1. Introduction

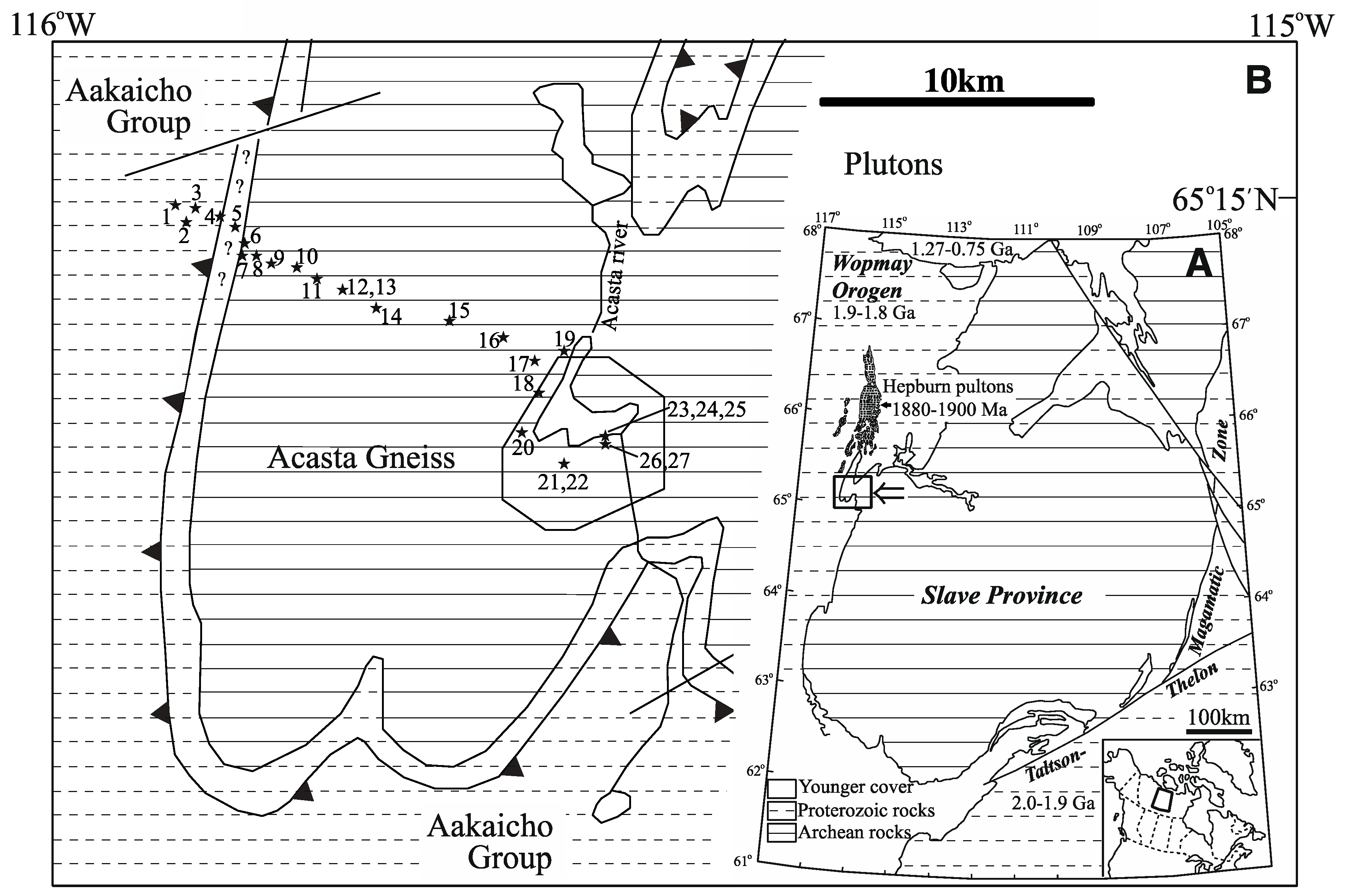

Slave Province is a well-exposed Archean terrane located in the northwestern corner of the Canadian Shield. It is bordered by the Thelon–Taltson orogen (2.0 to 1.9 Ga) to the southeast and the Wopmay orogen (1.9 to 1.8 Ga) to the west [

1,

2]. The Acasta gneisses are exposed along the Acasta river in the westernmost Slave province (

Figure 1) [

1,

3]. Bowring et al. [

3] carried out SHRIMP U-Pb analysis of zircon from the Acasta gneiss and identified the source rock of the Acasta gneiss in the Slave province as the oldest (3.96 Ga) supracrustal rock on Earth at that time. Iizuka et al. [

4] reported 4.20 ± 0.06 Ga zircon xenocryst in an Acasta gneiss and argued for early continental crust. Iizuka et al. [

5] generated a geological map of the main area of the Acasta gneiss (around the sample locality of the Acasta gneisses reported by Bowring et al. [

3]) and sketch maps of crytical outcrops, and carried out U-Pb analyses of zircon. They revealed at least four tectonothermal events, based on detailed field observations and zircon U-Pb geochronology. Guitreau et al. [

6] summarized the geological events that occurred at the Acasta Gneiss Complex, showing the multi-stage events from 4.2 to 2.6 Ga based on zircon U-Pb geochronology. They also proposed the Wopmay orogen event using the

40Ar /

39Ar ages of biotite and amphibole in the Acasta gneiss reported by Hodges et al. [

7], because the

40Ar /

39Ar ages were similar to the zircon U-Pb ages of the Wopmay orogen. This may mean that the K-Ar system ages of biotite and amphibole in the Acasta gneiss were rejuvenated when the Wopmay orogeny took place in the Paleo–Proterozoic period. The purpose of this paper is to elucidate how the Wopmay orogeny affected the argon isotope systematics of the Acasta gneiss.

We report the K-Ar and 40Ar /39Ar ages of biotite and amphibole from the Acasta gneisses, collected systematically along a traverse 18 km east–west stretch. Based on the age results, we outline the argon isotope systematics of the Archean Acasta gneiss that were affected by the Proterozoic Wopmay orogeny and discuss the heat source that rejuvenated the K-Ar system ages.

2. Geological setting

The Slave Province is an Archean granite-supracrustal terrane located at the northwestern corner of the Canadian Shield; it covers an area of approximately 190,000 km

2 [

1]. It is bounded to the southeast by the Thelon–Taltson orogen (2.0 to 1.9 Ga) and to the west by the Wopmay orogen (1.9 to 1.8 Ga) [

1,

2] (

Figure 1A). It consists mainly of the Yellowknife Supergroup, which is composed of the metasedimentary and metavolcanic rocks (2.72 to 2.65 Ga) that are exposed throughout the province [

8], and the pultons (2.62 to 2.58 Ga) that are seen throughout the entire province [

9]. The metavolcanic rock area is called the Greenstone Zone that consists of basic volcanic and plutonic rocks. The basement gneisses older than the Yellowknife are distributed in the western part of the Slave Province. The Acasta gneiss complex studied in this paper is exposed along the Acasta river in the westernmost part of the Slave province (

Figure 1A). The complex has a heterogeneous assemblage of biotite–amphibole tonalitic to granitic orthogneiss. Large areas of amphibolite also occur, together with less abundant calc-silicate gneiss, quartzite, biotite schist, and ultramafic schist. All of the rocks are intruded by mylonitic granite [

10,

11]. Iizuka et al. [

5] carried out geological mapping of the box area shown in

Figure 1B and presented a 1:5000 geological map. They classified the major assemblage of foliated to gneissic rocks into four lithofacies: 1) a mafic-intermediate gneiss series, 2) a felsic gneiss series, 3) a layered gneiss series, and 4) foliated granite. The main mapped area is subdivided into two main domains by a northeast-trending fault, which juxtaposes contrasting lithologies (see [

5] Figure 3). The felsic gneiss series occurs predominantly in the eastern area. The layered gneiss series is present mainly in the western area. The mafic-intermediate gneiss series predominantly occurs as enclaves of various sizes within the felsic gneiss. The foliated granite predominantly occurs in the western area as intrusions up to 200m wide. Original igneous textures are preserved in the granite [

5]. The zircon U-Pb geochronology conducted by Iizuka et al. [

5] gives the foliated granite as 3.58 Ga, the layered gneiss series as 4.0-3.94 Ga and 3.73 Ga, the felsic gneiss series as 4.03-3.94 Ga, 3.74-3.72 Ga, 3.66 Ga, and 3.66-3.59 Ga, and the mafic-intermediate gneiss series as 4.0 Ga, >3.66 Ga, 3.6 Ga, and >3.59 Ga. These data suggest multiple zircon formations in the Acasta Gneiss Complex. Guitreau et al. [

6] summarized the geological events that occurred at the Acasta Gneiss Complex from 4.2 to 2.6 Ga based on zircon U-Pb geochronology, as mentioned before.

Hildebrand et al. divided the Paleoproterozoic Wopmay orogen [

12] into five major zones, ranging from east to west: the Coronation magin, the Turmoil klippe, the Medial zone, the Great Bear magmatic zone, and the Hottah terrane [

13]. The rocks of the Coronation margin lie unconformably on Archean rocks of the Slave craton, and are collectively termed the Coronation Supergroup [

14]. U-Pb zircon geochronology of volcanic ash beds in the Supergroup provided an age of 1.961 Ga [

15]. Rocks of the Turmoil klippe sit in thrust contact above the Coronation margin. The upper structural levels of the Turmoil klippe are dominated by a single thrust slice, consisting mostly of metamorphosed sedimentary rocks of the Akaitcho group. This group has U-Pb zircon ages of ca. 1.900–1.890 Ga [

13]. Crystalline and cover rocks of the Akaitcho group within the Turmoil klippe have been perforated and intruded by plutons of the Hepburn intrusive suite [

16]. These plutons having U-Pb zircon ages of ca. 1.900–1.880 Ga [

13] are not known to intrude the underlying Slave craton and are confined to the Turmoil klippe. As discussed later, we think the relationship between these plutons and the basement gneisses is in situ. The Great Bear Magmatic zone occupies most of the western exposed part of the Wopmay orogen and has U-Pb zircon ages of ca. 1.880–1.840 Ga [

13]. The Medial zone occurs along the eastern margin of Great Bear Magmatic zone and includes rocks found in all the other zones [

13]. Based on isotopic and field data, the western edge of the Slave craton lies within the Medial zone [

17,

18,

19]. The Hottah terrane, which is exposed to the east and west of the Great Bear Magmatic zone, consists of a crystalline basement, volcanic and sedimentary cover, and a variety of intrusive rocks; it has U-Pb zircon ages of ca. 1.960–1.930 Ga [

13].

