Submitted:

20 December 2023

Posted:

21 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Chemical Composition of Parsley Extracts

3. Parsley and the Cardiovascular Health

3.1. Antithrombotic Activity

3.2. Antihypertensive Activity

3.3. Hypolipidemic Activity

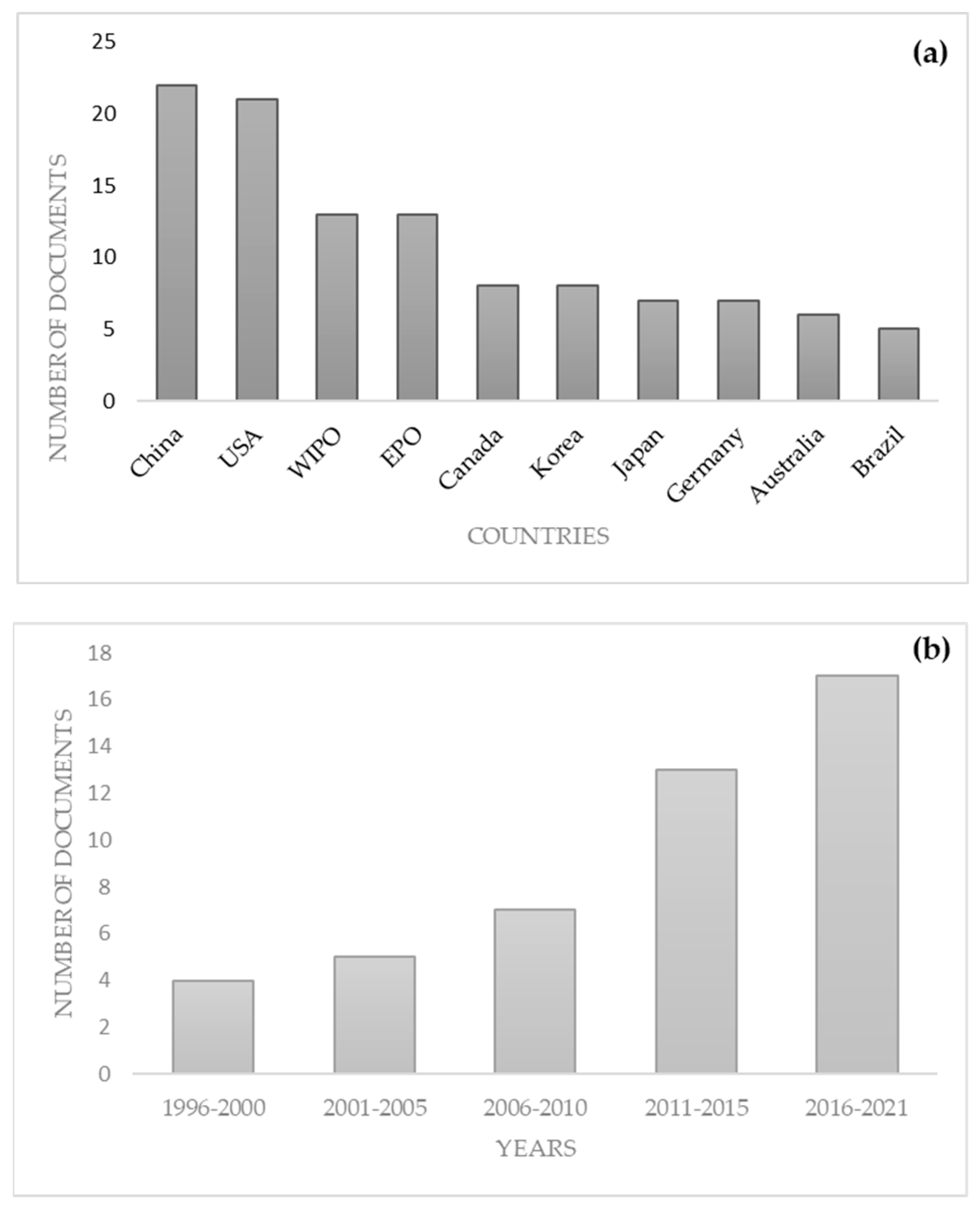

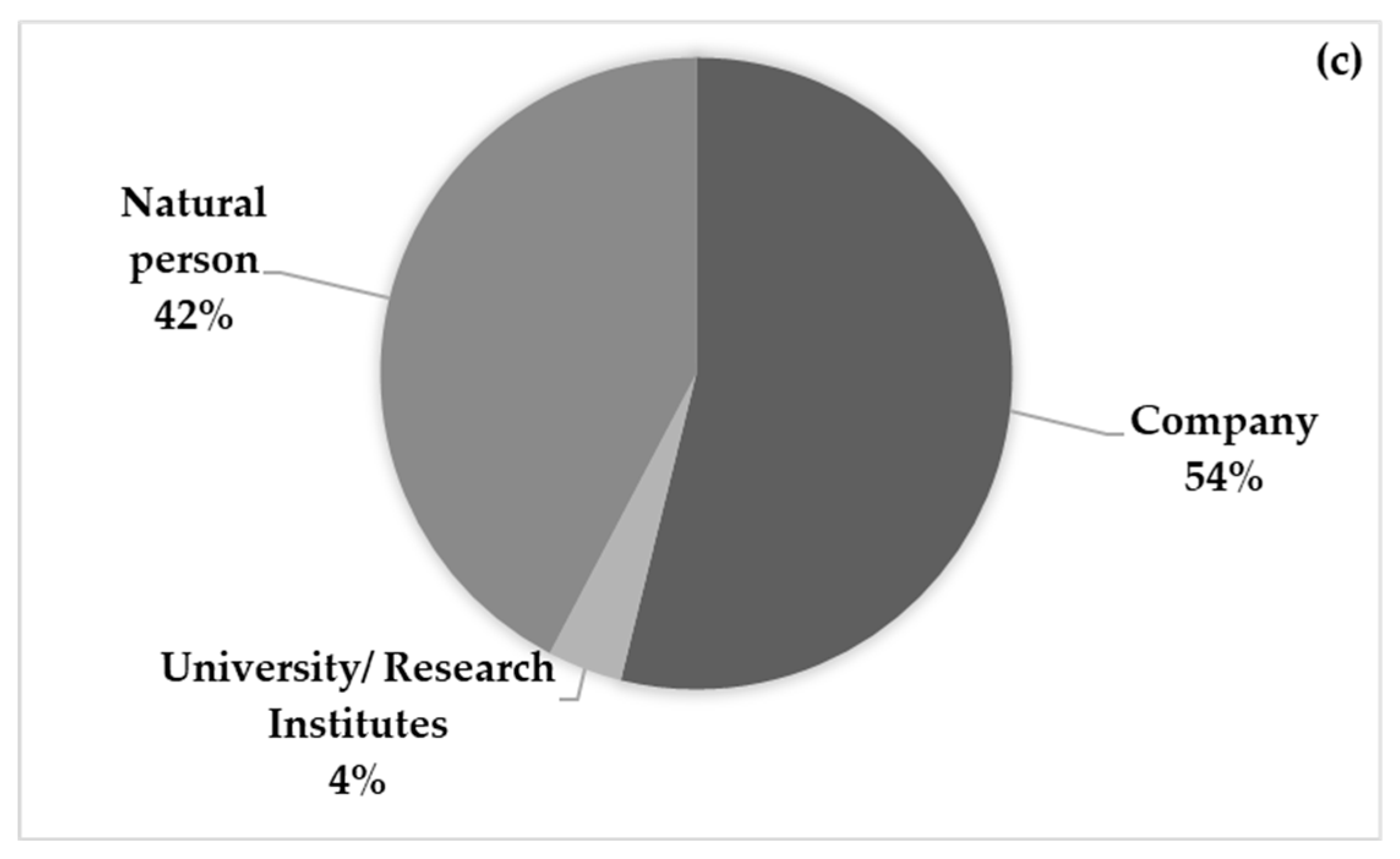

4. New Parsley-Based Nutraceuticals and Food Products: Cultivation Conditions, Applications, Patents, and Technological Aspects

