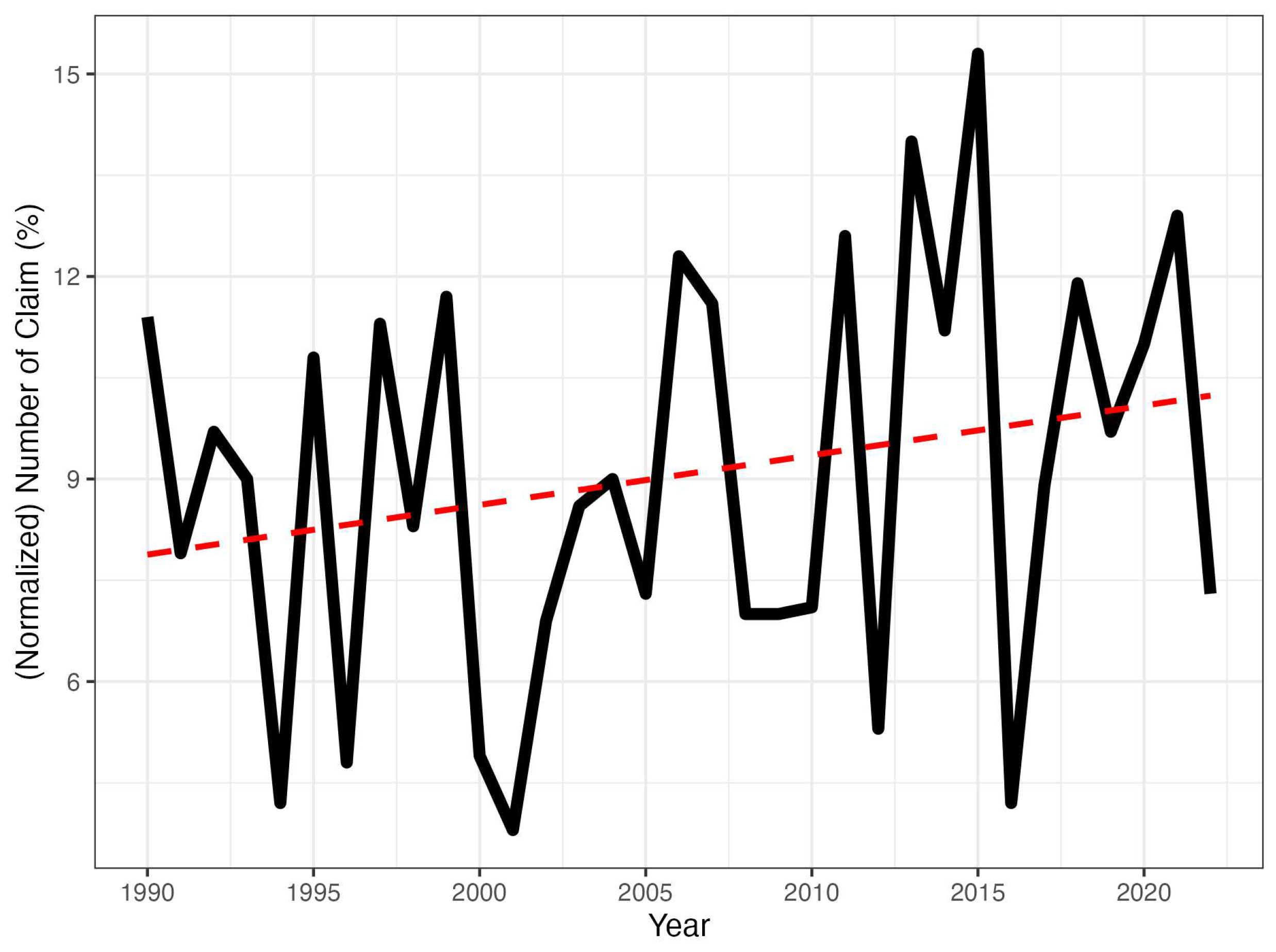

3.1. Monthly Normalized Number of Claims,N

In

Table 3 we present the results for three linear regression models designed to investigate if there is any relationship between climate variables like SACI and its components, and the mean of

N.

In

model 1

we investigate the influence of monthly SACI on the mean of

N, finding that this is significant at a

level. This indicates that it has a somewhat influence on the number of hail claims. However, its

is deficient, indicating that the SACI by itself does not explain well the variations in the mean of

N.

In

model 2

we introduce the components of the SACI to discern their impact on the mean of

N. Notably, the high-temperature days

, and sea level

are significant, suggesting a potential link between these two SACI components and the mean. However, despite their significance, the overall explanatory power of the model, as indicated by the

, remains low. While extreme heat and sea level contribute to the predictive model, there is a need for further variables to enhance the accuracy of the analysis.

