1. Introduction

Population-wide vaccination programs aim to improve the well-being of the general population and play a vital role in public health by providing individual immunity and decreasing the spread of communicable diseases. While this approach has proved safe and effective for a large majority of individuals, both beneficial and adverse consequences of immune activation are not shared equally among different subpopulations and the overall health impact of population-wide vaccination programs could be improved if the factors leading to adverse outcomes were better understood. Recent advances in understanding redox regulation of the nucleotide-binding domain leucine-rich repeat [LRR] and pyrin-containing receptor 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome allows a mechanistic examination of how variations in its activation in response to vaccination might lead to adverse outcomes, including in asthmatic and autistic populations.

Effective production of neutralizing antibodies in a high proportion of the public (i.e. herd immunity) takes priority when formulating public health policies for high-risk infectious diseases, especially under pandemic circumstances such as the COVID-19 outbreak. Therefore, despite the substantial benefit/risk assessments from clinical trial data during vaccine development, it is important to investigate mechanisms of unwanted side effects from vaccination and the potential impact on specifically affected subpopulations. Thus, while it is critical to define subpopulations at higher risk of serious disease from a threatening virus (e.g. the elderly, persons with diabetes etc.), it is equally critical to define subpopulations with an elevated risk of vaccination side effects.

Recognition of specific factors contributing to side effect risk could identify these at-risk subpopulations, leading to more optimal targeting of vaccine interventions. Notably, there have been relatively few in depth studies of vaccination side effects, partly because the focus of vaccine administration programs is to increase uptake by the general public and partly because the occurrence of serious side effects from vaccination has become a controversial issue.

Notably, a recent Center for Disease Control (CDC)-sponsored study1 showed that aluminum adjuvants are associated with a dose-related increased risk of developing asthma, indicating induction of a T-helper 2 cell (Th2)-biased immune response in a vulnerable subpopulation. While inflammation is a normal and unavoidable component of an effective immune response to vaccination, this study raises important questions, including: 1. What factors are responsible for the hyperinflammatory response of this vulnerable subpopulation? 2. Are there other adverse outcomes, such as autism, which may result from adjuvant-containing vaccinations? 3. What risk mitigation steps can be taken to support safer vaccination of vulnerable subpopulation?

Here we focus on some of the mechanisms through which specific side effects of vaccination may potentially originate, the interaction of adjuvants with the immune system and the implications for inflammation-vulnerable children.

2. NLRP3, oxidative stress and inflammation

Inflammation and formation of cytokine-generating inflammasome complexes are crucial components of the defense mechanism against pathogens and a key event in the innate immune response to vaccination

2,3. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome has been identified as an early component of the immune response to vaccination

4-6 and has also been implicated as an important contributor to SARS-CoV-2 morbidity and mortality

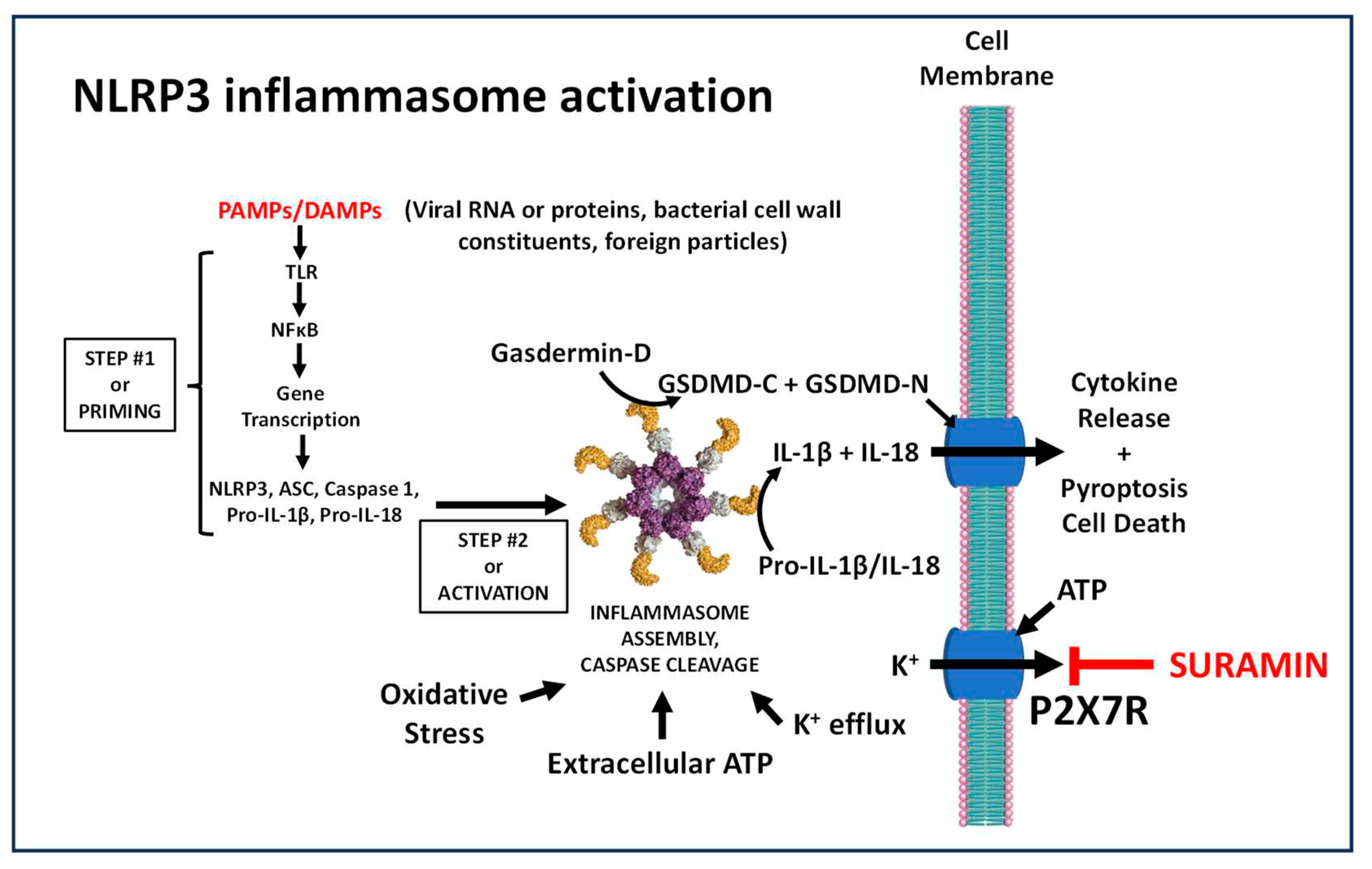

7-11. As illustrated in

Figure 1, initial priming of the NLRP3 response upon antigen exposure involves Toll-like receptor (TLR) recognition and NF-κB-mediated transcription of genes coding for inflammasome components, including NLRP3, ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain), procaspase-1, pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18. NLRP3 activity involves caspase 1-mediated release of active cytokines IL-1β and IL-18

12. Multiple signals promote NLRP3 activity, including potassium efflux, which can be triggered by the ATP-activated P2X7 purinergic receptor

13 and oxidative stress

14, a metabolic condition commonly associated with inadequate levels of the antioxidant glutathione (GSH).

