Submitted:

29 December 2023

Posted:

04 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

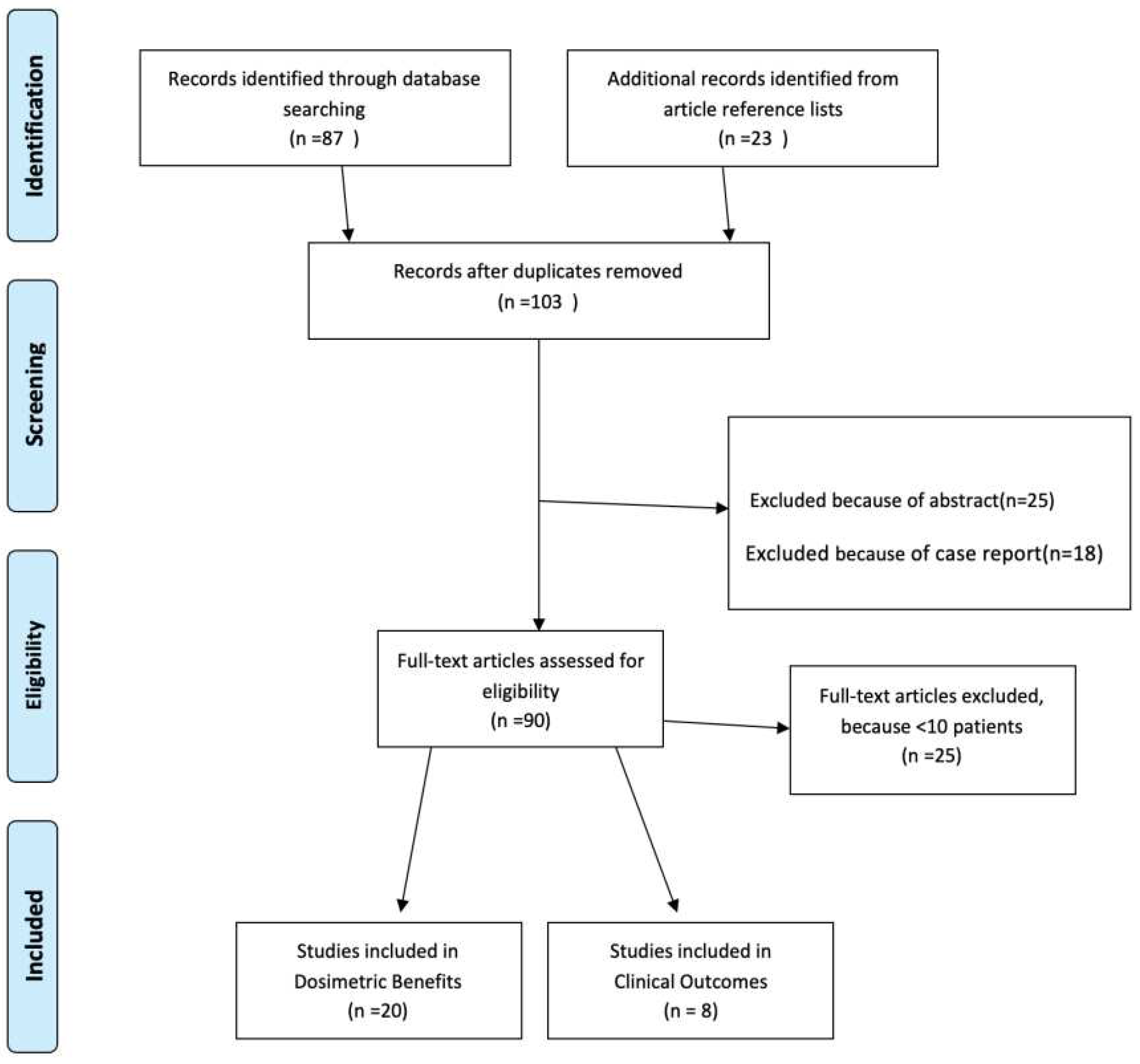

Methods and Materials

- ■

- Report on dosimetric/anatomic changes.

- ■

- studies with ≥10 patients

Results

Radiotherapy Planning

Fractionation

Daily Imaging

- Anatomical Variability: The head and neck region experiences significant anatomical changes, including weight loss, tumor regression, and patient positioning shifts. Daily imaging, often via cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), detects these changes and ensures precise tumor targeting while sparing critical structures.

