Submitted:

03 January 2024

Posted:

05 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Remdesivir’ s role in treatment of COVID-19 in Hospitalized Patients

3.2. Remdesivir-Associated Hepatotoxicity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. Published 2020. Accessed 30 March 2020.

- Chen, N.; Zhou, M.; Dong, X.; et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020, 395, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hu, B.; Hu, C.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020, 323, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, W.J.; Ni, Z.Y.; Hu, Y.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, S.; Hu, N.; Lou, J.; et al. Characteristics of COVID-19 infection in Beijing. J Infect. 2020, 80, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, B.E.; Ong, S.W.X.; Kalimuddin, S.; et al. Epidemiologic Features and Clinical Course of Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore. JAMA. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Jin, X.; Hao, S.; et al. Analysis of Epidemiological and Clinical features in older patients with Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) out of Wuhan. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020, 395, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Chen, X.; Cai, Y.; et al. Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA internal medicine. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bhatraju, P.K.; Ghassemieh, B.J.; Nichols, M.; et al. Covid-19 in Critically Ill Patients in the Seattle Region - Case Series. N Engl J Med. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Oran, D.P.; Topol, E.J. The Proportion of SARS-CoV-2 Infections That Are Asymptomatic : A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2021, 174, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angulo, F.J.; Finelli, L.; Swerdlow, D.L. Estimation of US SARS-CoV-2 Infections, Symptomatic Infections, Hospitalizations, and Deaths Using Seroprevalence Surveys. JAMA Netw Open. 2021, 4, e2033706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Guo, H.; Zhou, P.; Shi, Z.L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021, 19, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yu, Y.; Xu, J.; et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Hu, X.; Cheng, W.; Yu, L.; Tu, W.J.; Liu, Q. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 18 patients with corona virus disease 2019 in intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Tu, W.J.; Cheng, W.; et al. Clinical Features and Short-term Outcomes of 102 Patients with Corona Virus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Marjot, T.; Webb, G.J.; Barritt ASt, et al. COVID-19 and liver disease: mechanistic and clinical perspectives. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021, 18, 348–364. [CrossRef]

- Jothimani, D.; Venugopal, R.; Abedin, M.F.; Kaliamoorthy, I.; Rela, M. COVID-19 and the liver. J Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, S.; Ashish, K.; Anikhindi, S.A.; et al. Effect of COVID-19 on pre-existing liver disease: What Hepatologist should know? J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hundt, M.A.; Deng, Y.; Ciarleglio, M.M.; Nathanson, M.H.; Lim, J.K. Abnormal Liver Tests in COVID-19: A Retrospective Observational Cohort Study of 1,827 Patients in a Major U.S. Hospital Network. Hepatology. 2020, 72, 1169–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, R.J.; Chalasani, N.; Bjornsson, E.S.; et al. Drug-induced liver injury. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalasani, N.; Fontana, R.J.; Bonkovsky, H.L.; et al. Causes, clinical features, and outcomes from a prospective study of drug-induced liver injury in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2008, 135, 1924–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwo, P.Y.; Cohen, S.M.; Lim, J.K. ACG Clinical Guideline: Evaluation of Abnormal Liver Chemistries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, Y.N. Remdesivir: First Approval. Drugs. 2020, 80, 1355–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, S.C.J.; Kebriaei, R.; Dresser, L.D. Remdesivir: Review of Pharmacology, Pre-clinical Data, and Emerging Clinical Experience for COVID-19. Pharmacotherapy. 2020, 40, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleissa, M.M.; Silverman, E.A.; Paredes Acosta, L.M.; Nutt, C.T.; Richterman, A.; Marty, F.M. New Perspectives on Antimicrobial Agents: Remdesivir Treatment for COVID-19. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Du, G.; et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020, 395, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinner, C.D.; Gottlieb, R.L.; Criner, G.J.; et al. Effect of Remdesivir vs Standard Care on Clinical Status at 11 Days in Patients With Moderate COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020, 324, 1048–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigel, J.H.; Tomashek, K.M.; Dodd, L.E.; et al. Remdesivir for the Treatment of Covid-19 - Final Report. N Engl J Med. 2020, 383, 1813–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium WHOST, Pan, H.; Peto, R.; et al. Repurposed Antiviral Drugs for Covid-19 - Interim WHO Solidarity Trial Results. N Engl J Med. 2021, 384, 497–511. [CrossRef]

