Submitted:

02 January 2024

Posted:

04 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Factors contributing in atypical presentations

2.1. Atypical epidemiological context

- Environmental factors

2.1.1. Fungal factors

2.1.2. Host factors

- Trauma

- Underlying diseases

- Iatrogenic factors

- Misuse of treatment

- Indigenous drugs [5]

- Medical drugs

- Corticosteroids

- Deferoxamine

- Antithymocyte globulin

- Immunosuppressive drugs

- Chemotherapy

- Medical procedures

- Bandage/gauze

- Ventilators

- Catheters

- Injection

- organ transplantation

3. Atypical context of infection

4. Atypical clinical features

- -

- Psoriasis-like

- -

- Atopic-like

- -

- Eczema-like

- -

- -

- Acne-like

- -

- Lupus Erythematosus like

- -

- Sweet’s syndrome-like

- -

- Ichtyosis-like

- -

- Keloid-like

- -

- Leproy-like

- -

- Rosea-like

| Description | S/Age | Localization | Fungi | Country | Reference |

| psoriasis-like | - | Body Palms Flexures |

T. rubrum T.mentagrophytes M.gypseum |

India | [105] |

| Trunk, groin, buttocks | T.rubrum | India | [103] | ||

| Lower extremities | T.rubrum | USA | [104] | ||

| M/68 | - | - | Slovenia | [117] | |

| Legs | M. canis | Serbia | [58] | ||

| Body All Nails |

T.rubrum | Switzerland | [78] | ||

| Trunk, lower extremities, toenails | T. rubrum | New Zealand | [118] | ||

| Inverse psoriasis-like | Intertrigous areas | Candida sp | India | [119] | |

| Eczema-like | - |

T.mentagrophytes T.rubrum |

Korea | [79] | |

| Face | T.rubrum | India | [109] | ||

| M/36 | Arms Inguinal region |

Trichophyton eboreum | Switzerland | [120] | |

| F/64 | Hand | Trichosporon asahii | Japan | [101,121] | |

| Seborrheic dermatitis –like | - | Face Scalp |

T. rubrum T.mentagrophytes T.tonsurans M.gypseum |

India | [105] |

| M/77 | Scalp Nails |

T. rubrum | China | [111] | |

| Face Neck |

India | [5] | |||

| Erythema-like | Torso | - | Grenada | [68] | |

| lupus erythematosus-like | - | Face | [73,98,99] | ||

| Furoncle-like | - | Body | T. tonsurans | [105] | |

| Acne-like | M/29 | Back | T.rubrum | Algeria | [113] |

| Prurigo-like | - | T. rubrum | India | [105] | |

| Ichthyosis-like | Body | T.menta | India | [105] | |

| Contact dermatitis-like | M/12 | Right eyebrow | T.menta | Chile | [122] |

| Impetigo-like | M/41 | Right forearm | T. tonsurans | Japan | [123] |

| Allergic-like dermatitis | M/31 | Trunk, upper limbs | T. verrucosum | [124] | |

| Cellulite-like | 4 cases | - | USA | [41] | |

| Pityriasis rubra pilaris | M/54 | Trunk, shoulders, upper arms | Malassezia sp | USA | [125] |

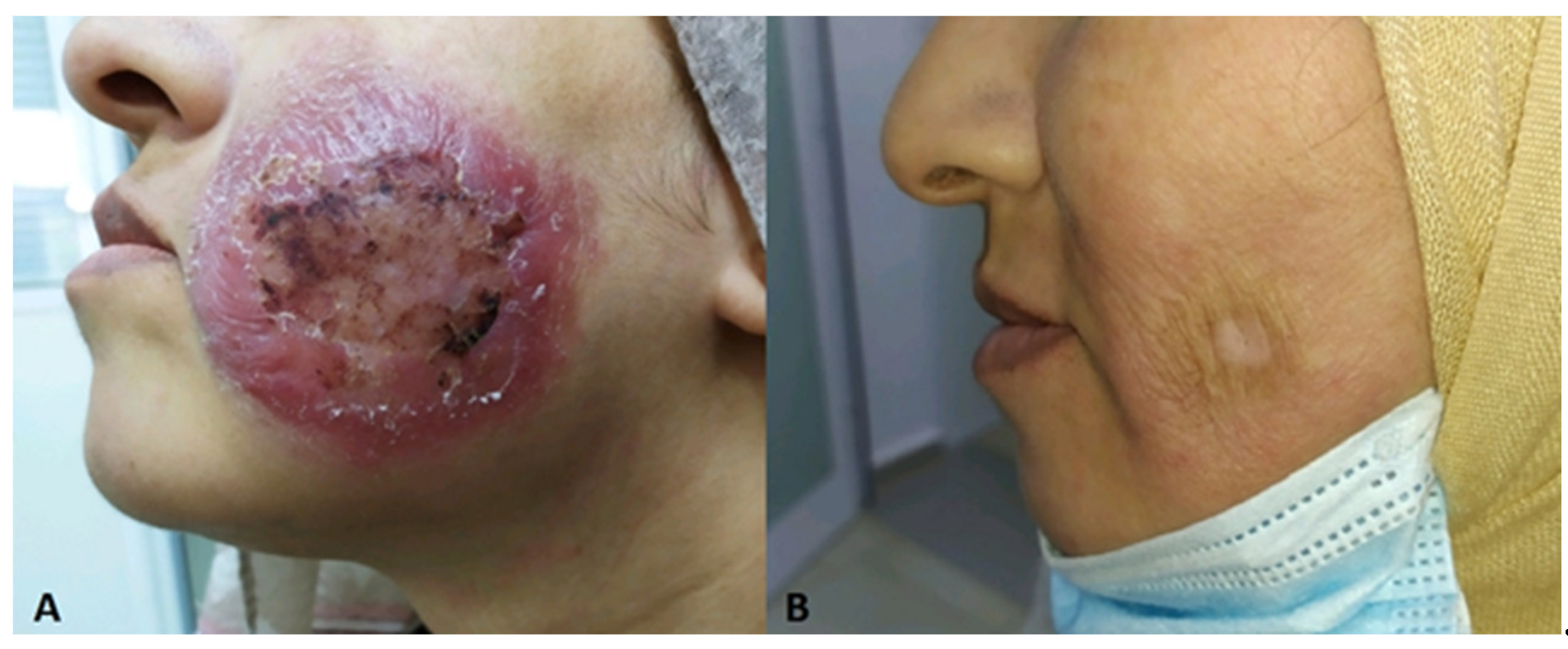

| Myccosis fungoides-like | F/62 | Right chin, Right elbow | - | USA | [1] |

4.1. Atypical localization

- -

- Facial involvement

- -

- Flexual involvement

- -

- Ungueal involvement

- -

- Genital involvement

- -

- no evident localization

| Infection location | Presentation/context | Agent | Reference |

| palms and fingernails | Dischromatic lesions | Malassezia sp | [74] |

| Penis | Malassezia sp | [129] | |

| Axilla | Eryth and papular rash | Malassezia sp | [130] |

| Eyebrows | Tinea of the scalps and eyebrows in diabetic elderly | T.violaceum | [134] |

| Right eyebrow | Erythematous lesion | T.mentagrophytes | [122] |

| Scalp and eyebrow | Tinea of the Scalp and Left eyebrow | M.canis | [135] |

| Eyelid and skin | Upper eyelid swelling for 6 months HIV patient with disseminated lesions |

