Submitted:

17 December 2023

Posted:

19 December 2023

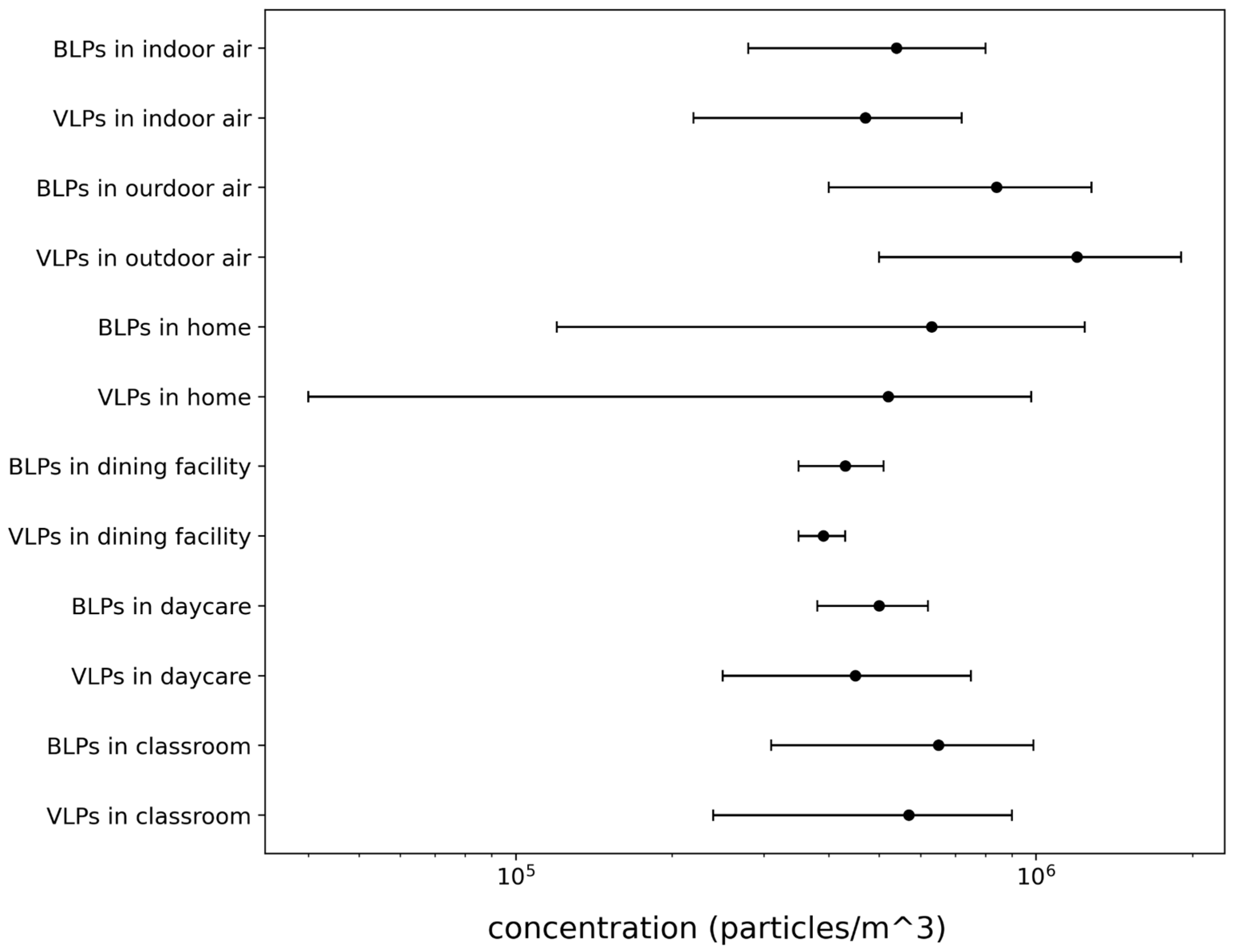

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

What is air sampling?

How are air samples collected?

