1. Introduction

Image steganography is a concealed communication method that uses seemingly benign digital images to conceal sensitive information. The image with hidden messages is known as a stego. The mainstream of existing approaches for image steganography is content-adaptive, which embeds secrets to highly textured or noisy regions by minimizing a heuristically defined distortion function that measures the statistical detectability or distortion. Based on the near-optimal steganographic coding scheme [

1,

2], numerous efficient steganographic cost functions have been put forth over the years, many of them are based on statistical models [

6,

7] or heuristic principles [

3,

4,

5]. The performance of steganography could also be enhanced by taking into account the correlations between nearby picture elements, such as [

8,

9,

10,

11].

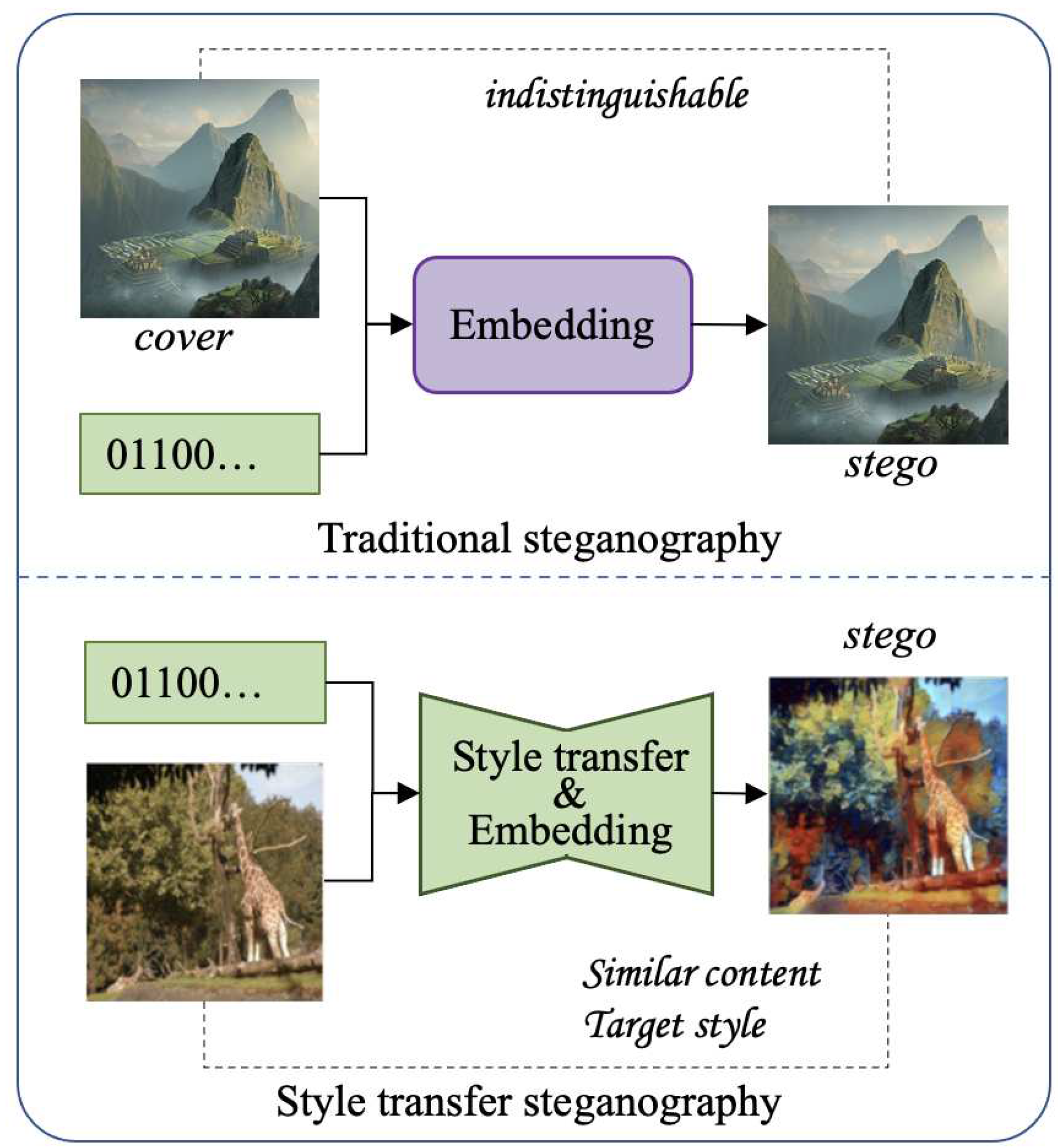

Figure 1.

Comparison with traditional image steganography and style tranfer steganography.

Figure 1.

Comparison with traditional image steganography and style tranfer steganography.