Rhinosporidium sp | [136] |

| Lip | Dermatophyte presenting as a verrucous nodule of the lip | T.rubrum | [128] |

| Penis | infection of the penis/after wearing penile clothe | M.canis | [90] |

4.2. Atypical progression and extension of the lesions

5. Atypical clinical forms

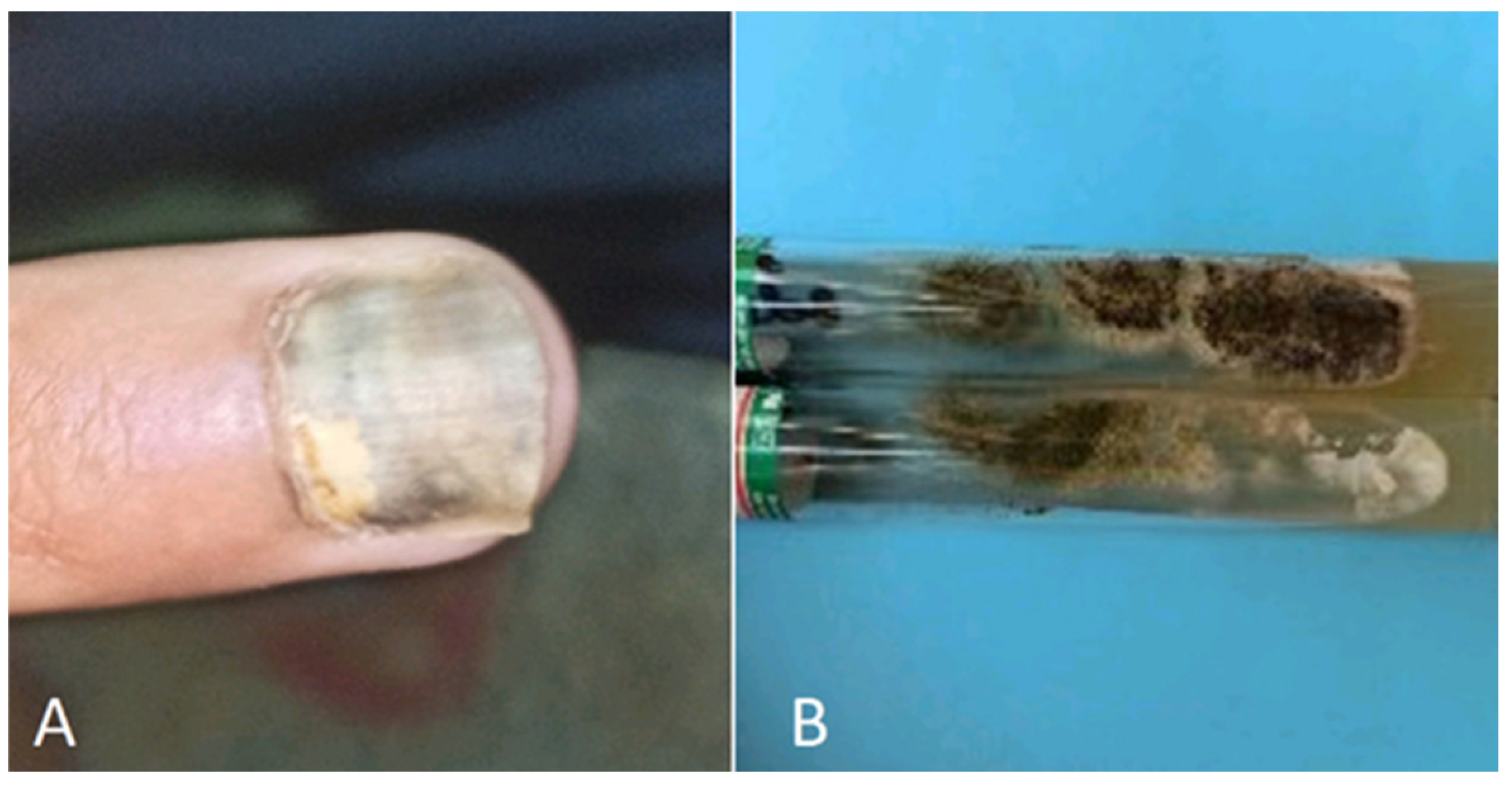

5.1. Atypical onychomycosis

| Clinical presentation | Clinical details | Causative agent | Reference |

| Brown pigmentation | Usually diffuse lesions |

Aspergillus niger Alternaria alternata Scytalidium dimidiatum |

[145,149] |

| Longitudinal melanonychia | Distal lesions |

Trichophyton rubrum Candida humicola Candida albicans Candida parapsilosis Scytalidium dimidiatum Alternaris sp Exophiala sp Aspergillus niger |

[89,145,153] |

| Distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis |

Alternaria alternate Scytalidium sp |

[154] | |

| Black pigmentation | Superficial coloration Periungual inflammation Proximal nail |

Aspergillus niger | [146] |

| Onychodystrophy | Nail discoloration | [149] | |

| Onycholysis | greenish-black discolorations | Candida parapsilosis | [155] |

| Subungual onychomycosis | mimicking a glomus tumor |

Aspergillus niger | [150] |

| Onychodystrophy | All fingernails and toenails involved | Cladosporium sp | [7] |

