1. Introduction

As part of COVID-19 pandemic response efforts, over 13.5 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines have been administered globally within the shortest time ever for the introduction of a new vaccine [

1,

2,

3]. The COVID-19 pandemic required a departure from ‘business-as-usual’ vaccine delivery approaches, to rapidly reduce mortality and morbidity, protect health systems, and restore socio-economic activities as quickly as possible [

4]. Mass vaccination campaigns were used as a main delivery approach to reach target populations quickly and widely. This approach puts a strain on essential immunization and other programmes [

2,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Health workers and resources were diverted away from the provision of essential health services. Furthermore, it is estimated that mass vaccination campaigns cost three times as much as the delivery of COVID-19 vaccine in routine services,

1 and some countries had to rely on donor funding, which hampered sustainability. In some instances, the rapid response required parallel pandemic response coordination structures outside immunization programmes. Consequently, there was a need for guidance on the planning and implementation of a more sustainable harmonized approach to delivering the COVID-19 vaccines as part of broader health systems.

By 2022, the trajectory of the COVID-19 pandemic remained uncertain, and WHO laid out possible scenarios for how it could evolve. With the most likely scenario being the continued circulation of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the need for periodic booster doses (particularly for those groups at higher risk of hospitalization and death)[

11], WHO and UNICEF worked to develop a guidance document outlining considerations for the integration of COVID-19 vaccination into immunization programmes and PHC [

12]. This paper summarizes the approach to, and lessons learned during the development of a global guidance document in an acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic and describes some examples of its early use across a range of contexts. These lessons are expected to inform the development and use of the global guidance for future pandemics, and to inspire guidance for the integration of vertical programming into national health systems.

Rationale for Developing the Guidance.

The prolonged and rapidly evolving nature of the COVID-19 pandemic required the development of rigorous and timely guidance to respond to the emerging needs of countries for a longer-term sustainable delivery model. Some countries have already taken steps towards integrating COVID-19 vaccination into their broader health system, and exploring new entry points for vaccination to identify and reach high-priority populations, mainly adults [

12,

13]. Furthermore, there was an opportunity to capitalize on the COVID-19 vaccination investments, innovations, and new tools used for the pandemic response, towards building more resilient health systems and delivery platforms reaching people who are not traditionally covered by childhood immunization programmes. This was also critical to guide government and donor investments to mainstream COVID-19 vaccination. Finally, integrating COVID-19 vaccination within other health service delivery platforms and programmes increases the opportunity for a more people-centered approach by delivering packages of health services that better respond to people’s needs across their life course, in alignment with the goals of the Immunization Agenda 2030 (IA2030) and PHC agenda [

14].

2. Approach to Developing the Guidance

The development of the global COVID-19 integration guidance aligned with the steps of both the WHO-INTEGRATE and the GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks [

15,

16,

17]. The development process involved an iterative process of the three cardinal steps mentioned in the GRADE EtD, including (1) Problem definition; (2) Evidence-informed assessments; and (3) Drawing conclusions, as indicated in

Figure 1. Field experiences emerging from countries indicated that some opportunistic integration of COVID-19 vaccination was happening. The document leveraged the more than 40 countries’ experiences of integrating COVID-19 vaccination, structured and analyzed by the different health system building blocks [

13,

18,

19], which helped the definition of problems that needed to be addressed. EtDs principles were used in summarizing and deciding on evidence to include in the guidance, including the quality of evidence, feasibility, equity, and ethical considerations.

A joint task force with membership across UNICEF and WHO was constituted in January 2022 to lead efforts to develop and disseminate the guidance. The task force defined the problem, collated, and reviewed evidence, previous guidance to be consulted, and country experiences, and made decisions concerning the content of the guidance. The methodology deployed by the task force can be summarized into four main work streams conducted in parallel and is described in detail in Annex 1 of the guidance document [

12]. These were:

2.1. Workstream 1 – Publications Review

This involved a review of WHO and UNICEF documents described as guidance, manuals, or tools that refer to the integration of health interventions or other health programmes, or vaccination relevant to immunization, COVID-19, PHC, and integration, published after 2015. This scoping was conducted to ensure consistency with previous publications related to integration, bringing together relevant guidance into one document that cohesively provides considerations for COVID-19 vaccination integration. These documents informed the definition and principles of integration, the scope of the document, benefits, risk analysis, and how to operationalize integration.