- Patient Positioning: Accurate patient setup is essential for effective radiation therapy. Daily imaging verifies patient positioning, minimizing the risk of radiation toxicity to normal tissues.

- Dose Escalation: Daily imaging enables safe dose escalation by adapting treatment plans to current anatomy. This can improve local control and overall treatment outcomes.

- Reduced Margins: Smaller treatment margins, made possible by daily imaging, minimize radiation exposure to nearby healthy tissues, which is crucial in the head and neck region where critical structures are close to the tumor.

Dosimetric Considerations

Volume Shrinkage

Dose Improvement to OARs

Replanning Strategies

Quality Assurance (QA)

| REPLANNING STRATEGIES | DOSIMETRIC BENEFITS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (year) | Pts No | TOTAL DOSE (Gy) |

Imaging method | Time of evaluation |

No of Replanning |

Volume Shrinkage | Parotid (Dmean/V26) |

Spinal Cord/Brainstem (Dmax) |

Benefit from ART |

| Zhao (2011) [65] | 33 | 37.5 Gy (20 – 50 Gy) | CT | 1st at 15th (+/-5) fr 2nd at 12th (+/- 4) fr 3rd after 15th fr |

1 | GTVp: - 13.9%; GTVn: - 71.9%; CTV: - 3.5%; | Decreased mean dose (p <0.05) | NR | Decreased PG dose |

| Capelle (2012) [49] | 20 | 66 Gy (54-60 nodes; 66 Gy primary) |

CT | 15TH fr | 1 | Median Volume Loss: PTV60/66 = -16% (0-45%); PTV54 = - 6.8 (-1.2 – 19%); GTV = -28.8% (-1.6 – 60%); CTV60 = - 4.1% (-0.1 – 10%); PG = 17.5% (-1 – 46%) | CohA Adjuvant CRT: PG: Dmean = -1.2 Gy/V26 = -6.3% CohB Definitive CRT: PG: Dmean = -1.2 Gy/V26 = -6.3% |

SC: Dmax = 1.2 Gy | 15/23 Pts improved TV dose coverage |

| Duma (2012) [62] | 11 | 64 postop 70 radical |

MVCT | 16th fr (9th – 21rst) | 1 | NR | PG: no variation of dose | SC: -0.14 Gy | --- |

| Jensen (2012) [63] | 72 15 replanned |

70.4 | Weekly CT | Weekly | 2-4 | NR | CPG: - 11.5% | NR | 8% Improvement of coverage |

| Schwartz (2013) [64] | 22 | 70 | 16th and 22nd Fr |

1-2 | NR | -0.7 Gy | NR | Increase coverage and dose homogeneity |

|

| Bhandari (2014) [21] | 15 | NR | CT | 3rd week of treatm Between 18th and 20th fr |

1 (HP vs AP) | Mean Volume Loss: GTV = -44.32 cc; CTV = 82.2 cc; PTV = -149.83 cc | RPG Dmean= +5.56+/-4.99 Gy (p<0.04); LPG Dmean =+3.28+/-3.32 Gy (p<0.003); | SC Dmax = +1.25+/-2.14 (p=0.04) BS Dmax = +3.88+/-3.22 (p<0.02) |

TV and OARs |

| Lu J (2014) [50] | 12 | 66 to Primary GTV (D95) | CT | 25th fr | 1 (HP vs AP) | Mean Volume Change: PGTV = -16.4 +/- 27.3; PTV1 = +3.8+/-6.3; PTV2 = -8.8+/-12.0 cc; rPG = -24.6+/-11.9; IPG = -35.1+/-20.1 | RPG = -24.6+/-11.9; LPG =-35.1+/-20.1 | SC and BS: 8/12 No-ART Pts exceeded the constraint without replanning |

TV and OARs |

| REPLANNING STRATEGIES | DOSIMETRIC BENEFITS | ||||||||

| Author (year) | Pts No |

TOTAL DOSE (Gy) |

Imaging method | Time of evaluation |

No of Replanning |

Volume Shrinkage |

Parotid benefit (Dmean/V26) |

Spinal Cord/Brainstem (Dmax) |

Benefit from ART |

| Olteanu (2014) [51] | 10 | 70.2 Gy | PET-CT | 10th, 20th and last day of treatm for dose sum | 2 (11th-20th fr and 21st – 30th) | Reduced GTV volumes (18.6-93.3%) after 18th fr | PG: reduced median dose 4.6-7.1% (p>0.05) | OARs: dose-differences from -7.1to 7.1% | TV and OARs |

| Reali (2014) [52] | 10 | 68.4 – 70.2 Gy | CT | Weeks 3, 5, and 7 of treatm |

1 | PTVs mean relative shift = 0.1 cm (not taken in consideration for replan); PG volume decreased mainly for Ipsilateral PG | NR | SC mean relative shift = 0 cm | PGs |

| Castelli (2015) [53] | 15 | 70 Gy | Weekly CT | Weekly | Weekly replanning | CTV70 decreased by a mean value of 31% (ranging 3% to −13%) PG volumes decreased by a mean value of 28.3% (ranging from 0.0 to 63.4% |

