1. Introduction

When a moving car beeps its horn, the driver and a bystander on the pavement hear the sound at different frequencies. The frequency shift resulting from the relative motion of the driver and the bystander is known as the Doppler effect [

1,

2] and is well understood in classical physics. For example, the frequency heard by the resting observer depends on the speed of the car relative to the pavement and the original frequency of the signal. Due to its simplicity, the Doppler effect has already found a wide range of applications, including the policing of speed limit violations by irresponsible drivers. The relativistic Doppler effect [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9] also accounts for differences in how observers experience space and time. Observers in different inertial reference frames which move at a relative speed close to the speed of light receive signals which differ not only in frequency and wavelength but also in amplitude.

According to Einstein’s principle of relativity [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], there is no privileged frame of reference. The same physical laws apply in all reference frames if these move with respect to each other at constant velocity. For example, wave packets of light with a well-defined direction of propagation move at the speed of light,

c, in any reference frame. Some authors might still debate whether this assumption is true or not [

17] but many experiments already verified the constancy of the speed of light with high accuracy [

18,

19]. Moreover, any physical theory that involves space and time requires a way of measuring both using clocks and meters. In the following, we assume that all clocks and meters are calibrated such that light travels at the same speed in all reference frames. We then have a fresh look at the relativistic Doppler effect [

5] with only a minimum of assumptions.

Instead of considering frequency space, in this paper we study the relativistic Doppler effect [

3,

5,

6,

7,

8] in position space [

20,

21,

22,

23]. As we shall see below, this space can accommodate spatial and time translational symmetries in a straightforward way. Although our results are consistent with the existing literature [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32], our approach paves the way for systematic studies of more complex scenarios, like the Unruh effect [

33,

34] and quantum electrodynamics in reference frames with time-varying accelerations without the need for approximations, such as the usual assumption of a flat spacetime [

35]. Moreover, the insights obtained here might have applications in relativistic quantum information [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. In the following, we review the relativistic Doppler effect before studying its implications for the quantised electromagnetic (EM) field in different inertial reference frames.

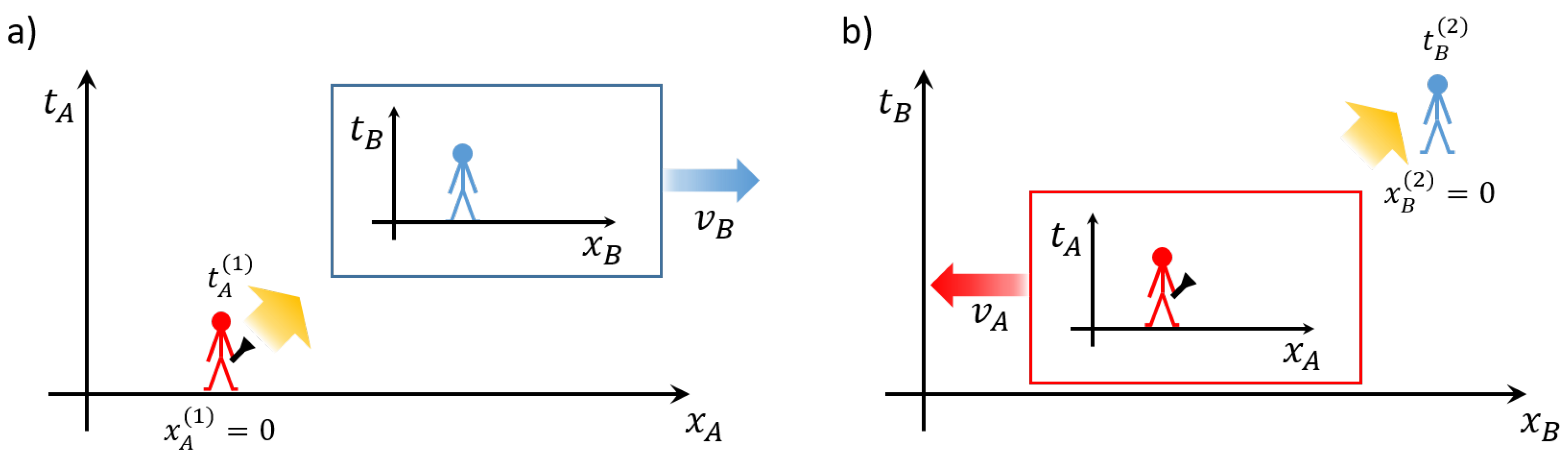

Suppose an observer—let us call her Alice (A)—is watching a wave packet of light with a well-defined direction of propagation

