Submitted:

28 December 2023

Posted:

30 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

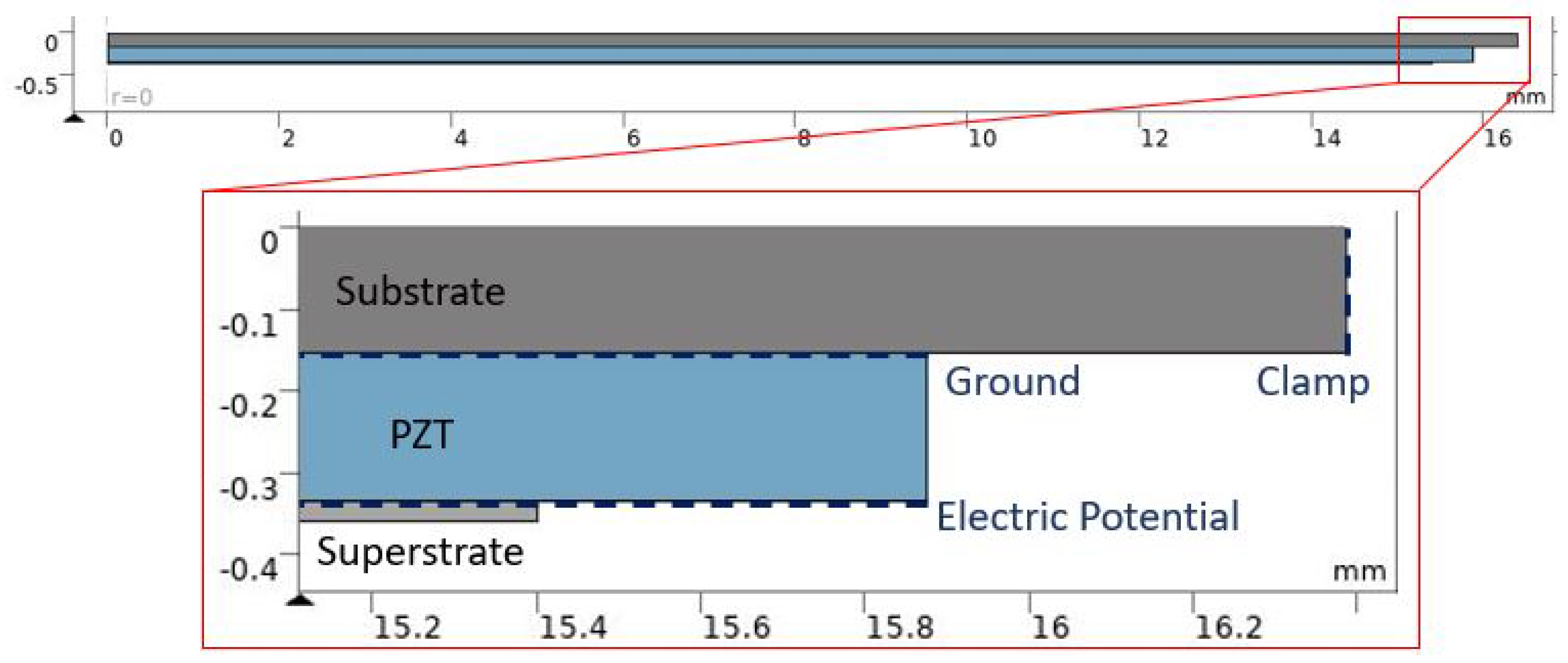

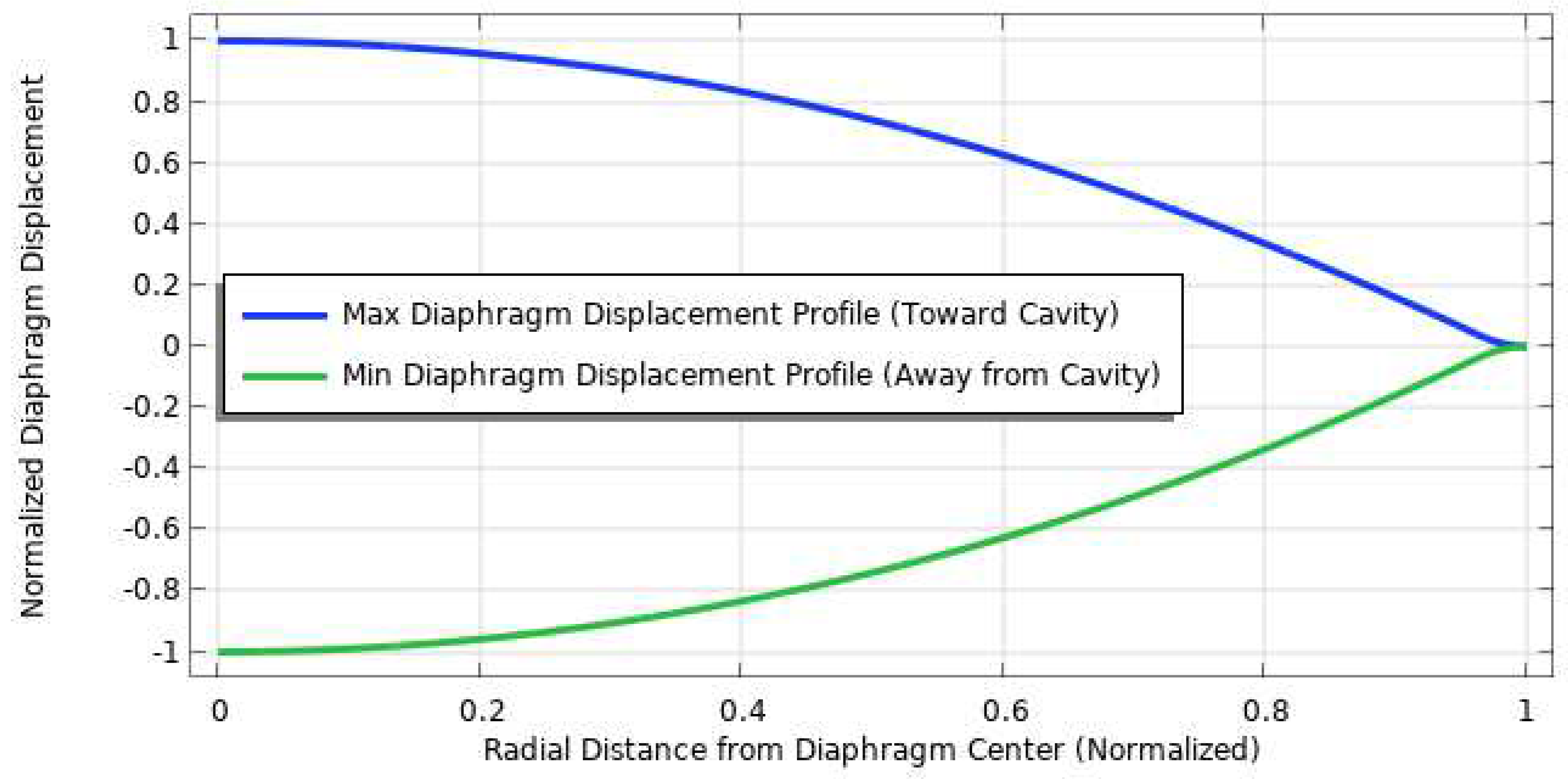

2.1. Diaphragm and Electrostatics

2.2. Pressure Acoustics

2.3. Thermoviscous Acoustics

2.4. Implementation in the Model

2.5. Fluids

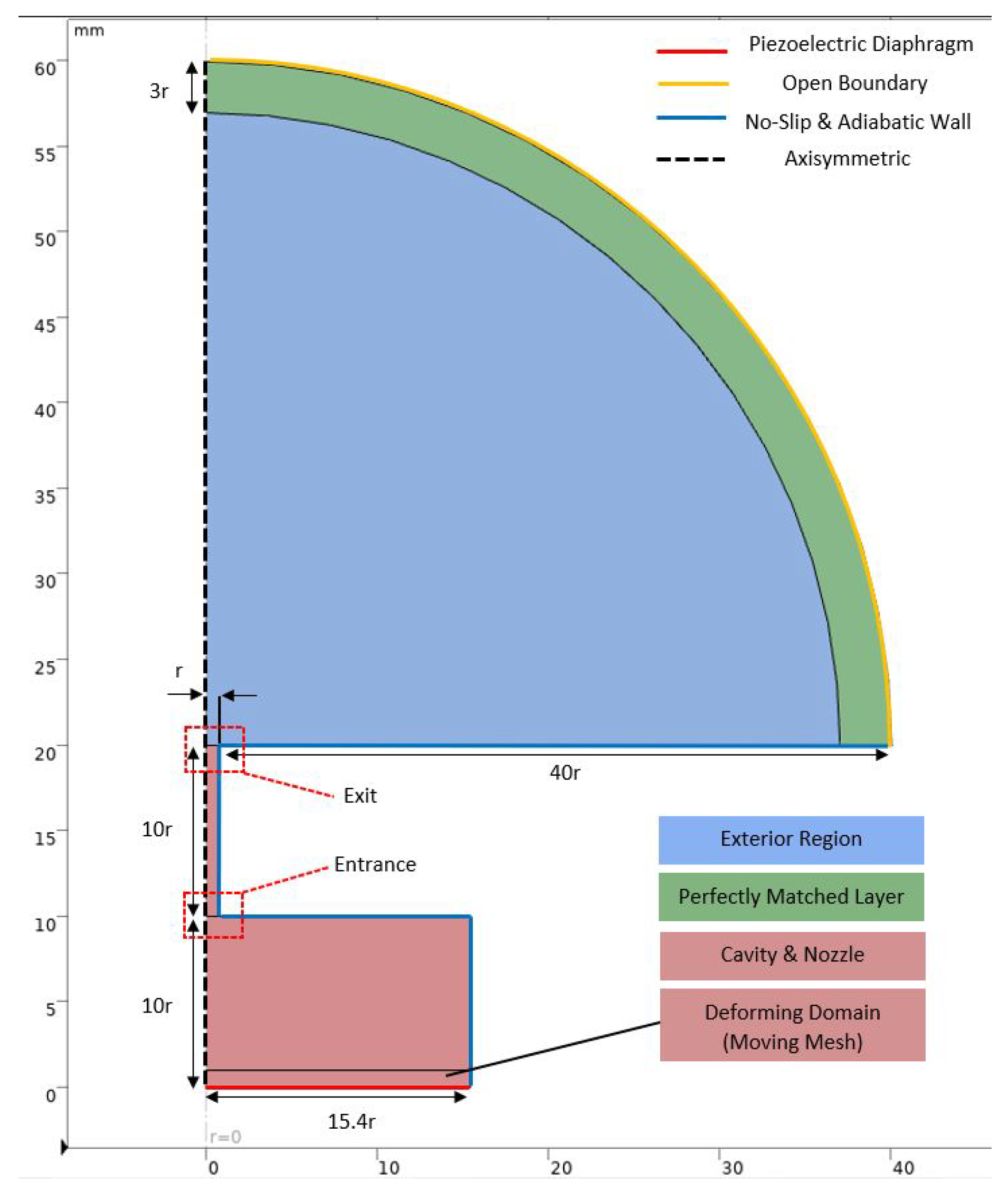

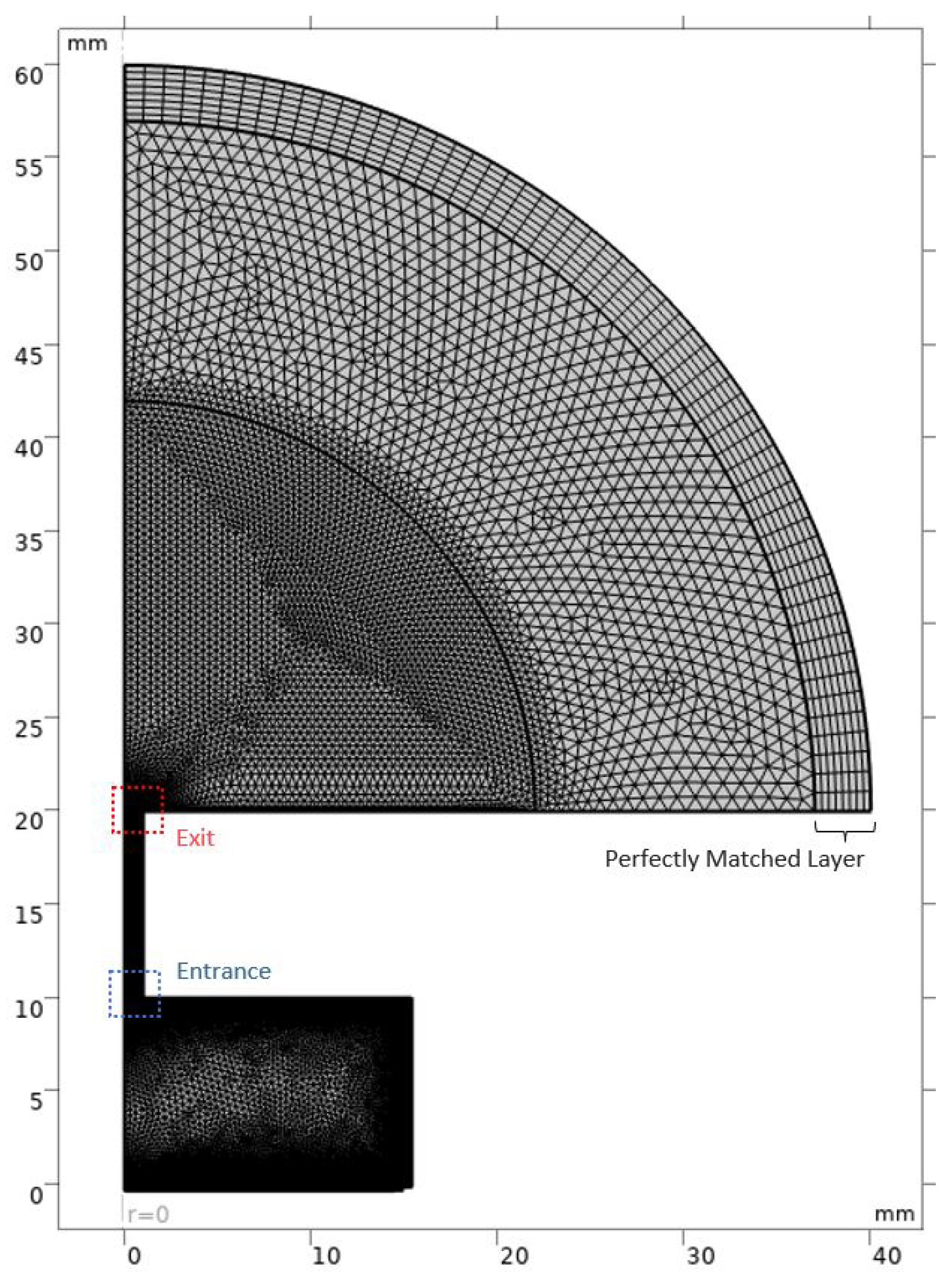

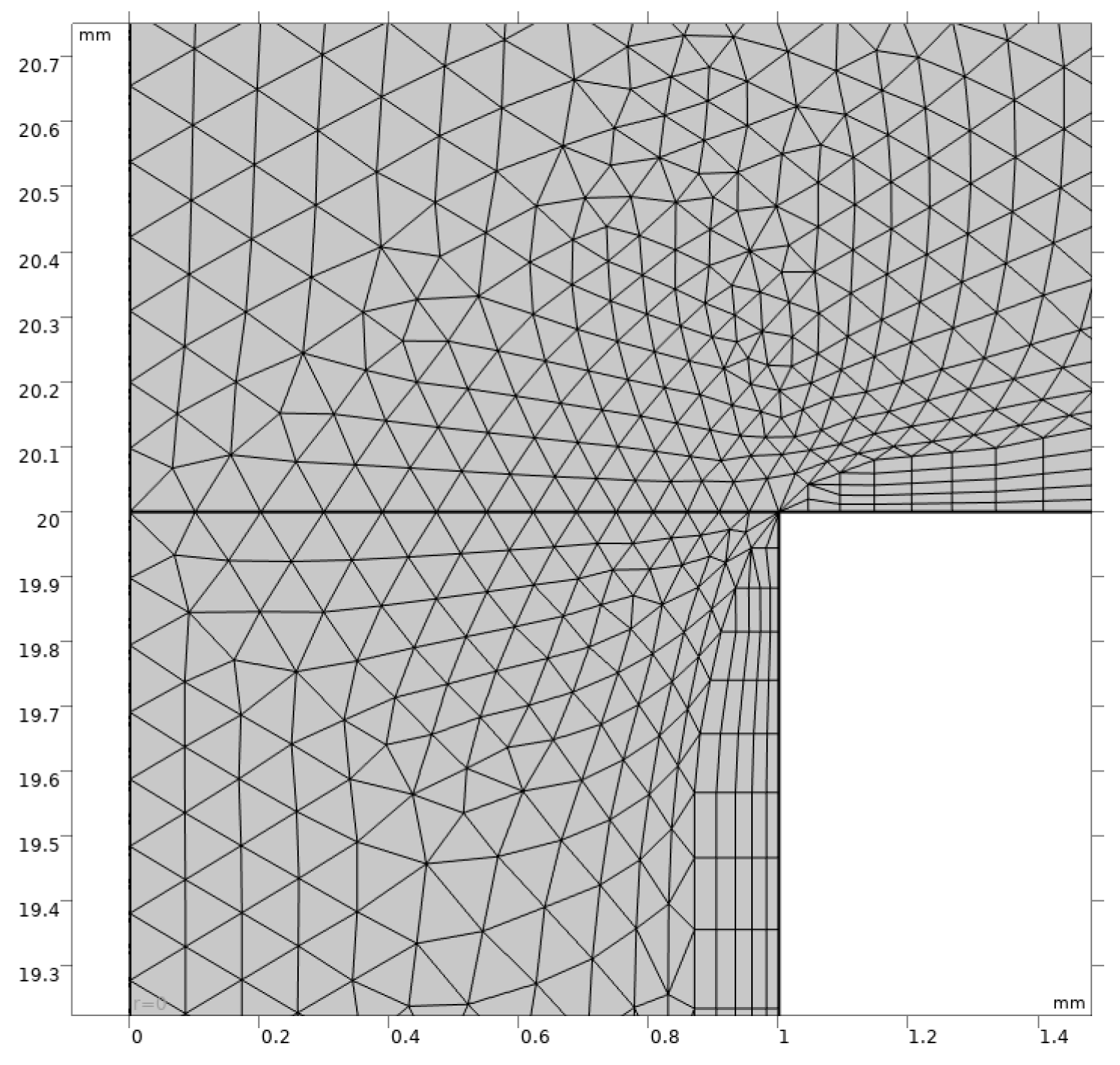

2.6. Computational Domain and Meshing

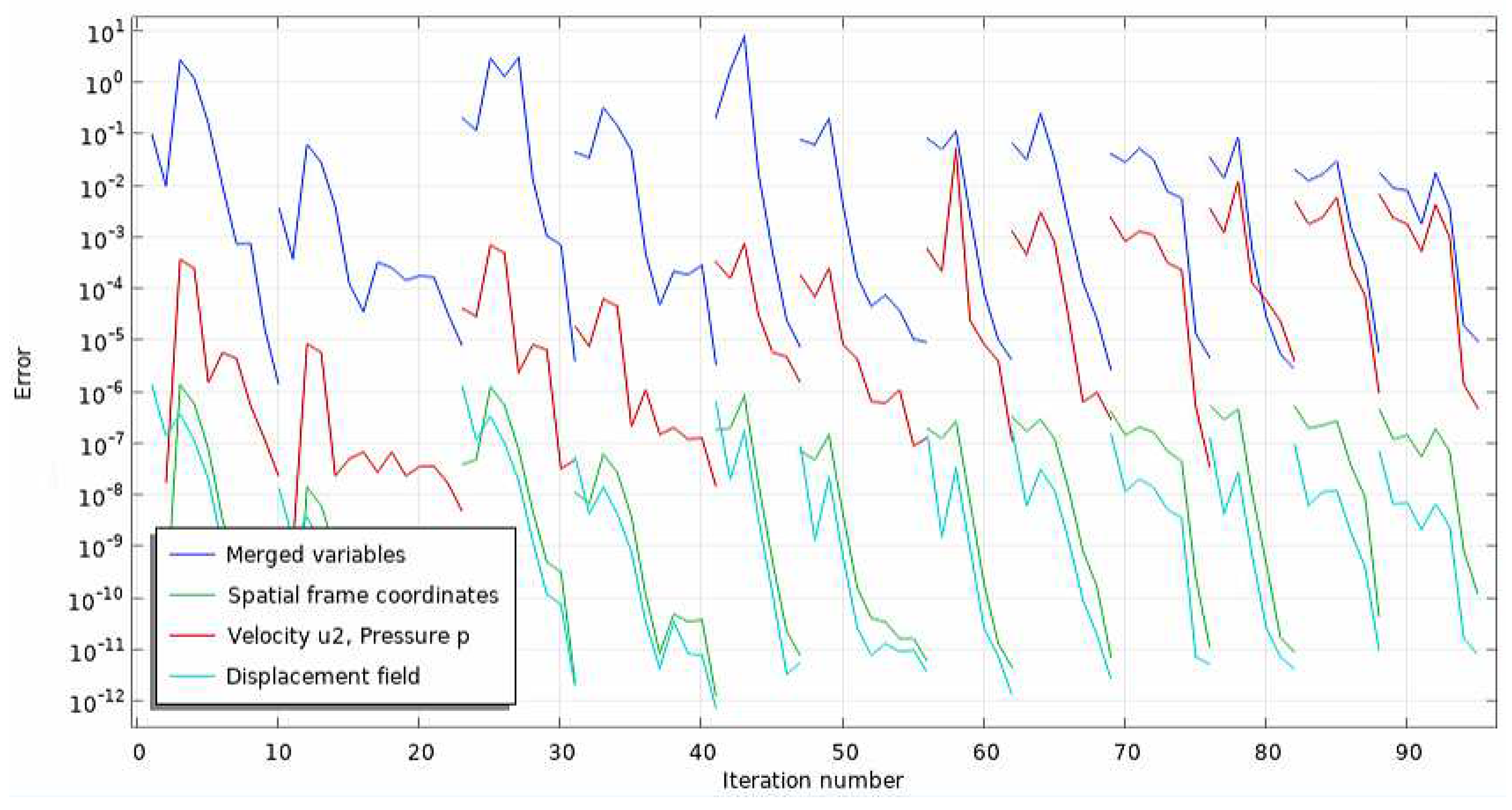

2.7. Time and Solver Settings

3. Results

