Submitted:

12 January 2024

Posted:

15 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Fusion Strategies to Produce Heterologous Transmembrane Proteins in E. coli

2.1. Fusion Proteins aid the Insertion and Folding of Foreign TMPs in the E. coli Plasma Membrane

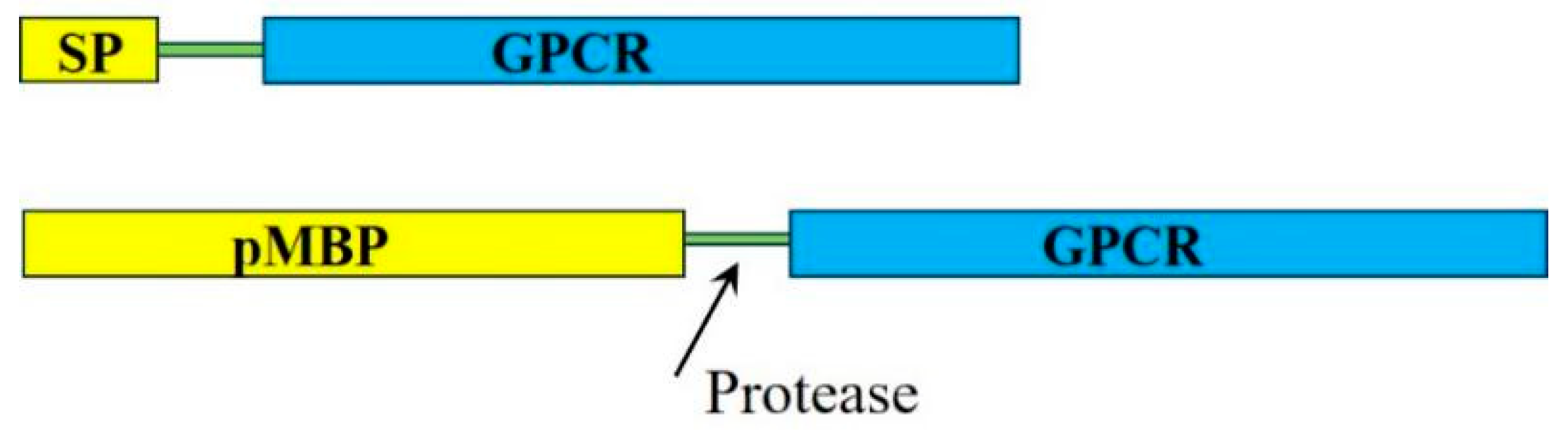

2.1.1. Signal Peptides and Precursor Maltose Binding Protein Fusion Strategies

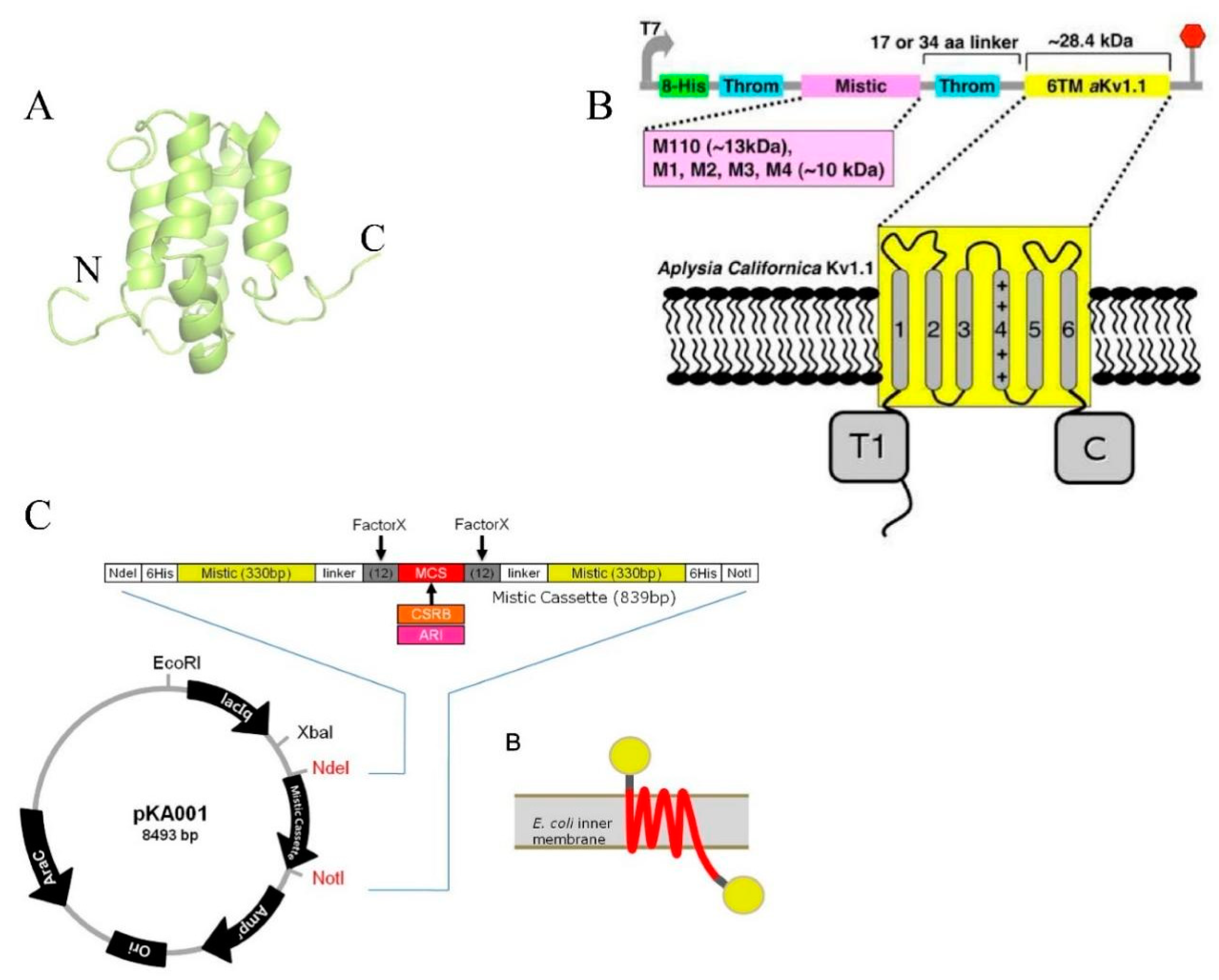

2.1.2. Mistic Protein Fusion Strategies

2.1.3. Apolipoprotein A-I Fusion Strategy

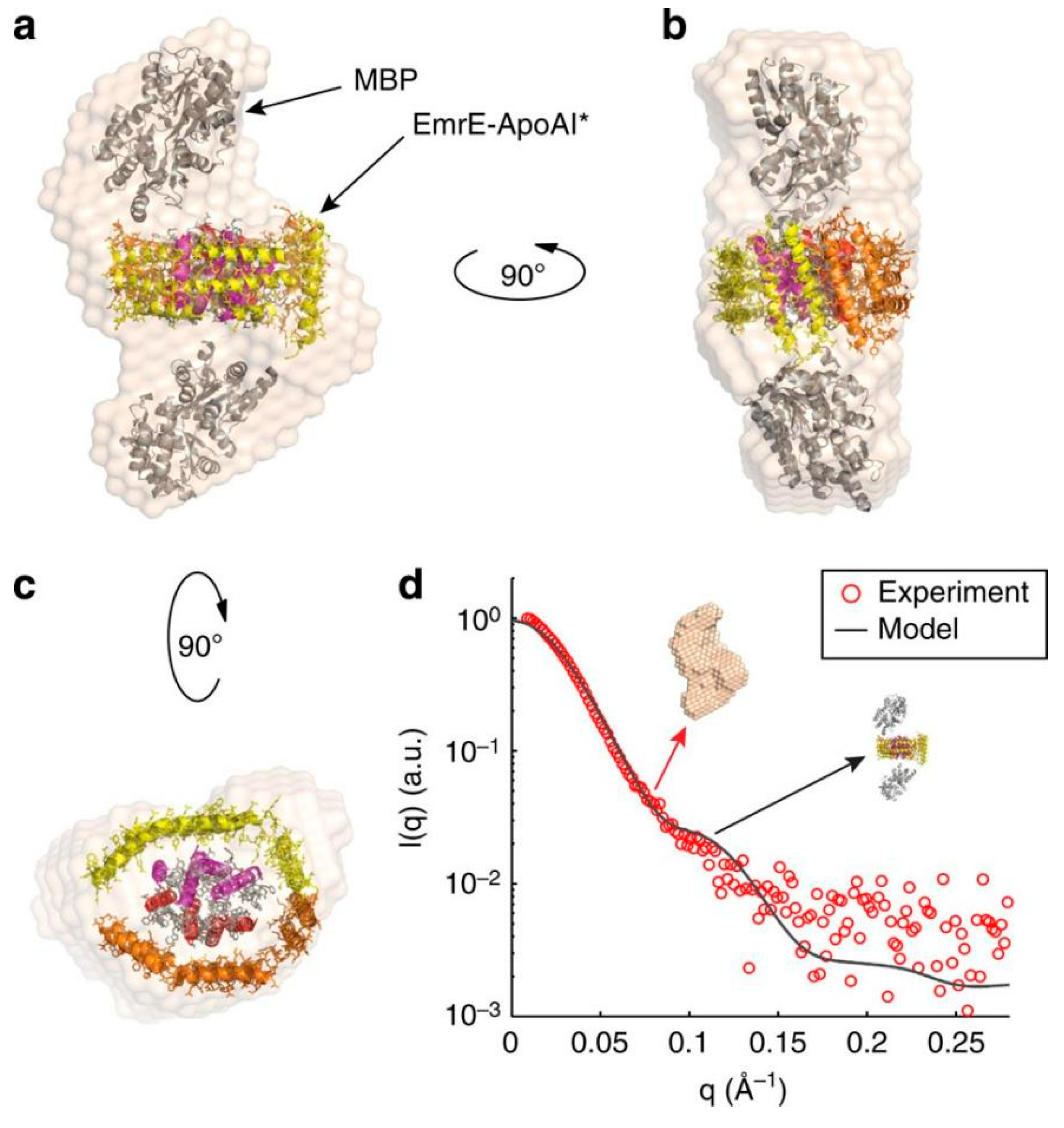

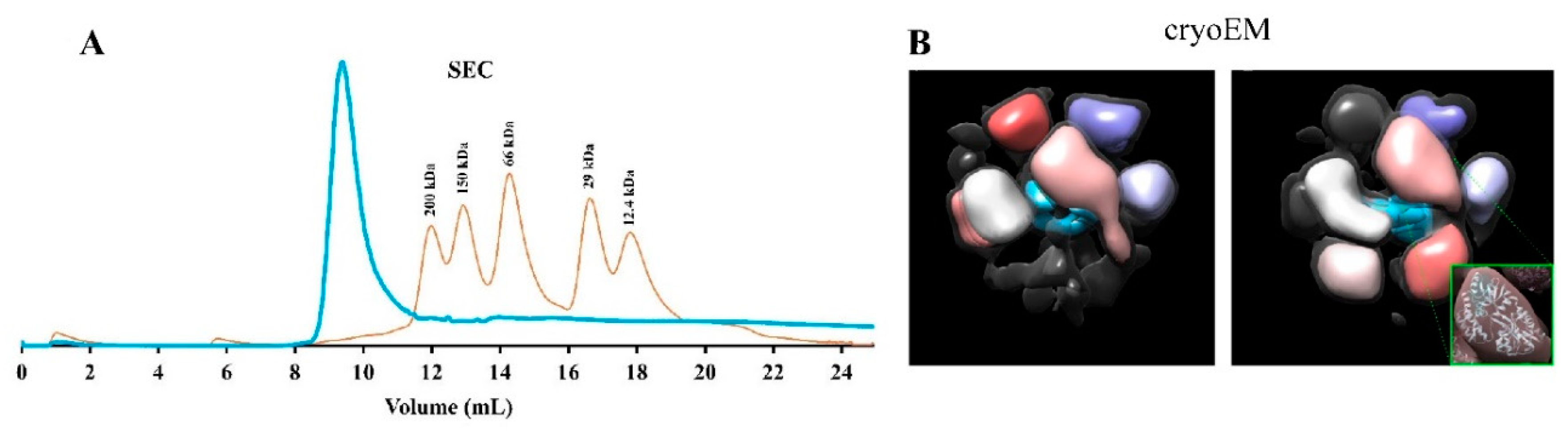

2.2. Fusion Proteins aid the Production of Heterologous TMPs in Soluble Form in E. coli

2.2.1. Mature (without Signal Peptide) Maltose Binding Protein Fusion Strategies

2.2.2. Apolipoprotein A-I Strategies to Produce Soluble TMPs

2.2.3. Other Protein Design Strategies to Produce and Stabilize Soluble TMPs

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Cournia, Z; Allen, TW; Andricioaei, I; Antonny, B; Baum, D; Brannigan, G; Buchete, NV; Deckman, JT; Delemotte, L; Del Val, C; et al. Membrane Protein Structure, Function, and Dynamics: a Perspective from Experiments and Theory. J Membr Biol. 2015, 248, 611–640. