Submitted:

19 December 2023

Posted:

20 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

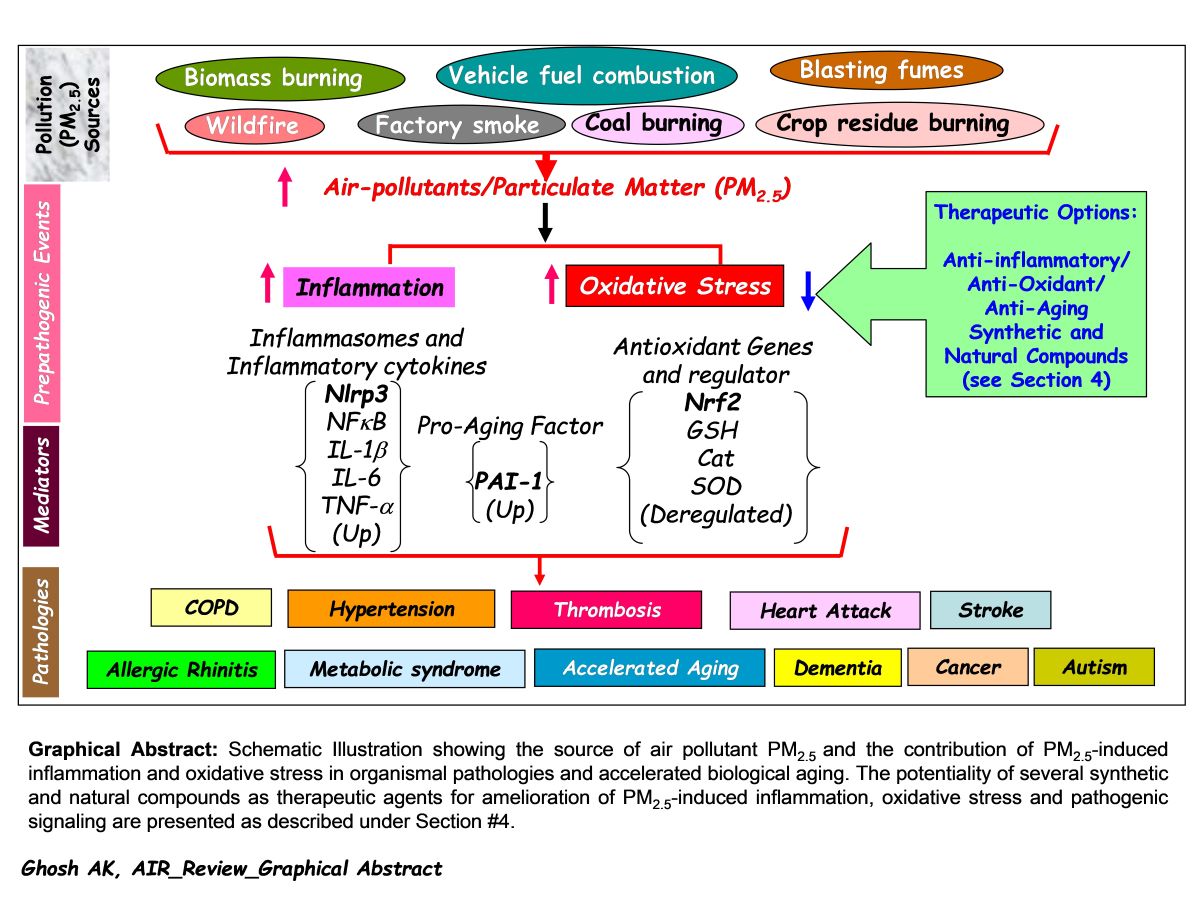

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Air-Pollutant Particulate Matter (PM) and Its Mode of Action

3. PM2.5 in Induction of Massive Inflammation and Oxidative Stress: Major Causes for the Initiation and Progression of Pathologies

3.1. PM2.5 Induces Inflammation and Oxidative Stress: Evidence from Gene Expression Profiling

, IL-17 signaling and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction; in liver, PM2.5 alters the expressions of numerous genes involved in metabolic signaling pathways including AMPK signaling, JAK-Stat signaling, cytokine-cytokine receptor and PPAR signaling [26]. Similarly, exposure of human and mouse macrophages to PM2.5 (400-500 µg/ml) causes generation of oxidative stress (ROS), activation of inflammatory NF

, IL-17 signaling and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction; in liver, PM2.5 alters the expressions of numerous genes involved in metabolic signaling pathways including AMPK signaling, JAK-Stat signaling, cytokine-cytokine receptor and PPAR signaling [26]. Similarly, exposure of human and mouse macrophages to PM2.5 (400-500 µg/ml) causes generation of oxidative stress (ROS), activation of inflammatory NF B signaling, secretion of inflammatory cytokines IL-1

B signaling, secretion of inflammatory cytokines IL-1 , TNF-

, TNF- and impaired phagocytosis, and thus disrupt inflammatory cell clearance by macrophages [27]. Furthermore, RNA seq analysis of RNA extracted from control and PM2.5 (500 µg/ml for 24h) exposed PMA-primed THP-1 human macrophages reveal that expression of 1213 genes involved in different cellular pathways are deregulated by PM2.5 including upregulation of IL-17, NF

and impaired phagocytosis, and thus disrupt inflammatory cell clearance by macrophages [27]. Furthermore, RNA seq analysis of RNA extracted from control and PM2.5 (500 µg/ml for 24h) exposed PMA-primed THP-1 human macrophages reveal that expression of 1213 genes involved in different cellular pathways are deregulated by PM2.5 including upregulation of IL-17, NF B, TNF-

B, TNF- , and PPAR-

, and PPAR- signaling pathways and downregulation of PI3K/AKT and cytokine-receptor interaction pathways [27]. Previously, we demonstrated that a short-term exposure (72h) to PM2.5 (200µg/mouse) causes elevated levels of inflammatory markers Mac3, pStat3 and Vcam1 and apoptotic marker cleaved caspase 3 in murine lung and heart tissues [28]. Recently, we performed RNA seq analysis of RNA extracted from controls and PM2.5 (200 µg/mouse) instilled (72h) murine lungs. The gene ontology analysis revealed that PM2.5 significantly upregulated inflammatory pathway as shown by deregulation of many inflammatory genes including Nlrp3, IL-1

signaling pathways and downregulation of PI3K/AKT and cytokine-receptor interaction pathways [27]. Previously, we demonstrated that a short-term exposure (72h) to PM2.5 (200µg/mouse) causes elevated levels of inflammatory markers Mac3, pStat3 and Vcam1 and apoptotic marker cleaved caspase 3 in murine lung and heart tissues [28]. Recently, we performed RNA seq analysis of RNA extracted from controls and PM2.5 (200 µg/mouse) instilled (72h) murine lungs. The gene ontology analysis revealed that PM2.5 significantly upregulated inflammatory pathway as shown by deregulation of many inflammatory genes including Nlrp3, IL-1 , TNFrsf8, 9, 11a, 12a, 1b, and NF-

, TNFrsf8, 9, 11a, 12a, 1b, and NF- B2. In addition, many downregulated genes in response to PM2.5 participate in metabolism (Ghosh AK et al. unpublished data). Collectively, these results on the impacts of air pollutant PM2.5 on global gene expression profiling under different experimental milieus reveal that many commons signaling pathways are deregulated by PM2.5 exposure including significant activation of inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways.

B2. In addition, many downregulated genes in response to PM2.5 participate in metabolism (Ghosh AK et al. unpublished data). Collectively, these results on the impacts of air pollutant PM2.5 on global gene expression profiling under different experimental milieus reveal that many commons signaling pathways are deregulated by PM2.5 exposure including significant activation of inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways.3.2. PM2.5-Induced Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Allergic Rhinitis

, IL-5, IL-12, IL-13, chemokine KC in lungs, PM2.5 fails to increase inflammation in TLR2 or TLR4 or MyD88 deficient mice [31]. Comparable results were obtained by Wang and colleagues [32] in an asthma mouse model exposed to PM2.5. Collectively, these results suggest that exposure to PM2.5 aggravates allergic reaction where both inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways contribute to aggravated pulmonary symptoms in mouse model of AR and Asthma.

