1. Introduction

Road networks extend for thousands and thousands of kms and very often provide a snapshot of the income level of the country where they are located. Distressed and/or perfect pavement surfaces provide immediate insight about the budget invested in Road maintenance by Road Agencies (RAs). The progressive increase in road pavement distress is a natural phenomenon, and as people age, so do the roads. As time passes, however, they must be promptly "treated" to slow down the aging process and maintain an acceptable and safe condition for all road users. Friction levels, roughness, permanent deformations and potholes are all types of distress generally visible on the pavement surface. The more the level of distress severity increases, the more these phenomena are visible and could affect driving comfort and traffic safety.

As mentioned, age is one of the most important variables affecting road distress evolution in terms of severity and decay speed. The cost of maintenance intervention and pavement restoration accordingly increase.

Therefore, RA needs low-cost management plans to detect the most distressed sites and quickly arrange appropriate interventions that mitigate and repair the road pavement anomalies before they become dangerous for traffic.

The common Pavement Management System (PSM) is based on a Monitoring system capable of describing the road surface quality. This process is normally conducted by inspections, which, however, represent a time-consuming and subjective approach that directly exposes administration personnel to the risk of traffic. Sometimes the monitoring phase is conducted by high-performances devices that allow RA to survey the entire road pavement structure, both in terms of ride comfort and structural performance. The extensive use of this methodology, very accurate and based on a combination of image and sensor data processing, can also be very expensive. Therefore, an alternative low-cost monitoring method needs to be identified, certified, and used especially for routine monitoring.

Lekshmipathy et al. (2020) [

1] defines the vibration-based methods that are most effective in the daily monitoring of road network conditions. If appropriately integrated with more accurate monitoring methods and with distress trends, they offer the best solution in terms of repair and maintenance interventions to be performed in accordance with the detected pavement surface distress level.

The GPB technique proposed by Meocci et al. (2021) [

2], which has been tested on several road sections within the Florence Municipality [

3,

4], could represent a good solution in the daily collection of pavement surface data. However, the vibration-based method, as defined in scientific literature, is strongly dependent on the speed of the equipped vehicles [

5,

6]. Consequently, the data recorded is affected by bias and can sometimes not be used due to the difference in vehicle speed during the monitoring process.

In this context, the need to both perfect the methodology proposed in 2021 by Meocci et al. [

1] and make it reliable and immediately applicable at the same time has arisen. The possibility of using a crowdsourcing approach directly applicable to the road network has therefore become the main objective of this study. In these terms, both the definition of the influence in the proposed methodology of the monitoring speed and the effect of speed values on the descriptive indicators of the road surface condition are investigated. At the same time, the research proposes a simple methodology to overcome the issue, making a road section immediately classifiable by only two parameters: monitoring speed and the distress index (GPB index).

The analysis carried out also defines the limitations of the process proposed.

2. State of the art

Starting in the last decade, many studies have been conducted on the possibility of assessing road pavement conditions by employing a sensor (such as a black box, accelerometers or smartphones) to be used inside cars.

The premise is that when a vehicle circulates on a distressed road surface (e.g. characterized by potholes, cracking, unmaintained manholes) it produces more vibrations compared to a perfectly maintained road pavement surface [

5]. This is the principle used for standardized index evaluation, such as the IRI index [

7,

8,

9,

10], but also with reference to non-standardized procedures and indices [12–16].

In 2008 Eriksson et al. investigated the possibility to detect road surface distress using the pothole Patrol (P2) system, an application that uses taxis equipped with mobile sensors (accelerometers and GPS sensors) and the associated algorithms to define road surface conditions according to vibration data [17].

Similar techniques, called RCM-TAGPS were developed by Chen et al. in 2011. In this case, a three-axis accelerometer and a GPS sensor equipped vehicle were used to collect high frequency data. The data recorded was analyzed by a Power Spectral Density to evaluate the roughness of the road [18].

In the same years, similar studies were conducted using the accelerometer and the sensor inside the smartphone. For example, Mohan et al. (2008) proposed the Nericell system, an application that records traffic and road conditions using data recorded by the sensors on smartphones that users carry with them when they drive a car [19]. Other studies investigated the road surface status with GPS equipped smartphones and inertial sensors: accelerometer and gyroscope or other specific applications developed to monitor the road with the smartphone [20–24].

In Sri Lanka they developed a crowdsourcing method, called Bus Net, capable of improving environmental surveying and providing information about road pavement conditions [25].

In recent years, this topic has been extensively debated, with the consideration of new data analysis techniques such as Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence [12,26–29]. Martinelli et el. processed the real data collected by sensors located on car dashboards and floorboards, employing decoding algorithms machines. These propose a plausible technology capable of detecting any kind of road surface distress and ranking it according to a data clusterization based on the coefficient of variation and entropy [12].

Shtayat et al. used two multi-classification Learning Models Machines (Random Forest and Decision Tree) to classify and automatically detect different kind of pavement distress. Moreover, their research with a Support Vector Machine algorithm developed a binary model for the same classification and detection purposes [26].

Other authors instead compared different methods to define pros and cons. For example, Kim et al. analyzed pothole detection with vibration, vision and 3D reconstruction methods [30]. Dib et al. compare instead deep learning techniques and non-deep learning techniques for detecting damaged road surfaces [31].

Ferjani instead stated that there are several systems based on the data collected by sensors inside the cars, especially with reference to accelerometers present in smartphones, but these methods require great attention in the dataset elaboration to provide accurate and reliable results that also include for example information regarding time, frequency, and wavelet-domain signal features. In his study, the problem was addressed using machine learning models to detect and classify the road anomalies [27].

As described in the review conducted by Coenen et al. in 2017 [32], a delay in the diffusion of the vibration-based methods was recorded due to complex data analysis affected by multiple variables. It was accordingly impossible to offer the market a reliable approach [27], when compared with a vision-based technique that’s more expensive but more popular in Road Surveying Market.

