1. Introduction

La Fortaleza de Kuelap––a large pre-Hispanic settlement constructed atop a massive walled platform at 3000 m above sea level ––is among the most impressive structures ever built by an Indigenous Peruvian society (

Figure 1). Officially designated “La Fortaleza” (The Fortress) by Peru’s Ministry of Culture, it is one of several sites within the Kuelap complex, in the rainy tropical montane forests of the northeastern Andes. The monumental platform extends 550 m north-south along the crest of Cerro Barreta, with a maximum width of 150 m. Perimeter walls made of limestone blocks, weighing 300 to 2000 kg each, attain heights of 10-20 m. These walls enclose the mountain’s rocky summit and an additional 600,000 cubic meters of stone and clay fill that form a level surface for hundreds of stone structures. Late 19

th century reports exaggerated La Fortaleza’s volume, estimating it at a total of 7,221,116 cubic meters, and prompting comparisons to the Great Pyramid of Cheops and allusions to the Tower of Babel [

1] (p. 440-41).

Hyperbole aside, the monument strikes viewers as formidable. Atop the high platform surface, 5.11 hectares in size, a settlement of at least 420 circular habitations and five special purpose buildings fills almost the entire area [2-4]. La Fortaleza looms over a more extensive pre-Hispanic landscape today defined politically as the “Distrito de Tingo Anexo Kuelap,” where both ancient and contemporary hamlets, mortuary sites, and agricultural infrastructure spread across 450-500 hectares on a sloping plateau that juts out from Cerro Barreta and overlooks the Utcubamba River valley to the east.

Presently, Kuelap is included along with seven contemporaneous Utcubamba valley sites (

Figure 2, 1-8), on Peru’s Tentative List for UNESCO World Heritage, as emblematic of “Chachapoyas culture,” a categorical name handed down from the Inka, corresponding to societies sharing a distinctive set of cultural attributes in the northeastern Andes. It is considered of outstanding universal value because it represents a most astonishing and singular achievement of a pre-Hispanic society. Further, La Fortaleza’s many stone circular dwellings unite design elements that characterize the architectural style for which the region is widely known [

5]. As a major tourist destination in the Amazonas region, Kuelap is widely marketed as a “second Machu Picchu.” In 2017, the country’s first cable car was installed to afford rapid access to the site from the village of Nuevo Tingo [

6], and visits boomed. Yet, as criticism mounted over the poor conditions of La Fortaleza, its main entrance or Acceso (Entryway) 1 in particular, visitor numbers fell by 2019, before the temporary closure brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. The downward trend raised questions about the long-term sustainability of increasing tourism at the site.

The name “Chachapoyas” refers to autonomous societies living in Peru’s northeastern Andes, first conquered by the Inka, then by the Spanish. The name persisted to conveniently gloss-over differences between ethnic and kin groups in the region. Under Spanish hegemony, Chachapoyas came to fit European notions of geographic places with perceived territorial boundaries.

Comentarios Reales, a popular chronicle written by “El Inca” Garcilaso de la Vega [

7], reified the understanding of Chachapoyas as a place by describing its area as 50 leagues long (north-south) and 20 leagues wide (300,000 km

2) based upon text provided by mestizo Jesuit Blas Valera, who grew up in the colonial town from birth in 1544 until the age of 15. Both the Inka and Spanish enlarged the province by annexing adjacent territories during their rule. By contemporary definitions, “Chachapoyas” can be considered a colonialist label. Despite a lack of sociopolitical unification, local societies are referred to as “Chachapoya” (the ‘s’ is dropped when referring to social groups, in order to de-Hispanicize the term). In any case, “Chachapoyas” is an eponym conveniently used to characterize societies deemed similar for the purposes of reference and/or imperial administration [

8,

9,

10]. Unfortunately, we have little reliable ethnographic or ethnohistorical information to aid understanding of these groups, who experienced a rapid and nearly complete demographic collapse after their conquest [

11,

12], caused by European diseases, conscription by Inkas and Spaniards to fight wars, internecine violence, forced labor to bear cargo for El Dorado expeditions, and abuse by Spaniards who expected a continuing stream of tribute income despite shrinking numbers of Indigenous tributaries. Heightened violence, disease epidemics, and various forms of abuse typify sociopolitical processes at what Ferguson and Whitehead call “the violent edge of empire” [

13]. This precipitous population decline allowed the tropical montane forests to quickly reclaim the land and conceal an ancient cultural landscape.

Today, seemingly invulnerable La Fortaleza faces a crisis. Between April 10th and 11th, 2022, during an anomalously high phase of the region’s heavy rainy season, a series of collapses brought down a large segment of its southern perimeter wall. Yet this was not an isolated event: our project has documented a long history of collapses, from a massive pre-Hispanic one involving the southeastern corner of the platform, to a series of other collapses documented in the last 100 years.

On March 31

st 2013, a substantial, yet poorly documented collapse north of Acceso 1 (

Figure 4), affected the eastern perimeter wall. It led to a restoration project; however, facing unexpected obstacles, the project was cancelled, leaving behind a massive, unfilled excavation and many mounds of exhumed construction fill that remain piled within the site to this day. According to reports from the Ministry of Culture, conservation conditions at La Fortaleza progressively worsened thereafter. Then, two earthquakes struck the region, on November 28

th, 2021 (7.5 magnitude) and February 3

rd, 2022 (6.5 magnitude). Mounting evidence of structural instability prompted authorities to declare La Fortaleza in emergency on February 12

th. Two months later, a large segment of the monument’s southeastern perimeter wall collapsed after historically high precipitations, hastening the current crisis. Immediately, archaeologists and conservation practitioners advised that the structural deterioration and the threat of additional collapses required a pause in tourism inside La Fortaleza. Because it is the primary tourist attraction in the Amazonas region of Peru, this unavoidable decision resulted in substantial financial losses for the local and regional service economies.

With the goals of stabilizing La Fortaleza and resuming tourism, the Ministry of Culture has implemented emergency conservation measures, with three objectives: 1) immediately preventing additional collapses and mitigating ongoing structural deterioration, 2) evaluating water retention and drainage, and 3) identifying the proximate causes of structural failures. In this paper, our goal is to support these conservation efforts by systematically reviewing and analyzing existing and new datasets to identify the causes of La Fortaleza’s rapid deterioration. Specifically, we evaluate the hypothesis that the root cause of the collapses is the increasing moisture within the fill enclosed by its perimeter walls. We present a hydrological analysis of the monument’s surface, based on a Digital Terrain Model (DTM) generated from airborne LiDAR data. Integrated with the results of electrical resistivity surveys that identify pockets of high humidity within the platform’s subsurface construction fill, we use the hydrological analysis to generate a risk map. We propose that this product, and our several other observations on the conservation conditions of La Fortaleza, be used to guide short- and long-term mitigation solutions to improve its structural integrity and permit its sustainable public use. Our combined analyses demonstrate the potentials of integrating data acquired using near-surface geophysics and close-range remote sensing technologies to generate a more complete and nuanced understanding of risks that threaten La Fortaleza. Our results suggest that the current risks are the result not only of natural conditions and processes, but also well-intentioned yet ultimately damaging conservation interventions, and initiatives to reduce or eliminate the forest vegetation from the monument's surface.

In the remainder of this introduction, we summarize relevant environmental, archaeological, and historical literature, and provide additional cultural contexts with which to consider the analyses, interpretations, and conclusions to follow.

1.1. The land and the climate

The tropical Andean cloud forests and steep mountain terrain surrounding Kuelap are spectacular––these are lands of deep canyons and high mountaintops, with misty montane forest covering rugged slopes, where not deforested. While it may seem benign and majestic on sunny days, it is also subject to furious rain- and hailstorms, which can arrive with little notice––and with greater intensity during the rainy season between October and May. The effects of these storms are most violent (and dangerous) above 2,500 m above sea level, where they virtually liquify valley landscapes, swell rivers into torrents, produce flash floods, and trigger landslides. These not only impede travel but have wiped out homes and entire villages. Archaeologists refer to Chachapoyas montane forests as “Ceja de Selva” (literally “eyebrow of the Tropical Forest”), or the highland rim of Amazon rain forest. It is not possible to characterize the formation of cloud forest by describing the orogeny, atmospheric conditions, and biological systems in isolation. Its atmospheric and biological variables are interdependent, and the forest is the independent variable without which the affected area would dry-up.

La Fortaleza, our study area, is situated at UTM coordinates 18S 176537 E 9289675 N, and an elevation of 3018 m. Cerro Barreta, where Kuelap lies, is part of the Calla Calla Mountain range, which trends north and south above the Marañon River to the west, and above the Utcubamba River to the east as it descends 120 linear kilometers north-northeast to join the Marañon in the Huancabamba Depression lowlands (

Figure 2). The geology of the Calla Calla range consists primarily of limestone, with karst features such as sinkholes and deep caverns. Politically, contemporary Kuelap lies in the Province of Luya near the southern boundary of Amazonas Department. Below we briefly offer some broader geographical information to place Kuelap into environmental and climatic contexts.

Langlois [

14] (Figure 1, p. 221) was the first scholar to distinguish pre-Hispanic northern and southern regions of the Chachapoya culture area as delineated by Garcilaso de la Vega. Kuelap lies within the northern region, which begins in the Utcubamba headwaters and encompass the Utcubamba and Sonche river valleys. The divide’s location at latitude 6°58’ S approximates the boundary between Amazonas and La Libertad regions, as well as orogenic and geological transitions. It also coincides with a cultural boundary separating Chachapoyas architectural traditions in the north, from more varied traditions in the south, many of which do not resemble those of the Utcubamba valley. Montane and premontane forested regions on the adjacent eastern Andean slopes have harbored sociopolitical groups settled within San Martín region.

Steep topography and variable weather patterns produce a diverse mosaic of ecological zones, with a minimum of 84 of the 103 life zones of the world’s Holdridge life zone biogeographic classification system [

15]. Major life zones include high-altitude grasslands (paramo/jalca), humid, and perhumid tropical montane forests, and arid forests at the lowest altitudes. Broken landscapes often thwart connectivity, and high levels of species endemism render the region a biodiversity hotspot.

Abundant precipitation surrounding northern Chachapoyas results from orogenic lift as easterly winds cross the Amazon basin and encounter the eastern Andean slopes. Condensation above 2500 masl creates an altitudinal belt of fog where forest vegetation intercepts moisture and, because transpiration exceeds evaporation, the cloud forest formation is sustained [

16]. The same dense clouds flow into the Utcubamba and Marañón river valleys to envelope Kuelap and mountaintops farther south. Deforestation eliminates the key variable of transpiration, and cloud forests deteriorate as they dry up. Such conditions result in drought and endangerment of forest species, unable to adapt quickly and keep pace with biogeographical change, especially at tree lines [

17].

Mean annual temperatures at these elevations are estimated from 7 to 15 °C. Annual rainfall numbers from the few meteorological stations in the region represent only vertical rainfall, not moisture resulting from the transpiration of local vegetation, which is largely responsible for the low clouds. As a result, the stations underestimate area humidity and atmospheric saturation. According to geographer K. Young [

18,

19], a reasonable estimate may be 2500 – 3000 mm yearly, at least between extreme events. Rainy season storms bring lightning and frequently cause landslides that have historically taken many lives, such as in the destruction of the nearby town of Tingo in 1993. Given these weather patterns, it is not surprising that La Fortaleza appears timeworn.

