Submitted:

02 January 2024

Posted:

03 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Fermented food microbial profile, function and bioactive compounds

2.1. Microbial profile and function

2.2. Detection of bioactive compounds in fermented food

| Fermented food | Isolated microorganisms | Properties | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Koumiss | Lactobacilluscoryniformis, L. paracasei, L. kefiranofaciens L. curvatusL.fermentum,L. casei, L. helveticus, L. plantarum |

|

[1] |

| Kimchi | L. casei DK128 |

|

[2] |

| Jiangshui | Lactobacillus, Limosilactobacillus fermentum, and L. bacilli |

|

[3] |

| Yogurt | Bifidobacterium animalis |

|

[4,5] |

| Kefir |

L. acidophilus, L. bulgaricus, S. thermophilus, L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. jensenii, L. rhamnosus |

|

[4] |

| Mango pickle, Naan | Indigenous microflora, yeast |

|

[6] |

| Sourdough (Khamir) | Enterococcus mundtii, and Wickerhamomyces anomalus, Bacillus subtilis LZU-GM |

|

[7,8] |

| Fermented milk, | Acinetobacter, Enterobacteriaceae, and Aeromonadaceae |

|

[9] |

| Shubat and Ayran | Leuconostoc and Enterococcusgenera | Bile salt is tolerated and antibodies are susceptible | [10] |

| PaoCai | Enterococcus faecalis, Lactococcus lactis, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, L. plantarum, L. casei and L. zeae |

|

[11] |

| Fermented Portuguese olive | L. plantarum and L. paraplantarum |

|

[12,13] |

| Koumiss |

L. helveticus and L. delbrueckii |

|

[14] |

| Raw camel milk | L. fermentum, L. plantarum, L. casei, Lactococcus lactis, Enterococcus faecium, and Streptococcus thermophiles |

|

[15] |

| Pickle and cucumber |

|

[6] | |

| Tarhana | Streptococcus thermophilus, L. fermentum, Enterococcus faecium, Pediococcus pentosaceus, Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides, Weissella cibaria, L. plantarum, L.delbrueckii, Leuconostoc citreum, L. paraplantarum and L. casei. |

|

[16] |

| Meju, Doenjang, Jeotgal, and Mekgeolli | Leuconostoc mesenteroides, L. plantarum, Aspergillus, Bacillus, Bacillussiamensis, Halomonas sp., Kocuria sp., and Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

|

[17] |

| Dhokla | L. plantarum and Weissella cibaria |

|

[18] |

| Cheese |

L. lactis L. delbrueckiiL. helveticus, L. casei, L. plantarum, L. salivarius, Leuconostoc spp., Strep. thermophilus, Ent. durans, Ent. faecium, Staphylococcus Brevibacterium linens, Propionibacterium freudenreichii, Debaryomyces hansenii, Geotrichum candidum, Penicillium camemberti, P. roqueforti |

|

[19,20,21] |

| Pla-khao-sug | Ped. cerevisiae, L. brevis, Staphylococcus sp., Bacillus sp. |

|

[22] |

| Tapai Ubi |

Saccharomycopsis fibuligera, Amylomyces rouxii, Mu. circinelloides, Mu. javanicus, Hansenula spp, Rhi. arrhizus, Rhi. oryzae, Rhi. Chinensis |

|

[23,24] |

| Tungrymbai | B. subtilis, B. licheniformis, B. pumilus |

|

[25,26] |

| Thua nao | B. subtilis, B. pumilus, Lactobacillus sp. |

|

[27,28] |

| Yandou | B. subtilis | [29] | |

| Sufu | Actinomucor elenans, Mucor. silvatixus, Mu. corticolus, Mu. hiemalis, Mu. praini, Mu. racemosus, Mu. subtilissimus, Rhiz. Chinensis |

|

[30,31] |

| Miso |

Ped. acidilactici, Leuc. paramesenteroides, Micrococcus halobius, Ped. halophilus, Streptococcus sp., Sacch. rouxii, Zygosaccharomyces rouxii, Asp. Oryzae |

|

[32,33] |

| Koozh and gherkin |

Lactobacillus and Weissella |

|

[34] |

| Airag |

L. helveticus, L. kefiranofaciens, Bifidobacterium mongoliense, and Kluyveromyces marxianu |

|

[35] |

| Chhurpi |

L. farciminis, L. paracasei, L. biofermentans, L. plantarum, L. curvatus, L. fermentum, L. alimentarius, L. kefir, L. hilgardii, W. confusa, Ent. faecium, Leuc. Mesenteroides |

High contents of protein and carbohydrates while low in fat | [36,37] |

| Somar | L. paracasei, L. Lactis | [38] | |

| Boza |

Lactobacillus sp., Lactococcus sp., Pediococcus sp., Leuconostoc sp., |

Contains Biogenic amine content | [39,40] |

| Suan-tsai and fu-tsai |

Ent. faecalis, L. alimentarius, L. brevis, L. coryniformis, L. farciminis, L. plantarum, L. versmoldensis, Leuc. citreum, Leuc. mesenteroides, Leuc. pseudomesenteroides, P. pentosaceus, W. cibaria, W. paramesenteroides |

|

[41] |

| Nem-chua |

L. pentosus, L. plantarum, L. brevis, L. paracasei, L. fermentum, L. acidipiscis, L. farciminis, L. rossiae, L. fuchuensis, L. namurensis, Lc. lactis, Leuc. citreum, Leuc. fallax, P. acidilactici, P. pentosaceus, P. stilesii, Weissella cibaria, W. paramesenteroides |

Inhibit entrance of potentially pathogenic microorganisms. | [42] |

| Fermented foods | Metabolites and bioactive compounds | Techniques use | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fermented cantaloupe juice | Isoleucine, valine, lactic acid, alanine, β-alanine, sucrose, erythritol, gluconic acid, GABA, alpha-aminobutyric acid, methionine, acetoin, acetoacetate, and phenylpropanoid acid, | H NMR | [43] |

| Fermented soybeans | Glucosyringic acid, engeletin, glycitin, dihydroxy-4-phenyl coumarin, ediflavone, histidine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan | UHPLC Q-TOF MS/MS | [44] |

| Nozawana-zuke | Isothiocyanates, hexanoic acid, lactic acid, acetic acid, acetoin, and 2,3-butanedione, glutamine, valine, leucine, isoleucine, choline, and methionine | NMR, SPME-GC/MS | [45] |

| Fermented milk | Fatty acids, peptides, amino acids, carbohydrates, vitamins, aldehyde, ketone | UPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS | [46] |

| Fermented coffee brews | aromatic amino acid, catabolites, and hydroxydodecanoic acid | LC-QTOF-MS/MS | [47] |

| Fermented camel and bovine milk | Fatty acyls, benzenoids, organ heterocyclic, organic acids and derivatives, phenylpropanoids, polyketides, glycerophospholipids, sterol lipids, polyketides, prenol lipids, organic oxygen, glycerolipids, organooxygen, alkaloids and derivatives, sphingolipids, hydrocarbons, nucleosides, nucleotides, and analogues, lignans, neolignans and related compounds, organosulfur compounds, hydrocarbon derivatives, organic nitrogen compounds | UPLC-QTOF: | [48] |

| Fermented goat milk | 1-stearoyl-lysophosphatidylcholine, gaboxadol, guanine, cytosine, 4 acetamidobenzoic acid, taurochenodeoxycholic acid, 2,6-dimorpholinopyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid, D-proline, DL-Glutamic acid, O-beta-D-glucosyl-trans-zeatin, N2-1-Carboxyethyl-N5 diaminomethyleneornithine, | Q-HRMS-UPLC | [49] |

| Meju | Citric acid, pipecolic acid, glutamic acid, Isoleucine, Leucine, methionine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, proline, threonine, valine | UPLC-Q-TOF MS and PLS-DA |