, IL-5, IL-12, IL-13, chemokine KC in lungs, PM2.5 fails to increase inflammation in TLR2 or TLR4 or MyD88 deficient mice [31]. Comparable results were obtained by Wang and colleagues [32] in an asthma mouse model exposed to PM2.5. Collectively, these results suggest that exposure to PM2.5 aggravates allergic reaction where both inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways contribute to aggravated pulmonary symptoms in mouse model of AR and Asthma.3.3. PM2.5-Induced Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Fibrogenesis

and TNF-

and TNF- by γδT and Th17 cells those lead to a massive inflammation and lung injury. Further, PM2.5 stimulates the levels of TGF-

by γδT and Th17 cells those lead to a massive inflammation and lung injury. Further, PM2.5 stimulates the levels of TGF- 1, Smad-dependent TGF-

1, Smad-dependent TGF- profibrogenic responses including myofibroblast differentiation, excessive collagen synthesis and fibrogenesis [33]. Further, the PM2.5-activated profibrogenic pathway is diminished in IL-17A null murine lung tissues compared to wildtype mice indicating IL-17A aggravates PM2.5-induced inflammation and lung fibrogenesis [33]. Similarly, exposure to PM2.5 increases lung injury, decreases lung functions including lung vital capacity and airway resistance through induction of inflammation and oxidative stress in mice and mouse bronchial epithelium cells as evidenced by elevated levels of IL-1

profibrogenic responses including myofibroblast differentiation, excessive collagen synthesis and fibrogenesis [33]. Further, the PM2.5-activated profibrogenic pathway is diminished in IL-17A null murine lung tissues compared to wildtype mice indicating IL-17A aggravates PM2.5-induced inflammation and lung fibrogenesis [33]. Similarly, exposure to PM2.5 increases lung injury, decreases lung functions including lung vital capacity and airway resistance through induction of inflammation and oxidative stress in mice and mouse bronchial epithelium cells as evidenced by elevated levels of IL-1 , IL-16, PI3K/mTOR signaling pathways [34]. Importantly, exposure to low, medium, and high doses of PM2.5 (3 mg, 8 mg, 13 mg/kg body weight/once per week for 4 weeks) induces worst inflammation and lung injury as shown by increased expression of ACP, CRP, VEGF, and IL-6 in broncho alveolar lavage fluid compared to control rats. Additionally, the protein levels of VEGF, JAK2, Stat3 and matrix protein collagen are significantly elevated in PM2.5-treated rat lung tissues compared to controls [35]. These results suggest that PM2.5-induced PI3K/mTOR and JAK/Stat3 signaling pathways may contribute to massive lung inflammation and fibrogenesis. Interestingly, exposures of mice to printing room generated PM2.5 (5µg, 10µg or 15µg/g BW on day 1 and 3) significantly increased malondialdehyde (MDA) activity, increased expression of inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β, TNF-

, IL-16, PI3K/mTOR signaling pathways [34]. Importantly, exposure to low, medium, and high doses of PM2.5 (3 mg, 8 mg, 13 mg/kg body weight/once per week for 4 weeks) induces worst inflammation and lung injury as shown by increased expression of ACP, CRP, VEGF, and IL-6 in broncho alveolar lavage fluid compared to control rats. Additionally, the protein levels of VEGF, JAK2, Stat3 and matrix protein collagen are significantly elevated in PM2.5-treated rat lung tissues compared to controls [35]. These results suggest that PM2.5-induced PI3K/mTOR and JAK/Stat3 signaling pathways may contribute to massive lung inflammation and fibrogenesis. Interestingly, exposures of mice to printing room generated PM2.5 (5µg, 10µg or 15µg/g BW on day 1 and 3) significantly increased malondialdehyde (MDA) activity, increased expression of inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β, TNF- , and IL-6 and decreased expression of antioxidant SOD on day 4 of exposure. In addition, primary profibrogenic signaling mediator TGF-

, and IL-6 and decreased expression of antioxidant SOD on day 4 of exposure. In addition, primary profibrogenic signaling mediator TGF- -induced pERK1-MAPK activity is also increased by PM2.5 indicating exposure for a significant amount of time to print room-generated PM2.5 is a major risk factor for increased lung oxidative stress, inflammation, pyroptosis and pulmonary fibrosis [36].

-induced pERK1-MAPK activity is also increased by PM2.5 indicating exposure for a significant amount of time to print room-generated PM2.5 is a major risk factor for increased lung oxidative stress, inflammation, pyroptosis and pulmonary fibrosis [36].  B and Akt signaling are significantly elevated in hearts of PM2.5 exposed mice. Therefore, Nlrp3/NF

B and Akt signaling are significantly elevated in hearts of PM2.5 exposed mice. Therefore, Nlrp3/NF B-induced inflammation may contribute to PM2.5-induced cardiac pathologies including fibrogenesis [37]. As HDAC3 plays a key role in regulation of inflammatory genes and control inflammation in response to external stresses, the significance of HDAC3 in PM2.5-induced inflammation-related symptoms in mice has been examined [38]. While PM2.5 inhalation (101.5+/- 2.3 µg/^m3, flow rate: 75L/min for 6h/day/5 time per week) induces the Smad-dependent TGF-

B-induced inflammation may contribute to PM2.5-induced cardiac pathologies including fibrogenesis [37]. As HDAC3 plays a key role in regulation of inflammatory genes and control inflammation in response to external stresses, the significance of HDAC3 in PM2.5-induced inflammation-related symptoms in mice has been examined [38]. While PM2.5 inhalation (101.5+/- 2.3 µg/^m3, flow rate: 75L/min for 6h/day/5 time per week) induces the Smad-dependent TGF- signaling in wildtype mice, this profibrogenic signaling is further activated in lungs derived from PM2.5-exposed HDAC3 deficient mice [38]. Therefore, specific activation of HDAC3 may be a viable approach to control the extent of PM2.5-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis. Exposure to concentrated PM2.5 (671.87µg/m^3 for 8 or 16 weeks, 6 h/day) also imparts its negative influence on the cardiac structure and function as shown by cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, and abnormal cardiac systolic function. PM2.5 induces inflammation through activation of PI3K/Akt/FOXO1 signaling pathways that contribute to cardiac hypertrophy and fibrogenesis [39]. Furthermore, the offspring from mice exposed to PM2.5 during gestation period develop cardiac hypertrophy that is associated with increased levels of acetyltransferase p300, acetylated H3K9 and cardiac transcriptional regulators Gata4 and Mef2c [40]. Therefore, prenatal, or postnatal exposure to environmental pollutant PM2.5 induces cardiac inflammation, cellular apoptosis, fibrogenesis and abnormal cardiac structure and function.

signaling in wildtype mice, this profibrogenic signaling is further activated in lungs derived from PM2.5-exposed HDAC3 deficient mice [38]. Therefore, specific activation of HDAC3 may be a viable approach to control the extent of PM2.5-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis. Exposure to concentrated PM2.5 (671.87µg/m^3 for 8 or 16 weeks, 6 h/day) also imparts its negative influence on the cardiac structure and function as shown by cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, and abnormal cardiac systolic function. PM2.5 induces inflammation through activation of PI3K/Akt/FOXO1 signaling pathways that contribute to cardiac hypertrophy and fibrogenesis [39]. Furthermore, the offspring from mice exposed to PM2.5 during gestation period develop cardiac hypertrophy that is associated with increased levels of acetyltransferase p300, acetylated H3K9 and cardiac transcriptional regulators Gata4 and Mef2c [40]. Therefore, prenatal, or postnatal exposure to environmental pollutant PM2.5 induces cardiac inflammation, cellular apoptosis, fibrogenesis and abnormal cardiac structure and function. 3.4. PM2.5-Induced Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Metabolic Syndrome, and Accelerated Aging

B in Drosophila whole body. Additionally, DCFH oxidation is significantly increased in whole body lysates from concentrated PM2.5-exposed flies compared to filtered air exposed flies indicating PM2.5 induces systemic oxidative stress. Exposure of Drosophila for 15 days to concentrated PM2.5 (6h/day, 5days/week, average concentration of PM2.5 (17µg and 24 µg.m^3/24h) also induces abnormal metabolism including deregulated insulin signaling and insulin resistance as evidenced by elevated levels of glucose and trehalose and increased expression of Ilp2 and Ilp5 transcripts in Drosophila [42]. Therefore, the results of this in vivo study confirmed the negative impact of PM2.5-induced inflammation and oxidative stress on organismal metabolism and longevity.

B in Drosophila whole body. Additionally, DCFH oxidation is significantly increased in whole body lysates from concentrated PM2.5-exposed flies compared to filtered air exposed flies indicating PM2.5 induces systemic oxidative stress. Exposure of Drosophila for 15 days to concentrated PM2.5 (6h/day, 5days/week, average concentration of PM2.5 (17µg and 24 µg.m^3/24h) also induces abnormal metabolism including deregulated insulin signaling and insulin resistance as evidenced by elevated levels of glucose and trehalose and increased expression of Ilp2 and Ilp5 transcripts in Drosophila [42]. Therefore, the results of this in vivo study confirmed the negative impact of PM2.5-induced inflammation and oxidative stress on organismal metabolism and longevity. 4. Efficacies of Natural and Synthetic Compounds in Alleviation of PM2.5-Induced Inflammation, Oxidative stress, and Diseases

4.1. Lessons from Studies Using Animal Models and Synthetic Compounds

, NF

, NF B2, TNFrsf11a, TNFrsf12a, pretreatment of mice with TM5614 (10 mg/kg/day) prevents induction of these inflammation mediators (Ghosh et al. unpublished data). After long-term exposure to PM2.5 (100 µg/mouse/week for 4 weeks), mice develop lung and heart vascular thrombosis. Most importantly, pretreatment with TM5614 significantly decreases PM2.5-induced vascular thrombosis in lungs and hearts [28]. Therefore, air pollutant PM2.5-induced inflammation, apoptosis and vascular thrombosis can be controlled by promising drug-like small molecule TM5614 targeting PAI-1, a pro-thrombotic and pro-aging factor. Future preclinical study using large animal cohort is required to proceed for clinical trials of this drug for treatment of air-pollutant-induced pathologies.

