Submitted:

04 January 2024

Posted:

08 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Descriptive attributes of cohorts and study populations

2.2. Cell isolation

2.3. Antibodies for immune-phenotype

2.4. Flow cytometric analysis

2.5. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

2.6. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Co-IRs expression on T cells characterization with Taiwanese RA

| Markers | Mean±SD (Number) | P Value | |

| RA | Normal | ||

| CD4+CD279+TIM3+ | 0.5702 ± 0.08012 (47) | 0.3667 ± 0.0859 (27) | 0.1057 |

| CD4+CTLA4+LAG3+ | 0.1234 ± 0.02512 (47) | 0.07037 ± 0.02123 (27) | 0.1549 |

| CD4+CD127+TIGIT+ | 4.458 ± 0.5114 (48) | 5.041 ± 0.6587 (27) | 0.4914 |

| CD8+CD279+TIM3+ | 0.3413 ± 0.08567 (46) | 0.08077 ± 0.01666 (26) | 0.0265 |

| CD8+CTLA4+LAG3+ | 0.01667 ± 0.005436 (48) | 0.007407 ± 0.005136 (27) | 0.2635 |

| CD8+CD127+TIGIT+ | 2.896 ± 0.3579 (47) | 2.426 ± 0.4004 (27) | 0.4057 |

| CD8+CD160+CD244+ | 0.3596 ± 0.08051 (47) | 0.432 ± 0.1224 (25) | 0.6114 |

| CD8+HLA-DR+CD127+ | 1.016 ± 0.2676 (19) | 1.716 ± 0.3932 (19) | 0.1497 |

| CD8+HLA-DR+CD38+ | 9.191 ± 1.341 (47) | 4.519 ± 0.8416 (27) | 0.0155 |

| CD3+CD160+CD244+ | 0.8298 ± 0.2617 (47) | 0.4444 ± 0.2109 (27) | 0.3153 |

| CD3+CD279+TIGIT+ | 4.359 ± 0.5808 (46) | 2.408 ± 0.3742 (26) | 0.0207 |

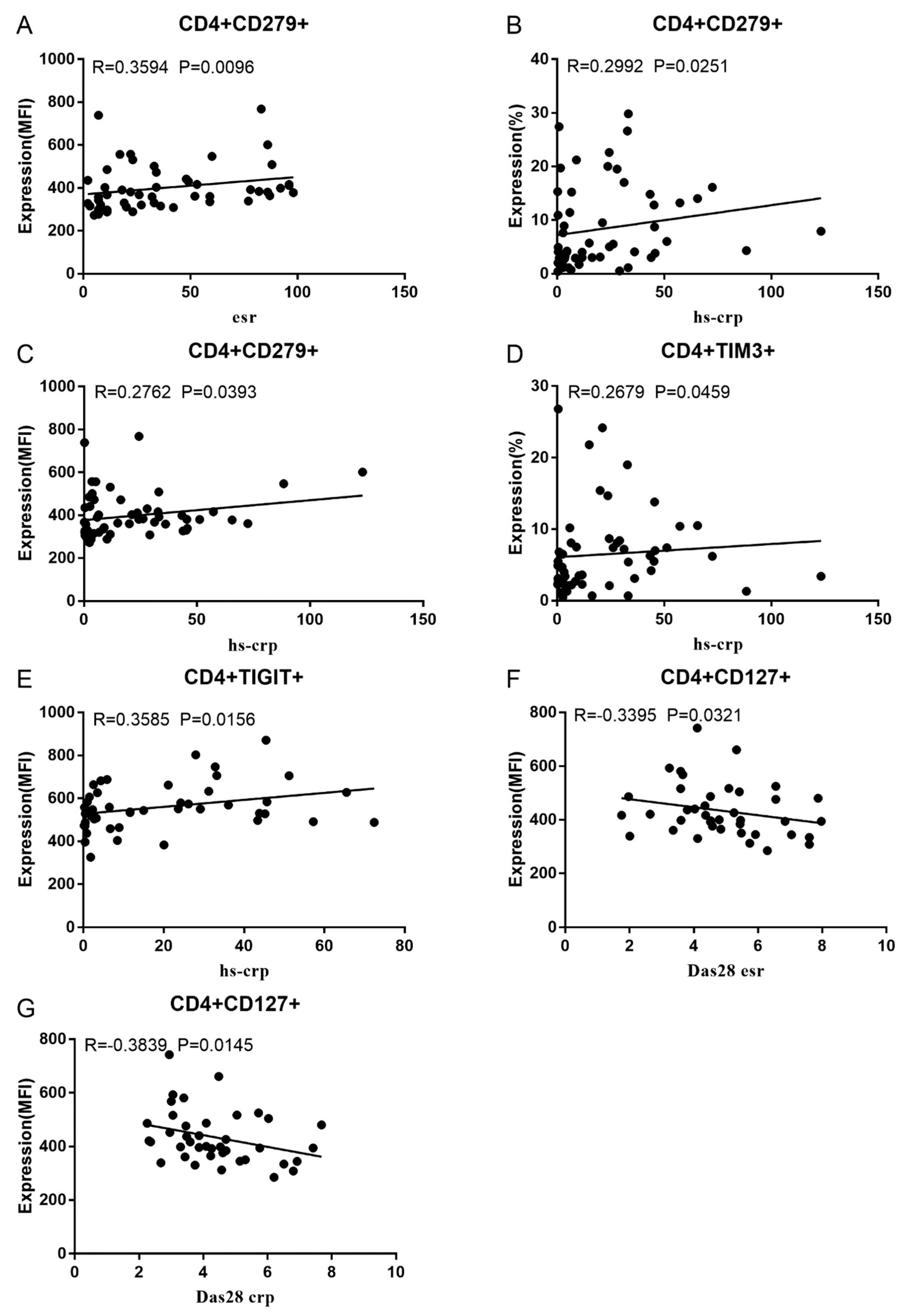

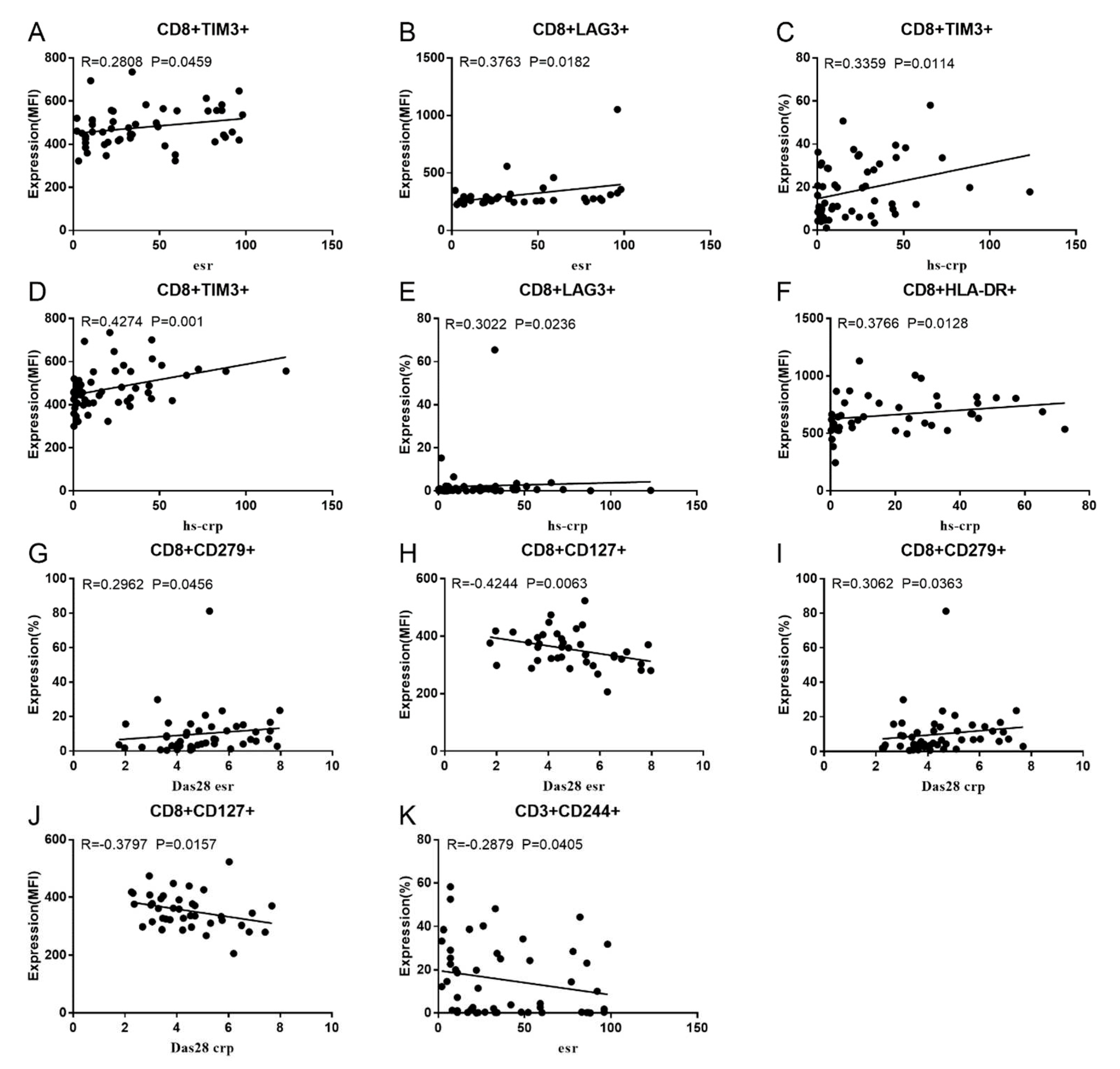

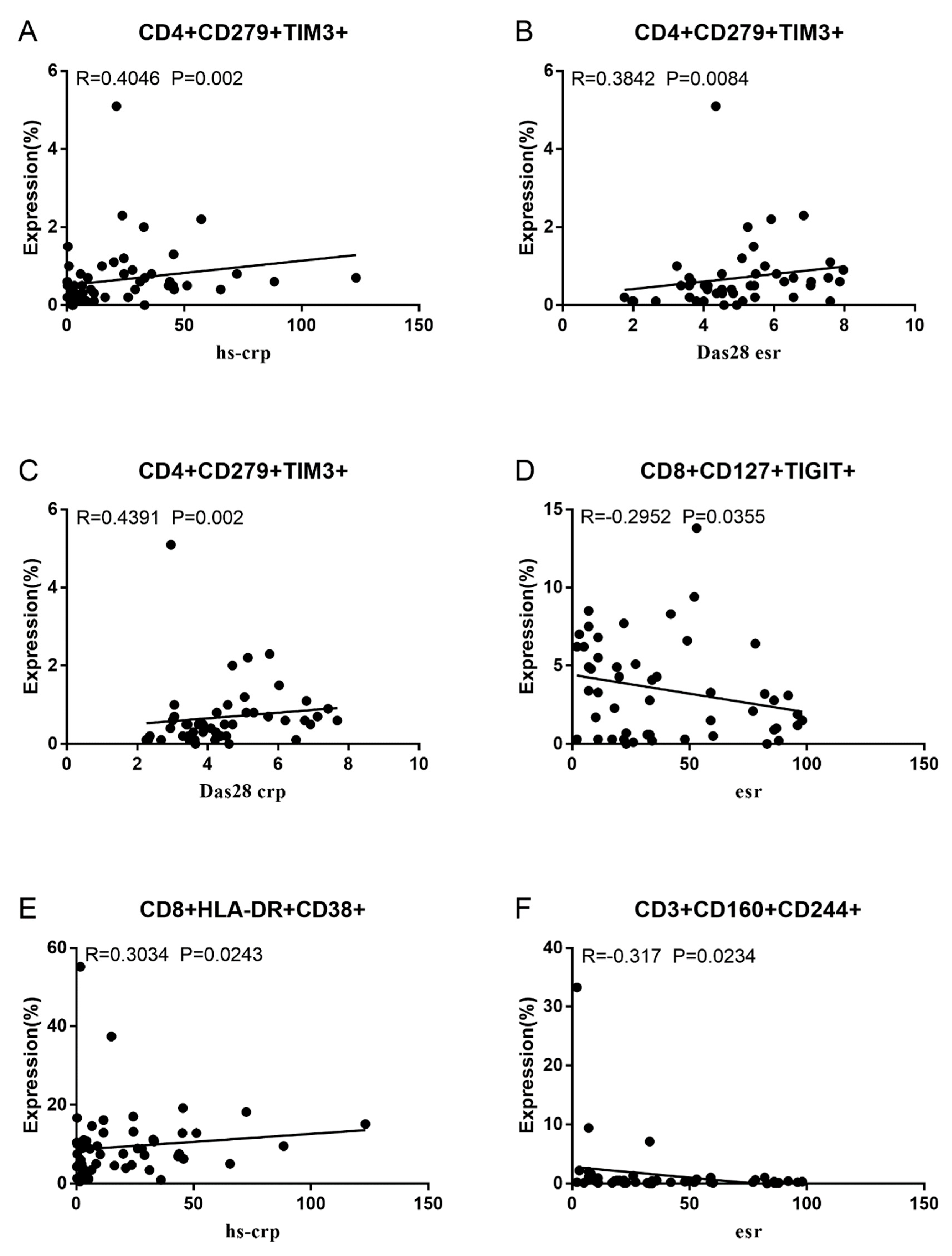

3.2. Correlation between RA Disease Activity and Co-IRs expression on T cells

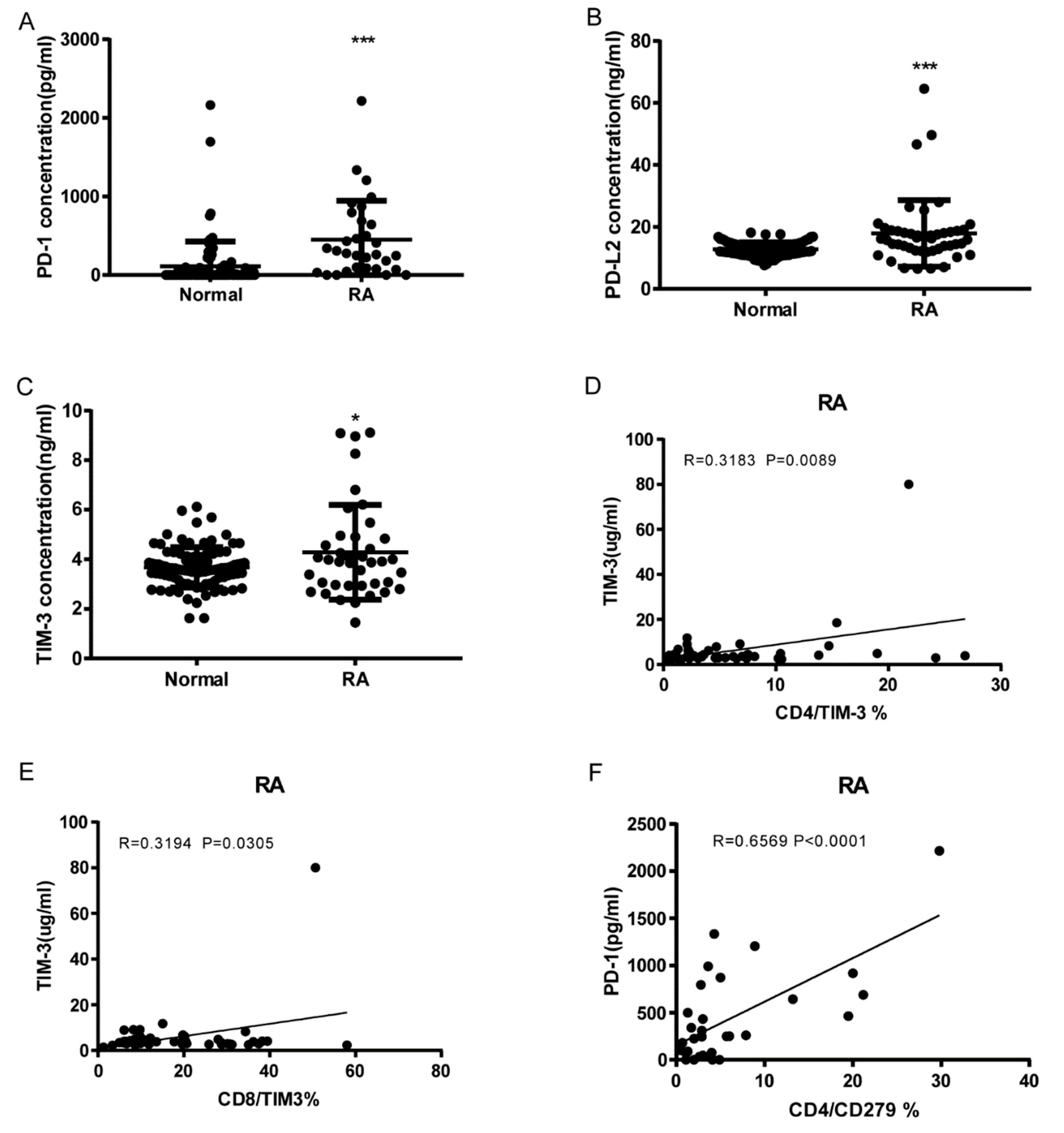

3.3. Soluble PD1, PDL-2 and Tim3 levels in RA and correlation to cell expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McInnes, I. B.; Schett, G. , Pathogenetic insights from the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet (London, England) 2017, 389, 10086,2328–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, E. , Understanding the dynamics: pathways involved in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 5. 2012, 51 Suppl 5, v3-11.. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellado, M.; Martinez-Munoz, L.; Cascio, G.; Lucas, P.; Pablos, J. L.; Rodriguez-Frade, J. M. , T Cell Migration in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Frontiers in immunology 2015, 6, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, S. K.; Cho, M. L.; Park, M. K.; Oh, H. J.; Park, J. S.; Her, Y. M.; Lee, S. Y.; Youn, J.; Ju, J. H.; Park, K. S.; Kim, S. I.; Kim, H. Y.; Park, S. H. , Interleukin-21 promotes osteoclastogenesis in humans with rheumatoid arthritis and in mice with collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism 2012, 3, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firestein, G. S.; McInnes, I. B. , Immunopathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Immunity 