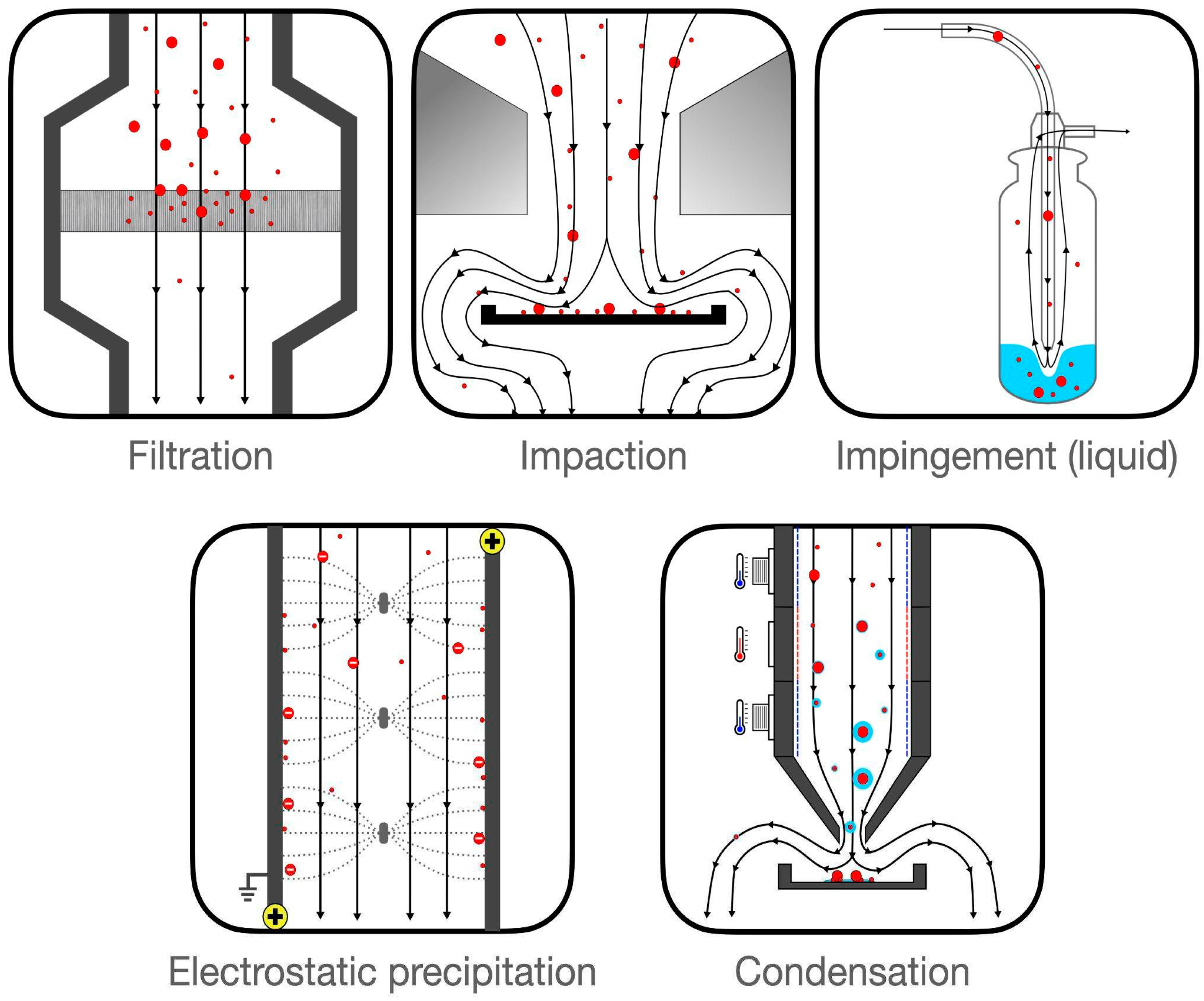

- Filtration: This method employs various physical mechanisms to capture particles of different sizes. The complexity of these mechanisms is considerable and is discussed in greater detail in this report (see page 5).

- Impaction: These methods gather particles that possess sufficient inertia to deviate from an airstream following a sudden directional change.

- Impingement: This technique involves inertial separation into a liquid medium. While liquid mediums generally facilitate easier sample recovery, they can evaporate rapidly under high flow rates.

- Electrostatic Precipitation: This approach charges incoming particles, which are then attracted or repelled towards a collection medium through electrostatic forces.

- Condensation: This method utilizes temperature variations to create water droplets around particles, making them heavy enough to fall into a collection medium.

What is in the air?

What are promising locations for air sampling?

Conclusion: challenges and opportunities

Appendix 1: Air sampling methods

Filtration and filter-based samplers

- Filter-based samplers excel in processing large air volumes, enhancing NA collection and allowing for greater sampling frequency.

- Verreault 2008 indicated that filters are particularly effective in physically recovering nanoscale-size particles, including many viral aerosols (3). Despite often having larger pore sizes, it’s typically diffusion, a Brownian motion phenomenon, that enables the collection of nanoscale particles on filters (45).

- A major limitation of many filter-based methods is NA recovery. Simple elution techniques may yield low NA recovery, whereas more intensive methods like bead beating can cause excessive fragmentation of NA. However, with sufficient sample volume, these recovery challenges might be manageable. Innovations like dissolvable or washable filters (52), along with vortexing and ultrasonic agitation techniques, offer potential solutions.

- Most filter-based samplers, except those using gelatin filters, are not conducive to preserving microbe viability, limiting their suitability for culture-based analysis (1, 3). Filters may cause structural damage such as membrane degradation (53) and increase virus desiccation, leading to infectivity loss (3). Prolonged sampling time has also been shown to exacerbate microbe viability loss (54, 55). However, for metagenomic studies, desiccation and infectivity loss are less concerning as long as the viral genomes remain intact.

Impaction-based samplers

- Easy separation and determination of different particle sizes, potentially allowing for enrichment of virus-laden particles.

- Easy to perform culture-based analysis; airborne particles impact agar plates which can be moved directly into an incubator. However, this is not a useful feature for collecting MGS samples.

- Can determine aerosol concentrations over time with a rotating collection medium, typically a rotating agar plate.

- The sudden deceleration upon impaction can damage microbes (53,55,58).

- When used to collect NA via filters, inertia-based separation may add complexity and curb air intake rates.

Liquid-based samplers

- Liquid mediums allow for easier sample preparation and enhanced NA recovery efficiency.

- Least destructive collection method, preventing desiccation and improving recovery of infectious viral particles (3, 59).

- Can be used in a multi-stage format to separate and identify particle sizes.

- High impaction velocities and liquid evaporation may compromise microbe viability for infectivity assays and cause particle re-aerosolization (60, 61).

- Some critiques point to the typically low flow rates of liquid-based samplers, although this does not take into account the capabilities of cyclone-class collectors.

Electrostatic-based samplers

- Gentle on collected samples compared to other methods.

- Compatible with a variety of collection mediums, allowing for customization.

- Requires less power for operation.

- Capable of achieving high flow rates.

- Relatively under-investigated, possibly due to advancements in alternative collection methods.

- Generation of ozone during particle charging, which may degrade microbes and pose health risks in poorly ventilated areas (64).

- Limited availability of ESPs on the commercial market.

Condensation samplers

- 1.

- Conditioner Stage: Air first enters the conditioner, a cool (5°C) wet wall section of the growth tube, where incoming particles acquire a thin water film.

- 2.

- Initiator Stage: The air then progresses to the initiator, where additional water vapor is introduced. Here, higher temperatures (35°C) create a supersaturated environment, encouraging larger droplet formation around particles.

- 3.

- Moderator Stage: In the moderator at 12°C, excess water vapor is removed, permitting continued droplet growth.

- 4.

- Exit: Air then exits the growth tube, with droplets impacting onto a collection medium.

- Pros

- Unlike traditional liquid- and filter-based methods, condensation sampling avoids high-velocity impacts, making it a non-destructive technique ideal for preserving microbe viability and genomic integrity.

- Condensation samplers typically have low flow rates. For instance, the Spot Sampler operates at only 1.5 L/min, posing a challenge in collecting sufficient NA samples in short timeframes.

- The market and research base for condensation samplers seem relatively underdeveloped, as indicated by their limited discussion in two comprehensive review papers on bioaerosol sampling (1, 3).

Appendix 2: Concentrations

Appendix 3: Outdoor sampling

- The SIGMA+ program from DARPA employs outdoor air collection through emergency vehicles equipped with custom air samplers and portable samplers like the pBDi.

- The U.S. government’s BioWatch program initially utilized existing EPA air sampling sites and collectors, predominantly outdoor. Many of these were located near airports and other urban centers (6, 88, 89). The current sampling locations of BioWatch are not publicly available.

- The Kromek Biosequencer is an innovative system, attaching an air sampler to a vehicle, integrating automated sample preparation and long-read sequencing capabilities.

