1. Introduction

Knowledge representation refers to the process of crafting a structured framework that represents information related to a particular domain of interest. The purpose of knowledge representation is to facilitate reasoning and decision-making concerning the domain of interest [3]. To represent scientific knowledge through a structured framework, knowledge graph is widely used. A knowledge graph can be described as a systematic representation of facts through entities, relationships, and semantic framework. A significant number of knowledge bases have been developed so far such as Freebase, WordNet, ConceptNet, DBpedia, YAGO, NELL etc. [3]. These systems have been extensively used for question-answering systems, search engines, and recommendation systems etc. Structured information can be useful outside of knowledge graph as well. OMRKBC [2] is a machine-readable knowledge base, designed to enable efficient data access and utilization. The authors of OMRKBC [2] have structured it using the fundamental concept of knowledge graph triples, making it accessible via a variety of systems. In practical terms, this knowledge base allows users to extract valuable information efficiently through diverse applications and interfaces. Furthermore, the authors have introduced an additional framework known as NLIKR [4], which not only extracts definitions of concepts from their dictionary but also comprehends the contextual meaning of these definitions. This further enhances the versatility and utility of the knowledge base in understanding and utilizing the information it contains.

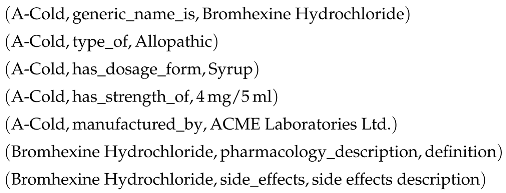

In this paper, we propose a domain specific dictionary between human and machine languages. The inspiration of this dictionary stemmed from an extensive survey of knowledge graphs. There is a unique opportunity to enhance the way medicine information is organised, accessed, and understood. The ultimate goal of this dictionary is to improve the quality of healthcare services. This knowledge graph-driven Medicine Dictionary will serve as a cornerstone in the realm of medical information systems. Its foundation lies in a well-structured ontology that utilizes knowledge graph triples to represent essential information about medications, their classifications, strength, side effects, and various attributes. These triples, such as "A-Cold, has dosage form, Syrup", "A-Cold, type of, allopathic," etc. form the backbone of our ontology, enabling us to organize and present information in a format that is both machine-readable and human-understandable. This paper will explore the rationale, methodology, and potential benefits of constructing such a medicine dictionary.

The primary aim of this paper is to introduce a novel framework for constructing a comprehensive medicine dictionary using structured triples. While existing resources like The Danish Fetal Medicine database [6], YaTCM [7], MEDI database [9], and knowledge graphs such as SMR [8] and SnoMed kg [10] have contributed to the field, they typically present data in relational table formats or contain triples that are not exclusively focused on medicine-related information. Furthermore, these knowledge graphs primarily serve predictive or safety purposes within the medical sector.

What sets our proposed dictionary apart is its unique capability to represent medicine attributes through entities and relations, thereby enabling advanced reasoning abilities. Users of this dictionary will be empowered to effortlessly extract crucial medicine-related details, including generic names, types, strengths, manufacturers, pharmacological descriptions, side effects, and, significantly, a wide range of alternative medicine brands for each primary medicine brand.

Knowledge reasoning ability is crucial for representing knowledge a in structured format. Reasoning can be described as the process of analyzing, consolidating, and deriving new information on various aspects based on known facts and inference rules (relationships). It involves accumulating facts, identifying relationships between entities, and developing advanced understandings. Reasoning relies on prior knowledge and experience. Mining, organising, and effectively managing knowledge from large-scale data are conducted through reasoning capabilities [11].

The rest of the paper will be organised as follows.

Section 2 will briefly discuss the previous research on knowledge bases and findings from the literature survey on knowledge representation learning, acquisition, and applications. In the next section, we will delve into the methodology employed to construct medicine dictionary. Here, we will briefly layout our approach, detailing how we harness structured triples to construct our comprehensive medicine dictionary. The methodology section will unveil the techniques and tools utilized in this project. After that, we will explore the practical application of our medicine dictionary. Real-world applications such as information extraction mechanism and question answering techniques will be discussed. Furthermore, we will showcase our experimental results and compare our work with existing mechanisms. Lastly, this paper will conclude with future research directions and the broader implications of our work.

2. Related Works

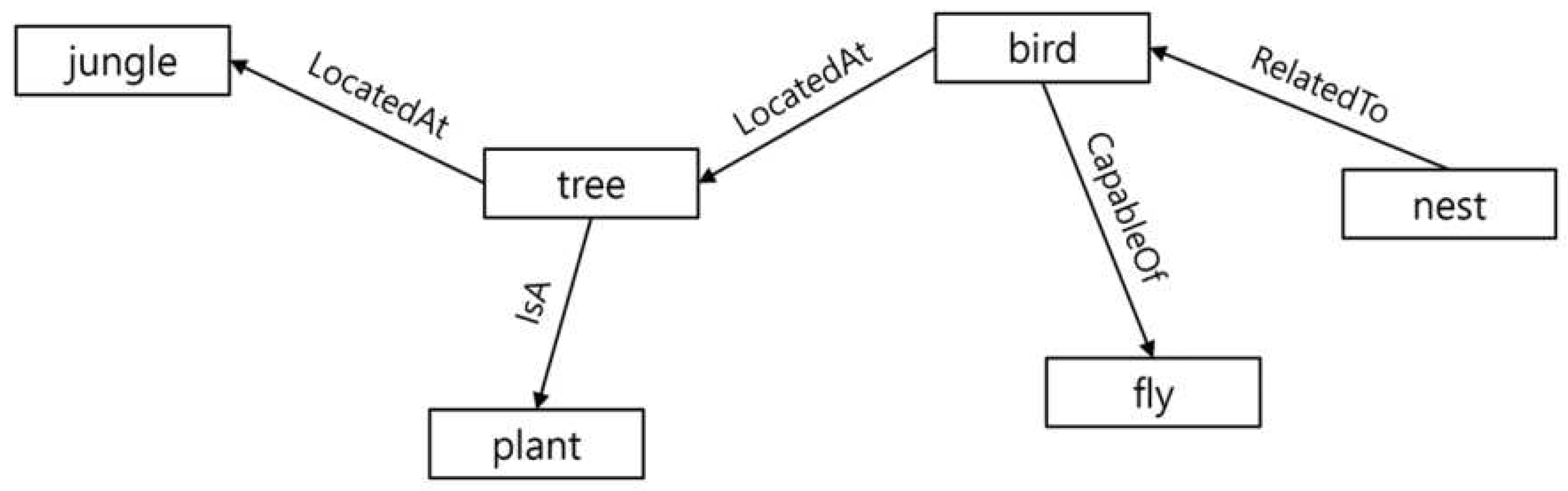

The domain of Artificial Intelligence has an extensive and well established history of knowledge representation and reasoning, often facilitated by knowledge graphs. These graphs are primarily used to predict missing links within a vast network of information. An example illustrating knowledge graph is presented below:

A knowledge graph is a directed graph. It contains a set of entities (nodes) linked by directed and labeled edges. Each edge represents a relation. The two entities linked by a relation represent a relationship. The entity pointed by the relation is the head of the relationship while the other entity is called the tail. An entity can be a head as well as a tail in a knowledge graph. For instance, in

Figure 1, entity “tree" is the head in the relationship “tree isA plant". Meanwhile it is a tail in the relation “bird locatedAt tree".

The concept of semantic net (Richens, 1956) can be identified as the origins of diagram based knowledge interpretation [3]. Similarly, General problem solver (1959) can be marked as the origins of symbolic reasoning [3]. As knowledge representation progressed, various methods emerged, including framework driven language, reasoning-driven system, and blended manifestation systems. MYCIN [3], the renowned knowledge reasoning system in medical diagnosis relied on rule-based systems. The semantic Web’s essential standards, such as Web Ontology Language (OWL) and RDF, were inspired by knowledge representation and reasoning systems [3]. Apart from these, various systems and resources, including WordNet, DBpedia, ConceptNet, YAGO, and Freebase, have been developed to capture and represent knowledge effectively and efficiently.

