Submitted:

29 December 2023

Posted:

30 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

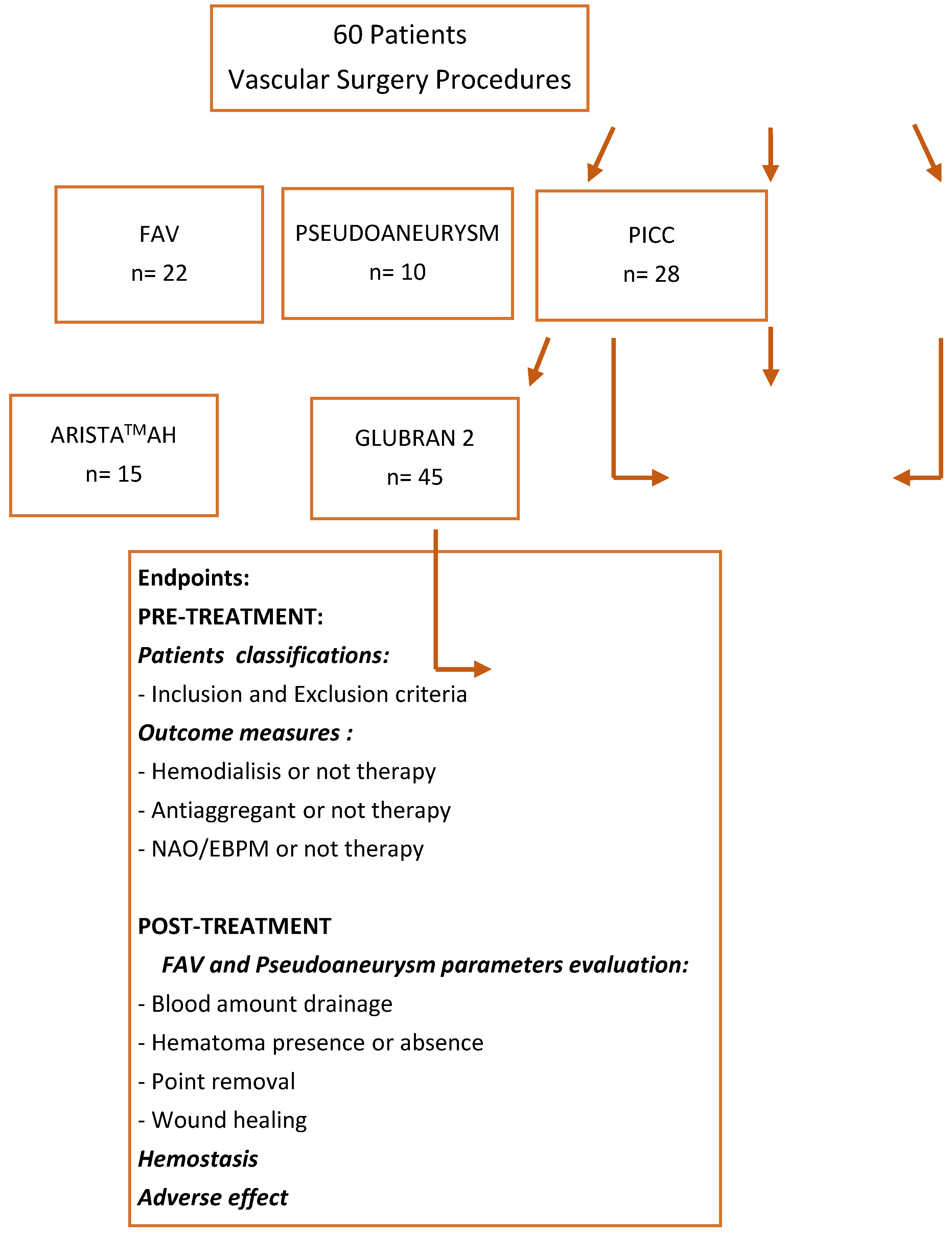

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

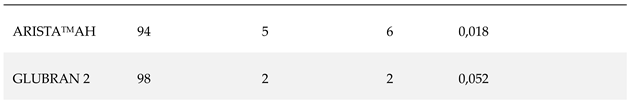

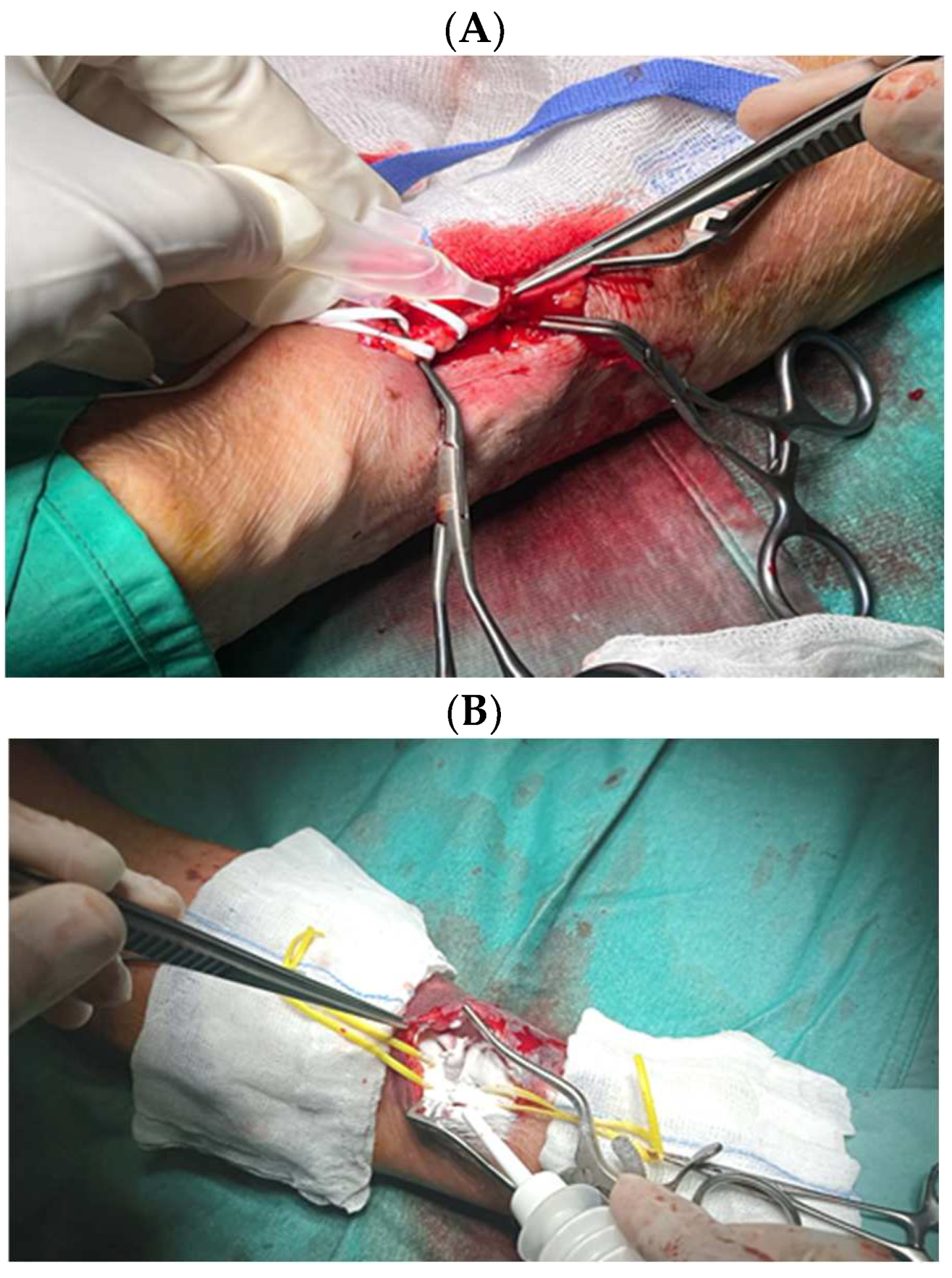

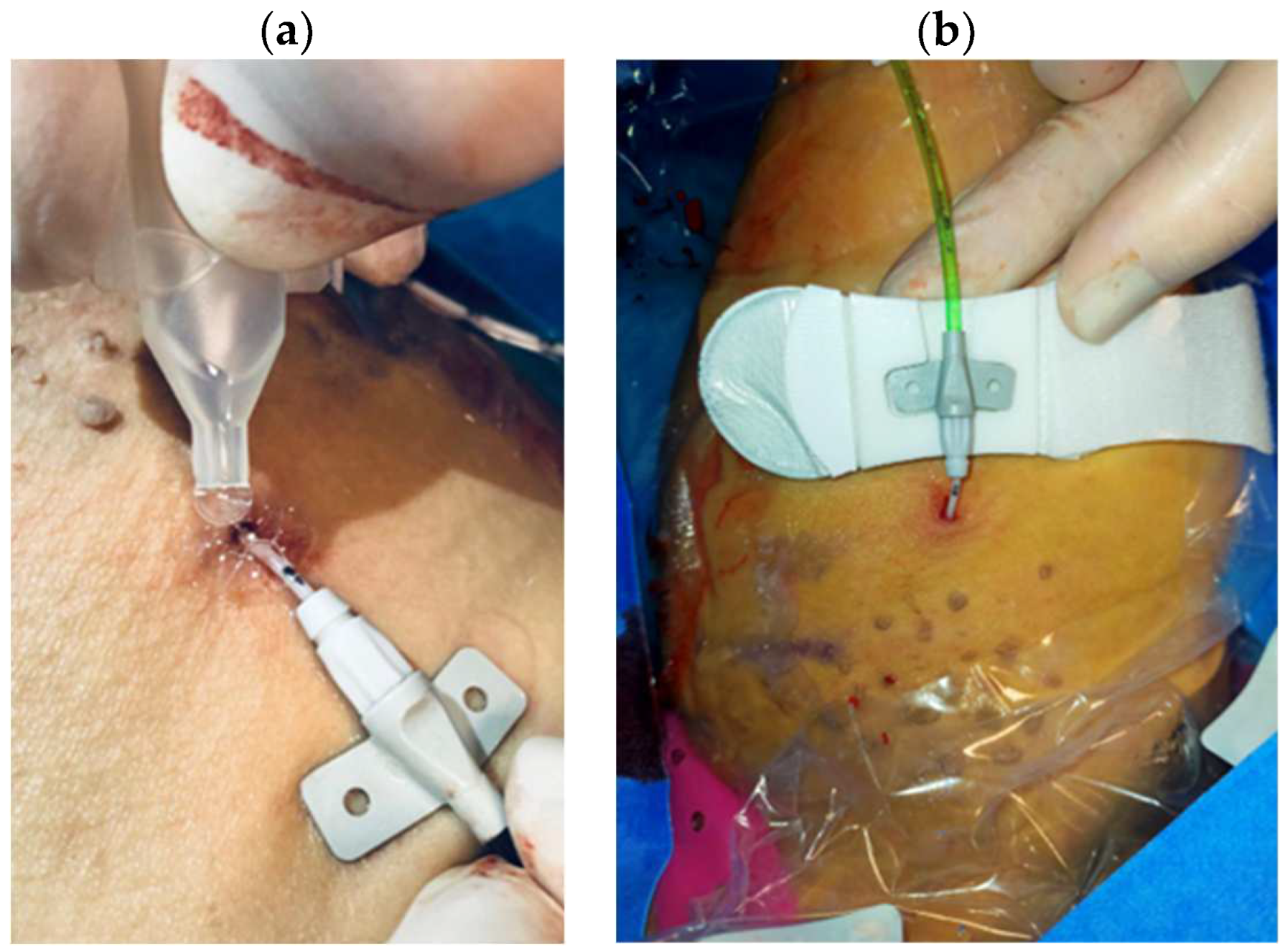

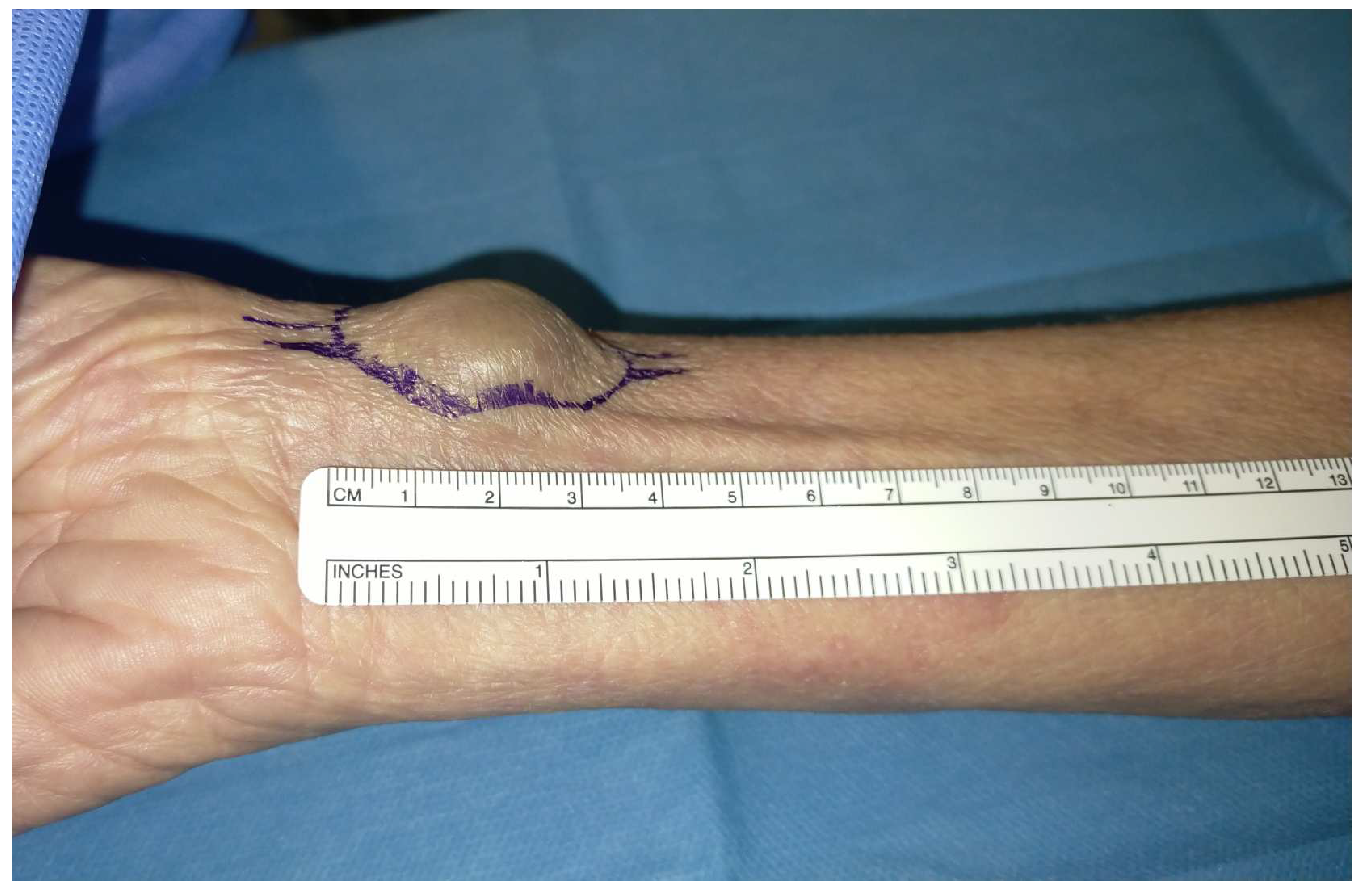

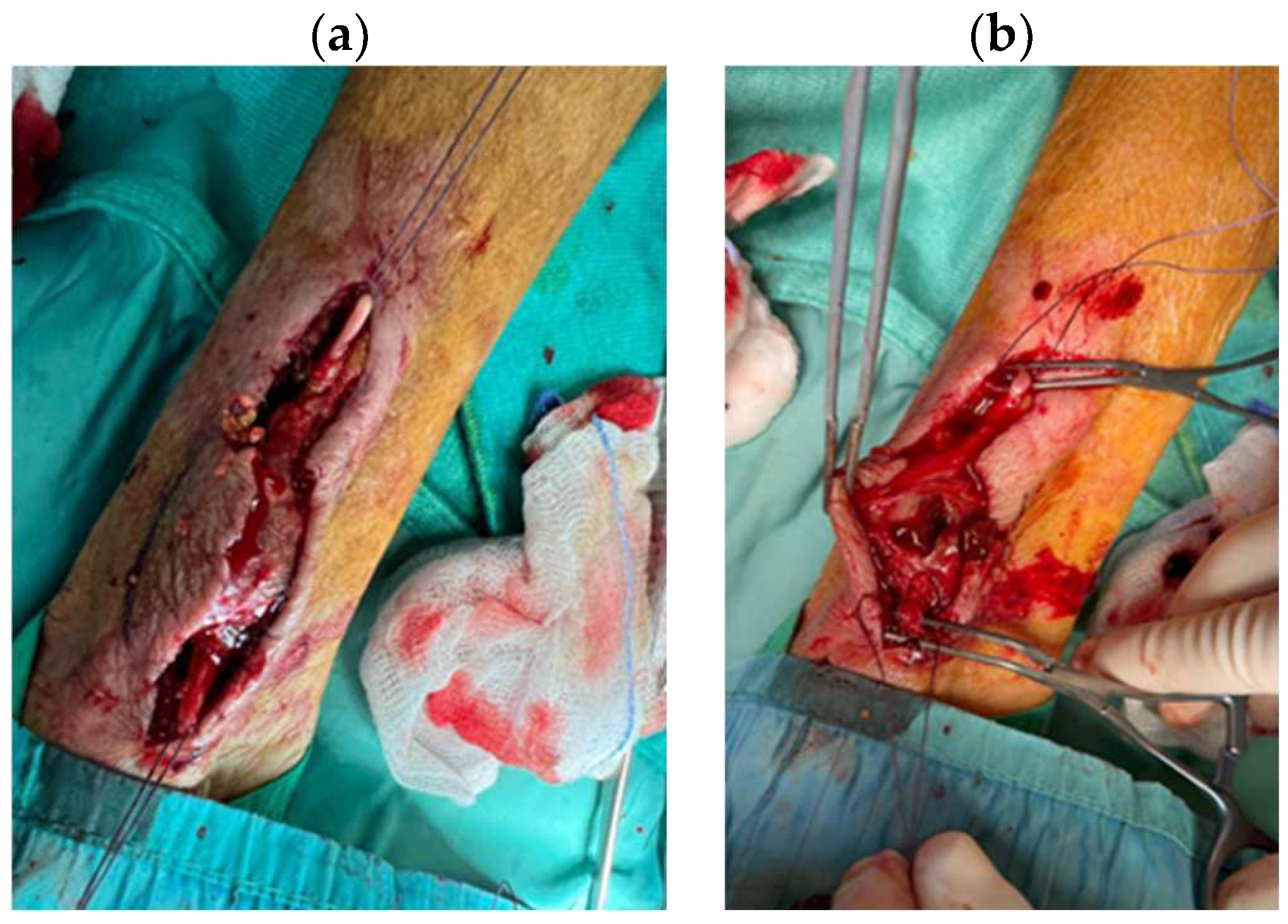

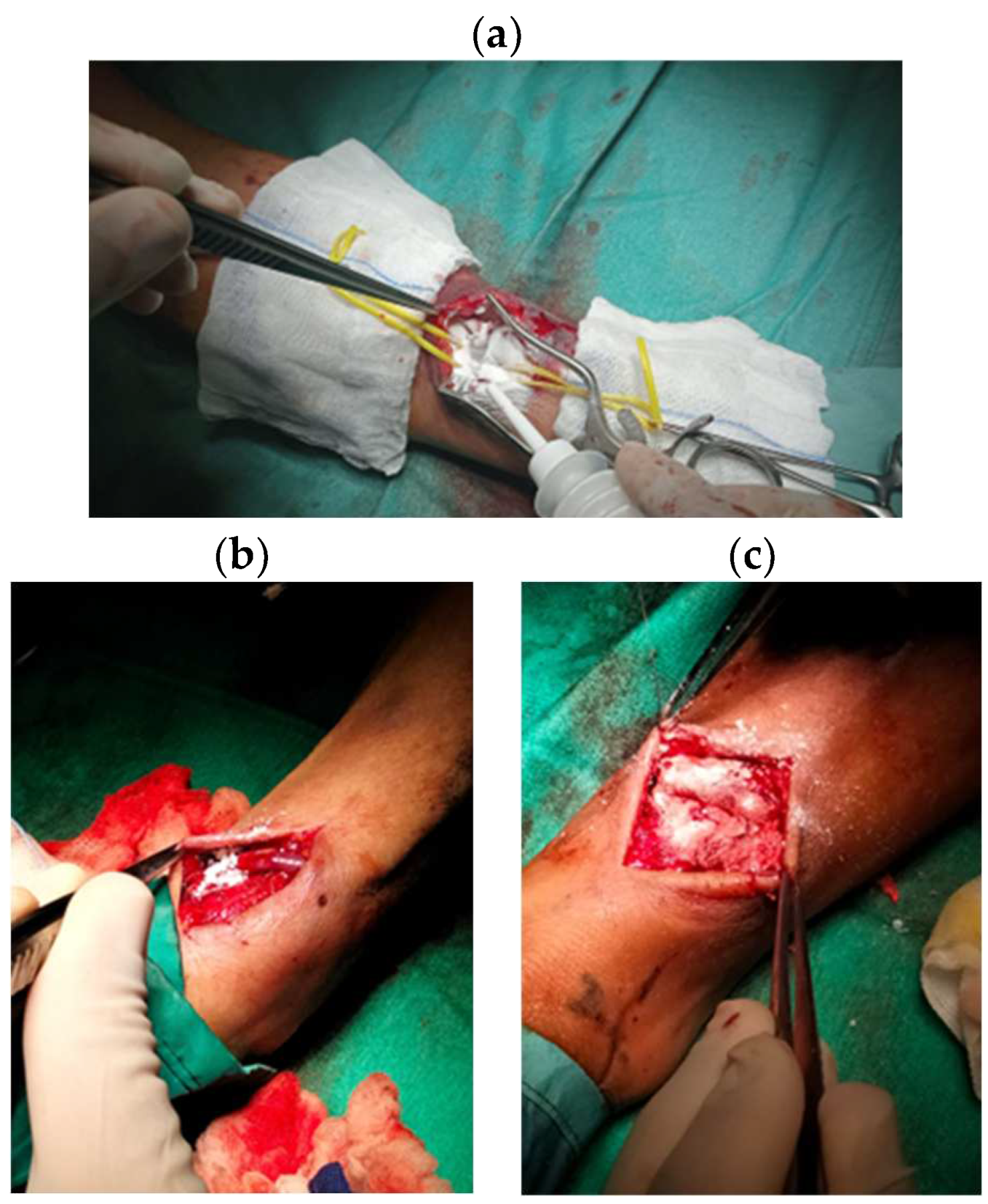

2.2. Data collections and procedure

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Hemostasis Evaluation

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1 Study population

3.2 Procedure data