Image steganalysis, on the other hand, seeks to identify the presence of a hidden message inside an image. Traditional steganalysis methods based on statistical analysis or training a classifier [

12] based on hand-craft features [

13,

14,

15]. In recent years, the deep neural network is proposed for steganalysis [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] and their performance outperforms traditional methods, which challenges the security of the steganography. To defend against steganalysis, some researchers proposed embedding secret messages by deep neural networks and simulating the rivalry between steganography and steganalysis by a GAN (Generative Adversarial Network), which alternatively updates a generator and a discriminator. By which enhanced cover images or distortion costs could be learned. However, since these methods embed messages based on an existing image, it is possible for the adversary generates cover-stego pairs, which will provide more information for steganalysis. To solve this problem, some works utilize GAN to learn how to map pieces of secret information to the stego and directly produce stego images without the cover [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. But the images obtained by GAN is not of satisfying in terms of visual quality due to the difficulty of image generation task.

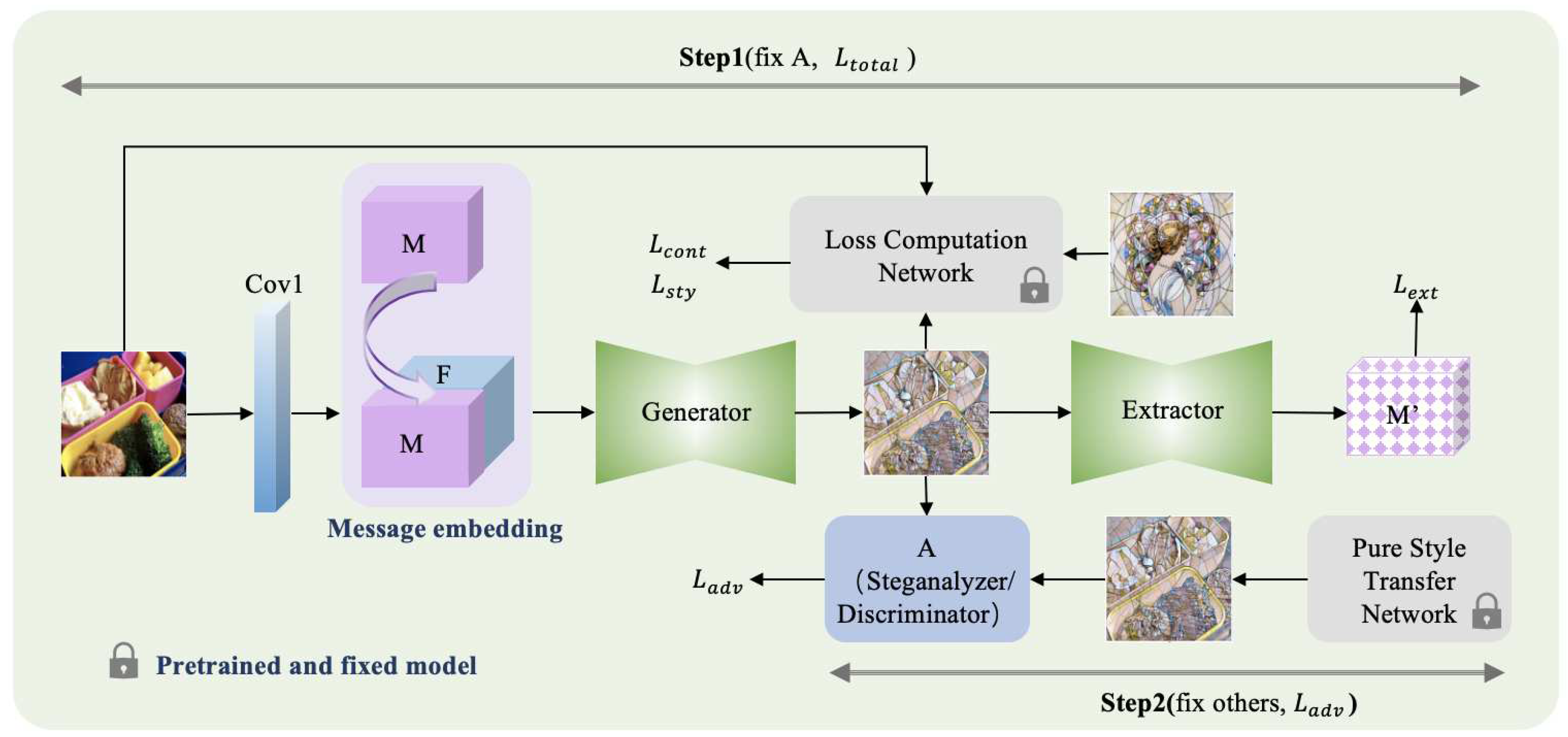

Figure 2.

Framework of hiding information in style transform network.

Figure 2.

Framework of hiding information in style transform network.

