2.1. Conventional Geolocation Process Based on Intersection of Viewing Vectors

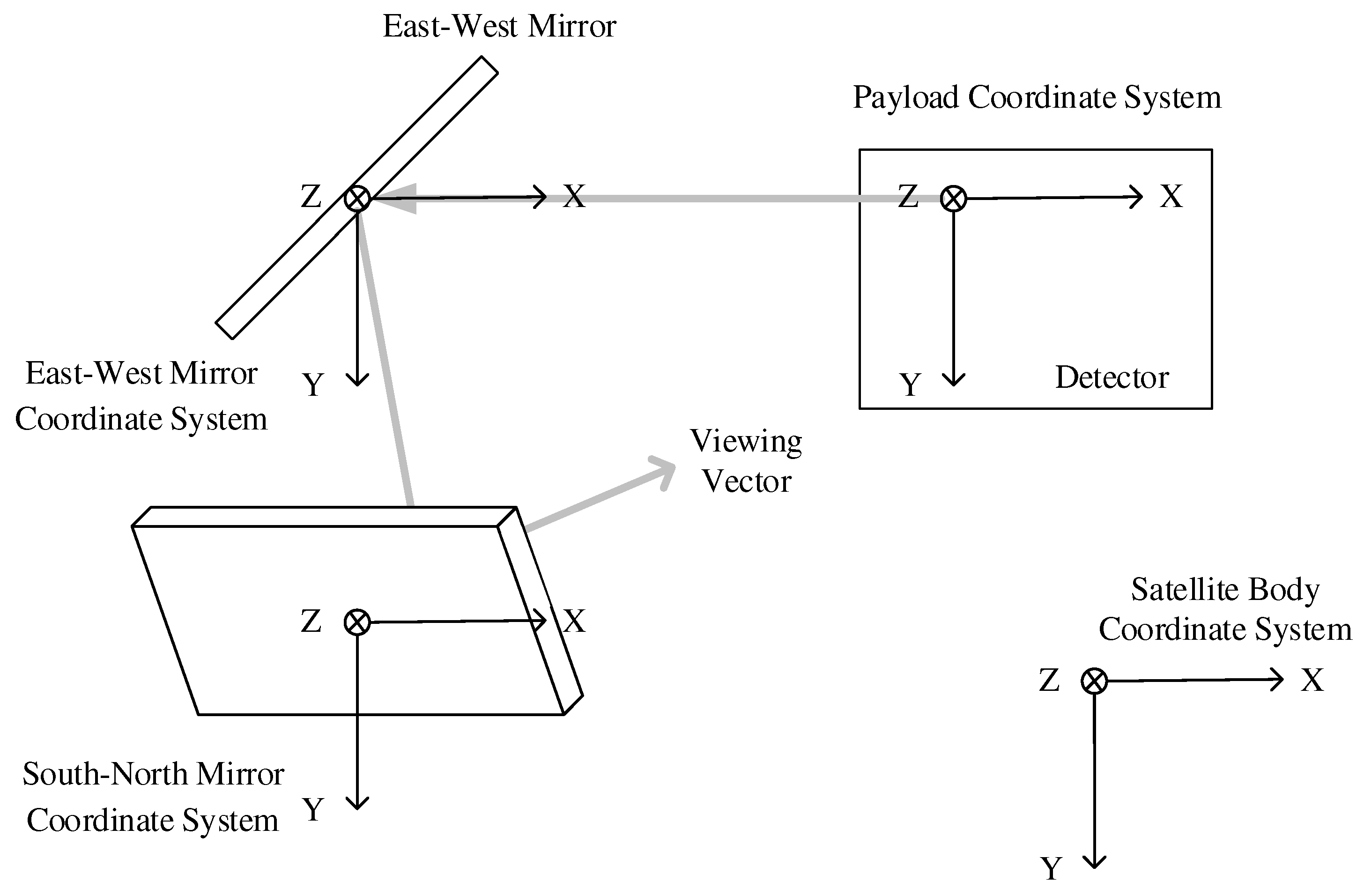

Three-axis stabilized geostationary orbit remote sensing satellites often adopt a dual scanner drive mode, where scanning mirrors are driven in an east-west direction for cross-track scanning and in a north-south direction for along-track stepping, enabling large-area coverage.