Evidence that the Utcubamba valley was deforested and cultivated on terraced slopes has been gathered and analyzed by Plekhov [

20] and colleagues, but the extent of such landscape transformation remains unknown. A longitudinal analysis based upon ground-level fieldwork with subsurface sampling of walled and unwalled terraces allowed an estimate of terrace construction and use beginning by AD 1, which coincides with a proliferation of Early Intermediate Period occupations throughout the region [

9,

21]. Records of climate and environmental change analyzed by climatologists and paleoecologists provide indications of substantial regional climate change over time. Oscillations have been registered through analyses of speleothems that show signals of more humid conditions during the peak of the Medieval Climate Anomaly around AD 950, and drier conditions become the pattern around AD 1300 and the beginning of the Little Ice Age [

22]. Approximate correlations of paleoenvironmental change detected in sediment cores from places such as the Lake of Condors [

23] with inadequately-documented trends in cultural developments warrant future investigation. Short and long-term wet and dry periods likely provoked changes in patterns of settlement and mobility [

24], as changes in moisture levels impacted natural resource distribution and locations where agriculture was possible.

The first Spanish chronicler to arrive in the Utcubamba valley with the aim of providing a first-hand description was Carmelite Friar Antonio Vasquez de Espinoza, who visited the area in 1615 [

25]. His work includes references to Corregimientos and Curates, some of which he visited. However, he arrived too late to provide substantial ethnographic information as Indigenous social institutions had crumbled amidst continued depopulation. He wrote, “the country contains few Indians at present, many having died off and others gone over to the hostile region" (i.e., taken refuge in the free lands to the east in the Amazonian forests). He also observes that, “there are very rich gold mines… but for lack of labor, these are not working” (p. 404). Vasquez de Espinosa often comments that the province “is heavily wooded” (pp. 403, 405). Plekhov’s analysis of pre-Hispanic terraforming and cultivation in the once-densely-populated Utcubamba valley, combined with Vazquez de Espinosa’s description of the same landscape ca. 84 years after the Spanish incursion, illustrates the rapid tempo of population collapse and regrowth of montane forests. Regional population numbers did not rebound until the 19

th century, by which time most of the depopulated Utcubamba valley would have become densely (re)forested.

Today, climate change continues to impact both landscapes and livelihoods. Weather events are expected to intensify. Climatological studies document increased temperature and rainfall in this part of Peru over the past 50 years, with trends varying seasonally and by metric [

26]. At La Fortaleza, a study conducted as part of our broader research project documents an increase in precipitation over the period 1981-2022, and in particular, a historically high phase at the time of the 2022 collapse [

27]. Interdisciplinary studies are documenting the upward migration of the cloud belt and considering its consequences [

28,

29]. Highland farmers are already struggling to schedule their planting and harvest seasons as weather patterns become less predictable.

1.2. Kuelap: First encounters

If there is such a thing as a “lost city,” Kuelap was never one of them. Upon arrival to the region in 1535, Spanish soldiers led by Captain Alonzo de Alvarado explored the countryside. From 1535 to 1540, literature including calendrical dates for particular events often contradict one another, although two documents, both probably written by Juan de Alvarado ca. 1555 and reproduced in works by Cieza de Leon [

30] and Jimenez de la Espada [

31], provide a sketch of significant events. By late 1536, a Spanish sortie departed north to “pacify” other groups and claim more territory for Spain. Marching northward along the Calla Calla mountain range above the Utcubamba River, the soldiers skirmished with groups that would have included the Chillao (later called the Luya-Chillao) whose ancestors were the most likely builders of Kuelap [

3] (p. 141). The names “La Fortaleza” and “Kuelap” do not appear in these documents. While the name “Cuelap” appears in many colonial period documents, there is no written evidence that early Spanish colonial chroniclers knew of La Fortaleza. For this reason, Adolph Bandelier, the first professional archaeologist to visit the site and submit a report in 1893, believed it to have been abandoned before the first such invaders arrived in 1535 [

32] (pp. 19-20). Early historical documents refer to Kuelap as an

estancia or

hacienda (both terms meaning “ranch”), and this is likely how the colonists understood the name. At the regional level, La Fortaleza evidently receded into a dim memory, but it was never “lost” and likely remained known to local people.

In 1538, the Spaniards united at their first colony at La Xalca (La Jalca) and formally divided the former Inka Province of Chachapoyas into repartimientos (rights to a specified share of Indigenous labor and land). Alonso de Alvarado claimed Kuelap along with other large repartimientos for himself [

33,

34] (Alvarez [1572] Document No. 6 in [

33]; Biblioteca Nacional de Lima [1577], Appendix 14 in [

35]). Judging La Xalca unsuitable, the Spaniards quickly relocated to Levanto, a centrally-located place controlled by Indigenous allies hypothetically belonging to a Chacha ayllu who controlled the locality. That Alvarado took Kuelap for himself indicates that he knew that the place was inhabited by a large Indigenous population and was highly regarded as productive.

Although there is no mention of Kuelap in Colonial period chronicles, publications based on research in regional and national archives show Kuelap listed as a

repartimiento until the 1570s’ implementation of Viceroy Toledo’s program of

Reducciones (forced relocations) when its residents were ostensibly relocated to Santo Tomás de Quillay. If the settlement of Kuelap was ever fully abandoned, it was soon repopulated. By the end of the 16

th century legal records of civil affairs document the buying, selling, and transferal of properties such as Kuelap among Spanish colonists. Transactions identify Kuelap variously as “la Estancia, la Hacienda, el Fundo, and Los Corrales” de Kuelap (all terms signify “ranch”) and must refer to today’s Anexo Kuelap, where slopes east of the monument are well-suited for pasturing livestock and farming. By means of archaeological investigations, evidence of a single, remarkable 16

th century violent event was uncovered at the southern end of La Fortaleza, and the finds have been analyzed and published. Toyne and Narvaez examined artifacts and skeletal remains of 106 individuals, nearly all young and middle-aged males showing unequivocal signs of death by execution [

36,

37]. All were victims of a mass-killing event that a few colonial period artifacts indicate took place not long after the Spanish intrusion. The authors suggest that the bloody event occurred at the time of Viceroy Toledo’s

reduccion program ca. 1570. However, the calendar date remains uncertain. During this time, viceregal envoys were likely moving through the region, taking a census, and enforcing the new program. Bandelier’s suggestion that La Fortaleza was abandoned at this time might still be correct if we postulate that the victims of the killing were seeking refuge within.

In 1843, more than two and a half centuries after the invasion, civil magistrate Juan Crisóstomo Nieto [

38] set out to resolve a conflict at the “Estancia de Kuelap” but returned to write about the spectacular ruins he had observed on the site. After his eventful visit, he recorded the Case number as Exp. 4347 now referring to “las tierras de la Fortaleza de Kuelap” [

39]. Guided by Don Gregorio Rodriguez, who was likely the

hacienda caretaker, Nieto wandered through La Fortaleza, estimated the monument’s dimensions, and recorded his observations. His report was published without much fanfare in news media in Perú and abroad and later reproduced by Modesto Basadre of Sociedad Geográfica de Lima, who republished Nieto’s original report with exaggerated editorial pronouncements declaring that La Fortaleza was nearly three times larger than that of Cheops, the Great Pyramid of Egypt [

1]. Traveling explorers including Raimondi, Werthemann, Middendorf, and others visited the monument during subsequent decades. These travelers reached “Kuelap,” the

hacienda that was a cluster of small houses beneath La Fortaleza [

40]. A few years later, Bandelier [

32] would learn that the

hacienda settlement was named Lirio, which likely corresponds to the present-day village and archaeological sector of the same name (

Figure 5).

At this juncture, we might ask how a monument that Basadre compared to Cheops could remain obscure for three hundred years? As previously stated, Kuelap was never “lost” in any non-colonialist sense. As noted above, Bandelier offered his opinion that La Fortaleza was abandoned prior to the Spanish incursion. He was referring to the monument and not to the hacienda lying less than one kilometer to the east [

32]. Bandelier’s interpretation finds support in the lack of references to the monument by the Spanish colonists. Furthermore, the monument was so concealed by vegetation that, from the hacienda, Middendorf did not see it until La Fortaleza was pointed out to him. Then he recognized that the base of the walls lay hidden behind the forest (

Figure 3), and the tops of the walls were hidden by overhanging trees [

41] (p. 216). The descriptions in much of this literature include observations that

hacienda residents regarded La Fortaleza as a dark and fearful place where human bones and other remains, fallen from fractured interments within the walls, lay strewn on the ground [

32,

38]. Residents of the

hacienda below referred to La Fortaleza by various names including

Muralla, Malca, Muro, and others [

32,

42]. Middendorf observed that villagers feared that La Fortaleza was haunted by ghosts. During his visit to Kuelap and La Fortaleza several years later, Alayza’s took special notice of La Fortaleza’s dense cover of thick vegetation [

43]. His final report concluded with his personal, more visceral, opinion:

The compact forest in and around the upper part of the building gives it such a wild, strange, and sinister appearance that not without a certain fear can the traveler go into it. And this dread increases as the absolute lack of life, not even of a bird or reptile, gives animation to the somber building [

43] (our translation).

Neither La Fortaleza’s “ghosts” nor its thick cloak of dense forest adequately accounts for the monument’s centuries of obscurity, although these factors must have contributed. It remains uncertain whether local villagers understood the interest that La Fortaleza might hold to more worldly “outsiders.” Nieto’s first written documentation of the monument in 1843 likely precipitated an increase in looting over subsequent decades. Late 19

th and early 20

th century scholars who visited Kuelap noted active looting at the site and some, like Alayza [

43](p. 157), Nieto, and Don Gregorio Rodriguez, carried away human remains and grave goods as souvenirs.

Since the colonists first settled, internecine and regional conflicts among Indigenous groups swirled around the settlement for many years preceding 1570 and after Toledo’s

reducciones as well. Texts from the earliest town council meetings (called Cabildos) include calls for help from coastal authorities. Residents expressed worries that Alonso de Alvarado and his military presence were needed, but he was usually engaged elsewhere fighting in wars between the Spaniards. By 1541, Alvarado had settled in Huamanga far to the south and did not return. During the mid-1540s, colonists became increasingly alarmed at the inexorable shrinking of the Indigenous population. Considering the chaos during the first colonial decades, it should not be surprising that we lack useful, first-hand descriptions of Chachapoya cultural traditions. Blas Valera was born almost 10 years after the Spanish arrival, and his cursory descriptions conveyed by Garcilazo were based on local oral histories and memories that Valera put to paper at an advanced age [

8].