5.2. Atypical hair mycosis

- Piedra

5.3. Atypical skin mycosis

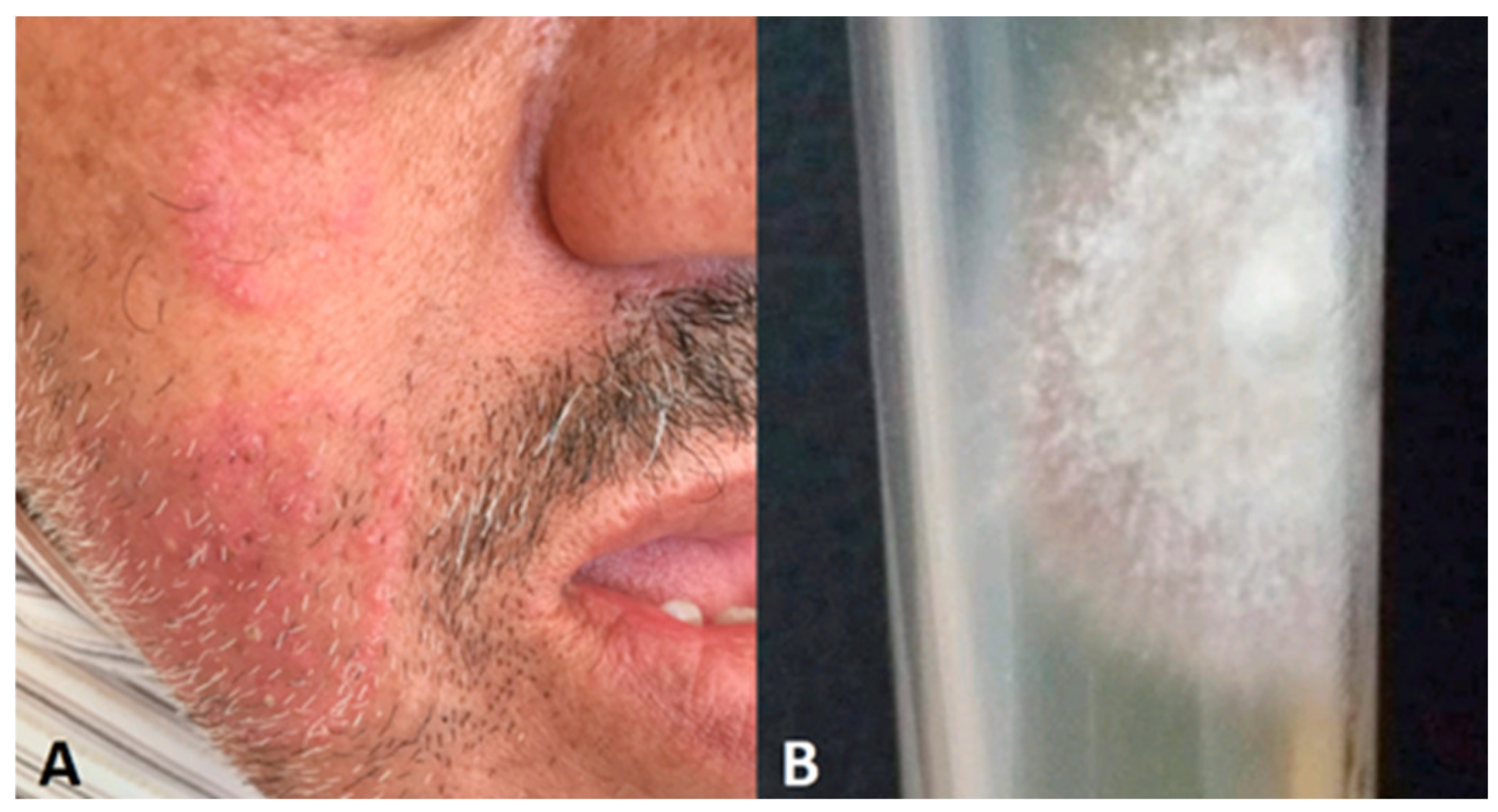

5.3.1. Atypical tinea faciei

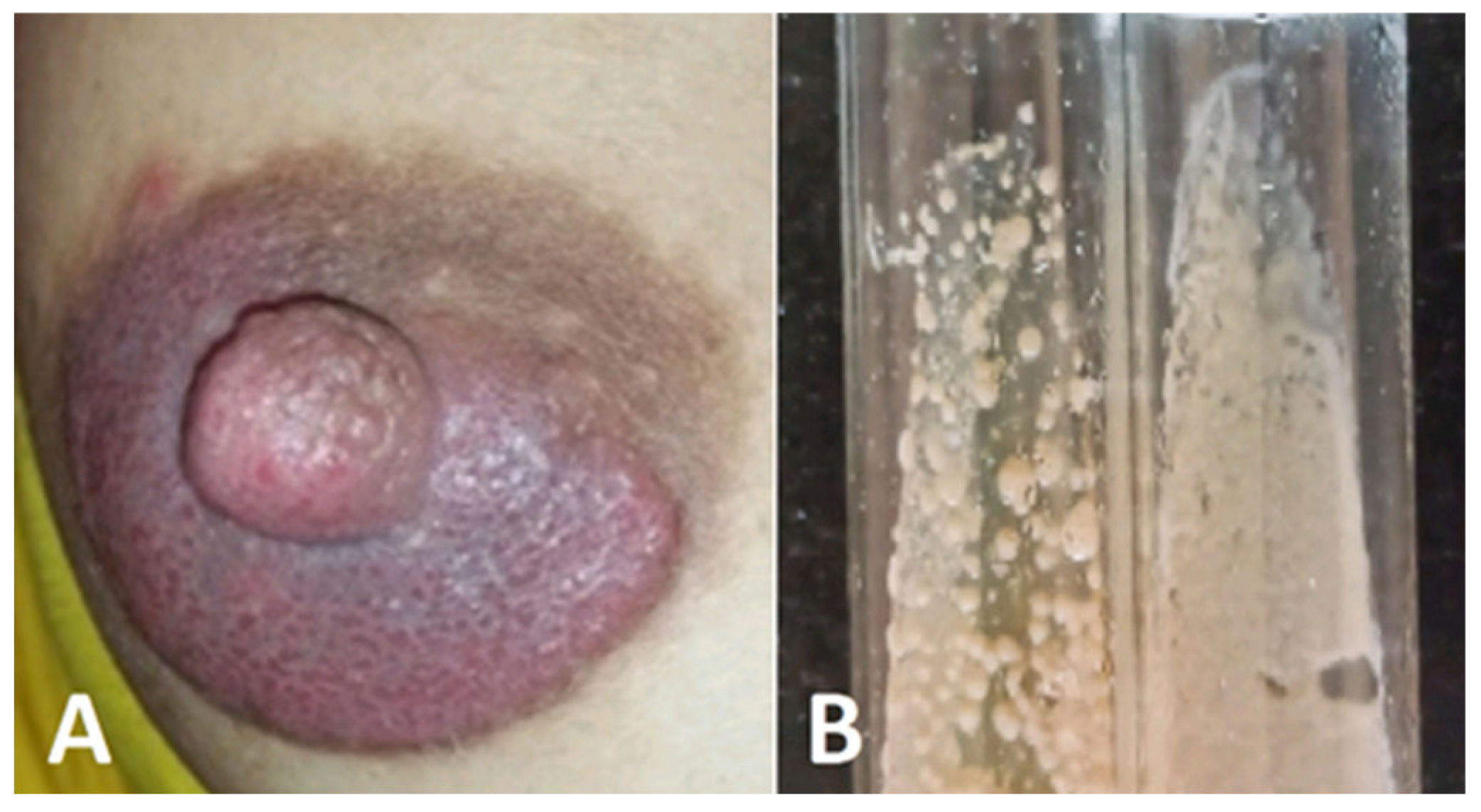

5.3.2. Atypical breast localization (Tinea mammae)

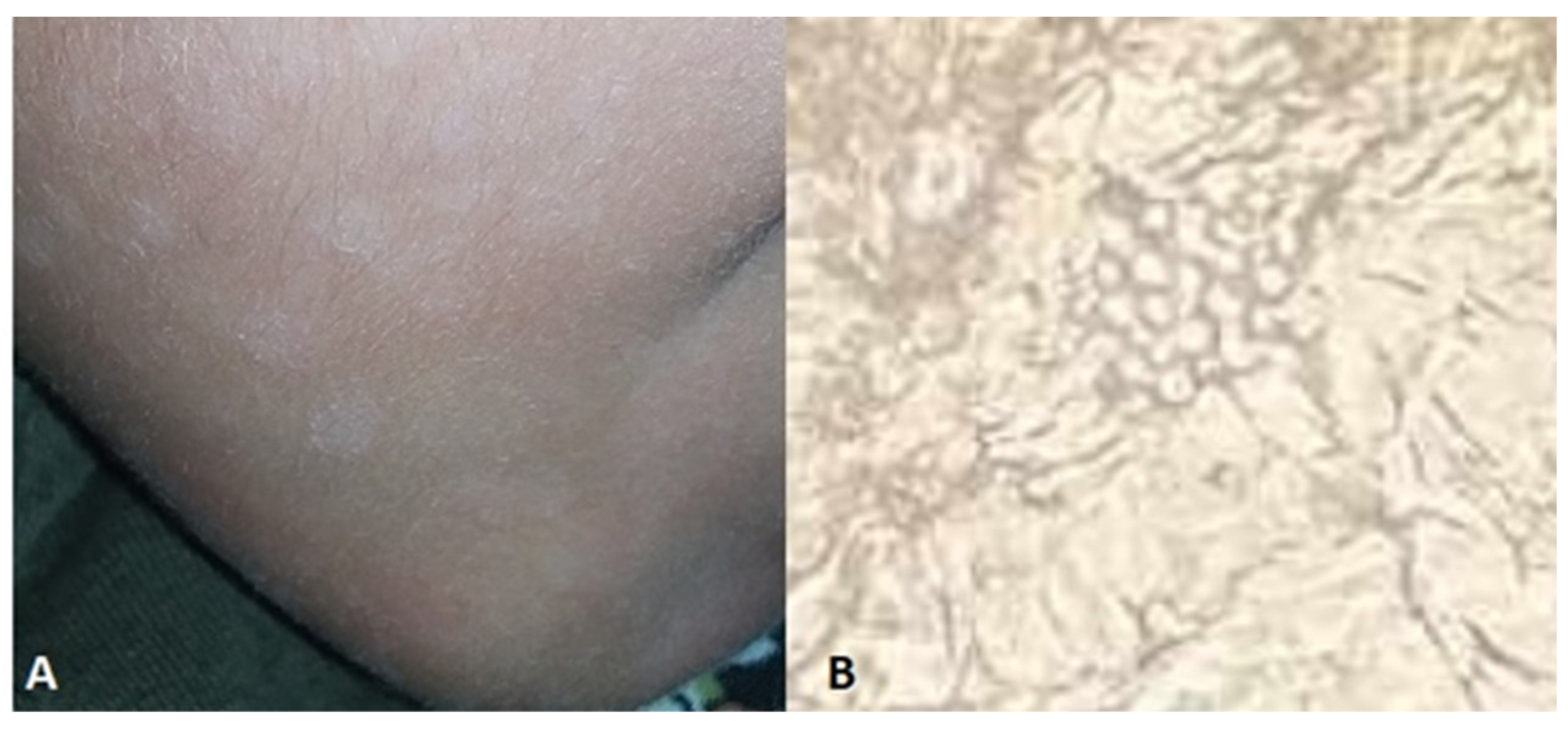

5.3.3. Atypical tinea mannum, and tinea pedis

5.3.4. Atypical tinea corporis

5.3.5. Tinea recidivans

6. Atypical type of lesions

6.1. Lesions configuration

6.1.1. Annular lesions

6.1.2. Nummular lesions

6.2. Lesions color

6.2.1. Erythematous lesions

- -

- Erythematous skin macules on arms and groin areas: This can be caused by Trichophyton species,

- -

- Erythema annulare on the trunk and upper limbs: This can be caused by Trichophyton verrucosum in adult males [124].

- -

- Multiple erythema annulare with slightly scaly plaques on the torso: This presentation can be associated with HIV infection, as seen in a woman diagnosed with the condition [68].

- -

- Erythema multiforme: This can be attributed to Microsporum canis dermatophytosis, as described by Alteras et al. [95].

6.2.2. Dyschromic lesions

6.2.3. Black lesions

6.3. Lesions morphology

6.3.1. Urticaria

6.3.2. Purpuric lesions

6.3.3. Papular lesions

6.3.4. Plaques

6.3.5. Vesicular/Bullous lesions

6.3.6. Abscesses

6.3.7. Nodular

- Majocchi’s granuloma

6.3.8. Ulcerative lesions

6.3.9. Tumoral lesions

7. Conclusion

References

- Babakoohi S, McCall CM. Dermatophytosis Incognito Mimicking Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma. Cureus. 2022 Jun 10;14(6):e25809. [CrossRef]

- Abraham AG, Kulp-Shorten CL, Callen JP. Remember to consider dermatophyte infection when dealing with recalcitrant dermatoses. South Med J. 1998 Apr;91(4):349-53. [CrossRef]

- Vest BE, Kraulan K. Malassezia furfur. StatPearls, May 22, 2023.

