1. Introduction

One of the sphingolipid metabolites, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), is endogenously synthesized by two sphingosine kinases (SphK1 and SphK2). Sphk1 is predominantly localized in the cytosol and cell membrane, whereas Sphk2 is mainly present in the nucleus, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum1.

S1P act intracellularly as a second messenger regulating calcium release, cell death, cell proliferation, or it can be translocated extracellularly by transporter and then act as a ligand of S1P receptors (S1PRs). S1PRs, five subtypes (S1P1-5) are a high-affinity G protein-coupled receptor, coupling to G protein to activate downstream cascade2.

S1P is a minor lipid component in most biological samples, to deter-mine endogenous S1P level and investigate its functions, it is essential to develop a reliable, highly sensitive method for S1P. Recently, liquid chromatography-tandem mass chromatography (LC-MS/MS) with electrospray ionization (ESI) has been widely used for S1P analysis because of its high specificity and sensitivity3-5.

The main challenges in the development of S1P quantitative method are peak broadening due to the presence of polar phosphate head group and zwitterion formation in S1P 6. The negatively charged phosphate in S1P can also interact with the column metal ion, resulting in severe peak tailing and decreased detectability. To improve this peak broadening problem, modified methods using highly acidic mobile phase 7 8 or specific metal-free column have been applied 9. However, these conventional methods cannot completely solve the problem and require a specially designed column. An alternative breakthrough was the elimination of the phosphate group in S1P, which releases stable sphingosine free from peak broadening problem. The use of specific enzyme alkaline phosphatase (APase) of bovine intestine origin for S1P dephosphorylation was successful 10. However, this APase in animal origin is limited for use by critical problems on the activity changes, expensive and has an infection issue of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE).

The hydrogen fluoride (HF), both in organic and aqueous solution, can selectively cleave phosphorus-oxygen chemical bond. The first report of dephosphorylation reaction on nucleotides and alkyl phosphates by HF was published 11 12. Similarly, LC-MS/MS analysis after dephosphorylation of phosphoryl peptides showed the efficiency of HF in eliminating a phosphate group 13. In this regard, we investigated the utility of HF on the dephosphorylation of the sphingolipid S1P.

In this study, we established a new method by using HF to easily remove a phosphate from S1P and overcame the peak broadening problem by analyzing the surrogate sphingosine by LC-MS/MS. In addition, this method was successfully used to analyze S1P levels in serum and kidney tissues in an animal model of chronic kidney disease (CKD) induced by adenosine.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

D-erythro-sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) and C17-sphingosine-1-phosphate (C17-S1P) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc (Alabaster, AL, USA). Both were dissolved in methanol for stock solution. Hydrogen fluoride in pyridine (~70% HF) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Serum was purchased from Cytiva (Marlborough, MA, USA). All organic solvents were purchased from Honeywell Burdick & Jackson (Charlotte, NC, USA). Male Wistar rats were provided by Samtako Bio Korea (Osan, South Korea). Animals were maintained under controlled temperature at 21-22°C, optimized humidity conditions with 12/12-hour cycles. They were provided with standard chow and access to water. All animal experiments in this study were performed in accordance with the institutional animal care and use committees of Chungbuk National University.

2.2. CKD Animal Model

Rats were divided into 2 groups after 1 week of acclimatization. For CKD group (n=6), 600 mg/kg body weight adenine in 0.5% CMC was applied by oral gavage for 10 days. On the other hand, 0.5% CMC (2mL/200g body weight) was applied to the control group (n=6). On the 11th day, the rats were sacrificed. Blood samples were collected immediately and transferred to Eppendorf tubes containing anticoagulant. The tubes were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 3 minutes and the supernatant was transferred to new tubes. Kidney tissues were obtained by surgery and rinsed with PBS. All kidney tissues were stored at -80℃ until further analysis.

Plasma samples collected from control and CKD group rats were analyzed for creatinine, tryptophan, and kynurenine, which are widely accepted biomarkers for CKD diagnosis. The change in plasma creatinine level was determined by the Jaffé method using LabAssayTM. Creatinine Kit (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan). 50 µL of plasma proteins were deproteinized with 300 µL of deproteinization reagent. 100 µL of the supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate and mixed with 50 µL of picric acid reagent and 50 µL of 0.75 M sodium hydroxide solution. The mixture was kept at ambient temperature for 20 minutes before measurement using a microplate reader at a wavelength of 520 nm. For plasma tryptophan and kynurenine, 33 µL of 2M perchloric acid was added to 100 µL of rat plasma. Samples were vortexed vigorously for 1 minute and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to an HPLC vial and 20 µL of the supernatant was injected into the HPLC system. Agilent Technologies 1100 series LC system with DAD detector was used to detect tryptophan and kynurenine. Compounds were eluted with 92% acetonitrile (CAN) containing 5mM sodium acetate (pH=7.15) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min in a Waters C18 column (250 x 4.6 mm, 5 µm particle size) at 25oC. Tryptophan and kynurenine were detected at 365 and 267 nm, respectively.