1.3. The Chachapoya: A brief history and archaeology

Scholarly understanding of the Indigenous history of the Utcubamba valley region relies on both documentary sources and archaeology. Unfortunately, the only eye-witnesses to events during the prolonged efforts to subjugate the Indigenous peoples under rapid sociopolitical disintegration and population decline were Spanish soldiers and their families, and a small number of landless citizens who rarely left the safety of their homes at Levanto. The most influential chronicle with text directly related to Indigenous Chachapoya history and culture is still the combined work of “El Inca” Garcilaso de la Vega [

7] and Blas Valera. However, this account misleadingly characterizes the Chachapoya as a unified nation prior to Inka conquest. Documentary information published by Espinoza [

33] and many others contradicts the Valera-Garcilazo narrative on several points [

8]. Some scholars have described Chachapoya societies as joined in a confederacy that occasionally united against external threats. However, there is no evidence that named social groups ever joined forces on any significant scale. Furthermore, the Valera-Garcilazo account describes Inka Topa Yupanqui’s northward penetration of the region along the easternmost cordillera as a series of isolated battles fought at every major population center between Pias in the south and Levanto. Evidently, Topa Yupanqui’s invasion battled at least five independent

ayllus during his northward march. The testimonies reported from mid-15

th century documents published by Espinoza describe autonomous sociopolitical groups that may have had egalitarian elements.

Some archaeologists presently argue in support of a pre-Inka Chachapoyas “state” centered at Kuelap [

36,

44]. Lacking a contemporary theoretical framework along with peer-reviewed data to consider, especially published primary data from Kuelap, it is more likely that Chachapoyas specialists will continue to regard the region and its pre-Hispanic peoples as belonging to numerous, autonomous sociopolitical groups prior to successive Inka and European invasions [

5,

8,

33,

35]

Today, genetic evidence suggests long-term autochthony in local Indigenous populations, to the extent that their genome can be distinguished from those of highlanders and lowlanders, but with significant mixing attributable to thousands of years of families and communities entering the region. Late pre-Hispanic incursions, chaotic conquests, and immigration in more recent centuries have also been identified during rigorous genetic analyses of local and non-local populations [45-47]. Non-Quechua family and place names preserve elements of a substrate of pre-Inka local language(s) that linguists have been recovering and reconstructing, and using to hypothesize affiliations with other language groups and families [48-52].

Salient evidence of the region’s sociopolitical history before the Inka invasion consists of hundreds of archaeological sites large and small, typically located on hilltops and high ridges. These settlements consist of mostly circular stone houses with average diameters between 6 and 8 meters, clustered on terraces leveled to create space for daily activities and social interaction. The numbers of structures found within each settlement vary, but some of the largest settlements, such as Yalape, La Xalca, and Olan, lie on the eastern Utcubamba slopes, facing Kuelap, and encompass upwards of 300-500 dwellings. Some houses exhibit stone cornices, stairways, and niches, and feature structurally incorporated embellishments with carved tenoned heads, bas relief slabs, and geometric friezes using inlaid stone slabs. The variability of quality and elaboration of the stone houses probably correspond to status differences and differential abilities of their owners to muster sufficient labor and other resources [

53]. While a great deal more research is needed to explore regional chronologies, regional populations were likely organized in mobile and semi-sedentary families and communities. Hilltop settlements of stone apparently increased slowly in number after AD 800 and 900, and proliferated by AD 1200, as did mortuary practices of interring the dead in cliff tombs, perhaps signaling information regarding territories [

54,

55,

56]. Interments deep within caverns are more difficult to interpret.

Archaeological fieldwork in the region throughout the 20

th century was sporadic, and useful results were relatively scarce and/or lacking critical details and precision compared to that in other Andean regions. Until the mid-20

th century, most archaeologists were convinced that the presence of abandoned settlements and other cultural remains in the cloud forest of Chachapoyas could best be explained as evidence of late pre-Hispanic agricultural colonization by highland polities seeking access to forest resources [

57] or society-level migrations eastward by populations responding to demographic pressures [

58]. Both interpretations were built on the assumption that all eastern montane forest occupations were subsidized highland colonial enclaves. The speculations were called into question when another generation of archaeologists began to conduct systematic research and present published data [

8,

59]. Foreshadowing new methods and interpretations to come, Peruvian archaeologist Arturo Ruiz Estrada excavated below a house’s foundation on the northern edge of Kuelap’s Pueblo Alto sector, where he encountered a large assemblage of cultural remains predating the ubiquitous Chachapoya stone constructions [

60]. The deposits of unexpectedly early remains continued several meters to bedrock, and Ruiz recovered thousands of pot sherds, burnt animal bones, stone artifacts, and uncovered a fire hearth and a buried floor. The continuity of pottery types suggests that there was no population replacement. The achievements of Ruiz were not immediately recognized, but soon other archaeologists were locating surprisingly early pottery beneath stone architecture, in middens, and on open ridgetops at similar elevations, eventually leading professional archaeologists to discard migration hypotheses.

At present, a full and nearly continuous archaeological record of human occupation dating back to the terminal Pleistocene is under development as the expansion of modern infrastructure makes many previously sites more accessible and still others are uncovered and identified as deforestation advances. This once-forested and forgotten region is currently being repopulated by peoples of varying origins. Unfortunately, a new wave of agricultural immigration is accompanied by accelerating deforestation. Archaeological and ethnohistorical information regarding Indigenous cultures in Chachapoyas remains insufficient to offer a clear view of the local pre-Hispanic cultures. The present relative lack of published primary data from Kuelap and the surrounding region enables the construction of contrasting, competing narratives that need to be demonstrated.

1.4. Description of La Fortaleza

Figure 4.

An artistic rendering of La Fortaleza and its main buildings, with an impressionistic depiction of the locations of circular structures and special buildings. 1) Circular platform; 2) Main Temple / Tintero; 3) Access 1; 4) Access 2; 5) Perimeter wall; 6) Access 3; 7) Upper Town / Pueblo Alto; 8) Upper Town Southern Sector; 9) Upper Town Central Sector; 10) Upper Town Northern Sector; 11) The Turret / Torreón. Courtesy of MINCETUR Peru.

Figure 4.

An artistic rendering of La Fortaleza and its main buildings, with an impressionistic depiction of the locations of circular structures and special buildings. 1) Circular platform; 2) Main Temple / Tintero; 3) Access 1; 4) Access 2; 5) Perimeter wall; 6) Access 3; 7) Upper Town / Pueblo Alto; 8) Upper Town Southern Sector; 9) Upper Town Central Sector; 10) Upper Town Northern Sector; 11) The Turret / Torreón. Courtesy of MINCETUR Peru.

Undoubtedly the most famous archaeological monument in the Amazonas region, La Fortaleza de Kuelap shares many elements with other Chachapoya sites (

Figure 4). Its ridge-top location, circular structures (often built on platforms, accessed by stairs and cantilever walkways, and decorated with friezes), and defensive affordances (which include highly restricted access points and hidden stairways) are common among regional settlements that appear to have had substantial occupations in the Late Intermediate Period (ca. 1100-1450 CE). Evaluated by both its extent (5.11 hectares, as recalculated from the current LiDAR surveys) and the number of domestic structures it contains (at least 420), the settlement atop La Fortaleza is large, but by no means larger than other prominent sites in this region, such as Purumllacta de Cheto and La Joya [

5,

8]. Some of its friezes are impressive, but its structures are in themselves neither larger nor greatly more elaborate than those found at other prominent sites in southern Amazonas. In addition, research conducted in smaller sites near Kuelap suggests that leveling and filling may have been common forms of landscape modeling in this territory [

61]. All these characteristics––along with the ethnohistorical evidence reviewed above indicating that the region was not politically centralized before the Inka invasion––suggest that it would be inaccurate to consider La Fortaleza, and Kuelap more generally, as a “capital” site.

That said, the scale of La Fortaleza’s perimeter walls greatly exceeds that of those found at any other known walled archaeological sites in Amazonas and the monument contains several singular features. Mortuary contexts are found in particular abundance at the site, in a great diversity of contexts ––cists under house floors, above-ground open structures (

chullpas), burials in La Fortaleza’s monumental walls themselves, a common grave that may correspond to a “massacre”, and cliff tombs in the adjacent Cerro Barreta [

62,

63]. The southern and northern ends of the site contain distinctive structures – at the south, the

Templo mayor and Circular platform, which may be associated with ritual activities; in the north, the

Torreón, which provides a relatively high vantage point over the adjacent slopes (Figure 7). Structures are divided between the so-called

Pueblo bajo and

Pueblo alto, which is separated from the remainder of La Fortaleza by another high stone wall with highly controlled access points, and which contains an area of exposed bedrock. Ruiz’s excavations in this area suggested that it may correspond to the oldest area of the site, and that it maintained particular importance during later eras. Also suggestive of the monument’s history of north to south accretion can be found in the report of the excavations conducted by Reichlen and Reichlen [

64] at the south end above the main entryway and next to the Templo Mayor. They recovered only Late Horizon and Late Intermediate Period materials lying directly atop La Fortaleza’s construction fill. The Reichlens’ report findings contradict radiocarbon dates described for La Fortaleza [

36], so additional research is required. Inka modifications to the site included the placement of a long, multi-doored feasting hall (typically called a

kallanka) immediately atop this area of exposed bedrock, as well as the construction of a smaller such feasting hall near the

Templo mayor, at the southern end of the site.

Visitors and literature now use the name “Kuelap” to refer to the tourist attraction of La Fortaleza. The extensive archaeological landscape to the east has received little archaeological attention, and communities are growing at Anexo Kuelap. Recent research on the Anexo identified abundant evidence of settlement by large and small groups from early pre-Hispanic times to the present. During the 1960s, archaeologist Arturo Ruiz explored the Anexo, and his thesis includes short descriptions of several archaeological localities, along with the results of his 1967 excavations at La Fortaleza. He estimated that the Anexo could have originally encompassed twice as many households as La Fortaleza’s total of 420 [

15,

16]. In recent years, archaeologists taking advantage of the area’s increasing deforestation have identified over 15 “sites” scattered across the Anexo that, together with La Fortaleza, functioned as integrated sectors within a single, expansive archaeological landscape (

Figure 5). Based on his fieldwork in and around La Fortaleza, Narvaez [

36] agrees that the monument and sectors below belong to one large archaeological complex. Although the passage of five centuries of human activities and recent settlement constructions have surely erased other sectors and evidence of interconnections, La Fortaleza might be more accurately considered the highest and most prominent element of a single yet very large Kuelap Archaeological Complex [

32,

33,

34,

39,

42,

60,

65].

Figure 5.

Archaeological sectors identified within the Kuelap pre-Hispanic landscape. Redrawn with location data from H. Dionne [

66]. UTM Zone 18S, WGS84.

Figure 5.

Archaeological sectors identified within the Kuelap pre-Hispanic landscape. Redrawn with location data from H. Dionne [

66]. UTM Zone 18S, WGS84.

2. Materials

This study draws on data collected by several research teams, which we discuss in turn below (

Figure 6). In the following sub-sections we present, as far as possible, the sources of these data and their acquisition and processing methods.

Background data, collected through archival research and local interviews. They include earlier publications, reports, and photographic documentation

Plans of the site from topographic surveys between 1985 and 2010

Data from terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) collected between 2018 and 2022

Data from light detection and ranging (LiDAR) systems mounted on UAVs used in 2019

Photographs from UAV surveys collected in 2022

Archival satellite RGB and NDWI data collected between 2005 and 2022

Electrical resistivity tomography (ERT), Vertical Electrical Soundings (VES) and seismic refraction data collected between 2019 and 2023.