2017, 2, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wherry, E. J.; Kurachi, M. , Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nature reviews. Immunology 2015, 8, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maecker, H. T.; McCoy, J. P.; Nussenblatt, R. , Standardizing immunophenotyping for the Human Immunology Project. Nature reviews. Immunology 2012, 3, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, M.; Dubey, C. Accessory Molecule and Costimulation Requirements for CD4 T Cell Response. Critical reviews in immunology 2017, 37, 2-6, 261-290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raptopoulou, A. P.; Bertsias, G.; Makrygiannakis, D.; Verginis, P.; Kritikos, I.; Tzardi, M.; Klareskog, L.; Catrina, A. I.; Sidiropoulos, P.; Boumpas, D. T. , The programmed death 1/programmed death ligand 1 inhibitory pathway is up-regulated in rheumatoid synovium and regulates peripheral T cell responses in human and murine arthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism 2010, 7, 1870–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Ye, J.; Zeng, L.; Luo, Z.; Deng, Z.; Li, X.; Guo, Y.; Huang, Z.; Li, J. , Elevated expression of PD-1 on T cells correlates with disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Molecular medicine reports 2018, 2, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohini, Z.; Hossein-Nataj, H.; Mobini, M.; Hosseinian-Amiri, A.; Rafiei, A.; Asgarian-Omran, H. , Analysis of PD-1 and Tim-3 expression on CD4(+) T cells of patients with rheumatoid arthritis; negative association with DAS28. Clinical rheumatology 2018, 8, 2063–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldridge, J.; Andersson, K.; Gjertsson, I.; Hultgård Ekwall, A. K.; Hallström, M.; van Vollenhoven, R.; Lundell, A. C.; Rudin, A. Blood PD-1+TFh and CTLA-4+CD4+ T cells predict remission after CTLA-4Ig treatment in early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2022, 61, 3, 1233-1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Chi, S.; Wang, X.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y. , CD4+CXCR5+PD-1+ T Follicular Helper Cells Play a Pivotal Role in the Development of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research 2019, 25, 3032–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, L. M.; Li, J.; Ji, L. L.; Li, G. T.; Zhang, Z. L. , [Detection of peripheral follicular helper T cells in rheumatoid arthritis]. Beijing da xue xue bao. Yi xue ban = Journal of Peking University. Health sciences 2016, 48, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Shan, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Feng, J.; Li, C.; Ma, L.; Jiang, Y. , High frequencies of activated B cells and T follicular helper cells are correlated with