B2, TNFrsf11a, TNFrsf12a, pretreatment of mice with TM5614 (10 mg/kg/day) prevents induction of these inflammation mediators (Ghosh et al. unpublished data). After long-term exposure to PM2.5 (100 µg/mouse/week for 4 weeks), mice develop lung and heart vascular thrombosis. Most importantly, pretreatment with TM5614 significantly decreases PM2.5-induced vascular thrombosis in lungs and hearts [28]. Therefore, air pollutant PM2.5-induced inflammation, apoptosis and vascular thrombosis can be controlled by promising drug-like small molecule TM5614 targeting PAI-1, a pro-thrombotic and pro-aging factor. Future preclinical study using large animal cohort is required to proceed for clinical trials of this drug for treatment of air-pollutant-induced pathologies. , IL-6, and IL-1

, IL-6, and IL-1 , inflammasome Nlrp3 and apoptotic caspase pathway both in mouse and 16HBE cell (20 µg/ml/24h) models. Significantly, PM2.5 exposer-induced lung inflammation and pyroptosis are blocked by the pretreatment of mice with Nlrp3-specific inhibitor MCC950 (2.5 mg/kg) suggesting targeting Nlrp3 with small molecule inhibitor is a practical approach to control PM2.5-induced persistent inflammation and pyroptosis-driven lung pathologies [50]. Furthermore, exposure of 16HBE cells to PM2.5 (10-40 µg/ml) causes elevated IL-1

, inflammasome Nlrp3 and apoptotic caspase pathway both in mouse and 16HBE cell (20 µg/ml/24h) models. Significantly, PM2.5 exposer-induced lung inflammation and pyroptosis are blocked by the pretreatment of mice with Nlrp3-specific inhibitor MCC950 (2.5 mg/kg) suggesting targeting Nlrp3 with small molecule inhibitor is a practical approach to control PM2.5-induced persistent inflammation and pyroptosis-driven lung pathologies [50]. Furthermore, exposure of 16HBE cells to PM2.5 (10-40 µg/ml) causes elevated IL-1 expression, increased small GTPase Rac1 and increased inflammation. However, pretreatment of 16HBE for 30 min with Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 suppresses PM2.5-induced IL-1

expression, increased small GTPase Rac1 and increased inflammation. However, pretreatment of 16HBE for 30 min with Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 suppresses PM2.5-induced IL-1 secretion. This study also showed that pharmacological inhibition of Rac1 with NSC23766 (1mg/kg for 9 days; 30 min pretreatment before PM2.5 exposure) blocks PM2.5 (100 µg/every 3rd day for 9 days)-induced increased IL-1

secretion. This study also showed that pharmacological inhibition of Rac1 with NSC23766 (1mg/kg for 9 days; 30 min pretreatment before PM2.5 exposure) blocks PM2.5 (100 µg/every 3rd day for 9 days)-induced increased IL-1 secretion, infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages in murine lungs [51]. Therefore, Rac1 may be a druggable target for therapy of PM2.5-induced increased inflammation and associated lung diseases.

secretion, infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages in murine lungs [51]. Therefore, Rac1 may be a druggable target for therapy of PM2.5-induced increased inflammation and associated lung diseases. 4.2. Lessons from Studies Using Animal Models and Natural Compounds

, TNF-

, TNF- , KC, TGF-

, KC, TGF-

, TLR4, MyD88, TRAP6 and Nlrp3 in a dose-dependent manner and thus alleviates inflammation in the lung tissues. Importantly, treatment of PM2.5-exposed mice with SalB rescued PM2.5-induced suppression of antioxidant genes SOD, CAT, GSH and GSH-Px in mouse lungs [53]. These results clearly suggest SalB is highly effective in alleviation of PM2.5-induced inflammation, oxidative stress and thus abnormal lung structure and function.

, TLR4, MyD88, TRAP6 and Nlrp3 in a dose-dependent manner and thus alleviates inflammation in the lung tissues. Importantly, treatment of PM2.5-exposed mice with SalB rescued PM2.5-induced suppression of antioxidant genes SOD, CAT, GSH and GSH-Px in mouse lungs [53]. These results clearly suggest SalB is highly effective in alleviation of PM2.5-induced inflammation, oxidative stress and thus abnormal lung structure and function.  , IL-1

, IL-1 and oxidative stress through reversal of PM2.5-induced increased MDA and decreased GSH. Importantly, Sipeimine blocks PM2.5-induced inhibition of Nrf2, the primary regulator of antioxidant genes, and thus diminishes oxidative stress [54]. These results implicate the therapeutic potential of Sipeimine for the treatment of PM2.5-induced lung pathologies through inhibition of inflammation and oxidative stress. Additionally, pretreatment of Sprague-Dawley rats with Sipeimine (15 mg/kg-30 mg/kg) for 3 days cause significantly decreases PM2.5 (7.5mg/kg)-induced lung injury-related damage that is accompanied by reduced levels of inflammatory IL-1

and oxidative stress through reversal of PM2.5-induced increased MDA and decreased GSH. Importantly, Sipeimine blocks PM2.5-induced inhibition of Nrf2, the primary regulator of antioxidant genes, and thus diminishes oxidative stress [54]. These results implicate the therapeutic potential of Sipeimine for the treatment of PM2.5-induced lung pathologies through inhibition of inflammation and oxidative stress. Additionally, pretreatment of Sprague-Dawley rats with Sipeimine (15 mg/kg-30 mg/kg) for 3 days cause significantly decreases PM2.5 (7.5mg/kg)-induced lung injury-related damage that is accompanied by reduced levels of inflammatory IL-1 , IL-18, TNF-

, IL-18, TNF- , Nlrp3 and apoptotic caspase. Thus, Sipeimine effectively ameliorates PM2.5-induced inflammation, pyroptosis and lung injury. This has been further supported by the observation that the beneficial effect of Sipeimine is blocked by pretreatment with Nlrp3 activator nigericin [55]. Similarly, Astragaloside IV (AS-IV), a plant product from Astragalus Membranaceous with anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory properties, is highly effective in amelioration of PM2.5-induced massive lung pathologies in a rat model [56,57]. Pretreatment of rats with AS-IV (50-100 mg/kg/day/for 3 days) improved PM2.5 (7.5 mg/kg/day)-induced lung injury as shown by the decreased inflammatory signaling molecules IL-6, TNF-α, CRP, TLR4 and NF

, Nlrp3 and apoptotic caspase. Thus, Sipeimine effectively ameliorates PM2.5-induced inflammation, pyroptosis and lung injury. This has been further supported by the observation that the beneficial effect of Sipeimine is blocked by pretreatment with Nlrp3 activator nigericin [55]. Similarly, Astragaloside IV (AS-IV), a plant product from Astragalus Membranaceous with anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory properties, is highly effective in amelioration of PM2.5-induced massive lung pathologies in a rat model [56,57]. Pretreatment of rats with AS-IV (50-100 mg/kg/day/for 3 days) improved PM2.5 (7.5 mg/kg/day)-induced lung injury as shown by the decreased inflammatory signaling molecules IL-6, TNF-α, CRP, TLR4 and NF B pathways and oxidative stress in lungs [56,57]. Further, AS-IV inhibits PM2.5-induced PI3K/mTOR pathway and NF-kB translocation in NR8383 rat macrophages. In addition, AS-IV blocks PM2.5-induced suppression of antioxidant genes SOD and CAT [57]. Importantly, pretreatment of mice with AS-IV (50-100 mg/kg) also reduces PM2.5 (7.5 mg/kg/twice, 0, 24h followed by harvest at 36h)-induced inflammation, oxidative stress and pyroptosis through Nlrp3 pathway because pretreatment with Nlrp3 activator nigericin diminishes beneficial effect of AS-IV on PM2.5-induced lung pathologies [58]. Therefore, the bioactive herbal substance AS-IV has therapeutic potential in amelioration of PM2.5-induced inflammation and oxidative stress-driven lung pathologies. Thus, AS-IV may be a future potential drug to control PM2.5-induced lung injury and Nlrp3 is a potent druggable target for therapy.

B pathways and oxidative stress in lungs [56,57]. Further, AS-IV inhibits PM2.5-induced PI3K/mTOR pathway and NF-kB translocation in NR8383 rat macrophages. In addition, AS-IV blocks PM2.5-induced suppression of antioxidant genes SOD and CAT [57]. Importantly, pretreatment of mice with AS-IV (50-100 mg/kg) also reduces PM2.5 (7.5 mg/kg/twice, 0, 24h followed by harvest at 36h)-induced inflammation, oxidative stress and pyroptosis through Nlrp3 pathway because pretreatment with Nlrp3 activator nigericin diminishes beneficial effect of AS-IV on PM2.5-induced lung pathologies [58]. Therefore, the bioactive herbal substance AS-IV has therapeutic potential in amelioration of PM2.5-induced inflammation and oxidative stress-driven lung pathologies. Thus, AS-IV may be a future potential drug to control PM2.5-induced lung injury and Nlrp3 is a potent druggable target for therapy.

