1. Introduction

Snakebites are a serious global health issue prevalent among poor populations, causing significant social problems [

1,

2,

3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates approximately 2.7 million snakebite incidents worldwide annually, resulting in about 81,000 to 138,000 fatalities and 400,000 survivors with enduring disabilities [

4,

5].

With high mortality and morbidity rates, snakebites primarily affect underprivileged populations in tropical and subtropical areas, according to the WHO, which recognizes them as a neglected tropical disease. Since 2017, snakebite envenoming has been listed among the 20 neglected tropical diseases, prompting a strategic plan to reduce fatalities by 50% by 2030. Despite being preventable and treatable, research investment in this area remains remarkably low [

6]. The Brazilian Academy of Sciences (BAS) has identified accidents involving venomous animals as a neglected disease in Brazil. One directive of BAS prioritizes supporting research on drug combinations for treating toxin-induced accidents [

7].

In Brazil, an average of 29,000 snakebite cases occurs annually, resulting in approximately 120 fatalities per year and around 600 cases with curable sequelae, excluding unreported cases. Among venomous snakes, the Viperidae family, particularly the subfamilies Crotalinae (including snakes of the genera

Crotalus,

Bothrops, and

Lachesis), are noteworthy [

8,

9].

Bothrops snakebites causes systemic reactions, such as severe blood clotting disorders [

10,

11], which are like symptoms of disseminated intravascular coagulation [

12]. Complications such as hypotension and hypovolemic shock can lead to fatalities. Severe local reactions comprising edema, pain, hemorrhage, and necrosis are common, often resulting in substantial tissue loss and potential amputations [

13,

14]. These reactions trigger inflammatory responses by starting up signaling pathways that cause the transcription of inflammatory genes, such as cytokines and eicosanoids [

15]. This causes endothelial activation with the expression of lectins and adhesion molecules, which causes the interaction of leukocytes with the endothelium, resulting in firm adhesion and cell migration [

16].

The pathogenesis of local reactions caused by

Bothrops venoms is still not fully understood because they are made up of a lot of different toxin classes that can work alone or together through different pathways in the body [

17,

18].

The only effective treatment for snakebite envenomation is specific antivenom [

6,

19,

20]. Despite its efficacy in reducing lethality and reversing systemic effects, antivenom inadequately addresses local reactions, causing severe sequelae [

10,

11,

13]. This deficiency arises from the rapid onset of these local actions and due the fact that the antivenomcannot reverse established or triggered injuries or neutralize endogenous mediators involved in the process [

10,

21].

Essential anti-inflammatory drugs include glucocorticoids (steroids), which inhibit early and late inflammatory manifestations, and non-steroidal drugs, among the most widely used globally [

22]. The literature shows that treating animals with anti-inflammatories, particularly phospholipase A

2 and cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors, significantly reduces edema induced by

Bothrops venoms [

23,

24,

25].

Despite evidence implicating endogenous mediators released at the venom injection site, using anti-inflammatories or other drugs alongside serotherapy remains uncommon in Brazil [

14]. The limited effectiveness of serotherapy in treating

Bothrops venom-induced local reactions prompts the search for complementary treatments to improve this condition. In recent decades, many studies have sought to understand local reactions caused by

Bothrops venoms and explore complementary therapies alongside antivenom. Making antivenoms better and more effective [

26], using protease inhibitors [

27], identifying animals resistant to snake venom [

28], and utilizing therapeutic combinations that work with serotherapy [

25,

29] are a few of these.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to ascertain which inflammatory mediators are involved in the alterations of the leukocyte-endothelium interactions following a Bothrops jararaca experimental envenomation. The goal was to find possible treatments that could be used along with antivenom to help reverse the severe effects of the venom's quick action.

The results have shown that alterations in the leukocyte-endothelium interactions induced by the Bothrops jararaca venom are mediated mainly by cyclooxygenase-derived eicosanoids and that the association of dexamethasone with the antivenoms could reduce this effect.

