1. Introduction

Moving away from fossil fuels is of great environmental, political, and economic importance. It is also a fact that energy transition is a materials transition, because all modern environmentally friendly technologies also need new, advanced materials. Also, the transportation infrastructures and whole energy system must become more efficient and sustainable. Most intense driving factors for the permanent magnets are the transportation sector, energy production and other emerging markets like robotics [1]. Rare Earths play a vital role in this transition scheme, and among all applications it is worth to underline the materials for permanent magnets, the most important enquirer in the rare-earth market, at least for some of these elements. The permanent magnet market is divided into two major categories, the high performing and expensive rare earth magnets and conventional, older materials based in other Fe compounds or transition metals like alnico or ferrites. A famous gap exists between these two categories; this gap is the objective target for many research efforts because the potential discovery of materials which can be used in this area may release resources for high performance applications while can also improve the design of other applications which are now based on the low performing magnets [2]. For all these reasons, the expected demand for permanent magnets is difficult to meet from the current supply chain [3,4].

Perhaps the most important improvement in high and medium performing permanent magnets is the combination of materials supply risk and temperature endurance. High temperature applications of the Nd-Fe-B system are limited due to the very low Curie temperature of the Nd2Fe14B main phase, just 588 K [5]. Minor improvements to achieve functionality in the vicinity of 450 K require processing with heavy rare earths, mostly Dy and Tb, raw materials which are expensive and immensely scarce. On the other hand, permanent magnets based on SmCo5 have quite improved temperature resistance with the main phase having a Curie temperature of 1020 K. Sm-Co permanent magnets were the first high-performance rare-earth permanent magnets [6,7,8,9] and still dominant in high-temperature high-energy-product applications even today [10,11].

Permanent magnets are widely used for various applications like electric motors, sensors, magnetic separators, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines. The growing adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) is a major factor driving the demand for permanent magnets mostly in EV motors. Additionally, the increasing focus on renewable energy especially in offshore wind turbines is providing further growth opportunities for the market [12].

Sm-Co based magnets are composed of Co which is characterized as a critical material and Sm [13,14]. Sm is a relatively expensive element among its group, and Co is also more expensive than Fe, making SmCo5 magnets the most expensive class of permanent magnets. As result, these magnets are economically viable mainly in high temperature applications where they cannot be replaced by other magnets [15,16,17,18].

Effective substitution can reduce the cost of a material and improve the magnetic properties as well the energy product. Large research has been carried out the last years to deal with these drawbacks. New intermetallic compounds based on SmCo5 type, suitable for permanent, are produced by substitution of Fe, Ni, Cu or other transition (or non-transition) elements for Co or by reducing the content of expensive raw rare-earth (RE) elements with other (RE), with larger abundance or less demand and thus less criticality and supply risk, like Ce, La. Ab-initio methods like DFT-based calculations and other theoretical methods are also widely used to clarify and predict if it is possible to follow the two routs mentioned above [13,17,18]. High entropy alloys is another interesting research field, however reports of such alloys will not be included in our study. The review aims to present the progress of recent years in the efficient replacement of high-cost elements in SmCo5-type magnets.

2. A short view of structure and magnetic properties of SmCo5 magnets

RCo

5 (R=Sm, Nd, Y, Ce) permanent magnets have been reported since 1967 [6]. The development of these magnets started with SmCo

5 compound which are made from an alloy consisting of samarium and cobalt, often combined with traces of other rare earth elements such as praseodymium and neodymium. SmCo

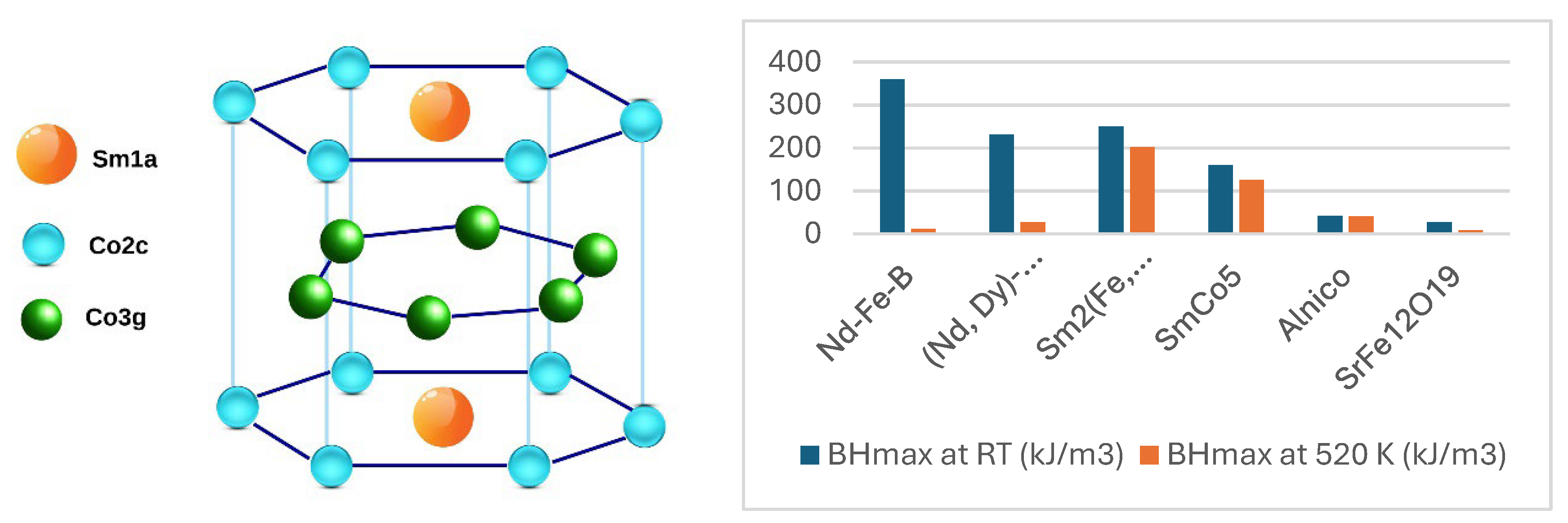

5 compounds crystallize in the hexagonal CaCu

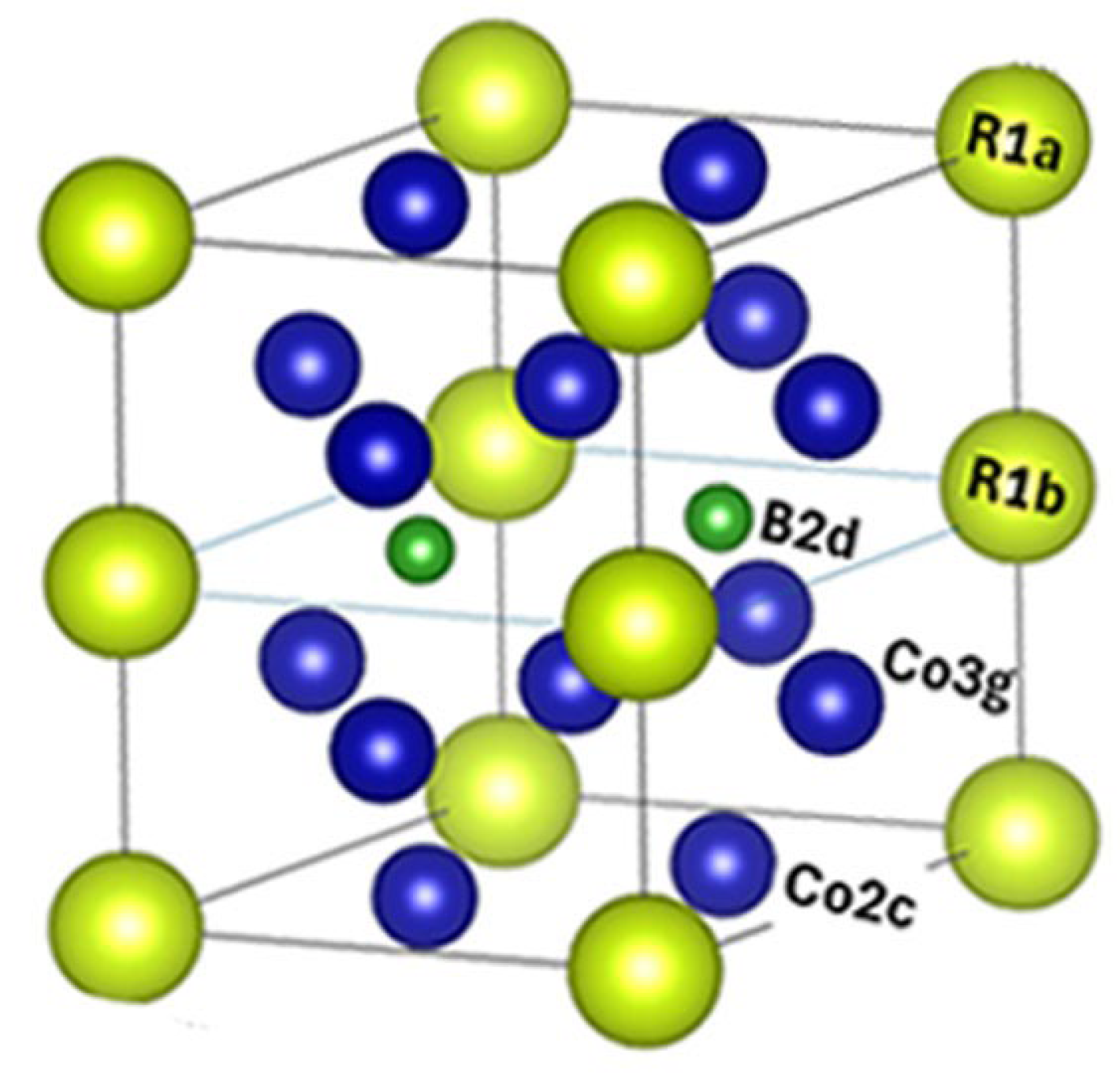

5-type structure with three non-equivalent atomic sites: Sm1-(1a), Co1-(2c), Co2-(3g) [19,20]. Crystal structure of SmCo

5 is shown in

Figure 1a.

SmCo

5 exhibits a relatively high saturation magnetization Ms and a high Curie temperature T

c up to 1020 K with an excellent magnetocrystalline anisotropy constant K1 of about 17.2MJ/m

3 [21,22]. The high coercivity of samarium–cobalt magnets originate from the Sm sublattice anisotropy, whereas the Co sublattice yields a high Curie temperature and stabilizes, via intercalative exchange, the magnetic anisotropy at high temperatures. Some magnetic properties of SmCo

5 and other compounds are given in the

Table 1. It can be observed that Nd

2Fe

14B has an energy product of 64.34 MGOe at RT, which drops to 1.52 MGOe at 523K, while SmCo

5 has an energy product of 20 MGOe, half that of Nd

2Fe

14B at RT, in contrast much higher at 523K. [10,22,23].

3. SmCo5 transition metal substitution (Fe, Cu, Ni, Zr, Ti, and Nb)

The transition metals occupy the short columns in the center of the periodic table, and sometimes are called the d-block elements, since in this region the d-orbitals are being filled in. The period 4 transition metals are Sc, Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, and Zn, while Nb belongs to period 5. In the transition metals, the five d orbitals are being filled in, and the elements in general have electron configurations of (n-1)d1-10 ns2, although there are some exceptions when electrons are shuffled around to produce half-filled or filled d subshells. Many of the transition metals can lose two or three electrons, forming cations with charges of 2+ or 3+, but there is some which form 1+ charges, and some which form much higher charges.

