Submitted:

09 January 2024

Posted:

10 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Experiments

2.1. Materials

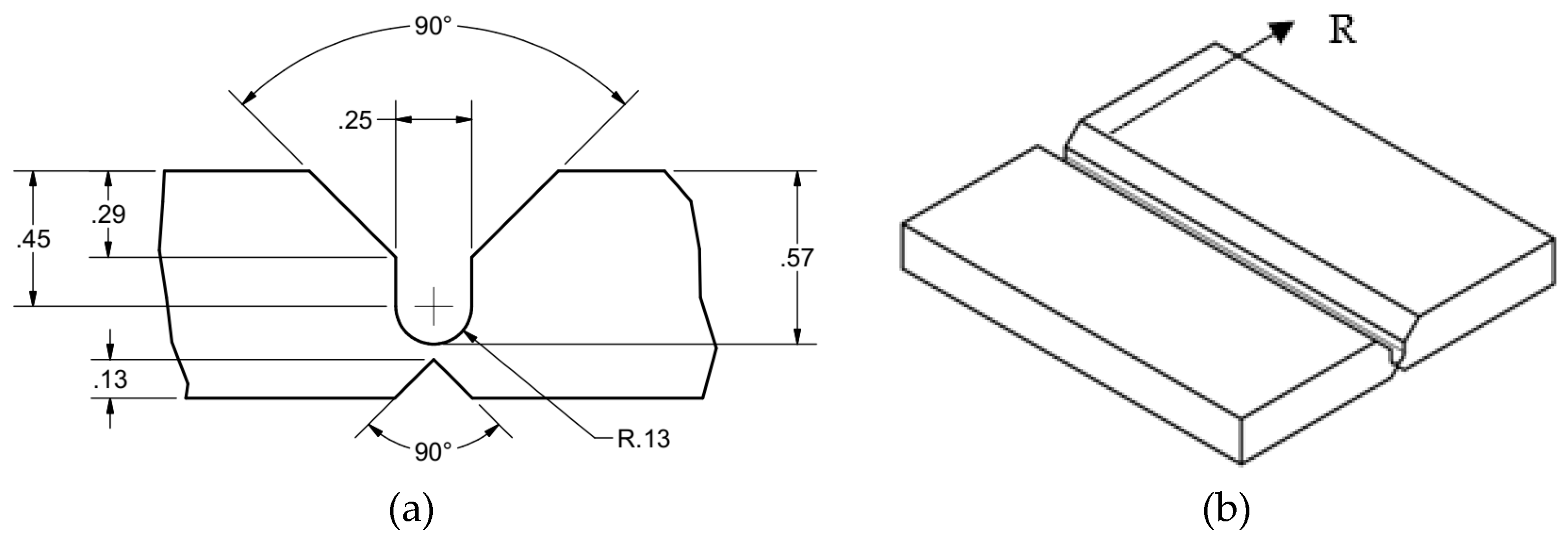

2.2. Welding process and specimen fabrication

2.3. Hardness measurement

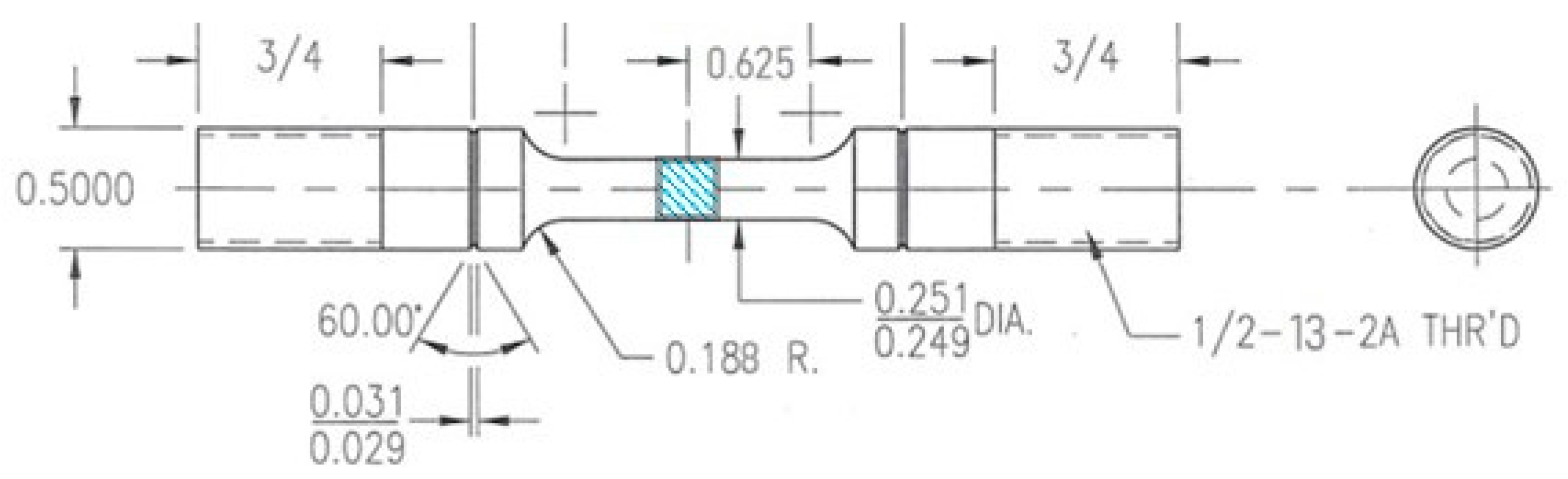

2.4. High temperature tests

2.5. Microstructure examination

3. Results

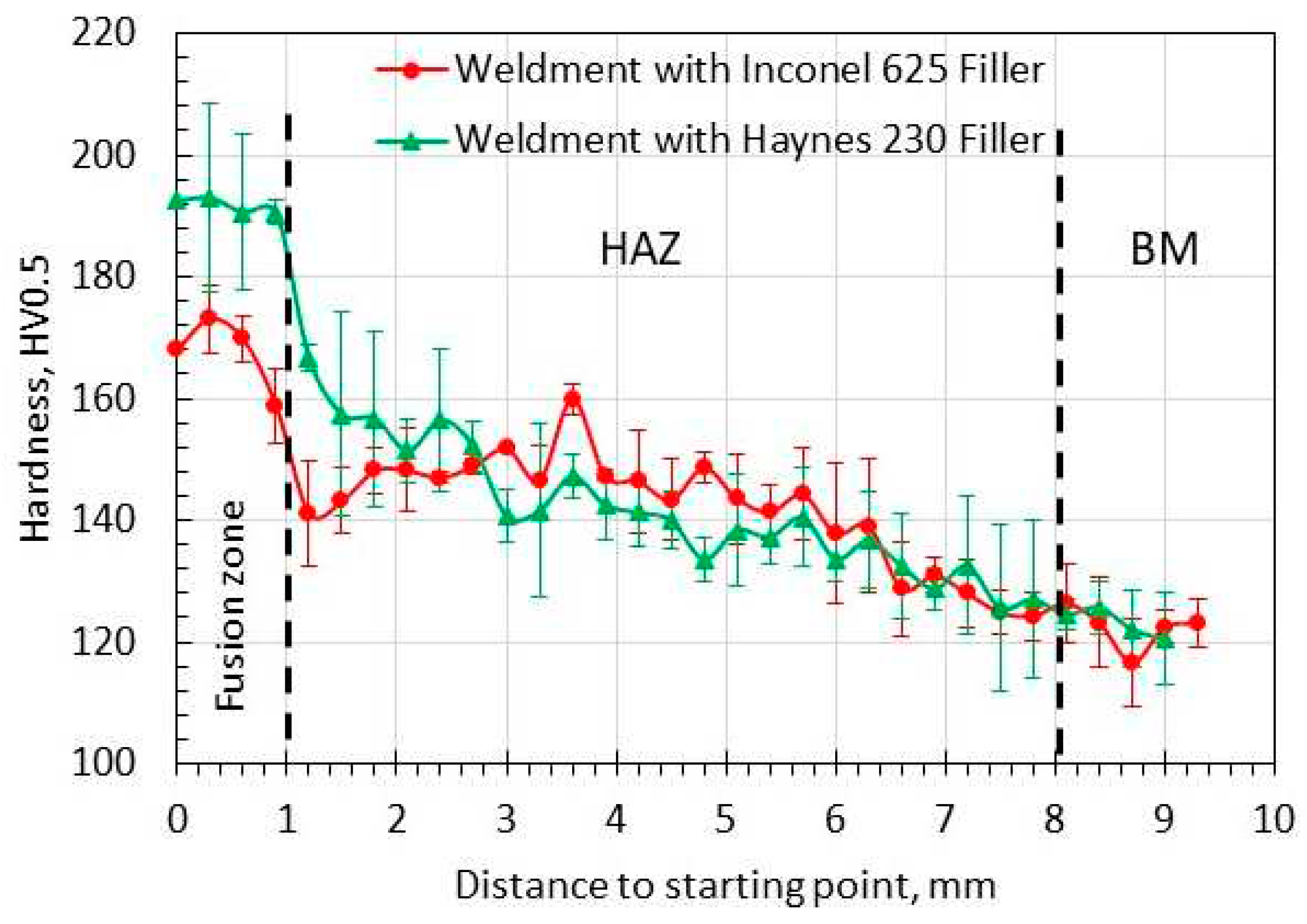

3.1. Hardness

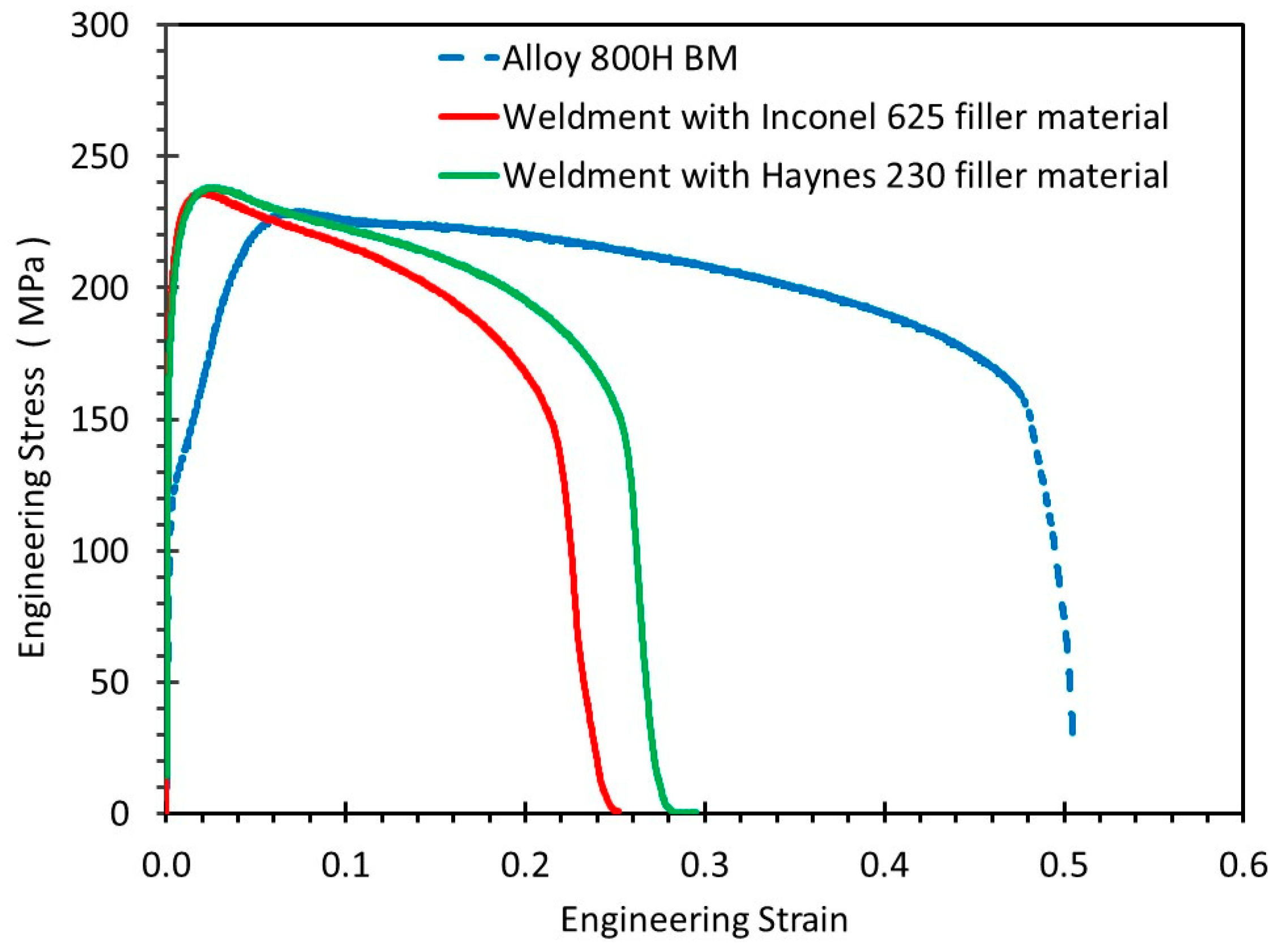

3.2. High temperature tensile test

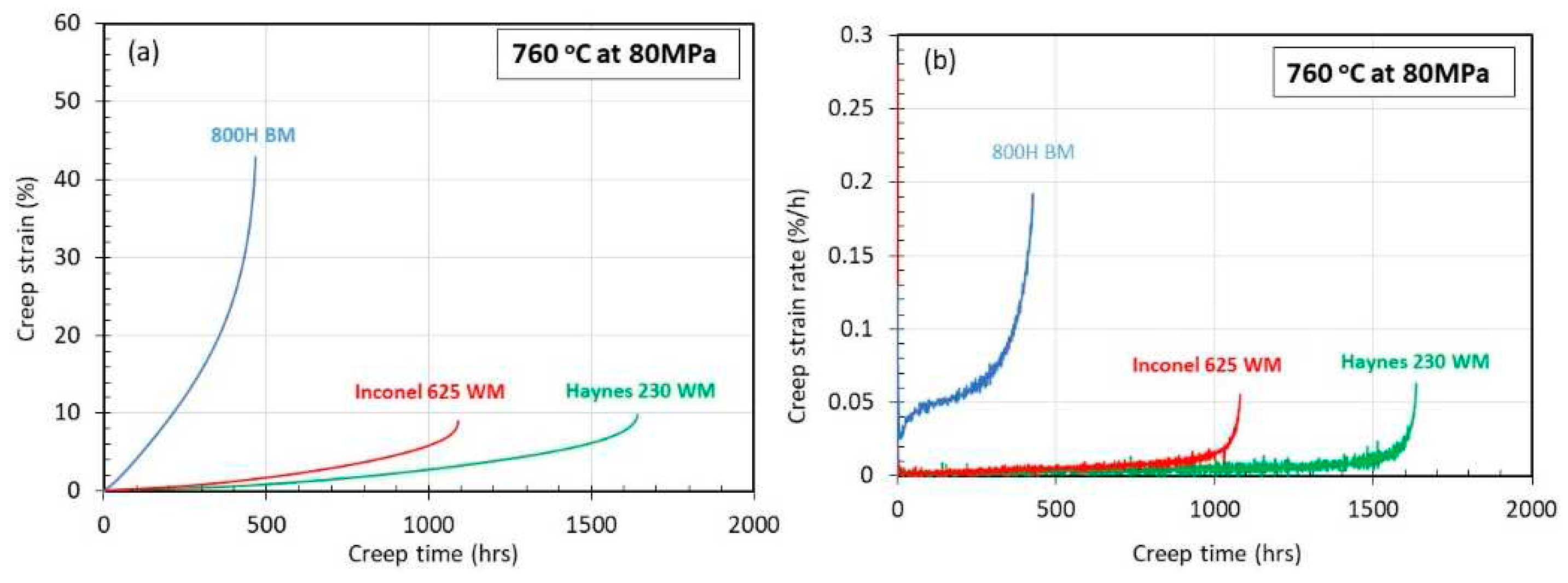

3.3. High temperature creep test

3.4. Microstructures

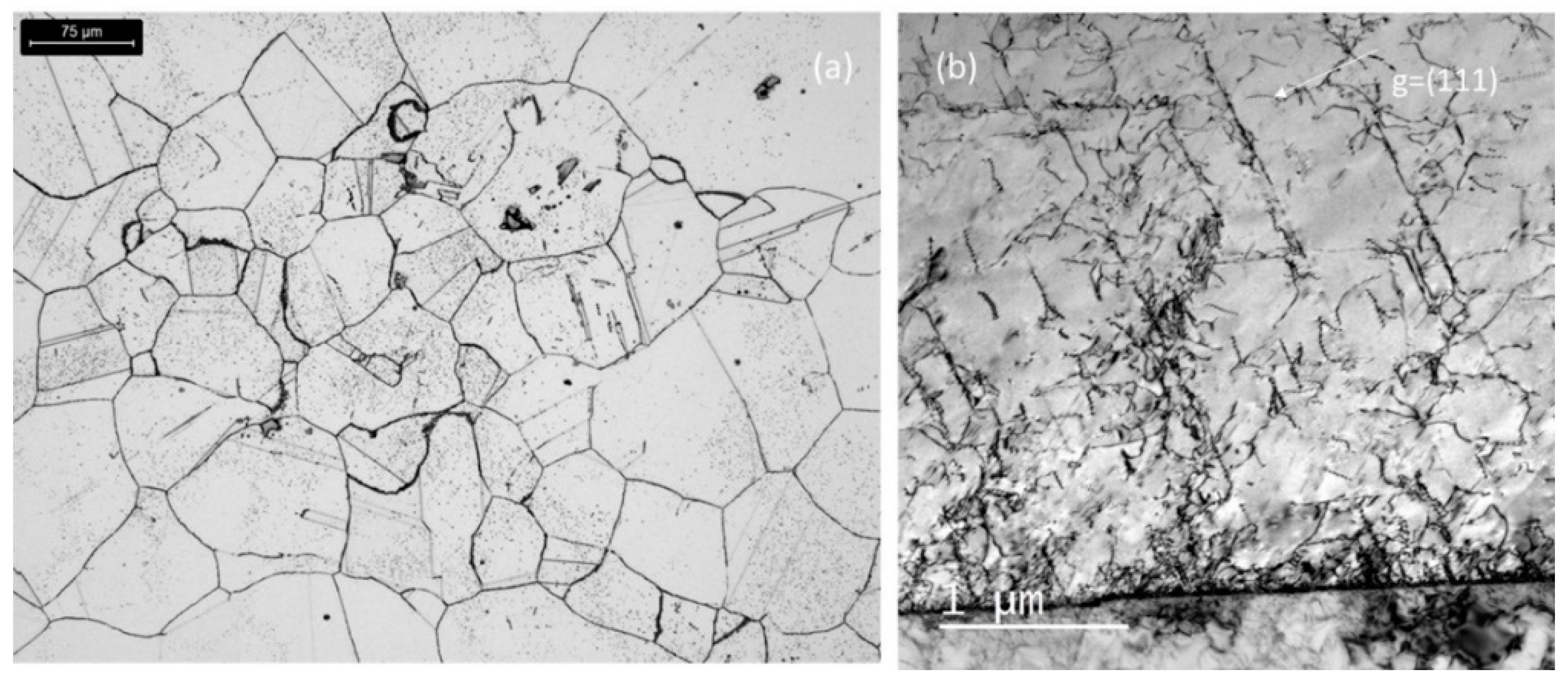

3.4.1. As-received Alloy 800H base metal

3.4.2. As-welded microstructure

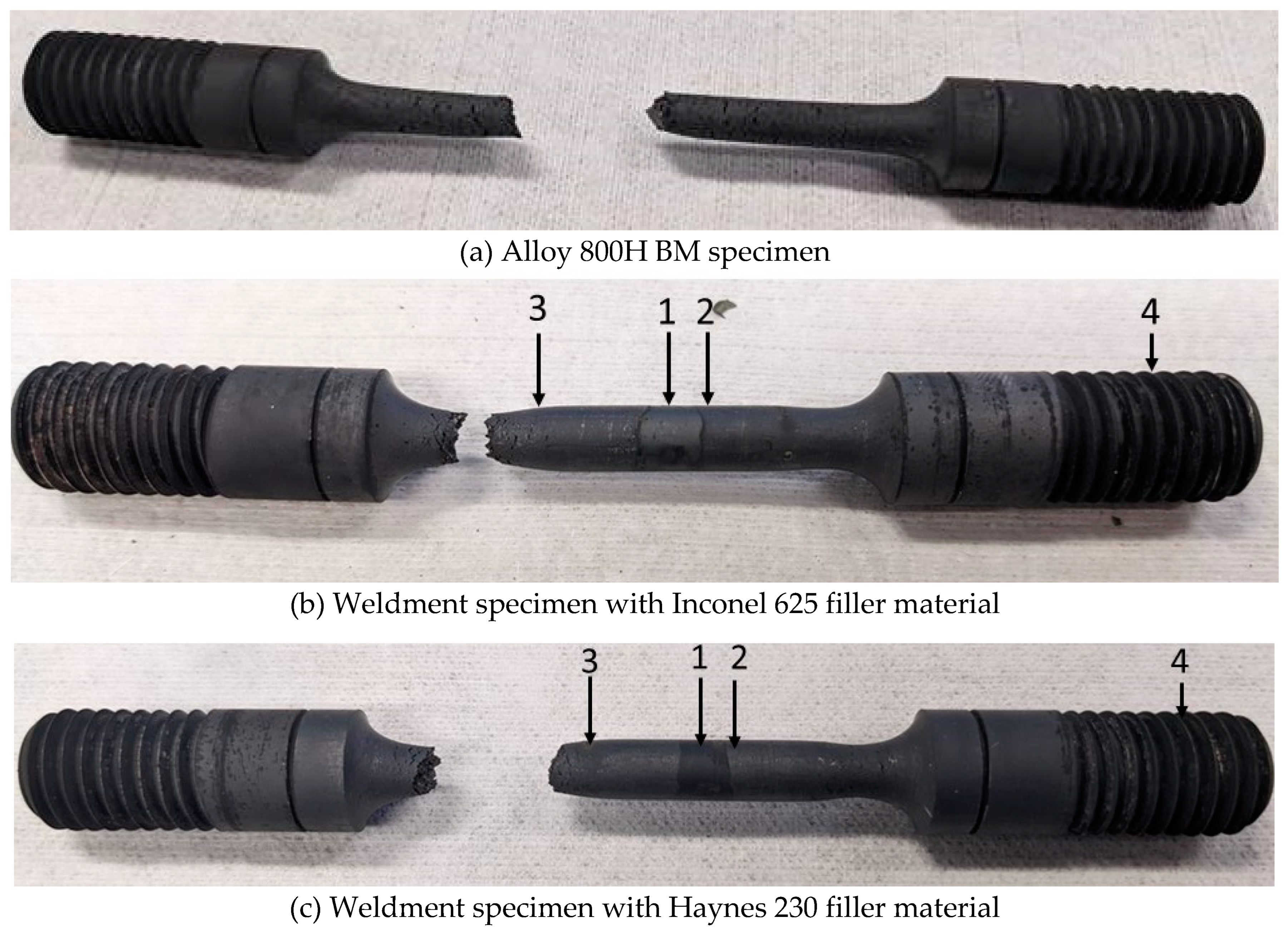

3.4.3. Microstructure after creep rupture