Figure 1.

A: a simplified geo-tectonic map of the Slave Province and its surroundings, taken from Hoffman [

1]. The ages of Hepburn pultons are taken from Hildebrand et al. [

13]. B: map showing the locations of the studied samples. Barbed and solid lines in the lithological map represent the Proterozoic thrust and transcurrent faults, respectively [

1,

5]. The box shows the geological mapping area produced by Iizuka et al. [

5]. The tonalitic gneiss used by Bowring et al. [

3] was taken from the same location as samples 23, 24, and 25.

Figure 1.

A: a simplified geo-tectonic map of the Slave Province and its surroundings, taken from Hoffman [

1]. The ages of Hepburn pultons are taken from Hildebrand et al. [

13]. B: map showing the locations of the studied samples. Barbed and solid lines in the lithological map represent the Proterozoic thrust and transcurrent faults, respectively [

1,

5]. The box shows the geological mapping area produced by Iizuka et al. [

5]. The tonalitic gneiss used by Bowring et al. [

3] was taken from the same location as samples 23, 24, and 25.

3. Samples and chemistry of biotite and amphibole

The Acasta gneisses and the Wopmay rocks were collected systematically along a traverse 18 km east–west stretch of the boundary between the Wopmay orogen and the Acasta gneiss (

Figure 1B).

Figure 1B shows the geological mapping area generated by Iizuka et al. [

5]. The nine samples were collected from this geological mapping area. Five of these samples (Hwp 23 ~ Hwp 27) were from the felsic gneiss series, which occurs predominantly in the eastern area (see [

5] Figure 3). The tonalitic gneisses used by Bowring et al. [

3] were from the area as mentioned above. All rock samples were collected from outcrops with exposure of fresh rock, with few signs of weathering, as shown in a photograph (

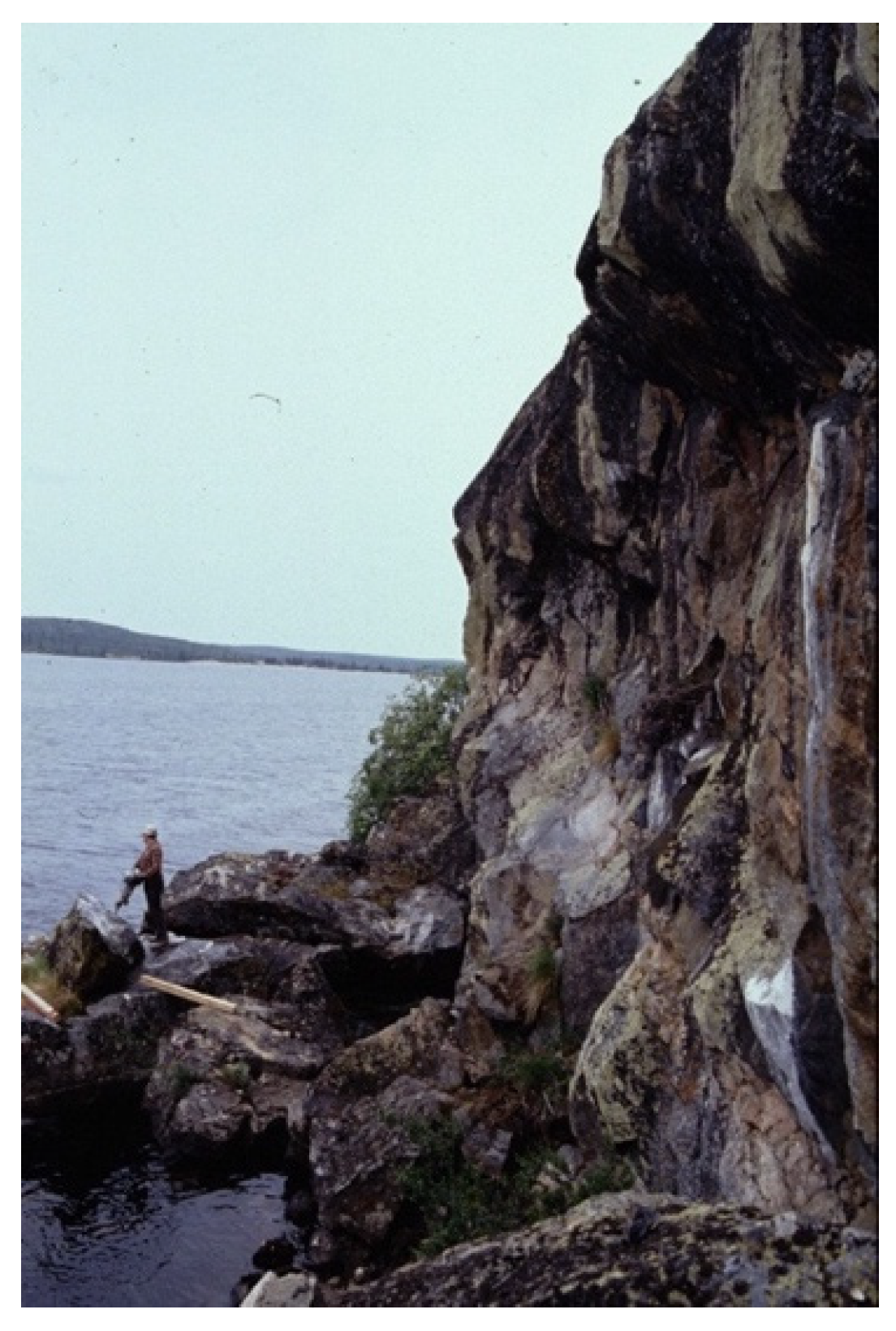

Figure 2). All of the samples are banded gneisses with distinct laminated textures. The gneisses were classified into three types petrographically: felsic, mafic and intermediate (Supplementary Figure 1).

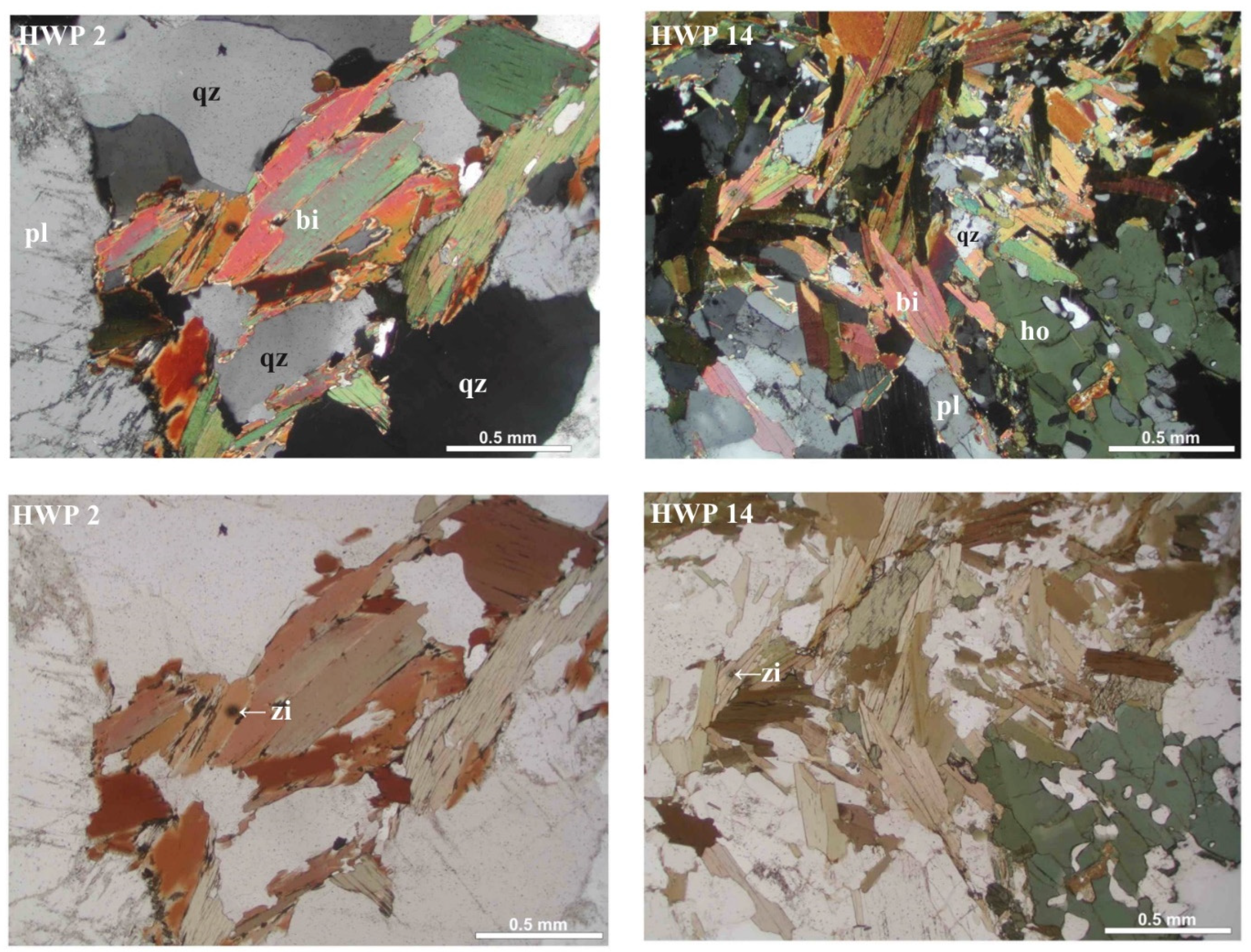

Figure 3 shows the photomicrographs of the representative rock samples: Hwp 2 (felsic) from the Akaitcho group of the Wopmay orogen and Hwp 14 (felsic) from the Acasta gneiss region. Hwp 2 contains coarse grained plagioclase and quartz, and biotite. Hwp 14 contains rather smaller sized plagioclase and quartz, and biotite and amphibole as mafic minerals that are fresh without any secondary phases. No significant mineral zonation is observed optically. A mark “?” zone (