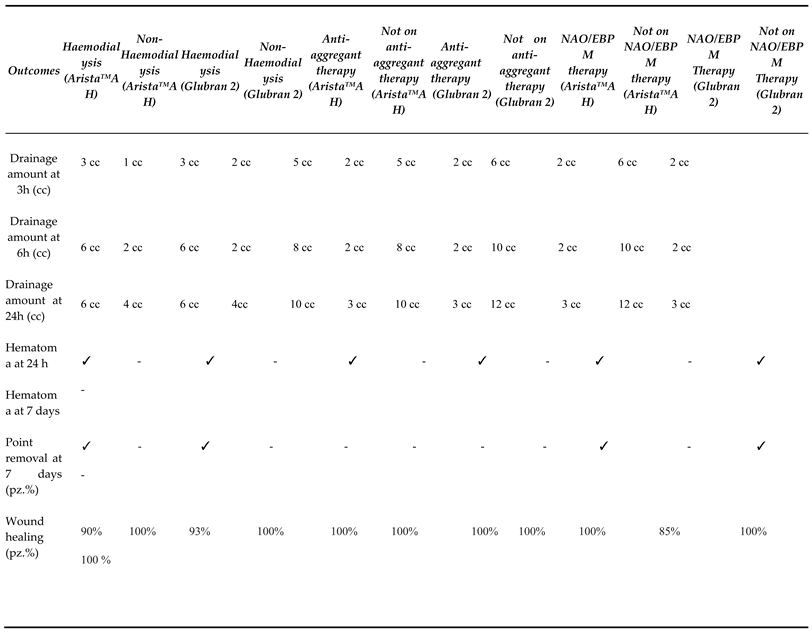

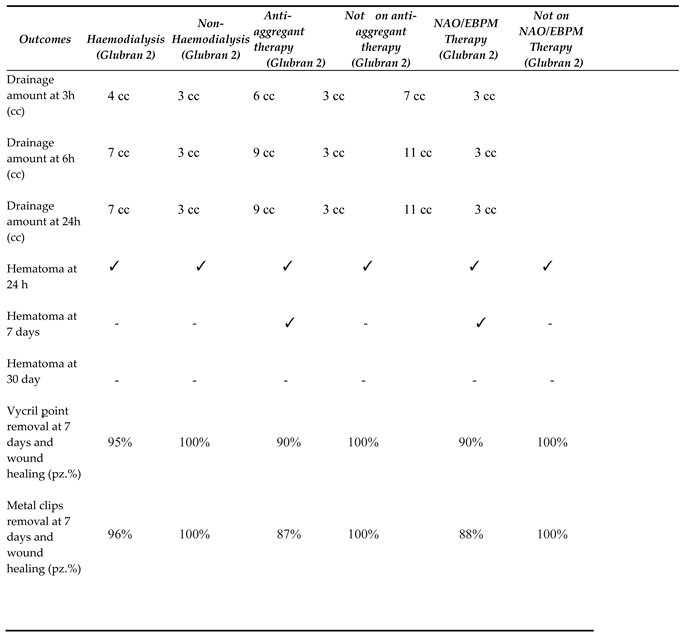

3.3 Outcomes and follow-up

3.4 Hemostasis Evaluation

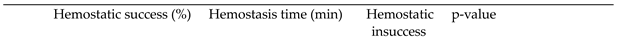

|

3.5 Statistical analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bao Z., Gao M., Sun Y., Nian R., Xian M. The recent progress of tissue adhesives in design strategies, adhesive mechanism and applications. Materials Science & Engineering C, (2020), 111 110796.

- Bal-Ozturk A., Cecen B., Avci-Adali M., Topkaya S.N., Alarcin E., Yasayan G., et al. Tissue adhesives: from research to clinical translation. Nano Today 2021;36:101049. [CrossRef]

