1. Introduction

The olive oil processing industry produces large amounts of liquid wastewaters, known as olive mill wastewaters (OMWs): their disposal without any treatment generates serious environmental problems including colouring of natural waters, contamination of underground water, phytotoxicity and bad odours. The annual worldwide production of OMWs is estimated to be of about 1x10

7 m

3, most of which are produced in the Mediterranean area [

1].

OMWs appear as dark liquid effluents with an acid reaction: the pH, immediately after their production, is in the range 4.5 and 5.9 [

2] and depends on the aging of the olives and the wastewaters, due to oxidative processes catalyzed by various bacterial species. Their physico-chemical characteristics can vary widely in relation to several factors such as climatic conditions and cultivar, extraction methodology, type and maturity of olives extraction and processing methods [

3]. The pollution load of OMWs is essentially related to their high content of organic substances and phenols. Chemical oxygen demand (COD) and corresponding biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) can reach values of up 220 g L

-1 and 100 g L

-1, respectively [

4]. Phenolic compounds, ranging from 0.5 to 24 g L

-1, are responsible for phytotoxicity and high resistance of OMWs to biodegradation. On the other hand, these compounds have been recognized to exhibit a wide array of biological activities such as antioxidant, free radical scavenging, anti-inflammatory, anticarcinogenic and antimicrobial activities [

5]. As a consequence, they can be exploited to be used as natural additives of foodstuff for the production of dietary supplements and nutraceuticals due to their ability to provide advanced technological properties and health claims, respectively [

6,

7,

8].

Current research trends aim at developing technological and biotechnological applications for the recovery of fine chemicals from OMWs and the production of important metabolites, respectively. This approach, in line with the principles of circular economy, aims at closing the production loop by recycling and reusing resources, bringing benefits to the environment, society and economy [

9].

The high quantities of COD and BOD present in OMW constitute a major problem, both for disposal and for the recovery of polyphenols, which would become much easier if the large percentage of suspended mucilage had been preliminarily separated. The adoption of a staged filtering process for OMW purification therefore appears very promising, using filtration methodologies which are notoriously cost-effective technologies for removing dissolved and suspended elements from water [

10,

11].

Membrane processes have been remarkably grown over the last decades as efficient tools to improve the valorisation protocols of agro-food wastewaters and by-products within a sustainable biorefinery strategy [

12]. These processes offer several advantages over conventional separation methodologies, thanks to their intrinsic properties including mild operating conditions of temperature and pressure, simple equipment, easy scale-up and scale-down, low energy consumption, non-use of chemicals and high selectivity towards specific compounds [

13,

14].

Membrane processes have been largely investigated in the past in order to produce effluents of acceptable quality from OMWs for safe disposal into the environment [

15,

16]. Several valorization approaches have been also proposed through the combination of membrane-based operations in a sequential design in order to recover, fractionate and concentrate phenolic compounds from these effluents [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Most of these studies are focused on the use of pressure-driven membrane operations such as microfiltration (MF), ultrafiltration (UF), nanofiltration (NF) and reverse osmosis (RO). In particular, MF and UF processes are mainly used as a pretreatment step to produce a clarified effluent enriched in phenolic compounds and free of suspended solids [

21,

22]. NF and RO processes are used as intermediate or final steps for purification and concentration purposes [

23]. All these processes meet the requirement for the recovery, purification and concentration of polyphenols from OMWs with regard to their specific molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) values. However, the performance of MF and UF membranes is remarkably affected by fouling phenomena which determine both decrease of membrane productivity (permeate flux) and variation of membrane selectivity. Fouling also reduces the membrane service lifetime making the process economically unfeasible [

24,

25]. In the sequential process investigated by Russo [

26], based on the use of MF, UF and RO membranes, the pretreatment of raw OMWs by MF was considered the critical step of the overall process due to irreversible fouling phenomena of both polymeric and ceramic membranes investigated. Similar results were obtained by Cassano et al. [

20] in the pretreatment of raw OMWs with hollow fiber UF membranes with pore size of 0.02 μm. These membranes showed higher fouling indexes (93.6%) if compared with those of UF and NF membranes (21.1 and 20.0%, respectively) used in the following steps.

Turano et al. [

27] obtained a significant improvement of the permeate flux in the UF of OMWs previously submitted to a centrifuge treatment at 4000 rpm. However, UF membranes resulted severely fouled by organic compounds and minerals present in OMWs even in presence of this pretreatment. Pre-treatment approaches before membrane operations based on either filtration through a 50 μm filter, flocculation eventually combined with photocatalysis and aerobic treatment, have been also reported [

16,

28].

The global results confirm that the implementation of MF and UF in the pre-treatment step of OMWs is still limited by the high fouling potential of the membranes. Therefore, research efforts look at identifying tailored and cost-effective pretreatments for OMW management.

A recently patented methodology [

29] for OMW purification involves the following three stages: i) OMW acidification to a pH of 3.5 and decantation of the same for one day; ii) water filtration, for the elimination of suspended solid particles, by using a filter, made in situ by depositing a layer of straw dust (size of particles around 500 μm) above a supporting technical sheet; iii) further filtration of the resulting permeate on a nanomembrane filter.

The possibility of using a filter made of powdered natural plant material, such as ground straw, in OMW purification processes would have the following advantages. Apart from the low cost of the starting material, generally available in the agricultural world very close to oil mills, there would be several interesting possibilities for recycling the composite made up of the filtered material and the filter itself. The composite of the two materials could be recycled in composting systems and directly used in the fertilization of olive groves, or once dried it could be tested as manure by livestock farms.

The current investigation aims at evaluating for the first time the performance of straw filtration as primary treatment option in OMW purification (as alternative to microfiltration or ultrafiltration operations) and its combination with NF as an innovative, simple and economical approach to reduce the pollution load of OMWs and, at the same time, to obtain concentrated fractions of phenolic compounds of interest for the development of nutraceutical formulations. Three commercial flat-sheet NF membranes with MWCO in the range of 150-500 Da were tested to concentrate the clarified wastewater produced after straw filtration. Their performance was evaluated in terms of productivity and selectivity towards total polyphenols, flavanols, hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives, COD and total antioxidant activity (TAA).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Olive mill wastewaters and pre-treatment

Olive mill wastewaters (OMWs) obtained from a 3-phase centrifugation process were supplied by Coll.J.A. Società Cooperativa, located in San Giorgio Albanese (Cosenza, Italy). Their initial pH (about 4.8) was adjusted up to 3.5 by adding sulphuric acid at 98% (from Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) in order to achieve the coagulation and precipitation of suspended solids according to the Stokes law. After acidification the raw wastewaters were submitted to decantation at room temperature for at least 24 hours.

2.2. Straw filtration experiments

The filtering apparatus consists of a vertical stainless steel cylinder 70 cm long and 16 cm in diameter. A perforated metal plate, supporting a 120 μm pore nylon fabric, internally divides the cylinder into two equal chambers. A stainless steel funnel, housed in the lower chamber, was welded under the plate so that its terminal parts tand 10 cm from the bottom of the cylinder. The latter is equipped with two access points controlled by hydraulic valves: one downstream the filtering plate for the vacuum line (

Figure 1a), and the other at the bottom of the cylinder for filtered water discharge (

Figure 1b).

The vacuum, in the lower part of the filtering cylinder, was created by a vacuum pump (Elnor Motors, Haacht, Belgium). Twice ground straw, lying on the microporous nylon fabric, was used as a filtering material. A low-speed granulator (SG-1621-CE, Shini Plastics Technologies, New Tapei, Taiwan) was used to obtain a straw fine powder with a particle size of about 500 μm; a further size reduction at 250 and 120 μm was obtained by using a Retsch™ ZM 200 Model Ultra-Centrifugal mill (Retsch GmbH, Haan, Germany).

The packing of the plant-based filter was made by placing 100 g of water soaked grinded straw on the nylon support fabric followed by filter compaction through liquid suction. Experiments were performed by filtering the acidified and decanted vegetation water (about 1 liter for each experiment) through straw filters of different granulometry (120, 250 and 500 μm).