disease activity in patients with new-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical and experimental immunology 2013, 2, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, D. A. , T Cells That Help B Cells in Chronically Inflamed Tissues. Frontiers in immunology 2018, 9, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, D. A.; Gurish, M. F.; Marshall, J. L.; Slowikowski, K.; Fonseka, C. Y.; Liu, Y.; Donlin, L. T.; Henderson, L. A.; Wei, K.; Mizoguchi, F.; Teslovich, N. C.; Weinblatt, M. E.; Massarotti, E. M.; Coblyn, J. S.; Helfgott, S. M.; Lee, Y. C.; Todd, D. J.; Bykerk, V. P.; Goodman, S. M.; Pernis, A. B.; Ivashkiv, L. B.; Karlson, E. W.; Nigrovic, P. A.; Filer, A.; Buckley, C. D.; Lederer, J. A.; Raychaudhuri, S.; Brenner, M. B. , Pathologically expanded peripheral T helper cell subset drives B cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Nature 2017, 7639, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Li, Z.; Zeng, X.; Xia, C.; Xu, L.; Xu, Q.; Song, Y.; Liu, C. , Circulating CD4(+) FoxP3(-) CXCR5(-) CXCR3(+) PD-1(hi) cells are elevated in active rheumatoid arthritis and reflect the severity of the disease. International journal of rheumatic diseases 2021, 8, 1032–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortea-Gordo, P.; Nuño, L.; Villalba, A.; Peiteado, D.; Monjo, I.; Sánchez-Mateos, P.; Puig-Kröger, A.; Balsa, A.; Miranda-Carús, M. E. , Two populations of circulating PD-1hiCD4 T cells with distinct B cell helping capacity are elevated in early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2019, 58, 1662–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, C.; Xu, F.; Qi, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, P. , Imbalance of circulating Tfr/Tfh ratio in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical and experimental medicine 2019, 1, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Wang, P.; Cui, Z.; Yue, X.; Chi, S.; Ma, A.; Zhang, Y. , An imbalance between blood CD4(+)CXCR5(+)Foxp3(+) Tfr cells and CD4(+)CXCR5(+)Tfh cells may contribute to the immunopathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Molecular immunology 2020, 125, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, R.; Wang, Y.; Hu, F.; Li, B.; Guo, Q.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Y.; Gao, C.; Li, X.; Wang, C. , Altered Distribution of Circulating T Follicular Helper-Like Cell Subsets in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Frontiers in medicine 2021, 8, 690100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashioka, K.; Yoshimura, M.; Sakuragi, T.; Ayano, M.; Kimoto, Y.; Mitoma, H.; Ono, N.; Arinobu, Y.; Kikukawa, M.; Yamada, H.; Horiuchi, T.; Akashi, K.; Niiro, H. , Human PD-1(hi)CD8(+) T Cells Are a Cellular Source of IL-21 