- Narang T, Dogra S, Kaur I. Co-localization of Pityriasis versicolor and BT Hansen's disease. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 2005 Sep;73(3):206-7.

- Dogra S, Narang T. Emerging atypical and unusual presentations of dermatophytosis in India. Clin Dermatol Rev 2017;1:S12-8. [CrossRef]

- Trčko K, Plaznik J, Miljković J. Mycobacterium marinum hand infection masquerading as tinea manuum: a case report and literature review. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2021 Jun;30(2):91-93. [CrossRef]

- Nikitha S, Kondraganti N, Kandi V (2022) Total Dystrophic Onychomycosis of All the Nails Caused by Non-dermatophyte Fungal Species: A Case Report. Cureus 14(9): e29765.

- Turra N, Navarrete J, Magliano J, Bazzano C. Follicular tinea faciei incognito: the perfect simulator. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94(3):372-4. [CrossRef]

- Gupta AK. Uncommon localization or presentation of tinea infection. JEADV (2001) 15, 7–8. [CrossRef]

- Szlávicz E, Németh C, Szepes É, Gyömörei C, Gyulai R, Lengyel Z. Congenital ichthyosis associated with Trichophyton rubrum tinea, imitating drug hypersensitivity reaction. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2020 ;29:15-17. [CrossRef]

- Gnat S, Lagowski D, Nowakiewicz A. Major challenges and perspectives in the diagnostics and treatment of dermatophyte infections. Journal of Applied Microbiology 129. [CrossRef]

- Ahasan HN, Noor N. Fungal infection: a recent concern for physician. BJM Vol. 33 No. [CrossRef]

- Viera MH, Costales SM, Regalado J, Alonso-Llamazares J. Inflammatory Tinea Faciei Mimicking Sweet's Syndrome. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104(1):75–76. [CrossRef]

- Nicola A, Laura A, Natalia A, Monica P. A 20-year survey of tineafaciei. Mycoses. 2010;53:504-8. [CrossRef]

- Bishnoi A, Vinay K, Dogra S. Emergence of recalcitrant dermatophytosis in India. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18: 250. [CrossRef]

- Ramonda S, Salerni G, Macia A et al. Micosis superficiales más frecuentes en pacientes infectados por HIV. Rev Argent Dermatol 1994; 75: 34–35.

- Giudice MC, Szeszs MW, Scarpini RL et al. Clinical and epidemiological study in an AIDS patient with Microsporum gypseum infection. Rev Iberoam Micol 1997; 14: 184–187.

- Tsang P, Hopkins T, Jimenez-Lucho V. Deep dermatophytosis caused by Trichophyton rubrum in a patient with AIDS. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996; 34: 1090–1091. [CrossRef]

- Hryncewicz-Gwóźdź A, Beck-Jendroschek V, Brasch J, Kalinowska K, Jagielski T. Tinea capitis and tinea corporis with a severe inflammatory response due to Trichophyton tonsurans. Acta Dermato-Venereologica, 91 (2011), pp. [CrossRef]

- Ouchi TNagao K, Otuka T, Inazumi T. Trichophyton tonsurans infection manifesting as multiple concentric annular erythema. J Dermatol. 2005 Jul;32(7):565-8. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki T, Sato T, Horikawa H, Kasuya A, Yaguchi T. A Case of Tinea Pseudoimbricata Due to Trichophyton tonsurans Induced by Topical Steroid Application. Med Mycol J. 2021;62(4):67-70. [CrossRef]

- Garrido PM, Ferreira J, Filipe P. Disseminated tinea pseudoimbricata as the early warning sign of adult T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022 Feb;47(2):410-412. [CrossRef]

- Gorani A, Schiera A, Oriani A. Case report. Rosacea-like tinea incognito. Mycoses 2002;45:135-7.

- Chowdhary A, Singh A, Kaur A, Khurana A (2022) The emergence and worldwide spread of the species Trichophyton indotineae causing difficult-to-treat dermatophytosis: A new challenge in the management of dermatophytosis. PLoS Pathog 18(9): e1010795. [CrossRef]

- Hainer BL. Dermatophytes infections. American Family Physician 2003, 67(1):101-108.

- Noble SL, Forbes RC, Stamm PL. Am Fam Physician. Diagnosis and Management of Common Tinea Infections. 1998;58(1):163-174.

- Turkal N.W., Baumgardner D.J. Candida parapsilosis infection in a rose thorn wound. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1995;8(6):484–485.

- Saunders CW, Scheynius A, Heitman J (2012) Malassezia Fungi Are Specialized to Live on Skin and Associated with Dandruff, Eczema, and Other Skin Diseases. PLOS Pathogens 8(6): e1002701. [CrossRef]

- Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ Unusual Fungal and Pseudofungal Infections of Humans. JOURNAL OF CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY, Apr. 2005, p. 1495–1504. [CrossRef]

- McBride JA, Sterkel AK, Matkovic E, Broman AT, Gibbons-Burgener SN, Gauthier GM. Clinical Manifestations and Outcomes in Immunocompetent and Immunocompromised Patients With Blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 ;72(9):1594-1602. [CrossRef]

- Salci TP, Salci MA, Marcon SS, Salineiro PHB, Svidzinski TIE, 2011. Trichophyton tonsurans in a family microepidemic. An Bras Dermatol 86: 1003–1006. [CrossRef]

- Xiujiao Xia, Huilin Zhi, Zehu Liu, Hong Shen. Adult kerion caused by Trichophyton rubrum in a vegetarian woman with onychomycosis. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cuétara MS, Palacio A, Pereiro M, Noriega AR. Prevalence of undetected tinea capitis in a prospective school survey in Madrid: emergence of new causative fungi. Br J Dermatol 1998; 138: 658–660. [CrossRef]

- Dogra S, Uprety S. The menace of chronic and recurrent dermatophytosis in India: Is the problemdeeper than we perceive? Indian Dermatol Online J 2016;7:73-6. [CrossRef]

- AK, Mahajan R. Management of tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea pedis: A comprehensive review Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:77–86. [CrossRef]

- Gilaberte Y, Rezusta A, Coscojuela C. Tinea capitis in a newborn infected by Microsporum audouinii in Spain. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003 Mar;17(2):239-40. [CrossRef]

- Offidani A, Simonchini C, Arzeni D et al. Tinea capitis due to Microsporum gypseum in an adult. Mycoses 1998; 41: 239–241. [CrossRef]

- Dell’Antonia M, Mugheddu C, Ala L, Lai D, Pilloni L, Ferreli C, Atzori L. Dermoscopy of tinea incognito. Mycopathologia. 2023 Aug;188(4):417-418. [CrossRef]

- Geary RJ, Lucky AW. Tinea pedis in children presenting as unilateral inflammatory lesions of the sole. Pediatr Dermatol 1999; 16: 255–258. [CrossRef]

- Gupta AK, Sibbald RG, Lynde CW et al. Onychomycosis in children: prevalence and treatment strategies. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997; 36: 395–402. [CrossRef]

- Sweeney SM. Inflammatory tinea pedis/manuum masquerading as bacterial cellulitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 156 (2002), pp. 1149-1152. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho VO, Vicente VA, Werner B. Et.al. Onychomycosis by Fusarium oxysporum probably acquired in utero. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2014;6:58–61. [CrossRef]

- Tahir, C.; Garbati, M.; Nggada, H.A.; Terna Yawe, E.H.; Auwal, A.M. Primary Cutaneous Aspergillosis in an Immunocompetent Patient. J. Surg. Tech. Case Rep. 2011, 3. [CrossRef]

- Yassine M, Haiet AH. Self-injury in schizophrenia as predisposing factor for otomycosis. Medl Mycol Case Rep. 2018 May 3;21:52-53. [CrossRef]

- Merad Y, Derrar H, Belmokhtar Z, Belkacemi M. Aspergillus genus and its various human superficial and cutaneous features. Pathogen. 2021 May 23;10(6):643. [CrossRef]

- Anh-Tram, Q. Infection of burn wound by Aspergillus fumigatus with gross appearance of fungal colonies. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2019, 24, 30–32. [CrossRef]

- Ozer, B.; Kalaci, A.; Duran, N.; Dogramaci, Y.; Yanat, A.N. Cutaneous infection caused by Aspergillus terreus. J. Med. Microbiol. 2009, 58, 968–970. [CrossRef]

- Vitrat-Hincky, V.; Lebeau, B.; Bozonnet, E.; Falcon, D.; Pradel, P.; Faure, O.; Aubert, A.; Piolat, C.; Grillot, R.; Pelloux, H. Severe filamentous fungal infections after widespread tissue damage due to traumatic injury: Six cases and review of literature. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 41, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, M.D.D.S.B.; Leitão, V.M.S.; Neto, M.A.C.D.S.; Maciel, L.B.; Filho, W.E.M.; Viana, G.M.D.C.; Bezerra, G.F.D.B.; Da Silva, M.A.C.N. Eco-epidemiologic study of emerging fungi related to the work of babacu coconut breakers in the State of Maranhao, Brazil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2014, 47, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panke, T.W.; McManus, A.T.J.; McLeod, C.G.J. “Fruiting bodies” of Aspergillus on thee skin of a burned patient. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1978, 69, 188–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubert JN, Callen JP. Recalcitrant tinea corporis as the presenting manifestation of patch-stage mycosis fungoides. Cutis. 2003 Jan;71(1):59-61.