2.2. Workstream 2 – Rapid Survey and Interviews

To better understand the status of COVID-19 vaccine integration across countries, including its perceived opportunities and risks, WHO and UNICEF conducted a concurrent joint survey targeting country and regional office colleagues. A semi-structured questionnaire was developed that comprised both Likert-like and open-ended questions developed and uploaded to Survey Monkey, and responses were received from WHO (five regional offices and 41 country offices) and UNICEF (six regional offices and 34 country offices). The survey findings shed light on the benefits and risks associated with integration.

2.3. Workstream 3 – Stakeholder Consultations

Consultations were conducted at WHO and UNICEF offices (at headquarters, regional, and country level), Gavi and other global health stakeholders. They included immunization, social behaviour change, and health systems experts, to enable a better understanding of the benefits and risks of integration of COVID-19 vaccination, and how integration had already been achieved in different settings. Additional country examples of integration of COVID-19 vaccination for each of the health system building blocks, and demand promotion, including community engagement, were compiled. The findings from these consultations contributed to the sections on country experiences, how to operationalize integration, and generating further evidence.

2.4. Workstream 4 – Draft Development

Based on the publications review, rapid survey, and consultations, an initial version was drafted and circulated to WHO, UNICEF, Gavi, and other relevant stakeholders for input and comments. The working draft, including a readiness assessment checklist, was uploaded to a shared folder and the task team reviewed and strengthened the guidance based on suggestions received. A more advanced version of the guidance was discussed with immunization and health system experts who are members of the IA2030 – Strategic Priority 1: PHC working group, and Strategic Priority 4: Life Course and Integration working group. Comments and inputs received were consolidated and discussed by the task team, and decisions were made to include or expunge suggestions. Workstreams 3 and 4 were iterative and built on each other. A professional writer carried out a detailed review and copy-editing.