The goal of the above-mentioned methods is to keep the stego images indistinguishable from unprocessed natural images since the transfer of natural images is a common phenomenon in recent years. Recently, as the rapid growth of AGI, the well performed image generation and image processing models emerge in large numbers, such as dalle2 [

36], stable diffusion [

37], arousing the attention of steganography of the AI generated or processed images [

38,

39]. Among the images produced by AI, the art-style images become more popular in social network, thereby generating stegos that are indistinguishable from style-transferred images could be a new way for high capacity and secure steganography. In [

46], Zhong et al. proposed a steganography method in stylized images, they produced two similar stylized images with different parameters, one of them is used for embedding and another one is employed as a reference. However, because it remains dependent on the framework of embedding distortion and STC coding, the adversary may detect the stego by generating cover-stego pairs and training a classifier, thereby the stego images face the risk of being detected. In this paper, we propose to encode the secret messages into the images at the same time of generate style-transferred images. The contribution of the paper are concluded as below:

We design a framework for image steganography during the process of image style transfer. The proposed method is more secure compared to traditional steganography since it is difficult for steganalysis without corresponding cover-stego pairs.

We validate the effectiveness of the proposed method by experiments. The results show the proposed approach can successfully embed 1 bpcpp, and the generated stego cannot be distinguished from clean style transferred images generated by a model without steganography. The accuracy of the recovered information is 99%. Though it is not 100%, it can be solved by coding secret information using error correction codes before hiding them in the image.

2. Related Works

2.1. Image Steganography

The research on steganography is usually based on the "prisoner’s problem" model, which was proposed by American scholar Simmons in 1983, and is described as follows: "Assuming Alice and Bob are held in different prisons and wish to communicate with each other to plan their escape, but all communication must be checked by the warden Wendy." The steganographic communication process is shown in Figure 2.1. The sender Alice hides the message in a seemingly normal carrier by selecting a carrier that Wendy allows and using the key shared with the receiver Bob. This process can be represented as:

Then, the carrier is transmitted to the receiver Bob through a public channel. Bob receives the carrier containing the message and uses a shared key to extract the message:

Wendy, the monitor in the public channel, aims to detect the presence of covert communication.

Existing steganography methods could be divided into three categories: 1) cost based steganography, 2) model based steganography and 3) generative steganography.

2.1.1. Cost Based Steganography

Each cover element

of the cover is allocated a cost

and a probability

for modifying its value according to the image content, techniques such as UNIWARD, WOW, and HILL propose a variety of cost designing methods. The objective of cost based steganography is to embed the secret message into the cover in a way that minimizes the sum of the predicted costs of all modified pixels, which is calculated by

. To this end, the problem of secret embedding is recognized as source coding with fidelity constraint, and near optimal1 coding scheme Syndrome-Trellis Codes (STC) and Steganographic Polar Codes (SPC) have been developed [

1,

2]. Cost based steganography adaptively embedding secrets hence the steganography is imperceptible. However, the costs are occasionally determined via heuristic methods and cannot be mathematically associated with the potential of changes in embedding being detected. Moreover, when a well-informed adversary is cognizant of the changing rates of the embedding, which is taken as a kind of side information in steganalysis, and could be used by the adversary to improve steganalysis accuracy by utilizing selection-channel-aware features or convolutional neural networks.

2.1.2. Model Based Steganography

Model-based steganography establishes a mathematical model for the distribution of carriers, aiming to embed messages while preserving the inherent distribution model as much as possible. MiPOD is an example of the model based steganographic scheme. It assumes the noise residuals in a digital image follow a Gaussian distribution with zero mean and variances , which are estimated for each cover element i. The messages are embedded aim by reducing the effectiveness of the most advanced detector that an adversary can create. While this approach is theoretically secure, challenges arise due to variations in distribution models among multimedia data, such as images and videos, acquired by different sensors. Furthermore, the influence of distinct temporal and environmental factors on pixel distribution complicates the identification of a universally applicable model for accurately fitting real-world distributions.

2.1.3. Coverless Steganography

Unlike cost based method or model based method, where a prepared cover object is used to hide data by modifying the pixel values, coverless steganography based on the principle that natural carriers may carry the secret information that both parties want to transmit in secret communication. They do not require to prepare the cover to be modified, but aims to embed information directly within the carrier medium itself, without relying on modifying a distinct cover. Traditional methods achieve this by selecting the image that suitable with the message to be transmitted. With the development of the generative model, recent research proposed to embed the messages in the interim of the image generation or procession.

2.2. Image Style Transfer

Image style conversion methods can be divided into non realistic rendering (Non) Photorealistic Rendering (NPR) method and computer vision method. The NPR method has developed into an important field in the field of computer graphics, but most NPR stylization algorithms are designed for specific artistic styles, not easy to expand to other styles. The method of computer vision regards style transformation as a texture synthesis problem, that is, the extraction and transformation from the source texture to the target texture. The framework of "image analogy" achieves universal style conversion by analogizing learning from examples of provided unshaped and stereotyped images. But these methods only use low-level image patterns.

