Introduction

Glaucoma describes a group of diseases characterized by damage to the optic nerve and retinal nerve fiber layer. It is a chronic progressive optic neuropathy that causes peripheral and eventually central vision loss if not treated. It is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide [1]. The number of people affected by glaucoma is anticipated to continue to rise as the population ages. It is estimated that approximately 3 million people in the US currently have glaucoma, and this number is expected to grow to 6.3 million by 2050 [2]. Globally, it is estimated that 76 million people suffer from glaucoma with a projected growth to 112 million by 2040 [2]. With such stark projections, it is clear that developments in therapeutics will need to progress in order to optimize patient care and clinical outcomes. Additionally, glaucoma disproportionately affects Black populations in the US. It is the most common cause of irreversible blindness in Black persons with a prevalence of 6.1% [2]. The prevalence in Latino communities is second highest at 4.1%, followed by Asian Americans at 3.5% and non-Hispanic White persons at 2.8% [2]. These statistics point to a need to increase the screening and access to care for persons from historically medically underserved communities.

There is currently no cure for glaucoma. Intraocular pressure (IOP) is the only known modifiable risk factor and therefore of the utmost importance in controlling disease progression. However, in many patients intraocular pressure is only slightly elevated or still within the normal range [1]. The rise in pressure associated with glaucoma can be painless and is often unnoticeable to the patient until subsequent symptoms are present. Early detection is extremely important because any visual field loss noticed by the patient is irreversible. Other general risk factors include older age, race and ethnicity, and family history of glaucoma.

All pharmacologic therapeutics used to treat glaucoma work by lowering intraocular pressure. The common goal is to decrease the loss of ganglion cells, thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer, and cupping of the optic disc to slow progression. There are a variety of medications used today that work through several different mechanisms. These include cholinergic agents, alpha adrenergic agonists, beta blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, nitric oxides, prostaglandin analogs, and rho-kinase inhibitors.