3. Applications: Evidence from Early Use

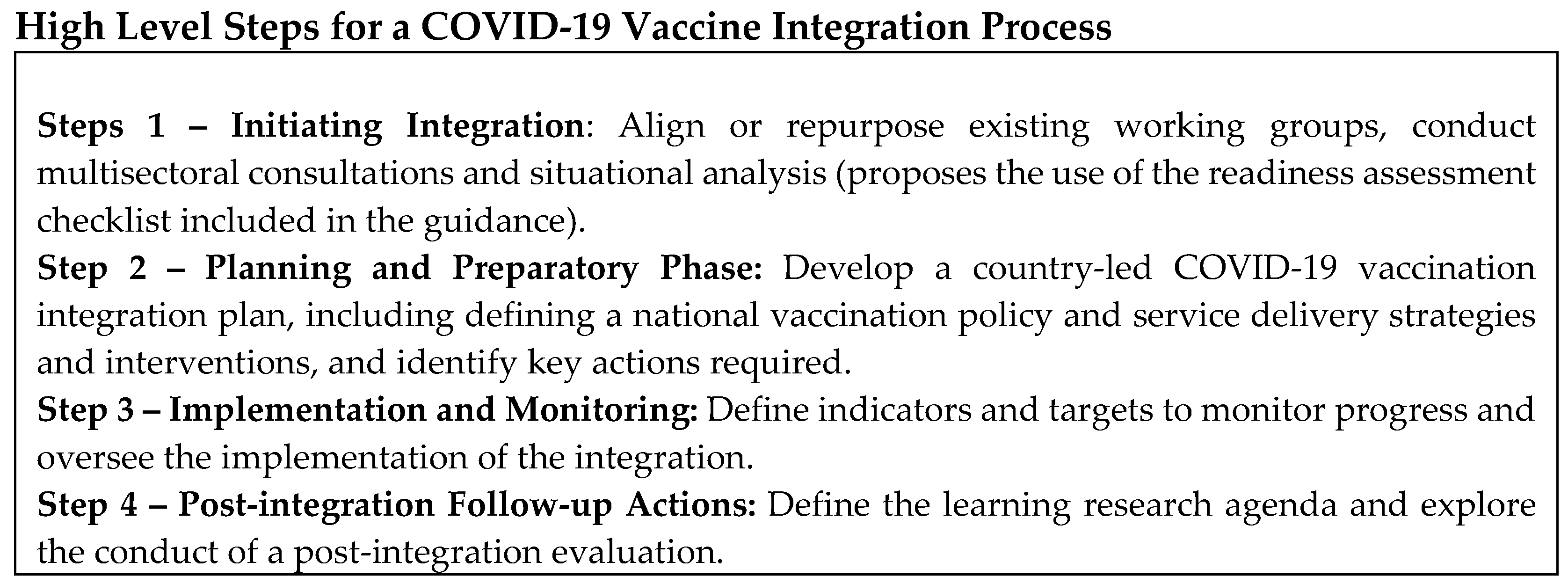

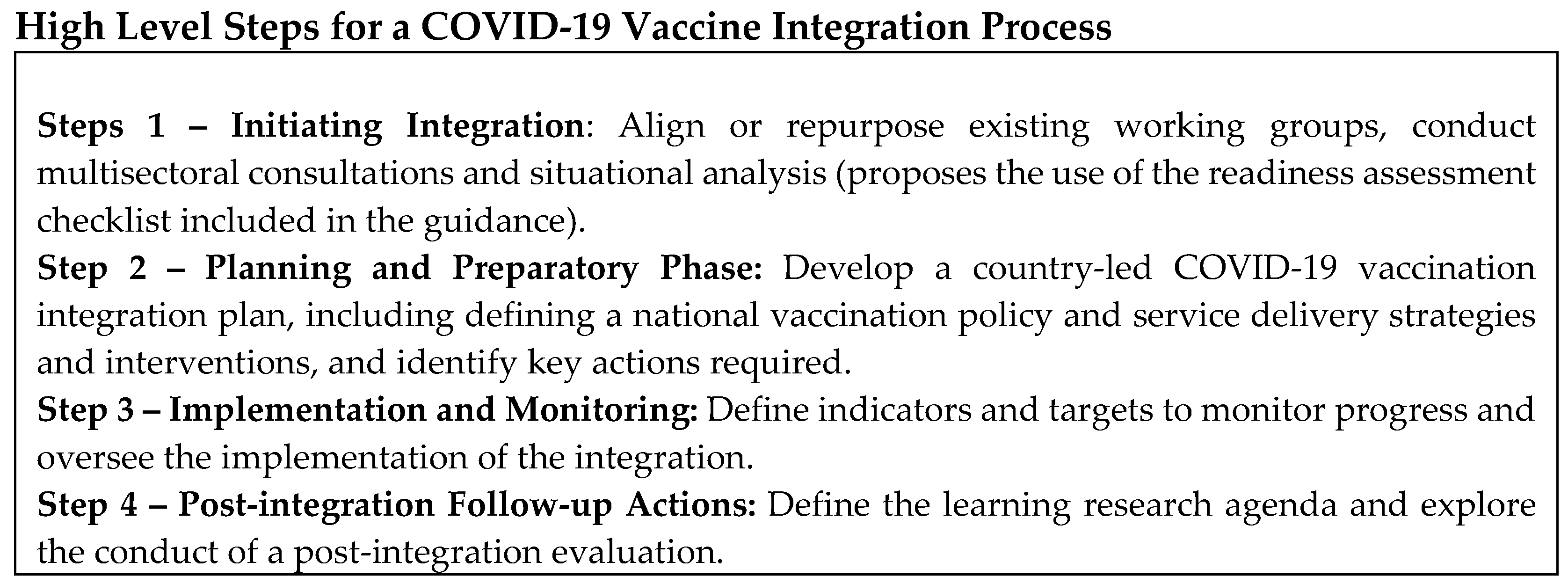

The first version of the guidance was published in July 2022, and proposed four steps towards integrating COVID-19 vaccines:

This version was broadly disseminated and presented at several webinars, meetings, workshops, and other relevant forums targeting global, regional, national, and subnational stakeholders. Documentations of early use are summarized below.