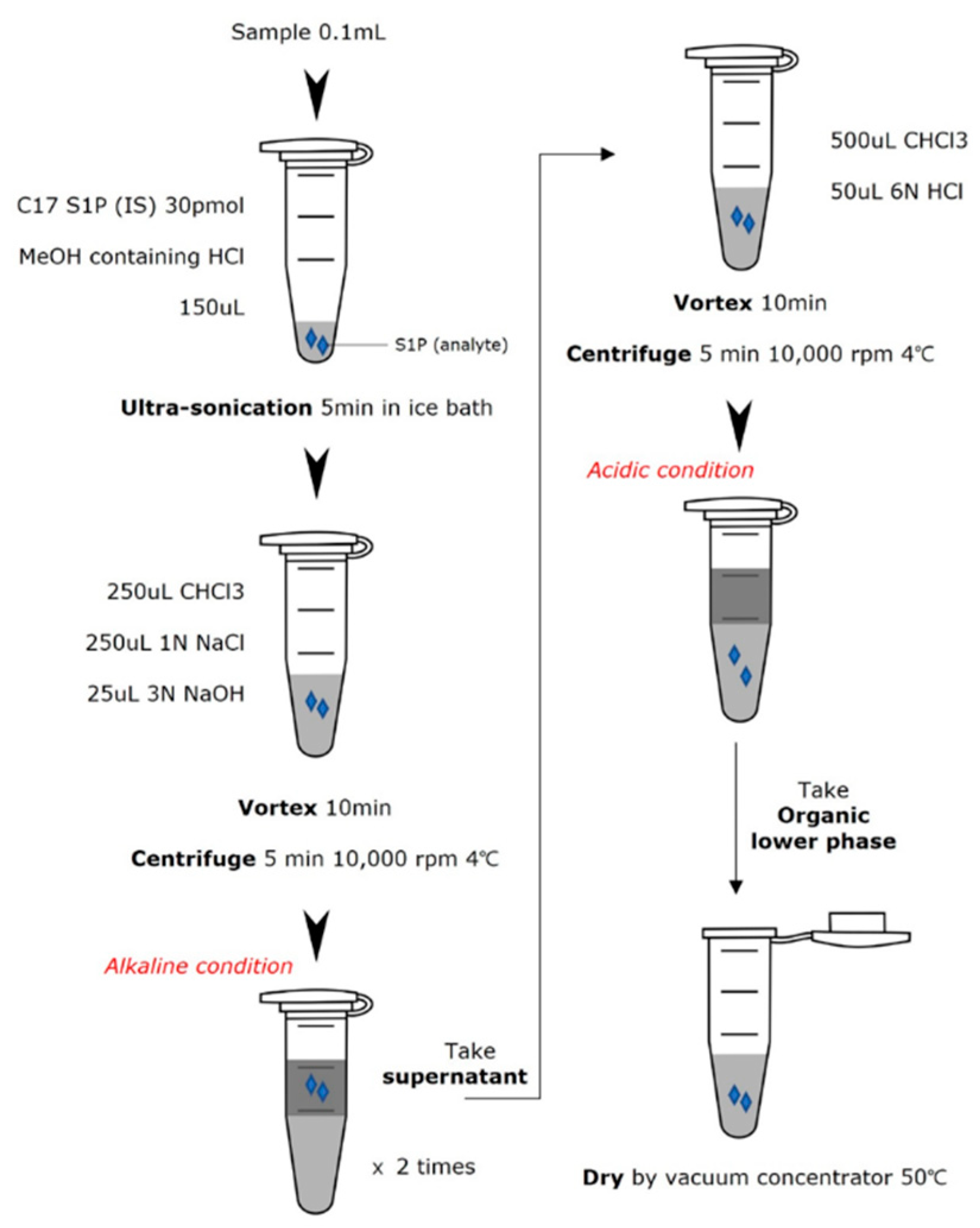

2.3. S1P Extraction

Kidney samples were homogenized by ultra-sonication in RIPA lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 140 mM NaCl) containing protease inhibitors. After complete homogenization, the tubes were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm, 4℃ for 10 min. The supernatant was collected for protein assay and S1P extraction. Protein assay was performed according to the instructions of the Thermo protein assay kit (Pierce, IL, USA). Plasma samples were thawed at 37°C. 100 μL of each sample was placed in an Eppendorf tube, and then 250 μL of methanol containing 0.6 μL of concentrated HCl and 30 pmol of C17-S1P as an internal standard was added. The tube was ultrasonicated in an ice-cold water bath for 5 minutes. After sonication, 250 μL CHCl

3, 250 μL 1 M NaCl and 25 μL 3 N NaOH were added. The tube was vortexed vigorously for 10 minutes and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 5 minutes. The alkaline aqueous phase containing S1P was transferred to a new tube. The remaining lower layer was re-extracted with 125 μL methanol, 125 μL 1 M NaCl, and 13 μL 3 N NaOH. The combined aqueous fraction of the s1p extract was then mixed with 600μL CHCl

3 and 50μL 6 N HCl. The tube was vortexed and centrifuged again. The CHCl

3 phase was transferred to a new tube and dried with a vacuum concentrator. The entire extraction scheme is described in

Figure 1.

2.4. S1P Dephosphorylation

The dried residue was reconstituted with 80 μL methanol. The tube was vortexed and then sonicated in a water bath for 10 minutes. Hydrogen fluoride (HF) 100uL was added to each sample and sealed with parafilm in an ice bath. The tube was vortexed and incubated at 25°C. After 1 hour, HF was evaporated under a nitrogen stream. The reaction was quenched by adding 300 μL of 10N sodium hydroxide. This was followed by 300 μL of dichloromethane (DCM) for the organic fraction and the tube was vortexed vigorously. The tube became cloudy due to precipitation of sodium fluoride. The tube was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 5 minutes, and the dephosphorylated S1P in the DCM layer was extracted twice. The combined DCM fraction was washed with alkaline water and evaporated through vacuum concentrators. Methanol was added to the dried residue prior to mass spectrometry injection.

2.5. LC-MS/MS Analysis

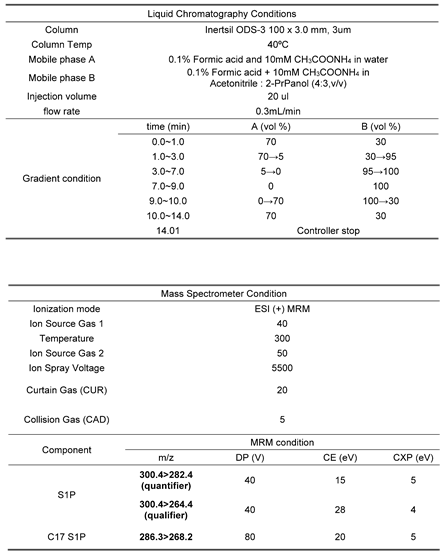

To determine S1P levels, liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) was performed on an AB Sciex QTRAP 3200 mass spectrometer coupled to a Shiseido Nanospace SI-2 HPLC system. Electrospray ionization (ESI) with positive ion mode was used as the ionization source. According to the manual tuning of direct infusion, the transition from precursor to product ions was found at optimized collision energies. The optimized ESI parameters are listed in

Table 1. The analytes were separated on an Inertsil ODS-3 column (100 x 3.0 mm, 3μm) maintained at 40℃. The mobile phase consisted of (A) 0.1% formic acid in water containing 10 mM ammonium acetate, (B) 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile:2-propanol (4:3, v/v). A gradient elution condition at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min was as follows: 0-1min, 30% B; 1-3min, 95% B; 3-7min, 100% B; 7-9min, hold 100% B; 9-10min. 30% B, 10-14min, hold 30% B for re-equilibration. Injection volume was 20 μL.

2.6. Method Validation

The method was validated for specificity, linearity, precision, accuracy, reproducibility, limit of quantitation (LOQ), limit of detection (LOD). Standard solution diluted with stock solution by methanol was used to determine specificity, linearity, LOQ, LOD. Specificity was evaluated by the presence of interference at the same retention time of the analyte. The correlation coefficient (R2) value of the calibration curve with standard solution for 3 different days was used to determine linearity. Signal-to-noise ratio (S/N ratio) was calculated to confirm LOQ and LOD. For LOQ, an S/N ratio of 10 was accepted and for LOD, an S/N ratio of 3. 2% BSA solution spiked with S1P and C17-S1P was used as the precision, accuracy, and reproducibility samples. Precision and accuracy were evaluated by relative standard deviation (RSD, %) and recovery (%) at 3 different concentrations with 3 individuals. A low concentration spiked sample was injected 6 times and the RSD % was calculated for reproducibility.