I. What is Glaucoma?

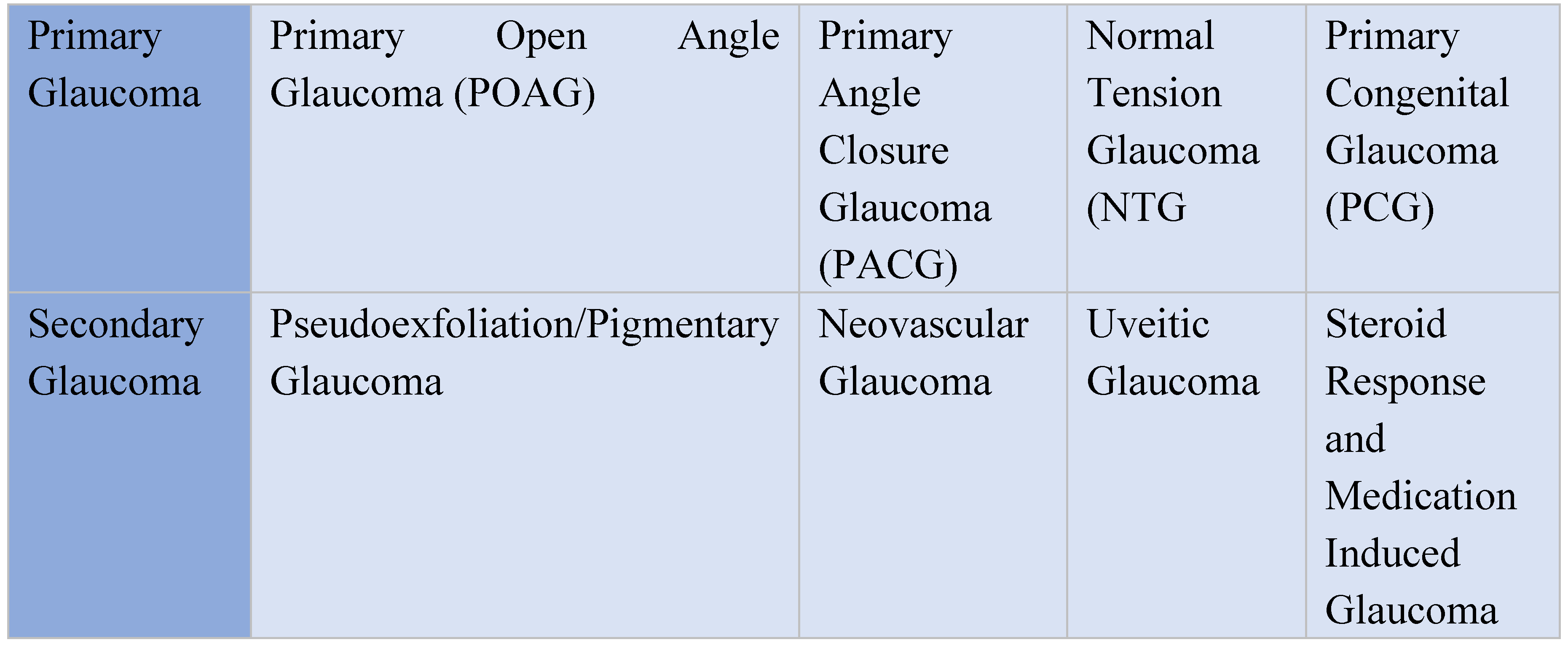

The term “glaucoma” encompasses a group of diseases each presenting with different characteristics and standards of treatment. There are 2 major types of glaucoma, primary and secondary. The 2 major subtypes that exist are open angle and closed angle glaucoma. The most common type is primary open angle glaucoma [2]. Although primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most commonly seen form of the disease, it is important to understand the other frequently observed manifestations in order to properly distinguish and treat them. It is also essential to understand the racial and ethnic disparities that exist in glaucoma to prevent, treat, and understand this disease.

Primary Open Angle Glaucoma

Primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most common form of glaucoma. POAG affects more than 2 million Americans, and many people who do not even know that they have this disease [16]. It is largely asymptomatic and gradually reduces the visual field of the affected patient. In most cases, POAG vison loss starts in the periphery and moves toward the central vision. If left untreated, it can result in permanent blindness. There are a multitude of risk factors that can cause primary open angle glaucoma, including older age, race and ethnicity, family history, history of diabetes, hypertension, migraines, trauma, steroid migraines and it is evident that genetics likely playing a role. The pathophysiology of POAG centers on the effects of elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) in the eye. However, ophthalmic evaluation and diagnostic testing both factor into a clinical diagnosis. There are numerous options for pharmacologic treatment of POAG. As there is no cure for the disease, the most common clinical strategy is to manage intraocular pressure with a goal of decreasing progression and reducing the risk of visual field loss. Treatment may include medication, laser and incisional surgery or a combination

Normal Tension Glaucoma

Normal tension glaucoma (NTG) is a progressive optic neuropathy that is very similar to primary open angle glaucoma. However, it is characterized by an intraocular pressure that falls within the normal range. This includes a value between 10-21 mm Hg [4]. The existence of normal tension glaucoma emphasizes the importance of diagnosis based on the condition of the optic nerve and not simply a single risk factor such as elevated intraocular pressure. The complex etiology of normal tension glaucoma is not well understood. Some theories include differences in nocturnal systemic hypotension, autonomic dysfunction, obstructive sleep apnea, blood rheology impairment, and intracranial pressure [4]. Some observed differences between normal tension glaucoma and primary open angle glaucoma worth noting include larger optic cups in NTG patients, macular ganglion cell differences, and thicker lamina cribrosa in NTG than in POAG patients [4]. Medical treatment often includes intraocular pressure lowering agents.