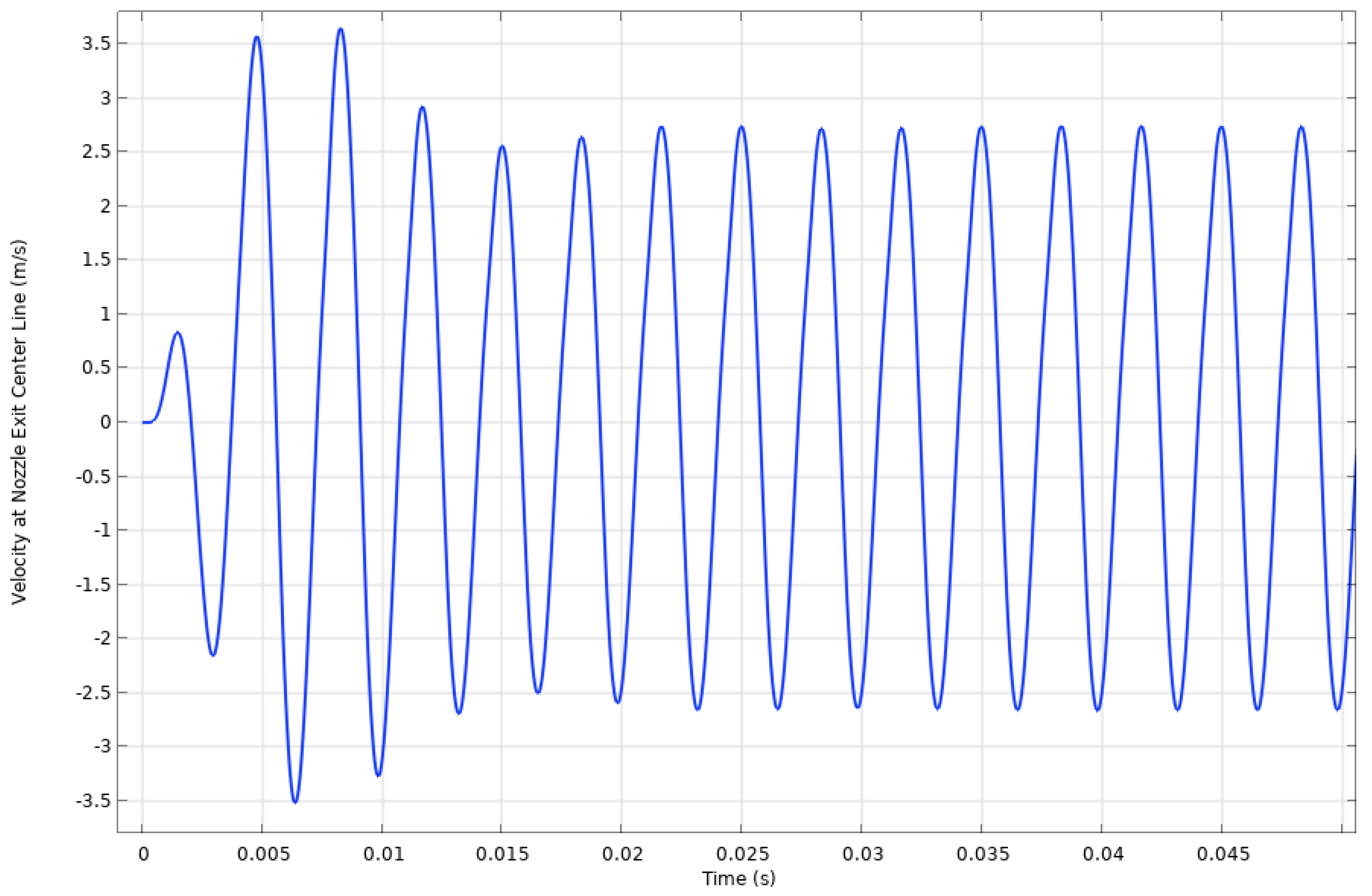

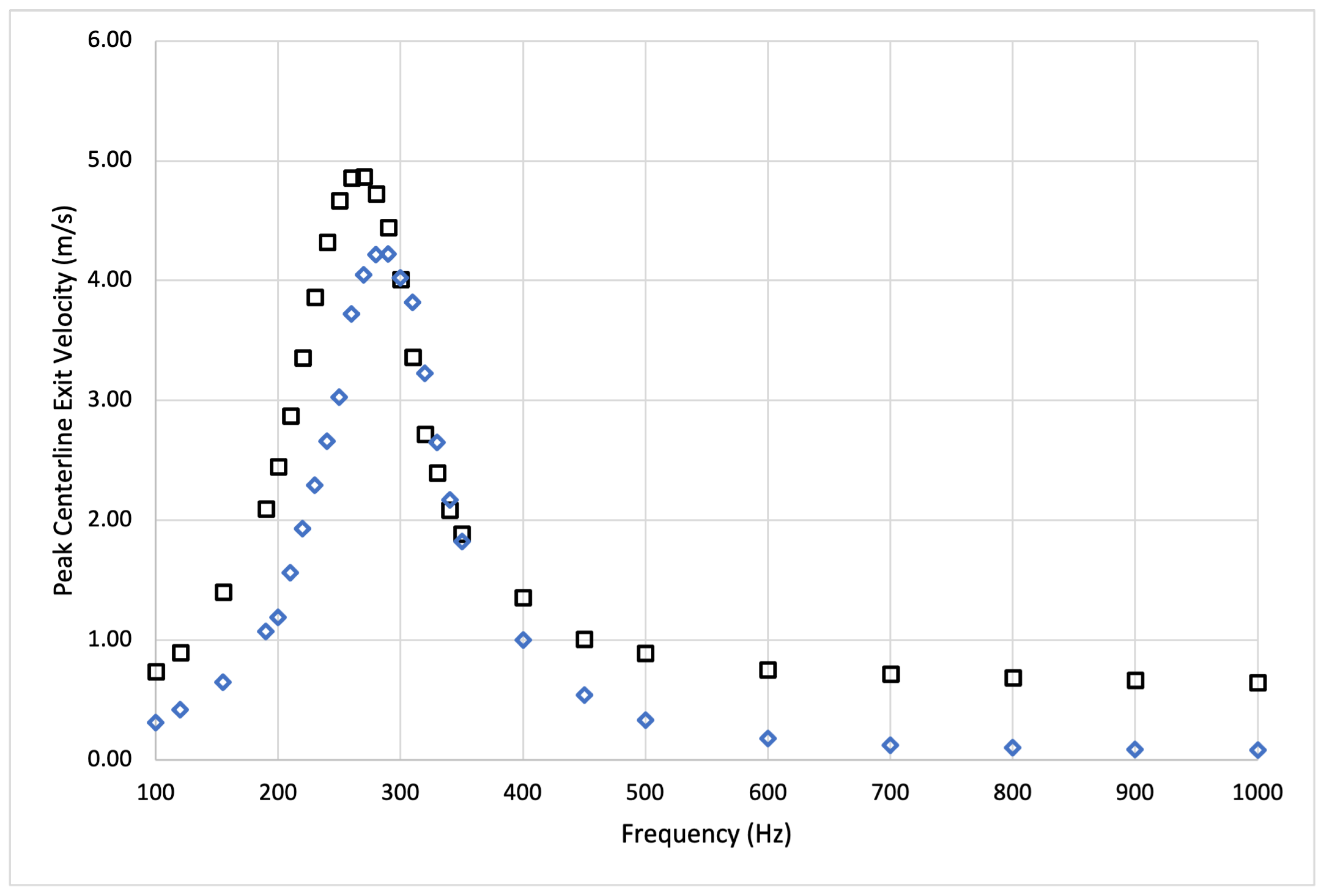

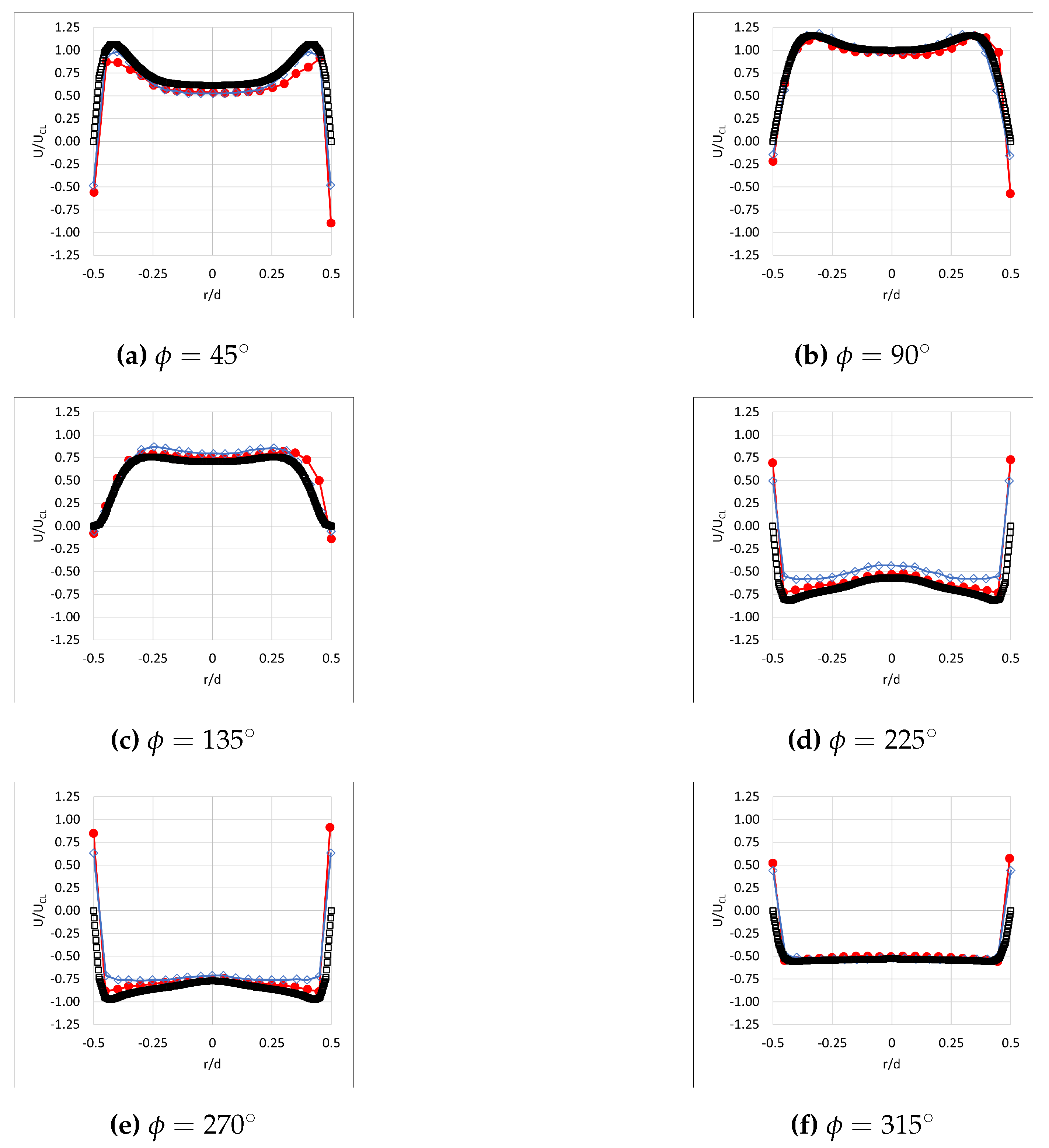

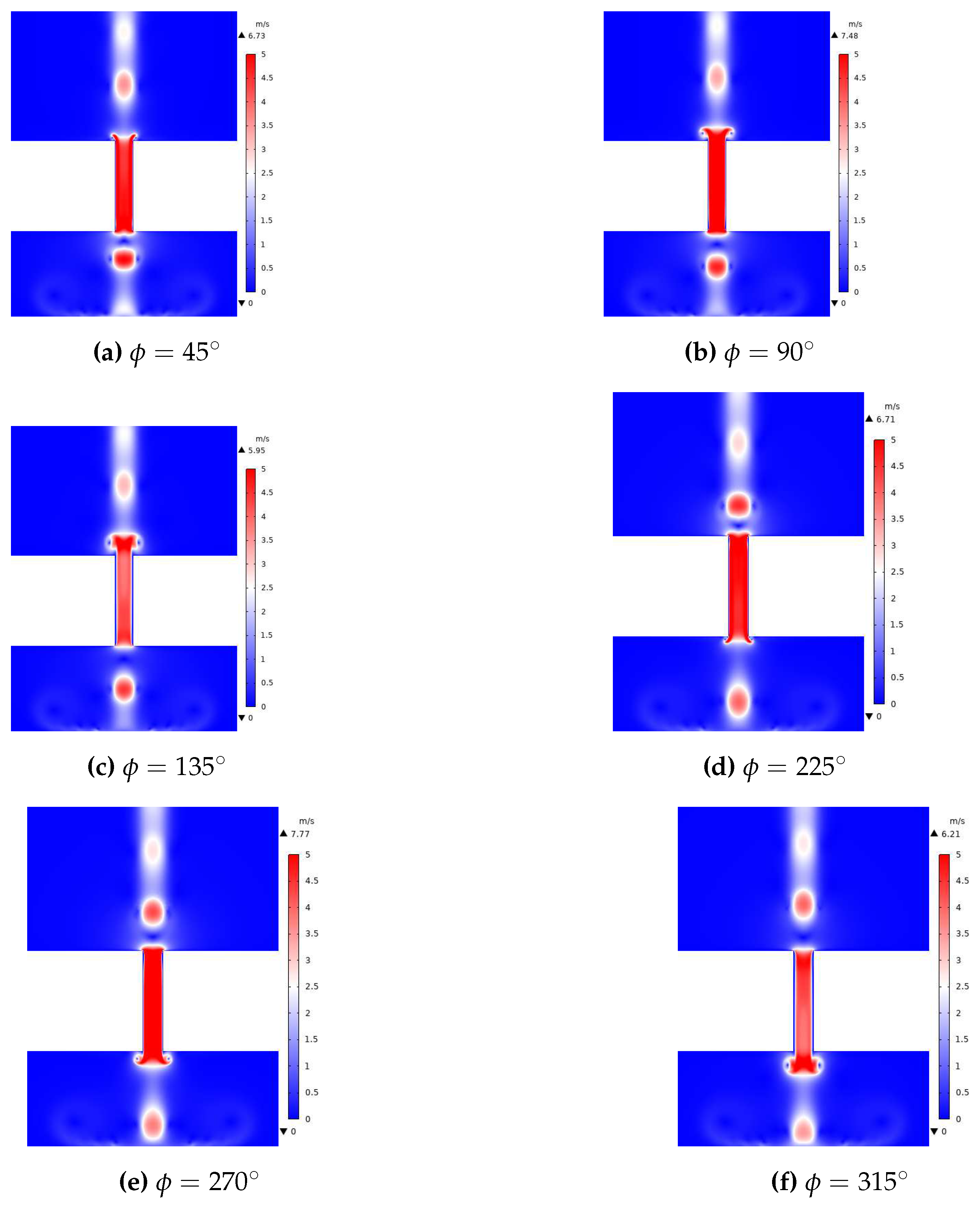

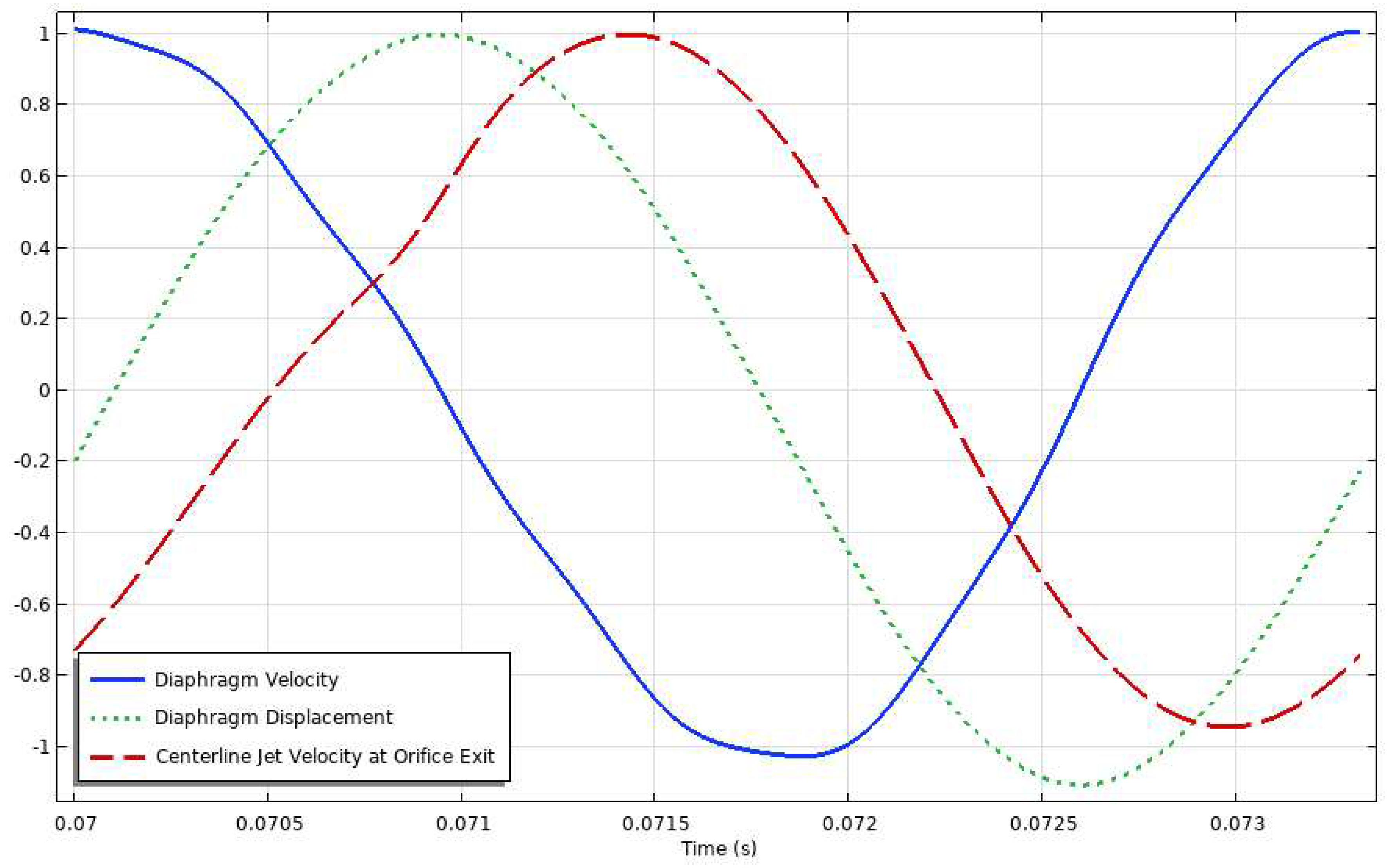

3.1. Fluids

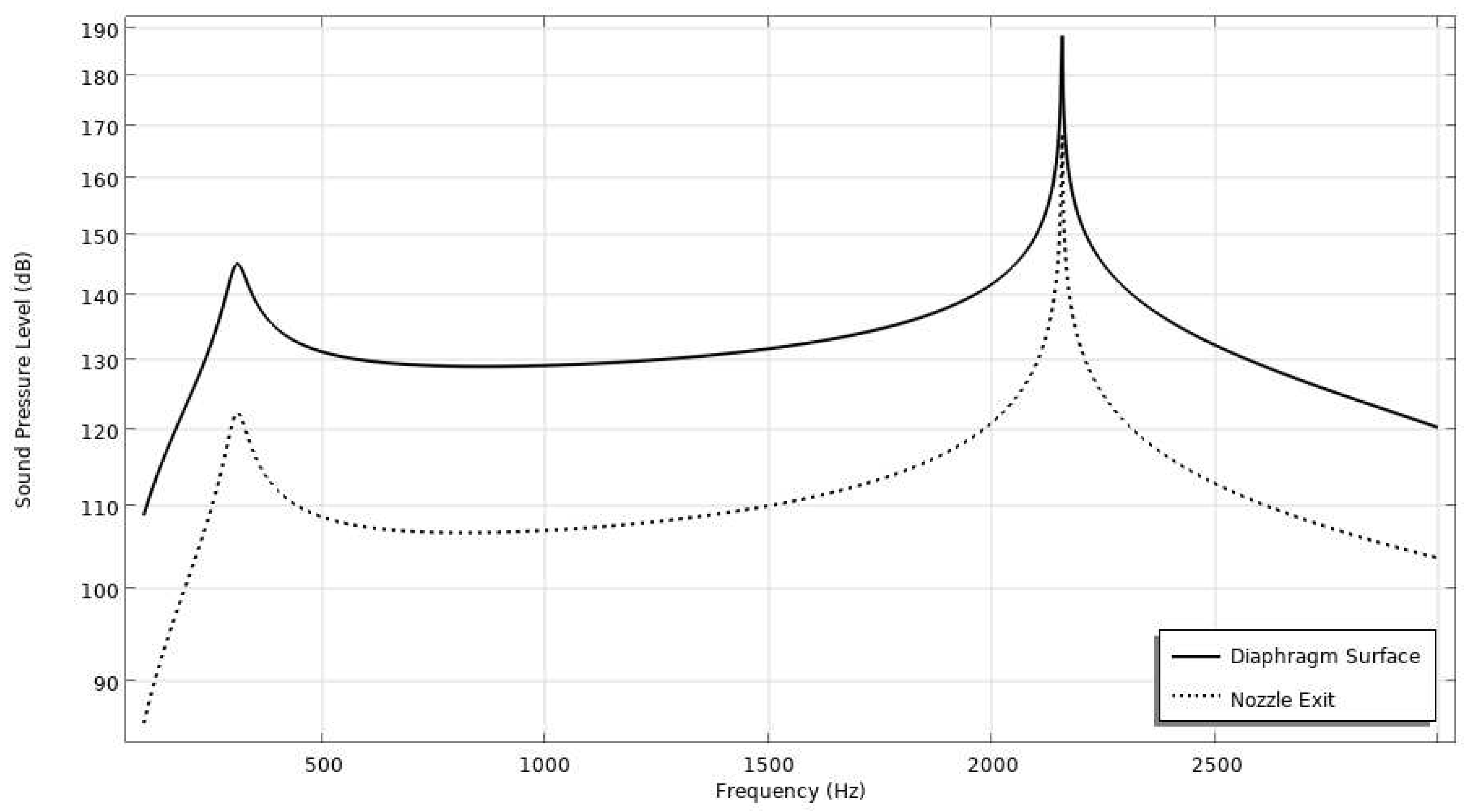

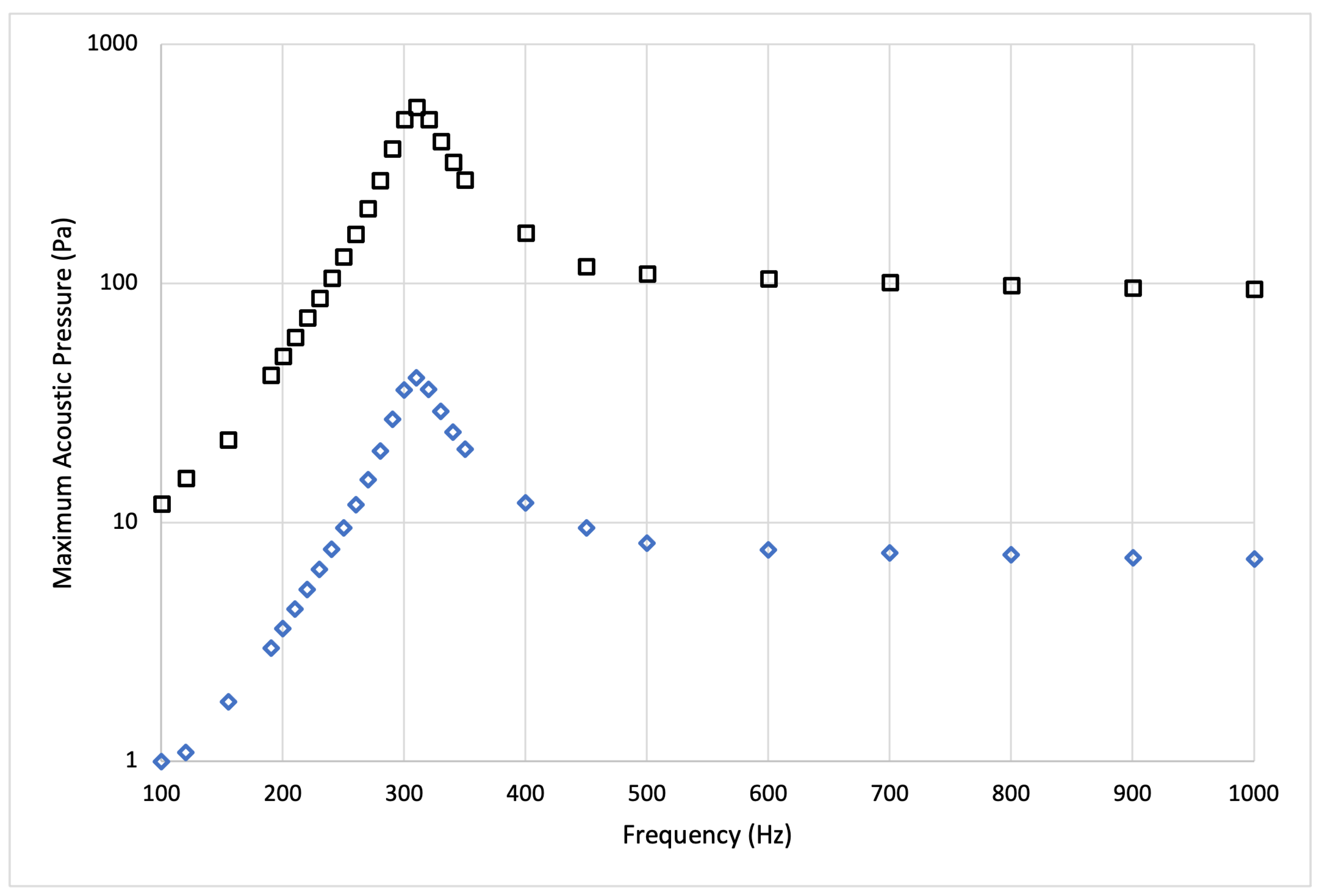

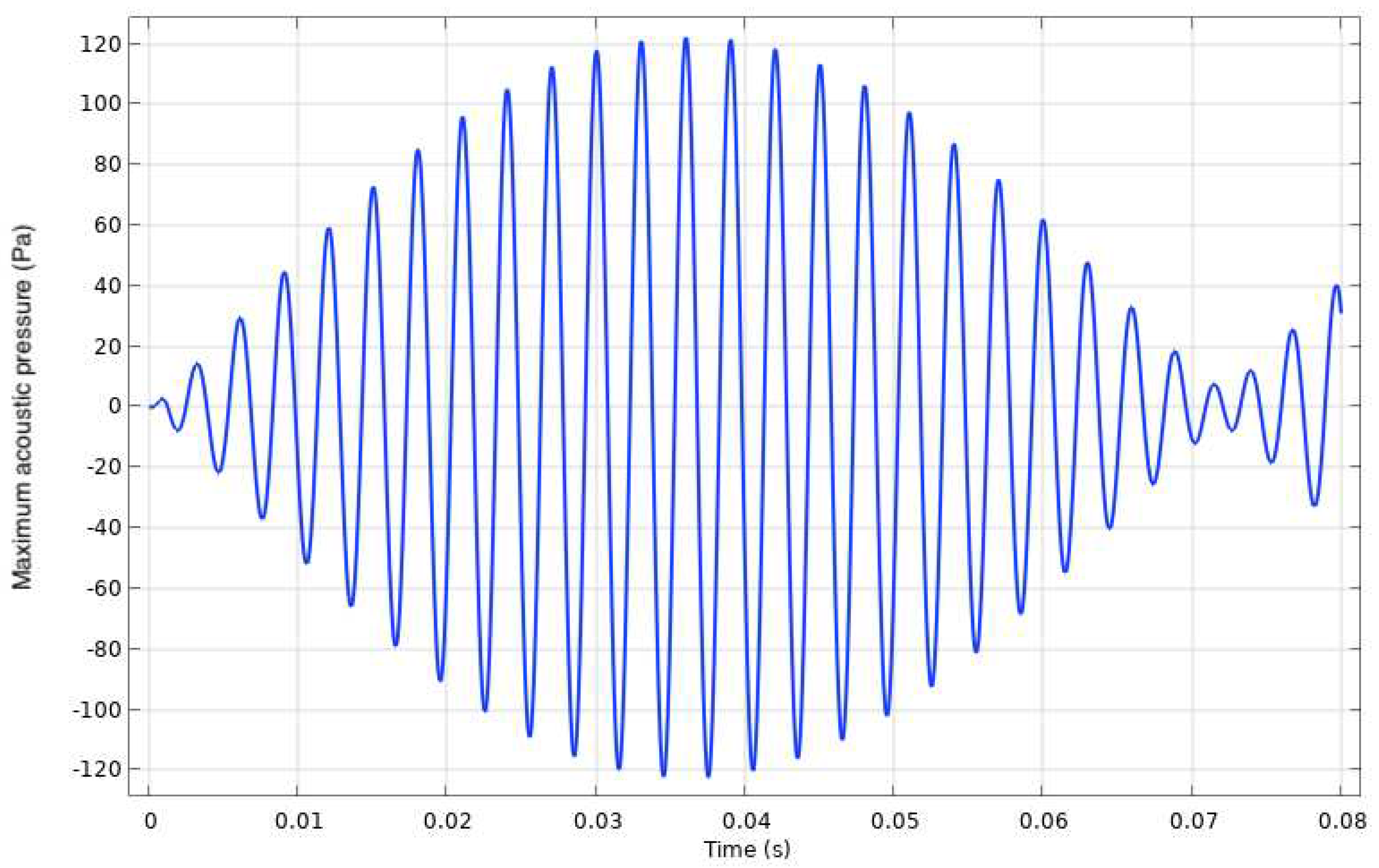

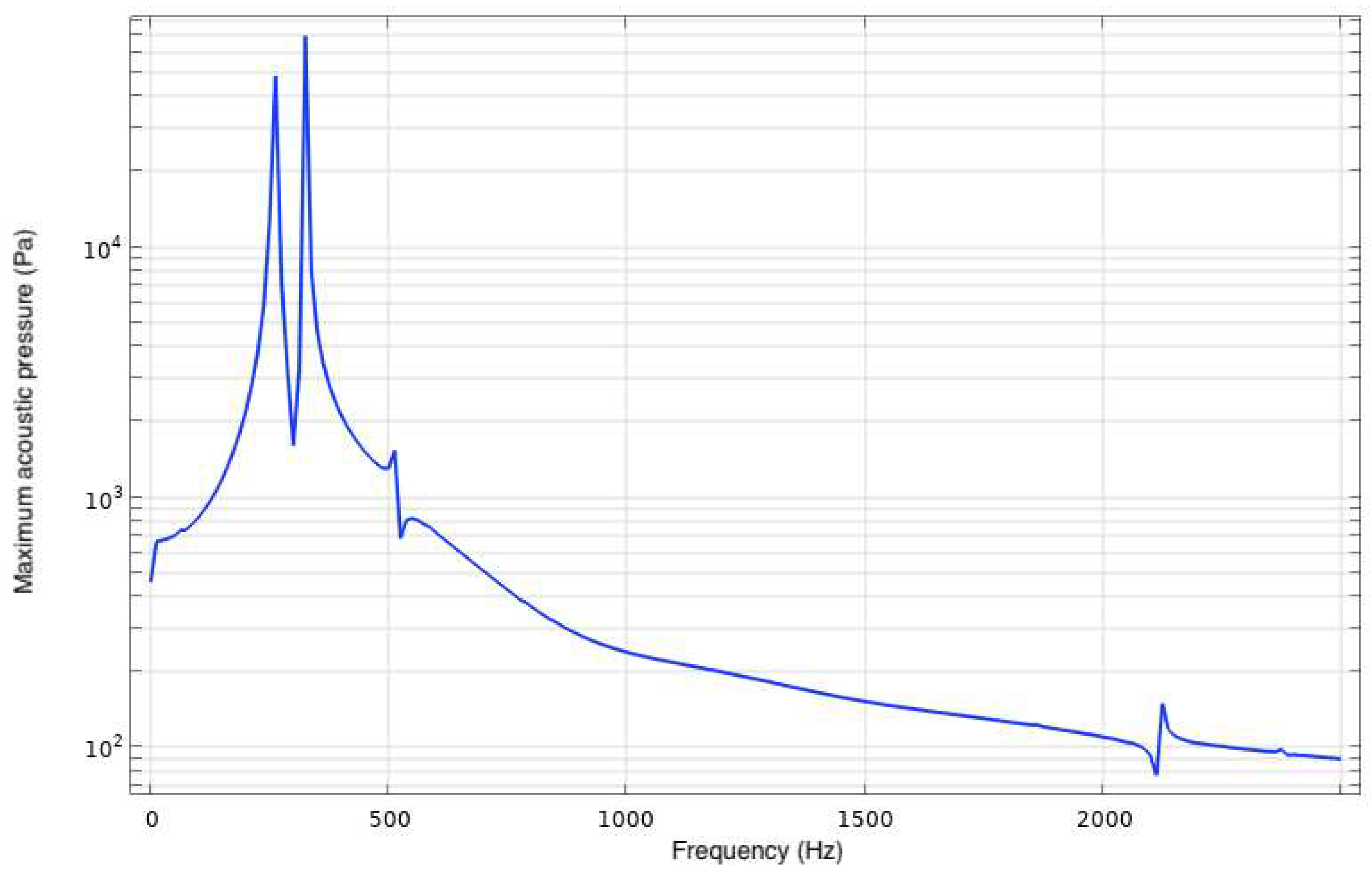

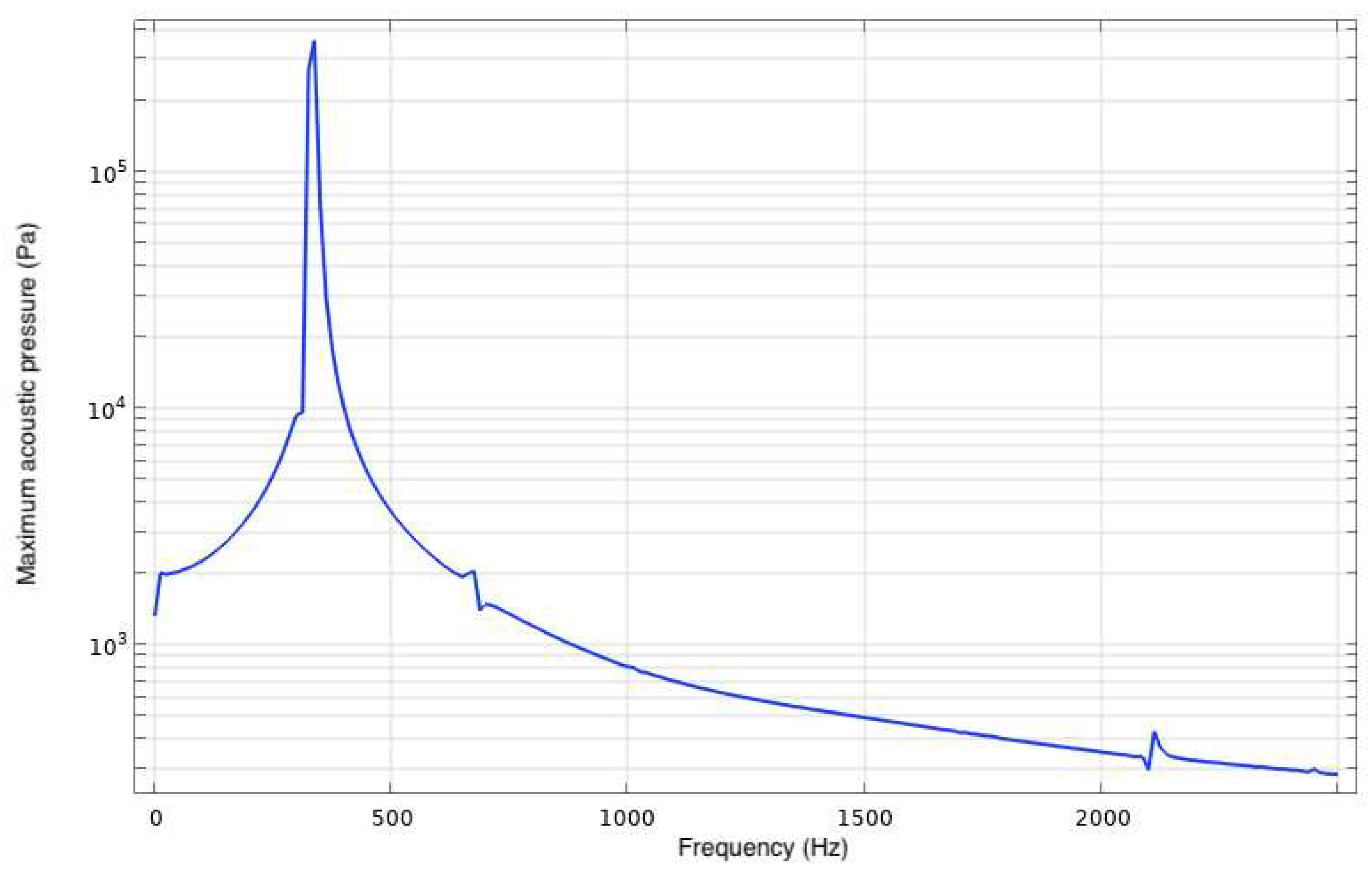

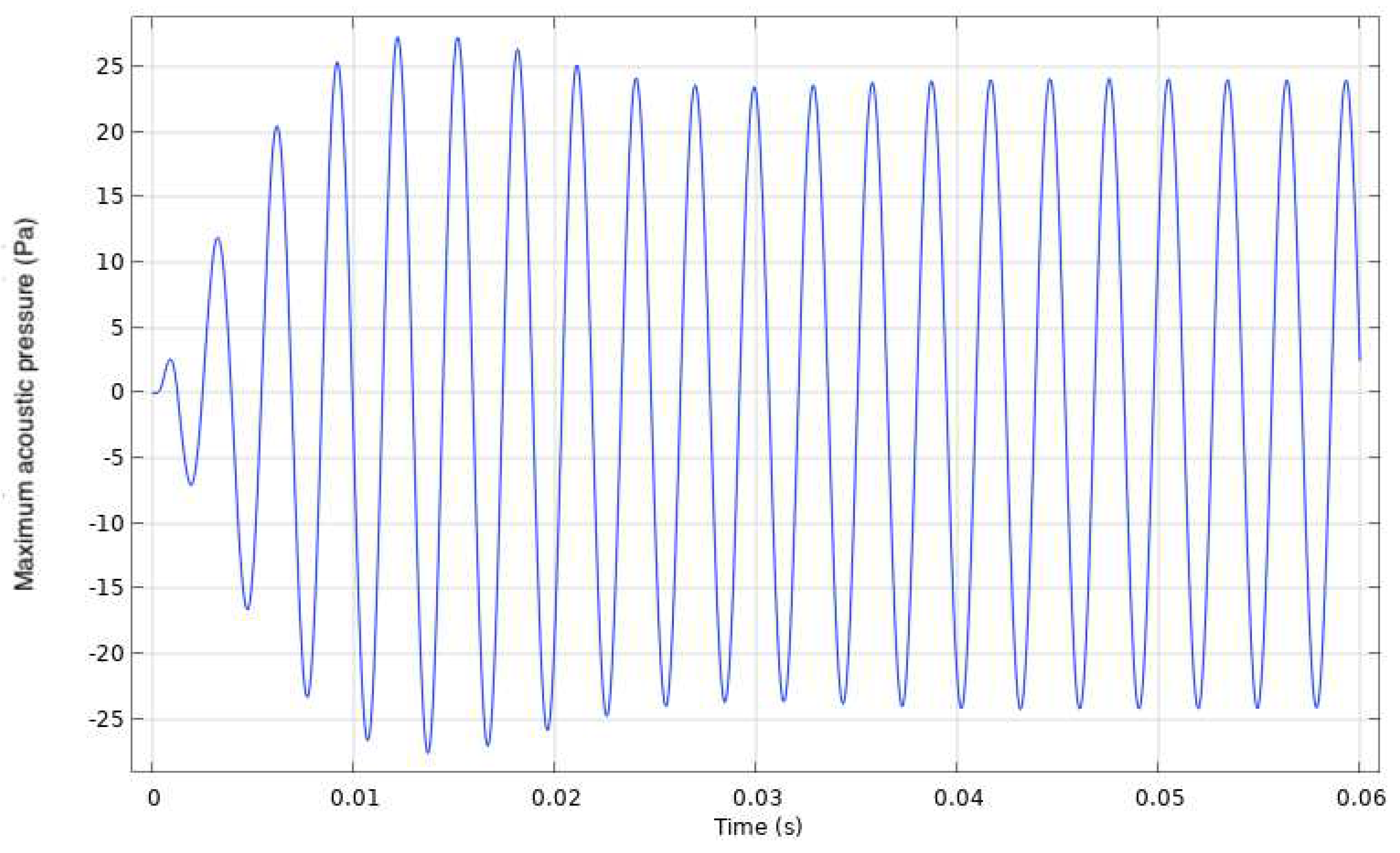

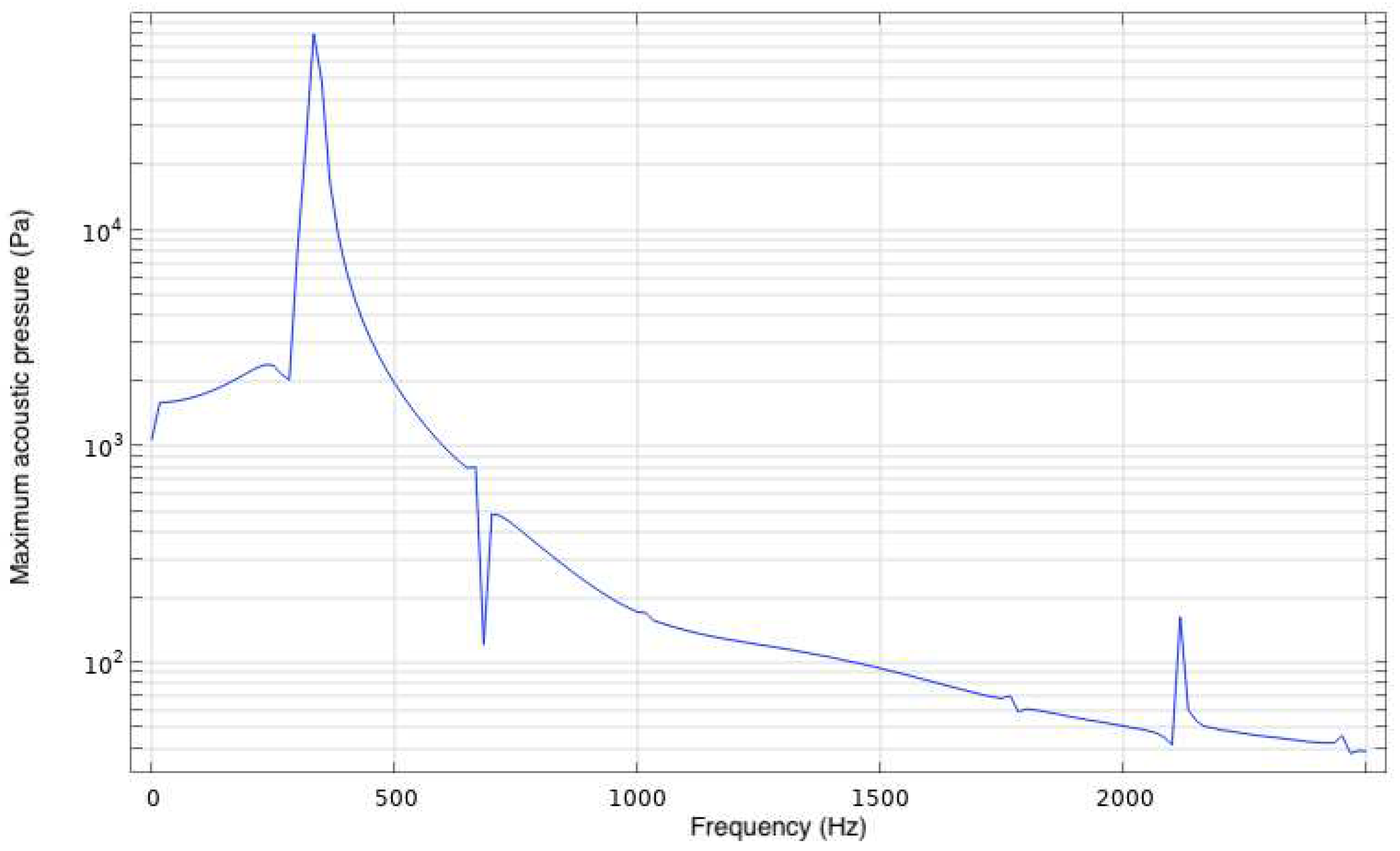

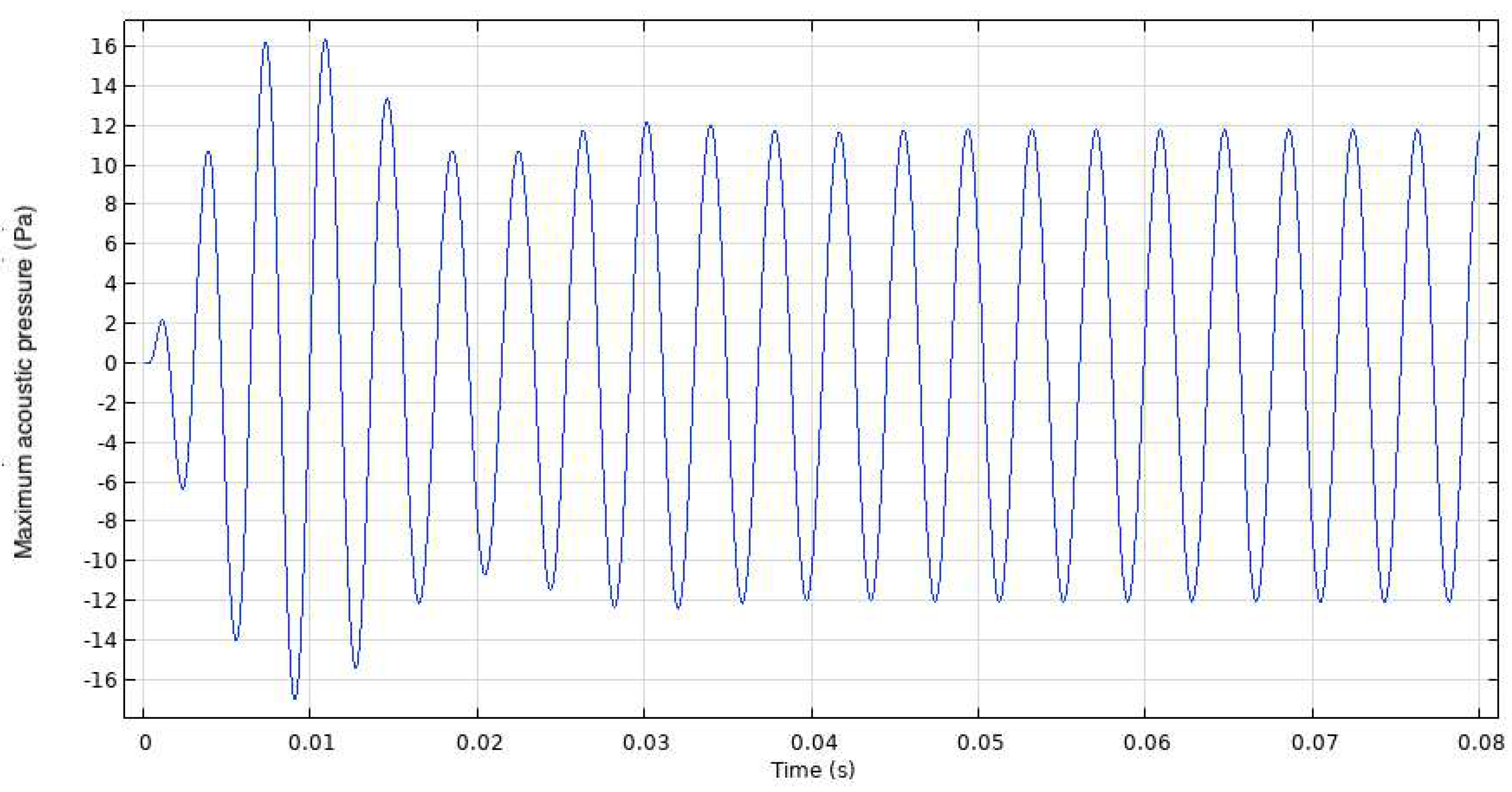