, IL-6, IL-12 and TNF-

, IL-6, IL-12 and TNF- and injury through downregulation of PM2.5-induced HIF-1

and injury through downregulation of PM2.5-induced HIF-1 and NF

and NF B signaling. In addition, pretreatment of human lung epithelial cells (A549) with TLS (25 µg/ml) reduces PM2.5 (30 µg, 100 µg, 300 µg/ml for 4 days)-induced apoptosis markers like cleaved caspase 3 and LDH activity, and inflammatory cytokines IL-1

B signaling. In addition, pretreatment of human lung epithelial cells (A549) with TLS (25 µg/ml) reduces PM2.5 (30 µg, 100 µg, 300 µg/ml for 4 days)-induced apoptosis markers like cleaved caspase 3 and LDH activity, and inflammatory cytokines IL-1 , IL-6, and TNF-α [59]. Collectively, these results indicate the therapeutic potential of TLS for the treatment of air pollution-induced lung inflammation and oxidative stress. The therapeutic efficacy of Deng-Shi-Qing-Mai-Tang (DSQMT), a Chinese herbal formula, on PM2.5-induced lung injury has been assessed [60]. Treatment with DSQMT (3 ml of 0.72, 1.45, 2.90 g/ml) significantly decreases the inflammatory cytokines IL-1

, IL-6, and TNF-α [59]. Collectively, these results indicate the therapeutic potential of TLS for the treatment of air pollution-induced lung inflammation and oxidative stress. The therapeutic efficacy of Deng-Shi-Qing-Mai-Tang (DSQMT), a Chinese herbal formula, on PM2.5-induced lung injury has been assessed [60]. Treatment with DSQMT (3 ml of 0.72, 1.45, 2.90 g/ml) significantly decreases the inflammatory cytokines IL-1 , IL-6, and TNF-

, IL-6, and TNF- and pathologies like damaged lung tissues and higher lung permeability index in rats exposed to PM2.5 (50 µg/rat/week for 8 weeks). Additionally, DSQMT (20% of medicated serum 1.45g/ml) decreases the PM2.5 (0.5mg/ml)-induced increased expression of many factors involved in inflammation including IL-1

and pathologies like damaged lung tissues and higher lung permeability index in rats exposed to PM2.5 (50 µg/rat/week for 8 weeks). Additionally, DSQMT (20% of medicated serum 1.45g/ml) decreases the PM2.5 (0.5mg/ml)-induced increased expression of many factors involved in inflammation including IL-1 , IL-6 and TNF-α in rat alveolar macrophages, NR8383 [60]. Thus, this study implicated DSQMT as a potential natural compound to control air pollution-induced lung injury through modulation of PM2.5-induced inflammatory responses. As Schisandrae Fructus fruit is known to possesses the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities, the therapeutic efficacy of Schisandrae Fructus ethanol extract (SF) (200 µg and 400 µg/ml pretreated for 1h) on PM2.5 (50 µg/ml for 24h)-induced inflammatory and oxidative stress developed in RAW264.7 macrophages and post fertilized (day3) zebrafish larvae has been evaluated [61]. Significantly, SF reduces the expression of PM2.5-induced inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-1

, IL-6 and TNF-α in rat alveolar macrophages, NR8383 [60]. Thus, this study implicated DSQMT as a potential natural compound to control air pollution-induced lung injury through modulation of PM2.5-induced inflammatory responses. As Schisandrae Fructus fruit is known to possesses the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities, the therapeutic efficacy of Schisandrae Fructus ethanol extract (SF) (200 µg and 400 µg/ml pretreated for 1h) on PM2.5 (50 µg/ml for 24h)-induced inflammatory and oxidative stress developed in RAW264.7 macrophages and post fertilized (day3) zebrafish larvae has been evaluated [61]. Significantly, SF reduces the expression of PM2.5-induced inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-1 , NO and COX2 through disruption of nuclear translocation of NF

, NO and COX2 through disruption of nuclear translocation of NF B from cytoplasm to nucleus and impaired NF

B from cytoplasm to nucleus and impaired NF B signaling. Pretreatment with SF also blocks PM2.5-induced ROS activity in macrophages and zebrafish larvae as shown by ROS fluorescence intensity [61]. Therefore, SF with anti-inflammatory as well as antioxidative properties is an excellent choice for the treatment of oxidative stress- and inflammation-induced tissue damages. Future in vivo studies are needed to explore the therapeutic efficacy of SF in amelioration of PM2.5-induced massive inflammation and oxidative stress in mammalian models.

B signaling. Pretreatment with SF also blocks PM2.5-induced ROS activity in macrophages and zebrafish larvae as shown by ROS fluorescence intensity [61]. Therefore, SF with anti-inflammatory as well as antioxidative properties is an excellent choice for the treatment of oxidative stress- and inflammation-induced tissue damages. Future in vivo studies are needed to explore the therapeutic efficacy of SF in amelioration of PM2.5-induced massive inflammation and oxidative stress in mammalian models. and reduction of Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 [62]. These results indicate that Bergapten is a potential natural therapeutic agent to treat CARAS and PM2.5-induced worst lung pathologies. Similarly, the efficacy of Rosavidin, a phenylpropanoid compound having multiple biological activities extracted from the Rhodiola crenulata plant, in amelioration of PM2.5-induced lung pathology has been examined in a rat model. Pretreatment of rats with Rosavidin (50-100 mg/kg/day for 3 days) diminishes PM2.5 (7.5mg/kg twice in 36h at 0h and 24h)-induced inflammation and ameliorates lung pathologies in rats through inhibition of inflammatory and apoptotic regulators including IL-1

and reduction of Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 [62]. These results indicate that Bergapten is a potential natural therapeutic agent to treat CARAS and PM2.5-induced worst lung pathologies. Similarly, the efficacy of Rosavidin, a phenylpropanoid compound having multiple biological activities extracted from the Rhodiola crenulata plant, in amelioration of PM2.5-induced lung pathology has been examined in a rat model. Pretreatment of rats with Rosavidin (50-100 mg/kg/day for 3 days) diminishes PM2.5 (7.5mg/kg twice in 36h at 0h and 24h)-induced inflammation and ameliorates lung pathologies in rats through inhibition of inflammatory and apoptotic regulators including IL-1 , Nlrp3 inflammasome, and caspase. This study further demonstrated that Nlrp3 specific activator nigerin blunts Rosavidin-mediated amelioration of PM2.5-induced lung pathologies [63].Therefore, Rosavidin has potential to be a remedy to controlling PM2.5-induced inflammation and pyroptosis-driven lung pathologies. It is well documented that exposure to PM2.5 causes worst lung pathologies in COPD patients [64,65]. Bufei Yishen formula (ECC-BYF), a Chinese herbal medicinal formula, efficiently improves COPD in a rat model that was developed by repeated cigarette smoke inhalation (2 times daily, 30 min each time for 8 weeks and intranasal instillation of pneumonia bacteria once for every 5 days). Whole body exposure of COPD rats to PM2.5 for another 8 weeks (average daily conc. of PM2.5 739.97µg/m^3; 4h/day for 8 weeks) leads to excessive lung inflammation, lung tissue remodeling and decreased lung function in this rat model of COPD. However, PM2.5 failed to induce inflammation, oxidative stress, pyroptosis and excessive collagen deposition in the lungs of ECC-BYF-treated COPD rat model [66]. These results clearly indicate the therapeutic efficacy of ECC-BYF for the treatment of PM2.5-induced worst lung inflammation, pyroptosis and lung injury in COPD in a preclinical setting.

, Nlrp3 inflammasome, and caspase. This study further demonstrated that Nlrp3 specific activator nigerin blunts Rosavidin-mediated amelioration of PM2.5-induced lung pathologies [63].Therefore, Rosavidin has potential to be a remedy to controlling PM2.5-induced inflammation and pyroptosis-driven lung pathologies. It is well documented that exposure to PM2.5 causes worst lung pathologies in COPD patients [64,65]. Bufei Yishen formula (ECC-BYF), a Chinese herbal medicinal formula, efficiently improves COPD in a rat model that was developed by repeated cigarette smoke inhalation (2 times daily, 30 min each time for 8 weeks and intranasal instillation of pneumonia bacteria once for every 5 days). Whole body exposure of COPD rats to PM2.5 for another 8 weeks (average daily conc. of PM2.5 739.97µg/m^3; 4h/day for 8 weeks) leads to excessive lung inflammation, lung tissue remodeling and decreased lung function in this rat model of COPD. However, PM2.5 failed to induce inflammation, oxidative stress, pyroptosis and excessive collagen deposition in the lungs of ECC-BYF-treated COPD rat model [66]. These results clearly indicate the therapeutic efficacy of ECC-BYF for the treatment of PM2.5-induced worst lung inflammation, pyroptosis and lung injury in COPD in a preclinical setting.  , IL-6, TNF-