WordNet [5] can be described as a lexical database of English words defined through synonyms. In the database, words are bundled as synsets. One synset can be defined as one unique concept. Concepts are linked through lexical relations; thus allowing machines to understand meaning of words. However, the authors of NLIKR [4] argue that synsets are not enough to describe a word. Their argument was based on the fact that a word representing existence may reveal its characteristics in various ways and WordNet is not capable of expressing them [4]. ConceptNet [12] was constructed using words and phrases connected by relations to model general human knowledge. ConceptNet has the ability to supply a comprehensive collection of general knowledge required by computer applications for the analysis of text based on natural language. However, ConceptNet has a significant drawback in that its relationships are inflexible and limited. Users cannot define custom relationships for their choice of words or phrases. DBPedia [13] is a collection of structured information on various domains that has been extracted from wikipedia. But, the knowledge is limited to named entities or concepts.

In recent years, knowledge representation learning has become essential for various applications, such as knowledge graph completion and reasoning. Researchers have explored multiple geometric spaces, including Euclidean, complex, and hyperbolic spaces. Notable models, such as RotatE [19], leverage complex space, while ATTH [20] focuses on hyperbolic space for encoding hierarchical relationships. TransModE [23] takes an innovative approach by utilizing modulus space, and DiriE [21] introduces Bayesian inference to tackle uncertainty in knowledge graphs.

RotatE [19], introduced a novel approach by leveraging complex space to encode entities and relations. This model is based on Euler’s identity and treats unitary complex numbers as rotational transformations within the complex plane. RotatE aims to capture relationship structures, including symmetry/anti-symmetry, inversion, and composition. Another approach delves into hyperbolic space, as seen in the ATTH [20] model. This model focuses on encoding hierarchical and logical relations within a knowledge graph. The curvature of the hyperbolic space is a crucial parameter that dictates whether relationships should be represented within a curved, tree-like structure or a flatter Euclidean space. Similarly, MuRP [22] employs hyperbolic geometry to embed hierarchical relationship structures. This model is suitable for encoding hierarchical data with relatively few dimensions, offering scalability benefits. TransModE [23] takes a unique approach by utilizing modulus space, which involves replacing numbers with their remainders after division by a given modulus value. This model is capable of encoding a wide range of relationship structures, including symmetry, anti-symmetry, inversion, and composition. DiriE [21] adopts a Bayesian inference approach to address the uncertainty associated with knowledge graphs. Entities are represented as Dirichlet distributions, and relations as multinomial distributions, allowing the model to quantify and model the uncertainty of large and incomplete knowledge frameworks.

Knowledge graphs require continuous expansion, as they often contain incomplete data. Knowledge Graph Completion (KGC) aims to add new triples from unstructured text, employing tasks like relation path analysis. Relation extraction and entity discovery play vital roles in discovering new knowledge from unstructured text. Path analysis entails examining sequences of relations between entities to infer missing or potential relations. Relation extraction and entity discovery are essential for discovering new knowledge from unstructured text, involving tasks like determining relationships between entities and aligning entities with their types. RECON [16] is a relation extraction model introduced in 2021 that effectively represents knowledge derived from knowledge graphs using a graph neural network (GNN). This model leverages textual and multiple instance-based mechanisms to learn background characteristics of concepts, analyze triple context, and aggregate context. Knowledge Graph Embedding (KGE) has become a popular approach for KGC, with models like TransMS [17] addressing the limitations of earlier translation-based models. TransMS projects entities and relations into different embedding spaces, allowing for more flexible and accurate modeling of complex relations. Type-aware Attention Path Reasoning (TAPR) [18], proposed in 2020, tackles path reasoning in knowledge graphs. It offers greater flexibility in path prediction by considering KG structural facts, recorded facts, and characteristic information. TAPR leverages character-level information to enrich entity and relation representations and employs path-level attention mechanisms to weight paths and calculate relations between entities.

The integration of structured knowledge, especially knowledge graphs, has significant implications for AI systems. Knowledge-aware applications have emerged in various domains, including Language Representation Learning and Recommendation Systems. Models like K-BERT [14] and ALBERT [15] offer solutions to integrate knowledge graphs and enhance AI capabilities. For domain-specific knowledge in LR, K-BERT [14] was introduced in 2020. It addresses the challenges of integrating heterogeneous embedding spaces and handling noise in knowledge graphs. K-BERT extends existing BERT models, allowing them to incorporate domain-specific knowledge from a knowledge graph. ALBERT [15], introduced in 2022, focuses on fact retrieval from knowledge graphs. This model leverages schema graph expansion (SGE) to extract relevant knowledge from a knowledge graph and integrate it into a pre-trained language model. ALBERT consists of five modules, including a text encoder, classifier, knowledge extractor, graph encoder, and schema graph expander.

As we conclude our exploration of knowledge representation learning, knowledge acquisition, and integration, it is clear that an untouched opportunity lies in the horizon — a chance to revolutionize the field of medicine through the creation of a dynamic and comprehensive medicine dictionary. Inspired by the architecture of knowledge graph and various other databases, this opportunity presents an unparalleled potential to transform the way we understand and utilize medical knowledge.

3. The Domain Specific Medicine Dictionary (DSMD) and Its Construction

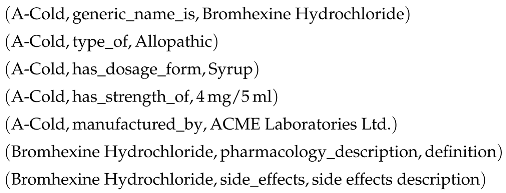

A domain-specific dictionary can be defined as a knowledge base organized in a knowledge graph architecture, comprising entities and relations. Each entity is interconnected with other entities through relationships. A domain-specific dictionary is centered around a particular field of expertise, like medicine, diseases, economics, finance etc. The primary objective is to populate this knowledge base with triples to facilitate information extraction and question-answering. Let’s take an example of a knowledge base or knowledge graph in medicine domain:

This domain-specific dictionary serves as a structured and interconnected repository of knowledge tailored to a specific field which is important in enhancing information retrieval and analysis within that domain.

In this chapter, we present a structured approach to construct human-machine dictionary in medicine domain smoothly and effectively. Open sourced Assorted Medicine Data of Bangladesh [1] will be used to build a prototype dictionary. Before moving on to the prototype design, we will explore the properties of the dictionary.