[50] |

| Cereal-based fermented foods |

Volatiles (5 alcohols, 6 carbonils, dodecanoic acid, and 1,3-hexadiene) and the polyphenolic compounds gallic acid, epigallocatechin-gallate, epigallocatechin, flavonoids, protocatechuic acid, and total polyphenols |

SPME–GC | [51] |

| Soymilk fermented |

Amino acids, Organic acids, Sugars, Amines, Phenolic compounds, Lipids, Choline, Trigonelline, Pterin, 2,3-butanedione | H NMR | [52] |

| Fermented Barley | Galactosamine, Maltose, Phenylacetic acid, Cuminaldehyde, Adenosine, Glucose 1-phosphate, Cafestol, Aspartic acid, Lysine, Tryptophan, Citric acid, Glucose 6-phosphate, Methionine, Asparagine, Docosahexaenoic acid methyl ester, Histidine, tyrosine, D-glucosamine-6-phosphate, arginine, fumaric acid, benzaldehyde | UPLC-HRMS | [53] |

| Gochujangs | Amino acids, organic acids, sugar and sugar alcohol, flavonoids, soyasampnins, lipids, and alkaloids | UPLC-Q-TOF-MS | [54] |

| Dry-fermented sausages | Amino acids, peptides, and analogues; carbohydrates; organic acids and derivatives; nucleosides, nucleotides and analogues; fatty acids and miscellaneous |

1H HR-MAS NMR | [55] |

| Sunki | Amino acids, organic acids, aldoses, alditoles, and alcohol | HNMR and GC/MS | [56] |

| Koumiss | Glycerophospholipids, fatty acyls, sphingolipids, 1glycerolipids, prenol lipids, organic acids and derivatives, organic oxygen, organoheterocyclic, benzenoids, organic nitrogen compounds, phenylpropanoids and polyketides, nucleosides and analogues, alkaloids and derivative, glycerophospholipids and fatty acyls, included amino acids, carboxylic acids and derivatives, benzenoids, glycosides, organoheterocyclic compounds, glycerolipids, alcohols, lactones, carbonyl compounds |

UPLC-Q-TOF-MS | [57] |

| Fermented agent | Probiotic strains | Promotes compounds availability | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carrot pulp | L. plantarum NCU 116 | Rhamnogalacturonan-I-type polysaccharides break down | [58] |

| Semen vaccariae and Leonurus artemisia | L. casei, Enterococcus faecalis, and Candida utilis | Increasing the total flavonoids, alkaloids, crude polysaccharides, and saponins contents | [59] |

| Lespedeza cuneata | L. pentosus, | Quercetin and kaempferol contents increased | [60] |

| Daucus carota L | L. plantarum NCU116 | Effective regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism | [61]. |

| Longan pulp | L. fermentum | Lower polysaccharide molecular weight, viscosity, and particle size while higher solubility | [62]. |

| Lily bulbs | L. plantarum | β-glucans and glycans degraded into tri- and tetra-saccharides | [63] |

| Tea Plant | Saccharomyces boulardii and L. plantarum | Improves the methyl salicylate, geraniol, and 2-phenyl ethyl alcohol | [64] |

| Barley beverage | L. casei | Increase total polyphenols and flavonoid contents | [65]. |

| Lily bulbs | L. lancifolium and S. cerevisae | Increasing protein contents | [66]. |

| Puerariae radix | Bifidobactericum breve | Increase daidzein and genistein | [67] |

| Soybean | Bacillus licheniformis | Increase the insulin-sensitizing action | [68] |

| Artemisia princeps | L. plantarum SN13T | catechol and seco-tanapartholide C | [69] |

| Panax notoginseng | Streptococcus salivarius, L. helveticus, L.rhamnosus L.acidophilus , B. longum , B. catenulatum , B. breve and B. bifidum | Increased ginsenosides Rh (1) and Rg (3) | [70] |

| Artemisia princeps | L. plantarum | Produce catechol and seco-tanapartholide C, |

|

| Polygonum cuspidatum | Aspergillus niger and Yeast | Production of resveratrol | [71] |

| Radix astragalus | Aspergillus spp | 3,4-di(4′-hydroxyphenyl) isobutyric acid | [72] |

| Cordyceps militaris | Pediococcus pentosaceus | Increase β-glucan and cordycepin | [73] |

3. Probiotic fermentation increases the bioactive compound in fermented food

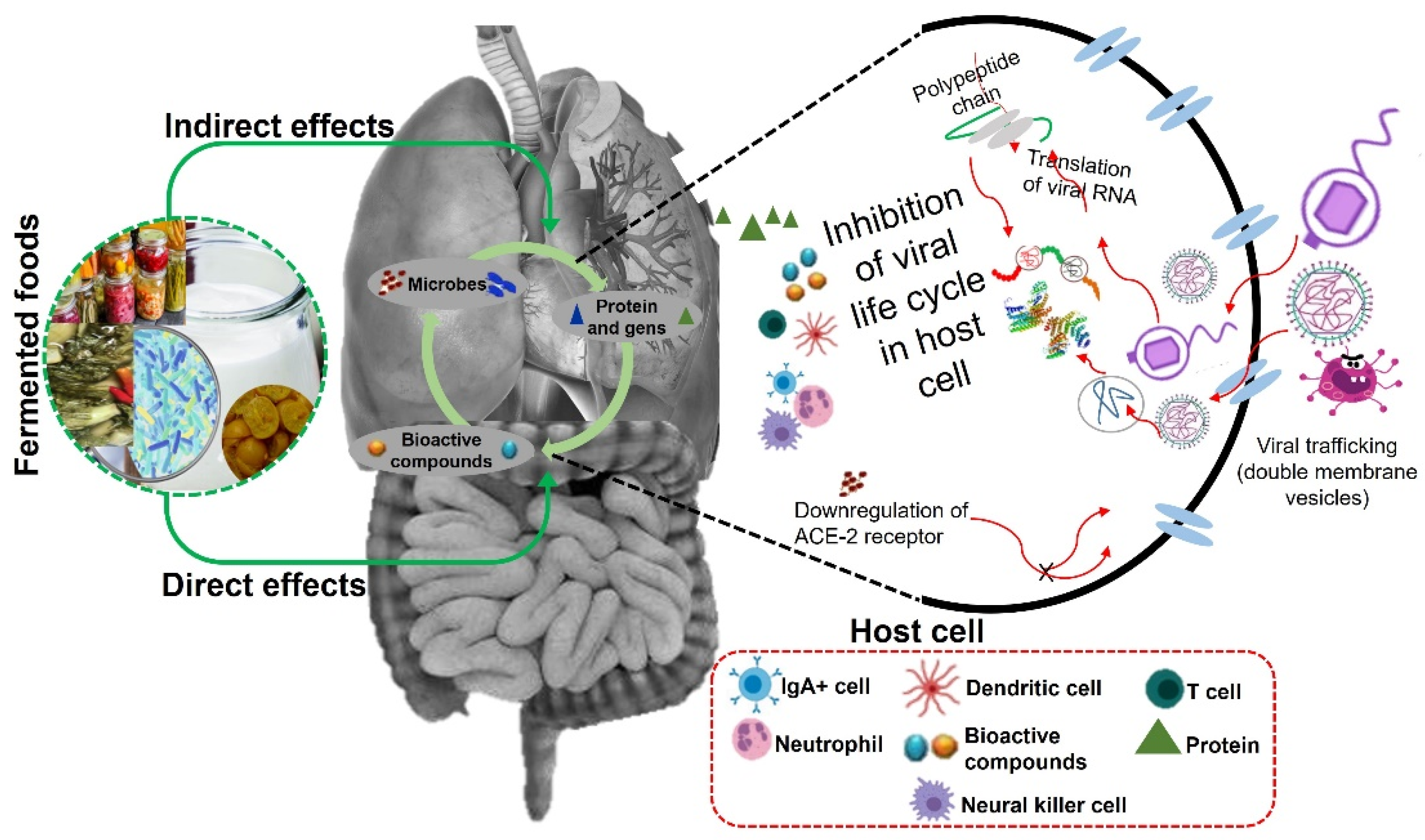

4. Antiviral function of fermented food (Figure 1)

| Antiviral agent | Target viruses | References |

|---|---|---|

| P. pentosaceus, W. cibaria, B. adolescentis | Noroviruses and, murine-1virus | [74,75] |