3. Results

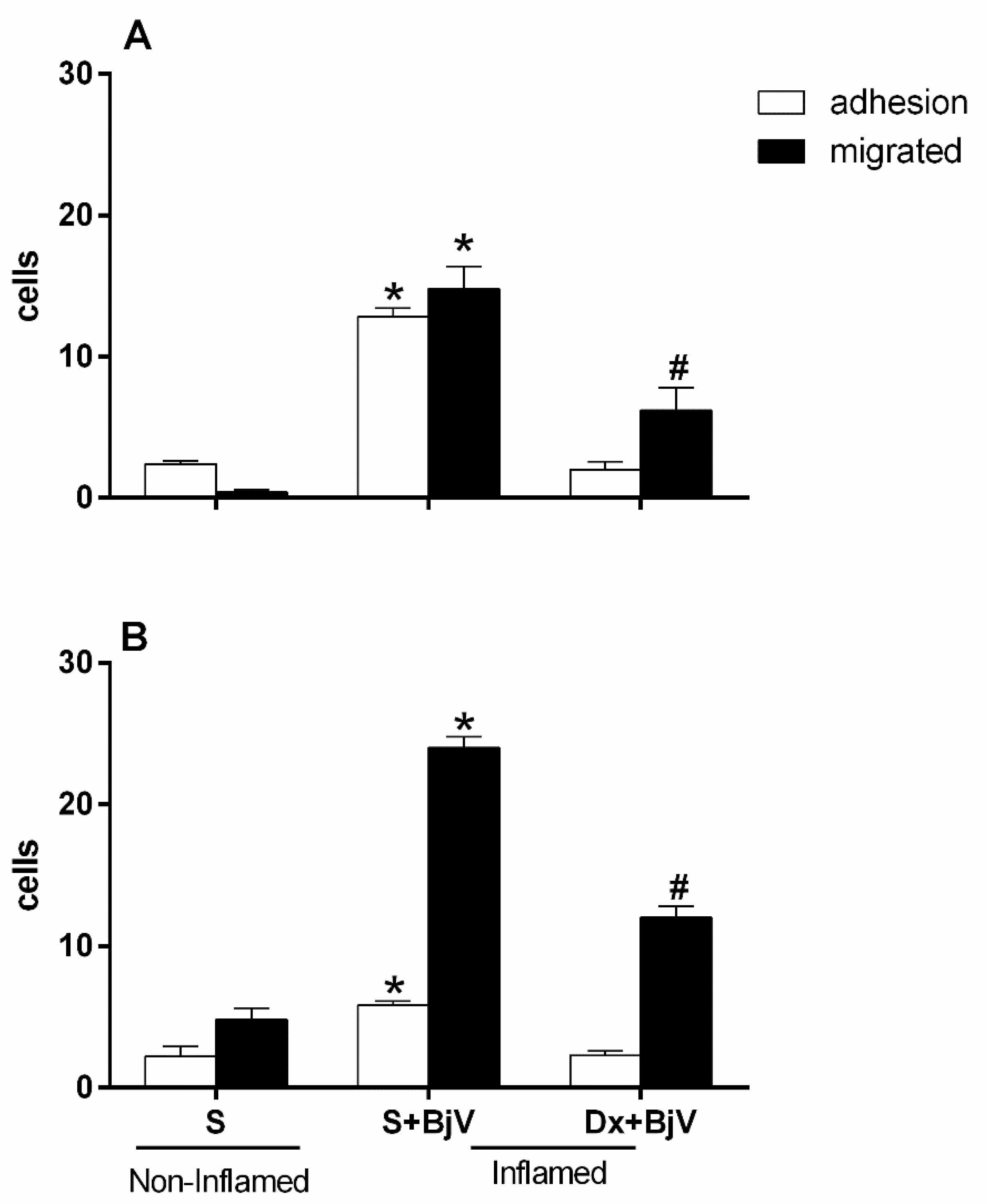

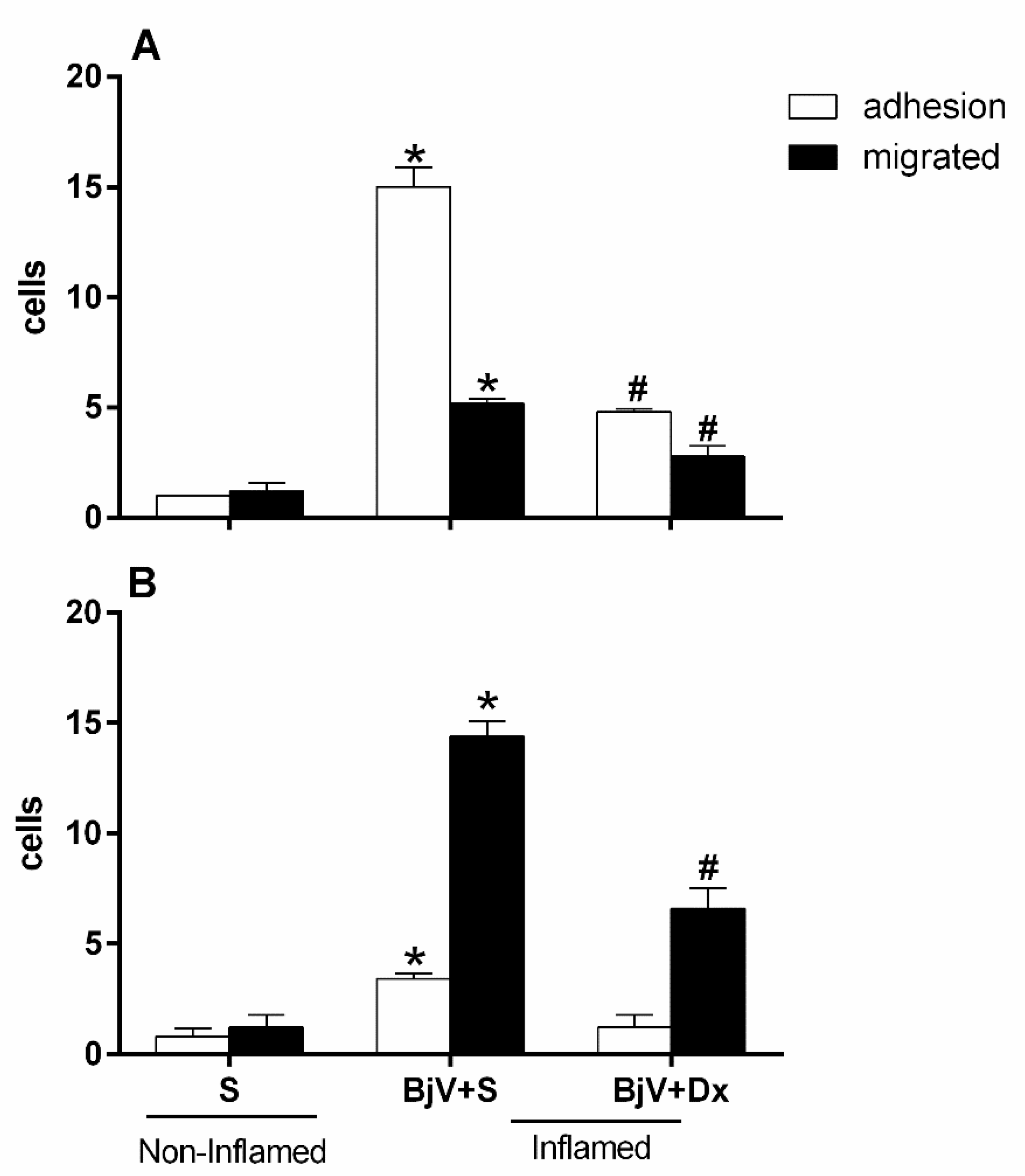

BjV induces changes in the leukocyte-endothelium interaction in the mouse's microcirculation cremaster muscle, with a significant increase in adhered and migrated cells after 2 hours (

Figure 1A) and 24 hours (

Figure 1B), respectively, after its exposure.

When we pre-treated with dexamethasone (Dx) 1 hours before venom injection with the purpose of verifying the participation of arachidonic acid degradation metabolites in leukocyte-endothelium interaction events induced by BjV injection, we observed that the treatment could reduce the number of adhered and migrated cells in the groups analyzed at 2 and 24 hours, when compared with the control or with the group inflamed only with BjV (

Figure 1A and

Figure 1B).

