Submitted:

27 December 2023

Posted:

28 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Executive functions and academic achievements

1.2. Executive functions and trait anxiety

1.3. Emotion regulation strategies

1.4. Metacognitive beliefs

1.5. Present study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Materials

3. Results

3.1. Data Exclusion

3.2. Preliminary Analysis

3.3. Anxiety

3.3.1. Lying

3.3.2. Emotion regulation strategies

3.3.3. Metacognitive beliefs

3.4. Metacognitive beliefs and emotion regulation strategies

3.5. Executive functioning and emotion regulation strategies

3.6. Analysis of the relationships between our main variables

3.6.1. Pearson correlation

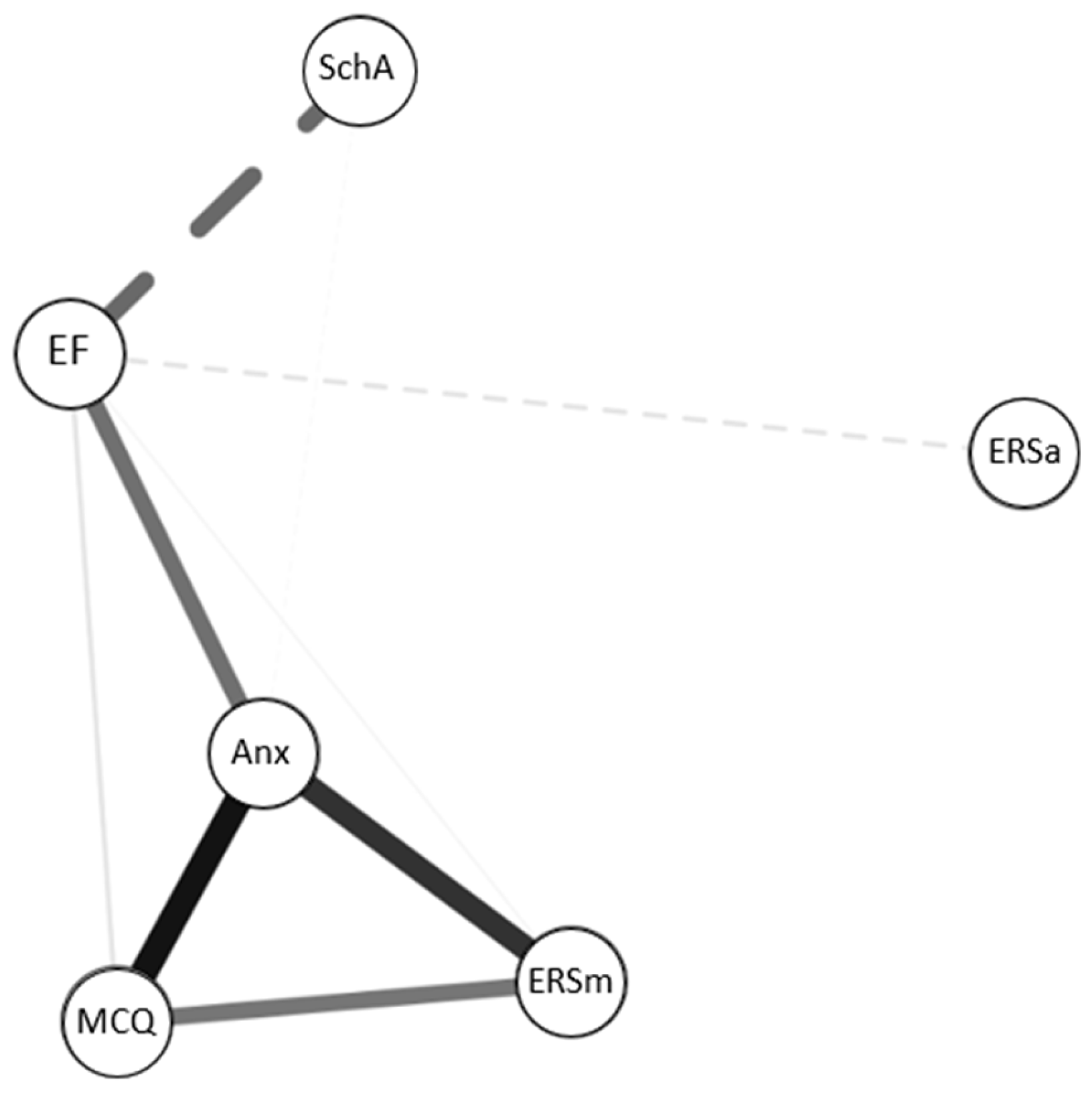

3.6.2. Network analysis

3.6.2.1. Data analytic plan

3.6.2.2. Network visualization and treatment

3.6.2.3. Standard network analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Anxiety

4.2. Executive functioning

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kessler, R.C.; Foster, C.L.; Saunders, W.B.; Stang, P.E. Social Consequences of Psychiatric Disorders, I: Educational Attainment. American journal of psychiatry 1995, 152, 1026–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ameringen, M.; Mancini, C.; Farvolden, P. The Impact of Anxiety Disorders on Educational Achievement. Journal of anxiety disorders 2003, 17, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzone, L.; Ducci, F.; Scoto, M.C.; Passaniti, E.; D’Arrigo, V.G.; Vitiello, B. The Role of Anxiety Symptoms in School Performance in a Community Sample of Children and Adolescents. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robson, D.A.; Johnstone, S.J.; Putwain, D.W.; Howard, S. Test Anxiety in Primary School Children: A 20-Year Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of School Psychology 2023, 98, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults. 1983. [Google Scholar]