3.1. Concepts and Relations

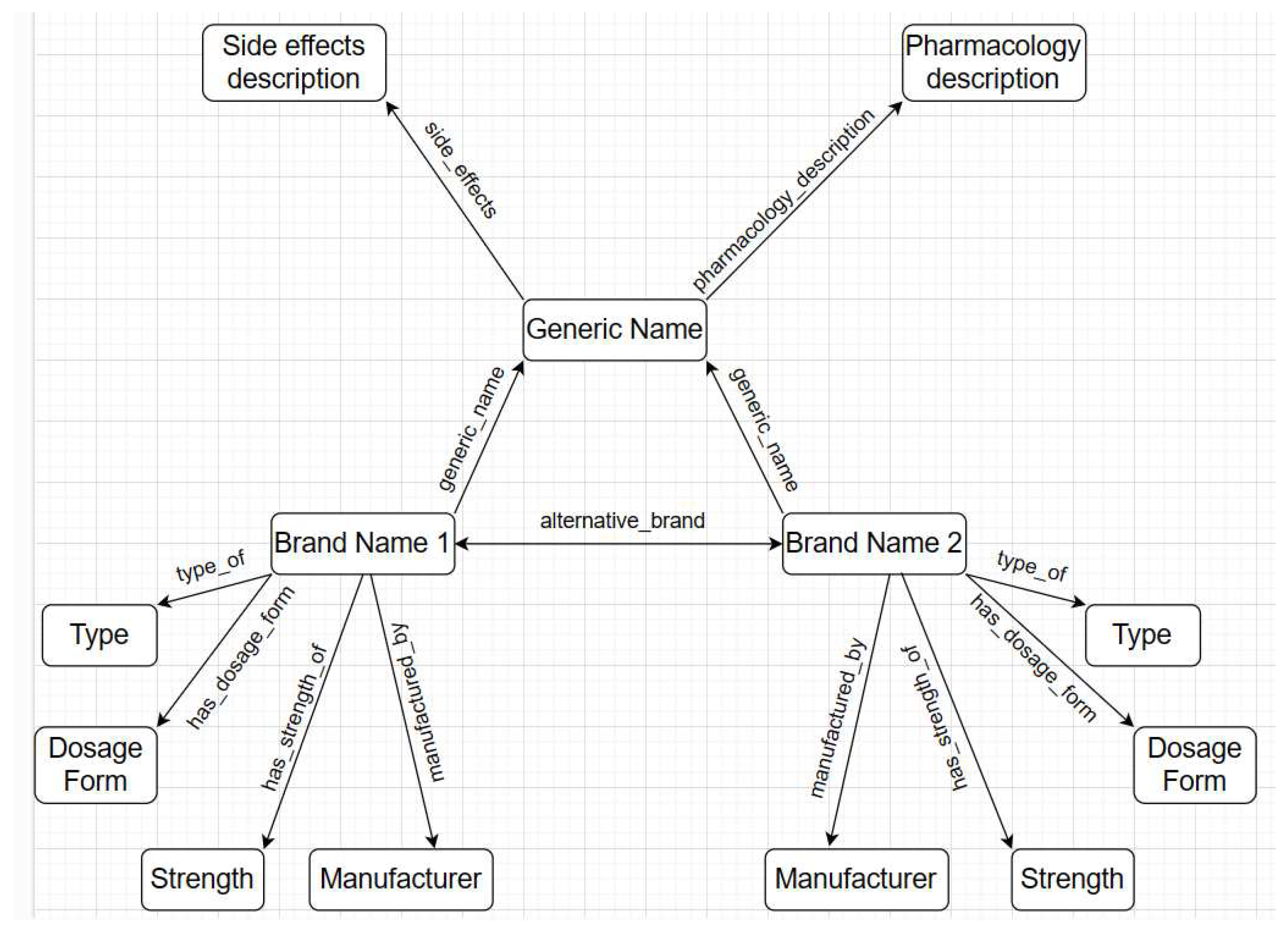

Our knowledge graph will consist of entities and relations. Each entity will be considered as a concept and concepts will be connected through relations. Example of entity - A-Cold, A-Cof, Syrup, Allopathic etc. Entities can be name of medicine brands, generic name, type of medicine such as herbal or allopathic, dosage form of medicine such as tablet or syrup, strength of medicine etc.

On the other hand, relations will express the connection between concepts. For example, If A-Cold and Syrup both are concepts in the dictionary, what is the appropriate connection or link between them? The link between them can be defined as relation. Here the appropriate link between A-Cold and Syrup would be ’dosage form’. Once links are identified we can a form triple like - (A-Cold, has dosage form, Syrup).

While concepts are collected easily from data, discovering relations are the tricky part. Khanam et al. [2] has established certain rules for discovering relations. One such rule is that a verb or common noun or an adjective followed by a preposition can be considered as a relation. For example, type of, strength of, manufactured by etc. We followed this rule to establish a few relation for our dictionary. Some new rules have been discovered as well. Following are few rules that we have discovered during our research:

Rule number one - a verb phrase can be considered as a relation. For example, A-Cold, has dosage form, Syrup. In this triple, ’has dosage form’ is a verb phrase.

Rule number two - a noun or noun phrase can be considered as a relation. For example, ’generic name’, ’side effects’, ’description’ etc.

Since we are constructing a medicine dictionary with limited number of attributes, we decided to keep a limited number of relations in the knowledge graph. The relation types are symmetric, complex, and asymmetric. A symmetric relation is the one in which the positions of head and tail can be swapped. Lets take an example of symmetric relation - (A-Cold, alternative brand, Brohexin). The reverse triple - (Brohexin, alternative brand, A-Cold) is true as well. A complex relation is defined as a more intricate or multi-layered connection between entities. Complex relation - (A-Cold, pharmacology description, description); this is true because of - (Bromhexine Hydrochloride, pharmacology description, description). More explanation can be found on this in the hierarchical structure and inheritance section. Example of asymmetric relation - (A-Cold, type of, allopathic). Architecture of the structured triples can be found in the following diagram:

3.2. The Hierarchical Structure and Inheritance

Following the knowledge graph architecture, a hierarchical structure is maintained in the dictionary. Hierarchy in a knowledge graph refers to the phenomenon that an entity can be a type of another entity, hence attribute inheritance becomes possible. For instance, Cat as an entity is a type of Mammal which is another entity in a knowledge graph. As such Cat can be defined as a descendant of Mammal and inherits attributes such as "warm-blooded" and "produce milk to feed their young" from Mammal. In our knowledge graph, the hierarchy is as follows - each generic medicine has multiple medicine brand manufactured by multiple manufacturer. Each medicine brand has 4 different attributes including type, dosage form, strength, and manufacturer. Generic name, brand name, and attributes form a hierarchy, which is true for the entire database.

Besides, each medicine brand inherits the attributes of generic medicine. Each generic medicine has two definitions as its attributes including pharmacology description and side effects. Lets take an example of complex relation - (Bromhexine Hydrochloride, pharmacology description, description). Since each medicine brand inherits attributes from generic medicine, when the dictionary connects all the triples together it will find medicine brand will have definition. We did not explicitly mention in the database that A-Cold has a description. But, through complex relation each brand should find a definition and side effects description. So that we end up with - (A-Cold, pharmacology description, description).

