Introduction

In this paper, I have depicted a visual and geometric proof of the Four Color Map Theorem and K5 non-planarity, and shown how both theorems are connected. They fundamentally represent the same constraint — a geometric limitation that arises from circle interactions in the plane.

This novel approach sheds new light on these mathematical problems, making them more accessible and intuitive. We demonstrate that their common ground lies in the kissing number in two dimensions, a classical geometric limit stating that no more than four equal-sized circles can be simultaneously tangent to a given circle in ℝ2.

We build upon the Koebe–Andreev–Thurston Circle Packing Theorem, which states that every planar graph can be represented as a circle packing — a configuration where vertices map to circles and adjacencies map to tangencies. This bridges graph theory with geometry directly.

Furthermore, by invoking Wagner’s Theorem, we connect high chromatic number claims with the necessity of a K5 minor — which we then demonstrate cannot exist in planar circle packings due to the kissing number constraint.

We also acknowledge Descartes’ Circle Theorem, used in the appendix, to illustrate precise mutual tangency configurations among four circles — reinforcing the geometric feasibility of K4 but impossibility of K5.

Methods

Our method uses geometric representations of graphs, specifically mapping each vertex to a circle in 2D space, and each edge to a tangency between circles.

By applying the Koebe–Andreev–Thurston Circle Packing Theorem, we ensure that any planar graph can be visualized as a collection of tangent circles. This forms the geometric stage for analyzing chromatic bounds.

- 2.

Tangency and Chromatic Bound via Kissing Number

The kissing number in ℝ2 establishes that at most four circles can be mutually tangent — directly limiting the possible degrees of adjacency in a planar embedding. This acts as a hard upper bound on the chromatic number of any planar graph.

- 3.

Obstruction from K5 via Wagner’s Theorem

We utilize Wagner’s Theorem to justify that any planar graph requiring more than four colors must contain a K5 minor. We then show such a K5 cannot be embedded due to the tangency limitation from the kissing number.

- 4.

Validation through Descartes’ Circle Theorem

In the appendix, we show that for three mutually tangent circles, exactly two more circles (inner and outer Soddy circles) can be constructed. This precisely models K4 but mathematically excludes a configuration equivalent to K5.

Results

From our constructions and proofs, we derive:

Any planar graph G has chromatic number χ(G) ≤ 4, by showing that a 5-chromatic configuration requires 5 mutually tangent circles, violating the 2D kissing number.

K5 cannot be embedded in ℝ2 using mutually tangent circles due to geometric infeasibility, and it also violates Euler’s formula for planar graphs.

χ(G) ≤ maximum kissing number in circle packing P

⇒ χ(G) ≤ 4

These results are obtained by synthesizing graph minor theory (Wagner’s Theorem), circle packing (Koebe–Andreev–Thurston), and geometric tangency limits (kissing number and Descartes’ Theorem).

Discussion

This work reframes two of graph theory’s most well-known results — the Four Color Theorem and K5 non-planarity — not as separate facts but as manifestations of a common geometric limitation.

Our main insight is that the 2D kissing number implicitly governs the allowable structure of planar graphs. While classical approaches focus on colorings and embeddings, our model visually and mathematically shows why you can’t exceed four mutually adjacent regions: five mutually tangent circles simply don’t fit in the plane.

Using the Koebe–Andreev–Thurston theorem, we transformed abstract graph problems into visual geometry. Using Wagner’s Theorem, we tied chromatic number to forbidden minors. And with Descartes’ Circle Theorem, we grounded K4 as the maximal mutually tangent structure in 2D.

This makes the entire framework not only non-computational, but also teachable, intuitive, and provably minimal.

Key Theorem: Descartes’ Circle Theorem (1643)

Given three mutually tangent circles (with curvatures ), there are exactly two possible fourth circles that can be tangent to all three:

Given three mutually tangent circles with curvatures

, there are exactly two possible fourth circles that can be tangent to all three:

This result confirms that for any trio of mutually tangent circles, only two distinct fourth circles can satisfy full tangency — a fact elegantly visualized by the “inner gap method” and the “outer encasing method” in our K4 constructions.

** The geometric representation introduced in this paper aligns with the principles of circle packing. Each vertex as a circle, and each edge as a tangent, mirrors the circle packing representations used in the proof of the Circle Packing Theorem. The Koebe–Andreev–Thurston Circle Packing Theorem asserts that every planar graph can be represented as a packing of circles in the plane, where tangents between circles correspond to graph edges. This further supports the equivalence of geometric representations and combinatorial colorability.