- Trombino, S. , Sole R., Curcio F., Cassano R. Polymeric Based Hydrogel Membranes for Biomedical Applications. Membranes 2023, 13, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombino, S. , Curcio F., Cassano R., Curcio M., Cirillo G., Iemma F. Polymeric Biomaterials for the Treatment of Cardiac Post-Infarction Injuries Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1038. [CrossRef]

- Cassano R., Curcio F., Sole R., Trombino S.. Hydrogel based on hyaluronic acid. Polysaccharide Hydrogels for Drug Delivery and Regenerative Medicine. Chapter 3, (2023), Pages 35-46.

- Serini S., Trombino S., Curcio F., Sole R., Cassano R. * and Calviello G. (Hyaluronic Acid-Mediated Phenolic Compound Nano-Delivery for Cancer Targeting. Pharmaceutics, (2023). 15.

- Cassano R., Perri P., Esposito A., Intrieri F., Sole R., Curcio F., Trombino S. Expanded Polytetrafluoroethylene Membranes for Vascular Stent Coating: Manufacturing, Biomedical and Surgical Applications, Innovations and Case Reports. Membranes (2023)13 (2), 240. [CrossRef]

- Sungmin Nam and David Mooney. Polymeric Tissue Adhesives. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 11336−11384.

- Dey A., Bhattacharya P.,Neogi S. Bioadhesives in Biomedical Applications: A Critical Review. In: Progress in Adhesion and Adhesives, Author: K.L. Mittal, Scrivener Publishing LLC ed. 2021, Volume 6, (131–154).