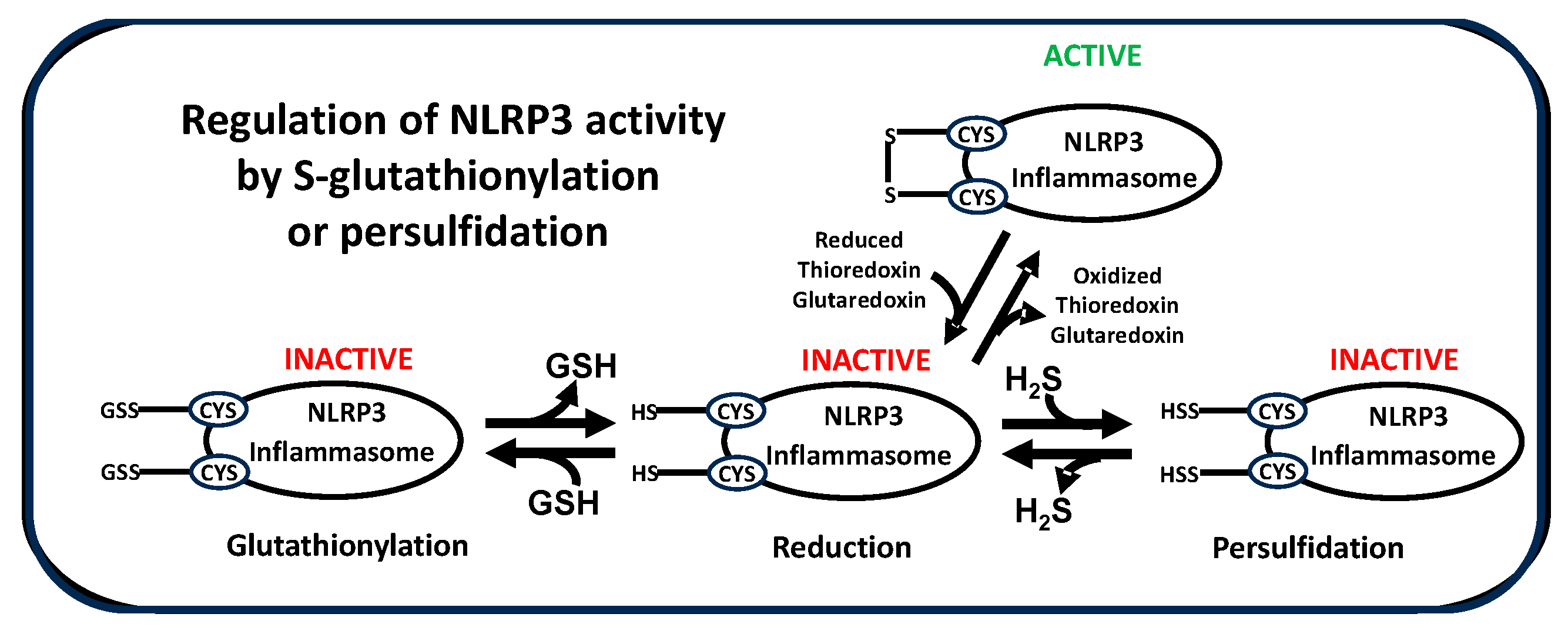

NLRP3 activity is also subject to regulation by post-translational modifications, including ubiquitination and phosphorylation15. Of note, S-glutathionylation of cysteine residues in NLRP3 itself16 or in inflammasome-associated components caspase-117, NEK-7 (NIMA-related kinase-7)18 and the linker protein ASC19, serves to suppress NLRP3 activity. Intracellular levels of GSH dramatically decrease upon P2X7 activation by extracellular ATP and this decrease is essential for NLRP3 activation, while higher extracellular GSH decreases NLRP3 activation12. Decreased activity of thioredoxin and glutaredoxin also promotes oxidative stress and NLRP3 activation oxidative stress20. Thus, multiple redox-related mechanisms combine to initiate and maintain NLRP3-mediated inflammation.

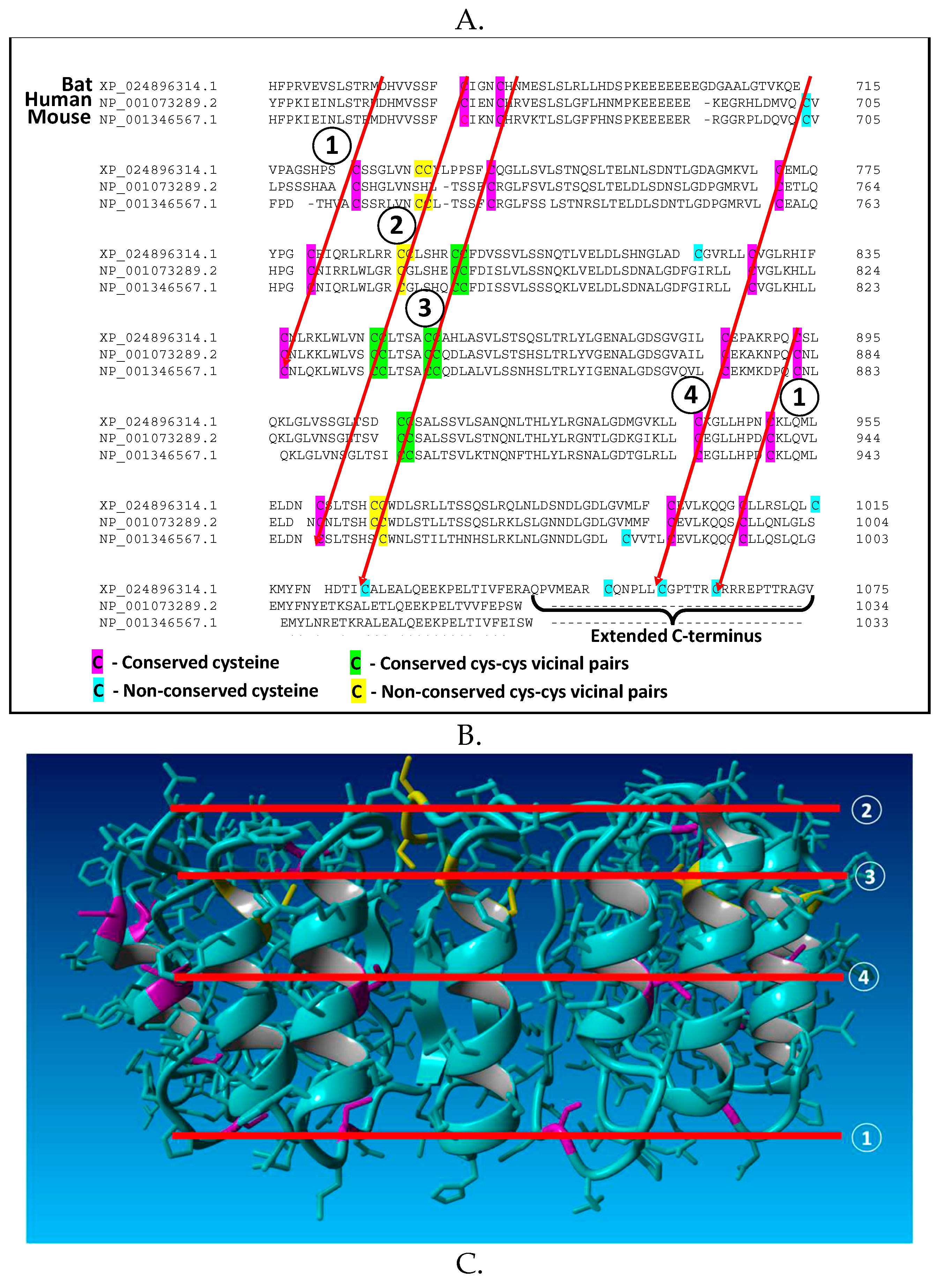

An examination of cysteine residues in the leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain of NLRP3 reveals a potential molecular mechanism by which redox status can regulate its activity. As illustrated for mouse, human and bat sequences in

Figure 2A, highly conserved LRR cysteine residues exist in a regular pattern, corresponding to the sequences of multiple repeats, which are approximately 56 amino acids in length. Within the structure of the NLRP3 LRR these repetitive cysteine residues form four bands, with multiple residues exposed on the protein surface (

Figure 2B). This structural motif is poised to interact with cysteine residues from other inflammasome proteins to form disulfide linkages, whose stability will depend upon the local redox environment as well as redox-active proteins such as thioredoxin and glutaredoxin, which reversibly reduce/oxidize disulfide bonds. Notably, the LRR of NLRP3 contains multiple vicinal cysteine pairs (five in the human sequence), which are uncommon in proteins and exhibit unique redox-dependent reactivity.

Formation and stability of disulfide linkages, including persulfides (-SS-X), are redox-sensitive, being favored under more oxidizing conditions (i.e. oxidative stress) and less favored under reducing conditions, and they are reversibly catalyzed by oxidoreductase proteins, including thioredoxin, glutaredoxin and protein disulfide isomerase

22. Modification of these protein thiol residues by S-glutathionylation, persulfidation or other moieties interferes with their ability to participate in intermolecular disulfide bond formation, providing an opportunity for inflammasome regulation. Based upon this analysis, we propose that oxidizing conditions increase NLRP3 inflammasome activity in part by promoting disulfide bond formation, which stabilizes formation of large heteromeric protein complexes (

Figure 2C). Thus, oxidative stress can promote assembly of active inflammasomes via disulfide-stabilized complexes with ASC, NEK7 or caspase-1, consistent with the requirement that these proteins must be de-glutathionylated for NLRP3 to be active44-47. This proposed mechanism is also consistent with the observation that the dramatic GSH decrease upon ATP activation is essential for NLRP3 inflammasome activation

13, and other redox-related metabolic changes that promote inflammation

23. As described below, differences in NLRP3 LRR cysteine residues may contribute to the greater virulence of SARS-CoV-2 in humans vs. bats.

3. Nrf2 and resolution of inflammation

In addition to cytokine production, acute inflammasome activation initiates a broad metabolic reprogramming, leading to significant changes in DNA methylation and gene expression. Notably, in a study of the humoral immune response to influenza vaccination, the strongest correlations between DNA methylation and gene expression were observed for immune system-related gene ontogeny (GO) pathways including glutathione regulation pathways24.