PG Dmean: -4.8 Gy (67% Pts) and -3.9 Gy (33% Pts) Median contralateral PG dose-decrease: -2.0 Gy. (from 27.9 to 25.9 Gy) |

NR | PG reduced dose |

| Zhang (2016) [54] | 13 | 70 | Weekly CT | Weekly | 6 weekly replans | Mean Volume Reduction CTV70=24.43% | With standard IMRT: Mean PG overdose of 4.1 Gy vs planned dose. In Replan: PG mean dose -3.1 Gy compared planned dose |

NR | PG Benefit >4 Gy (34% one PG – 15% both PGs) |

| Van Kranen (2016) [55] | 19 | 70 | Daily CBCT | 10th fr | 1 (10th fr or max in 2nd week of treat) | In 5th week: decreased CTVn & CTVnboost <-10% |

Margin reduction and improvement in OAR dose ≈ 1 Gy/mm | NR | PGs: improved D99% with – at least - 3 Gy |

| Dewan (2016) [56] | 30 | GTV= 70 Gy; CTV = 66 Gy; PTV = 60 Gy | Weekly CT | 20th fr | 1 (+ 1 hybrid) |

Shrinkage: GTV: 47.62%; CTV: 43.76%; PTV: 39.69%. IPG: 33.65%; CPG: 31.06% | Mean dose to ipsilateral parotid was significantly reduced with replanning by 26.04+29.14 % (p= 0.001). | SC: Replanning reduced mean Dmax, D2% and D1% by 28.26 + 10.27%, 30.87+ 12.83% and 31.20 + 13.09% respectively as compared to delivered dose (p<0.01) | TV and OARs |

| Deng (2017) [57] |

20 | 66 – 71.6 Gy | CT | 5th and 15th frs | 2 replans + 2 hybrid replans (5th and 15th fr) | Increase in V95; PTVnx: Decreased Vmax and V110 | Left PGs: Dmean = 3.67 Gy; V30 = 3.66 Gy | In ART plans: SC: Dmax decreased by 2.42 Gy; BS: Dmax decreased by 2.42 Gy | TV and OARs |

| Surucu (2017) [19] | 51 | 70.2 Gy | CT and CBCT | After median dose of 37.8 Gy (27 - 48.6) | 1 (in 34/51 pts) | Median TVRR: 35.2% (-18.8 – 79.6%) | IPG Dmean = – 6.2%; CPG Dmean = -2.5%; | SC Dmax = -4.5% BS Dmax = -3.0% |

TV and OARs |

| REPLANNING STRATEGIES | DOSIMETRIC BENEFITS | ||||||||

| Author (year) | Pts No |

TOTAL DOSE (Gy) |

Imaging method |

Time of evaluation |

No of Replanning |

Volume Shrinkage |

Parotid benefit (Dmean/V26) |

Spinal Cord/Brainstem (Dmax) |

Benefit from ART |

| Castelli (2018) [58] | 37 | 70 Gy | Weekly CT | weekly | Weekly replanning | NR | Median contralateral PG dose-decrease: -2.0 Gy. (from 27.9 to 25.9 Gy) | NR | PGs: reduced dose in 89% of Pts; CTV: increased dose in 67% of Pts; Both benefits: in 56% of Pts |

| Aly (2018) [20] | 10 | 70 Gy | CT | Mainly in 10th fr and 15th fr |

Mean 2 (range 0-5) | Volume Reductions: GTVp = 25%; CTVp = 18%; GTVn = 44%; CTVn = 28%; PTV70 = 11%; PTV60 no signific change | PG volume decrease 28% during treatment | NR | Improved coverage of PTV70 and PTV60 |

| Hay (2020) [60] | 20 | 65 Gy | CT and CBCT | At fraction 16th | 1 (19th fr) | NR | NR | SC: 3 Pts exceed max dose without replan | Benefit in OARs |

| Mnejja (2020) [59] | 20 | 69.96 Gy | CT | At dose 38 Gy | 1 (19th fr) | Reduction in TV: 58.56% (GTVnodes); 29.52% (GTVtumor) | NR | NR | Deterioration of Tumor Coverage in no-ART Pts |

| Avkshtol (2023) [61] |

21 | NR | CT and CBCT | Frequency of adapts at the discretion of treat physician | 1-5 Median 13.5th and 19th fr |