- Hay RJ, Baran R, Moore MK, et al. Candida onychomycosis--an evaluation of the role of Candida species in nail disease. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118(1):47–58. [CrossRef]

- Jones HE, Reinhardt JH, Rinaldi MG. Acquired immunity to dermatophytes. Arch Dermatol 1974;109:840-8. [CrossRef]

- Freitas CF, Mulinari-Brenner F, Fontana HR, Gentili AC, Hammerschmidt M. Ichthyosis associated with widespread tinea corporis: report of three cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013 Jul-Aug;88(4):627-30. [CrossRef]

- Thammahong A, Kiatsurayanon C, Edwards SW, Rerknimitr P, Chiewchengchol D. The clinical significance of fungi in atopic dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2020 Aug;59(8):926-935. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig RJ, Woodfolk JA, Grundmann-Kollmann M, Enzensberger R, Runne U, Platts-Mills TA, et al. Chronic dermatophytosis in lamellar ichthyosis: relevance of a T-helper 2-type immune response to Trichophyton rubrum. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:518-21. [CrossRef]

- Gehrmann U, Rqazi KR, Johansson C, Hultenby K, Karlsson M, et al. (2011) Nanovesicles from Malassezia sympodialis and host exosomes induce cytokine responses– novel mechanisms for host-microbe interactions in atopic eczema. PLoS ONE 6: e21480. [CrossRef]

- Jankovic A, Binic I, Glgorijevic J, Jankovic D, Ljubenovic M, Jancic S. Mimicking each other psoriasis wit tinea incognito. Dermatol Sin. 2011;29(4):149-150. [CrossRef]

- Adel FWM, Bellamkonda V. Atypical Fungal Rash. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019;3(2):166-167.

- Ziemer M, Seyfarth F, Elsner P, Hipler UC. Atypical manifestations of tinea corporis. Mycoses. 2007;50 Suppl 2:31-5. [CrossRef]

- Lanternier F, Cypowyj S, Picard C, et al.: Primary immunodeficiencies underlying fungal infections. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2013, 25:736-747. [CrossRef]

- Lowinger-Seoane M, Torres-Rodriguez JM, MadrenysBrunet N, Aregall-Fuste S, Saballs P. Extensive dermatophytoses caused by Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Microsporum canis in a patient with AIDS. Mycopathologia 1992; 120: 143–6. [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Perez MA, Rodriguez-Pichardo A, Camacho F, Rios JJ. Extensive and deep dermatophytosis caused by Trichophyton mentagrophytes var. interdigitalis in an HIV-1 positive patient. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2000; 14: 61–63. [CrossRef]

- Durand-Joly I, Alfandari S, Benchikh Z, Rodrigue M, Espinel-Ingroff A, Catteau B, Cordevant C, Camus D, Dei-Cas E, Bauters F, Delhaes L, De Botton S. Successful outcome of disseminated Fusarium infection with skin localization treated with voriconazole and amphotericin B-lipid complex in a patient with acute leukemia. J Clin Microbiol. 2003 Oct;41(10):4898-900. [CrossRef]

- Aly, R. & Berger, T. Common superficial fungal infections in patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:S128–S132. [CrossRef]

- Crosby DL, Berger TG, Woosley JT, Resnick SD: Dermatophytosis mimicking Kaposi’s sarcoma in human immunodeficiency virus disease, Dermatologica, 182: 135–137, 1991. [CrossRef]

- Kwon KS, Jang HS, Son HS, Oh CK, Kwon YW, Kim KH, Suh SB. Widespread and invasive Trichophyton rubrum infection mimicking Kaposi's sarcoma in a patient with AIDS. J Dermatol. 2004 Oct;31(10):839-43. [CrossRef]

- Brown J, Carvey M, Beiu C, Hage R. Atypical Tinea Corporis Revealing a Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. Cureus. 2020 Jan 3;12(1):e6551. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Zhu, YZ., Shao, PP. et al. Malignant melanoma mimic fungal infection a case report. Diagn Pathol 17, 33 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Vozza A, Fiorentini E, Cutr FT, Di Girolamo F, Satriano RA. Tinea capitis in two young women: possible favouring role of hair styling products. JEADV (2001) 15, 357–377. [CrossRef]

- Kumar M, Sarma DK, Shubham S, Kumawat M, Verma V, Singh B, Nagpal R, Tiwari RR. Mucormycosis in COVID-19 pandemic: Risk factors and linkages, Current Research in Microbial Sciences, Volume 2,2021,100057. [CrossRef]

- Young M, Keane C, English L. Misdiagnosed dermatophytosis. J Infect. 1982 Mar;4(2):127-9. [CrossRef]

- Daude E, Bartolome B, Pascual M, Fraga J, Garcia-Diez A. Auto involutive Photoexacerbated Tinea Corporis Mimicking a Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus.

- Zawar V, Chuh A (2009). Case report on Malassezia infection of palms and fingernails – speculations on cause for therapeutic failure in pityriasis versicolor., 23(2), 171–172. [CrossRef]

- Bornkessel A, Ziemer M, Yu S, Hipler C, Elsner P. Fulminant papulopustular tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Acta Derm Venereol 2005;85:92. [CrossRef]

- Serarslan G. Pustular psoriasis-like tinea incognito due to Trichophyton rubrum. Mycoses 2007;50:523-4. [CrossRef]

- Van Burik, J.-A.; Colven, R.; Spach, D.H. Cutaneous Aspergillosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1998, 36, 3115–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emilianov V, Feldmeyer L, Yawalkar N, Heidemeyer K. Tinea corporis with Trichophyton rubrum mimicking a flare-up of psoriasis under treatment with IL17-inhibitor Ixekizumab. Case Rep Dermatol. 2021 Jul 9;13(2):347-351. [CrossRef]

- Kim W-J, Kim T-W, Mun J-H et al. Tinea incognito in Korea and it risk factors: nine-year multicenter survey. J Korean Med Sci 2013;28(1):145-151. [CrossRef]

- Merad Y, Derrar H, Tabouri S, Berexi-Reguig F. Candida guilliermondii Onychomycosis Involving Fingernails in a Breast Cancer Patient under Docetaxel Chemotherapy. Case Reports in Oncology 14 (3), 1530-1535, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Torrelo, A.; Hernández-Martín, A.; Scaglione, C.; Madero, L.; Colmenero, I.; Zambrano, A. Primary Cutaneous Aspergillosis in a Leukemic Child. Actas Dermosifilogr. 2007, 98, 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.F.; Wallace, M.R. Cutaneous aspergillosis. Cutis 1997, 59, 138–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr OA, Bong C, Wallis C, Tidman MJ. Primary cutaneous mucormycosis masquerading as pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol. 2004 Jun;150(6):1212-3. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Xin WQ, Liu LT, Chen CF, Wu L, Hu XP. Majocchi's granuloma caused by Trichophyton rubrum after facial injection with hyaluronic acid: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(17): 3853-3858. [CrossRef]

- Langlois, R.P.; Flegel, K.M.; Meakins, J.L.; Morehouse, D.D.; Robson, H.G.; Guttmann, R.D. Cutaneous aspergillosis with fatal dissemination in a renal transplant recipient. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1980, 122, 673–676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Merad Y, Adjmi-Hamoudi H, Tabet-Derraz N. Tinea corporis caused by Microsporum canis in HIV patient treated for neuromeningeal cryptococcis: report of a nosocomial outbreak. Journal of Current Medical Research and Opinion, 1(04),16, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Merad Y, Adjmi-Hamoudi H, Lahmer K, Saadaoui E, Cassaing S, Berry A. Les otomycoses chez les porteurs d’aides auditives : Etude retrospective de 2010 a 2015. Journal deMycologie Medicale, 26(1) :71. [CrossRef]

- Oanţă A, Irimie M. Tinea on a Tattoo. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2016 Aug;24(3):223-4.