in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 654623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasen, C.; Turkkila, M.; Bossios, A.; Erlandsson, M.; Andersson, K. M.; Ekerljung, L.; Malmhall, C.; Brisslert, M.; Toyra Silfversward, S.; Lundback, B.; Bokarewa, M. I. , Smoking activates cytotoxic CD8(+) T cells and causes survivin release in rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of autoimmunity 2017, 78, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartosinska, J.; Zakrzewska, E.; Krol, A.; Raczkiewicz, D.; Purkot, J.; Majdan, M.; Krasowska, D.; Chodorowska, G.; Giannopoulos, K. , Differential expression of programmed death 1 (PD-1) on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Polish archives of internal medicine 2017, 12, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.; Wang, Y.; Sui, Y.; Sun, J.; Li, D.; Li, G.; Liu, J.; Li, T.; Shu, Q. , High Interleukin-37 (IL-37) Expression and Increased Mucin-Domain Containing-3 (TIM-3) on Peripheral T Cells in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research 2018, 24, 5660–5667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shu, Q.; Gao, L.; Hou, N.; Zhao, D.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, L.; Yue, X.; Zhu, F.; Guo, C.; Liang, X.; Ma, C. , Increased Tim-3 expression on peripheral lymphocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis negatively correlates with disease activity. Clinical immunology (Orlando, Fla.) 2010, 2, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Peng, D.; He, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, H.; Shan, S.; Song, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, H.; Song, H.; Zhang, M. Expression of TIM-3 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood and synovial fluid of rheumatoid arthritis. APMIS : acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica 2014, 122, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skejoe, C.; Hansen, A. S.; Stengaard-Pedersen, K.; Junker, P.; Hoerslev-Pedersen, K.; Hetland, M. L.; Oestergaard, M.; Greisen, S.; Hvid, M.; Deleuran, M.; Deleuran, B. , T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 is upregulated in rheumatoid arthritis, but insufficient in controlling inflammation. American journal of clinical and experimental immunology 2022, 3, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa, M.; Suzuki, K.; Takeshita, M.; Inamo, J.; Kamata, H.; Ishii, M.; Oyamada, Y.; Oshima, H.; Takeuchi, T. , Distinct Expression of Coinhibitory Molecules on Alveolar T Cells in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis-Associated and Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathy-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.) 