Figure 1B) close to the sample HWP 5 (mafic) has been shown in belonging to the Proterozoic Wopmay orogen (1, 5). However, the zone may belong to the Archean Acasta gneiss because the sample HWP 5 contains amphibole like other Acasta gneiss though the Wopmay samples (Hwp 1, 2, 3 and 4) not. In this study, the barbed line (thrust) closed to the sample HWP 5 is treated as the boundary between the Acasta gneisses and the Wopmay rocks. The Wopmay sample Hwp 4 (felsic) close to the thrust boundary consists of fine-grained minerals in comparison with that in the samples Hwp 1 and Hwp 2 (felsic) far from the thrust boundary (Supplementary Figure 1). Hwp 5 (mafic) also consists of fine-grained minerals in comparison with that in the sample Hwp 23 (mafic) from the main Acasta gneiss region (Supplementary

Figure 1). This suggests these rocks have experienced the grain size reduction by the deformation during the thrust formation. This grain sized reduction is observed in the sample Hwp 4 (felsic) west of Hwp 5 and the samples Hwp 6 (mafic) and Hwp 7 (felsic) east of Hwp 5 (Supplementary Figure 1), indicating the size reduction zone reaches ca. 1km width. The size reduction is also observed in the samples Hwp 17 (felsic), Hwp 18 (felsic), Hwp 21(felsic), Hwp 22 (felsic) of the main Acasta gneiss area (Supplementary Figure 1), suggesting the deformation to produce the mineral size reduction took place in several places.

Chemical compositions of biotite and amphibole were determined using an electron microprobe operated at 15 kV accelerating voltage, a 12 nA beam current, and 3 μm beam spot size. Natural and synthetic silicates and oxides were used for calibration. Matrix corrections were made using the ZAF quantitative correction calculation for oxides.

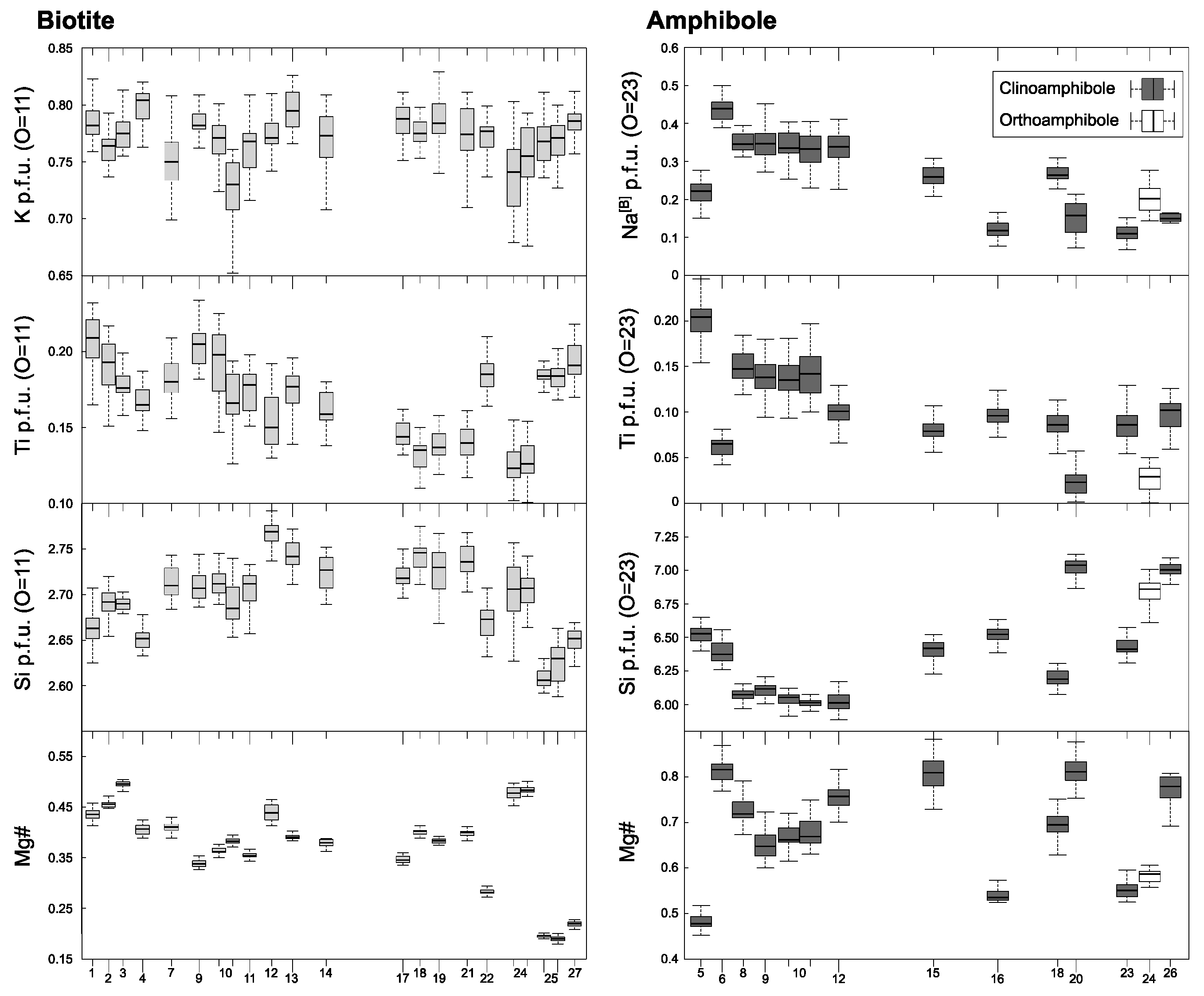

Figure 4 shows the chemistry of biotite (Mg

#, Si, Ti and K) and amphibole (Mg

#, Si, Ti and Na). The Mg

# values of biotite from the Wopmay are from 0.40 to 0.50. The values from the Acasta are from 0.35 to 0.50 similar to the value from Wopmay except for significantly low value samples. The Si values from the Wopmay and the Acasta are 2.65 -2.70 and 2.60-2.75, respectively, giving no significant difference between them. The samples with the low Mg

# and Si values may indicate the substitution of Si (Mg, Fe)-(Al+Al). The Ti values from the Wopmay and the Acasta are 0.16-0.21 and 0.12-0.21, respectively. The K values are within the small variation from 0.73 to 0.81. The amphiboles in the Acasta gneisses consist of mainly clinoamphibole. One sample has exceptionally orthoamphibole. The Mg

# value of amphibole is from 0.5 to 0.8, suggesting variable bulk composition of the gneiss. The Si values varie from 6.0 to 7.0 in relation with the Na values, suggesting some substitution of Si-(Na+Al). The Ti values are less than 0.2.

4. K-Ar analyses

The samples were crushed and sieved, and the 30-to-50 mesh-size fraction was used for the separation of the biotite and amphibole. The sieved fraction was washed in distilled water in an ultrasonic bath to remove fine particles on the grain surfaces, and then dried in an oven at 80°C. A clean, unaltered mineral sample was picked up under a stereomicroscope for the argon analyses. Separate aliquots were further pulverized in an agate mortar for potassium analysis. Potassium concentrations in the biotite and amphibole were determined using flame photometry [

20]. Argon was analyzed at the Okayama University of Science using a sector-type mass spectrometer with a 15 cm radius and a single-collector, utilizing the isotope dilution and argon-38 spike methods [

21]. Mass discrimination was checked with atmospheric argon each day. Specimens wrapped in Al foil were vacuumed out at ca. 180°C for about 24 hours, and argon was then extracted at 1500°C in an ultra-high vacuum line. Reactive gases were removed using a Ti–Zr scrubber. The decay constants for

40K to

40Ar and

40Ca, and the

40K content in potassium were used in the age calculation, are 0.581×10

−10/y, 4.962×10

−10/y, and 0.0001167, respectively [

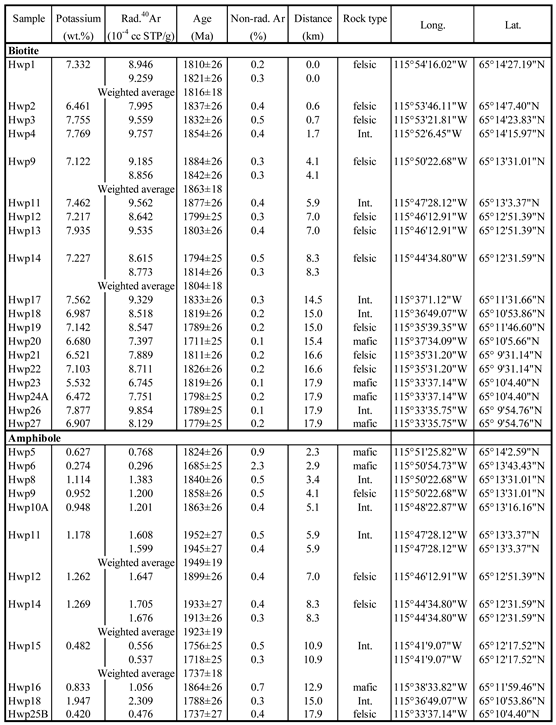

22]. The K–Ar ages for the highly purified biotite and amphibole separates are listed in