Historically, Paul Koebe introduced the foundational result in 1936. Later, William Thurston in the 1980s revived and extended the implications of this theorem, connecting it to conformal mappings and the Four Color Theorem itself. Thus, this paper’s visual model is naturally grounded in circle packing theory.

Connection to Circle Packing : The geometric representation introduced in this paper aligns with the principles of circle packing. Each vertex as a circle, and each edge as a tangent, mirrors the circle packing representations used in the proof of the Circle Packing Theorem. The Koebe–Andreev–Thurston Circle Packing Theorem asserts that every planar graph can be represented as a packing of circles in the plane, where tangents between circles correspond to graph edges. This further supports the equivalence of geometric representations and combinatorial colorability.

Historically, Paul Koebe introduced the foundational result in 1936. Later, William Thurston in the 1980s revived and extended the implications of this theorem, connecting it to conformal mappings and the Four Color Theorem itself. Thus, this paper’s visual model is naturally grounded in circle packing theory.

● N1(Represents C1 as circle)

If we represent it as circle:

- 2.

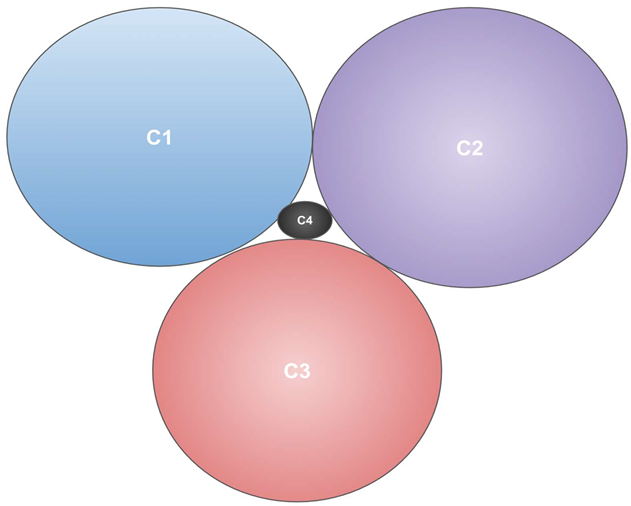

Two Vertex isolated N1 and N2:

● ●(N1 and N2 represent C1 and C2)

If we represent it as circle:

2.1. Two Vertices Adjacent to Each Other K2(One Tangent)

N1

N2

If we represent it as circle(N1 as C1 and N2 as C2):

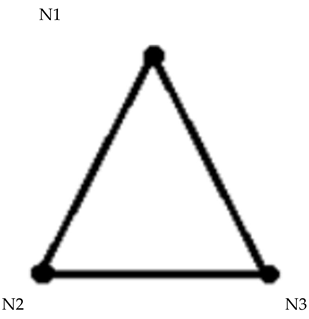

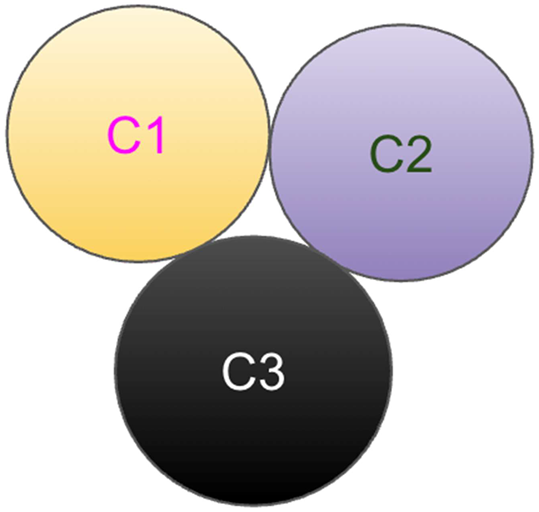

3.1. Three Vertices Adjacent to Each Other K3

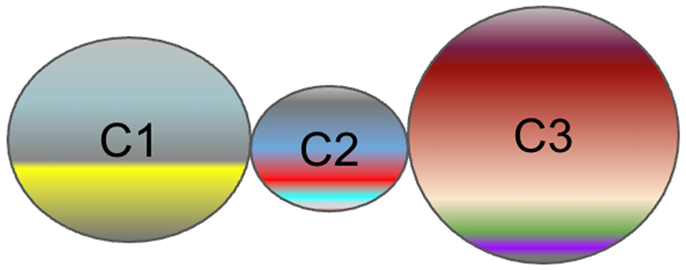

If we represent it as circle(N1 as C1, N2 as C2 and N3 as C3, three tangents):