Post-vaccination changes in gene expression are normally associated with resolution of the acute inflammatory process, including the activation of NFE2L2, which codes for the antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2). Nrf2 activity increases in response to oxidative stress and exerts a broad range of actions that serve to normalize redox status and decrease inflammation. Nrf2 augments expression of the cysteine uptake transporter EAAT3 (excitatory amino acid transporter 3) and the cystine-glutamate antiporter xCT, as well as transsulfuration pathway enzymes cystathionine beta synthase (CBS) and cystathionine gamma lyase, also known as cystathionase (CSE)25-27. These actions combine to increase intracellular cysteine availability for both GSH synthesis and for CBS and CSE-mediated production of hydrogen sulfide (H2S), which promotes persulfide formation at protein thiols, and several studies have reported inhibitory effects of H2S on NLRP3 activity28-31. Indeed, a recent study demonstrated the importance of Nrf2, cysteine, and persulfide formation in suppressing prolonged inflammation after LPS-induced NLRP3 activation32. They found that early activation of Nrf2 by oxidative stress up-regulated xCT expression and cystine uptake, leading to increased formation of persulfide metabolites, which terminated IL-1β production. Additional studies are needed to determine if Nrf2-induced xCT activity leads to increased persulfidation of NLRP3 cysteine residues or other proteins in the inflammasome cascade.

Based upon these recent insights, it is apparent that NLRP3 inflammasome activity may be more prominent and incompletely suppressed in individuals exhibiting low Nrf2 activity and low cysteine levels, which can lead to a state of chronic inflammation. Thus, recognition of the influence of oxidative stress in promoting NLRP3 activity provides a framework for a better understanding of factors that can contribute to excessive activation of inflammation following vaccination.

4. Aluminum-containing vaccine adjuvants

Aluminum salts have been widely used as adjuvants since the 1930s and may include amorphous aluminum hydroxyphosphate sulfate (AAHS), aluminum hydroxide, aluminum phosphate, or potassium aluminum sulfate (Alum)33. As a major component of the innate immune system targeted by adjuvants, the NLRP3 inflammasome is widely acknowledged to initiate cytokine production upon vaccination34,35. Attempts have been made to investigate the efficacy and safety of these adjuvants in humans using reviews and meta-analyses of clinical data36. However, conclusions from vaccine studies are complicated because most clinical trials use adjuvants in both the experimental and control groups37,38. In addition, vaccine clinical trials normally recruit volunteers from the general healthy populations and lack focus on specific potentially vulnerable populations. Such focused studies are becoming even more crucial given the increasing impact of infectious diseases and the subsequent increase in the frequency and the variety of vaccinations as exemplified by the latest emergence of Covid-19 varieties and its vaccinations.

Unlike older vaccines that were initially made from whole microorganisms, many modern vaccines contain refined DNA, RNA, or proteins as the antigen or antigen-producing elements to generate an immune response and immunity. These modifications, aiming to improve the safety profile and ease of manufacture, have resulted in reduced immunogenicity. Therefore, vaccines are frequently formulated with the addition of immunogenic adjuvants of various inorganic and organic natures that mimic pathogen-associated molecular patterns and thereby induce the innate immune response to enhance the activation of adaptive immunity.

As noted above, a recent Center for Disease Control (CDC)-sponsored study found a dose-dependent relationship between vaccination-derived aluminum and persistent asthma risk in a pediatric population1, reporting an adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of 1.26/mg of aluminum for subjects with eczema (a Th2-related condition) and 1.19/mg for non-eczema subjects, with the average total aluminum dosage being about 4 mg for both groups. Thus vaccination-derived aluminum provides a dose-dependent asthma risk for a vulnerable subpopulation, consistent with the ability of aluminum adjuvants to activate the NLRP3 inflammatory response.

We previously reviewed how genetic variants affecting the NLRP3-mediated inflammatory response might be associated with the risk of atopy and asthma from vaccine-derived aluminum in a vulnerable subpopulation39,40 28. Since a multitude of environmental toxins and insults cause oxidative stress and lower GSH levels, it is likely that both genetic and environmental factors contribute to the risk of excessive inflammation in response to vaccination. In light of the now well-established role of oxidative stress in promoting NLRP3 activity, we now propose that individuals with lower antioxidant capacity and lower GSH levels may also represent a vulnerable subpopulation for a range of untoward inflammatory responses upon immune stimulation with adjuvanted (e.g. aluminum-containing) vaccines. These adverse consequences may be manifested as either an excessive acute response upon vaccination or an inability to fully suppress NLRP3 activity following vaccination, resulting in a chronic inflammatory state. Notably, the antigen component of vaccines is the primary stimulus for the immune/inflammatory response, which is augmented by adjuvants such as aluminum. Thus, even non-adjuvanted vaccines carry an intrinsic risk of adverse inflammatory responses, which is increased to a varying degree by adjuvants, as well as by the innate and adaptive immune system characteristics of individuals receiving vaccination.

Aluminum is well-recognized for its ability to promote oxidative stress, even at low concentrations41,42, and aluminum-containing adjuvants are widely employed to augment the efficacy of vaccines to induce antibody production. Numerous studies have documented activation of NLRP3 by aluminum in various tissues, including lung, liver and brain tissue43-45. A variety of aluminum-containing and non-aluminum-containing vaccine adjuvants promote NLRP3 activity46,47. Notably, aluminum adjuvants are commonly used to induce T helper type 2 (Th2)-mediated inflammation in murine allergy/asthma models48.

A 2016 study examined the effects of several aluminum-based adjuvant formulations on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced IL-1β production in THP-1 cells differentiated to a macrophage phenotype49. The nano- and micro-particulate aluminum adjuvants augmented LPS-induced IL-1β production by several fold, while soluble aluminum ion (AlCl3) was without effect, indicating the importance of particulate formulations for adjuvant action. The adjuvant-induced increase in IL-1β was significantly lower in THP-1 cells with decreased NLRP3 expression and was associated with a 25-30% reduction in cellular GSH levels49. Moreover, pretreatment of cells with N-acetylcysteine, which promotes GSH synthesis, significantly decreased the ability of the aluminum adjuvants to augment IL-1β production. Thus, activation of NLRP3 activity by aluminum-containing vaccine adjuvants is promoted by GSH depletion and inhibited by increased provision of the GSH precursor cysteine.

Aluminum and aluminum-containing vaccines have been suggested to play a role in neurological disorders. Evidence indicating a role for vaccine-derived aluminum in ASD was reviewed by Shaw and Tomljenovic50. Their analysis included comparisons of ASD prevalence in different countries vs. total vaccine-derived aluminum dose. In an animal study, they also showed that administration of aluminum adjuvant to neonatal mice at doses relevant to the U.S. vaccine schedule was associated with behavioral deficits51. A link between aluminum and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), as well as other brain disorders, has long been the subject of debate and aluminum levels are significantly elevated in serum, CSF, and brain tissue of both autism and AD subjects52,53. NLRP3 activation has been reported in postmortem AD brain54-56, in an aluminum-based mouse model of AD57, and in cultured human neuronal cells58. Moreover, NLRP3 inhibition has been proposed as a novel treatment approach for AD treatment59. It must be noted that while the main source of systemic aluminum intake is considered to be through dietary and inhalation routes, and the vaccine content of aluminum is considered negligible in comparison, its NLRP3-related adjuvant role is a local mechanism.

In certain populations the inflammatory response to vaccine-derived aluminum may persist longer than ideal, depending upon the individual’s ability to terminate ongoing NLRP3 activity, with Nrf2 activity and GSH levels playing an important role. Alternative adjuvants have been developed that might minimize aluminum-related oxidative stress disorders, which are primarily non-metals and therefore subject to metabolism. However, most of these adjuvants have been proven to be too toxic and have shorter periods of activity because of their fast metabolism and therefore not as efficient or as cost-effective as the use of aluminum46,47. Thus, further research is needed to develop vaccine adjuvants with a more ideal profile.

5. Vulnerable subpopulations: Asthma, atopy and vaccination

Asthma is an inflammatory disorder involving complex multifactorial interactions arising from the contribution of genetic and environmental risk factors. The T-helper 2 (Th2-high) asthma endotype, as its name suggests, is a Th2-cell-mediated disease, and occurs often in patients who have atopy, the genetic tendency to develop allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis, asthma and atopic dermatitis (eczema). A subpopulation of children exists who are vulnerable to asthma because of epigenetic modifications and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). SNPs in IL-33 and IL-18 genes have been implicated in atopic diseases60-64, and SNPs affecting the IL-4/IL-13 (Th2) pathway can strongly influence serum IgE levels as well as the risk of developing childhood asthma and atopy65,66. Production of Th2-cell-associated cytokines by CD4+ T cells is under both genetic and epigenetic control. For example, a SNP in a gene locus at position 5q31.3 (rs7705042), which contains the IL4 and IL13 genes, has been associated with increased susceptibility to asthma and atopy67. This locus is also hypomethylated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, which may provide an epigenetic link to environmental exposures68,69. Furthermore, the glutathione S-transferase (GST) gene has variants that can contribute to a state of oxidative stress, which can affect NLRP3 activity (as discussed below) and trigger the onset of asthma70. In general, the inhibitory influence of oxidative stress over methylation reactions, including DNA and histone methylation, regulates gene expression via epigenetic mechanisms71. In mouse models of asthma that genetically lacked IL-4, IL-5, and/or IL-13, key aspects of asthma were absent72-74. On the other hand, administration of the pro-Th1 cell cytokine IL-12 can suppress asthma in mice via the production of interferon (IFN)-γ by Th1 cells75,76. Thus, both genetic and environmental factors affecting Th1/Th2 both contribute to asthma and atopy risk.