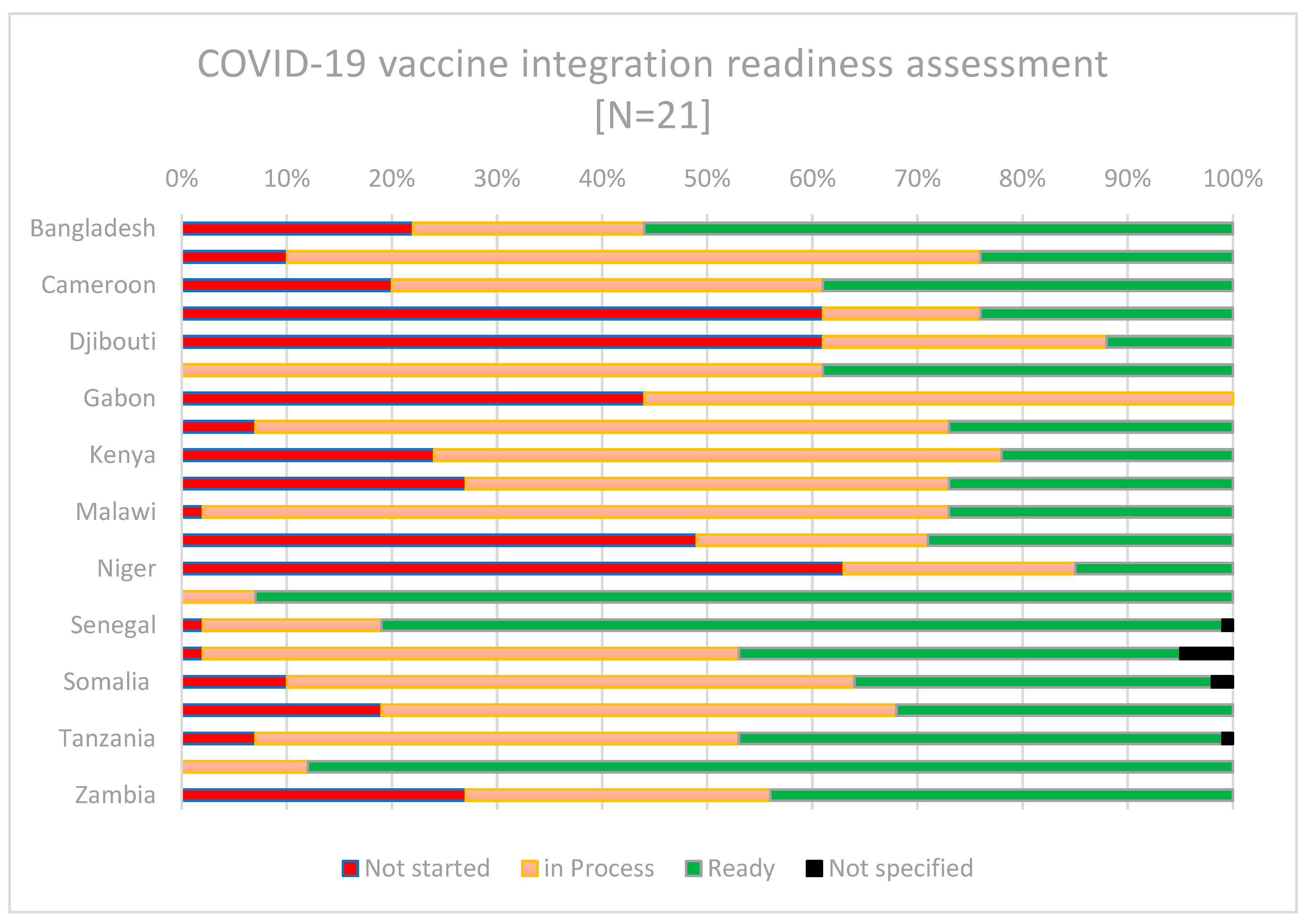

3.1. Use of the Guidance to Support Country Readiness Assessment of COVID-19 Vaccine Integration

Data on the countries’ self-reported readiness for integration was presented during the ‘COVID-19 vaccine stock take meeting’ in May 2023, facilitated by the COVID-19 Vaccine Delivery Partnership (CoVDP). The CoVDP was a partnership between WHO, UNICEF, and Gavi to support countries in their COVID-19 vaccine delivery efforts, with a focus on the 34 countries with the lowest coverage as of January 2022. The event saw the participation of more than 30 countries, most of which used the guidance checklist (in advance of the meeting) [

20], which facilitated the identification of current and anticipated enablers and challenges, and a way forward for the integration of COVID-19 vaccination into PHC. The readiness checklist allows self-assessment of between four and nine specific action items under eight blocks (leadership, health financing, demand and community engagement, service delivery, health workforce, health information system, access to essential medicines, and monitoring and evaluation). An overall score is proportioned based on the number of actions “completed”, “in progress” or “not started”. A summary of the country readiness data as presented in the meeting is shown in

Figure 2 below.

There was a wide variation in the self-reported readiness of countries to integrate COVID-19 vaccines, and their status may have changed since May 2023. While countries including Chad, Djibouti, Gabon, Mali, and Niger, reported relatively low readiness for integration or the initiation of steps towards integration, others including Nigeria, Senegal, and Uganda reported higher readiness.

The enablers identified by countries that reported being mostly ready included the presence of a COVID-19 vaccination integration plan and budgetary allocations. Others mentioned integration as necessary for sustaining their PHC services and leveraging the use of existing programmes to boost COVID-19 vaccination. The challenges reported included an absence of a holistic national strategy for COVID-19 vaccine integration and competing priorities, including other disease outbreak responses and natural disasters. Some countries requested additional technical assistance to support the prioritization and development or rollout of their integration plans in alignment with the global guidance.

