1. Introduction

The definitive diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernias can be challenging. Positive contrast peritoneography can assist in identifying ambiguous cases. This paper reports an instance of an injured cat where this method serendipitously revealed an unexpected and rare presentation of a congenital diaphragmatic defect: a “true diaphragmatic hernia” also called “pleuroperitoneal hernia”. Other accounts of this uncommon congenital malformation in cats are reviewed.

2. Case Presentation

A one-and-a-half-year-old neutered male domestic shorthair cat was presented to the emergency department of our institution after falling from the second floor (five meters), which occurred 5 hours earlier. There were no medical incidents, including trauma, reported prior to this event.

2.1. Physical Examination

On admission, the cat weighed 5.7 kg, had a body condition score of 6/9, a rectal temperature of 38.2°C, a heart rate of 176 beats per minute, and exhibited tachypnea with 44 respirations per minute. The femoral pulse was strong and synchronous with the precordial activity. The oral mucous membranes were pink and moist, and capillary refill time was less than two seconds. A right sublingual ranula was observed, along with a degloving injury on the third and fourth digits of the right hind limb, confirming the occurrence of trauma.

2.2. Additional Tests

A routine trauma assessment was carried out including blood tests (hematocrit, proteinemia, glycemia, uremia, creatininemia, lactatemia, blood gases, ionogram) which all were within the usual values. A blood pressure measurement revealed slight hypertension (156 mm Hg) attributed to stress or pain.

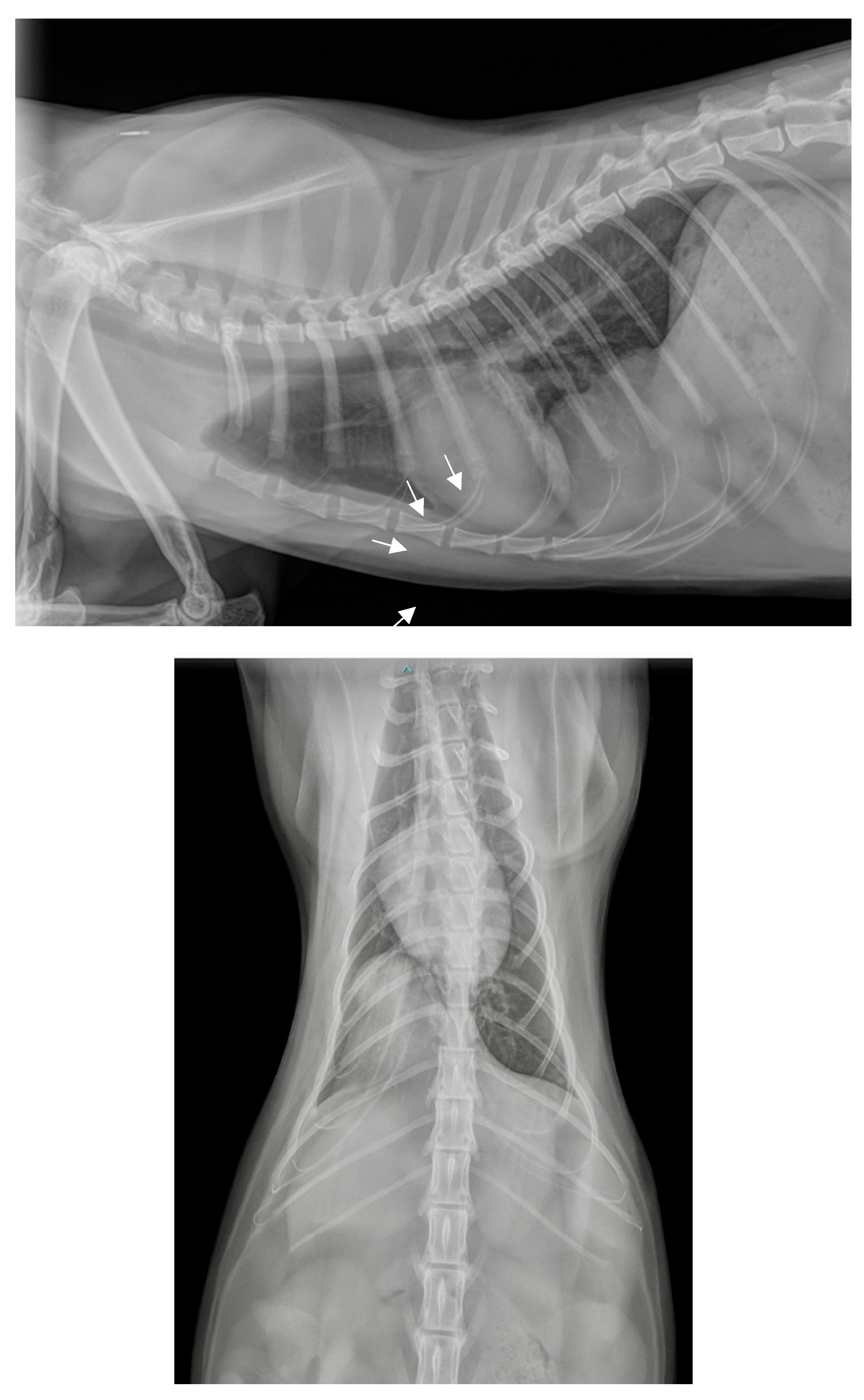

Plain chest radiographs identified a large mass (4 cm x 4 cm), well circumscribed, homogeneous, with a density similar to soft tissue, located in the usual projection area of the thorax, caudally and ventrally on the lateral projection, medially and just right to the spine on the dorsoventral projection, in contact with the sternum, the diaphragm and the apex of the heart, ventrally to the caudal vena cava (

Figure 1a,b). The rest of the thoracic cavity appeared unremarkable.