- Ader, F.; Bouscambert-Duchamp, M.; Hites, M.; et al. Remdesivir plus standard of care versus standard of care alone for the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (DisCoVeRy): a phase 3, randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022, 22, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapadula, G.; Bernasconi, D.P.; Bellani, G.; et al. Remdesivir Use in Patients Requiring Mechanical Ventilation due to COVID-19. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garibaldi, B.T.; Wang, K.; Robinson, M.L.; et al. Comparison of Time to Clinical Improvement With vs Without Remdesivir Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2021, 4, e213071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consortium WHOST. Remdesivir and three other drugs for hospitalised patients with COVID-19: final results of the WHO Solidarity randomised trial and updated meta-analyses. Lancet. 2022, 399, 1941–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amstutz, A.; Speich, B.; Mentre, F.; et al. Effects of remdesivir in patients hospitalised with COVID-19: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2023, 11, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquini, Z.; Montalti, R.; Temperoni, C.; et al. Effectiveness of remdesivir in patients with COVID-19 under mechanical ventilation in an Italian ICU. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020, 75, 3359–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olender, S.A.; Perez, K.K.; Go, A.S.; et al. Remdesivir for Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Versus a Cohort Receiving Standard of Care. Clin Infect Dis. 2021, 73, e4166–e4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olender, S.A.; Walunas, T.L.; Martinez, E.; et al. Remdesivir Versus Standard-of-Care for Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 Infection: An Analysis of 28-Day Mortality. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021, 8, ofab278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garibaldi, B.T.; Wang, K.; Robinson, M.L.; et al. Real-World Effectiveness of Remdesivir in Adults Hospitalized With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Retrospective, Multicenter Comparative Effectiveness Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2022, 75, e516–e524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfield, T.; Bodilsen, J.; Brieghel, C.; et al. Improved Survival Among Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treated With Remdesivir and Dexamethasone. A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2021, 73, 2031–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunay, M.A.; McClain, S.L.; Holloway, R.L.; et al. Pre-Hospital Administration of Remdesivir During a Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Outbreak in a Skilled Nursing Facility. Clin Infect Dis. 2022, 74, 1476–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Vidal, C.; Alonso, R.; Camon, A.M.; et al. Impact of remdesivir according to the pre-admission symptom duration in patients with COVID-19. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021, 76, 3296–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metchurtchlishvili, R.; Chkhartishvili, N.; Abutidze, A.; et al. Effect of remdesivir on mortality and the need for mechanical ventilation among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: real-world data from a resource-limited country. Int J Infect Dis. 2023, 129, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalit, I.; Tiseo, G.; Ripa, M.; et al. Real-life experience with remdesivir for treatment of COVID-19 among older adults: a multicentre retrospective study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2023, 78, 1505–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therapeutics and COVID-19: living guideline, 13 J anuary 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023 (WHO/2019-nCoV/therapeutics/2023.1). Lic ence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Bhimraj, A.; Morgan, R.L.; Shumaker, A.H.; et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Treatment and Management of Patients with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2022. [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. National Institutes of Health. Available at https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/.

- Fix, O.K.; Hameed, B.; Fontana, R.J.; et al. AASLD Expert Panel Consensus Statement: COVID-19 Clinical Best Practice Advice for Hepatology and Liver Transplant Providers. 2022:1-12. https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/AASLD%20COVID-19%20Guidance%20Document%2010.06.2022F.pdf. Published 2022/10/06.