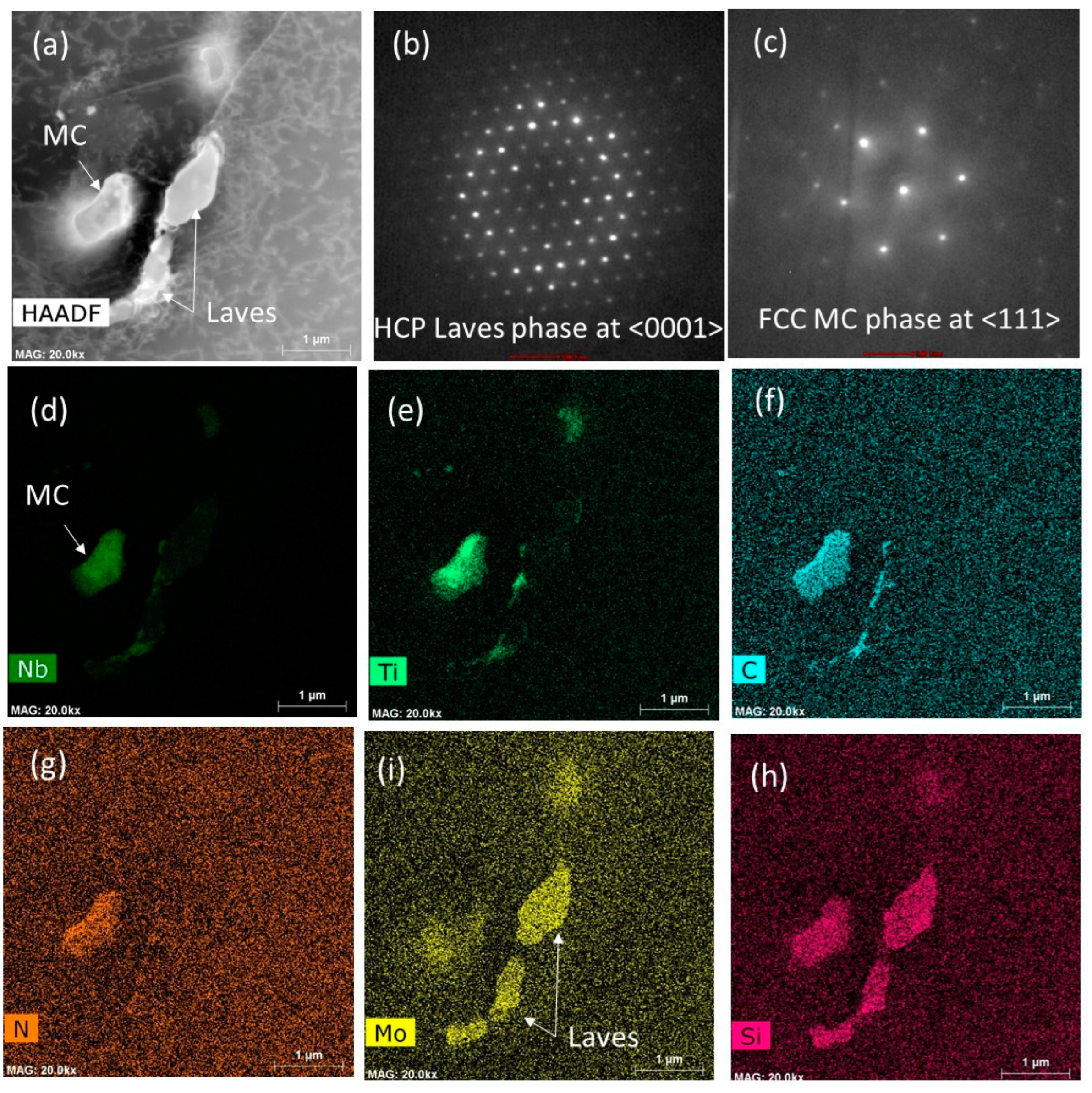

3.4.3.1. FZ of Inconel 625 and Haynes 230 filler specimens (Region 1 in Figure 6)

3.4.3.2 HAZ adjacent to fusion boundary (Region 2 in Figure 6)

3.4.3.3. Base metal close to rupture surface (Region 3 in Figure 6)

3.4.3.4. High-temperature ageing structure in Incoloy 800H (Region 4 in Figure 6)

3.4.3.5. Fractography

4. Discussion

4.1. High temperature creep deformation and mechanisms

4.2. Precipitate evolution during high temperature creep

5. Conclusions

- -

- High temperature apparent tensile yield strength and creep resistance of Incoloy 800H welds at 80 MPa and 760 oC were significantly enhanced by adding Inconel 625 and Haynes 230, into the Alloy 800H weldments. Both of the weldments showed longer creep rupture time but lower rupture strain compared with the BM specimen.

