Submitted:

22 December 2023

Posted:

26 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cyclicality and Pro-Cyclicality of LLPs

2.1.1. Overview

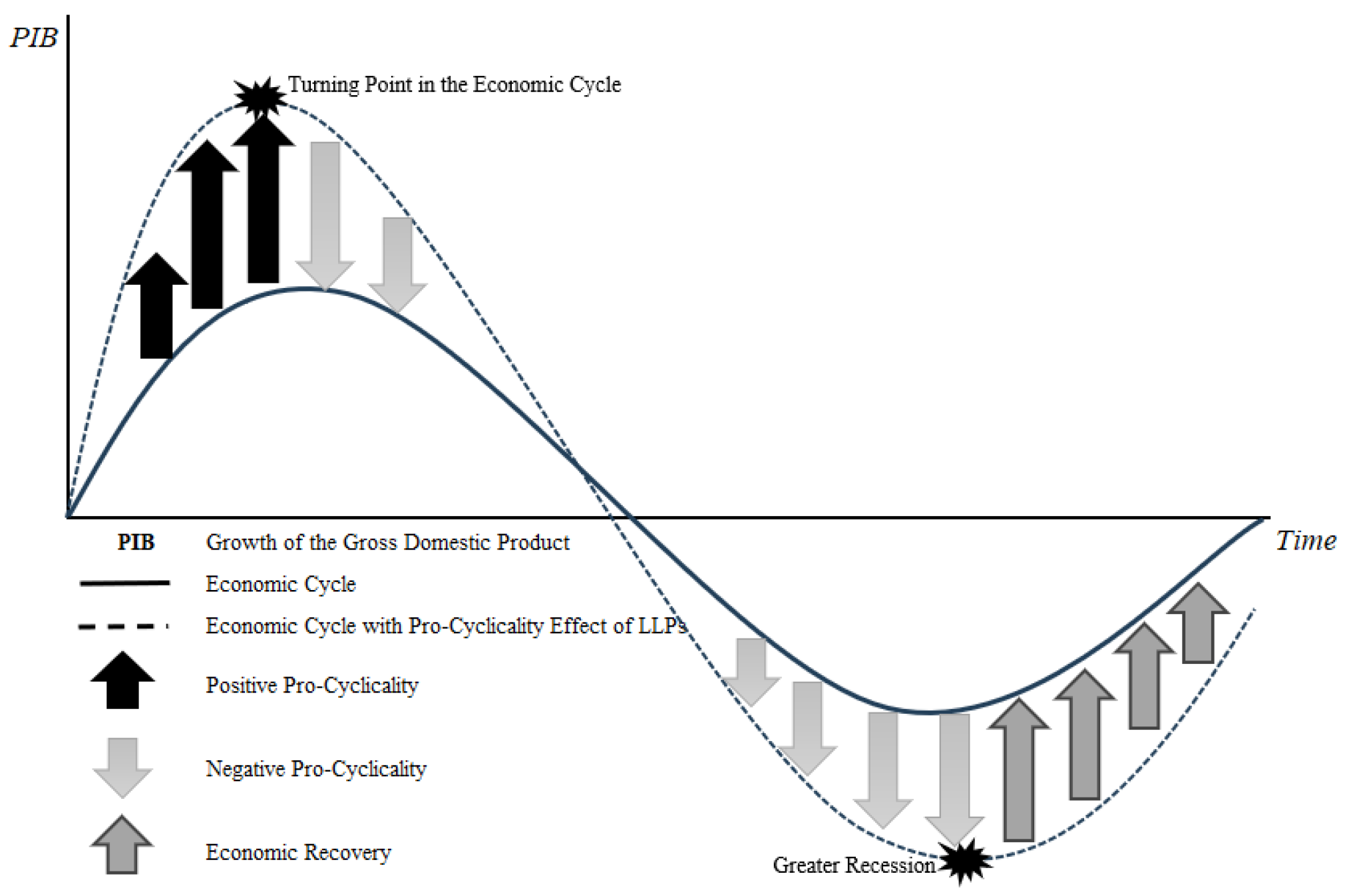

- Cyclicality: Refers to the cyclical nature of the economy, characterized by periods of expansion and recession. Economic cycles impact LLPs due to variations in the financial performance of companies and households.

- Pro-cyclicality: Refers to the tendency of policies, practices, or financial instruments to amplify the cyclical fluctuations of the economy, rather than mitigating them. In the context of LLPs, pro-cyclicality occurs when the actions of financial institutions exacerbate economic movements, increasing risks during periods of expansion and recession.

2.1.2. Subsubsection

- A key variable in credit assessment is the expectation of future cash flows of companies to pay their debts.

