1. Introduction

Controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) is an essential component of assisted reproductive technologies (ART), which primarily aim to improve oocyte yield during retrieval. Although this strategy increases reproductive success, it also carries the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). While OHSS can occur spontaneously1, it is primarily an iatrogenic consequence of COS, particularly in women undergoing ART. Moderate to severe OHSS occurs in approximately 3 to 10 % of ART cycles, although this figure can rise to 20 % in high-risk groups2.

Effective OHSS risk management depends on recognizing the key predictors3. Elevated anti-Mullerian hormone levels and an increased number of antral follicles are important risk indicators. In addition, a high ovarian response, characterized by numerous dominant follicles, elevated estradiol levels at the time of ovulation induction and the retrieval of several oocytes, serves as a reliable marker of OHSS risk. Personalizing ovarian stimulation protocols based on these risk factors is critical to protecting patient health.

Various fertility preservation methods are currently available to increase the likelihood of future pregnancy in patients receiving cancer treatment who are at risk of ovarian failure after completion of therapy4. Some established methods of fertility preservation, including oocyte and/or embryo cryopreservation, require COS as a crucial part of the process. For these patients, the problem of OHSS becomes even more complex. In addition to the physical and emotional stress of the cancer diagnosis and impending treatment, these patients face the additional risks of OHSS, including increased risk of thromboembolism, possible delays in cancer treatment, and increased emotional stress.

Recently, the simultaneous use of several fertility preservation strategies in individual patients has been increasingly used to optimize the prospects of future pregnancies. In this context, the administration of long-term gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists is frequently observed in women who have undergone oocyte retrieval for oocyte and/or embryo cryopreservation. However, there are reports of OHSS in women who have undergone COS followed by treatment with long-term GnRH agonists5, 6, despite having no other identifiable risk factors for this complication. A comprehensive understanding of both the pathophysiology of OHSS and the various fertility preservation techniques is crucial, especially for oncology patients. This knowledge enables healthcare professionals to develop personalized, patient-tailored plans that effectively minimize both the incidence and severity of OHSS.

This narrative review addresses the pathophysiology of OHSS, specially in the context of the use of GnRH agonist in cancer patients. Our discussion pivots on discussing innovative strategies, particularly emphasizing the potential of GnRH antagonists as a safer and more effective alternative for managing OHSS risk in this particular patient population. By exploring these avenues, we aim to align fertility preservation efforts with the broader health and treatment goals of cancer patients and ensure a balanced and safe approach to their reproductive journey.

2. Pathophysiology of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome is a complex and multifaceted condition that occurs primarily as a complication of COS. The pathophysiology of OHSS is multifaceted and involves a number of biological processes ranging from vascular changes to cytokine-mediated responses.

Central to the pathophysiology of OHSS is the phenomenon of marked arteriolar vasodilation associated with increased capillary permeability. This vascular response leads to a significant shift of fluid from the intravascular to the extravascular space and sets the stage for the clinical manifestations of the syndrome. A key factor in the development of OHSS is the administration of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which is commonly used to final follicular maturation. Human chorionic gonadotropin has a direct effect on the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a critical component in angiogenesis and increasing vascular permeability7. The severity of OHSS has been directly linked to VEGF levels, emphasizing the fundamental role of this growth factor in the pathogenesis of the syndrome8.

Controlled ovarian stimulation is accompanied by a biochemical cascade characterized by an overproduction of pro-inflammatory and vasoactive cytokines9. These cytokines primarily include interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), which play a crucial role in enhancing vascular permeability and underscore the inflammatory nature of OHSS.

The resulting increased vascular permeability and the consequent extravasation of protein-rich fluid into the extravascular space are responsible for the characteristic symptoms of OHSS such as bloating, ascites and generalized edema. This fluid shift not only underlies these clinical features, but also carries the risk of more serious complications, including hypovolemic shock and renal dysfunction.

3. Clinical presentation of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome manifests as a constellation of symptoms primarily caused by marked vascular permeability and ovarian enlargement following COS.