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q.; Deng, Z.; Xu, C.; Zeng, L.; Ye, J.; Li, X.; Guo, Y.; Huang, Z.; Li, J. Elevated Expression of Immunoreceptor Tyrosine-Based Inhibitory Motif (TIGIT) on T Lymphocytes is Correlated with Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research 2017, 23, 1232–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, C.; Gao, S.; Li, S.; Xing, Z.; Qian, H.; Hu, Y.; Wang, W.; Hua, C. , TIGIT as a Promising Therapeutic Target in Autoimmune Diseases. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 911919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Dong, Y.; Wu, C.; Ma, Y.; Jin, Y.; Ji, Y. , TIGIT overexpression diminishes the function of CD4 T cells and ameliorates the severity of rheumatoid arthritis in mouse models. Experimental cell research 2016, 1, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Liu, Y.; Mo, B.; Xue, Y.; Ye, C.; Jiang, Y.; Bi, X.; Liu, M.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Olsen, N.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, S. G. , Helios but not CD226, TIGIT and Foxp3 is a Potential Marker for CD4(+) Treg Cells in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Cellular physiology and biochemistry : international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology 2019, 5, 1178–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Fu, P.; Guo, Y.; Fu, B.; Guo, Y.; Huang, Q.; Huang, Z.; Li, J. , Increased TIGIT(+)PD-1(+)CXCR5(-)CD4(+)T cells are associated with disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Experimental and therapeutic medicine 2022, 4, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anaparti, V.; Tanner, S.; Zhang, C.; O'Neil, L.; Smolik, I.; Meng, X.; Marshall, A. J.; El-Gabalawy, H. , Increased frequency of TIGIT+ CD4 T Cell subset in autoantibody-positive first-degree relatives of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 932627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLane, L. M.; Abdel-Hakeem, M. S.; Wherry, E. J. , CD8 T Cell Exhaustion During Chronic Viral Infection and Cancer. Annual review of immunology 2019, 37, 457–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, O.; Giles, J. R.; McDonald, S.; Manne, S.; Ngiow, S. F.; Patel, K. P.; Werner, M. T.; Huang, A. C.; Alexander, K. A.; Wu, J. E.; Attanasio, J.; Yan, P.; George, S. M.; Bengsch, B.; Staupe, R. P.; Donahue, G.; Xu, W.; Amaravadi, R. K.; Xu, X.; Karakousis, G. C.; Mitchell, T. C.; Schuchter, L. M.; Kaye, J.; Berger, S. L.; Wherry, E. J. , TOX transcriptionally and epigenetically programs CD8(+) T cell exhaustion. Nature 2019, 7764, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, W.; Jerin, C.; Nishikawa, H. Transcriptional regulatory network for the establishment of CD8(+) T cell exhaustion. Experimental & molecular medicine 2021, 2, 202–209. [Google Scholar]