- In a booming economic cycle, macroeconomic factors (e.g., consumption, production) significantly favor most companies' projections, such as cash flows and debt repayment capacity.

- With this positive bias, banks' credit assessments are also favored, determining a lower default probability, increasing credit issuance to companies, and thus, their leverage.

- More credit leads to increased production investment and greater infusion of resources into the real economy, further amplifying economic growth (positive pro-cyclicality).

- This assessment can create a vicious cycle, resulting in an economic boom until a specific event occurs or leverage (i.e., risk) increases. This situation is not sustainable and can lead to a reversal of expectations.

- Once expectations reverse, the capacity of companies to generate cash flows is questioned and reassessed.

- With this negative bias, there is an increase in credit risk assessed by banks, also increasing the probability of default and reducing (or even ceasing) credit issuance.

- The reduction (or absence) of credit negatively impacts investments and even production, further amplifying the negative effect on the economy (negative pro-cyclicality), potentially creating a vicious cycle and dragging the economy into a recession and possible collapse.

- Unlike the previous reversal, exiting a recession (especially one exacerbated by credit pro-cyclicality) is more costly and time-consuming. The change is slow to alter market perception and, consequently, the financial institutions' credit risk analysis. The resumption of credit issuance is a critical variable for economic recovery.

2.1.2. Cyclicality and Pro-Cyclicality in the ICL Model of IAS 39

2.1.3. Cyclicality and Pro-Cyclicality in the ICL Model of IAS 39

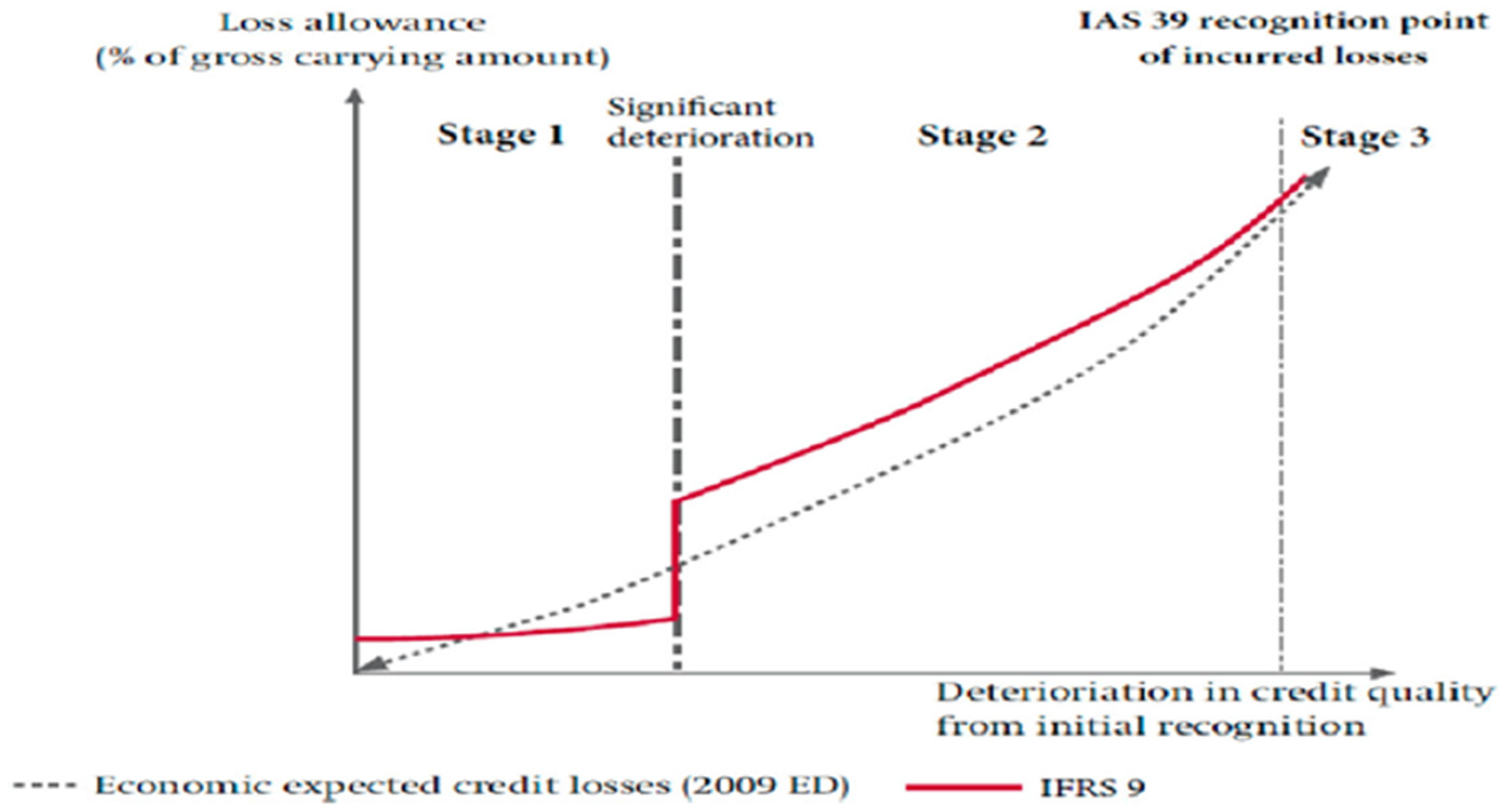

- At the peak of the economic cycle, PDs and LGDs are lower, requiring less capital, increasing regulatory capital, and allowing for more credit to be granted for the same amount of available capital. However, in the face of phase 1 of the ECL model, a containment in excessive credit granting is expected, considering economic forecasts.

- At the onset of a potential recession period, the PD and LGD are higher, necessitating more capital, thus reducing regulatory capital and, consequently, the availability to grant more credit. It is expected that the LLAs will be larger, enabling the absorption of future LLPs and maintaining credit provision, contributing to the reversal of the downward economic cycle.

