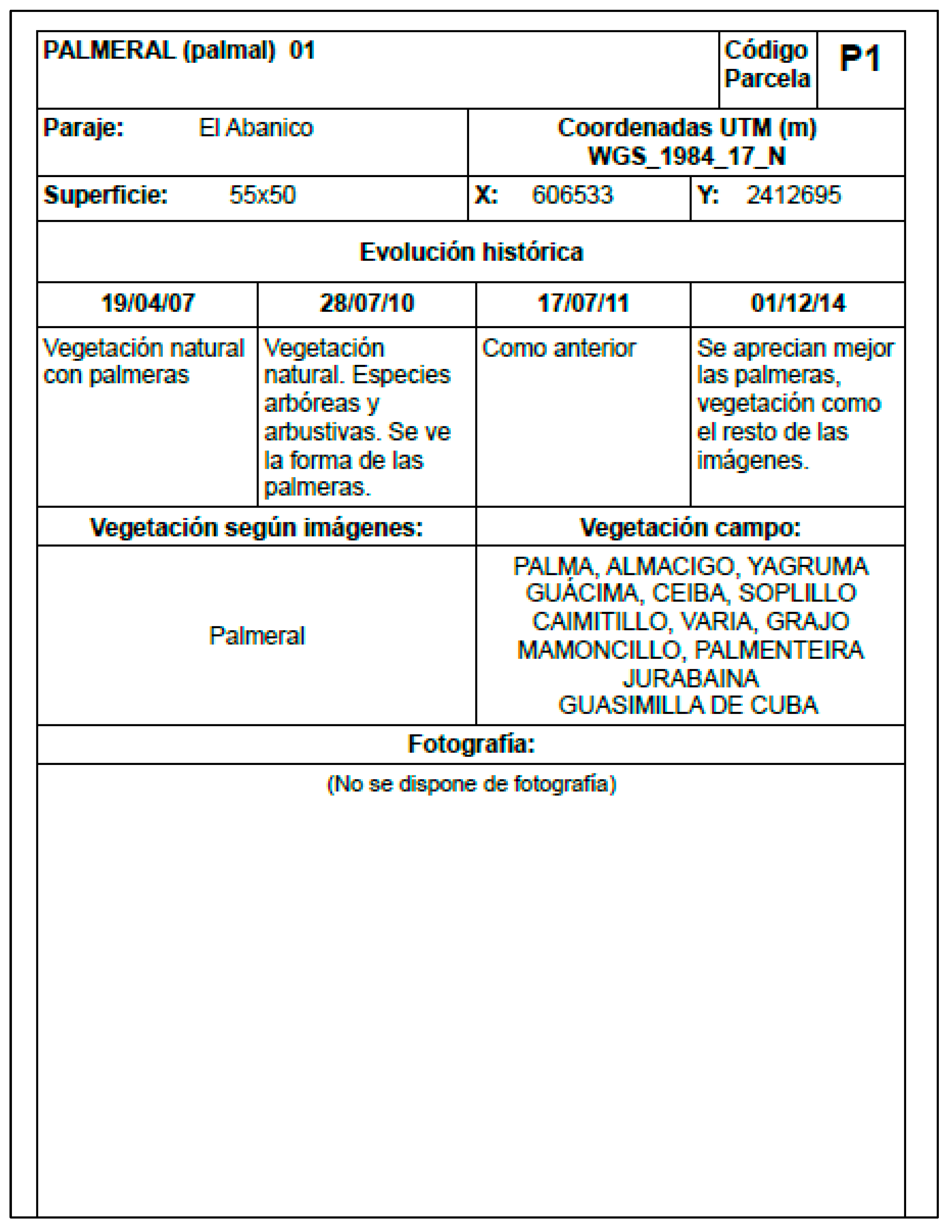

Appendix A. Original Field Sampling Sheets

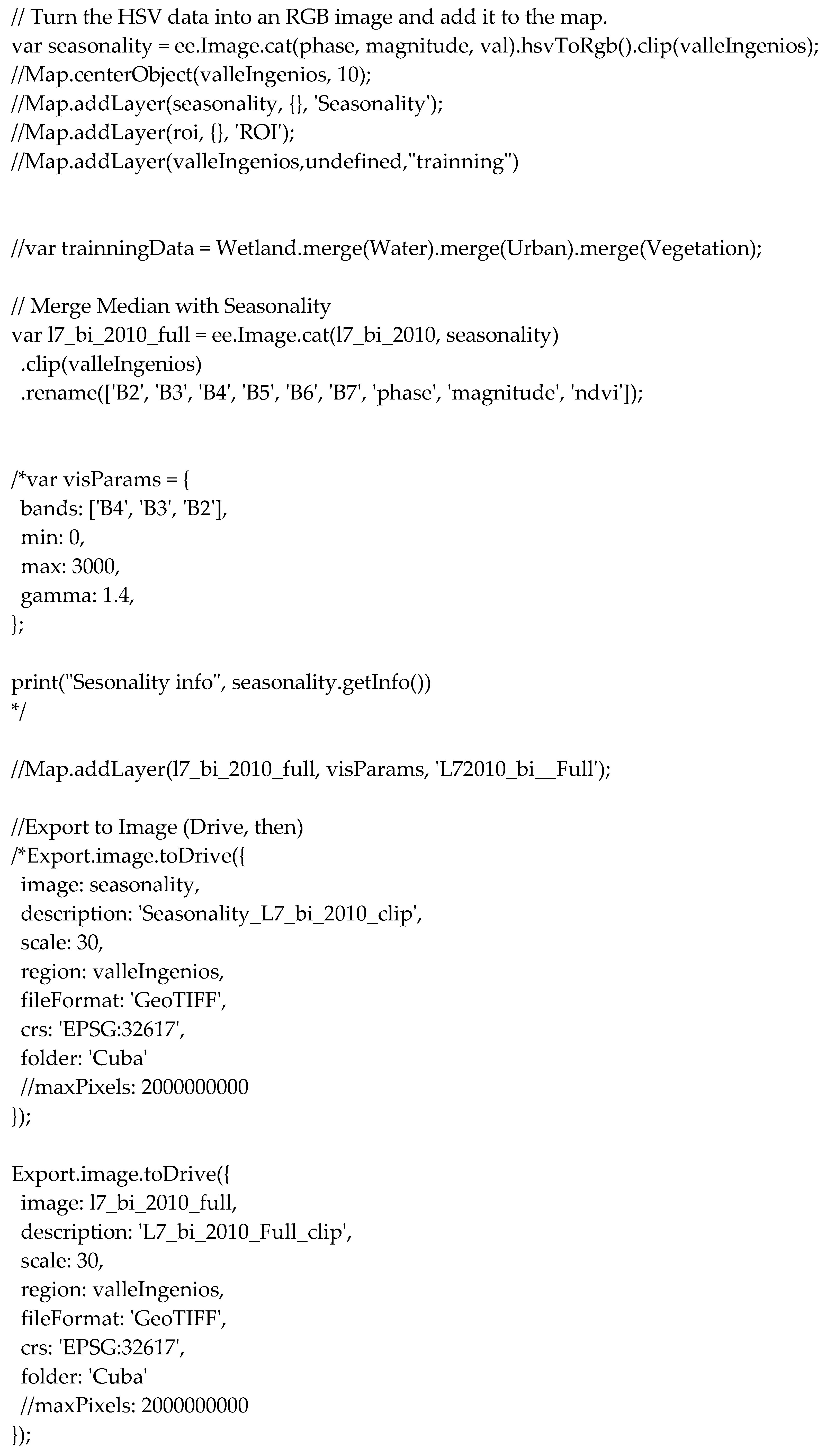

Appendix B. Javascript Code Used in Google Earth Engine Code Editor

Appendix C

References

- Kumar Rai, P.; Singh, J.S. Invasive Alien Plant Species: Their Impact on Environment, Ecosystem Services and Human Health. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 111, 106020. [CrossRef]

- Roy, H.; Pauchard, A.; Stoett, P. Summary for Policymakers of the Thematic Assessment of Invasive Alien Species and Their Control of the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.P.; Raghubanshi, A.S.; Singh, J.S. Lantana Invasion: An Overview. Weed Biol. Manag. 2005, 5, 157–165. [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, D.M. Interactions between Resource Availability and Enemy Release in Plant Invasion. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 887–895. [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, P.; Jarošík, V.; Hulme, P.E.; Pergl, J.; Hejda, M.; Schaffner, U.; Vilà, M. A Global Assessment of Invasive Plant Impacts on Resident Species, Communities and Ecosystems: The Interaction of Impact Measures, Invading Species’ Traits and Environment. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2012, 18, 1725–1737. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Kaur, R.; Chauhan, B.S. Understanding Crop-Weed-Fertilizer-Water Interactions and Their Implications for Weed Management in Agricultural Systems. Crop Prot. 2018, 103, 65–72. [CrossRef]

