Submitted:

05 January 2024

Posted:

08 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

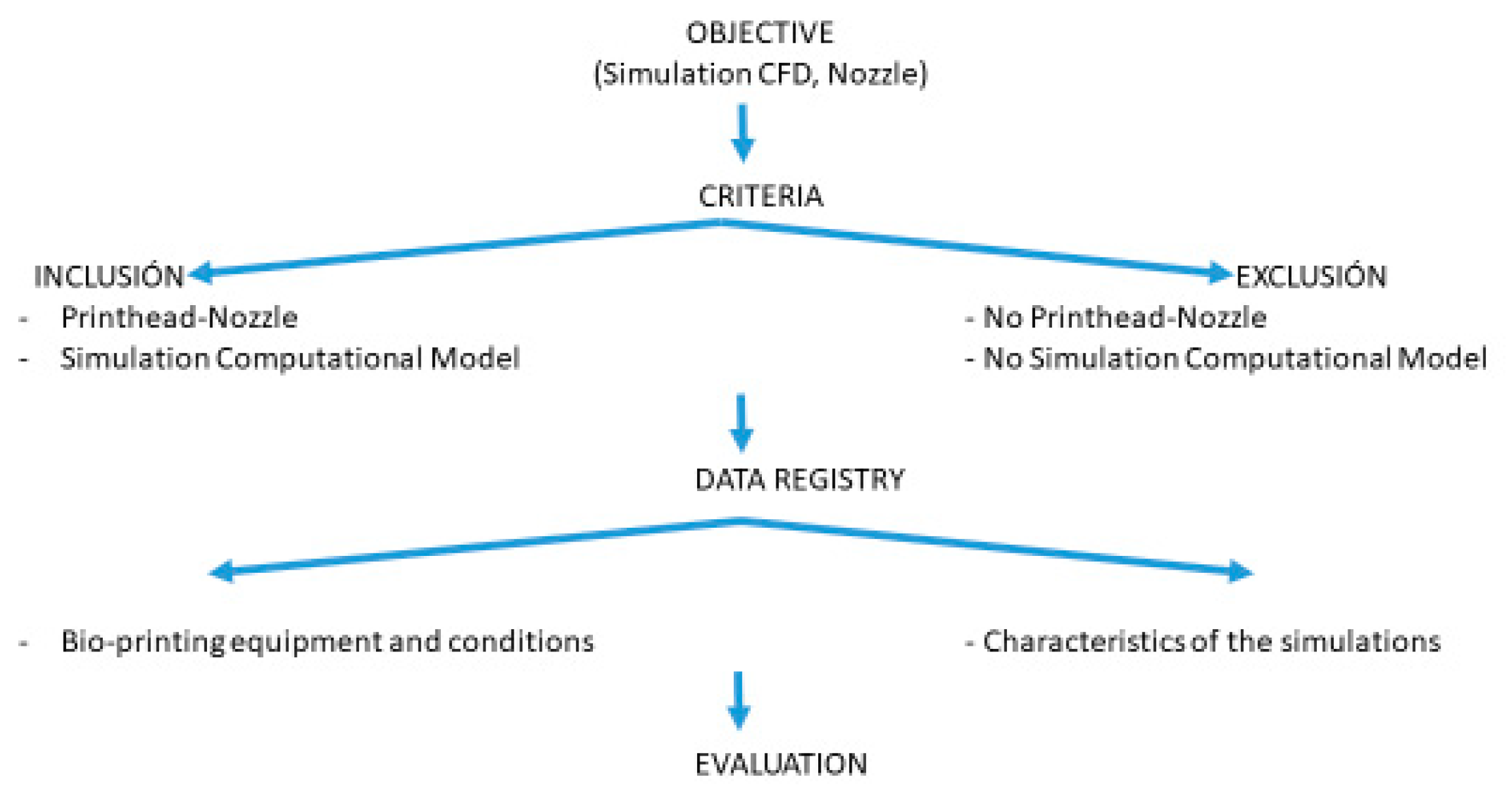

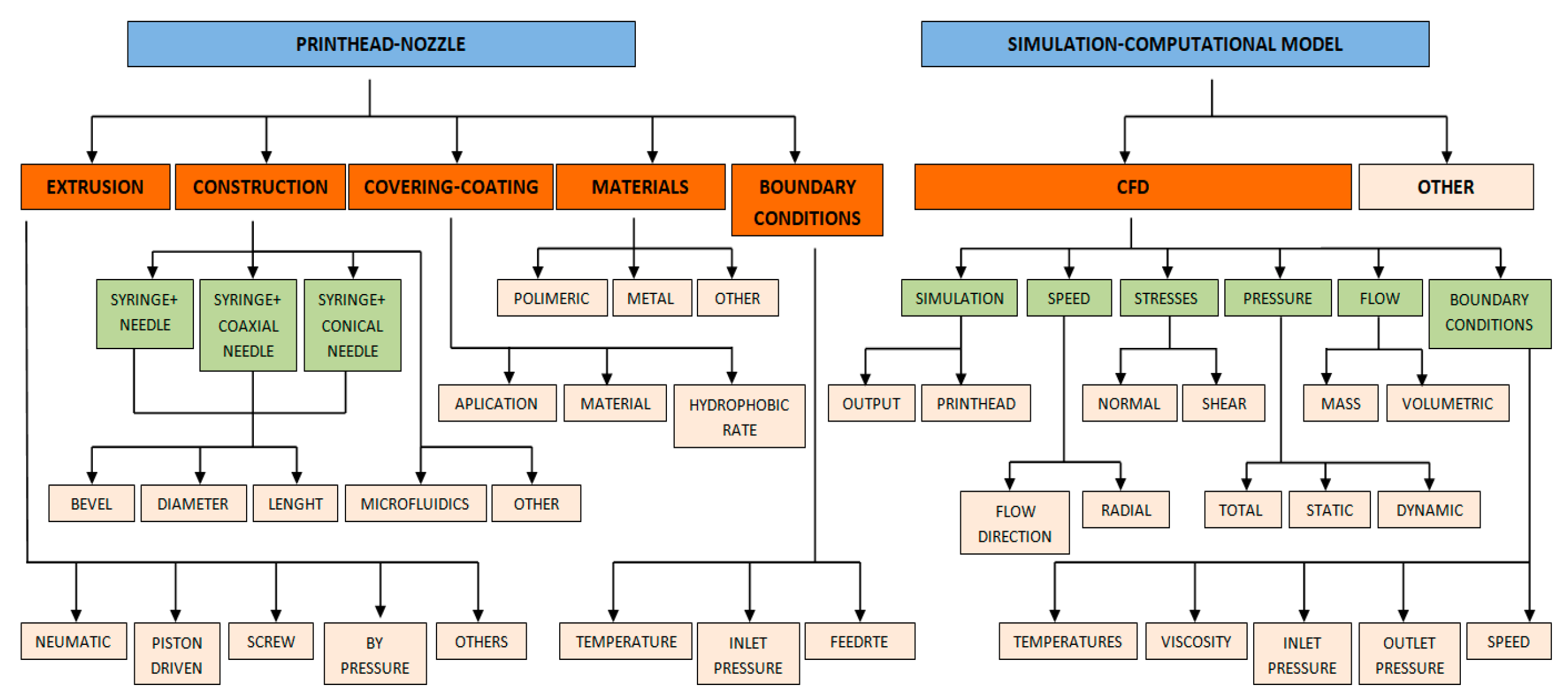

2.1. Systematic Review

- A concise definition of the topic to be addressed:

- Specification of inclusion and exclusion criteria:

- Data recording and quality assessment of the selected articles:

- Interpretation and presentation of results:

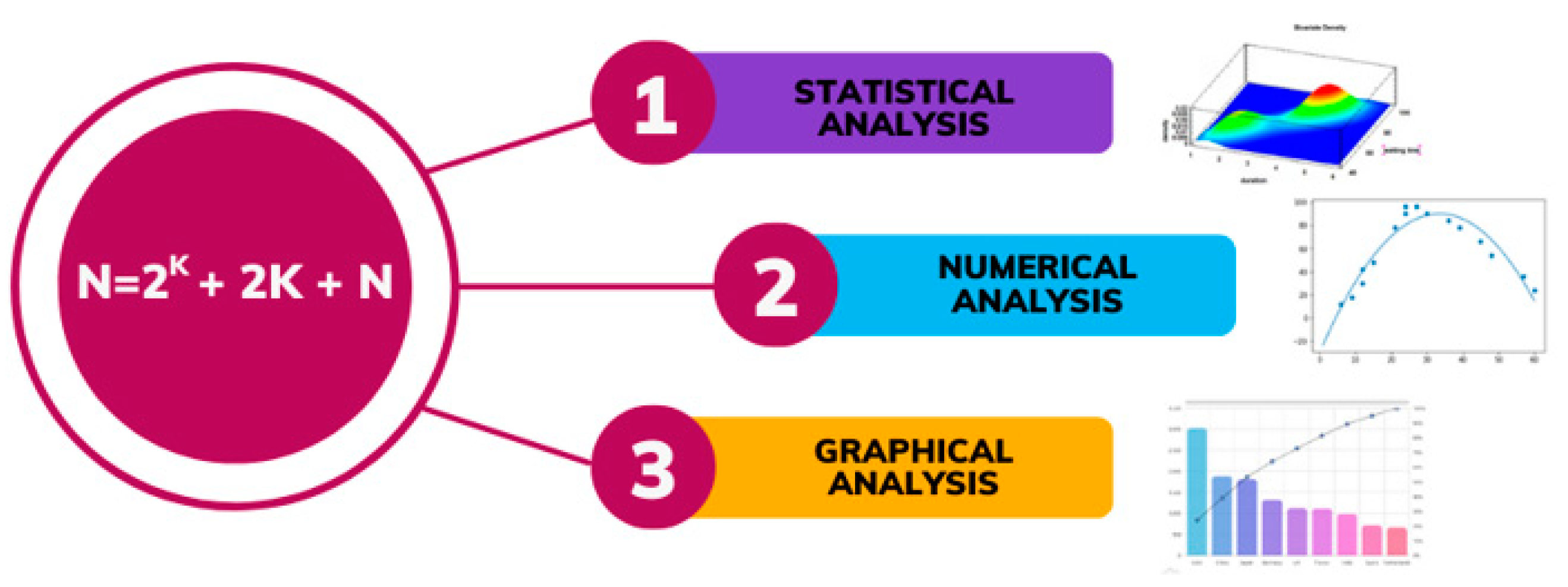

2.2. Design of Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

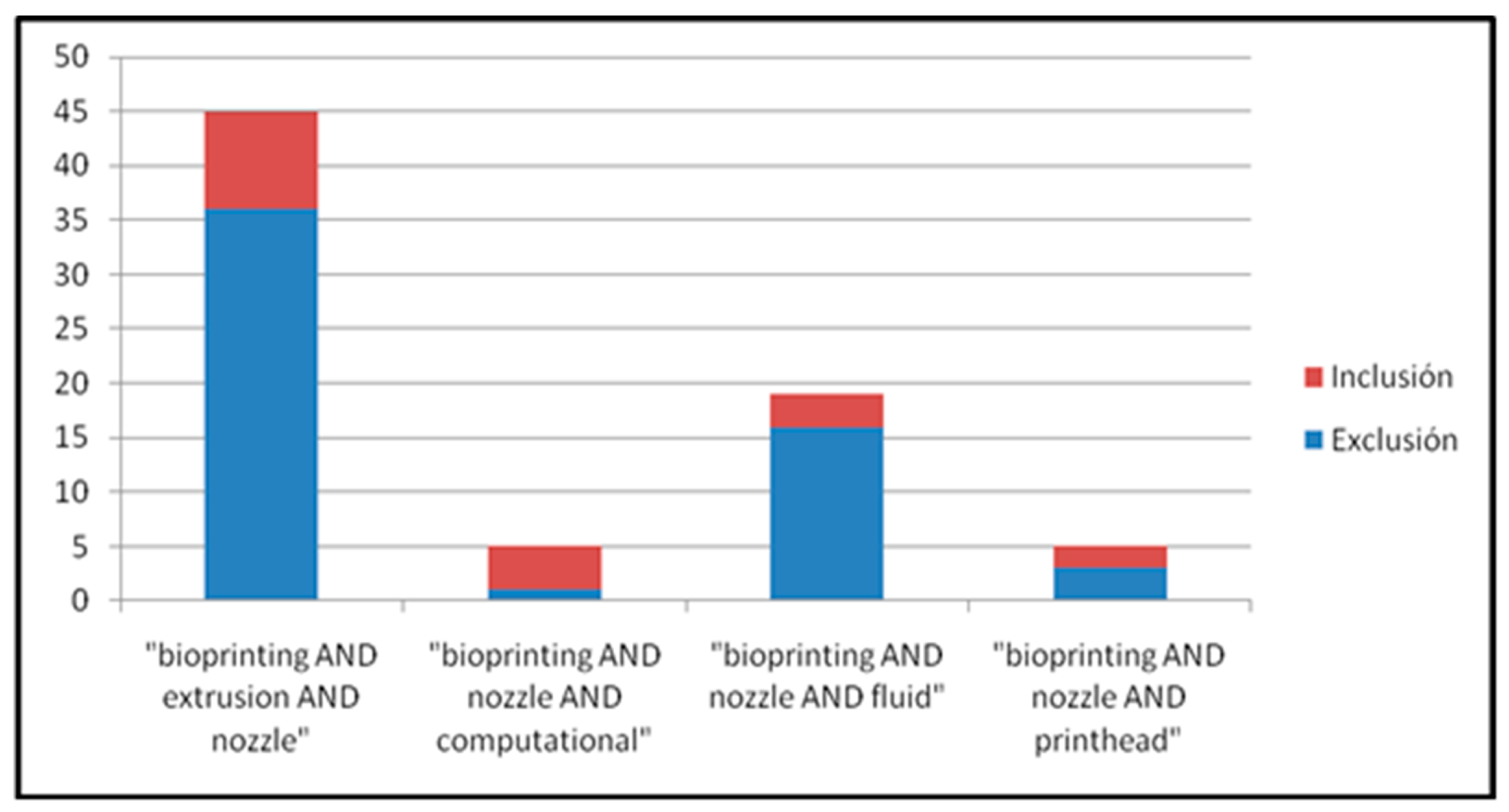