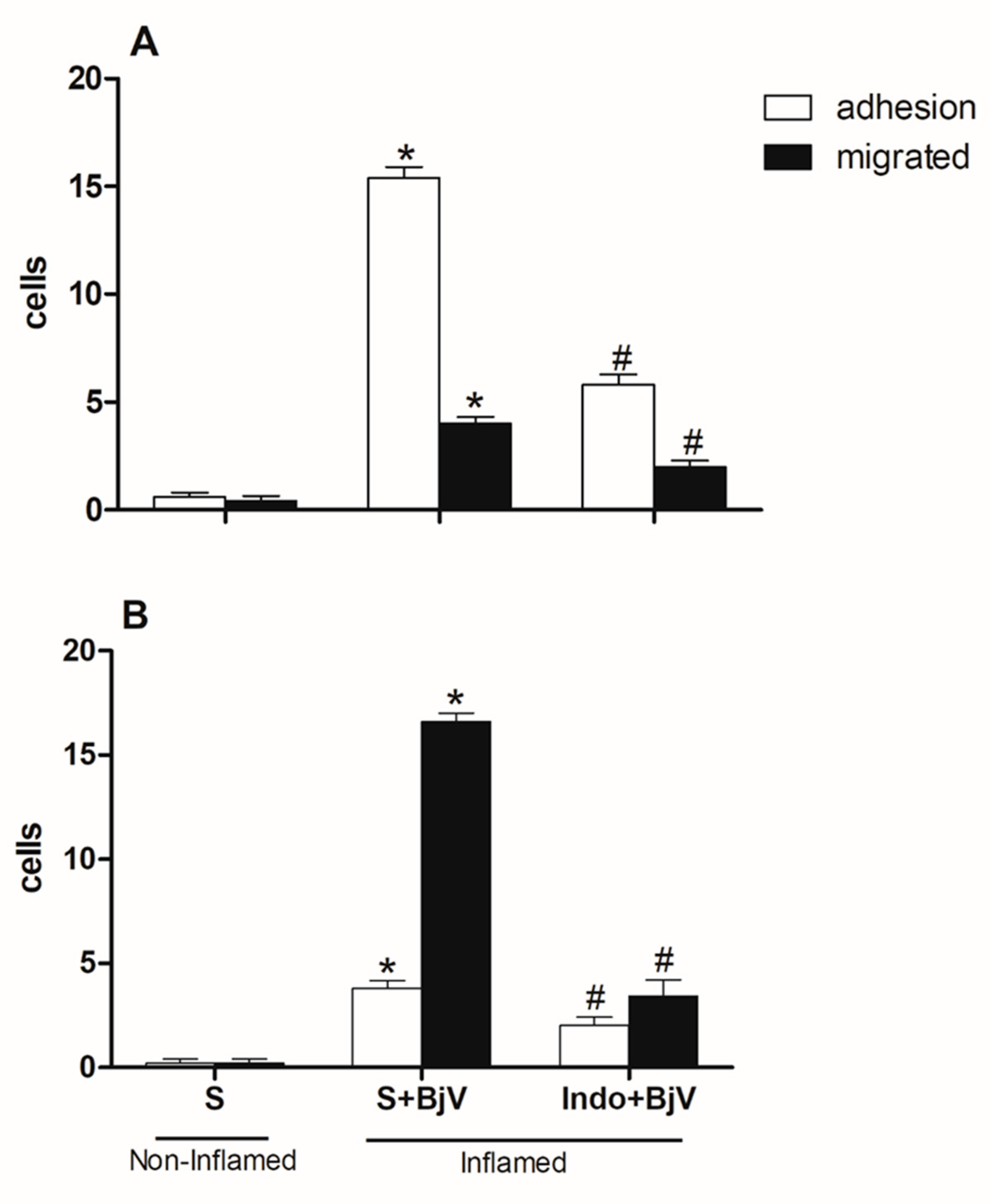

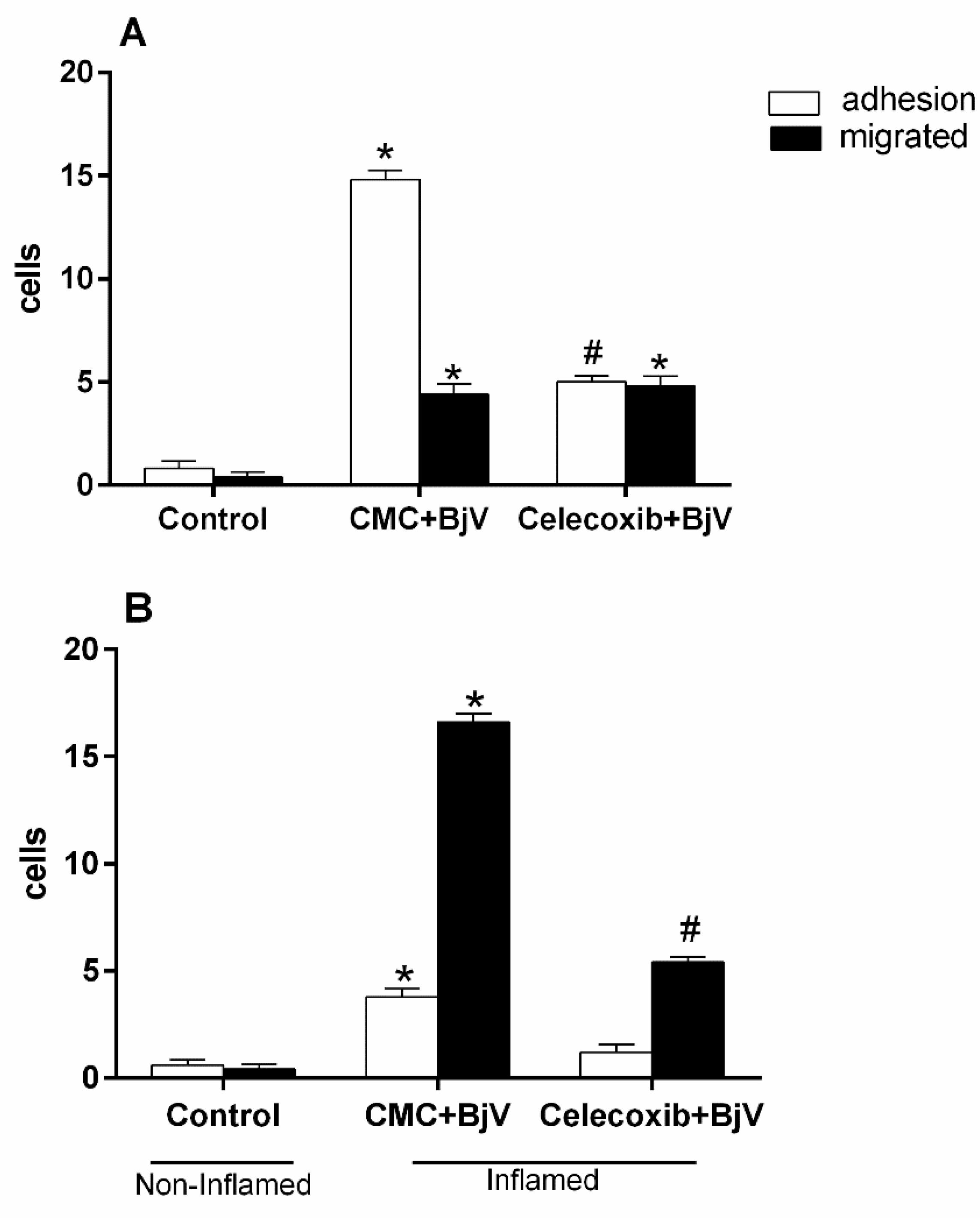

An investigation into the role of cyclooxygenase enzymes (COX) in microcirculation cellular events was also performed using indomethacin (Indo) or celecoxib, which blocks products coming from the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) pathway, 30 minutes before BjV was injected under the skin of mice's scrotums. Both drugs were efficient in inhibiting the number of adhered and migrated cells at both times evaluated (

Figure 2A and 2B and

Figure 3A and B).

Although celecoxib inhibited adhesion and migration events after 2 hours and 24 hours, respectively, it had no role in inhibiting migrated cells after 2 hours of exposure to the venom (

Figure 3A and

Figure 3B). The initial times of the leukocyte-endothelium interaction are predominantly cell adhesion, and in the later times, there is migration to the extravascular space since these interactions occur because of the expression of adhesion molecules that have sequential and orchestrated kinetics [

33,

34].