This finding, in the context of a fall from the second floor, raised the possibility of the liver or other abdominal organs being implicated in a traumatic diaphragmatic rupture; however, the mass was notably circumscribed. The differential diagnosis included an incidentally discovered mass (granuloma, hematoma, abscess, cyst, neoplasia), a longstanding traumatic diaphragmatic hernia, or a congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

Among congenital diaphragmatic hernias, the very ventral location excluded a hiatal hernia; on both lateral and frontal radiographs, the mass did not appear to be in continuity with the pericardial sac: the contours of the heart were clearly observable and the edges of the pericardial sac were clearly separated from this mass, which did not support the diagnosis of a peritoneopericardial hernia; a pleuroperitoneal hernia was deemed the most likely diagnosis.

An abdominal and thoracic ultrasound exam failed to definitively confirm the presence of a diaphragmatic tear and to determine the mass's composition.

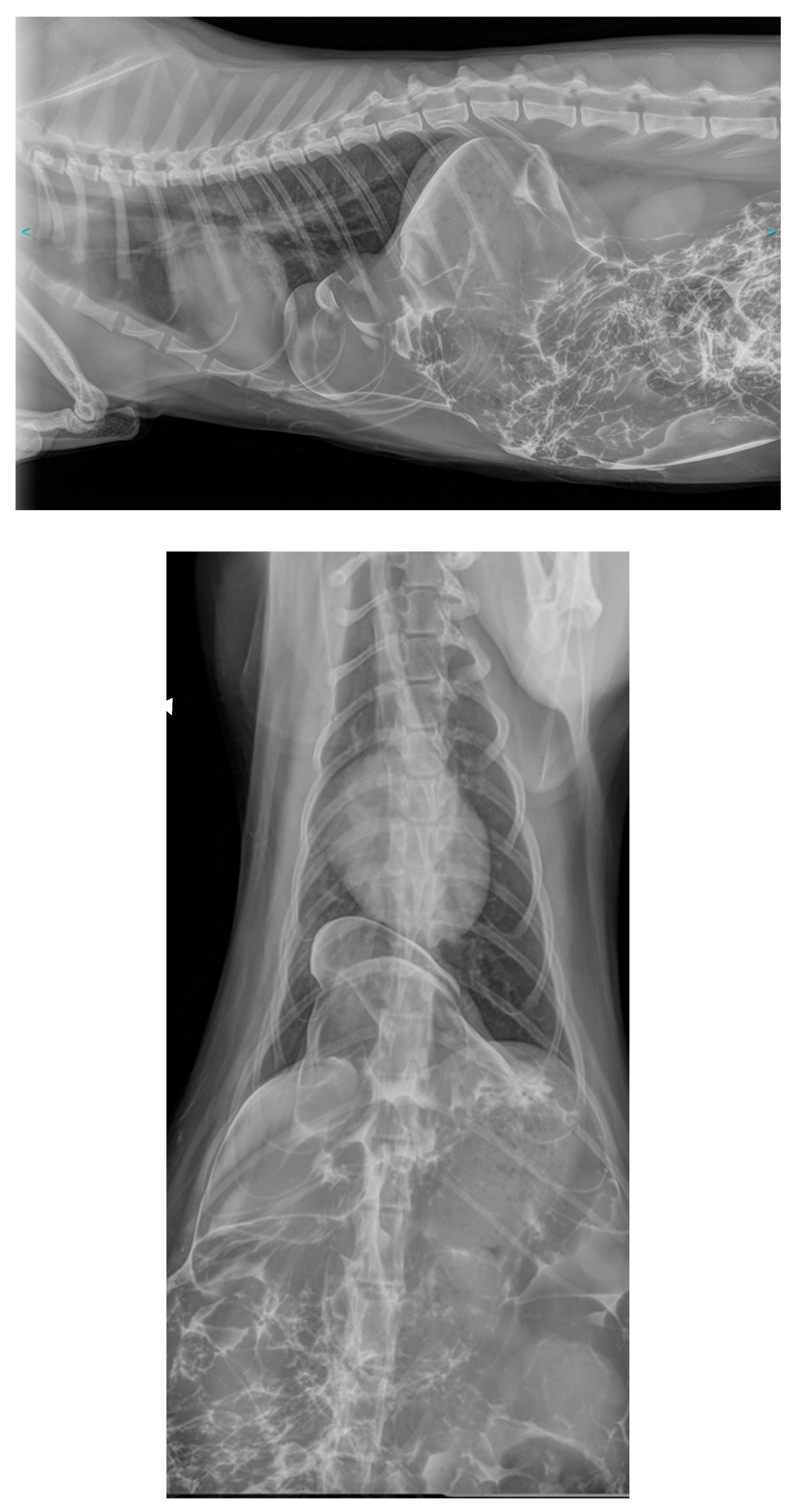

Subsequently, a positive contrast peritoneography was carried out by injecting transabdominally, on the linea alba, 2 ml/kg of an iodine derivative, iopamidol, Iopamiron