3.2. Inclusion of Integration of COVID-19 Vaccination in Country Funding Proposals

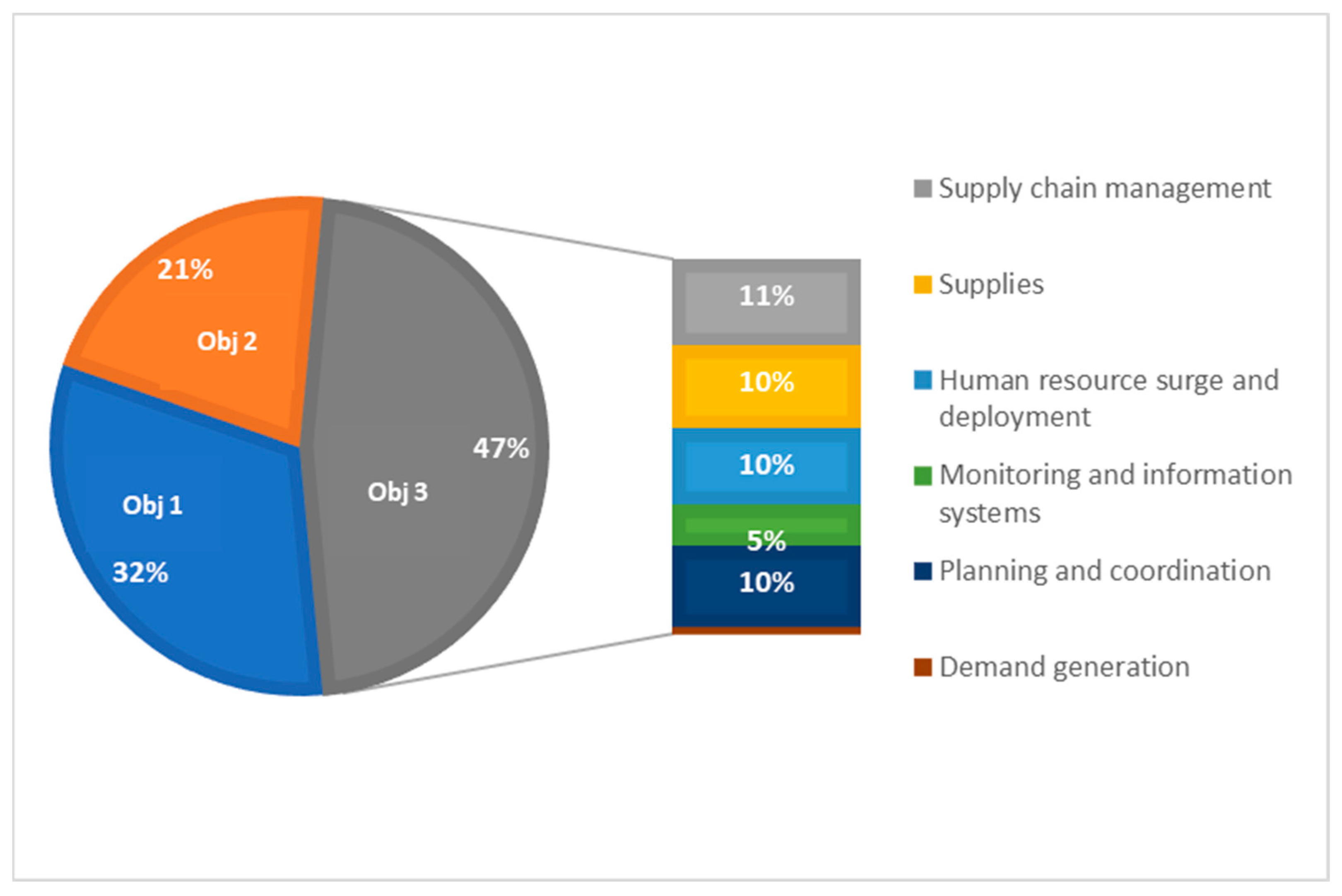

Gavi has provided operational funding to support countries in their COVID-19 vaccination efforts through the COVAX initiative. With the evolution of the pandemic and the emerging funding needs of countries, the third window of the COVID-19 Vaccine Delivery Support (CDS3) allowed countries to seek support for three objectives: (1) acceleration of vaccination of high and highest-risk populations (as defined by the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE)); (2) rapid delivery scale-up to reach country targets for adult vaccination; and (3) integration of COVID-19 vaccination into routine immunization (RI) to achieve sustainable benefits. The first and the second windows of support (CDS1 and CDS2) did not include integration of COVID-19 vaccination in their scope. The CDS3 timeframe for 91 eligible low- and middle-income economy countries (LMICs) to submit their proposals to Gavi was between September and November 2022. We hypothesize that the existence of programmatic guidance increased the appetite of countries to plan for the integration of COVID-19 vaccination into broader health systems, aided by the several discussions and engagements following the dissemination of the guidance. Of the 52 CDS3 applications from Gavi-eligible countries, an estimated 53% were made to support the integration of COVID-19 vaccination into routine immunization and PHC, 22% related to the acceleration of vaccination of high-risk group populations, and 30% related to rapid scale-up to reach national COVID-19 vaccine coverage targets. The prioritized activities included: strengthening COVID-19 vaccine delivery strategies (including primary care services and outreach/home visits, and engagement with the private sector, e.g., pharmacies); updating operational guidelines to standardize the integration of COVID-19 vaccination into RI; developing integrated microplanning to promote the use of primary care services at the community level to sustain immunization coverage, including data collection of COVID-19 vaccination into RI information systems; upgrading the capacity of cold chain and logistics systems for integrated management of RI and COVID-19 vaccination (including bundled vaccine and supply transportation); and updating social and behavioral change communication strategies (e.g., faith networks, community, and local influencers, strengthened social listening mechanisms to improve understanding of community concerns regarding integrated services).

A deep-dive into post-implementation data from 30 non-Gavi-eligible countries that submitted proposals for CDS3 (referred to as AMC30)

2 showed that close to half of the resources requested (47%) were to support COVID-19 integration efforts (

Figure 3). Despite the high proportion of activities related to integration, there was a lot of variation in how countries defined integration activities. Activities were largely planned to support the strengthening of supply chain management and supplies, planning and coordination, and human resource surge and deployment.

When asked to report on whether there has been a decision to integrate COVID-19 vaccination into routine immunization or primary care systems, half (15) of the countries responded that there was a plan or decision to integrate COVID-19 vaccination, and a few had already included COVID-19 vaccine into their national immunization programmes (e.g., Bolivia, the Republic of Moldova and Sri Lanka)[