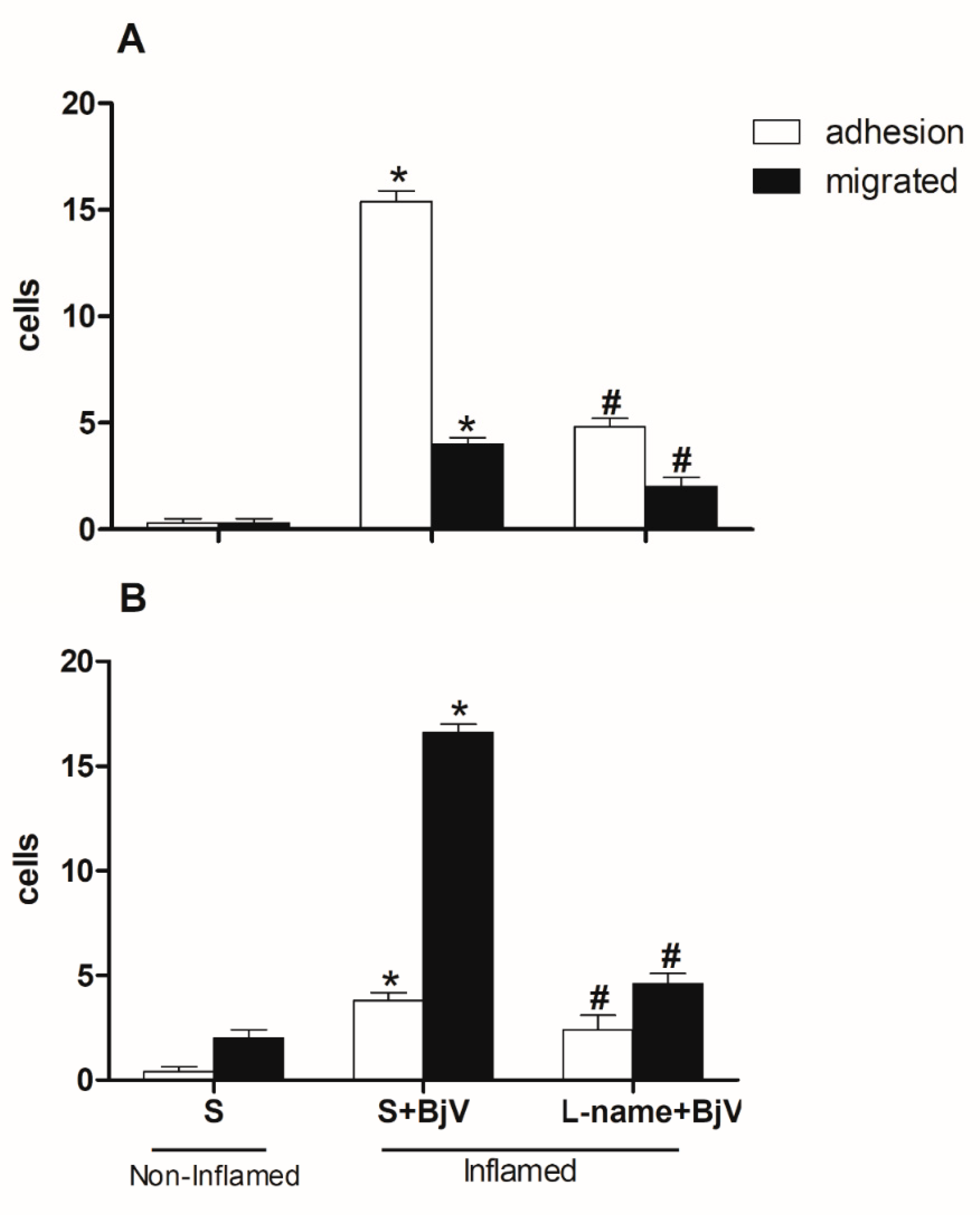

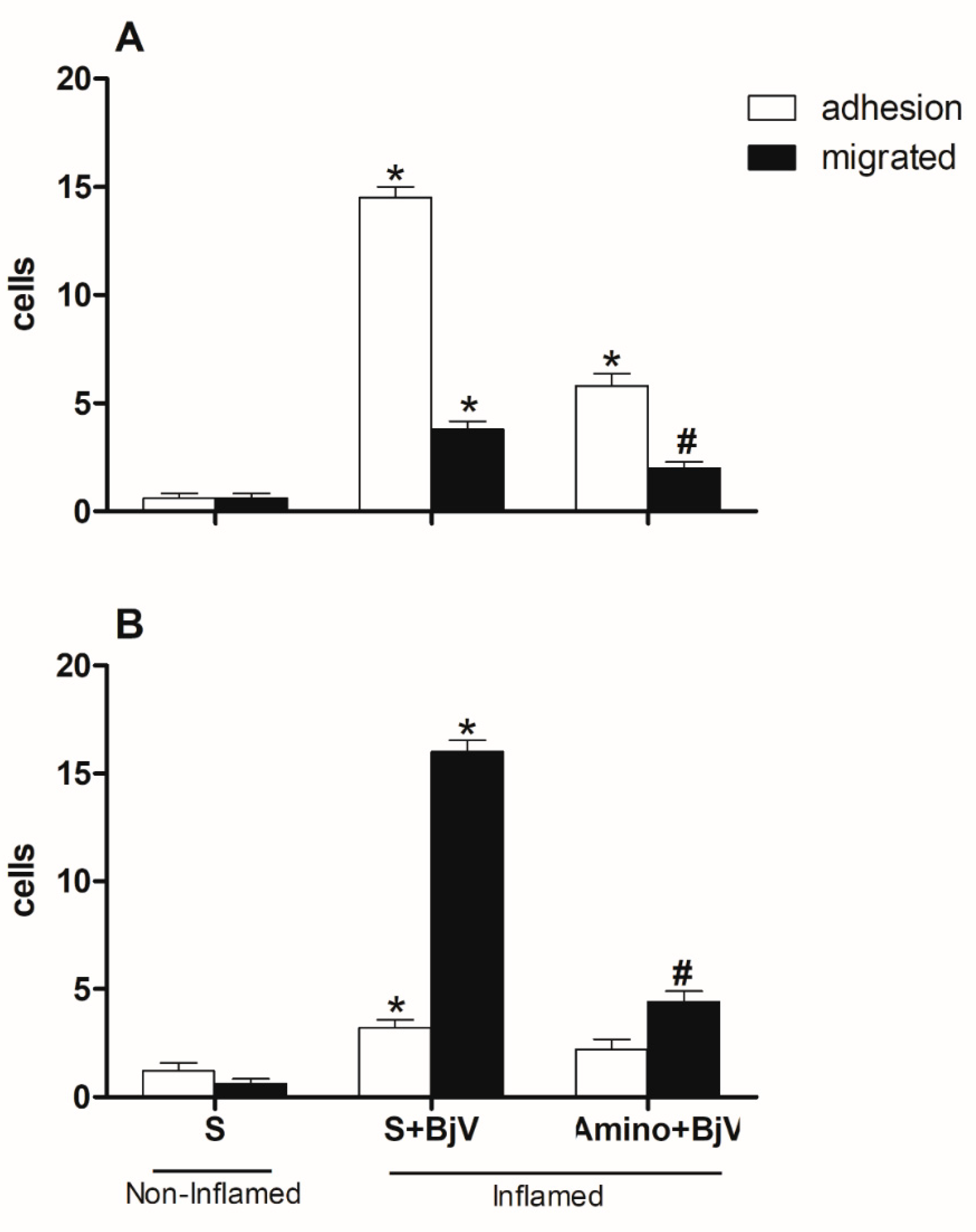

Other inhibitors that have been found effective in preventing microcirculation changes are those targeting the nitric oxide pathway. To determine their role in these changes, we gave mice L-NAME, which blocks nitric oxide synthase (NOS), or aminoguanidine, which blocks inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). This was done for 30 minutes before injecting BjV into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. Both inhibitors significantly reduced the number of adhered and migrated cells at 2 and 24 hours, as depicted in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