3. Results

3.1. S1P Extraction

A two-step extraction was used to determine S1P levels in biological samples. The extraction procedure was modified according to the previous report

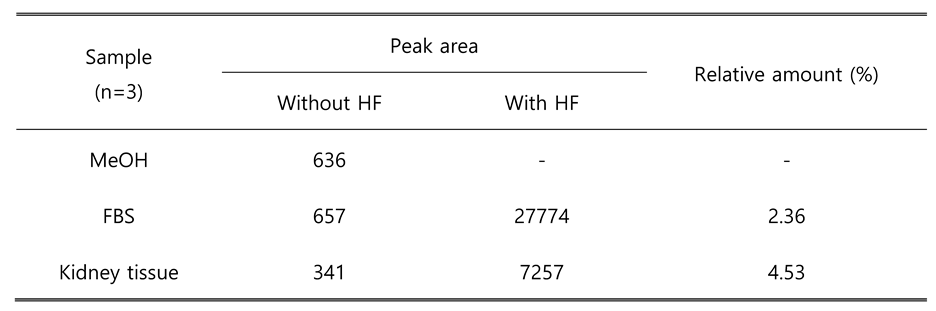

14. In a mixture of aqueous alkaline solution, methanol, and chloroform, S1P with polarity exists in the upper aqueous layer after centrifugation, while sphingosine and other major lipid components move to the organic solvent layer. After transfer of aqueous phase, acidic aqueous solution was added to decrease the polarity of phosphate group of S1P. Under acidic condition, S1P was followed in the lower chloroform phase and then injected into LC-MS/MS. Because the mass transitions of HF-derived dephosphorylated S1P were the same as those of sphingosine, it is important to separate S1P and sphingosine in the first extraction step. Without separation, S1P levels would be overestimated due to sphingosine background. To confirm sphingosine contamination, only methanol, FBS, kidney tissue extracts with and without HF treatment were prepared. The S1P peak area of each group was compared in the same injection batch (n=3). The results are summarized in

Table 2. Both serum sample and tissue sample, peak area was indicated similar with methanol sample and can be considered as background, which means the contamination level was negligible.

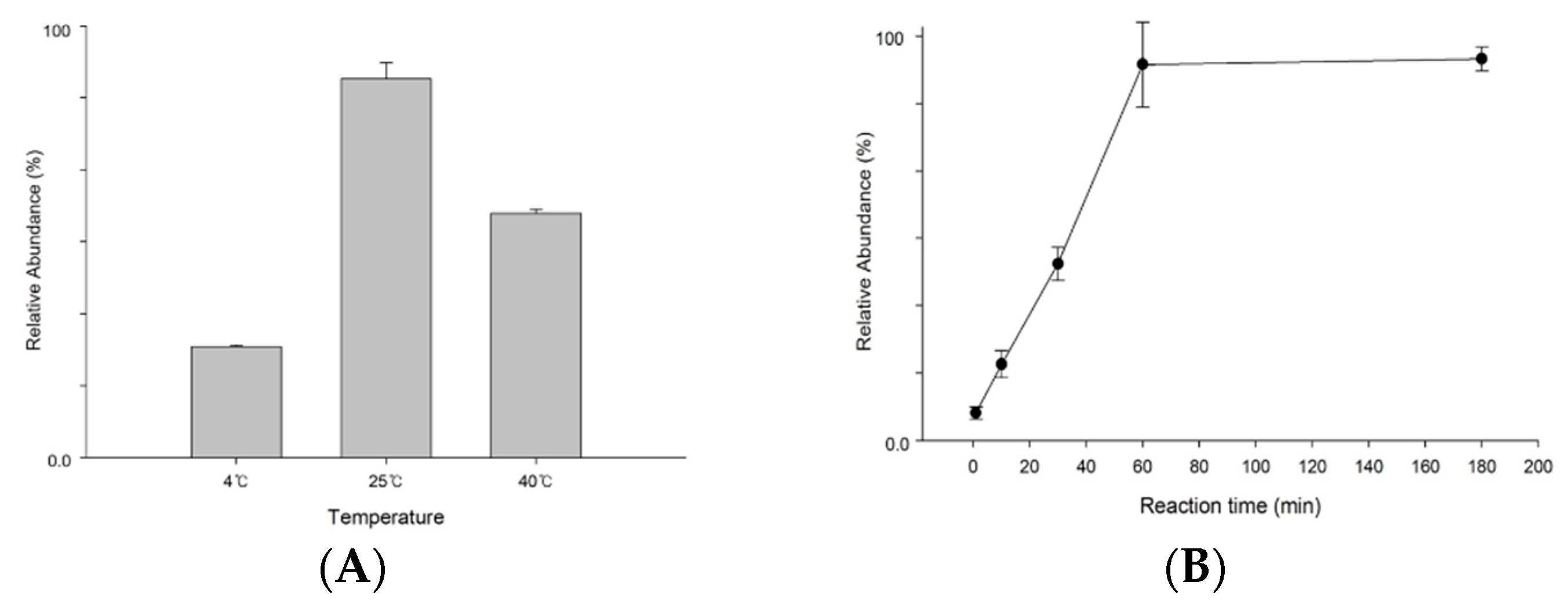

3.2. Optimization for S1P Dephosphorylation

The reaction condition of hydrogen fluoride (HF) dephosphorylation was optimized by considering the reaction temperature and time. HF was treated with S1P standard solution dissolved in methanol, and then tubes were kept overnight at 4℃, 25℃, 40℃ to determine the optimal temperature. After 1 hour, HF was evaporated, and the remaining solution was prepared for mass spectrometry as described above. As shown in

Figure 2A, reaction at 25℃ was optimal to eliminate the phosphate group at S1P. To decide the optimal reaction time, we keep the S1P standard solution at 25℃ for 180min. Each solution was injected into the mass spectrometer. The dephosphorylation yield increased and then became stable after 60 min, as shown in

Figure 2B . Thus, 1 hour was sufficient to react with S1P and hydrogen fluoride.