NR | IPG: -13.2 (node+ pts) -11.24% (T3/4 disease pts) CPG: - 3.78 (node+ pts) -1.68 (T3/4 disease pts) |

SC Dmax: -9.65 (node+ pts) -9.32 (T3/4 disease pts) BS Dmax: -6.41 (node+ pts) -5.38 (T3/4 disease pts) |

PTV coverage PTV dose homogeneity OARs |

Clinical Considerations

Conclusions

Abbreviations

References

- Poonam, J.; Dutta, S.; Chaturvedi, P.; Nair, S. Head and Neck Cancers in Developing Countries. Cancer of the oral cavity. Ram Maimonides Med J., 2014;5 (2) . [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.;, Miller, K.; Wagle, N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(1):17–48.

- Marur, S.; Forastiere, A. Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Update on Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(3):386 – 96.

- Dhull, K.; Atri, R.; Dhankhar, R.; Chauhan, A.; Kaushal, V. Major Risk Factors in Head and Neck Cancer: A Retrospective Analysis of 12-Year Experiences. World J Oncol. 2018 Jun; 9(3): 80–84. [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Ervik, M.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC Cancer Base No. 11 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer Available from http://globocan.iarc.fr. 2012.

- Gregory, T.; Scott, M.; George, E.; Waun, K. In: Cancer Medicine. James FH, Emil FN, Robert CB, Donald WK, Donald LM, Ralph RW, editors. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1993. Head and neck cancer; pp. 1211–1274.

- Cogliano, V.; Baan, R.; Straif, K.; Grosse, Y.; Lauby-Secretan, B.; El Ghissassi, F.; Bouvard, V. et al. Preventable exposures associated with human cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(24):1827–1839. [CrossRef]

- Zygogianni, A.; Kyrgias, G.; Karakitsos, P.; Psyrri, A.; Kouvaris, J.; Kelekis, N.; Kouloulias, V. Oral Squamous Cell Cancer: Early Detection and the Role of Alcohol and Smoking. Head Neck Oncol.2011;3(2) . [CrossRef]

- Zygogianni, A.; Kyrgias, G.; Mystakidou, K.; Antypas, C.; Kouvaris, J.; Papadimitriou, C.; Armonis, V.; Alkati, H.; Kouloulias, V. Potential Role of the Alcohol and Smoking in the Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck: Review of the Current Literature and New Perspectives. Asian Pac J Cancer. 2011;12(2):339-344.

- Machiels, J.; Rene Leemans, C.; Golusinski, W.; Grau, C.; Licitra, L.; Gregoire, V. et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, larynx, oropharynx and hypopharynx: EHNS-ESMO-ESTRO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(11):1462–75. [CrossRef]

- Vokes, E. In Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, Wilson JD, Maltin JB, Kasper DL, et al., editors. Vol. 16. New York: McGraw Hill; 2005. Head and neck cancer; pp. 503–506.

- Pai, S.; Westra, W.; Molecular pathology of Head and Neck cancer: implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:49-70.

- Mali, SB. Adaptive Radiotherapy for Head Neck Cancer. Journal Of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery. 2016;15(4): 549-554. [CrossRef]

- Kouloulias, V.;Thalassinou, S.; Platoni, K.; Zygogianni, A.; Kouvaris, J.; Antypas, C.; Efstathopoulos, E.; Kelekis, N. The treatment outcome and radiation-induced toxicity for patients with head and neck carcinoma in the IMRT era: a systematic review with dosimetric and clinical parameters. Biomed Res Int. 2013:401261. [CrossRef]

- Ackerstaff, A.; Rasch, C.; Balm, A.; de Boer, J.; Wiggenraad, R.; Rietveld, D. et al. Five-year quality of life results of the randomized clinical phase III (RADPLAT) trial, comparing concomitant intra-arterial versus intravenous chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2012;34(7):974–80.