, IL-6, TNF- , and liver injury as shown by higher ALT and AST compared to wildtype mice. These in vivo observations on the beneficial effects of Juglanin on PM2.5-induced liver injury have also been replicated in vitro using human liver cell line LO2 [67]. Together, this study suggests the significant involvement of Nrf2 and SIKE pathways in PM2.5-induced liver injury and most importantly, Juglanin is a potential therapeutic agent to controlling PM2.5-induced inflammation, oxidative stress, and liver pathologies. A recent study also showed that Nrf2 protects PM2.5 (20mg/kg)-induced lung injury through its regulation of iron-dependent cellular death or ferroptosis. This is supported by the observation that ferroptosis and lung injury in response to PM2.5 are more severe in Nrf2-deficient lung tissue and cellular model [68]. Similarly, Tectoridin (50-100 mg/kg), a bioactive molecule, also ameliorates PM2.5 (20mg/kg for 7 days)-induced lung injury as revealed by decreased morphological damage, necrosis, edema and inflammation with decreased IL-6 and TNF-

, and liver injury as shown by higher ALT and AST compared to wildtype mice. These in vivo observations on the beneficial effects of Juglanin on PM2.5-induced liver injury have also been replicated in vitro using human liver cell line LO2 [67]. Together, this study suggests the significant involvement of Nrf2 and SIKE pathways in PM2.5-induced liver injury and most importantly, Juglanin is a potential therapeutic agent to controlling PM2.5-induced inflammation, oxidative stress, and liver pathologies. A recent study also showed that Nrf2 protects PM2.5 (20mg/kg)-induced lung injury through its regulation of iron-dependent cellular death or ferroptosis. This is supported by the observation that ferroptosis and lung injury in response to PM2.5 are more severe in Nrf2-deficient lung tissue and cellular model [68]. Similarly, Tectoridin (50-100 mg/kg), a bioactive molecule, also ameliorates PM2.5 (20mg/kg for 7 days)-induced lung injury as revealed by decreased morphological damage, necrosis, edema and inflammation with decreased IL-6 and TNF- through stimulation of antioxidant gene regulator Nrf2 and antioxidant genes like GSH and GPX4. Similarly, pretreatment of BEAS-2B cells with Tectoridin (25, 50 and 100 uM for 1 h) reduces PM2.5 (400µg/ml for 24h)-induced ROS generation through activation of Nrf2, GSH and inhibition of PM2.5-induced inflammatory MDA [68]. These results suggest that Tectoridin has potential to controlling PM2.5-induced oxidative stress, ferroptosis, and lung pathologies. It is known that exercise-induced myokine, Irisin, a polypeptide derived from muscle and adipose tissues, is a potent anti-inflammatory agent that diminishes metabolic syndrome [69]. Interestingly, pretreatment of mice with recombinant Irisin (250 µg/kg) significantly diminishes the PM2.5 (8mg/kg for 24h)-induced increased level of inflammatory cytokines IL-1

through stimulation of antioxidant gene regulator Nrf2 and antioxidant genes like GSH and GPX4. Similarly, pretreatment of BEAS-2B cells with Tectoridin (25, 50 and 100 uM for 1 h) reduces PM2.5 (400µg/ml for 24h)-induced ROS generation through activation of Nrf2, GSH and inhibition of PM2.5-induced inflammatory MDA [68]. These results suggest that Tectoridin has potential to controlling PM2.5-induced oxidative stress, ferroptosis, and lung pathologies. It is known that exercise-induced myokine, Irisin, a polypeptide derived from muscle and adipose tissues, is a potent anti-inflammatory agent that diminishes metabolic syndrome [69]. Interestingly, pretreatment of mice with recombinant Irisin (250 µg/kg) significantly diminishes the PM2.5 (8mg/kg for 24h)-induced increased level of inflammatory cytokines IL-1 , IL-18, TNF-

, IL-18, TNF- and mediators of inflammation including NF

and mediators of inflammation including NF B, and Nlrp3 inflammasome [70]. Therefore, Irisin is an effective myokine in amelioration of PM2.5-induced lung pathologies through suppression of inflammatory pathways.

B, and Nlrp3 inflammasome [70]. Therefore, Irisin is an effective myokine in amelioration of PM2.5-induced lung pathologies through suppression of inflammatory pathways. 4.3. Lessons from Studies Using Cellular Models and Synthetic Compounds

and IL-18 in this cell line, indicating PM2.5 exposure contributes to endothelial dysfunction. Importantly, pretreatment of EAhy.926 cells with NOX1/4 inhibitor (GSK 13783) (5uM) diminishes PM2.5-induced oxidative stress and inflammation and thus ameliorates PM2.5-induced endothelial dysfunction [71]. Hence, NOX1/4 may be a druggable target to reduce air pollutant PM2.5-induced endothelial dysfunction and associated cardiovascular diseases. The pharmacological effect of Ropivacaine, a widely used local anesthetic, on PM2.5-induced acute lung injury has been explored in cultured lung cells [72]. Exposure to PM2.5 (100µg/ml) induces the inflammatory and oxidative stress in lung cells BEAS-2B as shown by increased expression of inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8, IL-1

and IL-18 in this cell line, indicating PM2.5 exposure contributes to endothelial dysfunction. Importantly, pretreatment of EAhy.926 cells with NOX1/4 inhibitor (GSK 13783) (5uM) diminishes PM2.5-induced oxidative stress and inflammation and thus ameliorates PM2.5-induced endothelial dysfunction [71]. Hence, NOX1/4 may be a druggable target to reduce air pollutant PM2.5-induced endothelial dysfunction and associated cardiovascular diseases. The pharmacological effect of Ropivacaine, a widely used local anesthetic, on PM2.5-induced acute lung injury has been explored in cultured lung cells [72]. Exposure to PM2.5 (100µg/ml) induces the inflammatory and oxidative stress in lung cells BEAS-2B as shown by increased expression of inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8, IL-1 , TNF-

, TNF- and oxidative stress-related MDA, and decreased expression of GSH. However, pretreatment of BEAS-2B cells with Ropivacaine (1 µM, 10 µM, 100 µM) reduces PM2.5-induced inflammatory pathway, oxidative stress, and cell death through downregulation of inflammasome Nlrp3 and apoptotic caspase pathways [72], indicating Ropivacaine has potential to reduce PM2.5-induced inflammation, oxidative stress, and thus may be effective in diminishing lung injury-associated pathologies. Similarly, pretreatment of human bronchial epithelial cells (16HBE) with Caspase inhibitors Z-VAD-FMK and VX-765 block wood smoke-derived PM2.5 (5, 10. 20 µg/ml)-induced inflammation and pyroptosis of 16HBE cells as evidenced by decreased levels of LDH activity, caspase, inflammatory cytokines IL-1

and oxidative stress-related MDA, and decreased expression of GSH. However, pretreatment of BEAS-2B cells with Ropivacaine (1 µM, 10 µM, 100 µM) reduces PM2.5-induced inflammatory pathway, oxidative stress, and cell death through downregulation of inflammasome Nlrp3 and apoptotic caspase pathways [72], indicating Ropivacaine has potential to reduce PM2.5-induced inflammation, oxidative stress, and thus may be effective in diminishing lung injury-associated pathologies. Similarly, pretreatment of human bronchial epithelial cells (16HBE) with Caspase inhibitors Z-VAD-FMK and VX-765 block wood smoke-derived PM2.5 (5, 10. 20 µg/ml)-induced inflammation and pyroptosis of 16HBE cells as evidenced by decreased levels of LDH activity, caspase, inflammatory cytokines IL-1 and IL-18, the downstream targets of Nlrp3 [19]. These results show the potential of caspase inhibitors to block wildfire/wood smoke-induced massive inflammation and pyroptosis.

and IL-18, the downstream targets of Nlrp3 [19]. These results show the potential of caspase inhibitors to block wildfire/wood smoke-induced massive inflammation and pyroptosis. B and Nlrp3 inflammasome. However, pretreatment of 16HBE with VitD3 (1nM) for 24h decreases the PM2.5-induced ROS generation, and expression of MDA, IL-6, IL-8, NF

B and Nlrp3 inflammasome. However, pretreatment of 16HBE with VitD3 (1nM) for 24h decreases the PM2.5-induced ROS generation, and expression of MDA, IL-6, IL-8, NF B and Nlrp3. indicating VitD3 is effective in inhibition of PM2.5-induced inflammatory and oxidative stress responses [73]. Similarly, pretreatment of rat neonatal cardiomyocytes with VitD3 (10^-8 mol/L) significantly reduce the cooking oil fumes-derived PM2.5 (50 µg/ml)-induced ROS production, inflammation and pyroptosis through suppression of inflammatory signaling pathways JAK/Stat1 and NF

B and Nlrp3. indicating VitD3 is effective in inhibition of PM2.5-induced inflammatory and oxidative stress responses [73]. Similarly, pretreatment of rat neonatal cardiomyocytes with VitD3 (10^-8 mol/L) significantly reduce the cooking oil fumes-derived PM2.5 (50 µg/ml)-induced ROS production, inflammation and pyroptosis through suppression of inflammatory signaling pathways JAK/Stat1 and NF B. Further, VitD3 also prevents PM2.5-induced inhibition of antioxidant SOD and GSH in cardiomyocytes [74]. Collectively, these results indicate that VitD3 is cardioprotective from PM2.5-induced inflammation, oxidative stress, and associated pathologies. Another study [75] showed that while the expression levels of inflammatory TLR4, NF