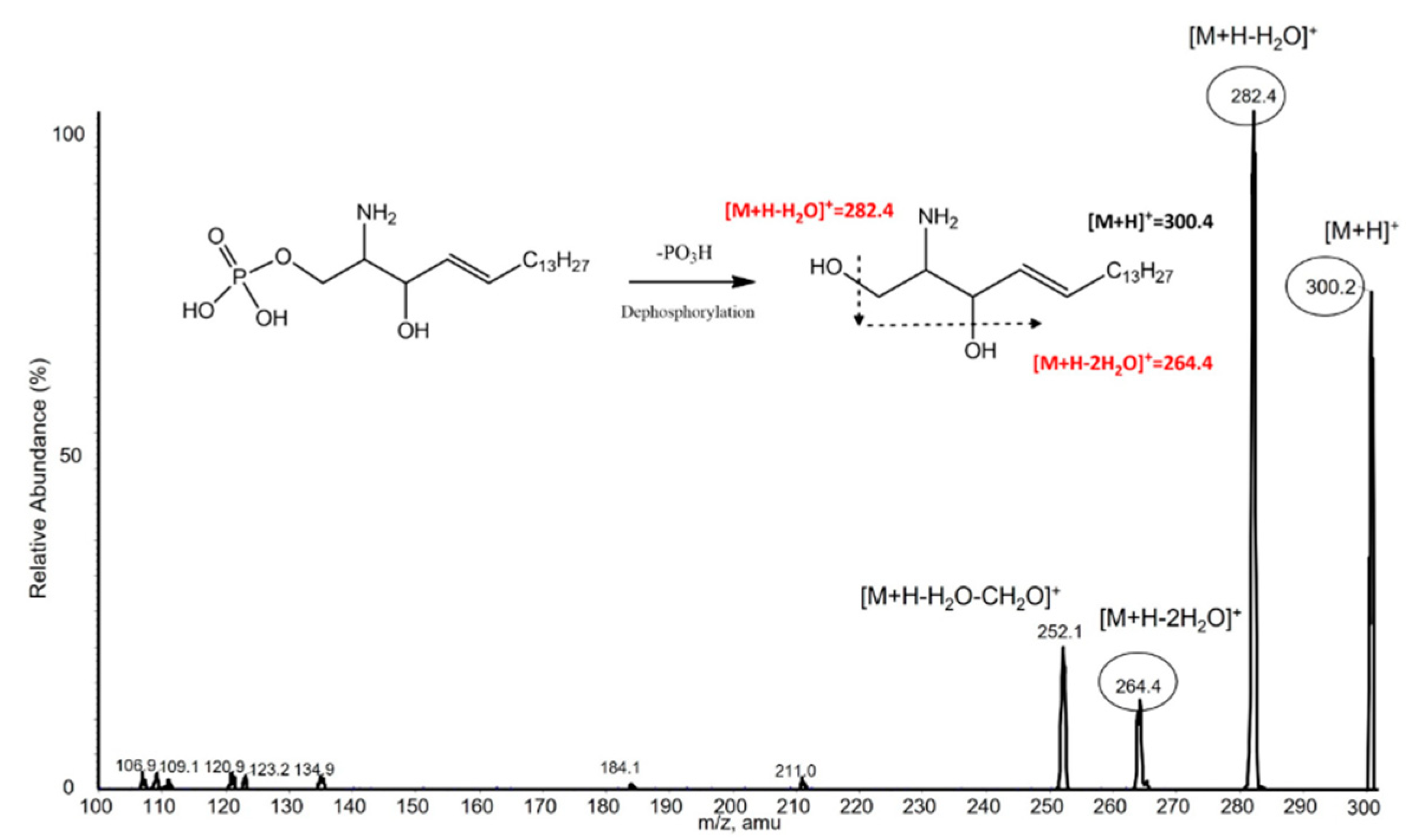

3.3. S1P Analysis by LC-MS/MS

To confirm the MRM transition, S1P and C17-S1P (IS) standard solution were injected directly into the mass spectrometer after dephosphorylation. Both compounds predominantly generated [M-PO3+H]

+ form at m/z 300.4 and m/z 286.3 as precursor ions in positive ion mode. The precursor ions then produced fragment ions in the collision energy product ion scan mode. The product ion mass spectra obtained by selecting these precursor ions are shown in

Figure 3. For S1P, m/z 282.4 was the abundant product ion corresponding to [M-PO3+H-H2O]

+, the minor fragment ion m/z 264.4 corresponding to [M-PO3+H-2H2O]

+. C17-S1P, which was used as an internal standard in our study, had the same pattern, so m/z 268.2 was obtained for the major product ion. This result showed that HF selectively eliminated the phosphate group from S1P, since the fragmentation pattern was consistent with that of sphingosine. Therefore, MRM transitions of m/z 300.4 → 282.4 were selected for S1P quantification, m/z 300.4 → 264.4 for S1P qualification, and m/z 286.3 → 268.2 for C17-S1P (IS).

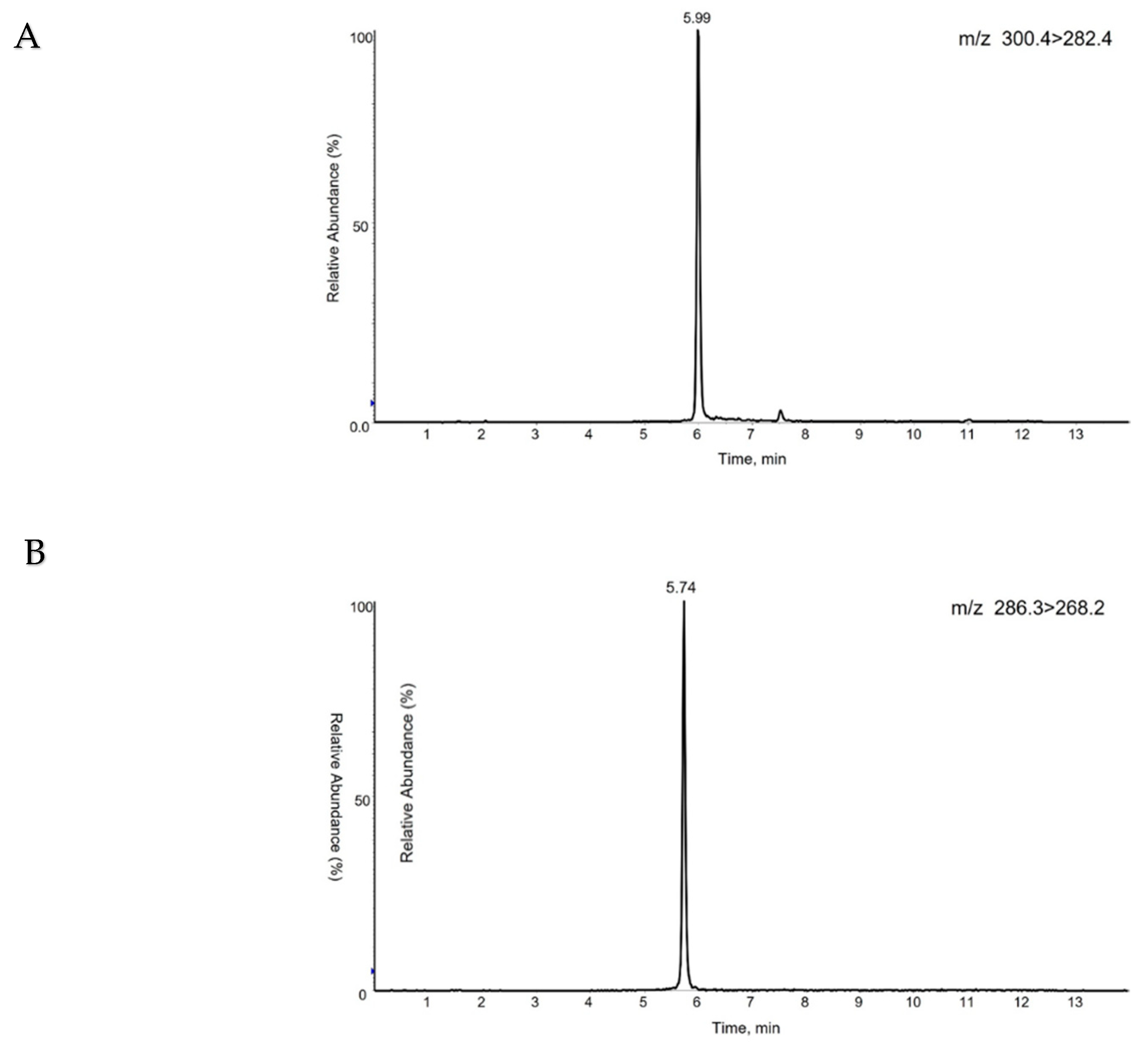

For high ionization yield, 10 mM ammonium acetate and 0.1% formic acid were added. The addition of formic acid also has the advantage of peak separation. For high resolution, isopropanol was used in combination with acetonitrile. With optimized gradient conditions, the retention time of S1P in our chromatography system was 5.99 min (

Figure 4A) and C17-S1P was 5.74 min (

Figure 4B).