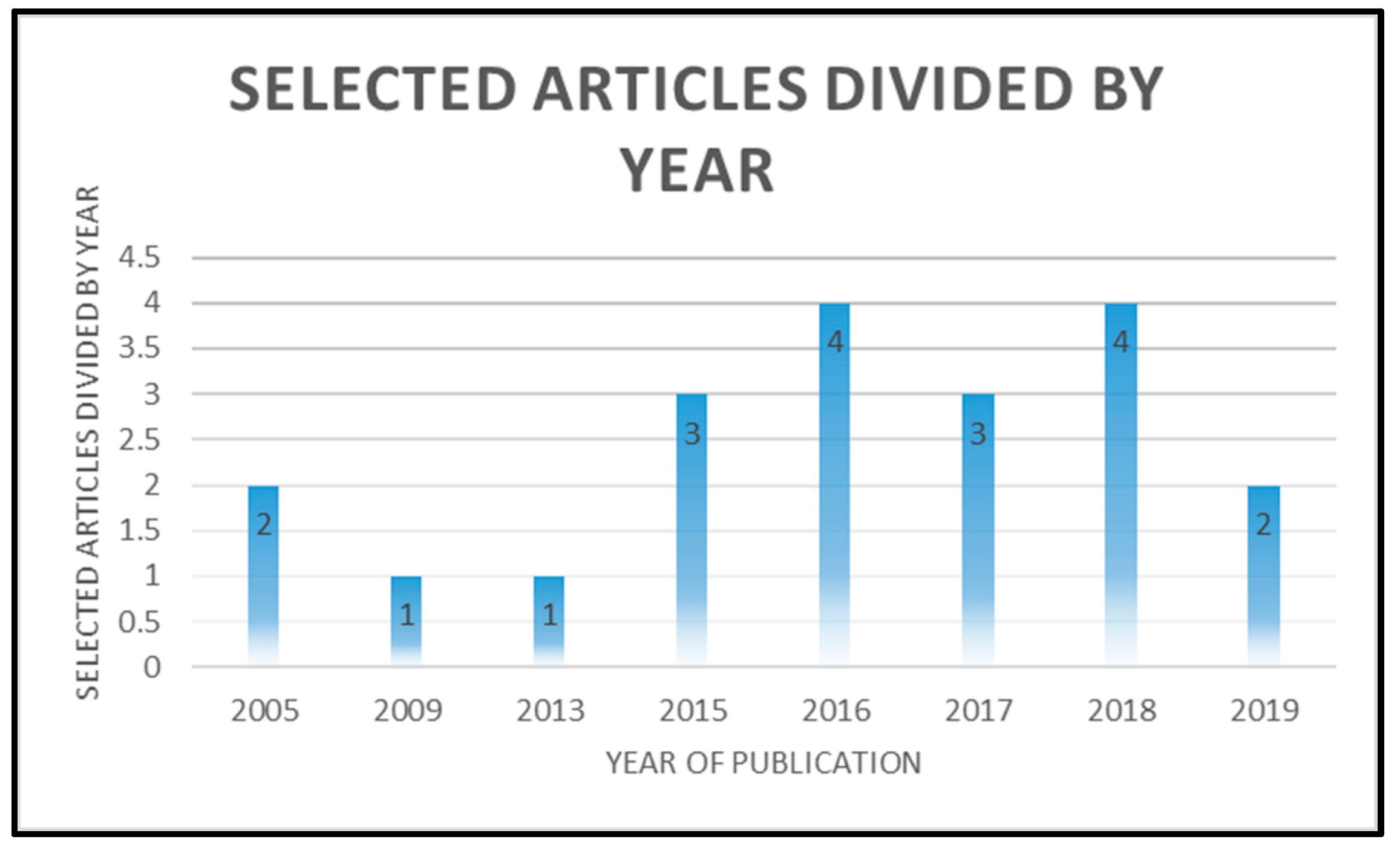

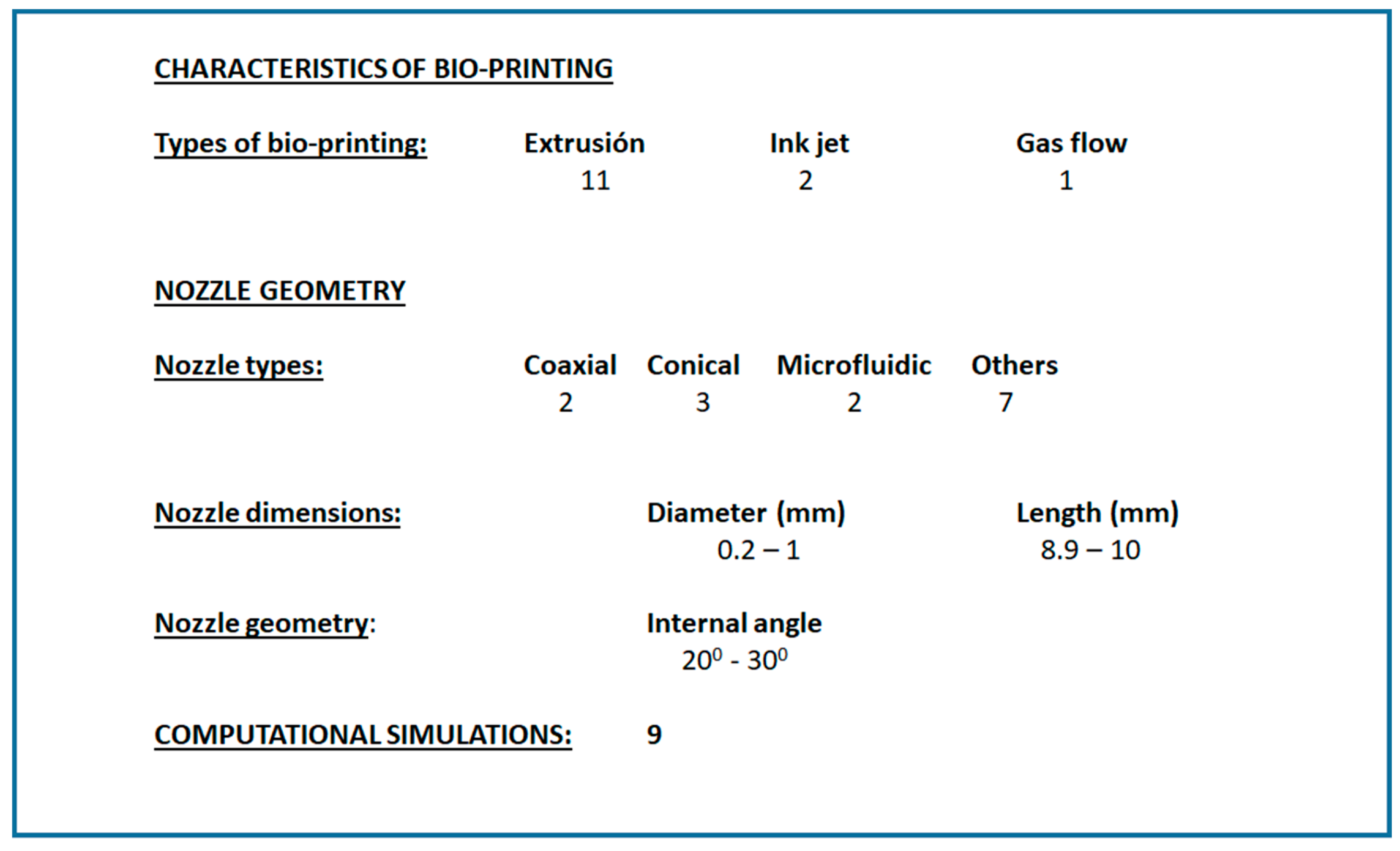

3.1. Systematic Review Analysis

- “bioprinting AND extrusion AND nozzle”.

- “bioprinting AND nozzle AND computational”.

- “bioprinting AND nozzle AND fluid”.

- “bioprinting AND nozzle AND printhead”.

