Introduction

Liver carcinoma represents a major global health challenge, of which hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the predominant form. HCC is the fourth leading cause of cancer-associated mortality worldwide [

1]. Sorafenib, a multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is pivotal in HCC management [

2]. Additionally, the combined administration of atezolizumab and bevacizumab has emerged as an innovative therapeutic strategy to support the patient’s immune system and limit tumor angiogenesis and growth [

3]. These therapeutic avenues underscore the importance of multi-targeted approaches in treating patients with HCC.

Despite promising results in clinical trials, the above treatments are efficacious for only a subset of patients. Thus, the situation underscores the importance of identifying the HCC molecular signatures to enable the tailoring of the most appropriate therapeutic regimens. Recent research introduced a novel cancer treatment modality that combines pro-senescence drugs with senolytics [

4], which shed light on the therapeutic promise of the cellular senescence (CS) phenotype in tumor management. While identifying senescent traits across various diseases can guide clinical interventions, describing senescence features in various tumors is still being explored and investigated.

CS represents a stress response aimed at eliminating superfluous, damaged, or aberrant cells. This phenomenon involves the persistent cessation of cell proliferation accompanied by pro-inflammatory mediator secretion, which is commonly known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [

5]. Initial studies described the tumor-suppressive properties of CS predicated on its capacity to inhibit tumorigenic proliferation [

6]. However, emerging evidence underscored the paradoxical role of senescence in promoting cancer progression through SASP-mediated intercellular interactions [

7]. Specifically, the tumorigenic promotion of specific SASP components has been highlighted. For example, IL-6 and IL-8 are prevalent within the SASP [

8] and are cancer cell proliferation drivers. CCL5 amplifies tumorigenic proliferation by modulating c-MYC and cyclin D1 [

9]. Furthermore, CXCL5 and VEGF augmented vascular density in heterograft tumor models[

10].

Beyond angiogenesis, the SASP milieu fosters cell motility and invasion, intensifying cancer cell invasive capacity and facilitating metastatic dissemination [

11,

12]. Concurrently, clinical trials investigating senolytics (a therapeutic cocktail comprising dasatinib and quercetin designed for selective senescent cell extermination) demonstrated potential for alleviating age-associated pathologies and extending the lifespan in experimental animals [

13]. However, concerns regarding the specificity and deleterious adverse effects of senescent cell clearance via senolytics moderate their therapeutic promise [

14]. Thus, the clinical benefits of senescence-based interventions currently remain elusive. Delineating senescence signatures in HCC could provide pivotal insights for therapeutic strategizing.

In this study, a preliminary analysis was conducted using both bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and single-cell RNA (scRNA) datasets to improve understanding of HCC senescence signatures. The approach successfully pinpointed the HCC-specific senescence pathways. Specific genes from these pathways were used to construct two predictive models using machine learning algorithms. These models were designed to robustly evaluate the associations between varying degrees of senescence signatures and the clinical and molecular biological traits of patients with HCC.

Collectively, this study revealed the pivotal senescence markers in HCC and established insights to construct reliable prediction frameworks. Serendipitously, this study also discovered a novel HCC senescence marker. Overall, the findings potentially contribute to personalized therapeutic strategies and prognostic assessments. The results provide valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms of HCC development and can guide future clinical research and drug development.

Discussion

HCC represents a highly heterogeneous malignancy characterized by diverse pathogenic determinants and an increased incidence rate. Contemporary postoperative outcomes for patients with HCC remain less than optimal. A significant proportion of patients with HCC exhibit reduced susceptibility to multi-target receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which are exemplified by PD-1/PD-L1 antagonists. This proportion underscores the importance of precisely identifying a prognostic biomarker to inform therapeutic decisions. A pivotal cellular phenomenon in senescence and tumorigenesis in HCC, CS warrants elucidation, specifically regarding the molecular characteristics of senescence, immune profiles, clinical manifestations, and treatment responsiveness.

Based on the above, a scoring metric predicated on mRNA expression landscapes in HCC was devised in the present study. The metric facilitated correlations between senescent molecular subtypes and the genomic, immune, and clinical spectra in patients with HCC. Significantly, risk stratification using CS features proficiently predicted patient outcomes and revealed directions for therapy. Collectively, the findings present a comprehensive paradigm to understand the CS-associated markers in HCC, catalyzing further investigations and biomarker discovery.