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S; Jeon, TJ; Oberai, A; Yang, D; Schmidt, JJ; Bowie, JU. Transmembrane glycine zippers: physiological and pathological roles in membrane proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005, 102, 14278–14283. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, JL. The lipid bilayer membrane and its protein constituents. J Gen Physiol. 2018, 150, 1472–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinko, JT; Huang, H; Penn, WD; Capra, JA; Schlebach, JP; Sanders, CR. Folding and Misfolding of Human Membrane Proteins in Health and Disease: From Single Molecules to Cellular Proteostasis. Chem Rev. 2019, 119, 5537–5606. [CrossRef]

- Wallin, E; von Heijne, G. Genome-wide analysis of integral membrane proteins from eubacterial, archaean, and eukaryotic organisms. Protein Sci. 1998, 7, 1029–1038. [CrossRef]

- Overington, JP; Al-Lazikani, B; Hopkins, AL.. How many drug targets are there? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 993–996. [CrossRef]

- Yin, H; Flynn, AD. Drugging Membrane Protein Interactions. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2016, 18, 51–76. [CrossRef]

- Majeed, S; Ahmad, AB; Sehar, U; Georgieva, ER. Lipid Membrane Mimetics in Functional and Structural Studies of Integral Membrane Proteins. Membranes. 2021, 11, 685. [CrossRef]

- Errasti-Murugarren, E; Bartoccioni, P; Palacin, M. Membrane Protein Stabilization Strategies for Structural and Functional Studies. Membranes. 2021, 11, 155. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J; Qin, H; Li, C; Sharma, M; Cross, TA; Gao, FP. Structural biology of transmembrane domains: efficient production and characterization of transmembrane peptides by NMR. Protein Sci. 2007, 16, 2153–2165. [CrossRef]

- Gulezian, E; Crivello, C; Bednenko, J; Zafra, C; Zhang, Y; Colussi, P; Hussain, S. Membrane protein production and formulation for drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2021, 42, 657–674. [CrossRef]

- Athanasios Kesidis; Peer Depping; Alexis Lodé; Afroditi Vaitsopoulou; Roslyn M. Bill; D., A; Goddard; Rothnie, AJ. Expression of eukaryotic membrane proteins in eukaryotic and prokaryotic hosts. (accessed.

- Bernaudat, F; Frelet-Barrand, A; Pochon, N; Dementin, S; Hivin, P; Boutigny, S; Rioux, JB; Salvi, D; Seigneurin-Berny, D; Richaud, P; et al. Heterologous expression of membrane proteins: choosing the appropriate host. PLoS One. 2011, 6, e29191. [CrossRef]

- Rosano, GL; Ceccarelli, EA. Recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli: advances and challenges. Front Microbiol. 2014, 5, 172. [CrossRef]

- Hattab, G; Warschawski, DE; Moncoq, K; Miroux, B. Escherichia coli as host for membrane protein structure determination: a global analysis. Sci Rep. 2015, 5, 12097. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, K; Javed, W; Vallet, S; Lesterlin, C; Candusso, MP; Ding, F; Xu, XN; Ebel, C; Jault, JM; Orelle, C. Functionality of membrane proteins overexpressed and purified from E. coli is highly dependent upon the strain. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 2654. [CrossRef]

- Kleiner-Grote, GR; Risse, JM; Friehs, K. Secretion of recombinant proteins from E. coli. Engineering in Life Sciences. 2018, 18, 532–550.