| L. brevis and Secoiridoid glucosides | Herpes simplex virus type 2 | [76] |

| L. acidophilus, L. rhamnosus, L.plantarum, S. thermophiles and B. bifidum, | Hepatitis C, Influenza virus, | [77,78] |

| L. acidophilus, L. reuteri and L. salivarius | avian influenza virus | [79] |

| L. plantarum, Enterococcus faeciumL3 | Influenza virus, Coxsackie virus, Echovirus E7 and E19 | [80] |

| Lactobacillus gasseri | Influenza A virus, Espiratory syncytial virus | [81] |

| L. reuteri ATCC 55730 | Coxsackieviruses CA6, and Enterovirus 71 | [82] |

| L. plantarum YU | Influenza A virus | [83] |

| L. plantarum DK119, L. gasseri SBT2055, L. casei DK128, Caffeic acid and glycyrrhizin | Influenza virus | [2,84,85] |

| Lactobacillus spp,Bifidobacteria | Vesicular stomatitis virus | [86,87] |

| Vitamin A, C D, omega-3, fatty acids, and docosahexaenoic acid | Influenza and COVID-19 | [88,89] |

| Taurine, creatine, carnosine, anserine, and 4-hydroxyproline | COVID-19 | [90] |

4.1. Inhibition of respiratory and alimentary tracts viruses’ infection

4.2. Herpes simplex virus

4.3. COVID-19

5. Fermented food safety, conclusion, and future prospective

References

- Cardoso Umbelino Cavallini, D.; Jovenasso Manzoni, M.; Bedani, R.; Roselino, M.; Celiberto, L.; Vendramini, R.; de Valdez, G.; Saes Parra Abdalla, D.; Aparecida Pinto, R.; Rosetto, D.; Roberto Valentini, S.; Antonio Rossi, E. , Probiotic Soy Product Supplemented with Isoflavones Improves the Lipid Profile of Moderately Hypercholesterolemic Men: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2016, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, X.-F.; He, S.; Feng, H.; Li, L. , Dietary supplementation of exogenous probiotics affects growth performance and gut health by regulating gut microbiota in Chinese Perch (Siniperca chuatsi). Aquaculture 2021, 737405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, J. P.; Shin, D.-H.; Jung, S.-J.; Chae, S.-W. , Functional Properties of Microorganisms in Fermented Foods. Frontiers in microbiology 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Guan, Q.; Song, C.; Zhong, L.; Ding, X.; Zeng, H.; Nie, P.; Song, L. , Regulatory effects of Lactobacillus fermented black barley on intestinal microbiota of NAFLD rats. Food Research International 2021, 147, 110467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, S. P.; Jani, K.; Sharma, A.; Anupma, A.; Pradhan, P.; Shouche, Y.; Tamang, J. P. , Analysis of bacterial and fungal communities in Marcha and Thiat, traditionally prepared amylolytic starters of India. Scientific reports 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorov, S. D.; Dicks, L. M. T. , Screening for bacteriocin-producing lactic acid bacteria from boza, a traditional cereal beverage from Bulgaria. Process Biochemistry 2006, 41, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.-J.; Hong, T.; Shi, H.-F.; Yin, J.-Y.; Koev, T.; Nie, S.-P.; Gilbert, R. G.; Xie, M.-Y. , Probiotic fermentation modifies the structures of pectic polysaccharides from carrot pulp. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 251, 117116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Xie, G.; Liu, H.; Tan, G.; Li, L.; Liu, W.; Li, M. , Fermented ginseng leaf enriched with rare ginsenosides relieves exercise-induced fatigue via regulating metabolites of muscular interstitial fluid, satellite cells-mediated muscle repair and gut microbiota. Journal of Functional Foods 2021, 83, 104509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Figueroa, J. C.; González-Córdova, A. F.; Torres-Llanez, M. J.; Garcia, H. S.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B. , Novel angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides produced in fermented milk by specific wild Lactococcus lactis strains. Journal of Dairy Science 2012, 95, 5536–5543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhialdin, B. J.; Zawawi, N.; Abdull Razis, A. F.; Bakar, J.; Zarei, M. , Antiviral activity of fermented foods and their probiotics bacteria towards respiratory and alimentary tracts viruses. Food Control 2021, 127, 108140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D. J.; Jung, D.; Jung, S.; Yeo, D.; Choi, C. , Inhibitory effect of lactic acid bacteria isolated from kimchi against murine norovirus. Food Control 2020, 109, 106881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, M.; Aida, R.; Saito, K.; Ochiai, A.; Takesono, S.; Saitoh, E.; Tanaka, T. , Identification and characterization of multifunctional cationic peptides from traditional Japanese fermented soybean Natto extracts. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2019, 127, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomas, M.; Capanoglu, E.; Bahrami, A.; Hosseini, H.; Akbari-Alavijeh, S.; Shaddel, R.; Rehman, A.; Rezaei, A.; Rashidinejad, A.; Garavand, F.; Goudarzi, M.; Jafari, S. M. , The direct and indirect effects of bioactive compounds against coronavirus. Food Frontiers 2021, 3, 96–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirashrafi, S.; Moravejolahkami, A. R.; Balouch Zehi, Z.; Hojjati Kermani, M. A.; Bahreini-Esfahani, N.; Haratian, M.; Ganjali Dashti, M.; Pourhossein, M. , The efficacy of probiotics on virus titres and antibody production in virus diseases: A systematic review on recent evidence for COVID-19 treatment. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN 2021, 46, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, D.; Rafiq, S.; Gat, Y.; Gat, P.; Waghmare, R.; Kumar, V. , A Review on Bioactive Peptides: Physiological Functions, Bioavailability and Safety. International Journal of Peptide Research and Therapeutics 2019, 26, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkor, O. N.; Henriksson, A.; Singh, T. K.; Vasiljevic, T.; Shah, N. P. , ACE-inhibitory activity of probiotic yoghurt. International Dairy Journal 2007, 17, 1321–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakerian, M.; Razavi, S. H.; Ziai, S. A.; Khodaiyan, F.; Yarmand, M. S.; Moayedi, A. , Proteolytic and ACE-inhibitory activities of probiotic yogurt containing non-viable bacteria as affected by different levels of fat, inulin and starter culture. Journal of food science and technology 2013, 52, 2428–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starosila, D.; Rybalko, S.; Varbanetz, L.; Ivanskaya, N.; Sorokulova, I. , Anti-influenza Activity of a Bacillus subtilis Probiotic Strain. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwagu, T. N.; Ugwuodo, C. J.; Onwosi, C. O.; Inyima, O.; Uchendu, O. C.; Akpuru, C. , Evaluation of the probiotic attributes of Bacillus strains isolated from traditional fermented African locust bean seeds (Parkia biglobosa), “daddawa”. Annals of Microbiology 2020, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-J.; Song, J.-H.; Ahn, Y.-J.; Baek, S.-H.; Kwon, D.-H. , Antiviral activities of cell-free supernatants of yogurts metabolites against some RNA viruses. European Food Research and Technology 2009, 228, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxha, R.; Todorov, D.; Hinkov, A.; Shishkova, K.; Evstatieva, Y.; Nikolova, D. , In Vitro Screening of Antiviral Activity of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Traditional Fermented Foods. Microbiology Research 2023, 14, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, T.; Ikari, N.; Kouchi, T.; Kowatari, Y.; Kubota, Y.; Shimojo, N.; Tsuji, N. M. , The molecular mechanism for activating IgA production by Pediococcus acidilactici K15 and the clinical impact in a randomized trial. Scientific reports 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.-n.; Han, Y.; Zhou, Z.-j. , Lactic acid bacteria in traditional fermented Chinese foods. Food Research International 2011, 44, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezac, S.; Kok, C. R.; Heermann, M.; Hutkins, R. , Fermented Foods as a Dietary Source of Live Organisms. Frontiers in microbiology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, G.; Paramithiotis, S.; Sundaram Sivamaruthi, B.; Wijaya, C. H.; Suharta, S.; Sanlier, N.; Shin, H.-S.; Patra, J. K. , Traditional fermented foods with anti-aging effect: A concentric review. Food Research International 2020, 134, 109269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Shao, Y. , Effects of microbial diversity on nitrite concentration in pao cai, a naturally fermented cabbage product from China. Food Microbiology 2018, 72, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, S.; Verón, H.; Contreras, L.; Isla, M. I. , An overview of plant-autochthonous microorganisms and fermented vegetable foods. Food Science and Human Wellness 2020, 9, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, J. P.; Watanabe, K.; Holzapfel, W. H. , Review: Diversity of Microorganisms in Global Fermented Foods and Beverages. Frontiers in microbiology 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokulich, N. A.; Ohta, M.; Lee, M.; Mills, D. A.; Björkroth, J. , Indigenous Bacteria and Fungi Drive Traditional Kimoto Sake Fermentations. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2014, 80, 5522–5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Lin, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; He, X.; Yang, P.; Zhou, J.; Guan, X.; Huang, X. , Proteomic and high-throughput analysis of protein expression and microbial diversity of microbes from 30- and 300-year pit muds of Chinese Luzhou-flavor liquor. Food Research International 2015, 75, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Hagelsieb, G.; Marzano, M.; Fosso, B.; Manzari, C.; Grieco, F.; Intranuovo, M.; Cozzi, G.; Mulè, G.; Scioscia, G.; Valiente, G.; Tullo, A.; Sbisà, E.; Pesole, G.; Santamaria, M. , Complexity and Dynamics of the Winemaking Bacterial Communities in Berries, Musts, and Wines from Apulian Grape Cultivars through Time and Space. PloS one 2016, 11, e0157383. [Google Scholar]