2.1. Background information on the site

Several sources of background information are relevant to this project’s goals. First are the publications left by late 19

th and early 20

th century travelers and visitors to Kuelap [14,32,40,43,64,67-71], which uncovers an early preoccupation and discussion over the ways to manage the conservation of the site, especially in relationship to its vegetation cover. Second are excavation and conservation reports from teams led by archaeologist Alfredo Narváez and others [

36,

72]. Third are reports and other documentation from the Ministry of Culture, especially those summarizing the state of conservation of specific site sectors, including readings from fissurometers (crack spies) collected since 2017 [

73]. Although they do not reveal general knowledge about the deformation nature of the whole structure, they can provide useful insights into the time-related development and the current stages of displacement cycles at certain places. Fourth is information offered by inhabitants in the vicinity of La Fortaleza, who have worked on various excavation and conservation projects at the site since 1985 [

73].

2.2. Plans of the site

Early visitors created the first site maps during the late 19

th and early 20

th centuries [

32], and teams led by Narváez created more detailed maps based on a topographic survey of its structures using theodolites and total stations in the 1980’s through 2000’s [

36,

37]. In recent years, digital versions of the maps have been updated –– including one produced in 2009 by Plan Turistico y Cultural Peru-UNESCO (COPESCO) (

Figure 7), and again in 2015 during efforts to restore Acceso 1. Their detail and accuracy are similar, and both use the UTM projection (Zone 18S) and the WGS 1984 datum.

Since the instruments available at the time required that every survey point be individually recorded (and sometimes recorded by hand), the resulting maps are very schematic and do not have the spatial resolution necessary to capture all the idiosyncrasies of the site’s individual structures, including the positions of individual stones within [

61].

2.3. Terrestrial laser scanning (TLS)

Before the 2022 collapse, portions of La Fortaleza were scanned using terrestrial LiDAR (TLS), whose extremely high point densities are well-suited for documenting the vertical surfaces of standing stone architecture. In October 2019, Kucera, VanValkenburgh, and Rojas completed a partial TLS survey that documented the portion of the perimeter wall that collapsed in April 2022, as well as most of the eastern perimeter wall, Acceso 3, and Pueblo Alto. This dataset was collected with a Riegl VZ-2000 (RIEGL LMS) provided by COTECMI, a Peruvian company. Based on the technical parameters of the instrument, one can expect the best 3D accuracy of the resulting point clouds to be 3 mm at a 50 m distance for each scan position. Nevertheless, the actual accuracy must be assumed slightly higher, due to the alignment of the different scan positions and varying environmental parameters (e.g., temperature, air pressure, humidity). The applied angular resolution of 40 mdeg guarantees approximately 50 points/cm2 of average point density at the areas of interest (i.e., within the vicinity of up to 20 m of the survey path, along which the laser scanner was placed, each scan position separated by less than 15 m). Within three days, 250 scan positions were recorded, starting in the southern sector, following the visitor´s path along the west perimeter wall, entering La Fortaleza at Accesso 3, continuing to the Pueblo Alto sector, and ending in the central sector.

2.4. Drone LiDAR data

Drone LiDAR data provide a complementary source of spatial information for documenting La Fortaleza. At the time of this study, two sets of LiDAR 3D point clouds collected from drones were available to the authors. The first was acquired in August 2018 by VanValkenburgh, Rojas, and colleagues using a system based on Velodyne VLP-32 mounted on a DJI Matrice 600 Pro commercial hexacopter [

61].

The second set of LiDAR data was recorded by Giovanni Righetti and colleagues. The data acquisition took place in November 2019, using the Riegl VUX-1 sensor attached to a GEOX 7 hexacopter drone developed in Peru by Robotic Air Systems [

74,

75].

2.5. Digital photogrammetry

Alongside terrestrial and drone LiDAR data, we also analyzed the results of several UAV-based photogrammetric surveys conducted after the 2022 collapse, to reconstruct the damage. On April 12th, 2022, after the collapses had stopped, Roger Vigo used a DJI Mavic Mini 2, with a 1/2.3” CMOS sensor and 24 mm (35 mm format equivalent) lens that produces 4000×2250 size images. A second dataset was captured on April 30th, 2022 by Napoleon Vargas, using a DJI Mavic Air equipped with a 1/2.3” CMOS sensor and a 24 mm (35 mm equivalent) lens that produces 4056×3040 size images. Both surveys photographed and filmed the collapsed area and its surroundings on the southeastern corner of the site, before it was sheltered with protective roofing by the Ministry. A third dataset was captured on June 14th, 2022 by Contreras, using a DJI Phantom 3 equipped with a Sony EXMOR 1/2.3” CMOS sensor and a 20 mm (35 mm equivalent) lens that produces 4000×3000 size images. Contreras surveyed the whole southeastern corner of the site and, although the collapse had been already covered, it produced data suitable for high-quality IBM models of that section of La Fortaleza (Figure 22).

2.6. Satellite data

Two types of publicly available satellite data were used in this study. The first type was historical, high-resolution RGB imaging (8192×4897 pixels) from Google, acquired with the Google Earth Pro application (

Figure 8). The images from July 2005, June 2012, November 2014, August 2021, and June 2022 were selected as the best illustration of the changes in the vegetation cover of La Fortaleza (Figure 13).

We also collected all cloudless Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) images in the last two years from the Sentinel-2 L2A satellite, that is, 11 images for the year 2021, and 10 for 2022. The NDWI is used to monitor changes related to water content in water bodies. In the case of Sentinel-2 data, this index is calculated according to the equation NDWI = (NIR - MIR)/(NIR + MIR), where: NIR – is Near Infrared band 8, and MIR – is Mid-Infrared band 12. Their resolution and central wavelength are respectively: 10 m/842 nm and 20 m/2190 nm. The time intervals between the individual images range from 2 weeks to 2 months. In the analytical section of this study, this satellite data was used to monitor seasonal and annual changes in the ground moisture of La Fortaleza.

2.7. Electrical resistivity tomography (ERT), Vertical Electrical Soundings (VES), and Seismic Refraction

Besides the remote sensing datasets described above, this study has integrated near-surface geophysics, in the form of electrical resistivity and seismic refraction surveys. In 2019, Jorge Barriga carried out for Plan COPESCO a resistivity survey around Acceso 1 [

76], using the Syscal Pro resistivity meter with a multichannel pole-dipole electrode arrangement for 10 ERT transects, and Schlumberger arrangements for 11 VES [

77]. In 2021, Mori carried out 3 longitudinal and 10 transversal ERT profiles (

Figure 9), covering the top of La Fortaleza [

78]. Mori used the ARES I 850W resistivity meter from GF Instruments, following a dipole-dipole arrangement [

79]. In 2022, the Ministry of Culture contracted ALEPH Asociados for a geophysical study involving 2 longitudinal and 18 transverse ERT profiles (

Figure 9), and 27 VES, with a Schlumberger Symmetric Linear tetra-electrode configuration, complementing Mori’s coverage of La Fortaleza [

80].

The results of the application of ERT and VES in these three geophysical surveys are consistent and complementary to each other. Due to the quality of graphics available, the illustrations of further analyses of resistivity data in this study are based on the ERT data collected and processed by Mori (

Figure 10).

In 2023, Mori developed a geo-seismic profile of La Fortaleza (

Figure 11), by measuring with an array of geophone sensors, the variations in the velocity of the primary compression waves generated by 40 seismic refraction lines, evenly divided between 50 m and 100 m arrays [

81]. The technique is used to interpret the depth and composition of soils and rocks, to characterize subsurface geologic conditions and stratification. With this data, Mori modeled in 3D the bedrock under the platform and estimated the size of the fill.

The reports on all these geophysical surveys contain valuable observations on the geological structure of La Fortaleza and its hydrological conditions, which are important elements for analyzing the mechanisms of the damage to its perimeter walls.

3. Methodology of the study and applied methods

As previous authors have suggested [

78,

82,

83], we propose that the root cause for the collapse is the increasing moisture within the fill behind the perimeter walls of La Fortaleza. Hence, our methodology and applied methods were subordinated to the task of evaluating this hypothesis as the primary objective. The main study goals revolve around finding answers to these two fundamental questions: 1. Is there a correspondence between surface rainwater runoff and soil moisture?; 2. And if so, which features of the terrain micro-landscape pose the most significant threats, and in which specific places do these threats occur?

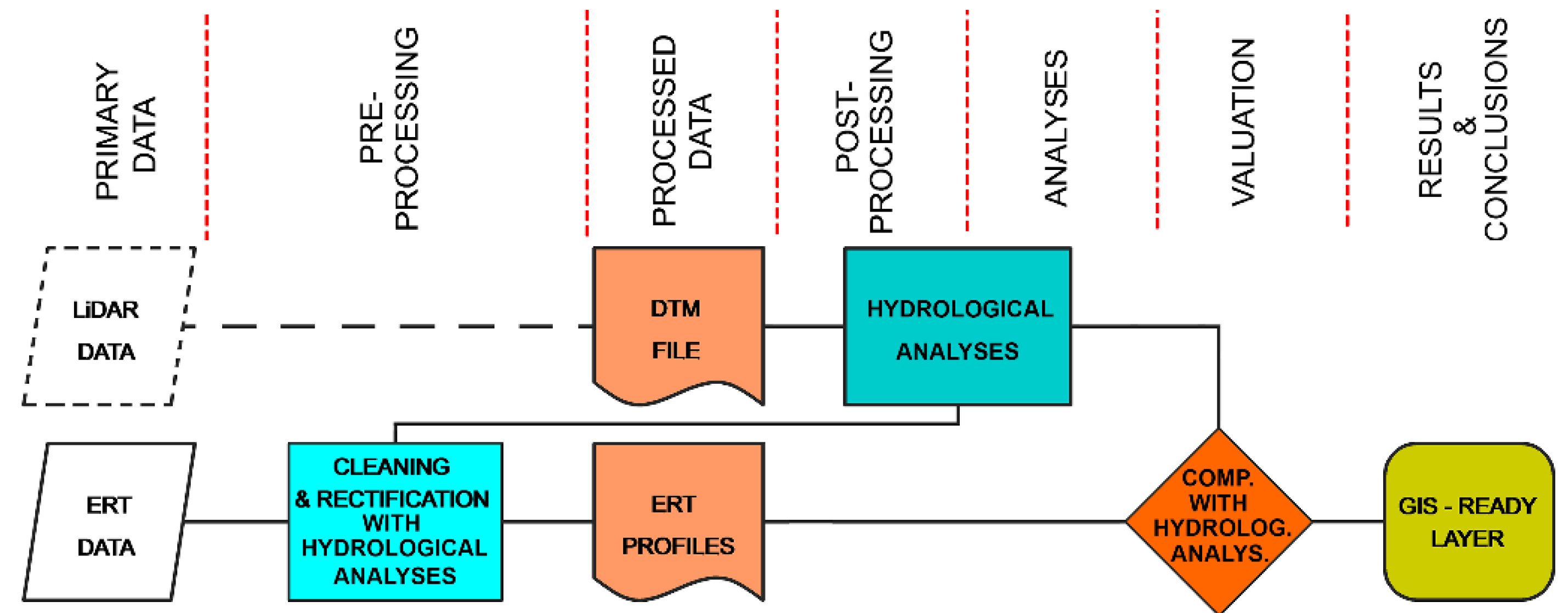

Additional questions relate to the direction of further archaeological and architectural research and the possibility of using remote sensing data. From the methodological point of view, our research process could be divided into seven steps: 1) primary data gathering; 2) primary data preprocessing; 3) processed data evaluation; 4) data postprocessing; 5) analytical phase; 6) valuation phase; 7) synthesis of results

The last step includes two components: the data that will constitute thematic layers on a proposed Kuelap GIS, and the restoration recommendations based on our results. Considering our current study and accompanying observations, the former seems to be a prerequisite for any action aimed at implementing a comprehensive solution to the conservation problems at La Fortaleza.