- William Li, H.C.; Lopez, V. Do Trait Anxiety and Age Predict State Anxiety of School-Age Children? Journal of Clinical Nursing 2005, 14, 1083–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eysenck, M.W.; Moser, J.S.; Derakshan, N.; Hepsomali, P.; Allen, P. A Neurocognitive Account of Attentional Control Theory: How Does Trait Anxiety Affect the Brain’s Attentional Networks? Cognition and Emotion 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobias, S. The Impact of Test Anxiety on Cognition in School Learning. Advances in test anxiety research 1992, 7, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake, A.; Friedman, N.P.; Emerson, M.J.; Witzki, A.H.; Howerter, A.; Wager, T.D. The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions and Their Contributions to Complex “Frontal Lobe” Tasks: A Latent Variable Analysis. Cognitive psychology 2000, 41, 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, J.R.; Miller, P.H.; Naglieri, J.A. Relations between Executive Function and Academic Achievement from Ages 5 to 17 in a Large, Representative National Sample. Learning and individual differences 2011, 21, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, C.; Diamond, A. Biological Processes in Prevention and Intervention: The Promotion of Self-Regulation as a Means of Preventing School Failure. Development and psychopathology 2008, 20, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcauley, T.; Chen, S.; Goos, L.; Schachar, R.; Crosbie, J. Is the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function More Strongly Associated with Measures of Impairment or Executive Function? Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 2010, 16, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gioia, G.A.; Isquith, P.K.; Guy, S.C.; Kenworthy, L. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function: BRIEF; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, 2000b. [Google Scholar]