21]. Countries continue to face operational challenges, including balancing in-country procedures, and the complexity of coordination, logistics, and rapid scale-up within the limited amount of time available to implement emergency resources. Acknowledging that the nature of CDS3-funded activities, particularly regarding COVID-19 vaccine integration, requires longer timelines for implementation, alignment with competing priorities and processes within countries, extensive stakeholder mapping, engagement, and costing support, the Gavi Board approved a non-cost extension of CDS3 for eligible countries for 2024 and 2025 [

22].

4. Discussion

The continuous evolution of the SARS-CoV-2, with the frequent emergence of new variants, often created a situation requiring rapid development or continuous updating of guidance and tools, in a context of high uncertainty. Like other guidance documents developed during the pandemic, the COVID-19 integration global guidance was developed without the privilege of face-to-face interaction. However [

23], the overall guidance development and application process aligned well with the available evidence to decision (EtD) frameworks and was based on a tripod of defining the problem, assessing the evidence, and drawing conclusions [

15,

16,

17]. Some of the integration efforts that happened ahead of the dissemination of the guidance were more opportunistic than strategic, with countries reporting facing challenges in operationalizing the integration of COVID-19 vaccination. Informed by these countries’ experiences and leveraging existing health system frameworks, the guidance identified four concrete steps for countries to initiate and plan for integration as earlier listed. These steps were consolidated following robust engagement and feedback and simplified to make the process more practicable and agile for countries. The concept of initiating integration and preparatory work that includes a readiness assessment provides a robust foundation for methodically planning and executing COVID-19 vaccine integration. As shown by the early use evidence, several countries were able to adapt the readiness assessment and report to meet their needs, and confidently report their status. This could suggest that the guidance spoke to the country’s needs. It is anticipated that these countries should also be able to develop and implement their respective post-integration follow-up actions.

The co-development in partnership with stakeholders at the national, regional, and global levels beyond immunization was key to jointly defining a new concept: integrating COVID-19 vaccination into immunization programmes and PHC. The definition was holistic and captured the needed perspectives and principles of sustainable integration. As countries continue to integrate COVID-19 vaccines, feedback to enable further simplification and improvement of the definition is welcome. Effectively engaging other health programmes and ministries beyond immunization, to be included in the integration process, continues to be difficult and remains a work in progress. Mapping the necessary short-term (6-12 months) investments using the health system building blocks and aligning this with the timeframes of funding opportunities enabled the prioritization of COVID-19 vaccination integration in country plans and proposals. The experience gained in the development of the integration guidance further demonstrated the resilience and commitment of global health partnerships, which remain focused on addressing the overall public health needs of prevention and control of the COVID-19 pandemic in the face of rapidly changing circumstances. Thus, waiting for a ‘suitable’ time was not – and will never be – feasible.