The following sub-sections will discuss five key areas leading to answering the two fundamental research questions posed above. The general logic of these studies, data flow, and applied methods are synthesized in the diagrams at the beginning of each subchapter.

3.1. The general plan of the site

On any archaeological site, the primary study material is its most accurate and detailed plan. This is particularly important in the event of threats to the site, even more so for one on UNESCO´s tentative list of World Heritage sites. In the COPESCO plan (

Figure 7), the location, the shape, and even the existence of individual buildings differs significantly from the reality observed in the published LiDAR survey [

61] and other LiDAR data [

75]. These discrepancies, and at the same time, the existence of recent LiDAR surveys [

84,

85] urges the need for a new, more accurate, and up-to-date site plan of La Fortaleza.

Such a site plan would be the base layer in Kuelap GIS, where all the interested parties and research teams might deposit their products. Further, using TLS and close-range digital photogrammetry, this base layer would be supplemented with more detailed "stone by stone" drawings, as postulated and practiced by Kościuk [

86] (pp. 11-15), [

87]. Recent advances in the fusion of digital photogrammetry and TLS data render this working path even more efficient [

88,

89].

Figure 12 represents the data flow for the proposed Kuelap GIS general plan layers.

3.2. Deforestation analysis

A cursory analysis of historical satellite images available on Google Earth Pro reveals ongoing deforestation at the top of La Fortaleza (

Figure 13). Even more dramatic changes can be observed by comparing the present state with aerial pictures from 2000 (

Figure 1), showing that, relatively recently, most of the top of La Fortaleza was densely covered by vegetation, save for areas around the gates and the main buildings, such as Plataforma Circular, Templo Mayor, and Torreon.

A case-by-case review of the potential effects of deforestation significantly exceeds the scope of this article. Nevertheless, the data flow adopted in this study provides for the analysis of data collected so far and availability for further, more detailed research in the form of a thematic layer of the proposed Kuelap GIS System. However, Google Earth images are not precisely nadir-orientated, and their topographic projection is not consistent. Using them for quantitative analysis would require rectifying individual images based on a common template. As such, the digital terrain model (DTM) derived from UAV LiDAR data could be used for the rectification (scaling, rotation, distortion, and translation) of individual images within a suitable software environment.

Figure 14.

Diagram for deforestation analysis. Elaborated by Kościuk.

Figure 14.

Diagram for deforestation analysis. Elaborated by Kościuk.

3.3. LiDAR data visualization and hydrological analysis

As already mentioned, our data source for describing the terrain and architectural remains atop La Fortaleza was the UAV LiDAR survey provided by MEDS AMSTERDAM. The primary data filtering and classification processes were conducted with ATLAS (

www.theatlasgis.com), proprietary software created by MEDS AMSTERDAM (

Figure 15).

The resulting data, received in *.las format, was preliminarily classified into three groups:

However, in such rugged terrain, full of hardly distinguishable clumps of vegetation and ruins of walls, with varying degrees of damage, an additional inspection of the 3D point cloud and reclassification was necessary. Due to the main purpose of the study, and the characteristics of the site, new classes were introduced:

This led to the reclassification of 3D point clouds – in some cases, automatically executed in Leica Cyclone 3DR v. 2023.1 software and, in some instances, also manually. These interventions were limited to the following cases:

automatically filtrating vertical and sloping walls, and moving them from the "never_classified" class to the new "ground and architecture" class,

manually selecting previously unfiltered vegetation clumps and moving them from the "ground" class to the "low_vegetation" class,

manually selecting vegetation growing on vertical and sloping walls and moving it from the "ground and architecture" class to the new "vegetation on walls" class,

in a few instances, manually selecting parts of the "low_vegetation" class that may represent the slopes and the tops of circular hills where relics of round buildings are buried and moving them to the "ground and architecture" class.

The final 3D cloud in *.las format (WGS 1984 UTM Zone 18S), consisting only of the "ground and architecture" class, was used in ArcMap v.10.6 software function “Las Data Set To Raster Conversion Tool” to produce a DTM file of 10 cm resolution, representing the bare ground surface, which includes walls and other building remains. The steps to obtain the most detailed terrain maps as input data for the development of hydrological and risk maps are described in the following two subsections, while the whole methodology is presented on

Figure 16.

3.3.1. DTM postprocessing with Relief Visualization Tool Box (RTV)

The detailed DTM file allowed the use of analytical tools built into GIS packages, and specialized tools for detecting buildings and archaeological features. We used the Relief Visualization Toolbox v.2.0 [

90], a standalone application that further processes the DTM files. The choice of analytical tools included:

Unidirectional hill-shading [

91] (p. 41),

Multidirectional hill-shading up to 64 azimuth directions,

Principal Component Analysis of hill-shading [

92] (p. 472),

Slope gradient [

93] (p. 47); [

94] (p. 285),

Simple local relief model,

Sky-View factor, and Anisotropic Sky-View factor [

95] (p. 402); [

90],

Openness (negative and positive),

Local dominance

However, there is no single and straight rule for which visualization modes will most effectively detect and emphasize the desired features [

97] (p. 288); [

93] (p. 47). Due to the diverse nature of the features in the given study area, it is a matter of many trials, using different algorithms with different settings. In our case, the most effective were unidirectional hill-shading (HS), multidirectional hill-shading (MHS), slope gradient (SG), and openness-positive (OPEN-POS). Each represents different aspects and features of the terrain in question (

Figure 17). Important additional information that characterizes the area's landscape is supplied by hypsometry (

Figure 17 HYPSO). However, the most detailed information was brought up by using a special Mixer mode built into the RVT, allowing for the combination (with a certain degree of transparency) of up to five different basic visualization modes (

Figure 17 VAT).

The results of all the visualization modes listed here have been used as thematic layers both in the GIS system and in the form of raster references in CAD projects. Depending on the needs, it allows changing the background against which individual problems are analyzed.

3.3.2. Hydrological analysis based on DTM

Past mitigation activities in the southern sector of La Fortaleza, and more precisely, the installation of various drainage systems, indicate that the infiltration of rainwater into the fill was understood since the 1980s as one of the main causes of deterioration [

98]. However, the authors have not found hydrological analyses simulating rainwater runoff at the site, nor technical documentation of the existing drainage systems, considering, for instance, calculations of all the rainwater flows, slopes, or the diameters of drainage pipes.

Drainage projects require certain hydrological analyses as input data, which can be conducted based on the detailed DTMs produced from UAV LiDAR survey, which show the relief of the terrain of La Fortaleza along with all its extant architectural remains. On this basis, the main elements of the hydrological system can be determined:

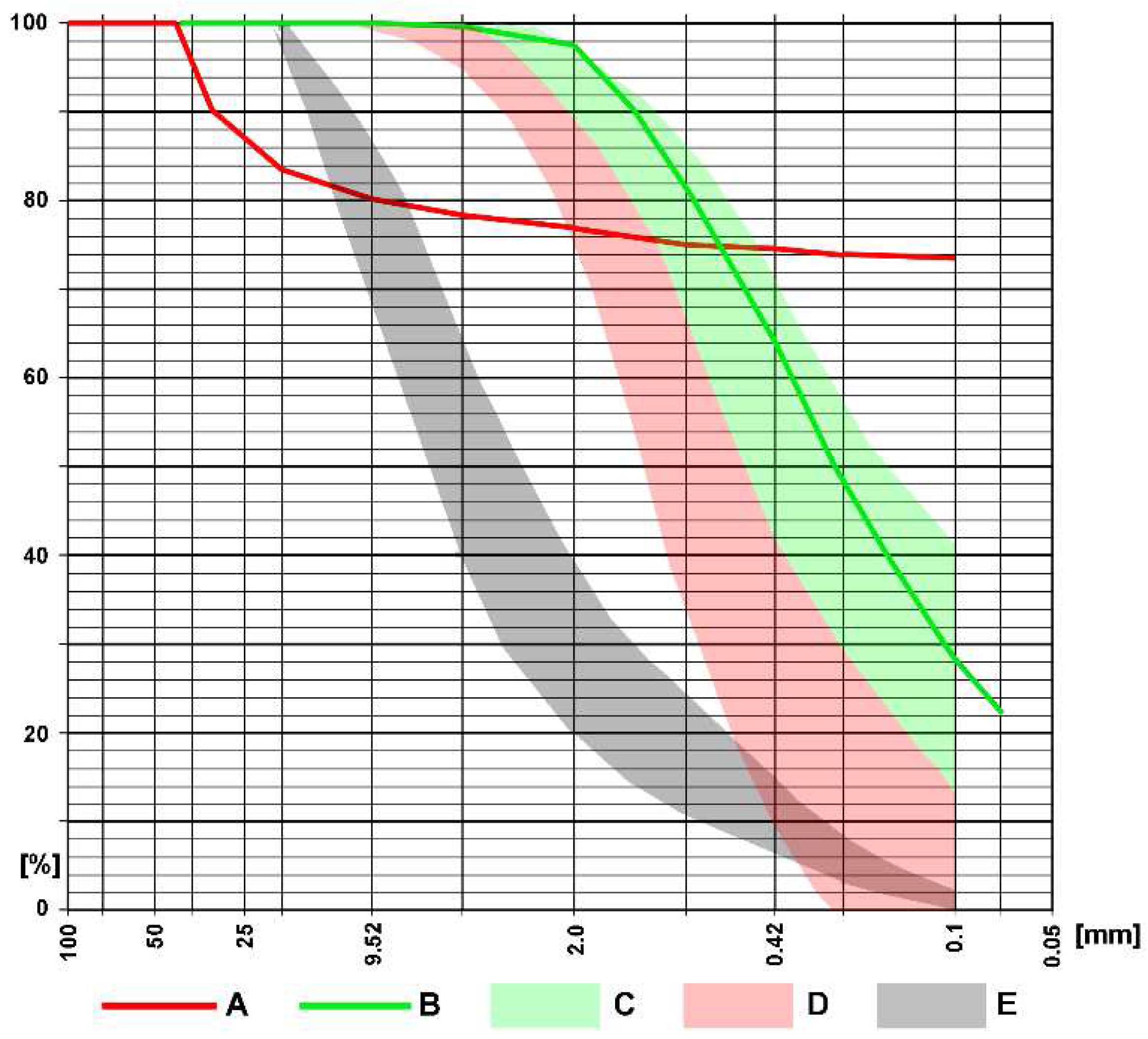

slope gradient, which, along with other parameters, will indicate the proportion between surface runoff and infiltration into the ground (

Figure 18 A),

local depressions, where rainwater can only evaporate or soak into the ground (

Figure 18 B),

boundaries of individual water catchments and their areas - necessary as input data for calculations of the drainage system (

Figure 18 C),

3.4. Comparison of ERT data with the results of hydrological analyses

To study the possible relationships between precipitation at La Fortaleza and threats to the monument, we have integrated our data from hydrological analyses with the results of geophysical surveys (

Figure 19), specifically, the ERT readings collected by Mori [

78], (

Figure 20).