Sensors features, such as vehicle model, kind of indicator used to check a road surface condition, and survey speed are main elements affecting the vibration process. In particular, the latter is more effective in the case of a crowdsourcing approach used for data collection.

Acceleration values and the different speed performed in different road contexts, but also in the same context, for example the urban road network can be very different.

In past studies, the speed effect on the quality of the vibration-based methodology was both analyzed and sometimes eliminated by normalization procedures. When a vehicle runs over a road distress area, e.g., such as a pothole or an unmaintained manhole, at different speeds, the amplitude of the vertical acceleration collected can change, first in amplitude but also in frequency due to the different effects of the vibration induced by road surface on the vehicle itself. A few approaches to solve the problem propose modelling of that effect, for example, using a theoretical model including road profile, tires and suspension. In the study conducted by Alessandroni et al. it was demonstrated that the speed effect on the acceleration in the vehicle cabin was identified by a gamma function [29].

Fox et al., in their study the direct effects of speed on road distress detection was examined, proving that high speed increases the level of difficulty in ranking road pavement conditions [34].

Many approaches consider speed as included in different ranges and not as a continuous function. Sebestyen et al. and Sinharay et al. for example, normalized the result obtained according to speed ranges [35,36]. The same approach was proposed in [9], where the authors normalized the RMS of the signal by the variance of the signal itself (vertical acceleration) as proposed in other studies conducted by Zeng et al. [37] and Chou et al. [38].

Seraj et al. on the other hand processed smartphone data according to time domain, frequency domain and wavelet transformation. They also proposed an efficient methodology to reduce speed effects influence in detection and classification of road pavement distress, by amplifying the segment of the signal caused by the distress in accordance with vehicle speed [39].

In any case, the most popular approach proposed different algorithms for different speeds [19,24,39–41], effectively making the proposed systems very difficult to apply and different each time or for each type of road (e.g., rural or urban) either in reference to standard indicators (e.g., IRI) or by means of specific indicators or also in reference to the classification of distress carried out using a machine learning approach.

At first this research referred to a standard speed e.g., ranging from 30 km/h and 40 km/h. All the same, considering literature analysis offers several different techniques too different from one another and not robust enough to account for the effect of a vehicle’s speed, in this paper the effect of the speed was first analyzed in terms of statistical process. After this, a simple process based on machine learning algorithms was used to determine decision boundaries for different severity levels in a simple way and offer an inexpensive and user-friendly approach to analyzing road surface conditions and its influence on the speed effect.

2. Methods

3.1. Experimentation Overview

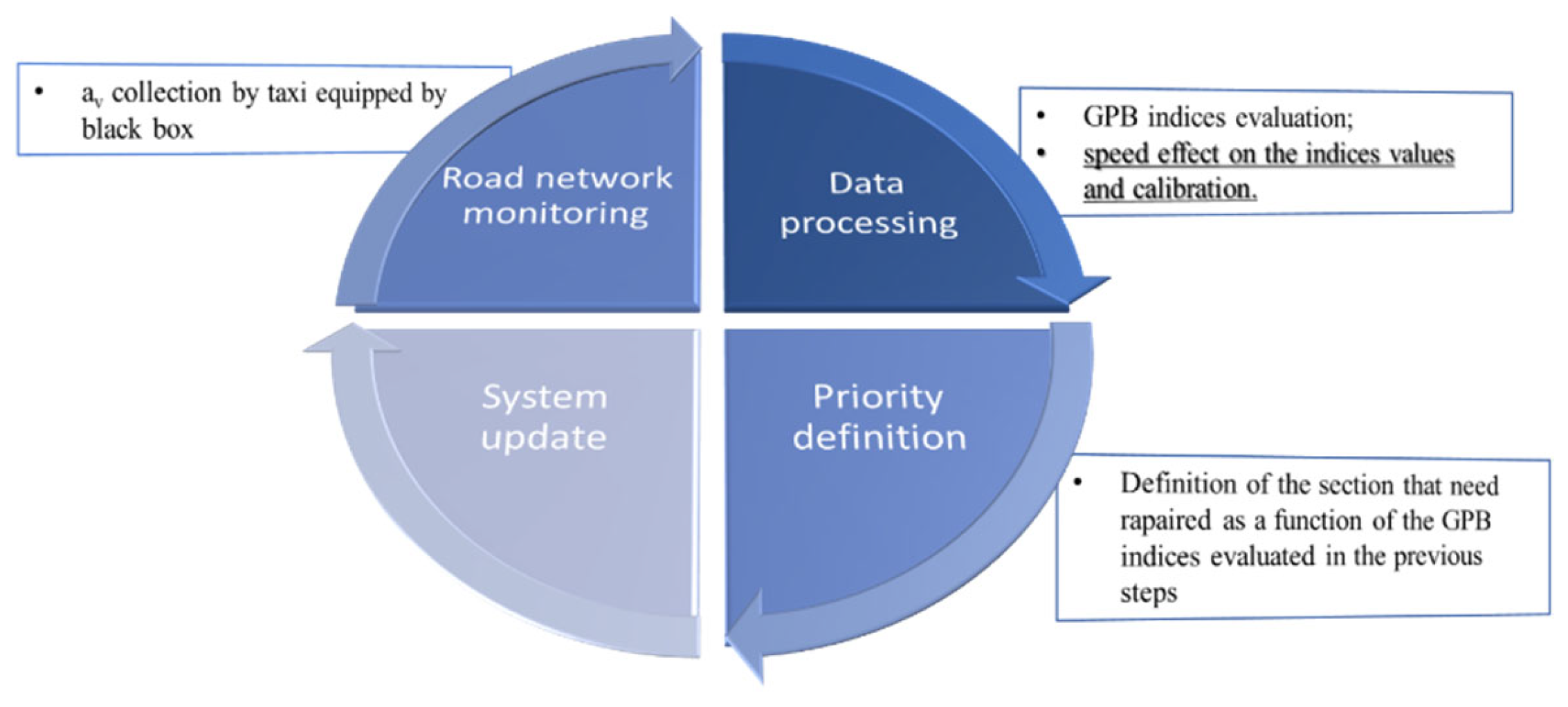

The procedure defined for the road network screening was summarized in

Figure 1. It consists of monitoring the road network (or road section as in this case) and recording the vertical acceleration on the taxis equipped with the black box that routinely pass across the road network.