Table 1, in which the analytical error is at one sigma confidence level. Duplicate argon analyses were carried out for the biotite of Hwp1, Hwp9, and Hwp14, and the amphibole of Hwp11, Hwp14, and Hwp15. The results show a good reproducibility of the K-Ar analyses. The weighted average for these samples is also shown in

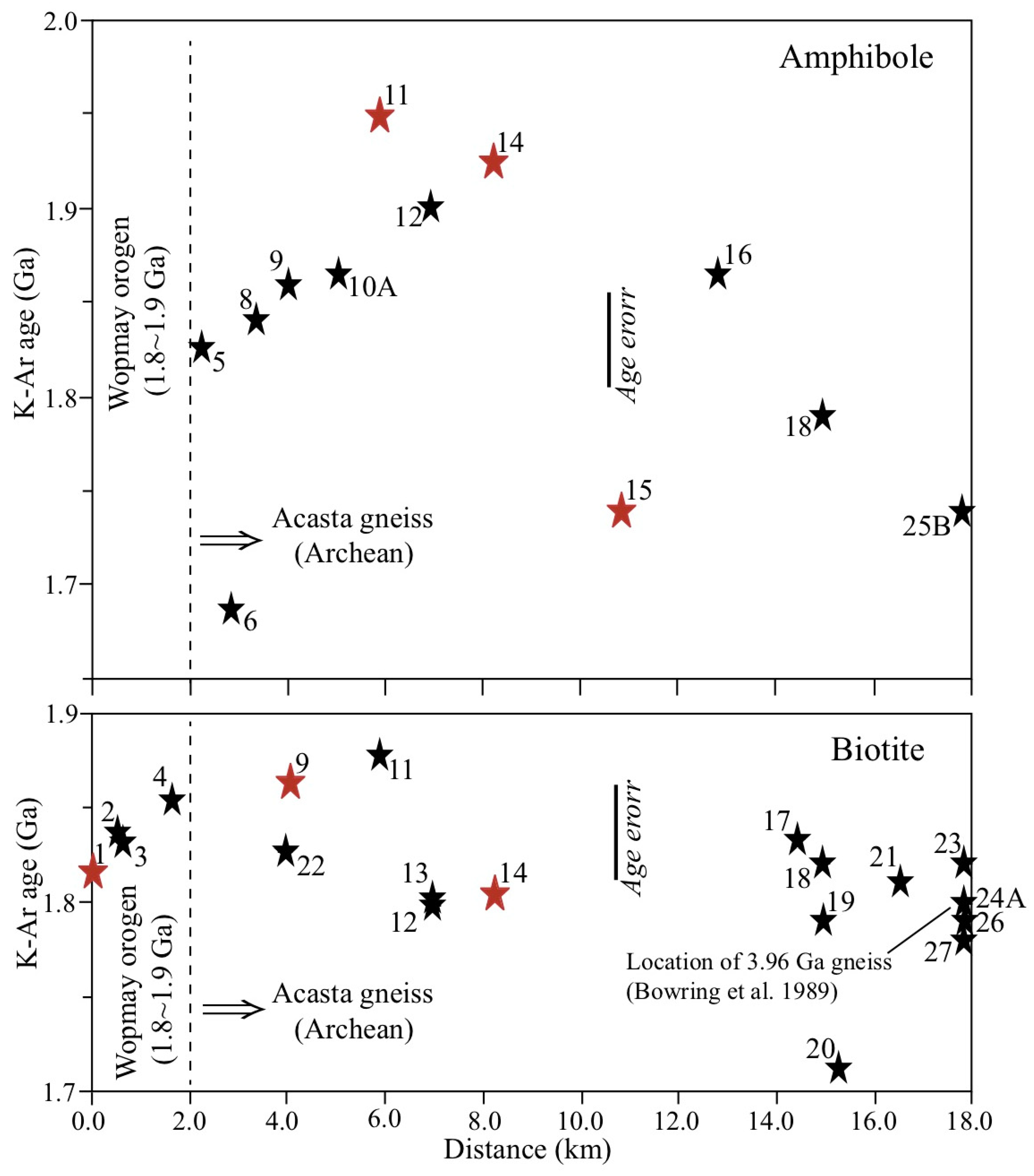

Table 1. The ages are plotted along a traverse 18 km east–west stretch of the boundary between the Wopmay orogen and the Acasta gneiss (

Figure 5).

The K-Ar biotite ages of the four Wopmay samples (Hwp 1, Hwp 2, Hwp 3, and Hwp 4) range from 1816 ± 18 Ma to 1854 ± 26 Ma, which is within the reported U-Pb zircon age range of the Wopmay orogen. The K-Ar biotite ages of the fifteen Acasta gneisses range from 1779 ± 25 Ma to 1877 ± 26 Ma (see

Table 1), except for the younger Hwp20 (1711 ± 25 Ma). The K-Ar amphibole ages range from 1737 ± 27 Ma to 1952 ± 27 Ma, except for the younger Hwp6 (1685 ± 25 Ma), giving larger age variation in comparison with the biotite ages.

5. Laser step-heating 40Ar/39Ar analyses

40Ar /

39Ar analyses of biotite and amphibole were carried out using the temperature-controlled laser step-heating method [

23,

24,

25]. Each mineral grain (ca. 0.5 mm in size) was placed in a 2 mm drill hole on an aluminum tray, together with a standard-age grain (3gr amphibole; [

26]), and calcium (CaSi

2) and potassium (synthetic KAlSi

3O

8 glass) salts for the Ca and K corrections, respectively. Subsequently, the trays were vacuum-sealed in a quartz tube. Neutron irradiation of the sample was carried out in the core of the 5 MW Research Reactor at Kyoto University (KUR) for 8 h using the hydraulic rabbit facility (a sample-capsule transferring system with hydraulic pressure). The fast neutron flux density was 3.9 × 10

13 n/cm2/ s and was confirmed to be uniform in the dimension of the sample holder (φ16 × 15 mm), as little variation in the J-values of the evenly spaced age standards was observed [

23]. The averaged J-values and the potassium and calcium correction factors are J = 0.00458 ± 0.00005, (40/39) K = 0.0155 ± 0.0030, (36/37) Ca = 0.000256 ± 0.000028 and (39/37) Ca = 0.000847 ± 0.000020, respectively.

Each mineral was analyzed with the step-heating technique using a 5 W continuous argon ion laser. The temperatures of the samples were monitored using an infrared thermometer with a precision of 3° within an area 0.3 mm in diameter [

24]. The single crystal was heated under a defocused laser beam at a given temperature for 30 s. The extracted gas was purified using a SAES Zr–Al getter (St 101) and kept at 400 °C for 5 min. Argon isotopes were measured using a custom-made mass spectrometer with a high resolution ([M/ΔM] = ca. 800), which allowed for the separation of hydrocarbon peaks, except for mass 36 [