- Francis, DM; Page, R. Strategies to optimize protein expression in E. coli. Current protocols in protein science. 2010, 61, 5–24.

- Korepanova, A; Moore, JD; Nguyen, HB; Hua, Y; Cross, TA; Gao, F. Expression of membrane proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Escherichia coli as fusions with maltose binding protein. Protein Expr Purif. 2007, 53, 24–30. [CrossRef]

- Dvir, H; Choe, S. Bacterial expression of a eukaryotic membrane protein in fusion to various Mistic orthologs. Protein expression and purification. 2009, 68, 28–33.

- Rogl, H; Kosemund, K; Kuhlbrandt, W; Collinson, I. Refolding of Escherichia coli produced membrane protein inclusion bodies immobilised by nickel chelating chromatography. FEBS Lett. 1998, 432, 21–26. [CrossRef]

- Lee, KA; Lee, SS; Kim, SY; Choi, AR; Lee, JH; Jung, KH. Mistic-fused expression of algal rhodopsins in Escherichia coli and its photochemical properties. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015, 1850, 1694–1703. [CrossRef]

- Reuten, R; Nikodemus, D; Oliveira, MB; Patel, TR; Brachvogel, B; Breloy, I; Stetefeld, J; Koch, M. Maltose-binding protein (MBP), a secretion-enhancing tag for mammalian protein expression systems. PloS one. 2016, 11, e0152386.

- Majeed, S; Adetuyi, O; Borbat, PP; Islam, MM; Ishola, O; Zhao, B; Georgieva, ER. Insights into the oligomeric structure of the HIV-1 Vpu protein. Journal of Structural Biology. 2023, 215, 107943.

- Majeed, S; Dang, L; Islam, MM; Ishola, O; Borbat, PP; Ludtke, SJ; Georgieva, ER. HIV-1 Vpu protein forms stable oligomers in aqueous solution via its transmembrane domain self-association. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 14691. [CrossRef]

- Mizrachi, D; Chen, Y; Liu, J; Peng, HM; Ke, A; Pollack, L; Turner, RJ; Auchus, RJ; DeLisa, MP. Making water-soluble integral membrane proteins in vivo using an amphipathic protein fusion strategy. Nat Commun. 2015, 6, 6826. [CrossRef]

- Grisshammer, R; Duckworth, R; Henderson, R. Expression of a rat neurotensin receptor in Escherichia coli. Biochemical Journal. 1993, 295, 571–576.

- TUCKER, J; GRISSHAMMER, R. Purification of a rat neurotensin receptor expressed in Escherichia coli. Biochemical Journal. 1996, 317, 891–899.

- Furukawa, H; Haga, T. Expression of functional M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor in Escherichia coli. The journal of biochemistry. 2000, 127, 151–161.

- Grisshammer, R; Little, J; Aharony, D. Expression of rat NK-2 (neurokinin A) receptor in E. coli. Receptors & channels. 1994, 2, 295–302.

- Yeliseev, AA; Wong, KK; Soubias, O; Gawrisch, K. Expression of human peripheral cannabinoid receptor for structural. 2005.

- Lee, KA; Lee, S-S; Kim, SY; Choi, AR; Lee, J-H; Jung, K-H. Mistic-fused expression of algal rhodopsins in Escherichia coli and its photochemical properties. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects. 2015, 1850, 1694–1703.

- Ishola, O; Ogunbowale, A; Islam, MM; Hadadianpour, E; Majeed, S; Adetuyi, O; Georgieva, ER. Protein engineering, production, reconstitution in lipid nanoparticles, and initial characterization of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis EfpA drug exporter. bioRxiv. 2023, 2023.2006. 2026.546575.

- Mizrachi, D; Chen, Y; Liu, J; Peng, H-M; Ke, A; Pollack, L; Turner, RJ; Auchus, RJ; DeLisa, MP. Making water-soluble integral membrane proteins in vivo using an amphipathic protein fusion strategy. Nature Communications. 2015, 6, 6826.

- Eliseev, R; Alexandrov, A; Gunter, T. High-yield expression and purification of p18 form of Bax as an MBP-fusion protein. Protein expression and purification. 2004, 35, 206–209.