®, at a concentration of 300 mg/ml, at room temperature and then placing the animal in sternal recumbency with the pelvis elevated (

Figure 2a,b).

The contrast medium distributed well throughout the peritoneal cavity and was also observed in the usual thoracic projection area. However, it did not diffuse throughout the entire thoracic cavity; rather, it appeared to be contained by a membrane or by the deformed diaphragmatic muscle. The contrast product having been injected into the abdominal cavity and found at the location of the abnormal structure identified on the plain radiographs, it was now proven that this structure was of abdominal origin. Given the location, it could have been a part of a hepatic lobe, the falciform ligament, the omentum, the intestine, the stomach, the pancreas or the spleen.

2.3. Diagnosis

These findings led to the diagnosis of a diaphragmatic hernia. The very circumscribed nature of the hernia, and particularly the fact that the contrast medium did not disperse throughout the entire thoracic cavity, suggested a specific type of congenital diaphragmatic hernia known as “pleuroperitoneal hernia” or “true diaphragmatic hernia”, in which the involved organs are enclosed within a hernial sac. The hypothesis of a peritoneopericardial hernia was ruled out because, in such a case, the contrast medium would have spread into the pericardial sac. Similarly, had there been a diaphragmatic tear, the contrast medium would have disseminated throughout the pleural cavity. This case was deemed an incidental discovery of a congenital anomaly predating the traumatic event.

2.4. Treatment

Although the cat did not present any dyspnea, surgical intervention was conducted to prevent the involvement of additional organs, organ strangulation, and the onset of breathing difficulties.

A midline laparotomy extending from the xiphoid process to the umbilicus did not reveal any muscular damage or bleeding that would indicate trauma at this location. The laparotomy enabled the visualization of a 3 cm radial defect in the diaphragm, located in the right ventral quadrant of the pars sternalis. The diaphragm's edges were rounded, which implied that the defect was longstanding in nature. These findings supported the diagnosis of a congenital rather than a recent traumatic origin for the diaphragmatic breach.

A part of the falciform ligament and a part of the omentum were engaged in the diaphragmatic defect. The organs involved were encapsulated within a hernial sac composed of a serous membrane. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of a pleuroperitoneal hernia and accounted for the abnormal tissue density seen in the thoracic radiographs. Once the hernia was reduced, the herniated tissues were found to be unharmed. Due to the presence of a hernial sac, there was no open chest phase: the cat breathed spontaneously and normally throughout the surgery.

Herniorrhaphy was performed using a simple continuous closure with absorbable braided suture (Vicryl 3-0) without prior reviving of the edges of the diaphragm. The hernial sac was not removed to avoid open chest surgery and pneumothorax. At the end of the procedure, transdiaphragmatic aspiration made it possible to collect several milliliters of air, probably introduced through the perforation sites of the diaphragm by the suture needle. It was not considered necessary to place a chest tube.

2.5. Evolution

There were no intraoperative or postoperative complications. Immediate postoperative radiographs confirmed hernia reduction and showed the persistence of a mild pneumothorax (

Figure 3a,b). The hernial sac, which was not removed, was clearly visible on the lateral view (white arrows), it contained a small amount of air. The contrast medium was drained by the parietal and visceral peritoneum, then eliminated by the kidneys, it was subsequently visible in the bladder.

The cat fully recovered and was discharged the day following surgery.

3. Discussion

3.1. The Different Types of Diaphragmatic Hernias in Cats

Diaphragmatic hernias in cats are most often the result of trauma. These “classic” diaphragmatic hernias are not, in the strictest sense, real hernias. Indeed, the definition of a hernia presupposes the existence of a hernial sac. This is the case for umbilical hernias, inguinal hernias, and perineal hernias where the hernial sac is formed by the peritoneum.

A “classic” diaphragmatic hernia is a traumatic rupture of the diaphragm after which the abdominal organs move into the thoracic cavity (which has lower pressure) but are not enclosed in a hernial sac. Therefore, the use of the term “hernia” in this context is technically incorrect; we should rather speak of a diaphragmatic rupture with engagement of the abdominal organs in the thoracic cavity. Similarly, it is not accurate to refer to a traumatic “abdominal hernia” when organs protrude through a breach in the muscular wall of the abdomen and are palpable under the skin: without a hernial sac, strictly speaking, there is no hernia; the term “evisceration” is more appropriate.