- Black, R.; Bartlett, D.M.F. Biosecurity Frameworks for Cross-Border Movement of Invasive Alien Species. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 105, 113–119. [CrossRef]

- Pejchar, L.; Mooney, H.A. Invasive Species, Ecosystem Services and Human Well-Being. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 24, 497–504. [CrossRef]

- Colautti, R.I.; Bailey, S.A.; Van Overdijk, C.D.A.; Amundsen, K.; MacIsaac, H.J. Characterised and Projected Costs of Nonindigenous Species in Canada. Biol. Invasions 2006, 8, 45–59. [CrossRef]

- Tataridas, A.; Jabran, K.; Kanatas, P.; Oliveira, R.S.; Freitas, H.; Travlos, I. Early Detection, Herbicide Resistance Screening, and Integrated Management of Invasive Plant Species: A Review. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 3957–3972. [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, P.; Richardson, D.M. Invasive Species, Environmental Change and Management, and Health. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-033009-095548 2010, 35, 25–55. [CrossRef]

- Germán, H.C.; Montesbravo, E.P.; Paredes Rodríguez, E.; Calas, P.B. Biologia Reproductiva de Dichrostachys Cinerea (L.) Wight & Arn. (Marabú). (I) Evaluación de Reproduccion Por Semillas. FITOSANIDAD 2008, 12, 39–43.

- Hernandez-Enriquez, O.; Alvarez, R.; Morelli, F.; Bastida, F.; Camacho, D.; Menendez, J. Low-Impact Chemical Weed Control Techniques in UNESCO World Heritage Sites of Cuba. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2012, 77, 387–393.

- Sinoga, J.D.R.; Noa, R.R.; Perez, D.F. An Analysis of the Spatial Colonization of Scrubland Intrusive Species in the Itabo and Guanabo Watershed, Cuba. Remote Sens. 2010, 2, 740–757. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, E.; Zabalo, A.; Gonzalez, E.; Alvarez, R.; Jimenez, V.M.; Menendez, J. Affordable Use of Satellite Imagery in Agriculture and Development Projects: Assessing the Spatial Distribution of Invasive Weeds in the UNESCO-Protected Areas of Cuba. Agric. 2021, Vol. 11, Page 1057 2021, 11, 1057. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Sha, Z.; Yu, M. Remote Sensing Imagery in Vegetation Mapping: A Review. J. Plant Ecol. 2008, 1, 9–23. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Jin, Y.; Brown, P. Automatic Mapping of Planting Year for Tree Crops with Landsat Satellite Time Series Stacks. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 151, 176–188. [CrossRef]

- Abburu, S.; Babu Golla, S. Satellite Image Classification Methods and Techniques: A Review. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2015, 119, 20–25. [CrossRef]

- Paul M. Mather, M.K. Computer Processing of Remotely-Sensed Images: An Introduction; 2011;

- Chen, B.; Tu, Y.; Song, Y.; Theobald, D.M.; Zhang, T.; Ren, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Mapping Essential Urban Land Use Categories with Open Big Data: Results for Five Metropolitan Areas in the United States of America. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 178, 203–218. [CrossRef]

- Hasmadi, I. Evaluating Supervised and Unsupervised Techniques for Land Cover Mapping Using Remote Sensing Data. Malaysia nJournal Soc. Sp. 2009, 5, 1–10.