- Langendijk, J.; Doornaert, P.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.; Leemans, C.; Aaronson, N.; Slotman, B. Impact of late treatment-related toxicity on quality of life among patients with head and neck cancer treated with radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(22):3770–3776 . [CrossRef]

- Yeh Shyh-An. Radiotherapy for Head and Neck Cancer. Semin Plast Surg. 2010; 24(2): 127–136.

- Heukelom, J.; Fuller, C. Head and Neck Cancer Adaptive Radiation Therapy (ART): Conceptual Considerations for the Informed Clinician. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2019; 29(3): 258–273. [CrossRef]

- Surucu, Murat.; Shah, K.; Roeske, J.; Choi, M.; Small, W.; Emami, B. Adaptive Radiotherapy for Head And Neck Cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2017; 16(2): 218-223. [CrossRef]

- Aly, F.; Miller, A.; Jameson, M.; et al. A prospective study of weekly intensity modulated radiation therapy plan adaptation for head and neck cancer: improved target coverage and organ at risk sparing. Australas Phys Eng Sci Med. 2019; 42:43–51 . [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, V.; Patel, P.; Gurjar, O.; Lal Gupta, K. Impact of repeat computerized tomography replan in the radiation therapy of head and neck cancers. J Med Phys. 2014; 39(3):164-168. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, O.; Reis, I.; Samuels, M.; Elsayyad, N.; Bossart, E.; Both, J.; et al. Prospective Pilot Study Comparing the Need for Adaptive Radiotherapy in Unresected Bulky Disease and Postoperative Patients With Head and Neck Cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2017; 16(6); 1014-1021. [CrossRef]

- Glide-Hurst, C.; Lee, P.; Yock, A.; Olsen, J.; Cao, M.; et al. Adaptive radiation therapy (ART) strategies and technical considerations: A state of the ART review from NRG Oncology. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021; 109(4): 1054–1075. [CrossRef]

- Alfouzan Afnan. Radiation therapy in head and neck cancer. Saudi Med J. 2021;42(3): 247–254.

- Figen, M.; Oksuz, D.; Duman, E.; et al. Radiotherapy for Head and Neck Cancer: Evaluation of Triggered Adaptive Replanning in Routine Practice. Front Oncol. 2020; 10: 579917. [CrossRef]

- Nasser, N.; Yang, G.; Koo, J.; Bowers, M.; Greco, K. et al. A head and neck treatment planning strategy for a CBCT-guided ring-gantry online adaptive radiotherapy system. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2023; e14134. [CrossRef]

- Glide-Hurst, C.; Lee, P.; Yock, A.; Olsen, J.; Cao, M.; Siddiqui, F.; Parker, W.; et al. Adaptive Radiation Therapy (ART) Strategies and Technical Considerations: A State-of-the-ART Review From NRG Oncology. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021; 109(4):1054-1075. [CrossRef]

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Head and Neck Cancers, Version 2.2020. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(7):873-898.

- Nutting, C.; Morden, J.; Harrington, K.; Urbano, J.; Bhide, S.; et al. Parotid-sparing intensity modulated versus conventional radiotherapy in head and neck cancer (PARSPORT): a phase 3 multicentre randomized controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):127-136.

- Shang, Q.; Liu Shen, Z.; Ward, M.; Joshi, N.; Koyfman, S.; Xia, P. Evolution of treatment planning techniques in external-beam radiation therapy for head and neck cancer. Applied Radiat Oncol 2015; 4(3):18-25. [CrossRef]

- Connell, P.; Hellman, S. Advances in radiotherapy and implications for the next century: a historical perspective. Cancer Res 2009; 69: 383–392. [CrossRef]

- de Arruda, F.; Puri, D.; Zhung, J.; et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy for treating oropharyngeal carcinoma: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64(2):363-373.

- Mallick, I.; Waldron, J.; Radiation therapy for head and neck cancers. Semin Oncol Nurs 2009; 25: 193–202.

- Ghosh, A.; Gupta, S.; Johny, D.; Bhosale, V.; Negi, M. A Study to Assess the Dosimetric Impact of the Anatomical Changes Occurring in the Parotid Glands and Tumour Volume during Intensity Modulated Radiotherapy using Simultaneous Integrated Boost (IMRT-SIB) in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancers. Cancer Med. 2021;10:5175–5190. [CrossRef]

- Burela, N.; Soni, T.; Patni, N.; Natarajan, T.; Adaptive intensity-modulated radiotherapy in head-and-neck cancer: A volumetric and dosimetric study. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2019;15:533–538.

