Submitted:

28 December 2023

Posted:

28 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

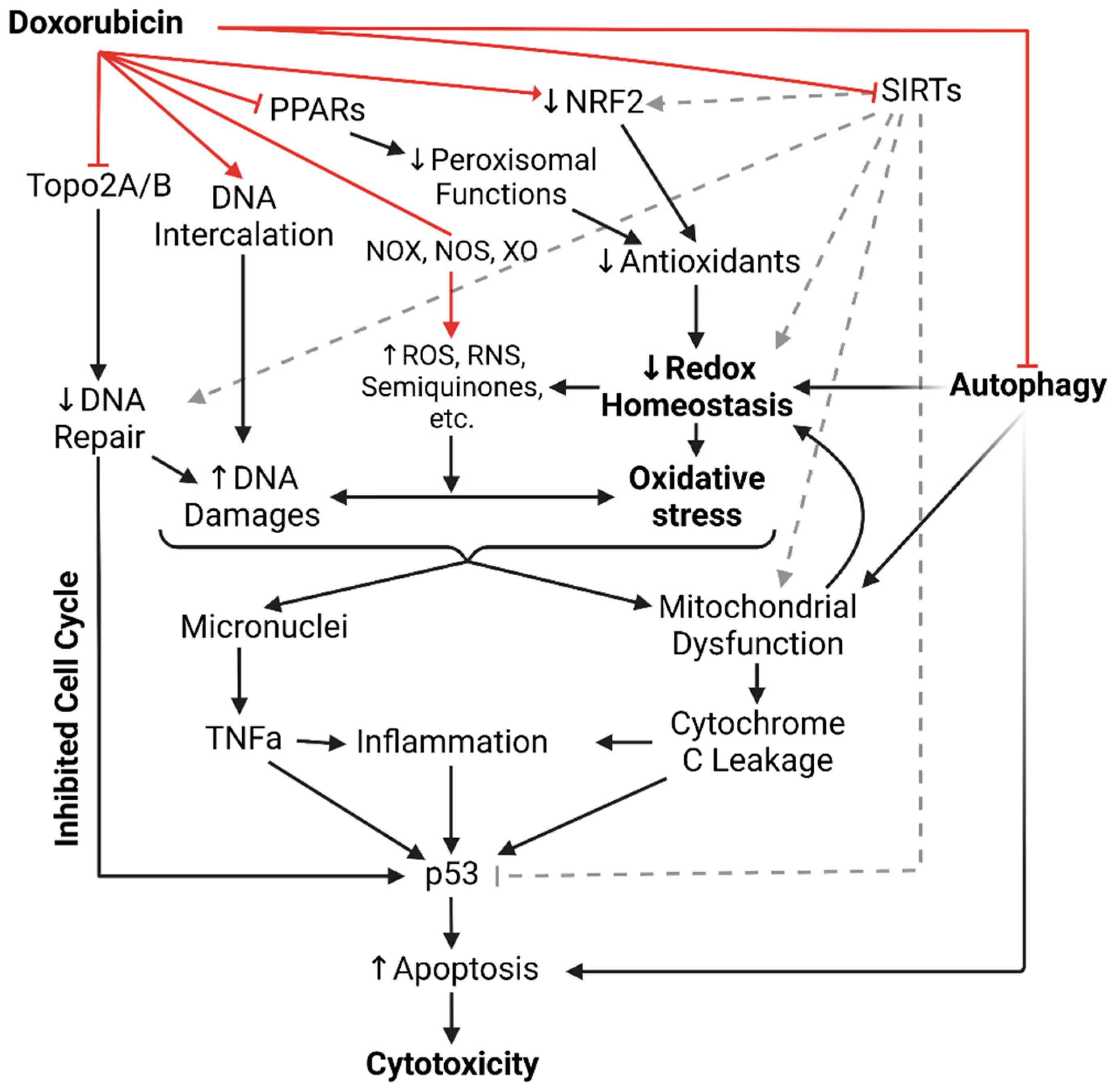

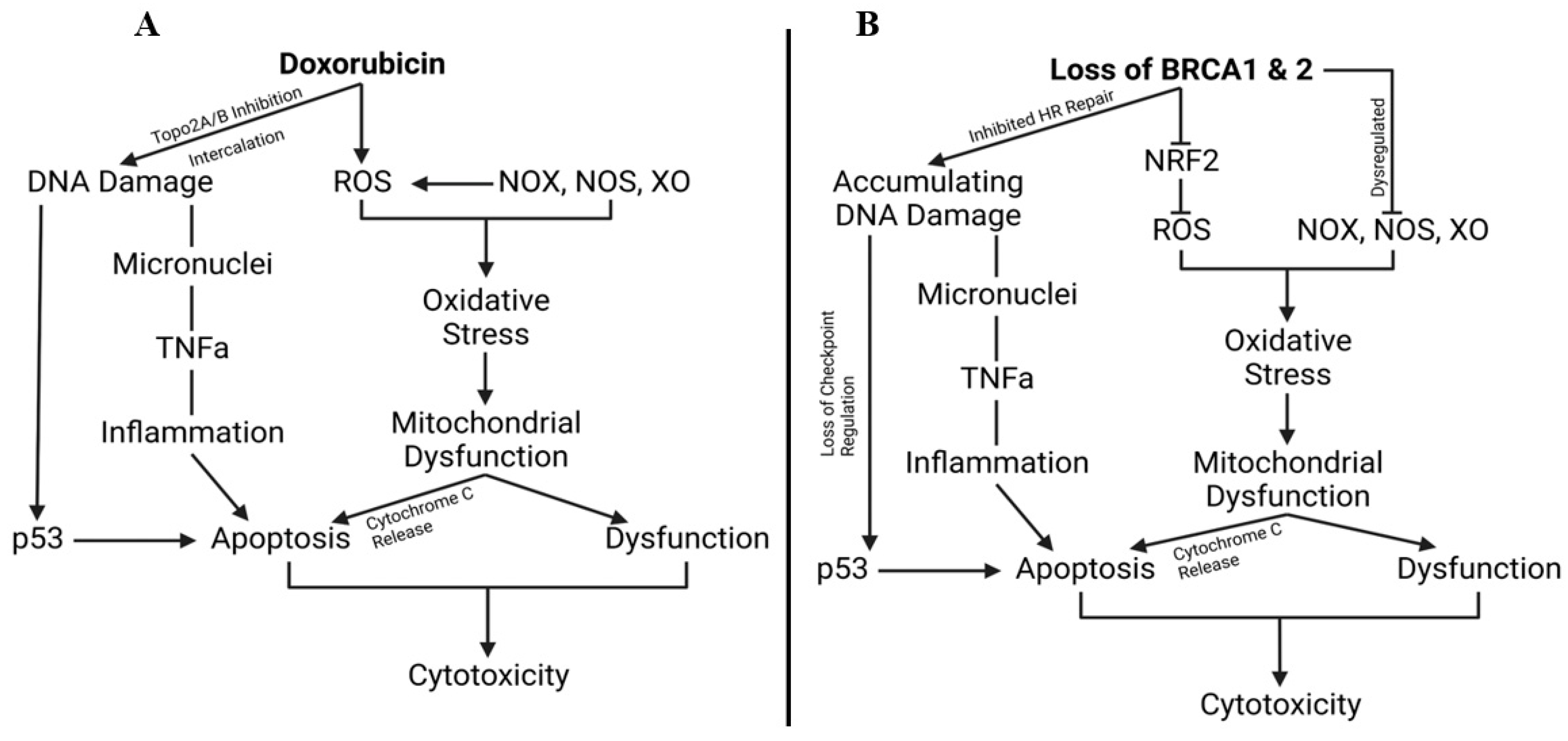

Dox Induced Cardiotoxicity

Intercalation of DNA and Topoisomerase II inhibition:

NADPH Oxidases, Nitric Oxide Synthases, and Xanthine Oxidase:

Antioxidants in Dox-induced Cardiotoxicity:

Peroxisomes in Dox-induced Cardiotoxicity:

Sirtuins Deacetylation in Dox-induced Cardiotoxicity:

Dox Impairs Autophagy:

Dox induces Sarcoplasm Leakage:

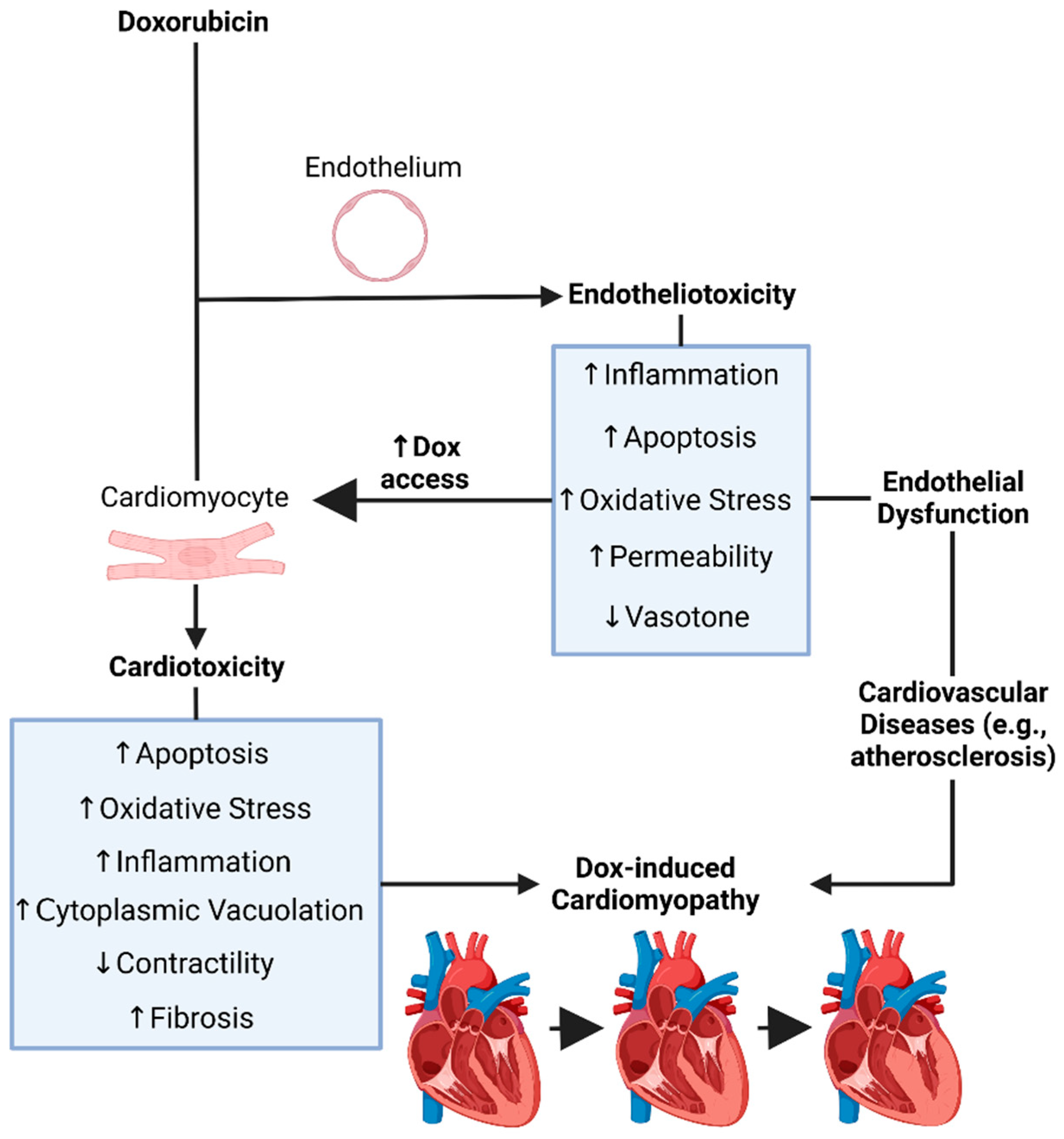

Dox-induced endotheliotoxicity (DIE):

The Endothelium:

Endothelial Dysfunction:

Dox-induced Endothelial Dysfunction, Endotheliotoxicity, and Cardiotoxicity:

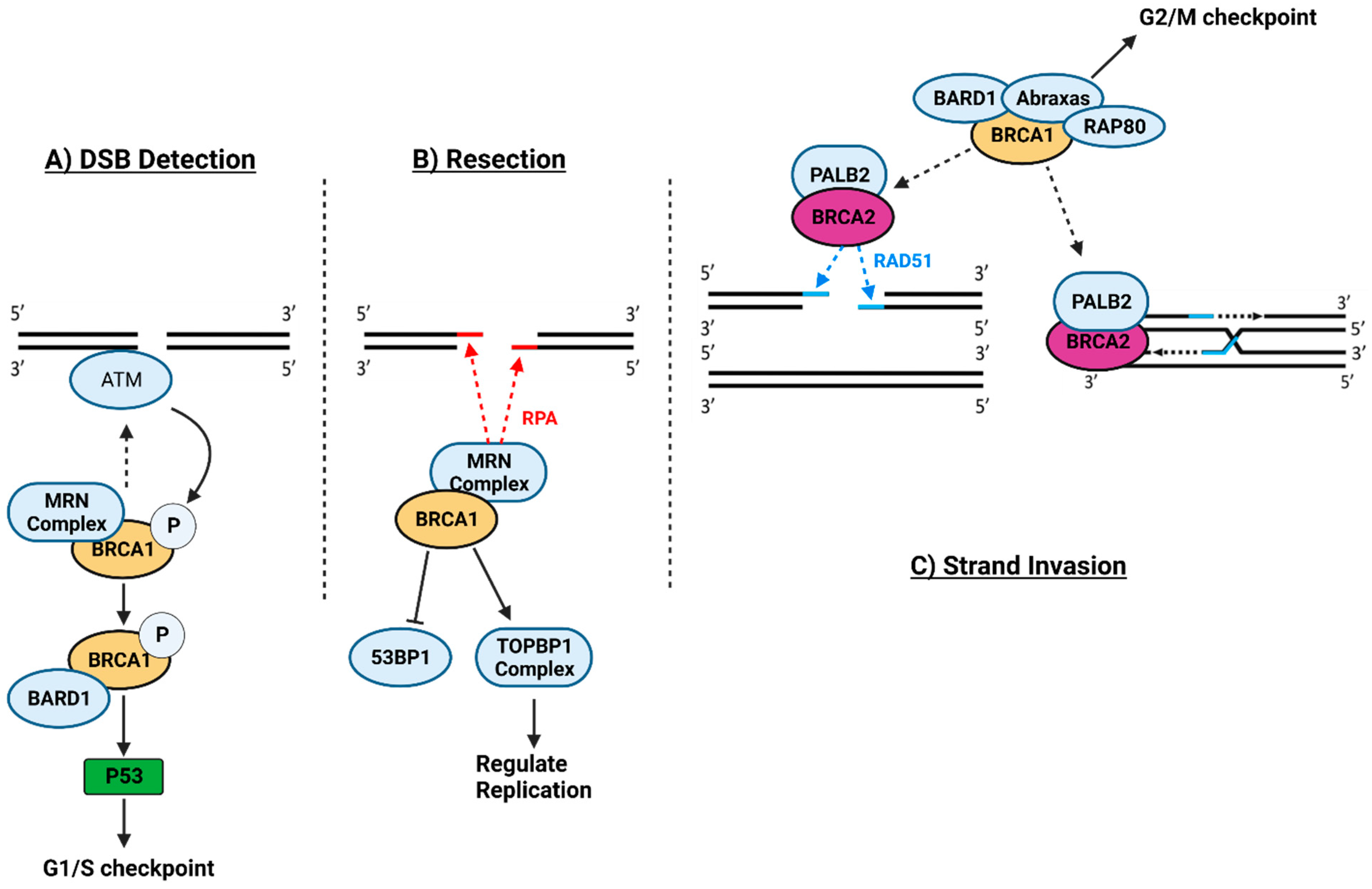

Breast Cancer Gene 1 & 2:

Breast Cancer Gene, Doxorubicin and Cardiovascular Implications and Prospects:

Final remarks

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sritharan, S.; Sivalingam, N. A Comprehensive Review on Time-Tested Anticancer Drug Doxorubicin. Life Sci 2021, 278, 119527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletto, R.E.; Ofner, C.M. Cytotoxic Mechanisms of Doxorubicin at Clinically Relevant Concentrations in Breast Cancer Cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2022, 89, 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, D.L.; Rastatter, J.C.; Colombo, T.; Long, M.E. Doxorubicin Pharmacokinetics: Macromolecule Binding, Metabolism, and Excretion in the Context of a Physiologic Model. J Pharm Sci 2002, 91, 1488–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speth, P.A.; van Hoesel, Q.G.; Haanen, C. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Doxorubicin. Clin Pharmacokinet 1988, 15, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, N.A.; Twelves, C.J.; Gillies, H.; James, C.A.; Harper, P.G.; Rubens, R.D. Gender Affects Doxorubicin Pharmacokinetics in Patients with Normal Liver Biochemistry. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1995, 36, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacar, O.; Sriamornsak, P.; Dass, C.R. Doxorubicin: An Update on Anticancer Molecular Action, Toxicity and Novel Drug Delivery Systems. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2013, 65, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, C.F.; Oshiro, C.; Marsh, S.; Hernandez-Boussard, T.; McLeod, H.; Klein, T.E.; Altman, R.B. Doxorubicin Pathways: Pharmacodynamics and Adverse Effects. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2011, 21, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, C.-Y.; Guo, Z.; Song, P.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, Y.-P.; Teng, T.; Yan, L.; Tang, Q.-Z. Underlying the Mechanisms of Doxorubicin-Induced Acute Cardiotoxicity: Oxidative Stress and Cell Death. Int J Biol Sci 2022, 18, 760–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minotti, G.; Recalcati, S.; Mordente, A.; Liberi, G.; Calafiore, A.M.; Mancuso, C.; Preziosi, P.; Cairo, G. The Secondary Alcohol Metabolite of Doxorubicin Irreversibly Inactivates Aconitase/Iron Regulatory Protein-1 in Cytosolic Fractions from Human Myocardium. FASEB J 1998, 12, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheibani, M.; Azizi, Y.; Shayan, M.; Nezamoleslami, S.; Eslami, F.; Farjoo, M.H.; Dehpour, A.R. Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity: An Overview on Pre-Clinical Therapeutic Approaches. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2022, 22, 292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, M.M.; Khedr, M.M.; Morsy, M.H.; Badae, N.M.; Elatrebi, S. A Comparative Study of the Cardioprotective Effect of Metformin, Sitagliptin and Dapagliflozin on Isoprenaline Induced Myocardial Infarction in Non-Diabetic Rats. Bulletin of the National Research Centre 2022, 46, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloss, K.; Hamar, P. Recent Preclinical and Clinical Progress in Liposomal Doxorubicin. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeger, C.W.; Turissini, C.; Asnani, A. Doxorubicin Cardiotoxicity: Pathophysiology Updates. Curr Treat Options Cardio Med 2020, 22, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, C.; Santos, R.X.; Cardoso, S.; Correia, S.; Oliveira, P.J.; Santos, M.S.; Moreira, P.I. Doxorubicin: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly Effect. Curr Med Chem 2009, 16, 3267–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Sarkar, S.; Scott, L.; Danelisen, I.; Trush, M.A.; Jia, Z.; Li, Y.R. Doxorubicin Redox Biology: Redox Cycling, Topoisomerase Inhibition, and Oxidative Stress. React Oxyg Species (Apex) 2016, 1, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agudelo, D.; Bourassa, P.; Bérubé, G.; Tajmir-Riahi, H.-A. Intercalation of Antitumor Drug Doxorubicin and Its Analogue by DNA Duplex: Structural Features and Biological Implications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2014, 66, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, X.; Bawa-Khalfe, T.; Lu, L.-S.; Lyu, Y.L.; Liu, L.F.; Yeh, E.T.H. Identification of the Molecular Basis of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Nat Med 2012, 18, 1639–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeland, K. Cell Cycle Regulation: P53-P21-RB Signaling. Cell Death Differ 2022, 29, 946–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polager, S.; Ginsberg, D. P53 and E2f: Partners in Life and Death. Nat Rev Cancer 2009, 9, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrey, B.J.; Kelly, G.L.; Janic, A.; Herold, M.J.; Strasser, A. How Does P53 Induce Apoptosis and How Does This Relate to P53-Mediated Tumour Suppression? Cell Death Differ 2018, 25, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Soonpaa, M.H.; Chen, H.; Shen, W.; Payne, R.M.; Liechty, E.A.; Caldwell, R.L.; Shou, W.; Field, L.J. Acute Doxorubicin Cardiotoxicity Is Associated with P53-Induced Inhibition of the Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Pathway. Circulation 2009, 119, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, P.-Y.; Long, N.A.; Zhuang, J.; Springer, D.A.; Zou, J.; Lin, Y.; Bleck, C.K.E.; Park, J.-H.; Kang, J.-G.; et al. P53 Prevents Doxorubicin Cardiotoxicity Independently of Its Prototypical Tumor Suppressor Activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 19626–19634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, W.; Shou, W.; Field, L.J. P53 Inhibition Exacerbates Late-Stage Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity. Cardiovascular Research 2014, 103, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sin, T.K.; Tam, B.T.; Yung, B.Y.; Yip, S.P.; Chan, L.W.; Wong, C.S.; Ying, M.; Rudd, J.A.; Siu, P.M. Resveratrol Protects against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Aged Hearts through the SIRT1-USP7 Axis. J Physiol 2015, 593, 1887–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Lu, Y.-B.; Liang, S.-T.; Zhang, Q.-J.; Xu, J.; She, Z.-G.; Zhang, Z.-Q.; Yang, R.-F.; Mao, B.-B.; Xu, Z.; et al. SIRT1 Mediates the Protective Function of Nkx2.5 during Stress in Cardiomyocytes. Basic Res Cardiol 2013, 108, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Lan, J.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Tong, M.; Fu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, H.; et al. Sirt6 Protects Cardiomyocytes against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Inhibiting P53/Fas-Dependent Cell Death and Augmenting Endogenous Antioxidant Defense Mechanisms. Cell Biol Toxicol 2023, 39, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, Y.S.; Kuno, A.; Hosoda, R.; Horio, Y. Regulation of FOXOs and P53 by SIRT1 Modulators under Oxidative Stress. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e73875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Tang, Y.; Lu, G.; Gu, J. P53 at the Crossroads between Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity and Resistance: A Nutritional Balancing Act. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Gao, M.; Jiang, W.; Qin, Y.; Gong, G. Mitochondrial Dynamics in Adult Cardiomyocytes and Heart Diseases. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begum, R.; Thota, S.; Abdulkadir, A.; Kaur, G.; Bagam, P.; Batra, S. NADPH Oxidase Family Proteins: Signaling Dynamics to Disease Management. Cell Mol Immunol 2022, 19, 660–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Förstermann, U.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric Oxide Synthases: Regulation and Function. Eur Heart J 2012, 33, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.Y.; Baek, B.S.; Song, S.H.; Kim, M.S.; Huh, J.I.; Shim, K.H.; Kim, K.W.; Lee, K.H. Xanthine Dehydrogenase/Xanthine Oxidase and Oxidative Stress. Age (Omaha) 1997, 20, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafson, D.L.; Swanson, J.D.; Pritsos, C.A. Role of Xanthine Oxidase in the Potentiation of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Mitomycin C. Cancer Commun 1991, 3, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Febuxostat Ameliorates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Rats - PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26036690/ (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Kondo, M.; Imanishi, M.; Fukushima, K.; Ikuto, R.; Murai, Y.; Horinouchi, Y.; Izawa-Ishizawa, Y.; Goda, M.; Zamami, Y.; Takechi, K.; et al. Xanthine Oxidase Inhibition by Febuxostat in Macrophages Suppresses Angiotensin II-Induced Aortic Fibrosis. Am J Hypertens 2019, 32, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappetta, D.; De Angelis, A.; Sapio, L.; Prezioso, L.; Illiano, M.; Quaini, F.; Rossi, F.; Berrino, L.; Naviglio, S.; Urbanek, K. Oxidative Stress and Cellular Response to Doxorubicin: A Common Factor in the Complex Milieu of Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017, 1521020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, C.; Xin, J.; Huang, W.; Zhang, D.; Yan, X.; Li, R.; Li, H.; Lan, J.; Lin, L.; Li, L.; et al. Irisin Protects against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Improving AMPK-Nrf2 Dependent Mitochondrial Fusion and Strengthening Endogenous Anti-Oxidant Defense Mechanisms. Toxicology 2023, 494, 153597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, N.; Wei, W.