2.2. The Relationship Between LLPs and Economic Cycles

2.3. Impact of Dynamic Models on Economic Cycles Management

2.3.1. Dynamic Models of LLPs

2.3.2. Analysis of the IFRS 9 ECL Model

2.4. Formulation of Hypotheses

3. Methodology

3.1. Analysis Model and Variables

3.2. Sample and Data

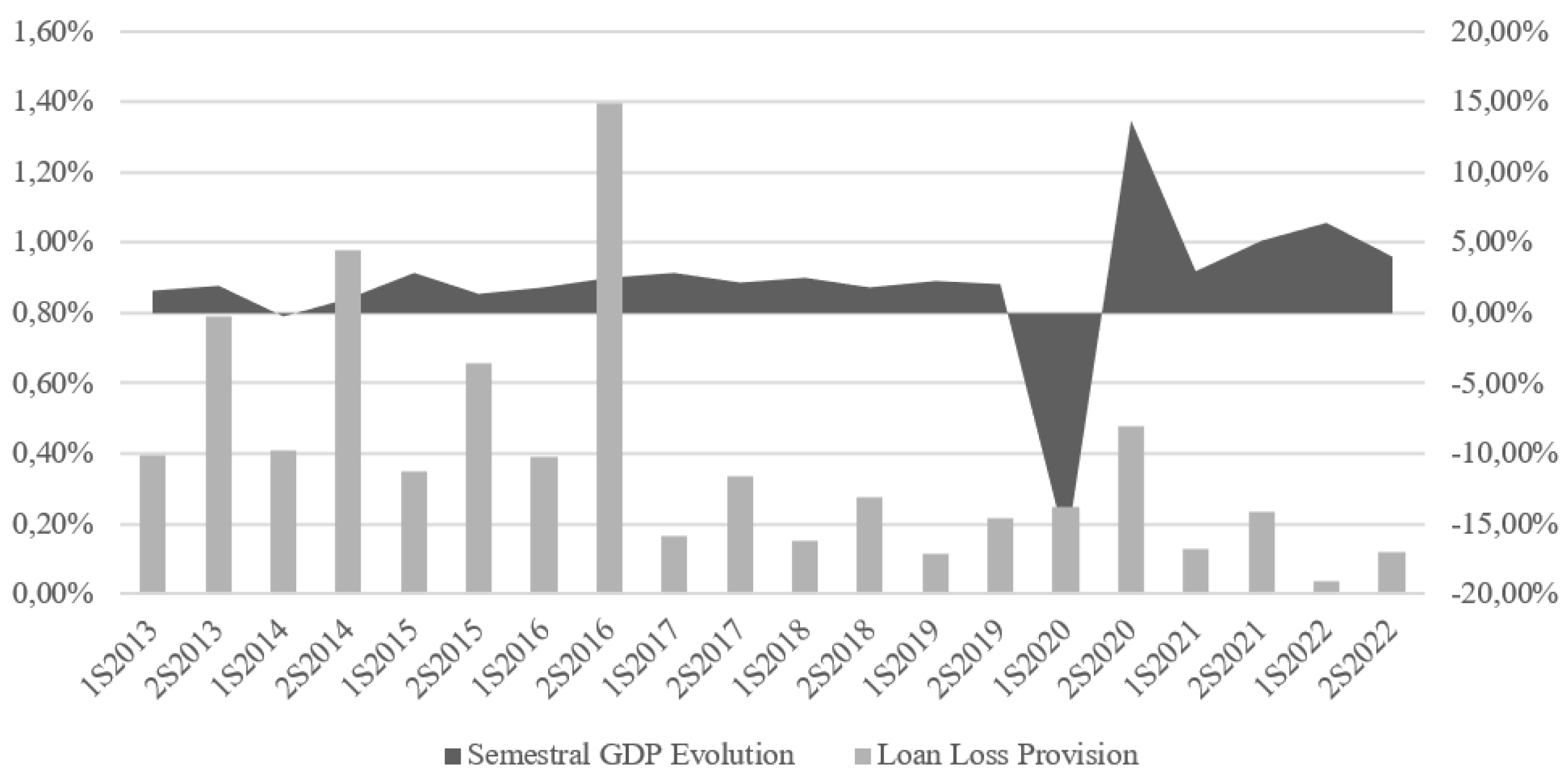

Semestral GDP Evolution | Net LLP over Total Assets of Banks

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Analysis and Discussion of Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In the specialized literature on the subject, it is common to encounter the terms Loan Loss Provisions (LLPs) and Loan Loss Allowances (LLAs) to designate credit impairment losses. For the sake of uniformity in the terminology used in studies, this research will use the abbreviation LLP to express credit impairment losses recognized in the period, and LLA for the accumulated credit impairment losses, following the approach of Salazar et al. (2023). |

| 2 | In this study, the term earnings management is used to describe deliberate intervention by managers through the recognition of LLP and its impact on the banks' results and equity. According to Schipper (1989), this manipulation is an intentional intervention in financial information to obtain specific benefits, particularly through the selection of accounting practices that align more closely with the interests of managers or the company. Similarly, Healy and Wahlen (1999) note that earnings management occurs when managers use their judgment to alter financial reports to influence stakeholders' perception or meet specific contractual clauses. |

| 3 | During the COVID-19 pandemic, the IASB intervened, limiting the recognition and increase of LLPs for phase 2 (significant increase in risk) through a communication that altered the accounting policy of the ECL model. In this note, the IASB indicates that the impact on loans due to moratoriums, when backed by the states, should not be interpreted as a significant increase in risk. |

| 4 | "LLA = EAD × PD × LGD" |

References

- Abad, J. , & Suarez, J. (2017). Assessing the cyclical implications of IFRS9: A recursive model. European Systemic Risk Board. [CrossRef]