3.3. Prototype Dictionary

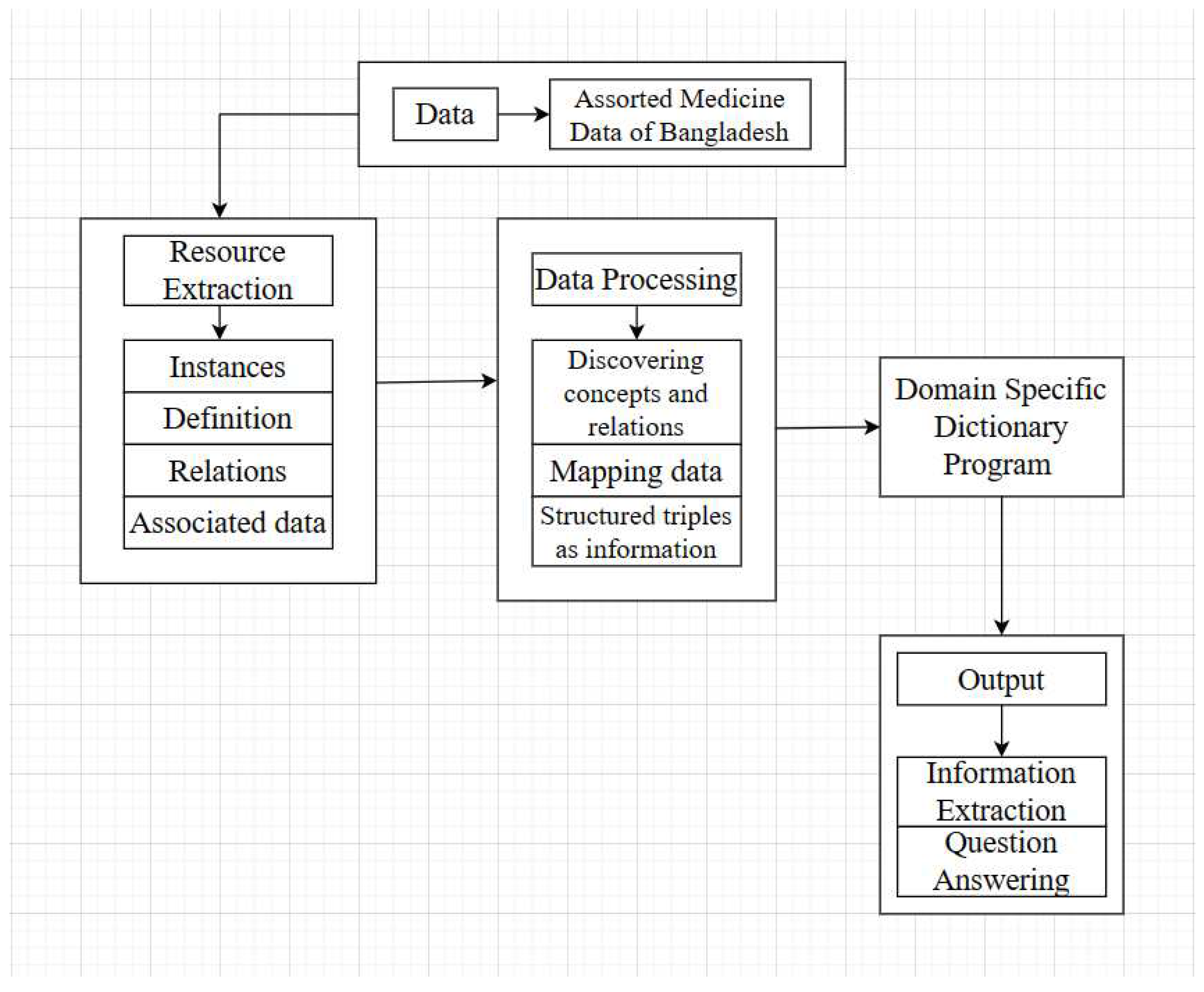

In this section, we will briefly explore the process of building a prototype dictionary including data collection, processing, mapping, structured triple formation, and functional programming design and implementation. The following figure is the Architecture of prototype dictionary:

Figure 3.

Architecture of the prototype dictionary.

Figure 3.

Architecture of the prototype dictionary.

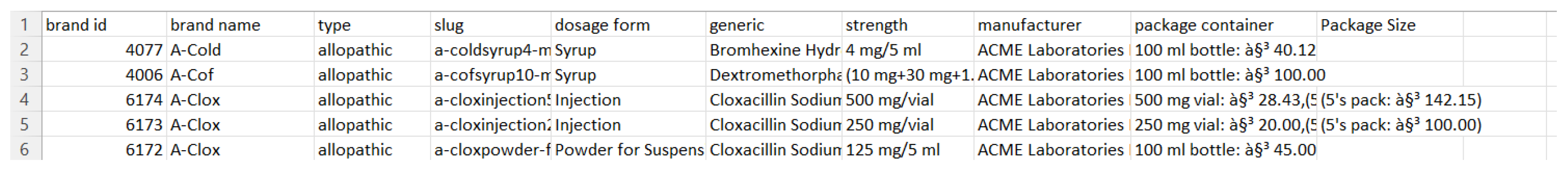

3.4. Brief Description of the Dataset

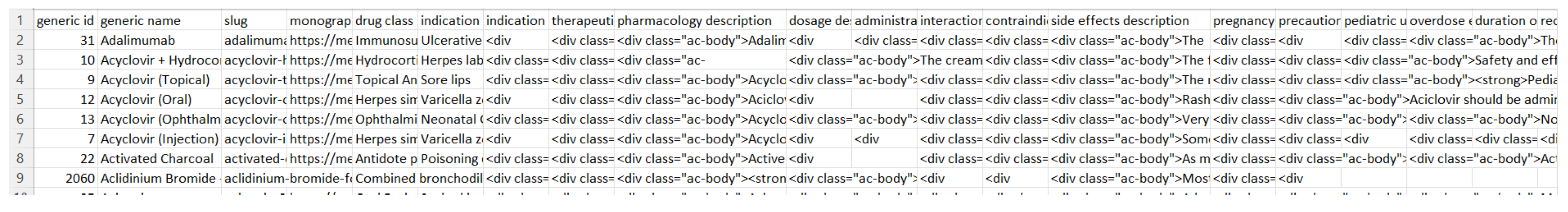

To build our dictionary, we have used an open sourced medicine dataset called Assorted Medicine Dataset of Bangladesh [1]. This dataset consists of medicine brands with its generics, drug classes, indications, dosage forms, manufacturer’s information, descriptions, and side effects etc. The dataset contains more than 20000 different medicine brands. All information is stored in 6 different csv files. For our research purpose, we only used two csv files including medicine.csv and generic.csv. The following figure is a preview of medicine.csv:

Figure 4.

A preview of medicine.csv.

Figure 4.

A preview of medicine.csv.

Medicine.csv consists of many different brands of medicine with its attributes. Attributes include brand id, brand name, type, slug, dosage form, generic, strength, manufacturer, package container, and package size. Some of the information are not useful, while others are very important. We decided to keep the useful information and remove the unnecessary information such as brand id, slug, package container, and package size. Package size can be useful, but there was a lot of missing information in that specific column. Hence, the decision is to remove package size. The following figure is a preview of generic.csv:

Generic.csv consists of many columns such as generic id, generic name, slug, monographic link, drug class, indication, therapeutic class description, pharmacology description, dosage description, side effects description and many more. For our research purpose, we decided to use generic name, pharmacology description, and side effects description column. We simply removed the other information. There are more than 1400 different generic medicine name and its associated information in the dataset. A preview of generic.csv can be found in

Figure 5 above (before removing any data).

3.5. Data Processing

Data processing involved selecting concepts, discovering relations between them, mapping data, and forming structured triples. The collected instances from generic.csv and medicine.csv were used to select concepts for the dictionary. For example:

A-Cold, allopathic, Syrup, Bromhexine Hydrochloride, 4mg/5 ml, ACME Laboratories Ltd.

In the above instance, A-Cold is a medicine brand, allopathic is the type of the brand, Syrup is the dosage form of the brand, Bromhexine Hydrochloride is the generic name of the brand, 4mg/5 ml is the strength of the brand, and ACME Laboratories Ltd. is the manufacturer of the brand. Each attribute is being treated as a concept for the dictionary. We also have pharmacology definition of each generic name and side effects of each generic name. They have also been included in the dictionary. After selecting concepts, we started the task of discovering relations. Relations represent the link between two concepts. Hence, it is considered the most important and challenging task in our dictionary construction.

After discovering concepts and relations, we focus on mapping entities and relations to form structured triples. HTML tags needed to be removed from Pharmacology description and side effects description. Python libraries such as pandas and beautiful soup have been used to complete the process. First of all, we remove the HTML tags using beautiful soup library and load the csv files with pandas dataframe. Then we simply link each concept with another concept through relations using functional programming.

3.6. Dealing With Uncertainties

During data processing, we encountered a range of uncertainties, including missing data, duplicate entries, and data in incorrect formats, among others. Uncertainty within the dictionary can be detrimental as it undermines data accuracy and integrity, leading to inaccurate information. In our commitment to enhancing the quality and reliability of our dictionary, we made the deliberate decision to systematically address and eliminate these uncertainties. This meticulous effort ensures that our dictionary offers users accurate and trustworthy information, enhancing its utility for both healthcare professionals and AI applications.