All ERT profiles were plotted on the hydrological analysis maps to allow for direct comparison between modeled hydrological risks and evidence of increased humidity (

Figure 20).

Figure 20.

ERT LTE 01 profile plotted against the background of hydrological analysis on a hypsometric map: the red arrow on the left shows the coincidence between a rainwater runoff line and a zone of increased humidity; the right red arrow shows the influence of a local depression on the increase in soil moisture; the blue arrow points to the increased humidity of the structured fill behind the perimeter wall of La Fortaleza. Hydrological analysis by Dąbek; ERT profile by Mori; hypsometry and data assembling by Kościuk.

Figure 20.

ERT LTE 01 profile plotted against the background of hydrological analysis on a hypsometric map: the red arrow on the left shows the coincidence between a rainwater runoff line and a zone of increased humidity; the right red arrow shows the influence of a local depression on the increase in soil moisture; the blue arrow points to the increased humidity of the structured fill behind the perimeter wall of La Fortaleza. Hydrological analysis by Dąbek; ERT profile by Mori; hypsometry and data assembling by Kościuk.

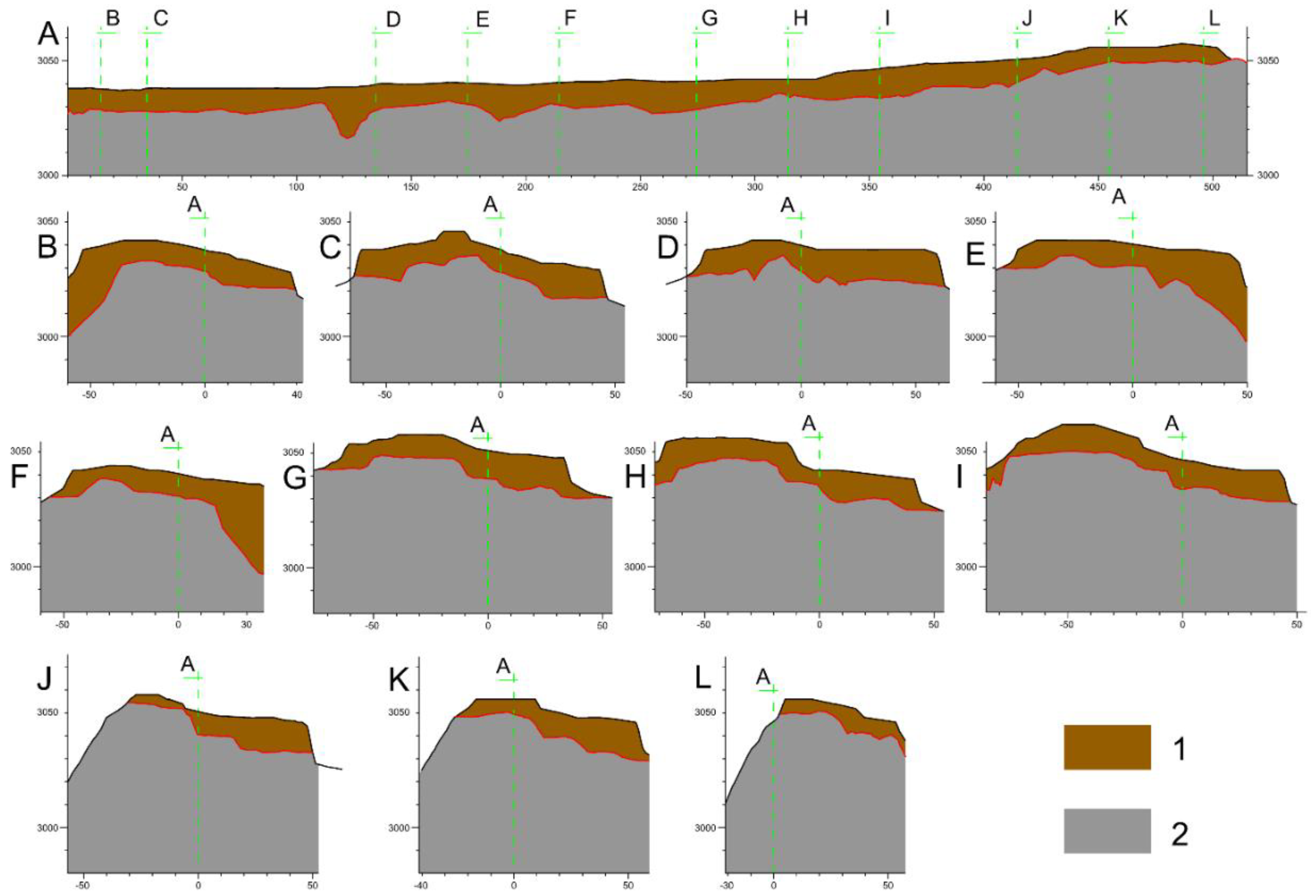

3.5. Stratigraphy of La Fortaleza using seismic refraction

The measured variations in the velocity of the primary compression waves (V

p) generated by the seismic refraction lines were processed using the applications SeisImager2D, version 3.3 and Easy Refract, version 20.4.518, to generate 2D geoseismic profiles of La Fortaleza (

Figure 11). To estimate the volume of the existing construction fill, the resulting stratification was reclassified into two major strata: the construction fill, composed of limestone blocks and argillaceous clay plus the topsoil, as a single unit, and the underlying limestone bedrock (

Figure 21). To estimate the difference between both strata Mori used the application Oasis Montaj, version 9.3, to model in 3D and in high resolution the current surface of La Fortaleza’s platform and of the bedrock, using as a point of contact with the bedrock a V

p speed of 2000 m/s. Finally, the 3D surfaces of the bedrock and the current surface were analyzed in AutoDesk Civil 3D 2023, and from the difference between both, the volume of the existing construction fill was calculated at approximately 600,000 m

3.