Early signs of OHSS typically include a distended abdomen and mild discomfort due to ovarian enlargement with cyst formation, which can reach a diameter of 12–25 cm10. These enlarged cystic ovaries carry the risk of rupture or hemorrhage leading to peritonitis and are prone to complications such as ovarian torsion11.

Increased capillary permeability leads to a significant shift of fluid into the third space, resulting in intravascular volume depletion. This underlies various clinical features that increase in severity with increasing involvement of multiple organ systems. Ascites, characterized by the accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity, often serves as the first indicator of OHSS and leads to abdominal pain and increased intra-abdominal pressure (IAP). Elevated IAP can develop into intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) and, in severe cases, abdominal compartment syndrome, which is characterized by a persistent elevated IAP and is associated with organ dysfunction7.

Oliguria is often an early sign of IAH. Impaired intra-abdominal venous outflow contributes to renal, intestinal and hepatic edema, which subsequently leads to liver damage, paralytic ileus and severe gastrointestinal symptoms. Elevated liver enzyme levels, such as aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase, are common in severe cases. Acute renal failure in OHSS is typically characterized by hyponatremia due to low serum osmolality and decreased urinary sodium excretion12.

Patients with OHSS may present with leukocytosis, increased hematocrit, and thrombocytosis, indicating hemoconcentration and inflammation. Such hemoconcentration predisposes patients to hypercoagulability, with thrombotic events occurring in up to 10% of severe cases13. The risk is further increased by factors such as compression of the pelvic vessels and underlying thrombophilia. Thrombosis primarily affects the venous system, although arterial embolism is also a problem14.

Patients diagnosed with ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome often presents immunodeficiency with reduced levels of the immunoglobulins IgA and IgG, which increases the risk of infections. A significant proportion of hospitalized patients may develop febrile episodes, with urinary tract infections, pneumonia and other site-specific infections being common15.

In critical cases, patients may experience hypovolemic shock, septic shock, distributive shock due to severe inflammation, or obstructive shock due to complications such as pericardial effusion or pulmonary embolism12. Pericardial effusions, which only occur in a minority of cases, rarely lead to tamponade16.

4. Interventions to reduce the risk of OHSS during COS

A number of interventions have been developed to reduce the risk of OHSS during COS, targeting specific elements of the pathophysiology.

Firstly, mild stimulation protocols are important. These involve the administration of daily FSH doses of 150 IU or less, a less aggressive approach compared to conventional methods. The advantage of these milder protocols is that they are associated with fewer adverse events, particularly a lower risk of OHSS. This is mainly due to the fact that the likelihood of OHSS is directly related to the intensity of ovarian stimulation17.

Another important intervention is the use of GnRH antagonists. These agents competitively bind to the natural GnRH receptors and immediately and reversibly suppress the release of gonadotropin. This prevents a premature LH surge during COS, allowing for shorter treatment protocols and lower gonadotropin doses. This not only reduces costs, but also significantly reduces the risk of OHSS by limiting gonadotropin overdose18.

The role of hCG in final follicular maturation is also crucial as it is closely linked to OHSS. Theoretically, bypassing hCG can mitigate OHSS-related complications, as OHSS cases without hCG are rare19. Options include either canceling the cycle prior to hCG administration or substituting GnRH agonists for hCG, thereby reducing the hCG dose20. However, these approaches can be emotionally and financially stressful3.

In addition, the 'freeze-all' strategy has proven to be a viable option. In this approach, all retrieved oocytes/embryos are cryopreserved after retrieval and embryo transfer is postponed to a later, non-stimulated cycle. By limiting exposure to hCG and avoiding prolonged exposure to natural hCG during pregnancy, which can exacerbate OHSS, this strategy serves as a preventative measure21.

Finally, cabergoline, a dopamine agonist, has demonstrated its potential to reduce vascular hyperpermeability, a key aspect of OHSS pathophysiology. In animal studies, cabergoline demonstrated its ability to inhibit the VEGF-2 receptor, thereby reducing vascular hyperpermeability without impairing luteal angiogenesis. These findings have led to clinical studies investigating the efficacy of cabergoline in the prevention of OHSS22.