4. Experiments

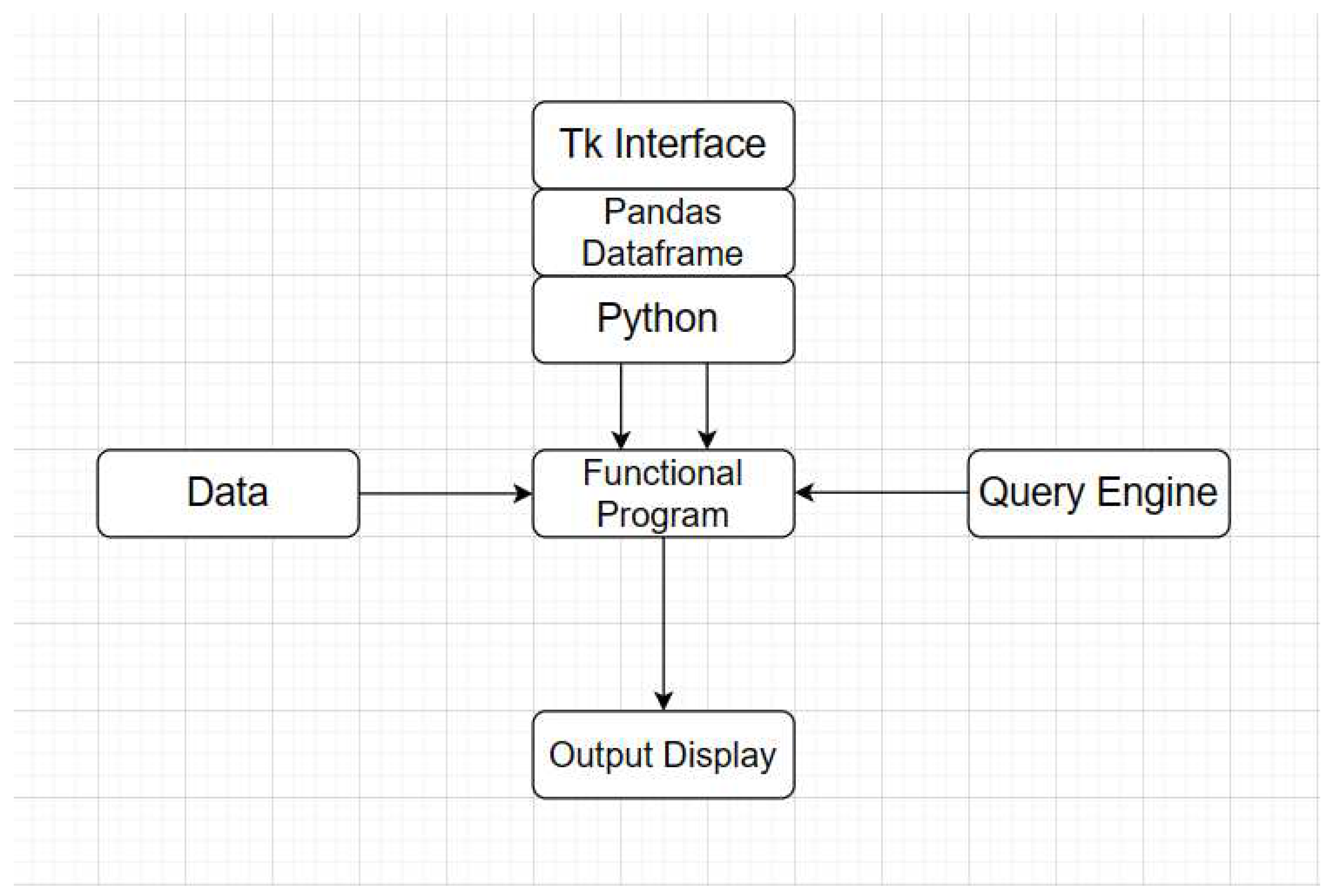

A program has been designed to implement a prototype dictionary. We have used python programming language along with rich libraries such as pandas and tk interface. The prototype dictionary has a simple interface, a query engine, and an output area. It can be used to extract medicine related information and question answering. The program has been made an open ware and placed on GitHub (

https://github.com/Saif0013/DSMD) for public access. Below is the structure of our dictionary program:

Figure 6.

Functional Program Architecture.

Figure 6.

Functional Program Architecture.

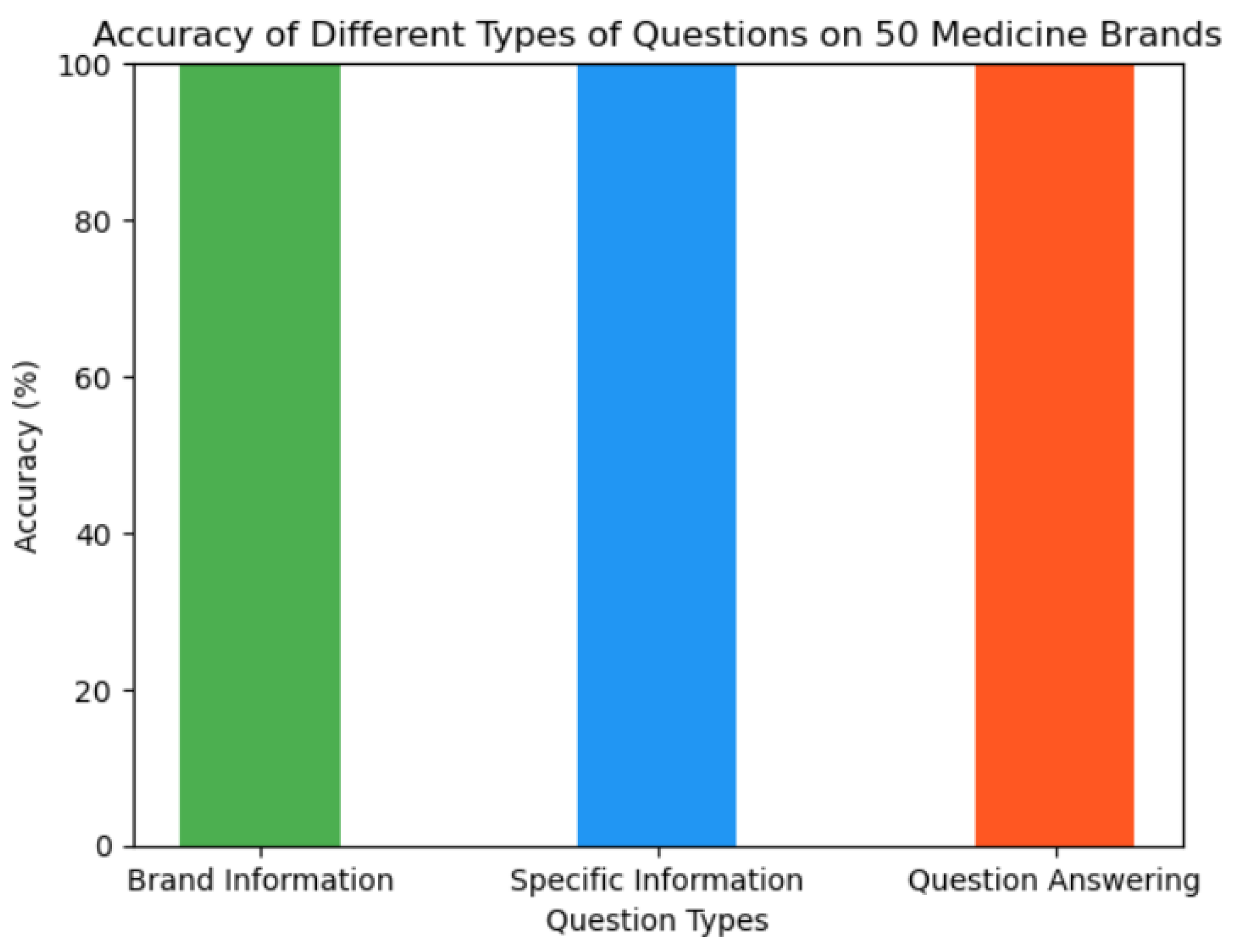

There are more than twenty thousand medicine brands and its associated information available in the dictionary. We selected fifty different medicine brands as part of our experiment. Experiment was conducted on different types of questions such as brand information extraction, specific information extraction about a brand, and question answering with a yes or no. Please navigate to the application section to find out how a question can be asked and how information can be extracted. The overall accuracy of the experiment is 100%. Overall accuracy was calculated based on the following formula:

Figure 7.

Accuracy of experiments.

Figure 7.

Accuracy of experiments.