- Thanh, V. N.; Thuy, N. T.; Chi, N. T.; Hien, D. D.; Ha, B. T. V.; Luong, D. T.; Ngoc, P. D.; Ty, P. V. , New insight into microbial diversity and functions in traditional Vietnamese alcoholic fermentation. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2016, 232, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinl, S.; Grabherr, R. , Systems biology of robustness and flexibility: Lactobacillus buchneri —A show case. Journal of Biotechnology 2017, 257, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soedamah-Muthu, S. S.; de Goede, J. , Dairy Consumption and Cardiometabolic Diseases: Systematic Review and Updated Meta-Analyses of Prospective Cohort Studies. Current Nutrition Reports 2018, 7, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shori, A. B. , Camel milk and its fermented products as a source of potential probiotic strains and novel food cultures: A mini review. PharmaNutrition 2017, 5, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, E.; Abdollahzad, H.; Pasdar, Y.; Rezaeian, S.; Moludi, J.; Nachvak, S. M.; Mostafai, R. Relationship Between the Consumption of Milk-Based Oils Including Butter and Kermanshah Ghee with Metabolic Syndrome: Ravansar Non-Communicable Disease Cohort Study. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy 2020, 13, 1519–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, A.; Irisawa, T.; Dicks, L.; Tanasupawat, S. FERMENTED FOODS | Fermentations of East and Southeast Asia. 2014, 846–851. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, M. L.; Hou, H. M.; Teng, X. X.; Zhu, Y. L.; Hao, H. S.; Zhang, G. L. , Microbial diversity in raw milk and traditional fermented dairy products (Hurood cheese and Jueke) from Inner Mongolia, China. Genetics and Molecular Research 2017, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cagno, R.; Coda, R.; De Angelis, M.; Gobbetti, M. , Exploitation of vegetables and fruits through lactic acid fermentation. Food Microbiology 2013, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamimura, B. A.; De Filippis, F.; Sant’Ana, A. S.; Ercolini, D. , Large-scale mapping of microbial diversity in artisanal Brazilian cheeses. Food Microbiology 2019, 80, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Menghe, B.; Wu, J.; Guo, M.; Zhang, H. , Isolation and preliminary probiotic selection of lactobacilli from koumiss in Inner Mongolia. Journal of Basic Microbiology 2009, 49, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, T.; Guan, Q.; Song, S.; Hao, M.; Xie, M. , Dynamic changes of lactic acid bacteria flora during Chinese sauerkraut fermentation. Food Control 2012, 26, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakandar, H. A.; Zhang, H. , Trends in Probiotic(s)-Fermented milks and their in vivo functionality: A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 110, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Eslami, M.; Yousefi, B.; Kokhaei, P.; Jazayeri Moghadas, A.; Sadighi Moghadam, B.; Arabkari, V.; Niazi, Z. , Are probiotics useful for therapy of Helicobacter pylori diseases? Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2019, 64, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suez, J.; Zmora, N.; Segal, E.; Elinav, E. , The pros, cons, and many unknowns of probiotics. Nature Medicine 2019, 25, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.-J.; Lee, Y.-T.; Ngo, V. L.; Cho, Y.-H.; Ko, E.-J.; Hong, S.-M.; Kim, K.-H.; Jang, J.-H.; Oh, J.-S.; Park, M.-K.; Kim, C.-H.; Sun, J.; Kang, S.-M. , Heat-killed Lactobacillus casei confers broad protection against influenza A virus primary infection and develops heterosubtypic immunity against future secondary infection. Scientific reports 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ye, Z.; Feng, P.; Li, R.; Chen, X.; Tian, X.; Han, R.; Kakade, A.; Liu, P.; Li, X. , Limosilactobacillus fermentum JL-3 isolated from “Jiangshui” ameliorates hyperuricemia by degrading uric acid. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1897211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.-J.; Tang, X.-D.; Yu, J.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Li, X.-R. , Gut microbiota alterations from different Lactobacillus probiotic-fermented yoghurt treatments in slow-transit constipation. Journal of Functional Foods 2017, 38, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzawa, D.; Mawatari, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Genda, T.; Takahashi, S.; Nishijima, T.; Kamasaka, H.; Suzuki, S.; Kuriki, T. , Effects of synbiotics containing Bifidobacterium animalis subsp.lactis GCL2505 and inulin on intestinal bifidobacteria: A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Food Science & Nutrition 2019, 7, 1828–1837. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, S.; Hussain, M.; Ismail, T.; Riaz, M. , Ethnic Fermented Foods of Pakistan. 2016, 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Sakandar, H. A.; Usman, K.; Imran, M. , Isolation and characterization of gluten-degrading Enterococcus mundtii and Wickerhamomyces anomalus, potential probiotic strains from indigenously fermented sourdough (Khamir). Lwt 2018, 91, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Li, S.; Han, H.; Jin, W.-L.; Ling, Z.; Ji, J.; Iram, S.; Liu, P.; Xiao, S.; Salama, E.-S.; Li, X. , A gluten degrading probiotic Bacillus subtilis LZU-GM relieve adverse effect of gluten additive food and balances gut microbiota in mice. Food Research International 2023, 112960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahidul-Islam, S. M.; Kuda, T.; Takahashi, H.; Kimura, B. , Bacterial and fungal microbiota in traditional Bangladeshi fermented milk products analysed by culture-dependent and culture-independent methods. Food Research International 2018, 111, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhadyra, S.; Han, X.; Anapiyayev, B. B.; Tao, F.; Xu, P. , Bacterial diversity analysis in Kazakh fermented milks Shubat and Ayran by combining culture-dependent and culture-independent methods. Lwt 2021, 141, 110877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, C. M.; Alves, M.; Hernandez-Mendoza, A.; Moreira, L.; Silva, S.; Bronze, M. R.; Vilas-Boas, L.; Peres, C.; Malcata, F. X. , Novel isolates of Lactobacilli from fermented Portuguese olive as potential probiotics. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2014, 59, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abriouel, H.; Omar, N. B.; López, R. L.; Martínez-Cañamero, M.; Keleke, S.; Gálvez, A. , Culture-independent analysis of the microbial composition of the African traditional fermented foods poto poto and dégué by using three different DNA extraction methods. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2006, 111, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Xie, X.; Zhang, J.; Ding, Y.; Wu, Q. , Bacterial community and composition of different traditional fermented dairy products in China, South Africa, and Sri Lanka by high-throughput sequencing of 16S rRNA genes. Lwt 2021, 144, 111209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengun, I. Y.; Nielsen, D. S.; Karapinar, M.; Jakobsen, M. , Identification of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Tarhana, a traditional Turkish fermented food. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2009, 135, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, G.; Heredia, J. B.; de Lourdes Pereira, M.; Coy-Barrera, E.; Rodrigues Oliveira, S. M.; Gutiérrez-Grijalva, E. P.; Cabanillas-Bojórquez, L. A.; Shin, H.-S.; Patra, J. K. , Korean traditional foods as antiviral and respiratory disease prevention and treatments: A detailed review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 116, 415–433. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A.; Prajapati, J. B.; Holst, O.; Ljungh, A. , Determining probiotic potential of exopolysaccharide producing lactic acid bacteria isolated from vegetables and traditional Indian fermented food products. Food Bioscience 2014, 5, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şanlier, N.; Gökcen, B. B.; Sezgin, A. C. , Health benefits of fermented foods. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2017, 59, 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-López, L.; Aguilar-Toalá, J. E.; Hernández-Mendoza, A.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B.; Liceaga, A. M.; González-Córdova, A. F. , Invited review: Bioactive compounds produced during cheese ripening and health effects associated with aged cheese consumption. Journal of Dairy Science 2018, 101, 3742–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, L.; O'Sullivan, O.; Beresford, T. P.; Ross, R. P.; Fitzgerald, G. F.; Cotter, P. D. , Molecular approaches to analysing the microbial composition of raw milk and raw milk cheese. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2011, 150, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saithong, P.; Panthavee, W.; Boonyaratanakornkit, M.; Sikkhamondhol, C. , Use of a starter culture of lactic acid bacteria in plaa-som, a Thai fermented fish. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2010, 110, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barus, T.; Kristani, A.; Yulandi, A. D. I. , Diversity of Amylase-Producing Bacillus spp. from “Tape” (Fermented Cassava). HAYATI Journal of Biosciences 2013, 20, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, M. N. A.; Ab Karim, S.; Ishak, F. A. C.; Arshad, M. M. , Past and present practices of the Malay food heritage and culture in Malaysia. Journal of Ethnic Foods 2017, 4, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chettri, R.; Tamang, J. P. , Bacillus species isolated from tungrymbai and bekang, naturally fermented soybean foods of India. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2015, 197, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B. K.; Hati, S.; Das, S. , Bio-nutritional aspects of Tungrymbai, an ethnic functional fermented soy food of Khasi Hills, Meghalaya, India. Clinical Nutrition Experimental 2019, 26, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dajanta, K.; Apichartsrangkoon, A.; Chukeatirote, E.; Frazier, R. A. , Free-amino acid profiles of thua nao, a Thai fermented soybean. Food Chemistry 2011, 125, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahidsanan, T.; Gasaluck, P.; Eumkeb, G. , A novel soybean flour as a cryoprotectant in freeze-dried Bacillus subtilis SB-MYP-1. Lwt 2017, 77, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Yang, H.; Qiao, Z.; Gao, S.; Liu, Z. , Identification and characterization of a Bacillus subtilis strain HB-1 isolated from Yandou, a fermented soybean food in China. Food Control 2013, 31, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Dumba, T.; Sheng, Y.; Li, J.; Lu, Q.; Liu, C.; Cai, C.; Feng, F.; Zhao, M. , Microbial diversity and chemical property analyses of sufu products with different producing regions and dressing flavors. Lwt 2021, 144, 111245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Xu, L.; Wu, M.; Wang, X.; Zhu, L.; Wang, C. , Effects of microbial community succession on flavor compounds and physicochemical properties during CS sufu fermentation. Lwt 2021, 152, 112313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Tamura, T.; Kyouno, N.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J. Y. , Effect of volatile compounds on the quality of miso (traditional Japanese fermented soybean paste). Lwt 2021, 139, 110573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dank, A.; van Mastrigt, O.; Yang, Z.; Dinesh, V. M.; Lillevang, S. K.; Weij, C.; Smid, E. J. , The cross-over fermentation concept and its application in a novel food product: The dairy miso case study. Lwt 2021, 142, 111041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandharaj, M.; Sivasankari, B.; Santhanakaruppu, R.; Manimaran, M.; Rani, R. P.; Sivakumar, S. , Determining the probiotic potential of cholesterol-reducing Lactobacillus and Weissella strains isolated from gherkins (fermented cucumber) and south Indian fermented koozh. Research in Microbiology 2015, 166, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, M.; Ueno, H. M.; Watanabe, M.; Tatsuma, Y.; Seto, Y.; Miyamoto, T.; Nakajima, H. , Distinctive proteolytic activity of cell envelope proteinase of Lactobacillus helveticus isolated from airag, a traditional Mongolian fermented mare's milk. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2015, 197, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.; Ghosh, K.; Ray, M.; Nandi, S. K.; Parua, S.; Bera, D.; Singh, S. N.; Dwivedi, S. K.; Mondal, K. C. , Ethnic preparation and quality assessment of Chhurpi, a home-made cheese of Ladakh, India. Journal of Ethnic Foods 2016, 3, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A. K.; Kumari, R.; Sanjukta, S.; Sahoo, D. , Production of bioactive protein hydrolysate using the yeasts isolated from soft chhurpi. Bioresource technology 2016, 219, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, S.; Tamang, J. P. , Dominant lactic acid bacteria and their technological properties isolated from the Himalayan ethnic fermented milk products. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2007, 92, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, S. D. , Diversity of bacteriocinogenic lactic acid bacteria isolated from boza, a cereal-based fermented beverage from Bulgaria. Food Control 2010, 21, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeğin, S.; Üren, A. , Biogenic amine content of boza: A traditional cereal-based, fermented Turkish beverage. Food Chemistry 2008, 111, 983–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, S.-H.; Wu, R.-J.; Watanabe, K.; Tsai, Y.-C. , Diversity of lactic acid bacteria in suan-tsai and fu-tsai, traditional fermented mustard products of Taiwan. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2009, 135, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D. T. L.; Van Hoorde, K.; Cnockaert, M.; De Brandt, E.; De Bruyne, K.; Le, B. T.; Vandamme, P. , A culture-dependent and -independent approach for the identification of lactic acid bacteria associated with the production of nem chua, a Vietnamese fermented meat product. Food Research International 2013, 50, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Chen, C.; Lei, Z. , Meta-omics insights in the microbial community profiling and functional characterization of fermented foods. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2017, 65, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Daliri, E. B.-M.; Tyagi, A.; Ofosu, F. K.; Chelliah, R.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, J.-R.; Yoo, D.; Oh, D.-H. , A discovery-based metabolomic approach using UHPLC Q-TOF MS/MS unveils a plethora of prospective antihypertensive compounds in Korean fermented soybeans. Lwt 2021, 137, 110399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, S.; Watanabe, J.; Kuribayashi, T.; Tanaka, S.; Kawahara, T. , Metabolomic evaluation of different starter culture effects on water-soluble and volatile compound profiles in nozawana pickle fermentation. Food Chemistry: Molecular Sciences 2021, 2, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Xiong, Z.; Samy Eweys, A.; Zhou, H.; Dong, Y.; Xiao, X. , Metabolomics strategy for revealing the components in fermented barley extracts with Lactobacillus plantarum dy-1. Food Research International 2021, 139, 109808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebo, O. A.; Kayitesi, E.; Tugizimana, F.; Njobeh, P. B. , Differential metabolic signatures in naturally and lactic acid bacteria (LAB) fermented ting (a Southern African food) with different tannin content, as revealed by gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC–MS)-based metabolomics. Food Research International 2019, 121, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Tang, J.; Ding, X. , Analysis of volatile components during potherb mustard (Brassica juncea, Coss.) pickle fermentation using SPME–GC-MS. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2007, 40, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhialdin, B. J.; Kadum, H.; Meor Hussin, A. S. , Metabolomics profiling of fermented cantaloupe juice and the potential application to extend the shelf life of fresh cantaloupe juice for six months at 8 °C. Food Control 2021, 120, 107555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Liu, Y.; Shi, L. , Integrated metabolomics and lipidomics profiling reveals beneficial changes in sensory quality of brown fermented goat milk. Food Chemistry 2021, 364, 130378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, M.; Li, K.; Zhang, W.; Sun, Z.; Kwok, L.-Y.; Menghe, B.; Chen, Y. , Untargeted mass spectrometry-based metabolomics approach unveils molecular changes in milk fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum P9. Lwt 2021, 140, 110759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M. Z. A.; Lau, H.; Lim, S. Y.; Li, S. F. Y.; Liu, S.-Q. , Untargeted LC-QTOF-MS/MS based metabolomics approach for revealing bioactive components in probiotic fermented coffee brews. Food Research International 2021, 149, 110656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayyash, M.; Abdalla, A.; Alhammadi, A.; Senaka Ranadheera, C.; Affan Baig, M.; Al-Ramadi, B.; Chen, G.; Kamal-Eldin, A.; Huppertz, T. , Probiotic survival, biological functionality and untargeted metabolomics of the bioaccessible compounds in fermented camel and bovine milk after in vitro digestion. Food Chemistry 2021, 363, 130243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. J.; Yang, H. J.; Kim, M. J.; Han, E.-S.; Kim, H.-J.; Kwon, D. Y. , Metabolomic analysis of meju during fermentation by ultra performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole-time of flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q-TOF MS). Food Chemistry 2011, 127, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, M.; Serrazanetti, D. I.; Tassoni, A.; Baldissarri, M.; Gianotti, A. , Improving the functional and sensorial profile of cereal-based fermented foods by selecting Lactobacillus plantarum strains via a metabolomics approach. Food Research International 2016, 89, 1095–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y. X.; Xu, B.; Fan, H. R.; Zhang, M. R.; Zhang, L. J.; Lu, C.; Zhang, N. N.; Fan, B.; Wang, F. Z.; Li, S. , 1H NMR-based chemometric metabolomics characterization of soymilk fermented by Bacillus subtilis BSNK-5. Food Research International 2020, 138, 109686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. E.; Shin, G. R.; Lee, S.; Jang, E. S.; Shin, H. W.; Moon, B. S.; Lee, C. H. , Metabolomics reveal that amino acids are the main contributors to antioxidant activity in wheat and rice gochujangs (Korean fermented red pepper paste). Food Research International 2016, 87, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, A. B.; Lamichhane, S.; Castejón, D.; Cambero, M. I.; Bertram, H. C. , 1H HR-MAS NMR-based metabolomics analysis for dry-fermented sausage characterization. Food Chemistry 2018, 240, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, S.; Nakamura, T.; Okada, S. , NMR- and GC/MS-based metabolomic characterization of sunki, an unsalted fermented pickle of turnip leaves. Food Chemistry 2018, 258, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Yu, J.; Miao, W.; Shuang, Q. , A UPLC-Q-TOF-MS-based metabolomics approach for the evaluation of fermented mare’s milk to koumiss. Food Chemistry 2020, 320, 126619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iguchi, T.; Yokosuka, A.; Kuroda, M.; Takeya, M.; Hagiya, M.; Mimaki, Y. , Steroidal glycosides from the bulbs of Lilium speciosum. Phytochemistry Letters 2020, 37, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baien, S. H.; Seele, J.; Henneck, T.; Freibrodt, C.; Szura, G.; Moubasher, H.; Nau, R.; Brogden, G.; Mörgelin, M.; Singh, M.; Kietzmann, M.; von Köckritz-Blickwede, M.; de Buhr, N. , Antimicrobial and Immunomodulatory Effect of Gum Arabic on Human and Bovine Granulocytes Against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, Q.; Bai, F.; Luo, Q.; Wu, M.; Song, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. , The assembly and antitumor activity of lycium barbarum polysaccharide-platinum-based conjugates. Journal of inorganic biochemistry 2020, 205, 111001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M. M.; Bibi, S.; Rahaman, M. S.; Rahman, F.; Islam, F.; Khan, M. S.; Hasan, M. M.; Parvez, A.; Hossain, M. A.; Maeesa, S. K.; Islam, M. R.; Najda, A.; Al-malky, H. S.; Mohamed, H. R. H.; AlGwaiz, H. I. M.; Awaji, A. A.; Germoush, M. O.; Kensara, O. A.; Abdel-Daim, M. M.; Saeed, M.; Kamal, M. A. , Natural therapeutics and nutraceuticals for lung diseases: Traditional significance, phytochemistry, and pharmacology. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 2022; 150, 113041. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Zhao, C. , Antitumor effect of soluble β-glucan as an immune stimulant. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 179, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S. S.; Passos, C. P.; Madureira, P.; Vilanova, M.; Coimbra, M. A. , Structure–function relationships of immunostimulatory polysaccharides: A review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2015, 132, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wei, W.; Tian, X.; Shi, K.; Wu, Z. , Improving bioactivities of polyphenol extracts from Psidium guajava L. leaves through co-fermentation of Monascus anka GIM 3.592 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae GIM 2.139. Industrial Crops and Products, 2016; 94, 206–215. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Wang, L.; Fan, W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Peng, W.; Wu, C. , The Application of Fermentation Technology in Traditional Chinese Medicine: A Review. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine 2020, 48, 899–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, J. S.; Xuan, S. H.; Park, S. H.; Lee, K. S.; Park, Y. M.; Park, S. N. , Antioxidative and Antiaging Activities and Component Analysis of Lespedeza cuneata G. Don Extracts Fermented with Lactobacillus pentosus. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2017, 27, 1961–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ding, Q.; Nie, S.-P.; Zhang, Y.-S.; Xiong, T.; Xie, M.-Y. , Carrot Juice Fermented with Lactobacillus plantarum NCU116 Ameliorates Type 2 Diabetes in Rats. J Agr Food Chem 2014, 62, 11884–11891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.-J.; Xu, M.-M.; Gilbert, R. G.; Yin, J.-Y.; Huang, X.-J.; Xiong, T.; Xie, M.-Y. , Colloid chemistry approach to understand the storage stability of fermented carrot juice. Food Hydrocolloids 2019, 89, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Hong, R.; Zhang, R.; Yi, Y.; Dong, L.; Liu, L.; Jia, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, M. , Physicochemical and biological properties of longan pulp polysaccharides modified by Lactobacillus fermentum fermentation. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 125, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Liu, X.; Zhao, B.; Abubaker, M. A.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J. , Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum Fermentation on the Chemical Structure and Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides from Bulbs of Lanzhou Lily. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 29839–29851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakurama, H.; Kishino, S.; Uchibori, Y.; Yonejima, Y.; Ashida, H.; Kita, K.; Takahashi, S.; Ogawa, J. , β-Glucuronidase from Lactobacillus brevis useful for baicalin hydrolysis belongs to glycoside hydrolase family 30. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2013, 98, 4021–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Sun, J.; Lassabliere, B.; Yu, B.; Liu, S. Q. , Green tea fermentation with Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 299V. Lwt 2022, 157, 113081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Chen, M.; Cui, S.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Mao, B.; Zhang, H. , Effects of Lacticaseibacillus casei fermentation on the bioactive compounds, volatile and non-volatile compounds, and physiological properties of barley beverage. Food Bioscience 2023, 53, 102695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.-N.; Guo, X.-Y.; Chen, Z.-G. , A novel and efficient method for the isolation and purification of polysaccharides from lily bulbs by Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation. Process Biochemistry 2014, 49, 2299–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. J.; Kwon, D. Y.; Moon, N. R.; Kim, M. J.; Kang, H. J.; Jung, D. Y.; Park, S. , Soybean fermentation with Bacillus licheniformis increases insulin sensitizing and insulinotropic activity. Food & Function, 2013; 4, 1675. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo-ChingWen; Lin, S.-P.; Yu, C.-P.; Chiang, H.-M., Comparison of Puerariae Radix and Its Hydrolysate on Stimulation of Hyaluronic Acid Production in NHEK Cells. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine, 2010; 38, 143–155.