5. OHSS in cancer patients referred for fertility preservation

Women of reproductive age who have been diagnosed with cancer face a double challenge: fighting their disease and preserving their fertility. The risk of ovarian failure and infertility resulting from the adverse effects of oncologic treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation underscores the importance of fertility preservation as an integral aspect of patient care23. For this reason, leading scientific societies have formulated comprehensive guidelines to address this complicated aspect of oncologic treatment24-27.

Early referral to a reproductive medicine specialist is a common thread in these guidelines, emphasizing the need for timely fertility preservation without delaying oncologic treatment. Established fertility preservation methods such as oocyte and/or embryo cryopreservation after COS and ovarian tissue cryopreservation are validated techniques that have been extensively proven to be effective in preserving reproductive potential after cancer treatment28-31.

The use of GnRH agonists as a pharmacological strategy for fertility preservation during chemotherapy, aimed at minimizing the number of follicles that can be damaged by chemotherapy and thereby reducing the risk of ovarian damage, is still the subject of experimental investigation and debate32-35. These agents induce an initial 'flare-up' effect characterized by a transient increase in gonadotropins that subsequently decreases due to downregulation of receptors, a phenomenon that lasts for about two weeks36. GnRH agonists, including triptorelin, leuprolide, goserelin and buserelin, are thought to reduce the risk of ovarian failure by creating a prepubertal hormonal environment and decreasing utero-ovarian perfusion37. Nevertheless, these agents have not received FDA approval specifically for fertility preservation and are often used "off label".