Appendix 4: In-duct sampling

Appendix 5: NA recovery BOTEC

Concentrations

- BLPs in indoor environment = 540 BLP/L (Prussin et al. 2015)

- VLPs in indoor environment = 470 VLP/L (Prussin et al. 2015)

Genome

- Typical bacterial genome = 5E6 bp/BLP

- Typical viral genome = 4E4 bp/VLP

- Mass of single bp = 1.08E-12 ng/bp

Air sampling

- Flow rate of air sampler = 200 L/min = 3.33 L/s (ACD 200 Bobcat air sampler)

- Sampling time = 8 hr = 28800 s

NA recovery

- NA recovery rate = Flow rate × Microbe concentration × Typical genome mass

- NA recovery rate = (3.33 L/s)×[(5E6 bp/BLP)×(540 BLP/L) + (4E4 bp/VLP)×(470 VLP/L)]×(1.08E-12 ng/bp)

- NA recovery rate = 0.0098 ng/s

- NA recovered over 8 hours = 280 ng

Assumptions

- Each VLP and BLP contains only one standard viral or bacterial genome. In reality, airborne particles often contain multiple microbes. This assumption pushes the results in the “more NA” direction.

- Microbe concentrations remain unchanged as a result of air sampling, which is probably a valid assumption in large indoor spaces, but doesn’t hold in more confined environments. This assumption pushes the results in the “less NA” direction.

References

- Mainelis G. Bioaerosol sampling: Classical approaches, advances, and perspectives. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2020 May 3;54(5):496–519.

- Lindsley WG, Green BJ, Blachere FM, Martin SB, Law BF, Jensen PA, et al. Sampling and characterization of bioaerosols [Internet]. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; 2017 Mar. (Manual of Analytical Methods (NMAM)). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/nmam/pdf/chapter-ba.pdf.

- Verreault D, Moineau S, Duchaine C. Methods for Sampling of Airborne Viruses. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2008 Sep;72(3):413–44.

- Prussin AJ, Marr LC, Bibby KJ. Challenges of studying viral aerosol metagenomics and communities in comparison with bacterial and fungal aerosols. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2014 Aug;357(1):1–9.

- Prussin AJ, Torres PJ, Shimashita J, Head SR, Bibby KJ, Kelley ST, et al. Seasonal dynamics of DNA and RNA viral bioaerosol communities in a daycare center. Microbiome. 2019 Apr 1;7(1):53.

- Be NA, Thissen JB, Fofanov VY, Allen JE, Rojas M, Golovko G, et al. Metagenomic Analysis of the Airborne Environment in Urban Spaces. Microb Ecol. 2015 Feb 1;69(2):346–55.

- Hall RJ, Leblanc-Maridor M, Wang J, Ren X, Moore NE, Brooks CR, et al. Metagenomic Detection of Viruses in Aerosol Samples from Workers in Animal Slaughterhouses. PLOS ONE. 2013 Aug 14;8(8):e72226.

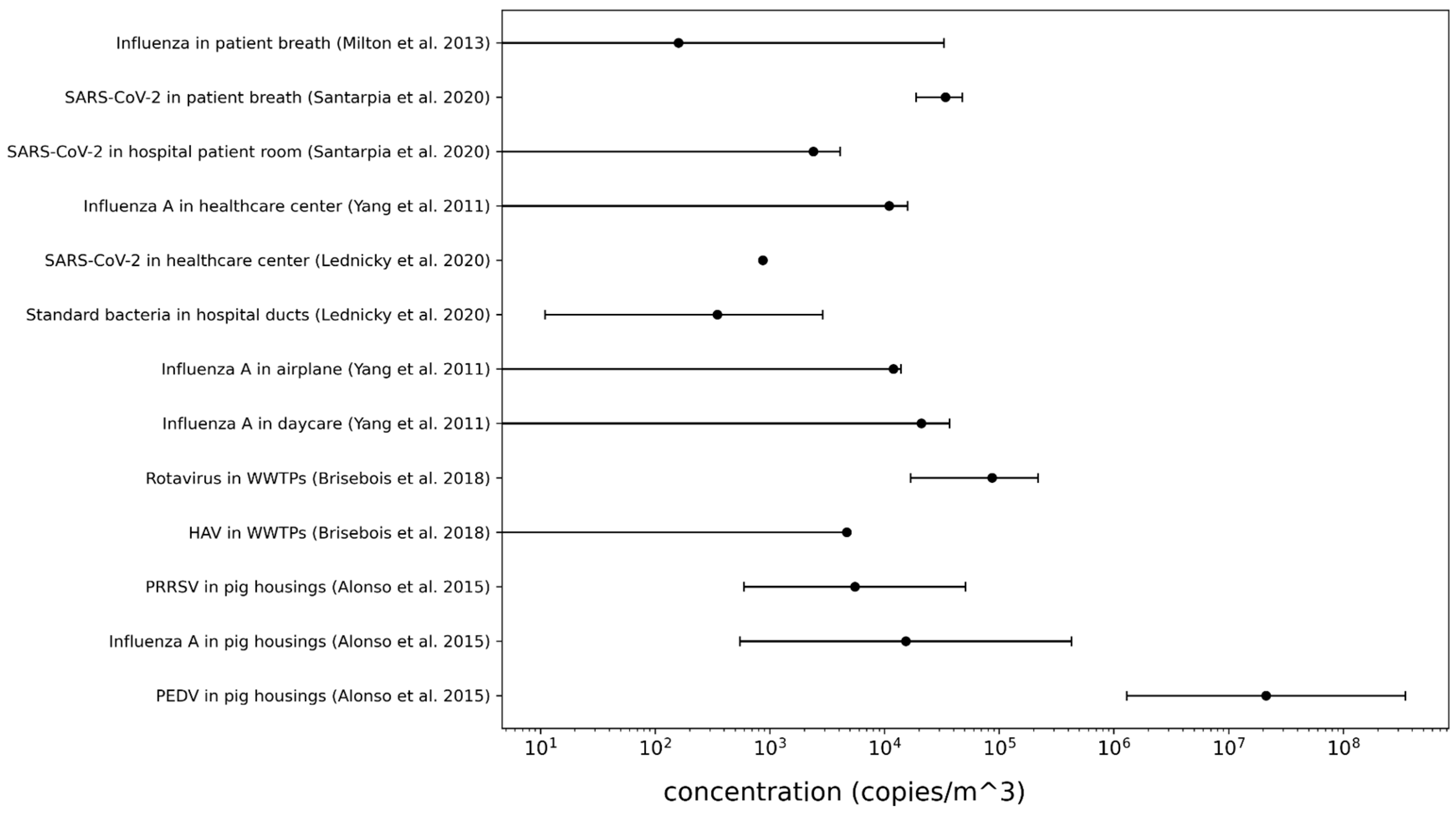

- Brisebois E, Veillette M, Dion-Dupont V, Lavoie J, Corbeil J, Culley A, et al. Human viral pathogens are pervasive in wastewater treatment center aerosols. Journal of Environmental Sciences. 2018 May 1;67:45–53.