3.1.1. Substitution of Fe for Co

SmFe5 is metastable and does not appear in the equilibrium Sm–Fe phase diagram. The initial focus was on partial replacing Co with Fe because it is a cheaper and more abundant metal in the Earth's crust than cobalt, thus reducing the price of raw materials and potentially further improving the magnetic properties, especially the magnetization. SmCo5 is metastable even without Fe addition due to very limited equilibrium solubility of Fe in SmCo, making the substitution difficult. The formation of metastable Sm (TM)5 (TM = Fe-Co) compounds and their magnetic properties have been reported firstly by Miyazaki et al. since 1988 [24,25]. In that work the rapidly quenched Sm (CoxFe1-x)5 alloy ribbons were investigated. The ribbons prepared at velocity V = 41.9 m/s exhibit amorphous structure in the range 0≤ x ≤ 0.2 for Sm (Fe1-xCox,)5 alloys. The metastable Sm (TM)5 compound is formed with a single phase in the range 0.6 ≤ x ≤ 1.0 by quenching Sm (Fe1-xCox,)5 alloys. The single phase Sm(TM)5 compound exhibits a huge coercivity of 5 to 14 kOe. In spite of the large coercivities, the value of magnetization measured at 16 kOe was not as high as expected. Fe has the highest magnetic moment, while the coercivity of the Sm(CoxFe1–x)5 (x = 0.6–1.0) ribbons gradually decreased with an increase in Fe content.

Elsevier Similar works with the previous are reported later [26,27]. Structure and magnetic properties SmCo

5-xFe

x (x = 0–4) alloys produced by melt-spinning were investigated. XRD and thermomagnetic studies revealed that the Sm(Co, Fe)

5 phase can be obtained up to x = 2 in SmCo

5-

xFe

x (x = 0–2) melt-spun ribbons and that the large substitution of Fe for Co in the SmCo

5 alloy results in the formation of other phases such as the Sm(Co, Fe)

7 and Sm

2(Co, Fe)

7 phases. The remanence of the melt-annealed SmCo5-xFex ribbons increased when x increases from x=0 to x = 3 and then decreased with increasing Fe content, while their coercivity decreased as Fe content increased. The structures and magnetic properties of SmCo

5-xFe

x (x = 0–4) alloys produced by the melt-spinning technique were shown to be dependent on the Fe content. The annealed SmCo

4Fe alloy with the SmCo

2Fe

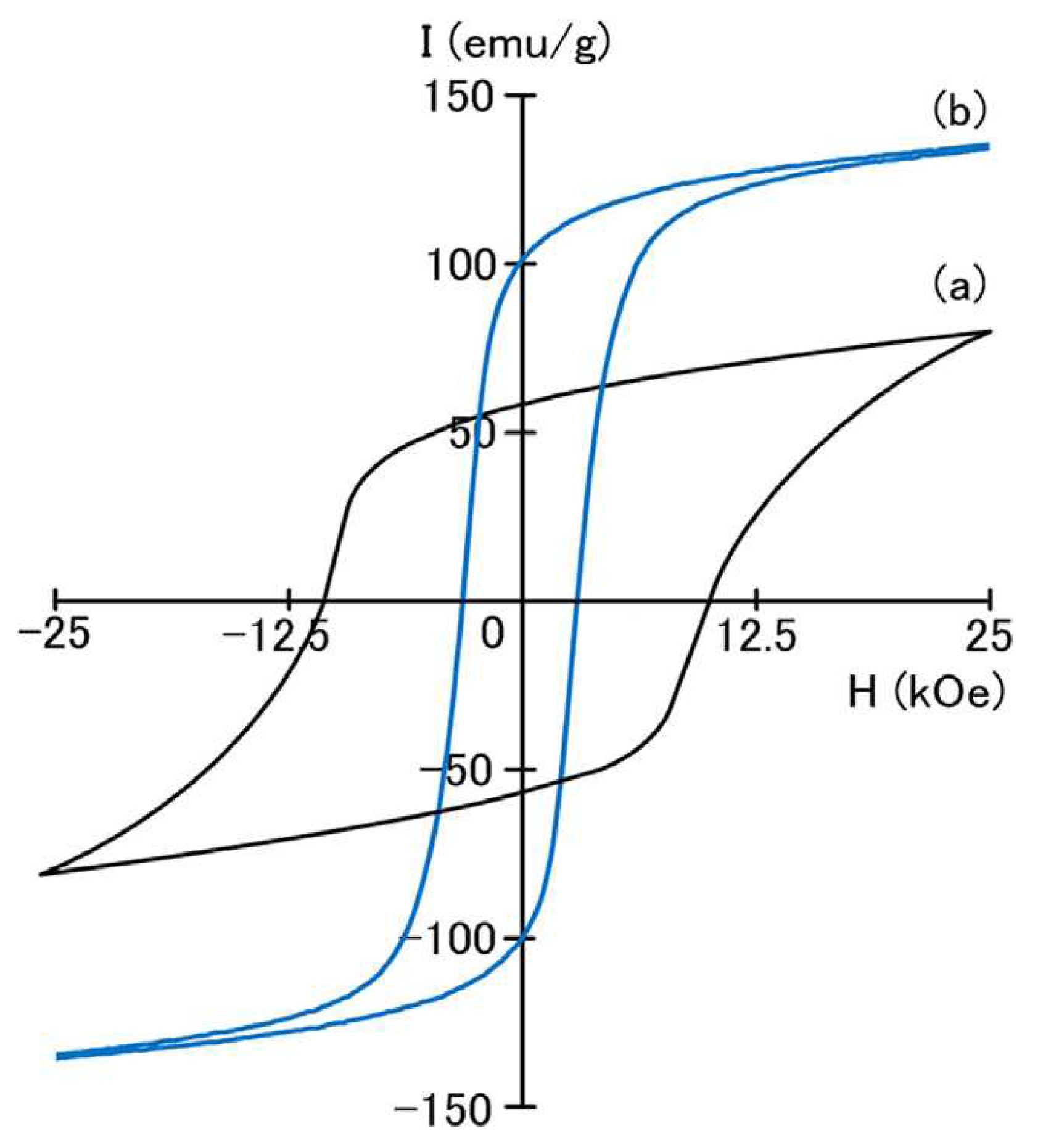

3 phase exhibit a high coercivity of 10.2 kOe with a remanence of 60 emu/g (

Figure 2), while the annealed SmCo

2Fe

3 alloy formed a nanocomposite magnet with a high remanence of 100 emu/g and a coercivity of 2.9 kOe. This result didn’t encourage further studies for only substitution of Co by Fe atoms.

Structural and magnetic properties of iron-substituted SmCo5 had also been investigated theoretically and experimentally lately [27,28,29]. Most of their findings are consistent with the past samarium-cobalt research. In ref [28] was explained the origin of magneto-crystalline anisotropy in Fe/Si substituted SmCo5. The substitution mechanism employing magnetic Fe and non-magnetic Si atoms suggests that the hexagonal ring of 2c sites containing Sm atom in the middle are responsible to maintain the magnetic hardness in the materials. This hardness is intrinsically defined by the 4f localized orbital contribution of Sm atoms. These localized orbitals are broadened and shift towards the Fermi energy when Co (2c) sites are substituted by the Fe atoms resulting in the decrease in the anisotropy contribution. Whereas the Co (3 g) layer contributes to the total magnetic moment of the compound and when it is substituted with Fe atoms, it not only helps to increase the total magnetic moment to 14.02 μB but also boosts the anisotropy by 10% in the SmCo2Fe3 as compared to SmCo5. While the Si substitution favors thermodynamic stability, on the contrary decreases the magnetization as well as the magnetic anisotropy in SmCo5.

The results of theoretical study of Sm(Co1-xFex)5 are in agreement with the experimental one [29]. According to their calculation, the magnetization increases from 7.8 to 10.6 μB with increasing x from 0 to 0.8. The Fe prefers to occupy the 3g site and the Fe content dependence of the magnetization shows a 3d-like Slater–Pauling relationship.

3.1.2 Substitution of Cu and other transition or non-transition elements for Co on SmCo5 alloys

The replacement of cobalt with copper was also reported in the early eighties. In some of the rare earth compounds (RCo5) (R=rare earth) they result in solid materials with significant permanent magnet properties. In magnet materials of the type R(Co, Cu)5, large coercive forces are already present in the as-cast form and these can be enhanced by annealing. Coercive forces as high as 28,7 kOe have been obtained in heat-treated samples of alloys in the system [29,30]. Some research on SmCo1-xCux, as cast, annealed alloys, or single crystal, was published in the 70s-80s [31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

According to Oesterreicher et al [36] the magnetic hardness in pseudo-binaries SmCo5-xCux may be an intrinsic property in nature, and not dependent on pinning by second phases. The temperature dependence of coercive force (He) is in accordance with a model based on thermally activated domain-wall propagation.

Microprobe and metallographic analysis of SmCo1-xCux indicate spinodal decomposition in as-cast material [31,32,33]. The increase of coercivity in Sm(Co,Cu)5 alloys upon annealing at relatively low temperatures of about 300–500°C has been associated with spinodal decomposition into Co- and Cu-rich Sm(Co,Cu)5 phases [31,33]. From the results of DTA and measurements of Tc and magnetic values, a hypothetical Sm–Co–Cu ternary phase diagram had been proposed, in which the alloys initially containing 24 to 40 at% copper may decompose [33]. The resulting components are still of CaCu -type structure but exhibit a randomly varying transition metal composition. Subsequent annealing at 1073–1273 K removes this variation in stoichiometry. The coercive field of these magnets is in the as-cast state based on domain-wall nucleation with subsequent weak pinning at the grain boundaries, whereas in the annealed alloy a domain-wall pinning process occurs [34,35]. Electron microscopy of cast samples (x=1.25, 1.75 and 2.25) showed the existence of three phases: a so-called ‘‘1–5 Co’’ phase, a so-called ‘‘1–5 Cu’’ phase (these phases show slightly different Co–Cu concentrations) and between the grains a Cu-rich ‘‘5–19’’ phase [35 check again].