- Greisen, S. R.; Yan, Y.; Hansen, A. S.; Venø, M. T.; Nyengaard, J. R.; Moestrup, S. K.; Hvid, M.; Freeman, G. J.; Kjems, J.; Deleuran, B. , Extracellular Vesicles Transfer the Receptor Programmed Death-1 in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Frontiers in immunology 2017, 8, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schioppo, T.; Ubiali, T.; Ingegnoli, F.; Bollati, V.; Caporali, R. , The role of extracellular vesicles in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Clinical rheumatology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidler, J. D.; Hogan, K. A.; Agorrody, G.; Peclat, T. R.; Kashyap, S.; Kanamori, K. S.; Gomez, L. S.; Mazdeh, D. Z.; Warner, G. M.; Thompson, K. L.; Chini, C. C. S.; Chini, E. N. , The CD38 glycohydrolase and the NAD sink: implications for pathological conditions. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology 2022, 3, C521–c545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fang, K.; Yan, W.; Chang, X. , T-Cell Immune Imbalance in Rheumatoid Arthritis Is Associated with Alterations in NK Cells and NK-Like T Cells Expressing CD38. Journal of innate immunity 2022, 2, 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, V.; Marsh, R. A.; Zoref-Lorenz, A.; Owsley, E.; Chaturvedi, V.; Nguyen, T. C.; Goldman, J. R.; Henry, M. M.; Greenberg, J. N.; Ladisch, S.; Hermiston, M. L.; Jeng, M.; Naqvi, A.; Allen, C. E.; Wong, H. R.; Jordan, M. B. , T-cell activation profiles distinguish hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and early sepsis. Blood 2021, 17, 2337–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Singaraju, A.; Marks, K. E.; Shakib, L.; Dunlap, G.; Adejoorin, I.; Greisen, S. R.; Chen, L.; Tirpack, A. K.; Aude, C.; Fein, M. R.; Todd, D. J.; MacFarlane, L.; Goodman, S. M.; DiCarlo, E. F.; Massarotti, E. M.; Sparks, J. A.; Jonsson, A. H.; Brenner, M. B.; Postow, M. A.; Chan, K. K.; Bass, A. R.; Donlin, L. T.; Rao, D. A. , Clonally expanded CD38(hi) cytotoxic CD8 T cells define the T cell infiltrate in checkpoint inhibitor-associated arthritis. Science immunology 2023, 85, eadd1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. H.; Fan, J. H.; Jeng, W. J.; Chang, S. T.; Yang, C. K.; Teng, W.; Wu, T. H.; Hsieh, Y. C.; Chen, W. T.; Chen, Y. C.; Sheen, I. S.; Lin, Y. C.; Lin, C. Y. , Innate-like bystander-activated CD38(+) HLA-DR(+) CD8(+) T cells play a pathogenic role in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2022, 76, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Nguyen, T. H. O.; Wan, Y.; Sant, S.; Quiñones-Parra, S. M.; Crawford, J. C.; Eltahla, A. A.; Rizzetto, S.; Bull, R. A.; Qiu, C.; Koutsakos, M.; Clemens, E. B.; Loh, L.; Chen, T.; Liu, L.; Cao, P.; Ren, Y.; Kedzierski, L.; Kotsimbos, T.; McCaw, J. M.; La Gruta, N. L.; Turner, S. J.; Cheng, A. C.; Luciani, F.; Zhang, X.; Doherty, P. C.; Thomas, P. G.; Xu, J.; Kedzierska, K. , Clonally diverse CD38(+)HLA-DR(+)CD8(+) T cells persist during fatal H7N9 disease. Nature communications 2018, 1, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Wei, L.; Li, G.; Hua, M.; Sun, Y.; Wang, D.; Han, K.; Yan, Y.; Song, C.; Song, R.; Zhang, H.; Han, J.; Liu, J.; Kong, Y. , Persistent High Percentage of HLA-DR(+)CD38(high) CD8(+) T Cells Associated With Immune Disorder and Disease Severity of COVID-19. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 735125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobcakova, A.; Barnova, M.; Vysehradsky, R.; Petriskova, J.; Kocan, I.; Diamant, Z.; Jesenak, M. , Activated CD8(+)CD38(+) Cells Are Associated With Worse Clinical Outcome in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 861666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, P.; Chaturvedi, V.; Owsley, E.; Lane, A.; Heyenbruch, D.; Lutzko, C. M.; Leemhuis, T.; Grimley, M. S.; Nelson, A. S.; Davies, S. M.; Jordan, M. B.; Marsh, R. A. , CD38(bright)CD8(+) T Cells Associated with the Development of Acute GVHD Are Activated, Proliferating, and Cytotoxic Trafficking Cells. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2020, 26, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H.; Fujita, Y.; Asano, T.; Matsuoka, N.; Temmoku, J.; Sato, S.; Yashiro-Furuya, M.; Watanabe, H.; Migita, K. , T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-3 is associated with disease activity and progressive joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Medicine 2020, 44, e22892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadati, N.; Khodashahi, M.; Rezaieyazdi, Z.; Sahebari, M.; Saremi, Z.; Mohammadian Haftcheshmeh, S.; Rafatpanah, H.; Salehi, M. Serum Level of Soluble Lymphocyte-Activation Gene 3 Is Increased in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Iranian journal of immunology : IJI 2020, 4, 324–332. [Google Scholar]