- Leung MHY, Tong X, Bøifot KO, Bezdan D, Butler DJ, Danko DC, et al. Characterization of the public transit air microbiome and resistome reveals geographical specificity. Microbiome. 2021 May 26;9(1):112.

- Cao C, Jiang W, Wang B, Fang J, Lang J, Tian G, et al. Inhalable Microorganisms in Beijing’s PM2.5 and PM10 Pollutants during a Severe Smog Event. Environ Sci Technol. 2014 Feb 4;48(3):1499–507.

- Ratnesar-Shumate S, Bohannon K, Williams G, Holland B, Krause M, Green B, et al. Comparison of the performance of aerosol sampling devices for measuring infectious SARS-CoV-2 aerosols. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2021 Aug 3;55(8):975–86.

- Dietz L, Constant DA, Fretz M, Horve PF, Olsen-Martinez A, Stenson J, et al. Exploring Integrated Environmental Viral Surveillance of Indoor Environments: A comparison of surface and bioaerosol environmental sampling in hospital rooms with COVID-19 patients [Internet]. medRxiv; 2021 [cited 2022 Nov 14]. p. 2021.03.26.21254416. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.03.26.21254416v1.

- Kenarkoohi A, Noorimotlagh Z, Falahi S, Amarloei A, Mirzaee SA, Pakzad I, et al. Hospital indoor air quality monitoring for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) virus. Science of The Total Environment. 2020 Dec 15;748:141324.

- Angel DM, Gao D, DeLay K, Lin EZ, Eldred J, Arnold W, et al. Development and Application of a Polydimethylsiloxane-Based Passive Air Sampler to Assess Personal Exposure to SARS-CoV-2. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2022 Feb 8;9(2):153–9.

- Ramuta MD, Newman CM, Brakefield SF, Stauss MR, Wiseman RW, Kita-Yarbro A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens are detected in continuous air samples from congregate settings. Nat Commun. 2022 Aug 11;13(1):4717.

- Sousan S, Fan M, Outlaw K, Williams S, Roper RL. SARS-CoV-2 Detection in air samples from inside heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems- COVID surveillance in student dorms. American Journal of Infection Control. 2022 Mar 1;50(3):330–5.

- Lednicky JA, Lauzardo M, Fan ZH, Jutla A, Tilly TB, Gangwar M, et al. Viable SARS-CoV-2 in the air of a hospital room with COVID-19 patients. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020 Nov 1;100:476–82.

- Horve PF, Dietz L, Northcutt D, Stenson J, Wymelenberg KVD. Evaluation of a bioaerosol sampler for indoor environmental surveillance of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. PLOS ONE. 2021 Nov 15;16(11):e0257689.

- Liu Y, Ning Z, Chen Y, Guo M, Liu Y, Gali NK, et al. Aerodynamic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in two Wuhan hospitals. Nature. 2020 Jun;582(7813):557–60.

- Chia PY, Coleman KK, Tan YK, Ong SWX, Gum M, Lau SK, et al. Detection of air and surface contamination by SARS-CoV-2 in hospital rooms of infected patients. Nat Commun. 2020 May 29;11(1):2800.

- Lednicky JA, Shankar SN, Elbadry MA, Gibson JC, Alam MM, Stephenson CJ, et al. Collection of SARS-CoV-2 Virus from the Air of a Clinic within a University Student Health Care Center and Analyses of the Viral Genomic Sequence. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2020;20(6):1167–71.

- Yang W, Elankumaran S, Marr LC. Concentrations and size distributions of airborne influenza A viruses measured indoors at a health centre, a day-care centre and on aeroplanes. J R Soc Interface. 2011 Aug 7;8(61):1176–84.

- Blachere FM, Lindsley WG, Pearce TA, Anderson SE, Fisher M, Khakoo R, et al. Measurement of airborne influenza virus in a hospital emergency department. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Feb 15;48(4):438–40.

- Bui VN, Nguyen TT, Nguyen-Viet H, Bui AN, McCallion KA, Lee HS, et al. Bioaerosol Sampling to Detect Avian Influenza Virus in Hanoi’s Largest Live Poultry Market. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2019 Mar 5;68(6):972–5.

- Cao G, Noti JD, Blachere FM, Lindsley WG, Beezhold DH. Development of an improved methodology to detect infectious airborne influenza virus using the NIOSH bioaerosol sampler. J Environ Monit. 2011 Nov 29;13(12):3321–8.

- Fabian P, McDevitt JJ, DeHaan WH, Fung ROP, Cowling BJ, Chan KH, et al. Influenza Virus in Human Exhaled Breath: An Observational Study. PLOS ONE. 2008 Jul 16;3(7):e2691.

- Lednicky J, Pan M, Loeb J, Hsieh H, Eiguren-Fernandez A, Hering S, et al. Highly efficient collection of infectious pandemic influenza H1N1 virus (2009) through laminar-flow water based condensation. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2016 Jul 2;50(7):i–iv.

- Prost K, Kloeze H, Mukhi S, Bozek K, Poljak Z, Mubareka S. Bioaerosol and surface sampling for the surveillance of influenza A virus in swine. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 2019;66(3):1210–7.

- Hermann JR, Hoff SJ, Yoon KJ, Burkhardt AC, Evans RB, Zimmerman JJ. Optimization of a Sampling System for Recovery and Detection of Airborne Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus and Swine Influenza Virus. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006 Jul;72(7):4811–8.

- Li J, Leavey A, Wang Y, O’Neil C, Wallace MA, Burnham CAD, et al. Comparing the performance of 3 bioaerosol samplers for influenza virus. Journal of Aerosol Science. 2018 Jan 1;115:133–45.

- Lindsley WG, Blachere FM, Davis KA, Pearce TA, Fisher MA, Khakoo R, et al. Distribution of Airborne Influenza Virus and Respiratory Syncytial Virus in an Urgent Care Medical Clinic. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2010 Mar 1;50(5):693–8.

- Lindsley WG, Blachere FM, Thewlis RE, Vishnu A, Davis KA, Cao G, et al. Measurements of Airborne Influenza Virus in Aerosol Particles from Human Coughs. PLOS ONE. 2010 Nov 30;5(11):e15100.