- Brown, MS; Ye, J; Rawson, RB; Goldstein, JL.. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis: a control mechanism conserved from bacteria to humans. Cell. 2000, 100, 391–398.

- Bertin, B; Freissmuth, M; Breyer, RM; Schutz, W; Strosberg, AD; Marullo, S. Functional expression of the human serotonin 5-HT1A receptor in Escherichia coli. Ligand binding properties and interaction with recombinant G protein alpha-subunits. J Biol Chem. 1992, 267, 8200–8206.

- Fiermonte, G; Walker, JE; Palmieri, F. Abundant bacterial expression and reconstitution of an intrinsic membrane-transport protein from bovine mitochondria. Biochem J. 1993, 294 (Pt 1), 293-299. [CrossRef]

- Jappelli, R; Perrin, MH; Lewis, KA; Vaughan, JM; Tzitzilonis, C; Rivier, JE; Vale, WW; Riek, R. Expression and functional characterization of membrane-integrated mammalian corticotropin releasing factor receptors 1 and 2 in Escherichia coli. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e84013. [CrossRef]

- Grisshammer, R; Duckworth, R; Henderson, R. Expression of a rat neurotensin receptor in Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 1993, 295 (Pt 2), 571–576. [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J; Grisshammer, R. Purification of a rat neurotensin receptor expressed in Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 1996, 317 ( Pt 3) (Pt 3), 891–899. [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, H; Haga, T. Expression of functional M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor in Escherichia coli. J Biochem. 2000, 127, 151–161. [CrossRef]

- Grisshammer, R; Little, J; Aharony, D. Expression of rat NK-2 (neurokinin A) receptor in E. coli. Recept Channels. 1994, 2, 295–302.

- Yeliseev, AA; Wong, KK; Soubias, O; Gawrisch, K. Expression of human peripheral cannabinoid receptor for structural studies. Protein Sci. 2005, 14, 2638–2653. [CrossRef]

- Abiko, LA; Rogowski, M; Gautier, A; Schertler, G; Grzesiek, S. Efficient production of a functional G protein-coupled receptor in E. coli for structural studies. J Biomol NMR. 2021, 75, 25–38. [CrossRef]

- Egloff, P; Hillenbrand, M; Klenk, C; Batyuk, A; Heine, P; Balada, S; Schlinkmann, KM; Scott, DJ; Schutz, M; Pluckthun, A. Structure of signaling-competent neurotensin receptor 1 obtained by directed evolution in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014, 111, E655–E662. [CrossRef]

- Wu, FJ; Williams, LM; Abdul-Ridha, A; Gunatilaka, A; Vaid, TM; Kocan, M; Whitehead, AR; Griffin, MDW; Bathgate, RAD; Scott, DJ; et al. Probing the correlation between ligand efficacy and conformational diversity at the alpha(1A)-adrenoreceptor reveals allosteric coupling of its microswitches. J Biol Chem. 2020, 295, 7404–7417. [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M; Deluigi, M; Pantic, M; Vacca, S; Baumann, C; Scott, DJ; Pluckthun, A; Zerbe, O. Optimizing the alpha(1B)-adrenergic receptor for solution NMR studies. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2020, 1862, 183354. [CrossRef]

- Waugh, DS. An overview of enzymatic reagents for the removal of affinity tags. Protein Expr Purif. 2011, 80, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, A; Feng, R; Tong, Q; Zhang, Y; Xie, X-Q. Mistic and TarCF as fusion protein partners for functional expression of the cannabinoid receptor 2 in Escherichia coli. Protein expression and purification. 2012, 83, 128–134.

- Roosild, TP; Greenwald, J; Vega, M; Castronovo, S; Riek, R; Choe, S. NMR structure of Mistic, a membrane-integrating protein for membrane protein expression. Science. 2005, 307, 1317–1321. [CrossRef]

- Dvir, H; Lundberg, ME; Maji, SK; Riek, R; Choe, S. Mistic: cellular localization, solution behavior, polymerization, and fibril formation. Protein Sci. 2009, 18, 1564–1570. [CrossRef]

- Marino, J; Bordag, N; Keller, S; Zerbe, O. Mistic's membrane association and its assistance in overexpression of a human GPCR are independent processes. Protein Science. 2015, 24, 38–48.