Physical features cannot effectively obtain advanced image structural features. Inspired by Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Gatys et al. first studied how to use convolutional neural networks to transform natural images into famous painting styles, such as Van Gogh’s Starry Night. They proposed modeling the content of photos as intermediate layer features of pre trained CNNs, and modeling artistic styles as statistics of intermediate layer features.

With the rapid development of style transition networks based on CNN, the efficiency of image style conversion has gradually improved, and image processing software such as Prisma and Deep Forger have become popular, making sending artistic style images on social platforms a common phenomenon. Therefore, covert communication using stylized images as carriers should not be easily suspected. Based on this, this chapter proposes a steganography method for image style transfer, which embeds secret messages while image stylization, making the generated encrypted image indistinguishable from the clean stylized image, improving steganography security and capacity.

3. Proposed Methods

It is shown that deep neural networks can learn to encode a wealth of relevant information by invisible perturbations [

25]. Therefore, we encode the secret information during the process of image style transfer, directly creating a stylized image with hidden secret messages, as opposed to first computing the steganographic cost and then applying encoding methods to the image.

As shown in

Figure 2, the network architecture consists of four parts: 1) a generator

G, which takes the content image and the to-be-embedded message as inputs, simultaneously achieving style transformation and information embedding; 2) a message extractor

E, which trained along with

G and takes the stego image as input and precisely retrieves hidden information; 3) a discriminator

A which is iteratively updated with the generator and extractor; and 4) a style transformer loss computing network

L, which is a pretrained VGG model, it is employed to determine the resulting image’s style and content loss. The whole model is trained by the sender, and when the model is well trained, the message extraction network

E is shared with the receiver to extract secret messages that are hidden in the received image. The implementation details of each part are as follows.

3.1. Generator

In our implementation, we adopt the architecture of image transformation networks in [

44] as the generator

G, it first utilize two stride-2-convolutions to down-sample the input, followed by several residual blocks, then two convolutional layers with stride 1/2 is used to upsample, followed by a stride-1 convolutional layer which uses a

kernel. The Instance Normalization [

48] is added to the start and the end of the network.

Table 1.

Structure of Message Embedding Network.

Table 1.

Structure of Message Embedding Network.

| Network Layer |

Output Size |

| input |

|

| padding() |

|

|

conv, step 1 |

|

| secret message |

|

| message concat |

|

|

conv, step 2 |

|

|

conv, step 2 |

|

| residual block, 128 filters |

|

| residual block, 128 filters |

|

| residual block, 128 filters |

|

| residual block, 128 filters |

|

| residual block, 128 filters |

|

|

conv, step

|

|

|

conv, step

|

|

|

conv, step 1 |

|

To encode secret messages during the image style transfer, we concatenate the message M of size with the output of the first convolutional layer with respect to the input content image of size , and take the resultant tensor as the input of the second convolutional layer, by this way, we obtain a feature map which contains both the secret messages and the input content. The following architecture is like an encoder-decoder, which first combines and condenses the information and then restores an image with the condensed feature. The final output of G is a style-transferred image of size , which also contains secret messages.

3.2. Style Transfer Loss Computing

The resultant images should possess similar content as

, and possess the target style which is defined by a target style image

. For this reason, we apply a loss calculation network

L to quantify in high-level content difference between resultant image and

, style difference between resultant image and

, respectively.

L is implemented as a 16-layer VGG network [

49] which is pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset for image classification task in advance. To achieve style transfer, two perceptual loss are designed, namely content reconstruction loss and style reconstruction loss.

3.2.1. Content Reconstruction Loss

we define the content reconstruction loss as the difference between the activations of intermediate layers of

L with respect to

and

as inputs. The activation maps of the

j-th layer of the network in terms of the input image

x is represented as

, then the content loss is defined as the mean squared error between the activation map of

and

, represented as:

It is shown in [

43] that the high-level content of the image is kept in the responses of the higher layers of the network, while detailed pixel information is kept in the responses of the lower layers. Therefore, we calculate the perceptual loss for style transfer at high layers. It does not require that the output image

perfectly match

, instead, it encourages it to be perceptually similar to

, hence there is extra room for us to implement style transfer and steganography.

3.2.2. Style Reconstruction Loss

To implement style transfer, except for content loss, style reconstruction loss is also required to penalize the differences in style such as colors and textures between

and

when

deviates from the input

in terms of style. To this end, we first define the Gram matrix

to be the matrix of size

, the elements of

are defined as:

To achieve better performance, we calculate the style loss

from a set of layers

J instead of a single layer

j. Specifically,

is defined as the sum of losses for each layer

, as described in Equation (

5).