- Lee, C., Langen, K., Lu, W., Haimerl, J., Schnarr, E., Ruchala, K., Olivera, G., Meeks, S., Kupelian, P., Shellenberger, T., et al. Assessment of parotid gland dose changes during head and neck cancer radiotherapy using daily megavoltage computed tomography and deformable image registration. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:1563–1571. [CrossRef]

- Thomson, D., Beasley, W., Garcez, K., Lee, L., Sykes, A., Rowbottom, C., Slevin, N. Relative plan robustness of step-and-shoot vs rotational intensity–modulated radiotherapy on repeat computed tomographic simulation for weight loss in head and neck cancer. Med Dosim. 2016;41:154–158. [CrossRef]

- Buciuman, N.; Marcu, L. Adaptive Radiotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer Using Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy. J Pers Med. 2022; 12(5):668. [CrossRef]

- Nicosia, L.; Sicignano, G.; Rigo, M.; Figlia, V.; Cuccia, F.; De Simone, A.; Giaj-Levra, N.; Mazzola, R.; Naccarato, S.; Ricchetti, F.; et al. Daily dosimetric variation between image-guided volumetric modulated arc radiotherapy and MR-guided daily adaptive radiotherapy for prostate cancer stereotactic body radiotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2021, 60, 215–221. [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.; Schetllno G., Nisbet, A. UK adaptive radiotherapy practices for head and neck cancer patients. BJR Open. 2020; 11;2(1):20200051. [CrossRef]

- Barker, J.; Garden, A.; Ang, K.; et al. Quantifying volumetric and geometric changes occurring during fractionated radiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer using an integrated CT/linear accelerator system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59(4):960-970.

- Abdelhafiz, N.; Mahmoud, D.; Gad, M.; Essa, H.; Morsy, A. Effect of definitive hypo-fractionated radiotherapy concurrent with weekly cisplatin in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Med Life. 2023;16(5):743-750. [CrossRef]

- Baujat, B.; Borhis, J.; Blanchard, P.; et al. Hyperfractionated or accelerated radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010(12): CD002026. [CrossRef]

- Lacas, B.; Bourhis, J.; Overgaard, J.; et al. Role of radiotherapy fractionation in head and neck cancers (MARCH): an updated meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2017; 18(9):1221-1237. [CrossRef]

- Bourhis, J.; Overgaard, J.; Audry, H.; et al. Hyperfractionated or accelerated radiotherapy in head and neck cancer: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006; 368(9538):843-854. [CrossRef]

- Bertholet, J.; Anastasi, G.; Noble, D.; Bel, A.; van Leeuwen, R.; Roggen, T.; et al. Patterns of practice for adaptive and real-time radiation therapy (POP-ART RT): part II offline and online plan adaption for interfractional changes. Radiother Oncol.2020; 33:333–338. [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.; Pajak, T.; Trotti, A.; et al. A Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) phase III randomized study to compare hyperfractionation and two variants of accelerated fractionation to standard fractionation radiotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: first report of RTOG 9003. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;48(1):7-16. [CrossRef]

- Bobić, M.; Lalonde, A.; Nesteruk, K.; et al. Large anatomical changes in head-and-neck cancers – A dosimetric comparison of online and offline adaptive proton therapy. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2023; 40:100625. [CrossRef]

- Capelle, L.; Mackenzie, M.; Field, C.; Parliament, M.; Ghosh, S.; Scrimger, R. Adaptive radiotherapy using helical tomotherapy for head and neck cancer in definitive and postoperative settings: initial results. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2012; 24(3):208-215. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Ma, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; et al. Assessment of anatomical and dosimetric changes by a deformable registration method during the course of intensity-modulated radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Radiat Res. 2014;55(1):97–104. [CrossRef]

- Olteanu, L.; Berwoutz, D.; Madani, I.; et al. Comparative dosimetry of three-phase adaptive and non-adaptive dose-painting IMRT for head-and-neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2014; 111(3): 348–353. [CrossRef]

- Reali, A.; Anglesio, S.; Mortellaro, G.; et al. Volumetric and positional changes of planning target volumes and organs at risk using computed tomography imaging during intensity-modulated radiation therapy for head–neck cancer: an ‘‘old’’ adaptive radiation therapy approach. La Radiologia Medica. 2014; 119:714–720. [CrossRef]