- Cohen RR, Shurman J. Fungal melanochya as a solitary black linea vertical nail plate treak: case report and literature review of Candida-associated longitudinal melanonychia Striata. Cureus. 2021 Apr 1;13(4):e14248.

- Bardazzi F, Neri I, Marzaduri S et al. Microsporum canis infection of the penis. Genitourin Med 1997; 73: 579–581. [CrossRef]

- Torres CS, Granoble KG, Pazmiño JEU, Parra Vera HJ. Presentación clínica inusual de tiña corporis en un adolescente causada por Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Centro Dermatológico Dr. Úraga, Vol 4, Nº 2 2022.

- Leung AK, Lam JM, Leong KF, Hon KL. Tinea corporis: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2020 Jul 20;9:2020-5-6. [CrossRef]

- del Boz J, Crespo V, Rivas-Ruiz F, de Troya M. Tinea incognito in children: 54 cases. Mycoses. 2011;54(3):254–258. [CrossRef]

- Verma SB, Panda S, Nenoff P, Singal A, Rudramurthy SM, Uhrlass S, et al. The unprecedented epidemic-like scenario of dermatophytosis in India: I. Epidemiology, risk factors and clinical features. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2021;87:154-75. [CrossRef]

- Alteras I, Feuerman EJ, David M, Segal R. The increasing role of Microsporum canis in the variety of dermatophytic manifestations reported from Israel. Mycopathologia 1986; 95: 105–7. [CrossRef]

- Virgili A, Corazza M, Zampino MR. Atypical features of tinea in newborns. Pediatr Dermatol 1993; 10: 92. [CrossRef]

- Alteras 2 I, Feuerman EJ. Atypical cases of Microsporum canis infection in the adult. Mycopathologia 1981; 74: 181–5.

- Singh R, Bharu K, Ghazali W, Nor M, Kerian K. Tinea faciei mimicking lupus erythematosus. Cutis 1994; 53: 297–8.

- Dauden E, Bartolome B, Pascual M, Fraga J, Garcia-Diez A. Autoinvolutive photoexacerbated tinea corporis mimicking a subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Acta Derm Venereol 2001; 81: 141–2.

- Won-Jeong K, Tae-Wook K, Je-Ho M, et al: Tinea incognito in Korea and its risk factors: nine-year multicenter survey. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:145-51.

- Romano C, Mariatiti E, Gianni C. Tinea incognito in Italy: A 15-year survey. Mycoses 2006;49(5):383-387. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M., Gupta, C., Gujral, G.S. et al. Tinea corporis infection manifestating as retinochoroiditis—an unusual presentation. J Ophthal Inflamm Infect 9, 8 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Zawar V, Kumavat S, Rathi S. Dermatophytosis mimicking psoriasis: A classic presentation of steroid treated tinea. Images In Dermatlogy 113(6):622-623. [CrossRef]

- Dyrholm M, Rubenstain E. Tinea incognito: Majocchi granuloma masquerading as psoriasis. Consultant360, 2017, 57(4).

- Salecha AJ, Sridevi K, Senthil KAL, Sravani G, Rama Murthy DVSB. The menace of tinea incognito: clinic-epidemiological study with microbiological correlation from south India. JPAD Vol. 33, No.4 (2023.

- Yang, Z., Chen, W., Wan, Z. et al. Tinea Capitis by Microsporum canis in an Elderly Female with Extensive Dermatophyte Infection. Mycopathologia 186, 299–305 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Klein PA, Clark RA, Nicol NH. Acute infection with Trichophyton rubrum associated with flares of atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 1999 Mar;63(3):171-2.

- Wilso BB, Deuell B, Mills TA. Atopic dermatitis associated with dermatophyte infection and Trichophyton hypersensitivity. Cutis. 1993 Mar;51(3):191-2.

- Dutta B, Rasul ES, Boro B. Clinico-epidemiological study of tinea incognito with microbiological correlation. India J Dematol Venerol Leprol 2017;83:326-31. [CrossRef]

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste N, Aste N. Dermatophyte infections mimicking other skin diseases: A 154-person case survey of tinea atypica in the district of Cagliari (Italy). Int J Dermatol 2012;51:410-5. [CrossRef]

- Xie W, Chen Y, Liu W, Li X, Liang G. Seborrheic dermatitis-like adult tinea capitis due to Trichophyton rubrum in an elderly man. Medical Mycology Case Reports, 41, 2023, 16-19. [CrossRef]

- Greywal T, Friedlander SF. Dermatophytes and Other Superficial Fungi. Principles and Practices of Pediatric Infectious Diseases (Fifth Edition), 2018, pages 1282-1287.

- Merad Y, Belkacemi M, Derrar H, Belkessem N, Djaroud S. Trichophyton rubrum skin folliculitis in Behcet’s disease. Cureus 13(120,2021. [CrossRef]

- Weksberg F, Fisher BK. Unusual tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton verrucosum. Int J Dermatol 1986; 25: 653–655. [CrossRef]

- Almeida L, Grossman M. Wide spread dermatophyte infections that mimic collagen vascular disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990; 23: 855–857.

- Molina-Leyva A, Perez-Parra S, Garcia-Garcia F. Nodular plaque on the forearm. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(5):839-40.

- Dordevic Betetto L, Zgavec B, Bergant Suhodolcan A. Psoriasis-like tinea incognita: a case report and literature review. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2020 Mar;29(1):43-45.

- Eichhoff G. Tinea incognito Mimicking pustular psoriasis in a patient with psoriasis and cushing syndrome. Cutis. 2021 April;107(04):E30-E32. [CrossRef]

- Surya SP, Dewi KP, Regina R. Cutaneous candidiasis mimicking inverse psoriasis lesion in a type 2diabtes mellitus patient. Dermatol Venereol Indones, Vol.5, Issue 1 (2020).

- Keller MC, French LE, Hofbauer GFL, Bosshard PP. Erythematous skin macules with isolation of Trichophyton eboreum – infection or colonisation?. Mycoses, 2012;56(3):373-375. [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa T, Nakashima K, Takaiwa T, Negayama K. Trichosporon cutaneum (Trichosporon asahii ) infection mimicking hand eczema in a patient with leukemia, Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 2000, 42(5), 929-931. [CrossRef]

- Quinones C, Hasbun P, Gubelin W. Tinea incognito due to Trichophyton mentagrophytes: case report. Medwave 2016 Oct;16(10):e6598. [CrossRef]

- Shimoyama H, Nakashima C, Hase M, Sei Y. A case of tinea corporis due to Trichophyton tonsurans that manifested as impetigo. Med Mycol J, 57E, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Li R, Song Y, Wang A. Generalized tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton verrucosum misdiagnosed as allergic dermatitis and erythema annulare in an adult. Medical Imagery, 2021, 113, 339-340. [CrossRef]

- Darling MJ, Lambiase MC, Young RJ. Tinea versicolor mimicking pityriasis rubra pilaris. Cutis 2005;75:265-7. [CrossRef]

- Dias MF, Quaresma-Santos MV, Bernardes-Filho F, Amorim AG, Schechtman RC, Azulay DR. Update on therapy for superficial mycoses: review article part I. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(5):764-774. [CrossRef]

- Bell SA, Röcken M, Korting HC. Tinea axillaris, a variant of intertriginous tinea, due to non-occupational infection with Trichophyton verrucosum. Mycoses. 1996 Nov-Dec;39(11-12):471-4. [CrossRef]

- Swali R, Ramos-Rojas E, Tyring S. Majocchi granuloma presenting as a verrucous nodule of the lip. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2018 Jan 10;31(1):115-116. [CrossRef]

- Aljabre SH, Sheikh YH. Penile involvement in pityriasis versicolor. Trop Geogr Med. 1994;46(3):184-5.