The straw filters were previously washed with water acidified at a pH of 3.5, in order to remove possible soluble components, which could be released by the filter during the filtration process. After filtration the pH of clarified wastewaters was adjusted at a pH of about 5.5 by adding marble powder supplied by local marble factories.

2.3. Nanofiltration experiments

Nanofiltration (NF) experiments were performed according to a dead-end configuration by using a Sterlitech TM HP 4750 high pressures stirred cell (Sterlitech, Kent, WA, USA) with a filter area of 13.85 cm

2 and a processing capacity of 300 mL. A nitrogen cylinder, equipped with a two-stage pressure regulator, was connected to the top of the stirred cell to supply the desired pressure for filtration experiments. The cell filtration system was equipped with flat-sheet membranes whose characteristics are reported in

Table 1. The experiments were performed at an applied pressure of 20 bar and an operating temperature of 24 ± 2 °C. Stirring inside the cell was accomplished by using a magnetic stirrer. An initial volume of filtered OMW of 150 mL was used and the permeate was collected separately up to a final volume of 50 mL, corresponding to a volume concentration factor (VCF) of 3.

The permeate flux (

J), expressed as L/m

2h, was determined by measuring the permeate volume collected in a given time according to Equation (1):

where

Vp (L) is the permeate volume,

t (h) is the permeation time and

A (m

2) is the membrane area. Normalized flux was determined by dividing the flux at a specific time (

J) by the initial flux (

J0), providing the percentage of the original flux that was preserved.

The rejection rate (

R) of a specific compound was calculated as described in Equation (2):

where

Cp and

Cf refer to the solute concentration in permeate and feed samples, respectively.

After the treatment with the clarified wastewaters, the selected membranes were washed with water for 15 min and then submitted to a cleaning with an enzymatic solution (1% w/w Ultrasil 50) at 40 °C for 60 min. After that membranes were rinsed with distilled water for 15 min and the hydraulic permeability was measured once again.

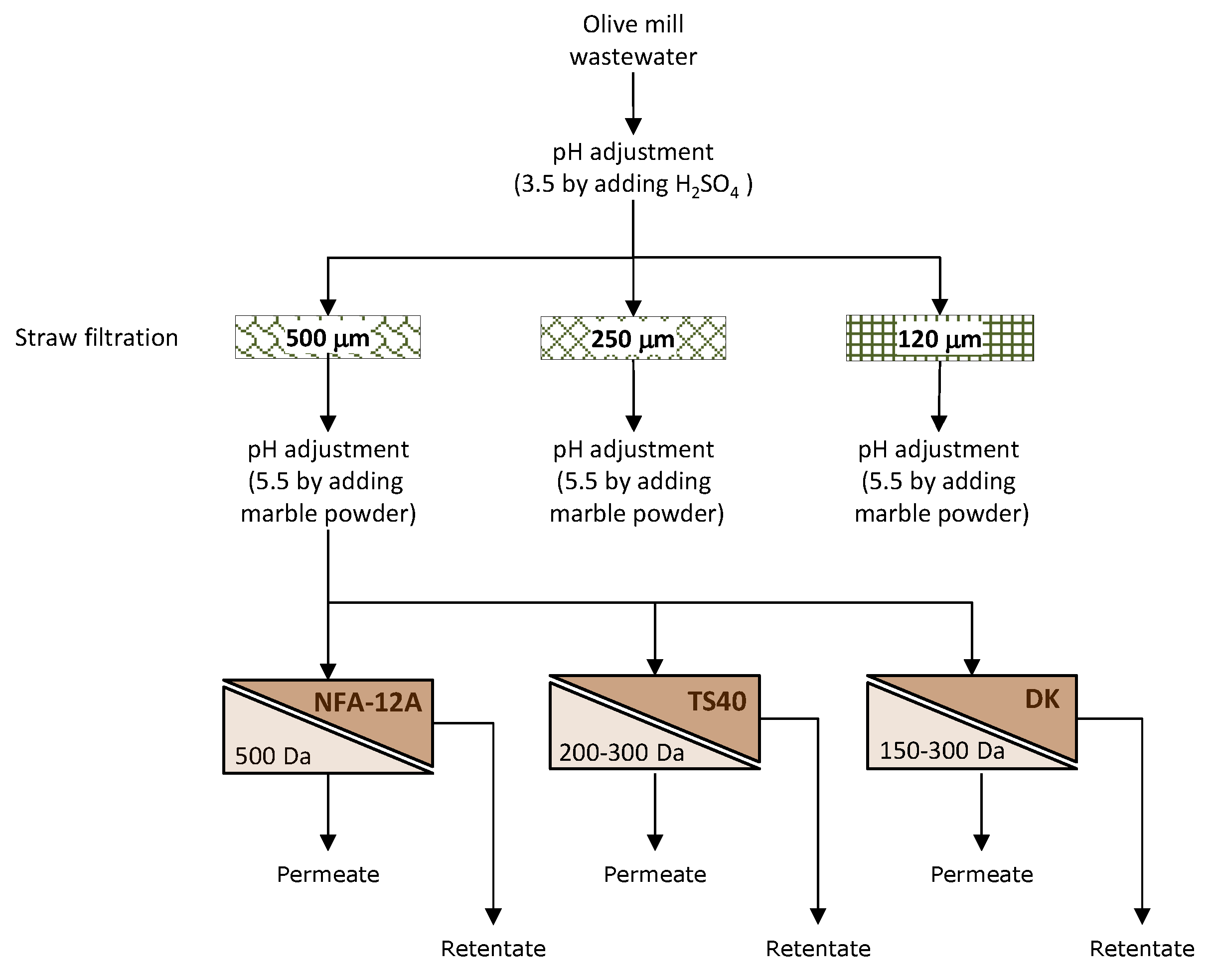

The block diagram of the investigated process is depicted in

Figure 2.

2.4. Analytical determinations

2.4.1. Total soluble solids, pH and electrical conductivity

Total soluble solids (TSS) were measured by using a hand refractometer (Atago Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with a scale range of 0-32 °Brix. pH was measured by an Orion Expandable ion analyzer EA 920 pH meter (Allometrics, Inc., Baton Rouge, LA, USA) with automatic temperature compensation. The electricalconductivity was measured by a Five Easy FE30 conductivity meter (Mettler-Toledo S.p.A.,Milano, Italia).

2.4.2. Total polyphenols

Total polyphenols were estimated colorimetrically using the Folin-Ciocalteu method [

33]. The method is based on the reduction of tungstate and/or molybdate in the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent byphenols in an alkaline medium, resulting in a blue colored product. Gallic acid was used as a calibration standard and the results were expressed as the gallic acid equivalent (mgGAE/L). The absorbance was measured using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (ShimadzuUV-160A, Kyoto, Japan) at 765 nm.

2.4.3. Total antioxidant activity

The total antioxidant activity (TAA) was determined according to an improved version of the 2,2-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid (ABTS) radical cation decolourisation assay, in which the radical monocation (ABTS

+) is generated by the oxidation of ABTS (Sigma Aldrich, Milano, Italy) with potassium persulphate (Sigma Aldrich, Milano, Italy), before the addition of the antioxidant [

34]. The results were expressed as trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC).

2.4.4. Flavanols and hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives

Flavanols and hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives were determined according to the methodreported by Obied et al. [

35]. One mL of diluted ethanolic extract (1:10 in water) was mixed with 1 mL of HCl-ethanol solution (0.1 mL HCl/100 mL in 95 mL ethanol/100 mL) into a 10 mL volumetric flask and the volume was made up to 10 mL with 2 mL HCl/100 mL. After mixing, the absorbance was measured at 320 and 360 nm to determine hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives and flavanols, respectively. Results were expressed as mg/L of caffeic acid (λ, 320 nm) and quercetin (λ, 360 nm), respectively.