3.2. Also Another Variety of 3 Vertices Where Only Middle Vertex Connect Two Other Two Vertices

If we represent it as circle(two tangents):

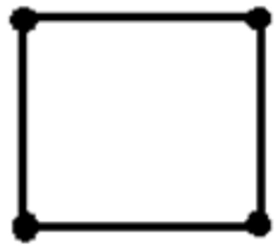

4.1. Four Vertices in a Simple Rectangular Arrangement

If we represent it as circle:

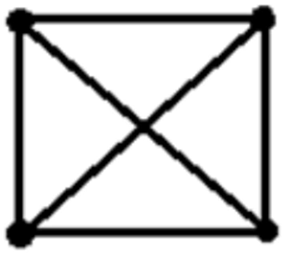

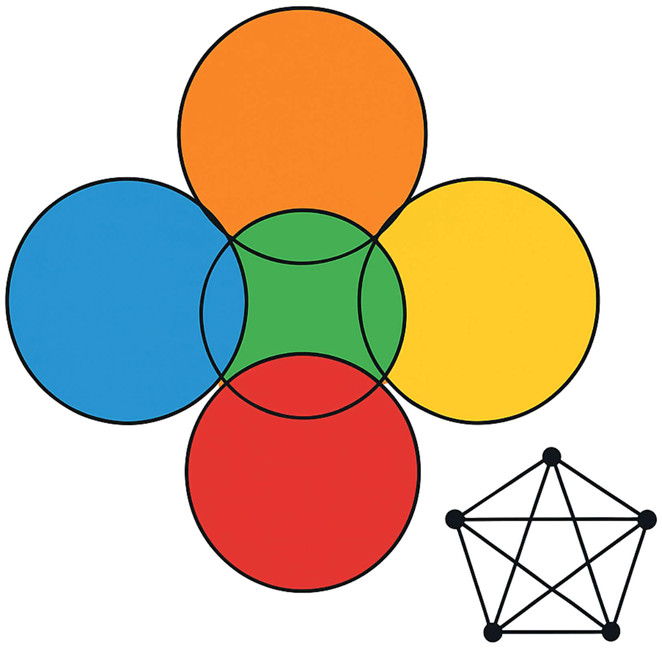

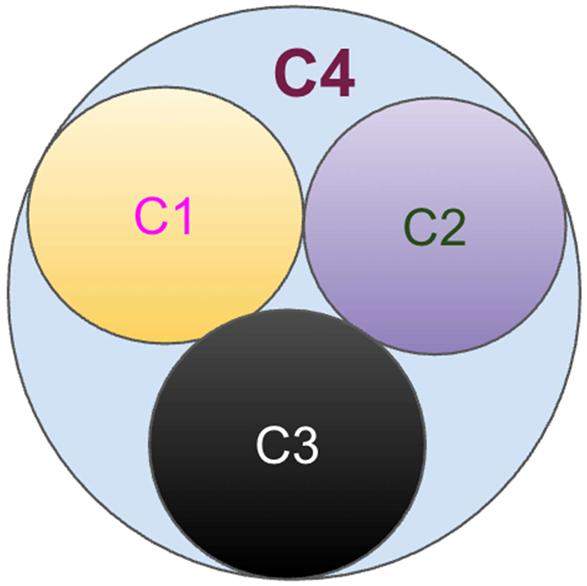

4.2. Four Vertices in K4 Rectangular Arrangement

If we represent it as circle:

OR

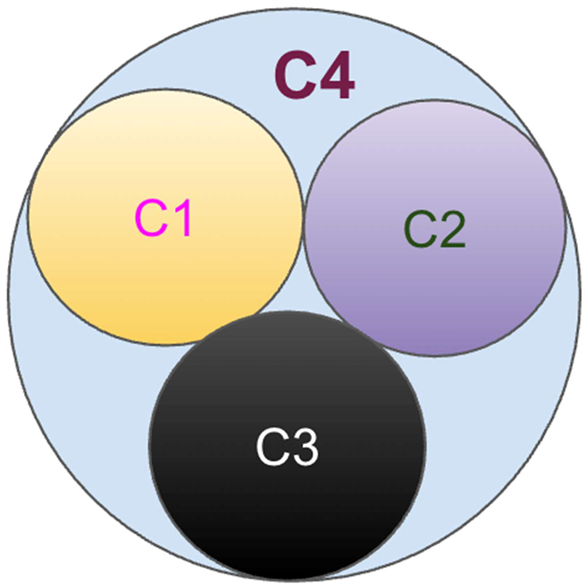

Four Vertices in K4 Rectangular Arrangement: If we represent it as circles:

We can construct K4 circle-packed in two valid geometric styles:

Inner Circle Gap Method: Start with three mutually tangent circles forming a triangle, and place the fourth smaller circle in the gap — this circle will be tangent to all three others. This demonstrates a compact form of K4 realization in 2D.