B. Further, VitD3 also prevents PM2.5-induced inhibition of antioxidant SOD and GSH in cardiomyocytes [74]. Collectively, these results indicate that VitD3 is cardioprotective from PM2.5-induced inflammation, oxidative stress, and associated pathologies. Another study [75] showed that while the expression levels of inflammatory TLR4, NF B and COX2 are significantly increased in PM2.5 (250 µg/ml for 24-72 h)-treated RAW254.7 macrophages, pretreatment with TLR4-inhibitor TAK242 (5-20 µM) significantly inhibits PM2.5-induced pro-inflammatory signaling molecules IL-6, MCP1 and TNF-

B and COX2 are significantly increased in PM2.5 (250 µg/ml for 24-72 h)-treated RAW254.7 macrophages, pretreatment with TLR4-inhibitor TAK242 (5-20 µM) significantly inhibits PM2.5-induced pro-inflammatory signaling molecules IL-6, MCP1 and TNF- [75]. Therefore, TLR4-specific inhibitor has potential to controlling PM2.5-induced inflammation. Similarly, the levels of inflammatory markers IL-1

[75]. Therefore, TLR4-specific inhibitor has potential to controlling PM2.5-induced inflammation. Similarly, the levels of inflammatory markers IL-1 , COX2 and oxidative stress marker Hmox1 are also significantly elevated in PM2.5-exposed (30 µg/ml for 3h) mouse macrophages. While PM2.5-induced inflammatory responses are decreased in macrophages either by pretreatment with endotoxin neutralizer polymyxin B (0.5mg/ml) or NF-kB inhibitor Bay 11-7085 (10 µM), the oxidative stress responses are decreased by antioxidant n-acetyl cysteine (NAC) (10mM) [76]. Collectively, the results of these in vitro studies provide clear evidence that PM2.5-induced inflammation and oxidative stress pathways can be effectively blocked by different synthetic compounds.

, COX2 and oxidative stress marker Hmox1 are also significantly elevated in PM2.5-exposed (30 µg/ml for 3h) mouse macrophages. While PM2.5-induced inflammatory responses are decreased in macrophages either by pretreatment with endotoxin neutralizer polymyxin B (0.5mg/ml) or NF-kB inhibitor Bay 11-7085 (10 µM), the oxidative stress responses are decreased by antioxidant n-acetyl cysteine (NAC) (10mM) [76]. Collectively, the results of these in vitro studies provide clear evidence that PM2.5-induced inflammation and oxidative stress pathways can be effectively blocked by different synthetic compounds.4.4. Lessons from Studies Using Cellular Models and Natural Compounds

, IL-6, TNF-

, IL-6, TNF- , TLR2/4, and COX2 and stress-induced protein HO-1 in BV-2 microglial cells. Most importantly, PM2.5 (50 µg/ml/24h) failed to induce the inflammatory markers in rat glial cells pretreated with Astaxanthin (1, 10 µg/ml) for 4 h. Astaxanthin also prevents PM2.5-induced inhibition of IL-10 and Arg-1. Hence, Astaxanthin is effective in prevention of PM2.5-induced inflammation, oxidative stress and associated neurological disorders [79]. The plant product Ophiopogonin D is also an anti-inflammatory agent. Pretreatment of mouse lung epithelial cells MLE-12 with Ophiopogonin D (10-80 µM) for 1h inhibits PM2.5 (15 µg/cm^2 for 24h)-induced inflammation as shown by the decreased levels of IL-1

, TLR2/4, and COX2 and stress-induced protein HO-1 in BV-2 microglial cells. Most importantly, PM2.5 (50 µg/ml/24h) failed to induce the inflammatory markers in rat glial cells pretreated with Astaxanthin (1, 10 µg/ml) for 4 h. Astaxanthin also prevents PM2.5-induced inhibition of IL-10 and Arg-1. Hence, Astaxanthin is effective in prevention of PM2.5-induced inflammation, oxidative stress and associated neurological disorders [79]. The plant product Ophiopogonin D is also an anti-inflammatory agent. Pretreatment of mouse lung epithelial cells MLE-12 with Ophiopogonin D (10-80 µM) for 1h inhibits PM2.5 (15 µg/cm^2 for 24h)-induced inflammation as shown by the decreased levels of IL-1 , IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-

, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF- . The Ophiopogonin D exerts its anti-inflammatory effect through downregulation of NF

. The Ophiopogonin D exerts its anti-inflammatory effect through downregulation of NF B signaling and activation of AMPK activity as pretreatment of cells with AMPK inhibitor (Compound C, 10 µM) blocks anti-inflammatory activity of Ophiopogonin D [80]. As the dihydrophenanthrene Coelonin, derived from the flowering plant Bletilla striata, is a known anti-inflammatory agent [81,82], its therapeutic efficacy in amelioration of PM2.5-induced inflammation has been evaluated [83]. Pretreatment with Coelonin (1.25, 2.5 or 5 µg/ml for 2h) ameliorates PM2.5 (200µ/ml for 18h)-induced inflammation, oxidative stress and pyroptosis of RAW264 and 1774A.1 macrophages through suppression of Nlrp3 inflammasome, IL-6, TNF-

B signaling and activation of AMPK activity as pretreatment of cells with AMPK inhibitor (Compound C, 10 µM) blocks anti-inflammatory activity of Ophiopogonin D [80]. As the dihydrophenanthrene Coelonin, derived from the flowering plant Bletilla striata, is a known anti-inflammatory agent [81,82], its therapeutic efficacy in amelioration of PM2.5-induced inflammation has been evaluated [83]. Pretreatment with Coelonin (1.25, 2.5 or 5 µg/ml for 2h) ameliorates PM2.5 (200µ/ml for 18h)-induced inflammation, oxidative stress and pyroptosis of RAW264 and 1774A.1 macrophages through suppression of Nlrp3 inflammasome, IL-6, TNF- , TLR4, COX2, and NFkB signaling [83]. These results suggest that different natural compounds are effective in diminishing PM2.5-induced massive inflammation, oxidative stress, and pyroptosis.

, TLR4, COX2, and NFkB signaling [83]. These results suggest that different natural compounds are effective in diminishing PM2.5-induced massive inflammation, oxidative stress, and pyroptosis.5. Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Orru, H.; Ebi, K.L.; Forsberg, B. The Interplay of Climate Change and Air Pollution on Health. Curr.Environ. Health. Rep. 2017, 4, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steven, S.; Frenis, K.; Oelze, M.; Kalinovic, S.; Kuntic, M.; Bayo Jimenez, M.T.; Vujacic-Mirski, K.; Helmstädter, J.; Kröller-Schön, S.; Münzel, T.; et al. Vascular Inflammation and Oxidative Stress: Major Triggers for Cardiovascular Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 7092151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutheil, F.; Comptour, A.; Morlon, R.; Mermillod, M.; Pereira, B.; Baker, J.S.; Charkhabi, M.; Clinchamps, M.; Bourdel, N. Autism spectrum disorder and air pollution: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 278, 116856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S.; Pope, C.A., 3rd; Brook, J.R.; Bhatnagar, A.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Holguin, F.; Hong, Y.; Luepker, R.V.; Mittleman, M.A.; et al. American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010, 121, 2331–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grande, G.; Ljungman, P.L.S.; Eneroth, K.; Bellander, T.; Rizzuto, D. Association Between Cardiovascular Disease and Long-term Exposure to Air Pollution With the Risk of Dementia. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simkhovich, B.Z.; Kleinman, M.T.; Kloner, R.A. Particulate air pollution and coronary heart disease. Curr. opin. cardiol. 2009, 24, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchini, M.; Mannucci, P.M. Thrombogenicity and cardiovascular effects of ambient air pollution. Blood. 2011, 118, 2405–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Xu, X.; Chu, M.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J. Air particulate matter and cardiovascular disease: the epidemiological, biomedical, and clinical evidence. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, E8–E19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, D.S.; Cox, B.; Janssen, B.G.; Clemente, D.B.P.; Gasparrini, A.; Vanpoucke, C.; Lefebvre, W.; Roels, H.A.; Plusquin, M.; Nawrot, T.S. Prenatal Air Pollution and Newborns' Predisposition to Accelerated Biological Aging. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 1160–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Li, G.; Kong, L.; Jing, H.; Zhang, N.; Ning, J.; Gao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. PM2.5 induce lifespan reduction, insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway disruption and lipid metabolism disorder in Caenorhabditis elegans. Front. Public. Health. 2023, 11, 1055175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Pandey, P. Air Pollution, Climate Change, and Human Health in Indian Cities: A Brief Review. Front. Sustain. Cities, 2021, 3,705131.