- Milton PF JJ McDevitt, EA Houseman, DK. Airborne influenza virus detection with four aerosol samplers using molecular and infectivity assays: considerations for a new infectious virus aerosol sampler. Indoor Air. 2009 Oct 1;19(5):433–41.

- Pan M, Bonny TS, Loeb J, Jiang X, Lednicky JA, Eiguren-Fernandez A, et al. Collection of Viable Aerosolized Influenza Virus and Other Respiratory Viruses in a Student Health Care Center through Water-Based Condensation Growth. mSphere. 2017 Oct 11;2(5):e00251-17.

- Wu Y, Shen F, Yao M. Use of gelatin filter and BioSampler in detecting airborne H5N1 nucleotides, bacteria and allergens. Journal of Aerosol Science. 2010 Sep 1;41(9):869–79.

- Boles C, Brown G, Nonnenmann M. Determination of murine norovirus aerosol concentration during toilet flushing. Sci Rep. 2021 Dec 7;11(1):23558.

- Bonifait L, Charlebois R, Vimont A, Turgeon N, Veillette M, Longtin Y, et al. Detection and Quantification of Airborne Norovirus During Outbreaks in Healthcare Facilities. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2015 Aug 1;61(3):299–304.

- Uhrbrand K, Schultz AC, Madsen AM. Exposure to Airborne Noroviruses and Other Bioaerosol Components at a Wastewater Treatment Plant in Denmark. Food Environ Virol. 2011 Dec 1;3(3):130–7.

- Gast RK, Mitchell BW, Holt PS. Detection of Airborne Salmonella enteritidis in the Environment of Experimentally Infected Laying Hens by an Electrostatic Sampling Device. avdi. 2004 Jan;48(1):148–54.

- Wan GH, Huang CG, Huang YC, Huang JP, Yang SL, Lin TY, et al. Surveillance of Airborne Adenovirus and Mycoplasma pneumoniae in a Hospital Pediatric Department. PLOS ONE. 2012 Mar 21;7(3):e33974.

- Mastorides SM, Oehler RL, Greene JN, Sinnott JT, Kranik M, Sandin RL. The Detection of Airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis Using Micropore Membrane Air Sampling and Polymerase Chain Reaction. CHEST. 1999 Jan 1;115(1):19–25.

- Van Droogenbroeck C, Van Risseghem M, Braeckman L, Vanrompay D. Evaluation of bioaerosol sampling techniques for the detection of Chlamydophila psittaci in contaminated air. Veterinary Microbiology. 2009 Mar 16;135(1):31–7.

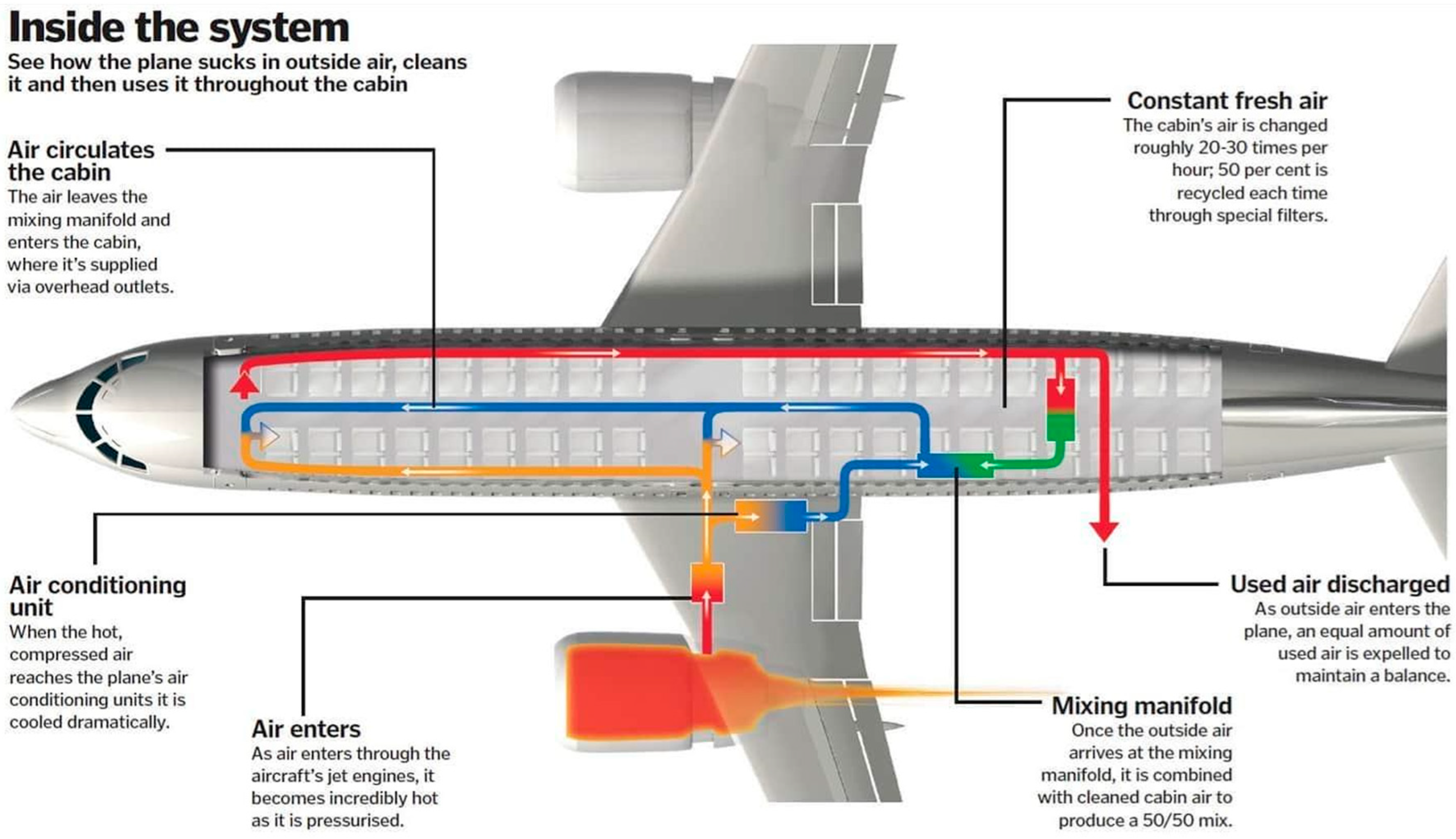

- Stuart Walkinshaw D. A Brief Introduction To Passenger Aircraft Cabin Air Quality. ASHRAE Journal. 2020 Oct;12–8.