Primary Angle Closure Glaucoma

Primary angle closure glaucoma (PACG) is another significant form of glaucoma. It induces disease differently than primary open angle glaucoma due to differences in the anatomical structure of the eye. It is characterized by an elevation in intraocular pressure as a result of mechanical obstruction of the trabecular meshwork of the eye. This can be due to anatomical apposition of the iris at the trabecular meshwork or a synechial closed angle [5]. A fundamental difference between POAG and PACG is that angle closure is the significant problem in PACG leading to elevated IOP. Open angle remains more prevalent than angle closure as it is estimated that 5.9 million people experience bilateral blindness worldwide from POAG compared to 5.3 million people with PACG [5]. Primary angle closure glaucoma can be further divided into acute and chronic PACG. This is simply based on the suddenness of onset of the disease and is important in clinical management. Acute PACG will occur rapidly with the iris completely covering the trabecular meshwork, resulting in a spike in IOP [5]. This needs to be managed quickly. This can be managed by conventional therapy, laser surgery or incisional surgeries such as trabeculectomy and cataract surgery. Medications such as Pilocarpine is able to induce miosis and pull the peripheral iris away from the trabecular meshwork to combat a mild acute attack [6]. Chronic PACG is a slower process. It is similar to POAG in that it often occurs quietly and painlessly, as the eye is able to adjust to the slow rise in IOP [5]. Early detection can slow or halt this process. Some forms of treatment of PACG that have proven effective include laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI) and cataract extraction [5].

Primary Congenital Glaucoma

The last major variation of glaucoma is primary congenital glaucoma (PCG). As the name implies, this form of disease is inherited early in life. It is a significant cause of global pediatric visual impairment and can often lead to permanent blindness [7]. What differentiates primary congenital glaucoma from other forms of glaucoma is its heritability and development in patients below the age of 3. The underlying mechanism in PCG is the development of an obstruction that prevents adequate drainage of aqueous humor caused by abnormalities in the trabecular meshwork and anterior chamber angle [8]. This will increase intraocular pressure and lead to optic nerve damage. Current evidence suggests that this abnormality in the trabecular meshwork can be linked to a mutation that impairs its normal development. Children with congenital glaucoma typically present with enlargement of the globe of the eye and corneal opacification [8]. Additionally, these children may present with reduced visual acuity and visual field restrictions. PCG is a rare disease and only occurs in 10-20,000 live births in Western countries like Ireland, Britain, and the United States [8]. It often requires surgical treatment, but can be treated medically in certain clinical situations. The goal of medical treatment is usually to preserve visual function by lowering intraocular pressure while surgery is arranged, between multiple surgeries, or after the result of surgical procedures. The most commonly used medications include beta blockers and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Early detection is vital to decrease the potential of permanent visual loss. The surgeries can include Trabeculotomy, Goniotomy, Trabeculectomy or Tube implantation

Pseudoexfoliation and Pigmentary Glaucoma

Secondary glaucomas comes in a variety of different forms and are distinguished by a clinically identifiable cause for increase in intraocular pressure. They can be traumatic or medical. The most common of which is pseudoexfoliation glaucoma [9]. This type of glaucoma is characterized by the buildup of abnormal extracellular matrix material in the outflow pathway that leads to an increase in IOP [9]. It is a disorder that can have numerous ocular and systemic consequences. The fibrillar deposits occur on the surface of the lens and iris and can be detected by biomicroscopy. Pseudoexfoliation glaucoma is very rare in people under the age of 65, however, it has a 5% prevalence in people aged 75-85 in the United States [9]. There is a strong genetic factor in developing this type of glaucoma in addition to many environmental causes, such as exposure to ultraviolet light [9]. Pigmentary glaucoma is often grouped with pseudoexfoliation glaucoma as both forms are the result of material inside the eye blocking the outflow of aqueous humor. The differences, however, with pigmentary glaucoma are that (1) the debris is made up of pigment from the iris [10]; (2) it occurs at an earlier age; and (3) it affects males to a greater extent than it does females.