Given that traumatic diaphragmatic ruptures are much more common, it is customary to refer to them as “diaphragmatic hernias” and to specify the type of hernia when it does not correspond to this classic form. Alongside these acquired forms, almost all traumatic, there are congenital forms. Congenital diaphragmatic hernias arise from incomplete development of a portion of the diaphragmatic dome.

Among congenital diaphragmatic hernias, there are hernias occurring through the diaphragm's natural openings: the esophageal hiatus and the foramen of the vena cava. Generally, these are not associated with a hernial sac. A few cases of hiatal hernias have been reported in cats [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7] and only two cases of herniations through the foramen of the vena cava have been reported in this species [

8,

9].

Genuine diaphragmatic hernias – that is, with a hernial sac – are congenital. These are “pericardoperitoneal hernias” (the most common in cats) and “pleuroperitoneal hernias”. Although pericardoperitoneal hernia is a true hernia, it is customary to reserve the term “true diaphragmatic hernias” exclusively for pleuroperitoneal hernias, a convention that will be adhered to in the remainder of this article.

3.2. Definition of a “True Diaphragmatic Hernia”

“True diaphragmatic hernias”, also known as “pleuroperitoneal hernias”, arise from a congenital anomaly of the diaphragm, which features an incomplete rupture and persistent serosa membrane on the diaphragm's thoracic side preventing open communication between the thoracic and abdominal cavities. Owing to the lower pressure within the thoracic cavity, abdominal organs may protrude into this space; however, they are encapsulated by this serosa, forming the hernial sac.

3.3. Rarity of True Diaphragmatic Hernias

True diaphragmatic hernias are infrequently documented in the veterinary literature. We have cataloged 12 individual reports in cats [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] and 4 individual reports in dogs [

21,

22,

23]. To our knowledge, no cases have been reported in a case series. Cases may have been reported in textbooks. Major congenital diaphragmatic defects observed in cats [

24,

25] or in young dogs [

26,

27,

28,

29] were not included in this review.

3.4. Location of the Congenital Hernias

In the veterinary literature, the type of true diaphragmatic hernia is not specified by the authors. However, there are different names used in humans depending on the location. Vosges et al. [

11,

15] and Carriou et al. [

11,

15] draw a parallel between the “true diaphragmatic hernia” described in cats and the “Bochdalek hernia” described in humans. Indeed, Bochdalek hernias represent 95% of congenital diaphragmatic hernias in humans, but Bochdalek hernia is a posterolateral hernia [