- Conrad D. HEPA Filters: Keeping Cabin AIr Safe for Airlines [Internet]. PTI Technologies; 2020 Jun [cited 2023 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.ptitechnologies.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/HEPA-Filters-Keeping-Cabin-Air-Safe-For-Airlines-13-July-2020-reformatted.pdf.

- Lindsley WG. Filter Pore Size and Aerosol Sample Collection. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; 2016 Apr. (Manual of Analytical Methods (NMAM)). Report No.: 5th Edition.

- Burton NC, Grinshpun SA, Reponen T. Physical Collection Efficiency of Filter Materials for Bacteria and Viruses. The Annals of Occupational Hygiene. 2007 Mar 1;51(2):143–51.

- Mbareche H, Veillette M, Bilodeau GJ, Duchaine C. Bioaerosol Sampler Choice Should Consider Efficiency and Ability of Samplers To Cover Microbial Diversity. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2018 Nov 15;84(23):e01589-18.

- Tseng CC, Li CS. Collection efficiencies of aerosol samplers for virus-containing aerosols. Journal of Aerosol Science. 2005 May 1;36(5):593–607.

- Verreault D, Rousseau GM, Gendron L, Massé D, Moineau S, Duchaine C. Comparison of Polycarbonate and Polytetrafluoroethylene Filters for Sampling of Airborne Bacteriophages. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2010 Feb 10;44(3):197–201.

- Gendron L, Verreault D, Veillette M, Moineau S, Duchaine C. Evaluation of Filters for the Sampling and Quantification of RNA Phage Aerosols. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2010 Aug 9;44(10):893–901.

- Borges JT, Nakada LYK, Maniero MG, Guimarães JR. SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review of indoor air sampling for virus detection. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021;28(30):40460–73.

- Choi DY, Heo KJ, Kang J, An EJ, Jung SH, Lee BU, et al. Washable antimicrobial polyester/aluminum air filter with a high capture efficiency and low pressure drop. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2018 Jun 5;351:29–37.

- Zhen H, Han T, Fennell DE, Mainelis G. Release of Free DNA by Membrane-Impaired Bacterial Aerosols Due to Aerosolization and Air Sampling. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2013 Dec 15;79(24):7780–9.

- Mainelis G, Tabayoyong M. The Effect of Sampling Time on the Overall Performance of Portable Microbial Impactors. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2010 Jan 1;44(1):75–82.

- Wang Z, Reponen T, A. Grinshpun S, L. Górny R, Willeke K. Effect of sampling time and air humidity on the bioefficiency of filter samplers for bioaerosol collection. Journal of Aerosol Science. 2001 May 1;32(5):661–74.

- Hinds WC, Zhu Y. Aerosol Technology: Properties, Behavior, and Measurement of Airborne Particles. John Wiley & Sons; 2022. 452 p.

- Gerone PJ, Couch RB, Keefer GV, Douglas RG, Derrenbacher EB, Knight V. Assessment of experimental and natural viral aerosols. Bacteriological Reviews. 1966 Sep;30(3):576–88.

- Stewart SL, Grinshpun SA, Willeke K, Terzieva S, Ulevicius V, Donnelly J. Effect of impact stress on microbial recovery on an agar surface. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1995 Apr;61(4):1232–9.

- Harstad JB. Sampling Submicron T1 Bacteriophage Aerosols. Applied Microbiology. 1965 Nov;13(6):899–908.

- Lin X, Reponen T, Willeke K, Wang Z, Grinshpun SA, Trunov M. Survival of Airborne Microorganisms During Swirling Aerosol Collection. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2000 Mar;32(3):184–96.

- Lemieux J, Veillette M, Mbareche H, Duchaine C. Re-aerosolization in liquid-based air samplers induces bias in bacterial diversity. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2019 Nov 2;53(11):1244–60.

- Tseng CC, Hsiao PK, Chang KC, Chen WT, Yiin LM, Hsieh CJ. Optimization of Propidium Monoazide Quantitative PCR for Evaluating Performances of Bioaerosol Samplers for Sampling Airborne Staphylococcus aureus. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2014 Dec 2;48(12):1308–19.

- McFarland AR, Haglund JS, King MD, Hu S, Phull MS, Moncla BW, et al. Wetted Wall Cyclones for Bioaerosol Sampling. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2010 Feb 25;44(4):241–52.

- Berry CM. An Electrostatic Method for Collecting Bacteria from Air. Public Health Reports (1896-1970). 1941;56(42):2044–51.

- Degois J, Dubuis ME, Turgeon N, Veillette M, Duchaine C. Condensation sampler efficiency for the recovery and infectivity preservation of viral bioaerosols. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2021 Jun 3;55(6):653–64.

- Hering SV, Stolzenburg MR. A Method for Particle Size Amplification by Water Condensation in a Laminar, Thermally Diffusive Flow. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2005 May 1;39(5):428–36.

- Hering SV, Spielman SR, Lewis GS. Moderated, Water-Based, Condensational Particle Growth in a Laminar Flow. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2014 Apr 3;48(4):401–8.

- Lednicky J, Pan M, Loeb J, Hsieh H, Eiguren-Fernandez A, Hering S, et al. Highly efficient collection of infectious pandemic influenza H1N1 virus (2009) through laminar-flow water based condensation. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2016 Jul 2;50(7):i–iv.

- Nieto-Caballero M, Savage N, Keady P, Hernandez M. High fidelity recovery of airborne microbial genetic materials by direct condensation capture into genomic preservatives. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2019 Feb 1;157:1–3.

- Pan M, Carol L, Lednicky JA, Eiguren-Fernandez A, Hering S, Fan ZH, et al. Determination of the distribution of infectious viruses in aerosol particles using water-based condensational growth technology and a bacteriophage MS2 model. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2019 May 4;53(5):583–93.

- Pan M, Eiguren-Fernandez A, Hsieh H, Afshar-Mohajer N, Hering S v., Lednicky J, et al. Efficient collection of viable virus aerosol through laminar-flow, water-based condensational particle growth. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2016;120(3):805–15.

- Eiguren-Fernandez A, Lewis GS, Spielman SR, Hering SV. Time-resolved characterization of particle associated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons using a newly-developed sequential spot sampler with automated extraction and analysis. Atmospheric Environment. 2014 Oct 1;96:125–34.

- Guo J, Xiong Y, Kang T, Xiang Z, Qin C. Bacterial community analysis of floor dust and HEPA filters in air purifiers used in office rooms in ILAS, Beijing. Sci Rep. 2020 Apr 14;10(1):6417.