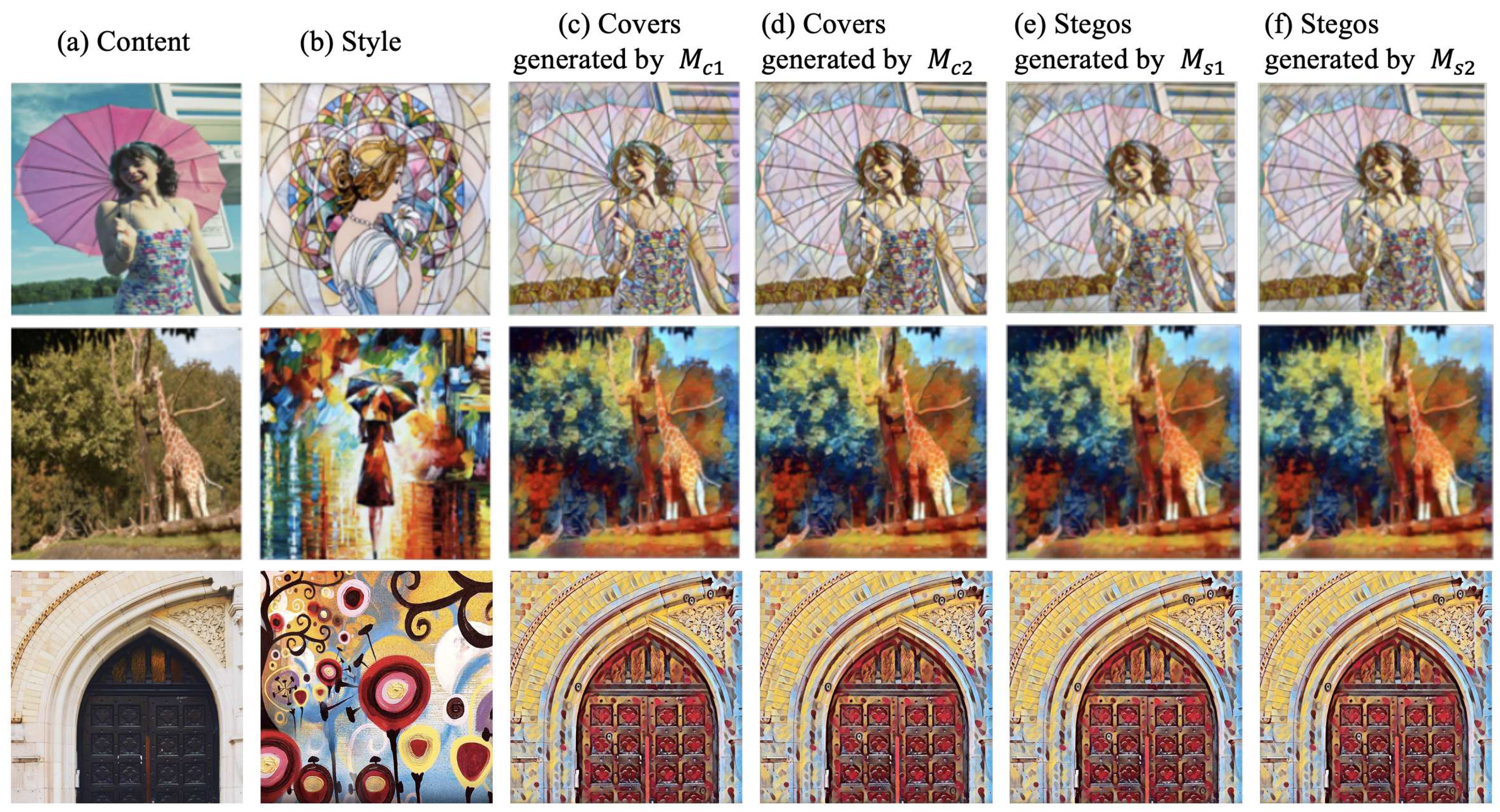

Figure 3.

Comparison of style transferred clean images without steganography (columns (c) and (d)) and style transferred stego images (columns (e) and (f)).

Figure 3.

Comparison of style transferred clean images without steganography (columns (c) and (d)) and style transferred stego images (columns (e) and (f)).

3.3. Extractor

To accurately recover the embedded information, a message extraction network

E which has the same architecture with the generator

G is trained together with

G. It takes the generated image, i.e.,

as the input, and outputs

O of size

, the revealed message

is obtained according to

O:

The loss for information reveal is defined as the mean square error between the embedded message

M and the extracted message

:

When the model is well trained, E is shared between Alice and Bob for convert communication, which plays the role of the secret key. Therefore, it is crucial to keep the secret of the trained E.

Table 2.

Structure of Message Extraction Network.

Table 2.