2.4.5. Chemical Oxigen Demand

Chemical Oxigen Demand (COD) measurements were carried out by using a photometric test kit (COD Cell Test C4/25). Spectrophotometric measurements were performed by using PhotoLab 7600 UV-VIS - WTW spectrophotometer (Xylem Analytics Germany Sales GmbH & Co. KG., Weilheim, Germany.

2.4.6. Statistical analysis

All analytical measurements were conducted in triplicates and results were expressed as the average of the three measures ± the standard deviation.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Straw filtration

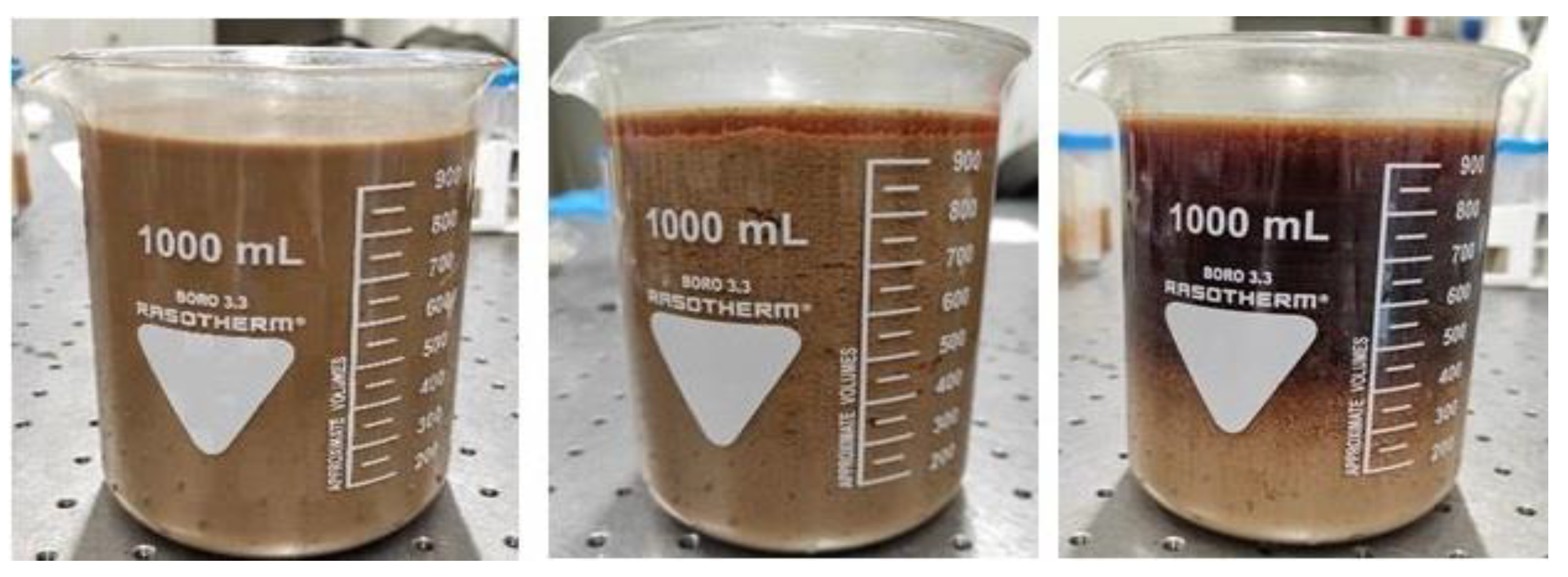

After acidification with sulfuric acid, the raw wastewater was left to flocculate/settle so that solid micro-particles could merge and form larger particles easy to be separated from the liquid phase. According to Bazzarelli et al. [

36], the zeta potential of OMWs at pH 4.5 is – 30 mV resulting in greater electrostatic repulsion forces between particles and reduced aggregation/flocculation phenomena caused by Van der Waals interactions. The pH adjustment destabilizes the suspension reducing the zeta potential of the particles (absolute value) so promoting their aggregation and flocculation. Following the acidification process, the vegetation water was splitted into two distinct phases: a darker and clearer upper phase and a lighter and cloudier lower phase in which the solid organic material, at first homogeneously distributed throughout the volume, is settled (

Figure 3).

As reported previously, the decanted water was filtered through straw powder filters of different granulometry: 120, 250 and 500 μm. After filtration about 100 mL of saturated solid residues were retained by the filter.

Figure 4 shows the 3.5 cm layer of powdered plant material supported by the nylon fabric, on the left, while the gel retained by the filter, above the aforementioned layer, is visible on the right.

The straw filters showed an excellent purifying capacity; however, the filtration rate decreased over time due to the clogging effect of the slime film, gradually deposited by the liquid flow on the filter surface. Anyway, the filtering capacity was easily restored without affecting the thickness of the purifying layer, whose intrinsic porosity did not change, by simply removing the shallow jelly film mechanically. Such an operation allowed the 500 μm filter to maintain a filtering capacity of 0.8 m3/m2h. If the slime derived from vegetation water is mixed with a similar weight of the plant material adopted for the filter, a friable and easily compostable composite could be obtained. This composite material, in fact, unlike the filtered one having a compact jelly structure, is highly permeable by air. We believe that this is one of the strengths of the developed filtration system. The gelatinous solids, gradually removed from the filter, can be actually delivered, together with the filtering material, to a suitable composter for the production of agricultural amendment.

The filtered water produced in each test (900 mL) was then brought back around the original pH, by adding marble powder (CaCO

3), before the NF tests. COD was measured again after pH balancing. The results of straw filtration experiments are summarized in

Table 2. The filtration rate with the 120 μm filter resulted about 80% lower than that obtained with the 500 μm (23.7 mL/min against 112.5 mL/min). The removal of COD for the straw filters investigated was in the range of 64.8 – 73.3% with the 500 μm filter exhibiting the highest removal percentage (73.3%).

The observed differences in the water filtered using different size straw filters, are slightly higher with respect to the measurement experimental errors. They must be probably attributed to the small quantities of dissolved straw components, which were not completely removed during the washing of the powder. A different small contribution of these soluble components is in fact expected in the various experiments, due the different filtering size particles and different filtering times. These considerations could justify the best result obtained in the case of the 500 μm filter, due to a lower exposed surface of the filtering fibers and to a shorter filtering time. Neutralized waters presented a bright black color, as shown in the picture on the right in

Figure 5.

3.2. Nanofiltration

Clarified wastewaters coming from the filtration step with straw powder ground at a size of 500 μm and neutralized at pH 5.5 were submitted to a NF treatment with three different flat-sheet membranes in selected operating conditions (applied pressure, 20 bar; temperature, 24 ± 2 °C).