Data processing and last classification of the road networks maintenance are completed by the procedure based on the distress index evaluation (GPB index). Each time one road segment was covered by a taxi passage, the monitoring process offers information about the pavement condition for this specific segment within the overall road network. Consequently, to this information, the segment information in the overall system needs to be updated.

The proposed system constitutes a starting point to manage and maintain roads pavement, especially for the urban context.

3.1. Monitoring procedure and evaluation index

Toyota Prius Hybrid 1.8 taxi vehicle equipped with black boxes were used to record vertical acceleration along four road segments within the Florence Municipality Road network.

The black box used consists of one simple device composed by one inertial accelerometer able to record acceleration in all the three directions, X, Y and Z; one triaxial gyroscope and a GPS device. The device was characterized by a sampling rate of 0.001 s in time (100 Hz). This frequency is consistent with the sampling frequency of the devices used and described in past research [2,17]. For each direction the maximum acceleration recordable is equal to 16g, representing a very high value in comparison to the vibrations (and accelerations) recorded by the distressed road surface.

The black box is connected to the car floorboard, between the pedals and gearbox, as close as possible to the car center of gravity in order to minimize centrifugal/centripetal force effects on the recorded signal.

This device does not require any installation and calibration procedure. As GPS connection is stabilized, the taxi can regularly travel according to clients requested destinations.

Road sections were tested at speeds ranging between 20 and 50km/h.

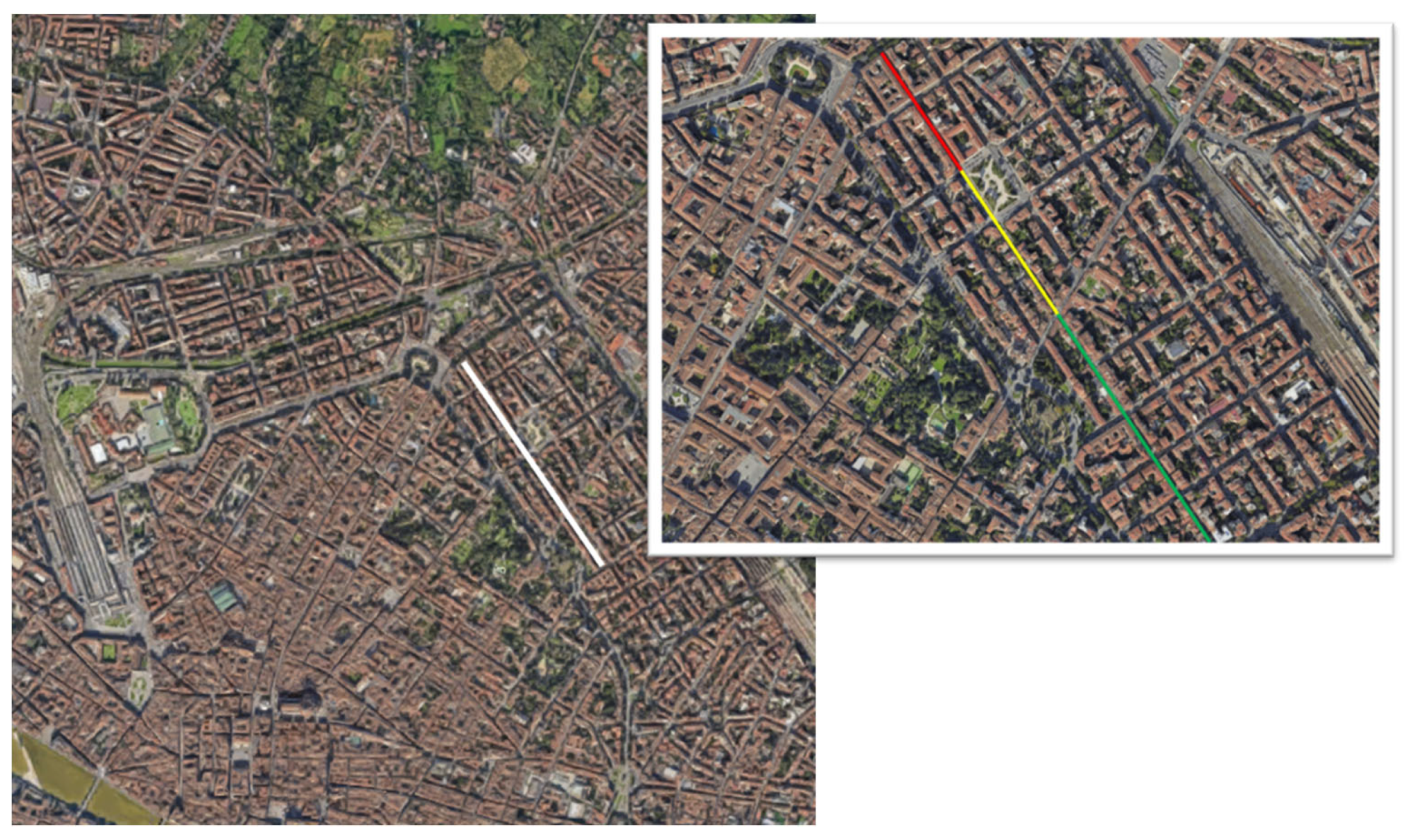

Sometimes the speed recorded was a bit less or greater than this range, but consistent with the driver’s speed within the urban context. In

Figure 2 the road sections analyzed are shown (in white). The entire path monitored was divided into four sections characterized by different distress levels.

The data recorded by the monitoring were used both for the identification and classification of the pavement surface damage and severity.