- Okamoto, T.; Sugimoto, S.; Noda, M.; Yokooji, T.; Danshiitsoodol, N.; Higashikawa, F.; Sugiyama, M. , Interleukin-8 Release Inhibitors Generated by Fermentation of Artemisia princeps Pampanini Herb Extract With Lactobacillus plantarum SN13T. Frontiers in microbiology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-W.; Mou, Y.-C.; Su, C.-C.; Chiang, B.-H. , Antihepatocarcinoma Activity of Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermented Panax notoginseng. J Agr Food Chem 2010, 58, 8528–8534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Luo, M.; Wang, W.; Zhao, C.-j.; Gu, C.-b.; Li, C.-y.; Zu, Y.-g.; Fu, Y.-j.; Guan, Y. , Biotransformation of polydatin to resveratrol in Polygonum cuspidatum roots by highly immobilized edible Aspergillus niger and Yeast. Bioresource technology 2013, 136, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheih, I. C.; Fang, T. J.; Wu, T.-K.; Chang, C.-H.; Chen, R.-Y. , Purification and Properties of a Novel Phenolic Antioxidant from Radix astragali Fermented by Aspergillus oryzae M29. J Agr Food Chem 2011, 59, 6520–6525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.-K.; Jo, W.-R.; Park, H.-J. , Immune-enhancing activity of C. militaris fermented with Pediococcus pentosaceus (GRC-ON89A) in CY-induced immunosuppressed model. BMC complementary and alternative medicine, 2018; 18. [Google Scholar]