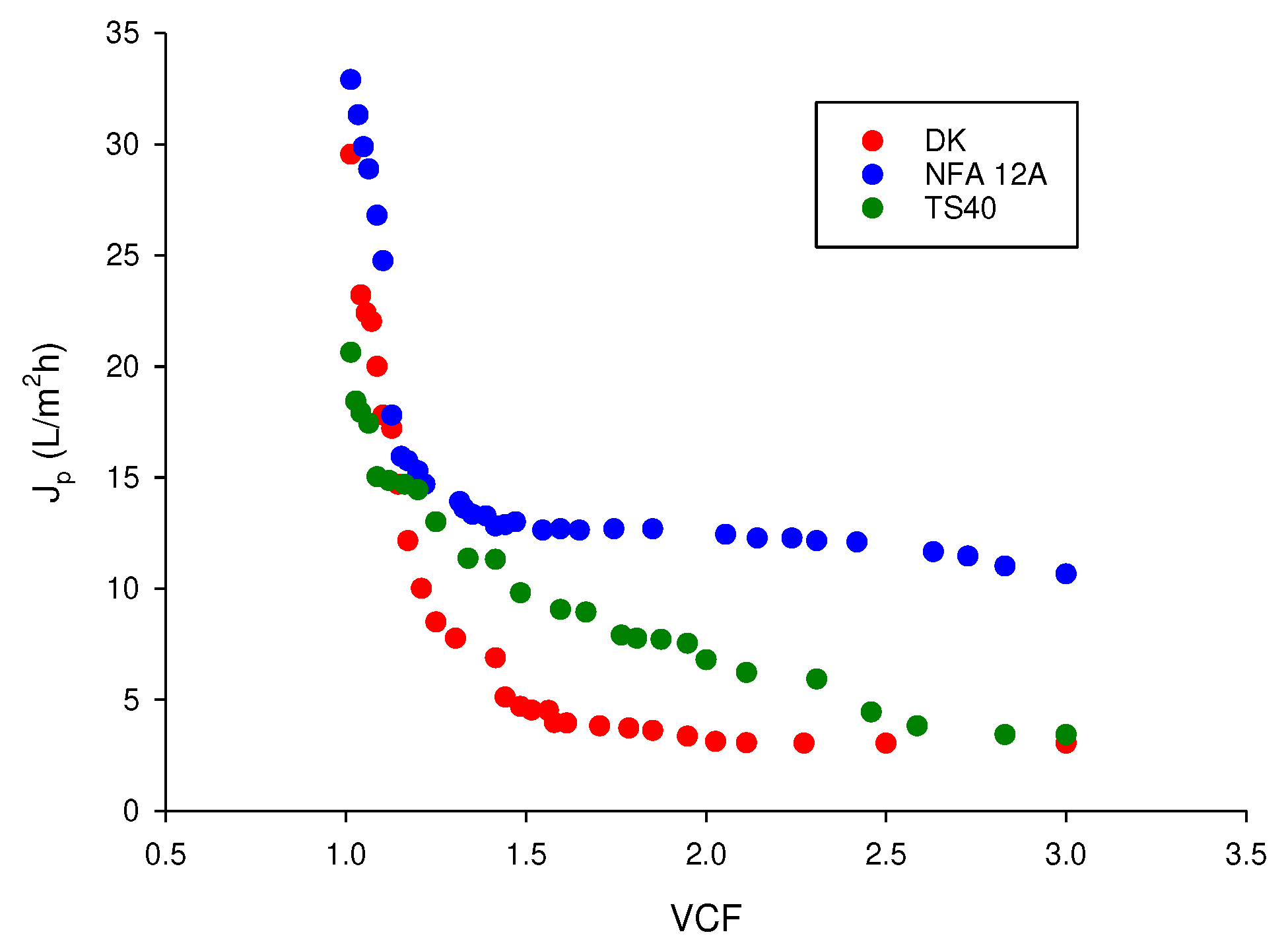

Figure 6 shows the evolution of permeate flux in terms of liters of permeate produced per unit area and time (L/m

2h) as a function of VCF for the investigated membranes. For all membranes the J

p versus VCF curve can be divided in three periods: an initial period in which a rapid decrease of permeate flux occurred; a second period, up to VCF 2, corresponding to a smaller decrease of permeate flux; a third period characterised by a small decrease of permeate flux up to reach a steady-state value.

It is known that flux decline can be caused by various factors such as concentration polarization, gel layer formation and pore blocking by OMW components. All these factors produce further resistances on the feed side to transport across the membrane [

37].

The NFA-12A membrane exhibited a better performance in terms of initial (32.9 L/m

2h) and steady-state (11.4 L/m

2h) permeate fluxes in comparison with the other tested membranes. This result can be attributed to the higher MWCO of this membrane, as well as to its higher hydrophilicity. In particular, permeate fluxes resulted similar to those reported by Zirehpour et al. [

37] for spiral-wound NF membranes (NF-270 and NF-90 membranes with MWCO of 200-250 and 150-200 Da, respectively) in the treatment of microfiltered OMWs. Similarly, Bazzarelli et al. [

36] reported permeate flux values lower than 10 L/m

2h in the treatment of microfiltered OMWs with a spiral-wound NF-90 membrane (at an operating pressure of 10 bar ) having a MWCO of 200 Da. Therefore, the global findings clearly show that the straw filtration operation is able to reduce submicron particles of OMWs producing clarified solutions that meet the SDI index to be concentrated with commercial spiral-wound NF membranes.

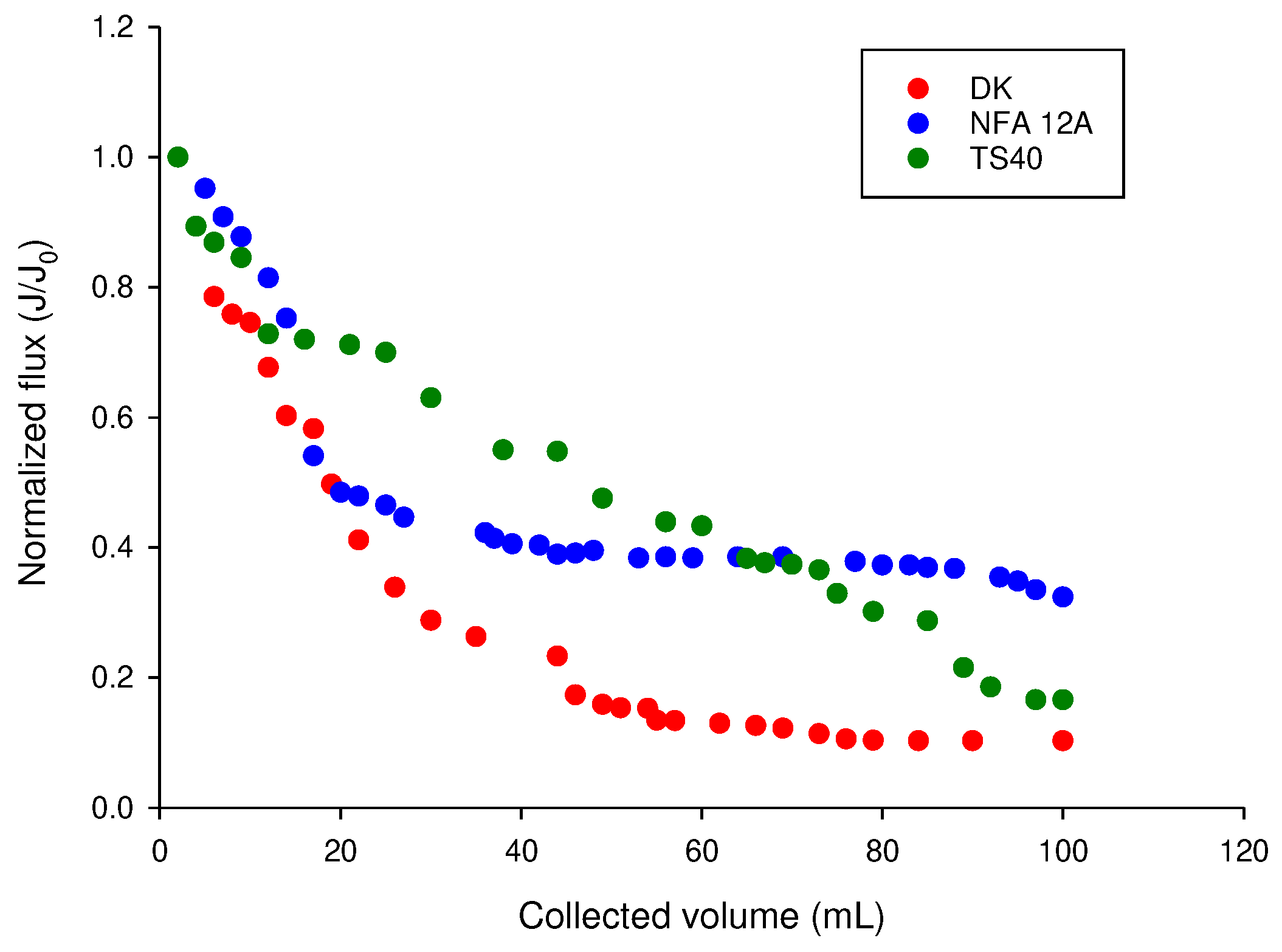

The normalized flux as a function of the collected permeate volume (

Figure 7) also showed a steep decrease for all selected membranes: however, flux losses were around 67.6% of the original value for the NFA-12A membrane, whilst flux losses for membranes TS40 and DK were 83.4% and 89.7%, respectively. These results confirm a lower propensity of the NFA-12A membrane to be fouled as a consequence of its higher hydrophilicity. In addition, the enzymatic washing allowed the measured water permeability to be fully recovered for the pristine membrane.