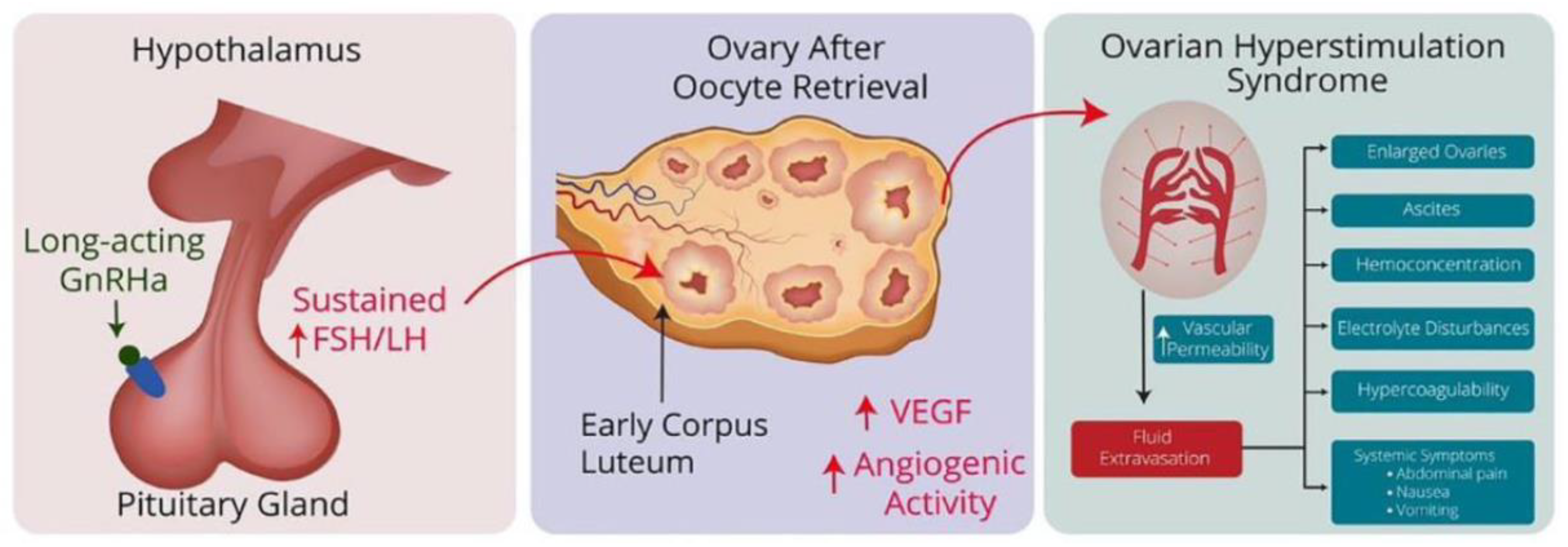

Although still considered experimental, physicians are increasingly using combined strategies for fertility preservation, such as the administration of a long-acting GnRH agonist after COS for fertility preservation by oocyte and/or embryo cryopreservation. However, this approach has been associated with the occurrence of OHSS

5, 6. The mechanism is a sustained increase in gonadotropins after treatment, which stimulates luteinizing hormone (LH) receptors in the ovaries and leads to an overproduction of angiogenic factors, eventually resulting in OHSS (

Figure 1).

For cancer patients undergoing fertility preservation, the urgency of starting chemotherapy poses a significant clinical dilemma. The development of OHSS may necessitate delaying critical cancer treatments, which can affect patients' prognosis38, 39. While OHSS is usually manageable with intensive medical intervention, its severe manifestations carry significant risks, including thromboembolism, renal failure and respiratory distress syndrome40.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical pathway of GnRH agonist-induced OHSS: Long-term administration of GnRHa triggers a flare-up effect by stimulating the pituitary gland, leading to a sustained increase in FSH and LH levels. These increased FSH and LH levels influence the corpus luteum in the ovaries after oocyte retrieval and cause them to release angiogenic factors such as VEGF. This increase in angiogenic factors increases vascular permeability, leading to fluid accumulation in the abdominal cavity and other areas, along with hemoconcentration, hypercoagulability and electrolyte disturbances, the characteristic features of OHSS. Adapted from Ingold et al.5.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical pathway of GnRH agonist-induced OHSS: Long-term administration of GnRHa triggers a flare-up effect by stimulating the pituitary gland, leading to a sustained increase in FSH and LH levels. These increased FSH and LH levels influence the corpus luteum in the ovaries after oocyte retrieval and cause them to release angiogenic factors such as VEGF. This increase in angiogenic factors increases vascular permeability, leading to fluid accumulation in the abdominal cavity and other areas, along with hemoconcentration, hypercoagulability and electrolyte disturbances, the characteristic features of OHSS. Adapted from Ingold et al.5.

6. GnRH Antagonists for Ovarian Suppression: A Comprehensive Clinical Evaluation

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists, which were developed from the natural GnRH decapeptide with various amino acid substitutions, have proven to be a promising alternative in reproductive medicine and gynecology.

Originally, GnRH antagonists were characterized by complex structures that led to adverse histamine-related side effects such as edematogenic reactions and anaphylaxis41. However, advances in pharmaceutical research have led to the development of improved GnRH antagonists that do not have these adverse effects. The newer generation of antagonists, characterized by specific amino acid changes and structural improvements, have an improved safety profile and greater efficacy42.

GnRH antagonists such as cetrorelix, ganirelix and degarelix have high receptor affinity and inhibitory activity, making them candidates for a range of clinical applications. Cetrorelix and Ganirelix in particular have been shown to be effective in controlling ovarian stimulation protocols, preventing premature LH surge in ART.

The administration of long-acting GnRH agonists initially triggers a 'flare-up effect' in hormone levels in the first few days after use. This effect is followed by a suppression of the hormone axis, which usually occurs one to two weeks later. Theoretically, the benefits of ovarian suppression would only be realized after this suppression phase. In clinical practice, treatment protocols vary considerably between medical centers43. One notable example is the timing of the first dose of agonist. In some cases, it is administered at the same time as the start of chemotherapy. This timing means that the patient may be undergoing chemotherapy precisely during the flare-up phase triggered by the GnRH agonist. In contrast to GnRH agonists, GnRH antagonists compete directly with natural GnRH for receptor binding. This competitive inhibition leads to a rapid and sustained reduction in follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and LH levels, bypassing the 'flare-up effect" typically associated with agonist use36.