The present study identified the HCC-specific senescence-associated pathways. While numerous senescence-centric pathways demonstrated differential significance, only three signaling pathways were significant following integrated single-cell data and GSEA screening. Earlier investigations explored the senescence hallmark pathways in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. However, the defined pathways markedly differed from those in the present study, which highlighted the distinctive molecular nuances of senescence in dissimilar tumors [

15].

Concurrent studies on prostate cancer examined its molecular heterogeneity and immune milieu dynamism, where three CS genes with prognostic potential were isolated [

16]. Aligning with these insights, the present study also constructed a multi-gene model for HCC as a prospective tool for predicting prognoses and evaluating therapeutic responses. The results suggested the intrinsic flexibility of senescence attributes across tumor types, likely modulated by the inherent traits of the tumor and the surrounding immune environment. A profound understanding of senescence attributes can inspire a more refined understanding of senescence mechanisms across diverse malignancies, thereby refining prognostic evaluations and tailoring therapeutic interventions for HCC.

The molecular biological variances across diverse senescence subgroups were investigated, where distinctions in signaling pathways and variations in tumor characteristic expression were emphasized. Numerous senescence features mirror those of cancer. However, their interplay in tumorigenesis remains debated. The common hallmarks shared by senescence and cancer include genomic instability, epigenetic alterations, persistent inflammation, and ecological dysregulation, collectively referred to as “meta-features”. Despite lacking direct counterparts in cancer, certain senescence features (impaired protein homeostasis, mitochondrial dysfunction, and altered intercellular communication) are also considered detrimental factors that contribute to tumor progression. Interestingly, other specific senescence features, such as telomere attrition and stem cell exhaustion, counteract the emergence of cancer hallmarks, including infinite replicative potential and phenotypic versatility, thereby acting as antagonistic attributes.