- -

- Significant dislocation slip and interaction with precipitates were observed in the microstructure, indicating the high temperature power-law creep mechanism. Dislocation bypassing through the Orowan mechanism accompanying with climb and cutting facilitated dislocation slips during high temperature creep deformation.

- -

- Microstructural characterization revealed extensive precipitation took place after the prolonged creep testing at high temperature. A large number of sub-micron sized carbides (MC and M23C6) were observed in the microstructure of FZ, HAZ adjacent to fusion boundary and base metals under various conditions (as-received, as-welded and creep tested). The varied sizes and locations of the M23C6 and MC carbides suggest a complex microstructural evolution during the creep test.

- -

- The weldment with Inconel 625 filler weldments exhibited detrimental δ and Laves phase in the weld metal after creep test. Although the failure occurred in the base metal rather than in the fusion zone under the current test condition, the presence of these phase could cause potential crack initiation after prolonged high temperature ageing.

- -

- The weldment with Haynes 230 filler material demonstrated superior phase stability and improved creep rupture properties compared to the one with Inconel 625 filler material. This suggests that Haynes 230 could be a promising filler material for further investigations in Alloy 800H application.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- W. Ren and R. Swindeman, Status of Alloy 800H in Considerations for the Gen IV Nuclear Energy Systems, Journal of Pressure Vessel Technology, Vol 136, October 2014, 054001-1. [CrossRef]

- K. Natersan, A. Purohit and S.W. Tam, Materials Behavior in HTGR Environments, NUREG/CR-6824 ANL-02/37, Argonne National Laboratory, July 2003.

- P. Simon, NGNP High Temperature Materials White Paper. INL/EXT-09-17187, Idaho National Laboratory, 2010.

- ASME Standard, an International Code: 2019 ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code, Section III, Rules for Construction of Nuclear Facility Components, Division 5 High Temperature Reactors, 2019 July 1.

- J.R. Lindgren, B.E. Thurgood, R.H. Ryder and C.C. Li, Mechanical Properties of Welds in Commercial Alloys for High-Temperature Gas-Cooled Reactor Components, Nuclear Technology, 66 (1984)(1) 207-213. [CrossRef]