Structure of Message Extraction Network.

| network layer |

output size |

|

conv, step 1 |

|

|

conv, step

|

|

|

conv, step 1 |

|

| residual block, 128 filters |

|

| residual block, 128 filters |

|

| residual block, 128 filters |

|

| residual block, 128 filters |

|

| residual block, 128 filters |

|

|

conv, step 2 |

|

|

conv, step 2 |

|

|

conv, step 2 |

|

|

conv, step 1 |

|

3.4. Adversary

To enhance the resulting

’s visual quality, adversarial training technique is applied, where SRNet [

19] is applied as a discriminator to classify the generated style-transferred images containing secret messages and clean-styled images generated by a style transfer network without steganography function. The cross-entropy loss is applied to measure the performance of the discriminator, which is defined as Equation (

8).

When updating the generator, the object is to maximize

, while when updating the discriminator the object is to minimize

.

Figure 4.

Comparison of style transferred clean images without steganography (columns (c) and (d)) and style transferred stego images (columns (e) and (f))

Figure 4.

Comparison of style transferred clean images without steganography (columns (c) and (d)) and style transferred stego images (columns (e) and (f))

3.5. Traning

In the training process, we iteratively update the parameters of the generator and adversary. Each iteration contains two epochs, in the first epoch, we fix the parameters of the discriminator unchanged and update the parameters of the first convolution layer, the generator, and the extractor by minimizing the content loss

, style loss

and message extraction loss

but maximizing the discriminator’s loss

, hence the total loss for training is defined as follow:

where

and

are hyper-parameters to balance the content, style, message extraction accuracy, and the risk being detected by the discriminator. In the second epoch, we update the parameters of the adversary by using the loss defined in Equation (

8) while keeping the remaining parameters fixed.

4. Experiments

To verify the efficiency of the suggested approach, we randomly choose a style image from the WikiArt dataset as the target style and randomly take 20,000 content images from the COCO [

50], 10,000 for training and 10,000 for testing. We repeat the experiments 10 times. All the images are resized to

pixels with the channel of 3, and the messages to be embedded are binary data with the size of

, i.e., the payload is set as 1 bit per channel per pixel (bpcpp). In the training, the Adam optimizer is applied and the learning rate is set as

. We train the network for 200 epochs. The performance of the proposed method are evaluated from the two aspects: 1) the accuracy rate of message extraction and 2) the ability to resist steganalysis.

4.1. Message Extraction Accuracy Analysis

We assume the sender and the receiver share the parameters and architecture of extractor, the adversary knows the algorithm for data hiding and can train a model by herself but will obtain mismatched parameters. We explore that in such a situation whether the hidden message can be extracted accurately by the receiver and whether the secret messages could be leaked to the adversary.

We trained five models of the same architecture but with different random seeds, the architecture of them are illustrated in

Figure 2, and the well-trained networks are represented as

respectively. We randomly split the content dataset into two separate sets, one for testing and the other for training. The secret messages to be embedded are randomly generated binary sequences and are reshaped as

. In the testing stage, we extract the hidden messages by using extractors from different trained models. The results are displayed in

Table 3, from which we can infer that the matched extractor can successfully extract the concealed message, and the accuracy rate of the extracted message reaches

99.2%, demonstrating the receiver could accurately recover the messages. But an adversary cannot steal the secret messages hidden by the proposed method since the mismatched extractor can only recover less than 50% messages.

4.2. Security in Resisting Steganalysis

To verify the security of the embedded secret messages, we compare the generated styled stegos with the clean-styled images generated by the style transfer network without steganography [

44]. We train four networks

,

,

, and

.

,

are in the same architecture proposed in this paper but with different parameters,

,

are style transfer networks without steganography [

44]. The generated images are displayed in Fig. 2, where it is clear that the message embedding has no effect on the image visually.

It should be noted that the difference between generated style-transferred stegos and style-transferred images without hidden messages is not only caused by the message embedding but also due to the different parameters of the model, e.g., images generated by

are different from those by

, but are also different from

and

. Thereby it is difficult to tell whether the image is produced by a style-transfer network with steganography function or by another ordinary style-transfer network without steganography. To verify the security of the proposed method, we assume the attacker is trying to distinguish the generated stego from the cover generated by other normal style transfer networks without the steganography function. According to the Kerckhoff principle, we consider a powerful steganalyzer who knows the target style image and all the knowledge of the model (i.e., architecture and parameters) the steganographer used. In this case, the attacker can generate the same stego as the steganographer, taking the generated stegos as positive samples and the covers generated by models as negative samples to train a binary classifier. We apply different steganalysis methods, including using traditional SPAM [

14] and SRM [

15] features to train a classifier, as well as using deep learning methods XuNet [

17] and SRNet [

19]. Similar to steganalysis, we preserve the cover and stego of the same content in the same batch when train of deep learning-based steganalyzer.