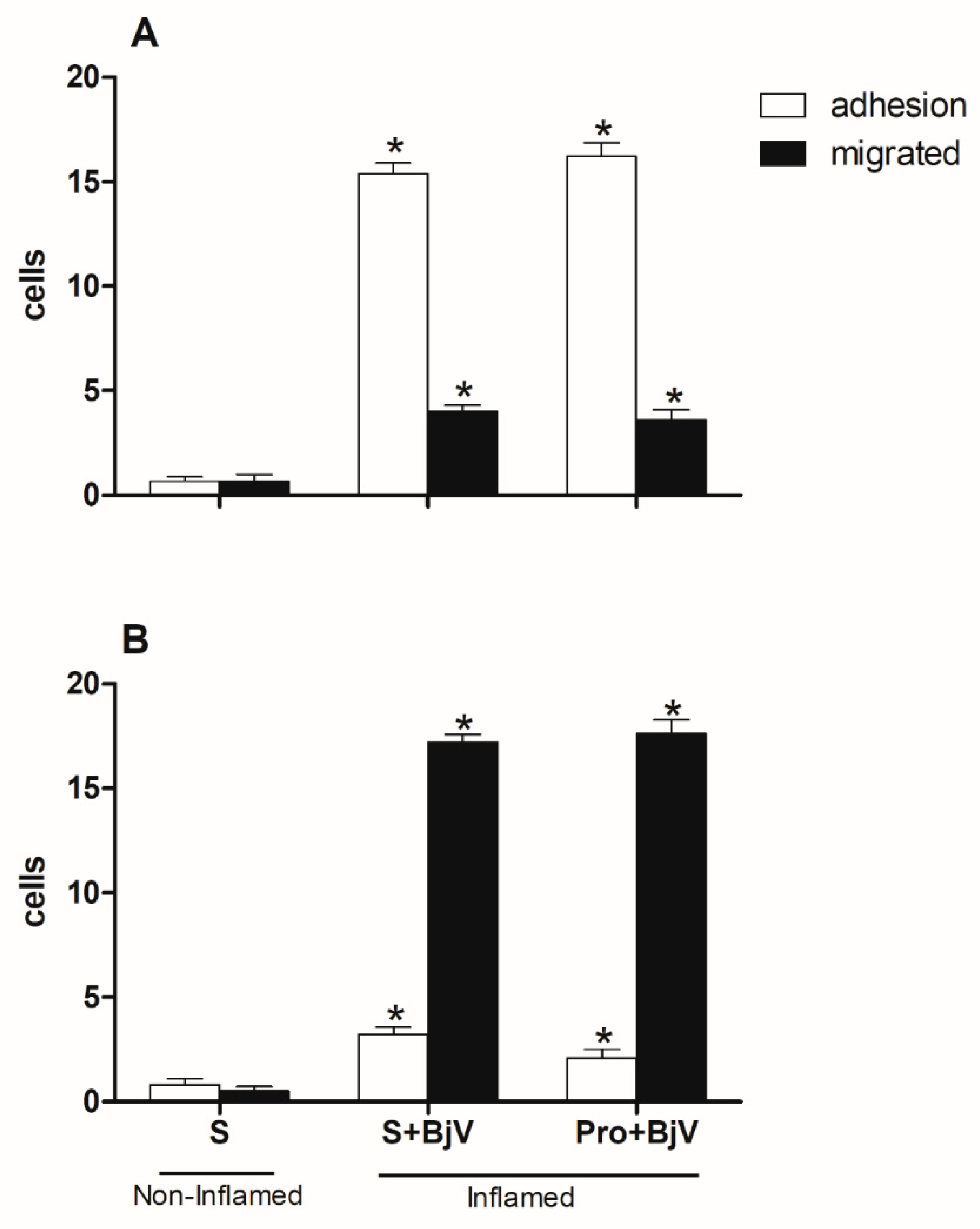

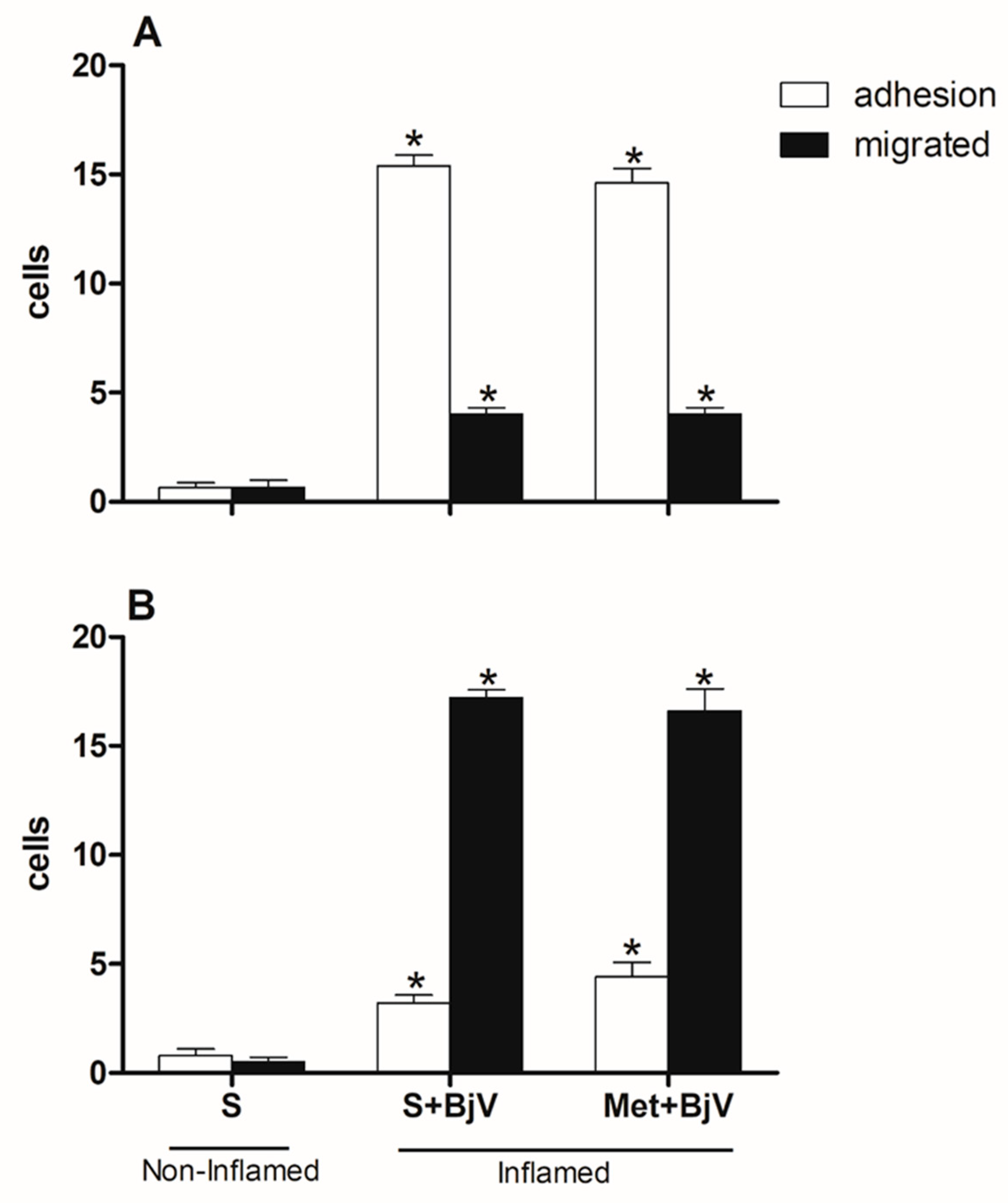

Using vasoactive amine inhibitors before the BjV treatment did not change the way the leukocytes and endothelium interacted. Cell adhesion and migration were not different in the groups that were first given promethazine (Pro), which blocks the histamine H1 receptor, or methysergide (Met), which blocks the serotonin (5-HT2) receptor. This was true at both time points studied (

Figure 6A and B,

Figure 7A and B).

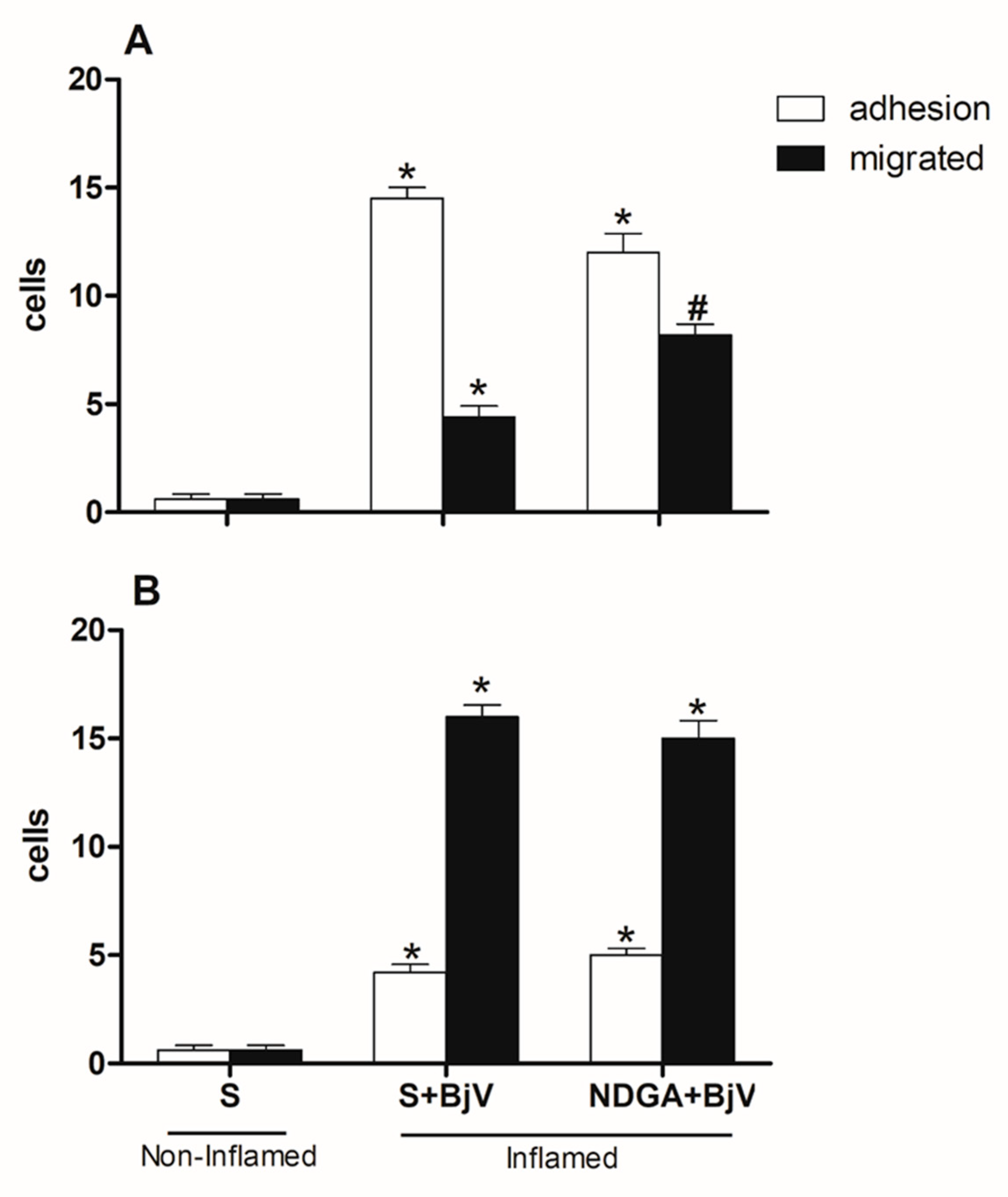

When the lipoxygenase pathway inhibitor NDGA was used first, there were no changes in the number of cells that stuck to or moved through the post-capillary venules (

Figure 8A and B).