Neovascular and Uveitic Glaucoma

Neovascular and uveitic glaucoma are other major forms of secondary disease. Neovascular glaucoma is usually a result of complications from other diseases such as diabetic retinopathy, retinal vascular occlusions, or carotid artery obstructive disease. These can lead to retinal ischemia and the release of proangiogenic factors that cause neovascularization and disrupt aqueous humor outflow [9]. Like other forms of glaucoma, this disruption of aqueous humor outflow is likely to increase intraocular pressure. A combination of medical and surgical therapy is often required for treatment. Uveitic glaucoma is the result of another condition – uveitis. This subtype is a complex condition defined as glaucoma resulting from an elevated IOP in a uveitic patient with optic nerve damage and visual field loss [11]. Treatment of both intraocular inflammation and glaucoma at the same time presents a significant challenge. Depending on the course of the glaucoma, a combination of IOP lowering medications, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and corticosteroids will typically play a role. A combination of medication and surgical intervention maybe necessary to treat this disease. The underlying causes in both diseases must be treated in order to control the secondary glaucoma

Steroid Response and Medication Induced Glaucoma

Lastly, steroid response and medication induced glaucoma share a similar etiology. It is important to note that chronic corticosteroid use can in some cases cause an increase in intraocular pressure. This is most common with topical ophthalmic or systemic steroid use, but can also be observed as a result of dermal, inhaled, nasal, and intra-articular application [9]. Some medications can induce angle closure glaucoma by mechanisms such as pupillary block and idiosyncratic reactions [9]. Adrenergic agonists and anticholinergic drugs can block the outflow of aqueous humor and induce acute angle closure. Sulfonamide agents and anhydrase inhibitors can in some cases lead to edema in the ciliary body and forward displacement of the lens and iris [9]. Quick identification and removal of the problematic agents, along with IOP lowering medication are critical steps to prevent vison loss.

Figure 1.

Types of Glaucoma.

Figure 1.

Types of Glaucoma.

III. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Glaucoma

Disparities in healthcare exist across a wide range of diseases and medical conditions. It is important to acknowledge racial and ethnic disparities when reviewing a specific disease in order to promote awareness and improve patient outcomes. Members of minority groups in the United States often have less access to and receive lower quality medical care than White Americans. They also have lower rates of representation in clinical studies than White Americans and access to fewer healthcare providers. This presents a significant problem in the treatment of glaucoma and other diseases. The standard treatment for primary open angle glaucoma is reducing intraocular pressure. Therefore, it is critically important to adhere to medical and surgical appointments and to follow therapeutic regiments in order to increase clinical outcomes. Black and Latino racial and ethnic patient status has been shown to be an independent risk factor for inconsistent follow up visits at appointments and lower rates of glaucoma testing. Cost, health literacy, and access to screening are some of the greatest obstacles that Black and Latino patients face with respect to glaucoma [12] [13]. Another factor that could add to this disparity is that less than 2% of ophthalmologists in the United States identify as Black or Latino [12]. This has the potential to negatively affect patient interactions, trust, communication, and satisfaction.

Globally, it is estimated that 76 million people suffer from glaucoma with a projected jump to 112 million by 2040 [2]. This number indicates the importance of studying this disease and continuing to search for therapeutics that can improve patient outcomes. This involves improving racial and ethnic diversity in study participants. Glaucoma has been shown to affect Black and Latino populations at a significantly higher rate than White populations in the United States. It is reported that this disease is 7 times more likely to cause blindness in Black individuals when compared with White individuals, and 15 times more likely to cause visual impairment in Black individuals than White individuals [14]. Primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most common form of glaucoma. Additional statistics indicate that Black individuals have a higher prevalence rate of POAG than White individuals in the United States. Black persons have the highest rate at 3.4% while White persons have a rate of 1.7% [14]. Additionally, increasing the diversity of clinical study participants will help with understanding how to better improve clinical outcomes for Black and Latino populations. Between 1994 and 2019, White participants made up 70.7% of study populations, while Black participants made up only 16.8% and Latino individuals only 3.4% [14]. It has been theorized that there could be genetic variants associated with the increased rate of glaucoma in Black populations as well as medication adherence. However, previous observational studies have proven to be inconclusive [14]. It is commonly agreed that further research is needed to study the genetic mechanisms of primary open angle glaucoma by a more diverse populations and a more diverse group of geneticists. Research in the association of genetics to medication adherence is also an area that is currently been explored. The Polygenetic risk score and other glaucoma risk assessment scores that are currently been researched and developed may hold a significant answer into early screening, early diagnosis and treatment of this devastating disease (18).