Genetic factors play a crucial role in the regulation of immune responses to vaccines in early life through, for example, cytokine gene expression77. These include genes associated with atopy such as IL-4 and IL-1378-80. Within vaccine formulations, aluminum adjuvants, along with promoting oxidative stress, induce a cytokine context characterized by the absence of the important regulatory cytokine IL-1281. This cytokine context is driven by inflammasome activation, most notably through NLRP3, and the subsequent release of IL-18, IL-33, and PGE2, which, in turn, drives a Th2 response and the production of cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-1381. It follows then, that genetic factors can influence the response to vaccines in children, including expression of cytokine genes associated with atopy such as IL-4 and IL-13, and that aluminum-containing vaccines have the potential to induce a vigorous Th2 immune response in a genetically vulnerable sub-population, such as children with a family history of atopy, who inherently display strong Th2 cytokine profiles characterized by increased levels of IL-4, as well as IL-5, and IL-13.

In present times, with changing immune regulatory factors indicated by the hygiene and microbiome hypotheses (e.g. diminished exposure to commensal bacteria), young immune systems, especially those in a genetically predisposed subpopulation, may be more vulnerable to the risk of immune dysfunction from environmental factors such as adjuvanted vaccination. Indeed, adjuvant-containing vaccination may be an amplifier of the hygiene hypothesis and microbiome theory, and thus a contributing factor to the increase in allergic diseases such as asthma, especially in a genetically predisposed young subpopulation.

A family health history can help identify the individual child’s risk of developing unusual adverse effects to vaccination in the setting of pediatric care and routine vaccinations. Atopy has a strong hereditary component such that if both parents are atopic, offspring have a 40–60% risk of developing atopy, while if one parent is affected there is a 20–40% risk82. A review of family history concluded that atopic diseases, major depression, and other mood disorders can be predicted based on familial risks with sensitivities of ∼50% and positive predictive values of 25% to 50%83. However, this research was conducted outside of a primary care setting, potentially limiting its utility in such a setting. Regardless, a family health history is an invaluable record of health information when considering the risk of atopy. Thus, the increased risk of childhood asthma associated with the dose of vaccine adjuvant aluminum6 may reflect familial/genetic hyperresponsiveness to inflammation in a vulnerable subpopulation, and a deeper understanding of factors controlling inflammatory responsiveness may illuminate underlying mechanisms.

6. Vulnerable subpopulations: Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and vaccination

As outlined in a “White Paper on Studying the Safety of the Childhood Immunization Schedule”84, asthma was the first of 30 adverse outcomes of vaccination to be investigated by the CDC utilizing the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD). Asthma was chosen first based on “feasibility, public health significance, and public concern”. Notably, the CDC stated: “Autism, in contrast, was moved off the priority list because it has been extensively studied relative to the vaccination schedule, despite its high public concern ranking.” However, there are several reasons calling for a renewed focus on autism research with respect to the possible role of vaccination. Firstly, there are new developments in the underlying areas of science such as immunology, genetics and toxicology, especially following Covid-19 with a surge of scientific research on various aspects of the infection, vaccine, immune system, and long COVID. One specific development is the recognition of the central role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in vaccine response, which now allows a re-examination of a possible link to autism.

The remarkable increase in ASD prevalence over the past three decades, recently reported as 1 in 36 among children aged 8 yrs. in the U.S.85, can only be attributed to the vital role of non-genetic factors, broadly described as environmental factors. While many causation theories have been put forward, the most robustly recognized ASD finding is the occurrence of systemic oxidative stress, which has been reported in many studies from across the world without apparent contradiction (for a meta-analysis of 87 studies see ref. 86). Thus, circulating levels of GSH and cysteine in ASD are 20-35% below control levels, accompanied by a significantly lower ratio of reduced GSH to oxidized GSSG87. Moreover, protein thiol status is also abnormal in ASD (i.e., increased oxidized disulfide vs. reduced thiol)88, which has particular relevance for inflammasome activity and complex formation. Brain tissue studies have documented region-specific deficits of GSH and oxidative stress in ASD subjects89-91, as well as evidence of neuroinflammation92-96, particularly involving astrocytes and microglia, as summarized in a recent meta-analysis of postmortem studies97.

The NLRP3 inflammasome is activated in ASD, in association with elevated cytokine levels. Thus, multiple studies have found significantly elevated plasma levels of IL-1β, IL-18, and other cytokines in ASD subjects, and increasing levels are associated with more severe communication and behavioral abnormalities98-101. Notably, the increase was particularly prominent in children who had regressive autism (i.e. a loss of previously acquired abilities)99. A 2016 study found markedly elevated gene expression of NLRP3, caspase-1, IL-1β, and IL-18 in baseline and LPS/ATP-stimulated monocytes of ASD subjects, along with elevated serum levels of IL-1β and IL-18 and elevated caspase-1 activity102. Production of IL-1β in response to LPS and the environmental toxin polybrominated diphenyl ether was significantly higher in peripheral blood monocytic cells (PBMCs) from ASD subjects103. It is also notable that plasma levels of both thioredoxin104 and peroxiredoxin105 are elevated in ASD, consistent with NLRP3 activation and their cellular extrusion, which may even serve as biomarkers. Thus, oxidative stress in ASD is accompanied by a persistent increase in NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Since oxidative stress and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome are features of ASD and adjuvants such as aluminum promote oxidative stress and NLRP3 activation, it is logical to ask if ASD presents a special vulnerability. In other words: Are individuals with pre-existing elevated oxidative stress more prone to suffer greater inflammation-related side effects from vaccination with aluminum-containing adjuvants? Do these individuals represent a vulnerable subpopulation at higher risk of persistent inflammation after vaccination? Are genetically predisposed individuals to ASD more at risk of neurodevelopmental disorders as a result of exposure to antigens such as vaccines and vaccine adjuvants?

As noted above, Nrf2 activation is crucial for the resolution and restoration of homeostasis after an acute inflammatory response and serves to limit the intensity and duration of NLRP3-mediated inflammatory responses, including those elicited by SARS-Co-V2107 and vaccination108. However, Nrf2 gene expression was found to be > 50% lower in granulocytes from ASD subjects, in association with significantly lower rates of oxygen consumption and other indicators of mitochondrial respiration109. Similarly, we found Nrf2 mRNA expression to be significantly lower in the frontal cortex of ASD subjects110. In vitro, aluminum hydroxide increases Nrf2 expression in conjunction with its induction of oxidative stress111. Moreover, aluminum citrate inhibits, as well as downregulates the expression of the xCT cystine/glutamate antiporter 112. This is the primary pathway for the transport of cystine across the blood-brain barrier and it is crucial for cysteine availability in astrocytes and neurons. As noted above, xCT activity is essential for termination of NLRP3-mediated inflammation32. Together, these observations suggest that aluminum may interfere with the ability of Nrf2 to activate xCT-mediated cystine uptake, resulting in excessive and prolonged activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, particularly in ASD subjects, who exhibit lower expression of Nrf2.

An important role for activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in ASD is further supported by animal studies. Thus, both prenatal maternal immune activation (MIA)

113,114 and early postnatal immune activation (PIA)

115 with either LPS or poly(IC) gives rise to ASD-like behaviors and neurological effects involving both NLRP3 and the P2X7 receptor, creating a now widely employed animal model of ASD

116-120. Notably, P2X7 inhibitors, including suramin (see

Figure 1), which was originally used to treat African sleeping sickness and river blindness, showed effectiveness in MIA and PIA animal models

118-120 and low-dose suramin showed benefits in mitigating ASD symptoms in a preliminary human clinical trial

121.

7. NLRP3 and COVID-19

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has provided a grim illustration of differential vulnerability among different subpopulations to activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. As noted above, NLRP3 activation plays a central role in the cytokine storm initiated by SARS-CoV-2 infection, leading in some cases to severe life-threatening cardiopulmonary dysfunction. In fact, multiple postmortem studies of these individuals have provided direct evidence of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the lung and other tissues7-11. Factors that increase the likelihood of severe COVID-19, include old age, type 2 diabetes, obesity, asthma, and cardiovascular disease, all of which are associated with oxidative stress and increased NLRP3 activation122-131. Additionally, deficits of GSH, cysteine, hydrogen sulfide, selenium and vitamin D bring a higher risk of severe COVID132-139, while these factors normally serve to suppress NLRP3 activity140-143. Thus, a higher risk for severe COVID-19 is linked to NLRP3 activation and diminished antioxidant resources.