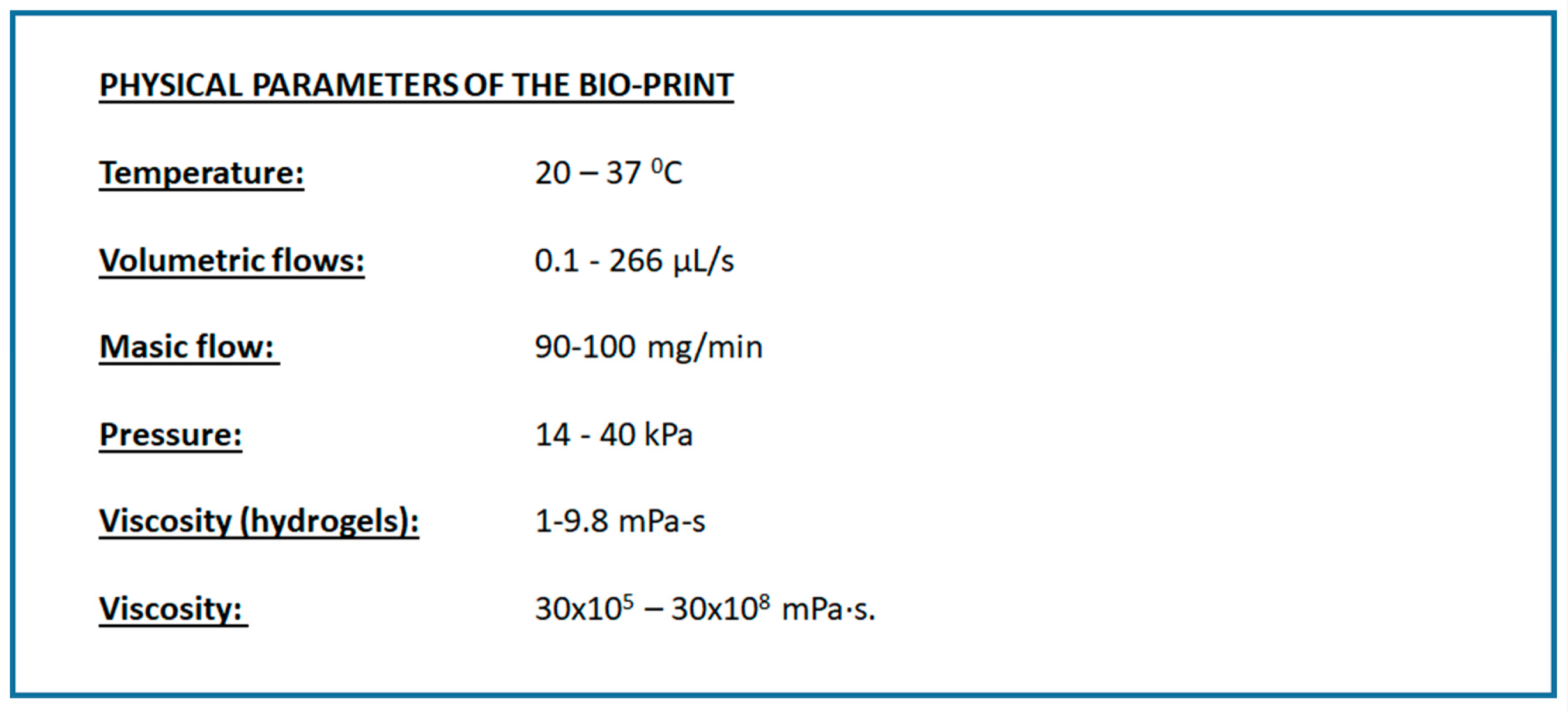

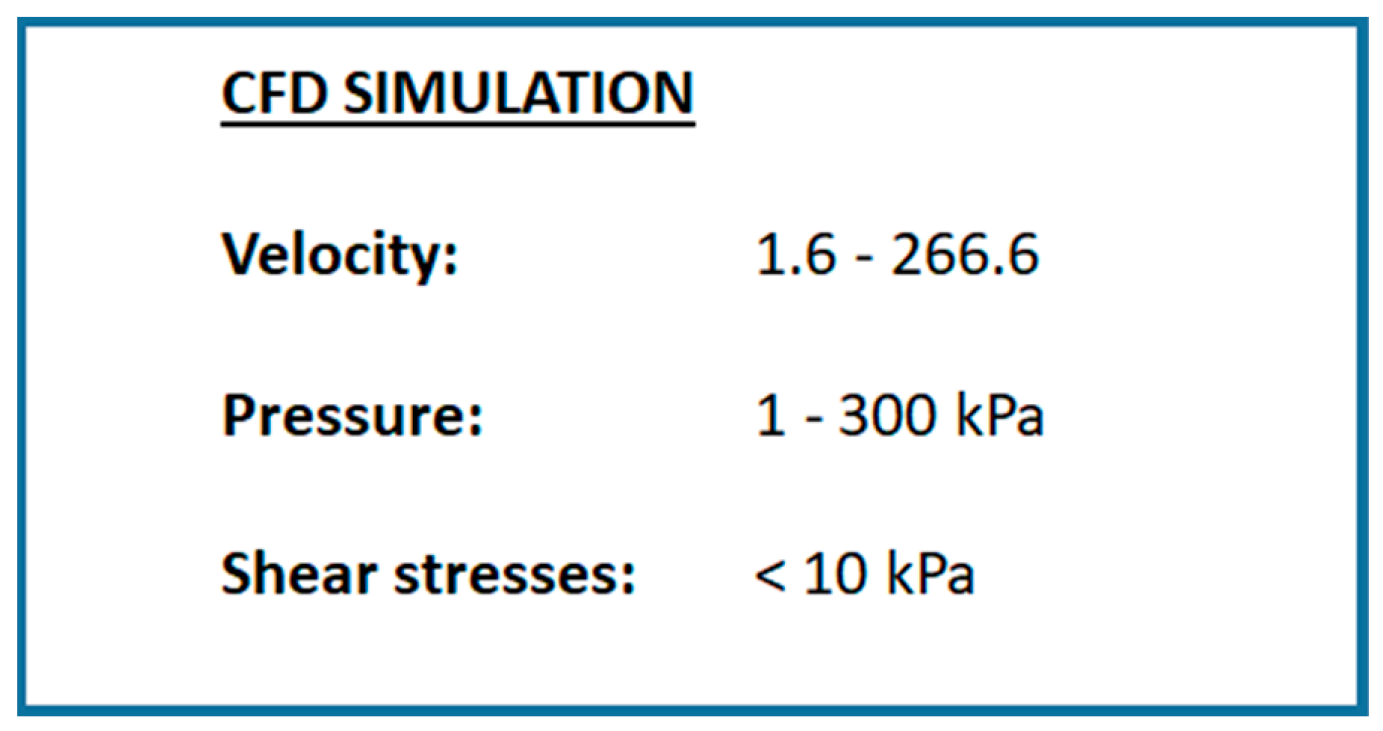

3.2. Design of Experiments

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- F. Pati, J. Gantelius, and H. A. Svahn, “3D bioprinting of tissue/organ models,” Angew. Chemie Int. Ed., vol. 55, no. 15, pp. 4650–4665, 2016.

- S. Derakhshanfar, R. Mbeleck, K. Xu, X. Zhang, W. Zhong, and M. Xing, “3D bioprinting for biomedical devices and tissue engineering: A review of recent trends and advances,” Bioact. Mater., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 144–156, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Kyle, Z. M. Jessop, A. Al-Sabah, and I. S. Whitaker, “‘Printability’’ of Candidate Biomaterials for Extrusion Based 3D Printing: State-of-the-Art,’” Adv. Healthc. Mater., vol. 6, no. 16, 2017. [CrossRef]

- O. A. Beltrán, “Revisiones sistemáticas de la literatura,” Rev. Colomb. Gastroenterol., vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 60–69, 2005.