All the drugs used per se did not cause significant changes in the leukocyte-endothelium interaction patterns (data not shown).

It was tested to see if dexamethasone could reverse the inflammatory effect that BjV causes by treating the mice with this drug an hour after BjV was injected under the skin in their scrotum. There were a lot fewer adherent cells after treatment with Dx compared to the group that was injected with venom, but there were no statistical differences between the Dx group and the control group (

Figure 9A). This decrease was also observed in the cell migration event after 24 hours when compared to the poisoned group (

Figure 9B).

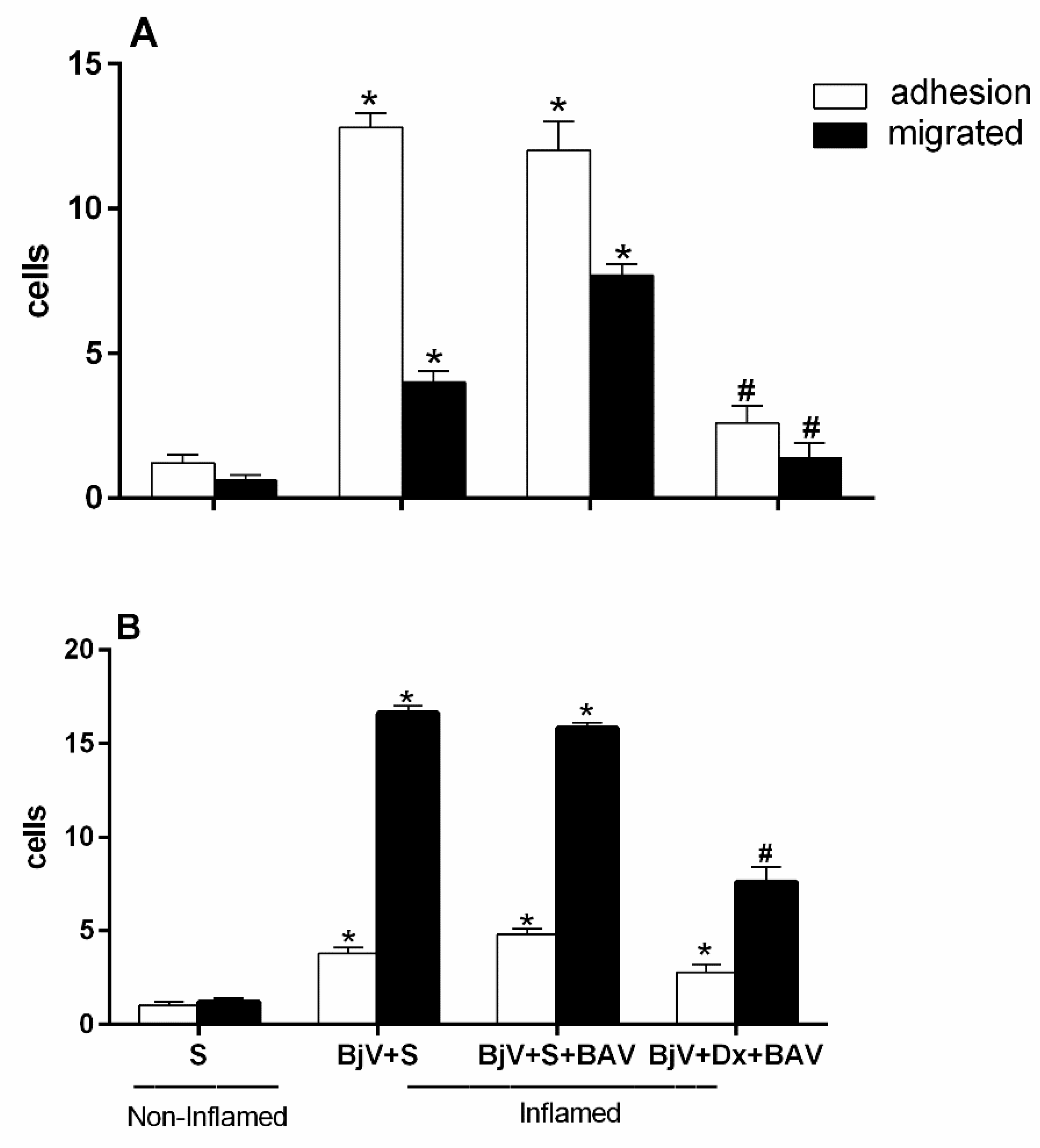

One hour after the BjV injection, treatment with antivenom (BAV) was done to see how well the antivenom stopped the changes that the venom caused in the interaction between leukocytes and endothelium. However, we found the antivenom could not stop the microcirculatory alterations. There was an increase in adhered and migrated cells at both assessed times—2 and 24 hours—as shown in

Figure 10A and

Figure 10B. This increase in changes in leukocyte-endothelium interactions did not differ from the envenomed group and with no treatment.

Figure 10A and

Figure 10B show that the group that was treated with BAV+Dx had fewer cells that stuck to and migrated. This means that the anti-inflammatory drug association lowers the number of white blood cells that are recruited even an hour after envenomation and the interactions between these cells and the endothelium.

4. Discussion

Using specific antitoxins is the only proven and recommended treatment by the World Health Organization for cases of snakebites [

6]. Since introducing antivenom treatment, there has been a significant decrease in the number of deaths caused by non-medical accidents [

14].

Despite the effectiveness of serotherapy in neutralizing systemic symptoms, local reactions induced by

Bothrops venom do not always respond to such treatment. This is because of the rapid manifestation of these local reactions and the fact that antivenom agents cannot reverse the already established or triggered lesions nor neutralize the endogenous mediators involved in the process [

10].

Bothrops venoms can induce inflammatory responses, activating signaling pathways that culminate in the transcription of inflammatory genes such as cytokines and eicosanoids, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), with consequent release of vasoactive substances and consequent increase in vascular permeability, activation of endothelial cells, expression of adhesion molecules, which will trigger capture, rolling, firm adherence and cell migration [

15,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

Previous studies of our group have shown the pro-inflammatory action of the

Bothrops jararaca snake venom [

25,

26] and that this action is because of the constituent metalloproteinases of the venom [

27]. We have recently shown that Jar, Jar-C, and BnP1, different Snake Venom Metalloproteinases, can induce adhesion and cell migration in post-capillary venules in the cremaster muscle of mice, observed by intravital microscopy [

39] and that the alterations in leukocyte-endothelium interaction occur because of the participation of the adhesive molecule ICAM-1 in early times and of PECAM-1, in later times [

34].

In the present study, we note that both the pre- and post-treatment with dexamethasone could decrease the number of adhered and migrated cells in the two times analyzed when compared with the control (non-envenomed) and with the BjV-inflamed group (

Figure 1 and

Figure 9), demonstrating the participation of arachidonic acid degradation metabolites and the ability of dexamethasone to reverse changes in leukocyte-endothelium interactions induced by the BjV.

The eicosanoids originating from the cyclooxygenase pathway, but not those originating in the lipoxygenase route, mediate the endothelial leukocyte interaction induced by BjV. Studies have shown the participation of products originating from eicosanoids in cell migration induced by the venom of

B. jararaca [

40]. Also, concerning the role of glucocorticoids in leukocyte recruitment, it has been described that glucocorticoids reduce cell recruiting to the site of inflammation by inhibition of adhesion molecules, as they induce a rapid change in the surface of the CAMs, by a genomic mechanism, or by interfering with the expression of the ICAM-I adherence molecule in the IL-1-induced leucocyte adherence in the mouse mesentery [

41,

42,

43]. It is known that the migration of inflammatory cells induced by

Bothrops venoms is mediated by eicosanoids and that this recruitment depends on the expression of adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1, LECAM-1, LFA-1, PECAM-1, but not MAC-1 [

40,

44,

45].