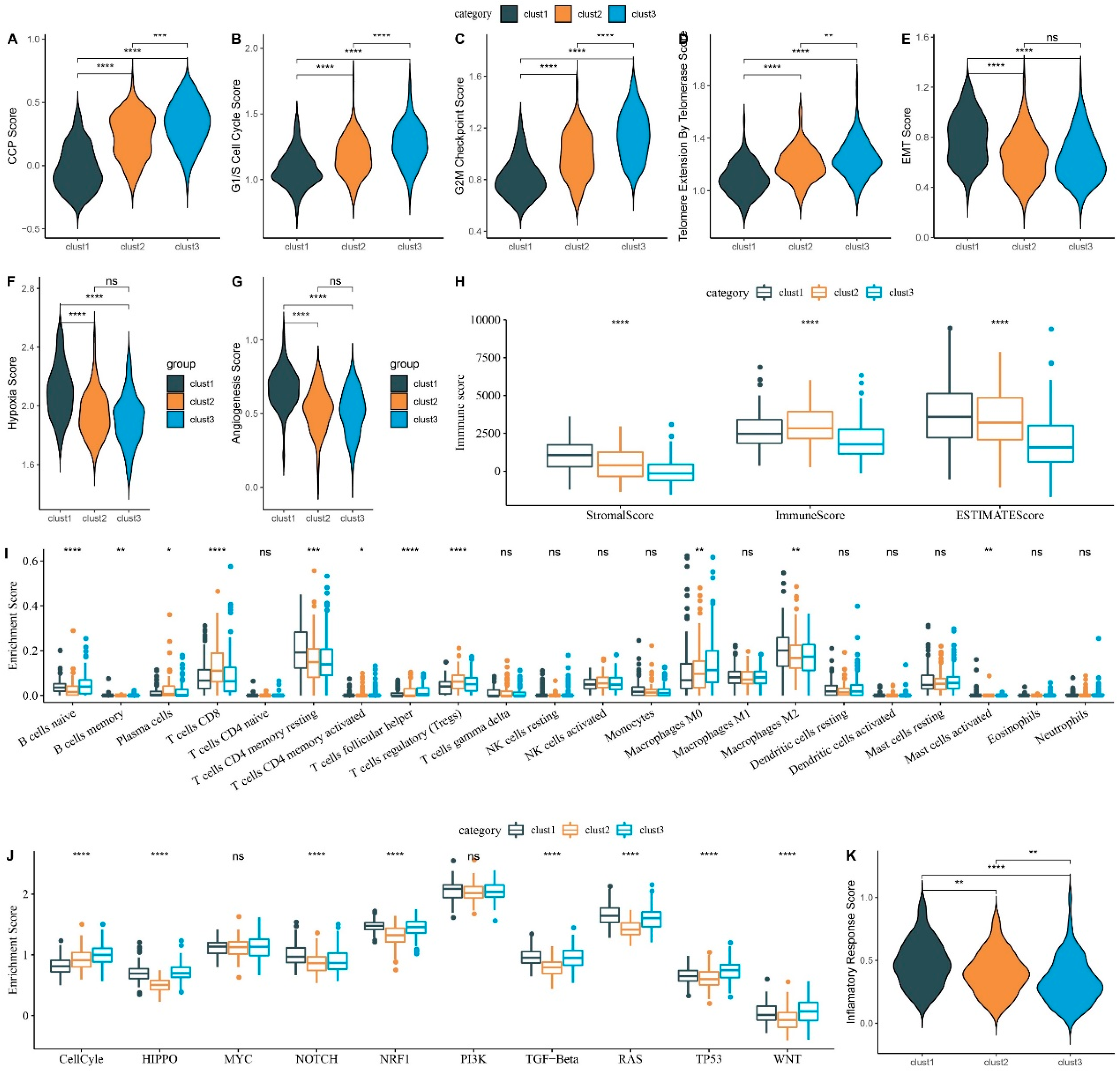

The findings revealed that Cluster 3 exhibited a significantly poorer prognosis. Simultaneously, malignant features such as cell cycle scored higher in Cluster 3. However, Cluster 3 had lower levels of other characteristics, such as EMT and vascular formation. Interestingly, although these results appear contradictory, similar patterns were identified when analyzing the senescence subtypes in other tumors [

17]. Moreover, two other senescence characteristics have been highlighted: disabled macroautophagy and CS, whose tumor-suppressive and tumor-promoting roles are environment-dependent [

18]. Therefore, it is suggested that senescence does not always promote the malignancy process in tumors. By selectively inhibiting the detrimental functions of senescence and amplifying the beneficial effects of CS, it might be possible to offset the adverse factors associated with senescence in tumor treatment. Thus, the heterogeneity in malignant attributes across senescence subgroups highlights the potential of stratifying HCC based on senescence phenotypes.

Senescence-associated molecular characteristics were systematically quantified in HCC to define their clinical implications. The resultant quantified attributes were then encapsulated into a risk score metric. The primary focus was to discern correlations between risk scores extrapolated from these senescence molecular markers and pivotal clinical indices: patient prognosis, intricate pathological nuances, and oncological pharmacotherapy responsiveness. A cross-sectional data analysis underscored discernible variations in the senescence risk score when compared across a spectrum of pathological gradations and histopathological echelons. Remarkably, the prognostic algorithm demonstrated substantial precision in predicting the clinical course of patients with HCC. Furthermore, the risk score established its position as a standalone prognostic biomarker, a claim substantiated across diverse HCC cohorts, thereby cementing the robustness of the investigative outcomes.

Notably, in clinical practice, the judicious selection of therapeutic agents is paramount for overcoming drug resistance, augmenting objective response rates (ORR), and enhancing overall survival, particularly in patients with advanced HCC. Phase III trials that examined sorafenib reported that the ORR defined by the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) was 10%–15% [

19]. Contrastingly, lenvatinib-treated patients had an ORR of 24.1% [

20]. In this context, the potential of a senescence risk score to prognosticate drug efficacies in HCC cohorts was evaluated. The analysis results highlighted that patients in the high-risk scores group had heightened susceptibility to established chemotherapeutic agents, exemplified by cisplatin. Developing the senescence risk quantifier could potentially revolutionize therapeutic stratification, particularly for patients in advanced disease stages or with bleak prognostic outlooks, thereby facilitating enhanced clinical resolutions.

The applications of the senescence risk score also extend to immunotherapy. Notably, the CheckMate-040 trial [

1], which spotlighted nivolumab as a monotherapeutic agent, heralded a new era in HCC immunotherapy. The idea was echoed by the subsequent KEYNOTE-224 study that underscored the therapeutic ability of pembrolizumab in the HCC therapeutic landscape [

21]. Despite the advances in ICIs, monotherapeutic ICI paradigms, particularly those using PD-1/PD-L1, have not achieved their envisioned therapeutic peak. Hence, augmenting ICI therapeutic outcomes through novel regimens remains imperative.