s and a well-defined polarisation

traveling along the

x axis. Then the electric field amplitudes

seen by Alice at positions

at times

equal

if the initial electric field amplitudes of the wave packet are given by

. Here

and

correspond to wave packets propagating in the direction of decreasing and increasing

respectively. Hence, if the physical properties of a wave packet seen by Alice are known at one instant in time, they are known at all times. The same applies to the electric field amplitudes

seen at

by a second observer—who we call Bob (B)—and

in analogy to Equation (

1). The electric field observables perceived by both Alice and Bob at any position and time are only characterised by the value of the parameters

with

. In the remainder of this paper, we shall use a shorthand notation and replace

by

.

The principle of relativity also suggests that the electric and magnetic field transformations from observer A to observer B and vice versa need to be formally the same. The only difference is that the relative speed of their reference frames changes from

to

. This suggests a linear dependence between electric field amplitudes

and

at the same point in the spacetime diagram since this transformation is the only transformation which remains formally the same when reversed. We therefore assume in the following that

where the coordinates

and

specify the same spacetime trajectory and

denotes a transformation constant. Analogously, we also know that

The principle of relativity also tells us that the transformation constants

and

relate to each other such that

since the direction of propagation

s of the wave packet is the same in both reference frames, but the relative speed of the frames changes sign. When combining Equations (

3)–(

5) we therefore find that

In the following, this is taken into account when we determine and .

Next we notice that the spatial and time translational symmetries of the EM field tell us that the above relations must hold for all spacetime coordinates. Hence the transformation factors

and

can only depend on the direction of propagation

s of the wave packet and on the relative speed

of Bob’s reference frame with respect to Alice’s reference frame and not on where and when electric and magnetic field amplitudes are measured. The above arguments thus reduce the question, how do local electric and magnetic field observables transform from one inertial frame to another, to the simpler question, namely, how do the field observables transform at a single point in the spacetime diagram? Unfortunately, the above equations are not enough to determine the transformation factor

in Equation (

3). An additional assumption is needed.