In

model 3 we give a try to the formula

that incorporates the months from April to September, encompassing the high-incidence season of hailstorms. Despite the statistical significance observed for precipitation (

) and wind

, with coefficients of opposite signs, the overall explanatory power of the model, as indicated by the R-squared value

= 0.5, remains relatively moderate, much better than in the precedent case though. It is noteworthy that the month variables attain statistical significance at the 1 percent level, apart from April whose one is at the 10 percent level. This confirms the seasonal pattern in the occurrence of hail events.

In summary, while the relationship between the mean of

N and the SACI seems to be quite fragile (model 1, eq.(

7)), we have found some evidence through models 2 (eq. (

8)) and 3 (eq. (

9)) that some of its components like high-temperature days (

), Precipitation (

), Wind (

), sea level (

) explain the variation of the mean of

N until a certain point. We take note that the wind component is significant in model 3 (eq. (

9)) with a negative

though, which seems to indicate an opposite effect into

N from the other significant components. The season variables Apr. to Sep. are also significant, as expected.

Next, we move to the study of the influence of SACI and its components on the quantiles of N.

For this sake, we begin with

model 4:

At the 90th percentile, SACI exhibits a statistically significant positive association with the number of claims ( coefficient = 0.018, p< 0.01). For the 95th percentile, although positive, the association is not significant (coefficient = 0.014, p>0.1); notice also that the confidence interval at 95% lies in both negative and positive halves of the real line. At the 99th percentile, the positive relationship is marginally significant (coefficient = 0.005, p<0.1), but the confidence interval is equally deficient. The 99th and 95th percentiles confidence intervals include both positive and negative values, suggesting a certain degree of uncertainty regarding the precise impact of SACI. The two marginally significant positive coefficients and confidence intervals spanning from slightly negative to positive values indicate that the relationships between SACI and N at those percentiles are not as conclusively positive as observed at the lower 90th percentile, as the inclusion of zero in the intervals suggests the possibility of a null effect or a very modest effect that is not statistically distinguishable from zero.

Also, in

Table 4, we observed the pseudo R-squared decreases as the quantile increases in quantile regression. The decrease in pseudo R-squared at higher quantiles indicates that the model explanatory power diminishes for extreme observations, suggesting the presence of additional factors or complexities that contribute to the variability in the upper tail of the distribution.