- Ten Eycke, K.D.; Dewey, D. Parent-Report and Performance-Based Measures of Executive Function Assess Different Constructs. Child Neuropsychology 2016, 22, 889–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyongesa, M.K.; Ssewanyana, D.; Mutua, A.M.; Chongwo, E.; Scerif, G.; Newton, C.R.; Abubakar, A. Assessing Executive Function in Adolescence: A Scoping Review of Existing Measures and Their Psychometric Robustness. Frontiers in psychology 2019, 10, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toplak, M.E.; West, R.F.; Stanovich, K.E. Practitioner Review: Do Performance-Based Measures and Ratings of Executive Function Assess the Same Construct? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2013, 54, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanovich, K. Rationality and the Reflective Mind; Oxford University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stanovich, K.E. Distinguishing the Reflective, Algorithmic, and Autonomous Minds: Is It Time for a Tri-Process Theory? 2009b. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck, M.W.; Calvo, M.G. Anxiety and Performance: The Processing Efficiency Theory. Cognition & emotion 1992, 6, 409–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, M.W.; Derakshan, N.; Santos, R.; Calvo, M.G. Anxiety and Cognitive Performance: Attentional Control Theory. Emotion 2007, 7, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, M.W.; Derakshan, N. New Perspectives in Attentional Control Theory. Personality and Individual Differences 2011, 50, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, M.W. Attention and Arousal; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1982; ISBN 978-3-642-68392-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinginna, P.R.; Kleinginna, A.M. A Categorized List of Emotion Definitions, with Suggestions for a Consensual Definition. Motivation and emotion 1981, 5, 345–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.A. Emotion Regulation: A Theme in Search of Definition. Monographs of the society for research in child development 1994, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnefski, N.; Kraaij, V.; Spinhoven, P. Negative Life Events, Cognitive Emotion Regulation and Emotional Problems. Personality and Individual differences 2001, 30, 1311–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, J.Ö.; Naumann, E.; Holmes, E.A.; Tuschen-Caffier, B.; Samson, A.C. Emotion Regulation Strategies in Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of youth and adolescence 2016, 46, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldao, A.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Schweizer, S. Emotion-Regulation Strategies across Psychopathology: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clinical psychology review 2010, 30, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, R.; Kitahara, M. The relationship between Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) and depression, anxiety: Meta-analysis. Shinrigaku Kenkyu 2016, 87, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnefski, N.; Kraaij, V. Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire–Development of a Short 18-Item Version (CERQ-Short). Personality and individual differences 2006, 41, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.T. Acceptance and Change in the Treatment of Eating Disorders and Obesity. Behavior Therapy 1996, 27, 417–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Mennin, D.S.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Emotion Dysregulation and Adolescent Psychopathology: A Prospective Study. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2011, 49, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantrip, C.; Isquith, P.K.; Koven, N.S.; Welsh, K.; Roth, R.M. Executive Function and Emotion Regulation Strategy Use in Adolescents. Applied Neuropsychology: Child 2016, 5, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullone, E.; Taffe, J. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (ERQ–CA): A Psychometric Evaluation. Psychological assessment 2012, 24, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDermott, S.T.; Gullone, E.; Allen, J.S.; King, N.J.; Tonge, B. The Emotion Regulation Index for Children and Adolescents (ERICA): A Psychometric Investigation. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 2010, 32, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pe, M.L.; Koval, P.; Kuppens, P. Executive Well-Being: Updating of Positive Stimuli in Working Memory Is Associated with Subjective Well-Being. Cognition 2013, 126, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmeichel, B.J.; Volokhov, R.N.; Demaree, H.A. Working Memory Capacity and the Self-Regulation of Emotional Expression and Experience. Journal of personality and social psychology 2008, 95, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmeichel, B.J.; Demaree, H.A. Working Memory Capacity and Spontaneous Emotion Regulation: High Capacity Predicts Self-Enhancement in Response to Negative Feedback. Emotion 2010, 10, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkus, E. Effects of Working Memory Training on Emotion Regulation: Transdiagnostic Review. PsyCh Journal 2020, 9, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, G.C.; Ty, W.E.G. The Effects of Emotional Working Memory Training on Trait Anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, A. Metacognitive Therapy for Anxiety and Depression; Guilford press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Flavell, J.H.; Miller, P.H.; Miller, S.A. Cognitive Development; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1985; Vol. 338. [Google Scholar]