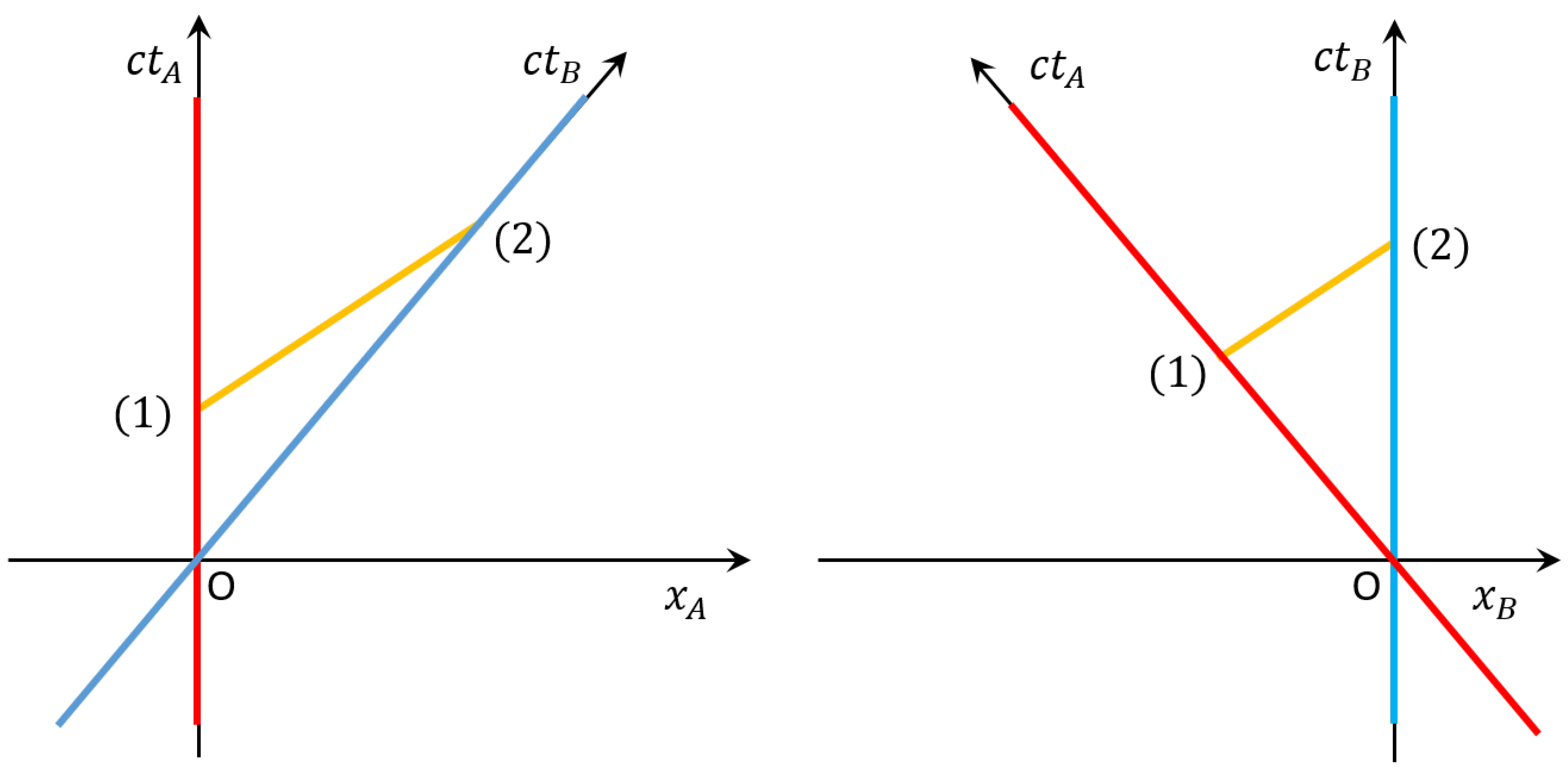

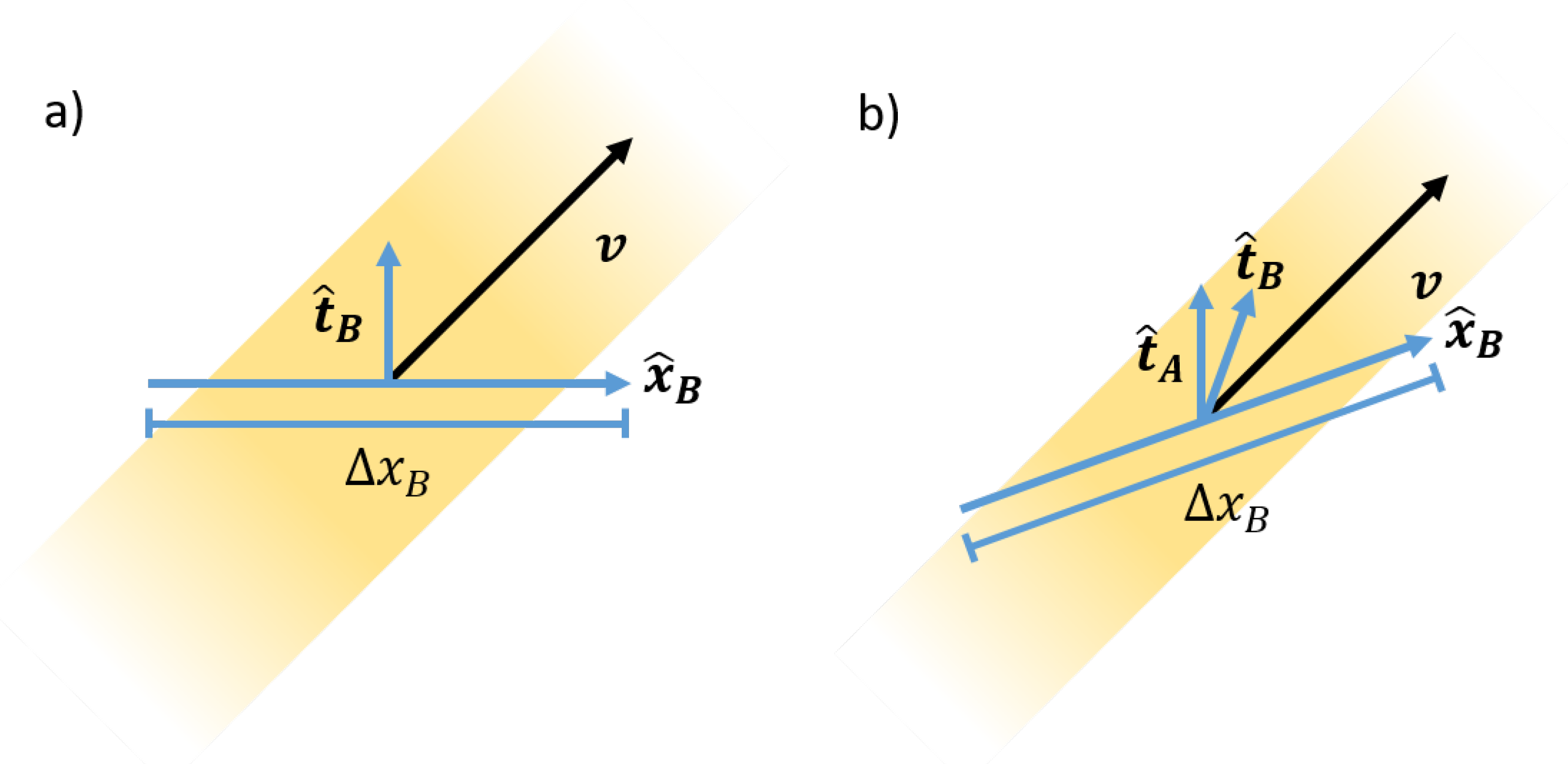

Our final assumption in the derivation of the relativistic Doppler effect is based on energy conservation. To implement this we consider a “box” that moves at the speed of light along the x axis in the reference frame of observer B. By integrating over the volume inside the “box” at a fixed time we can calculate the amount of energy it contains. As the “box” propagates at the speed of light, any light initially caught inside or outside of that “box” will remain here for all time, and the total energy that it encloses will be conserved. Nevertheless, as Alice and Bob experience space and time differently, the “box” observed by Bob will appear deformed to Alice and the energy of the field will be measured differently. For example, parts of the wave packet that occur simultaneously in the frame of observer A appear at different times in the reference frame of observer B. Taking this into account, we can finally identify the dependence of and on s and on . When applying Fourier transforms to local electric field amplitudes, we obtain the usual momentum changes of the relativistic Doppler effect.

As mentioned already above, the main purpose of this paper is to obtain a simple quantum picture of the relativistic Doppler effect. In the following we use a local photon approach and proceed as described in Refs. [

20,

21,

22] to quantise the EM field in different inertial reference frames. Given the principle of relativity, neither observer A nor observer B should be able to perform measurements on photonic wave packets which tell them about their relative speed. Taking this into account, we find that the local photon annihilation operators of Alice and Bob are the same when they refer to the same location in the spacetime diagram. However, the transformation of the annihilation operators of monochromatic photons is more complex. As we will see below, both observers Alice and Bob need to assign different quantum states

and

to wave packets of light, even when describing the same wave packet.

This paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the relativistic Doppler effect in classical physics. We first study how the coordinates

and

of two inertial observers A and B relate to each other when they correspond to the same point in the spacetime diagram. Afterwards, we derive the electric field transformation rates

and

in Equations (

1) and (

2) by imposing the above described conditions.

Section 3 reviews a local description of the quantised EM field [

21,

22] for light propagation in one dimension.

Section 4 combines this description with the results of

Section 2 to obtain a quantum picture of the relativistic Doppler effect and to identify the relationship between the quantum states

and

of a wave packet of light seen by observers A and B in different inertial frames. Finally, we summarise our findings in

Section 5.

3. The Quantised EM Field in the Stationary Frame

For a long time, it has been believed that photons do not have a wave function and that light cannot be localised [

45,

46,

47]. However, quantum physics should apply to all particles and photons should not be an exception. When a single-photon detector clicks, it measures the position of the arriving photon at that instant in time [

48,

49]. The origin of the problem was that many authors like to identify the wave function of the photon with its electric field amplitudes, but electric field amplitudes at different positions do not commute. The eigenstates of the electric field observable are therefore not local, although they can be made to appear local by altering the scalar product that is used to calculate the overlap of quantum state vectors [

20,

50].

An alternative way of establishing the wave function of a single photon is to separate its field from its carriers [

21,

22,

23]. The carriers of the quantised EM field in momentum space are non-local monochromatic waves. However, their Fourier transforms, so-called blips (which stands for bosons localised in position) provide a complete orthonormal set of basis states for the quantised EM field in position space. Like a point mass is a carrier for a gravitational field, blips are carriers of non-local electric and magnetic field amplitudes. Using the blip annihilation operators, it is for example possible to design locally-acting mirror Hamiltonians [

21] and to gain more insight into the Casimir effect [

51]. In this section we express the free, quantised, and 1-dimensional electric and magnetic field observables in terms of blips. As we shall see below, the EM field observables usually depend on contributions from blips at all points along the position axis. By applying a constraint to the blip dynamics, a relativistically form-invariant representation is derived. Later these expressions are used to derive a transformation between blips in Alice’s and Bob’s reference frames.

3.1. Local Photons

Let us first have a closer look at the modeling of the quantised EM field in Alice’s resting reference frame. Here blips are characterised by their position

at a given time

as well as their direction of propagation

s and their polarisation

. For boosts and translations along the

and

axes,

s and

are invariant. The parameter

denotes propagation in the direction of increasing and decreasing

respectively. We shall assume that

are two linear polarisations orthogonal to the

axis [

21,

22]. The creation operator

adds to the system a single blip located at a position

at a time

with direction of propagation

s and polarisation

. In the above † denotes complex conjugation and distinguishes

from the corresponding annihilation operator

which removes the same blip from the system.

For consistency with Maxwell’s equations, all blips must propagate at the speed of light. This constraint imposes the following condition on the blip operators: at some other time

, the time-evolved operator

must be equivalent to the blip creation operator at a position

. Hence

where

is the time evolution operator of the quantised EM field in Alice’s reference frame. As a consequence of this constraint, blips characterised by a single value of

are identical. From this point onwards we shall therefore denote blip creation and annihilation operators in Alice’s frame

and

respectively. Blips that are characterised by non-identical values of

,

s or

are distinguishable from one another, and therefore pairwise orthogonal. Hence, we can determine that

All creation operators commute with one another, as do the annihilation operators.

3.2. Field Observables in Position Representation

As shown in Refs. [

21,

22], an analogous description applies to vertically and to horizontally polarised photons. As in

Section 2 and for simplicity, we therefore restrict ourselves in the following to only one polarisation

. Let us say

. In this case, we do not need to consider the direction of Alice’s electric and magnetic field vectors. In the following,

and

represent the observables of the electric and magnetic field amplitudes respectively at position

at the initial time

and everywhere along the

trajectory. In the position representation, the field observables are expressed as an Hermitian, linear superposition of the blip creation and annihilation operators over Alice’s entire position axis and