- King P, Pham LK, Waltz S, Sphar D, Yamamoto RT, Conrad D, et al. Longitudinal Metagenomic Analysis of Hospital Air Identifies Clinically Relevant Microbes. PLOS ONE. 2016 Aug 2;11(8):e0160124.

- Meadow JF, Altrichter AE, Kembel SW, Kline J, Mhuireach G, Moriyama M, et al. Indoor airborne bacterial communities are influenced by ventilation, occupancy, and outdoor air source. Indoor Air. 2014;24(1):41–8.

- Whon TW, Kim MS, Roh SW, Shin NR, Lee HW, Bae JW. Metagenomic Characterization of Airborne Viral DNA Diversity in the Near-Surface Atmosphere. J Virol. 2012 Aug;86(15):8221–31.

- Rosario K, Fierer N, Miller S, Luongo J, Breitbart M. Diversity of DNA and RNA Viruses in Indoor Air As Assessed via Metagenomic Sequencing. Environ Sci Technol. 2018 Feb 6;52(3):1014–27.

- Prussin AJ, Garcia EB, Marr LC. Total Virus and Bacteria Concentrations in Indoor and Outdoor Air. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2015;2(4):84–8.

- Fang Z, Ouyang Z, Zheng H, Wang X. Concentration and Size Distribution of Culturable Airborne Microorganisms in Outdoor Environments in Beijing, China. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2008 Mar 31;42(5):325–34.

- Wang S, Liu W, Li J, Sun H, Qian Y, Ding L, et al. Seasonal Variation Characteristics of Bacteria and Fungi in PM2.5 in Typical Basin Cities of Xi’an and Linfen, China. Atmosphere. 2021 Jul;12(7):809.

- Ho HM, Rao CY, Hsu HH, Chiu YH, Liu CM, Chao HJ. Characteristics and determinants of ambient fungal spores in Hualien, Taiwan. Atmospheric Environment. 2005 Oct 1;39(32):5839–50.

- Fahlgren C, Hagström Å, Nilsson D, Zweifel UL. Annual Variations in the Diversity, Viability, and Origin of Airborne Bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010 May;76(9):3015–25.

- Tanaka D, Terada Y, Nakashima T, Sakatoku A, Nakamura S. Seasonal variations in airborne bacterial community structures at a suburban site of central Japan over a 1-year time period using PCR-DGGE method. Aerobiologia. 2015 Jun 1;31(2):143–57.

- Yan D, Zhang T, Su J, Zhao LL, Wang H, Fang XM, et al. Diversity and Composition of Airborne Fungal Community Associated with Particulate Matters in Beijing during Haze and Non-haze Days. Frontiers in Microbiology [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2022 Dec 6];7. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00487.

- Goudarzi G, Shirmardi M, Khodarahmi F, Hashemi-Shahraki A, Alavi N, Ankali KA, et al. Particulate matter and bacteria characteristics of the Middle East Dust (MED) storms over Ahvaz, Iran. Aerobiologia. 2014 Dec 1;30(4):345–56.

- Fang Z, Yao W, Lou X, Hao C, Gong C, Ouyang Z. Profile and Characteristics of Culturable Airborne Bacteria in Hangzhou, Southeast of China. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2016;16(7):1690–700.

- Serrano-Silva N, Calderón-Ezquerro MC. Metagenomic survey of bacterial diversity in the atmosphere of Mexico City using different sampling methods. Environmental Pollution. 2018 Apr 1;235:20–9.

- Emory A, Light F. EPA Needs to Fulfill Its Designated Responsibilities to Ensure Effective BioWatch Program [Internet]. 2005 Mar p. 27. Report No.: 2005-P-00012. Available from: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-12/documents/20050323-2005-p-00012.pdf.

- United States Government Accountability Office. Biodefense: DHS Exploring New Methods to Replace BioWatch and Could Benefit from Additional Guidance. 2021 May. Report No.: GAO-21-292.

- Bonetta Sa, Bonetta Si, Mosso S, Sampò S, Carraro E. Assessment of microbiological indoor air quality in an Italian office building equipped with an HVAC system. Environ Monit Assess. 2010 Feb 1;161(1):473–83.

- Farnsworth JE, Goyal SM, Kim SW, Kuehn TH, Raynor PC, Ramakrishnan MA, et al. Development of a method for bacteria and virus recovery from heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) filters. J Environ Monit. 2006 Oct 5;8(10):1006–13.

- Maestre JP, Jennings W, Wylie D, Horner SD, Siegel J, Kinney KA. Filter forensics: microbiota recovery from residential HVAC filters. Microbiome. 2018 Jan 30;6(1):22.

- Stanley NJ, Kuehn TH, Kim SW, Raynor PC, Anantharaman S, Ramakrishnan MA, et al. Background culturable bacteria aerosol in two large public buildings using HVAC filters as long term, passive, high-volume air samplers. J Environ Monit. 2008 Apr;10(4):474–81.

- Hoisington AJ, Maestre JP, King MD, Siegel JA, Kinney KA. Impact of sampler selection on the characterization of the indoor microbiome via high-throughput sequencing. Building and Environment. 2014 Oct 1;80:274–82.

- Noris F, Siegel JA, Kinney KA. Evaluation of HVAC filters as a sampling mechanism for indoor microbial communities. Atmospheric Environment. 2011 Jan 1;45(2):338–46.

- Goyal SM, Anantharaman S, Ramakrishnan MA, Sajja S, Kim SW, Stanley NJ, et al. Detection of viruses in used ventilation filters from two large public buildings. American Journal of Infection Control. 2011 Sep 1;39(7):e30–8.

- Leung MHY, Wilkins D, Li EKT, Kong FKF, Lee PKH. Indoor-Air Microbiome in an Urban Subway Network: Diversity and Dynamics. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014 Nov;80(21):6760–70.

| 1 | Passive air sampling is a branch of air sampling that depends on natural settling of particles. Methods for passive sampling include surface dust collection (e.g., vacuuming), settle plates, and adhesive tape. |