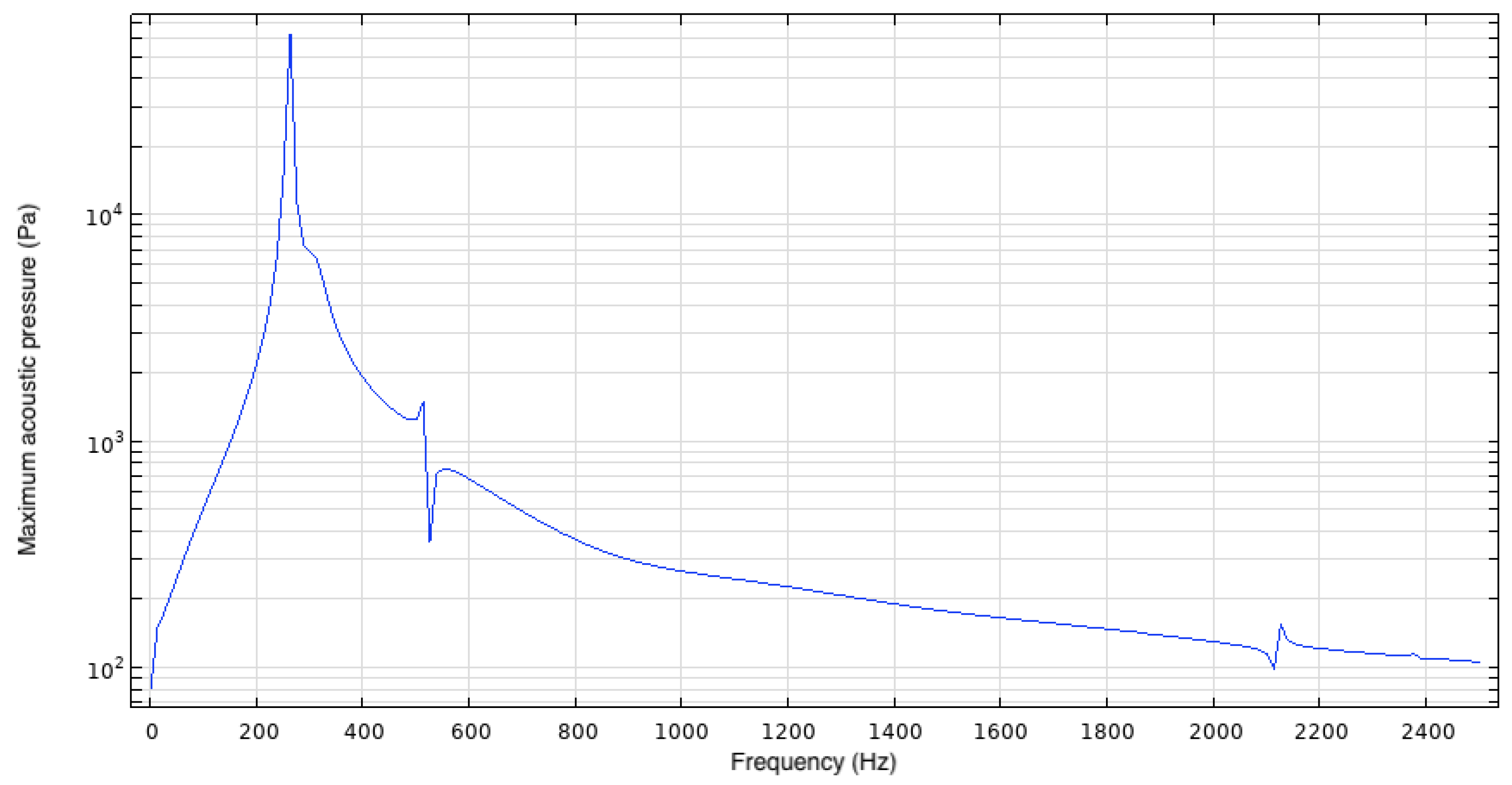

3.2. Acoustics

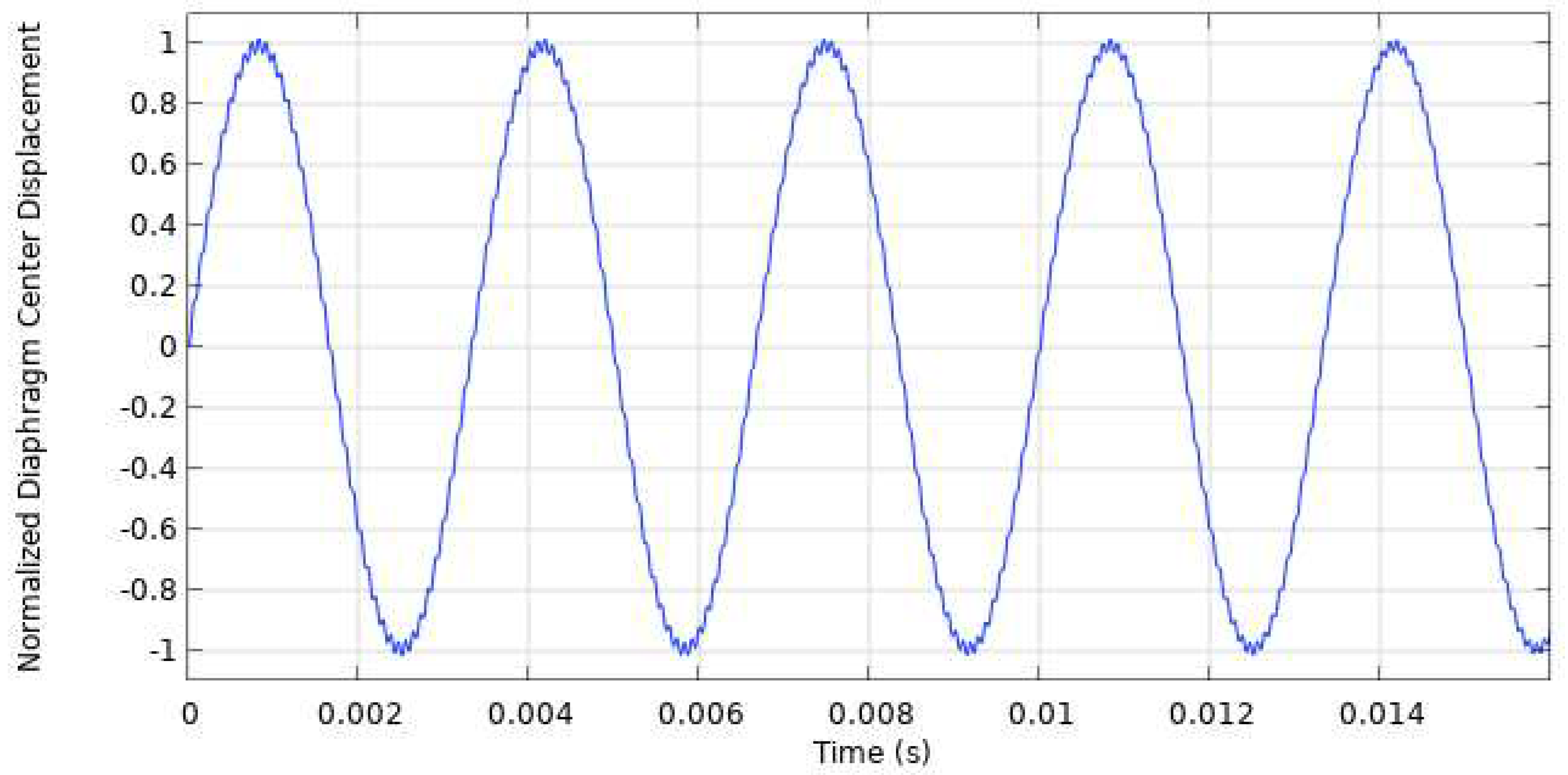

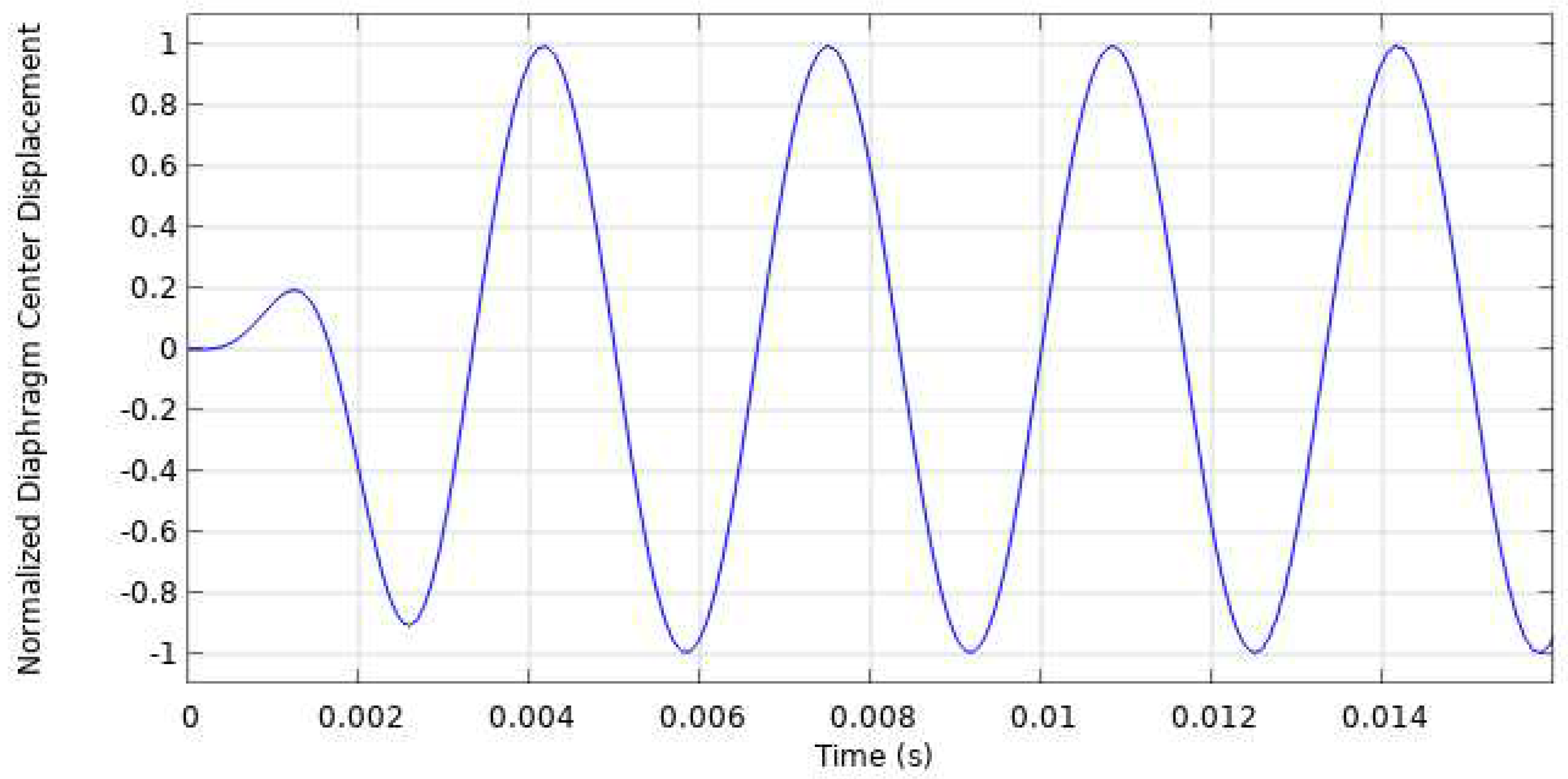

3.3. Diaphragm

4. Conclusions

References

- Shehata, A.S.; Xiao, Q.; Saqr, K.M.; Naguib, A.; Alexander, D. Passive flow control for aerodynamic performance enhancement of airfoil with its application in Wells turbine – Under oscillating flow condition. Ocean Engineering 2017, 136, 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2017.03.010. [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Mehrmann, V.; Nitsche, W. Active Flow Control - A Mathematical Challenge. Production Factor Mathematics 2010, pp. 