Submitted:

08 January 2024

Posted:

09 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

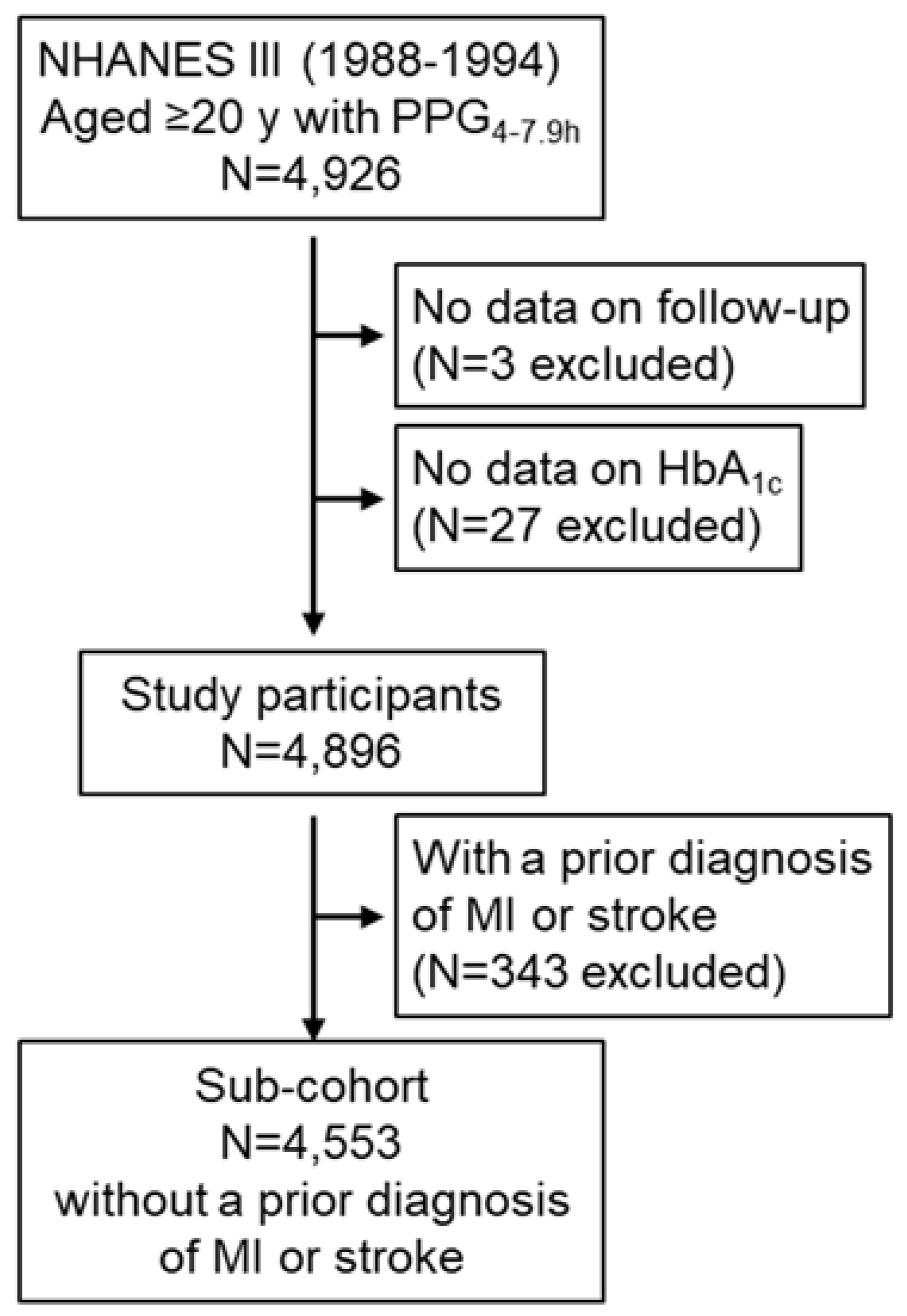

2.1. Participants

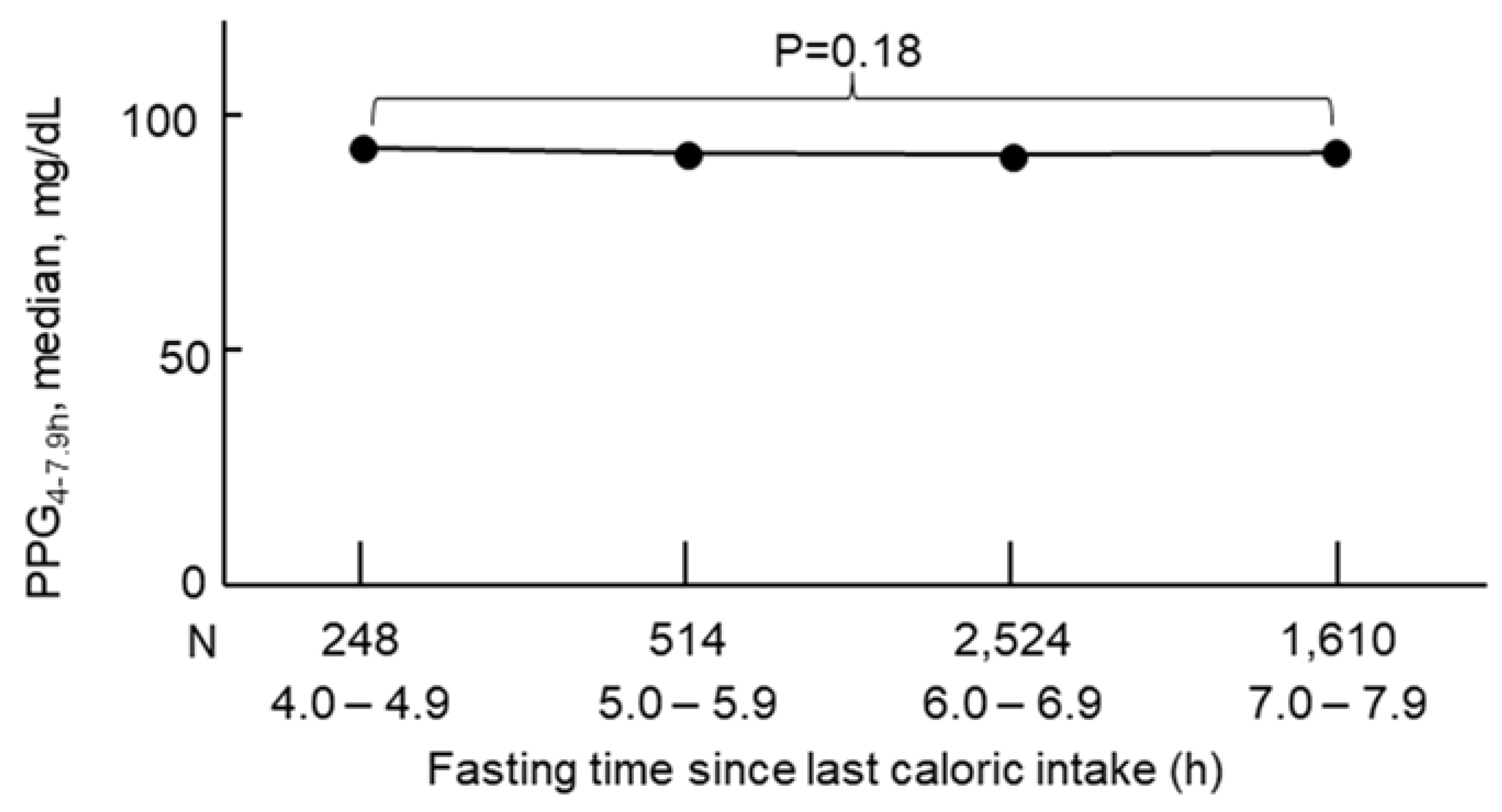

2.2. Measurement of Plasma Glucose

2.3. Mortality