- Fan, Q.; Zhang, B.; Ma, J.; Zhang, S. Safety profile of the antiviral drug remdesivir: An update. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020, 130, 110532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Eades, W.; Yan, B. Remdesivir potently inhibits carboxylesterase-2 through covalent modifications: signifying strong drug-drug interactions. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2021, 35, 432–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Zou, L.; Jin, Q.; Hou, J.; Ge, G.; Yang, L. Human carboxylesterases: a comprehensive review. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2018, 8, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leegwater, E.; Strik, A.; Wilms, E.B.; et al. Drug-induced Liver Injury in a Patient With Coronavirus Disease 2019: Potential Interaction of Remdesivir With P-Glycoprotein Inhibitors. Clin Infect Dis. 2021, 72, 1256–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulangu, S.; Dodd, L.E.; Davey, R.T., Jr.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Ebola Virus Disease Therapeutics. N Engl J Med. 2019, 381, 2293–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grein, J.; Ohmagari, N.; Shin, D.; et al. Compassionate Use of Remdesivir for Patients with Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020, 382, 2327–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antinori, S.; Cossu, M.V.; Ridolfo, A.L.; et al. Compassionate remdesivir treatment of severe Covid-19 pneumonia in intensive care unit (ICU) and Non-ICU patients: Clinical outcome and differences in post-treatment hospitalisation status. Pharmacol Res. 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burwick, R.M.; Yawetz, S.; Stephenson, K.E.; et al. Compassionate Use of Remdesivir in Pregnant Women with Severe Covid-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zampino, R.; Mele, F.; Florio, L.L.; et al. Liver injury in remdesivir-treated COVID-19 patients. Hepatol Int. 2020, 14, 881–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montastruc, F.; Thuriot, S.; Durrieu, G. Hepatic Disorders With the Use of Remdesivir for Coronavirus 2019. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020, 18, 2835–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Laar, S.A.; de Boer, M.G.J.; Gombert-Handoko, K.B.; Guchelaar, H.J.; Zwaveling, J.; group LU-C-r. Liver and kidney function in patients with Covid-19 treated with remdesivir. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Goldman, J.D.; Lye, D.C.B.; Hui, D.S.; et al. Remdesivir for 5 or 10 Days in Patients with Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020, 383, 1827–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalil, A.C.; Patterson, T.F.; Mehta, A.K.; et al. Baricitinib plus Remdesivir for Hospitalized Adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021, 384, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danan, G.; Teschke, R. RUCAM in Drug and Herb Induced Liver Injury: The Update. Int J Mol Sci. 2015, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Stern, S.; Heil, E.L.; et al. Dexamethasone mitigates remdesivir-induced liver toxicity in human primary hepatocytes and COVID-19 patients. Hepatol Commun. 2023, 7, e0034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FakhriRavari, A.; Jin, S.; Kachouei, F.H.; Le, D.; Lopez, M. Systemic corticosteroids for management of COVID-19: Saving lives or causing harm? Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2021, 35, 20587384211063976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, D.B.; Budhathoki, P.; Syed, N.I.; Rawal, E.; Raut, S.; Khadka, S. Remdesivir: A potential game-changer or just a myth? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Life Sci. 2021, 264, 118663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, C.C.; Chen, C.H.; Wang, C.Y.; Chen, K.H.; Wang, Y.H.; Hsueh, P.R. Clinical efficacy and safety of remdesivir in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021, 76, 1962–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santenna, C.; Vidyasagar, K.; Amarneni, K.C.; et al. The safety, tolerability and mortality reduction efficacy of remdesivir; based on randomized clinical trials, observational and case studies reported safety outcomes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2021, 12, 20420986211042517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.L.; Chao, C.M.; Lai, C.C. The safety of remdesivir for COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2021, 93, 1910–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inhibitors and inducers of CYP enzymes and P-glycoprotein. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2017, 59, e56.