In the expressions above, the contribution of each blip to Alice’s field observables are weighted by a non-local distribution

, which we shall refer to as the regularisation function. By taking into account that a single monochromatic photon has the positive energy

, the function

can be determined explicitly and can be shown to be equal to [

20,

22,

23]

As

is non-zero for all values of

, we view each blip as carrying non-local electric and magnetic fields. The energy observable in Alice’s frame is defined analogously to the classical energy. In particular, by substituting the real field observables into the energy density in Equation (

22), Alice’s energy observable becomes

As is usual in the Schrödinger picture, this observable describes the energy of the EM field seen by Alice at a fixed time , e.g., , and is conserved.

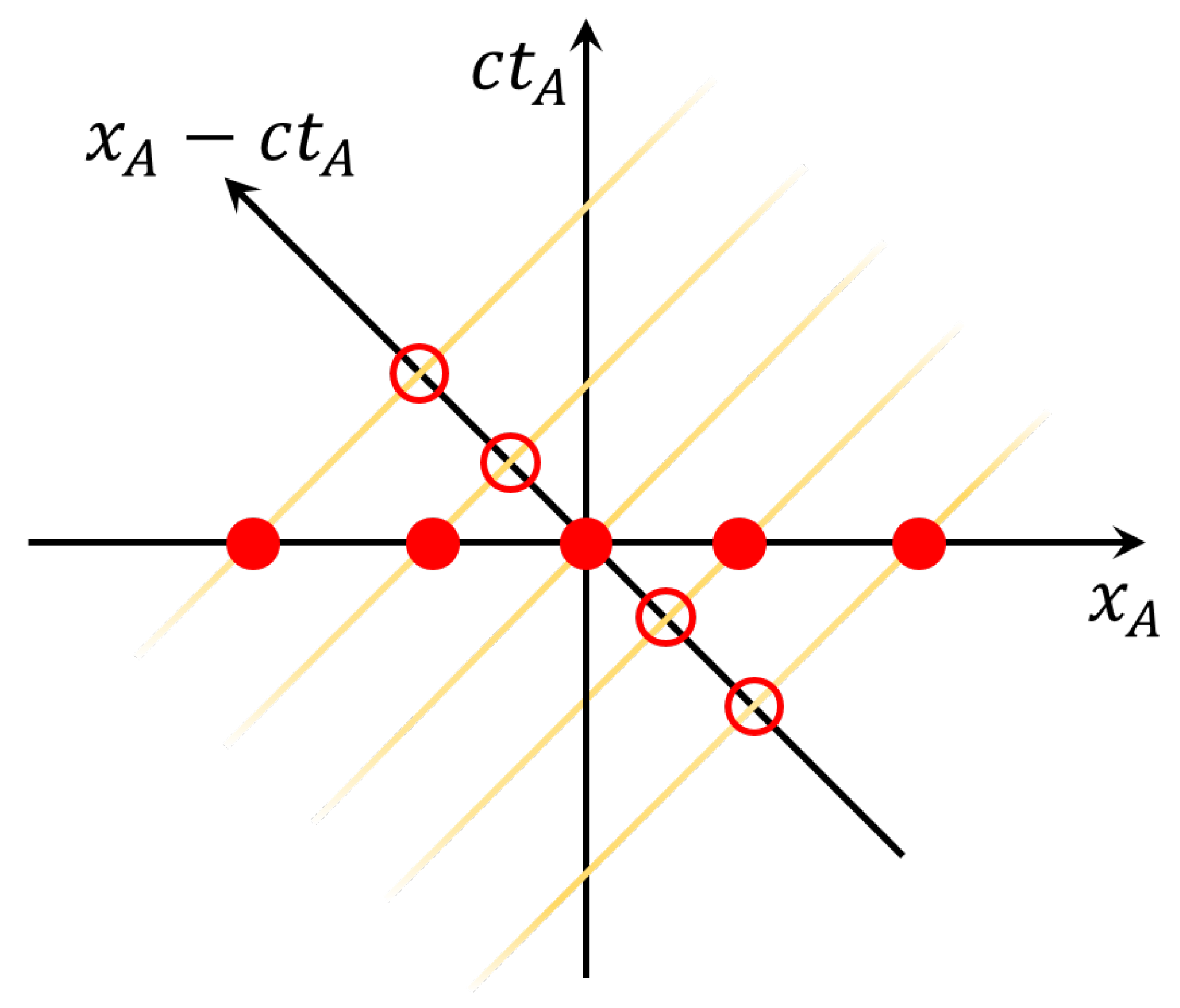

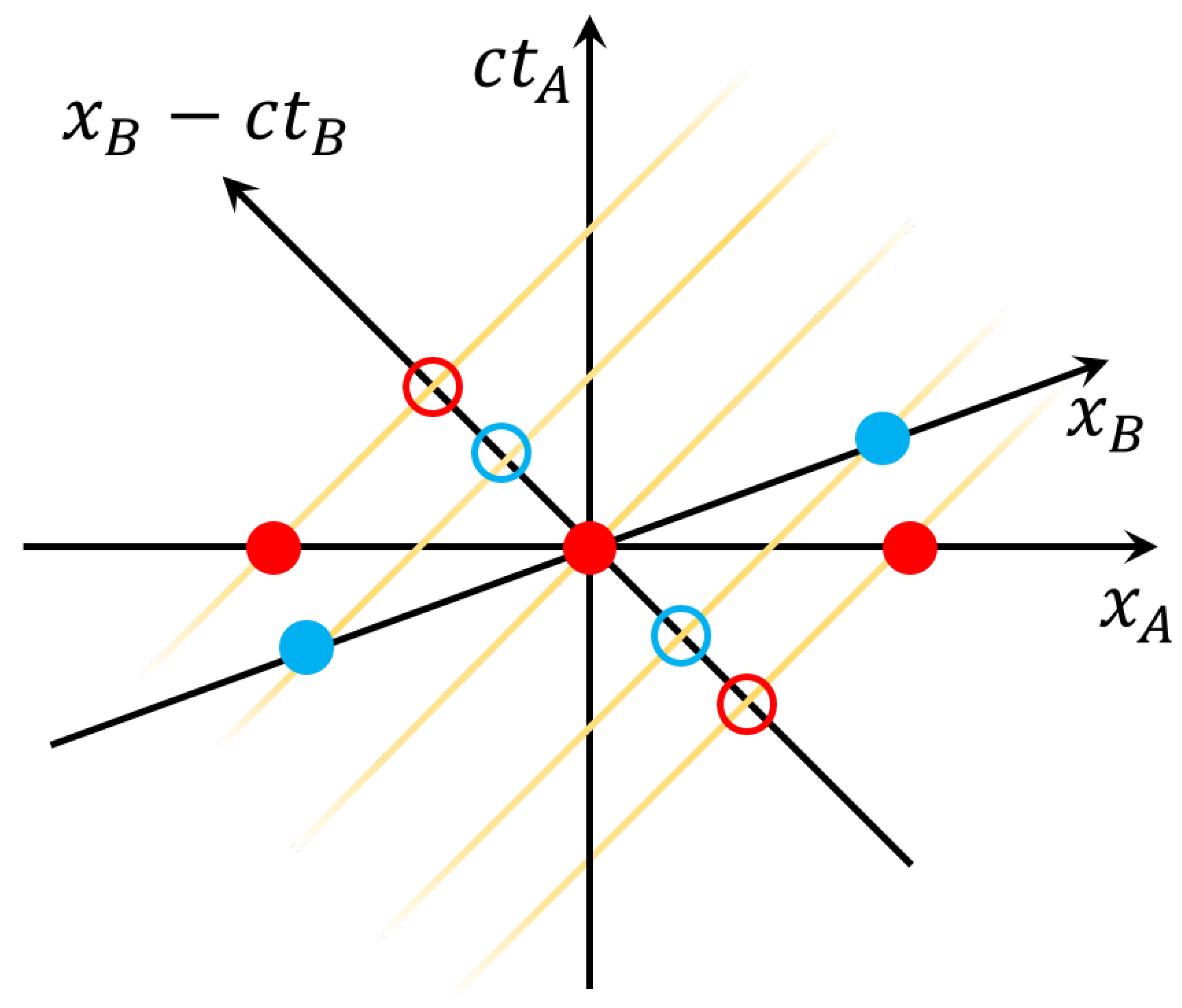

3.3. Non-Local Contributions to a Relativistic Observer

For Alice, who is at rest, the above non-locality of the electric and magnetic field observables—even when generated by a local source—can be viewed as the simultaneous contribution of blips from all points along her position axis, as discussed in Ref. [

22]. For a moving observer like Bob, however, events that take place along the

axis at a fixed time

are no longer simultaneous and do not occur at a single time

. For this reason, the superposition of blips over the position axis is not a relativistically reliable means of defining the field observables. Fortunately, the above representation of the field observables which characterises them by their world-line coordinate

and not by a single position

avoids this problem. Above we defined the field observables at a point

as non-local superpositions of blips along the

axis. This change in representation is illustrated in

Figure 4 for a field propagating to the right. In this diagram the field observable at the origin can be determined as a non-local superposition of blips along the