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

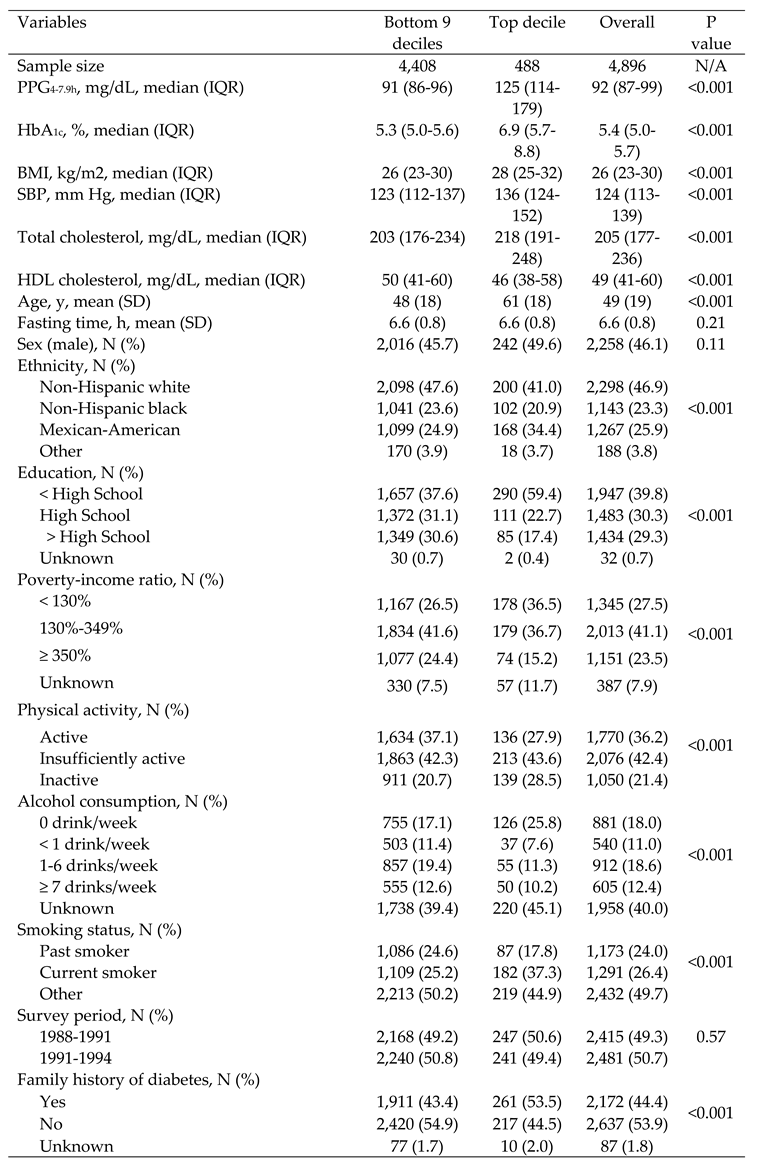

3.1. General Characteristics

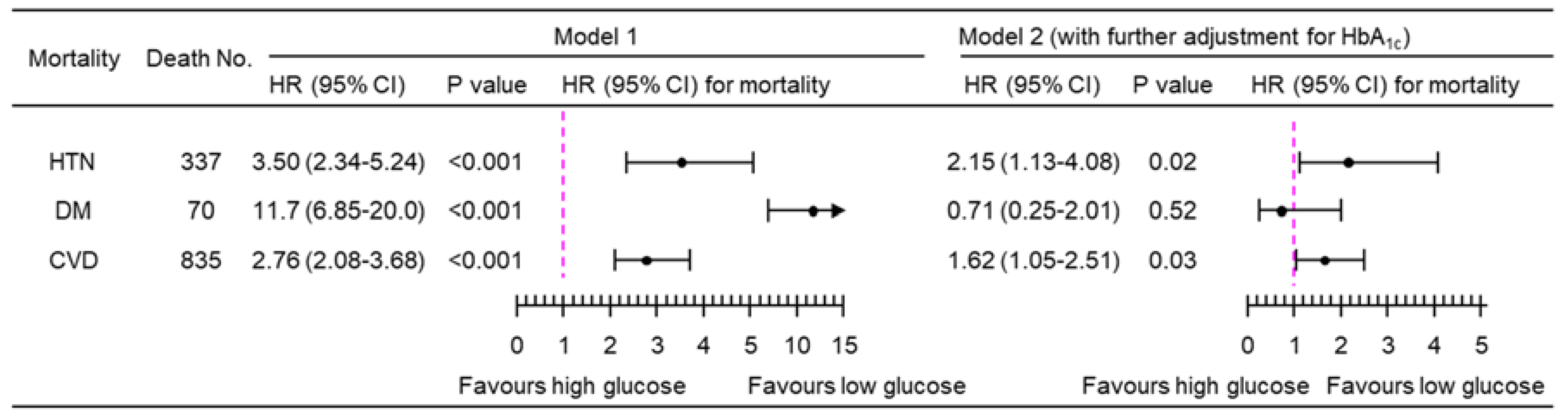

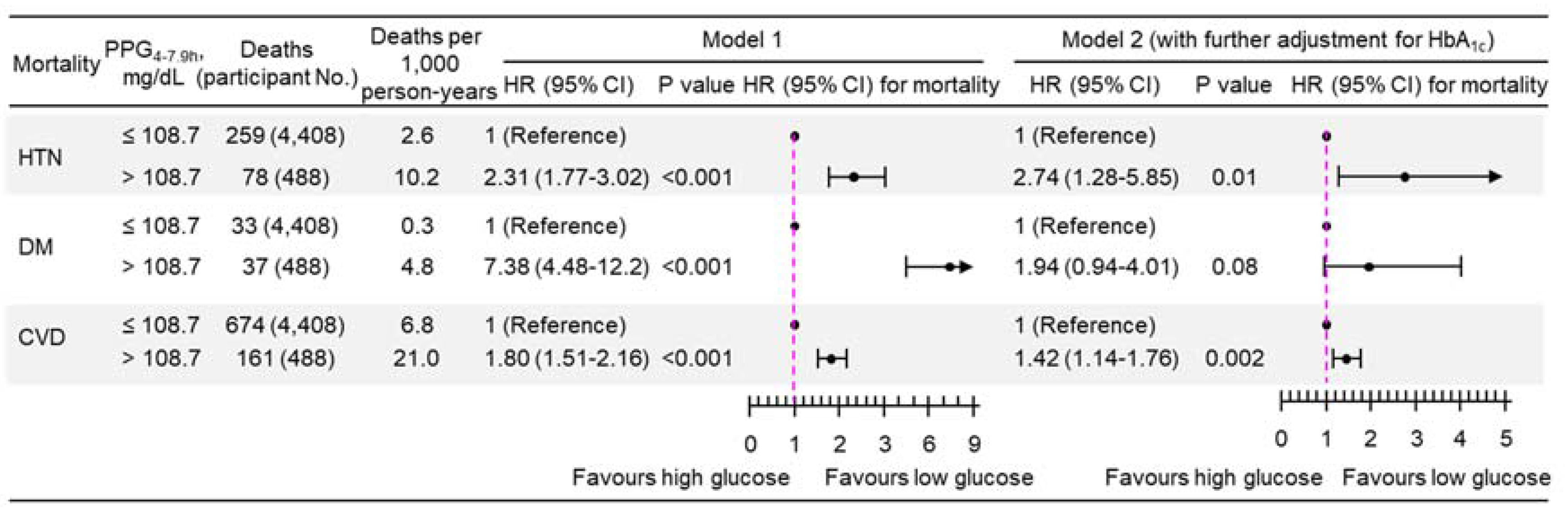

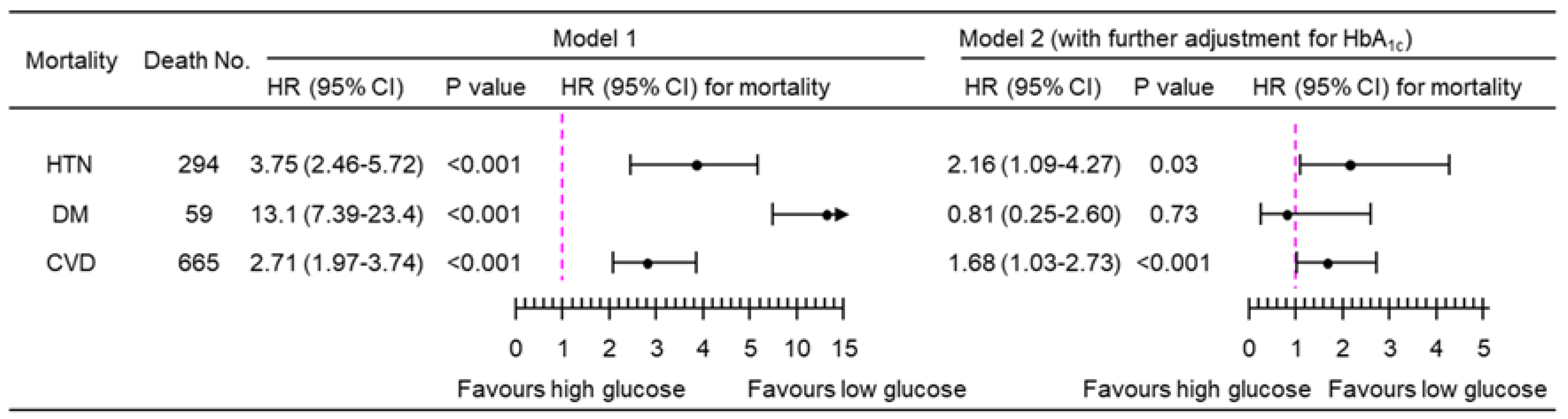