The use of GnRH antagonists is also effective in preventing the early onset of OHSS and reducing its severity. This intervention works by inhibiting the release of LH from the pituitary gland, which in turn accelerates luteolysis44. This process leads to a significant decrease in serum VEGF45.

Although the benefits of using GnRH analogs to preserve ovarian function are unproven, GnRH antagonists represent a compelling option for fertility preservation, especially when used in combination with other methods, such as following controlled ovarian stimulation for cryopreservation of oocytes and/or embryos, particularly in scenarios where minimizing the risk of OHSS is of paramount importance. Their rapid suppression of gonadotropin secretion, without causing a 'flare-up', makes them a preferred alternative to GnRH agonists. This is particularly important in sensitive cases such as cancer patients undergoing fertility preservation, where minimizing the risk of OHSS is a major concern.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, there have been significant advances in the field of fertility preservation, particularly in relation to patients undergoing treatments such as chemotherapy who are at risk of ovarian failure. The strategic use of various fertility preservation methods, such as cryopreservation of oocytes and embryo cryopreservation and the administration of GnRH agonists, has opened up new possibilities for improving future pregnancy outcomes.

However, these interventions are not without challenges. The use of long-acting GnRH agonists, for example, is still considered experimental and controversial, as their 'flare-up' effect raises concerns about OHSS risk. While GnRH antagonists represent a promising approach to reducing the incidence and severity of OHSS, their use requires careful timing and monitoring.

The discussion around these interventions underscores the importance of a tailored, patient-centered approach to fertility preservation. Collaboration between oncologists, reproductive physicians and patients is essential to develop effective, safe and patient-specific fertility preservation strategies. The ultimate goal remains to provide patients undergoing potentially gonadotoxic treatment with safe and effective fertility preservation options that ensure a better quality of life after treatment and the ability to meet their reproductive goals in the future.