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roth, G.A.; Johnson, C.; Abajobir, A.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abera, S.F.; Abyu, G.; Ahmed, M.; Aksut, B.; Alam, T.; Alam, K.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases for 10 Causes, 1990 to 2015. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2017, 70, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Ghorbani, S.; Ling, C.-C.; Yong, V.W.; Xue, M. The Extracellular Matrix as Modifier of Neuroinflammation and Recovery in Ischemic Stroke and Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Neurobiology of Disease 2023, 186, 106282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs) - Key Facts. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Leja, K.B.; Czaczyk, K. The Industrial Potential of Herbs and Spices: A Mini Review. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Technologia Alimentaria 2016, 15, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, K.; Testa, H.; Greenwood, T.; Kostek, M.; Haushalter, K.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Petersen, K.S. The Effect of Herbs and Spices on Risk Factors for Cardiometabolic Diseases: A Review of Human Clinical Trials. Nutrition Reviews 2022, 80, 400–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, S.; Eltablawy, N.A.; Hamed, M.S. Parsley: A Review of Habitat, Phytochemistry, Ethnopharmacology and Biological Activities. Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies 2016, 9, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, W.J. Health-Promoting Properties of Common Herbs. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1999, 70, 491S–499S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tohti, I.; Tursun, M.; Umar, A.; Turdi, S.; Imin, H.; Moore, N. Aqueous Extracts of Ocimum basilicum L. (Sweet Basil) Decrease Platelet Aggregation Induced by ADP and Thrombin in Vitro and Rats Arterio–Venous Shunt Thrombosis in Vivo. Thrombosis Research 2006, 118, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahleyuddin, N.N.; Moshawih, S.; Ming, L.C.; Zulkifly, H.H.; Kifli, N.; Loy, M.J.; Sarker, Md.M.R.; Al-Worafi, Y.M.; Goh, B.H.; Thuraisingam, S.; et al. Coriandrum Sativum L.: A Review on Ethnopharmacology, Phytochemistry, and Cardiovascular Benefits. Molecules 2021, 27, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Berkay Yılmaz, Y.; Antika, G.; Salehi, B.; Tumer, T.B.; Kulandaisamy Venil, C.; Das, G.; Patra, J.K.; Karazhan, N.; Akram, M.; et al. Phytochemical Constituents, Biological Activities, and Health-promoting Effects of the Genus Origanum. Phytotherapy Research 2021, 35, 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, E.S.; Aishwaya, J. Nutraceuticals Potential of Petroselinum Crispum: A Review. Journal of Complementary Medicine & Alternative Healthcare 2018, 7, 555707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaei, M.H.; Abbasabadi, Z.; Ardekani, M.R.S.; Rahimi, R.; Farzaei, F. Parsley: A Review of Ethnopharmacology, Phytochemistry and Biological Activities. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2013, 33, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobričević, N.; Šic Žlabur, J.; Voća, S.; Pliestić, S.; Galić, A.; Delić, A.; Fabek Uher, S. Bioactive Compounds Content and Nutritional Potential of Different Parsley Parts (Petroselinum Crispum Mill.). Journal of Central European Agriculture 2019, 20, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missouri Botanical Garden - Petroselinum Crispum. Available online: https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=276060 (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Santos, J.; Herrero, M.; Mendiola, J.A.; Oliva-Teles, M.T.; Ibáñez, E.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Fresh-Cut Aromatic Herbs: Nutritional Quality Stability during Shelf-Life. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2014, 59, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franciscato, L.M.S. dos S.; Mendes, S.S.; Frederico, C.; Goncalves, J.E.; Faria, M.G.I.; Gazim, Z.C.; Ruiz, S.P. Parsley (Petroselinum Crispum): Chemical Composition and Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oil from Organic against Foodborne Pathogens. Australian Journal of Crop Science 2022, 16, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seasoning & Spices Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Product (Spices, Herbs, Salt & Salts Substitutes) Report ID: GVR-2-68038-639-4. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/seasonings-spices-market (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Parsley Market by Product, Distribution Channel, and Geography - Forecast and Analysis 2023-2027. Available online: https://www.technavio.com/report/parsley-market-industry-analysis (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Patrício, K.P.; Minato, A.C.D.S.; Brolio, A.F.; Lopes, M.A.; Barros, G.R.D.; Moraes, V.; Barbosa, G.C. O Uso de Plantas Medicinais Na Atenção Primária à Saúde: Revisão Integrativa. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 2022, 27, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noureddine, B.; Mostafa, E.; Mandal, S.C. Ethnobotanical, Pharmacological, Phytochemical, and Clinical Investigations on Moroccan Medicinal Plants Traditionally Used for the Management of Renal Dysfunctions. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2022, 292, 115178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziyyat, A.; Legssyer, A.; Mekhfi, H.; Dassouli, A.; Serhrouchni, M.; Benjelloun, W. Phytotherapy of Hypertension and Diabetes in Oriental Morocco. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 1997, 58, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mootoosamy, A.; Fawzi Mahomoodally, M. Ethnomedicinal Application of Native Remedies Used against Diabetes and Related Complications in Mauritius. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2014, 151, 413–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajebli, M.; Eddouks, M. Antihypertensive Activity of Petroselinum Crispum through Inhibition of Vascular Calcium Channels in Rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2019, 242, 112039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreydiyyeh, S.I.; Usta, J. Diuretic Effect and Mechanism of Action of Parsley. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2002, 79, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, J. Natural Drugs as a Treatment Strategy for Cardiovascular Disease through the Regulation of Oxidative Stress. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2020, 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, D.; Azizi, B.; Rahimi, R.; Talasaz, A.H.; Rezaeizadeh, H.; Vasheghani-Farahani, A. Mechanism-Based Targeting of Cardiac Arrhythmias by Phytochemicals and Medicinal Herbs: A Comprehensive Review of Preclinical and Clinical Evidence. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2022, 9, 990063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, C.; Lu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, R.; Wang, W. A Review of Chinese Herbal Medicine for the Treatment of Chronic Heart Failure. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2018, 23, 5115–5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justesen, U.; Knuthsen, P.; Leth, T. Quantitative Analysis of Flavonols, Flavones, and Flavanones in Fruits, Vegetables and Beverages by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Photo-Diode Array and Mass Spectrometric Detection. Journal of Chromatography A 1998, 799, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberal, Â.; Fernandes, Â.; Polyzos, N.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Dias, M.I.; Pinela, J.; Petrović, J.; Soković, M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Barros, L. Bioactive Properties and Phenolic Compound Profiles of Turnip-Rooted, Plain-Leafed and Curly-Leafed Parsley Cultivars. Molecules 2020, 25, 5606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, A.; Carle, R.; Kammerer, D.R. Effects of Blanching on Polyphenol Stability of Innovative Paste-like Parsley (Petroselinum Crispum (Mill.) Nym Ex A. W. Hill) and Marjoram (Origanum Majorana L.) Products. Food Chemistry 2013, 138, 1648–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthria, D.L.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Kwansa, A.L. A Systematic Approach for Extraction of Phenolic Compounds Using Parsley (Petroselinum Crispum) Flakes as a Model Substrate. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2006, 86, 1350–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epifanio, N.M.D.M.; Cavalcanti, L.R.I.; Dos Santos, K.F.; Duarte, P.S.C.; Kachlicki, P.; Ożarowski, M.; Riger, C.J.; Chaves, D.S.D.A. Chemical Characterization and in Vivo Antioxidant Activity of Parsley ( Petroselinum Crispum ) Aqueous Extract. Food & Function 2020, 11, 5346–5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechtenberg, M.; Zumdick, S.; Engelshowe, R.; Gerhards, C.; Schmidt, T.; Hensel, A. Evaluation of Analytical Markers Characterising Different Drying Methods of Parsley Leaves (Petroselinum Crispum L.). Planta Medica 2006, 72, s–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, D.S.A.; Frattani, F.S.; Assafim, M.; de Almeida, A.P.; Zingali, R.B.; Costa, S.S. Phenolic Chemical Composition of Petroselinum Crispum Extract and Its Effect on Haemostasis. Natural Product Communications 2011, 6, 1934578X1100600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frattani, F.S.; Assafim, M.; Casanova, L.M.; de Souza, J.E.; Chaves, D.S. de A.; Costa, S.S.; Zingali, R.B. Oral Treatment with a Chemically Characterized Parsley (Petroselinum Crispum Var. Neapolitanum Danert) Aqueous Extract Reduces Thrombi Formation in Rats. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2021, 11, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, S.E.; Young, J.F.; Daneshvar, B.; Lauridsen, S.T.; Knuthsen, P.; Sandström, B.; Dragsted, L.O. Effect of Parsley ( Petroselinum Crispum ) Intake on Urinary Apigenin Excretion, Blood Antioxidant Enzymes and Biomarkers for Oxidative Stress in Human Subjects. British Journal of Nutrition 1999, 81, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, H.; Bolarinwa, A.; Wolfram, G.; Linseisen, J. Bioavailability of Apigenin from Apiin-Rich Parsley in Humans. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 2006, 50, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, A.; Ming, Y.; Pengyi, H.; Jie, K.Y.; Yali, L.; Haiyan, Z.; Shuai, X.; Wenjing, L.; Ling, W.; Xia, Z.M.; et al. The Fate of Flavonoids after Oral Administration: A Comprehensive Overview of Its Bioavailability. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 62, 6169–6186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, G.; Fong, R.Y.; Ensunsa, J.L.; Kimball, J.; Medici, V.; Ottaviani, J.I.; Crozier, A. Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Excretion of Apigenin and Its Glycosides in Healthy Male Adults. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2022, 185, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proz, M.D.L.Á.; Da Silva, M.A.S.; Rodrigues, E.; Bender, R.J.; Rios, A.D.O. Effects of Indoor, Greenhouse, and Field Cultivation on Bioactive Compounds from Parsley and Basil. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2021, 101, 6320–6330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sbai, H.; Saad, I.; Ghezal, N.; Greca, M.D.; Haouala, R. Bioactive Compounds Isolated from Petroselinum Crispum L. Leaves Using Bioguided Fractionation. Industrial Crops and Products 2016, 89, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Uemura, T.; Shimoda, H.; Kishi, A.; Kawahara, Y.; Matsuda, H. Medicinal Foodstuffs. XVIII. Phytoestrogens from the Aerial Part of Petroselinum Crispum MILL. (PARSLEY) and Structures of 6"-Acetylapiin and a New Monoterpene Glycoside, Petroside. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2000, 48, 1039–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staropoli, A.; Vassetti, A.; Salvatore, M.M.; Andolfi, A.; Prigigallo, M.I.; Bubici, G.; Scagliola, M.; Salerno, P.; Vinale, F. Improvement of Nutraceutical Value of Parsley Leaves (Petroselinum Crispum) upon Field Applications of Beneficial Microorganisms. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derouich, M.; Bouhlali, E.D.T.; Bammou, M.; Hmidani, A.; Sellam, K.; Alem, C. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant, Antiperoxidative, and Antihemolytic Properties Investigation of Three Apiaceae Species Grown in the Southeast of Morocco. Scientifica 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.R.; Sechsadri, F.A.Sc. A Study of Apiin from the Parsley Seeds and Plant. Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences - Section A 1952, 35, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piras, A.; Porcedda, S.; Falconieri, D.; Fais, A.; Era, B.; Carta, G.; Rosa, A. Supercritical Extraction of Volatile and Fixed Oils from Petroselinum Crispum L. Seeds: Chemical Composition and Biological Activity. Natural Product Research 2022, 36, 1883–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Calderon, O.; Saleh, A.M.; Mahmood, A.A.R.; Khalaf, M.A.; Calva, J.; Loyola-Gonzales, E.; Tataje-Napuri, F.E.; Chávez, H.; Almeida-Galindo, J.S.; Chavez-Espinoza, J.H.; et al. The Essential Oil of Petroselinum Crispum (Mill) Fuss Seeds from Peru: Phytotoxic Activity and In Silico Evaluation on the Target Enzyme of the Glyphosate Herbicide. Plants 2023, 12, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekhfi, H.; Haouari, M.E.; Legssyer, A.; Bnouham, M.; Aziz, M.; Atmani, F.; Remmal, A.; Ziyyat, A. Platelet Anti-Aggregant Property of Some Moroccan Medicinal Plants. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2004, 94, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadi, D.; Bnouham, M.; Aziz, M.; Ziyyat, A.; Legssyer, A.; Legrand, C.; Lafeve, F.F.; Mekhfi, H. Parsley Extract Inhibits in Vitro and Ex Vivo Platelet Aggregation and Prolongs Bleeding Time in Rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2009, 125, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadi, D.; Bnouham, M.; Aziz, M.; Ziyyat, A.; Legssyer, A.; Bruel, A.; Berrabah, M.; Legrand, C.; Fauvel-Lafeve, F.; Mekhfi, H. Flavonoids Purified from Parsley Inhibit Human Blood Platelet Aggregation and Adhesion to Collagen under Flow. Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine 2012, 9, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, K.E.D.; Balbi, A.P.C.; Alves, M.J.Q.D.F. Diuretic and Hipotensive Activity of Aqueous Extract of Parsley Seeds (Petroselinum Sativum Hoffm.) in Rats. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia 2009, 19, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, H.A.; Eltablawy, N.A.; Hamed, M.S. The Ameliorative Effect of Petroselinum Crispum (Parsley) on Some Diabetes Complications. Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies 2015, 3, 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- El Rabey, H.A.; Al-Seeni, M.N.; Al-Ghamdi, H.B. Comparison between the Hypolipidemic Activity of Parsley and Carob in Hypercholesterolemic Male Rats. BioMed Research International 2017, 2017, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashorobi, D.; Ameer, M.A.; Fernandez, R. Thrombosis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wendelboe, A.M.; Raskob, G.E. Global Burden of Thrombosis: Epidemiologic Aspects. Circulation Research 2016, 118, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delluc, A.; Lacut, K.; Rodger, M.A. Arterial and Venous Thrombosis: What’s the Link? A Narrative Review. Thrombosis Research 2020, 191, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thachil, J. Deep Vein Thrombosis. Hematology 2014, 19, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi, G.; Favaloro, E. Venous and Arterial Thromboses: Two Sides of the Same Coin? Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis 2018, 44, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Núñez, L.; Lozano, M.L.; Palomo, M.; Martínez, C.; Vicente, V.; Castillo, J.; Benavente-García, O.; Diaz-Ricart, M.; Escolar, G.; Rivera, J. Apigenin Inhibits Platelet Adhesion and Thrombus Formation and Synergizes with Aspirin in the Suppression of the Arachidonic Acid Pathway. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2008, 56, 2970–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero, J.A.; Lozano, M.L.; Castillo, J.; Benavente-García, O.; Vicente, V.; Rivera, J. Flavonoids Inhibit Platelet Function through Binding to the Thromboxane A2 Receptor. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2005, 3, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Núñez, L.; Rivera, J.; Guerrero, J.; Martínez, C.; Vicente, V.; Lozano, M. Differential Effects of Quercetin, Apigenin and Genistein on Signalling Pathways of Protease-Activated Receptors PAR1 and PAR4 in Platelets: Flavonoids Inhibit PAR1 and PAR4 Signalling Cascades. British Journal of Pharmacology 2009, 158, 1548–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiailanis, A.D.; Tellis, C.C.; Papakyriakopoulou, P.; Kostagianni, A.D.; Gkalpinos, V.; Chatzigiannis, C.M.; Kostomitsopoulos, N.; Valsami, G.; Tselepis, A.D.; Tzakos, A.G. Development of a Novel Apigenin Dosage Form as a Substitute for the Modern Triple Antithrombotic Regimen. Molecules 2023, 28, 2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, F.D.; Whelton, P.K. High Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease. Hypertension 2020, 75, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Hypertension - Key Facts. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Ozemek, C.; Laddu, D.R.; Arena, R.; Lavie, C.J. The Role of Diet for Prevention and Management of Hypertension. Current Opinion in Cardiology 2018, 33, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, N.R.; McCormack, T.; Constanti, M.; McManus, R.J. Diagnosis and Management of Hypertension in Adults: NICE Guideline Update 2019. British Journal of General Practice 2020, 70, 90–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnier, M.; Bakris, G.; Williams, B. Redefining Diuretics Use in Hypertension: Why Select a Thiazide-like Diuretic? Journal of Hypertension 2019, 37, 1574–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vranješ, M.; Popović, B.M.; Štajner, D.; Ivetić, V.; Mandić, A.; Vranješ, D. Effects of Bearberry, Parsley and Corn Silk Extracts on Diuresis, Electrolytes Composition, Antioxidant Capacity and Histopathological Features in Mice Kidneys. Journal of Functional Foods 2016, 21, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Je, H.D.; Kim, H.-D.; La, H.-O. The Inhibitory Effect of Apigenin on the Agonist-Induced Regulation of Vascular Contractility via Calcium Desensitization-Related Pathways. Biomolecules & Therapeutics 2014, 22, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.-Y.; Gao, T.; Huang, Y.; Xue, J.; Xie, M.-L. Apigenin Ameliorates Hypertension-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy and down-Regulates Cardiac Hypoxia Inducible Factor-Lα in Rats. Food & Function 2016, 7, 1992–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, A.R.; Huckaby, L.V.; Shiva, S.S.; Zuckerbraun, B.S. Nitric Oxide and Endothelial Dysfunction. Critical Care Clinics 2020, 36, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes, M.; Romecín, P.; Atucha, N.; O’Valle, F.; Castillo, J.; Ortiz, M.; García-Estañ, J. Beneficial Effects of Different Flavonoids on Vascular and Renal Function in L-NAME Hypertensive Rats. Nutrients 2018, 10, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes, M.; Romecín, P.; Atucha, N.; O’Valle, F.; Castillo, J.; Ortiz, M.; García-Estañ, J. Moderate Effect of Flavonoids on Vascular and Renal Function in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirillo, A.; Casula, M.; Olmastroni, E.; Norata, G.D.; Catapano, A.L. Global Epidemiology of Dyslipidaemias. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2021, 18, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopin, L.; Lowenstein, C.J. Dyslipidemia. Annals of Internal Medicine 2017, 167, ITC81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Fogacci, F.; Stoian, A.P.; Vrablik, M.; Al Rasadi, K.; Banach, M.; Toth, P.P.; Rizzo, M. Nutraceuticals in the Management of Dyslipidemia: Which, When, and for Whom? Could Nutraceuticals Help Low-Risk Individuals with Non-Optimal Lipid Levels? Current Atherosclerosis Reports 2021, 23, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahiru, E.; Hsiao, R.; Phillipson, D.; Watson, K.E. Mechanisms and Treatment of Dyslipidemia in Diabetes. Current Cardiology Reports 2021, 23, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feingold, K.R. Dyslipidemia in Diabetes; Feingold, K.R., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M.R., Boyce, A., Chrousos, G., Corpas, E., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., Hofland, J., Kalra, S., Kaltsas, G., Kapoor, N., Koch, C., Kopp, P., Korbonits, M., Kovacs, C.S., Kuohung, W., Laferrère, B., Levy, M., McGee, E.A., McLachlan, R., New, M., Purnell, J., Sahay, R., Shah, A.S., Singer, F., Sperling, M.A., Stratakis, C.A., Trence, D.L., Wilson, D.P., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth (MA), 2000.