- A. Panwar and L. P. Tan, “Current status of bioinks for micro-extrusion-based 3D bioprinting,” Molecules, vol. 21, no. 6, 2016. [CrossRef]

- I. T. Ozbolat and M. Hospodiuk, “Current advances and future perspectives in extrusion-based bioprinting,” Biomaterials, vol. 76, pp. 321–343, 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. De Maria et al., “Design and validation of an open-hardware print-head for bioprinting application,” Procedia Eng., vol. 110, pp. 98–105, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Shi, B. Wu, S. Li, J. Song, B. Song, and W. F. Lu, “Shear stress analysis and its effects on cell viability and cell proliferation in drop-on-demand bioprinting,” Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express, vol. 4, no. 4, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Ponce-Torres, E. Ortega, M. Rubio, A. Rubio, E. J. Vega, and J. M. Montanero, “Gaseous flow focusing for spinning micro and nanofibers,” Polymer (Guildf)., vol. 178, p. 121623, 2019.

- Q. Gao, Y. He, J. zhong Fu, A. Liu, and L. Ma, “Coaxial nozzle-assisted 3D bioprinting with built-in microchannels for nutrients delivery,” Biomaterials, vol. 61, pp. 203–215, 2015. [CrossRef]

- W. Martanto, S. M. Baisch, E. A. Costner, M. R. Prausnitz, and M. K. Smith, “Fluid dynamics in conically tapered microneedles,” AIChE J., vol. 51, no. 6, pp. 1599–1607, 2005.

- J. Göhl, K. Markstedt, A. Mark, K. Håkansson, P. Gatenholm, and F. Edelvik, “Simulations of 3D bioprinting: Predicting bioprintability of nanofibrillar inks,” Biofabrication, vol. 10, no. 3, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Kang et al., “Pre-set extrusion bioprinting for multiscale heterogeneous tissue structure fabrication,” Biofabrication, vol. 10, no. 3, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Attalla, E. Puersten, N. Jain, and P. R. Selvaganapathy, “3D bioprinting of heterogeneous bi- and tri-layered hollow channels within gel scaffolds using scalable multi-axial microfluidic extrusion nozzle,” Biofabrication, vol. 11, no. 1, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. H. Kang, L. A. Hockaday, and J. T. Butcher, “Quantitative optimization of solid freeform deposition of aqueous hydrogels,” Biofabrication, vol. 5, no. 3, p. 35001, 2013.

- C. A. Parzel, M. E. Pepper, T. Burg, R. E. Groff, and K. J. L. Burg, “EDTA enhances high-throughput two-dimensional bioprinting by inhibiting salt scaling and cell aggregation at the nozzle surface,” J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med., vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 260–268, 2009.

- K. Pusch, T. J. Hinton, and A. W. Feinberg, “Large volume syringe pump extruder for desktop 3D printers,” HardwareX, vol. 3, no. February, pp. 49–61, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Suntornnond, E. Y. S. Tan, J. An, and C. K. Chua, “A Mathematical Model on the Resolution of Extrusion Bioprinting for the Development of New Bioinks,” Materials (Basel)., vol. 9, no. 9, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Ponce-Torres, E. J. Vega, A. A. Castrejón-Pita, and J. M. Montanero, “Smooth printing of viscoelastic microfilms with a flow focusing ejector,” J. Nonnewton. Fluid Mech., vol. 249, pp. 1–7, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Reid, P. A. Mollica, G. D. Johnson, R. C. Ogle, R. D. Bruno, and P. C. Sachs, “Accessible bioprinting: Adaptation of a low-cost 3D-printer for precise cell placement and stem cell differentiation,” Biofabrication, vol. 8, no. 2, 2016. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Central | Step | Maximum | Minimum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (T) | 28,50 | 4,25 | 37 | 20 |

| Volumetric flow (V) | 133,050 | 66,475 | 266 | 0.1 |

| Pressure (P) | 27 | 6.5 | 40 | 14 |

| Viscosity (v) | 1,515·108 | 0,7425·108 | 30·108 | 30·105 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).