Analytical measurements performed on feed, permeate and retentate samples treated with the investigated membranes are reported in

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5. For all selected membranes the TSS content of the permeate was of about 1.0-1.2 °Brix while the electrical conductivity was in the range 18.7-19.6 mS/cm. Accordingly, the reductions of these parameters, in comparison to the clarified wastewater, were of the order of 64-69% and 47-49%, respectively.

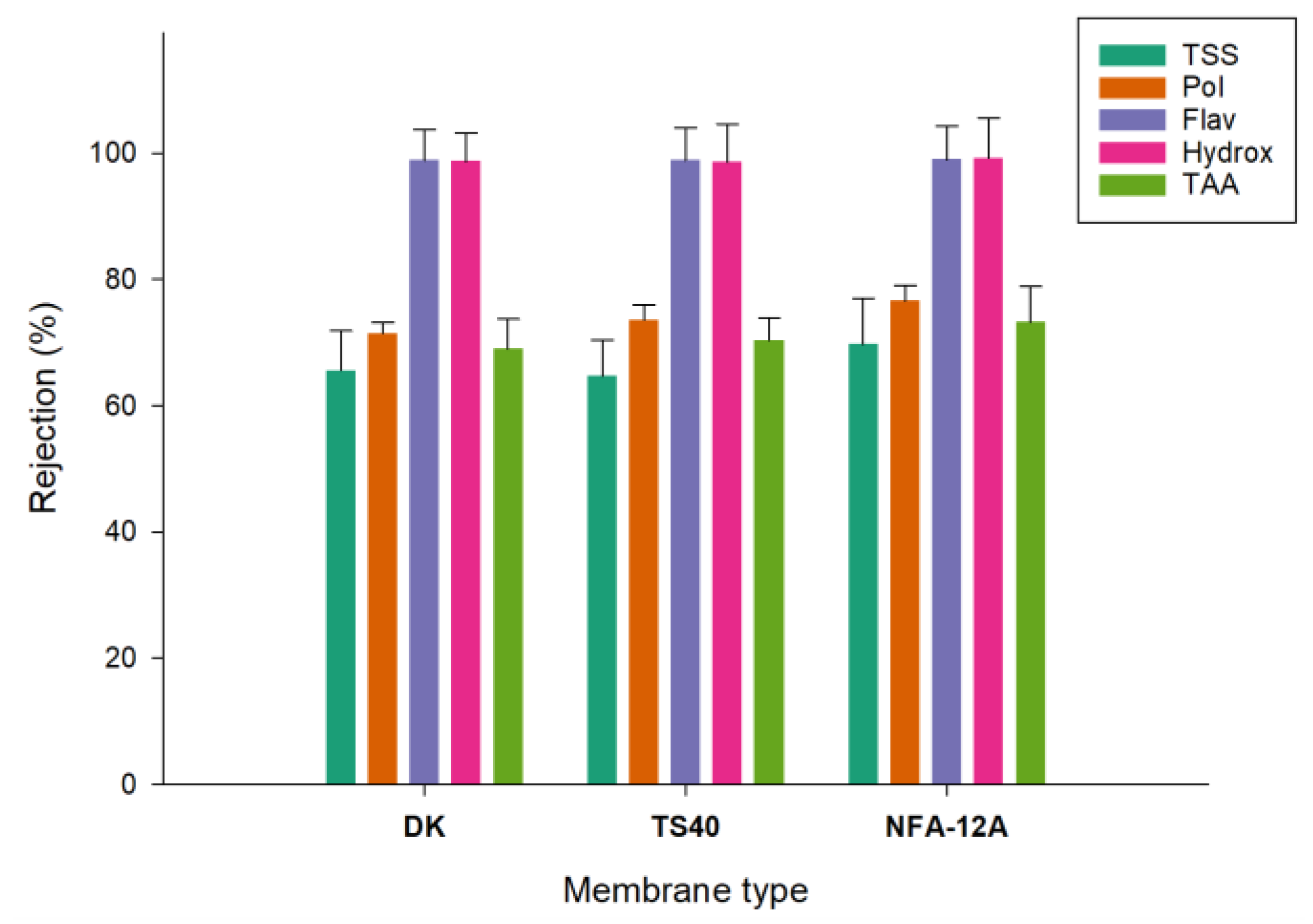

The rejections of selected membranes towards the analysed compounds are illustrated in

Figure 8. For all membranes the rejections towards flavanols and hydroxycinnamic acd derivatives were of the order of 99%. Similar results were obtained by Conidi et al. [

38] in the treatment of clarified olive mill solid waste aqueous extracts with polymeric membranes having a MWCO in the range of 150-500 Da, including the NFA-12A membrane.

Rejections for total phenolic compounds were in the range of 71.5-76.6% with the NFA-12A membrane exhibiting the highest value (76.6%). These values are higher than those measured by Alfano et al. [

39] in the treatment of OMWs based on an initial flocculation with celite, followed by a sequential treatment with ultra- and nano-filtration spiral-wound membranes in polyethersulfone with MWCO of 100 kDa and 3-5 Da, respectively. Specifically, the NF permeate showed a reduction of about 95% of the organic load and the polyphenols recovery, after two filtration steps, was about 65% w/v.

The rejection for TAA was between 69% and 73.2%, in agreement with the rejection observed for total polyphenols. As a result, the retentate fraction obtained with the NFA-12A membrane presented the highest concentration of phenolic compounds (3785.1 ± 20.3 mg GAE/L), as well as the highest value of TAA (18.9 ± 0.7 mM Trolox). These data confirm previous findings about the correlation between the content of total phenols measured with the Folin-Ciocalteu method and the antioxidant activity determined by different methods including ABTS and DPPH assays [

40]. On the other hand, the DK membrane, with the lowest MWCO (150-300 Da), showed a lower rejection towards phenolic compounds in comparison with the other two NF membranes. These results confirm previous findings regarding the non-strict correlation between the MWCO and separation of phenolic compounds on the basis of their molecular weight. Indeed, other factors apart from steric mechanisms, including the hydrophobicity of the membrane surface and the solubility of the solutes can affect the separation mechanism, reducing the impact of the pores dimension [

41]. The interaction between phenolic compounds and/or retained macromolecules to form large sized particles which can be adsorbed on the membrane surface, can also contribute to increase the resistance to permeation [

42].