- Athavale A., Thao M., Sassaki V.S., Lewis M., Chandra V., Fukaya E. Cyanoacrylate glue reactions: A systematic review, cases, and proposed mechanisms. Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders, (2023)11, 4.

- Allotey J.K., King A.H., MS, Kumins N.H, Wong V.L.,. Harth K.C., Cho J.S., Kashyap V.S. Systematic review of hemostatic agents used in vascular surgery, Journal of Vascular 2021 73,6.

- https://www.gemitaly.it/prodotti/glubran-2/.

- Dhandapani V. Saseedharan P. Groleau D. Vermette P. Overview of approval procedures for bioadhesives in the United States of America and Canada., J Biomed Mater Res. 2022;110:950–966.

- Guillen, K.; Comby, P.-O.; Chevallier, O.; Salsac, A.-V.; Loffroy, R. In Vivo Experimental Endovascular Uses of Cyanoacrylate in Non-Modified Arteries: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1282. [CrossRef]

- Zheng K., Gu Q. , Zhou D. , Zhou M. , Lei Zhang L. Recent progress in surgical adhesives for biomedical applications. Smart Materials in Medicine. 2022, 3, 41-65.

- Malik A., Ur Rehman F., Ullah Shah K., Naz S.S., Sara Qaisar S. Hemostatic strategies for uncontrolled bleeding: A comprehensive update.J Biomed Mater Res. 2021;109:1465–1477.