- Agénor, P. R., & Zilberman, R. (2015). Loan loss provisioning rules, procyclicality, and financial volatility. Journal of Banking and Finance, 61, 301–315. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, A. M. H. , Lustosa, P. R. B., & Dantas, J. A. (2018). A Ciclicidade da Provisão para Créditos de Liquidação Duvidosa nos Bancos Comerciais do Brasil. Brazilian Business Review, 15(3), 246–261. [CrossRef]

- Balla, E., & Mckenna, A. (2009). Countercyclical tool for. Convergence, 95(4), 383–418.

- Barnoussi, A. , Howieson, B., & van Beest, F. (2020). Prudential application of IFRS 9: (Un)fair reporting in COVID-19 crisis for banks worldwide?!. Australian Accounting Review, 30(3), 178–192. [CrossRef]

- Beatty, A. , & Liao, S. (2014). Financial accounting in the banking industry: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 58(2–3), 339–383. [CrossRef]

- Bebczuk, R. , Burdisso, T., Carrera, J., & Sangiácomo, M. (2011). A new look into credit procyclicality: International panel evidence. BCRA Working Paper, (55), 1–40.

- Beck, P. J. , & Narayanamoorthy, G. S. (2013). Did the SEC impact banks’ loan loss reserve policies and their informativeness? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 56(2–3), 42–65. [CrossRef]

- Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (2004). The institutional memory hypothesis and the procyclicality of bank lending behavior. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 13(4), 458–495. [CrossRef]

- Bikker, J. A. , & Metzemakers, P. A. J. (2005). Bank provisioning behaviour and procyclicality. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 15(2), 141–157. [CrossRef]

- Bischof, J. , Laux, C., & Leuz, C. (2021). Accounting for financial stability: Bank disclosure and loss recognition in the financial crisis. Journal of Financial Economics, 141(3), 1188–1217. [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg. (2012). The EU smiled while Spain’s banks cooked the books - Bloomberg. Retrieved from http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-06-14/the-eu-smiled-while-spain-s-banks-cooked-the-books.html.

- Borio, C. , Furfine, C., & Lowe, P. (2001). Procyclicality of the financial system and financial stability: Issues and policy options. BIS Papers Chapters, 01(1), 1–57. Retrieved from http://ideas.repec.org/h/bis/bisbpc/01-01.html.