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-11248-5. [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Yan, Q.; Wei, W.; Sullivan, P.E. Unsteady simulation of a synthetic jet actuator with cylindrical cavity using a 3-D lattice Boltzmann method. International Journal of Aerospace Engineering 2018, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9358132. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Oubahou, R.A.; He, Z.; Mickalauskas, A.; Menicovich, D. Acoustical analysis of sound generated by synthetic jet actuators. Inter-Noise 2021.

- He, Z.; Mongeau, L.; Taduri, R.; Menicovich, D. Feedforward Harmonic Suppression for Noise Control of Piezoelectrically Driven Synthetic Jet Actuators. In Proceedings of the Noise and Vibration Conference & Exhibition, 2023.

- Jabbal, M.; Jeyalingam, J. Towards the noise reduction of piezoelectrical-driven synthetic jet actuators. Sensors and Actuators, A: Physical 2017, 266, 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2017.09.036. [CrossRef]

- Arafa, N.; Sullivan, P.E.; Ekmekci, A. Jet Velocity and Acoustic Excitation Characteristics of a Synthetic Jet Actuator. Fluids 2022, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids7120387. [CrossRef]

- Arafa, N.; Sullivan, P.E.; Ekmekci, A. Noise and Jet Momentum of Synthetic Jet Actuators with Different Orifice Configurations. AIAA Journal 0, 0, 1–9, [https://doi.org/10.2514/1.J062920]. https://doi.org/10.2514/1.J062920. [CrossRef]

- Feero, M. Active Control of Separation on a Low Reynolds Number Airfoil Using Synthetic Jet Actuation. Master’s thesis, University of Toronto, 2014.

- Gallas, Q. On the Modeling and Design of Zero-Net Mass Flux Actuators. PhD thesis, University of Florida, 2005.

- Rampunggoon, P. Interaction of a Synthetic Jet with a Flat Plate Boundary Layer. PhD thesis, University of Florida, 2001.

- Utturkar, Y. Numerical Investigation of Synthetic Jet Flow Fields. PhD thesis, University of Florida, 2002.

- Utturkar, Y.; Holman, R.; Mittal, R.; Carroll, B.; Sheplak, M.; Cattafesta, L. A jet formation criterion for synthetic jet actuators. In Proceedings of the 41st aerospace sciences meeting and exhibit, 2003, p. 636.