- Pennequin, V.; Lunais, M. La Métacognition Chez Les Adolescents Présentant Des Troubles de La Conduite et Du Comportement: Humeurs et Expériences Métacognitives. Enfance 2013, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, A.; Matthews, G. Modelling Cognition in Emotional Disorder: The S-REF Model. Behaviour research and therapy 1996, 34, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright-Hatton, S.; Wells, A. Beliefs about Worry and Intrusions: The Meta-Cognitions Questionnaire and Its Correlates. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 1997, 11, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordahl, H.; Hjemdal, O.; Hagen, R.; Nordahl, H.M.; Wells, A. What Lies beneath Trait-Anxiety? Testing the Self-Regulatory Executive Function Model of Vulnerability. Frontiers in psychology 2019, 10, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, C.R.; Richmond, B.O. What I Think and Feel: A Revised Measure of Children’s Manifest Anxiety. Journal of abnormal child psychology 1978, 6, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, C.R.; Richmond, B.O. Échelle Révisée d’anxiété Manifeste Pour Enfant (R-CMAS); ECPA, Les Editions du centre de pschologie appliquée, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Turgeon, L.; Chartrand, É. Reliability and Validity of the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale in a French-Canadian Sample. Psychological assessment 2003, 15, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannetzel, L.; Zebdi, R. La R-CMAS Échelle d’anxiété Manifeste Pour Enfants-Révisée. ANAE, Approch. neuropsychol. apprentiss. enfant 2011, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- d’Acremont, M.; Van der Linden, M. How Is Impulsivity Related to Depression in Adolescence? Evidence from a French Validation of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. Journal of adolescence 2007, 30, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartwright-Hatton, S.; Mather, A.; Illingworth, V.; Brocki, J.; Harrington, R.; Wells, A. Development and Preliminary Validation of the Meta-Cognitions Questionnaire—Adolescent Version. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 2004, 18, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeshaft, Y.L.; Lecerf, T.; Morosan, L.; Badoud, D.M.; Debbané, M. Validation of the French Version of the « Meta-Cognition Questionnaire » for Adolescents (MCQ-Af): Evolution of Metacognitive Beliefs with Age and Their Links with Anxiety during Adolescence. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0230171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolters, L.H.; Hogendoorn, S.M.; Oudega, M.; Vervoort, L.; de Haan, E.; Prins, P.J.M.; Boer, F. Psychometric Properties of the Dutch Version of the Meta-Cognitions Questionnaire-Adolescent Version (MCQ-A) in Non-Clinical Adolescents and Adolescents with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 2012, 26, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gioia, G.A.; Isquith, P.K.; Guy, S.C.; Kenworthy, L. Test Review Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function. Child Neuropsychology 2000a, 6, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Fournet, N.; Le Gall, D.; Roulin, J.-L. BRIEF: Inventaire d’évaluation Comportementale Des Fonctions Exécutives, Adaptation Française. Paris: Hogrefe France Editions 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fournet, N.; Roulin, J.-L.; Monnier, C.; Atzeni, T.; Cosnefroy, O.; Le Gall, D.; Roy, A. Multigroup Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Structural Invariance with Age of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF)—French Version. Child Neuropsychology 2015, 21, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cécillon, F.-X.; Mermillod, M.; Shankland, R. Anxiety, Emotional Regulation, Executives Functions and School Achievement 2022, OSF. [CrossRef]

- [Datasets] Cécillon, F.-X. Correlational Study in French Adolescents 2023, Mendeley Data, V3, 2023.

- Heeren, A.; McNally, R.J. An Integrative Network Approach to Social Anxiety Disorder: The Complex Dynamic Interplay among Attentional Bias for Threat, Attentional Control, and Symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 2016, 42, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Borsboom, D.; Fried, E.I. Estimating Psychological Networks and Their Accuracy: A Tutorial Paper. Behav Res 2018, 50, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Cramer, A.O.; Waldorp, L.J.; Schmittmann, V.D.; Borsboom, D. Qgraph: Network Visualizations of Relationships in Psychometric Data. Journal of statistical software 2012, 48, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruchterman, T.M.J.; Reingold, E.M. Graph Drawing by Force-directed Placement. Softw Pract Exp 1991, 21, 1129–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.R.; Wermuth, N. Linear Dependencies Represented by Chain Graphs. Statistical science 1993, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Fried, E.I. A Tutorial on Regularized Partial Correlation Networks. Psychological methods 2018, 23, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cécillon, F.-X.; Mermillod, M.; Leys, C.; Bastin, H.; Lachaux, J.-P.; Shankland, R. The Reflective Mind of the Anxious in Action: Metacognitive Beliefs and Maladaptive Emotional Regulation Strategies ConStrain Working Memory Efficacity. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. (Submitted).