- Bouvatier, V. , & Lepetit, L. (2012). Provisioning rules and bank lending: A theoretical model. Journal of Financial Stability, 8(1), 25–31. [CrossRef]

- Bushman, R. M. , & Williams, C.D. (2015). Delayed expected loss recognition and the risk profile of banks. Journal of Accounting Research, 53(3), 511–553. [CrossRef]

- Camfferman, K. (2015). The emergence of the ‘incurred-loss’ model for credit losses in IAS 39. Accounting in Europe, 12(1), 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Casta, J. F. , Lejard, C., & Paget-Blanc, E., (2019, August). The implementation of the IFRS 9 in banking industry. EUFIN 2019: The 15th Workshop on European Financial Reporting, Vienne, Austria. hal-02405140.

- Chan-Lau, J. A. (2012). Do dynamic provisions enhance bank solvency and reduce credit procyclicality? A study of the Chilean banking system. Journal of Banking Regulation, 13, 178-188. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Yang, C., & Zhang, C. (2020). Study on the influence of IFRS 9 on the impairment of commercial bank credit card. Applied Economics Letters, 29(1), 35–40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A. , Detragiache, E., & Tressel, T. (2008). Banking on the principles: Compliance with Basel core principles and bank soundness. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 17(4), 511–542. [CrossRef]

- Donelian, M. S. (2019). Os efeitos colaterais do IFRS9: O aumento da prociclicidade do crédito na economia real. Retrieved July 17, 2023, from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/os-efeitos-colaterais-do-ifrs9-o-aumentoda-crédito-na-donelian/?trk=pulse-article&originalSubdomain=pt.

- Du, N. , Allini, A., & Maffei, M. (2023). How do bank managers forecast the future in the shadow of the past? An examination of expected credit losses under IFRS 9. Accounting and Business Research, 53(6), 699-722. [CrossRef]

- EBA. (2021). IFRS 9 implementation by EU institutions: Monitoring report. European Banking Authority. [CrossRef]

- Engelmann, B. , & Lam Nguyen, T. T. (2023). Global assessment of the COVID-19 impact on IFRS 9 loan loss provisions. Asian Review of Accounting, 31(1), 26–41. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. (2011). Instrumentos Financeiros. Rei dos Livros.

- Flannery, M. J. , Kwan, S. H., & Nimalendran, M. (2013). The 2007-2009 financial crisis and bank opaqueness. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 22(1), 55–84. [CrossRef]

- FASB-IASB (2009, March). Information for observers: Spanish provisions under IFRS (Agenda paper 7C), IASB-FASB Meeting, London.

- Gebhardt, G. , & Novotny-Farkas, Z. (2011). Mandatory IFRS adoption and accounting quality of European banks. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 38(3–4), 289–333. [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, M. , Kanagaretnam, K., Mestelman, S., & Shehata, M. (2019). Testing the efficacy of replacing the incurred credit loss model with the expected credit loss model. European Accounting Review, 28(2), 309–334. [CrossRef]

- Harrald, P. , & Sandall, T. (2010). Tackling pro-cyclicality in banking regulation. Retrieved from https://www.risk.net/regulation/1800392/tackling-pro-cyclicality-banking-regulation.

- Healy, P. M., & Wahlen, J. (1999). A review of the earnings management literature and its implications for standard settings. Accounting Horizons, 13(4), 365-383. [CrossRef]

- Hoogervorst, H. (2014). Closing the accounting chapter of the financial crisis [Speech]. Asia-Oceania Regional Policy Forum, (April), 1–5. Retrieved from https://cdn.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/news/speeches/2014/hans-hoogervorst-march-2014.pdf.

- IASB. (2020). IFRS 9 and Covid-19. Retrieved from https://cdn.ifrs.org/-/media/feature/supporting-implementation/ifrs-9/ifrs-9-ecl-and- coronavirus.pdf?la=en.

- KPMG. (2016). IFRS 9 Instrumentos Financeiros: Novas regras sobre a classificação e mensuração de ativos financeiros, incluindo a redução no valor recuperável. Retrieved from https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2016/04/ifrs-em-destaque-01-16.pdf.

- Krüger, S., Rösch, D., & Scheule, H. (2018). The impact of loan loss provisioning on bank capital requirements. Journal of Financial Stability, 36, 114–129. [CrossRef]

- Laureano, R. M. S. (2020). Testes de hipóteses e regressão: O meu manual de consulta rápida. Edições Sílabo.