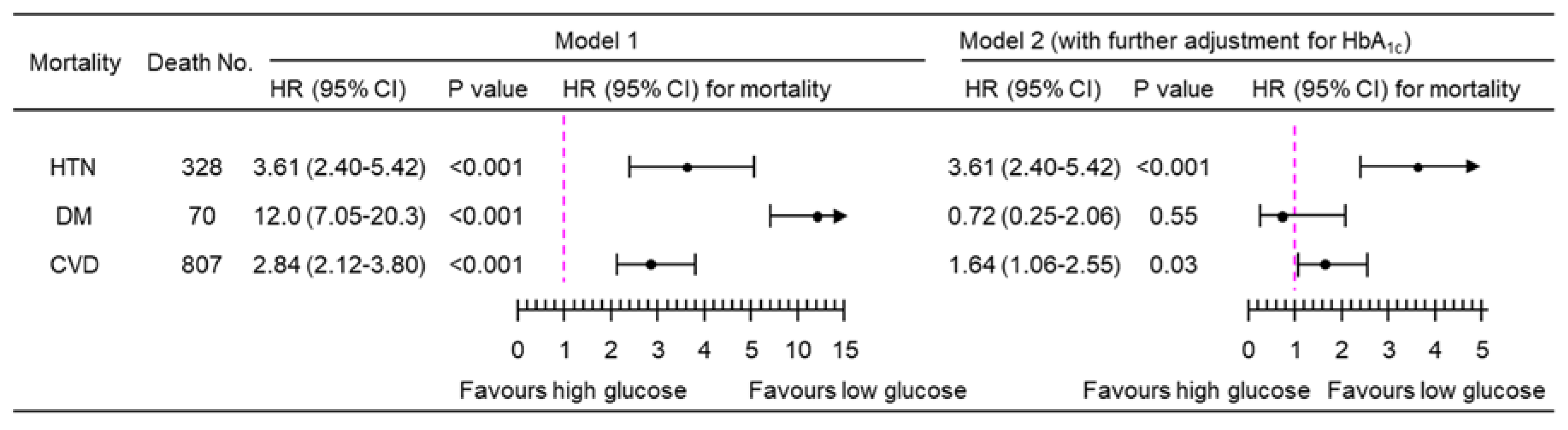

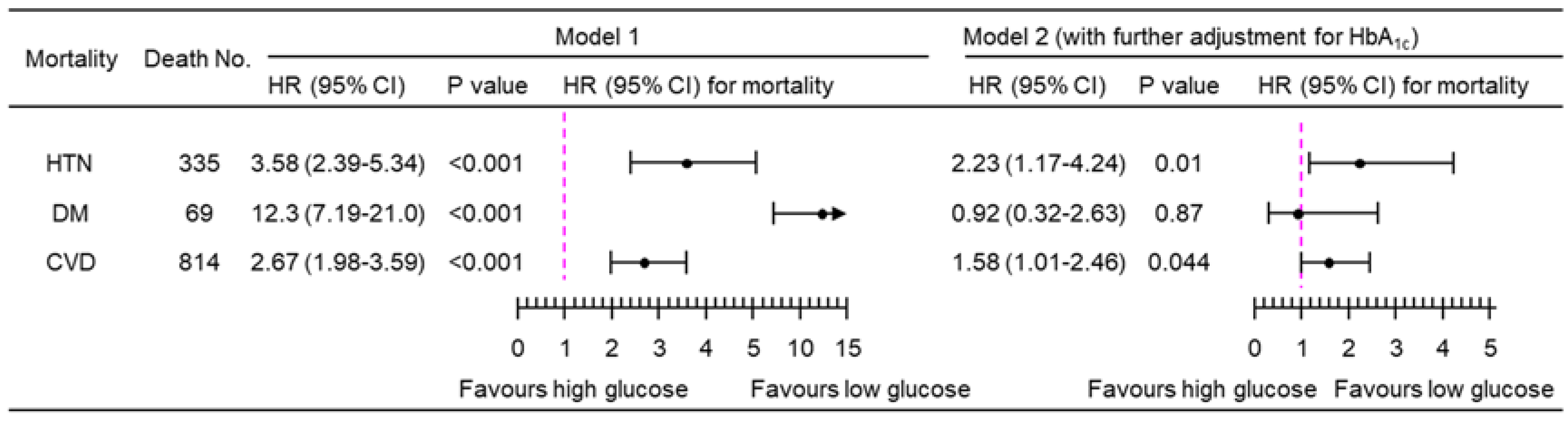

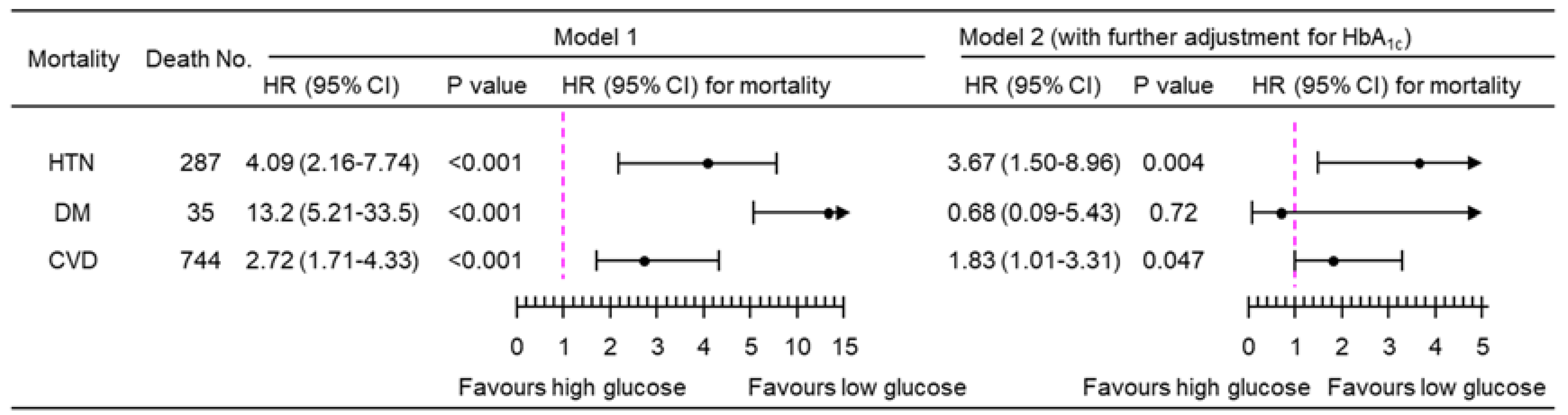

3.2. Association of PPG4-7.9h with Mortality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases. Available from https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases#tab=tab_1. Accessed on 4 January 2024 2023.

- Santos, J.V.; Vandenberghe, D.; Lobo, M.; Freitas, A. Cost of cardiovascular disease prevention: Towards economic evaluations in prevention programs. Annals of Translational Medicine 2020, 8, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birger, M.; Kaldjian, A.S.; Roth, G.A.; Moran, A.E.; Dieleman, J.L.; Bellows, B.K. Spending on Cardiovascular Disease and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in the United States: 1996 to 2016. Circulation 2021, 144, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Key facts-Diabetes. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes. Accessed on 18 October 2023.