axis at a fixed

(marked in red). Alternatively they can be identically determined as a superposition of blips dispersed along the

axis. The advantage of this representation is that points along Alice’s light cones are also points along the light cones for any other observer, including those who, like Bob, are not at rest in Alice’s reference frame. Consequently, the same blips that contribute to Alice’s field observables also contribute to Bob’s field observables. In the next section we will show that this description of the field allows a comparison between blips in Bob’s frame and those in Alice’s frame.

5. Conclusions

This paper offers an alternative perspective on the relativistic Doppler effect which is usually referred to only in momentum space and discussed in terms of frequency, wavelength and amplitude changes of wave packets of light when measured in different inertial reference frames. In this paper, we study the relativistic Doppler effect in position space using the spacetime coordinates and of two inertial observers: Alice in the stationary frame and Bob in the frame moving with constant velocity with respect to Alice. This alternative approach allows us to accommodate time and spatial translational symmetries in a relatively straightforward way. In addition, we identify an invariant energy flux and take advantage of the principle of relativity.

For example, symmetry arguments and the principle of relativity are used to show that local electric field amplitudes seen by Alice and Bob only differ by a constant factor which we denote and respectively. Energy flux conservation can be used to calculate these factors as a function of the propagation direction s and the velocity of Bob’s reference frame with respect to Alice’s frame. For simplicity, we assume here that both observers are stationary in their respective coordinate systems and place them at the origin. When transforming our local description of the relativistic Doppler effect into momentum space, we recover the usual predictions which shows that our approach is consistent with the findings of other Authors.

In

Section 3 and

Section 4, we concentrate on the local description of the quantized EM field for light propagation in one dimension of Minkowski spacetime to obtain a quantum picture of the relativistic Doppler effect. Our aim here is to identify the relationship between the quantum states of a wave packet of light seen by Alice and Bob in different inertial frames. Our main result is the straightforward relationship between the annihilation operators

and

used by Alice and Bob for the description of local excitations—so-called blips—of the quantised EM field. When considering the same point in the spacetime diagram, i.e., when

and

depend on each other as stated in Equation (

16), both observers measure the same number of field excitations and the operators

and

. The relativistic Doppler effect is simply the result of Alice and Bob using different spacetime coordinates and experiencing space and time differently, while the speed of light is the same in all inertial reference frames [

4]. For example, electric field amplitudes which are simultaneous in Alice’s reference frame appear at different times

in Bob’s reference frame and vice versa.

The results of this paper might have applications in different areas of physics, including quantum communication [

36] and relativistic quantum information [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. In the current study, the concentration was on a well-expected result as a transformation between the stationary frame and moving with constant velocity frame in a classical and relativistic representation in order to explore it for blips as well. In the future, our approach can be used to study more complicated situations and systems like an accelerating frame.