4.1. Comparison with other works

Our DSMD is truly unique, setting it apart from any other database. Our database boasts an impressive repository of over 348,000 triples, encompassing information on more than 20,000 medicine brands and 1,500 plus details on generic medicines. In contrast to the databases that served as our inspiration, which span a wide range of domains, our dictionary distinguishes itself by its focused approach. When compared to well-known databases like DBpedia, ConceptNet, WordNet, and NLIKR, our dictionary notably contains a leaner volume of data. This not only streamlines information retrieval but also results in faster access when compared to these larger databases. Despite the differences in the nature of these databases, we’ve made deliberate efforts to emphasize the unique characteristics of our DSMD, which are outlined in

Table 1.

5. Applications

DSMD has diverse applications across multiple sectors, benefiting healthcare professionals, medical researchers, pharmacies, healthcare educators, healthcare writers, journalists, regulatory authorities, and pharmaceutical experts. It offers a wealth of information about medicines and drugs, including generic names, dosage forms, medicine types, strengths, side effects, pharmacological descriptions, manufacturers, and alternative brands. Notably, our dictionary excels in providing multiple alternative brands for the same medicine, a highly valuable feature for pharmacists, doctors, medicine students, and researchers. Additionally, DSMD enables users to compare two medicines by calculating their distance and similarity. BERT models like K-BERT [14] and ALBERT [15] can seamlessly integrate knowledge graph databases as an external source of information. Given the adherence of our dictionary to the knowledge graph structure, it serves as a valuable source of information for AI language models. In the following subsections, we will illustrate example use cases, including retrieving information about medicine brands, comparing different medicines, and conducting word-based queries.

5.1. Medicine Comparison

As a dictionary, DSMD allows the distance and similar of two medicines to be estimated based on their percentage of common ancestor (PCA), percentage of common association (PCAS) and percentage of binding association (PBAS) [].

Given two entities e1 and e2, the distance between the two is calculated as [4]

where

,

, and

are three weights. The similarity of

and

can be estimated as

where

and

are two coefficients satisfying

and

and

+

= 1.

The capability to estimate the distance and similarity is extremely important. It enables us to systematically compare the effects and side effects of two drugs, or even explore their interaction.

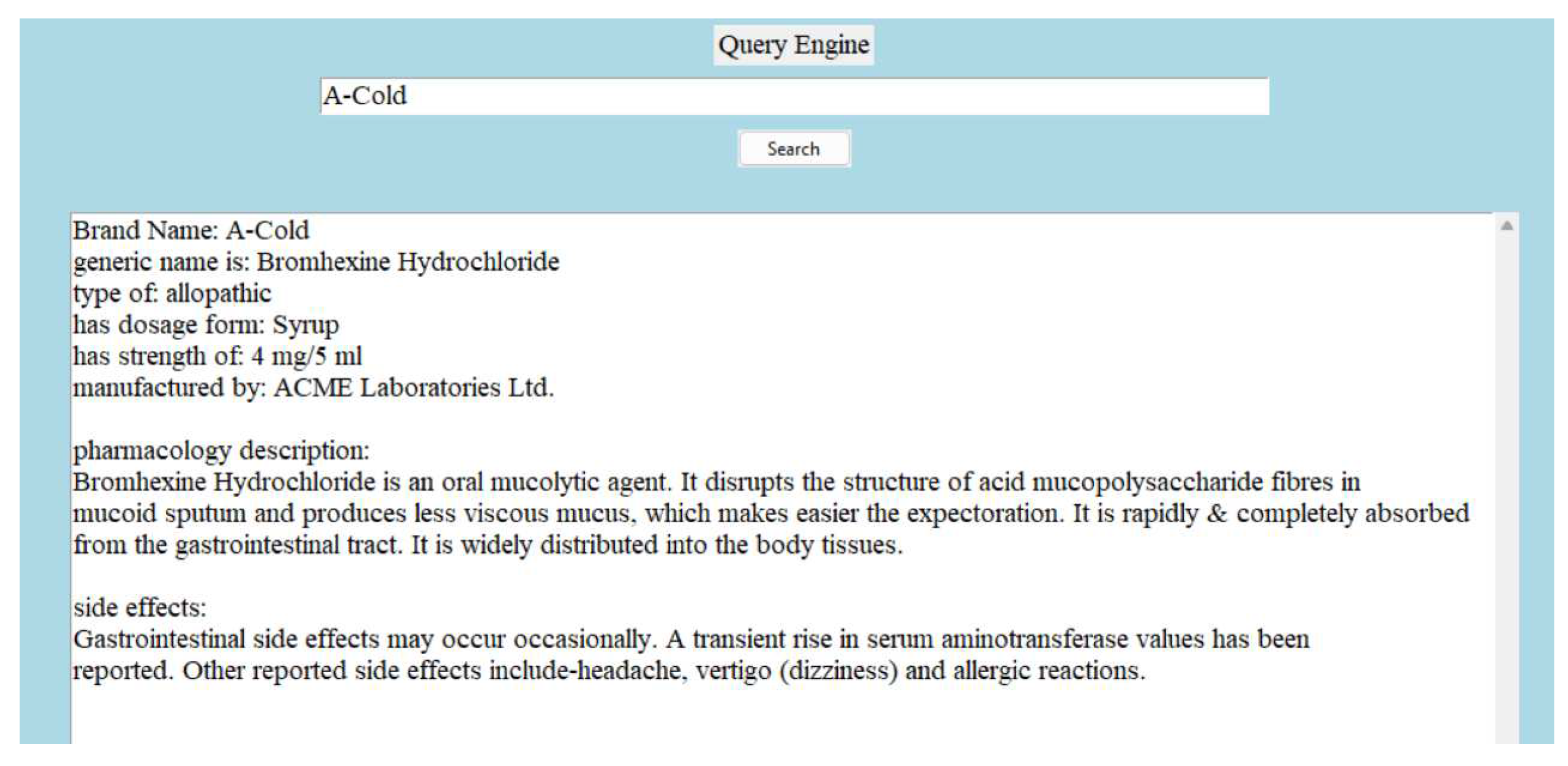

5.2. Brand Information Extraction

The following

Figure 8 is an example of how the dictionary presents each medicine brands information through relationship:

Figure 8.

Brand information extraction.

Figure 8.

Brand information extraction.

Note: In

Figure 6, A-Cold is the medicine brand. The extracted information for example, ’Bromhexine Hydrochloride’ is represented through relation ’generic name is’ and ’allopathic’ is represented through relation ’type of’.