-Y.; Li, L.-L.; Ma, Z.-G.; Tang, Q.-Z. Osteocrin Attenuates Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Apoptosis, and Cardiac Dysfunction in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Clin Transl Med 2020, 10, e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassègue, B.; San Martín, A.; Griendling, K.K. Biochemistry, Physiology, and Pathophysiology of NADPH Oxidases in the Cardiovascular System. Circulation Research 2012, 110, 1364–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriquez-Olguin, C.; Meneses-Valdes, R.; Raun, S.H.; Gallero, S.; Knudsen, J.R.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Sylow, L.; Jaimovich, E.; Jensen, T.E. NOX2 Deficiency Exacerbates Diet-Induced Obesity and Impairs Molecular Training Adaptations in Skeletal Muscle. Redox Biology 2023, 65, 102842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efentakis, P.; Varela, A.; Chavdoula, E.; Sigala, F.; Sanoudou, D.; Tenta, R.; Gioti, K.; Kostomitsopoulos, N.; Papapetropoulos, A.; Tasouli, A.; et al. Levosimendan Prevents Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Time- and Dose-Dependent Manner: Implications for Inotropy. Cardiovasc Res 2020, 116, 576–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akolkar, G.; Bagchi, A.K.; Ayyappan, P.; Jassal, D.S.; Singal, P.K. Doxorubicin-Induced Nitrosative Stress Is Mitigated by Vitamin C via the Modulation of Nitric Oxide Synthases. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2017, 312, C418–C427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yao, L.; Wu, X.; Guo, Q.; Sun, S.; Li, J.; Shi, G.; Caldwell, R.B.; Caldwell, R.W.; Chen, Y. Protection against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity through Modulating iNOS/ARG 2 Balance by Electroacupuncture at PC6. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2021, 2021, e6628957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangweni, N.F.; van Vuuren, D.; Mabasa, L.; Gabuza, K.; Huisamen, B.; Naidoo, S.; Barry, R.; Johnson, R. Prevention of Anthracycline-Induced Cardiotoxicity: The Good and Bad of Current and Alternative Therapies. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, N.; Garcia, T.; Aniqa, M.; Ali, S.; Ally, A.; Nauli, S. Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase (eNOS) and the Cardiovascular System: In Physiology and in Disease States. Am J Biomed Sci Res 2022, 15, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neilan, T.G.; Blake, S.L.; Ichinose, F.; Raher, M.J.; Buys, E.S.; Jassal, D.S.; Furutani, E.; Perez-Sanz, T.M.; Graveline, A.; Janssens, S.P.; et al. Disruption of Nitric Oxide Synthase 3 Protects against the Cardiac Injury, Dysfunction, and Mortality Induced by Doxorubicin. Circulation 2007, 116, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Wang, L.; Qiao, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Li, H.; Chen, S.; Yin, D.; Huang, Q.; He, M. Doxorubicin Induces Endotheliotoxicity and Mitochondrial Dysfunction via ROS/eNOS/NO Pathway. Front Pharmacol 2020, 10, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeglinski, M.; Premecz, S.; Lerner, J.; Wtorek, P.; Dasilva, M.; Hasanally, D.; Chaudhary, R.; Sharma, A.; Thliveris, J.; Ravandi, A.; et al. Congenital Absence of Nitric Oxide Synthase 3 Potentiates Cardiac Dysfunction and Reduces Survival in Doxorubicin- and Trastuzumab-Mediated Cardiomyopathy. Can J Cardiol 2014, 30, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, W.C.; Recchia, F.A.; Lopaschuk, G.D. Myocardial Substrate Metabolism in the Normal and Failing Heart. Physiol. Rev. 2005, 85, 1093–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzoog, B.A.; Vlasova, T.I. Myocardiocyte Autophagy in the Context of Myocardiocytes Regeneration: A Potential Novel Therapeutic Strategy. Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics 2022, 23, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, A.I.; Amaro-Leal, Â.; Machado, F.; Rocha, I.; Geraldes, V. Doxorubicin Dose-Dependent Impact on Physiological Balance—A Holistic Approach in a Rat Model. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallons, M.; Schepkens, C.; Dupuis, A.; Tagliatti, V.; Colet, J.-M. New Insights About Doxorubicin-Induced Toxicity to Cardiomyoblast-Derived H9C2 Cells and Dexrazoxane Cytoprotective Effect: Contribution of In Vitro 1H-NMR Metabonomics. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, X.; Van Der Zanden, S.Y.; Wander, D.P.A.; Borràs, D.M.; Song, J.-Y.; Li, X.; Van Duikeren, S.; Van Gils, N.; Rutten, A.; Van Herwaarden, T.; et al. Uncoupling DNA Damage from Chromatin Damage to Detoxify Doxorubicin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 15182–15192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashyap, P.; Shikha, D.; Thakur, M.; Aneja, A. Functionality of Apigenin as a Potent Antioxidant with Emphasis on Bioavailability, Metabolism, Action Mechanism and in Vitro and in Vivo Studies: A Review. J Food Biochem 2022, 46, e13950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, C.-J.; Yu, X.-J.; Sun, Y.-J.; Li, H.-B.; Su, Q.; Bai, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, K.-L.; Qi, J.; Zhou, S.-W.; et al. Irisin Lowers Blood Pressure by Activating the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in the Hypothalamic Paraventricular Nucleus of Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2020, 394, 114953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, A.; Dean, J.M.; Lodhi, I.J. Peroxisomes as Cellular Adaptors to Metabolic and Environmental Stress. Trends Cell Biol 2021, 31, 656–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schedin, S.; Sindelar, P.J.; Pentchev, P.; Brunk, U.; Dallner, G. Peroxisomal Impairment in Niemann-Pick Type C Disease. J Biol Chem 1997, 272, 6245–6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawałek, A.; Lefevre, S.D.; Veenhuis, M.; Klei, I.J. van der Peroxisomal Catalase Deficiency Modulates Yeast Lifespan Depending on Growth Conditions. Aging 2013, 5, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.-H.; Lian, X.-D.; Lee, S.-J.; Li, W.-L.; Sun, H.-N.; Jin, M.-H.; Kwon, T. Regulatory Effect of Peroxiredoxin 1 (PRDX1) on Doxorubicin-Induced Apoptosis in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Applied Biological Chemistry 2022, 65, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Gong, Y.; Hu, Y.; You, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Z.; Tang, C. Peroxiredoxin-1 Overexpression Attenuates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress and Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020, 2405135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanders, R.J.A.; Waterham, H.R. Peroxisomal Disorders: The Single Peroxisomal Enzyme Deficiencies. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2006, 1763, 1707–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Chiang, N.; Dalli, J.; Levy, B.D. Lipid Mediators in the Resolution of Inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2014, 7, a016311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endres, S.; Ghorbani, R.; Kelley, V.E.; Georgilis, K.; Lonnemann, G.; van der Meer, J.W.; Cannon, J.G.; Rogers, T.S.; Klempner, M.S.; Weber, P.C. The Effect of Dietary Supplementation with N-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on the Synthesis of Interleukin-1 and Tumor Necrosis Factor by Mononuclear Cells. N Engl J Med 1989, 320, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, J.K.; Hashimoto, T. Peroxisomal Beta-Oxidation and Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha: An Adaptive Metabolic System. Annu Rev Nutr 2001, 21, 193–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, S. Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptors and Lipoprotein Metabolism. PPAR Res 2008, 2008, 132960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, S.; Tirupathi Pichiah, P.B.; Achiraman, S. Doxorubicin Treatment Inhibits PPARγ and May Induce Lipotoxicity by Mimicking a Type 2 Diabetes-like Condition in Rodent Models. FEBS Letters 2013, 587, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Liu, R.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xian, J.; Huang, J.; Qiu, Z.; Lin, X.; Zhang, M.; Chen, H.; et al. Reactivation of PPARα Alleviates Myocardial Lipid Accumulation and Cardiac Dysfunction by Improving Fatty Acid β-Oxidation in Dsg2-Deficient Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Acta Pharm Sin B 2023, 13, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Fang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, D.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y. PPARα Ameliorates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Reducing Mitochondria-Dependent Apoptosis via Regulating MEOX1. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 528267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-P.; Yin, W.-H.; Chen, J.-S.; Huang, P.-H.; Chen, J.-W.; Lin, S.-J. Fenofibrate Attenuates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction in Mice via Activating the eNOS/EPC Pathway. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, B.J.; Verdin, E. Sirtuins: Sir2-Related NAD-Dependent Protein Deacetylases. Genome Biol 2004, 5, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushima, S.; Sadoshima, J. The Role of Sirtuins in Cardiac Disease. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2015, 309, H1375–H1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministrini, S.; Puspitasari, Y.M.; Beer, G.; Liberale, L.; Montecucco, F.; Camici, G.G. Sirtuin 1 in Endothelial Dysfunction and Cardiovascular Aging. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murugasamy, K.; Munjal, A.; Sundaresan, N.R. Emerging Roles of SIRT3 in Cardiac Metabolism. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 850340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiyang, X.; Deng, W.; Qizhu, T. Sirtuin 6: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Cardiovascular Diseases. Pharmacol Res 2021, 163, 105214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamura, S.; Izumiya, Y.; Araki, S.; Nakamura, T.; Kimura, Y.; Hanatani, S.; Yamada, T.; Ishida, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Onoue, Y.; et al. Cardiomyocyte Sirt (Sirtuin) 7 Ameliorates Stress-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy by Interacting With and Deacetylating GATA4. Hypertension 2020, 75, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.A.; Hirschey, M.D. Mitochondrial Protein Acetylation Regulates Metabolism. Essays Biochem 2012, 52, 10–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, L.R.; Imai, S. The Dynamic Regulation of NAD Metabolism in Mitochondria. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2012, 23, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bharathi, S.S.; Beck, M.E.; Goetzman, E.S. The Fatty Acid Oxidation Enzyme Long-Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Can Be a Source of Mitochondrial Hydrogen Peroxide. Redox Biol 2019, 26, 101253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parodi-Rullán, R.M.; Chapa-Dubocq, X.R.; Javadov, S. Acetylation of Mitochondrial Proteins in the Heart: The Role of SIRT3. Front Physiol 2018, 9, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikalova, A.E.; Itani, H.A.; Nazarewicz, R.R.; McMaster, W.G.; Flynn, C.R.; Uzhachenko, R.; Fessel, J.P.; Gamboa, J.L.; Harrison, D.G.; Dikalov, S.I. Sirt3 Impairment and SOD2 Hyperacetylation in Vascular Oxidative Stress and Hypertension. Circ Res 2017, 121, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, N.R.; Samant, S.A.; Pillai, V.B.; Rajamohan, S.B.; Gupta, M.P. SIRT3 Is a Stress-Responsive Deacetylase in Cardiomyocytes That Protects Cells from Stress-Mediated Cell Death by Deacetylation of Ku70. Mol Cell Biol 2008, 28, 6384–6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Cantrell, A.C.; Chen, J.-X.; Gu, W.; Zeng, H. SIRT3 Deficiency Enhances Ferroptosis and Promotes Cardiac Fibrosis via P53 Acetylation. Cells 2023, 12, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lu, G.; Lu, J.; Wang, P.; Zhang, X.; Zou, Y.; Liu, P. SZC-6, a Small-Molecule Activator of SIRT3, Attenuates Cardiac Hypertrophy in Mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2023, 44, 546–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ding, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, Z.; Luo, W.; Liu, P.; Li, Z. SIRT3 Improved Peroxisomes-Mitochondria Interplay and Prevented Cardiac Hypertrophy via Preserving PEX5 Expression. Redox Biology 2023, 62, 102652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, G.; Wang, X.; Tan, N.; Cao, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Sun, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, W.; et al. Mechanisms and Drug Intervention for Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity Based on Mitochondrial Bioenergetics. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2022, 2022, e7176282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Shen, T.; Lian, J.; Deng, K.; Qu, C.; Li, E.; Li, G.; Ren, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Resveratrol Reduces ROS-Induced Ferroptosis by Activating SIRT3 and Compensating the GSH/GPX4 Pathway. Molecular Medicine 2023, 29, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christidi, E.; Brunham, L.R. Regulated Cell Death Pathways in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; He, X.; Liu, M.; Bai, B.; Tian, C.; Sun, R.; Yu, T.; Chu, X. Role of Acetylation in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Redox Biol 2021, 46, 102089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagasaka, M.; Miyajima, C.; Aoki, H.; Aoyama, M.; Morishita, D.; Inoue, Y.; Hayashi, H. Insights into Regulators of P53 Acetylation. Cells 2022, 11, 3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J. SIRT3 as a Potential Therapeutic Target for Heart Failure. Pharmacological Research 2021, 165, 105432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.-N.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, C.-H.; Omondi, A.M.; Ghosh, A.; Khanra, I.; Chakraborty, M.; Yu, X.-B.; Liang, J. Sirtuins Family as a Target in Endothelial Cell Dysfunction: Implications for Vascular Ageing. Biogerontology 2020, 21, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, F.; Lotfi, P.; Sardiello, M.; Segatori, L. 2-Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin Promotes Transcription Factor EB-Mediated Activation of Autophagy: Implications for Therapy. J Biol Chem 2014, 289, 10211–10222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moruno-Manchon, J.F.; Uzor, N.-E.; Kesler, S.R.; Wefel, J.S.; Townley, D.M.; Nagaraja, A.S.; Pradeep, S.; Mangala, L.S.; Sood, A.K.; Tsvetkov, A.S. Peroxisomes Contribute to Oxidative Stress in Neurons during Doxorubicin-Based Chemotherapy. Mol Cell Neurosci 2018, 86, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, S.; Joseph, J.J.; Nguyen, H.C.; Ehsan, M.; Rasheed, B.; Singh, A.; Qadura, M.; Frisbee, J.C.; Singh, K.K. MicroRNA miR-378-3p Is a Novel Regulator of Endothelial Autophagy and Function. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology Plus 2023, 3, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, S.; Singh, K.K. Epigenetic Regulation of Autophagy in Cardiovascular Pathobiology. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 6544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Cui, T.; Wang, X. The Interplay Between Autophagy and Regulated Necrosis. Antioxid Redox Signal 2023, 38, 550–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.K.; Lovren, F.; Pan, Y.; Quan, A.; Ramadan, A.; Matkar, P.N.; Ehsan, M.; Sandhu, P.; Mantella, L.E.; Gupta, N.; et al. The Essential Autophagy Gene ATG7 Modulates Organ Fibrosis via Regulation of Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. J Biol Chem 2015, 290, 2547–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wei, X.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Jing, J.; Huang, R.; Zhou, T.; Hu, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Doxorubicin Downregulates Autophagy to Promote Apoptosis-Induced Dilated Cardiomyopathy via Regulating the AMPK/mTOR Pathway. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 162, 114691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleini, N.; Kardami, E. Autophagy and Mitophagy in the Context of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 46663–46680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitry, M.A.; Edwards, J.G. Doxorubicin Induced Heart Failure: Phenotype and Molecular Mechanisms. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc 2015, 10, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, R.I.; Bold, A.; Pop, O.T.; Mălăescu, D.G.; Gheorghişor, I.; Mogoantă, L. Histological and Immunohistochemical Changes of the Myocardium in Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2012, 53, 269–275. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, A.D.; Lam, A.; Tham, S.; Dulhunty, A.F.; Beard, N.A. Adverse Effects of Doxorubicin and Its Metabolic Product on Cardiac RyR2 and SERCA2A. Mol Pharmacol 2014, 86, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, P.Y.; Teo, A.; Yeo, T.W. Overview of the Assessment of Endothelial Function in Humans. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020, 7, 542567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, B.; Lincoln, J. The Endocardium and Heart Valves. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2020, 12, a036723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, I.S.; Black, B.L. Development of the Endocardium. Pediatr Cardiol 2010, 31, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewing, J.M.; Saunders, V.; O’Kelly, I.; Wilson, D.I. Defining Cardiac Cell Populations and Relative Cellular Composition of the Early Fetal Human Heart. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0259477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, A.Z.; Chowdhury, B.; Al-Omran, M.; Teoh, H.; Hess, D.A.; Verma, S. Role of Endothelium in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyopathy. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2018, 3, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félétou, M. Multiple Functions of the Endothelial Cells. In The Endothelium: Part 1: Multiple Functions of the Endothelial Cells—Focus on Endothelium-Derived Vasoactive Mediators; Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences, 2011.