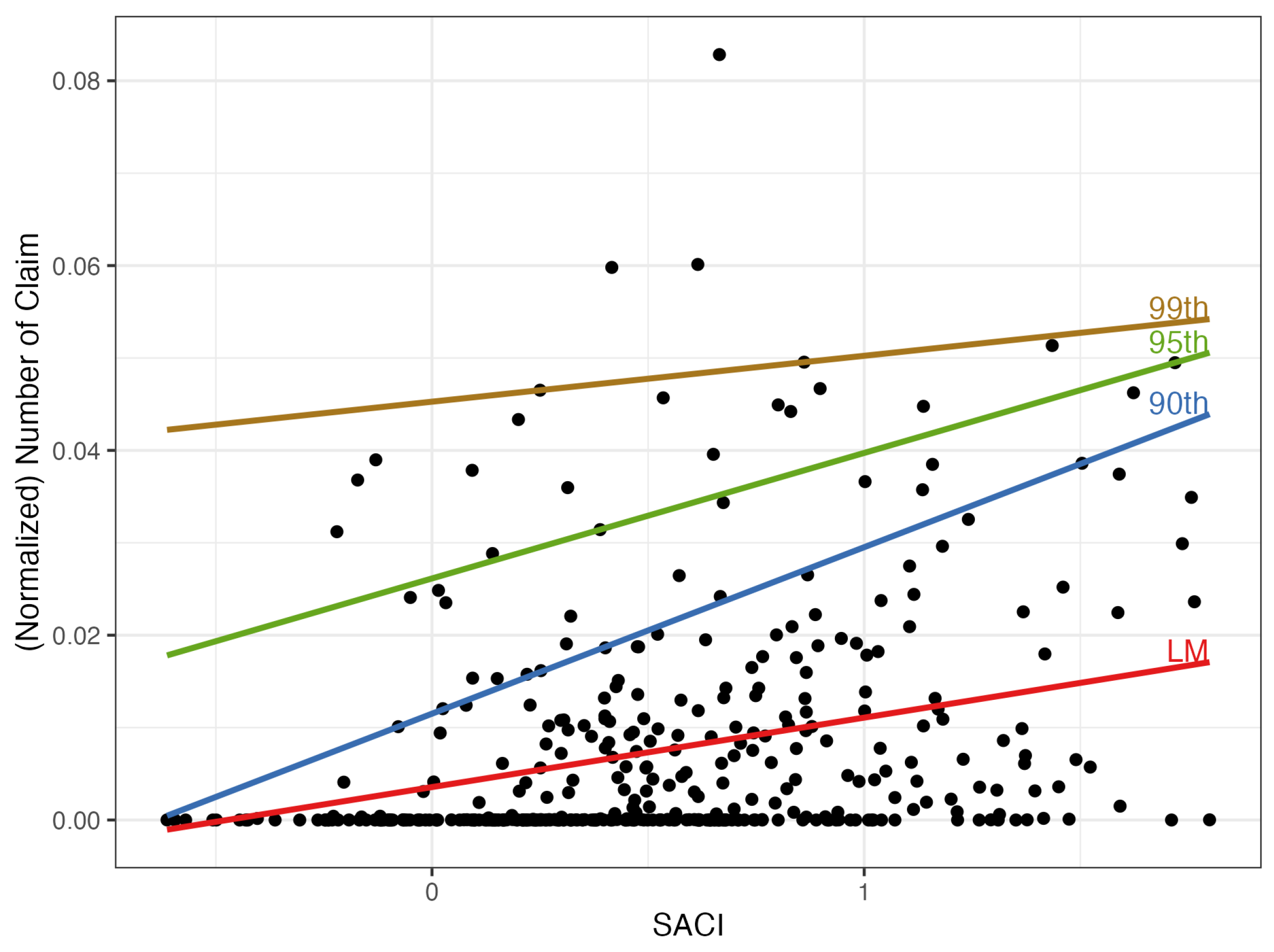

The scatter plot in

Figure 8 illustrates the SACI influence on the quantiles of

N, with all the reserves motivated by the information contained in

Table 4. The quantile lines correspond to model 4 (eq.

10). With due caution, we can see that an increase in SACI causes an increase in all three levels of

. It seems also that the higher the probability level the less steep the quantile line.

In

model 5 we introduce the months relevant to hail risk

while in

model 6 we introduce the SACI components together with the months as independent variables:

Table 5 gives the results for these two quantile regression models. We can check that both SACI and its components except the drought -

- significantly impact the normalized number of claims across different quantiles. For the significant variables, confidence intervals lie at one or the other side of the origin. In the cases of

they are on the positive side showing their increasing influence on

. For

this happens on the negative half though, denouncing that an increase of the wind component results in a decrease of the corresponding quantile of

N (the same happened in the mean of

N, see model 3, eq.(

9)). These results indicate that SACI, as a comprehensive climate index, has a substantial impact on the extremes of the number of claims

N. The months constituting the hailstorm season are all significant, as was expected. As explained in the previous section, pseudo-R-squared values are calculated following [

33]. The values obtained for these six models all exceed 0.5, indicating a not negligible fitting score for all these models.