- Leon, B.M.; Maddox, T.M. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: Epidemiology, biological mechanisms, treatment recommendations and future research. World J. Diabetes 2015, 6, 1246–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, N.D.; Sattar, N. Cardiovascular risk in diabetes mellitus: Epidemiology, assessment and prevention. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2023, 20, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceriello, A.; Colagiuri, S.; Gerich, J.; Tuomilehto, J. Guideline for management of postmeal glucose. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2008, 18, S17–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter, R.; Okoseime, O.E.; Rees, A.; Owens, D.R. Postprandial glucose - a potential therapeutic target to reduce cardiovascular mortality. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2009, 7, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Postprandial Blood Glucose. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 775–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Y. Late non-fasting plasma glucose predicts cardiovascular mortality independent of hemoglobin A1c. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichenlaub, M.M.; Khovanova, N.A.; Gannon, M.C.; Nuttall, F.Q.; Hattersley, J.G. A Glucose-Only Model to Extract Physiological Information from Postprandial Glucose Profiles in Subjects with Normal Glucose Tolerance. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2022, 16, 1532–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimihodimos, V.; Gonzalez-Villalpando, C.; Meigs, J.B.; Ferrannini, E. Hypertension and Diabetes Mellitus. Hypertension 2018, 71, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Y. Postabsorptive homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance is a reliable biomarker for cardiovascular disease mortality and all-cause mortality. Diabetes Epidemiology and Management 2021, 6, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Magliano, D.J.; Charchar, F.J.; Sobey, C.G.; Drummond, G.R.; Golledge, J. Fasting triglycerides are positively associated with cardiovascular mortality risk in people with diabetes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Witting, P.K.; Charchar, F.J.; Sobey, C.G.; Drummond, G.R.; Golledge, J. Dietary fatty acids and mortality risk from heart disease in US adults: An analysis based on NHANES. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Definition, prevalence, and risk factors of low sex hormone-binding globulin in US adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021, 106, e3946–e3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungo, K.T.; Meier, R.; Valeri, F.; Schwab, N.; Schneider, C.; Reeve, E.; Spruit, M.; Schwenkglenks, M.; Rodondi, N.; Streit, S. Baseline characteristics and comparability of older multimorbid patients with polypharmacy and general practitioners participating in a randomized controlled primary care trial. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. Stage 1 hypertension and risk of cardiovascular disease mortality in United States adults with or without diabetes. J. Hypertens. 2022, 40, 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, Y.; Noguchi, T.; Hayashi, T.; Tomiyama, N.; Ochi, A.; Hayashi, H. Eating alone and weight change in community-dwelling older adults during the coronavirus pandemic: A longitudinal study. Nutrition 2022, 102, 111697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrell, F.E. Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Model. In Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis, Harrell, F.E., Ed. Springer New York: New York, NY, 2001; pp. 465-507. [CrossRef]