- CombyP., Guillen K., Chevallier O., Lenfant M., Pellegrinelli J. ,Falvo N., Midulla M., Loffroy R. Endovascular Use of Cyanoacrylate-Lipiodol Mixture for Peripheral Embolization: Properties, Techniques, Pitfalls, and Applications,J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10(19), 4320. [CrossRef]

- Asada Y., Yamashita A., Sato Y., Hatakeyama K. Pathophysiology of atherothrombosis: Mechanisms of thrombus formation on disrupted atherosclerotic plaques. Pathology International 2020, 70. [CrossRef]

- Brass L.F. , Tomaiuolo M., Welsh J.,Poventud-Fuentes I. , Zhu L. , L. Diamond S.L., Stalker T.J. Hemostatic Thrombus Formation in Flowing Blood. Platelets 2019, 371-391. [CrossRef]

- Krüger-Genge A., Blocki A., Franke R.P., Jung F. Vascular Endothelial Cell Biology: An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20(18), 4411. [CrossRef]

- Kang S., Kishimoto T. Interplay between interleukin-6 signaling and the vascular endothelium in cytokine storms. Experimental & Molecular Medicine (2021) 53:1116–1123.

- LIT-0057 Rev E Arista®AH Absorbable Hemostatic Particles Microporous Polysaccharide Hemosphere (MPH) Technology. Medafor, Inc.; 2.

- Biranje S.S., Sun J., Shi Y.,. Yu S., Jiao H., Zhang M., Wang Q., Wang J. Polysaccharide-based hemostats: recent developments, challenges, and future perspectives. Cellulose 202128(14):1-39.

- Miller K.J., Cao W., Ibrahim M.M., Levinson H. The effect of microporous polysaccharide hemospheres on wound healing and.

- scarring in wild-type and Db/Db mice. J Adv Skin Wound Care. 2017;30:170–180. [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan B., Payanam U., Laurent A., Wassef M., Jayakrishna A. Efficacy evaluation of an in situ forming tissue adhesive hydrogel as sealant for lung and vascular injury. Biomedical Materials, 2021, 16, 4. [CrossRef]

- Capella-Monsonı´s H., Shridhar A., Chirravuri B., Figucia M., Learn G., Greenawalt K., Badylak S.F. A Comparative Study of the Resorption and Immune Response for Two Starch-Based Hemostat Powders. journal of surgical research. 2023 (282) 210 e224.

- Hadi, M.; Walker, C.; Desborough, M.; Basile, A.; Tsetis, D.; Hunt, B.; Müller-Hüllsbeck, S.; Rand, T.; van Delden, O.; Uberoi, R. CIRSE Standards of Practice on Peri-Operative Anticoagulation Management During Interventional Radiology Procedures. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2021, 44, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad R., Israrahmed A., . Yadav R.R., Singh S., Behra M.R., Khuswaha R.S., Narayan PrasadN.,Lal H. Endovascular Embolization in Problematic Hemodialysis Arteriovenous Fistulas: A Nonsurgical Technique Indian.J Nephrol. 2021 31(6): 516–523.

- Bertagna G., Adami D., Del Corso S. Percutaneous glue embolization of arteriovenous fistula of in situ saphenous vein bypass graft: Case report and literature review. Vascular 2022, 30, 4, 759 – 763. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Sheng; Lingle, Bethany S.; Phelps, Shannon A Revolutionary, Proven Solution to Vascular Access Concerns: A Review of the Advantageous Properties and Benefits of Catheter Securement Cyanoacrylate Adhesives.Journal of Infusion Nursing2022, 45, 3, 154-164(11). [CrossRef]

- Bergua-Lorente A., J Farrero-Mena J., Escolà-Nogués A., Llauradó-Mateu M., Serret-Nuevo C., Bellon F. Effectiveness of cyanoacrylate glue in the fixation of midline catheters and peripherally inserted central catheters in hospitalized adult patients: Randomised clinical trial. SAGE Open Medicine. 2023,11.

- Del Corso A.,Vergaro G. Percutaneous Treatment of Iatrogenic Pseudoaneurysms by Cyanoacrylate-Based Wall-Gluing, Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol (2013) 36:669–675. [CrossRef]

- HakanKar. Treatment of iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms. Turkish Journal of Vascular Surgery 2019;28(3):174-179.