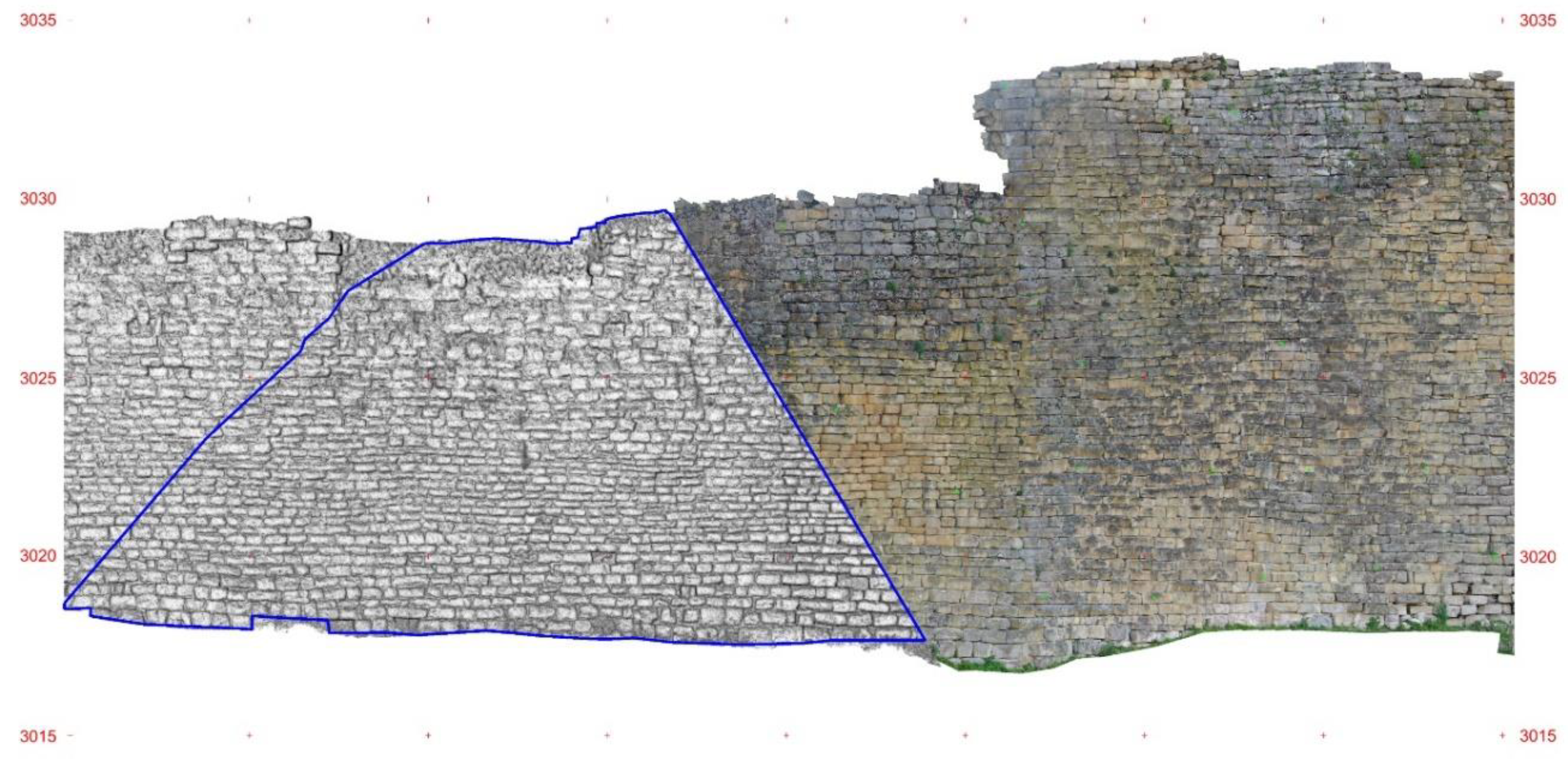

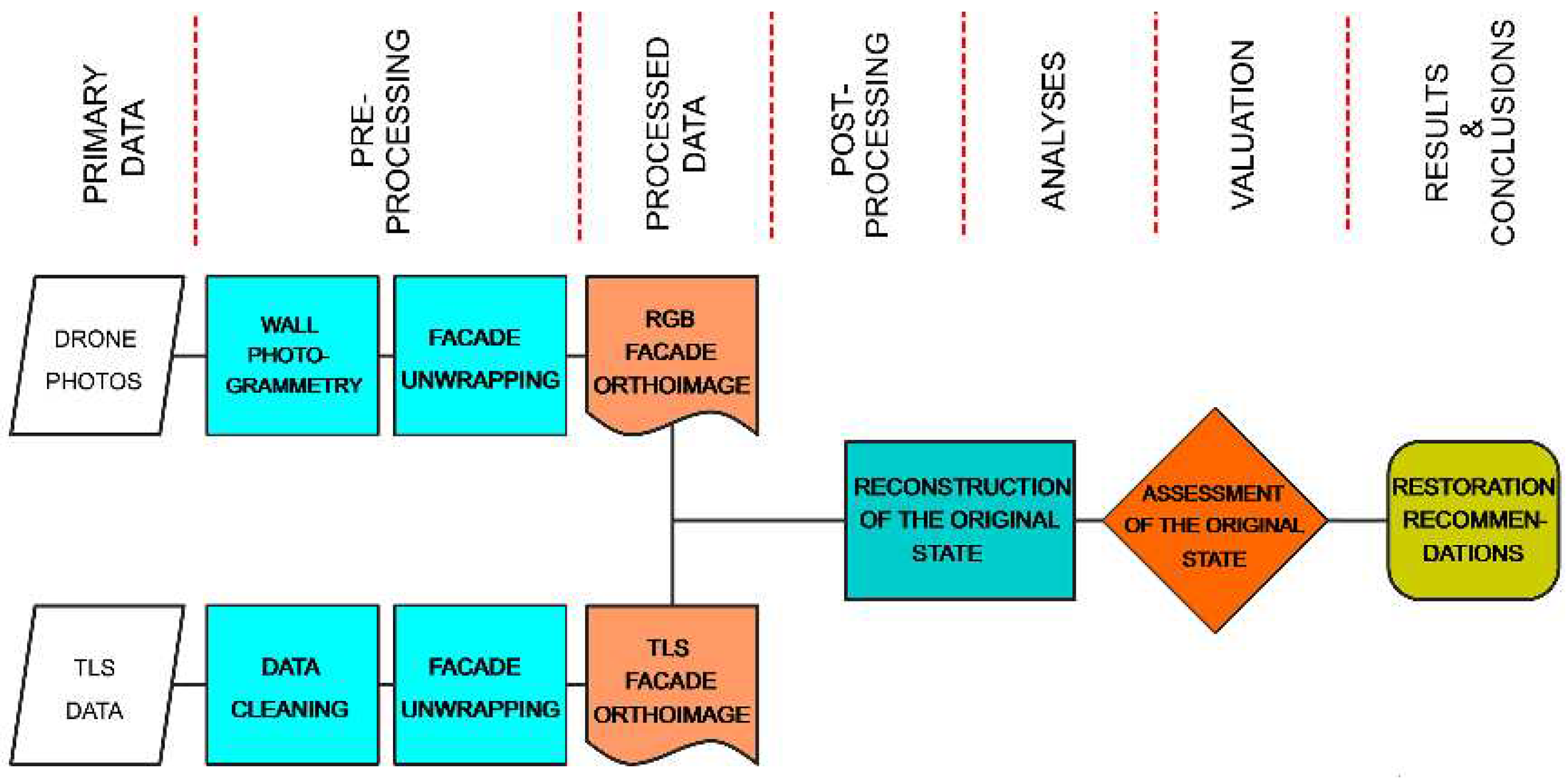

3.6. Fusion of Image-Based Modeling (IBM), ALS and TLS data

No pre-collapse “stone by stone” documentation of the perimeter wall that collapsed in April 2022 wall exists, but fortunately, Kucera, VanValkenburgh, and Rojas collected TLS data in 2019, which we combined with IBM and ALS data. The detailed examination of these integrated datasets allowed us to produce results that are crucial to understand the reasons for the collapse: 1) detailed “stone by stone” plans, 2) techno-morphological analysis, and 3) multitemporal deformation studies.

These data will be of great importance in formulating conservation guidelines specifying the scope and treatment methods for the collapsed parts of the perimeter walls of La Fortaleza. We are referring both to the data available for this study, and, above all, to any other data documenting the condition of the walls before April 2022.

3.6.1. Detailed “stone by stone” plans

Recent advances in the fusion of digital photogrammetry and TLS data offered by AgiSoft Metashape 2.0.4 render this working path even more efficient [

88,

89]. Given a sufficient overlap between TLS and photogrammetry projects, and supplying well-spaced and equally distributed ground control points, such integrated documentation can provide a fast and accurate source for a more detailed study (

Figure 22).

Another approach to combining photogrammetric and TLS data for restoration documentation is to use their 2D deliverables.

Figure 23 explains the data flow for this method particularly efficient when documenting the facades of any walls as well as the ground plans of the site. In both cases, such integrated data (2D drawings and/or 3D models) can be used as a base for any conservation or restoration purposes.

3.6.2. Techno-morphological studies

Although there are many studies of Inka masonry [99-105], save for Protzen's research on the evidence of construction phases in Ollantaytambo [

103] (pp. 241-256) and his study on the sequence of laying stone blocks at Sacsayhuaman’s retaining walls [

101] (Figure 37, p. 181), in-depth techno-morphological approaches have only been adopted recently [

106,

107]. Even less can be said about the use of such approach concerning Chachapoya masonry. One of the reasons for this situation is the lack of sufficiently accurate “stone by stone” documentation of the remains of Chachapoya buildings. The approach proposed above (a fusion of digital photogrammetry and TLS data) may change this situation in the case of the straight portions of walls. However, most Chachapoyas constructions are oblong or circular, making this method difficult to apply. Unrolling the faces of inclined walls of an irregular plane is a time time-consuming task, demanding a lot of additional data and computer power. Nevertheless, there are methods that quickly give results good enough for our purposes. Many modern applications, both photogrammetric (for example AgiSoft MetaShape) and those operating on TLS data (for example Leica Cyclone 3DR v. 2023.1), have built-in modules for unrolling cylindrical surfaces.

Even a relatively complicated curved wall can be divided into sections with an approximately constant radius. Since the inclination of these walls rarely exceeds 10 degrees, it gives the chance to use a cylindrical surface as a good enough estimate of such a fragment of the wall. The next step is to use one of the applications mentioned above, unrolling subsequent sections of the wall, and stitching them into one image. Depending on the software used and the input data, this method can be used either on 3D mesh models or directly on 3D point clouds. The resulting unrolled “pseudo-ortho” image can be used as a raster reference on any 2D CAD program for further vectorization, delimiting zones of special interest, and calculating their area. Finally, it can be also used for techno-morphological studies.

3.6.3. Deformation analysis based on multitemporal hybrid data

One should have also in mind the use of multi-temporal data. Data from two different measurement epochs (for example before and after the collapse) can also help reconstruct the chain of events that led to this catastrophe [

108,

109]. An analysis of the perimeter wall deformations 'on the eve' of a disaster can be particularly indicative. Such analysis will require two steps:

referencing data from both epochs into a common coordinate system,

cleaning the 3D point cloud data from vegetation growing on the wall and any moving objects.

The first step determines the credibility of the analysis. Poor matching of the compared 3D point clouds may result in an incorrect estimate of deformations that may have occurred between two surveys distant in time. The second step is equally important. If the 3D point cloud is not effectively cleansed of data representing vegetation, analyses (usually Cloud2Mesh comparison) will mostly show changes in vegetation cover. However, cleaning 3D clouds from vegetation is very challenging, especially when the background is an inclined stone wall made of heterogeneous blocks with a variable angle of inclination and a complex distribution. This requires either labor-intensive manual cleaning of the cloud, or specific filtration methods adequate to this situation.

In the case of the April 2022 perimeter wall collapse, we fortunately had three sets of data collected before the disaster and one data set acquired directly after the collapse. Two of them were aerial LiDAR surveys (ALS) from 2018 and 2019 collected by MEDS AMSTERDAM and VanValkenburgh et al. [

61]. Georeferencing of both was based only on GPS data and no ground control points (GCP) were set for either survey. Besides, the resolution of the 3D point clouds representing the perimeter wall greatly exceeded 1 cm. All this, and the difficulties in clearing the point cloud from data representing the vegetation growing on the walls, did not allow for an effective analysis of deformations that could have occurred between these two surveying epochs.

The third pre-collapse data were from the TLS survey carried out in 2019 and referenced to existing geodetic points in the area with known coordinates. The resolution of these data was not worse than 1 cm. Unfortunately, also in this case, deformation cross-analyses between both sets of ALS data and the TLS data did not bring satisfactory results. Therefore, it can be concluded that in this case, ALS data are not suitable for multitemporal deformation analyses.

We also had a fourth set of data at our disposal - pictures taken from a drone collected by Roger Vigo the day after the collapse of the perimeter wall in April 2022. Due to concerns for the safety of the pilots and their equipment, no ground control points (GCP) were placed for the first two UAV surveys of the collapsed area of La Fortaleza. GCP are crucial for the correct scaling and georeferencing of the resulting IBM models. Also, only GCP guarantee identifying possible distortions. To overcome this problem, five control points were defined using the TLS data from 2019. Distinct points (cracks, edges of stones), which are detectable and distinguishable in both TLS and IBM data, have been defined in RiscanPro 2.14.1, and exported in the respective projection (WGS84 UTM 18S).

In general, the resolution of an IBM model is defined by the sensor used, the average working distance, and the number and quality of images. Thus, a high number of images taken from various positions and distances is preferable. The data available from the two UAV surveys conducted before the collapse was covered sums up to only 25 images, resulting in a rough model –- of great value nevertheless, as it predates the later covering of the area, and enables an estimation of the collapsed volume. For the processing, Agisoft Metashape 1.7.2 was used, using the control points previously defined in the TLS dataset from 2019, at a resolution of 1 cm. This results in a positioning accuracy of 2 to 3 cm for each of the five defined control points. Their positioning accuracy is also linked to the resolution of the single images. During processing, it was observed that this accuracy is well below 5 cm, which enables sufficient comparability with the TLS dataset. After exporting the control points to IBM, the respective points were identified manually within single images, and the two datasets were matched.

To georeference the TLS model, eleven control points (Riegl 5 cm cylinder, retro targets) were placed within the vicinity of Acceso 1 and measured using an RTK GNSS system. An initial geographic localization of the single scan positions was gained by an onboard GNSS antenna atop the scanner. During the processing of the TLS data, in RiscanPro 2.14.1, georeferencing was based on control points and automated extraction of reference planes for the geometric alignment of single scan positions. The final accuracy of the absolute positioning of the model thus depends on the accuracy and precision of the given geodetic survey. The quality and density of the collected data allow for a crisp rendering of individual stones within La Fortaleza. These data secure calculating the impact of the 2022 collapse and provide an essential reference for its future reconstruction.

The outline of the collapsed area was marked in 3D and the point clouds were reduced to the surfaces enclosing the collapsed volume. The resulting point clouds – namely TLS data from 2019 and the post-collapse IBM data from 2022 at a resolution of 5 cm - were exported to Geomagic Wrap 2021, to render and calculate the volume of the collapse. Both point clouds were merged and triangulated to create a solid mesh according to the processing routines of the software. Merged point clouds were first resampled to an overall 5 cm resolution and noise reduction was applied. After triangulation, the surface of the volume was smoothed to remove spikes and further noise. Finally, the size of the enclosed volume was calculated. Keeping in mind an overall positioning error of approximately 5 cm, one might suggest an average error of the volume estimation of roughly 5%.

4. Results and discussion

Based on the above-described methodology and the methods used in this interdisciplinary study, we have obtained several useful results that clarify not only the current state but also the past of La Fortaleza.