Interestingly, a study published in May 2019 by researchers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology showed that cytokine production in response to coronavirus infection was dampened in the immune cells of bats, as compared to humans, allowing bats to serve as a viral reservoir

144. Their studies identified differences in the molecular composition of NLRP3 that were specifically responsible for higher cytokine production by human cells and, by extension, the higher virulence of coronavirus infection in humans vs. bats. Specifically, they attributed this species difference to the leucine-rich repeat (LRR) portion of the NLRP3 molecule, which may be involved in oxidative stress-induced activation (see

Figure 2). This intriguing observation strongly suggests that the severity of cytokine-mediated inflammation may be influenced by the redox status of NLRP3 LRR cysteine residues.

The COVID-19 vaccination program spurred generally unfounded safety concerns that have contributed to vaccination hesitancy in the general public145, particularly since RNA-based vaccines represent a relatively new approach. Since the immune response to COVID-19 vaccines is based upon antigenicity of spike protein146, it is reasonable to expect that immune activation responses from vaccination would parallel those observed for COVID-19 infection. Indeed, NLRP3 was identified as an important determinant of antibody titer in both initial and booster responses to the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, with two genetic variants each having a significant impact147. The relatively rare occurrences of COVID vaccine-induced myopericarditis148, and vaccine-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia149 have both been linked to NLRP3 activation. Strong NLRP3 activation was also associated with rare occurrences of anaphylaxis following COVID vaccination150. Notably, spike protein exclusively elicited long-lived NLRP3 and caspase-1 expression in peripheral blood monocytic cells (PBMCs) of COVID-19 patients but not in uninfected controls, including epigenetic changes151. NLRP3-mediated inflammation can therefore be expected to play a significant role in long COVID and will be an ongoing concern with the transition to endemic COVID-19.

8. Implications and recommendations

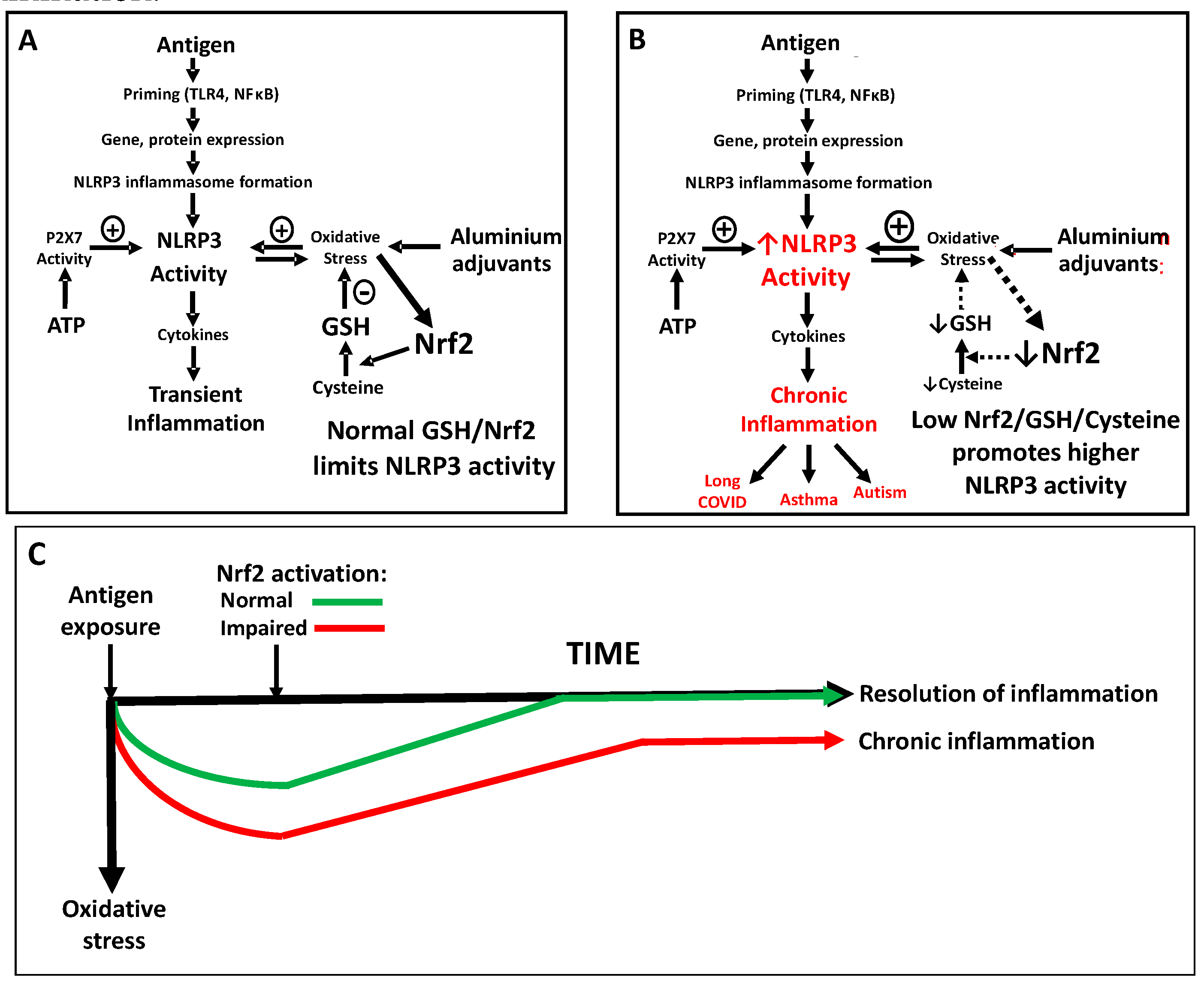

Recognition of the relationship between oxidative stress, NLRP3-mediated inflammation, and autism provides a useful mechanistic insight to understand the interrelation between immune system disorders, the everchanging nature of modern day inflammatory/ immunogenic insults (including vaccinations and the changing microbiome) and the progressive increase in autism prevalence over recent decades. A wide range of contemporary environmental factors (food and air quality, toxic exposures etc.) can converge to deplete antioxidant resources within and across generations, progressively increasing the prevalence of individuals with oxidative stress. As summarized in

Figure 3, we propose that while vaccination-induced inflammation is normally mild and self-limiting (

Figure 3A), individuals with abnormally low antioxidant resources (i.e. low cysteine and/or low GSH) exhibit a higher level of NLRP3-mediated inflammasome activation in response to provocative stimuli and particularly in response to adjuvanted vaccines, which are known to promote NLRP3 activity (

Figure 3B). We also propose that augmented acute responses in this vulnerable subgroup are also accompanied by an inability to fully suppress cytokine production to below threshold levels, due to deficient antioxidant resources and low Nrf2 activity, leading to a chronic inflammatory state (

Figure 3C), which is well-documented in autism. Thus, activation of inflammation by vaccine antigens provides an acute triggering event for a metabolically vulnerable subgroup of individuals, and the inclusion of oxidative stress-promoting aluminum adjuvants further augments their risk of chronic inflammation.

The increasing prevalence of asthma, atopy, allergy and/or other manifestations of inflammation and autoimmunity reflects an urgent need to investigate their underlying precipitating factors. Moreover, NLRP3 activation and inflammation are associated with numerous disorders, suggesting an important underlying role for environmental factors such as oxidative stress which interact with genetic factors to determine individual risk. It is also crucial to appreciate that the immune system of infants and young children differs from that of adults, although in many cases the difference in their vaccines is simply a reduction in dose. In early life, the immune response is shifted toward a Th2 pattern associated with hypersensitivity and allergic responses152.

The molecular composition of NLRP3 is well-suited to be a sensor of intracellular redox status, as is its glutathionylation-dependent complexation of ASC and NEK-7. In the latter case, NEK-7 binding to NLRP3 is mutually exclusive with its crucial role in mitosis153, and restriction of cell division during inflammation may be viewed as a compensatory response to limited antioxidant resources. These events appear to also apply to neural stem cell division during early brain development154, which could restrict the formation of neural networks, especially fast-firing parvalbumin-expressing interneuron networks, which have a high metabolic demand and are prominently depleted in postmortem autism brains155,156.