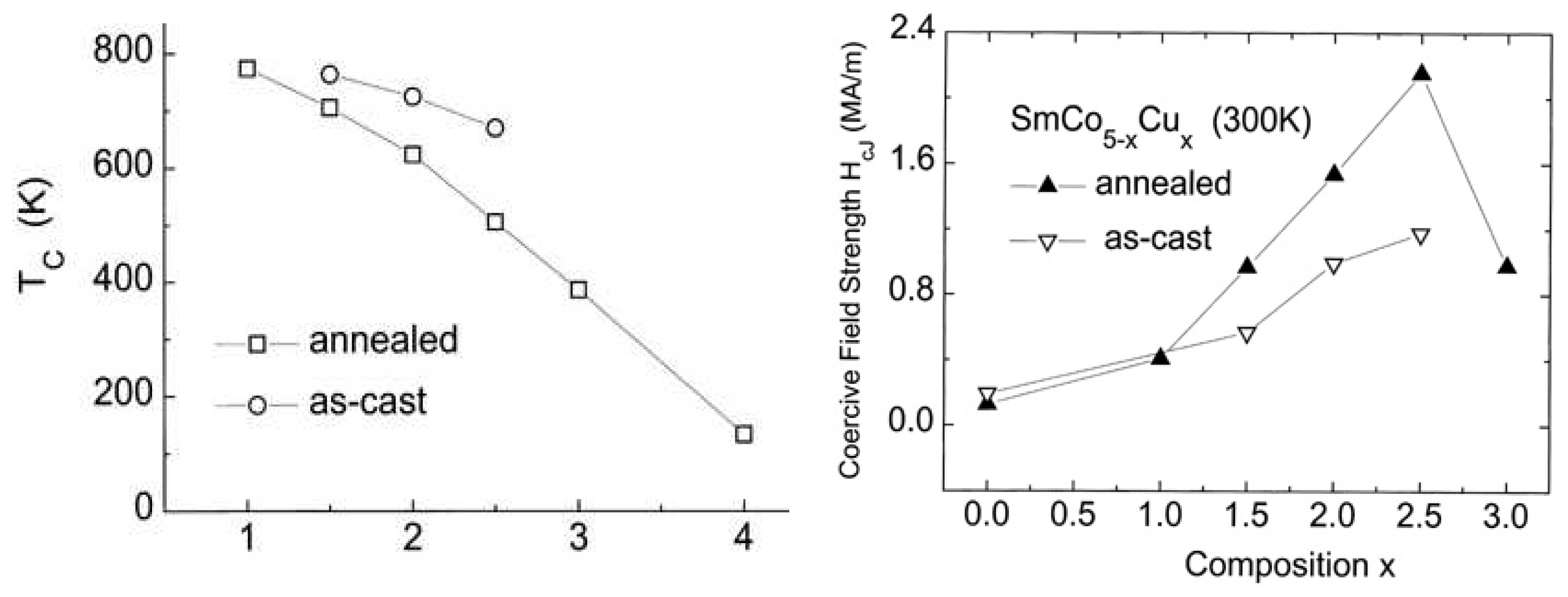

A systematic study of the properties of Sm(Co,Cu) magnets over a large temperature range had been reported by Blanco et al. later in the 90s [38,39]. They studied the magnetic properties of polycrystalline SmCo1-xCux (x=1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 4) samples in the as-cast state as well as after annealing. The Curie temperature decreases, whereas the lattice constantly increases with increasing Cu con-

tent (

Figure 3a). The coercivity field shows strong temperature and time dependence and reach a maximum for Sm

2.5Co

2.5 ribbons (

Figure 2b), results strongly support the major effect of the number of Cu atoms acting as local defects on the concentration, time and temperature dependence of the coercivity. Especially, they measured the hysteresis loops in SmCo

5-xCu

x as-cast and annealed magnets (1< x ≤3) at room temperature using a pulsed-field magnetometer and a static vibrating sample magnetometer [39].

The mechanism of the high intrinsic coercivity of the Sm(Co1-xCux)5 (0 < x ≤ 1) system was studied by relating the coherency between the lattice constants of hexagonal Sm(Co, Cu)5 and hcp Co to the coercive force [40]. In this work it was suggested that the coercivity in Sm(Co,Cu)5 can be caused by the Co precipitates along the grain boundaries. It is also analytically found that the intrinsic coercive force reaches a maximum in the composition range from x = 0.6 to 0.8.

Researchers often use expensive methods such as induction melting or arc melting in the range of 1300–1400 °C, then annealing the samples at high-temperature. For example Tellez-Blanco et al studied annealed Sm(Co, Cu)5 for 504 h (21 days) at 1000 °C [38,39]. Nishida et al. performed the annealing at more than 800 °C for 160 [41]. Gabay et al. annealed the Sm(Co, Cu)5 magnets for 100 h (50 h at 1050 °C then 50 h 350–450 °C) [42]. So, the synthesis of Sm–Co–Cu ternary alloys is a high consumption energy process.

A recent work deal with these problems using a reduction diffusion to synthesis, having energy and time efficient as compared to the regular physical methods.

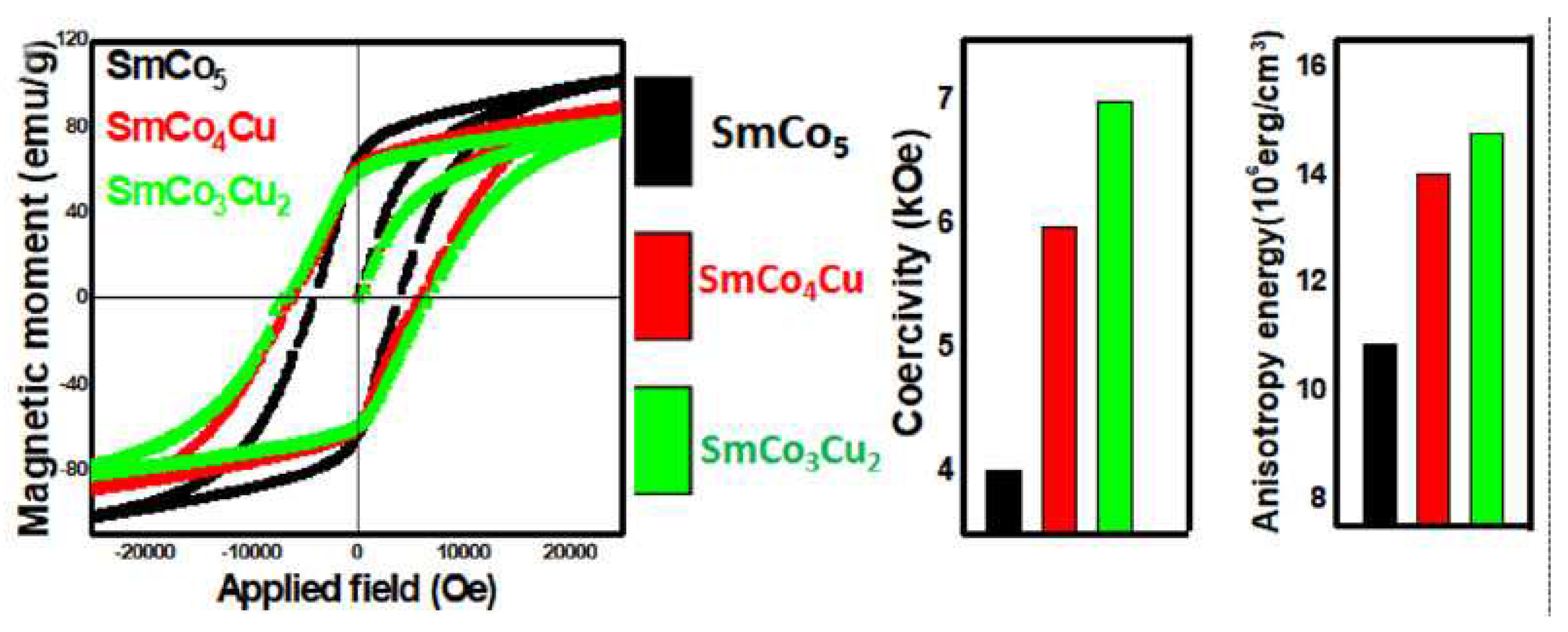

In this study was applied an eco-friendly chemical method and energy efficient process for the synthesis of the Cu substituted SmCo

5 magnetic particles. In this energy efficient process, precursors were annealed at 900 °C for only 2 h, with processing time much shorter than traditional one. The cost of the SmCo

5 is also reduced. After substitution at “2c” site in the SmCo

5 crystal lattice, Cu almost blocked the coupling in the surrounding. The resulted decoupling in the crystal lattice affected the magnetic moment, anisotropy and coercivity (

Figure 3). Magnetic moment was reduced as the result of Cu substitution, but coercivity and anisotropy energy were enhanced. Enhancement of the anisotropy energy increased the coercivity as its values for SmCo

5, SmCo

4Cu and SmCo

3Cu

2 were recorded as 4.5, 5.97 and 6.99 kOe respectively (

Figure 4).

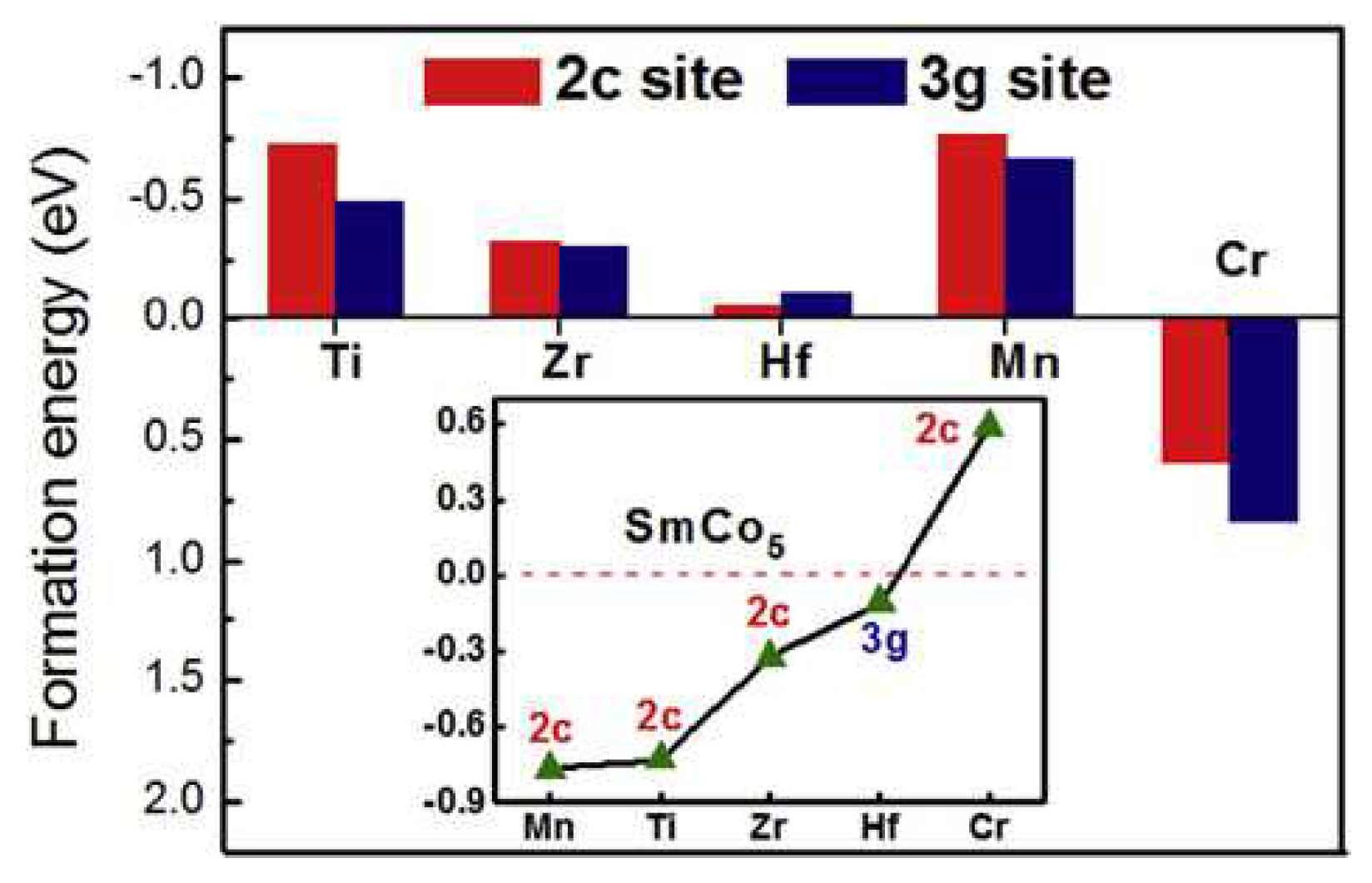

In addition to Fe and Cu substitution materials for Co in SmCo5, alloys with substitution of other elements such as Ni, Pt, Cu, Ag, Al, In, Si and Sn (transition or non-transition elements), had been synthesized [43,44]. The formation energy of the doping element at 2c and 3 g sites formation energy of SmCo4.5M0.5 with different elements at the preferential site and insert are shown in

Figure 4. The magnetic properties of these materials, such as saturation moments and coercive forces, were investigated at 4.2 K. Substitution of Co by non-magnetic elements like Al and Si generally decreases the saturation moment at 4.2 K, while Al and Si substitution for Co in SmCo

5 results in outstanding coercive forces of the order of 30 - 50 kOe in powder and bulk materials. All other systems were disappointing in terms of magnetic hardness.