- Ferrante G. , Rao S.V., Jüni P. , Da Costa B.R. , Reimers B. , Condorelli G. , Anzuini A. , S Jolly S.S. , Bertrand O.F., Krucoff M.W. , Windecker S. , Valgimigli M. Radial Versus Femoral Access for Coronary Interventions Across the Entire Spectrum of Patients With Coronary Artery Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016, 25;9(14):1419-34.

| Variables |

Picc Patients (n=28) |

FAV Patients (n=22) |

PseudoaneuriysmPatients (n=10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ages (years) Sex (%M/%F) |

68 70 (F)/30 (M) |

71 68 (F)/ 32 (M) |

77 20 (F)/ 80 (M) |

| INR* | 0.92 | 1.18 | 1.06 |

| aPTT** (s) | 27 | 35 | 32 |

| Platelet count (x106/ml) | 260 | 340 | 290 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL)) | 14 | 8 | 13 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.9 | 4.9 | 1.3 |

| Anticoagulant therapy (%) | 7 | 25 | 20 |

| Antiplatelet therapy | (%) 18 | 65 | 50 |

| Haemodialysis therapy (%) | 0 | 50 | 20 |

|

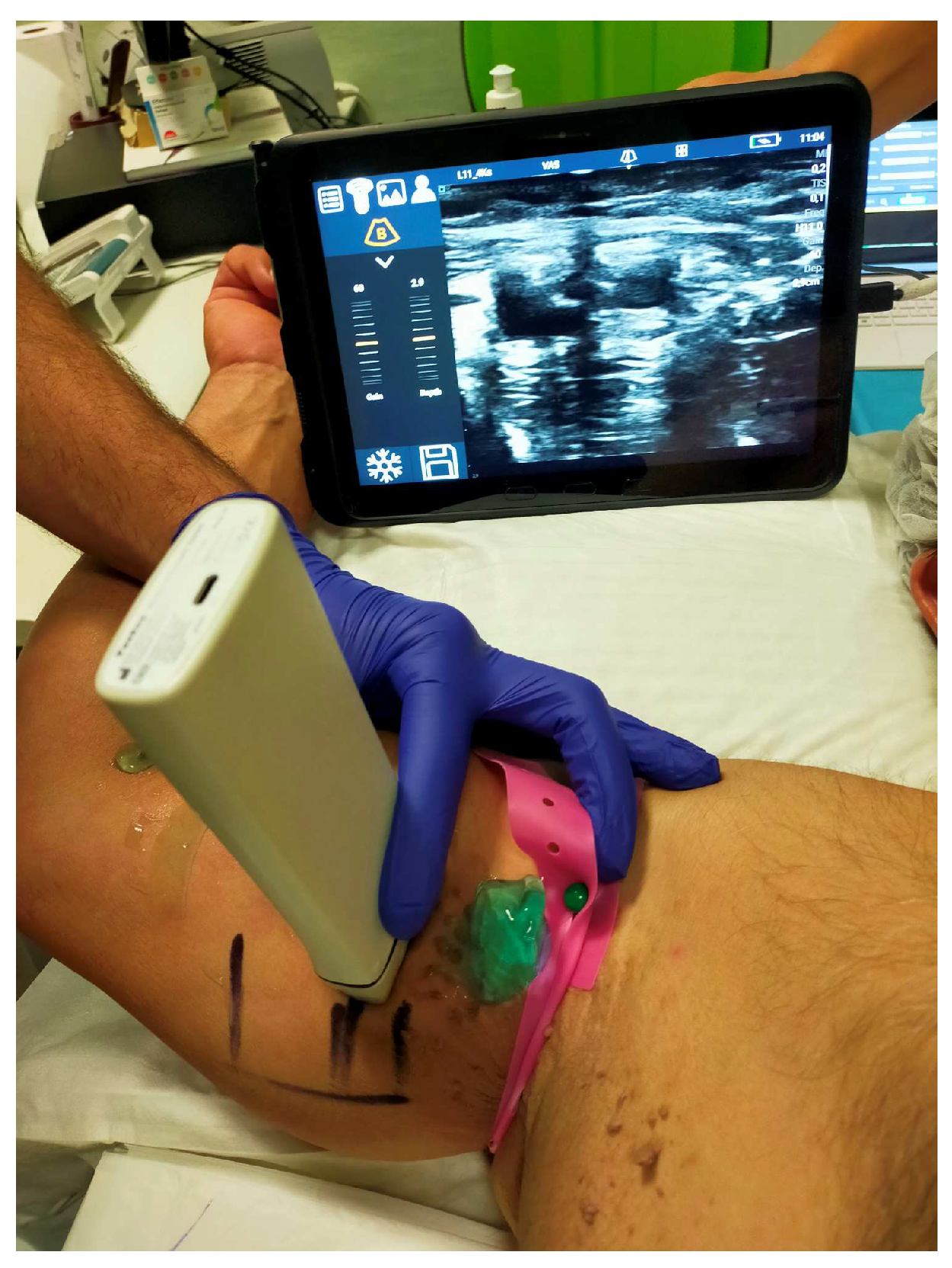

|

| Echocolordoppler control at 1 day | Echocolordoppler control at 3 day | Hematoma presence at 24 h | Hematoma presence at 7 day | Hematoma presence at 30 day | Wound healing Metal clips | Wound healing Vycryl | Collateral effect | Still alive | p-value | |

| Patients with Picc (n=28) | 0 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 2,77x10-7 | |

| Patients with pseudoaneurysm (n=10) | 0 0 | 10(100%) | 6(55%) | 0 | 8(88%) | 9(90%) | 0 | 10(100%) | 9,6x10-5 | |

| Patients with FAV (n=22) | 0 0 | 11(50%) | 7(10%) | 0 | 0 | 22(100%) | 0 | 22(100%) | 2,057x10-3 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).