- Singh, S.; Nguyen, H.; Michels, D.; Bazinet, H.; Matkar, P.N.; Liu, Z.; Esene, L.; Adam, M.; Bugyei-Twum, A.; Mebrahtu, E.; et al. BReast CAncer Susceptibility Gene 2 Deficiency Exacerbates Oxidized LDL-Induced DNA Damage and Endothelial Apoptosis. Physiol Rep 2020, 8, e14481–e14481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Ji, W.; Yang, H.; Chen, S.; Zhang, W.; Duan, G. Endothelial Activation and Dysfunction in COVID-19: From Basic Mechanisms to Potential Therapeutic Approaches. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020, 5, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.C.; Bu, S.; Nikfarjam, S.; Rasheed, B.; Michels, D.C.R.; Singh, A.; Singh, S.; Marszal, C.; McGuire, J.J.; Feng, Q.; et al. Loss of Fatty Acid Binding Protein 3 Ameliorates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction. J Biol Chem 2023, 299, 102921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.-J.; Wu, Z.-Y.; Nie, X.-W.; Bian, J.-S. Role of Endothelial Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Diseases: The Link Between Inflammation and Hydrogen Sulfide. Front Pharmacol 2020, 10, 1568–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, W.; Wang, L.; Jia, Q.; Shi, F.; Li, K.; Liao, L.; Shi, Y.; Wu, S. The Role of TOP2A in Immunotherapy and Vasculogenic Mimicry in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer and Its Potential Mechanism. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 10906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopfner, K.-P.; Hornung, V. Molecular Mechanisms and Cellular Functions of cGAS–STING Signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovitt, C.J.; Shelper, T.B.; Avery, V.M. Doxorubicin Resistance in Breast Cancer Cells Is Mediated by Extracellular Matrix Proteins. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, P.S.; Jaiswal, A.; Khurana, A.; Bhatti, J.S.; Navik, U. Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity: An Update on the Molecular Mechanism and Novel Therapeutic Strategies for Effective Management. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 139, 111708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Zhu, C.; Lu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y. Ursolic Acid Prevents Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiac Toxicity in Mice through eNOS Activation and Inhibition of eNOS Uncoupling. J Cell Mol Med 2019, 23, 2174–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, Y.; Sun, M.; Silver, M.; Ho, K.K.L.; Marchionni, M.A.; Caggiano, A.O.; Stone, J.R.; Amende, I.; Hampton, T.G.; Morgan, J.P.; et al. Neuregulin-1 Attenuated Doxorubicin-Induced Decrease in Cardiac Troponins. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2009, 297, H1974–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Yang, M.; Duan, C.H.; Su, G.B.; Wang, J.H.; Liu, Y.F.; Zhang, J. Protective Role of Neuregulin-1 toward Doxorubicin-Induced Myocardial Toxicity. Genet Mol Res 2014, 13, 4627–4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, R.S.; Ushio-Fukai, M.; Malik, A.B. NADPH Oxidase-Dependent Signaling in Endothelial Cells: Role in Physiology and Pathophysiology. Antioxid Redox Signal 2009, 11, 791–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daiber, A.; Xia, N.; Steven, S.; Oelze, M.; Hanf, A.; Kröller-Schön, S.; Münzel, T.; Li, H. New Therapeutic Implications of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase (eNOS) Function/Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmesser, U.; Spiekermann, S.; Preuss, C.; Sorrentino, S.; Fischer, D.; Manes, C.; Mueller, M.; Drexler, H. Angiotensin II Induces Endothelial Xanthine Oxidase Activation: Role for Endothelial Dysfunction in Patients with Coronary Disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007, 27, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop-Bailey, D.; Swales, K.E. The Role of PPARs in the Endothelium: Implications for Cancer Therapy. PPAR Res 2008, 2008, 904251–904251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Wang, X.; Sun, X.; Hu, W.; Miao, Q.R. The Role of Histone Protein Acetylation in Regulating Endothelial Function. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, A.W.C.; Li, H.; Xia, N. The Role of Sirtuin1 in Regulating Endothelial Function, Arterial Remodeling and Vascular Aging. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Dong, W. SIRT1-Related Signaling Pathways and Their Association With Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Frontiers in Medicine 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S.; Schäfer, N.; Breitenstein, A.; Besler, C.; Winnik, S.; Lohmann, C.; Heinrich, K.; Brokopp, C.E.; Handschin, C.; Landmesser, U.; et al. SIRT1 Reduces Endothelial Activation without Affecting Vascular Function in ApoE-/- Mice. Aging (Albany NY) 2010, 2, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Yu, S.; Chao, M.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, J.; Lai, H. SIRT4 Suppresses the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB Signaling Pathway and Attenuates HUVEC Injury Induced by oxLDL. Mol Med Rep 2019, 19, 4973–4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, E.; Balestrieri, A.; Anastasio, C.; Maione, M.; Mele, L.; Cautela, D.; Campanile, G.; Balestrieri, M.L.; D’Onofrio, N. SIRT3 Modulates Endothelial Mitochondrial Redox State during Insulin Resistance. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Yao, H.; Caito, S.; Sundar, I.K.; Rahman, I. Redox Regulation of SIRT1 in Inflammation and Cellular Senescence. Free Radic Biol Med 2013, 61, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Fan, X.-F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Gong, Y.-S.; Han, L.-P. SIRT1 Activation Attenuates Cardiac Fibrosis by Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. Biomed Pharmacother 2019, 118, 109227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graziani, S.; Scorrano, L.; Pontarin, G. Transient Exposure of Endothelial Cells to Doxorubicin Leads to Long-Lasting Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2 Downregulation. Cells 2022, 11, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spengler, K.; Kryeziu, N.; Große, S.; Mosig, A.S.; Heller, R. VEGF Triggers Transient Induction of Autophagy in Endothelial Cells via AMPKα1. Cells 2020, 9, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu, A.Z.; Luu, V.Z.; Chowdhury, B.; Kosmopoulos, A.; Pan, Y.; Al-Omran, M.; Quan, A.; Teoh, H.; Hess, D.A.; Verma, S. Loss of Endothelial Cell-Specific Autophagy-Related Protein 7 Exacerbates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Biochem Biophys Rep 2021, 25, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotsopoulos, J. BRCA Mutations and Breast Cancer Prevention. Cancers (Basel) 2018, 10, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BRCA1 and BRCA2: Cancer Risks and Management (PDQ®) - PDQ Cancer Information Summaries - NCBI Bookshelf. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK589498/ (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Roy, R.; Chun, J.; Powell, S.N. BRCA1 and BRCA2: Different Roles in a Common Pathway of Genome Protection. Nat Rev Cancer 2011, 12, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griendling, K.K.; FitzGerald, G.A. Oxidative Stress and Cardiovascular Injury: Part II: Animal and Human Studies. Circulation 2003, 108, 2034–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, G.; Wagner, J.R. ROS-Induced DNA Damage as an Underlying Cause of Aging. Advances in Geriatric Medicine and Research 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglia-Mari, G.; Zotter, A.; Vermeulen, W. DNA Damage Response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011, 3, a000745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luijsterburg, M.S.; van Attikum, H. Chromatin and the DNA Damage Response: The Cancer Connection. Mol Oncol 2011, 5, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, M.L.; Hazra, T.K.; Mitra, S. Early Steps in the DNA Base Excision/Single-Strand Interruption Repair Pathway in Mammalian Cells. Cell Res 2008, 18, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Huang, W.; Tang, S. Sirt3 Enhances Glioma Cell Viability by Stabilizing Ku70-BAX Interaction. Onco Targets Ther 2018, 11, 7559–7567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Hunt, C.R.; Chakraborty, S.; Pandita, R.K.; Yordy, J.; Ramnarain, D.B.; Horikoshi, N.; Pandita, T.K. Role of 53BP1 in the Regulation of DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathway Choice. Radiat Res 2014, 181, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, N.; Chen, Y.-C.M.; Spector, D.L.; de Lange, T. 53BP1 Promotes Non-Homologous End Joining of Telomeres by Increasing Chromatin Mobility. Nature 2008, 456, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Liang, S.; Ochi, T.; Chirgadze, D.Y.; Huiskonen, J.T.; Blundell, T.L. Understanding the Structure and Role of DNA-PK in NHEJ: How X-Ray Diffraction and Cryo-EM Contribute in Complementary Ways. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2019, 147, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Bozzella, M.; Seluanov, A.; Gorbunova, V. DNA Repair by Nonhomologous End Joining and Homologous Recombination during Cell Cycle in Human Cells. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 2902–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achanta, G.; Pelicano, H.; Feng, L.; Plunkett, W.; Huang, P. Interaction of P53 and DNA-PK in Response to Nucleoside Analogues: Potential Role as a Sensor Complex for DNA Damage. Cancer Res 2001, 61, 8723–8729. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Ning, S.; Wei, Z.; Xu, R.; Xu, X.; Xing, M.; Guo, R.; Xu, D. 53BP1 and BRCA1 Control Pathway Choice for Stalled Replication Restart. Elife 2017, 6, e30523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, J.R.; Taylor, M.R.G.; Boulton, S.J. Playing the End Game: DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathway Choice. Mol Cell 2012, 47, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Heyer, W.-D. Homologous Recombination in DNA Repair and DNA Damage Tolerance. Cell Res 2008, 18, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, L.S.; Ostermeyer, E.A.; Szabo, C.I.; Dowd, P.; Lynch, E.D.; Rowell, S.E.; King, M.C. Confirmation of BRCA1 by Analysis of Germline Mutations Linked to Breast and Ovarian Cancer in Ten Families. Nat Genet 1994, 8, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godin, S.K.; Sullivan, M.R.; Bernstein, K.A. Novel Insights into RAD51 Activity and Regulation during Homologous Recombination and DNA Replication. Biochem Cell Biol 2016, 94, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLachlan, T.K.; El-Deiry, W. Functional Interactions Between BRCA1 and the Cell Cycle; Landes Bioscience, 2013.