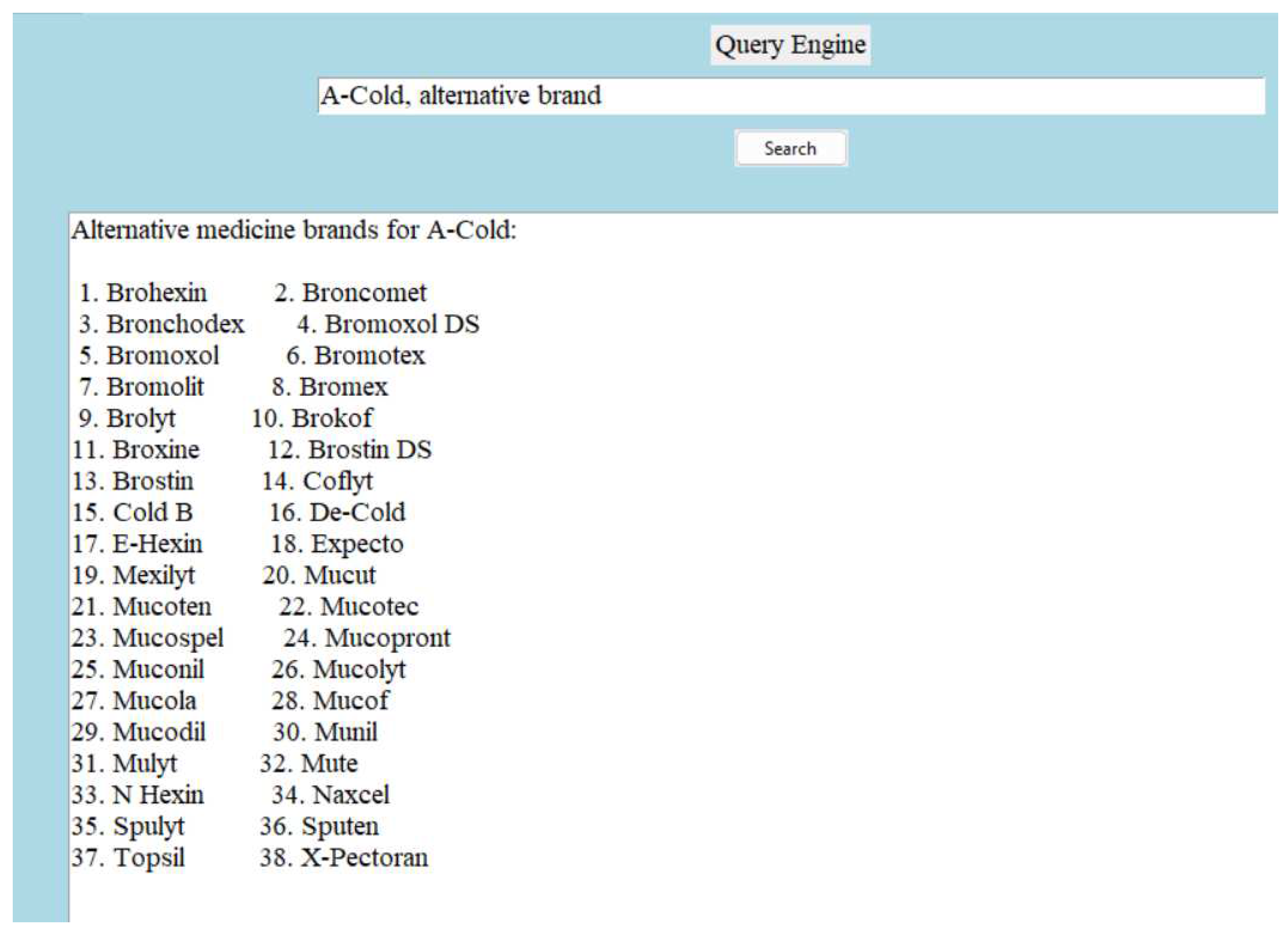

5.3. Alternative Medicine Information Extraction

The following figure is an example of how the dictionary provide alternative medicine brand for a given medicine brand:

Note: In

Figure 9, we can see 38 different alternative medicine brand for ’A-Cold’.

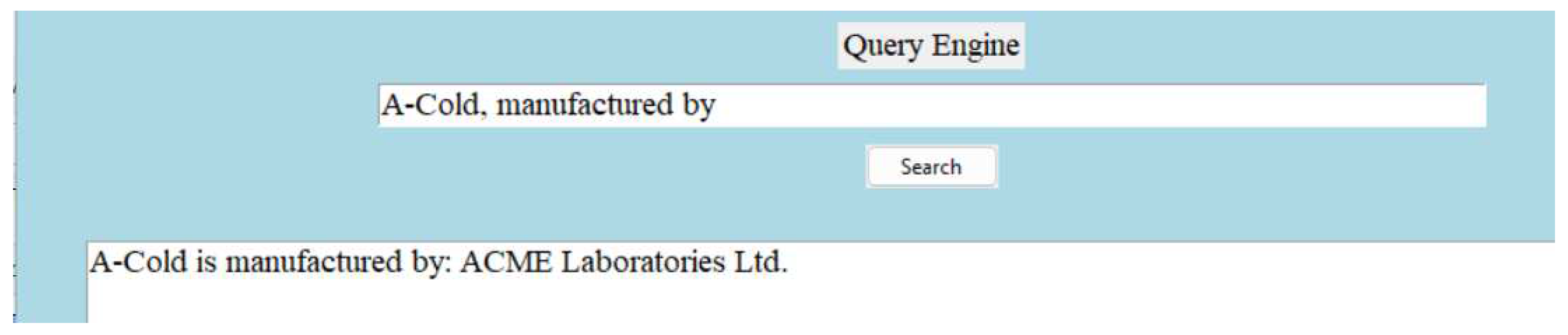

5.4. Question Answering

Our dictionary is also capable of answering specific questions about a medicine brand. The following figure is an example of answering specific question:

Figure 10.

Specific information extraction.

Figure 10.

Specific information extraction.

Note:

Figure 8 demonstrates the ability of answering specific questions regarding a medicine brand.

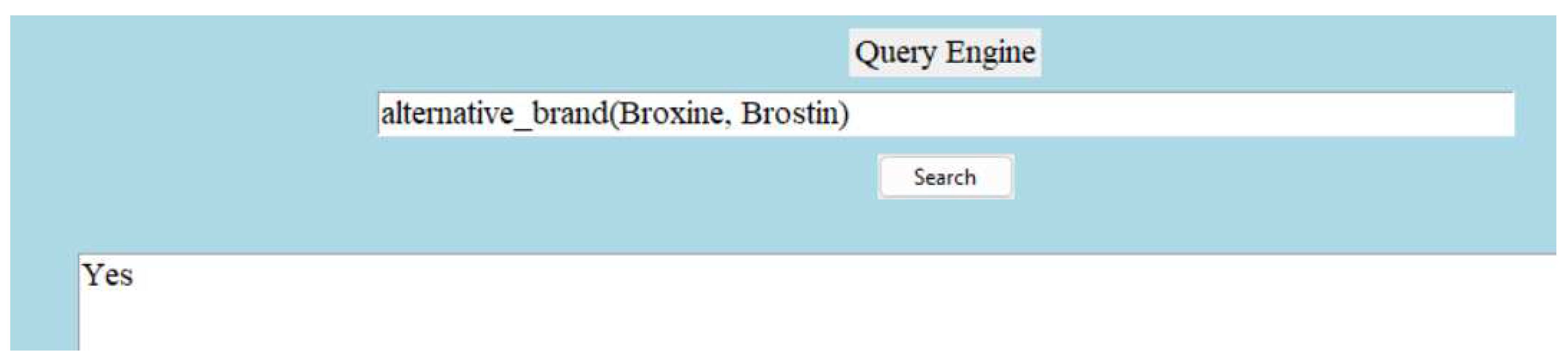

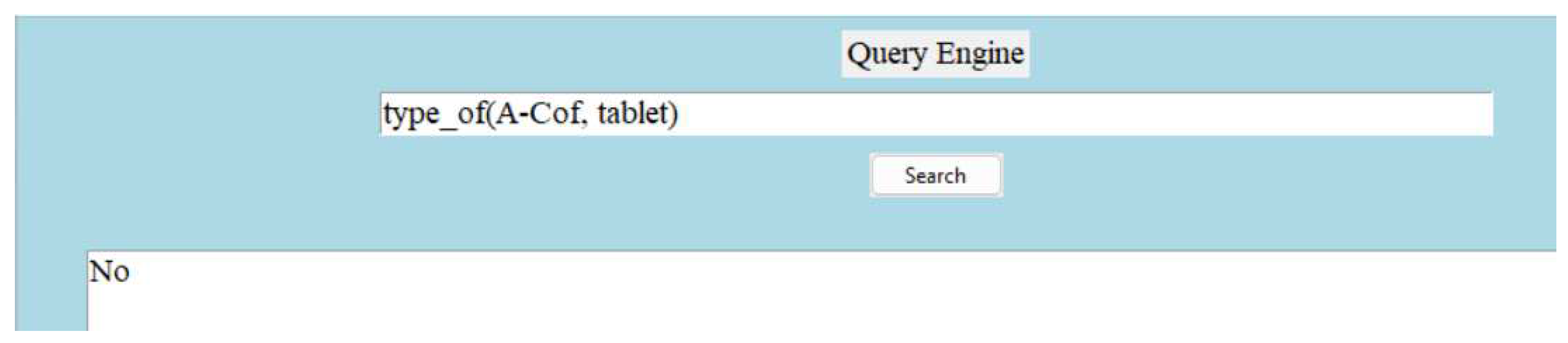

Along with the above information extraction capability, the dictionary also offers the ability of answering questions with a yes or no. For example:

Figure 11.