25]. Typical blanks of the extraction lines are 4×10

−11, 2×10

−13, 3×10

−14, and 8× 10

−9 ccSTP for

36Ar,

37Ar,

39Ar, and

40Ar, respectively. Age spectra and

37Ar

Ca/

39Ar

K ratios of the analyzed samples are shown in

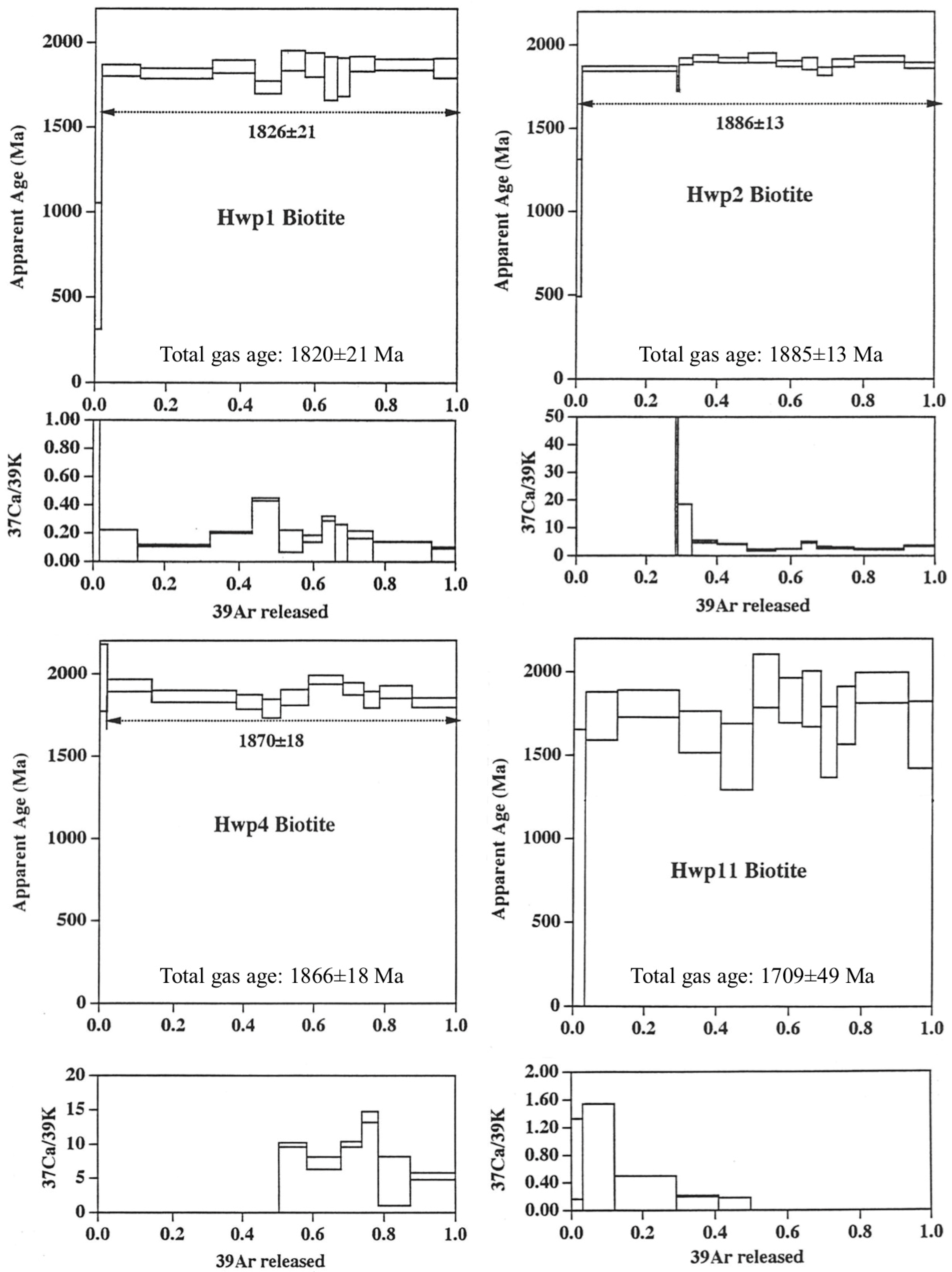

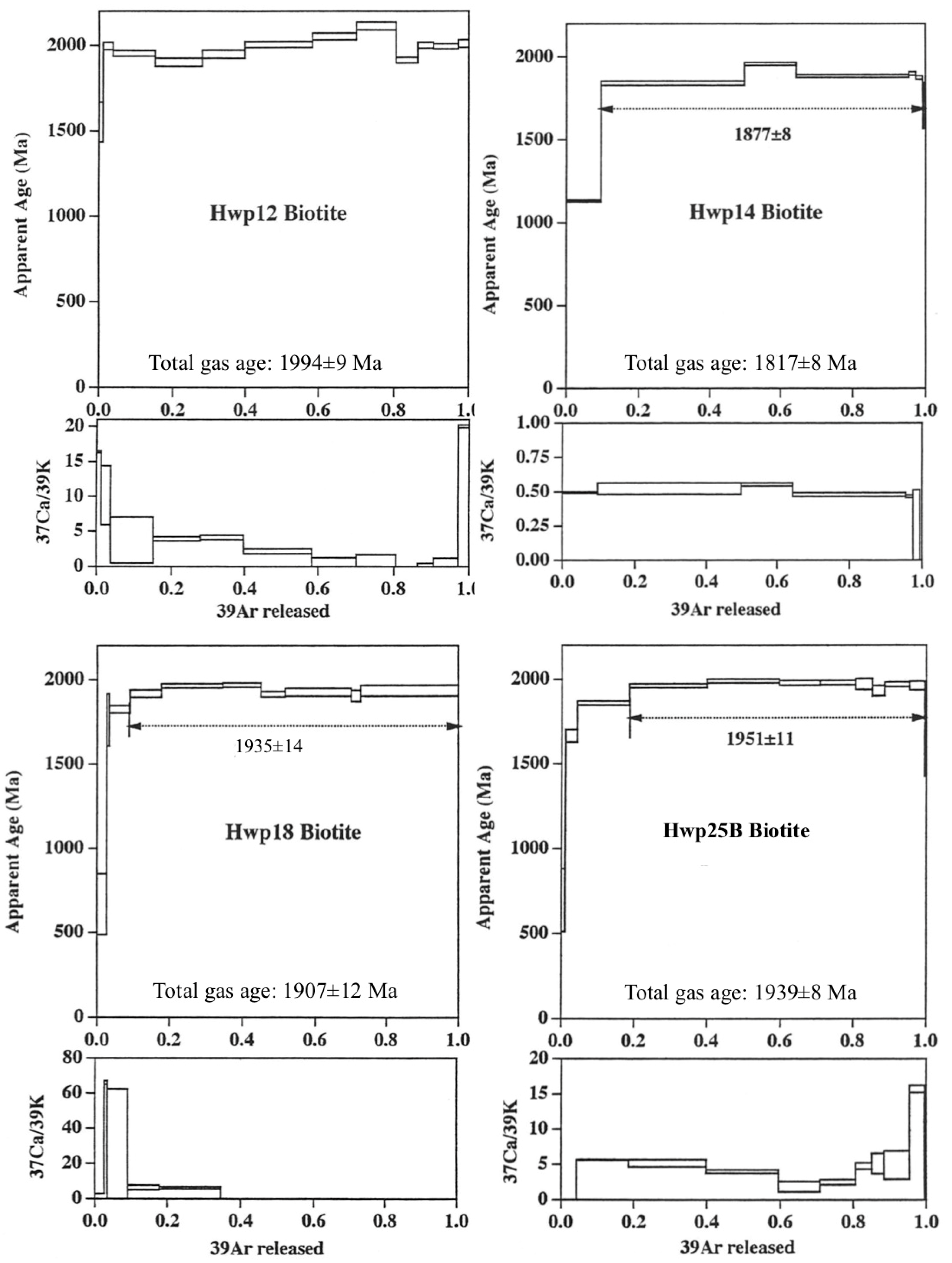

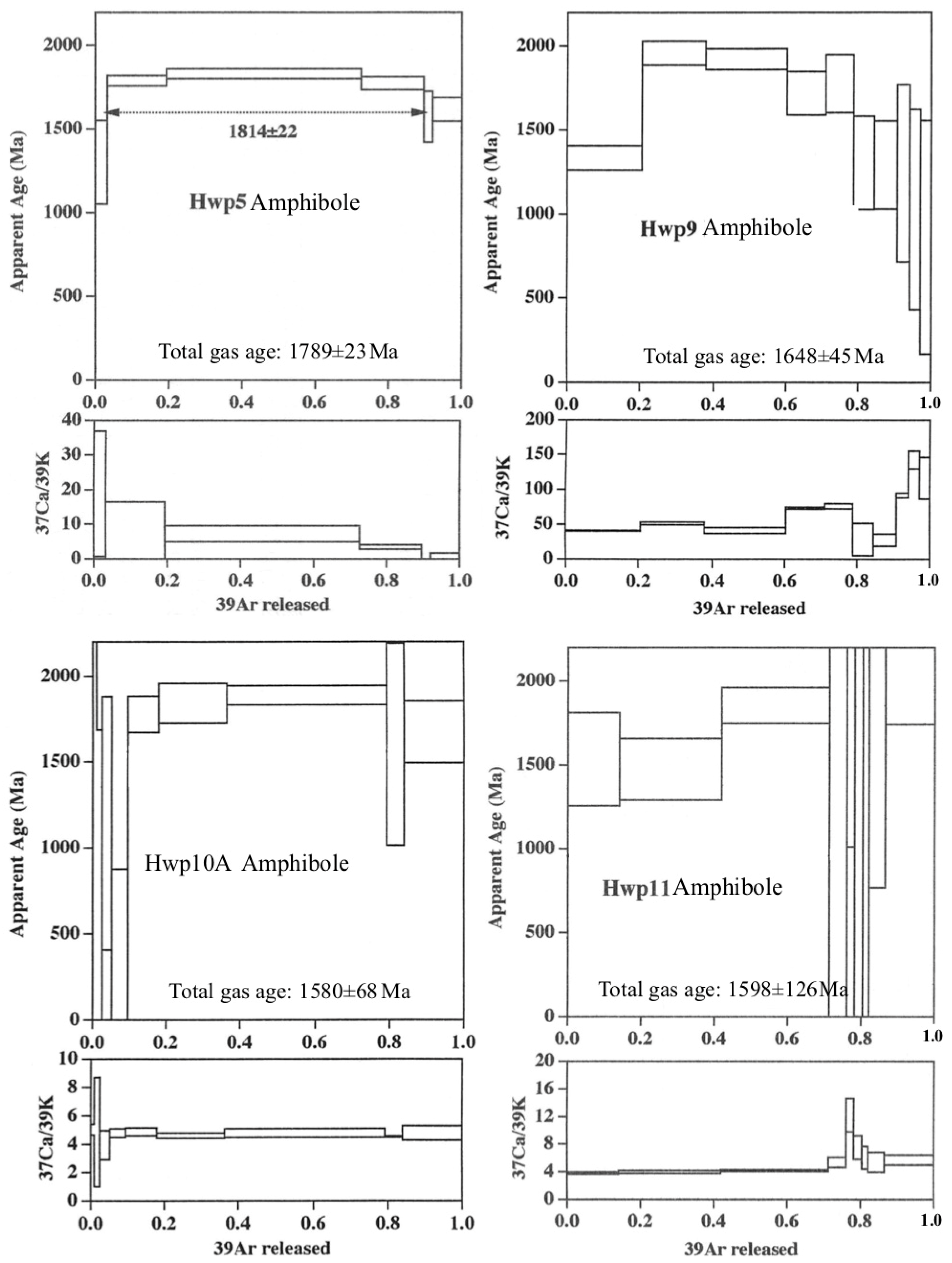

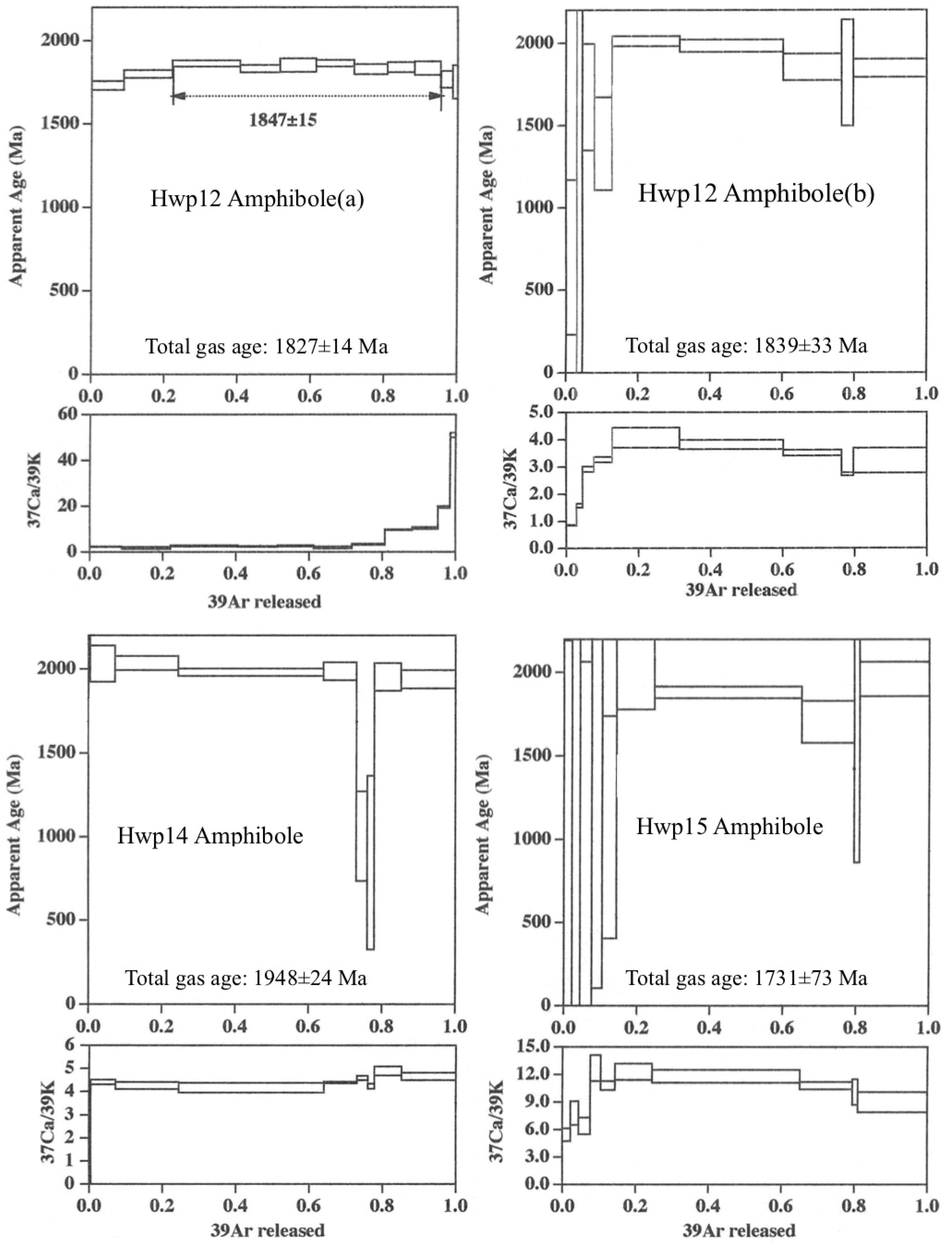

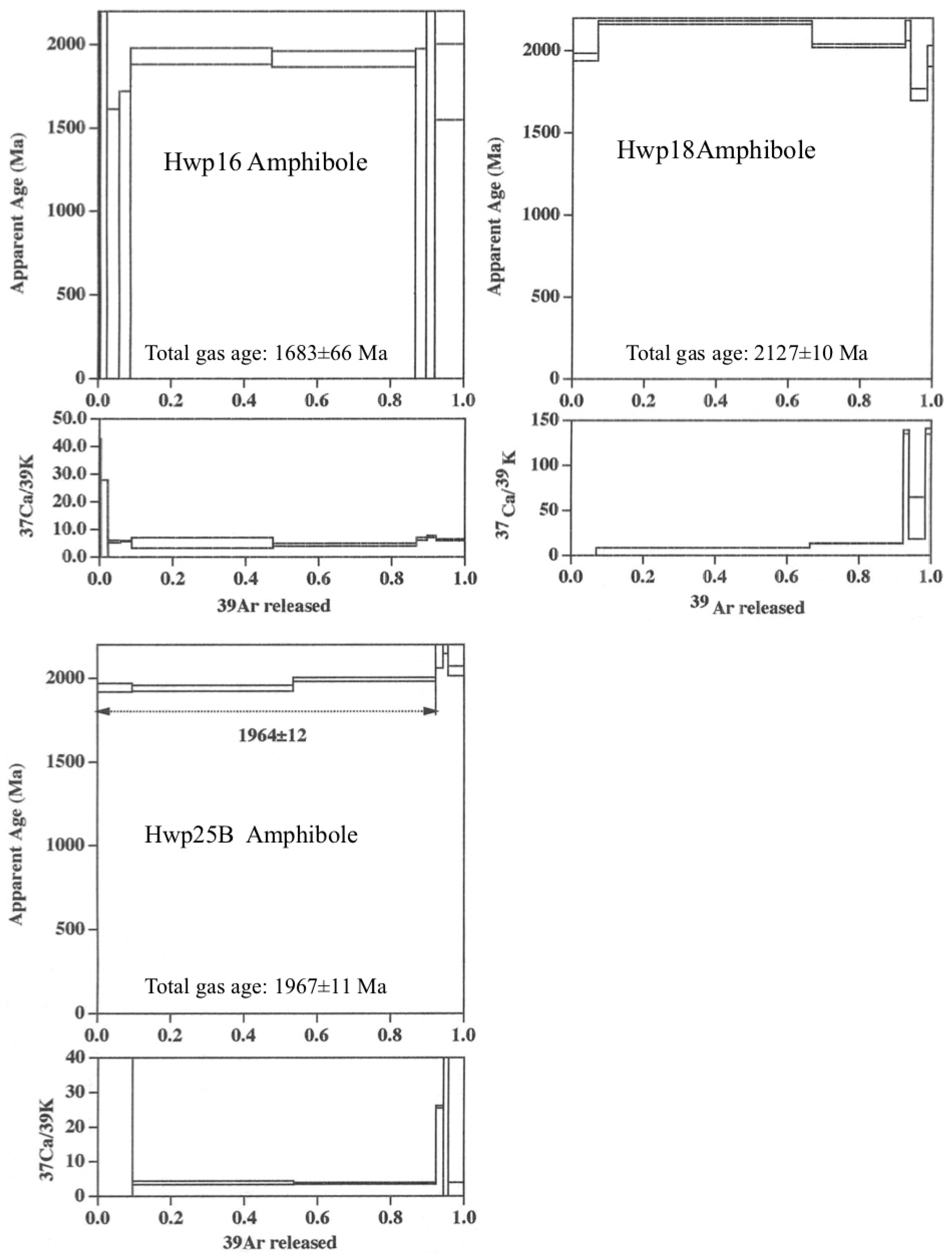

Figure 6.

As seen in

Figure 6, the

40Ar/

39Ar biotite analyses of the three samples (Hwp1, Hwp2, and Hwp4) from the Wopmay orogen give the plateau ages 1826 ± 21 Ma, 1886 ± 13 Ma, and 1870 ± 18 Ma, respectively. These plateau ages are the same as the total gas ages within the analytical error. However, the K-Ar biotite age (1837 ± 26 Ma) of Hwp2 is little younger than the

40Ar/

39Ar plateau age (1886 ± 13 Ma), suggesting that some biotite grains experienced argon loss. On the other hand, the

40Ar/

39Ar analyses of the biotite crystals from the Acasta gneiss show a variety of ages. Hwp 14, Hwp18, and Hwp25 show the plateau ages of 1877 ± 8 Ma, 1935 ± 14 Ma, and 1951 ± 11 Ma, respectively. These plateau ages are a little older than the total gas ages. This is due to the argon loss observed in the low temperature fractions. The plateaus of Hwp14 and Hwp18 are little older than the K-Ar ages of 1794 ± 25 Ma and 1819 ± 16 Ma, respectively. This is because, by chance, crystals with little argon loss were chosen for the analysis. The total gas age (1994 ± 9 Ma) of Hwp12 is