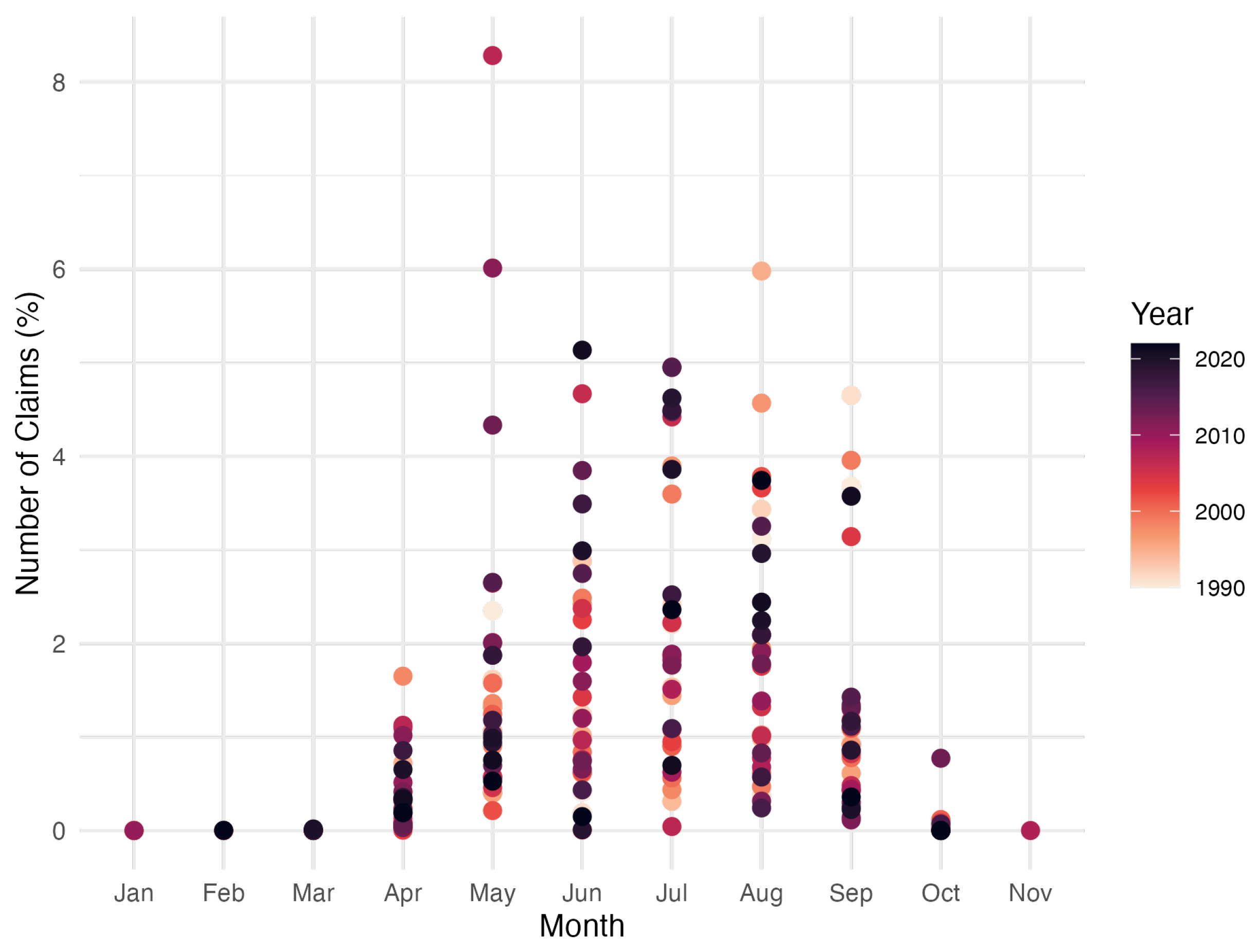

3.2. Monthly Normalized Number of Loss Costs Equal to One, .

Next, we investigate the relationship between as the dependent variable and SACI and its components as independent ones. Remember that a claim with a loss cost equal to 1 implies that the loss equals the value of the insured capital, indicating the full scale of damage for that claim.

In

model 7, we investigate the linear regression with the SACI alone as an independent variable:

while

model 8 includes also the months composing hailstorms season:

Results for both models are available in

Table 5. Results for model 7 (eq. (

13)) indicate that SACI is statistically significant at the 1% level, with a

coefficient of 0.0003. However, the R-squared value is extremely low,

, denoting that the model explanatory power is very weak.

In model 8 (eq. (

14)), we introduce the months as independent variables (April to September). We observe that among the month variables, only May, July, and August are statistically significant. This is a notable difference compared to the case of the number of claims

N, which might indicate that not any month in the hailstorm season is relevant to the loss costs being equal to one, only May, July, and August. Overall, the R-squared value of the model increases to 0.146, indicating that the introduction of the month variable has improved its ability to explain the mean of

.

In summary, we have found through model 8 (eq. (

14)) that the SACI influences to a certain extent the mean of

, and that the effect of an increase in one unit of SACI would result in an extremely slight increase in this mean by a factor of 0.0003. We also found that through hailstorm season, only May, July, and August are significant for the mean

.