The origin of outstanding magnetic hardness was discussed in terms of a model of the pinning of extremely energetic domain walls on obstacles of atomic dimension. Lately, structural stability, magnetic properties, and electronic structures of SmCo

4.5M

0.5 alloys with doping elements of transition metals M= Ti, Zr, Hf, Mn and Cr were studied based on the first principles calculations and statistical thermodynamics [45]. Formation energy of the doping element at 2c and 3 g sites is shown in

Figure 5. It was found that the addition of Ti, Zr, Hf and Mn was beneficial to the stability of the SmCo

5 phase, while doping of Cr was detrimental. It was found that the SmCo

4.5M

0.5 ternary alloys can be stabilized by Mn, Ti and Hf doping over a wide temperature range, while the overall magnetic moment of the SmCo

4.5M

0.5 system was usually weakened by non-magnetic element doping to some extent. However, doping with Mn can increase the total magnetic moment.

3.1.3. Simultaneous substitution of two or more transition metals like Fe and Cu for Co in SmCo5 alloys

Gabay and al. studied the stability of RCo5−xCux(R = Y, Sm) compounds with respect to phase separation [42]. Using the first principles density functional calculations, they imply the decomposition into two phases having different x is energetically favorable and both the stable x values and the Cu atomic site preferences depend on the magnetic state of the alloys.

Effect of annealing temperature on Curie temperature and room-temperature coercivity of SmCo4Cu1, SmCo3.5Cu1.5, SmCo3Cu2 and SmCo2.25Fe0.75Cu2 were investigated. The coercivity increases significantly if annealed 100–140°C below the Curie temperature; in particular, for SmCo2.25Fe0.75Cu2, the room-temperature coercivity increases from 12.3 to 37.3 kOe. Contrary to ref. [30,31,32], their experimental results do not support the spinodal decomposition theory. They suggest that the coercivity increases might be caused by a change in preferred atomic site occupancies.

Enhancement of the energy product of SmCo5 magnets was limited by the remanent magnetization of SmCo5 compound. Exploration of both Fe, Cu substituted was also successfully applied in SmCo5 [46]. One more substitution element, the Zr atom for Sm, was applied in Sm2Co17 magnets [47]. The large atomic percentage of Fe and Co in the cell phase contributes to the large remanence and high saturation magnetization, and Cu in the cell boundary phase is responsible for enhancement of coercivity by domain wall pinning mechanism [48]. The magnetic properties of this kind of as cast alloys depend strongly on the annealing temperature and cooling rate. The best prepared magnet with composition SmFe0.4Co3.5Cu1.1 has a maximum energy product of 13 MGOe. This alloy was annealed for 2 hrs at 1100 oC, then slow cooling in argon atmosphere [49].

Initial magnetization curves of as-spun SmCo3.8390Cu0.48Fe0.48 ribbons and the variation of magnetization versus wheel speed at 20 kOe were carried out. Higher wheel speed ribbons (≥ 30 m/s) exhibited single phase SmCo5. The coercivity was found to increase with increase of the wheel speed. A high coercivity of ∼33 kOe was obtained in ribbon prepared at 50 m/s. The high coercivity obtained at high wheel speed is due to formation of the high magnetocrystalline anisotropic single phase Sm(CoCuFe)5, and to reduction of the grain size.

It is worth mentioning the substitution of Cu-Ti for Co magnets in Sm-Co reported by Zhu et al. [50]. A new class of promising permanent-magnet materials with an appreciable high-temperature coercivity of 8.6 kOe at 500 °C was produced. Magnetization measurements as a function of temperature and x-ray diffraction patterns indicate that the samples are two-phase mixtures of 2:17 and 1:5 structures.

4. Substitution of p-elements for Co

The influence of substitution of p elements like Al, B, Ga for Co on the magnetic properties of the RCo

5 (

R=Y, Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb) type phases has been also investigated [51,52,53,54]. In ref [51], structural and magnetic properties of the RCo

4B with different rare-earth elements (

R=Y, Pr, Nd,

Sm, Gd, Tb) are reported. The RCo

4B phases crystallize in the hexagonal CeCo

4B type of structure (space group P6/mmm) which is a derivative of the RCo

5 type of structure [56] by a regular substitution of Co by B in every second layer of the CaCu

5 structure (2c site). A schematic description of the structure is given in

Figure 6. It shows that the R atoms occupy the 1a and 1b sites, the Co atoms are in the 2c and 6i sites, and the B atoms reside in the 2d site. The saturation magnetization

Ms and T

c were decreased upon the B for Co substitution. However, the SmCo

4B compound still possesses excellent magnetic properties and is promising for permanent magnet applications.

The c lattice parameter of the hexagonal structure remains almost constant, while a parameter goes up when the atomic radius of the rare-earth element increases. The compounds with R=Y, Pr, and Nd are ferromagnetically ordered, whereas the compounds with Gd and Tb are ferrimagnetic. The evolution of the easy magnetization direction at room temperature depends on R content. In contrast to the substitution effect of B for Co in the RCo5 compound, which crystallizes into CeCo4B type of structure, the substitution of Co by Ga and Al preserves the CaCu5-type structure of RCo5 [55]. Whereas the saturation magnetization and the Curie temperature are drastically reduced upon Ga or Al for Co substitution, on the contrary the magnetocrystalline anisotropy and coercivity was much larger for the substituted compounds.

As it was mentioned above, adding Cu or Al to SmCo5 increases the coercivity but reduces the magnetization. What would happen if Al, Cu and Fe were added to the SmCo5 alloy at the same time? The response to this question was given in ref. [57,58]. In this works, SmCo5 + x wt% Al82.8Cu17Fe0.2 (x=3-7) ribbons melt-spun at 40 m/s were prepared. It is found the annealing improves the crystallinity of the grains, changes the phase composition and microstructure, especially the distribution of Sm(Co, M)7 phase. The 3 wt% – 5 wt% Al-Cu-Fe alloying addition is the most effective for improving the hard magnetic properties of the SmCo5-based ribbons. Annealing its at 500 oC increases both the coercivity (Hc) and magnetization; increasing the temperature up to 600 oC, the maximum Hc of 26.8 kOe was obtained, but the magnetization decreases. The reason for the increase in coercivity at 600 oC can be attributed to the high content of Sm(Co, M)5 grains, which improved the crystallinity and grain refinement.

5. A new promising magnetic material of CaCu5 structure

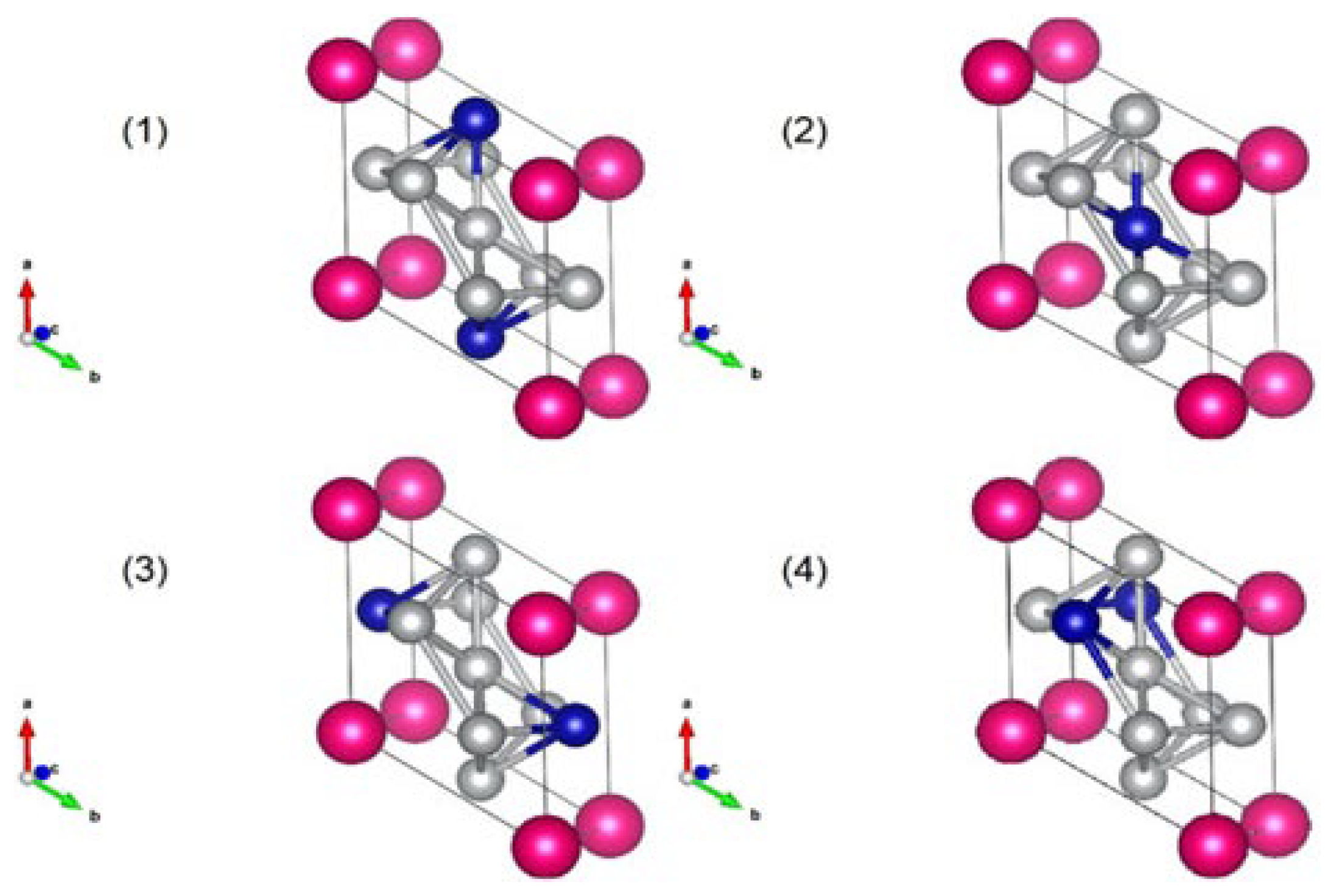

Recently, the effect of Ni substitution of Co on the crystal structure of SmCo

5 has been investigated by computational methods [59], with the aim of determining the structure that will be stable and at the same time maintain high magnetization values. A series of atomistic simulations are implemented based on Density Functional Theory calculations. Various simulations are performed by considering all possible crystallographic positions of Co and Ni atoms in a SmCo

5−xNi

x compound. A schematic illustration of four different cases of the unit cell of SmCoNi

4 is shown in

Figure 7.