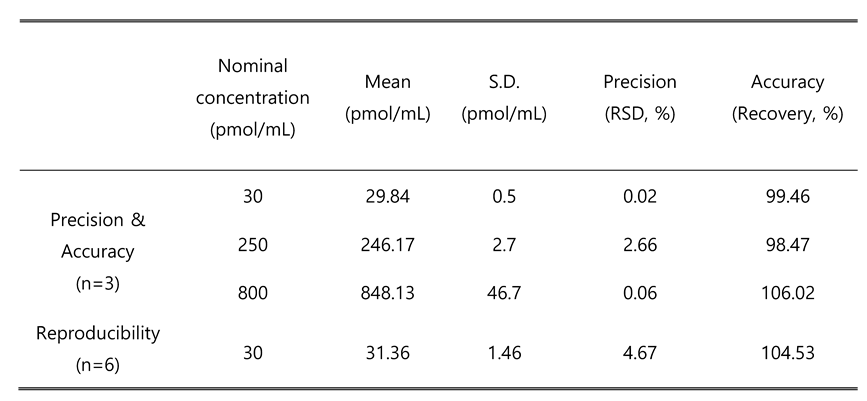

3.4. Method Validation

The peak of analyte and internal standard were well separated and had no interference as shown in

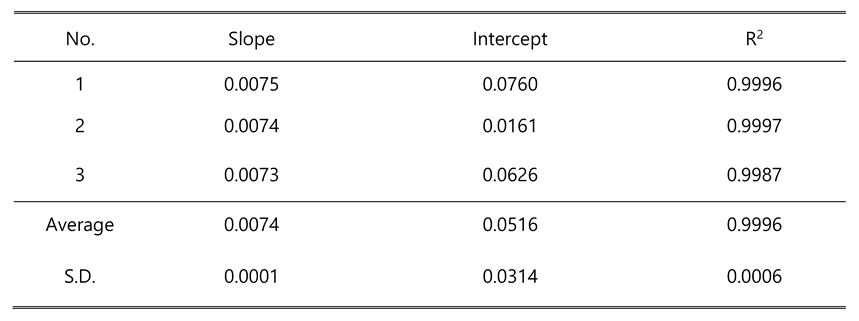

Figure 4. A calibration curve was drawn by peak ratio using C17-S1P as internal standard and had good linearity. The calibration equation was y=0.0074x+0.0516 (n=3) and the correlation coefficient (R

2) value was 0.9996 (n=3) in a range of 10~1000 nM (pmol/mL). Linearity data are shown in

Table 3. The limit of quantification was 10 nM (signal-to-noise ratio>10), and the limit of detection (signal-to-noise ratio>3) was 5 nM. The relative standard deviation (RSD) in 3 different concentrations for precision ranged from 0.02~2.66%. For accuracy, the recovery rate was 98.47~106.02% at 30, 250, 800 nM (pmol/mL) spiking samples with 3 individuals. The RSD at 30 nM spiking sample with 6 replicates for reproducibility was 4.67%. Detailed results are summarized in

Table 4.

3.5. S1P Levels in CKD Animal Model

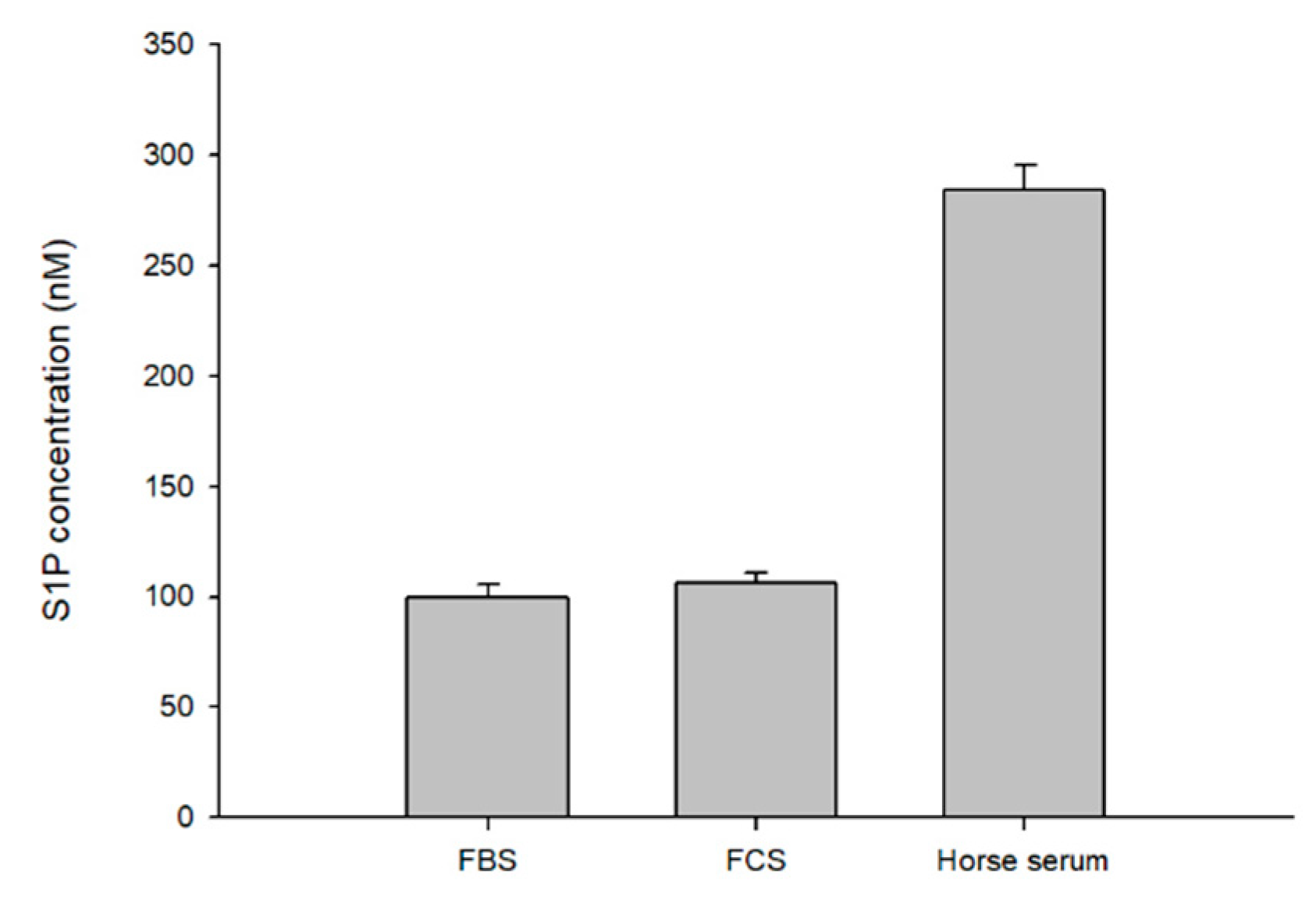

To apply our method to biological samples, we first determined S1P in commercial serum, fetal bovine serum (FBS), fetal calf serum (FCS), and horse serum. The S1P level in FBS was determined to be 100.02 ± 5.3 pmol/mL, FCS 106.54 ± 4.48 pmol/mL, and horse serum 284.38 ± 11.29 pmol/mL (mean ± SD) (

Figure 5).