- Castelli, J.; Simon, A.; Louvel, G.; Henry, O.; Chajon, E.; et al. Impact of head and neck cancer adaptive radiotherapy to spare the parotid glands and decrease the risk of xerostomia. Radiat Oncol. 2015; 10:6. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Simon, A.; Rigaud, B.; Castelli, J.; Ospina Arango, J.; et al. Optimal adaptive IMRT strategy to spare the parotid glands in oropharyngeal cancer. Radiother Oncology. 2016;120 (1): 41–47. [CrossRef]

- van Kranen, S.; Hamming-Vrieze, O.; wolf, A.; et al. Head and Neck Margin Reduction With Adaptive Radiation Therapy: Robustness of Treatment Plans Against Anatomy Changes. Intern J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016; 96(3):653-660. [CrossRef]

- Dewan, A.; Sharma, S.; Dewan, A.; et al. Impact of Adaptive Radiotherapy on Locally Advanced Head and Neck Cancer - A Dosimetric and Volumetric Study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016; 17 (3): 985-992. [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Liu, X.; Lu, H.; Huang, H.; Shu, L.; et al. Three-Phase Adaptive Radiation Therapy for Patients With Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Undergoing Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy: Dosimetric Analysis. Technol Cancer Res Treat.2017; 16(6): 910–916.

- Castelli, J.; Simon, A.; Laford, C.; Perichon, N.; Rigaud, B.; Chajon, E.; et al. Adaptive radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Acta Oncologica. 2018; 57(10): 1284-1292. [CrossRef]

- Mnejja, W.; Daoud, H.; Fourati, N.; Sahnoun, T.; Siala, W.; Farhat, L.; Daoud, J.; et al. Dosimetric impact on changes in target volumes during intensity-modulated radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2020; 25(1); 41-45. [CrossRef]

- Hay, L.; Paterson, C.; McLoone, P.; Miguel-Chumacero, E.; Valentine, R.; et al. Analysis of dose using CBCT and synthetic CT during head and neck radiotherapy: A single centre feasibility study. Tech Innov Patient Support Radiat Oncol. 2020;23(14):21-29. [CrossRef]

- Avkshtol, V.; Meng, B.; Shen, C.; Choi, B.; Okoroafor, C.; et al. Early Experience of Online Adaptive Radiation Therapy for Definitive Radiation of Patients With Head and Neck Cancer. Advances in Radiat Oncol. 2023; 8. 101256. [CrossRef]

- Duma, M.; Kamper, S.; Schuster, J.; Winkler, C.; Geinitz, H. Adaptive radiotherapy for soft tissue changes during helical tomotherapy for head and neck cancer. Strahlenther Onkol. 2012; 188(3):243–247. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.; Nill, S.; Huber, P.; Bendl, R.; Debus, J.; Munter, M. A clinical concept for interfractional adaptive radiation therapy in the treatment of head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012; 82(2): 590-596. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.; Garden, A.; Shah, S.; Chronowski, G.; Sejpal, S.; et al. Adaptive radiotherapy for head and neck cancer - Dosimetric results from a prospective clinical trial. Radiother Oncology. 2013; 106 (1): 80–84. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wan, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, X.; Xie, C.; Wu, S. The role of replanning in fractionated intensity modulated radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiother Oncology. 2011; 98 (1): 23–27. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, W.; Wang, W.; Chen, P.; Ding, W.; Luo, W. Replanning During Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy Improved Quality of Life in Patients With Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013; 85(1):e47-54. [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Daly, M.; Cui, J.; Mathai, M.; Benedict, S.; Pardy, J. Clinical outcomes among patients with head and neck cancer treated by intensity-modulated radiotherapy with and without adaptive replanning. Head Neck. 2014; 36(11): 1541-1546. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa El-Shahat, M.; Elshishtawy, W.; Al-Agamawi, A. Evaluation of Adaptive Radiation Therapy in Treatment of Locally Advanced Head and Neck cancers. Al-Azhar Intern Med J. 2021; 2(12): 51-58. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, W.; Zhou, C.; Zhu, J.; Ding, W. et al. Long-term outcomes of replanning during intensity-modulated radiation therapy in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: An updated and expanded retrospective analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2022; 170:136–142. [CrossRef]