The procedure proposed was based on the evaluation of the vertical acceleration value recorded during the road monitoring (when taxis run across the road network). A simple algorithm allows the estimation of the Global Pave Box Index (GPB) as described in Meocci et al. [

2]. The index is based on the Equation (1).

where

stands for the moving variance of vertical recorded acceleration (a

v) and L represents the total length of road segment. The Equation (2) describes the moving variance estimation.

As a function of the GPB values obtained, three severity levels were defined to describe the pavement condition: low, medium and high (

Table 2).

These levels characterize the condition of the road pavement to be considered in the definition of a priority plan for maintenance and restoration operations on the entire road network.

A fourth and final level must however be defined for all those cases in which the intervention has to be carried out immediately for road safety. In this case, the index does not contribute to the prioritization of the intervention but gives to the RAs an alert defined as the immediate "need for repair".

In

Figure 2 (on the right) is the classification of the road section analyzed, based on the GPB index. One road segment was included in the high severity distress level, one segment in the medium severity level and the last two segments were classified as low severity.

3.2. Data processing

The distress index evaluated (GPB) was used to assess how speed effect impacts on the evaluation process and understand how survey speed affects this proposed methodology, in accordance with literary research findings.

The analysis was conducted by dividing the dataset into three different classes, one for each severity level (low, medium and high). This was done in accordance with the four segments monitored in the research, the pavement conditions of which belong to different distress severity classes (one segment was classified in high severity, one in medium severity and the last two in low severity).

The speed effect was than analysed by statistical approach, with the road surface distress, evaluated in terms of GPB index considered as a dependent variable.

A preliminary Levene’s test was performed to assess the equality of variances (homoscedasticity) of the dataset used for the statistical analysis. Then, a one-way ANOVA test was performed to evaluate whether there were statistically significant effects of the speed on the dependent variable. First, the ANOVA test was performed on the whole dataset, and later repeated three times, one for each road segment sample, considering implicitly the segment severity distress level and next combining the 2 classified segments in the same level (low severity).

Speed was ranked in three different ranges < 30 km/h, 30-40 km/h and 40-50 km/h respectively named 1, 2 and 3 in the analysis. The independent variable was then represented by the speed range (1, 2 or 3) associated with each GPB index obtained.

The two following hypotheses were postulated and evaluated by the ANOVA test:

(a) null hypothesis (H0): GPB values obtained from the three speed ranges can be considered as belonging to the same population, hence speed surveying does not affect the results in terms of severity classification;

b) alternative hypothesis (H1): the GPB index values do not belong to the same population, therefore, there is a significant difference between the GPB value estimated at different speeds. In this case, the classification of the road pavement condition needs to be made carefully, with reference (only) to specific range of survey speed.

In the statistical analysis a level of significance equal to 95% was selected.

Because the scientific and technical literature highlight a large dependence of the vibration-based methods on the speed of the vehicle which conducted the monitoring [

5] and also highlight the issues related to different processes to consider the effect of the variable in both the distress detection and classification, a simple, replicable and reliable procedure was proposed to take into account the speed effect.

A cluster analysis to classify the information obtained by the data processing procedure was finally proposed. In this last step, the entire dataset was divided as a function of the severity level and the decision boundaries between the severity levels defined by a Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithm to directly obtain the classification of the road surface distress by the couple represented by speed-GPB values without any correction.

3. Results and discussion

For each section, the value of the GPB index was evaluated according to the above briefly described procedure proposed by Meocci et al. [

2]. A total of 926 GPB index was considered.

Table 3 shows the average value of the GBP index for each section, and the descriptive statistics associated with the considered section.