- W. Ren, T. Totemeier, M. Santella, R. Battiste and D.E. Clark, Status of Testing and Characterization of CMS Alloy 617 and Alloy 230, ORNL/TM-2006-547, August 31, 2006.

- J. W. York and R. L. Flury, Assessment of Candidate Weld Metals for Joining Alloy 800, Sub 4308-2, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 1976 February.

- D.B. Roach and J. A. Vanecho, Creep Rupture Properties of HK-40 and Alloy 800 Weldments, Corrosion/81, Toronto, Ontario, April 1981, Paper 238.

- R.E. Rupp, T. Leung Sham, An Initial Assessment of the Creep-Rupture Strengths for Weldments with Alloy 800H Base Metal and Alloy 617 Filler Metal, Proceedings of the ASME 2022, Pressure Vessels & Piping Conference (PVP 2022), July 17-22, 2022, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA.

- H.M. Tawancy, D.L. Klarstrom and M.F. Rothman, Development of a New Nickel-Base Superalloy, Journal of Metals, 36 (1984)(9) 58-62. [CrossRef]

- S. Hastuty, P. Zacharias, M. Awwaluddin, P.H. Setiawan, E. Siswanto, B. Santoso, A. Nugroho and A.M. AbdulRani, Considerations of Material Selection for Control Rod Drive Mechanism of Reaktor Daya Eksperimental, Journal of Physics: Conf. Series 1198 (2019) 032010. [CrossRef]

- Kreitcberg, K. Inaekyan, S. Turenne and V. Brailovski, Temperature- and Time-Dependent Mechanical Behavior of Post-Treated IN625 Alloy Processed by Laser Powder Bed Fusion, J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2019, 3, 75;. [CrossRef]

- https://www.haynesintl.com/alloys/alloy-portfolio_/High-temperature-Alloys/HAYNES-230-ALLOY/nominal-composition.