Figure 1 presents the scanning mechanism and ideal optical path of the satellite payload.

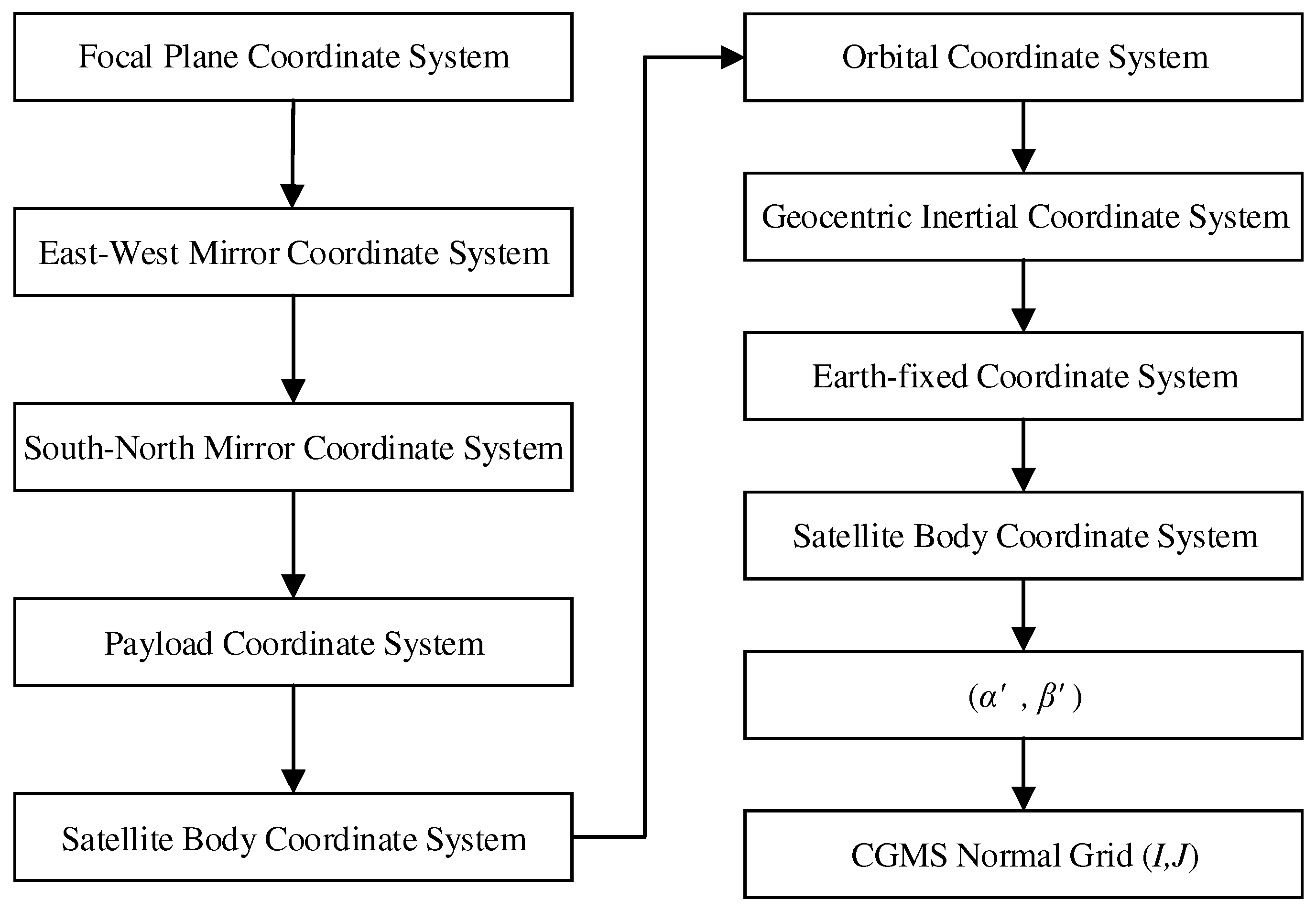

The geolocation algorithm utilizes the scanning mirror angles from the sensor's Level 0 data to computationally determine the corresponding ground latitude and longitude. This conventional geolocation algorithm commences by modeling the instrument's observation geometry to acquire the initial viewing vectors for each pixel. Through a series of coordinate transformations, the image-plane coordinates are projected onto the Earth-fixed coordinate system. The algorithm then computes the intersection coordinates of the sensor's viewing vector with the ground, which are subsequently transformed into latitude and longitude. Finally, these coordinates are mapped onto the coordination group for meteorological satellites (CGMS) grid (a nominal grid with a specific projection defined by the coordination group for meteorological satellites), one of the international standards for meteorological remote sensing. The specific coordinate system transformations involved in this process are graphically depicted in

Figure 2.