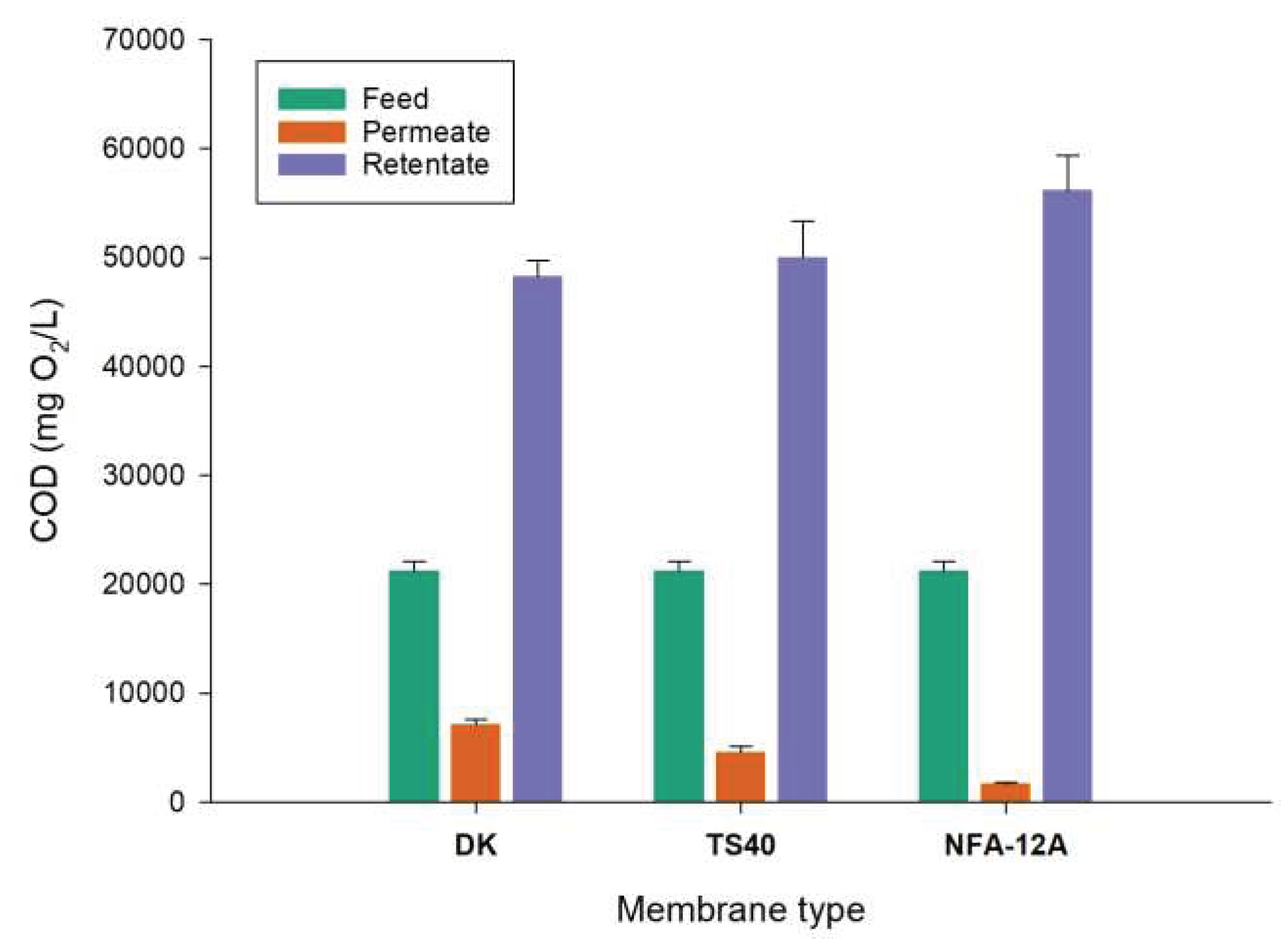

The COD evaluation in samples from NF of clarified OMWs with different membranes is illustrated in

Figure 9. According to the measurements in permeate samples the reduction of COD in the clarified wastewaters with DK, TS40 and NFA-12A membranes was 66.1%, 78.2% and 92.1%, respectively. These data are also in agreement with those observed for total phenols rejections with the NFA-12A membrane exhibiting the highest rejection value.

The global results presented herein demonstrated that the combination of straw filtration and NF with the NFA-12A membrane reduces effectively more than 97% of initial COD of raw wastewaters with a final COD in the NF permeate of 1,668 mg/L. These results are particularly encouraging if we take into account the simpler treatment of vegetation water compared to those proposed so far. For example, COD reductions of 94% were observed by Coskun et al. [

43] in the pre-treatment of OMWs by centrifugation followed by ultrafiltration and NF (with a NF-270 membrane having a MWCO of 200-300 Da). The final COD measured in the NF permeate resulted of 5,800 mg/L. The use of RO at 25 bar pressure, instead of NF, improved the removal of COD with a production of a permeate having a COD of 1,000 mg/L. In another approach, the combination of lime precipitation, filtration with a membrane filter press and filtrate post-treatment using activated carbon adsorption produced a maximum removal of total organics of 80% [

44]. Other proposed processes allow a complete reclamation of OMWs without considering the recovery of phenolic compounds. For instance, in the approach proposed by Ochando-Pulido et al. [

45] the COD of olive mill effluents from two-phase extraction process was reduced up to 99.1% through a depuration procedure integrating both an advanced oxidation process based on Fenton’s reagent (secondary treatment) coupled with a final reverse osmosis (RO) stage (tertiary or purification step).

4. Conclusions

An eco-sustainable process is presented to valorize olive mill wastewaters for the recovery of natural antioxidants in a logic of the circular economy. In this approach straw filtration was investigated for the first time as a pretreatment step to produce a clarified effluent containing most phenolic compounds. Solids removed from the filter together with the filtering material represent a suitable composter for the production of agricultural amendments.

Among the ground straw filters investigated, the 500 μm filter offered the best performance in terms of filtering time and removal of organic substances with a reduction of more than 70% of the organic load of the raw wastewater.

Three NF membranes in flat-sheet configuration were tested to recover and concentrate bioactive compounds from the clarified wastewaters. Among the investigated membranes, the NFA-12A membrane showed the highest productivity and the lowest propensity to membrane fouling in the selected operating conditions. This membrane rejected more than 99% of flavanols and hydroxycinnamic acids of clarified wastewaters. Rejections towards total polyphenols and TAA (76.6% and 73.2%, respectively) resulted also higher than those observed for the other membranes. As result, the NF retentate fractions appear of practical interest for the production of food additives and food supplements as well as of cosmeceuticals due to their high content of phenolic compounds.

The permeate of the NF showed COD values of about 1.6 g O2/L with a reduction of about 97.6% of the organic load when compared to the initial wastewater: this purified fraction could be reused for irrigation purposes, membrane cleaning and washing of manufacture equipments in olive oil industry.

The desired target requirements in terms of COD which is below 500 mg/L, according to the Italian allowance for the municipal sewer system discharge of wastewaters, could be reached by treating the NF permeate through an additional RO step.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C. and G.D.F.; methodology, F.C., G.D.F., R.M. and A.C.; validation, C.C. and R.M.; formal analysis, F.C., C.C., G.D.F. and A.C.; investigation, M.R.B., C.C. and R.M.; data curation, M.R.B. and A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.B. and A.C.; writing—review and editing, A.C.; visualization, F.C., C.C. and G.D.F.; supervision, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Regione Calabria for the financial support to the project “Gestione integrale del frantoio oleario a ciclo chiuso (GINFRACC)" within the framework PSR Calabria 2014-2020 – Misura 16 – intervento 16.02.01 “Sviluppo di nuovi prodotti, pratiche, processi e tecnologie nel settore agroalimentare e forestale”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bouhia, Y.; Hafidi, M.; Ouhdouch, Y.; Lyamlouli, K. Olive mill waste sludge: From permanent pollution to a highly beneficial organic biofertilizer: A critical review and future perspectives. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2023, 259, 114997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, P.; Sicilia, V.; Candamano, S.; Macario, A. Olive vegetation waters (OVWs): characteristics, treatments and environmental problems. IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2022, 1251, 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodaifa, G.; Eugenia-Sánchez, M.; Sánchez, S. Use of industrial wastewater from olive-oil extraction for biomass production of Scenedesmus obliquus. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paraskeva, P.; Diamadopoulos, E. Technologies for olive mill wastewater (OMW) treatment: a review. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2006, 81, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visioli, F.; De la Lastra, C.A.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Aviram, M.; Calhau, C.; Cassano, A.; D’Archivio, M.; Faria, A.; Fave, G.; Fogliano, V.; Llorach, R.; Vitaglione, P.; Zoratti, M.; Edeas, M. Polyphenols and human health, a prospectus. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 51, 524–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Mar Contreras, M.; Romero, I.; Moya, M.; Castro, E. Olive-derived biomass as a renewable source of value-added products. Process Biochem. 2020, 97, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig, A.; Cayuela, M.L.; Sánchez-Monedero, A. An overview on olive mill wastes and their valorisation methods. Waste Manage. 2006, 26, 960–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, S.; Bilgin, M. Olive tree (Olea europaea L.) leaf as a waste by-product of table olive and olive oil industry: a review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochando-Pulido, J.M.; Fragoso, R.; Macedo, A.; Duarte, E.; Ferez, A.M. A brief review on recent processes for the treatment of olive mill effluents. In Products from Olive Tree; Boskou, D., Clodoveo, M.L., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016; pp. 283–300. [Google Scholar]