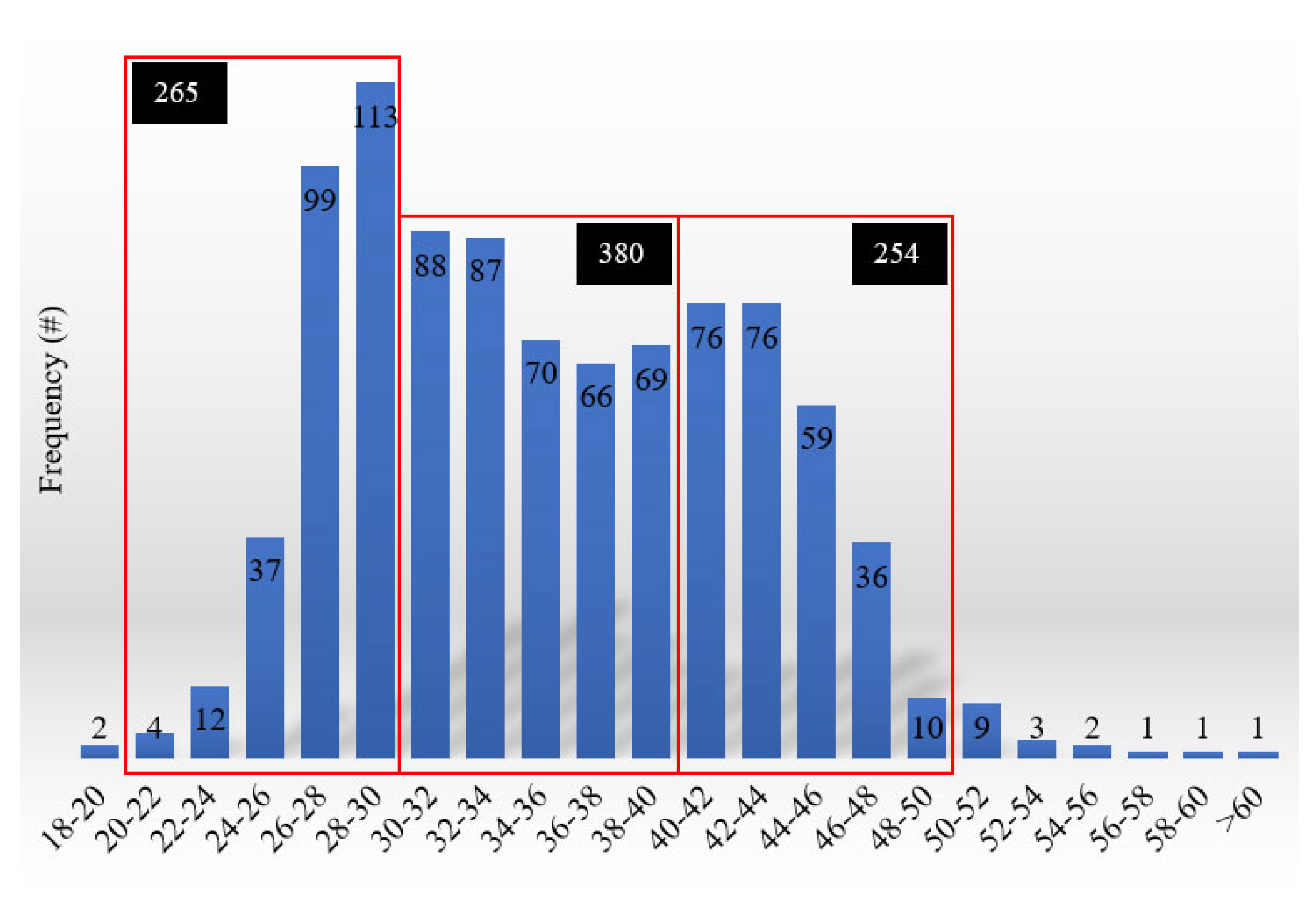

According to the dataset the range between 30km/h and 40 km/h was the most representative in urban areas speed survey.

Figure 3 shows speed distribution.