The initial viewing vector, denoted as

, varies with the changes in the angles of the two scanning mirrors. Assuming the outgoing ray vector in the payload coordinate system is

, the resulting viewing vector after two reflections from the scanning mirrors, denoted as

, was expressed as:

Here, 𝐹1 and 𝐹2 are the reflection matrices for the north-south and east-west mirrors, respectively. These matrices are determined by the angles of rotation 𝛼 for the north-south mirror and 𝛽 for the east-west mirror. The specific derivation process can be found in references [

17,

18,

19].

After the viewing vector exits the satellite body, it is transformed from the satellite body coordinate system to the Earth-fixed coordinate system based on the satellite attitude information, orbit information, and param such as nutation, precession, Greenwich sidereal time, and polar motion. For a given time , the geolocation process for the viewing vector in the payload coordinate system can be divided into the following eight steps:

1) calculating the viewing vector in the payload coordinate system based on the mirror angles and the optical path geometry ;

2) transforming the viewing vector from the payload coordinate system to the body coordinate system by using the installation matrix, obtaining ;

3) based on the orbit attitude, transforming the viewing vector from the body coordinate system to the orbit coordinate system, obtaining

.The satellite body coordinate system was rotated in the order of

and

to obtain the orbit coordinate system.

4) based on the satellite's position and velocity, transforming the viewing vector from the orbit coordinate system to the Earth-centered inertial coordinate system.

The transformation from the orbit coordinate system to the Earth-centered inertial coordinate system is determined by the satellite's instantaneous inertial frame of reference, which considers the position and velocity. This transformation can be obtained by constructing the orbit coordinate system in the inertial frame of reference. The Earth-centered inertial coordinate system was

with unit vectors as

. The orbit coordinate system was

with unit vector

For any given satellite position vector

in the Earth-centered inertial coordinate system, the coordinates of the orbit coordinate system's axes were obtained using the following formula:

According to the definition of the orbit coordinate system, we derived:

The unit vector

, which is orthogonal to both

and the satellite's position vector

, were determined by the following equation:

where

is the velocity vector in the Earth-centered inertial coordinate system. Therefore, the unit vector

was determined by the following equation:

By performing the calculations mentioned above, the transformation matrix from the orbit coordinate system to the Earth-centered inertial coordinate system was obtained as follows:

5) transforming the viewing vector from the Earth-centered inertial coordinate system to the Earth-fixed coordinate system based on time information.

This step mainly relies on information such as precession, nutation, Greenwich sidereal time, and polar motion to transform the viewing vector and satellite position vector from the Earth-centered inertial coordinate system to the Earth-fixed coordinate system. As a result, the viewing vector in the Earth-fixed coordinate system was obtained as follows:

Satellite position vector in the Earth-fixed coordinate system was calculated as:

Here, the subscript WGS represents the Earth-fixed coordinate system. denotes the precession correction matrix, represents the nutation correction matrix, signifies the Greenwich sidereal time rotation matrix, denotes the polar motion correction matrix, and represents the direction cosine matrix from the Earth-centered inertial coordinate system to the Earth-fixed coordinate system.

6) computing the position vector of the intersection point between the viewing vector and the WGS84 ellipsoid in the Earth-fixed coordinate system.

In the Earth-fixed coordinate system, the coordinates of the intersection point between the viewing vector and the surface of the Earth represented by the WGS-84 geodetic reference ellipsoid were calculated. The equation for the WGS-84 geodetic reference ellipsoid was represented as:

where

represents the major axis and

represents the minor axis. The intersection point

between the viewing vector and the Earth's surface was calculated using formula (12) as follows:

represents the distance between the satellite and the intersection point:

7) converting the coordinates of the intersection point in the Earth-fixed coordinate system to the coordinates in the geodetic coordinate system.