The preliminary insights of the present study highlight the prognostic potential of the risk score in immunotherapeutic cohorts. Alarmingly, patients categorized as high-risk had a suboptimal clinical prognosis post-immunotherapy. This finding suggested the necessity of an exhaustive clinical appraisal of this cohort to delineate optimal therapeutic strategies. Based on the abovementioned findings and discussions, it is cautiously posited that formulating a senescence risk scoring system is promising for augmenting the efficacy of existing therapies for patients with HCC.

In the present study, the importance of identifying G6PD as an HCC biomarker in CS is reiterated. The fundamental role of G6PD is to provide adequate reducing power essential for growth and maintaining redox homeostasis[

22]. Recent investigations revealed G6PD involvement in various cellular processes beyond red blood cell diseases through redox signaling[

23,

24]. G6PD activity deficiency impairs antioxidant defense mechanisms and disrupts cell signal transduction. Furthermore, dysregulated G6PD activation has been linked to tumor initiation and progression towards malignancy. Previous studies elucidated the substantial roles of G6PD in regulating apoptosis, STAT3- and STAT5-mediated tumorigenesis[

25], colon cancer metastasis[

26], and p53-mutated cancers[

27]. However, while some prior findings suggested that G6PD involvement in different signaling pathways promoted HCC progression, its specific role as a CS marker in liver cancer cells remains elusive.

Consequently, the present study validated the significance of G6PD as an essential biomarker within the HCC senescence model and substantiated its influence on the malignant features of HCC tumor cells. These findings were supported across multiple HCC cohorts and by molecular biology experiments. Thus, investigations focusing on delineating the role of G6PD in senescence would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of its functional implications in HCC.

Despite preliminary data revealing the relationship between the CS score and HCC clinical outcomes, immune therapy, and chemotherapy sensitivity, the study limitations must be acknowledged. First, defining the senescence characteristics of patients with HCC relies on their transcriptome information. Research incorporating additional omics data, including proteomics and genomics, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the senescence features in such patients. Furthermore, the fact that the cohorts currently undergoing immune therapy in the studies were not derived from an HCC cohort might have affected the immune therapy effects.

In summary, HCC-specific senescence-related pathways were investigated, and two prognostic models were developed using genes associated with these pathways. The risk model, which characterizes senescence in HCC, exhibited robust predictive efficacy. Specifically, the risk score effectively guided the clinical outcomes of patients with HCC and potentially assessed the degree of immune cell infiltration, guided clinical drug usage, and evaluated immune therapy effectiveness. As a foundation for precise prognosis prediction in patients with HCC, the risk score is a new quantitative evaluation method for the CS level in HCC and aids in developing personalized treatment plans.