So, in light of the link between oxidative stress, NLRP3-mediated inflammation and autism, is it possible and/or feasible to identify higher-risk individuals with low antioxidant resources prior to vaccination and/or to reduce their risk of excessive inflammation? Identification of risk-related SNPs in Nrf2, NLRP3 or other inflammasome-related genes may be possible as genome sequencing/ genotyping becomes more generally accessible. Unfortunately, laboratory measurement of plasma cysteine/GSH redox status is not a routine clinical assay and currently is largely restricted to research studies. However, Jones and colleagues demonstrated a direct relationship between plasma levels of IL-1β and TNF-α in healthy human subjects and the cysteine redox potential, as determined by the concentration of reduced cysteine to cystine, its oxidized disulfide form157. Moreover, in animal studies they showed that dietary supplementation of sulfur amino acids cystine and methionine decreased IL-1β and TNF-α levels after LPS treatment. These findings, illustrate a potential metabolic approach to mitigate the risk of excessive inflammation in susceptible individuals and/or effectively treat their inflammation-related sequelae by supplementing thiol resources. Additional approaches could include promotion of Nrf2 activity or decreasing levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Further research is needed to confirm and delineate the role of oxidative stress in determining the magnitude and duration of NLRP3 activation following vaccination with and without adjuvanted vaccines and the types of adjuvants. Such research should include adequately powered prospective studies to examine the benefits and limitations of supplementing antioxidant resources before and/or after vaccine administration for at-risk populations. Family history of long-lasting inflammatory states (such as long Covid) and prior vaccination experience provide an opportunity to identify and prioritize at-risk individuals for testing and/or intervention, along with other factors such as hypersensitivity/allergy, gastrointestinal dysfunction, casein/gluten intolerance, etc.

Promotion of NLRP3 activity by oxidative stress is likely to play a prominent role in a wide range of poorly understood inflammation-related conditions, such as myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), long COVID, Alzheimer’s disease, and other disorders associated with aging. Indeed, a progressive age-dependent decrease in cysteine/cystine and GSH/GSSG redox potentials forms the basis for a “Redox Theory of Aging”158. While epigenetic-based metabolic adaptations triggered by oxidative stress and decreased methylation may serve to maintain redox status within a desirable homeostatic range over the lifespan, exhaustion of these compensatory mechanisms can result in pathological consequences, including activation of inflammation.

The perspective we present herein is subject to a number of limitations. First and foremost, it is a hypothesis that must be subject to testing and verification. For example, studies could evaluate the magnitude and duration of vaccination-induced inflammasome activation and inflammation in animals with normal vs. depleted thiol resources, including a comparison of aluminum-adjuvanted and non-adjuvanted vaccines. These studies could be conducted in animal models of autism, such as maternal immune activation or the BTBR mouse strain. Similarly, human studies could prospectively evaluate the relationship between inflammatory response to vaccination and plasma/PBMC thiol levels. Such studies would be of particular importance for autism families. While multiple studies have reported no link between vaccinations and autism159,160, none have specifically investigated the potential role of thiol status as a determinant of vaccination response and the vulnerability of a metabolically-defined subpopulation could be readily masked by the larger population.

In summary, recent advances in our understanding of NLRP3 inflammasome regulation require re-examination of the relationship between autism, neuroinflammation and vaccination. Moreover, it is important to recognize that medical interventions such as vaccination do not impact everyone in the same way. By acknowledging and addressing this concern, population-wide public health measures, including vaccinations, could be optimized to better support vulnerable subgroups, while preserving their benefit for the general population. A thorough mechanism-based understanding of the potential adverse consequences of vaccinations in stratified populations could facilitate fine-tuning and personalization of this crucial public health measure that will increase public confidence while optimizing the risk vs. benefit profile.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Sweta Shah for her help in the early stages of manuscript development.

Conflicts of Interest

RD has previously served as an expert witness in vaccination-related court cases.