- Wu, C.L.; Wang, H.W.; Cai, W.J.; He, H.D.; Ni, A.N.; Peng, Z.R. Impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on roadside traffic-related air pollution in Shanghai, China. Build. Environ. 2021, 194, 107718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marwah, M.; Agrawala, P.K. COVID-19 lockdown and environmental pollution: an Indian multi-state investigation. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariussen, E.; Fjellsbø, L.; Frømyr, T.R.; Johnsen, I.V.; Karsrud, T.E.; Voie, Ø.A. Toxic effects of gunshot fumes from different ammunitions for small arms on lung cells exposed at the air liquid interface. Toxicol. In Vitro. 2021, 72, 105095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Vance, S.A.; Aurell, J.; Holder, A.L.; Pancras, J.P.; Gullett, B.; Gavett, S.H.; McNesby, K.L.; Gilmour, M.I. Chemistry and lung toxicity of particulate matter emitted from firearms. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.Y.; Tong, L.; Shen, D.; Yu, J.E.; Hu, Z.Q.; Li, Y.J.; Zhang, L.J.; Xue, E.F.; Tang, H.F. Airborne Bacteria Enriched PM2.5 Enhances the Inflammation in an Allergic Adolescent Mouse Model Induced by Ovalbumin. Inflammation. 2020, 43, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krall, J.R.; Mulholland, J.A.; Russell, A.G.; Balachandran, S.; Winquist, A.; Tolbert, P.E.; Waller, L.A.; Sarnat, S.E. Associations between Source-Specific Fine Particulate Matter and Emergency Department Visits for Respiratory Disease in Four U.S. Cities. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, F.; Sancini, G.; Mantecca, P.; Gallinotti, D.; Camatini, M.; Palestini, P. The acute toxic effects of particulate matter in mouse lung are related to size and season of collection. Toxicol. Lett. 2011, 202, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.; Hong, W.; Li, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, W.; Dai, J.; Deng, X.; Zhou, H.; Li, B.; Ran, P. Wood smoke particulate matter (WSPM2.5) induces pyroptosis through both Caspase-1/IL-1β/IL-18 and ATP/P2Y-dependent mechanisms in human bronchial epithelial cells. Chemosphere. 2022, 307, 135726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merk, R.; Heßelbach, K.; Osipova, A.; Popadić, D.; Schmidt-Heck, W.; Kim, G.J.; Günther, S.; Piñeres, A.G.; Merfort, I.; Humar, M. Particulate Matter (PM2.5) from Biomass Combustion Induces an Anti-Oxidative Response and Cancer Drug Resistance in Human Bronchial Epithelial BEAS-2B Cells. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020, 17, 8193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemmar, A.; Vanbilloen, H.; Hoylaerts, M.F.; Hoet, P.H.; Verbruggen, A.; Nemery, B. Passage of intratracheally instilled ultrafine particles from the lung into the systemic circulation in hamster. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2001, 164, 1665–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.; Miller, M.R. Ambient air pollution and thrombosis. Part. Fibre. Toxicol. 2018, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Pan, B.; Liu, L.; Zhao, W.; Zhu, J.; Huang, X.; Tian, J. In utero exposure to PM2.5 during gestation caused adult cardiac hypertrophy through histone acetylation modification. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 4375–4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelin, T.D.; Joseph, A.M.; Gorr, M.W.; Wold, L.E. Direct and indirect effects of particulate matter on the cardiovascular system. Toxicol. Lett. 2012, 208, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Duan, F.; Qin, M.; Wu, F.; Sheng, W.; Yang, L.; Liu, J.; He, K. Transcriptomic Analyses of the Biological Effects of Airborne PM2.5 Exposure on Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0138267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.; Park, S.A.; Park, I.; Kim, P.; Cho, N.H.; Hyun, J.W.; Hyun, Y.M. PM2.5 Exposure in the Respiratory System Induces Distinct Inflammatory Signaling in the Lung and the Liver of Mice. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 3486841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Pu, W.; Niu, M.; Wazir, J.; Song, S.; Wei, L.; Li, L.; Su, Z.; Wang, H. Respiratory exposure to PM2.5 soluble extract induced chronic lung injury by disturbing the phagocytosis function of macrophage. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 13983–13997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Soberanes, S.; Lux, E.; Shang, M.; Aillon, R.P.; Eren, M.; Budinger, G.R.S.; Miyata, T.; Vaughan, D.E. Pharmacological inhibition of PAI-1 alleviates cardiopulmonary pathologies induced by exposure to air pollutants PM2.5. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piao, C.H.; Fan, Y.; Nguyen, T.V.; Shin, H.S.; Kim, H.T.; Song, C.H.; Chai, O.H. PM2.5 Exacerbates Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Response through the Nrf2/NF-κB Signaling Pathway in OVA-Induced Allergic Rhinitis Mouse Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piao, C.H.; Fan, Y.; Nguyen, T.V.; Song, C.H.; Kim, H.T.; Chai, O.H. PM2.5 exposure regulates Th1/Th2/Th17 cytokine production through NF-κB signaling in combined allergic rhinitis and asthma syndrome. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 119, 110254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Ichinose, T.; Yoshida, Y.; Arashidani, K.; Yoshida, S.; Takano, H.; Sun, G.; Shibamoto, T. Urban PM2.5 exacerbates allergic inflammation in the murine lung via a TLR2/TLR4/MyD88-signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 11027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cui, Y.; Liu, H.; Wu, J.; Li, J.; Liu, X. PM2.5 aggravates airway inflammation in asthmatic mice: activating NF-κB via MyD88 signaling pathway. Int J Environ Health Res. 2023, 33, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, L.H.; Li, T.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y.N.; Wang, S.P.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Zhang, G.Q.; Duan, J. IL-17A-producing T cells exacerbate fine particulate matter-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR-mediated autophagy. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 8532–8544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Zhuang, Y. PM2.5 induces autophagy-mediated cell apoptosis via PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in mice bronchial epithelium cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Chen, X.; He, S.; Li, N.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J. Exposure interval to ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) collected in Southwest China induced pulmonary damage through the Janus tyrosine protein kinase-2/signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 signaling pathway both in vivo and in vitro. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2021, 41, 2042–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, C.; Yang, H.; Cui, L.; Cao, X.; Huang, H.; Chen, T. Potential hazardous effects of printing room PM2.5 exposure include promotion of lung inflammation and subsequent injury. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 3213–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wang, N.; Duan, S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, W.; Feng, F. Association of EGF Receptor and NLRs signaling with Cardiac Inflammation and Fibrosis in Mice Exposed to Fine Particulate Matter. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2016, 30, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, L.Z.; Sun, H.; Chen, J.H. Histone deacetylases 3 deletion restrains PM2.5-induced mice lung injury by regulating NF-κB and TGF-β/Smad2/3 signaling pathways. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 85, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Tian, J.; Li, B.; Zhou, L.; Kang, H.; Pei, Z.; Zhang, M.; Li, C.; Wu, M.; Wang, Q.; et al. Ambient PM2.5 caused cardiac dysfunction through FoxO1-targeted cardiac hypertrophy and macrophage-activated fibrosis in mice. Chemosphere. 2020, 247, 125881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Pan, B.; Liu, L.; Zhao, W.; Zhu, J.; Huang, X.; Tian, J. In utero exposure to PM2.5 during gestation caused adult cardiac hypertrophy through histone acetylation modification. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 4375–4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.X.; Zhu, Y.F.; Chang, H.F.; Liang, Y. Nanoceria restrains PM2.5-induced metabolic disorder and hypothalamus inflammation by inhibition of astrocytes activation related NF-κB pathway in Nrf2 deficient mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 99, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, M.; Zhong, M.; Hu, Z.; Qiu, L.; Rajagopalan, S.; Fossett, N.G.; Chen, L.C.; Ying, Z. Exposure to Concentrated Ambient PM2.5 Shortens Lifespan and Induces Inflammation-Associated Signaling and Oxidative Stress in Drosophila. Toxicol Sci. 2017, 156, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, D.E.; Rai, R.; Khan, S.S.; Eren, M.; Ghosh, A.K. Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 Is a Marker and a Mediator of Senescence. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 1446–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Bradham, W.S.; Gleaves, L.A.; De Taeye, B.; Murphy, S.B.; Covington, J.W.; Vaughan, D.E. Genetic deficiency of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 promotes cardiac fibrosis in aged mice: involvement of constitutive transforming growth factor-beta signaling and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Circulation. 2010, 122, 1200–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Vaughan, D.E. PAI-1 in tissue fibrosis. J Cell Physiol. 2012, 227, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, S.; Ganguly, K.; Stoeger, T.; Semmler-Bhenke, M.; Takenaka, S.; Kreyling, W.G.; Pitz, M.; Reitmeir, P.; Peters, A.; Eickelberg, O.; et al. Cardiovascular and inflammatory effects of intratracheally instilled ambient dust from Augsburg, Germany, in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs). Part. Fibre. Toxicol. 2010, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budinger, G.R.; McKell, J.L.; Urich, D.; Foiles, N.; Weiss, I.; Chiarella, S.E.; Gonzalez, A.; Soberanes, S.; Ghio, A.J.; Nigdelioglu, R.; et al. Particulate matter-induced lung inflammation increases systemic levels of PAI-1 and activates coagulation through distinct mechanisms. PLoS One. 2011, 6, e18525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Rai, R.; Park, K.E.; Eren, M.; Miyata, T.; Wilsbacher, L.D.; Vaughan, D.E. A small molecule inhibitor of PAI-1 protects against doxorubicin-induced cellular senescence. Oncotarget. 