- Müllerová, J.; Brundu, G.; Große-Stoltenberg, A.; Kattenborn, T.; Richardson, D.M.; Müllerová, J.; Brundu, G.; Große-Stoltenberg, A.; Kattenborn, T.; Richardson, D.M. Pattern to Process, Research to Practice: Remote Sensing of Plant Invasions. Biol. Invasions 2023 2512 2023, 25, 3651–3676. [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.S.; Terrill, T.H.; Mahapatra, A.K.; Kelly, B.; Morgan, E.R.; Wyk, J.A. van Site-Specific Forage Management of Sericea Lespedeza: Geospatial Technology-Based Forage Quality and Yield Enhancement Model Development. Agric. 2020, Vol. 10, Page 419 2020, 10, 419. [CrossRef]

- Wiens, J.A. Spatial Scaling in Ecology. Funct. Ecol. 1989, 3, 385. [CrossRef]

- Blaschke, T.; Hay, G.J.; Kelly, M.; Lang, S.; Hofmann, P.; Addink, E.; Queiroz Feitosa, R.; van der Meer, F.; van der Werff, H.; van Coillie, F.; et al. Geographic Object-Based Image Analysis - Towards a New Paradigm. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 87, 180–191. [CrossRef]

- Valjarević, A.; Milanović, M.; Valjarević, D.; Basarin, B.; Gribb, W.; Lukić, T. Geographical Information Systems and Remote Sensing Methods in the Estimation of Potential Dew Volume and Its Utilization in the United Arab Emirates. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021 1415 2021, 14, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.L. Comparison of Multi-Seasonal Landsat 8, Sentinel-2 and Hyperspectral Images for Mapping Forest Alliances in Northern California. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 159, 26–40. [CrossRef]

- Oreti, L.; Giuliarelli, D.; Tomao, A.; Barbati, A. Object Oriented Classification for Mapping Mixed and Pure Forest Stands Using Very-High Resolution Imagery. Remote Sens. 2021, Vol. 13, Page 2508 2021, 13, 2508. [CrossRef]

- Escambray Newspaper Available online: https://www.escambray.cu/especiales/valle/.

- Escambray Newspaper Available online: https://www.escambray.cu/2013/metamorfosis-del-valle-de-san-luis-en-trinidad/.

- GADM Available online: https://gadm.org/ (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Datasets Available online: https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/LANDSAT_LC08_C01_T1_SR.

- Zhu, Z.; Woodcock, C.E. Object-Based Cloud and Cloud Shadow Detection in Landsat Imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 118, 83–94. [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, A.P.; Dyson, K.; Bhandari, B.; Saah, D.; Clinton, N. Fitting Functions to Time Series. Cloud-Based Remote Sens. with Google Earth Engine 2024, 331–351. [CrossRef]

- Carreño-Conde, F.; Sipols, A.E.; Simón, C.; Mostaza-Colado, D. A Forecast Model Applied to Monitor Crops Dynamics Using Vegetation Indices (NDVI). Appl. Sci. 2021, Vol. 11, Page 1859 2021, 11, 1859. [CrossRef]

- Berveglieri, A.; Imai, N.N.; Christovam, L.E.; Galo, M.L.B.T.; Tommaselli, A.M.G.; Honkavaara, E. Analysis of Trends and Changes in the Successional Trajectories of Tropical Forest Using the Landsat NDVI Time Series. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2021, 24, 100622. [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.X.; Tan, Y.M.; Wu, P. THE SPATIAL AND TEMPORAL AVAILABILITY DIFFERENCES OF CLOUD-FREE LANDSAT IMAGES OVER THREE GORGES RESERVOIR AREA. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-3-W9, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jia, M.; Zhang, R.; Ren, Y.; Wen, X. Incorporating the Plant Phenological Trajectory into Mangrove Species Mapping with Dense Time Series Sentinel-2 Imagery and the Google Earth Engine Platform. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Datta, P.; Frey, J.; Koch, B. Mapping an Invasive Plant Spartina Alterniflora by Combining an Ensemble One-Class Classification Algorithm with a Phenological NDVI Time-Series Analysis Approach in Middle Coast of Jiangsu, China. Remote Sens. 2020, Vol. 12, Page 4010 2020, 12, 4010. [CrossRef]

- Boscutti, F.; Sigura, M.; De Simone, S.; Marini, L. Exotic Plant Invasion in Agricultural Landscapes: A Matter of Dispersal Mode and Disturbance Intensity. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2018, 21, 250–257. [CrossRef]

- Paini, D.R.; Sheppard, A.W.; Cook, D.C.; De Barro, P.J.; Worner, S.P.; Thomas, M.B. Global Threat to Agriculture from Invasive Species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, 7575–7579. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Zuniga, R.; Morrison, D. Update on the Environmental and Economic Costs Associated with Alien-Invasive Species in the United States. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 52, 273–288. [CrossRef]