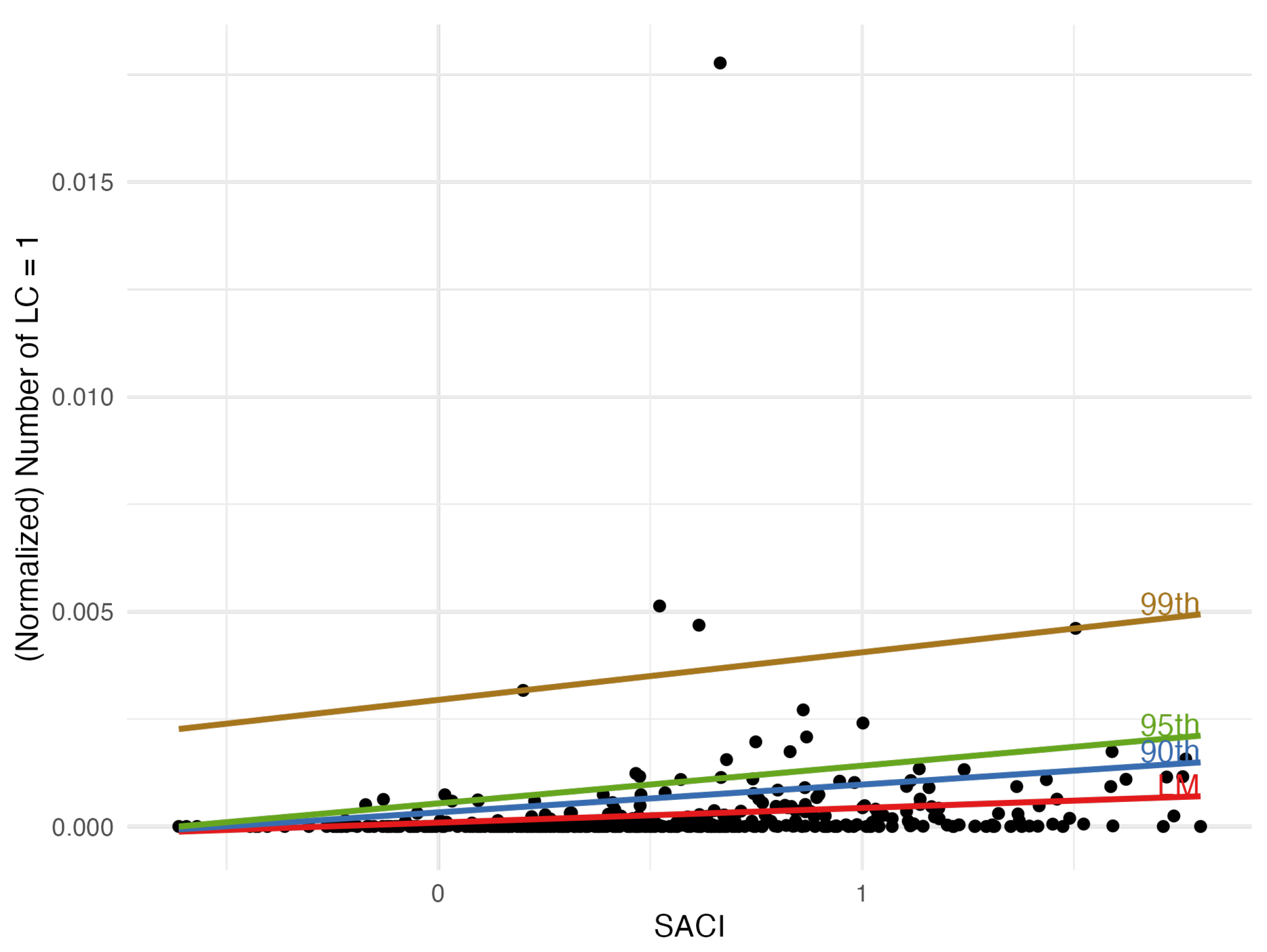

In

Figure 9 we find the increasing line given by model 7 (eq.

13) predicting the mean

by the values of SACI. And we find also the quantile regression lines corresponding to probability levels

. In the three cases, we have got an increasing line. The three lines correspond to the quantile regression defined by

model 9:

In

Table 7, the coefficient for the variable SACI attains statistical significance at 1% level for both the 90th and 95th percentiles. This signifies a discernible positive relationship between the SACI and

at these percentiles. The significant positive association with SACI at the specified percentiles underscores its role in influencing

. However, at the 99th percentile, there is no significance anymore and the confidence interval contains zero. This model is quite weak, as denounced by the very low values of the pseudo-

.

Next, in

model 10 we introduce the months in the quantile regression using

We have finally decomposed the index in its components adding also the months in the quantile regression

model 11, for the same three

-values:

In

Table 8 we summarize the results corresponding to models 10 (eq. (

16)) and 11 (eq. (

17)). There we can see that the SACI variable in model 10 (eq.

16) has a significant impact on the 95th and 99th quantile levels. All months are significant except April in the 90th and 99th quantile.

Looking at model 11 (

17), precipitation

and drought

are not significant at any of the three quantile levels, suggesting a weak association between extreme precipitation and drought with

extremes. On the other hand, we find that high and low temperatures (

) are significant variables in the three quantiles, while wind (

), and sea level (

) are only significant for quantiles

. We notice again that wind coefficients are negative as was the case for the quantile regression model 6 (eq. (

12)) in the quantiles

, and also for the mean of

N in the linear regression model 3 (eq.(

15)) (see

Table 4 and

Table 5). All the months from April to September are significant across the three probability levels and their inclusion has enhanced the models, as shown by the increase in pseudo-

from model 10 to 11 in

Table 7 and

Table 8. In this last case, the pseudo-

coefficients are in all cases above 0.35, and also they increase across higher quantiles, suggesting a heightened ability of predictors to capture variability in the number of LC1 at extreme percentiles.