Outer Encasing Method: Place three mutually tangent circles in contact, and use a larger circle to enclose and touch all three — the outer circle acts as the fourth vertex. This layout maintains the K4 adjacency through tangency from one outer circle.

(Refer to figure showing both these styles visually. These forms emphasize the flexibility of circle packing to realize full mutual adjacency of four vertices — i.e., K4.)

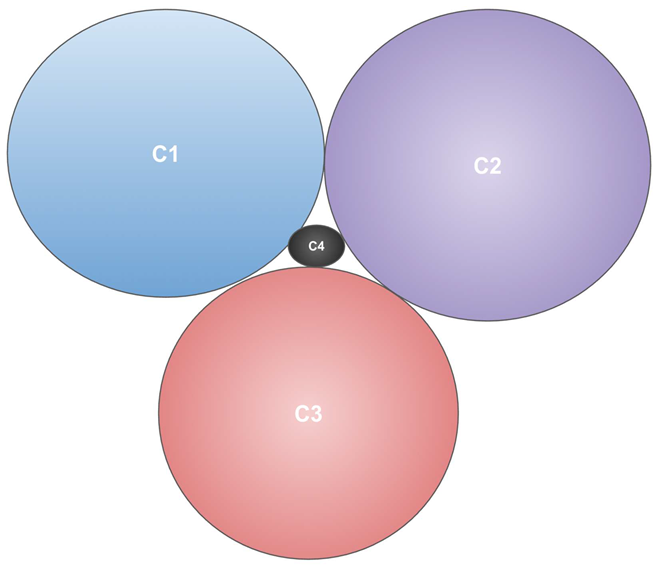

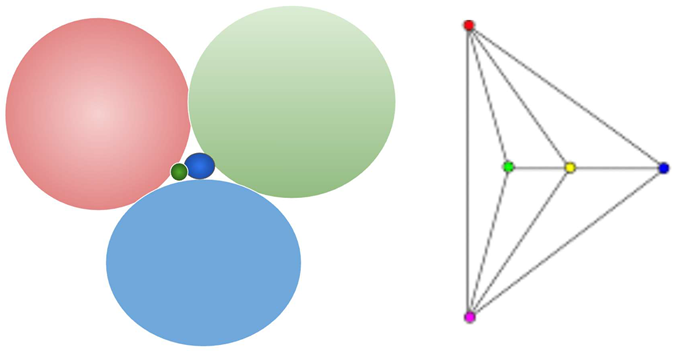

5.1. Five Vertices in K5

Upon closer examination, we observe that it is impossible to arrange five circles in the same plane in such a way that they all touch each other simultaneously. This fundamental insight serves as a crucial foundation for our proof, leveraging a well-established geometric property governing the interactions of multiple circles.

Background:

The Four Color Theorem has been a fundamental problem in graph theory for over a century. It posits that any planar graph can be colored with no more than four colors such that no two adjacent regions share the same color.

The Four Color Theorem in This Context

The theorem states that no more than four colors (or planes, in your interpretation) are needed to ensure that no two adjacent circles (vertices) share the same color (or are on the same plane).

Lemma: Kissing Number in 2D Plane

In a 2D plane, the maximum number of equal-sized circles that can touch another circle without any of them overlapping is 4. The four color map theorem is deeply connected with this geometrical nature of interaction of circles or any closed graphs in a 2d plane.

Lemma (Chromatic-Kissing Bound)

Let G be a planar graph with a circle packing P, where each vertex v ∈ V(G) is represented by a circle Cᵥ, and edges correspond to tangencies. Then:

χ(G) ≤ maximum kissing number of P ≤ 4

Theorem 1 (Four Color Theorem via Circle Packing)

Let G = (V, E) be a planar graph. Then its chromatic number satisfies:

χ(G) ≤ 4

Proof:

Assume, for contradiction, that there exists a planar graph G with:

χ(G) ≥ 5

Graph Minor Implication

By Wagner’s Theorem, since χ(G) ≥ 5, G must contain K5 as a minor:

K5⪯G

Circle Packing Representation

By the Koebe–Andreev–Thurston Theorem, G admits a circle packing P in ℝ2 where:

Each edge (vᵢ, vⱼ) ∈ E implies Cᵢ and Cⱼ are tangent

This extends to minors, so the K5 minor corresponds to 5 circles {C₁, C₂, C₃, C4, C5}.