Question Answering.

Figure 11.

Question Answering.

Note:

Figure 9 demonstrates the ability of answering question with ’Yes’, if the provided information is true.

Another example:

Figure 12.

Question Answering.

Figure 12.

Question Answering.

Note:

Figure 10 demonstrates the ability of answering question with ’No’, if the provided information is false.

5.5. A Brief Overview of Information Extraction and Question Answering

The domain specific medicine dictionary can be used by both human users and machines such as language models including BERT models, ChatGpt etc. By accessing the dictionary a machine or a user can extract the following information:

Yes or No Answers

generic_name_is(A-Cold, Bromhexine Hydrochloride)

type_of(A-Cold, allopathic)

has_dosage_form(A-Cold, Syrup)

has_strength_of(A-Cold, 4 mg/5 ml)

manufactured_by(A-Cold, ACME Laboratories Ltd.)

6. Conclusions

We have introduced a comprehensive framework for creating a domain-specific medicine dictionary, designed to serve both human users and AI applications. In our dictionary, we represent each entity as a concept and establish connections between concepts through meaningful relations. This dictionary excels in its ability to extract essential information related to medicine brands, offer specific insights into individual medicine brands, and respond to inquiries effectively.

A standout feature of our dictionary is its capacity to provide multiple alternative brand options for a single medicine brand, enhancing its practicality and versatility. We anticipate that our dictionary will find valuable application across a diverse spectrum of healthcare fields, including general practice, medical research, pharmacies, healthcare education, and regulatory authorities. Furthermore, the dictionary serves as a rich source of information for various AI applications.

A further research direction has been identified to incorporate more comprehensive details for each medicine brand, such as additional attributes related to manufacturers and generic medicines. These additions may encompass data on drug class, drug indications, and the specific diseases for which the drugs are prescribed. Our original focus was on identifying alternative medicine options for a given brand and providing essential attributes related to medicine brands, such as medicine type, strength, dosage form, and manufacturer. With this framework, a domain specific dictionary can be constructed in the same or any other domain of choice.

Author Contributions

Md Saiful Islam conceptualized and implemented the proposed framework for the Domain-Specific Medicine Dictionary (DSMD), conducted experiments, and performed data analysis. Dr. Fei Liu formulated the framework for medicine comparison, provided guidance throughout the research, and supervised the project. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The prototype of the Domain-Specific Medicine Dictionary (DSMD), along with the associated data and experimental details, has been made publicly accessible. To access the DSMD prototype and related materials, please visit the following link:

https://github.com/Saif0013/DSMD

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DSMD |

Domain Specific Medicine Dictionary |

| KG |

Knowledge Graph |

| KRL |

Knowledge Representation Learning |

| KGE |

Knowledge Graph Embedding |

References

- Assorted Medicine Dataset of Bangladesh. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ahmedshahriarsakib/assorted-medicine-of-bangladesh. Ahmed Shahriar Sakib, 2020. (Accessed on: 20-07-2023).

- S.A. Khanam, F. Liu, P.Y. Chen. Comprehensive structured knowledge base system construction with natural language presentation, Hum. Cent. Comput. Inf. Sci. 9 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Shaoxiong Ji, Shirui Pan, Erik Cambria, Pekka Marttinen, and Philip S. Yu. A Survey on Knowledge Graphs: Representation, Acquisition, and Applications. IEEE, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Fei Liu, Shirin Akther Khanam, Yi-Ping Phoebe Chen. A Human-Machine Language Dictionary. https://www.atlantis-press.com/journals/ijcis. [CrossRef]

- G. Miller, R. Beckwith, C. Fellbaum, D. Gross, K. Miller, WordNet: an on-line lexical database, Int. J. Lexicogr. 3 (2000), 235–244. [CrossRef]

- Charlotte Kvist Ekelund, Tine Iskov Kopp, Ann Tabor, Olav Bjørn Petersen (2016) The Danish Fetal Medicine database, Clinical Epidemiology, 8:, 479-483. [CrossRef]

- Baiqing Li, Chunfeng Ma, Xiaoyong Zhao, Zhigang Hu, Tengfei Du, Xuanming Xu, Zhonghua Wang, Jianping Lin. YaTCM: Yet another Traditional Chinese Medicine Database for Drug Discovery. [CrossRef]

- Fan Gong a, Meng Wang b,c, Haofen Wang d, Sen Wang e, Mengyue Liu f. SMR: Medical Knowledge Graph Embedding for Safe Medicine Recommendation. 2021.

- W.-Q. Wei, R.M. Cronin, H. Xu, T.A. Lasko, L. Bastarache, J.C. Denny Development and evaluation of an ensemble resource linking medications to their indications. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc., 20 (5) (2013), pp. 954-961.

- David Chang, Ivana Balažević, Carl Allen, Daniel Chawla, Cynthia Brandt, and Richard Andrew Taylor. Benchmark and Best Practices for Biomedical Knowledge Graph Embeddings. 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, S. Jia, and Y. Xiang, “A review: Knowledge reasoning over knowledge graph,” Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 141, Mar. 2020, Art. no. 112948. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu, P. Singh, ConceptNet - a practical commonsense reasoning tool kit, BT Technol. J. 22 (2004), 211–226.

- Lehmann J, Isele R, Jakob M, Jentzsch A, Kontokostas D, Mendes PN, Hellmann S, Morsey M, van Kleef P, Auer S, Bizer C (2015) DBpedia—a large-scale, multilingual knowledge base extracted from Wikipedia. Sem Web J 6(2):167–195. [CrossRef]

- Weijie Liu, Peng Zhou, Zhe Zhao, Zhiruo Wang, Qi Ju, Haotang Deng, Ping Wang. K-BERT: Enabling Language Representation with Knowledge Graph. AAAI, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Byeongmin Choi, YongHyun Lee, Yeunwoong Kyung, and Eunchan Kim. ALBERT with Knowledge Graph Encoder Utilizing Semantic Similarity for Commonsense Question Answering. Tech Science Press, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Anson Bastos, Abhishek Nadgeri, Kuldeep Singh, Isaiah Onando Mulang’, Saeedeh Shekarpour, Johannes Hoffart, Manohar Kaul. RECON: Relation Extraction using Knowledge Graph Context in a Graph Neural Network. ACM, 2021.

- Shihui Yang, Jidong Tian, Honglun Zhang, Junchi Yan, Hao He, and Yaohui Jin. TransMS: Knowledge Graph Embedding for Complex Relations by Multidirectional Semantics. IJCAI, 2019.

- Ying Shen , Ning Ding, Hai-Tao Zheng , Yaliang Li, and Min Yang. Modeling Relation Paths for Knowledge Graph Completion. IEEE, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhiqing Sun, Zhi-Hong Deng, Jian-Yun Nie, Jian Tang. ROTATE: KNOWLEDGE GRAPH EMBEDDING BY RELATIONAL ROTATION IN COMPLEX SPACE. ICLR, 2019.

- Ines Chami, Adva Wolf, Da-Cheng Juan, Frederic Sala, Sujith Ravi and Christopher Re. Low-Dimensional Hyperbolic Knowledge Graph Embeddings. arXiv:2005.00545v1 [cs.LG] 1 May 2020.

- Feiyang Wang, Zhongbao Zhang, Li Sun, Junda Ye, Yang Yan. DiriE: Knowledge Graph Embedding with Dirichlet Distribution. ACM, 2023.

- Ivana Balaževic´, Carl Allen, Timothy Hospedales. Multi-relational Poincaré Graph Embeddings. ACM, 2019.

- Hussein Baalbakia, Hussein Hazimehb, Hassan Harbc, and Rafael Angarita. TransModE: Translational Knowledge Graph Embedding Using Modular Arithmetic. Science Direct, 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).