- Carothers, C.; Birrer, K.; Vo, M. Acetylcysteine for the Treatment of Suspected Remdesivir-Associated Acute Liver Failure in COVID-19: A Case Series. Pharmacotherapy. 2020, 40, 1166–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Design (size) | Patients | Intervention | Control | Hepatotoxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leegwater et al. [53] | Retrospective (N=1) | Hospitalized with severe COVID-19, critically ill | Remdesivir for 5 days plus chloroquine for 5 days | None | ↑liver enzymes (severe) |

| Zampino et al. [58] | Retrospective (N=5) | Hospitalized with severe COVID-19, critically ill | Remdesivir for up to 10 days; 4 patients received hydroxychloroquine | None | ↑liver enzymes in all 4 patients who also received hydroxychloroquine (moderate-severe) |

| Montastruc et al. [59] | Retrospective (N=387) | WHO’s VigiBase database of safety reports | Remdesivir up to 10 days | None | 30% ↑liver enzymes (severity not specified) |

| Van Laar et al. [60] | Retrospective (N=103) | Hospitalized with severe COVID-19, non-critically ill | Remdesivir for 5 days | None | 42% ↑liver enzymes (mild-moderate, except for 1 patient with severe) |

| Garibaldi et al. [34] | Retrospective (N=2,299; 570 propensity matched) | Hospitalized with severe COVID-19 | Remdesivir for 5 to 10 days | Standard of care | 10% ↑liver enzymes (severity not specified) |

| Grein et al. [55] | Prospective, descriptive (N=61) | Hospitalized with severe COVID-19, including critically ill | Remdesivir for 10 days | None | 23% ↑liver enzymes (mild-moderate) |

| Antinori et al. [56] | Prospective, descriptive (N=35) | Hospitalized with severe COVID-19, including critically ill | Remdesivir up to 10 days | None | 43% ↑liver enzymes (severity not specified) |

| Burwick et al. [57] | Prospective, descriptive (N=86) | Pregnant or postpartum women | Remdesivir up to 10 days | None | 9% ↑ALT (grade 3), 5% ↑AST (grade 3) |