References

- Daley, M.F.; et al. , Association between aluminum exposure from vaccines before age 24 Months and persistent asthma at age 24 to 59 months. Acad Pediatr. 2023, 23, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W. C.; et al. The NLR gene family: from discovery to present day. Nature Reviews. Immunology, 2023, 23, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; et al. Vaccine adjuvants: mechanisms and platforms. Signal transduction and targeted therapy, 2023, 8, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbarth, S.C.; et al. Crucial role for the Nalp3 inflammasome in the immunostimulatory properties of aluminium adjuvants. Nature. 2008, 453, 1122–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aimanianda, V.; et al. Novel cellular and molecular mechanisms of induction of immune responses by aluminum adjuvants. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009, 30, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinke, S.; et al. Inflammasome-mediated immunogenicity of clinical and experimental vaccine adjuvants. Vaccines (Basel). 2020, 8, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcón-Cama, V.; et al. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in postmortem lung, kidney, and liver samples, revealing cellular targets involved in COVID-19 pathogenesis. Arch Virol. 2023, 168, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baena Carstens, L.; et al. Lung inflammasome activation in SARS-CoV-2 post-mortem biopsies. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 13033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toldo, S.; et al. Inflammasome formation in the lungs of patients with fatal COVID-19. Inflamm Res. 2021, 70, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.S.; et al. Inflammasomes are activated in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and are associated with COVID-19 severity in patients. J Exp Med. 2021, 218, e20201707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, M.Z.; Kucia, M. SARS-CoV-2 infection and overactivation of Nlrp3 inflammasome as a trigger of cytokine "storm" and risk factor for damage of hematopoietic stem cells. Leukemia. 2020, 34, 1726–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariathasan, S.; et al. Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature. 2006, 440, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; et al. ATP exposure stimulates glutathione efflux as a necessary switch for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Redox Biol. 2021, 41, 101930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Tardivel, A.; Thorens, B. Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol. 2010, 11, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, T.; De Rosny, C.; Chautard, S. NLRP3 phosphorylation in its LRR domain critically regulates inflammasome assembly. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmo, A.; et al. A mechanistic insight into curcumin modulation of the IL-1β secretion and NLRP3 S-glutathionylation induced by needle-like cationic cellulose nanocrystals in myeloid cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2017, 274, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, F.; Molawi, K.; Zychlinsky, A. Superoxide dismutase 1 regulates caspase-1 and endotoxic shock. Nat Immunol. 2008, 9, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, M.M.; et al. Glutathione transferase omega-1 regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation through NEK7 deglutathionylation. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; et al. ASC deglutathionylation is a checkpoint for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Exp Med. 2021, 218, e20202637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzen, I.; Eble, J.A.; Hanschmann, EM. Thiol switches in membrane proteins - Extracellular redox regulation in cell biology. Biol Chem. 2020, 402, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, H.; et al. Structural mechanism for NEK7-licensed activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2019, 57, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, S.F.; et al. Structural and mechanistic aspects of S-S bonds in the thioredoxin-like family of proteins. Biol Chem. 2019, 400, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroder, K.; Zhou, R.; Tschopp, J. The NLRP3 inflammasome: a sensor for metabolic danger? Science. 2010, 327, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, M.T.; Oberg, A.L.; Grill, DE. System-wide associations between DNA-methylation, gene expression, and humoral immune response to influenza vaccination. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e0152034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tastan, B.; Arioz, B.I.; Genc, S. Targeting NLRP3 Inflammasome with Nrf2 Inducers in Central Nervous System Disorders. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 865772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; et al. Advances in the molecular mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activators and inactivators. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020, 175, 113863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.M.; et al. Nrf2 signaling pathway: Pivotal roles in inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; et al. An Overview of Nrf2 Signaling Pathway and Its Role in Inflammation. Molecules. 2020, 25, 5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; et al. Hydrogen Sulfide Contributes to Uterine Quiescence Through Inhibition of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Suppressing the TLR4/NF-κB Signalling Pathway. J Inflamm Res. 2021, 14, 2753–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; et al. Endogenous hydrogen sulphide attenuates NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuroinflammation by suppressing the P2X7 receptor after intracerebral haemorrhage in rats. J Neuroinflammation. 2017, 14, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Y.J.; et al. Cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activation via redox regulation in microglia. Antioxid Redox Signal, Epub ahead of print September 5, 2023. 5 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, H.; et al. Sulfur metabolic response in macrophage limits excessive inflammatory response by creating a negative feedback loop. Redox Biol. 2023, 65, 102834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; et al. Research progress of aluminum phosphate adjuvants and their action mechanisms. Pharmaceutics. 2023, 15, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinke, S.; et al. Inflammasome-mediated immunogenicity of clinical and experimental vaccine adjuvants. Vaccines (Basel). 2020, 8, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisonneuve, C.; Bertholet, S.; Philpott, D.J.; De Gregorio, E. Unleashing the potential of NOD- and Toll-like agonists as vaccine adjuvants. Proc Natl Acad Sci. USA. 2014, 111, 12294–12299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Hu, J. The integrated consideration of vaccine platforms, adjuvants, and delivery routes for successful vaccine development. Vaccines (Basel). 2023, 11, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauss, S.R. Aluminium adjuvants versus placebo or no intervention in vaccine randomised clinical trials: a systematic review with meta-analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis. BMJ Open. 2022, 12, e058795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exley, C. ; Aluminium-based adjuvants should not be used as placebos in clinical trials. Vaccine 2011, 29, 9289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terhune, T.D.; Deth, R.C. A role for impaired regulatory T cell function in adverse responses to aluminum adjuvant-containing vaccines in genetically susceptible individuals. Vaccine. 2014, 32, 5149–5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhune, T.D.; Deth, R.C. Aluminum adjuvant-containing vaccines in the context of the hygiene hypothesis: A risk factor for eosinophilia and allergy in a genetically susceptible subpopulation? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018, 15, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimzadeh, M. R.; et al. Aluminum poisoning with emphasis on its mechanism and treatment of intoxication. Emerg Med Int. 2022, 2022, 1480553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiró-Quirino, L.; Lima, W.F; Aragão, W.A.B. Exposure to tolerable concentrations of aluminum triggers systemic and local oxidative stress and global proteomic modulation in the spinal cord of rats. Chemosphere. 2023, 313, 137296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; et al. Aluminum activates NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis via reactive oxygen species to induce liver injury in mice. Chem Biol Interact. 2022, 368, 110229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.; et al. Aluminum impairs cognitive function by activating DDX3X-NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis signaling pathway. Food Chem Toxicol. 2021, 157, 112591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbarth, S.C.; et al. Crucial role for the Nalp3 inflammasome in the immunostimulatory properties of aluminium adjuvants. Nature. 2008, 453, 1122–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laupèze, B.; et al. Adjuvant Systems for vaccines: 13 years of post-licensure experience in diverse populations have progressed the way adjuvanted vaccine safety is investigated and understood. Vaccine. 2019, 37, 5670–5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, K.L.; Joffe, A.; Leitner, W.W. Review: Current trends, challenges, and success stories in adjuvant research. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1105655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haspeslagh, E.; et al. Murine Models of Allergic Asthma. Methods Mol Biol. 2017, 1559, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ruwona, T.B.; et al. Toward understanding the mechanism underlying the strong adjuvant activity of aluminum salt nanoparticles. Vaccine. 2016, 34, 3059–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomljenovic., L.; Shaw, C.A. Do aluminum vaccine adjuvants contribute to the rising prevalence of autism? J Inorg Biochem. 2011, 105, 1489–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.A.; Li, Y.; Tomljenovic, L. Administration of aluminium to neonatal mice in vaccine-relevant amounts is associated with adverse long term neurological outcomes. J Inorg Biochem. 2013, 128, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virk, S.A.; Eslick, G.D. Aluminum levels in brain, serum, and cerebrospinal fluid are higher in Alzheimer's disease cases than in controls: A series of meta-analyses. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015, 47, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exley, C.; Clarkson, E. Aluminium in human brain tissue from donors without neurodegenerative disease: A comparison with Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis and autism. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 7770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismael, S.; et al. ER stress associated TXNIP-NLRP3 inflammasome activation in hippocampus of human Alzheimer's disease. Neurochem Int. 2021, 148, 105104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vontell, R.T.; et al. Identification of inflammasome signaling proteins in neurons and microglia in early and intermediate stages of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Pathol. 2022, e13142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonen, S.; et al. Pyroptosis in Alzheimer's disease: cell type-specific activation in microglia, astrocytes and neurons. Acta Neuropathol. 2023, 145, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, A.M.E.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of phytochemicals against aluminum chloride-induced Alzheimer's disease through ApoE4/LRP1, Wnt3/β-Catenin/GSK3β, and TLR4/NLRP3 pathways with physical and mental activities in a rat model. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022, 15, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.H.M.; et al. Aluminum Activates PERK-EIF2α Signaling and Inflammatory Proteins in Human Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y Cells. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2016, 172, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.; et al. Role of NLRP3 Inflammasome and its inhibitors as emerging therapeutic drug candidate for Alzheimer's disease: a review of mechanism of activation, regulation, and inhibition. Inflammation. 2023, 46, 56–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, S.; et al. Polymorphisms in the IL-18 gene are associated with specific sensitization to common allergens and allergic rhinitis. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 111, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imboden, M.; et al. The common G-allele of IL-18 single nucleotide polymorphism is a genetic risk factor for atopic asthma. The SAPALDIA Cohort Study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005, 36, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, N.; et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of the IL-18 gene are associated with atopic eczema. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005, 115, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakashita, M.; et al. Association of serum IL-33 level and the IL-33 genetic variant with Japanese cedar pollinosis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008, 38, 1875–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudbjartsson, D.F.; et al. Sequence variants affecting eosinophil numbers associate with asthma and myocardial infarction. Nat Genet. 2009, 41, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.Q.; et al. Genetic variants of the IL-13 and IL-4 genes and atopic diseases in at-risk children. Genes Immun. 2003, 4, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabesch, M.; et al. IL-4/IL-13 pathway genetics strongly influence serum IgE levels and childhood asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 117, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demenais, F.; et al. Australian Asthma Genetics Consortium (AAGC) collaborators. Multiancestry association study identifies new asthma risk that colocalize with immune-cell enhancer marks. Nat Genet. 2018, 50, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seumois, G.; et al. Epigenomic analysis of primary human T cells reveals enhancers associated with TH2 memory cell differentiation and asthma susceptibility. Nat Immunol. 2014, 15, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, I.V.; et al. DNA methylation and childhood asthma in the inner city. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015, 136, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; et al. Association of glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 genotypes with asthma: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020, 34, e21732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Dou, Y.; Hogaboam, C.M.; Kunkel, S.L. Epigenetic regulation of dendritic cell-derived IL-12 facilitates immunosuppression after a severe innate immune response. Blood. 2008, 111, 1797–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünig, G.; et al. Requirement for IL-13 independently of IL-4 in experimental asthma. Science. 1998, 282, 2261–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, S.P.; Koskinen, A.; Foster, P.S. Interleukin-5 and eosinophils induce airway damage and bronchial hyperreactivity during allergic airway inflammation in BALB/c mice. Immunol Cell Biol. 1997, 75, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wills-Karp, M.; et al. Interleukin-13: central mediator of allergic asthma. Science. 1998, 282, 2258–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, L.; Homer, R.J.; Niu, N.; Bottomly, K. T helper 1 cells and interferon gamma regulate allergic airway inflammation and mucus production. J Exp Med. 1999, 190, 1309–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavett, S.H.; et al. Interleukin 12 inhibits antigen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness, inflammation, and Th2 cytokine expression in mice. J Exp Med. 1995, 182, 1527–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newport, M.J.; Goetghebuer, T.; Weiss, H.A. Genetic regulation of immune responses to vaccines in early life. Genes Immunity. 2004, 5, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baynam, G.; et al. Parental smoking impairs vaccine responses in children with atopic genotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007, 119, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baynam, G.; et al. Gender-specific effects of cytokine gene polymorphisms on childhood vaccine responses. Vaccine. 2008, 26, 3574–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiertsema, S.P.; et al. Impact of genetic variants in IL-4, IL-4 RA, and IL-13 on the anti-pneumococcal antibody response. Vaccine. 2007, 25, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhune, T.D.; Deth, R.C. How aluminum adjuvants could promote and enhance non-target IgE synthesis in a genetically-vulnerable sub-population. J Immunotoxicol. 2012, 10, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantani, A. (Ed.) Pediatric Allergy. In Asthma and Immunology; Springer: New York, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, N.; et al. Family History and Improving Health. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Evidence Reports/Technology Assessment. 2009, 186. [Google Scholar]