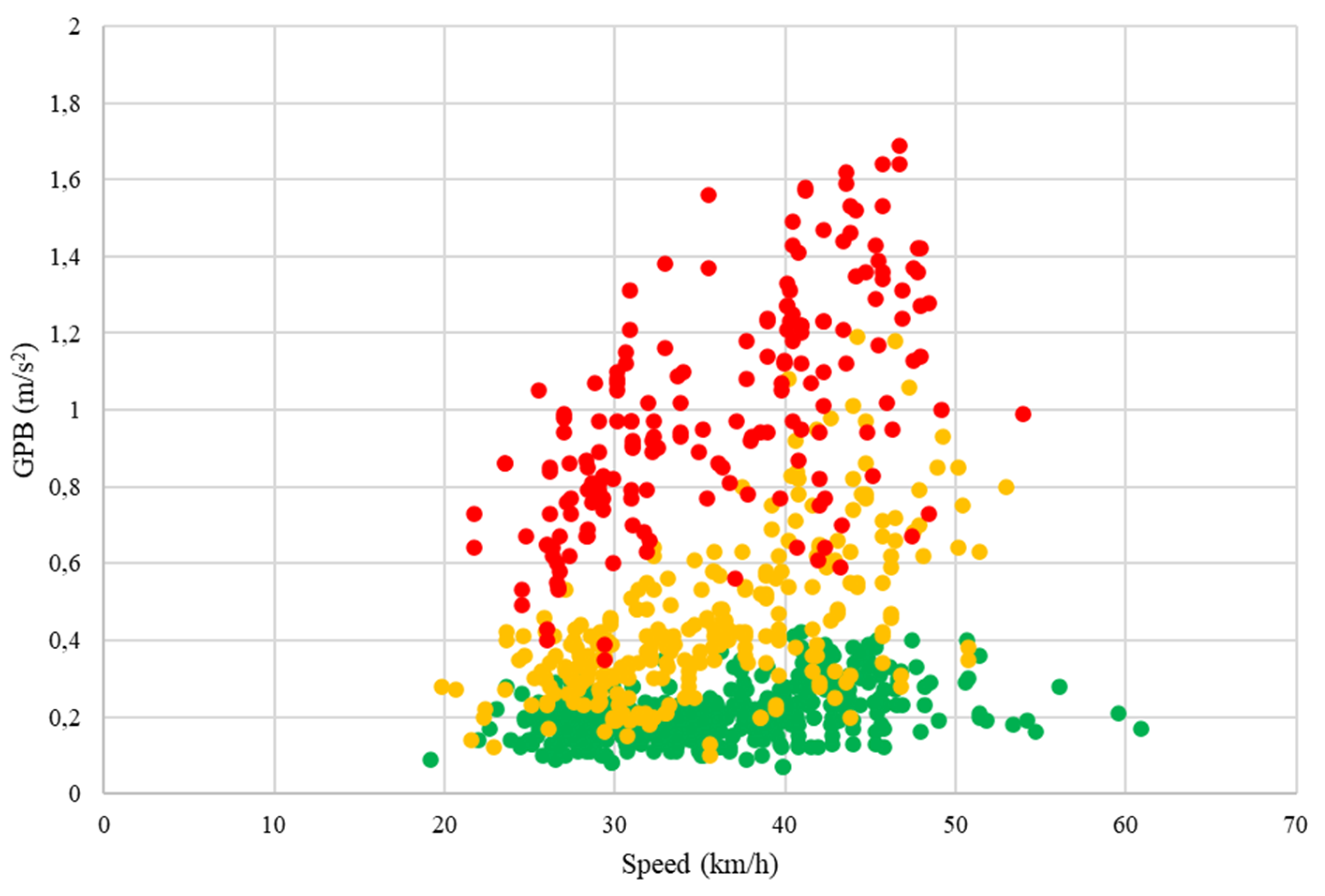

In

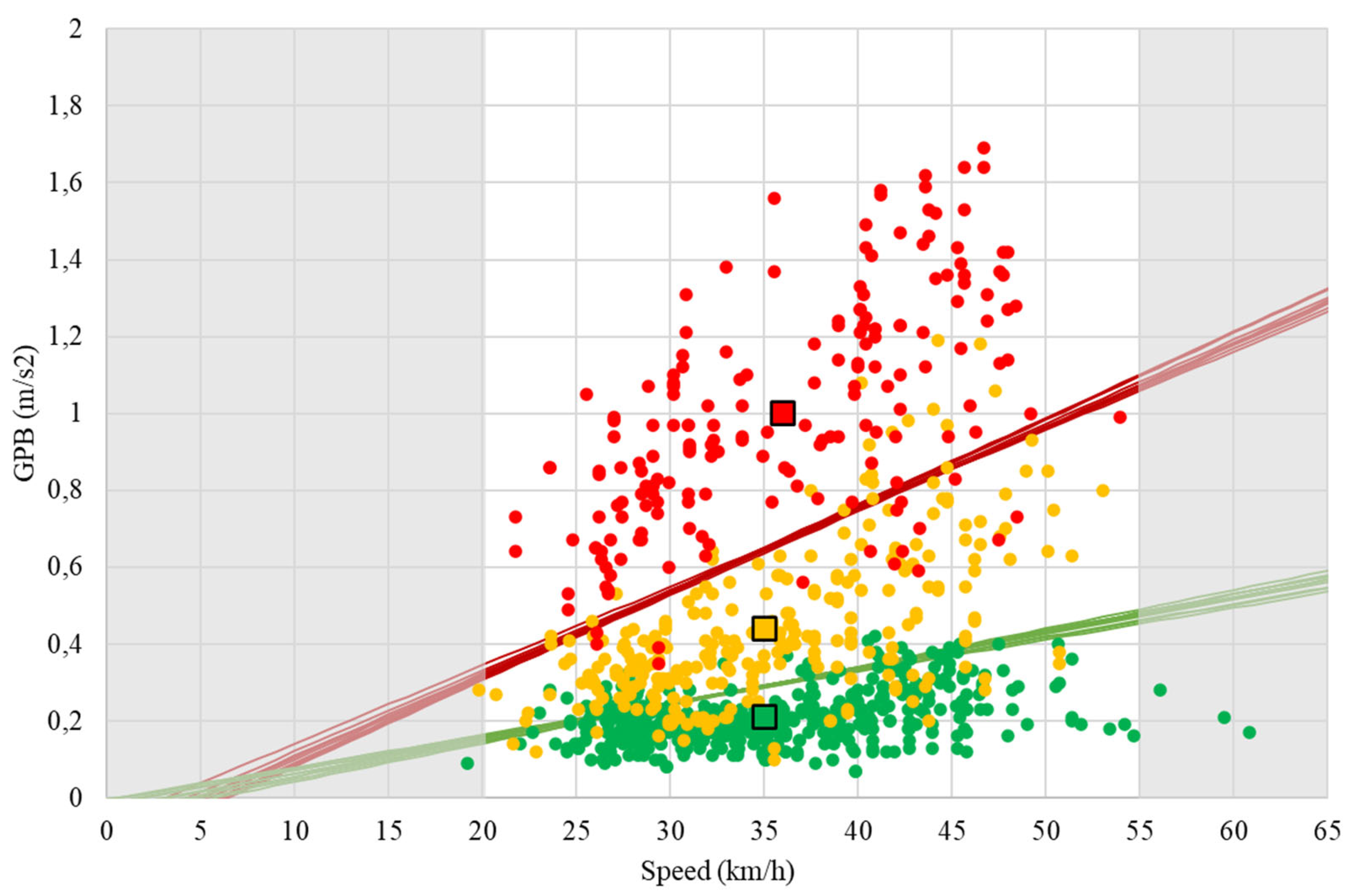

Figure 4 all the GPB evaluated were plotted as a function of the speed. The colours used referred to the severity of the pavement distress per segment. Segments 3 and 4 were considered together (green data).

From a quality point of view,

Figure 3 shows a data stratification, especially in low/high distress levels. The phenomenon was instead not particularly evident for GPB included in the medium severity class, with scattered data that also overlapped with the other severity classes.

The ANOVA test conducted was based on two assumptions:

The two tests were conducted on the dataset, first considering all data, then per each severity class. In both tests the estimated p-value was less than 0.05, therefore both hypotheses were violated.

The ANOVA test was usually robust, so the test was conducted, but in association with the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test.

Table 4 shows the result of the ANOVA test conducted. The p-value indicates that the H

0 hypothesis cannot be rejected, therefore, somewhere in the three groups were data that did not show statistically significant differences.

The analysis was completed by a pairwise post-hoc Turkey’s test, to check for any difference in the meaning of all possible pairs using a studentized range distribution. The results obtained are summarized in

Table 5.

The test found a statistically significant difference between groups 1 and 3 and 2 and 3. Instead, no significant difference was found between groups 1 and 2. Therefore, the analysis conducted with a speed ranging from a minimum value of 20 km/h and 40 km/h did not affect the GPB results. Instead, the GPB value related to the high value of monitoring speed, greater than 40 km/h, affects the value of the index evaluated and therefore could change the severity estimations.

The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test confirms the result obtained in the ANOVA test. In

Table 6 the results obtained are summarized.

This test was repeated after arranging the dataset per severity class, high, medium and low, including data for segments 3 and 4. The two hypotheses were invalidated, so both ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis tests were repeated.

Table 7 summarizes the results obtained.

The tests allowed us to observe that within each severity class, a statistically significant difference was observed for different classes of speed, except for the low severity distress class where a statistically significant difference was not detected for speed ranging in class 1 and 2. Results obtained are therefore similar to those obtained in the first statistical analysis.

The Support Vector Machine (SVM) analysis for the definition of the decision boundaries were repeated two times, the former considering linear decision boundaries and the latter considering power functions decision boundaries (Equation 3 and 4). In each analysis, the overall dataset was split into a training set (80%) and a test set (20%).

Two decision boundaries were proposed to cluster data in the different severity distress conditions. Ten iterations were repeated to split the dataset in different and casual way. The coefficients obtained for the functions in each iteration conducted were summarized in

Table 8.

The ability of the model to correctly predict the cluster per each iteration was summarized in

Table 9, both for linear and power functions decision boundaries.