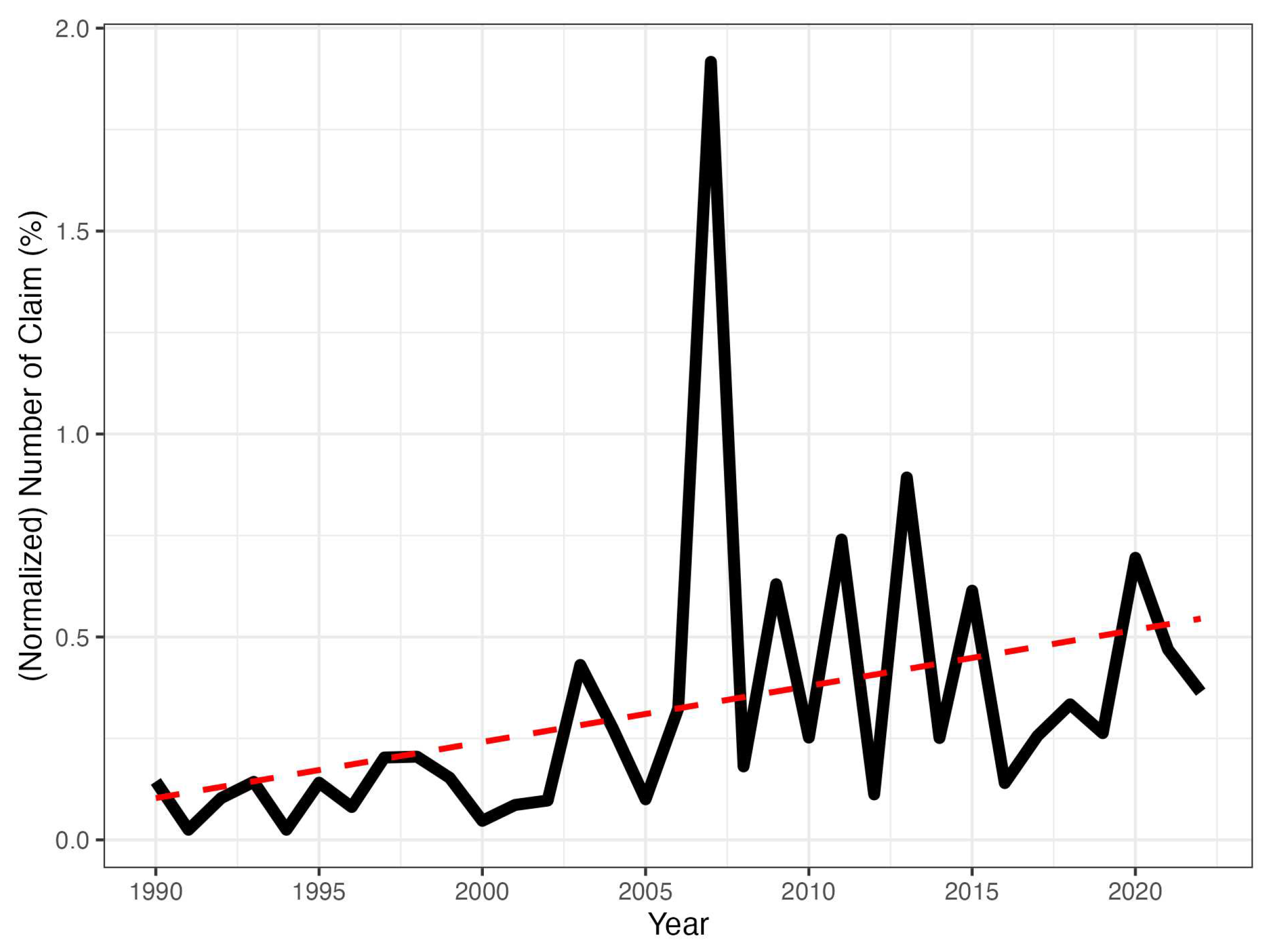

3.3. Monthly Homogenized Losses, L.

In the first stage, we will investigate the climate change effect on L by four linear regression models exploring the impact of the SACI and its components on hailstorm monthly total loss.

Results are shown in

Table 9. In models 12 (eq. (

18)) and 13 (eq. (

19), SACI is significant at the 1% confidence level with a positive coefficient, indicating that the mean of

L increases if SACI increases. The

for model 12 is not negligible (0.159), and we have to stress that in the case of model 13, we get

which is a good enough value. This is probably due to the inclusion of the months in this model. In models 14 (eq. (

20)) and 15(eq. (

21)) we study the significance of SACI components, and see how they show different levels of significance. So in model 14 (without months) hot and cool temperatures, precipitation, and sea level (

) are significant, while drought and wind (

and

) are not. Let us observe that the significance of

indicates a negative correlation with

L. In model 15 (including the months), cool temperatures, wind, and sea level (

) are significant, while the rest is not. Let us outline the fact that again, when wind is significant it is negatively correlated, in this case relative to

L. Regarding the

scores, it is not negligible for model 14, and even in model 15, it gets a remarkably high value of 0.814.

Considering the complexity of the models, model 13 offers a more succinct way of explaining hailstorm mean monthly total loss than model 15. This is because model 13 unifies all the climate change effects in one magnitude, the SACI, making the interpretation and understanding more direct and simple.