- Marino, J; Geertsma, ER; Zerbe, O. Topogenesis of heterologously expressed fragments of the human Y4 GPCR. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012, 1818, 3055–3063. [CrossRef]

- Alves, NS; Astrinidis, SA; Eisenhardt, N; Sieverding, C; Redolfi, J; Lorenz, M; Weberruss, M; Moreno-Andrés, D; Antonin, W. MISTIC-fusion proteins as antigens for high quality membrane protein antibodies. Scientific Reports. 2017, 7, 41519.

- Blain, KY; Kwiatkowski, W; Choe, S. The functionally active Mistic-fused histidine kinase receptor, EnvZ. Biochemistry. 2010, 49, 9089–9095. [CrossRef]

- Alves, NS; Astrinidis, SA; Eisenhardt, N; Sieverding, C; Redolfi, J; Lorenz, M; Weberruss, M; Moreno-Andres, D; Antonin, W. MISTIC-fusion proteins as antigens for high quality membrane protein antibodies. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 41519. [CrossRef]

- Roosild, TP; Greenwald, J; Vega, M; Castronovo, S; Riek, R; Choe, S. NMR structure of Mistic, a membrane-integrating protein for membrane protein expression. Science. 2005, 307, 1317–1321.

- Curtiss, LK; Valenta, DT; Hime, NJ; Rye, KA. What is so special about apolipoprotein AI in reverse cholesterol transport? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006, 26, 12–19. [CrossRef]

- Denisov, IG; Grinkova, YV; Lazarides, AA; Sligar, SG. Directed self-assembly of monodisperse phospholipid bilayer Nanodiscs with controlled size. J Am Chem Soc. 2004, 126, 3477–3487. [CrossRef]

- Denisov, IG; Sligar, SG. Nanodiscs for structural and functional studies of membrane proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016, 23, 481–486. [CrossRef]

- Denisov, IG; Sligar, SG. Nanodiscs in Membrane Biochemistry and Biophysics. Chem Rev. 2017, 117, 4669–4713. [CrossRef]

- Ishola, O; Ogunbowale, A; Islam, MM; Hadadianpour, E; Majeed, S; Adetuyi, O; Georgieva, ER. Protein engineering, production, reconstitution in lipid nanoparticles, and initial characterization of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis EfpA drug exporter. bioRxiv. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, RO; Forte, TM; Oda, MN. Optimized bacterial expression of human apolipoprotein A-I. Protein Expr Purif. 2003, 27, 98–103. [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, H; Krieger, J; Olszewski, JD; Von Heijne, G; Prestwich, GD; Breer, H. Expression of an olfactory receptor in Escherichia coli: purification, reconstitution, and ligand binding. Biochemistry. 1996, 35, 16077–16084. [CrossRef]

- Leviatan, S; Sawada, K; Moriyama, Y; Nelson, N. Combinatorial method for overexpression of membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2010, 285, 23548–23556. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J; Qin, H; Gao, FP; Cross, TA. A systematic assessment of mature MBP in membrane protein production: overexpression, membrane targeting and purification. Protein Expr Purif. 2011, 80, 34–40. [CrossRef]

- Chen, GQ; Gouaux, JE. Overexpression of bacterio-opsin in Escherichia coli as a water-soluble fusion to maltose binding protein: efficient regeneration of the fusion protein and selective cleavage with trypsin. Protein Sci. 1996, 5, 456–467. [CrossRef]

- Eliseev, R; Alexandrov, A; Gunter, T. High-yield expression and purification of p18 form of Bax as an MBP-fusion protein. Protein Expr Purif. 2004, 35, 206–209. [CrossRef]

- Lei, X; Ahn, K; Zhu, L; Ubarretxena-Belandia, I; Li, YM. Soluble oligomers of the intramembrane serine protease YqgP are catalytically active in the absence of detergents. Biochemistry. 2008, 47, 11920–11929. [CrossRef]

- Duong-Ly, KC; Gabelli, SB. Affinity Purification of a Recombinant Protein Expressed as a Fusion with the Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP) Tag. Methods Enzymol. 2015, 559, 17–26. [CrossRef]

- Sun, P; Tropea, JE; Waugh, DS. Enhancing the solubility of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli by using hexahistidine-tagged maltose-binding protein as a fusion partner. Heterologous gene expression in E. coli: methods and protocols. 2011, 259-274.