- Greisen, S. R.; Rasmussen, T. K.; Stengaard-Pedersen, K.; Hetland, M. L.; Hørslev-Petersen, K.; Hvid, M.; Deleuran, B. , Increased soluble programmed death-1 (sPD-1) is associated with disease activity and radiographic progression in early rheumatoid arthritis. Scandinavian journal of rheumatology 2014, 2, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Jiang, L.; Nie, L.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L.; Du, Y.; Xue, J. , Soluble programmed death molecule 1 (sPD-1) as a predictor of interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis. BMC immunology 2021, 1, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Xu, L.; Cheng, Q.; Nie, L.; Zhang, S.; Du, Y.; Xue, J. , Increased serum soluble programmed death ligand 1(sPD-L1) is associated with the presence of interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis: A monocentric cross-sectional study. Respiratory medicine 2020, 166, 105948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasén, C.; Erlandsson, M. C.; Bossios, A.; Ekerljung, L.; Malmhäll, C.; Töyrä Silfverswärd, S.; Pullerits, R.; Lundbäck, B.; Bokarewa, M. I. , Smoking Is Associated With Low Levels of Soluble PD-L1 in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Frontiers in immunology 2018, 9, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommarito, D.; Hall, C.; Taams, L. S.; Corrigall, V. M. , Inflammatory cytokines compromise programmed cell death-1 (PD-1)-mediated T cell suppression in inflammatory arthritis through up-regulation of soluble PD-1. Clinical and experimental immunology 2017, 3, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Markers | Mean±SD (Number) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RA | Normal | ||