4.1. Background data, ground-truthing, and stratigraphy

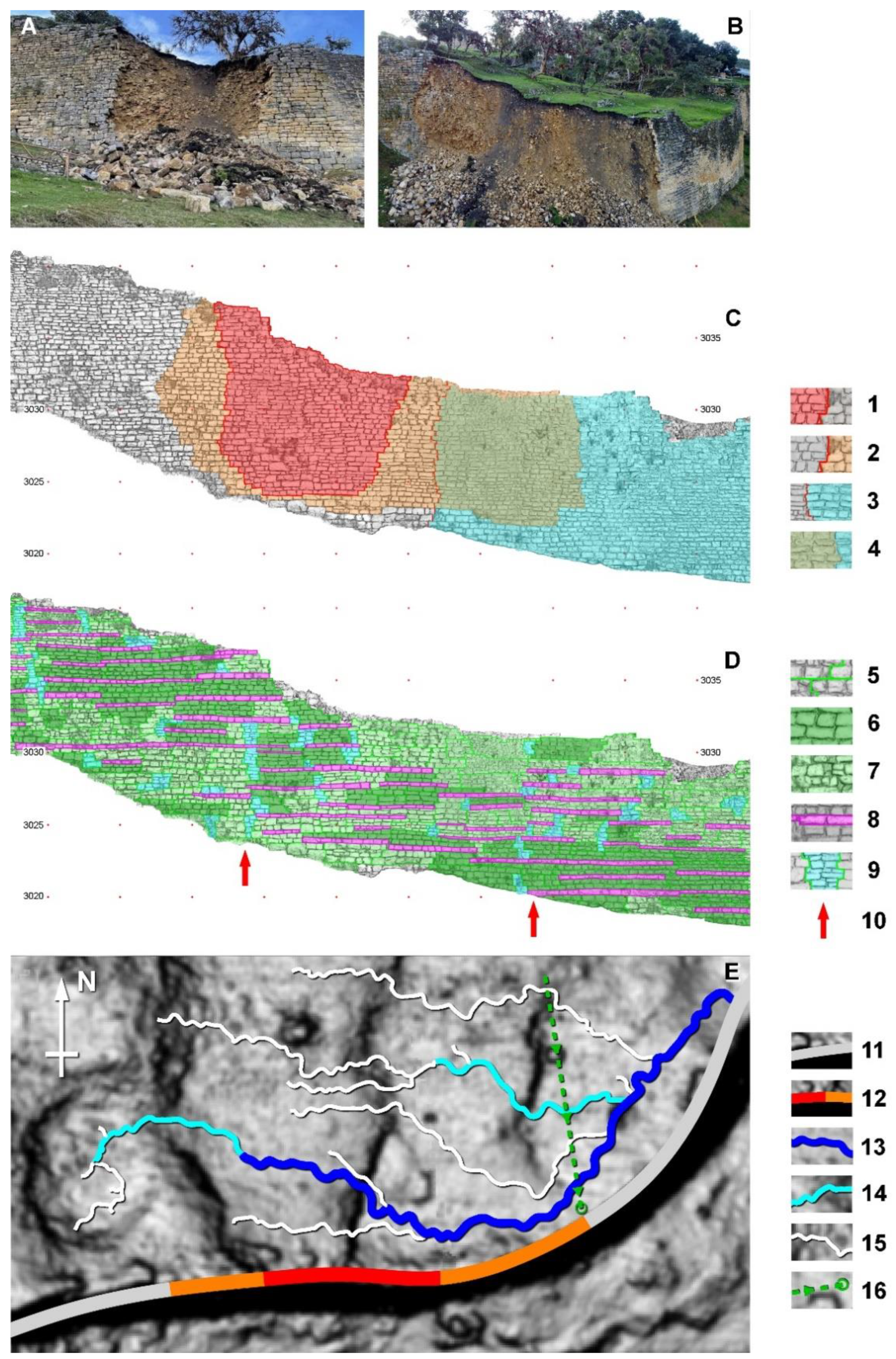

Our review of background information and the ground-truthing of features detected in our remote sensing surveys reveal ongoing stability problems at La Fortaleza, reported since the late 19

th century. We have begun to document the long history of collapses on the perimeter wall [

73]. Obviously, this history is very incomplete, and more populated for the past 100 years. Nevertheless, we have evidence, which will be discussed in detail on section 4.5.3, of a massive pre-Hispanic collapse, involving an area of at least 1750 m

2 on the eastern half of the Southern Sector of La Fortaleza (

Figure 24 B). Photographs published in the reports of various explorers and visitors [

14,

32,

40,

64,

69,

71] reveal that, between 1910 and 1933, a large collapse occurred on the east perimeter wall of the Southern Sector, just north of Acceso 1 (

Figure 24 D). The above-mentioned 2013 collapse affected the eastern perimeter wall north of Acceso 1 (

Figure 24 E). Finally, the April 2022 collapse (

Figure 24 A), which occurred during an exceptional period of precipitation [

27].

This fragmented history of collapses at La Fortaleza reveals the fragile state of the perimeter wall, and indicates that its structural instabilities long predate the 2022 crisis, affecting mostly the southeastern quarter, despite decades of conservation efforts. One important reason for this is the shape of the underlying limestone bedrock: it has been characterized by inclinations or dips towards the east (

Figure 25) [

27,

72,

82] and south (

Figure 21), which Mori modeled for this research processing seismic refraction data. The combination of these two dips in the underlying limestone, the low permeability of this type of rock, and the high rates of rainfall infiltration of the layers above [

84], create geotechnical conditions that strongly influence the geomorphological processes and groundwater circulation at La Fortaleza, favoring a trend for the preferential distribution of sub-surface water towards its southeast quadrant. To this characterization one must add topographical conditions resulting in surface rainwater flowing mainly towards the eastern perimeter walls.

4.2. The problem of deforestation at La Fortaleza

Background research reveals two at least partially successful initiatives to clear-cut Kuelap’s trees and shrubs during the late 19

th century, and a successful clear-cut during the mid-20

th century. Satellite image research at La Fortaleza (

Figure 14) has permitted the documentation of a significant change in its forestation between 2005 and 2022. As shown by the comparison in

Figure 26, the area covered with tall vegetation has decreased by approximately 30%. Whereas the management of heritage sites must seek a compromise between protecting the built heritage and preserving its environmental context [

110], the change observed may have well affected the permeability and absorptivity of the ground.

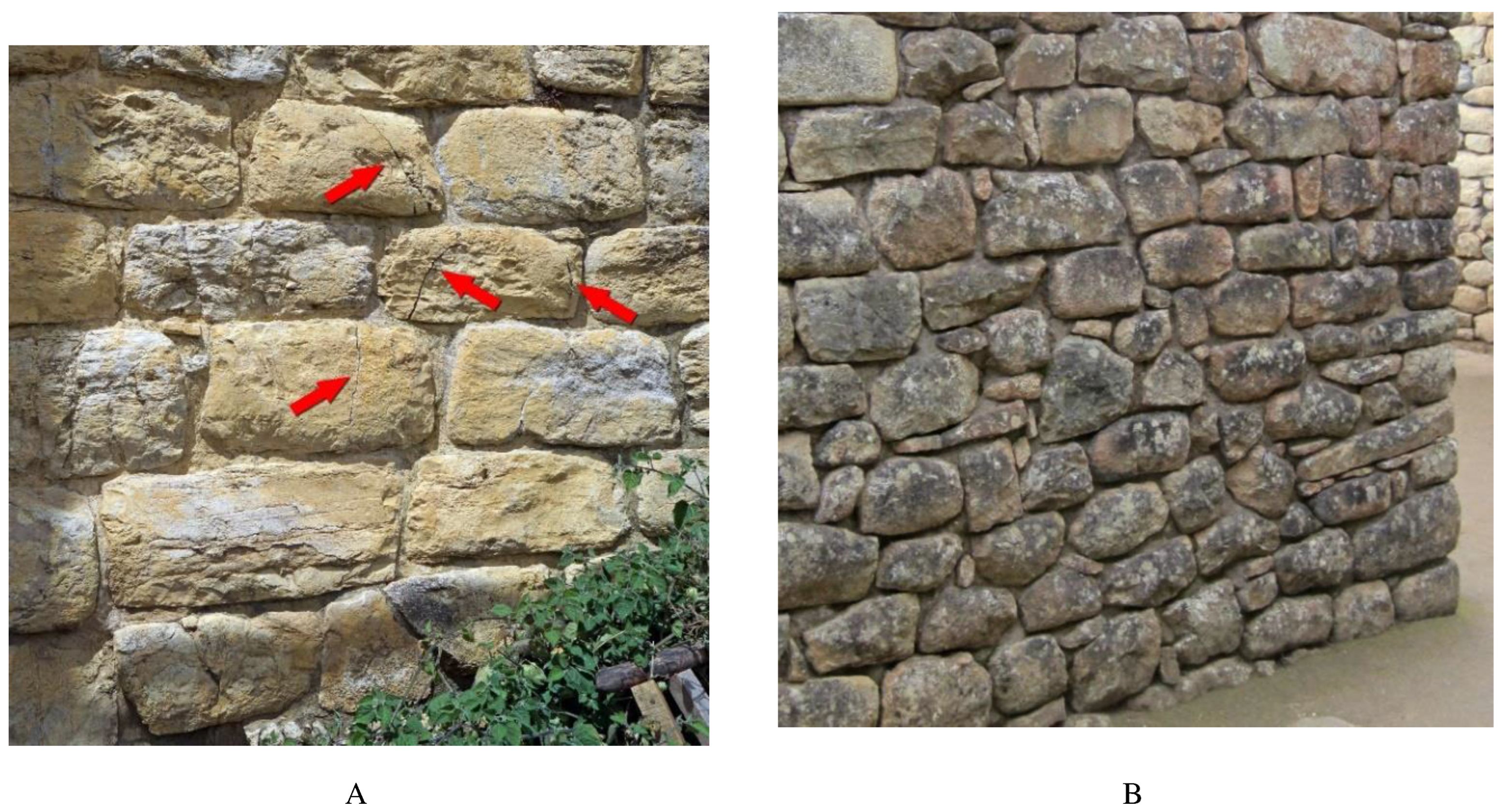

A site’s guidelines for the protection of the built heritage and its natural environment may conflict, depending on the priorities adopted. Limiting our considerations to the protection of built heritage only, a distinction should be made between the vegetation growing on walls and that growing in open spaces between them. Roots penetrating and expanding cracks in the walls accelerate their destruction. This is particularly important in climate zones where the temperatures can drop below zero, as in La Fortaleza, freezing the water accumulated in such cracks and, consequently, weakening the structure of the walls. On the other hand, every conservation practitioner can cite examples when growing root systems integrate with wall masonry, and become an important force that can stabilize a wall. This applies particularly to walls laid on earth or clay mortar, or dry masonry constructed without any mortar. Therefore, it is even recommended that:

“No attempt should be made to remove woody root systems from within the masonry of the monument until the plants have died and a decision can be taken on the best way of dealing with them. In some cases, it may be less damaging to leave the dead root systems within the walls than to dig them out.” [

110] (p. 45).

Thus, while vegetation growth on the walls should generally be prevented, in the case of large trees already firmly rooted in the wall structure, a thorough analysis of the potential effects of their removal is recommended. Such analysis should also include the chemical interaction between the vegetation and the building materials. This applies in particular to sedimentary rocks (mainly sandstones and limestones), such as those found in La Fortaleza [

2,

111].

The problem is equally complicated for trees growing in the open spaces between the walls. Much depends on the soil conditions, especially structure and compaction, and periodic variability of moisture, but mostly on the individual properties of each tree species. It is generally thought that trees, especially the configuration of their root systems, can accelerate the rate of rainwater infiltration into the ground [

112]. However, depending on the characteristics of individual species, they can reduce the depth of rainwater penetration. Much depends on the form of the root system (tangled, spreading, or heart-shaped) and the structure of the root matter (coriaceous and compact or spongy).