Tangency Requirement for K5

Because K5 is complete, in P:

For all i ≠ j, Cᵢ ∩ Cⱼ ≠ ∅ (i.e., they must be tangent)

⇒ Each Cᵢ must be tangent to 4 others

Kissing Number Contradiction

The maximum number of mutually tangent circles in ℝ2 is 4 (kissing number k₂ = 4).

Thus:

There does not exist a configuration where every circle Cᵢ is tangent to four others.

This contradicts the K5 packing requirement.

∴ The assumption χ(G) ≥ 5 is false, and

χ(G) ≤ 4 □

Corollary 1 (Non-Planarity of K5)

The complete graph K5 is non-planar.

Proof:

Combinatorial Argument:

For K5 (|V| = 5, |E| = 10):

|E| = 10 > 9 = 3|V| − 6 (violates Euler’s formula for planar graphs)

Geometric Argument:

A planar K5 would require a circle packing with 5 mutually tangent circles, but:

k₂ = 4⇒No such packing exists.

∴ K5 is non-planar. ■

∴ K5 is non-planar both geometrically and topologically.

Theorem (4CT and K5 Non-Planarity as the Same Problem)

The Four Color Theorem and the non-planarity of K5 are dual consequences of the same geometric limitation:

“In the 2D Euclidean plane, it is impossible to arrange five mutually tangent circles.”

Topologically: This prevents K5 from being planar (→ non-planarity of K5).

Closing and Conclusion

In this paper, we have explored a fascinating intersection between geometry and graph theory, shedding light on the intriguing concept of the “kissing number” of circles in a 2D plane. We began by introducing the fundamental idea of representing planar graphs using groups of circles, where circles symbolize vertices, and tangents between them represent edges. This visual representation not only simplifies complex graph structures but also offers new insights into long-standing problems.

Our journey led us to the heart of the “kissing number” problem, a classic question in mathematics. We established the essential theorem that in a 2D plane, the maximum number of circles that can touch another circle without overlapping is 4. This simple yet profound result has far-reaching implications in various fields, from geometry to network design.

By providing a lemma and proof, we have contributed to the comprehensive understanding of this intriguing problem. We have clarified that the size of the circles need not be uniform; it is their relative positions and non-overlapping nature that define the kissing

References

- Stephenson, K. (2005). Introduction to Circle Packing: The Theory of Discrete Analytic Functions. Cambridge University Press.

- Conway, J.H.; Sloane, N.J.A. (1999). Sphere Packings, Lattices and Groups. 3rd ed. Springer, New York.

- Wagner, K. Über eine Eigenschaft der ebenen Komplexe. Mathematische Annalen 1937, 114, 570–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soddy, F. The Kiss Precise. Nature 1936, 137, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, K.; Haken, W. Every planar map is four colorable. Part I: Discharging. Illinois Journal of Mathematics 1977, 21, 429–490. [Google Scholar]

- Appel, Kenneth, Wolfgang Haken and Jürgen Koch. “Every planar map is four colorable. Part II: Reducibility.”. Illinois Journal of Mathematics 1977, 21, 491–567.

- Heawood, P.J. Map-Colour Theorem. Quarterly Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics 1890, 24, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempe, A.B. On the Geographical Problem of the Four Colours. American Journal of Mathematics 1879, 2, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutte, W.T. The dissection of equilateral triangles into equilateral triangles. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 1946, s3-47, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, H. Congruent graphs and the connectivity of graphs. American Journal of Mathematics 1932, 54, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, E.M. Convex polyhedra in Lobachevsky space. Matematicheskii Sbornik 1970, 81, 445–478. [Google Scholar]

- Thurston, W.P. (1985). The finite Riemann mapping theorem. Invited talk, International Symposium at Purdue University.

- Gonthier, G. Formal Proof—The Four-Color Theorem. Notices of the American Mathematical Society 2008, 55, 1382–1393. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch, R.; Fritsch, G. (1998). The Four-Color Theorem: History, Topological Foundations, and Idea of Proof. Springer-Verlag.

- Ringel, G.; Youngs, J.W.T. Solution of the Heawood Map-Coloring Problem. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1968, 60, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, N.; Sanders, D.P.; Seymour, P.D.; Thomas, R. The Four-Colour Theorem. Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 1997, 70, 2–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

N2

N2