- Ermolenko, E. I.; Desheva, Y. A.; Kolobov, A. A.; Kotyleva, M. P.; Sychev, I. A.; Suvorov, A. N. , Anti–Influenza Activity of Enterocin B In vitro and Protective Effect of Bacteriocinogenic Enterococcal Probiotic Strain on Influenza Infection in Mouse Model. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins 2018, 11, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, Y.; Moriya, T.; Sakai, F.; Ikeda, N.; Shiozaki, T.; Hosoya, T.; Nakagawa, H.; Miyazaki, T. , Oral administration of Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055 is effective for preventing influenza in mice. Scientific reports 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Sankaran, B.; Laucirica, D. R.; Patil, K.; Salmen, W.; Ferreon, A. C. M.; Tsoi, P. S.; Lasanajak, Y.; Smith, D. F.; Ramani, S.; Atmar, R. L.; Estes, M. K.; Ferreon, J. C.; Prasad, B. V. V. , Glycan recognition in globally dominant human rotaviruses. Nature Communications 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmar, R. L.; Ramani, S.; Estes, M. K. , Human noroviruses. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 2018, 31, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawashima, T.; Hayashi, K.; Kosaka, A.; Kawashima, M.; Igarashi, T.; Tsutsui, H.; Tsuji, N. M.; Nishimura, I.; Hayashi, T.; Obata, A. , Lactobacillus plantarum strain YU from fermented foods activates Th1 and protective immune responses. International Immunopharmacology 2011, 11, 2017–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 132. Robinson, Christopher M.; Jesudhasan, Palmy R.; Pfeiffer, Julie K., Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide Binding Enhances Virion Stability and Promotes Environmental Fitness of an Enteric Virus. Cell host & microbe, 2014; 15, 36–46.