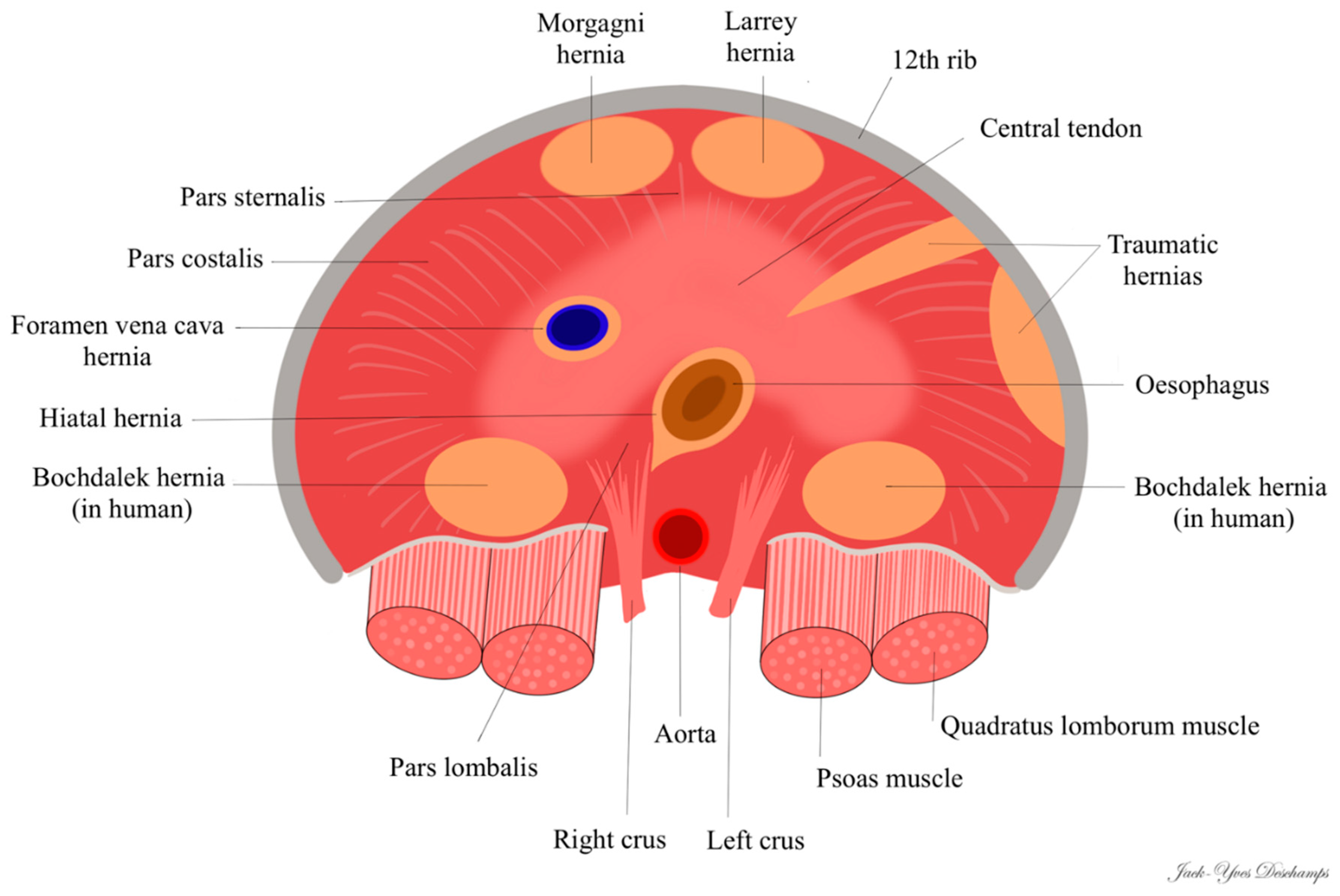

30] whereas the hernias described by these authors were ventral (anterior) .

In humans, there are two types of congenital diaphragmatic hernias linked to incomplete fusion of the diaphragm: hernias located in the posterolateral region, right or left, called “Bochdalek hernias” (first described in 1848 by Vincent Alexander Bochdalek) and hernias located in the anterior and retrosternal region, called “Morgagni hernias” on the right (first described by Giovanni Battista Morgagni in 1769) or “Larrey hernias” on the left (attributed - wrongly - to Dominique Jean Larrey in 1812). Some authors do not distinguish between right and left anterior hernias and describe all anterior congenital hernias as “Morgagni hernia” [

31]; 90% of Morgagni hernias occur on the right side due to the pericardial attachments to the diaphragm that provide protection and support to the left side [

32].

In the current case, the diaphragmatic defect, being radial, ventral, and to the right, corresponds to the right anterolateral hernia found in humans, known as “Morgagni hernia”. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first instance where the term “Morgagni hernia” is employed in veterinary medicine to describe this congenital anomaly. Nevertheless, six cases previously reported in cats [

11,

12,

15,

16,

19,

20] - including the cases by Vosges et al. and Carriou et al. - along with three cases in dogs [

21,

22] appear to be consistent with a Morgagni hernia, as the radiological images are directly comparable to those of the current case.

Only the case described by Green et al. [

13], which reports radiopaque structures ventrally and in the left hemithorax, seems to align with the “Larrey hernia” described in humans. Among the 4 cases of true diaphragmatic hernias reported in dogs, only the case of Devereux et al. [

23] concerns a small discontinuity of the ventral left diaphragm and can therefore be considered as a Larrey hernia.

In the three cases reported by Mann et al. [

10], White et al. [

14], and Rose et al. [

18], the authors note a radiopaque soft-tissue mass in the midportion of the diaphragmatic crus : unlike Morgagni or Larrey hernias, the mass is not ventrally positioned. This location seems to correspond more with a “caval foramen hernia”, even though the first two cases mention the presence of a hernial sac, which is unusual in humans.

The two cases published by Gombač et al. [

17] are necropsy findings that do not provide enough detail to determine the precise location of the hernia.

Thus, all true diaphragmatic hernias in cats are Morgagni hernias in the broad sense, that is, either right or left; as far as we are aware, there have been no reports of hernias in cats that correspond to the Bochdalek hernia seen in humans (posterolateral) (

Figure 4). On the contrary in human, Morgagni hernias, in a general sense, account for only 2 to 5% of congenital diaphragmatic hernias and Bochdalek hernias represent at least 95% of congenital diaphragmatic hernias [

31,

32].

3.5. Serendipitous Discoveries

Most acquired diaphragmatic hernias occur post-trauma, typically due to a road accident or a defenestration. In the present case, a fall from the second floor along with concurrent injuries (ranula and degloving of two digits) suggested a traumatic origin. However, what initially supposed to be a “classic” acquired diaphragmatic hernia was actually a congenital defect that was fortuitously revealed.

The cases reported in veterinary literature are all serendipitous discoveries during the investigation of symptoms not typically associated with diaphragmatic hernias: intermittent diarrhea [

11], hyperthyroidism [

12], cough [

14], acute neurological deterioration [

15], squamous cell carcinoma of the ears [

13], diabetes mellitus [

18], routine health inspection [

19], intermittent vomiting [

20].

In one case, a hernia was discovered while assessing injuries from a recent road traffic accident, yet the cat displayed no respiratory distress [

16]; similar to our report, the hernia was considered unrelated to the recent trauma.