- Ferry M, Shedlofsky L, Newman A, et al. (January 17, 2020) Tinea InVersicolor: A Rare Distribution of a Common Eruption. Cureus 12(1): e6689. [CrossRef]

- Banu A, Anand M, Eswari L. A rare case of onychomycosis in all 10 fingers of an immunocompetent patient. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4(4):302-304. [CrossRef]

- Varada S, Dabade T, Loo DS. Uncommon presentations of tinea versicolor. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014 Jul 31;4(3):93-6. [CrossRef]

- Aljabre SH. Intertriginous lesions in pityriasis versicolor. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003 Nov;17(6):659-62. [CrossRef]

- Noyan A et al. Tinea of the scalp and eyebrows caused by Trichophyton violaceum in a 62-year-old diabetic woman. JEADV 2001; 15: 88.

- Zeng, J., Shan, B., Guo, L. et al. Tinea of the Scalp and Left Eyebrow Due to Microsporum canis. Mycopathologia (2022). [CrossRef]

- John D, Selvin SST, Irodi A. Disseminated Rhinosporidiosis with comjunctival involvement in an immunocompromissed patient. Middle East Afr J Ophtalmol 2017;24:51-53.

- Metkar A, Joshi A, Vishalakshi V, Miskeen AK, Torsekar RG. Extensive neonatal dermatophytoses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27(2):189–91. [CrossRef]

- King D, Cheever W, Hood A et al. Primary invasive cutaneous Microsporum canis infections in immunocompromised patients. J Clin Microbiol 1996; 34: 460–462. [CrossRef]

- Godse KV, Zawarb V. Chronic urticaria associated with tinea infection and success with antifungal therapy—a report of four cases. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 14S (2010) e364–e365.

- Aspiroz C, Ara M, Varea M, Rezusta A, Rubio C. Isolation of Malassezia globosa and M. sympodialis from patients with pityriasis versicolor in Spain. Mycopathologia. 2002;154:111–7. [CrossRef]

- Mansouri P, Farshi S, Khosravi AR, Naraghi ZS, Chalangari R. Trichophyton Schoenleinii-induced widespread tinea corporis mimicking parapsoriasis. J Mycol Med. 2012 Jun;22(2):201-5. [CrossRef]

- Subramanya SH, Subedi S, Metok Y. et al. Distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis of the finger nail in a neonate: a rare case. BMC Pediatr 19, 168 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Koklu E, Gunes T, Kurtoglu S, et al. Onychomycosis in a premature infant caused by Candida parapsilosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24(2):155–6. [CrossRef]

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury Stone M. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014 Nov 15;90(10):702-10.

- Finch J, Arena R, Baran R. Fungal melanonychia. J Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:830-41.

- Álvarez-Salafranca M, HernándezOstiz S, Salvo Gonzalo S, Ara Martín M. Onicomicosis subungueal proximal por Aspergillus niger: un simulador de melanoma maligno subungueal. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:481---484.

- Y Merad, AA Moulay, H Derrar, M Belkacemi, ad al. Aspergillus flavus onychomycosis in the right fourth fingernail related to phalynx fracture and traumatic inoculation of plants: A vegetable vendor case report. Am. Res. J. Dermatol 2, 1-4, 2020.

- Merad Y, Thorayya L, Belkacemi M, Benlazar F. Tinea unguium, tinea cruris and tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton rubrum in HIV patient: a case report. J Clin Cases Rep 4(4),89-92, 2021.

- Merad Y, Belkacemi, Bassaid A, Derouicha M, Merad Z et al. Onychogryphosis due to Aspergillus niger in a poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus. CMRO 05(09), 1380-1385 (2022).

- Matsuyama Y, Nakamura T, Hagi T, Asanuma K and Sudo A: Subungual onychomycosis due to Aspergillus niger mimicking a glomus tumor: A case report. Biomed Rep 7: 532-534, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Abhinay KPA, Rao SK. Blackening of Nails with Pits – A Combination of Nail Psoriasis and Onychomycosis. Indian J Pediatr 88, 933–934 (2021).

- Noriegaa LF, Di Chiacchioa NG, Figueira de Melloc CDB, Suareza MV, Bet DL, Di Chiacchio N. Prevalence of Onychomycosis among Patients with Transverse Overcurvature of the Nail: Results of a Cross-Sectional Study. Skin Appendage Disord 2020;6:351–354. [CrossRef]

- Singal A, Bisherwal K. Melanonychia: Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020 Jan 13;11(1):1-11. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Herrera EO, Arroyo-Camarena S, Porras-Lopez CF, Arenas R. Onychomycosis due to opportunistic molds. An Bras Dermatol. 2015 May-Jun;90(3):334-7. [CrossRef]

- Ge G, Yang Z, Li D, G. de Hoog S, Shi D. Onychomycosis with greenish-black discolorations and recurrent onycholysis caused by Candida parapsilosis. MedicalMycology Case Reports 24 (2019) 48–50. [CrossRef]

- Bonifaz A, Gomez-Daza F, Paredes V, et al. Tinea versicolor, tinea nigra, white piedra, and black piedra. Clin Dermatol 2010;28:140–145. 79. [CrossRef]

- Xavier MHSB, Torturella DM, et al. Sycosiform tinea barbae caused by Trichophyton rubrum. Dermatology Online Journal 2008, 14 (11): 10.

- Yassine Merad, Hichem Derrar, Mohamed Hadj Habib, Malika Belkacemi, Kheira Talha, Mounia Sekouhi, Zoubir Belmokhtar, Haiet Adjmi-Hamoudi.Trichophyton mentagrophytes tinea faciei in acromegaly patient: Case report. Journal of Clinical and Translational Endocrinology: Case Reports, Volume 19,2021, 100079. [CrossRef]

- Bohmer U, Gottlober P, Korting HC. Tinea mammae mimicking atopic eczema. Mycoses 1998; 41: 345–7. [CrossRef]

- Merad Y, Derrar H, Belkacemi M, Drici A, Belmokhtar Z, Drici AEM. Candida albicans mastitis in breastfeeding woman: an under recognized diagnosis. Cureus 12 (12), 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz M, Kavak A, Yamaner NJ. Bilateral and symmetrical tinea mammae. Dermatol Online J. 2013 Sep 14;19(9):19625. [CrossRef]

- Khanna U, Dhali TK, D'Souza P, Chowdhry S. Majocchi Granuloma of the Breast: A Rare Clinical Entity. CASE AND RESEARCH LETTER, Vol. 107, Issue 7, p 610-612 (September 2016).

- Smith BL, Koestenblatt EK, Weinberg JM. Areolar and periareolar pityriasis versicolor. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004 Nov;18(6):740-1. [CrossRef]

- Sardy M, Korting HC, Ruzicka T, Wolff H. Bilateral areolar and periareolar pityriasis versicolor. J Ger Soc Dermatol. 2010 Aug;8(8):617-8. [CrossRef]

- O'Grady TCSahn EE Investigation of asymptomatic tinea pedis in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24660- 661.

- Al Hasan M, Fitzgerald SM, Saoudian M, Krishnaswamy G. Dermatology for the practicing allergist: Tinea pedis and its complications. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004 Mar 29;2(1):5. [CrossRef]

- Flores CR, Martín Díaz MA, Prats Caelles I, de Lucas Laguna R. Tinea manuum inflamatoria. An Pediatr (Barc) 2004;61(4):344-52 3.

- Balighi K, Lajevardi V, Barzegar M, Sadri M. Extensive tinea corporis with photosensivity. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54(5):57–9.

- Dai, Y., Xia, X. & Shen, H. Multiple abscesses in the lower extremities caused by Trichophyton rubrum. BMC Infect Dis 19, 271 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Heibel HD, Ibad S, Chao Y, Patel KK, Hutto J, Redd LE, Nussenzveig DR, Laborde KH, Cockerell CJ, Shwin K. Scurvy and TineaCorporisSimulatingLeukocytoclasticVasculitis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2021 Dec 1;43(12):e230-e233. [CrossRef]

- Sarojini PA, Dharmaratnam AD, Pavithran K, Gangadharan C. Concentric rings simulating tinea imbricata in secondary syphilis. A case report. Br J Vener Dis. 1980 Oct;56(5):302-3. [CrossRef]

- Hong JS, Lee DW, Suh MK, Ha GY, Jang TJ, Choi JS. Tinea Corporis Caused by Trichophyton verrucosum Mimicking Nummular Dermatitis. J Mycol Infect 2019; 24(1): 32-34. [CrossRef]

- Gupta AK, Bluhm R, Summerbell R. Pityriasis versicolor. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2002;16(1):19-33. [CrossRef]

- Merad Y, Merad S, Belkacemi M, Belmokhtar Z, Merad Z, Metmour D. Extensive Pityriasis Versicolor Lesions in an Immunocompetent Parking Attendant: An Occupational Disorder? CMOR 05(08), 1327-1331 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Rehamnia Y, L Senhadji L, D Matmour D, MA Boumelik MA, Belmokhtar Z, and al. Tinea Versicolor Disguised as Pityriasis Alba: How to Deal with Confusing Skin Hypopigmentation. Journal of Current Medical Research and Opinion 6 (12), 1962-1968, 2023.