An experimental implementation based on the sample with x = 1 was presented to translate the findings from atomistic simulations to realizable bulk materials. Interestingly, it is concluded that in many cases an energetically favourable atomistic configuration does not exhibit maximum magnetization. It should be noted that for the experimentally investigated case of SmCo4Ni, both the energetically favourable as well as the magnetically maximum configuration have been identified.

Thus, only replacing Ni with Co in the SmCo5 system does not favor maximum magnetization. From a cost standpoint, it is beneficial to substitute Co atoms with Fe because Fe in the Earth’s crust is ~2000 times more abundant than Co and consequently much cheaper. In addition, Fe is a ferromagnetic metal with a very large magnetization at room temperature (1.76 MA/m) [60]. However, replacing all cobalt with iron to maximize magnetization in SmFe5 makes it thermodynamically unstable and does not exist in the Sm-Fe equilibrium phase diagram. Recently, binary Sm-Fe alloys with the SmFe5 phase was produced for the first time by optimizing the annealing conditions of rapidly quenched melt-spun ribbons [61]. It was found that the as-rapidly quenched SmFe5 melt-spun ribbon consisted of SmFe5 grains, reaching a coercivity of 1.2 kOe after annealing at 1073 K.

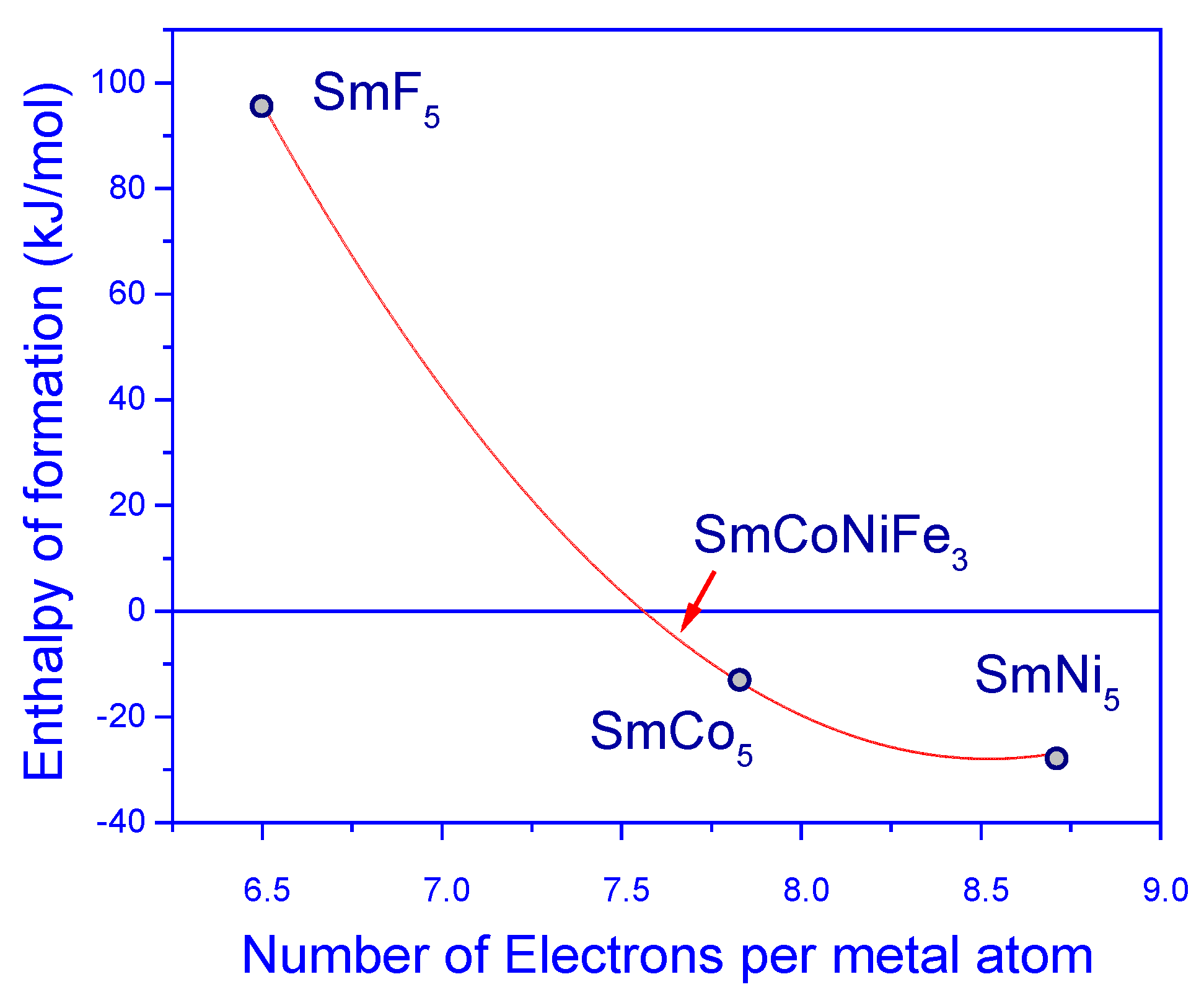

This controversy was recently addressed by two theoretical studies, where the stability of modified SmCo

5 alloys by partial replacement of Co by Fe and Ni at the same time was investigated [62,63]. P. Söderlind et al. had proposed a new efficient permanent magnet, SmCoNiFe

3, which is a development of the well-known SmCo

5 prototype. They found a correlation between the number of transition-metal (TM) 3d electrons and the stability of the hexagonal SmTM

5 compound (TM = Fe, Co, or Ni). Calculated dependence of enthalpy formation on number of 3d electrons was plotted in

Figure 8. Negative enthalpy indicate thermodynamic stability. The values of energy formation for SmM

5 (M=Ni, Co) was given in ref. [64,65].

By means of first-principles electronic-structure calculations they found that the magnetic properties of SmCoNiFe

3 (energy product, Tc, Ms) are better than the respective properties of Nd-Fe-B types of magnets (

Table 2). Substituting most of the cobalt with iron in SmCo

5 and doping with a small amount of nickel results in a new permanent magnet, which can potentially replace SmCo

5 or Nd-Fe-B types in many applications.

The enthalpy formation of SmCoNiFe3 was just below the dividing line of the stable-unstable enthalpy formation region. Increasing the number of 3d electrons (more Ni) greatly stabilizes the compound. Extrapolating the experimental heats of formation, it can be seen that an alloy is stable with at least 7.2 3d electrons per TM atom. SmCoNiFe3 has about 7.3 3d electrons, which is enough to stabilize the compound.

Despite the confidence in the manufacturing of CoNiSmFe3, the experimental synthesis of this compound has not yet been reported. An approach toward this synthase was attempted by Gavrikov et al. and G. Sempros et al. [66,67]. Based on calculation, the Sm(Co1−x−yFexNiy)5 (x = 0.15, 0.3, 0.45; y = 0.05, 0.1, 0.15) melt-spun ribbons were then synthesized [66]. The ribbons consisted of two phase, the main phase is SmCo5,(up to 70% ) the other one is of Sm(CoFe)3 type. The increase of Co atom substitution leads to the lattice expansion, reduction of Curie point, increasing saturation magnetization and decreasing of coercive field. The doping levels of Fe and Ni atoms reach a maximal value in SmCo2Fe2.25Ni0.75 sample. Among their samples, SmCo3Fe1.5Ni0.5 reaches the highest coercivity (10.9 kOe), remanent magnetization of 51 emug−1 and thus the highest energy product.

According to the predictions of ab initio simulations [67], the SmCo2.5Fe1.5Ni stoichiometry presents a large value of total magnetization which is comparable to the respective value of SmCo5. The partial substitution of Co with both Fe and Ni leads to a favorable interplay between stability and magnetization and the additional benefit of the reduction of the content of Co. However, the experimental values of SmCo2.5Fe1.5Ni were lower than predicted due to secondary impurity phases.

6. Recent research on Mm (Misch-metal) substitution for Sm on SmCo5 alloys.

Replacing Co with other transition or non-transition elements improves some magnetic properties such as coercivity and anisotropy field at the expense of others such as energy product or does not produce stable phases, suitable for bulk permanent magnets [61]. Thus, a possible substitution scheme in the SmCo5 alloys cannot rely entirely on a transition metal (or non-transition element) sublattice but could also include that of rare earths. Sm replacement could be realized with a light rare earth atom, with atomic number less than Gd. These atoms have negative Stevens coefficients as opposed to Sm which has a positive one [5], this practically means that their 4f orbital has different shape and possibly favors different arrangement within the crystal field of the material making possible that they could provide different magnetic properties in the case of simultaneous substitution within both the rare earth and transition metal sublattices. Within the lanthanide series there are also variations in the relative content of the reserves. Most of the mining sites around the world are composed of minerals that contain a mixture of various rare earth oxides, their relative amounts are not the same. Heavy rare earths are less abundant while some elements, namely Ce and La, are practically over produced [68]; sometimes they are referred as “free rare earths.” This fact is often denoted as the rare earth balance issue [69].

A high performing permanent magnet seems unlikely to be manufactured with Ce or La as basic ingredients, due to the specific properties of these atoms and especially their electronic configuration. However, a partial replacement of a expensive rare earth element by a less expensive one may establish a material which could be used as the basis for a “gap” magnet [15] and may find potential use in applications with low cost. Due to the different shape of the 4f orbital and thus the impact on the nature of the interactions within the crystal field, this partial replacement may provide a path towards replacement High-cost Sm in the Sm-Co system.

Development of new materials and alloys with using La-Ce selective modification has been demonstrated recently in the case of Nd-Fe-B based permanent magnets [70,71]. The introduction of Ce and La in SmCo5 system has attracted attention as early as the discovery of the initial compound. M. G. Benz and D. L. Martin studied Sm-Co magnets where Sm was partially substituted by Misch Metal [72]. In the specific study, the Misch Metal contained a large amount of other rare earths, mostly Nd, but the three quarters of the mass content were Ce and La in 2:1 mass ratio. Results were encouraging since a BHmax of about 20 MGOe, about 60% of SmCo5-based permanent magnets while possessing some advantages like the simplification of the overall processing and the compatibility with existing industrial infrastructure. Specific properties are positively affected and regarding the supply cost, the overall merit of the material is improved. Another important field towards development of new materials suitable for PM applications is the theoretical understanding of the underlying physics.

Lately, a recent series of theoretical as well as experimental studies developed the possibility of simultaneously introducing metallic Ce-La at a Ce:La ratio of 3:1 into the SmCo5 system and reducing the Co content [67,73,73,74,75]. The theoretical framework of the compounds and the relevant ab-initio parameters were intensively investigated. Preliminary calculations showed that the case of 50% replacement of Sm by Ce3La misch metal was of specific interest and was used to calibrate the methodology, together with SmCo5, CeCo5 and LaCo5 stoichiometries. For CeCo5 the magnetization was calculated to be lower than that of SmCo5 due to antiferromagnetic coupling of rare earth atoms.