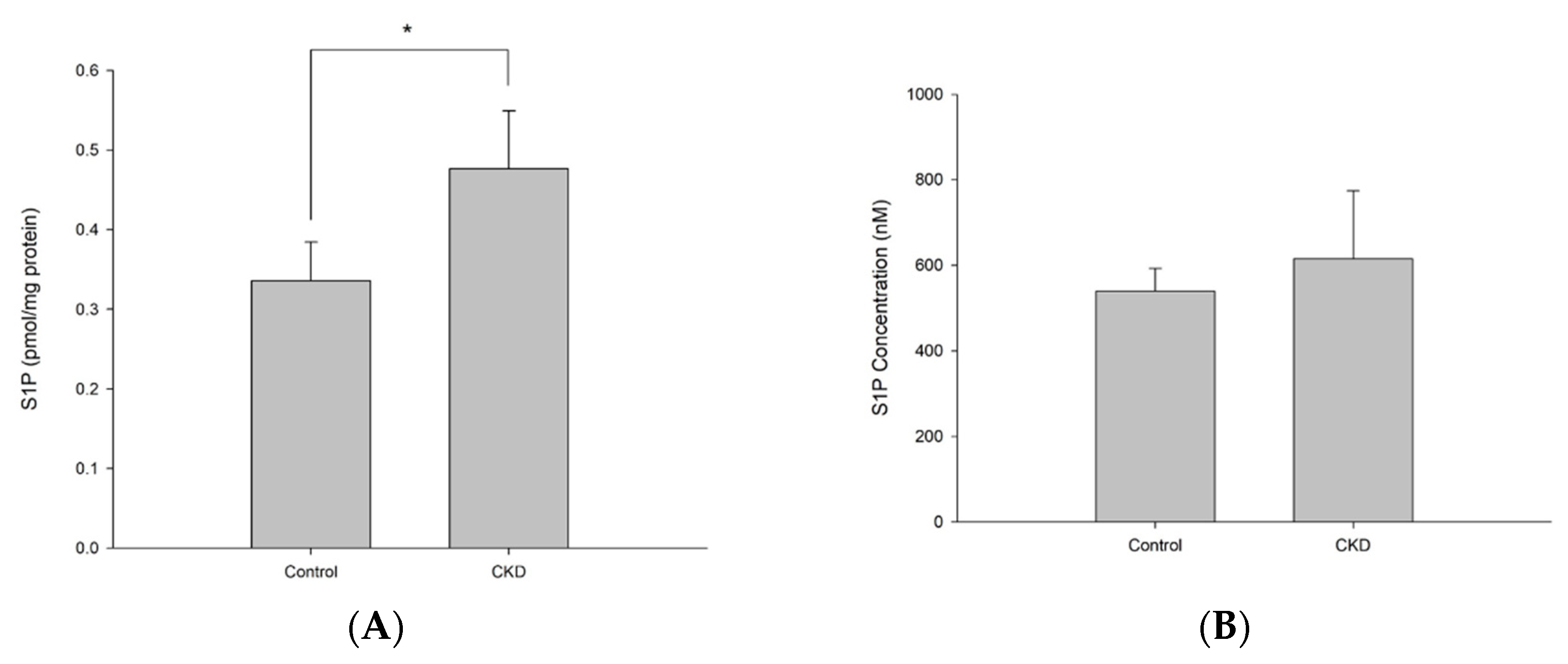

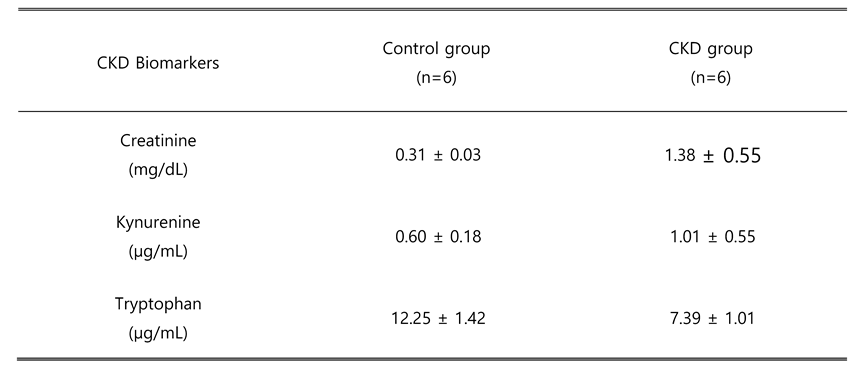

Second, we analyzed endogenous S1P in the CKD rat model (

Figure 6). To confirm that the CKD rat model treated with adenine for 10 days successfully induced CKD, we examined several biomarkers representing renal functions (

Table 5). Plasma creatinine was increased from 0.3 dm/ml to 1.38 dm/ml in the CKD group, expressing the deterioration of glomerular filtration. Kynurenine level was doubled in plasma of CKD rats, while tryptophan was reduced for 1.65-fold). The body mass of CKD rats remained unchanged, while control group rats gained about 50 g during the experiment. Conversely, the kidneys of CKD rats were enlarged and weighed almost 2.8 times more than those of controls.

As shown in

Figure 6, the plasma S1P level of the control group was 540.27 ± 53.1 pmol/mL, and that of the CKD group was 615.04 ± 159.2 pmol/mL.

Figure 5A showed slightly increased but not significant (p value>0.05). On the other hand, in kidney tissue, S1P concentration of control group showed 8.45 ± 0.5 pmol/mL, which was correlated with 0.336 ± 0.05 pmol/mg protein. On the other hand, S1P level of CKD group was 18.75 ± 3.5 pmol/mL, which correlated with 0.477 ± 0.07 pmol/mg protein (mean ± SD). As shown in

Figure 5B, a significant increase in S1P level was observed in the CKD group (p value<0.05). The reported plasma concentration is about 100~700 pmol/mL and the tissue concentration are about 1~10 pmol/mL

15, which correlate with the results of our study.

4. Discussion

In this study, we developed a new method for the quantification of S1P by LC-MS/MS. The method described here has high sensitivity with the use of HF dephosphorylation process. In addition, the analysis can be performed on general C18 column, which is the most popular and widely used reverse-phase column, without any peak-tailing problem. Using C17-S1P as the internal standard, we can obtain the reproducible S1P quantification results. Method validation was performed on several parameters and showed good specificity, linearity, precision, and accuracy. The LOD of this method was 5 pmol/mL, which is possible to detect low level of endogenous S1P in tissues and it was similar with recently reported methods.