References

- Chai, W.; He, H.; Li, F.; Zhang, W.; He, C. Spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in a nonpregnant female patient: a case report and literature review. J Int Med Res 2020, 48, 300060520952647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.W.; Lee, V.C.; Lau, E.Y.; Yeung, W.S.; Ho, P.C.; Ng, E.H. Cumulative live-birth rate in women with polycystic ovary syndrome or isolated polycystic ovaries undergoing in-vitro fertilisation treatment. J Assist Reprod Genet 2014, 31, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastri, C.O.; Teixeira, D.M.; Moroni, R.M.; Leitao, V.M.; Martins, W.P. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: pathophysiology, staging, prediction and prevention. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015, 45, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldfarb, S.B.; Turan, V.; Bedoschi, G.; Taylan, E.; Abdo, N.; Cigler, T.; Bang, H.; Patil, S.; Dickler, M.N.; Oktay, K.H. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy or tamoxifen-alone on the ovarian reserve of young women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2021, 185, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, C.; Navarro, P.A.; de Oliveira, R.; Barbosa, C.P.; Bedoschi, G. Risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in women with malignancies undergoing treatment with long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist after controlled ovarian hyperstimulation for fertility preservation: a systematic review. Ther Adv Reprod Health 2023, 17, 26334941231196545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, C.; Bedoschi, G. Safety and efficacy concerns of long-acting GnRHa trigger for ovulation induction in oncological patients undergoing oocyte cryopreservation: a call for caution and further investigation. ESMO Open 2023, 8, 101825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmons, D.; Montrief, T.; Koyfman, A.; Long, B. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: A review for emergency clinicians. Am J Emerg Med 2019, 37, 1577–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.O.; Harper, S.J. Regulation of vascular permeability by vascular endothelial growth factors. Vascul Pharmacol 2002, 39, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, L.C.; Michalakis, K.G.; Browne, H.; Payson, M.D.; Segars, J.H. The pathophysiology of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: an unrecognized compartment syndrome. Fertil Steril 2010, 94, 1392–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvigne, A.; Rozenberg, S. Review of clinical course and treatment of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). Hum Reprod Update 2003, 9, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Navarro, N.; Garcia Grau, E.; Pina Perez, S.; Ribot Luna, L. Ovarian torsion and spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in a twin pregnancy: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2017, 34, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budev, M.M.; Arroliga, A.C.; Falcone, T. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Crit Care Med 2005, 33, S301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serour, G.I.; Aboulghar, M.; Mansour, R.; Sattar, M.A.; Amin, Y.; Aboulghar, H. Complications of medically assisted conception in 3,500 cycles. Fertil Steril 1998, 70, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, Y.S.; Schenker, J.G. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and thrombotic events. Am J Reprod Immunol 2014, 72, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramov, Y.; Elchalal, U.; Schenker, J.G. Febrile morbidity in severe and critical ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: a multicentre study. Hum Reprod 1998, 13, 3128–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marek, D.; Sovova, E.; Dostal, J.; Oborna, I.; Kocianova, E.; Machac, S.; Talas, M.; Lukl, J.; Brezinova, J. Incidence of pericardial effusion in females stimulated in "in vitro fertilization" program. Echocardiography 2006, 23, 729–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macklon, N.S.; Stouffer, R.L.; Giudice, L.C.; Fauser, B.C. The science behind 25 years of ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization. Endocr Rev 2006, 27, 170–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Inany, H.G.; Youssef, M.A.; Ayeleke, R.O.; Brown, J.; Lam, W.S.; Broekmans, F.J. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone antagonists for assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016, 4, CD001750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, H.M.; Popovic-Todorovic, B.; Humaidan, P.; Kol, S.; Banker, M.; Devroey, P.; Garcia-Velasco, J.A. Severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome after gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist trigger and "freeze-all" approach in GnRH antagonist protocol. Fertil Steril 2014, 101, 1008–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, J.; Turan, V.; Bedoschi, G.; Moy, F.; Oktay, K. Triggering final oocyte maturation with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) versus human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) in breast cancer patients undergoing fertility preservation: an extended experience. J Assist Reprod Genet 2014, 31, 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraretti, A.P.; Gianaroli, L.; Magli, C.; Fortini, D.; Selman, H.A.; Feliciani, E. Elective cryopreservation of all pronucleate embryos in women at risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: efficiency and safety. Hum Reprod 1999, 14, 1457–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, R.; Gonzalez-Izquierdo, M.; Zimmermann, R.C.; Novella-Maestre, E.; Alonso-Muriel, I.; Sanchez-Criado, J.; Remohi, J.; Simon, C.; Pellicer, A. Low-dose dopamine agonist administration blocks vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-mediated vascular hyperpermeability without altering VEGF receptor 2-dependent luteal angiogenesis in a rat ovarian hyperstimulation model. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 5400–5411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoschi, G.M.; Navarro, P.A.; Oktay, K.H. Novel insights into the pathophysiology of chemotherapy-induced damage to the ovary. Panminerva Med 2019, 61, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oktay, K.; Harvey, B.E.; Partridge, A.H.; Quinn, G.P.; Reinecke, J.; Taylor, H.S.; Wallace, W.H.; Wang, E.T.; Loren, A.W. Fertility Preservation in Patients With Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2018, 36, 1994–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambertini, M.; Peccatori, F.A.; Demeestere, I.; Amant, F.; Wyns, C.; Stukenborg, J.B.; Paluch-Shimon, S.; Halaska, M.J.; Uzan, C.; Meissner, J.; et al. Fertility preservation and post-treatment pregnancies in post-pubertal cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines(dagger). Ann Oncol 2020, 31, 1664–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preservation, E.G.G. o. F. F.; Anderson, R.A.; Amant, F.; Braat, D.; D'Angelo, A.; Chuva de Sousa Lopes, S.M.; Demeestere, I.; Dwek, S.; Frith, L.; Lambertini, M.; et al. ESHRE guideline: female fertility preservation. Hum Reprod Open 2020, 2020, hoaa052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Electronic address, a. a. o. Fertility preservation in patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapy or gonadectomy: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2019, 112, 1022–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoschi, G.; Oktay, K. Current approach to fertility preservation by embryo cryopreservation. Fertil Steril 2013, 99, 1496–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, K.; Turan, V.; Bedoschi, G.; Pacheco, F.S.; Moy, F. Fertility Preservation Success Subsequent to Concurrent Aromatase Inhibitor Treatment and Ovarian Stimulation in Women With Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015, 33, 2424–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, K.; Marin, L.; Bedoschi, G.; Pacheco, F.; Sugishita, Y.; Kawahara, T.; Taylan, E.; Acosta, C.; Bang, H. Ovarian transplantation with robotic surgery and a neovascularizing human extracellular matrix scaffold: a case series in comparison to meta-analytic data. Fertil Steril 2022, 117, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, L.; Bedoschi, G.; Kawahara, T.; Oktay, K.H. History, Evolution and Current State of Ovarian Tissue Auto-Transplantation with Cryopreserved Tissue: a Successful Translational Research Journey from 1999 to 2020. Reprod Sci 2020, 27, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, V.; Bedoschi, G.; Rodriguez-Wallberg, K.; Sonmezer, M.; Pacheco, F.S.; Oktem, O.; Taylor, H.; Oktay, K. Utility of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonists for Fertility Preservation: Lack of Biologic Basis and the Need to Prioritize Proven Methods. J Clin Oncol 2019, 37, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, K.; Bedoschi, G. Appraising the Biological Evidence for and Against the Utility of GnRHa for Preservation of Fertility in Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016, 34, 2563–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, K.; Turan, V.; Bedoschi, G. Reply to M. Lambertini et al. J Clin Oncol 2017, 35, 807–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oktay, K.; Taylan, E.; Rodriguez-Wallberg, K.A.; Bedoschi, G.; Turan, V.; Pacheco, F. Goserelin does not preserve ovarian function against chemotherapy-induced damage. Ann Oncol 2018, 29, 512–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggi, R.; Cariboni, A.M.; Marelli, M.M.; Moretti, R.M.; Andre, V.; Marzagalli, M.; Limonta, P. GnRH and GnRH receptors in the pathophysiology of the human female reproductive system. Hum Reprod Update 2016, 22, 358–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roness, H.; Gavish, Z.; Cohen, Y.; Meirow, D. Ovarian follicle burnout: a universal phenomenon? Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 3245–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, L.; Vitagliano, A.; Capobianco, G.; Dessole, F.; Ambrosini, G.; Andrisani, A. Which is the optimal timing for starting chemoprotection with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists after oocyte cryopreservation? Reflections on a critical case of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 2021, 50, 101815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Rahman, O. Impact of timeliness of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy on the outcomes of breast cancer; a pooled analysis of three clinical trials. Breast 2018, 38, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Chen, Z.; Guo, X.; Cheng, H.; Wang, P.; Wang, T.; Wang, L.; Tash, D.; Ren, P.; Zhu, B.; et al. Sudden Death Due to Severe Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome: An Autopsy-Centric Case Report. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2021, 42, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padula, A.M. GnRH analogues--agonists and antagonists. Anim Reprod Sci 2005, 88, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbst, K.L. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2003, 3, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedoschi, G.; Navarro, P.A. Oncofertility programs still suffer from insufficient resources in limited settings. J Assist Reprod Genet 2022, 39, 953–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lainas, G.T.; Kolibianakis, E.M.; Sfontouris, I.A.; Zorzovilis, I.Z.; Petsas, G.K.; Tarlatzi, T.B.; Tarlatzis, B.C.; Lainas, T.G. Outpatient management of severe early OHSS by administration of GnRH antagonist in the luteal phase: an observational cohort study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2012, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lainas, G.T.; Kolibianakis, E.M.; Sfontouris, I.A.; Zorzovilis, I.Z.; Petsas, G.K.; Lainas, T.G.; Tarlatzis, B.C. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor levels following luteal gonadotrophin-releasing hormone antagonist administration in women with severe early ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. BJOG 2014, 121, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).