- Holman, R.; Utturkar, Y.; Mittal, R.; Smith, B.L.; Cattafesta, L. Formation criterion for synthetic jets. AIAA Journal 2005, 43, 2110–2116. https://doi.org/10.2514/1.12033. [CrossRef]

- Kral, L.D.; Donovan, J.F.; Cain, A.B.; Cary, A.W. Numerical Simulation of Synthetic Jet Actuators. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 1997.

- Donovan, J.F.; Kral, L.D.; Gary, A.W. Active flow control applied to an airfoil. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Inc, AIAA, 1998. https://doi.org/10.2514/6.1998-210. [CrossRef]

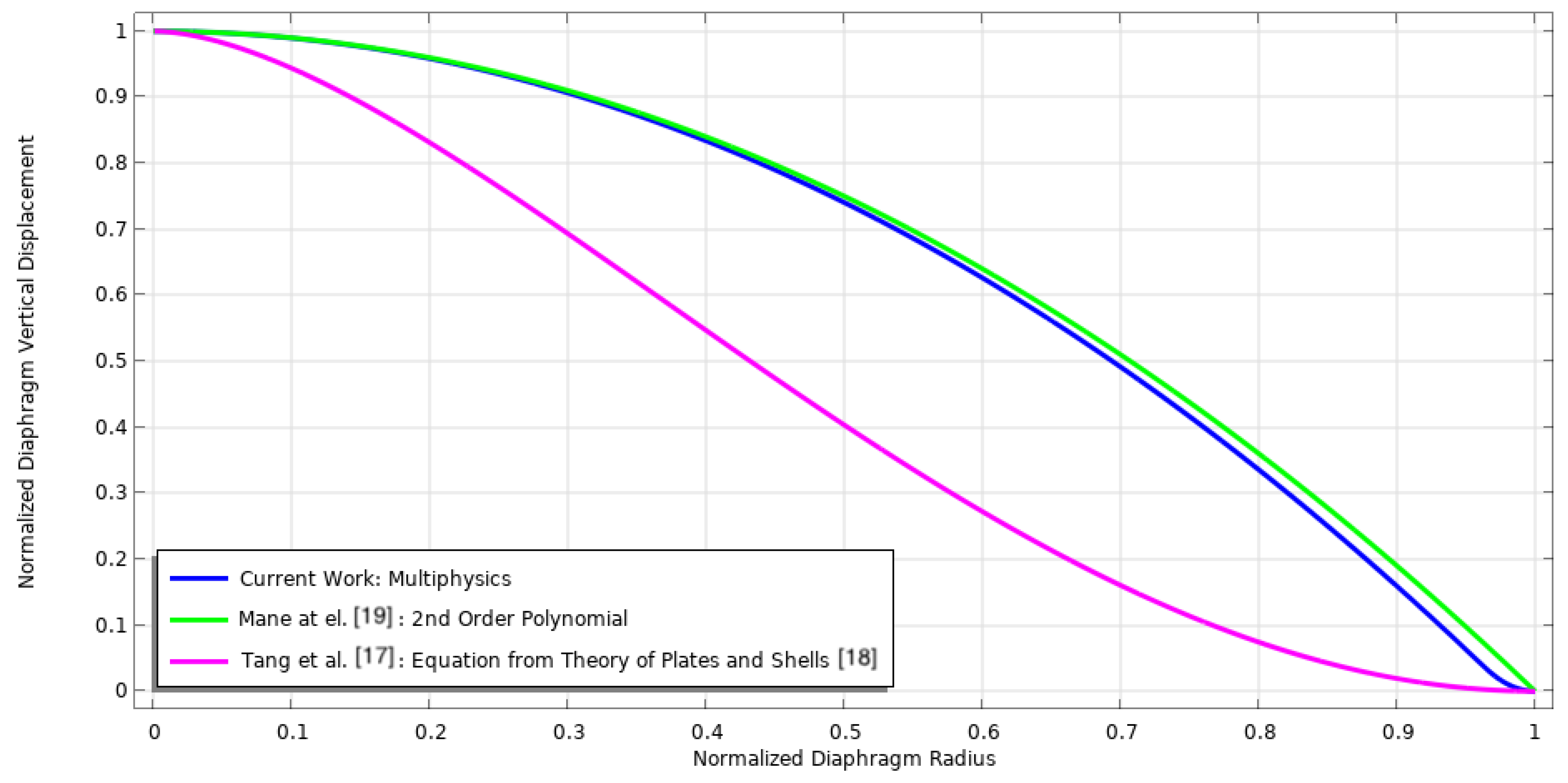

- Tang, H.; Zhong, S. 2D numerical study of circular synthetic jets in quiescent flows. Aeronautical Journal 2005, 109, 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001924000000592. [CrossRef]

- Timoshenko, S.; Woinowsky-Krieger, S. Theory of Plates and Shells, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1959.

- Mane, P.; Mossi, K.; Rostami, A.; Bryant, R.; Castro, N. Piezoelectric actuators as synthetic jets: Cavity dimension effects. Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures 2007, 18, 1175–1190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1045389X06075658. [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Puranik, B.; Agrawal, A. A numerical investigation of effects of cavity and orifice parameters on the characteristics of a synthetic jet flow. Sensors and Actuators, A: Physical 2011, 165, 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2010.11.001. [CrossRef]

- Rizzetta, D.P.; Visbal, M.R.; Stanek, M.J. Numerical investigation of synthetic-jet flowfields. AIAA journal 1999, 37, 919–927. https://doi.org/10.2514/2.811. [CrossRef]

- Ziadé, P.; Feero, M.A.; Sullivan, P.E. A numerical study on the influence of cavity shape on synthetic jet performance. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow 2018, 74, 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2018.10.001. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.N. Fluid-dynamics-based analytical model for synthetic jet actuation. AIAA Journal 2007, 45, 1841–1847. https://doi.org/10.2514/1.25427. [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.H.; Essel, E.E.; Sullivan, P.E. The interactions of a circular synthetic jet with a turbulent crossflow. Physics of Fluids 2022, 34. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0099533. [CrossRef]

- Qayoum, A.; Malik, A. Influence of the Excitation Frequency and Orifice Geometry on the Fluid Flow and Heat Transfer Characteristics of Synthetic Jet Actuators. Fluid Dynamics 2019, 54, 575–589. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0015462819040086. [CrossRef]

- Gungordu, B. Structural and Fluidic Investigation of Piezoelectric Synthetic Jet Actuators for Performance Enhancements. PhD thesis, University of Nottingham, 2021.

- Gungordu, B.; Jabbal, M.; Popov, A. Experimental and Computational Analysis of Single Crystal Piezoelectrical Driven Synthetic Jet Actuator. 2019. https://doi.org/10.13009/EUCASS2019-380. [CrossRef]

- Gungordu, B.; Jabbal, M.; Popov, A. Modelling of piezoelectrical driven synthetic jet actuators. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2021 Forum. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Inc, AIAA, 2021, pp. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2021-1306. [CrossRef]

- Feero, M.A.; Lavoie, P.; Sullivan, P.E. Influence of cavity shape on synthetic jet performance. Sensors and Actuators, A: Physical 2015, 223, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2014.12.004. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Cai, L.; Usher, T.; Jiang, Q. Fabrication and characterization of THUNDER actuators - Pre-stress-induced nonlinearity in the actuation response. Smart Materials and Structures 2009, 18. https://doi.org/10.1088/0964-1726/18/9/095033. [CrossRef]

- Mossi, K.M.; Bishop, R.P. Characterization of Different types of High Performance THUNDER™ Actuators. SPIE, 1999, pp. 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.352812. [CrossRef]

- Carazo, A.V. Revolutionary Innovations in Piezoelectric Actuators and Transformers at FACE. Department of R&D Engineering, Face Electronics, 6 2003.

- Bryant, R.G. LaRC-SI: A Soluble Aromatic Polyimide. High Performance Polymers 1996, 8, 607 – 615. https://doi.org/10.1088/0954-0083/8/4/009. [CrossRef]

- Whitley, K.S.; Gates, T.S.; Hinkley, J.A.; Nicholson, L.M. Mechanical Properties of LaRC TM SI Polymer for a Range of Molecular Weights. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Langley Research Center. 2000.

- Durán, D.C.; López, O.D. Computational Modeling of Synthetic Jets. In Proceedings of the COMSOL Conference, 2010.

- Zhang, Q.M.; Zhao, J. Electromechanical properties of lead zirconate titanate piezoceramics under the influence of mechanical stresses. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control 1999, 46, 1518–1526. https://doi.org/10.1109/58.808876. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.T. Effect of damping and relaxed clamping on a new vibration theory of piezoelectric diaphragms. Sensors and Actuators, A: Physical 2011, 169, 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2011.04.005. [CrossRef]

- COMSOL AB. Acoustics Module User’s Guide, 2018.

- COMSOL AB. COMSOL CFD Module User’s Guide, 2018.

- COMSOL AB. Structural Mechanics Module User’s Guide, 2017.

- Celik, I.B.; Ghia, U.; Roache, P.J.; Freitas, C.J.; Coleman, H.; Raad, P.E. Procedure for estimation and reporting of uncertainty due to discretization in CFD applications. Journal of Fluids Engineering, Transactions of the ASME 2008, 130, 0780011–0780014. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2960953. [CrossRef]

- COMSOL AB. COMSOL Multiphysics Reference Manual, 2019.

- Jensen, M.H. How to Model Thermoviscous Acoustics in COMSOL Multiphysics, 2014.

- White, F.M. Viscous Fluid Flow; McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1979.

- Buren, T.V.; Whalen, E.; Amitay, M. Achieving a High-Speed and Momentum Synthetic Jet Actuator. Journal of Aerospace Engineering 2016, 29. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)as.1943-5525.0000530. [CrossRef]

- Mallinson, S.G.; Hong, G.; Reizes, J.A. Some characteristics of synthetic jets. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Inc, AIAA, 1999. https://doi.org/10.2514/6.1999-3651. [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, A.; Chiatto, M.; de Luca, L. Measurements versus numerical simulations for slotted synthetic jet actuator. Actuators 2018, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/act7030059. [CrossRef]

- de M Mello, H.C.; Catalano, F.M.; de Souza, L.F. Numerical Study of Synthetic Jet Actuator Effects in Boundary Layers. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering 2007, XXIX.

- Lesbros, S.; Ozawa, T.; Hong, G. Numerical modeling of synthetic jets with cross flow in a boundary layer at an adverse pressure gradient. In Proceedings of the 3rd AIAA Flow Control Conference, 2006, p. 3690.

| 1 | COMSOL libraries and modules mentioned in the current work are italiczed for emphasis. |

| 2 | Phase angle, . indicates at what point in a cycle (one period) a measurement or computation was made. An angle of corresponds to the maximum expulsion velocity. |

| Layer | Material | b (mm) | D (mm) | E (GPa) | ν |

| Substrate | Stainless Steel 302 | 0.1524 | 32.77 | 193 | 0.29 |

| Adhesive | LaRC-SI | 0.0381 | 31.75 | 3.8 | 0.4 |

| Piezoelectric | PZT-5A | 0.1905 | 31.75 | 63 | 0.31 |

| Adhesive | LaRC-SI | 0.0381 | 30.73 | 3.8 | 0.4 |

| Superstrate | Aluminum Alloy 2024 | 0.0254 | 30.73 | 69 | 0.33 |

| 12.03 | 7.52 | 7.51 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7.52 | 12.03 | 7.51 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7.51 | 7.51 | 11.09 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.11 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.11 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.26 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.29 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.29 | 0 | 0 |

| -5.35 | -5.35 | 15.78 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No. of Cells | 200 | 448 | 1070 | 2150 | 4565 | 9078 |

| Displacement (mm) | 0.1295 | 0.1297 | 0.1299 | 0.1301 | 0.1302 | 0.1302 |

| Excitation Frequency (Hz) | 270 | 285 | 300 | 310 |

| Max. Centreline Velocity: 2-D (m/s) | 3.98 | 4.33 | 4.42 | 3.80 |

| Max. Centreline Velocity: 3-D (m/s) | 4.02 | 4.39 | 4.49 | 3.85 |

| Theoretical | Model | Experiment | |

| Frequency (Hz) | 307.0 | 267.1 | 286.0 |

| Jet Velocity (m/s) | N/A | 5.05 | 4.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).