- Laux, C. (2012). Financial instruments, financial reporting, and financial stability. Accounting and Business Research, 42(3), 239–260. [CrossRef]

- Longbrake, W. A. , & Rossi, C. V. (2011). Procyclical versus countercyclical policy effects on financial services. The Financial Services Roundtable.

- López-Espinosa, G. , Ormazabal, G., & Sakasai, Y. (2021). Switching from incurred to expected loan loss provisioning: Early evidence. Journal of Accounting Research, 59(3), 757–804. [CrossRef]

- López-Espinosa, G. , & Penalva, F. (2023). Evidence from the adoption of IFRS 9 and the impact of COVID-19 on lending and regulatory capital on Spanish banks. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 42. [CrossRef]

- Marton, J. , & Runesson, E. (2017). The predictive ability of loan loss provisions in banks: Effects of accounting standards, enforcement and incentives. British Accounting Review, 49(2), 162–180. [CrossRef]

- Mechelli, A. , & Cimini, R. (2021). The effect of corporate governance and investor protection environments on the value relevance of new accounting standards: The case of IFRS 9 and IAS 39. Journal of Management and Governance, 25(4), 1241–1266. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutional theory and strategic management. The American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A. D. , & White, L. (2010). Reputational contagion and optimal regulatory forbearance. ECB Working Paper Series 1196.

- Nnadi, M. , Keskudee, A., & Amaewhule, W. (2023). IFRS 9 and earnings management: The case of European commercial banks. International Journal of Accounting and Information Management, 31(3), 504–527. [CrossRef]

- Norouzpour, M., Nikulin, E., & Downing, J. (2023). IFRS 9, earnings management and capital management by European banks. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 31(3), 504-527. [CrossRef]

- Novotny-Farkas, Z. (2016). The interaction of the IFRS 9 expected loss approach with supervisory rules and implications for financial stability. Accounting in Europe, 13(2), 197–227. [CrossRef]

- Olszak, M., Pipień, M., Kowalska, I., & Roszkowska, S. (2017). What drives heterogeneity of cyclicality of loan-loss provisions in the EU? Journal of Financial Services Research, 51(1), 55–96. [CrossRef]

- Onali, E. , Ginesti, G., Cardillo, G., & Torluccio, G. (2021). Market reaction to the expected loss model in banks. Journal of Financial Stability, 100884. [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P. K. (2019). Bank income smoothing, institutions and corruption. Research in International Business and Finance, 49(February), 82–99. [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P. K. , & Outa, E. (2017). Bank loan loss provisions research: A review. Borsa Istanbul Review, 17(3), 144–163. [CrossRef]

- Pastiranová, O. , & Witzany, J. (2022). IFRS 9 and its behavior in the cycle: The evidence on EU countries. Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting, 33(1), 5–17. [CrossRef]

- Pastiranová, O., & Witzany, J. (2021). Impact of implementation of IFRS 9 on Czech banking sector. Prague Economic Papers, 30(4), 449–469. [CrossRef]

- Poghosyan, T. , & Čihak, M. (2011). Determinants of bank distress in Europe: Evidence from a new data set. Journal of Financial Services Research, 40(3), 163–184. [CrossRef]

- Pucci, R. (2017). Accounting for financial instruments in an uncertain world: Controversies in IFRS in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis [Doctoral Thesis]. Copenhagen Business School. Retrieved from http://openarchive.cbs.dk/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10398/9477/Richard Pucci.pdf?sequence=1#page=108.

- Salazar, Y. , Merello, P., & Zorio-Grima, A. (2023). IFRS 9, banking risk and COVID-19: Evidence from Europe. Finance Research Letters, 56(June), 104130. [CrossRef]

- Saurina, J. (2009). Dynamic Provisioning. Crisis Response No.7. World Bank. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10986/10241.

- Schipper, K. (1989). Commentary on earnings management. Accounting Horizons, 3(4), 91-102.

- Seitz, B. , Dinh, T., & Rathgeber, A. (2018). Understanding loan loss reserves under IFRS 9: A simulation-based approach. Advances in Quantitative Analysis of Finance and Accounting, 16, 311–375.

- Silva, E. S. (2017). IFRS 9 - Instrumentos Financeiros - Introdução às regras de reconhecimento e mensuração. Vida Económica.

- Volarević, H. , & Varović, M. (2018). Internal model for IFRS 9: Expected credit losses calculation. Ekonomski Pregled, 69(3), 269–297. [CrossRef]

- Wall, L. D. , & Koch, T. W. (2000). Bank loan-loss accounting: A review of theoretical and empirical evidence. Economic Review, (Q2), 1–20. Retrieved from http://ideas.repec.org/a/fip/fedaer/y2000iq2p1-20nv.85no.2.html.