2016, 7, 72443–72457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Kalousdian, A.A.; Shang, M.; Lux, E.; Eren, M.; Keating, A.; Wilsbacher, L.D.; Vaughan, D.E. Cardiomyocyte PAI-1 influences the cardiac transcriptome and limits the extent of cardiac fibrosis in response to left ventricular pressure overload. Cell. Signal. 2023, 104, 110555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.; Liu, Y.; Guo, D.; He, W.; Zhao, L.; Xia, S. PM2.5-induced pulmonary inflammation via activation of the NLRP3/caspase-1 signaling pathway. Environ. Toxicol. 2021, 36, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Zeng, X.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Z.; Dong, X.; Jia, Y.; Shen, J.; Chen, R.; Lin, X. Inhibition of Rac1 activity alleviates PM2.5-induced pulmonary inflammation via the AKT signaling pathway. Toxicol. Lett. 2019, 310, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Liu, W.; Mu, Y.P.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.N.; Zhao, C.Q.; Chen, J.M.; Liu, P. Pharmacological Effects of Salvianolic Acid B Against Oxidative Damage. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 572373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Y.; Li, L.; Kan, L.; Xie, Q. Inhalation of Salvianolic Acid B Prevents Fine Particulate Matter-Induced Acute Airway Inflammation and Oxidative Stress by Downregulating the LTR4/MyD88/ NLRP3 Pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 5044356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Zhao, S.; Huang, D.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Pei, C.; Shi, S.; Jia, N.; He, Y.; et al. Sipeimine ameliorates PM2.5-induced lung injury by inhibiting ferroptosis via the PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 pathway: A network pharmacology approach. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 239, 113615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Shen, Z.; Zhao, S.; Pei, C.; Jia, N.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Shi, S.; He, Y.; et al. Sipeimine attenuates PM2.5-induced lung toxicity via suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis through activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2023, 376, 110448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Xiao, W.; Pei, C.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Huang, D.; Wang, F.; Wang, Z. Astragaloside IV alleviates PM2.5-induced lung injury in rats by modulating TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signalling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 91, 107290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, C.; Wang, F.; Huang, D.; Shi, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z. Astragaloside IV Protects from PM2.5-Induced Lung Injury by Regulating Autophagy via Inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling in vivo and in vitro. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 4707–4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Shi, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Shen, Z.; Wang, M.; Pei, C.; Wu, Y.; He, Y.; Wang, Z. Astragaloside IV alleviates PM2.5-caused lung toxicity by inhibiting inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis via NLRP3/caspase-1 axis inhibition in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 150, 112978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Chen, M.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jin, F. Tussilagone protects acute lung injury from PM2.5 via alleviating Hif-1α/NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response. Environ. Toxicol. 2022, 37, 1198–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, J.; Jiang, C.; Chen, J.; Feng, X.; Chen, W.; Zhang, J.; Dong, H.; Zhang, W. A traditional herbal formula, Deng-Shi-Qing-Mai-Tang, regulates TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway to reduce inflammatory response in PM2.5-induced lung injury. Phytomedicine. 2021, 91, 153665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Park, C.; Kwon, D.H.; Hwangbo, H.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, M.Y.; Ji, S.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Jeong, J.W.; Kim, G.Y.; et al. Schisandrae Fructus ethanol extract attenuates particulate matter 2.5-induced inflammatory and oxidative responses by blocking the activation of the ROS-dependent NF-κB signaling pathway. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2021, 15, 686–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Nguyen, T.V.; Jin, J.; Yu, Z.N.; Song, C.H.; Chai, O.H. Bergapten ameliorates combined allergic rhinitis and asthma syndrome after PM2.5 exposure by balancing Treg/Th17 expression and suppressing STAT3 and MAPK activation in a mouse model. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 164, 114959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Jia, N.; Pei, C.; Shen, Z.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Shi, S.; Li, S.; Wang, Z. Rosavidin protects against PM2.5-induced lung toxicity via inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 213, 115623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Lin, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Yu, H.; Huang, Y.; Yang, J.; Cai, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; et al. PM2.5 induces pulmonary microvascular injury in COPD via METTL16-mediated m6A modification. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 303, 119115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Dong, T.; Yan, K.; Ci, X.; Peng, L. PM2.5 increases susceptibility to acute exacerbation of COPD via NOX4/Nrf2 redox imbalance-mediated mitophagy. Redox Biol. 2023, 59, 102587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhao, P.; Tian, Y.; Liu, X.; He, H.; Jia, R. Effective-component compatibility of Bufei Yishen formula protects COPD rats against PM2.5-induced oxidative stress via miR-155/FOXO3a pathway. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021, 228, 112918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, C.; Tan, J.; Zhong, S.; Lai, L.; Chen, G.; Zhao, J.; Yi, C.; Wang, L.; Zhou, L.; Tang, T.; et al. Nrf2 mitigates prolonged PM2.5 exposure-triggered liver inflammation by positively regulating SIKE activity: Protection by Juglanin. Redox Biol. 2020, 36, 101645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Fan, X.; Zheng, N.; Yan, K.; Hou, T.; Peng, L.; Ci, X. Activation of Nrf2 signalling pathway by tectoridin protects against ferroptosis in particulate matter-induced lung injury. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 180, 2532–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slate-Romano, J.J.; Yano, N.; Zhao, T.C. Irisin reduces inflammatory signaling pathways in inflammation-mediated metabolic syndrome. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2022, 552, 111676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, R.; Han, Z.; Ma, J.; Wu, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, G.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Yan, X.; Meng, A. Irisin attenuates fine particulate matter induced acute lung injury by regulating Nod2/NF-κB signaling pathway. Immunobiology. 2023, 228, 152358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Xiong, L.; Wu, T.; Wei, T.; Liu, N.; Bai, C.; Huang, X.; Hu, Y.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, T.; et al. NADPH oxidases regulate endothelial inflammatory injury induced by PM2.5 via AKT/eNOS/NO axis. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2022, 42, 738–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, R.; Li, X.Y.; He, Y.G. Ropivacaine has the potential to relieve PM2.5-induced acute lung injury. Exp. Ther. Med. 2022, 24, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, L.; Che, B.; Zhai, B.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Fan, G.; Liu, Z.; Feng, J.; et al. 1,25-Dihydroxy Vitamin D3 Attenuates the Oxidative Stress-Mediated Inflammation Induced by PM2.5via the p38/NF-κB/NLRP3 Pathway. Inflammation. 2019, 42, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.M.; Feng, J.; Zhang, J.; Gao, C.; Cao, J.Y.; Zhou, G.L.; Jiang, Y.J.; Jin, X.Q.; Yang, M.S.; Pan, J.Y.; et al. 1,25-Vitamin D3 protects against cooking oil fumes-derived PM2.5-induced cell damage through its anti-inflammatory effects in cardiomyocytes. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 79, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Zu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Shou, Q.; Ding, Z. PM2.5 Exposure Induces Inflammatory Response in Macrophages via the TLR4/COX-2/NF-κB Pathway. Inflammation. 2020, 43, 1948–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekki, K.; Ito, T.; Yoshida, Y.; He, C.; Arashidani, K.; He, M.; Sun, G.; Zeng, Y.; Sone, H.; Kunugita, N.; et al. PM2.5 collected in China causes inflammatory and oxidative stress responses in macrophages through the multiple pathways. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016, 45, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shou, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Liu, C.; Hu, Y.; Wang, H. A review of the possible associations between ambient PM2.5 exposures and the development of Alzheimer's disease. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 174, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiankhaw, K.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. PM2.5 exposure in association with AD-related neuropathology and cognitive outcomes. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 292, 118320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, R.E.; Shin, C.Y.; Han, S.H.; Kwon, K.J. Astaxanthin Suppresses PM2.5-Induced Neuro-inflammation by Regulating Akt Phosphorylation in BV-2 Microglial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Song, L.; Ding, H. Ophiopogonin D attenuates PM2.5-induced inflammation via suppressing the AMPK/NF-κB pathway in mouse pulmonary epithelial cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Ding, B.; Zhang, C.; Ding, Z.; Yu, X.; Lv, G. Coelonin, an Anti-Inflammation Active Component of Bletilla striata and Its Potential Mechanism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.S.; Fu, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiao, Y.; Chen, S.Q. Six phenanthrenes from the roots of Cymbidium faberi Rolfe and their biological activities. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 1170–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, X.D.; Zu, Y.Y.; Wang, B.X.; Li, M.Y.; Jiang, F.S.; Qian, C.D.; Zhou, F.M.; Ding, Z.S. Coelonin protects against PM2.5-induced macrophage damage via suppressing TLR4/NF-κB/COX-2 signaling pathway and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in vitro. Environ Toxicol. 2023, 38, 1196–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).