- Jung, U.; Cho, Y.-Y.; Choi, M.-S. Apigenin Ameliorates Dyslipidemia, Hepatic Steatosis and Insulin Resistance by Modulating Metabolic and Transcriptional Profiles in the Liver of High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Nutrients 2016, 8, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, L.; Cheng, Q.; Ji, B.; Yang, M.; Sanidad, K.Z.; Wang, C.; Zhou, F. Structurally Different Flavonoid Subclasses Attenuate High-Fat and High-Fructose Diet Induced Metabolic Syndrome in Rats. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2018, 66, 12412–12420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, T.Y.; Tan, Y.Q.; Lin, S.; Leung, L.K. Co-Administrating Apigenin in a High-Cholesterol Diet Prevents Hypercholesterolaemia in Golden Hamsters. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2018, 70, 1253–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, K.J.; Lopez, R.G. Modeling Growth and Development of Hydroponically Grown Dill, Parsley, and Watercress in Response to Photosynthetic Daily Light Integral and Mean Daily Temperature. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuolienė, G.; Viršilė, A.; Brazaitytė, A.; Jankauskienė, J.; Sakalauskienė, S.; Vaštakaitė, V.; Novičkovas, A.; Viškelienė, A.; Sasnauskas, A.; Duchovskis, P. Blue Light Dosage Affects Carotenoids and Tocopherols in Microgreens. Food Chemistry 2017, 228, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuolienė, G.; Brazaitytė, A.; Viršilė, A.; Jankauskienė, J.; Sakalauskienė, S.; Duchovskis, P. Red Light-Dose or Wavelength-Dependent Photoresponse of Antioxidants in Herb Microgreens. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carillo, P.; El-Nakhel, C.; De Micco, V.; Giordano, M.; Pannico, A.; De Pascale, S.; Graziani, G.; Ritieni, A.; Soteriou, G.A.; Kyriacou, M.C.; et al. Morpho-Metric and Specialized Metabolites Modulation of Parsley Microgreens through Selective LED Wavebands. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.S.; De Oliveira, V.S.; Chávez, D.W.H.; Chaves, D.S.; Riger, C.J.; Sawaya, A.C.H.F.; Guizellini, G.M.; Sampaio, G.R.; Torres, E.A.F.D.S.; Saldanha, T. Bioactive Compounds of Parsley (Petroselinum Crispum), Chives (Allium Schoenoprasum L) and Their Mixture (Brazilian Cheiro-Verde) as Promising Antioxidant and Anti-Cholesterol Oxidation Agents in a Food System. Food Research International 2022, 151, 110864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, V.S.; Chávez, D.W.H.; Paiva, P.R.F.; Gamallo, O.D.; Castro, R.N.; Sawaya, A.C.H.F.; Sampaio, G.R.; Torres, E.A.F.D.S.; Saldanha, T. Parsley (Petroselinum Crispum Mill.): A Source of Bioactive Compounds as a Domestic Strategy to Minimize Cholesterol Oxidation during the Thermal Preparation of Omelets. Food Research International 2022, 156, 111199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sęczyk, Ł.; Świeca, M.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Luty, M.; Czyż, J. Effect of Fortification with Parsley ( Petroselinum Crispum Mill.) Leaves on the Nutraceutical and Nutritional Quality of Wheat Pasta. Food Chemistry 2016, 190, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziki, D.; Hassoon, W.H.; Biernacka, B.; Gawlik-Dziki, U. Dried and Powdered Leaves of Parsley as a Functional Additive to Wheat Bread. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 7930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouasla, A.; Gassi, H.E.; Lisiecka, K.; Wójtowicz, A. Application of Parsley Leaf Powder as Functional Ingredient in Fortified Wheat Pasta: Nutraceutical, Physical and Organoleptic Characteristics. International Agrophysics 2022, 36, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnin, K.K.; Zhang, M.; Ju, R.; Wang, B. A Novel Infrared Pulse-Spouted Freeze Drying on the Drying Kinetics, Energy Consumption and Quality of Edible Rose Flowers. LWT 2021, 136, 110318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouhoubi, K.; Boulekbache-Makhlouf, L.; Madani, K.; Palatzidi, A.; Perez-Jimenez, J.; Mateos-Aparicio, I.; Garcia-Alonso, A. Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity Are Differentially Affected by Drying Processes in Celery, Coriander and Parsley Leaves. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2022, 57, 3467–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, S.M. Effect of Microwave Treatments on Some Bioactive Compounds of Parsley (Petroselinum Crispum) and Dill (Anethum Graveolens) Leaves. Journal of Food Processing & Technology 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, A.; Brinkmann, M.; Carle, R.; Kammerer, D.R. Influence of Thermal Treatment on Color, Enzyme Activities, and Antioxidant Capacity of Innovative Pastelike Parsley Products. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2012, 60, 3291–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helal, N.A.; Eassa, H.A.; Amer, A.M.; Eltokhy, M.A.; Edafiogho, I.; Nounou, M.I. Nutraceuticals’ Novel Formulations: The Good, the Bad, the Unknown and Patents Involved. Recent Patents on Drug Delivery & Formulation 2019, 13, 105–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmy, A.; El-Shazly, M.; Seleem, A.; Abdelmohsen, U.; Salem, M.A.; Samir, A.; Rabeh, M.; Elshamy, A.; Singab, A.N.B. The Synergistic Effect of Biosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles from a Combined Extract of Parsley, Corn Silk, and Gum Arabic: In Vivo Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Antimicrobial Activities. Materials Research Express 2020, 7, 025002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, M.; Kon, K.; Ingle, A.; Duran, N.; Galdiero, S.; Galdiero, M. Broad-Spectrum Bioactivities of Silver Nanoparticles: The Emerging Trends and Future Prospects. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2014, 98, 1951–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) World Intellectual Property Indicators Report: Record Number of Patent Applications Filed Worldwide in 2022. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/pressroom/en/articles/2023/article_0013.html#:~:text=Registrations%20in%20force%20in%20China,)%20and%20Japan%20(270%2C073) (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- Rostagno, M.A.; Prado, J.M. Natural Product Extraction: Principles and Applications; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Optimal Health StemSation StemRCM. Available online: https://optimal-health.uk/stemsation-stemrcm (accessed on 8 December 2023).