- Labonté, J.; Drolet, G.; Sylvain, J.D.; Thiffault, N.; Hébert, F.; Girard, F. Phenology-Based Mapping of an Alien Invasive Species Using Time Series of Multispectral Satellite Data: A Case-Study with Glossy Buckthorn in Québec, Canada. Remote Sens. 2020, Vol. 12, Page 922 2020, 12, 922. [CrossRef]

- César De Sá, N.; Carvalho, S.; Castro, P.; Marchante, E.; Marchante, H. Using Landsat Time Series to Understand How Management and Disturbances Influence the Expansion of an Invasive Tree. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2017, 10, 3243–3253. [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, P.H.; Stohlgren, T.J.; Morisette, J.T.; Kumar, S. Mapping Invasive Tamarisk (Tamarix): A Comparison of Single-Scene and Time-Series Analyses of Remotely Sensed Data. Remote Sens. 2009, Vol. 1, Pages 519-533 2009, 1, 519–533. [CrossRef]

| Parcel number | UTM coordinate (m) WGS_1984_17_N |

Area (m2) | Vegetation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | X: 604902 Y: 2413342 | 1800 | Sugarcane |

| 2 | X: 605243 Y: 2413431 | 900 | Cassava |

| 3 | X: 605129 Y: 2413855 | 1350 | Pasture, aroma and marabou |

| 4 | X: 604902 Y: 2413342 | 1800 | Sugarcane |

| 5 | X: 606551 Y: 2413952 | 5100 | Banana |

| 6 | X: 606354 Y: 2413808 | 3500 | Sugarcane |

| 7 | X: 615644 Y: 2418961 | 2100 | Sugarcane |

| 8 | X: 616699 Y: 2419043 | 15600 | Banana |

| 9 | X: 616812 Y: 2418537 | 39000 | Banana |

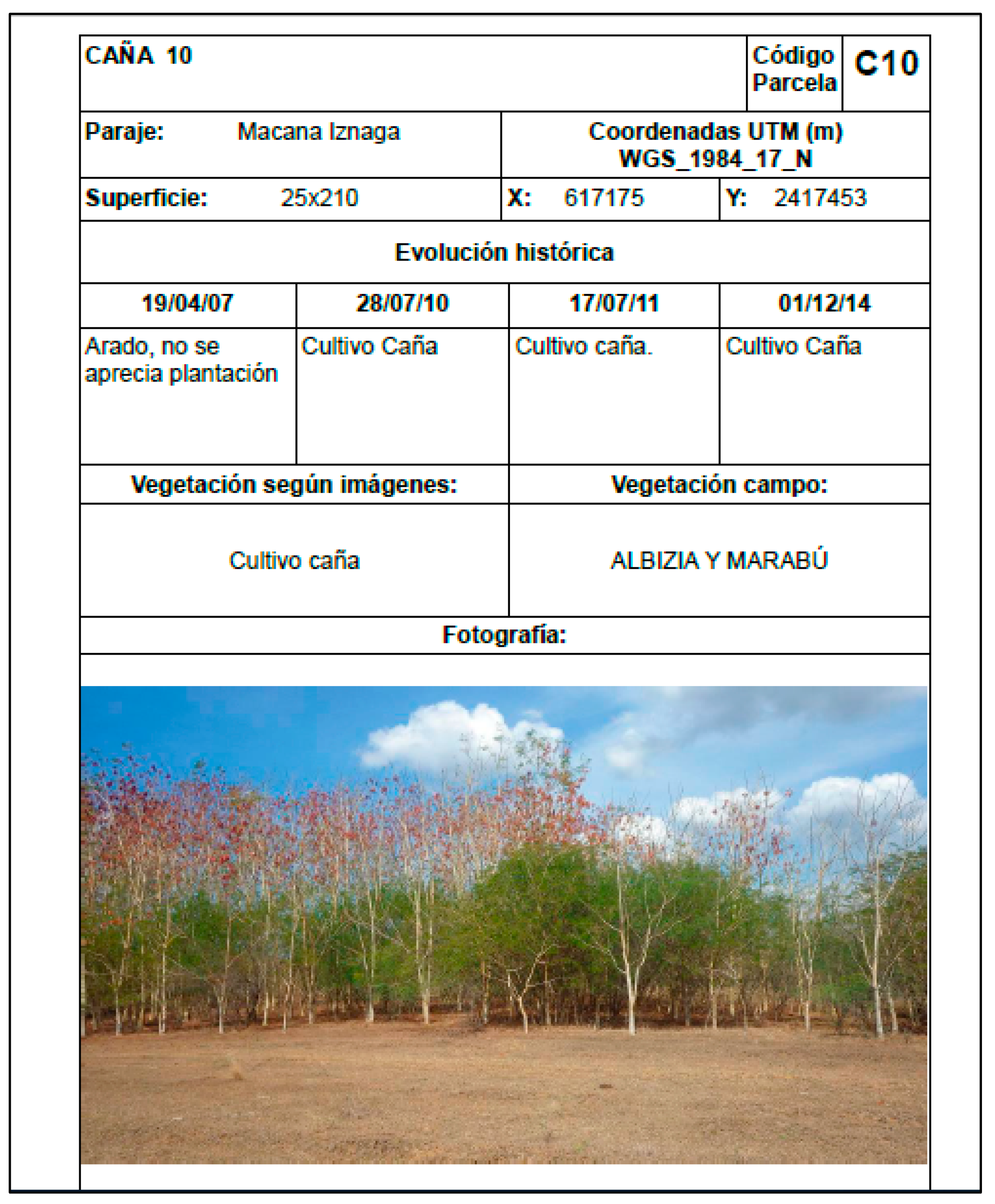

| 10 | X: 617175 Y: 2417453 | 5250 | Albizia and marabou |

| 11 | X: 615644 Y: 2418961 | 2100 | Guava and mango |

| 12 | X: 615581 Y: 2417194 | 7200 | King grass |

| 13 | X: 614521 Y: 2414653 | 10000 | King grass |

| 14 | X: 615151 Y: 2413776 | 62700 | Marabou, albizia, guaban, guarana |

| 15 | X: 614123 Y: 2416299 | 43700 | Marabou, aroma |

| 16 | X: 614911 Y: 2414276 | 22200 | Marabou, aroma |