- Owens, M.; Stevenson, J.; Norgate, R.; Hadwin, J.A. Processing Efficiency Theory in Children: Working Memory as a Mediator between Trait Anxiety and Academic Performance. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping 2008, 21, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronen, E.T.; Vuontela, V.; Steenari, M.-R.; Salmi, J.; Carlson, S. Working Memory, Psychiatric Symptoms, and Academic Performance at School. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 2005, 83, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, M.; Stevenson, J.; Hadwin, J.A.; Norgate, R. Anxiety and Depression in Academic Performance: An Exploration of the Mediating Factors of Worry and Working Memory. School Psychology International 2012, 33, 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, S.V.; Lonigan, C.J. Trait Anxiety and Adolescent’s Academic Achievement: The Role of Executive Function. Learning and Individual Differences 2021, 85, 101941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnefski, N.; Legerstee, J.; Kraaij, V.; van Den Kommer, T.; Teerds, J.A.N. Cognitive Coping Strategies and Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: A Comparison between Adolescents and Adults. Journal of adolescence 2002, 25, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onken, L.S.; Carroll, K.M.; Shoham, V.; Cuthbert, B.N.; Riddle, M. Reenvisioning Clinical Science: Unifying the Discipline to Improve the Public Health. Clinical Psychological Science 2014, 2, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, A.; MacLeod, C. Cognitive Vulnerability to Emotional Disorders. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 1, 167–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkovec, T.D. The Nature, Functions, and Origins of Worry. In Worrying: Perspectives on theory, assessment and treatment; Wiley series in clinical psychology; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, England, 1994; pp. 5–33. ISBN 978-0-471-94114-9. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod, C.; Mathews, A.; Tata, P. Attentional Bias in Emotional Disorders. Journal of abnormal psychology 1986, 95, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacow, T.L.; Pincus, D.B.; Ehrenreich, J.T.; Brody, L.R. The Metacognitions Questionnaire for Children: Development and Validation in a Clinical Sample of Children and Adolescents with Anxiety Disorders. Journal of anxiety disorders 2009, 23, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedetto, L.; Di Blasi, D.; Pacicca, P. Worry and Meta-Cognitive Beliefs in Childhood Anxiety Disorders. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology 2013, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irak, P.M. Standardization of Turkish Form of Metacognition Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents: The Relationships with Anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms. Turk Psikiyatri Dergisi 2012, 23, 46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Campbell, B.; Curran, M.; Inkpen, R.; Katsikitis, M.; Kannis-Dymand, L. A Preliminary Evaluation of Metacognitive Beliefs in High Functioning Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Advances in Autism 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.G.; Solem, S.; Wells, A. The Metacognitions Questionnaire and Its Derivatives in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Psychometric Properties. Frontiers in psychology 2019, 10, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spada, M.M.; Mohiyeddini, C.; Wells, A. Measuring Metacognitions Associated with Emotional Distress: Factor Structure and Predictive Validity of the Metacognitions Questionnaire 30. Personality and Individual Differences 2008, 45, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhu, C.; So, S.H.W. Dysfunctional Metacognition across Psychopathologies: A Meta-Analytic Review. Eur. psychiatr. 2017, 45, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, C.; Steketee, G.; Ghisi, M.; Chiri, L.R.; Franceschini, S. Metacognitive Beliefs and Strategies Predict Worry, Obsessive–Compulsive Symptoms and Coping Styles: A Preliminary Prospective Study on an Italian Non-Clinical Sample. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 2007, 14, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, W.E.; Tournaki, N.; Blackman, S.; Zilinski, C. Executive Functioning Predicts Academic Achievement in Middle School: A Four-Year Longitudinal Study. The Journal of Educational Research 2016, 109, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, A. Associations Between Emotional Regulation, Risk Taking, and College Adaptation. Undergraduate Honors Theses 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cerolini, S.; Zagaria, A.; Vacca, M.; Spinhoven, P.; Violani, C.; Lombardo, C. Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire—Short: Reliability, Validity, and Measurement Invariance of the Italian Version. Behavioral Sciences 2022, 12, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirin, S.R. Socioeconomic Status and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analytic Review of Research. Review of Educational Research 2005, 75, 417–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.R. The Relation between Socioeconomic Status and Academic Achievement. Psychological Bulletin 1982, 91, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cécillon, F.-X.; Mermillod, M.; Lachaux, J.-P.; Bastin, H.; Shankland, R. Assessing the Effectiveness of Mindful’Up and ADOLE Programs on Academic Success-Related Variables: A Mixed-Methods Study. J. Sch. Psychol. (Submitted).