| Chemical class | Compounds | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coumarins |

|

|

[34,41,42,43] |

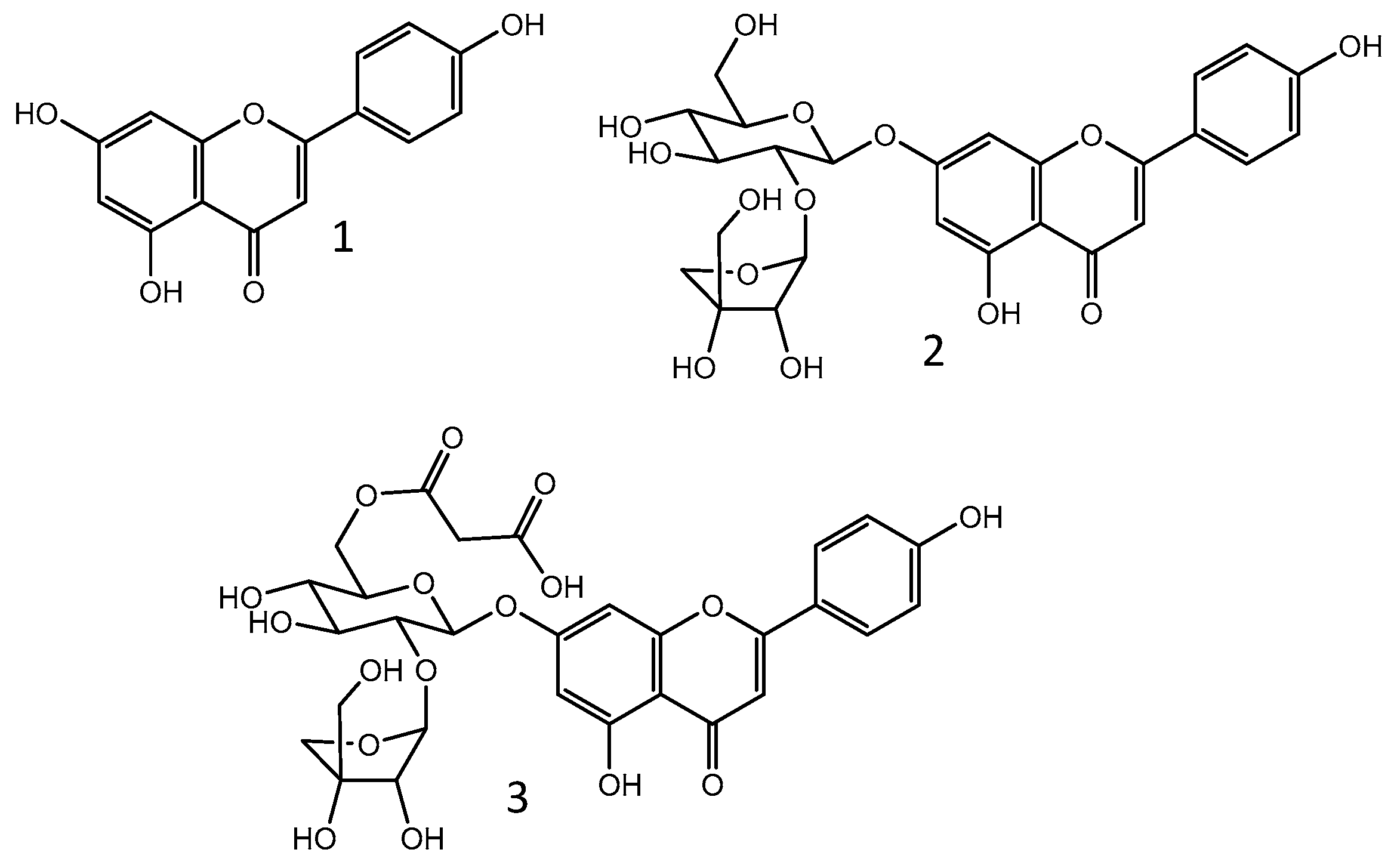

| Flavonoids (flavones) |

|

|

[29,30,31,32,34,35,40,42,44] |

| Flavonoids (flavonols) |

|

|

[29,32,40,42,44] |

| Phenolic acids and derivatives |

|

|

[30,35,40,44] |

| Miscellaneous |

|

|

[42,43] |

| Activity | Plant part | Type of extract | Type of study | Main outcomes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antithrombotic | Aerial parts | Infusion (5.5 g in 100 mL); 30 min | In vitro | Inhibition of thrombin and ADP-induced platelet aggregation (IC50 6.4 and 6.7 mg/mL, respect.) | [48] |

| Leaves | Infusion (10% w/v); 30 min |

In vivo and ex vivo (rats) | A 2-fold increase of bleeding time after a single oral dose (3 g/kg) increase of approx. 20% in thrombin, ADP and collagen-induced platelet aggregation in blood collected from treated rats. | [49] | |

| Leaves | Decoction (10% w/v); 10 min |

In vitro | Inhibition of ADP-induced platelet aggregation (IC50 1.81 mg/mL); apigenin and cosmosiin isolated from the extract also inhibited ADP-induced aggregation (IC50 0.036 and 0.18 mg/mL, respect.) | [34] | |

| Leaves | Fraction enriched in aglicone flavonoids | In vitro | Inhibition of thrombin, ADP, and collagen-induced platelet aggregation (IC50 0.16; 0.28 and 0.08, respect.) | [50] | |

| Aerial parts | Decoction (30% w/v); 10 min |

In vivo and ex vivo (rats) | An oral dose (125 mg/kg), 60 min before venous induction inhibited thrombus formation by 76.2%. In arterial thrombosis model, the oral doses of 15 or 25 mg/kg, 60 min before induction, increased the carotid artery occlusion time by 150% and 240%, resp. Treatments produced antiplatelet (recalcification time ex vivo assay) but not anticoagulant activity (PT and aPTT ex vivo assays). |

[35] | |

| Antihypertensive | Seeds | Infusion (20% w/v); 5 min |

In vivo (rats) | Treatment with 1 mL extract orally produced approx. 20% reduction in blood pressure after 90 min. Effect related to diuretic activity. | [51] |

| Leaves | Decoction (1% w/v); 10 min |