- Wezel, T. (2010). Dynamic loan loss provisions in Uruguay: Properties, shock absorption capacity and simulations using alternative formulas. IMF Working Papers, 10(125), 1. [CrossRef]

- Zucker, L. G. (1987). Institutional theories of organization. Annual Review of Sociology. Vol. 13, 443–464. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Type | Definition | Previous Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent | Net LLPs over total assets of bank i in year t | Araújo et al. (2018), López-Espinosa et al. (2021), Nnadi et al. (2023), Norouzpour et al. (2023) and Pastiranová and Witzany (2022) | |

| Independent | Real GDP growth in year t | Araújo et al. (2018), Beatty e Liao, (2014), Casta et al. (2019), Marton and Runesson (2017), Nnadi et al. (2023), Norouzpour et al. (2023), Ozili and Outa (2017) and Pastiranová and Witzany (2022) | |

| Independent | Unemployment rate in year t | Araújo et al. (2018), Beatty and Liao (2014) and Casta et al. (2019) | |

| Independent | Earnings before taxes and LLPs over total assets of bank i in year t | Araújo et al. (2018), Nnadi et al. (2023), Norouzpour et al. (2023) and Ozili and Outa (2017) | |

| Independent | Equity over total assets of bank i in year t | Araújo et al. (2018), Casta et al. (2019) and Ozili and Outa (2017) |

|

| Control | Variation between total loans of year t and year t-1, divided by total loans of year t of bank i | Araújo et al. (2018), Beatty and Liao (2014), Norouzpour et al. (2023) and Ozili and Outa (2017) | |

| Control | Total loans over total assets of bank i in year t | Araújo et al. (2018), Ozili and Outa (2017) Marton and Runesson, (2017) and Beatty and Liao (2014) |

|

| Control | LLA in relation to total assets of bank i in year t | Beatty and Liao (2014) and Casta et al. (2019) | |

| Control | Natural logarithm of total assets of bank i in year t | Araújo et al. (2018), Beatty e Liao (2014), Casta et al. (2019), Nnadi et al. (2023) and Norouzpour et al. (2023) |

|

| Control | Dummy variable that takes the value 1 in the years of application of IFRS 9, and the value 0 in the years of application of IAS 39 | Casta et al. (2019), Marton and Runesson (2017), Nnadi et al. (2023) and Norouzpour et al. (2023) |

| Variable | Expected behavior | Signal |

|---|---|---|

| Higher sensitivity to economic variations is expected in the ECL model, where a positive or negative change in GDP may decrease or increase, respectively, the level of LLPs, indicating the existence of cyclicality in the model. | +/- | |

| Higher sensitivity to changes in economic measures is expected, where a positive or negative variation in unemployment rate may increase or decrease, respectively, the level of LLPs, signaling the existence of cyclicality in the model. | +/- | |

| Banks are expected to use LLPs as an earnings management tool, where an increase in earnings before taxes and LLPs will increase the level of LLPs. | + | |

| Banks are expected to use LLPs as an equity management tool, where a negative variation in a bank's capital may increase the level of LLPs. Banks tend to increase LLPs when regulatory capital is below required levels. This practice is more common in banks with lower capitals. | - | |

| A positive variation in granted loans represents an increase in credit risk. Hence, a positive change in granted loans is expected to increase the value of LLPs. | + | |

| The larger the share of granted loans in a bank's total investments, the higher its credit risk. An increase in the ratio of total loans to total assets is expected to increase the value of LLPs. | + | |

| The larger the LLAs in a bank's total investments, the higher its credit risk. An increase in the ratio of LLAs to total assets is expected to increase the value of LLPs. | + | |

| The larger the bank, the higher the levels of LLPs recognition. The larger the bank, the higher the value of LLPs is expected to be. | + | |

| Higher LLPs values are expected with the new ECL model of IFRS 9, compared to the ICL model of IAS 39. | + |

| Banks / (in thousands of euros) | Total Assets 31/12/2022 | %* | Net LLPs** | EBTP31/12/2022 | %*** | LLAs31/12/2022 | %**** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGD | 102 503 009 | 33.44% | - 5 300 | 1 124 898 | 1.10% | 2 254 541 | 2.20% |

| BCP | 89 860 541 | 29.31% | 300 829 | 424 967 | 0.47% | 1 502 373 | 1.67% |

| Santander | 56 166 620 | 18.32% | - 11 943 | 841 856 | 1.50% | 946 296 | 1.68% |