It was also detected that the Ce electronic states are located closer to the Fermi level compared to the other cases [74]. This is an indication of the important role of Ce atoms in the modification of the magnetic properties upon substitution of Sm. However, the most dominant factor for magnetization is still the Co–Co interatomic distances.

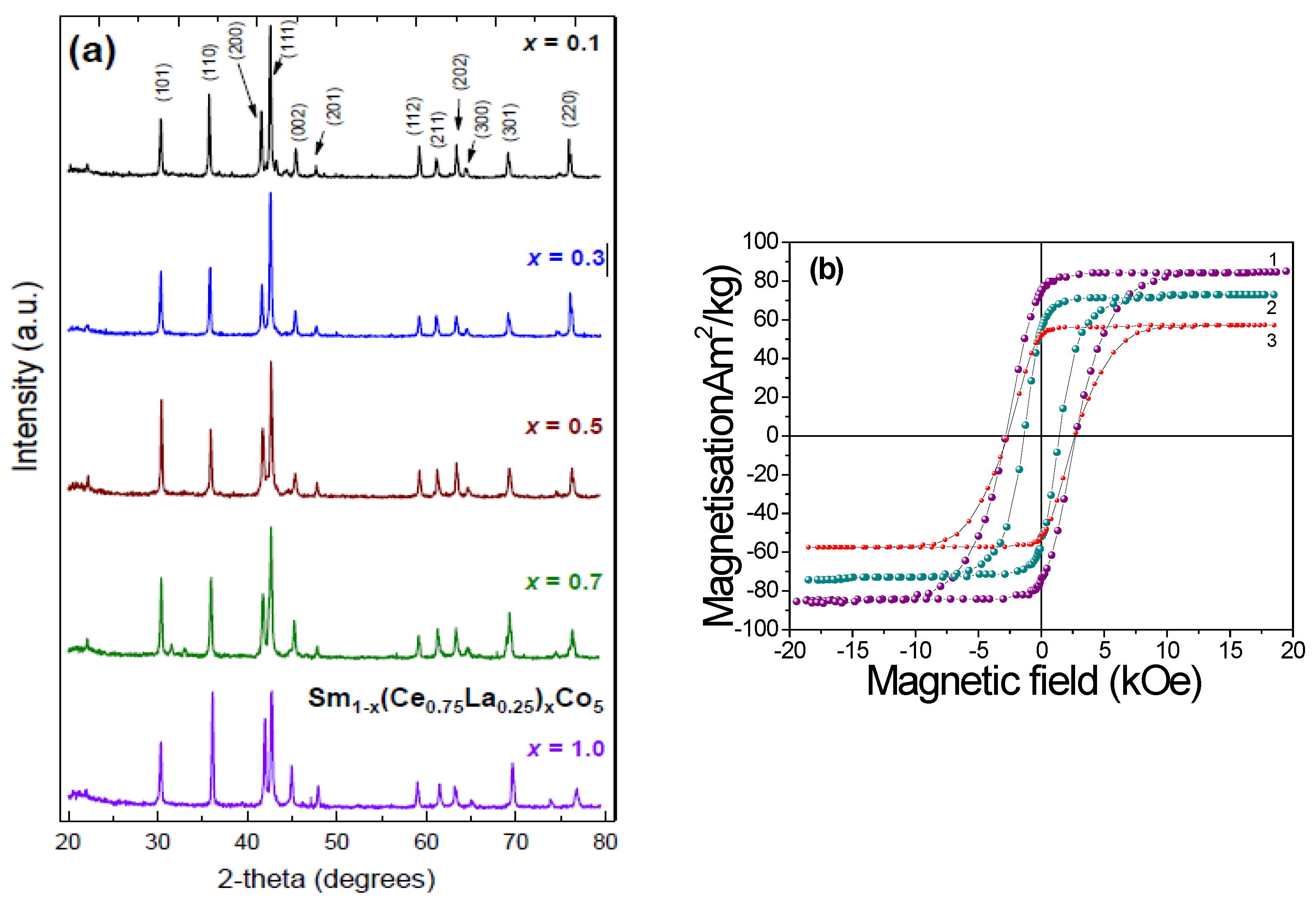

Sm

0.5MM

0.5Co

5 was also synthesized experimentally yielding a relatively high Curie temperature of 828K and fair saturation magnetization of about 61 Am

2/kg (

Figure 9). X-ray diffraction patterns (Cu Kα radiation) of Sm

1-xMM

xCo

5 samples and RT hysteresis loops of Sm

0.5Mm

0.5(CoFeNi)

5 are shown in the

Figure 9. The whole range of synthesized (SmMm)Co

5 alloys exhibit uniaxial magnetocrystalline anisotropy and hard magnetic properties. The experimental value for magnetization is lower than theoretical calculations, a rather expected result, due to minor defects of samples. The feasibility of the misch metal introduction in SmCo

5 system was confirmed both experimentally and theoretically; considering that MM is much cheaper than Sm this material could serve as a possible candidate for applications in the “gap” performance region we have described earlier.

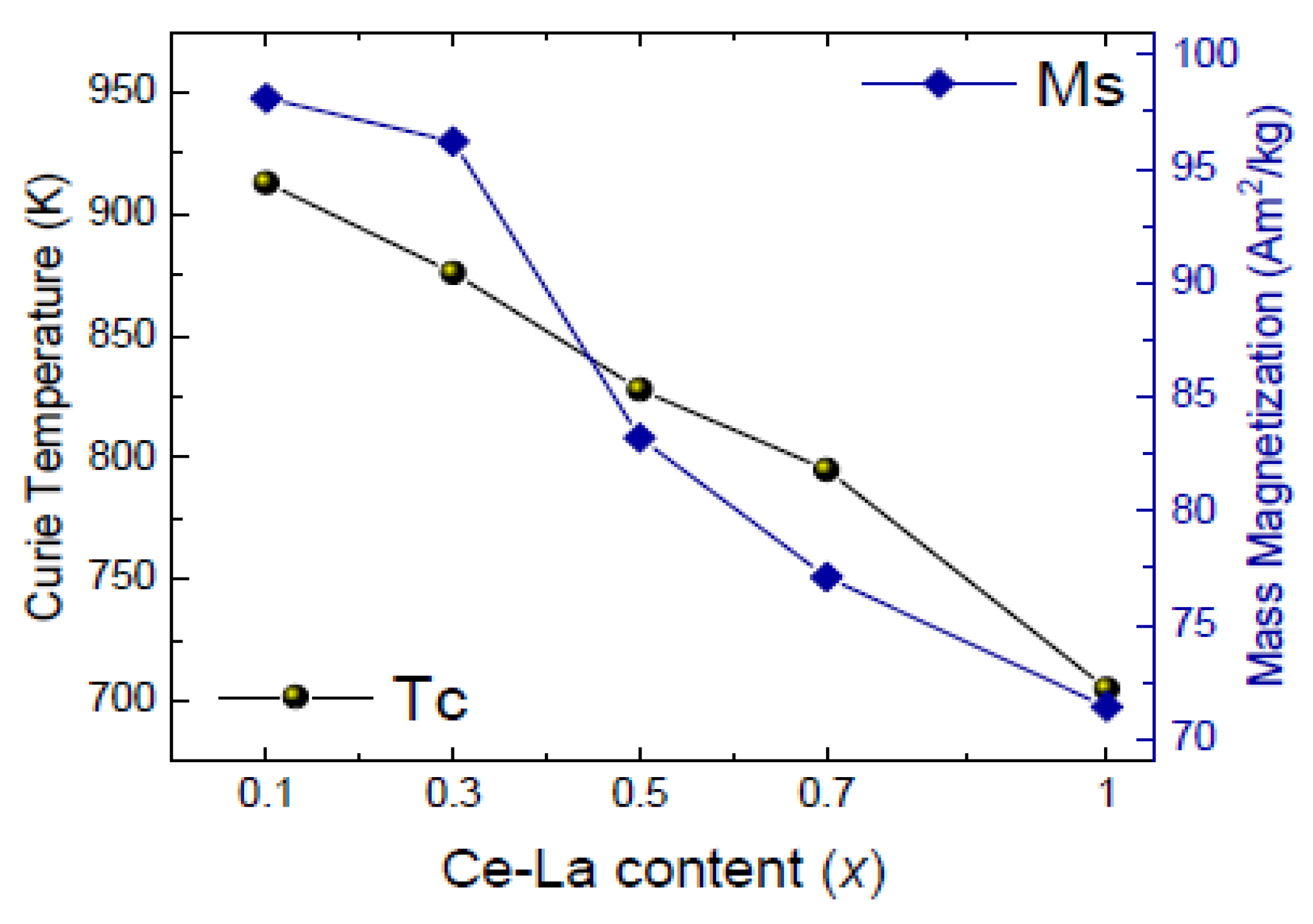

Curie temperature and mass magnetization both drop about 30% from SmCo

5 to MMCo

5, almost linearly, with the compounds with 30% substitution still presenting almost all the SmCo

5 basic compound’s potential; Curie temperature of Sm

0.7(Ce-La)

0.3Co

5 was measured at 876 K and mass magnetization at 96 Am

2/kg (

Figure 10). For high Ce

3La content the Th

2Ni

17-type phase is also found. Due to their large crystallographic similarity, the latter can be considered as a derivative of the original CaCu

5-type structure by replacing 1/3 of the rare earth atoms with pairs of transition metal atoms, here Co, arranged along c-axis. These pairs are called dumbbells. All SmCo

5 derivatives must

satisfy Stadelmaier’s criterion, one crystallographic unit cell must obey the equation 𝑝der ≈ (1:5)∙√3, in this case is the a-axis on the basal hexagonal plane [76].

Ab-initio theoretical calculations confirmed the most important results, with the important exception of magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy. Magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy cannot be predicted correctly in conjunction with atomic magnetic moments, using the same potential within relativistic linearized augmented plane wave (FLAPW) approach; a selection of U above 5 eV predicts magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy close to the experimental values (10-15 meV) but leads to a discrepancy of more than 2 Bohr magnetrons in atomic magnetic moment. On the other hand, o lower selection for U in the vicinity of 4 meV predicts accurately the atomic magnetic moments while significantly overcalculating magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy [73,77,78,79,80,81,82,83].

More complicated stoichiometries, in the vicinity of high entropy alloys’ region, Sm1-xMMxCo5-y-zFeyNiz (x = 0 – 0.7; y = 0.5 – 1.5; z = 0.5 – 1) have also been synthesized and studied both experimentally and theoretically by computational methods [75]. The introduction of Fe and Ni simultaneously with Mm did not seem to fully stabilize the hexagonal CaCu5-type structure for very high Ce3La misch metal contents. Practically single-phase samples have been acquired for 50% replacement of Sm by misch metal and 20% substitution of Co by Fe and Ni in equal concentration. Magnetic properties are weakened but slower than the reduction of cost, Sm0.5Mm0.5Co4Fe0.5Ni0.5 compound presents a mass magnetization of 85 Am2/kg which is reasonably close to the value of the mother compound. Ab-initio calculations confirm experimental results, the usual higher estimation of magnetization is still present. A positive effect of Ni in the overall thermodynamic stability of the material was observed theoretically, with the trade-off of negative effect in magnetic properties.