Based on the coordinates of the intersection point in the Earth-fixed coordinate system, the geographic latitude and longitude of the intersection point were calculated using formula (13) as follows:

8) Based on the latitude and longitude of the intersection point, its row and column number (I,J) were calculated on the CGMS grid.

By employing the latitude and longitude coordinates, in conjunction with the north-south scan angle, east-west scan angle, satellite's geolocation, and the Earth model employed, it is possible to computationally determine the row and column number of the point on the nominal grid. For specific details regarding the calculation methodology, please refer to reference [

16].

The computation time and proportion of each step for the conventional geolocation algorithm were computed using simulated data. The results are presented in

Table 2.

2.2. Rapid Geolocation Algorithm for CGMS Nominal Grid

The nominal data format is the most commonly employed format for applying and disseminating geostationary remote sensing data. For instance, China's FY-2 and FY-4 L1A level data, along with the United States' GOES-R satellite L1B level data, are all published in nominal data formats [

14]. The nominal grid comprises fixed observation angles with equal intervals, ensuring that identical data points in all products correspond to the same location on Earth. This provides a basis for further applications of remote sensing imagery. Currently, most geostationary meteorological satellites employ image geolocation methods based on the nominal grid. This allows each pixel in the remote sensing image to be associated with a specific latitude and longitude on Earth. Therefore, there is no need to store latitude and longitude information within the image data itself, significantly reducing the requirements for data transmission and storage.

The geolocation algorithm has a strict correspondence between the initial ray vectors of the remote sensing sensor's pixels, latitude, longitude, and the CGMS nominal grid. The row-column numbers (I, J) of the nominal grid have a unique correspondence with the geographic latitude and longitude (B, L). Therefore, during data geolocation, it is possible to first calculate the row-column numbers (I, J) of the ray vectors on the nominal grid and then obtain the corresponding geographic latitude and longitude (B, L) through a quick query. The ultimate goal of geolocation is to compute the position of the ray on the CGMS nominal grid. By analyzing the transformation process of the ray vector in different coordinate systems, this paper proposes a rapid algorithm that eliminates the time-consuming process of computing latitude and longitude. Instead, it directly establishes the correspondence between the ray vectors of the remote sensing sensor's pixels in the satellite body coordinate system and the CGMS nominal grid's row-column numbers (I, J), thus achieving the final geolocation.

After converting the viewing vector from the Earth-centered inertial coordinate system to the Earth-fixed coordinate system, errors caused by attitude, orbit, precession, nutation, Greenwich sidereal time, and polar motion are eliminated. It can be considered an idealized viewing vector in the satellite body coordinate system.

At this point, the viewing vector in the Earth-fixed coordinate system can be directly transformed into the equivalent ideal state in the satellite body coordinate system. The representation of this viewing vector was given as:

where

represents the transformation matrix from the Earth-fixed coordinate system to the satellite body coordinate system. The specific method for numerical conversion between the geostationary sensor imaging grid and the CGMS grid can be found in reference [

16,

17].

Based on the viewing vector in the satellite body coordinate system, the relationship between the corresponding CGMS mirror angles

was established as follows:

The

values were calculated as follows:

Subsequently, the corresponding

for

were calculated as follows:

where

represents the size of the nominal grid, and

is the angular size of a pixel in this band.