Regarding the interpretation of the SACI coefficient in model 13 (), we now know that an increase in c units of SACI results in an increase in the mean of L by . For instance, taking of monthly SACI, we get approximately , that is, an increase in the mean total loss of approximately 9.1%. Let us apply this to calculate the cost of a future Climate change as measured by SACI.

We have calculated by model 13 (eq.(

19)) the predicted

for different SACI values. Among all the months April to September 2022, let us choose the two ones with maximum and minimum SACI values, specifically July 2022 (SACI = 1.764) and May 2022 (SACI = 1.050). The model 13 (eq.(

19)) predictions were approximately 3,327,700€ for July and 2,433,643€ for May. These two cases are going to be used to give upper and lower bounds for the increase of

corresponding to a future hypothetical increase of SACI in 0.1 units. We only have to multiply them by 0.091:

The change in losses from May to July is not simply attributable to the change in SACI values, as

might suggest. Instead, it resulted from a combination of SACI’s effect and specific monthly effect encoded by each one of the month’s coefficients, underscoring the model’s complexity. The percentage change in losses due to the month shift, calculated as

which is approximately 36.74%, demonstrating the significant influence of monthly coefficients on

predictions.

Therefore, this interpretation is a key factor for sustainability management because it provides a concrete way to quantify the impact of an increment in SACI into . In summary, this direct percentage relationship makes SACI an effective tool for assessing future increases in the mean monthly total loss due to a growing climate change scenario.

Finally, we remember that models 13 and 15 (eq. (

19) and (

21)) that include the months, demonstrate stronger explanatory power compared to the other two models, as seen from their R-squared values of about 0.81.

Next, we begin with the quantile regression models with

as the independent variable. It is relevant to outline here the well-known quantile property consisting of (see[

32] p.48):

for any monotone transformation

. In our case,

.