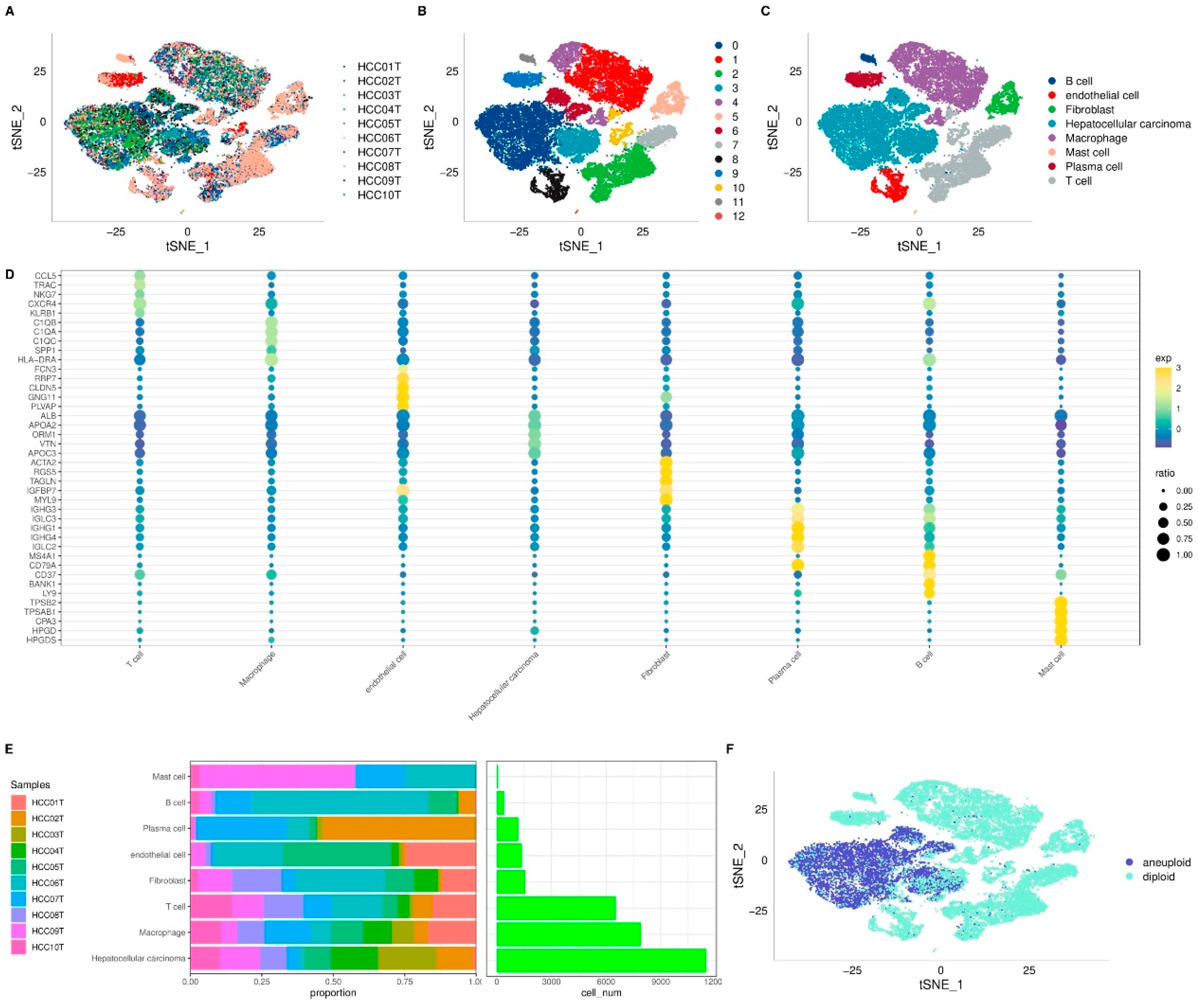

Figure 1.

Visualization and Annotation of Cell Subgroups. t-SNE plot of sample distribution (A), clustered subgroups (B), and annotated cell distribution (C). D. Dot plot of marker gene expression in annotated subgroups. E. Proportions and cell numbers of annotated subgroups. F. Malignant and non-malignant cell distribution.

Figure 1.

Visualization and Annotation of Cell Subgroups. t-SNE plot of sample distribution (A), clustered subgroups (B), and annotated cell distribution (C). D. Dot plot of marker gene expression in annotated subgroups. E. Proportions and cell numbers of annotated subgroups. F. Malignant and non-malignant cell distribution.

Figure 2.

Identification of Senescence-related Pathways in HCC. A. Single-cell analysis reveals differential senescence-related pathways through gene set variation analysis (GSVA). B. GSEA results for senescence-related pathways in bulk data. C. Comparison of ssGSEA scores for senescence-related pathways in bulk data. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Identification of Senescence-related Pathways in HCC. A. Single-cell analysis reveals differential senescence-related pathways through gene set variation analysis (GSVA). B. GSEA results for senescence-related pathways in bulk data. C. Comparison of ssGSEA scores for senescence-related pathways in bulk data. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