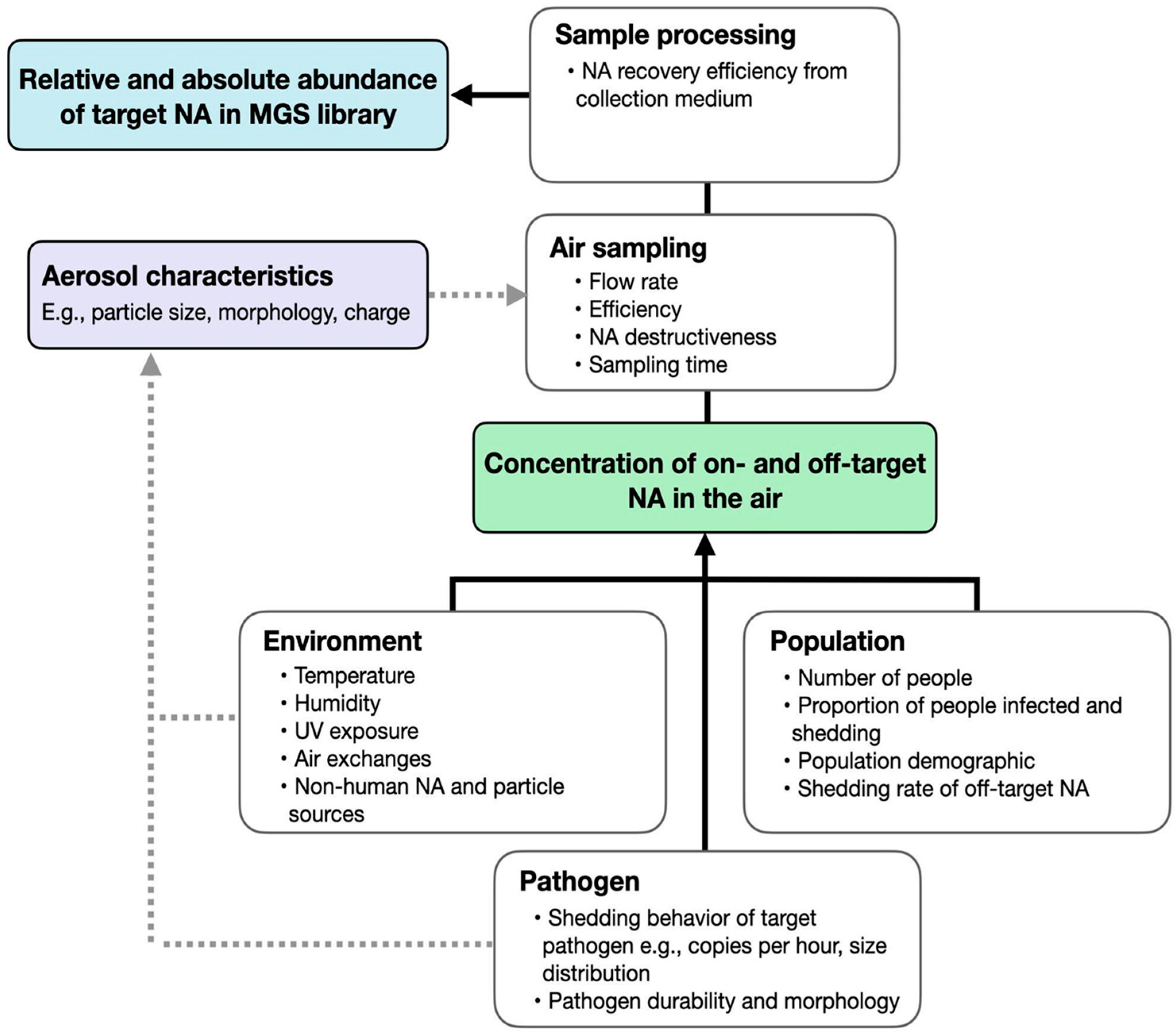

| 2 | For example, with filter-based sampling methods, a trade-off exists between higher flow rates and increased destructiveness. The rapid air flow induces mechanical stress, leading to the destruction of microbes and damage to nucleic acids. Furthermore, while filter-based approaches can attain high capture efficiency for the small particle sizes typical of viral aerosols, this efficiency imposes restrictions on the flow rate. Similar compromises are observed across other categories of samplers, as detailed in Appendix 1. |

| 3 | For example, an electrostatic precipitator might deposit particles into a liquid medium, or a condensation sampler might have an initial filter to remove larger particles. |

| 4 | Microbes were counted using the SYBR Gold fluorescence dye to stain nucleic acid. Fluorescent particles between 0.02 and 0.50 μm were counted as VCPs and those between 0.50 and 5.00 μm as BCPs. |

| 5 | A simple BOTEC suggests that eight hours of air sampling in an indoor environment with typical bacteria and virus concentrations at 200 L/min would yield about 300 ng of NA (Appendix 5). |

| 6 | In reality, “inertia” is too simple a concept to characterize the movement of particles along streamlines. A particle’s Stokes number provides a more rigorous explanation of its behavior (56). |

| 7 | A large pressure drop like that caused by a filter with a small effective pore size requires more power to push air through the pressure interface. |

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Flow rate | How quickly air can be moved through the device (L/min). Higher flow rates allow faster collection of material and larger/more frequent samples. |

| Collection efficiency | The fraction of particles passing through the sampler that is collected. Typically rated for particular size ranges, e.g., a MERV 13 filter is at least 85% efficient at capturing particles between 1 µm to 3 µm in diameter. |

| Recovery efficiency | The fraction of collected NA that can be recovered from the collection mechanism. |

| Destructiveness (viability) | The degree to which the air sampler desiccates or otherwise kills microbes such that they can no longer be cultured. Critical for culture-based surveillance, less important for sequencing-based surveillance. |

| Destructiveness (fragmentation) | The degree to which an air sampler damages microbial NA through fragmentation or degradation, resulting in the loss of NA in the sample or shorter fragment lengths for sequencing. |

| Cost | Up-front and per-sample costs of buying and using the device. |

| Practicality | Size of sampler, ease of deployment, noise level, etc. |

| Axes | Air sampling | Wastewater sampling |

|---|---|---|

| Sample collection | Technically challenging with inherent tradeoffs among desirable sampler qualities. Slow to collect NA. |

Trivial at wastewater treatment plants (WWTP), though sampling at triturators or individual buildings may require custom pipe modifications. Small samples can provide large amounts of NA. |

| Sample complexity | Relatively low number of unique taxa (typically <1000) in indoor air, and low (<1%) abundance of viral NA from human hosts. | Uncertain, but seems to have more unique taxa and possibly a lower abundance of viral NA from human hosts. |

| Pathogen coverage | Well suited to detect airborne pathogens which are an important part of the threat space. | Well suited to detect fecal-oral pathogens and also many respiratory pathogens. Probably less robust across respiratory pathogens. |

| Catchment area | Effective surveillance of human pathogens is limited to building-level catchment areas. | Sampling from WWTPs provides city-level pathogen surveillance. |

| Composite traveler samples | Can monitor individual airplanes or airport terminals. | Can collect individual or aggregate airplane samples, as well as airport terminal waste. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).