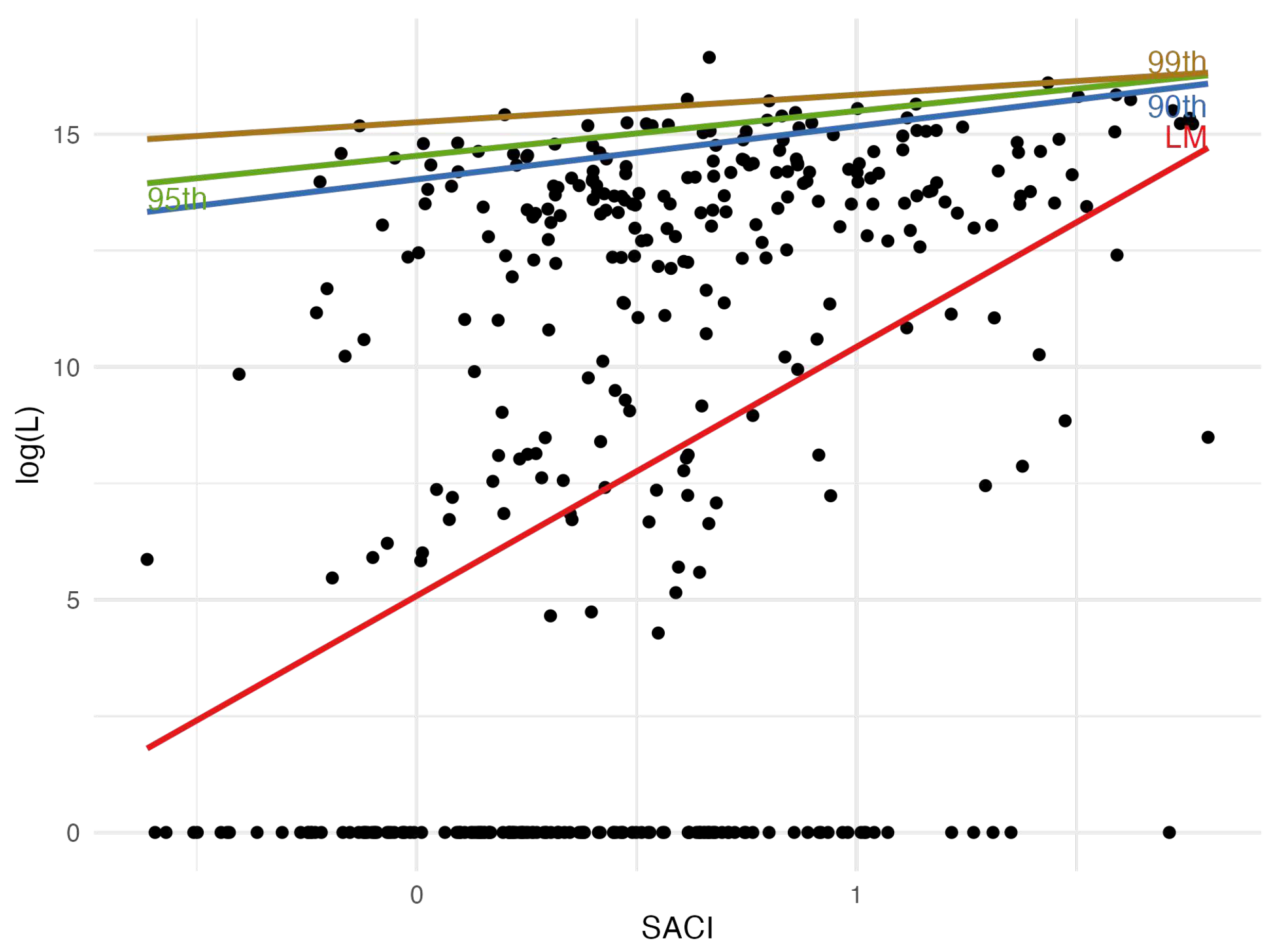

Figure 10 illustrates the relationship between monthly

and SACI. It contains four fitted lines. The upward red line representing the linear regression indicates that as SACI increases,

tends to rise also, supporting the conclusion that there is a positive correlation between SACI and hailstorm losses. In addition, three colored lines correspond to quantile regressions for the 90th, 95th, and 99th percentiles. These lines demonstrate the variation in higher losses associated with SACI values, illustrating the behavior of the tail of the monthly total loss distribution concerning SACI variations.

Table 10 presents the results of quantile regression for model 16 (eq.

24), with the dependent variable being

and the independent one being the monthly SACI.

For the 90th and 95th quantiles, the SACI coefficients are significant at the 1% level. On practical grounds, this implies that a one percentage point of 0.01 increase in SACI is associated with a 1.141% increase in hail L at the 90th quantile. A similar calculation could be done in the 95th quantile. Unfortunately, this is not extensible to the 99th quantile because the coefficient is no longer credible (see its confidence interval and p-value).

Regarding pseudo R-squared, the values are very low, indicating that the model explains a small proportion of the variability in hail loss. These values suggest that the SACI independent variable contributes modestly to explaining the variability in hail loss at these quantiles.

In

model 17 we include the months April to September as independent binary variables:

Finally in

model 18 we decompose the monthly SACI in its components still including the months:

Table 11 presents the results of an analysis using quantile regression to investigate the relationship between hailstorm total losses even SACI or its components. The analysis is conducted separately for the 90th, 95th, and 99th percentiles, taking into account monthly variables from April to September.

Concerning model 17 (eq. (

25)), SACI exhibits statistical significance at the three percentiles, even though the confidence interval in the first case contains negative and positive values a fact that devaluates the quality of this estimate. This indicates (with due caution for the 90th case) a significant positive correlation between SACI and hailstorm losses across these percentiles. SACI’s influence becomes more pronounced with increasing percentiles, highlighting its heightened importance in extreme loss events. The observed trend in SACI coefficient values, rising from 0.541 to 0.619, emphasizes its non-uniform impact across quantiles of the monthly total loss distribution. This underscores SACI’s important role in assessing the severity and potential risk of the most damaging hailstorm events represented in the upper quantiles of the distribution. Note that all the months are significant.

In model 18 (eq.(

26)),

(days of extremely hot temperature) is statistically significant at the 95th and 99th percentiles, indicating a positive correlation with losses at higher levels.

(days of extremely cold temperature) is only significant at the 95th percentile.

(days of heavy rainfall) is significant at the 95th and 99th percentiles. Conversely,

(wind speed) has a negative and statistically significant coefficient across all three percentiles, suggesting that higher wind speeds are associated with loss decrease. Remember that a similar behavior was observed for models related to the variables

N and

.

The variable representing sea level () is significant at the 90th and 95th quantiles but not at the 99th one. On the other hand, drought days () are only significant at the 99th quantile. Note that all the months are significant at all the percentiles.

Let us consider model 17 in the case

(eq.

25). Let us also consider again the maximum and minimum SACI monthly values for 2022, which are 1.764 (July) and 1.050 (May). We aim to build two bounds (relatives to the year 2022) for the

L- 99th quantile variation corresponding to a SACI variation of 0.1, as was done for its mean in (

22). Model 17 predictions for the

L-99th quantiles corresponding to those SACI values are respectively:

Then the two 2022-bounds for

L-99th quantile variation corresponding to a 0.1 increase in SACI are:

Observe that, when increasing a SACI by 0.1, the adjustment in the 99th quantile of

L can be computed by simply multiplying the loss by

, which is approximately 1.0639.

Again like in (

22), this interpretation is a key factor for sustainability management because it potentially provides a concrete way to quantify the impact of an increment in SACI into any

-quantile of the monthly total loss

L. This direct percentage relationship makes SACI an effective tool for assessing future increases in any quantile of

L caused by an increasing climate change scenario.