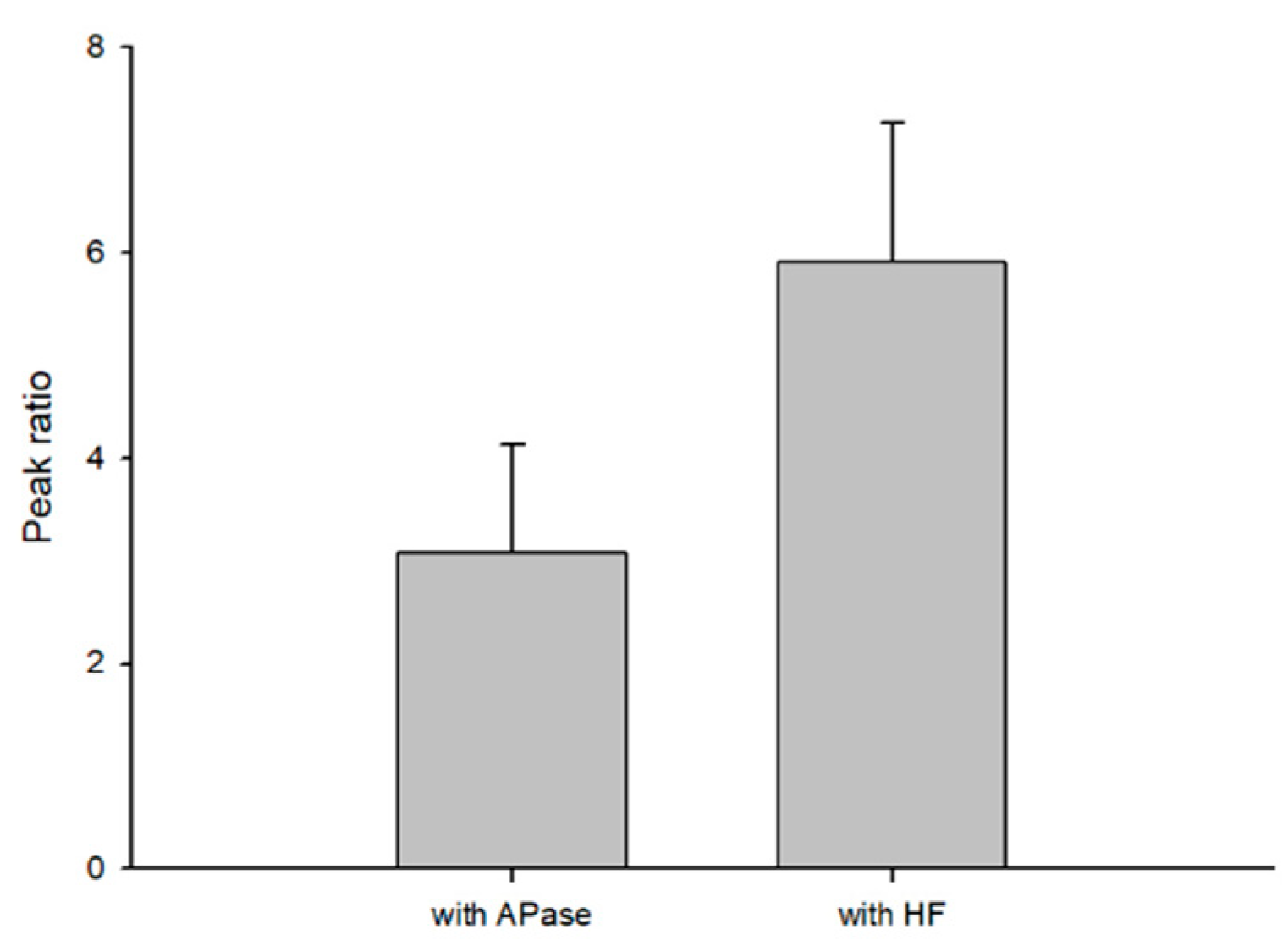

In this study, we compared the dephosphorylation reaction efficiency of HF and APase with S1P standard solution and C17 sphingosine standard solution as internal standard (

Figure 7). The dephosphorylation ability of HF exhibited clearly better efficiency than APase. HF is easier to obtain in the laboratory and the cost is much lower priced than APase.

HF was an effective reagent for the analysis of S1P by dephosphorylation, but careful handling was required. In addition, HF produces corrosive fumes that can easily penetrate the skin and cause severe burns 16. Researchers should use appropriate safety equipment and always work in a fume hood. HF can dissolve glass containers, so to transfer, using plastic bottle or tube after tightly sealed was required 17.

We analyzed serum S1P levels in 3 different sera. As shown in

Figure 5, fetal bovine serum and fetal calf serum has a similar concentration. However, horse serum has higher level of S1P. We thought it was due to the difference in erythrocyte level between different species. The reference interval of bovine erythrocytes is 4.9-7.5 106/μL

18 and that of horse is 6.10-11.0 106/μL

19. Since S1P was highly abundant in mature erythrocytes with high activity of Sphk1, higher level of erythrocyte species seems to produce higher level of S1P in serum

20 21.

The role of S1P in CKD has not been fully established, although a protective role of S1P has been suggested in renal fibrosis, which is a clinical manifestation of CKD 22. Several studies have reported upregulation of renal Sphk1 in various kidney disease models 23 24. In addition, S1P2 is highly expressed in renal ischemia and reperfusion injury, which may lead to renal fibrosis 25 26. According to our experimental results, kidney tissues of CKD group showed increased S1P level, while there was no significant increase in plasma. During the progression of CKD, inflammatory cytokines including transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) are secreted, which cause renal fibrosis. Since TGF-β is known to stimulate Sphk1, we can correlate elevated S1P levels with CKD kidney tissue 27. Further research will be necessary to elucidate plasma S1P level in CKD model as well as to find out S1P function and therapeutic target in CKD.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we established the new S1P analysis method with HF dephosphorylation by LC-MS/MS, which was highly sensitive and effective to quantify S1P level. With this new method, we compared S1P level in plasma and kidney tissue of chronic kidney disease model. The method can also be used in various biological samples and find a therapeutic role of S1P in various diseases including CKD.