4. Discussion

This review presents the progress on modification of SmCo5 -type alloys suitable for permanent magnets. SmCo5 is the second strongest class of SmCo5 permanent magnets which exhibit enormous uniaxial magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy and a high Curie temperature.

A way to produce new low-cost SmCo5-type compounds is chemical modification, reducing the Co content by substitution with lower-cost elements, or replacing Sm with abundances greater than their demand. Important instrument to achieve these goals are theoretical calculations in predicting the possible stable alloys and their magnetic properties. Partial substitution of Co with d-block elements ( Sc, Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, and Zn was largely studied. CaCu5-type structure can be stabilized by replacing Co with a limited amount of Fe or Cu or both of them, mainly in SmCo1-xMx (M=Fe, Cu) ribbons. Depending from the way of preparation, different magnetic properties of SmCo1-xMx are reported. The coercivity and magnetization increases for small Fe or Cu atom substitution, then decreases rapidly. SmCo1-xFex ribbons when crystallized on single CaCu5 type phase exhibit a coercivity up to 14 kOe, which was gradually decreased when Fe content increased from x = 0.6 to 1.0. SmCo1-xCux exhibit a much higher coercivity, reaching a value of 27 kOe in the composition range from x = 0.6 to 0.8. However the nonmagnetic atom Cu decrease drastically the magnetization and the Curie temperature.

Researchers often use expensive methods such as induction melting or arc melting in the range of 1300–1400 °C, then annealing the samples at high-temperature. A recent work deal with these problems using a reduction diffusion to synthesis, having energy and time efficient as compared to the regular physical methods. After substitution at “2c” site in the SmCo5 crystal lattice, Cu almost blocked the coupling in the surrounding. As a result of decoupling in the crystal lattice, the magnetic moment reduces, while the anisotropy energy and coercivity were enhanced. The cost of this magnets decreases, but the coercivity reach a modest value of ~7 kOe

The partial substitution of Co with p elements Al, B, Ga… for Co in RCo5 (R=Y, Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb) alloys influences their magnetic properties and structure. The RCo4B alloys crystallize in the hexagonal CeCo4B type structure (space group P6/mmm). Although the saturation magnetization Ms and Tc were decreased upon B substitution for Co, SmCo4B compound still possesses excellent magnetic properties and is promising for permanent magnet applications. In contrast, the substitution of Co by Ga and Al Co in the RCo5 compound maintains the CaCu5-type structure of RCo5.

The effect of Ni substitution of Co on the crystal structure of SmCo5 has been investigated by computational methods. The energetically favorable atomistic configurations of SmCo5-xNix were found. However, these configuration does not exhibit the maximum magnetization. Replacement of Co by Ni in the SmCo5 system does not favor maximum magnetization, while the replacement of Fe by Co the SmCo5 system is unstable. This controversy was recently addressed by two theoretical studies, where a new stable and efficient SmCoNiFe3 permanent magnet was proposed. The magnetic properties of the predicted SmCoNiFe3 (energy product, Tc, Ms) are better than the corresponding properties of Nd2F14B magnet types. Therefore, SmCoNiFe3 can potentially replace SmCo5 or Nd-Fe-B types in many applications. Despite the efforts, the experimental synthesis of this predicted magnet has not yet been reported.

The introduction of Ce and La in SmCo5 system has attracted attention as early as the discovery of the initial compound. Lately, a recent series of theoretical as well as experimental studies developed the possibility of simultaneously introducing metallic Ce-La at a Ce:La ratio of 3:1 into the SmCo5 system and reducing the Co content. The theoretical framework of the compounds and the relevant ab-initio parameters were also intensively investigated. Preliminary calculations showed that the case of 50% replacement of Sm by Ce3La misch metal was of specific interest.

The simultaneously replacement of Sm by 50% Mm and 20% substitution of Co by Fe and Ni in equal concentration seems stabilize the hexagonal CaCu5-type structure and practically acquiring a single-phase samples. The partial replacement of an expensive rare earth element by a less expensive one may establish a material which could be used as the basis for a “gap” magnet and may find potential use in applications with low cost.

There is still room in the research field to modify the SmCo5 alloys. Modification of RCo4B by replacing Co with another transition metal or non-transition metal or /and Mm Ce-La could lead to new alloys with low cost and good magnetic properties. The processing of Sm-Mm-Co-M is also an open field of research to produce low cost permanent magnet.

Supplementary Materials

VESTA computer program was applied to visualize the structures of SmCo5 and SmCo4B [84].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and original draft preparation by Margarit Gjoka, resources, writing, review and editing by Margarit Gjoka and Charallampos Sarafidis.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- R. Gauß, C. Burkhardt, F. Carencotte, M. Gasparon, O. Gutfleisch, I. Higgins, M. Karajić, A. Klossek, M. Mäkinen, B. Schäfer, R. Schindler, B. Veluri, Rare Earth Magnets and Motors: A European Call for Action. A report by the Rare Earth Magnets and Motors Cluster of the European Raw Materials Alliance. Berlin 2021.

- M.A. Willard, E. Brück, C.H. Chen, S.G. Sankar, J.P. Liu, Magnetic materials and devices for the 21st century: Stronger, lighter, and more energy efficient, Adv. Mater. 23 (2011) 821–842. [CrossRef]

- X. Du, X., T.E. Graedel, Global Rare Earth In-Use Stocks in NdFeB Permanent Magnets. Journal of Industrial Ecology. 15, 836–843 (2011). [CrossRef]

- R. Skomski, Permanent magnets: History, current research, and outlook. In: Springer Series in Materials Science. pp. 359–395. Springer Verlag (2016).

- J. M. D. Coey, Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2009.

- K. Strnat, G. Hoffer, J. Olson, W. Ostertag, J.J. Becker, A Family of New Cobalt-Base Permanent Magnet Materials, J. Appl. Phys. 38 (1967) 1001–1002. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Strnat, Rare-earth magnets in present production and development, J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 7, 351 (1978).

- K. J. Strnat and R. M. W. Strnat, Rare earth-cobalt permanent magnets, J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 100, 38 (1991).

- K. Kumar, RETM5 and RE2TM17 permanent magnets development, J. Appl. Phys. 63, R13 (1988).

- M. H. Walmer, J. F. Liu, and P. C. Dent, Current status of permanent magnet industry in the United States, in Proceedings of 20th International Workshop.

- A. M. Duerrschnabel, M. Yi, K. Uestuener, M. Liesegang, M.Katter, H.-J. Kleebe, B. Xu, O. Gutfleisch, and L. Molina-Luna, Atomic structure and domain wall pinning in samarium-cobalt based permanent magnets, Nat. Commun. 8, 54 (2017).

- K.P.P. Skokov, O. Gutfleisch, Heavy rare earth free, free rare earth and rare earth free magnets - Vision and reality, Scr. Mater. 154 (2018) 289–294. [CrossRef]

- J.M.D. Coey, Perspective and Prospects for Rare Earth Permanent Magnets, Engineering. 6 (2020) 119–131. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, A. Walton, R. Sheridan, K. Güth, R. Gauß, O. Gutfleisch, M. Buchert, B.-M. Steenari, T. Van Gerven, P.T. Jones, K. Binnemans, REE Recovery from End-of-Life NdFeB Permanent Magnet Scrap: A Critical Review, J. Sustain. Metall. 3 (2017) 122–149. [CrossRef]

- R. Skomski and J.M. D. Coey, Permanent Magnetism (Institute of Physics, Bristol, 1999).

- R. Skomski, Nanomagnetics, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 15,R841 (2003).

- M. S. Walmer, C. H. Chen and M. H. Walmer, "A new class of Sm-TM magnets for operating temperatures up to 550/spl deg/C," in IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, vol. 36, no. 5, pp. 3376-3381, Sept 2000. [CrossRef]

- R. Skomski, P. Manchanda, P. Kumar, B. Balamurugan, A. Kashyap, and D. J. Sellmyer, Predicting the future of permanent-magnet materials (invited), IEEE Trans. Magn. 49, 3215 (2013).

- N. Rosner, D. Koudela, U. Schwarz, A. Handstein, M. Hafland, I. Opahle, K. Koepernik, M.D. Kuz’min, K.-H. Müller, J.A. Mydosh, M. Richter, Nat. Phys. 2.

- A. Landa, P. Söderlind, D. Parker, D. Åberg, V. Lordi, A. Perron, P.E.A. Turchi, R.K. Chouhan, D. Paudyal, T.A. Lograsso], Thermodynamics of SmCo5 compound doped with Fe and Ni: An ab initio study, Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 765 (2018)659-663].

- K. Strnat, The recent development of permanent magnet materials containing rare earth metals, IEEE Trans. Magn. 6, 182 (1970).

- J. M. D. Coey, Hard magnetic materials: A perspective, IEEE Trans. Magn. 47, 4671 (2011). J. M. D. Coey, Permanent magnets: Plugging the gap, Scr. Mater. 67, 6, 524-529 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Gutfleisch, O., Willard, M.A., Brück, E., Chen, C.H., Sankar, S.G., Liu, J.P. Advanced Materials. 23, 821 (2011).

- T. Miyazaki, M. Takahashi, Y. Xingbo, H. Saito, M. Takahashi, Formation and magnetic properties of metastable (TM)5Sm and (TM)7Sm2 (TM = Fe,Co) compounds, J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 75 (1-2) (1988) 123–129. [CrossRef]

- T. Miyazaki, M. Takahashi, X. Yang, H. Saito, M. Takahashi, Formation of metastable compounds and mag- netic properties in rapidly quenched Sm (Fe1-xCox)5 and Sm2(Fe1-xCox)7 alloy systems, J. Appl. Phys. 64 (1988) 5974.

- Tetsuji Saito, Daisuke Nishio-Hamane, Magnetic properties of SmCo5-xFex (x = 0–4) melt-spun ribbon, Journal of Alloys and Compounds 585 (2014) 423–427].

- Bhaskar Das, Renu Choudhary, Ralph Skomski et al., Anisotropy and orbital moment in Sm-Co permanent magnets PHYSICAL REVIEW B 100, 024419 (2019).

- Liu, X. B., & Altounian, Z. (2011). Magnetic moments and exchange interaction in Sm(Co,Fe)5 from first-principles. Computational Materials Science, 50(3), 841–846. [CrossRef]

- Rajiv K. Chouhana, A.K. Pathakc, D. Paudyald, Review Articles Understanding the origin of magneto-crystalline anisotropy in pure and Fe/ Si substituted SmCo5 Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 522(2021)167549.