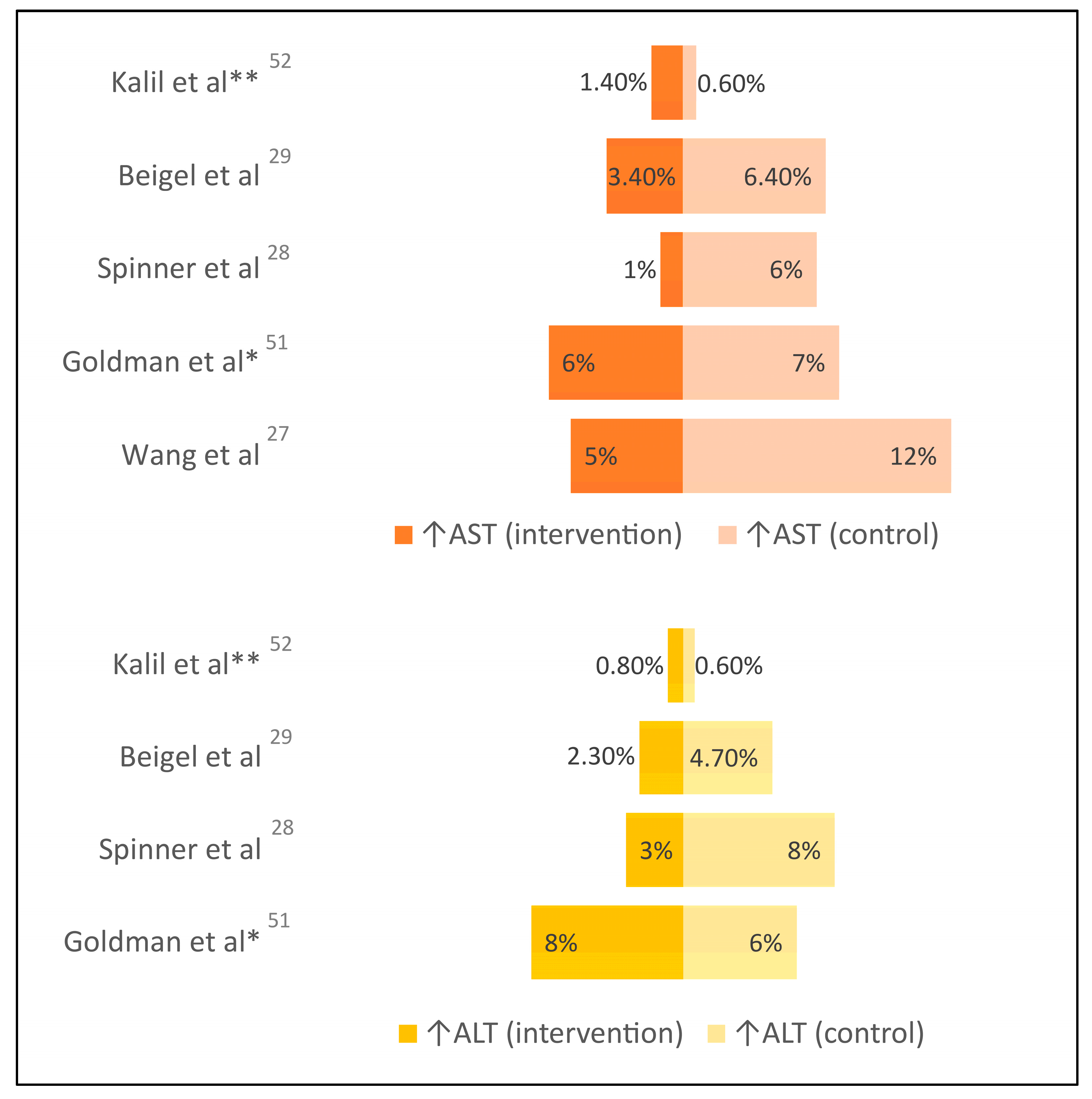

| Wang et al. [28] | RCT, double-blind (N=236) | Hospitalized with severe COVID-19; excluded cirrhosis or baseline grade 3 ↑liver enzymes | Remdesivir up to 10 days | Placebo | 10% vs 9% ↑liver enzymes (grade 3 or higher), 5% vs 12% ↑AST (grade 3 or higher) |

| Goldman et al. [61] (SIMPLE-1 Severe) | RCT, open-label (N=397) | Hospitalized with severe COVID-19, non-critically ill; excluded baseline grade 3 ↑liver enzymes | Remdesivir up to 10 days | Remdesivir up to 5 days | 8% vs 6% ↑ALT (grade 3 or higher), 6% vs 7% ↑AST (grade 3 or higher) |

| Spinner et al. [29] (SIMPLE-2 Moderate) | RCT, open-label (N=584) | Hospitalized with moderate COVID-19; excluded baseline grade 3 ↑liver enzymes | Remdesivir up to 10 days | Standard of care | 3% vs 8% ↑ALT (grade 3 or higher), 1% vs 6% ↑AST (grade 3 or higher) |

| Beigel et al. [30] (ACTT-1) | RCT, double-blind (N=1,062) | Hospitalized patients with mild, moderate, or severe COVID-19; excluded baseline grade 3 ↑liver enzymes | Remdesivir up to 10 days | Placebo | 2.3% vs 4.7% ↑ALT (grade 3 or higher), 3.4% vs 6.4% ↑AST (grade 3 or higher) |

| Kalil et al. [62] (ACTT-2) |

RCT, double-blind (N=1,033) | Hospitalized patients with mild, moderate, or severe COVID-19; excluded baseline grade 3 ↑liver enzymes | Remdesivir up to 10 days plus baricitinib up to 14 days | Remdesivir up to 10 days plus placebo | 0.8% vs 0.6% ↑ALT (grade 3 or higher), 1.4% vs 0.6% ↑AST (grade 3 or higher) |

| WHO Solidarity Interim Results [31] | RCT, open-label (N=5,475) | Hospitalized with mild, moderate, or severe COVID-19, including critically ill | Remdesivir up to 10 days | Standard of care | Safety data not reported |

| Ader et al. [32] (DisCoVeRy) | RCT, open-label (N=857) | Hospitalized with moderate or severe COVID-19, including critically ill | Remdesivir up to 10 days plus standard of care | Standard of care alone | 3% vs 1% ↑transaminases |

| WHO Solidarity Final Results [35] | RCT, open-label (N=8,275) | Hospitalized with mild, moderate, or severe COVID-19, including critically ill | Remdesivir up to 10 days | Standard of care | Safety data not reported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).