- https://www.specialmetals.com/documents/technical-bulletins/inconel/inconel-alloy-625.pdf.

- ASTM International. “Standard Test Methods for Conducting Creep, Creep-Rupture, and Stress-Rupture Tests of Metallic Materials.” E139-11 (Reapproved 2018). ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA (2018).

- M.K. Booker, Analysis of the Creep Strain-Time Behaviour of Alloy 800, ORNL/TM-8449.

- E. Orowan, Zur Kristallplastizität. III, Z. Phys. 89 (9) (1934) 634–659. [CrossRef]

- A.L. Beardsley, C.M. Bishop and M.V. Kral, A Deformation Mechanism Map for Incoloy 800H Optimized Using the Genetic Algorithm, Metal. Mater. Trans. A, 50 (2019) 4098-4110. [CrossRef]

- 19. Z. Bai and Y. Fan, Abnormal strain rate sensitivity driven by a unit dislocation-obstacle interaction in BCC Fe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120 (2018) 125504. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhao, J. Gong, A. Saboo, D.C. Dunand and G.B. Olson, Dislocation-Based Modeling of Long-Term Creep Behaviors of Grade 91 Steels. Acta Mater. 149 (2018) 19–28. [CrossRef]

- M. Kabir, T.T. Lau, D. Rodney, S. Yip and K.J. Van Vliet, Predicting Dislocation Climb and Creep from Explicit Atomistic Details. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, (2010) 095501. [CrossRef]

- L. Li, F. Liu, L. Tan, Q. Fang, P.K. Liaw and J. Li, Uncertainty and statistics of dislocation precipitate interactions on creep resistance, Cell Reports Physical Science, Vol 3, Issue 1, January 19, 2022 . [CrossRef]

- W.D. Callister Jr., Materials Science and Engineering-An Introduction, 5th ed, John Wiley&Sons, Inc., 1999.

- K. Spiradek, H.P. Degischer and H. Lahodny, Correlation between Microstructure and the Creep Behaviour at High Temperature of Alloy 800H, CONF-8806156: IAEA Specialists Meeting on High-temperature Metallic Materials for Gas-cooled Reactors, Cracow (Poland), 20-23 June 1988. https://inis.iaea.org/collection/NCLCollectionStore/_Public/21/068/21068264.pdf?r=1&r=1.

- M.E. Kassner and T.S. Hayes, Creep Cavitation in Metals, International Journal of Plasticity, 19 (2003) 1715-1748. [CrossRef]

- C. Jang, D. Lee and D. Kim, Oxidation Behavior of Alloy 617 in Very High Temperature Air and Helium Environments, Int. J. Press. Vessels Piping 85 (2008) 368-377. [CrossRef]

- S. Floreen, G.E. Fuchs and W.J. Yang, The Metallurgy of Alloy 625. https://www.tms.org/superalloys/10.7449/1994/Superalloys_1994_13_37.pdf.

- J.N. DuPont, C.V. Robino and A.R. Marder, Solidification of Nb-Bearing Superalloys: Part II. Pseudo Ternary Solidification Surfaces, Metallurgical and Material Transactions A, 29A (1998) 2797-2806. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Cieslak, T. J. Headley, T. Kollie and A. D. Romig, Solidification of An Alloy 625 Weld Overlay, Met Trans. A, 19A, (1988) 2319-2331.

| Element | Fe | Ni | Cr | Mo | Nb | Co | Mn | C | Al | Ti | Si | B | W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR Alloy 800H | 45.6 | 30.3 | 20.6 | 0.7 | - | 0.05 | 0.7 | 0.08 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.4 | - | - |

| Inconel 625 | <5.0 | >58.0 | 20.0~23.0 | 8.0~10.0 | 3.15~4.15 | <1.00 | <0.50 | <0.10 | <0.40 | <0.40 | <0.50 | - | - |

| Haynes 230 | <3.0 | 57.0 Bal | 22.0 | 2.0 | <0.50 | <5.00 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.30 | <0.10 | 0.40 | <0.015 | 14.0 |

| Material | Minimum strain rate (h-1) |

Stain at Rupture (%) |

Time to tertiary stage(hours), Tt | Time to Rupture (hours), TR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incoloy 800H BM | 10-4 | 44.96 | 60 | 467 |

| Weldment with Inconel 625 FM | 10-5 | 9.66 | 320 | 1091 |

| Weldment with Haynes 230 FM | 10-5 | 10.51 | 456 | 1643 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).