Although more genetic studies into POAG disparities in race and ethnicity need to be performed, it is clear that socioeconomic status plays a central role in these epidemiologic differences. Socioeconomic status is a social determinant of health and it is commonly understood that racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States experience more socioeconomic disadvantages when compared to White individuals [14]. As socioeconomic disadvantages increase, the use of eye care services for age related diseases decreases [15]. Minority populations in the United States are underserved and over-affected by POAG. Access to medical services, healthcare literacy, glaucoma screening and diversity in clinical trials must improve in order to observe changes in the disparities that exist in glaucoma care.

IV. Treatment and Prevention

Despite current knowledge of risk factors, genetics, and pathophysiology, the only medical form of treatment for primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) today remains to be intraocular pressure lowering medications. There is currently no cure for POAG. The goals of treatment are to delay the progression of visual field loss for the duration of the patient’s lifetime. There are a variety of medications used today that work through several different mechanisms. These include cholinergic agents, alpha adrenergic agonists, beta blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, nitric oxides, prostaglandin analogs, and rho-kinase inhibitors. In particular cases however, surgical procedures are recommended. Microinvasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) are the most recently developed procedures used in surgically treating glaucoma. Most MIGS work by dilating, cleaving open, or bypassing tissue that is obstructing aqueous outflow, or by inserting a device into an outflow structure to increase drainage [2]. Each procedure comes with its own set of risks. Many MIGS are performed with cataract surgery and has been shown to be very effective treatments by lowering intraocular pressure and decreasing the medication burden on patients. Often, a combination of surgery and pharmacotherapeutic treatment can improve patient outcomes.

The best way to prevent irreversible visual field loss from glaucoma is to discover it in its early stages. With early observation and tools such as the polygenetic risk score (20), eye care providers will be able to monitor the factors that contribute to a diagnosis of glaucoma. They will seek to treat the intraocular pressure through medications, laser, or surgery in order to slow or halt disease progression. As a general rule, it is important to visit an eye care provider to get screened for glaucoma and other ocular diseases, this is especially necessary for those over the age of 65. However, the frequency of recommended screening varies based on risk factors like age, race, ethnicity, and family history. Awareness of one’s family medical history is a crucial aspect of preventing highly heritable diseases like glaucoma. Other ways to prevent glaucomatous damage include regular visits to a primary care physician, diligence with adhering to safety recommendations like eye protection when working with power tools, and following prescription medication instructions from an eye care provider. Pharmacologic therapy is an effective treatment for glaucoma because it works on a modifiable risk factor like intraocular pressure. Other modifiable environmental risk factors like lifestyle, exercise, and nutrition may play a role in glaucoma pathogenesis. Smoking cessation, moderate aerobic exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, consuming a balanced diet containing leafy greens, omega fatty acids, tea, and coffee may help prevent glaucoma or slow its progression [3]. Prevention is the best form of treatment, following these recommendations can help reduce the potential for loss of vision due to glaucoma.

Conclusion

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible vision loss worldwide. With an estimated 76 million people currently affected by this disease and a projected growth to 112 million by 2040, it is clear that we need to increase our vigilance in screening and diagnosis. This is especially true for Black and Latino patients which have an increased risk of glaucoma compared to White populations. It is essential to understand the different presentations of glaucoma in order to best diagnose and treat patients. Primary open angle glaucoma remains the most common form of disease. The utilization of systemic and topical medications offers the least invasive options for treatment, followed by laser and surgical techniques. A combination of laser or surgery with medical therapy typically allows for the most efficacious treatment. However, symptoms and severity of glaucoma varies and personalized care offers the best patient outcomes. Increasing awareness, promoting screening and prevention in the primary care setting, and improving research on pharmacologic therapies will contribute to lower rates of ocular nerve damage and visual field loss in vulnerable populations.