- Chidichimo, F.; De Biase, M.; Tursi, A.; Maiolo, M.; Straface, S.; Baratta, M.; Olivito, F.; De Filpo, G. A model for the adsorption process of water dissolved elements flowing into reactive porous media: Characterization and sizing of water mining/filtering systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 445, 130554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pugliese, L.; De Biase, M.; Chidichimo, F.; Heckrath, G.J.; Iversen, B.V.; Kjærgaard, C.; Straface, S. Modelling phosphorus removal efficiency of a reactive filter treating agricultural tile drainage water. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 156, 105968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Muñoz, R.; Barragán-Huerta, B.E.; Fíla, V.; Denis, P.C.; Ruby-Figueroa, R. Current role of membrane technology: from the treatment of agro-industrial by-products up to the valorization of valuable compounds. Waste Biomass Valor. 2018, 9, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Muñoz, R.; Conidi, C.; Cassano, A. Membrane-based technologies for meeting the recovery of biologically active compounds from foods and their by-products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2927–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, S.; Timpano, P.; Halil Avci, A.; Argurio, P.; Chidichimo, F.; De Biase, M.; Straface, S.; Curcio, E. An integrated membrane distillation, photocatalysis and polyelectrolyte-enhanced ultrafiltration process for arsenic remediation at point-of-use. Desalination 2021, 520, 115378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskeva, C.A.; Papadakis, V.G.; Kanellopoulou, D.G.; Koutsoukos, P.G.; Angelopoulos, K.C. Membrane filtration of olive mill wastewater (OMW) and OMW fractions exploitation. Water Environ. Res. 2007, 79, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoller, M.; Bravi, M. Critical flux analyses on differently pretreated olive vegetation waste water streams: some case studies. Desalination 2010, 250, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskeva, C.A.; Papadakis, V.G.; Tsarouchi, E.; Kanellopoulou, D.G.; Koutsoukos, P.G. Membrane processing for olive mill wastewater fractionation. Desalination 2007, 213, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanova, L.; Villanova, L.; Fasiello, G.; Merendino, A. Process for the recovery of tyrosol and hydroxytyrosol from oil mill wastewaters and catalytic oxidation method in order to convert tyrosol in hydroxytyrosol. US Patent US-7427358-B2, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Castello, E.; Cassano, A.; Criscuoli, A.; Conidi, C.; Drioli, E. Recovery and concentration of polyphenols from olive mill wastewaters by integrated membrane system. Wat. Res. 2010, 44, 3883–3892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassano, A.; Conidi, C.; Giorno, L.; Drioli, E. Fractionation of olive mill wastewaters by membrane separation techniques. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 248–249, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, A.; Conidi, C.; Drioli, E. Comparison of the performance of UF membranes in olive mill wastewaters treatment. Water Res. 2011, 45, 3197–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochando-Pulido, J.M.; Rodriguez-Vives, S.; Hodaifa, G.; Martinez-Ferez, A. Impacts of operating conditions on reverse osmosis performance of pretreated olive mill wastewater. Water Res. 2012, 46, 4621–4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Arevalo, C.M.; Jimeno-Jimenez, A.; Carbonell-Alcaina, C.; Vincent-Vela, M.C.; Alvarez-Blanco, S. Effect of the operating conditions on a nanofiltration process to separate low-molecular-weight phenolic compounds from the sugars present in olive mill wastewaters. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 148, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Abbassi, A.; Kiai, H.; Raiti, J.; Hafidi, A. Application of ultrafiltration for olive processing wastewaters treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochando-Pulido, J.M. A review on the use of membrane technology and fouling control for olive mill wastewater treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 563–564, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, C. A new membrane process for the selective fractionation and total recovery of polyphenols, water and organic substances from vegetation waters (VW). J. Membr. Sci. 2007, 288, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turano, E.; Curcio, S.; De Paola, M.G.; Calabrò, V.; Iorio, G. An integrated centrifugation–ultrafiltration system in the treatment of olive mill wastewater. J. Membr. Sci. 2002, 209, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoller, M.; Chianese, A. Influence of the adopted pretreatment process on the critical flux value of batch membrane processes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 2249–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidichimo, G.; Manfredi, F.; Gullo, G.; Basile, M.R.; Lania, I.; Chidichimo, F.; De Biase, M.; De Filpo, G.; Ferraro, P.L. Filtro per la depurazione di acque inquinate. Italian patent number 102023000004089, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova, A.; Astudillo, C.; Giorno, L.; Guerrero, C.; Conidi, C.; Illanes, A.; Cassano, A. Nanofiltration potential for the purification of highly concentrated enzymatically produced oligosaccharides. Food Bioprod. Process. 2016, 98, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdarta, J.; Thygesen, A.; Holm, M.S.; Meyer, A.S.; Pinelo, M. Direct separation of acetate and furfural from xylose by nanofiltration of birch pretreated liquor: Effect of process conditions and separation mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 239, 116546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acero, J.L.; Benitez, F.J.; Leal, A.I.; Real, F.J.; Teva, F. Membrane filtration technologies applied to municipal secondary effluents for potential reuse. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 177, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substratesand antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C.A. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obied, H.K.; Allen, H.S.; Bedgood, D.R.; Prenzler, P.; Robards, K. Investigation of Australian olive millwaste for recovery of biophenols. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 9911–9920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzarelli, F.; Poerio, T.; Mazzei, R.; D’Agostino, N.; Giorno, L. Study of OMWWs suspended solids destabilization to improve membrane processes performance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2015, 149, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirehpour, A.; Jahanshahi, M.; Rahimpour, A. Unique membrane process integration for olive oil mill wastewater purification. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012, 96, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conidi, C.; Corbacho, A.E.; Cassano, A. Combination of aqueous extraction and polymeric membranes as a sustainable process for the recovery of polyphenols from olive mill solid wastes. Polymers 2019, 11, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfano, A.; Corsuto, L.; Finamore, R.; Savarese, M.; Ferrara, F.; Falco, S.; Santabarbara, G.; De Rosa, M.; Schiraldi, C. Valorization of olive mill wastewater by membrane processes to recover natural antioxidant compounds for cosmeceutical and nutraceutical applications or functional foods. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roginsky, V.; Lissi, A.E. Review of methods to determine chain breaking antioxidant activity in food. Food Chem. 2005, 92, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M. Separation of functional macromolecules and micromolecules: From ultrafiltration to the border to nanofiltration. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 42, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, A.; De Luca, G.; Conidi, C.; Drioli, E. Effect of polyphenols-membrane interactions on the performance of membrane-based processes. A review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 351, 45–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, T.; Debik, E.; Demir, N.M. Treatment of olive mill wastewaters by nanofiltration and reverse osmosis membranes. Desalination 2010, 259, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shafey, E.I.; Correia, P.F.M.; de Carvalho, J.M.R. An integrated process of olive mill wastewater treatment. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2005, 40, 2841–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochando-Pulido, J.M.; Hodaifa, G.; Victor-Ortega, M.D.; Rodriguez-Vives, S.; Martinez-Ferez, A. Reuse of olive mill effluents from two-phase extraction process by integrated advanced oxidation and reverse osmosis treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 263, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Experimental filter for the removal of suspended solids from vegetation water: (A) Hydraulic valve connecting the lower chamber with a vacuum pump; (B) filtered water drain valve; (C) top vision of the filter with the support technical sheet.

Figure 1.

Experimental filter for the removal of suspended solids from vegetation water: (A) Hydraulic valve connecting the lower chamber with a vacuum pump; (B) filtered water drain valve; (C) top vision of the filter with the support technical sheet.