- Nakabayashi A, Sei Y, Guillot J. Identification of Malassezia species isolated from patients with seborrhoeic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis versicolor and normal subjects. Medical Mycology. 2000 Oct;38(5):337-41.

- Akaberi AA. Amini SS, Hajihosseini H. An Unusual Form of Tinea Versicolor: A Case Report. Iranian Journal of Dermatology, Vol 12, No 3 (Suppl), Autumn 2009.

- Hall J, Perry VE. Tinea nigra palmaris: differentiation from malignant melanoma or junctional nevi. Cutis 1998;62:45–46. 77.

- Haliasos EC, Kerner M, Jaimes-Lopez N, et al. Dermoscopy for the pediatric dermatologist. Part I: dermoscopy of pediatric infectious and inflammatory skin lesions and hair disorders. Pediatr Dermatol 2013;30:163–171. [CrossRef]

- Mendez J, Sanchez A, Martinez JC. Urticaria associated with dermatophytosis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2002 Nov-Dec;30(6):344-5. [CrossRef]

- Veraldi S, Gorani A, Schmitt E, Gianotti R. Case report. Tinea corporis purpurea. Mycoses 1999; 42: 587–9. [CrossRef]

- Hsu S, LE EH, Khoshevis MR. Differential Diagnosis of Annular Lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(2):289-297.

- Kalkan G, Demirseren DD, Güney CA, Aktaş A. A case of tinea incognito mimicking subcorneal pustular dermatosis. Dermatology Online Journal. 2020, 26(2):13. [CrossRef]

- Terragni L, Marelli MA, Oriani A, Cecca E. Tinea corporis bullosa. Mycoses 1993; 36: 135–7.

- Veraldi S, Scarabelli G, Oriani A, Vigo GP. Tinea corporis bullosa anularis. Dermatology 1996; 192: 349–50. [CrossRef]

- Karakoca Y, Endoğru E, Erdemir AT, Kiremitçi U, Gürel MS, Güçin Z. Generalized Inflammatory Tinea Corporis. J Turk Acad Dermatol 2010; 4 (4): 04402c.

- Barbé J, Clerc G, Bonhomme A. Granulome de Majocchi pubien : une entité clinique de localisation inhabituelle. Annales de Dermatologie et de Vénérologie, Volume 145, Issue 12, Supplement, 2018, S287-S288,. [CrossRef]

- Inaoki M, Nishijima C, Miyake M, Asaka T, Hasegawa Y, Anzawa K, Mochizuki T. Case of dermatophyte abscess caused by Trichophyton rubrum : a case report and review of the literature. Mycoses, Vol. 58, Issue 5, p. 318-3232, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Yonebayashi K, Yasuda E, Sakatani S, Kusakabe H, Kiyokane K. A case of granuloma trichophyticum associated with relapsing polychondritis. Skin Research 1998;40:394-8.

- Matsuzaki Y, Ota K, Sato K, Nara S, Yagushi T, Nakano H, Sawamura D. Deep pseudocystic dermatophytosis caused by Trichophyton rubrum in a patient with myasthenia gravis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2023 May. [CrossRef]

- Colwell AS, Kwaan MR, Orgill DP. Dermatophytic pseudomycetoma of the scalp. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(3):1072-1073. [CrossRef]

- Toussaint F, Sticherling M. Multiple Dermal Abscesses by Trichophyton rubrum in an Immunocompromised Patient. Frontiers in Medicine, Volume 6 - 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kim SH, Jo IH, Kang J, Joo SY, Choi JH. Dermatophyte abscesses caused by Trichophyton rubrum in a patient without pre-existing superficial dermatophytosis: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 17;16:298. [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger P, Rottman A. Trichophyton species as the Cause of A Diabetic Deep Plantar Foot Abscess: A Case Report. Podiatry Today 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hironaga M, Okazaki N, Saito K, Watanabe S. Trichophyton mentagrophytes granulomas. Unique systemic dissemination to lymph nodes, testes, vertebrae, and brain. Arch Dermatol 1983; 119: 482–90.

- Parmar NV, Asir GJ, Rudramurthy SM. Atypical Presentation of Majocchi's Granuloma in an Immunocompetent Host. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017 Jan 11;96(1):1-2.

- Hironaga M, Okazaki N, Saito K, Watanabe S. Trichophyton mentagrophytes granulomas. Unique systemic dissemination to lymph nodes. Testes, vertebrae, and brain. Arch. Dermatol. 1983, 119,482-490.

- Fukushiro R. Dermatophytes abscess . In: Fukushiro R (ed. Color Atlas of Dermatophytoses. Tokyo: Kanehara Co. 1999:89-95.

- Marconi VC, Kradin R, Marty FM, Hospenthal DR, Kotton CN. Dessiminated dermatophytosis in a patient with hereditary hemochromatosis and hepatic cirrhosis: case report and review of the literature. Medical Mycology, Vol 48, Issue 3, May 2010, p 518-527.

- Zheng, Yy., Li, Y., Chen, My. et al. Majocchi’s granuloma on the forearm caused by Trichophyton tonsurans in an immunocompetent patient. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 19, 39 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Jakob Lillemoen Drivenes, Mette Ramsing, Anette Bygum; Majocchi’s Granuloma – The Great Mimicker: A Case Report. Case Rep Dermatol 21 December 2023; 15 (1): 190–193.

- Toyoki M, Hase M, Hiradawa Y et al. A giant dermatophyte abscess caused by Trichophyton rubrum in an immunocompromised patient. Med. Mycol. J. 58E, E63-E66, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Ribes JA, Vanover-Sams CL, Baker DJ. Zygomycetes in humandisease. ClinicalMicrobiologyReviews, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 236–301, 2000.

- Kyung-Ran K, Hwanhee P, Door-Ri K, Yoonsunn Y, Chiman J, Saanghoon L, So-Young L, Ji-Hye K, Yae-Jean K. Kerion Celsi caused by Trichophyton verrucosum mimicking a hypervascular tumor in a pediatric patient: a case report. Pediatric Infection & Vaccine;118-123,2022.

- Yun, SK., Lee, SK., Park, J. et al. Deeper Dermal Dermatophytosis by Trichophyton rubrum Infection Mimicking Kaposi Sarcoma. Mycopathologia (2022). [CrossRef]

- Tookey P, Gale J, pKazmi A, Ligaj M, Hawthorne M, Jeetle S, Fhogartaigh CN, M. Stodell, Moir G, Khurram M, Harwood C. BI02: Melanized (dematiaceous) fungal infections simulating skin cancer in African organ transplant recipients, British Journal of Dermatology, Volume 185, Issue S1, 1 July 2021, Pages 142–143.

| Localisation | Sex/age | Culture | Underlying disease | Country | References | |

| Lip | F/40 | T. rubrum | - | India | [128] | |

| Hand | F/52 | T.rubrum | Polychodritis | Japan | [189] | |

| Extremities, trunk, face | F/44 | T.rubrum | Myasthenia gravis | Japan | [190] | |

| Leg | M/54 | T.rubrum | None | Japan | [188] | |

| Thigh | F/24 | T.mentagrophytes | None | USA | [82] | |

| Scalp | F/19 | M.canis | None | [192] | ||

| Upper extremities | M/52 | T.rubrum | Immunosuppresive therapy | France | [193] | |

| Malleolus | F /68 | T.rubrum | - | Korea | [194] | |

| Foot | M/39 | Trichophyton sp | Type-2 diabetes | USA | [195] |

| Localisation | Sex/age | Culture | Underlying disease | Country | References | |

| Leg, trunk | M/28 | T. verrucosum | Nephrotic syndrme | Japan | [198] | |

| Groin | M/58 | T.rubrum | Nephrotic syndrome | Japan | [199] | |

| Extremities, truck, face | M/45 | T.rubrum | Haemochromatosis | USA | [200] | |

| Forearm | F/62 | T.tonsurans | - | China | [201] | |

| Breast | F/28 | T.violaceum | India | [162] | ||

| genitoinguinal | M/54 | - | - | Danemark | [202] | |

| Forearm | M/53 | T.rubrum | Spain | [116] | ||

| Buttock | M/73 | T.rubrum | Suppressive drugs | Japan | [203] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).