The expression of these adhesion molecules results in increased leukocyte-endothelium interaction, the first step before the process of inflammatory cell diapedesis [

46], and this may be reflected in the modifications of cellular events observed after BjV injection.

The results got with pre-treatment with indomethacin (cyclooxygenase pathway inhibitor) and celecoxib (COX-2-specific inhibitors) reinforce the importance of the participation of the cyclooxygenase route, COX-2 in mediating the leukocyte-endothelium interaction induced by BjV, since these drugs are quite effective in inhibiting the cellular events inducted by the venom, a significant decrease in adhered cells in the 2nd hour and migrated in the 24th hour was observed compared to the non-treated groups, injected with the venom.

These data corroborate the literature, where it has already been showed that the pre-treatment of animals with anti-inflammatory drugs, inhibitors of phospholipase A

2 and the COX pathway, results in a significant reduction in paw edema induced by

Bothrops venoms [

23,

24,

25,

32]. This participation was also observed in mice for cyclooxygenase pathway products and the isoform COX-2 [

47].

A body of research shows that nitric oxide (NO) plays a part in controlling the interaction between white blood cells and endothelium. It is possible to see more of these cellular events by blocking certain forms of the enzymes' endothelial (eNOS) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [

31,

49]. A study found that NOS inhibitors that do not target specific genes, like L-NAME, do not stop the production of ICAM-1, a molecule that helps white blood cells stick firmly to endothelium when lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or carrageenan is present [

49]. However, we found that cellular events in the cremaster microcirculation muscle of mice were significantly slowed down after they were pre-treated with L-NAME, a NOS inhibitor, and aminoguanidine, a selective iNOS isoform inhibitor. This shows that these substances play a role in the interaction between white blood cells and the endothelium.

When applied topically to the spermatic fascia of rats, the BjV induces changes in leukocyte-endothelium interaction [

50]. However, when the rats had been treated with L-NAME first, the number of rolling and adherent cells decreased [

51].

Bothrops atrox venom is also described as inducing serum NO levels [

52]. It is known that cytokines like INF-γ and TNF-α induce the expression of iNOS and that

Bothrops jararaca venom can induce the release of both these cytokines and NO [

53].

Different experimental conditions, administration routes, or inflammatory stimuli can determine opposing effects on NO expression, suggesting that this mediator often acts with an antagonistic action in relation to the inflammatory response [

51,

54].

As previously mentioned, the inflammatory reaction observed in BjV is because of the rapid action of the toxins in the venom and due to the rapid release of endogenous mediators. Therefore, we used other drugs to understand the mediators involved in the changes in microcirculation after Bothrops envenomation.

After injecting the animals with venom, the alterations in leukocyte-endothelium interaction did not change when promethazine, a histamine inhibitor, was given first. This suggests that this amine does not play a role in the interaction between leukocytes and endothelium caused by

Bothrops jararaca venom. Studies show that this mediator does not also play a role in mediating the paw edema that this venom causes in mice [

28,

33]. In rats, the participation of histamine in mediating this edema has been verified [

23].

In animals that had first received methysergide, there were no changes in the parameters of the leukocyte-endothelium interaction due to BjV. This also suggests that serotonin is not involved in this process.

Leukotrienes interact with neutrophil receptors on the leukocyte surface, which leads to chemotaxis and increased adhesion to endothelial cells, mainly through increased expression of β2 integrin [

55]. But giving animals NDGA, which blocks the lipoxygenase pathway, did not stop the release of leukotrienes. This suggests that the products of the lipoxygenase pathway are not involved in the BjV-caused mediation process. On the other hand, products derived from the lipoxygenase pathway participate in the venom-induced migration of

B. erythromelas and

B. alternatus [

44].

Pre- and post-treatment with BAV inhibited the formation of BjV-induced edema in mice [

25]. However, this inhibition was not observed in the group that received BAV 45 minutes after the BjV injection. This result shows that BAV neutralizes the formation of edema; however, this reduction is more efficient when it is administered soon after envenomation [

25]. Picolo et al. [

56] noted the same result and showed that BAV caused a decrease in edema just when administered before injecting

Bothrops jararaca venom into the rats' footpads.

Some studies suggest that the reason immunoglobulin therapy does not work to stop local lesions caused by

Bothrops venoms is because it is hard for the immunoglobulin to get to the site of the lesion [

57]. This would justify using only the Fab portion of total IgG in the treatment of snake envenomation [

58]. There is, however, no significant difference in the reduction of local lesions like edema, hemorrhage, and myonecrosis between animals treated with all three types of serum. This is true whether the serums contained total IgG, only the F (ab')2 portion, or even the Fab portion [

59,

60].

In our data, we showed that the use of dexamethasone was beneficial in inhibiting the cellular events of the leukocyte-endothelium interaction induced by BjV, not only compared to the control group but also when compared to the groups that received only treatment with BAV. The same decreases were observed in animals treated with the combination of dexamethasone and BAV, like what was observed in animals treated with dexamethasone alone at both times studied (

Figure 1 and

Figure 9). When injected directly into a vein without being diluted, BAV can increase the interaction between white blood cells and the endothelium. Antivenin contains the preservative phenol, primarily responsible for this effect [

26].

This association between dexamethasone and BAV accelerated edema regression and reduced muscle damage from

B. jararaca and

B. jararacussu venoms [

29], as well as swelling caused by

B. jararaca venom [

25]. When

B. atrox venom is the cause of tissue damage, the combination of this corticosteroid with antivenom is also beneficial, reducing inflammation and accelerating muscle regeneration [

21].

A recent study on people who had been envenomed showed that giving anti-inflammatory drugs along with antivenom reduced the local effects of snakebites, including inflammatory symptoms [

61]. However, treatment with dexamethasone, alone or combined with antivenom, could not prevent, or reduce hemorrhagic damage induced by this venom [

21,

32]. This outcome is in line with the hypothesis that eicosanoids are not involved in the pharmacological mechanisms causing local hemorrhage brought on by

Bothrops jararaca venom.

It is known that BjV does not induce the secretion of endogenous corticosteroids or stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis [

62]. In this sense, the use of dexamethasone would be important to avoid inflammatory reactions; however, this corticosteroid does not alter the local hemorrhagic and coagulant activities of BjV and does not indicate its use as a replacement for antivenom. When dexamethasone is associated with BAV, it may help treat

Bothrops jararaca envenomation better by lowering the inflammatory response (swelling and leukocyte influx) faster among people whom this snake has bitten.

The inefficiency attributed to the antivenin described above encourages studies of complementary therapies. In this sense, the association of anti-inflammatory drugs with serum in treating local inflammatory reactions present in Bothrops jararaca envenomation would be a rational alternative, which should be clinically tested.

Figure 1.

Effect of pre-treatment with dexamethasone (Dx) on the interaction between white blood cells and endothelium in post-capillary venules in the microcirculation of mouse cremaster muscle triggered by BjV. The animals received treatment with dexamethasone (Dx, 1.0 mg/kg) or saline (S) 1 hour before the injection of BjV (1μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of BjV injection, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at how cells adhered and moved. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group. #p<0.05 compared to the control group, and the group injected with BjV.

Figure 1.

Effect of pre-treatment with dexamethasone (Dx) on the interaction between white blood cells and endothelium in post-capillary venules in the microcirculation of mouse cremaster muscle triggered by BjV. The animals received treatment with dexamethasone (Dx, 1.0 mg/kg) or saline (S) 1 hour before the injection of BjV (1μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of BjV injection, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at how cells adhered and moved. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group. #p<0.05 compared to the control group, and the group injected with BjV.

Figure 2.