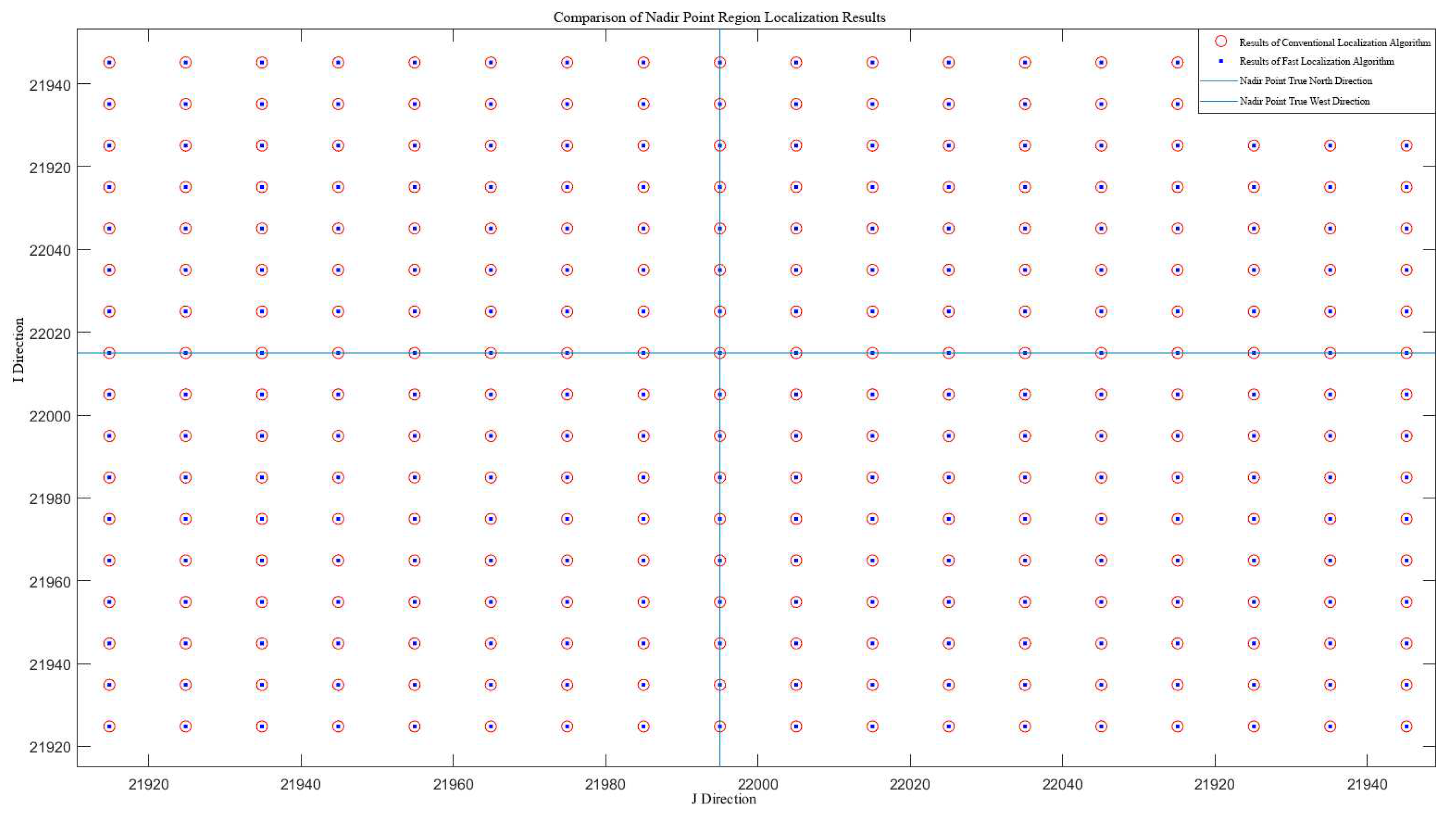

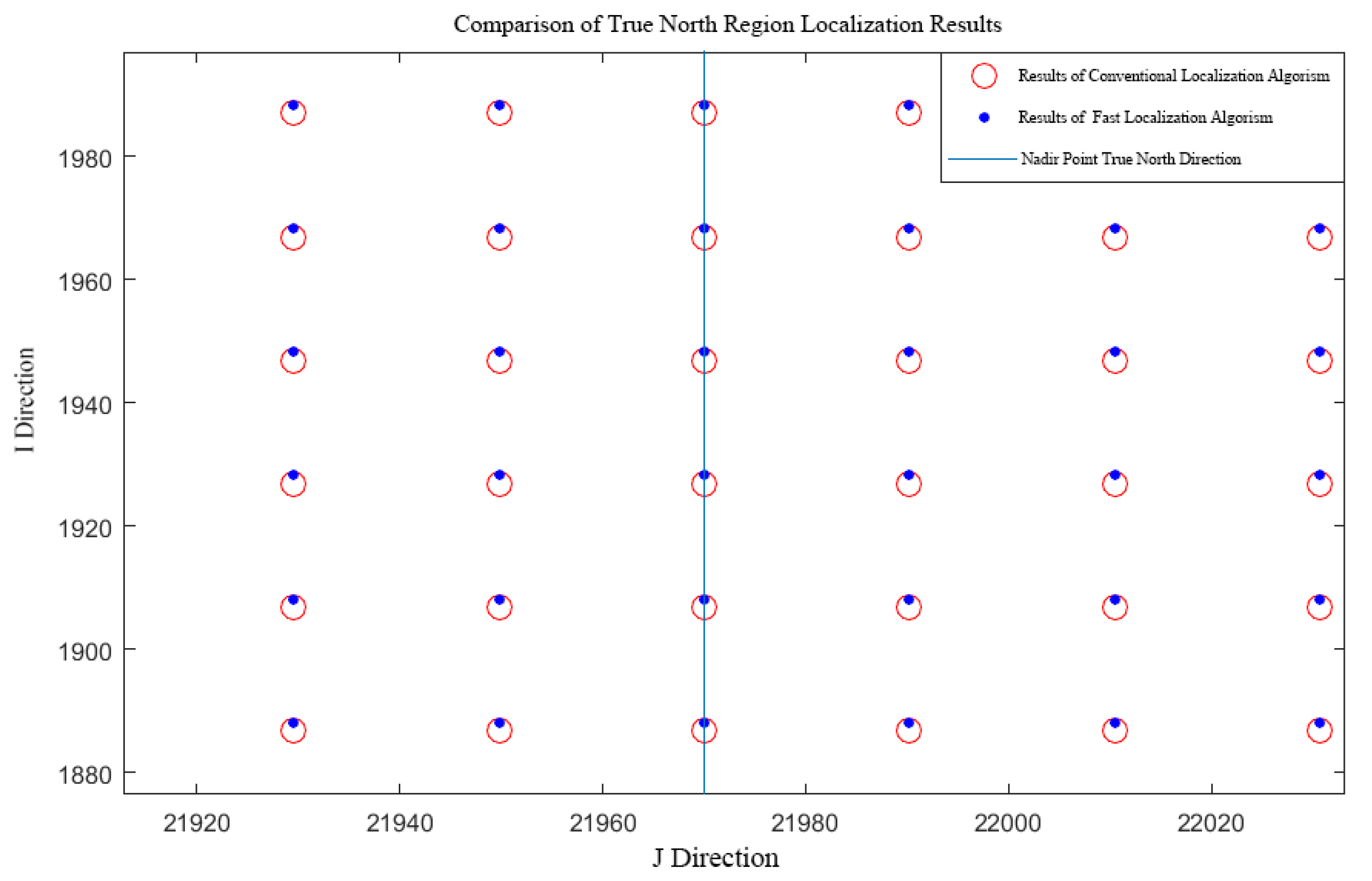

Through the aforementioned refinements, the computationally burdensome process of finding the intersection point between the viewing vector and the Earth's ellipsoid was obviated. Instead, a direct mapping relationship was established between the original initial vector and the nominal grid. In the geolocation process, after transforming the ray vector into the Earth-fixed coordinate system, the positioning result was obtained directly through the conversion relationship between the ray vectors in the sensor imaging grid and the CGMS grid, without the need for iterative calculations to solve for the intersection point between the ray and the Earth's ellipsoidal surface. The flowchart of the improved rapid geolocation algorithm can be found in

Figure 3.

Figure 3 illustrates that in the rapid algorithm flow, the calculations prior to the Earth-fixed coordinate system are consistent with the conventional algorithm flow. In the Earth-fixed coordinate system, the viewing vector no longer intersects with the geodetic ellipsoid. Instead, the viewing vector in the Earth-fixed coordinate system is transformed into the ideal state in the satellite body coordinate system. This is equivalent to the viewing vector of the actual satellite's downlink data being transformed into the idealized viewing vector (i.e., the corrected viewing vector after considering various error factors) through positioning and compensation calculations. Then, the mirror angles

corresponding to the idealized viewing vector are calculated. By using the relationship between the angles and the initial position, along with the angle step size, the corresponding row-column numbers

can be computed.