While the guidance was developed as a ‘living document’ in 2022, it remains relevant for the present and the future [

7,

24,

25]. The COVID-19 vaccination effort did not end with the standing down of the Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) in May 2023. SARS-CoV-2 is still circulating with new variants emerging, and certain groups continue to be at greater risk of severe disease and mortality. WHO SAGE recommended a focus in 2023 on increasing COVID-19 vaccination coverage (primary series and booster doses) for older adults, adults with comorbidities and severe obesity, people with immunocompromising conditions, pregnant people, and frontline health workers [

26]. In alignment with this, WHO post-PHEIC recommendations called for the enhancement of elements of future preparedness, and the integration of COVID-19 vaccination into life course vaccination (mainly targeting adult populations), which includes the sustainability and resilience of service delivery platforms [

27]. The most recent SAGE recommendation is for a shift towards a simplified single-dose regime for primary vaccination for most COVID-19 vaccines. In consideration of these recommendations and the need for long-term planning of COVID-19 vaccination, the global guidance has been used to develop regional strategies. The WHO Regional Office for Europe recently published a shorter version of the global guidance on developing national COVID-19 vaccination policy and integrating COVID-19 vaccination into national immunization programmes and broader healthcare delivery mechanisms [

28], and the WHO African Region leveraged the approach proposed in the global guidance to inform its COVID-19 Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan for 2023-2025 [

29]. The integration guidance also speaks to the need to monitor and assess the progress on integration, since the lessons learned will guide countries in optimizing and integrating COVID-19 vaccination; preparing for the introduction of future vaccines that target adults; preparing for future pandemics; and developing approaches and guidance for the integration of other vertical programme services [

30]. While countries may have previously faced challenges with funding to drive integration because much of the earlier pandemic response funding was ringfenced, the approval in June 2023 by the Gavi Board to offer support for 92 LMICs of the COVID-19 vaccination programme for 2024 and 2025, and the extension of the Gavi CDS funding, could offer opportunities for improved integration[

22].

Integration is not easy and requires strategic planning, time, and resources. SARS-CoV-2 is still evolving, and new vaccines are being developed to continue to provide high levels of protection against severe disease and death. The unclear long-term COVID-19 vaccine policy recommendations, the decrease in risk perception of COVID-19 by the population (including high priority-use groups), and the lack of secured long-term funding remain existential threats to this agenda. COVID-19 vaccines continue to be the most effective tool to prevent serious illness, hospitalization, and death from COVID-19, and leveraging the COVID-19 legacy affords a unique opportunity to contribute to resilient programmes, Immunization Agenda 2030 goals, and the PHC agenda.

5. Conclusions

The rapid process for developing the WHO-UNICEF global guidance in collaboration with many stakeholders beyond immunization, along with the broad dissemination of information to countries and alignment with funding opportunities allowed for its early use by countries. The COVID-19 vaccine has become an important element of health programmes globally, and it is important to continue monitoring and learning how countries move towards mainstreaming COVID-19 vaccines as an element of PHC and other relevant health services through the life course and as an element for better pandemic preparedness and response.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.D., A.V., S.R., V.B., P.M.,A.L; methodology, I.D., A.V., S.R., P.M., V.B., A.L.; data curation, .N., I.M., S.M., I.M.A., A.V.; data analysis, F.N., I.M., S.M., I.M.A, I.D., A.V; original draft preparation —P.M, A.V., I.D., S.M., S.R., F.N., I.M., V.B., I.M.A., A.L.; writing—review and editing by all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No specific funding was received for this study, but Article processing charges are supported by agency funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this paper have been cited and are publicly available.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge our partners, and the countries who shared and presented the results of their COVID-19 vaccination integration readiness assessments. To Jessica Hofmans, Mona Cailler and Geena Zimbler for their analysis of the CDS proposals of Gavi-eligible countries. And to the copy editor and all those that contributed with comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO), WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. n.d.

- Haldane, V.; et al. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from 28 countries. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 964–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO), COVID-19 Vaccination Information Hub.. 2021.

- World Health Organization (WHO), Global COVID-19 Vaccination Strategy in a Changing World: July 2022 update. 2022.