Effect of pretreatment with indomethacin (Indo) on the interaction between white blood cells and endothelium in postcapillary venules in the microcirculation of mouse cremaster muscle triggered by BjV. The animals received treatment with indomethacin (Indo, 3 mg/kg) or saline (S) 30 minutes before the injection of BjV (1μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of BjV injection, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at how cells adhered and moved. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group. #p<0.05 compared to the control group, and the group injected with BjV.

Figure 2.

Effect of pretreatment with indomethacin (Indo) on the interaction between white blood cells and endothelium in postcapillary venules in the microcirculation of mouse cremaster muscle triggered by BjV. The animals received treatment with indomethacin (Indo, 3 mg/kg) or saline (S) 30 minutes before the injection of BjV (1μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of BjV injection, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at how cells adhered and moved. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group. #p<0.05 compared to the control group, and the group injected with BjV.

Figure 3.

The impact of pre-treatment with celecoxib on the interaction between white blood cells and endothelium in post-capillary venules in the microcirculation of mouse cremaster muscle triggered by BjV. The animals received treatment with celecoxib (30 mg/kg) or carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) 30 minutes before the injection of BjV (1μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of BjV injection, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at how cells adhered and moved. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group. #p<0.05 compared to the control group, and the group injected with BjV.

Figure 3.

The impact of pre-treatment with celecoxib on the interaction between white blood cells and endothelium in post-capillary venules in the microcirculation of mouse cremaster muscle triggered by BjV. The animals received treatment with celecoxib (30 mg/kg) or carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) 30 minutes before the injection of BjV (1μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of BjV injection, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at how cells adhered and moved. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group. #p<0.05 compared to the control group, and the group injected with BjV.

Figure 4.

The impact of pretreatment with L-NAME on the interaction between white blood cells and endothelium in post-capillary venules in the microcirculation of mouse cremaster muscle triggered by BjV. The animals received treatment with L-NAME (100 mg/kg) or saline (S) 30 minutes before the injection of BjV (1 μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of BjV injection, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at how cells adhered and moved. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group. #p<0.05 compared to the control group and the group injected with BjV.

Figure 4.

The impact of pretreatment with L-NAME on the interaction between white blood cells and endothelium in post-capillary venules in the microcirculation of mouse cremaster muscle triggered by BjV. The animals received treatment with L-NAME (100 mg/kg) or saline (S) 30 minutes before the injection of BjV (1 μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of BjV injection, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at how cells adhered and moved. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group. #p<0.05 compared to the control group and the group injected with BjV.

Figure 5.

Effect of pre-treatment with aminoguanidine (Amino) on the interaction between white blood cells and endothelium in post-capillary venules in the microcirculation of mouse cremaster muscle triggered by BjV. The animals received treatment with aminoguanidine (Amino, 50 mg/kg) or saline (S) 30 minutes before the injection of BjV (1 μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of BjV injection, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at how cells adhered and moved. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group. #p<0.05 compared to the control group, and the group injected with BjV.

Figure 5.

Effect of pre-treatment with aminoguanidine (Amino) on the interaction between white blood cells and endothelium in post-capillary venules in the microcirculation of mouse cremaster muscle triggered by BjV. The animals received treatment with aminoguanidine (Amino, 50 mg/kg) or saline (S) 30 minutes before the injection of BjV (1 μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of BjV injection, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at how cells adhered and moved. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group. #p<0.05 compared to the control group, and the group injected with BjV.

Figure 6.

Effect of pre-treatment with promethazine (Pro) on the leukocyte-endothelium interaction in post-capillary venules in the microcirculation of mouse cremaster muscle induced by BjV. The animals received treatment with promethazine (Pro, 10 mg/kg) or saline (S) 30 minutes before the injection of BjV (1μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of BjV injection, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at how cells adhered and moved. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group.

Figure 6.

Effect of pre-treatment with promethazine (Pro) on the leukocyte-endothelium interaction in post-capillary venules in the microcirculation of mouse cremaster muscle induced by BjV. The animals received treatment with promethazine (Pro, 10 mg/kg) or saline (S) 30 minutes before the injection of BjV (1μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of BjV injection, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at how cells adhered and moved. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group.

Figure 7.

Effect of pre-treatment with methysergide (Met) on the leukocyte-endothelium interaction in post-capillary venules in the microcirculation of mouse cremaster muscle induced by BjV. The animals received treatment with methysergide (Met, 0.8 mg/kg) or saline (S) 30 minutes before the injection of BjV (1μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of BjV injection, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at how cells adhered and moved. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group.

Figure 7.

Effect of pre-treatment with methysergide (Met) on the leukocyte-endothelium interaction in post-capillary venules in the microcirculation of mouse cremaster muscle induced by BjV. The animals received treatment with methysergide (Met, 0.8 mg/kg) or saline (S) 30 minutes before the injection of BjV (1μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of BjV injection, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at how cells adhered and moved. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group.

Figure 8.

Effect of pretreatment with nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) on the leukocyte-endothelium interaction in postcapillary venules in the microcirculation of mouse cremaster muscle induced by BjV. The animals received treatment with NDGA (30 mg/kg) or saline (S) 30 minutes before the injection of BjV (1 μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. The cremaster muscle was exposed 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) after being injected with BjV, and intravital microscopy was used to look at cellular events like adhesion and migration. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group. #p<0.05 compared to the control group and the group injected with BjV.

Figure 8.

Effect of pretreatment with nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) on the leukocyte-endothelium interaction in postcapillary venules in the microcirculation of mouse cremaster muscle induced by BjV. The animals received treatment with NDGA (30 mg/kg) or saline (S) 30 minutes before the injection of BjV (1 μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. The cremaster muscle was exposed 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) after being injected with BjV, and intravital microscopy was used to look at cellular events like adhesion and migration. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p < 0.05 compared to the control group. #p<0.05 compared to the control group and the group injected with BjV.

Figure 9.

Effect of post-treatment with dexamethasone (Dx) on leukocyte-endothelium interaction in post-capillary venules in the muscular microcirculation of the mouse cremaster induced by BjV. The animals received treatment with dexamethasone (Dx, 1.0 mg/kg) or saline (S) 1 hour after injection of BjV (1μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of envenomation, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at cellular events like adhesion and migration. Results are presented as means ± SEM. (n = 5). *p< 0.05 compared to the control group; #p<0.05 compared to other groups.

Figure 9.

Effect of post-treatment with dexamethasone (Dx) on leukocyte-endothelium interaction in post-capillary venules in the muscular microcirculation of the mouse cremaster induced by BjV. The animals received treatment with dexamethasone (Dx, 1.0 mg/kg) or saline (S) 1 hour after injection of BjV (1μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of envenomation, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at cellular events like adhesion and migration. Results are presented as means ± SEM. (n = 5). *p< 0.05 compared to the control group; #p<0.05 compared to other groups.

Figure 10.

Effect of combining treatment with dexamethasone and Bothrops antivenom (BAV) on the interaction between endothelium and white blood cells in the cremaster muscle post-capillary venules of mice injected with BjV. The animals received treatment with dexamethasone (Dx, 1.0 mg/kg i.p.), BAV (200 μL, i.v.) or saline (i.v. or i.p.), 1h after injection of BjV (1μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of envenomation, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at cellular events like adhesion and migration. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p< 0.05 compared to the control group; #p<0.05 compared to the other groups.

Figure 10.

Effect of combining treatment with dexamethasone and Bothrops antivenom (BAV) on the interaction between endothelium and white blood cells in the cremaster muscle post-capillary venules of mice injected with BjV. The animals received treatment with dexamethasone (Dx, 1.0 mg/kg i.p.), BAV (200 μL, i.v.) or saline (i.v. or i.p.), 1h after injection of BjV (1μg/100 μL) or saline (S) into the subcutaneous tissue of the scrotum. After 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) of envenomation, the cremaster muscle was exposed, and intravital microscopy was used to look at cellular events like adhesion and migration. The results are presented as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *p< 0.05 compared to the control group; #p<0.05 compared to the other groups.