Author Contributions

conceptualization, Y.-M.L.; methodology, S.G., H.-J.K., and S.-H.J.; validation, H.-J.K.; formal analysis, H.-J.K., S.G., and H.-G.L.; investigation, H.-G.L.; data curation, H.-J.K., S.-H.J., and O.B.; writing—original draft preparation, H.-J.K., S.-H.J., and Y.-M.L.; writing—review and editing, O.B., and Y.-M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a funding for the academic research program of Chungbuk National University in 2022.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nguyen, T. Q.; Vu, T. M.; Tukijan, F.; Muralidharan, S.; Foo, J. C.; Li Chin, J. F.; Hasan, Z.; Torta, F.; Nguyen, L. N. Erythrocytes efficiently utilize exogenous sphingosines for S1P synthesis and export via Mfsd2b. J Biol Chem 2021, 296, 100201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantinescu, V.; Haase, R.; Akgun, K.; Ziemssen, T. S1P receptor modulators and the cardiovascular autonomic nervous system in multiple sclerosis: a narrative review. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2022, 15, 17562864221133163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luth, A.; Neuber, C.; Kleuser, B. Novel methods for the quantification of (2E)-hexadecenal by liquid chromatography with detection by either ESI QTOF tandem mass spectrometry or fluorescence measurement. Anal Chim Acta 2012, 722, 70–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielawski, J.; Pierce, J. S.; Snider, J.; Rembiesa, B.; Szulc, Z. M.; Bielawska, A. Sphingolipid analysis by high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS). Adv Exp Med Biol 2010, 688, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oizumi, H.; Sugimura, Y.; Totsune, T.; Kawasaki, I.; Ohshiro, S.; Baba, T.; Kimpara, T.; Sakuma, H.; Hasegawa, T.; Kawahata, I.; Fukunaga, K.; Takeda, A. Plasma sphingolipid abnormalities in neurodegenerative diseases. PLoS One 2022, 17(12), e0279315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demont, E. H.; Arpino, S.; Bit, R. A.; Campbell, C. A.; Deeks, N.; Desai, S.; Dowell, S. J.; Gaskin, P.; Gray, J. R.; Harrison, L. A.; Haynes, A.; Heightman, T. D.; Holmes, D. S.; Humphreys, P. G.; Kumar, U.; Morse, M. A.; Osborne, G. J.; Panchal, T.; Philpott, K. L.; Taylor, S.; Watson, R.; Willis, R.; Witherington, J. Discovery of a brain-penetrant S1P(3)-sparing direct agonist of the S1P(1) and S1P(5) receptors efficacious at low oral dose. J Med Chem 2011, 54(19), 6724–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saigusa, D.; Shiba, K.; Inoue, A.; Hama, K.; Okutani, M.; Iida, N.; Saito, M.; Suzuki, K.; Kaneko, T.; Suzuki, N.; Yamaguchi, H.; Mano, N.; Goto, J.; Hishinuma, T.; Aoki, J.; Tomioka, Y. , Simultaneous quantitation of sphingoid bases and their phosphates in biological samples by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem 2012, 403(7), 1897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frej, C.; Andersson, A.; Larsson, B.; Guo, L. J.; Norstrom, E.; Happonen, K. E.; Dahlback, B. Quantification of sphingosine 1-phosphate by validated LC-MS/MS method revealing strong correlation with apolipoprotein M in plasma but not in serum due to platelet activation during blood coagulation. Anal Bioanal Chem 2015, 407(28), 8533–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, S. G. B.; Nakahashi, A.; Yamane, K.; Nakahashi, S.; Murai, Y.; Siddegowda, A. K. C.; Hammam, M. A. S.; Monde, K. Facile Chemoselective Strategy toward Capturing Sphingoid Bases by a Unique Glutaraldehyde-Functionalized Resin. ACS Omega 2018, 3(1), 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J. K.; Yoo, H. S.; Lee, E. Y.; Lee, W. J.; Lee, Y. M. Simultaneous quantitative analysis of sphingoid base 1-phosphates in biological samples by o-phthalaldehyde precolumn derivatization after dephosphorylation with alkaline phosphatase. Anal Biochem 2002, 303(2), 167–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenard, J. Reactions of proteins, carbohydrates, and related substances in liquid hydrogen fluoride. Chem Rev 1969, 69(5), 625–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, M.; Bobrow, E. Hydrolysis of purine and pyrimidine ribosides and 2-deoxyribosides with liquid hydrogen fluoride. Mt Sinai J Med 1970, 37(3), 206–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuyama, H.; Toda, C.; Watanabe, M.; Tanaka, K.; Nishimura, O. An efficient chemical method for dephosphorylation of phosphopeptides. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 2003, 17(13), 1493–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwisch, L.; Schafer-Korting, M.; Kleuser, B. An improved high-performance liquid chromatographic method for the determination of sphingosine-1-phosphate in complex biological materials. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2001, 363(3), 358–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdyshev, E. V.; Gorshkova, I. A.; Garcia, J. G.; Natarajan, V.; Hubbard, W. C. Quantitative analysis of sphingoid base-1-phosphates as bisacetylated derivatives by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem 2005, 339(1), 129–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerin, D. L.; Hatcher, J. D., Hydrofluoric Acid Burns. In StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Jason Hatcher declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies., 2023.

- Ghoreishi, S. M.; Beiggy, M.; Mazloum Ardekani, M. Optimization of gas chromatography using short glass capillary column with mass spectrometry for identification and evaluation of commercial heavy alkylbenzene structures. Anal Bioanal Chem 2003, 375(8), 1212–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roland, L.; Drillich, M.; Iwersen, M. Hematology as a diagnostic tool in bovine medicine. J Vet Diagn Invest 2014, 26(5), 592–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauricio, C. R.; Schneider, F. K.; Dos Santos, L. C. Image-based red cell counting for wild animals blood. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2010, 2010, 438–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hanel, P.; Andreani, P.; Graler, M. H. Erythrocytes store and release sphingosine 1-phosphate in blood. FASEB J 2007, 21(4), 1202–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, S.; Sunkara, M.; Salous, A. K.; Leung, S. W.; Berdyshev, E. V.; Bailey, A.; Campbell, C. L.; Charnigo, R.; Morris, A. J.; Smyth, S. S. Plasma levels of sphingosine 1-phosphate are strongly correlated with haematocrit, but variably restored by red blood cell transfusions. Clin Sci (Lond) 2011, 121(12), 565–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Ren, Y.; Yao, F.; Duan, J.; Zhao, H.; Du, Y.; Xiao, X.; Duan, H.; Shi, Y. Sphingosine kinase 1 protects renal tubular epithelial cells from renal fibrosis via induction of autophagy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2017, 90, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S. Y.; Kim, D. H.; Sung, S. A.; Kim, M. G.; Cho, W. Y.; Kim, H. K.; Jo, S. K. Sphingosine-1-phosphate reduces hepatic ischaemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury through attenuation of endothelial injury in mice. Nephrology (Carlton) 2011, 16(2), 163–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, A.; Pfeilschifter, J.; Huwiler, A. Sphingosine 1-phosphate in renal diseases. Cell Physiol Biochem 2013, 31(6), 745–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, D. J.; Pescio, L. G.; Santacreu, B. J.; Mosca, J. M.; Sterin-Speziale, N. B.; Favale, N. O. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 plays a dual role depending on the stage of cell differentiation in renal epithelial cells. Life Sci 2023, 316, 121404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuyama, M.; Funao, K.; Kuratsukuri, K.; Tanaka, T.; Kawahito, Y.; Sano, H.; Chargui, J.; Touraine, J. L.; Yoshimura, N.; Yoshimura, R. Expression of sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor in rat renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Mol Med Rep 2010, 3(2), 233–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, T. N.; Chen, X.; Li, R.; Gao, B.; Mohammed-Ali, Z.; Lu, C.; Yum, V.; Dickhout, J. G.; Krepinsky, J. C. SREBP-1 Mediates Angiotensin II-Induced TGF-beta1 Upregulation and Glomerular Fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015, 26(8), 1839–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).