- Lebendiker, M; Danieli, T. Purification of proteins fused to maltose-binding protein. Protein Chromatography: Methods and Protocols. 2011, 281-293.

- Nallamsetty, S; Waugh, DS. Mutations that alter the equilibrium between open and closed conformations of Escherichia coli maltose-binding protein impede its ability to enhance the solubility of passenger proteins. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2007, 364, 639–644.

- Raran-Kurussi, S; Waugh, DS. The ability to enhance the solubility of its fusion partners is an intrinsic property of maltose-binding protein but their folding is either spontaneous or chaperone-mediated. PloS one. 2012, 7, e49589.

- Raran-Kurussi, S; Keefe, K; Waugh, DS. Positional effects of fusion partners on the yield and solubility of MBP fusion proteins. Protein expression and purification. 2015, 110, 159–164.

- Luckey, M. Membrane structural biology: with biochemical and biophysical foundations; Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Smalinskaitė, L; Hegde, RS. The biogenesis of multipass membrane proteins. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2023, 15, a041251.

- Brown, MS; Ye, J; Rawson, RB; Goldstein, JL.. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis: a control mechanism conserved from bacteria to humans. Cell. 2000, 100, 391–398. [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, MS; Kopan, R. Intramembrane proteolysis: theme and variations. Science. 2004, 305, 1119–1123. [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, ER. Protein Conformational Dynamics upon Association with the Surfaces of Lipid Membranes and Engineered Nanoparticles: Insights from Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Molecules. 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, D; Svergun, DI. DAMMIF, a program for rapid ab-initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J Appl Crystallogr. 2009, 42 (Pt 2), 342-346. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, DA; Xie, M; Hughes, V; Wilce, MC; Roujeinikova, A. Design, purification and characterization of a soluble variant of the integral membrane protein MotB for structural studies. J R Soc Interface. 2013, 10, 20120717. [CrossRef]

- Minamino, T; Imada, K; Namba, K. Molecular motors of the bacterial flagella. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008, 18, 693–701. [CrossRef]

- Schafmeister, CE; Miercke, LJ; Stroud, RM. Structure at 2.5 A of a designed peptide that maintains solubility of membrane proteins. Science. 1993, 262, 734–738. [CrossRef]

| Fusion tag | Produced TMP | Benefit for structural and/or functional studies | References |

| MBP signal peptide/entire MBP | Serotonin 5-HT1A, Neurotensin receptor, NK-2 (Neurokinin A), M2 muscarinic acetyl choline receptor, and Peripheral cannabinoid receptor | It promotes the proper folding and insertion of the recombinant fusion protein into the plasma membrane. It supports the application of functional assays in the study of the activities of the transmembrane protein |

Grisshammer et al (1993)27, Tucker & Grisshammer (1996)28, Furukawa & Haga (2000)29, Grisshammer et al (1994)30, and Yeliseev et al (2005)31 |

| Mistic protein | aKv1.1 channel, and eukaryotic type I rhodopsin | It promotes high expression yield of heterologous TMPs as well as facilitating the expression of functional proteins with both N-terminus inside or N-terminus outside | Dvir & Choe (2009)20, Lee, K. A., et al. (2015)32 |

| Apolipoprotein AI | Mtb EfpA, Mtb-EfpA, EmrE transporter, human cyt b5, HSD17β3, GluA2, DsbB, CLDN1, CLDN3, S5ɑR1, S5ɑR2, NRC-1bR, OmpX, and VDAC1 | The tertiary conformation of the TMP-lipid-apoAI forms a discoidal nanoparticle stabilized by a double belt of apoAI It increases the solubilization of TMPs with high levels of expression and supports the functional study of the protein (e.g., ligand binding and protein-protein interaction). |

Ishola et al (2023)33, Mizrachi, D., et al. (2015)34 |

| mMBP without signal peptide | Vpu, p18, and Yqgp protease | It is useful as a purification affinity tag when in combination with polyhistidine tag for Ni-affinity purification. It is a natural fusion tag that is a solubility enhancer |

Majeed, S., et al. (2023)24, Eliseev, R., et al. (2004)35, Brown, M. S., et al. (2000)36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).