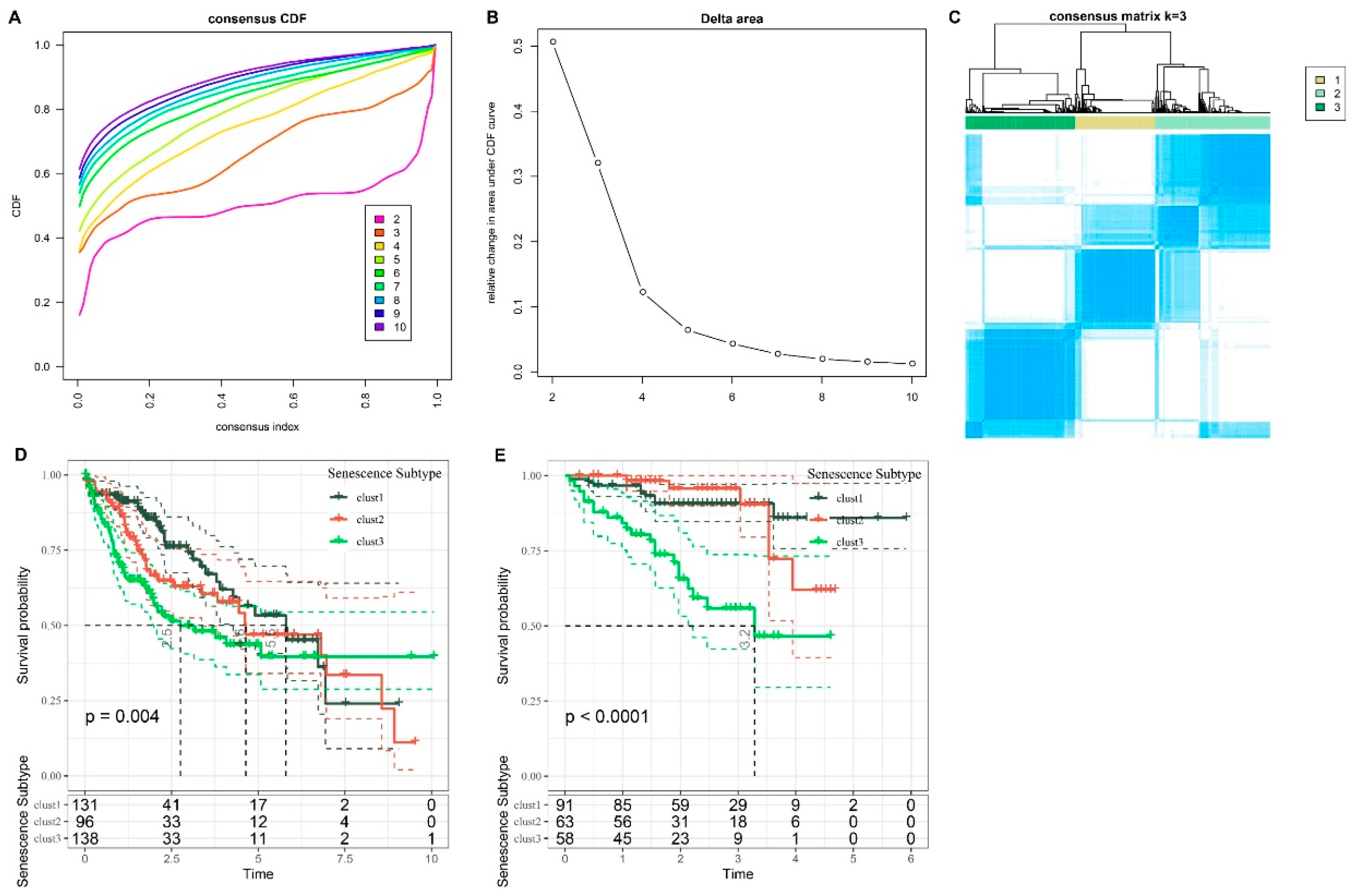

Figure 3.

Analysis of Subtypes and Prognostic Implications in HCC cohorts. A. CDF curve for LIHC cohort. B. Change in area curve from consensus clustering analysis. C. Visualization of sample groupings at k = 3 through a heatmap. D. KM survival curve demonstrating the outcomes of three distinct subtypes within TCGA-LIHC cohort. E. KM survival curve illustrating the prognosis of three subtypes in the HCCDB18 cohort.

Figure 3.

Analysis of Subtypes and Prognostic Implications in HCC cohorts. A. CDF curve for LIHC cohort. B. Change in area curve from consensus clustering analysis. C. Visualization of sample groupings at k = 3 through a heatmap. D. KM survival curve demonstrating the outcomes of three distinct subtypes within TCGA-LIHC cohort. E. KM survival curve illustrating the prognosis of three subtypes in the HCCDB18 cohort.