While the anomaly is congenital, nearly all reported cases (10 out of 13) involved adult cats, ranging from 15 months to 14 years old. Only three symptomatic cases were documented in young cats: one by Mann et al. involved an eight-month-old cat presented with respiratory distress [

10], and two by Gombač et al. [

17] regarding closely related British Shorthair cats where both succumbed postoperatively to severe dyspnea; necropsy revealed a thin, flaccid, and distended transparent tendinous portion of the diaphragm protruding cranially into the thoracic cavity, forming a cupola in which the left, right medial, and quadrate hepatic lobes were encased in both cats, and the stomach in one cat.

In human medicine, Morgagni hernias are also often incidental findings [

31,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42].

3.6. Herniated Organs

The organs typically involved include a small portion of the liver in 10 out of 13 cases (77%) [

10,

12,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20], or the falciform ligament in 4 out of 13 cases (30%) [

11,

13,

19], including the current case. In the case documented by Lee et al. [

19], both the liver and the falciform fat were present; in the present report, a part of the falciform ligament and a part of the omentum were involved. In humans, the intrathoracic hernial sac often encompasses the omentum and the falciform ligament [

33].

Given their distinct margins and thoracic location, it's understandable that these hernias are sometimes misidentified as pulmonary masses [

11,

14,

19].

3.7. Positive Contrast Peritoneography

When digestive loops containing air are involved, radiological and ultrasound diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia is typically straightforward. However, when only the liver or a limited number of non-digestive organs are involved (such as the falciform ligament, the omentum or the spleen), diagnosing diaphragmatic hernia can be challenging. Misdiagnosis with pulmonary atelectasis is possible [

14]. Barium transit is diagnostic only when the digestive tract is implicated.

Peritoneography is a somewhat neglected examination that can nonetheless reveal a diaphragmatic breach when iodinated contrast medium is seen in the thoracic cavity [

43,

44]. It also helps to clarify the hernia's nature by indicating the presence of a hernial sac, as evidenced by the distinctly circumscribed nature of the contrast medium within the thoracic projection area. Since the contrast medium did not spread into the pericardial sac, this procedure ruled out a pericardoperitoneal hernia, a conclusion that was already not in doubt from the plain radiographs. Peritoneography enabled the confirmation of the diagnosis of a true diaphragmatic hernia in one cat [

16] and two dogs [

21]; the images acquired from theses cases are fully comparable to those of the case we are presenting.

Some false negatives may occur with this procedure. In one instance, positive contrast peritoneography was attempted but failed to demonstrate any connection between the pleural and peritoneal cavities due to the sequestration of the contrast medium within the falciform ligament [

10]. A study involving 35 cats demonstrated comparable accuracy between ultrasound and peritoneography for diagnosing traumatic diaphragmatic hernias, with a 94% diagnostic rate (33/35) [

45]. In 2 cases from this group (6%), the contrast medium did not disperse into the thorax; the authors blame adhesions as a potential cause. However, adhesions are uncommon in cases of diaphragmatic hernia, implying that it is more probable that the organs completely block the diaphragmatic opening.

Peritoneography is advantageous for its simplicity, lack of sedation requirement, and accessibility to all veterinarians. However, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are more sensitive methods for diagnosing diaphragmatic hernias and are the preferred diagnostic tools in human medicine. In feline cases, three reports of true diaphragmatic hernias were identified through computed tomography [

13,

18,

19]. On CT images, a thin membrane connected with the diaphragm and creating a hernial sac can be seen [

19].

3.8. Indications for Surgery

Despite the absence of clinical symptoms associated with its diaphragmatic hernia, prophylactic surgery was elected for the cat. Surgical intervention is generally the preferred course of action when a “classic” diaphragmatic hernia is suspected, to prevent the entrapment of additional organs, organ strangulation, and the onset of respiratory distress symptoms. However, the decision for surgery in this particular case could be seen as debatable since a true diaphragmatic hernia was confirmed via peritoneography, with the organs theoretically contained within a hernial sac and, thus, unlikely to massively protrude into the thoracic cavity.

Nearly all veterinary case reports (8 out of 10) advocate for surgical intervention, with laparotomy confirming the diagnosis of a true diaphragmatic hernia and allowing the correction of the defect. In 2 reports, the asymptomatic anomaly was not surgically addressed, which is a conceivable approach [

12,

19]. In human medicine, most Morgagni hernias are identified only after they have progressed [

33]; considering the risk of incarceration, surgical repair is advised for all diagnosed Morgagni hernias [

32,

33].

4. Conclusions

True diaphragmatic hernias, also known as pleuroperitoneal hernias, are uncommon congenital anomalies in cats, often asymptomatic and discovered incidentally. The case presented here is analogous to the Morgagni hernia found in humans. It highlights the value of a straightforward radiographic test, peritoneography, not just for confirming the presence of a diaphragmatic hernia but also for determining its nature, here congenital, in a scenario where a typical traumatic diaphragmatic hernia was anticipated. The management of this incidental finding with surgery is debatable. Laparotomy can confirm the diagnosis, the operation is considered simple and low risk; due to the presence of a hernial sac, there is no open chest operating time.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. F.A.R. and T. C. performed the peritoneography and the surgery, N. A. took care of the cat, J.-Y. D. and T. C. wrote the article.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Frye, F.L. Hiatal diaphragmatic hernia and tricholithiasis in a Golden cat (a case history). Vet Med Small Anim Clin 1972, 67, 391-392.