significantly older than the K-Ar age (1799 ± 25 Ma). This may be because an excess argon bearing crystal was, by chance, chosen for the analysis. This crystal appears to be significantly older than 2000 Ma in the middle temperature fractions, suggesting that excess argon is trapped in the biotite crystal. Biotite may happen to trap the excess argon waves that occurred in the contact aureoles [

27] and in the regional metamorphic belts such as the Barrovian-type metamorphic belt, the eastern Tibetan Plateau [

28] and the Dora Maira Massif of Western Alps, Italy [

29]. This suggests that the Acasta gneiss originally contained biotite. The

40Ar/

39Ar analyses of the amphibole crystals show more varied age relations. Hwp5 and Hwp25 show consistent age relations between the plateau ages (1814 ± 22 Ma and 1964 ± 12 Ma) and the total gas ages (1789 ± 23 Ma and 1967 ± 11 Ma), respectively. Two crystals from Hwp12 were analyzed. Crystal (a) shows consistent age relations between the plateau ages (1847 ± 15 Ma) and the total gas ages (1827 ± 14 Ma). Crystal (b) shows no plateau age spectra and gives a total gas age of 1839 ± 33 Ma, which is similar to the age of crystal (a). This crystal has the apparent old age of 2000 Ma in the middle temperature fractions. The crystals of Hwp14 and Hwp18 have also the fractions older than 2000Ma. These old fractions are due to that the originally existed amphibole crystals formed in Archean were affected by the thermal events during the Wopmay orogeny., but did not fully reset.