In vivo (rats) | A single oral dose (160 mg/kg) reduced systolic and diastolic pressure of hypertensive rats in approx. 20%, while daily treatment for seven days (160 mg/kg) resulted in a 30% decrease in the 7th day. Effects possibly related to vasodilatory activity. | [23] | |

| Hypolipidemic | Leaves | Decoction (10% w/v); 30 min |

In vivo (rats) | Diabetic rats orally treated with a daily dose (2g/kg b.wt.) of extract for 45 days showed levels of TC, TG, LDL and HDL similar to untreated normal rats. | [52] |

| Seeds | Methanol extract (20% w/v); 5 days in low temperature | In vivo (rats) | Oral administration of extract partially prevented the effects of hypercholesterolemic diet; Treated rats showed 20-30% lower levels of TC, TG, LDL, and VLDL and 20% higher HDL approx.* | [53] |

| Patent number | Year | Status | Type of product | Application | Plant use | Plant part |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WO22079063 | 2020 | Not granted | Extract | Food emulsifiers | Extract | Leaves |

| WO18172998 | 2017 | Granted/ Not granted | Composition | Dietary supplement | Extract | Plant |

| WO18083115 | 2016 | Granted/ Not granted | Herbal composition | Food supplement, nutraceutical | Dry plant | Fruits |

| CN105942235 | 2016 | Refused | Composition | Appetite promoting | 1-2 parts of plant | Leaves |

| KR20180067916 | 2016 | Not granted | Herbal composition | Functional food | Fresh plant | Leaves |

| US2016242440 | 2015 | Cancelled | Food additive composition | Food enhancer | 5-15% of plant | Not described |

| US2016166602 | 2014 | Cancelled | Composition | Dietary supplement | 0.1-0.8% of plant | Not described |

| US2016015763 | 2011 | Cancelled | Nutraceutical formula | Nutraceutical | Extract | Root |

| US2008219964 | 2006 | Dead, suspended | Ingestible product | Nutraceutical | Fresh plant | Leaves |

| EP1616489 | 2004 | Cancelled | Composition | Food supplement/additive | Extract | Not described |

| EP1602364 | 2004 | Cancelled | Microcapsules | Food supplement | Extract | Not described |

| WO9850054 | 1997 | Expired, dead | Nutritional composition | Nutraceutical | Extract | Plant |

| EP0799579 | 1996 | Expired | Composition | Food supplement | Extract | Not described |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).