Table 4 contains the experimental findings, the average testing error is all about 0.5, confirming the safety of the suggested procedure.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we suggest a high-capacity and safe method for image steganography. We hide secret messages into an art-style image in the process of image generation by a GAN model. It has been verified by experiments that the proposed approach can achieve a high capacity of 1bpcpp, and the generated images cannot be distinguished from the clean image of the same content and style. Though the message recovery accuracy does not achieve 100%, it can be solved by performing error correction coding on secret messages before steganography. We will keep improving the accuracy of message recovery and explore hiding messages in the diffusion-based AIGC model in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Li Li; Funding acquisition, Xinpeng Zhang; Methodology, 296 Li Li and Kejiang Chen; Project administration, Xinpeng Zhang and Guorui Feng; Software, Li Li; 297 Supervision, Xinpeng Zhang; Validation, Kejiang Chen; Visualization, Deyang Wu; Writing – original 298 draft, Li Li; Writing – review editing, Guorui Feng and Deyang Wu

Funding

This work has been partially supported in part by the Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant U22B2047, U1936214, 62302286,and 62376148, and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under the grant No. 2022M722038.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- T. Filler, J. Judas, J. Fridrich, “Minimizing Additive Distortion in Steganography using Syndrome-Trellis Codes”, IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, Vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 920-935, 2011.

- W. Li, W. Zhang, L. Li, H. Zhou and N. Yu, “Designing Near-Optimal Steganographic Codes in Practice Based on Polar Codes,”IEEE Transactions on Communications, vol. 68, no. 7, pp.3948 - 3962, 2020.

- V. Holub, J. Fridrich, “Designing Steganographic Distortion Using Directional Filters”, in Proc. IEEE Workshop on Information Forensic and Security (WIFS), 2012, pp. 234-239.

- V. Holub, J. Fridrich, T. Denemark, “Universal Distortion Function for Steganography in an Arbitrary Domain”, EURASIP Journal on Information Security, pp. 1-13, 2014.

- V. Holub, J. Fridrich, T. Denemark, “Universal Distortion Function for Steganography in an Arbitrary Domain”, EURASIP Journal on Information Security, pp. 1-13, 2014.

- T. Pevný, T. Filler, and P. Bas, “Using high-dimensional image modelsto perform highly undetectable steganography,” in Proc. International Workshop on Information Hiding, 2010, pp. 161–177.

- V. Sedighi, R. Cogranne and J. Fridrich, “Content-Adaptive Steganography by Minimizing Statistical Detectability”, IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 221-234, 2015.

- T. Pevny and A. D. Ker, “Exploring non-additive distortion in steganography,” in Proc. 6th ACM Workshop Inf. Hiding Multimedia Secur., Jun. 2018, pp. 109–114.

- B. Li, M. Wang, X. Li, S. Tan, and J. Huang, “A strategy of clustering modification directions in spatial image steganography,” in IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Security, vol. 10, no. 9, pp. 1905–1917, Sep. 2015.

- T. Denemark and J. Fridrich, “Improving steganographic security by synchronizing the selection channel,” in Proc. 3rd ACM Workshop Inf. Hiding Multimedia Secur. (IH & MMSec), Jun. 2015, pp. 5–14.

- W. Li, W. Zhang, K. Chen, W. Zhou, and N. Yu, “Defining joint distortion for JPEG steganography,” in Proc. 6th ACM Workshop Inf. Hiding Multimedia Secur., Jun. 2018, pp. 5–16.

- J. Kodovský, J. Fridrich, and V. Holub, “Ensemble classifiers for steganalysis of digital media,” in IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Security, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 432–444, Apr. 2012.

- V. Holub and J. Fridrich, “Low-complexity features for JPEG steganalysis using undecimated DCT,” in IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Security, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 219–228, Feb. 2015.

- B. Li, Z. Li, S. Zhou, S. Tan, and X. Zhang, “New steganalytic features for spatial image steganography based on derivative filters and threshold LBP operator,” in IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Security, vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 1242–1257, May 2018.

- J. Fridrich and J. Kodovsky, “Rich models for steganalysis of digital images,” in IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Security, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 868–882, Jun. 2012.

- Y. Qian, J. Dong, W. Wang, and T. Tan, “Deep learning for steganalysis via convolutional neural networks,” in Proc. SPIE, vol. 9409, Mar. 2015, Art. no. 94090J.

- G. Xu, H. Z. Wu, Y. Q. Shi, “Structural design of convolutional neural networks for steganalysis”, in IEEE Signal Processing Letters, vol. 23, no.5, pp. 708-712, 2016.

- J. Ye, J. Ni, and Y. Yi, “Deep learning hierarchical representations for image steganalysis”, in IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Security, vol. 12, no. 11, pp. 2545–2557, Nov. 2017.

- M. Boroumand, M. Chen, J. Fridrich. “Deep residual network for steganalysis of digital images,” in IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, vol. 14, no.5, pp. 1181-1193, 2018.

- J. Butora, Y. Yousfi, J. Fridrich, “How to Pretrain for Steganalysis,” in Proc. 9th IH& MMSec. Workshop, Brussels, Belgium, June 22-25, 2021.