6. Discussion

6.1. Wopmay orogen event

Based on zircon U-Pb geochronology, Guitreau et al. [

6] summarized the geological events that occurred at the Acasta Gneiss Complex, showing multi-stage events from 4.2 to 2.6 Ga; these are due to the multiple zircon formations in the tonalite–granite emplacement. They also proposed the Wopmay orogen event using the

40Ar /

39Ar ages of biotite and amphibole presented by Hodges et al. [

7]. We confirmed more clearly the existence of the Wopmay orogen event based on K-Ar and

40Ar /

39Ar analyses of biotite and amphibole from the Acasta Gneisses. This is an event that rejuvenated the K-Ar system ages of the biotite and amphibole of the Archean gneiss to the Proterozoic ages. This rejuvenation worked to reset the K-Ar systems of biotite and amphibole. The resetting of the white mica K-Ar system in the collisional orogenic belts is not always completed during high-pressure (HP)–ultra-high-pressure (UHP) metamorphism (cf. [

30] and references therein). This is because white mica has a high closure temperature (ca. 600 °C and above). Itaya et al. [

28] presented a variation diagram of the closure temperature of the biotite K-Ar system for different grain sizes and cooling rates based on the diffusion model proposed by Dodson [

31]. The diagram indicates that the closure temperature is ca. 420°C under a grain size of 1mm and a cooling rate of 1000 °C /Myr. A slower cooling rate and smaller grain size further reduces the closure temperature. The closure temperature of amphibole has been described as ca. 500°C [

32]. The closure temperature of the zircon U-Pb system depends on the nature of the zircon grains. Sano et al. [

33] posited that it is ca. 880°C when discussing the cooling history of the Acasta gneiss. These closure temperature relations mean that the thermal effect of the Wopmay orogen event must be 500–880 °C. This is because the amphibole has been rejuvenated, but the zircon has not.

6.2. Heat sources affecting the Acasta gneiss

The thermal effect took place over a range of 16km in the biotite and amphibole K-Ar system ages of the Acasta gneiss (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). This required a huge thermal heat source. The heat source that formed the Hepburn batholith is considered to be a candidate because the batholith is so large and its zircon U-Pb ages (ca. 1890 Ma by [

13]) are similar to the K-Ar system ages (see

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) of biotite and amphibole in the Acasta gneiss. Hildebrand et al. [

13] noted that the Hepburn batholith is in the Turmoli klippe, meaning that the batholith was brought to the present location after being formed in another region. However, the possibility exists that it was generated in situ.

The Coronation Supergroup described by Hildebrand et al. [

13] that lies to the east of the “Turmoli klippe” was deformed and metamorphosed [

1,

34]. The metamorphic grade increases toward to the Hepburn batholith from the eastern side, as revealed by the mineral zone distribution; namely, the chlorite, biotite, aluminosilicate, and K-Feldspar zones [

12]. This mineral paragenesis suggests metamorphism of the low P/T type. The garnet–biotite geothermometry in the pelitic rocks close to the Hepburn batholith gave the highest temperature of 765°C [

35]. The plutonic suit comprised more than 200 discrete pultons ranging widely in size, composition, tectonic fabric, and level of emplacement [

12]. The largest and most abundant intrusions are variably foliated and megacrystic, typically containing metasedimentary xenoliths, accessory garnet, and silimanite. The granites are peraluminous and have low magnetic susceptibility and moderately heavy whole-rock oxygen isotope ratios of 𝛅O

18 = 8 to 13 [

36]. These characteristics imply a strong metasedimentary contribution by anatexis [

12]. This situation is similar to that of the Cretaceous Ryoke metamorphic belt in southwest Japan. The belt comprises a Jurassic accretionary complex with Cretaceous Ilmenite-series granite [

37,

38]. The metamorphic grade of the metamorphosed complex increases from north to south where the migmatite zone is 700-850°C [

38]. Migmatite has drawn attention as a possible source for granitic magma. It has been speculated that anatectic melts are extracted from it and segregated to grow and coalesce, forming a pluton-sized magma body (e.g. [

40,

41,

42]).

6.3. Asthenospheric intrusion in the subduction system

Fukui et al. [

43] carried out systematic K–Ar age mapping along a N–S traverse of the Tia Complex, southern New England Fold Belt, eastern Australia. On the basis of the K–Ar ages and the available geological data, they argued that the eastward shift of a subduction zone system and subsequent magmatic activities by asthenospheric intrusion explain the formation of S-type granitoids and coeval low-P/high-T-type metamorphism in the Tia Complex. Imaoka et al. [

44] studied a 107 Ma lamprophyre dike in the Kinki district of the Tamba Belt, Kyoto Prefecture, SW Japan. They also noted that the episode of magmatism at 107 Ma extended regionally to Korea from the Kinki district through the Chugoku district and North Kyushu in SW Japan, as a result of slab roll-back at the eastern margin of Asia. This subduction rollback may play an important role in the formation of the Ilmenite-series granite in the Cretaceous Ryoke metamorphic belt in southwest Japan, as well as the Hepburn batholith in the Wopmay orogen.

The Hepburn plutons extend along the north–south direction (

Figure 1A). It is probable that an asthenospheric intrusion occurred in a strip along this direction. This asthenospheric intrusion enabled the formation of the Hepburn plutons and coeval low-P/high-T-type metamorphism in the Coronation supergroup, including the Akaitcho group. This suggests that its intrusion also occurred below the Acasta gneiss, existing on the extension of the N–S-extending Hepburn plutons. This asthenospheric intrusion could have a thermal effect on the Acasta gneiss, rejuvenating the K-Ar system ages of biotite and amphibole. The biotite K-Ar ages of the samples (Hwp23, Hwp24, Hwp26, and Hwp27) 16 km away from the boundary between the Wopmay orogen and the Acasta gneiss, are the same as the ages of the Wopmay rocks within the analytical error (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). These results indicate that the extent of the thermal effect is at least 16 km laterally from the asthenospheric intrusion axis. This extent is comparable with the width of the Hepburn plutons.

The biotite in the Acasta gneisses seem to have been reset to a significant degree by the thermal effect of the asthenospheric intrusion (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). However, amphibole crystals are not always completely reset. As seen in

Figure 6, amphibole crystal (a) of Hwp12 gives consistent age relations between the plateau ages (1847 ± 15 Ma) and the total gas ages (1827 ± 14 Ma), suggesting it was reset completely. The crystal (b) from the same sample shows no plateau age spectra and has the apparent old age of 2000 Ma in the middle temperature fraction. The amphibole crystals of Hwp14 and Hwp18 have also the fractions older than 2000Ma. This may be because the thermal effect took place around the closure temperature of amphibole.

7. Summary

Slave Province is a well-exposed Archean terrane located in the northwestern corner of the Canadian Shield. It is bordered by the Thelon–Taltson orogenic belt (2.0 to 1.9 Ga) to the southeast and the Wopmay orogenic belt (1.9 to 1.8 Ga) to the west. The Acasta gneisses are exposed along the Acasta River in the westernmost part of Slave province. Zircon U-Pb geochronology of the gneisses has been undertaken since the discovery of the 3.96 Ga gneiss in 1989, revealing multi-stage events from 4.2 to 2.6 Ga. The Wopmay orogen event has also been proposed to have occurred from the 40Ar/39Ar age of biotite and amphibole. We confirmed with greater certainty the existence of the Wopmay orogen event based on K-Ar and 40Ar /39Ar analyses of biotite and amphibole from the Acasta Gneisses, which were collected systematically along an 18 km east–west traverse through the boundary between the Wopmay orogen and the Acasta gneiss. This is an event that rejuvenated the K-Ar system ages of the biotite and amphibole of the Archean gneiss to the Proterozoic ages. We noted that the heat source that rejuvenated the K-Ar system ages could be the asthenospheric intrusion in the subduction system that took place due to the subduction rollback.

Supplementary Materials

The following materials are available online at

Preprints.org: Supplementary Figure 1 (SF1): Photomicrographs (crossed polars) of the Wopmay rocks and the Acasta gneisses

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.I. and H.H.; methodology, T.I. and H.H.; software, H.H.; resources, T.I. and H.H.; K-Ar and 40Ar/39Ar analyses; M.S. and H.H.; EPMA analyses, K. S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S. and H.H.; writing—review and editing, T.I., H.H. and T.T.; supervision and project administration, T.I.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The neutron irradiation experiment was carried out as part of the visiting researcher program in Kyoto University Reactor (KUR). We thank the staff of Kyoto University, and especially K. Takamiya for his help during the course of the experiment. H.H. also thanks P.F. Hoffman and S.A. Bowring for their guidance in the Acasta area, and C.E. Isachsen, M. Arima, H. Sakai, Y. Koide, and H. Baba for their help in the field. The sampling was partly supported by the Earth History Project led by S. Maruyama.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hoffman, P.F. Precambrian geology and tectonic history of North America, in Bally, A.W., and Palmer, A.R., eds., The Geology of North America: An Overview: Boulder, Colorado, Geological Society of America, Geology of North America 1989, A, 447–512.