| 17 | X: 615137 Y: 2414448 | 10500 | Marabou, aroma |

| 18 | X: 608456 Y: 2415134 | 28000 | Marabou, aroma |

| 19 | X: 608207 Y: 2414556 | 24000 | Eucalyptus |

| 20 | X: 611645 Y: 2415412 | 85800 | Marabou, albizia, aroma |

| 21 | X: 610162 Y: 2415228 | 18000 | Marabou, guin de bandera |

| 22 | X: 607502 Y: 2414784 | 36975 | Marabou |

| 23 | X: 607502 Y: 2413310 | 24000 | Marabou and riparian species |

| 24 | X: 614138 Y: 2414879 | 13500 | Marabou, guacima |

| 25 | X: 614143 Y: 2414625 | 12600 | Marabou, aroma |

| 26 | X: 613737 Y: 2415050 | 56700 | Marabou |

| 27 | X: 607813 Y: 2415031 | 9000 | Riparian vegetation with some marabou along the edges |

| 28 | X: 607833 Y: 2413688 | 18000 | Marabou, aroma, guarana,palma |

| 29 | X: 606533 Y: 2412695 | 2750 | Palm, almacigo, yagruma and guacima |

| Class | Mar | Pal | Rib | Cane | King | Urb | Water | Mang | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mar | 56 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 57 |

| Pal | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Rib | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Cane | 0 | 0 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 19 |

| King | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Urb | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 0 | 2 | 36 |

| Water | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Mang | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Sum | 57 | 10 | 3 | 17 | 5 | 34 | 4 | 6 | 136 |

| Year | Hectares |

|---|---|

| 2002 | 7908.1 |

| 2004 | 5067.5 |

| 2006 | 14376.8 |

| 2008 | 14132.2 |

| 2010 | 12326.2 |

| 2012 | 12945.2 |

| 2014 | 12670.7 |

| 2015 | 12796.1 |

| 2016 | 10330.2 |

| 2017 | 8772.5 |

| 2018 | 9329.7 |

| 2019 | 12675.0 |

| 2020 | 15657.0 |

| 2021 | 15640.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).