- Li, K.; Park, M.-K.; Ngo, V.; Kwon, Y.-M.; Lee, Y.-T.; Yoo, S.; Cho, Y.-H.; Hong, S.-M.; Hwang, H. S.; Ko, E.-J.; Jung, Y.-J.; Moon, D.-W.; Jeong, E.-J.; Kim, M.-C.; Lee, Y.-N.; Jang, J.-H.; Oh, J.-S.; Kim, C.-H.; Kang, S.-M. , Lactobacillus plantarum DK119 as a Probiotic Confers Protection against Influenza Virus by Modulating Innate Immunity. PloS one 2013, 8, e75368. [Google Scholar]

- Antunes, A. E. C.; Vinderola, G.; Xavier-Santos, D.; Sivieri, K. , Potential contribution of beneficial microbes to face the COVID-19 pandemic. Food Research International 2020, 136, 109577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubenberger, J. K.; Morens, D. M. , The Pathology of Influenza Virus Infections. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease, 2008; 3, 499–522. [Google Scholar]

- Youn, H.-N.; Lee, D.-H.; Lee, Y.-N.; Park, J.-K.; Yuk, S.-S.; Yang, S.-Y.; Lee, H.-J.; Woo, S.-H.; Kim, H.-M.; Lee, J.-B.; Park, S.-Y.; Choi, I.-S.; Song, C.-S. , Intranasal administration of live Lactobacillus species facilitates protection against influenza virus infection in mice. Antiviral Research 2012, 93, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, S.; Ikegami, S.; Kume, A.; Horiuchi, H.; Sasaki, H.; Orii, N. , Reducing the risk of infection in the elderly by dietary intake of yoghurt fermented with Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus OLL1073R-1. British Journal of Nutrition, 2010; 104, 998–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Lukashev, A. N.; Vakulenko, Y. A.; Turbabina, N. A.; Deviatkin, A. A.; Drexler, J. F. , Molecular epidemiology and phylogenetics of human enteroviruses: Is there a forest behind the trees? Reviews in Medical Virology 2018, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doms, R. W. , Basic Concepts. 2016, 29-40.