- Petrucelli, N.; Daly, M.B.; Pal, T. BRCA1- and BRCA2-Associated Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J., Gripp, K.W., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington, Seattle: Seattle (WA), 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg, T.; Frost, D.; Barrowdale, D.; Evans, D.G.; Bancroft, E.; Adlard, J.; Ahmed, M.; Barwell, J.; Brady, A.F.; Brewer, C.; et al. Prostate Cancer Risks for Male BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers: A Prospective Cohort Study. Eur Urol 2020, 77, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Yadav, S.; Ogunleye, F.; Zakalik, D. Male BRCA Mutation Carriers: Clinical Characteristics and Cancer Spectrum. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abul-Husn, N.S.; Soper, E.R.; Odgis, J.A.; Cullina, S.; Bobo, D.; Moscati, A.; Rodriguez, J.E.; CBIPM Genomics Team; Regeneron Genetics, Center; Loos, R.J.F.; et al. Exome Sequencing Reveals a High Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Founder Variants in a Diverse Population-Based Biobank. Genome Med 2019, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, R. Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer (HBOC): Review of Its Molecular Characteristics, Screening, Treatment, and Prognosis. Breast Cancer 2021, 28, 1167–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, P.L.; Chatterjee, N.; Hartge, P.; Tucker, M.; Brody, L.; Struewing, J.P.; Wacholder, S. Potential Excess Mortality in BRCA1/2 Mutation Carriers beyond Breast, Ovarian, Prostate, and Pancreatic Cancers, and Melanoma. PLoS One 2009, 4, e4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BRCA1 Protein Expression Summary - The Human Protein Atlas. Available online: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000012048-BRCA1 (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Hagemeister, F.B.; Buzdar, A.U.; Luna, M.A.; Blumenschein, G.R. Causes of Death in Breast Cancer: A Clinicopathologic Study. Cancer 1980, 46, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florido, R.; Daya, N.R.; Ndumele, C.E.; Koton, S.; Russell, S.D.; Prizment, A.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Matsushita, K.; Mok, Y.; Felix, A.S.; et al. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among Cancer Survivors: The Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022, 80, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.K.; Shukla, P.C.; Quan, A.; Desjardins, J.-F.; Lovren, F.; Pan, Y.; Garg, V.; Gosal, S.; Garg, A.; Szmitko, P.E.; et al. BRCA2 Protein Deficiency Exaggerates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis and Cardiac Failure. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 6604–6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.K.; Shukla, P.C.; Quan, A.; Al-Omran, M.; Lovren, F.; Pan, Y.; Brezden-Masley, C.; Ingram, A.J.; Stanford, W.L.; Teoh, H.; et al. BRCA1 Is a Novel Target to Improve Endothelial Dysfunction and Retard Atherosclerosis. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 2013, 146, 949–960.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, M.; Fradley, M.; Sun, W.; Kim, J.; Zhao, X.; Pal, T.; Ismail-Khan, R. An Exploratory Study to Determine Whether BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers Have Higher Risk of Cardiac Toxicity. Genes (Basel) 2017, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, E.J.; Nair, A.; Daoud, Y.; Blum, J.L. The Incidence of Cardiomyopathy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers after Anthracycline-Based Adjuvant Chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017, 162, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).