- McRae, K.; Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation. Emotion 2020, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cécillon, F.-X.; Mermillod, M.; Lachaux, J.-P.; Lutz, A.; Shankland, R. Mindfulness et Apprentissage. In Enseigner et apprendre: concilier neurosciences et expérience; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, S.; Ding, D. The Efficacy of Group-Based Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Psychological Capital and School Engagement: A Pilot Study among Chinese Adolescents. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 2020, 16, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, G.; Meyer, E.; Grabé, M.; Meriau, V.; Cuadrado, J.; Poujade, S.H.; Garcia, M.; Salla, J. Effets de La «Mindfulness» Sur l’anxiété, Le Bien-Être et Les Aptitudes de Pleine Conscience Chez Des Élèves Scolarisés Du CE2 Au CM2. Annales Médico-psychologiques, revue psychiatrique 2019, 177, 981–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berggren, N.; Derakshan, N. Attentional Control Deficits in Trait Anxiety: Why You See Them and Why You Don’t. Biological psychology 2013, 92, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, H.; Munro, J.; Orlov, N.; Morgenroth, E.; Moser, J.; Eysenck, M.W.; Allen, P. Worry Is Associated with Inefficient Functional Activity and Connectivity in Prefrontal and Cingulate Cortices during Emotional Interference. Brain and Behavior 2018, 8, e01137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, M.-T.; Lu, H.; Lin, C.-I.; Sun, T.-H.; Chen, Y.-R.; Cheng, C.-H. Effects of Trait Anxiety on Error Processing and Post-Error Adjustments: An Event-Related Potential Study With Stop-Signal Task. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 4th | 5th * | 6th | 7th * | 8th ** | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 15.750 | 16.500 | 15.722 | 15.455 | 14.627 | 14.747 | 14.679 | 12.950 | 14.727 |

| SD | 1.500 | 3.162 | 1.973 | 1.990 | 2.611 | 2.264 | 2.524 | 2.712 | 2.190 |

| n | 4 | 5 | 107 | 67 | 32 | 27 | 17 | 12 | 17 |

| DYS Troubles | HIP | Anxiety disorders | Multiple diagnoses | ADHD | ASD | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 33 (11.30) | 29 (9.93) | 7 (2.39) | 10 (3.42) | 3 (1.02) | 1 (.34) | 83 (100) |

| Variable | n | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. School average | 272 | 15.26 | 2.25 | — | |||||

| 2. Trait Anxiety | 275 | 11.24 | 6.38 | -.184*** | — | ||||

| 3. ERS Maladaptive | 275 | 36.45 | 9.79 | -.040 | .570*** | — | |||

| 4. ERS Adaptive | 275 | 53.53 | 15.67 | .123* | -.087 | .083 | — | ||

| 5. Metacognitive beliefs | 275 | 59.99 | 11.15 | -.124* | .586*** | .495*** | .016 | — | |

| 6. Executive functioning | 275 | 119.85 | 25.49 | -.359*** | .468*** | .274*** | -.161** | .314*** | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).