- Peterson, S.L. Esophageal hiatal hernia in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1983, 183, 325-326.

- Prymak, C.; Saunders, H.M.; Washabau, R.J. Hiatal hernia repair by restoration and stabilization of normal anatomy. An evaluation in four dogs and one cat. Vet Surg 1989, 18, 386-391. [CrossRef]

- Owen, M.C.; Morris, P.J.; Bateman, R.S. Concurrent gastro-oesophageal intussusception, trichobezoar and hiatal hernia in a cat. N Z Vet J 2005, 53, 371-374. [CrossRef]

- DeSandre-Robinson, D.M.; Madden, S.N.; Walker, J.T. Nasopharyngeal stenosis with concurrent hiatal hernia and megaesophagus in an 8-year-old cat. J Feline Med Surg 2011, 13, 454-459. [CrossRef]

- Meixner, M.; Strohmeyer, K. [Hiatal hernia in a cat]. Tierarztl Prax Ausg K Kleintiere Heimtiere 2012, 40, 278-282.

- Gambino, J.M.; Sivacolundhu, R.; DeLucia, M.; Hiebert, E. Repair of a sliding (type I) hiatal hernia in a cat via herniorrhaphy, esophagoplasty and floppy Nissen fundoplication. JFMS Open Rep 2015, 1, 2055116915602498. [CrossRef]

- Siow, J.W.; Hoon, Q.J.; Jenkins, E.; Heblinski, N.; Makara, M. Caval foramen hernia in a cat. JFMS Open Rep 2020, 6, 2055116920964021. [CrossRef]

- Kvitka, D.; Juodzente, D.; Rudenkovaite, G.; Burbaite, E.; Laukute, M. Successful early diagnosis and surgical treatment of congenital caval foramen hernia in an 8-month-old mixed breed cat. Braz J Vet Med 2023, 45, e005622. [CrossRef]

- Mann, F.A.; Aronson, E.; Keller, G. Surgical correction of a true congenital pleuroperitoneal diaphragmatic hernia in a cat. J Am An Hosp Assoc 1991, 27, 501–507.

- Voges, A.K.; Bertrand, S.; Hill, R.C.; Neuwirth, L.; Schaer, M. True diaphragmatic hernia in a cat. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 1997, 38, 116-119. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.A.; Goggin, J.M.; Kraft, S.L. What is your diagnosis? A 2-cm rounded structure similar in opacity to adjacent falciform fat located between the apex of the heart and the cupula of the diaphragm along the ventral midline of the thorax. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999, 214, 479-480.

- Green, E.; Thamm, D. What is your diagnosis? A soft-tissue mass in the thoracic cavity between the heart and the right crus of the diaphragm. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000, 216, 23-24.

- White, J.D.; Tisdall, P.L.; Norris, J.M.; Malik, R. Diaphragmatic hernia in a cat mimicking a pulmonary mass. J Feline Med Surg 2003, 5, 197-201. [CrossRef]

- Cariou, M.P.; Shihab, N.; Kenny, P.; Baines, S.J. Surgical management of an incidentally diagnosed true pleuroperitoneal hernia in a cat. J Feline Med Surg 2009, 11, 873-877. [CrossRef]

- Parry, A. Positive contrast peritoneography in the diagnosis of a pleuroperitoneal diaphragmatic hernia in a cat. J Feline Med Surg 2010, 12, 141-143. [CrossRef]

- Gombač, M.; Vrecl, M.; Svara, T. Congenital diaphragmatic eventration in two closely related British Shorthair cats. J Feline Med Surg 2011, 13, 276-279. [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.M.; Ryan, S.D.; Johnstone, T.; Beck, C. Imaging Diagnosis-the Computed Tomography Features of a Pleuroperitoneal Hernia in a Cat. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2017, 58, E55-E59. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-K.; Jeong, W.; Choi, J. Remnant parietal serosa detection in a cat with true diaphragmatic hernia using computed tomography. Korean J Vet Res 2019, 59, 105-108. [CrossRef]

- Pilli, M.; Ozgencil, F.E.; Seyrek-Intas, D.; Gultekin, C.; Turgut, K. Pleuroperitoneal true diaphragmatic hernia of the liver in a cat. Tierarztl Prax Ausg K Kleintiere Heimtiere 2020, 48, 292-296. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, M.; Yoon, J. Imaging diagnosis--positive contrast peritoneographic features of true diaphragmatic hernia. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2009, 50, 185-187. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, H.F.; Basso, P.C.; Faria, K.L.; Oliveira, M.T.; Souza, F.W.; Garcia, É.V.; Feranti, J.P.S.; Silva, M.A.M.; Brun, M.V. Laparoscopic repair of congenital pleuroperitoneal hernia using a polypropylene mesh in a dog. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2015, 67, 1547-1553. [CrossRef]