- Long, A.N.; Dagogo-Jack, S. Comorbidities of diabetes and hypertension: Mechanisms and approach to target organ protection. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich) 2011, 13, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shariq, O.A.; McKenzie, T.J. Obesity-related hypertension: A review of pathophysiology, management, and the role of metabolic surgery. Gland Surg 2020, 9, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, S.; Gastaldelli, A.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Scherer, P.E. Why does obesity cause diabetes? Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enyew, A.; Nigussie, K.; Mihrete, T.; Jemal, M.; kedir, S.; Alemu, E.; Mohammed, B. Prevalence and associated factors of physical inactivity among adult diabetes mellitus patients in Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, A.U.; Seneviratne, R.A. Physical inactivity, and its association with hypertension among employees in the district of Colombo. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Feng, L.; Bi, Q.; Shi, R.; Cao, H.; Zhang, Y. Fasting Plasma Glucose and Glycated Hemoglobin Levels as Risk Factors for the Development of Hypertension: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2023, 16, 1791–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, P.; Qin, P.; Wang, C.; Ma, J.; Peng, X.; Chen, H.; Zhao, D.; Xu, S.; et al. Association of fasting plasma glucose change trajectory and risk of hypertension: A cohort study in China. Endocr Connect 2022, 11, e210464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Škrha, J.; Šoupal, J.; Škrha, J.; Prázný, M. Glucose variability, HbA1c and microvascular complications. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders 2016, 17, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, E., Jr.; Scism-Bacon, J.L.; Glass, L.C. Oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes: The role of fasting and postprandial glycaemia. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2006, 60, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. 10. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S179–s218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnott, C.; Li, Q.; Kang, A.; Neuen, B.L.; Bompoint, S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Rodgers, A.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Cannon, C.P.; Perkovic, V.; et al. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibition for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 2020, 9, e014908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinman, B.; Wanner, C.; Lachin, J.M.; Fitchett, D.; Bluhmki, E.; Hantel, S.; Mattheus, M.; Devins, T.; Johansen, O.E.; Woerle, H.J.; et al. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2117–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitchett, D.; Butler, J.; van de Borne, P.; Zinman, B.; Lachin, J.M.; Wanner, C.; Woerle, H.J.; Hantel, S.; George, J.T.; Johansen, O.E.; et al. Effects of empagliflozin on risk for cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalization across the spectrum of heart failure risk in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME® trial. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanefeld, M.; Fischer, S.; Julius, U.; Schulze, J.; Schwanebeck, U.; Schmechel, H.; Ziegelasch, H.J.; Lindner, J. Risk factors for myocardial infarction and death in newly detected NIDDM: The Diabetes Intervention Study, 11-year follow-up. Diabetologia 1996, 39, 1577–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takao, T.; Suka, M.; Yanagisawa, H.; Iwamoto, Y. Impact of postprandial hyperglycemia at clinic visits on the incidence of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig 2017, 8, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalot, F.; Pagliarino, A.; Valle, M.; Di Martino, L.; Bonomo, K.; Massucco, P.; Anfossi, G.; Trovati, M. Postprandial blood glucose predicts cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetes in a 14-year follow-up: Lessons from the San Luigi Gonzaga Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 2237–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalot, F.; Petrelli, A.; Traversa, M.; Bonomo, K.; Fiora, E.; Conti, M.; Anfossi, G.; Costa, G.; Trovati, M. Postprandial blood glucose is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular events than fasting blood glucose in type 2 diabetes mellitus, particularly in women: Lessons from the San Luigi Gonzaga Diabetes Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006, 91, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takao, T.; Takahashi, K.; Suka, M.; Suzuki, N.; Yanagisawa, H. Association between postprandial hyperglycemia at clinic visits and all-cause and cancer mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes: A long-term historical cohort study in Japan. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 148, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Q.; Pyörälä, K.; Pyörälä, M.; Nissinen, A.; Lindström, J.; Tilvis, R.; Tuomilehto, J. Two-hour glucose is a better risk predictor for incident coronary heart disease and cardiovascular mortality than fasting glucose. Eur. Heart J. 2002, 23, 1267–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, E.L.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Welborn, T.A.; Jolley, D.; Magliano, D.J.; Dunstan, D.W.; Cameron, A.J.; Dwyer, T.; Taylor, H.R.; Tonkin, A.M.; et al. Risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in individuals with diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance: The Australian Diabetes, Obesity, and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab). Circulation 2007, 116, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.E.; Barrett-Connor, E.; Wassel, C.L.; Kanaya, A.M. Association of glucose measures with total and coronary heart disease mortality: Does the effect change with time? The Rancho Bernardo Study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2009, 86, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.L.; Pareek, M.; Leósdóttir, M.; Eriksson, K.F.; Nilsson, P.M.; Olsen, M.H. One-hour glucose value as a long-term predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality: The Malmö Preventive Project. Eur J Endocrinol 2018, 178, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjaden, A.H.; Edelstein, S.L.; Arslanian, S.; Barengolts, E.; Caprio, S.; Cree-Green, M.; Lteif, A.; Mather, K.J.; Savoye, M.; Xiang, A.H.; et al. Reproducibility of Glycemic Measures Among Dysglycemic Youth and Adults in the RISE Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2023, 108, e1125–e1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darras, P.; Mattman, A.; Francis, G.A. Nonfasting lipid testing: The new standard for cardiovascular risk assessment. CMAJ 2018, 190, E1317–E1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundy, S.M.; Stone, N.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Beam, C.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Braun, L.T.; Ferranti, S.d.; Faiella-Tommasino, J.; Forman, D.E.; et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019, 139, e1082–e1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. Higher fasting triglyceride predicts higher risks of diabetes mortality in US adults. Lipids Health Dis. 2021, 20, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menke, A.; Muntner, P.; Batuman, V.; Silbergeld, E.K.; Guallar, E. Blood lead below 0.48 micromol/L (10 microg/dL) and mortality among US adults. Circulation 2006, 114, 1388–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMahon, S.; Peto, R.; Cutler, J.; Collins, R.; Sorlie, P.; Neaton, J.; Abbott, R.; Godwin, J.; Dyer, A.; Stamler, J. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, Prolonged differences in blood pressure: Prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet 1990, 335, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).