| CD4+CD279 | 8.129 ± 1.128 (48) | 3.93 ± 0.7035 (27) | 0.0104 |

| CD4+TIM3+ | 6.425 ± 0.8824 (48) | 4.015 ± 0.9389 (26) | 0.0862 |

| CD4+CTLA4+ | 0.1935 ± 0.03325 (46) | 0.08889 ± 0.0209 (27) | 0.0271 |

| CD4+LAG3+ | 1.513 ± 0.2435 (48) | 0.84 ± 0.1783 (25) | 0.0673 |

| CD4+CD127+ | 39.4 ± 3.769 (48) | 44.59 ± 5.149 (27) | 0.4159 |

| CD4+TIGIT+ | 25.91 ± 1.214 (48) | 20.13 ± 0.8377 (26) | 0.0016 |

| CD8+CD279+ | 7.94 ± 1.028 (47) | 4.896 ± 0.9672 (27) | 0.0525 |

| CD8+TIM3+ | 18.71 ± 1.905 (48) | 9.826 ± 1.19 (27) | 0.0015 |

| CD8+CTLA4+ | 0.266 ± 0.04565 (47) | 0.163 ± 0.03626 (27) | 0.1247 |

| CD8+LAG3+ | 0.9522 ± 0.1999 (46) | 0.1963 ± 0.05324 (27) | 0.0057 |

| CD8+CD127+ | 23.96 ± 2.343 (48) | 40.86 ± 4.19 (27) | 0.0003 |

| CD8+TIGIT+ | 48.08 ± 2.361 (48) | 25.81 ± 1.774 (27) | <0.0001 |

| CD8+CD160+ | 36.11 ± 2.629 (47) | 29.04 ± 1.988 (27) | 0.0661 |

| CD8+CD244+ | 4.063 ± 0.8992 (48) | 1.726 ± 0.4429 (27) | 0.065 |

| CD8+HLA-DR+ | 43.37 ± 3.425 (31) | 18.6 ± 1.909 (17) | <0.0001 |

| CD8+CD38+ | 29.03 ± 3.093 (31) | 22.97 ± 2.123 (17) | 0.1828 |

| CD3+CD160+ | 12.16 ± 1.294 (47) | 10.93 ± 1.137 (27) | 0.5247 |

| CD3+CD244+ | 16.58 ± 2.761 (48) | 7.477 ± 2.673 (26) | 0.0353 |

| CD3+CD279+ | 7.237 ± 0.998 (46) | 3.978 ± 0.7626 (27) | 0.0257 |

| CD3+TIGIT+ | 43.15 ± 2.507 (47) | 28 ± 2.888 (27) | 0.0003 |

| CD3+NKG2C+ | 16.14 ± 2.491 (46) | 9 ± 2.623 (26) | 0.0685 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).