- Garg, R. R.; Karst, S. M. , Interactions Between Enteric Viruses and the Gut Microbiota. 2016, 535-544.

- Kang, J. Y.; Lee, D. K.; Ha, N. J.; Shin, H. S. , Antiviral effects of Lactobacillus ruminis SPM0211 and Bifidobacterium longum SPM1205 and SPM1206 on rotavirus-infected Caco-2 cells and a neonatal mouse model. Journal of Microbiology 2015, 53, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Breiman, A.; le Pendu, J.; Uyttendaele, M. , Anti-viral Effect of Bifidobacterium adolescentis against Noroviruses. Frontiers in microbiology 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavicchioli, V. Q.; Carvalho, O. V. d.; Paiva, J. C. d.; Todorov, S. D.; Silva Júnior, A.; Nero, L. A. , Inhibition of herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) and poliovirus (PV-1) by bacteriocins from lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis and enterococcus durans strains isolated from goat milk. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2018, 51, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khani, S.; Motamedifar, M.; Golmoghaddam, H.; Hosseini, H. M.; Hashemizadeh, Z. , In vitro study of the effect of a probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus rhamnosus against herpes simplex virus type 1. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases 2012, 16, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastromarino, P.; Cacciotti, F.; Masci, A.; Mosca, L. , Antiviral activity of Lactobacillus brevis towards herpes simplex virus type 2: Role of cell wall associated components. Anaerobe 2011, 17, 334–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavi, E.; Makvandi, M.; Teimoori, A.; Ataei, A.; Ghafari, S.; Samarbaf-Zadeh, A. , Antiviral effects of Lactobacillus crispatus against HSV-2 in mammalian cell lines. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association 2018, 81, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Araújo, F. F.; Farias, D. d. P. , Psychobiotics: An emerging alternative to ensure mental health amid the COVID-19 outbreak? Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2020; 103, 386–387. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, J.-Y.; Kim, J. I.; Park, S.; Yoo, K.; Kim, I.-H.; Joo, W.; Ryu, B. H.; Park, M. S.; Lee, I.; Park, M.-S. , Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum and Leuconostoc mesenteroides Probiotics on Human Seasonal and Avian Influenza Viruses. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2018, 28, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, T.; Zhang, F.; Lui, G. C. Y.; Yeoh, Y. K.; Li, A. Y. L.; Zhan, H.; Wan, Y.; Chung, A. C. K.; Cheung, C. P.; Chen, N.; Lai, C. K. C.; Chen, Z.; Tso, E. Y. K.; Fung, K. S. C.; Chan, V.; Ling, L.; Joynt, G.; Hui, D. S. C.; Chan, F. K. L.; Chan, P. K. S.; Ng, S. C. , Alterations in Gut Microbiota of Patients With COVID-19 During Time of Hospitalization. Gastroenterology, 2020; 159, 944–955.e8. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuzuki, S.; Shook, N. J.; Sevi, B.; Lee, J.; Oosterhoff, B.; Fitzgerald, H. N. , Disease avoidance in the time of COVID-19: The behavioral immune system is associated with concern and preventative health behaviors. PloS one 2020, 15, e0238015. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, B.; Gürakan, G. C.; Ünlü, G. , Kefir: A Multifaceted Fermented Dairy Product. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins 2014, 6, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamida, R. S.; Shami, A.; Ali, M. A.; Almohawes, Z. N.; Mohammed, A. E.; Bin-Meferij, M. M. , Kefir: A protective dietary supplementation against viral infection. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 2021; 133, 110974. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A.; San Mauro, M.; Sanchez, A.; Torres, J. M.; Marquina, D. , The Antimicrobial Properties of Different Strains of Lactobacillus spp. Isolated from Kefir. Systematic and applied microbiology 2003, 26, 434–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojadoost, B.; Kulkarni, R. R.; Brisbin, J. T.; Quinteiro-Filho, W.; Alkie, T. N.; Sharif, S. , Interactions between lactobacilli and chicken macrophages induce antiviral responses against avian influenza virus. Research in Veterinary Science 2019, 125, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalbantoglu, U.; Cakar, A.; Dogan, H.; Abaci, N.; Ustek, D.; Sayood, K.; Can, H. , Metagenomic analysis of the microbial community in kefir grains. Food Microbiology 2014, 41, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, L. Y. E.; Too, H. K. I.; Tan, E. L.; Chow, T.-K. V.; Shek, P.-C. L.; Tham, E.; Alonso, S. , Antiviral activity of Lactobacillus reuteri Protectis against Coxsackievirus A and Enterovirus 71 infection in human skeletal muscle and colon cell lines. Virology journal 2016, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botic, T.; Klingberg, T.; Weingartl, H.; Cencic, A. , A novel eukaryotic cell culture model to study antiviral activity of potential probiotic bacteria. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2007, 115, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivec, M.; Botić, T.; Koren, S.; Jakobsen, M.; Weingartl, H.; Cencič, A. , Interactions of macrophages with probiotic bacteria lead to increased antiviral response against vesicular stomatitis virus. Antiviral Research 2007, 75, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, W.; Lahore, H.; McDonnell, S.; Baggerly, C.; French, C.; Aliano, J.; Bhattoa, H. , Evidence that Vitamin D Supplementation Could Reduce Risk of Influenza and COVID-19 Infections and Deaths. Nutrients 2020, 12, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.; Carr, A.; Gombart, A.; Eggersdorfer, M. , Optimal Nutritional Status for a Well-Functioning Immune System Is an Important Factor to Protect against Viral Infections. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G. , Important roles of dietary taurine, creatine, carnosine, anserine and 4-hydroxyproline in human nutrition and health. Amino Acids 2020, 52, 329–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, T. M.; Shakur, S.; Pham Do, K. H. , Consumer concern about food safety in Hanoi,Vietnam. Food Control 2019, 98, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, H.; Kaptan, G.; Stewart, G.; Grainger, M.; Kuznesof, S.; Naughton, P.; Clark, B.; Hubbard, C.; Raley, M.; Marvin, H. J. P.; Frewer, L. J. , Drivers of existing and emerging food safety risks: Expert opinion regarding multiple impacts. Food Control 2018, 90, 440–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H. V.; Dinh, T. L. , The Vietnam's food control system: Achievements and remaining issues. Food Control 2020, 108, 106862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavsara, H. K.; Ozilgen, S.; Dagdeviren, M. , Safeguarding Grandma's fermented beverage recipes for food security: Food safety challenges. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science 2020, 22, 100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byakika, S.; Mukisa, I. M.; Byaruhanga, Y. B.; Male, D.; Muyanja, C. , Influence of food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of processors on microbiological quality of commercially produced traditional fermented cereal beverages, a case of Obushera in Kampala. Food Control 2019, 100, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyei, D.; Owusu-Kwarteng, J.; Akabanda, F.; Akomea-Frempong, S. , Indigenous African fermented dairy products: Processing technology, microbiology and health benefits. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2019, 60, 991–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).