- E. A. Nesbitt;R. H. Willens;R. C. Sherwood; E. Buehler; J. H. Wernick NEW PERMANENT MAGNET MATERIALS, Appl. Phys. Lett. 12, 361–362 (1968). [CrossRef]

- F. Hofer, "Physical metallurgy and magnetic measurements of SmCo5-SmCu5 alloys," in IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 221-224, June 1970. [CrossRef]

- Toshikazu Katayama and Tsugio Shibata 1973, Annealing Effect on Magnetic Properties of Permanent Magnet Materials Based on Sm(Co, Cu)5, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 12 319. [CrossRef]

- Kamino, K., Kimura, Y., Suzuki, T., & Itayama, Y. (1973). Variation of the Magnetic Properties of Sm (Co, Cu)5 Alloys with Temperature. Transactions of the Japan Institute of Metals, 14(2), 135–139. [CrossRef]

- B. Barbara and M. Uehara, "Anisotropy and coercivity in SmCo5-based compounds," in IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 997-999, November 1976. 19 November; 76. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Mitchell; R. A. McCurrie, Magnetic properties, microstructure, and domain structure of SmCo3.25Cu1.75, J. Appl. Phys. 59, 4113–4122 (1986). [CrossRef]

- H. Oesterreicher; F. T. Parker; M. Misroch, Giant intrinsic magnetic hardness in SmCo5−xCux, J. Appl. Phys. 50, 4273–4278 (1979). [CrossRef]

- E. Lectard, C.H. Allibert, N. Valignat, in: C.A.F. Manwaring et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Magnetic Anisotropy in Rare Earth–Transition Metal Alloys, 1994, p. 308.

- Téllez-Blanco, J. C., Grössinger, R. & Turtell, R. S. Structure and magnetic properties of SmCo5−xCux alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 281, 1–5. 1998. [CrossRef]

- Téllez-Blanco, J. C., Turtelli, R. S., Grössinger, R., Estévez-Rams, E. & Fidler, J. Giant magnetic viscosity in SmCo5−xCux alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 86, 5157–5163. 1999. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, O. Coercivity mechanism of Sm(Co, Cu)5. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids, 65(5)(2004) 907–912. [CrossRef]

- Nishida, I. & Uehara, M. Study of the crystal structure and stability of pseudo-binary compound SmCo5−xCux. J. Less Common Met. 34, 285–291. 1974. [CrossRef]

- Gabay, A. M., Larson, P., Mazi, I. I. & Hadjipanayis, G. C. Magnetic states and structural transformations in Sm(Co, Cu)5 and Sm(Co, Fe, Cu)5 permanent magnets. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 38, 1337–1341. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.K., Ngo, H.M., Kim, D. et al. Enhancement of anisotropy energy of SmCo5 by ceasing the coupling at 2c sites in the crystal lattice with Cu substitution. Sci Rep 11, 10063 (2021). [CrossRef]

- H Oesterreicher, D McNeely, Low-temperature magnetic studies on various substituted rare earth (R)-transition metal (T) compounds RT5, Journal of the Less Common Metals, Volume 45, Issue 1,1976,Pages 111-116. [CrossRef]

- Fei Mao, Hao Lu, Dong Liu, Kai Guo, Fawei Tang, Xiaoyan Song, Structural stability and magnetic properties of SmCo5 compounds doped with transition metal elements, Journal of Alloys and Compounds, Volume 810,2019,151888. [CrossRef]

- A. Tawara, H. Senno, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 12 (1973) 761.

- T. Ojima, S. Tomizawa, T.Yoneyama, T. Hori, IEEE Trans. Magn.MAG-13 (1977) 1317.

- G.C. Hadjipanayis, A.M. Gabay, Proc. Inter. Workshop on high performance magnets and their applications HPMA-04, Annecy, France, vol. 2, 2004, p. 590.

- K. Suresh, R. Gopalan, G. Bhikshamaiah, et al, Phase formation, microstructure and magnetic properties investigation in Cu and Fe substituted SmCo5 melt-spun ribbons, Journal of Alloys and Compounds 463 (2008) 73–77.

- Zhou, J., Skomski, R., Chen, C., Hadjipanayis, G. C., & Sellmyer, D. J. (2000). Sm–Co–Cu–Ti high-temperature permanent magnets. Applied Physics Letters, 77(10), 1514–1516. [CrossRef]

- Cyril Chacon, Olivier Isnard, Magnetic Properties of the RCo4B Compounds (R=Y, Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb), Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 154(1)(2000)242-245. [CrossRef]

- C. Zlotea, O. Isnard, Neutron powder diffraction and magnetic phase diagram of RCo Ga4 compounds (R5Y and Pr), Journal of Alloys and Compounds 346 (2002) 29–37.

- C. Zlotea and O. Isnard, Structural and magnetic properties of RCo4Al compounds (R= Y, Pr), C Zlotea, O Isnard - J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 242–245 (832)2002.

- C. Zlotea, O Isnard Neutron diffraction and magnetic investigations of the TbCo4M compounds (M= Al and Ga), J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 14, (2002)10211.

- Y. B. Kuz’ma and N. S. Bilonzhko, Sov. Phys. Crystallogr. 18, 447 (1974).

- A. Laslo, C.V. Colin, O. Isnard, M. Guillot, Effect of the M/Co substitution on magnetocrystalline anisotropy and magnetization in SmCo5-xMx compounds (M=Ga, Al), J. Appl. Phys. 107 (2010) 09A732.

- Tian-Yu Liu, Si-Yi Chen, Shu Wang, Li-Zhu Wang, Ji-Bing Sun, Yan-Fei Jiang, Effect of annealing on the structure and magnetic properties of SmCo5-based ribbons with Al-Cu-Fe addition, Materials Letters, Volume 286, 2021, 129237. [CrossRef]

- Zhixin Dong, Shu Wang, Siyi Chen, Yunfei Cao, Zihui Ge, Jibing Sun, Effect of Al82.8Cu17Fe0.2 alloy doping on structure and magnetic properties of SmCo5-based ribbons, Journal of Rare Earths, Volume 40, Issue 1,2022,Pages 93-101. [CrossRef]

- E. Antoniou, G. Sempros, M. Gjoka, C. Sarafidis, H.M. Polatoglou, J. Kioseoglou, Structural and magnetic properties of SmCo5−XNix intermetallic compounds, Journal of Alloys and Compounds, Volume 882, 2021,160699. [CrossRef]

- J. M. D. Coey, Hard magnetic materials: A perspective, IEEE Trans. Magn. 47, 4671 (2011).

- T. Saito, D. Nishio-Hamane, Synthesis of SmFe5 intermetallic compound, AIP Adv. 10 (2020). [CrossRef]

- P. Söderlind, A. Landa, I. L. M. Locht et al., Prediction of the new efficient permanent magnet, Phys. Rev. B 96, 2017 100404(R),SmCoNiFe3. [CrossRef]

- A. Landa, P. Söderlind, D. Parker et al., Thermodynamics of SmCo5 compound doped with Fe and Ni: An ab initio study, Journal of Alloys and Compounds,765(2018)659-663. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q., Kleppa, O.J. Standard enthalpies of formation for some samarium alloys, Sm + Me (Me = Ni, Rh, Pd, Pt), determined by high-temperature direct synthesis calorimetry. Metall Mater Trans B 29, 815–820 (1998). [CrossRef]

- F. Meyer-Liautaud, C.H. Allibert, R. Castanet, Enthalpies of formation of SmCo alloys in the composition range 10–22 at. % Sm, Journal of the Less Common Metals, 127 (1987)243-250. [CrossRef]

- S. Gavrikov, D. Yu Karpenkov, M. V. Zheleznyi et al, Effect of Ni doping on stabilization of Sm(Co1−xFex)5 compound: thermodynamic calculation and experiment, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 32 (2020) 425803. [CrossRef]

- G. Sempros; Ch, Sarafidis; S. Giaremis; J. Kioseoglou; M. Gjoka, Cost effective modification of SmCo5-type alloys Special Collection: 15th Joint MMM-Intermag Conference AIP Advances 12, 035343 (2022). [CrossRef]

- S.-L. Liu, H.-R. Fan, X. Liu, J. Meng, A.R. Butcher, L. Yann, K.-F. Yang, X.-C. Li, Global rare earth elements projects: New developments and supply chains, Ore Geol. Rev. 157 (2023) 105428. [CrossRef]

- K. Binnemans, P. T. Jones, T. Müller, L. Yurramendi, Rare Earths and the Balance Problem: How to Deal with Changing Markets? J. Sustain. Met. 2018, 4, 126–146. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, W. Liu, S. Zha, Y. Li, Y. Wang, D. Zhang, M. Yue, J. Zhang, Effects of lanthanum substitution on microstructures and intrinsic magnetic properties of Nd-Fe-B alloy. Journal of Rare Earths. 33, 961–964 (2015). [CrossRef]

- W. Tang, S. Zhou, R. Wang, Preparation, and microstructure of La-containing R-Fe-B permanent magnets. J. Appl. Phys. 65, 3142–3145 (1989). [CrossRef]

- M. G. Benz and D. L. Martin, Cobalt Mischmetal Samarium Permanent Magnet Alloys, J. Appl. Phys. 42 (1971) 1534. [CrossRef]

- M. Gjoka, G. Sempros, S. Giaremis, J. Kioseoglou and C. Sarafidis, On Structural and Magnetic Properties of Substituted SmCo5 Materials, Materials 16 (2023) 547. [CrossRef]

- M. Gjoka, C. Sarafidis, G. Sempros, S. Giaremis, J. Kioseoglou, Effect of Mischmetal (MM) and transition metal elements (TM) doped on properties of the SmCo5 intermetallics, Abstracts book, First International Conference of National Institute of Physics (NIP), Academy of Sciences of Albania, 2022 page 24.

- S. Giaremis, G. Katsikas, G. Sempros, M. Gjoka, C. Sarafidis and J. Kioseoglou, Ab initio, artificial neural network predictions and experimental synthesis of mischmetal alloying in Sm–Co permanent magnets, Nanoscale 14 (2022) 5824. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Cadogan, H. S. Li, A. Margarian, J. Dunlop, D. H. Ryan, S. J. Collocott, R. L. Davis, New rare-earth intermetallic phases R3(Fe,M)29-X: (R=Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd; M=Ti, V, Cr, Mn; and X=H, N, C), J. Appl. Phys. 76 (1994) 6138. [CrossRef]

- G. Kresse, D. Joubert, From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 59 (1999) 1758–1775. [CrossRef]

- Y. P. Irkhin, V. Y. Irkhin, The anion and cation effects in the magnetic anisotropy of rare-earth compounds: Charge screening by conduction electrons. Phys. Solid State 42 (2000) 1087–1093. [CrossRef]

- C. H. Chen, M. S. Walmer, M. H. Walmer, W. Gong, B. M. Ma, The relationship of thermal expansion to magnetocrystalline anisotropy, spontaneous magnetization, and Tc for permanent magnets. J. Appl. Phys. 85 (1999) 5669–5671. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Nguyen, Y. Yao, C. Z. Wang, K. M. Ho, V. P. Antropov, Magnetocrystalline anisotropy in cobalt based magnets: A choice of correlation parameters and the relativistic effects. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 30 (2018) 195801. [CrossRef]

- P. Larson, Ι. Ι. Mazin, D. A. Papaconstantopoulos, Calculation of magnetic anisotropy energy in SmCo5. Phys. Rev. B 67 (2003) 214405. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Nguyen, Y. Yao, C. Z. Wang, K. M. Ho, V. P. Antropov, Magnetocrystalline anisotropy in cobalt based magnets: A choice of correlation parameters and the relativistic effects. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 30 (2018) 195801. [CrossRef]

- P. Larson, Ι. Ι. Mazin, D. A. Papaconstantopoulos, Calculation of magnetic anisotropy energy in SmCo5. Phys. Rev. B 67 (2003) 214405. [CrossRef]

- K. Momma and F. Izumi, "VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data," J. Appl. Crystallogr., 44, 1272-1276 (2011). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).