- Kataria, T.; Gupta, D.; Goyal, S.; Bisht, S.; Basu, J. et al. Clinical outcomes of adaptive radiotherapy in head and neck cancers. Br J Radiol. 2016; 89: 20160085. [CrossRef]

| Aspects | Online ART | Offline ART |

|---|---|---|

| Timing of Plan Adaptation | Real-time, daily or even intra-fractional | Periodic, often weekly or bi-weekly |

| Imaging Frequency | Daily, often using CBCT | Periodic, less frequent imaging (e.g., weekly) |

| Adaptation Response Time | Immediate | Delayed, typically days to weeks |

| Treatment Efficiency | Time-consuming, may extend treatment duration | Less time-consuming, may minimize treatment interruptions |

| Anatomical Changes | Continuously monitored | Assessed periodically |

| Resource Requirements | Requires significant resources, including advanced imaging equipment | Requires fewer resources, often relies on conventional imaging |

| Precision in Tumor Targeting | High, allowing rapid response to changes | Good, with adaptations at intervals |

| Patient Comfort and Experience | Potential for longer treatment times | Potential for more consistent treatment times |

| Handling of Clinical Uncertainties | Offers real-time adaptation to uncertainties | May not address uncertainties as quickly |

| Clinical Applications | Applicable in dynamic or rapidly changing clinical scenarios | Suited for more stable anatomical conditions |

| No PTS | REPLANNING STRATEGIES | CLINICAL ENDPOINT | |||||||

| Author (year) | ART (NO ART) |

TUMOR SITE |

TOTAL DOSE (Gy) |

No of Replanning |

Timing (fraction) |

Follow-up (months) |

LOCOREGIONAL CONTROL and SURVIVAL | ACUTE TOXICITY (%) |

LATE TOXICITY |

| Zhao (2011) | 33 (66) |

NPC | 70 | 1 | 15th (+/- 5) | 38 | 3-year LRFS 72.7% (ART); 68.1% (No-ART) p = 0.3 | NR | Less xerostomia and mucosal with ART for N2 and N3 pts |

| Schwartz (2012) | 22 (0) |

OPC | 66-70 | 1 or 2 | 16th and 22nd | 31 | 2-year LRC=95% | G III mucositis: 100%, G II xerostomia: 55% G III xerostomia: 5% | Full preservation or functional recovery of speech and eating at 20 months |

| Yang (2013) | 86 (43) |

NPC | 70-76 | 1 or 2 | 15th and/or 25th Fr |

29 | 2-year LRC = 97.2% (ART); 82.2% (No-ART) p =0.04 2-year OS = 89.8% (ART); 82.2% (No-ART) p=0.47 | NR | Improvement in OoL with ART |

| Chen (2014) | 51 (266) |

LAHNC | 60 b 70 μ |

1 | 40 Gy (10-58 Gy) |

30 | 2-year LRC = 88% (ART); 79% (No-ART) p =0.01 2-year OS = 73% (ART); 79% (No-ART) p=0.55 | G III : 39% (ART) 30% (No-ART) P = .45 |

G III =14% (ART) 19% (No-ART) P = .71 |

| Kataria (2016) | 36 (0) |

LAHNC | 70 | 1 | 54 Gy | ----- | 2-year DFS = 72%. 2-year OS = 75% | G II-III mucositis=100% | – G II xerostomia = 8% – G II mucosal = 11%. – No G III toxicity |

| Surucu (2017) | 51 (17) |

LAHNC | 70.2 | 1 | 37.8 Gy (47 – 48.6) | 17.6 mos | Median DFS: 14.8 (0.9 – 57.5) mos Median OS: 21.1 (4.5 – 61.4) mos Residual Disease: 11.8 % Locoregional Control: 64.7% Metastatic disease: 23.5% |

Mucositis 35.3% Xerostomia NA Dysphagia 41.2% |

Mucositis NA Xerostomia 3.3% Dysphagia 20% |

| Mostafa (2021) | 49 (0) |

LAHNC | 70 | 1 | 42 Gy (37-44.1) | median 18 months (6.5 – 31) |

1-year PFS 89.7%; 2-year PFS 70.2% 1-year OS 89%; 2-year OS 83 % |

G II-III mucositis: 32.6 – 36.7 % G II-III Xerostomia: 44.9 - 16.3% | --------- |

| Zhou (2022) | 290 (147) |

NPC | NA | 1-2 | 15th-25th Fr | median (months) 104 ART; 96 no-ART |

8-year LRFS ART 87.4%; No-ART 75.6% 8-year DMFS ART 82.3%; No-ART 76.8% OS: 60.9 % (ART) / 59.4 % (no-ART) |

NR | G I-II Xerostomia: ART 96.5% - no-ART 90.5% G III-IV Xerostomia: ART 3.5% - no-ART 9.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).