- Devereux, E.A.; Scharf, V.F. Surgical technique and complications associated with laparoscopic pleuroperitoneal diaphragmatic herniorrhaphy in a dog. Veterinary Record Case Reports 2023, 11, e657. [CrossRef]

- Keep, J.M. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia in a cat. Aust Vet J 1950, 26, 193-196. [CrossRef]

- Bismuth, C.; Deroy, C. Congenital cranial ventral abdominal hernia, peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia and sternal cleft in a 4-year-old multiparous pregnant queen. JFMS Open Rep 2017, 3, 2055116917747741. [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.B.; Bree, M.M.; Cohen, B.J. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia in neonatal dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1968, 153, 942-944.

- Valentine, B.A.; Cooper, B.J.; Dietze, A.E.; Noden, D.M. Canine congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Vet Intern Med 1988, 2, 109-112. [CrossRef]

- Auger, J.M.; Riley, S.M. Combined hiatal and pleuroperitoneal hernia in a shar-pei. Can Vet J 1997, 38, 640-642.

- Rossanese, M.; Pivetta, M.; Pereira, N.; Burrow, R. Congenital pleuroperitoneal hernia presenting as gastrothorax in five cavalier King Charles spaniel dogs. J Small Anim Pract 2019, 60, 701-704. [CrossRef]

- White, J.J.; Suzuki, H. Hernia through the foramen of Bochdalek: a misnomer. J Pediatr Surg 1972, 7, 60-61. [CrossRef]

- Adereti, C.; Zahir, J.; Robinson, E.; Pursel, J.; Hamdallah, I. A Case Report and Literature Review on Incidental Morgagni Hernia in Bariatric Patients: To Repair or Not to Repair? Cureus 2023, 15, e39950. [CrossRef]

- Svetanoff, W.J.; Rentea, R.M. Morgagni Hernia. In StatPearls; 2023.

- Sharma, A.; Khanna, R.; Panigrahy, P.; Meena, R.N.; Mishra, S.P.; Khanna, S. An Incidental Finding of Morgagni Hernia in an Elderly Female and Its Successful Management: A Rare Case Report and Review of Literature. Cureus 2023, 15, e42676. [CrossRef]

- Palma, R.; Angrisani, F.; Santonicola, A.; Iovino, P.; Ormando, V.M.; Maselli, R.; Angrisani, L. Case report: Laparoscopic nissen-sleeve gastrectomy in a young adult with incidental finding of Morgagni-Larrey hernia. Front Surg 2023, 10, 1227567. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Alabdrabalmeer, M.; Alealiwi, M.; Danan, O.A.; Alshomimi, S. Incidental Morgagni hernia found during laparoscopic repair of hiatal hernia: Case report & review of literature. Int J Surg Case Rep 2019, 57, 97-101. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.K.; Moon, H.S.; Jung, H.Y.; Sung, J.K.; Gang, S.H.; Kim, M.H. An Incidental Discovery of Morgagni Hernia in an Elderly Patient Presented with Chronic Dyspepsia. Korean J Gastroenterol 2017, 69, 68-73. [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.A.; Karass, M.; Page, A.J.; Shehata, B.M.; Durham, M.M. Extra-hepatic bile duct hamartoma in a 10-month-old with a morgagni hernia and multiple anatomical anomalies: a rare and incidental finding. Pediatr Surg Int 2013, 29, 745-748. [CrossRef]

- Gaco, S.; Krdzalic, G.; Krdzalic, A. Incarcerated Morgagni hernia in an octogenarian with incidental right-sided colonic malignancy. Med Arch 2013, 67, 73-74. [CrossRef]

- McCabe, A.; Watts, A.; Abdulrazak, A.; McCann, B. Incidental finding of a large Morgagni's hernia in a 76-year-old lady. BMJ Case Rep 2012, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Zisa, M.; Pulvirenti, E.; Toro, A.; Mannino, M.; Reale, G.; Di Carlo, I. Seizure attack and Morgagni diaphragmatic hernia: incidental diagnosis or direct correlation? Updates Surg 2011, 63, 55-58. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Ghani, A. Morgagni hernia: incidental repair during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Surg 1995, 5, 123-125. [CrossRef]

- Al-Salem, H. Incidental bilateral Morgagni hernia in a traumatized child. Aust N Z J Surg 1992, 62, 910-912. [CrossRef]

- Rendano Jr, V. Positive contrast peritoneography: An aid in the radiographic diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia. Veterinary Radiology 1979, 20, 67-73.

- Stickle, R.L. Positive-contrast celiography (peritoneography) for the diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia in dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1984, 185, 295-298.

- Kibar, M.E.; Bumi̇n, A.; Kaya, M.; Alkan, Z. Use of peritoneography (positive contrast che liography) and ultrasonography in the diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia : review of 35 cats. Revue De Medecine Veterinaire 2006, 157, 331-335.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).