- D. Volkhonskiy, I. Nazarov, B. Borisenko and E. Burnaev, “Steganographic generative adversarial networks,” in Twelfth International Conference on Machine Vision (ICMV 2019) (Vol. 11433, p. 114333M). International Society for Optics and Photonics.

- H. Shi, J. Dong, W. Wang, Y. Qian and X. Zhang, “SSGAN: secure steganography based on generative adversarial networks,” in Pacific Rim Conference on Multimedia, 2017, pp.534-544.

- J. Hayes and G. Danezis, “Generating steganographic images via adversarial training,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.00371, 2017.

- D. Hu, L. Wang, W. Jiang, S. Zheng and B. Li, “A novel image steganography method via deep convolutional generative adversarial networks,” IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 38303-38314, 2018.

- J. Zhu, R. Kaplan, J. Johnson and F. F. Li, “Hidden: hiding data with deep networks,” in Proc. ECCV, 2018, pp. 657-672.

- W. Tang, S. Tan, B. Li and J. Huang, “Automatic steganographic distortion learning using a generative adversarial network,” IEEE Signal Processing Letters, vol. 24, no. 10, pp. 1547-1551, 2017.

- J. Yang, K. Liu, X. Kang, E. K. Wong and Y. Shi, “Spatial image steganography based on generative adversarial network,” arXiv:1804.07939, 2018.

- A. Rehman, R. Rahim, M. Nadeem and S. Hussain, “End-to-end trained CNN encode-decoder networks for image steganography,” in Proc. Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) Workshops, 2018, pp. 723-729.

- S. Baluja, “Hiding images in plain sight: deep steganography,” in Proc. Neural Information Processing Systems, 2017, pp. 2069-2079.

- R. Zhang, S. Dong and J. Liu, “Invisible steganography via generative adversarial networks.” Multimedia Tools and Applications, vol. 78, no. 7, pp. 8559–8575, 2019.

- K. Zhang, A. Cuesta-Infante, L. Xu and K. Veeramachaneni, “SteganoGAN: high capacity image steganography with GANs,” arXiv:1901.03892, 2019.

- J. Tan, X. Liao, J. Liu, Y. Cao and H. Jiang, “Channel Attention Image Steganography With Generative Adversarial Networks,” in IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 888-903, 1 March-April 2022.

- W. Tang, B. Li, B. Mauro, et al. “An automatic cost learning framework for image steganography using deep reinforcement learning,” in IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, vol. 16, pp. 952-967, 2020.

- Z. Guan, J. Jing, X. Deng, et al. “DeepMIH: Deep invertible network for multiple image hiding,” in IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2022, 45(1): 372-390.

- C. Yu, “Attention based data hiding with generative adversarial networks,” in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 2020, 34(01): 1120-1128.

- Ramesh A, Dhariwal P, Nichol A, et al., “Hierarchical text-conditional image generation with clip latents,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.06125, 2022, 1(2): 3.

- Rombach R, Blattmann A, Lorenz D, et al., “High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2022: 10684-10695.

- Bui T, Agarwal S, Yu N, et al., “RoSteALS: Robust Steganography using Autoencoder Latent Space,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2023: 933-942.

- Yu J, Zhang X, Xu Y, et al., “CRoSS: Diffusion Model Makes Controllable, Robust and Secure Image Steganography,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.16936, 2023.

- I. Prisma Labs, “Prisma: Turn memories into art using artificial intelligence,” 2016. [Online]. Available:. Available online: http://prisma-ai.com.

- “Ostagram,” 2016. [Online]. Available:. Available online: http://ostagram.ru.

- A. J. Champandard, “Deep forger: Paint photos in the style of famous artists,” 2015. [Online]. Available:. Available online: http://deepforger.com.

- L. A. Gatys, A. S. Ecker, M. Bethge, “A neural algorithm of artistic style”. arXiv preprint arXiv:1508.06576, 2015.

- J. Johnson, A. Alahi, F. Li, “Perceptual losses for real-time style transfer and super-resolution” in European conference on computer vision, 2016, pp. 694-711.

- X. Huang, S. Belongie. “Arbitrary style transfer in real-time with adaptive instance normalization” in Proc. IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 2017, pp. 1501-1510.

- Zhong N, Qian Z, Wang Z, et al. Steganography in stylized images[J]. Journal of Electronic Imaging, 2019, 28(3): 033005-033005.

- Z. Wang, N. Gao, X. Wang, et al. “STNet: A Style Transformation Network for Deep Image Steganography”, in International Conference on Neural Information Processing, 2019, pp. 3-14.

- X. Huang, S. Belongie, “Arbitrary style transfer in real-time with adaptive instance normalization,” in Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision. 2017: 1501-1510.

- K. Simonyan, A. Zisserman, “Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition”, arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556, 2014.

- T. Y. Lin, M. Maire, S. Belongie, et al. “Microsoft coco: Common objects in context,” in Computer Vision–ECCV, 2014: 740-755.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).