- Causey, K.; et al. Estimating global and regional disruptions to routine childhood vaccine coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: a modelling study. Lancet 2021, 398, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandir, S.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic response on uptake of routine immunizations in Sindh, Pakistan: An analysis of provincial electronic immunization registry data. VACCINE 2020, 38, 7146–7155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadari, I.; et al. Analysis of the impact of COVID-19 pandemic and response on routine childhood vaccination coverage and equity in Northern Nigeria: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e076154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ED, C.; et al. Impact of the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Coverage of Reproductive, Maternal, and Newborn Health Interventions in Ethiopia: A Natural Experiment. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 778413. [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor, A.; et al. Impact of covid-19 pandemic on routine immunization of children. Rawal Med. J. 2022, 47, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ota, M.O.C.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on routine immunization. Ann. Med. 2021, 53, 2286–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO), Strategic preparedness, readiness and response plan to end the global COVID-19 emergency in 2022. 2022, World Health Organization.

- WHO-UNICEF, Considerations for integrating COVID-19 vaccination into immunization programmes and primary health care for 2022 and beyond. 2022.

- World Health Organization, Working together: an integration resource guide for immunization services throughout the life course. 2018.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Implementing the Immunization Agenda 2030. 2021 [cited 2021 January 7]. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/implementing-the-immunization-agenda-2030.

- Moberg, J.; et al. The GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework for health system and public health decisions. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehfuess, E.A. The WHO-INTEGRATE evidence to decision framework version 1.0: integrating WHO norms and values and a complexity perspective. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4 (Suppl. 1), e000844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadelmaier, J.; et al. Using GRADE Evidence to Decision frameworks to support the process of health policy-making: an example application regarding taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages. Eur. J. Public Health 2022, 32 (Suppl. 4), iv92–iv100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbuanu, I.U.; et al. Can vaccination coverage be improved by reducing missed opportunities for vaccination? Findings from assessments in Chad and Malawi using the new WHO methodology. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PATH, Integrating the supply chains of vaccines and other health commodities. 2013.

- WHO-UNICEF, COVID-19 vaccine integration checklist. 2023, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), World Health Organization (WHO).

- UNICEF, AMC30 CDS Country Results Tracker [Unpublished data]. 2023.

- Gavi the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi), Review of Board Decisions: Board Meeting June 26-27, 2023. 2023: Geneva, Switzerland.

- Munn, Z.; et al. Developing guidelines before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020, American College of Physicians. p. 1012-1014.

- Nabia, S.; et al. , Experiences, Enablers, and Challenges in Service Delivery and Integration of COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Systematic Review. Vaccines 2023, 11, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadari, I.K., Perspective Chapter: The Pivotal Role of Vaccines and Interventional Equity and Appropriateness, in Global Health Security - Contemporary Considerations and Developments, M. Dr. Allincia, P.S. Dr. Stanislaw, and I. Prof. Ricardo, Editors. 2023, IntechOpen: Rijeka. p. Ch. 14.

- World Health Organization (WHO), WHO SAGE roadmap on uses of COVID-19 vaccines in the context of OMICRON and substantial population immunity: an approach to optimize the global impact of COVID-19 vaccines at a time when Omicron and its sub-lineages are the dominant circulating variants of concern, based on public health goals, evolving epidemiology, and increasing population-level immunity, first issued 20 October 2020, updated: 13 November 2020, updated: 16 July 2021, update: 21 January 2022, latest update: 30 March 2023. 2023, World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (WHO), Statement on the fifteenth meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 pandemic. 2023, World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (WHO), Guidance on developing national COVID-19 vaccination policy and integrating COVID-19 vaccination into national immunization programmes and broader health care delivery mechanisms in the WHO European Region: August 2023. 2023, World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe.

- World Health Organization (WHO), COVID-19 response in Africa bulletin: situation and response in the WHO AFRO Region. 2023.

- Tate, J.; et al. The life-course approach to vaccination: Harnessing the benefits of vaccination throughout life. Vaccine 2019, 37, 6581–6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 |

Based on estimates of the COVID-19 Vaccine Delivery Introduction and Deployment Costing Tool (CVIC tool) |

| 2 |

Advanced Market Commitment (AMC) Countries could apply to COVAX CDS if they were eligible for Gavi support (that is, if their most recent gross national income [GNI] per capita was less than or equal to US$ 1,730). AMC countries (non-Gavi eligible) with a GNI above USD1,730 and below USD4,000 (and an additional set of IDA-eligible countries) could apply for and receive CDS through the UNICEF-managed CDS envelope – these are referred to as the ‘AMC30’ countries. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).