| BPI | 38 904 553 | 12.69% | 66 334 | 527 119 | 1.35% | 519 264 | 1.33% |

| Montepio | 19 106 251 | 6.23% | 13 371 | 93 063 | 0.49% | 374 034 | 1.86% |

| TOTAL | 308 977 957 | 100.00% | 363 291 | 5 596 608 | 5 596 508 | ||

| *Total assets of the bank as a percentage of the total assets | **If negative, it indicates more reversals than LLPs | *** Earnings Before Taxes and LLPs (EBTP) as a percentage of the bank's total assets | **** LLAs as a percentage of the bank's total assets | |||||||

| N | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Min. | -0.002 | -0.166 | -0.224 | -0.003 | 0.040 | -0.128 | 0.610 | 0.012 | 16.7 | 0 |

| Max. | 0.026 | 0.137 | 0.452 | 0.017 | 0.108 | 0.279 | 0.882 | 0.066 | 18.5 | 1 |

| Mean | 0.004 | 0.021 | -0.053 | 0.007 | 0.078 | 0.004 | 0.717 | 0.033 | 17.7 | - |

| Median | 0.003 | 0.023 | -0.080 | 0.006 | 0.079 | -0.004 | 0.717 | 0.028 | 17.8 | - |

| SD | 0.005 | 0.052 | 0.145 | 0.005 | 0.014 | 0.055 | 0.054 | 0.015 | 0.576 | - |

| Variáveis | Modelo ICL (2013 – 2017) | Modelo ECL (2018 – 2022) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min. | Max. | Mean | Median | SD | Min. | Max. | Mean | Median | SD | |

| H1: | ||||||||||

| -0,003 | 0,029 | 0,018 | 0,019 | 0,009 | -0,166 | 0,137 | 0,025 | 0,027 | 0,072 | |

| -0,224 | 0,103 | -0,082 | -0,080 | 0,089 | -0,209 | 0,452 | -0,023 | -0,080 | 0,180 | |

| H2: | ||||||||||

| -0,003 | 0,017 | 0,006 | 0,005 | 0,005 | 4,27e-4 | 0,016 | 0,007 | 0,006 | 0,004 | |

| 0,040 | 0,100 | 0,070 | 0,072 | 0,014 | 0,065 | 0,108 | 0,085 | 0,086 | 0,010 | |

| Controlo: | ||||||||||

| -0,085 | 0,279 | -0,009 | -0,016 | 0,061 | -0,128 | 0,152 | 0,018 | 0,015 | 0,045 | |

| 0,610 | 0,779 | 0,700 | 0,715 | 0,046 | 0,646 | 0,882 | 0,733 | 0,719 | 0,057 | |

| 0,018 | 0,065 | 0,042 | 0,046 | 0,014 | 0,012 | 0,057 | 0,025 | 0,022 | 0,011 | |

| 16,8 | 18,5 | 17,7 | 17,6 | 0,551 | 16,7 | 18,5 | 17,7 | 17,8 | 0,605 | |

| Sample | 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| Observations | 50 | |||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||||

| *** - 0.297 | 1 | |||||||||

| -0.122 | *** 0.350 | 1 | ||||||||

| -0.124 | 0.030 | -0.164 | 1 | |||||||

| *** -0.450 | *** 0.273 | -0.091 | *** 0.387 | 1 | ||||||

| ** - 0.217 | *** 0.260 | 0.127 | 0.102 | *** 0.288 | 1 | |||||

| -0.073 | 0.136 | 0.029 | -0.020 | 0.118 | ** 0.250 | 1 | ||||

| *** 0.595 | *** - 0.323 | -0.091 | *** -0.262 | *** -0.323 | *** -0.370 | -0.120 | 1 | |||

| -0.019 | 0.041 | 0.034 | 0.084 | -0.035 | -0.002 | *** - 0.398 | 0.057 | 1 | ||

| *** - 0.396 | *** 0.434 | 0.087 | * 0.191 | *** 0.548 | *** 0.498 | ** 0.249 | *** -0.581 | 0.003 | 1 |

| Subperiod models | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Main Model (2013 - 2022) | ICL Model (2013 - 2017) | ECL Model (2018 - 2022) |

| H1: | |||

| (-0.019) | (-0.296) | (-1.510) | |

| (0.026) | *** (-3.183) | *** (2.970) | |

| H2: | |||

| *** (2.894) | ** (2.090) | * (1.740) | |

| *** (-4.558) | *** (-4.723) | * (-1.910) | |

| Control: | |||

| (-1.025) | * (1.92) | (1.110) | |

| (1.341) | (1.124) | * (-1.710) | |

| *** (6.194) | *** (3.846) | ** (2.150) | |

| (-0.819) | * (-1.697) | ** (-2.28) | |

| (1.017) | |||

| 0.502 | 0.625 | 0.447 | |

| Teste F | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| N | 100 | 50 | 50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).