- Glanz, J.M.; et al. White Paper on studying the safety of the childhood immunization schedule in the Vaccine Safety Datalink. Vaccine. 2016, 34 Suppl 1, A1–A29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maenner, M.J.; et al. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 Years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2023, 72, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; et al. Oxidative stress marker aberrations in children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 87 studies (N = 9109). Transl Psychiatry. 2021, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.J.; et al. Metabolic biomarkers of increased oxidative stress and impaired methylation capacity in children with autism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004, 80, 1611–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efe, A.; Neşelioğlu, S.; Soykan, A. An investigation of the dynamic thiol/disulfide homeostasis, as a novel oxidative stress plasma biomarker, in children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, A.; Audhya, T.; Chauhan, V. Brain region-specific glutathione redox imbalance in autism. Neurochem Res. 2012, 37, 1681–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.; et al. Evidence of oxidative damage and inflammation associated with low glutathione redox status in the autism brain. Transl Psychiatry. 2012, 2, e134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endres, D.; et al. Glutathione metabolism in the prefrontal brain of adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: an MRS study. Mol Autism. 2017, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, D.L.; et al. Neuroglial activation and neuroinflammation in the brain of patients with autism. Ann Neurol. 2005, 57, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, A.M.; et al. Aberrant NF-kappaB expression in autism spectrum condition: a mechanism for neuroinflammation. Front Psychiatry. 2011, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, M.; et al. Blood-brain barrier and intestinal epithelial barrier alterations in autism spectrum disorders. Mol Autism. 2016, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.S.; Azmitia, E.C.; Whitaker-Azmitia, P.M. Developmental microglial priming in postmortem autism spectrum disorder temporal cortex. Brain Behav Immun. 2017, 62, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; et al. Neuron-specific transcriptomic signatures indicate neuroinflammation and altered neuronal activity in ASD temporal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023, 120, e2206758120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, X.; Chen, M.; Li, Y. The glial perspective of autism spectrum disorder convergent evidence from postmortem brain and PET studies. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2023, 70, 101064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jyonouchi, H.; Sun, S.; Le, H. Proinflammatory and regulatory cytokine production associated with innate and adaptive immune responses in children with autism spectrum disorders and developmental regression. J Neuroimmunol. 2001, 120, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashwood, P.; et al. Elevated plasma cytokines in autism spectrum disorders provide evidence of immune dysfunction and are associated with impaired behavioral outcome. Brain Behav Immun. 2011, 25, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolioni, V.; et al. Plasma cytokine profiling in sibling pairs discordant for autism spectrum disorder. J Neuroinflammation. 2013, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, A.; et al. Cytokine aberrations in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2015, 20, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saresella, M.; et al. Multiple inflammasome complexes are activated in autistic spectrum disorders. Brain Behav Immun. 2016, 57, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwood, P.; et al. Preliminary evidence of the in vitro effects of BDE-47 on innate immune responses in children with autism spectrum disorders. J Neuroimmunol. 2009, 208, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.B.; Gao, S.J.; Zhao, H.X. Thioredoxin: a novel, independent diagnosis marker in children with autism. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2015, 40, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abruzzo, P.M.; et al. Plasma peroxiredoxin changes and inflammatory cytokines support the involvement of neuro-inflammation and oxidative stress in autism spectrum disorder. J Transl Med. 2019, 17, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCall, C.E.; et al. Epigenetics, bioenergetics, and microRNA coordinate gene-specific reprogramming during acute systemic inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2011, 90, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli, F.; et al. How aging and oxidative stress influence the cytopathic and inflammatory effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection: The role of cellular glutathione and cysteine metabolism. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022, 11, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, G.S.; et al. Evidence for oxidative stress and defective antioxidant response in guinea pigs with tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2011, 6, e26254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napoli, E.; et al. Deficits in bioenergetics and impaired immune response in granulocytes from children with autism. Pediatrics. 2014, 133, e1405–e1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrier, M.S.; et al. Decreased cortical Nrf2 gene expression in autism and its relationship to thiol and cobalamin status. Biochimie. 2022, 192, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, M.E.; et al. Evaluation of the toxic effects of thimerosal and/or aluminum hydroxide in SH-SY5Y cell line. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2022, 41, 9603271221136206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, K.; et al. Transport and toxic mechanism for aluminum citrate in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Life Sci. 2006, 79, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzio, N.M.; et al. Cytokine levels during pregnancy influence immunological profiles and neurobehavioral patterns of the offspring. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007, 1107, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbo, S.D.; et al. Beyond infection - Maternal immune activation by environmental factors, microglial development, and relevance for autism spectrum disorders. Exp Neurol 2018, 299(Pt A), 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; et al. Early postnatal lipopolysaccharide exposure leads to enhanced neurogenesis and impaired communicative functions in rats. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e0164403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristino, L.M.F.; et al. Animal model of neonatal immune challenge by lipopolysaccharide: A study of sex influence in behavioral and immune/neurotrophic alterations in juvenile mice. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2022, 29, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usui, N.; Kobayashi, H.; Shimada, S. Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabó, D.; et al. Maternal P2X7 receptor inhibition prevents autism-like phenotype in male mouse offspring through the NLRP3-IL-1β pathway. Brain Behav Immun. 2022, 101, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horváth, G.; et al. P2X7 receptors drive poly(I:C) induced autism-like behavior in mice. J Neurosci. 2019, 39, 2542–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naviaux, J.C.; et al. Reversal of autism-like behaviors and metabolism in adult mice with single-dose antipurinergic therapy. Transl Psychiatry. 2014, 4, e400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naviaux, R.K.; et al. Low-dose suramin in autism spectrum disorder: a small, phase I/II, randomized clinical trial. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2017, 4, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abderrazak, A.; et al. NLRP3 inflammasome: from a danger signal sensor to a regulatory node of oxidative stress and inflammatory diseases. Redox Biol. 2015, 4, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome in fibrosis and aging: The known unknowns. Ageing Res Rev. 2022, 79, 101638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, A.K.; Zhu, X. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: Metabolic regulation and contribution to inflammaging. Cells. 2020, 9, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, K.; Zhou, R.; Tschopp, J. The NLRP3 inflammasome: a sensor for metabolic danger? Science. 2010, 327, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, I.N.; et al. Thioredoxin interacting protein, a key molecular switch between oxidative stress and sterile inflammation in cellular response. World J Diabetes. 2021, 12, 1979–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; et al. Role of the inflammasome in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1052756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, H.M.; Wanderer, A.A. Inflammasome and IL-1beta-mediated disorders. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2010, 10, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; et al. The role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in chronic inflammation in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2022, 10, e750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, N.J. Inflammasomes in cardiovascular diseases. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2011, 1, 244–254. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; et al. NLRP3 inflammasome: The rising star in cardiovascular diseases. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022, 9, 927061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Alonso, J.L.; et al. N-acetylcysteine for prevention and treatment of COVID-19: Current state of evidence and future directions. J Infect Public Health. 2022, 15, 1477–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgonje, A.R.; et al. N-Acetylcysteine and hydrogen sulfide in coronavirus disease 2019. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2021, 35, 1207–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.K.; Micinski, D.; Parsanathan, R. l-Cysteine stimulates the effect of vitamin D on inhibition of oxidative stress, IL-8, and MCP-1 secretion in high glucose treated monocytes. J Am Coll Nutr. 2021, 40, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- .

- Soto, M.E.; et al. N-Acetyl Cysteine Restores the Diminished Activity of the Antioxidant Enzymatic System Caused by SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Preliminary Findings. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023, 16, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renieris, G.; et al. Serum hydrogen sulfide and outcome association in pneumonia by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. Shock. 2020, 54, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; et al. Association between regional selenium status and reported outcome of COVID-19 cases in China. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020, 111, 1297–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jude, E.B.; et al. Vitamin D deficiency Is associated with higher hospitalization risk from COVID-19: A retrospective case-control study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021, 106, e4708–e4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; et al. Is nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 a target for the intervention of cytokine storms? Antioxidants (Basel). 2023, 12, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.B.; et al. Selenium attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity through Nrf2-NLRP3 pathway. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2022, 200, 2848–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.L.; et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates neuroinflammation by inhibiting the NLRP3/Caspase-1/GSDMD pathway in retina or brain neuron following rat ischemia/reperfusion. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; et al. 1,25-Dihydroxy vitamin D3 attenuates the oxidative stress-mediated inflammation induced by PM2.5 via the p38/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway. Inflammation. 2019, 42, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M.; et al. Dampened NLRP3-mediated inflammation in bats and implications for a special viral reservoir host. 2019, 4, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, H.J.; Gakidou, E.; Murray CJL. The Vaccine-Hesitant Moment. N Engl J Med. 2022, 387, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, F. X.; Stiasny, K. Distinguishing features of current COVID-19 vaccines: knowns and unknowns of antigen presentation and modes of action. NPJ vaccines. 2021, 6, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemoto, Y.; et al. Multi-phasic gene profiling using candidate gene approach predict the capacity of specific antibody production and maintenance following COVID-19 vaccination in Japanese population. Frontiers in immunology. 2023, 14, 1217206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, T.; et al. (2022). Increased interleukin 18-dependent immune responses are associated with myopericarditis after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. Frontiers in immunology. 2022, 13, 851620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashir, J.; et al. Scientific premise for the involvement of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in vaccine-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT). Journal of leukocyte biology, 2022, 111, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H. L.; et al. In vitro vaccine challenge of PBMCs from BNT162b2 anaphylaxis patients reveals HSP90α-NOD2-NLRP3 nexus. Allergy. 2023, 78, 304–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theobald, S. J.; et al. Long-lived macrophage reprogramming drives spike protein-mediated inflammasome activation in COVID-19. EMBO molecular medicine, 2021, 13, e14150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, J.W.; et al. Dendritic cell immaturity during infancy restricts the capacity to express vaccine-specific T-cell memory. Infect Immun. 2006, 74, 1106–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; et al. NLRP3 activation and mitosis are mutually exclusive events coordinated by NEK7, a new inflammasome component. Nat Immunol. 2016, 17, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; et al. Neuroinflammation induction and alteration of hippocampal neurogenesis in mice following developmental exposure to gossypol. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021, 24, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez, P.; Martínez Cerdeño, V. Parvalbumin and parvalbumin chandelier interneurons in autism and other psychiatric disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2022, 13, 913550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contractor, A.; Ethell, I.M.; Portera-Cailliau, C. Cortical interneurons in autism. Nat Neurosci. 2021, 24, 1648–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, S.S.; et al. Cysteine redox potential determines pro-inflammatory IL-1beta levels. PLoS One. 2009, 4, e5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Go, Y.M. and Jones, D.P. Redox theory of aging: implications for health and disease. Clin Sci (Lond). 2017, 131, 1669–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Immunization Safety Review Committee. Immunization Safety Review: Vaccines and Autism. Washington (DC); National Academies Press (US): Washington (DC), 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (US) Adverse Effects of Vaccines: Evidence and Causality; National Academies Press (US): Washington (DC), 2012. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).