Table 9 shows a good ability to propose decision boundaries to predict the severity class of the road condition surface given the information about GPB and speed. The minimum value was observed for the medium severity level, which had an average value equal to about 77%. The values for the other classes were instead higher, and equal to 90% and 87% respectively for low and high severity. There weren’t differences between linear and parabolic functions to be highlighted.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show all the decision boundaries found. The accuracy obtained with this procedure is similar to or greater than those obtained in other literature research conducted by machine learning and artificial intelligence [5,6,26,27].

The two graphs showed that both parabolic and linear decision boundaries allow a good prediction of the severity level of the data couple represented by speed and GPB. However, it is important to highlight that it is not appropriate to extrapolate the prediction outside the limits of the speed range described by the dataset. Indeed, for the lower limits, we can note that the linear function, for speed values close to 0 cannot be used due to the inversion of the two decision boundaries. On the contrary, the parabolic function tends to diverge a lot for high-speed values. Therefore, it is necessary to highlight that the procedure proposed needs to be limited to a relevant speed range between 20 km/h and 55 km/h which, in any case, covers the usual speed range used in the urban context.

5. Conclusions

Nowadays, many monitoring methodologies are available; some of them are characterized by high performance but also high costs, and others are characterized by limited and subjective performance and high time consumption. The vibration-based system called Pave Box, consists of a user-friendly and cheap method based on the data crowdsourcing approach. Data collection uses the inertial devices (black boxes) located inside the taxi vehicles that routinely accompany passengers in the road context of Florence Municipality. A simple algorithm allows the users to estimate the road surface distress based only on vertical acceleration recorded by the inertial devices.

Many other procedures similar to the Pave Box Methodology have been proposed by scientific literature, but none are currently directly applicable and widespread enough in the area to carry out low-cost road pavement monitoring.

In this context, the need both to perfect the methodology proposed in 2021 and make it reliable and immediately applicable, has allowed for improvements in the research dedicated to the analysis of the speed effect on the method results.

First, by means of a statistical analysis, the significance of speed in the distress index evaluation was estimated. Then a simple and structured process to overcome the effect of speed in the severity level evaluation is proposed. The procedure is based on the data stratification for each severity level, only as a function of the monitoring speed. The use of a Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithm allowed the definition of the decision boundaries between the different severity levels and the direct identification of the road segment pavement condition in terms of distress severity through only two data, speed and GPB index. The ability to correctly predict the severity level range as a function of the decision boundaries and the average values is close to 90% except for the intermediate distress severity where a 77% accuracy was defined.

These tangible results promoted the use of the process in the urban area.

Funding

This research was funded by FONDAZIONE ENTE CASSA DI RISPARMIO DI FIRENZE, grant number 2020.1559, project CIMABUHE “Car floating Information for Monitoring road Anomalies By Using High AccEleration value”

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Atena Ingegneria Srl for providing all the black boxes used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lekshmipathy, J.; Samuel, N.M.; Velayudhan, S. Vibration vs. vision: based approach for automated pavement distress detection. International Journal of Pavement Research and Technology, 2020, 13, pp. 402–410.

- Meocci, M.; Branzi, V.; Sangiovanni, A. An innovative approach for high-performance road pavement monitoring using black box. Journal of Civil Structural Health Monitoring, 2021, 11(2), pp. 485-506. [CrossRef]

- Meocci, M.; Branzi, V. Black Boxes data for Road Pavement Condition monitoring: a case study in Florence. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on the Bearing Capacity of Roads, Railways and Airfields, Trondheim, Norway, 27-20 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meocci, M. A road pavement monitoring process for urban road: the case study of via Leonardo Da Vinci in Florence. Presented at XXVII Word Road Congress, Prague, Czech Republic, 2-6 October 2023.

- Sattar, S.; Li, S.; Chapman, M. Road Surface Monitoring Using Smartphone Sensors: A Review. Sensors 2018, 18, 3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranyal, E.; Sadhu, A.; Jain, K. Road Condition Monitoring Using Smart Sensing and Artificial Intelligence: A Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, A; O'brien, E.J.; Li, Y.Y.; Cashell, K. The use of vehicle acceleration measurements to estimate road roughness, Vehicle System Dynamics. 2008, 46(6), pp. 483-499. [CrossRef]

- Alavi,A.H.; Buttlar, W.G. An overview of smartphone technology for citizen-centered, real-time and scalable civil infrastructure monitoring. Future Generation Computer Systems, 2019, 93, pp. 651-672. [CrossRef]

- Alatoom, Y.I., Obaidat, T.I. Measurement of Street Pavement Roughness in Urban Areas Using Smartphone. Int. J. Pavimentazione Res. Technol., 2022, 15, pp. 1003–1020. [CrossRef]

- Alqaydi, S.; Zeiada, W.; Llort, D.; Elwakil, A. Using Smart Phones to Assessment Road Roughness in the UAE. In Proceedings of the 11th Annual International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Singapore, 7–11 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, E.; McGetrick, P.; González, A. Identifcation of Road Irregularities via Vehicle Accelerations. In Proceeding of Transport Research Arena Europe. Brussels, Belgium, 7-10th June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli, A.; Meocci, M.; Dolfi, M.; Branzi, V.; Morosi, S.; Argenti, F.; Berzi, L.; Consumi, T. Road Surface Anomaly Assessment Using Low-Cost Accelerometers: A Machine Learning Approach. Sensors 2022, 22, 3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loprencipe, G.; Vaz De Almeida Filho, F.G.; Oliveira, R.E.; Bruno, S. Validation of a Low-Cost Pavement Monitoring Inertial-Based System for Urban Road Networks. Sensors, 2021, 2, 3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wang, L. Investigating the pavement vibration response for roadway service condition evaluation. Advances in Civil Engineering 2018, 1196, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.X.; Yu, X. Vibration-based system for pavement condition evaluation. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Applications of Advanced Technology in Transportation, Chicago, IL, USA, 13–15 August 2006; pp. 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Carlos, M.R.; Aragón, M.; González, L.C.; Escalante, H.; Martínez, F. Evaluation of detection approaches for road anomalies based on accelerometer readings—addressing who’s who. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst, 2018, 19, pp. 3334–3343.