Figure 2.

Block diagram of experimental activities.

Figure 2.

Block diagram of experimental activities.

Figure 3.

From left to right: vegetable water as it is, acidified vegetable water after 1h, and then after 24h.

Figure 3.

From left to right: vegetable water as it is, acidified vegetable water after 1h, and then after 24h.

Figure 4.

Clean straw filter (left picture); solid residues on the filter surface (right picture).

Figure 4.

Clean straw filter (left picture); solid residues on the filter surface (right picture).

Figure 5.

The left picture shows samples S120, S500 and US collected for COD measurement; in the right picture vegetation water filtered and neutralized at pH 5.5.

Figure 5.

The left picture shows samples S120, S500 and US collected for COD measurement; in the right picture vegetation water filtered and neutralized at pH 5.5.

Figure 6.

Nanofiltration of clarified OMWs. Permeate flux as a function of VCF for selected membranes. Operating conditions: applied pressure, 20 bar; temperature, 24 ± 2 °C.

Figure 6.

Nanofiltration of clarified OMWs. Permeate flux as a function of VCF for selected membranes. Operating conditions: applied pressure, 20 bar; temperature, 24 ± 2 °C.

Figure 7.

Nanofiltration of clarified OMWs. Evolution of the normalized permeate flux with cumulative permeate volume. Experimental conditions: applied pressure, 20 bar; temperature, 24 ± 2 °C.

Figure 7.

Nanofiltration of clarified OMWs. Evolution of the normalized permeate flux with cumulative permeate volume. Experimental conditions: applied pressure, 20 bar; temperature, 24 ± 2 °C.

Figure 8.

Rejections of NF membranes towards specific compounds (TSS, Total Soluble Solids; Pol, total Polyphenols; Flav, Flavanols; Hydroxy, Hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives; TAA, Total Antioxidant Activity).

Figure 8.

Rejections of NF membranes towards specific compounds (TSS, Total Soluble Solids; Pol, total Polyphenols; Flav, Flavanols; Hydroxy, Hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives; TAA, Total Antioxidant Activity).

Figure 9.

COD evaluation in samples from NF of clarified OMWs with different membranes.

Figure 9.

COD evaluation in samples from NF of clarified OMWs with different membranes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of NF flat-sheet membranes (PA-TFC, polyamide – thin film composite; MWCO, molecular weight cut-off).

Table 1.

Characteristics of NF flat-sheet membranes (PA-TFC, polyamide – thin film composite; MWCO, molecular weight cut-off).

| Membrane type |

NFA-12A |

TS40 |

DK |

| Manufacturer |

Parker |

Microdyn-Nadir |

GE Osmonics |

| Membrane material |

PA-TFC |

PA-TFC |

PA-TFC |

| Configuration |

flat-sheet |

flat-sheet |

flat-sheet |

| Nominal MWCO (Da) |

500 |

200-300 |

150-300 |

| pH operating range |

3-11 |

1-12 |

3-9 |

| Max. operating temperature (°C) |

63 |

50 |

50 |

| Max. operating pressure (bar) |

30.6 |

41 |

41 |

| Contact angle (°) |

10a

|

30b

|

41c

|

| Water permeability at 18 ± 1 °C (L/m2hbar) |

9.2d

|

8.60d

|

3.64d

|

Table 2.

Results of straw filtration experiments on OMW samples.

Table 2.

Results of straw filtration experiments on OMW samples.

| ID |

Description |

Filtration rate

(mL/min) |

Solid residues

(mL) |

COD

(mg O2/L) |

pH |

| US |

OMW unaltered state |

- |

- |

70000 ± 3500 |

4.80 ± 0.24 |

| S120 |

Acidified OMW filtered with 120μm straw |

23.7 |

~100 |

22300 ± 1115 |

3.5 ± 0.17 |

| S250 |

Acidified OMW filtered with 250μm straw |

69.2 |

~100 |

24650 ± 1232 |

3.5 ± 0.16 |

| S500 |

Acidified OMW filtered with 500μm straw |

112.5 |

~100 |

18700 ± 935 |

3.5 ± 0.17 |

| S120N |

OMW filtered with 120μm straw + marble powder |

- |

- |

22500 ± 1125 |

5.5 ± 0.27 |

| S250N |

OMW filtered with 250μm straw + marble powder |

- |

- |

23350 ± 1167 |

5.5 ± 0.27 |

| S500N |

OMWW filtered with 500μm straw + marble powder |

- |

- |

21200 ± 1060 |

5.5 ± 0.27 |

Table 3.

Physico-chemical characteristics of feed, permeate and retentate samples from the treatment of OMWs with NFA-12A membrane.

Table 3.

Physico-chemical characteristics of feed, permeate and retentate samples from the treatment of OMWs with NFA-12A membrane.

| Parameter |

Feed |

Permeate |

Retentate |

| TSS (°Brix) |

3.3 ± 0.1 |

1.0 ± 0.1 |

7.3 ± 0.1 |

| Electrical conductivity (mS/cm) |

36.7 ± 0.7 |

18.7 ± 0.4 |

52.8 ± 0.6 |

| Total polyphenols (mg GAE/L) |

1918.4 ± 30.2 |

449.0 ± 12.7 |

3785.1 ± 20.3 |

| Flavanols (mg/L quercetin) |

623.53 ± 24.95 |

6.03 ± 0.22 |

1564.70± 66.55 |

| Hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives (mg/L caffeic acid) |

445.2 ± 17.4 |

3.49 ± 0.18 |

1186.3 ± 23.24 |

| TAA (mM Trolox) |

10.1 ± 0.7 |

2.7 ± 0.1 |

18.9 ± 0.7 |

Table 4.

Physico-chemical characteristics of feed, permeate and retentate samples from the treatment of OMWs with TS40 membrane.

Table 4.

Physico-chemical characteristics of feed, permeate and retentate samples from the treatment of OMWs with TS40 membrane.

| Parameter |

Feed |

Permeate |

Retentate |

| TSS (°Brix) |

3.4 ± 0.1 |

1.2 ± 0.1 |

5.6 ± 0.5 |

| Electrical conductivity (mS/cm) |

38.1 ± 0.3 |

19.6 ± 0.2 |

47.8 ± 0.7 |

| Total polyphenols (mg GAE/L) |

1973.3 ± 40.6 |

520.4 ± 12.7 |

3223.5 ± 71.2 |

| Flavanols (mg/L quercetin) |

605.88 ± 24.95 |

6.61 ± 0.21 |

1341.17 ± 58.23 |

| Hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives (mg/L caffeic acid) |

426.02 ± 23.24 |

5.96 ± 0.17 |

1006.85 ± 48.43 |

| TAA (mM Trolox) |

10.1 ± 0.4 |

3.0 ± 0.1 |

17.6 ± 1.1 |

Table 5.

Physico-chemical characteristics of feed, permeate and retentate samples from the treatment of OMWs with DK membrane.

Table 5.

Physico-chemical characteristics of feed, permeate and retentate samples from the treatment of OMWs with DK membrane.

| Parameter |

Feed |

Permeate |

Retentate |

| TSS (°Brix) |

3.2 ± 0.1 |

1.1 ± 0.1 |

5.7 ± 0.1 |

| Electrical conductivity (mS/cm) |

37.2 ± 0.2 |

19.4 ± 0.1 |

45.3 ± 1.2 |

| Total polyphenols (mg GAE/L) |

1960.8 ± 40.0 |

559.2 ± 7.1 |

3505.9 ± 42.3 |

| Flavanols (mg/L quercetin) |

611.76 ± 22.3 |

6.91 ± 0.22 |

1458.82± 58.23 |

| Hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives (mg/L caffeic acid) |

436.98 ± 13.56 |

5.34 ± 0.18 |

1173.97 ± 32.93 |

| TAA (mM Trolox) |

10.0 ± 0.6 |

3.1 ± 0.1 |

18.4 ± 0.6 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).