References

- Jonas, J.B., et al., Glaucoma. Lancet, 2017. 390(10108): p. 2183-2193. [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.D., A.P. Khawaja, and J.S. Weizer, Glaucoma in Adults—Screening, Diagnosis, and Management: A Review. JAMA, 2021. 325(2): p. 164-174. [CrossRef]

- Perez, C.I., K. Singh, and S. Lin, Relationship of lifestyle, exercise, and nutrition with glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 2019. 30(2): p. 82-88. [CrossRef]

- Esporcatte, B.L. and I.M. Tavares, Normal-tension glaucoma: an update. Arq Bras Oftalmol, 2016. 79(4): p. 270-6. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., et al., Primary angle closure glaucoma: What we know and what we don't know. Prog Retin Eye Res, 2017. 57: p. 26-45. [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.P., J.C. Pang, and C.C. Tham, Acute primary angle closure-treatment strategies, evidences and economical considerations. Eye (Lond), 2019. 33(1): p. 110-119. [CrossRef]

- Mocan, M.C., A.A. Mehta, and A.A. Aref, Update in Genetics and Surgical Management of Primary Congenital Glaucoma. Turk J Ophthalmol, 2019. 49(6): p. 347-355. [CrossRef]

- Badawi, A.H., et al., Primary congenital glaucoma: An updated review. Saudi J Ophthalmol, 2019. 33(4): p. 382-388. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.M. and A.P. Tanna, Glaucoma. Med Clin North Am, 2021. 105(3): p. 493-510. [CrossRef]

- Okafor, K., K. Vinod, and S.J. Gedde, Update on pigment dispersion syndrome and pigmentary glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 2017. 28(2): p. 154-160. [CrossRef]

- Kalogeropoulos, D. and V.C. Sung, Pathogenesis of Uveitic Glaucoma. J Curr Glaucoma Pract, 2018. 12(3): p. 125-138. [CrossRef]

- Siegfried, C.J. and Y.B. Shui, Racial Disparities in Glaucoma: From Epidemiology to Pathophysiology. Mo Med, 2022. 119(1): p. 49-54.

- Pleet, A., et al., Risk Factors Associated with Progression to Blindness from Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma in an African-American Population. Ophthalmic Epidemiol, 2016. 23(4): p. 248-56. [CrossRef]

- Allison, K., D.G. Patel, and L. Greene, Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open, 2021. 4(5): p. e218348. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., et al., Socioeconomic disparity in use of eye care services among US adults with age-related eye diseases: National Health Interview Survey, 2002 and 2008. JAMA Ophthalmol, 2013. 131(9): p. 1198-206. [CrossRef]

- Sharts-Hopko, N.C. and C. Glynn-Milley, Primary open-angle glaucoma. Am J Nurs, 2009. 109(2): p. 40-7; quiz 48. [CrossRef]

- Allison et al: Assessing Multiple Factors Affecting Minority Participation in Clinical Trials: Development of the Clinical TrialsParticipation Barriers Survey: April 2022: Cureus. [CrossRef]

- Allison et al.: The Value of Annual Glaucoma Screening for High-Risk Adults Ages 60 to 80:Cureus, 2021 Oct; 13(10): e18719. Oct 12.2021. [CrossRef]

- Allison et al: Epidemiology of Glaucoma: The Past. Present, and Predictions for the Future: Cureus 2020 Nov;12(11):e11686. [CrossRef]

- Singh et al: Polygenic Risk Score Improves Prediction of Primary Open Angle Glaucoma Onset in the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: Med.Rxiv. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).