- Eriksson, J.; Girod, L.; Hull, B.; Newton, R.; Madden, S.; Balakrishnan, H. The pothole patrol: using a mobile sensor network for road surface monitoring. In Proceeding of the 6th international conference on Mobile system, applications and service, ser. MobySys’08, New York, NY, USA; 2008; pp. 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Lu, M.; Tan, G.; Wu, J. CRSM: Crowdsourcing Based Road Surface Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on High Performance Computing and Communications & 2013 IEEE International Conference on Embedded and Ubiquitous Computing, Zhangjiajie, China; 2013; pp. 2151–2158. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, P.; Padmanabhan, V.N.; Ramjee, R. Nericell: Rich monitoring of road and trafc conditions using mobile smartphones. In Procedeeng of 6th ACM Conf. Embedded Netw. Sensor Syst (SenSys), 2008, pp. 323–336.

- Douangphachanh, V.; Oneyama, H. A study on the use of smartphones for road roughness condition estimation. Journal of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies 2013, 10, pp. 1551-1564.

- Menant, F.; Martin, J.M.; Meignen, D. Using probe vehicles for pavement monitoring: experimental results from tests performed on a road network. Transportation Research Procedia 2016, 14, pp. 3013-3020.

- Forslöf, L; Jones, H. Roadroid: Continuous Road Condition Monitoring with Smart Phones. Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture 2005, 9, pp. 485-496.

- Perttunen, M.; Mazhelis, O.; Cong, F.; Distributed road surface condition monitoring using mobile phones. In Proceeding of the 8th International Conference on Ubiquitous Intelligence and Computing, Banff, 2011.

- Harikrishnan, P.M.; Gopi, V.P. Vehicle Vibration Signal Processing for Road Surface Monitoring. IEEE Sensors Journal, 2017, 17(16), pp. 5192-5197.

- Zoysa, K.D.; Keppitiyagama, C.; Seneviratne, G.P.; Shihan, W.W.A.T. A public transport system based sensor network for road surface condition monitoring. In: Proceedings of the Workshop on Networked Systems for Developing Regions, Kyoto, Japan, 27 August 2007, pp. 1–6.

- Shtayat, A.; Moridpour,S.; Best, B.; Abuhassan, M. Using supervised machine learning algorithms in pavement degradation monitoring, International Journal of Transportation Science and Technology 2023, 12(2), pp. 628-63. [CrossRef]

- Ferjani, I.; Alsaif, S.A. How to get best predictions for road monitoring using machine learning techniques. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2022, 8, e941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Ríos, E.A.; Bustamante-Bello, M.R.; Arce-Sáenz, L.A. A Review of Road Surface Anomaly Detection and Classification Systems Based on Vibration-Based Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhou, M.; Chen, Y.; Huo, M.; Sun, L.; Zhao, S.; Chen, D. A fused method of machine learning and dynamic time warping for road anomalies detection. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 23, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.M.; Kim, Y.G.; Son, S.Y.; Lim, S.Y.; Choi, B.Y.; Choi, D.H. Review of Recent Automated Pothole-Detection Methods. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dib, J.; Sirlantzis, K.; Howells, G. A Review on Negative Road Anomaly Detection Methods. IEEE Access, 2020, 8, 57298–57316.

- Coenen, T.B.J.; Golroo, A. A review on automated pavement distress detection methods. Cogent Eng. 2017, 4, 1374822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandroni, G.; Carini, A.; Lattanzi, E.; Freschi, V.; Bogliolo, A. A Study on the Influence of Speed on Road Roughness Sensing: The SmartRoadSense Case. Sensors 2017, 17, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, A.; Kumar, B.V.; Chen, J.; Bai, F. Crowdsourcing undersampled vehicular sensor data for pothole detection. In Proceedings of the 2015 12th Annual IEEE International Conference on Sensing, Communication, and Networking (SECON), Seattle, WA, USA, 22–25 June 2015; pp. 515–523. [Google Scholar]

- Sebestyen, G.; Muresan, D.; Hangan, A. Road quality evaluation with mobile devices. In Proceedings of the 2015 16th International Carpathian Control Conference (ICCC), Szilvasvarad, Hungary, 27–30 May 2015; pp. 458–464. [Google Scholar]

- Sinharay, A.; Bilal, S.; Pal, A.; Sinha, A. Low computational approach for road condition monitoring using smartphones. In Proceedings of the Computer Society of India (CSI) Annual Convention, Theme: Intelligent Infrastructure, Visakhapatnam, India, 13–15 December 2013; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, H.; Park, H.; Fontaine, M.; Smith, B.; McGhee, K. Identifying deficient pavement sections by means of an improved acceleration-based metric. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2015, 2523(1), pp. 133–142. [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.; Siao, G.; Chen, A.; Lee, C. Algorithm for estimating international roughness index by response-based measuring device. Journal of Transportation Engineering Part B: Pavements, 2020, 146(3), 04020031. [CrossRef]

- Seraj, F.; van der Zwaag, B.J.; Dilo, A.; Luarasi, T.; Havinga, P. RoADS: A road pavement monitoring system for anomaly detection using smart phones. In Big Data Analytics in the Social and Ubiquitous Context; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 128–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mednis, A.; Strazdins, G.; Zviedris, R.; Kanonirs, G.; Selavo, L. Real time pothole detection using android smartphones with accelerometers. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Distributed Computing in Sensor Systems and Workshops (DCOSS), Barcelona, Spain, 27–29 June 2011; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Best, B.; Shtayat, A.; Moridpour, S.; Shroff, A.; Raol, D. Optimising road pavement maintenance using vibration monitoring. In proceeding of 7th E&E Congress Eurasphalt & Eurobitume, Virtual, 15-17 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).