- Bowring, S.A.; Grotzinger, J.P. Implications of new chronostratigraphy for tectonic evolution of Wopmay orogen, northwest Canadian Shield: American Journal of Science 1992, 292, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Bowring, S. A.; Williams, I. S.; Compston, W. 3.96 Ga gneisses from the Slave province, Northwest Territories, Canada. Geology 1989, 17(11), 971–975. [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, T.; Horie, K.; Komiya, T.; Maruyama, S.; Hirata, T.; Hidaka, H.; Windley, B. F. 4.2 Ga zircon xenocryst in an Acasta gneiss from northwestern Canada: Evidence for early continental crust. Geology 2006, 34(4), 245–248. [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, T.; Komiya, T.; Ueno, Y.; Katayama, I.; Uehara, Y.; Maruyama, S.; Hirata, T.; Johnson, S. P.; Dunkley, D. J. Geology and zircon geochronology of the Acasta Gneiss Complex, northwestern Canada: New constraints on its tectonothermal history. Precanbrian Research 2007, 153, 179-208. [CrossRef]

- Guitreau, M.; Mora, N.; Paquette, J-L. Crystallization and disturbance histories of single zircon crystals from Hadean-Eoarchean Acasta gneisses examined by LA-ICP-MS U-Pb traverses. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 2017, 19, 272-291. [CrossRef]

- Hodges, K.V.; Bowring, S.A.; Coleman, D.S.; Hawkins, D.P.; Davide, K. L. Multi-stage thermal history of the ca. 4.0 Ga Acasta gneisses. Eos transactions AGU 1995, 76(17), Abstract F708.

- Padgham, W.A.; Fyson, W.K. The Slave Province: a distinct Archean craton. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1992, 29, 2072–2086. [CrossRef]

- van Breemen, O.; Davis, W.J.; King, J.E. Temporal distribution of granitoid plutonic rocks in the Archean Slave Province, northwest Canadian Shield. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1992, 29, 2186– 2199. [CrossRef]

- Bowring, S.A.; Housh, T.B.; Isachsen, C.E. The Acasta Gneisses: Remnant of Earth’s Early Crust. Origin of the Earth. Oxford University Press, New York.1990.

- Bowring, S.A.; Williams, I.S. Priscoan (4.00–4.03Ga) orthogneisses from northwestern Canada. Contrib. Miner. Petrol. 1999, 134, 3–16.

- Hoffman, P.F.; Tirrul, R.; King, J.E.; St-Onge, M.R.; Lucas, S.B. Axial projections and modes of crustal thickening, eastern Wopmay orogen, northwest Canadian Shield, in Clark, S.P., Jr., ed., Processes in Continental Lithospheric Deformation: Geological So- ciety of America Special Paper 1988, 218, 1–29.

- Hildebrand, R.S.; Hoffman, P.F.; Bowring, S.A. The Calderian orogeny in Wopmay orogen (1.9 Ga), northwestern Canadian Shield. GSA Bulletin 2010, 122 (5/6), 794–814. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, P.F., Evolution of an early Proterozoic continental margin: The Coronation geosyncline and associated aulacogens of the northwestern Canadian Shield: Royal Society of London Philosophical Trans- actions 1973, 273, ser. A, 547–581.

- Bowring, S.A.; Grotzinger, J.P. Implications of new chronostratigraphy for tectonic evolution of Wopmay orogen, northwest Canadian Shield. American Journal of Science 1992, 292, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, P.F.; St-Onge, M.R.; Easton, R.M.; Grotzinger, J.; Schulze, D.L. Syntectonic plutonism in north-central Wopmay orogen (early Proterozoic), Hepburn Lake map area, District of Mackenzie, in Cur- rent Research, Part A: Geological Survey of Canada Paper 80–1 1980, 171–177.

- Housh, T.; Bowring, S.A.; Villeneuve, M. Lead isotopic study of early Proterozoic Wopmay orogen, NW Canada: Role of continental crust in arc magmatism: The Journal of Geology 1989, 97, 735–747. [CrossRef]

- Bowring, S.A.; Podosek, F.A. Nd isotopic evidence from Wopmay orogen for 2.0–2.4 Ga crust in western North America: Earth and Planetary Science Letters 1989, 94, 217–230. [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, R.S.; Bowring, S.A.; Housh, T. The Medial zone of Wopmay orogen, District of Mackenzie, in Current Research, Part C: Geological Survey of Canada Paper 90–1C 1990, 167–176.

- Nagao, K.; Nishido, H.; Itaya, T.; Ogata, K. K–Ar age determination method. Bulletin of Hiruzen Research Institute 1984, 9, 19–38.

- Itaya, T.; Nagao, K.; Inoue, K.; Honjou, Y.; Okada, T.; Ogata, A. Ar isotope analysis by a newly developed mass spectrometric system for K–Ar dating. Mineralogical Journal 1991, 15, 203–221. [CrossRef]

- Steiger, R.H.; Jäger, E. Subcommission on geochronology: Convention on the use of decay constants in geo– and cosmochronology. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 1977, 36, 359–362. [CrossRef]

- Hyodo, H.; Kim, S.; Itaya, T.; Matsuda, T. Homogeneity of neutron flux during irradiation for 40Ar/39Ar age dating in the research reactor at Kyoto University. Journal of Mineralogy and Petrological Sciences 1999, 94, 329–337. [CrossRef]

- Hyodo, H.; Itaya, T.; Matsuda, T. Temperature measurement of small minerals and its precision using Laser heating. Bulletin of Research Institute of Natural Sciences, Okayama University of Science 1995, 21, 3–6 (in Japanese with English Abstract).

- Hyodo, H.; Matsuda, T.; Fukui, S.; Itaya, T. 40Ar/39Ar age determination of a single mineral grain by Laser step heating. Bulletin of Research Institute of Natural Sciences, Okayama University of Science 1994, 20, 63–67 (in Japanese with English Abstract).

- Roddick, J.C. High precision intercalibration of 40Ar–39Ar standards. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1983, 47, 887–898. [CrossRef]

- Hyodo, H.; York, D. The discovery and significance of a fossilized radiogenic argon wave (argonami) in the earth’s crust. Geophysical Research Letter 1993, 20, 61–64. [CrossRef]

- Itaya, T.; Hyodo, H.; Tsujimori, T.; Wallis, S.; Aoya, M.; Kawakami, T.; Gouzu, C. Regional-Scale Excess Ar wave in a Barrovian type metamorphic belt, eastern Tibetan Plateau. Isl. Arc 2009, 18(2), 293-305. [CrossRef]

- Itaya, T.; Hyodo, H.; Imayama, T.; Groppo, C. Laser step-heating 40Ar/39Ar analyses of biotites from meta-granites in the UHP Brossasco-Isasca Unit of Dora-Maira, Italy. Journal of Mineralogical and Petrological Sciences 2018, 113, 171-180. [CrossRef]

- Itaya, T. K-Ar phengite geochronology of HP-UHP metamorphic rocks-An in-depth review. J. Mineral. Petrol. Sci. 2020, 115(1), 44-58. [CrossRef]

- Dodson, M.H. Closure temperature in cooling geochrono- logical and petrological systems. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1973, 40, 259–274. [CrossRef]

- Harrison T. M. Diffusion of 40Ar amphibole. Contribution to Mineralogy and Petrology 1981, 78, 324–331. [CrossRef]

- Sano, Y.; Terada, K.; Hidaka, H.; Yokoyama, K.; Nutman, A.P. Palaeoproterozoic thermal events recorded in the ~4.0 Ga Acasta gneiss, Canada: Evidence from SHRIMP U-Pb dating of apatite and zircon. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1999, 63 (6), 899-905. [CrossRef]

- St-Onge, M.R. Zoned poikiloblastic garnets: Docu- mentation of P-T paths and syn-metamorphic uplift through thirty kilometers of structural depth, Wopmay orogen, Canada: Journal of Petrology 1987, 28, 1–21.

- St-Onge, M.R. Geothermometry and geobarometry in pelitic rocks of north-central Wopmay orogen (early ProterozoicNorthwest Territories, Canada. Geological Society of America Bulletin 1984, 95, 196-208. [CrossRef]

- Lalonde, A.E. Hepburn intrusive suite: Peraluminous plutonism within a closing back-arc basin, Wopmay orogen, Canada. Geology 1989, 17, 261–264. [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, S. The magnetite-series and ilmenite-series granitic rocks. Mining Geology 1977, 27, 293-305. [CrossRef]

- Isozaki, Y.; Aoki, K.; Nakama, T.; Yanai, S. New insight into a subduction-related orogen: Re- appraisal on geotectonic framework and evolution of the Japanese Islands. Gondwana Research 2010, 18, 82-105. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, T.; Takahashi, M.; Imaoka, T.; Shimura, T. Granitic rocks. From Moreno, T.; Wallis, S.; Kojima, T.; Gibbons. W. (eds). The geology of Japan. Geological Society, London 2016, 251-272.

- Ikeda, T. Pressure-Temperature conditions of the Ryoke metamorphic rocks in the Yanai district, SW Japan. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 2004, 146, 577-589. [CrossRef]

- D’Lemons, R.S.; Brown, M.; Strachan R.A. Granite magma generation, ascent and emplacement within a transpressional orogen. Journal of the Geological Society, London 1992, 149, 487-490. [CrossRef]

- Bons, P.D.; Arnold, J.; Elburg, M.A.; Kalda, J.; Soesoo, A.; Milligan, B.P. Melt extraction and accumulation from partially molten rocks 2004, Lithos, 78, 25-42. [CrossRef]

- Fukui, S.; Tsujimori, T.; Watanabe, T.; Itaya, T. Tectono-metamorphic evolution of high-P/T and low-P/T metamorphic rocks in the Tia Complex, southern New England Fold Belt, eastern Australia: Insights from K–Ar chronology. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 2012, 59, 62-69. [CrossRef]

- Imaoka, T.; Kawabata, H.; Nagashima, M.; Nakashima, K.; Kamei, A.; Yagi, K.; Itaya, T.; Kiji, M. Petrogenesis of an Early Cretaceous lamprophyre dike from Kyoto Prefecture, Japan: Implications for the generation of high-Nb basalt magmas in subduction zones. Lithos 2017, 290-291, 18-33. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).