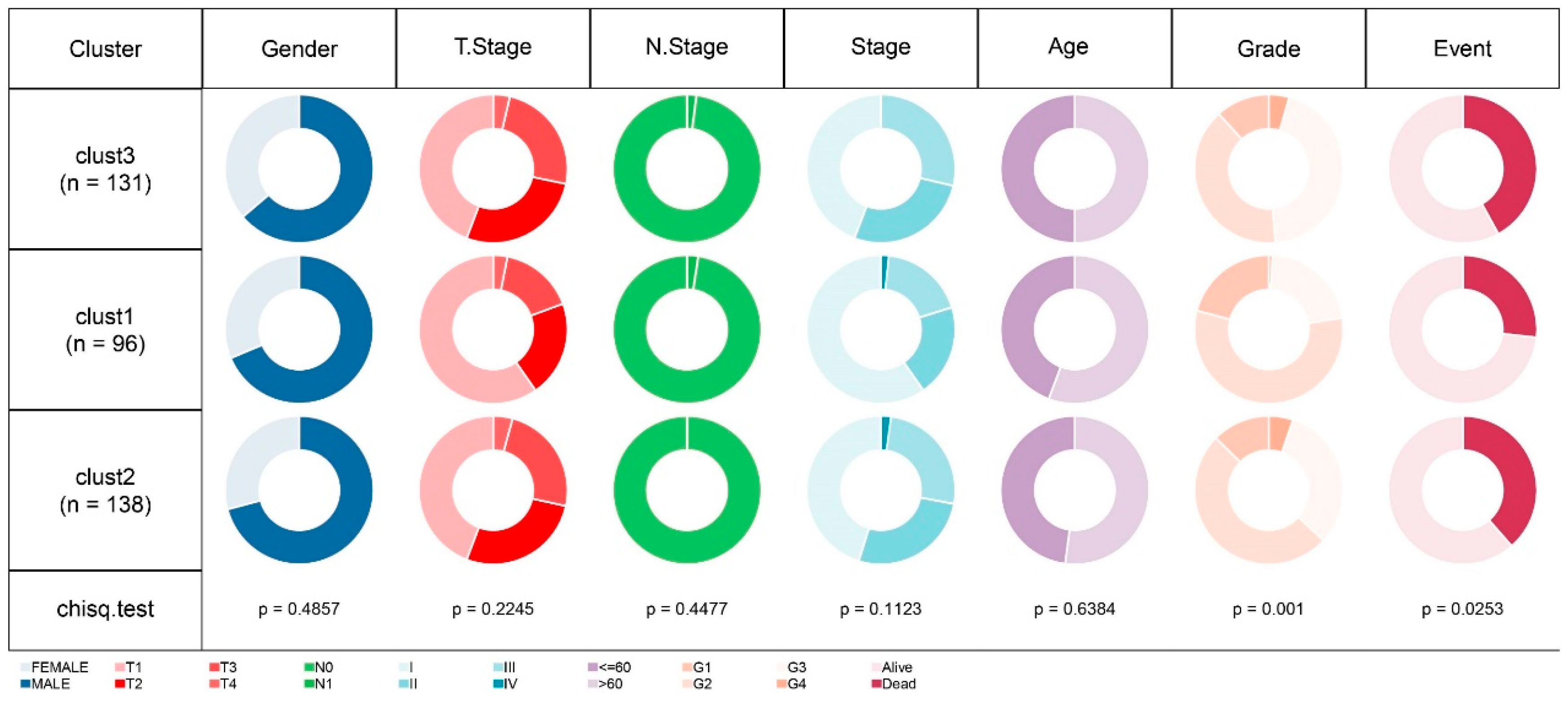

Figure 4.

Comparative Analysis of Clinical Feature Distribution Among Molecular Subtypes in TCGA-LIHC Cohort.

Figure 4.

Comparative Analysis of Clinical Feature Distribution Among Molecular Subtypes in TCGA-LIHC Cohort.

Figure 5.

Comparative Analysis of Scores Across Three Subtypes in TCGA-LIHC Dataset. A. CCP scores. B. G1/S phase scores. C. G2M checkpoint scores. D. Telomerase extension scores. E. EMT scores. F. Hypoxia scores. G. Angiogenesis scores. H. Immune scores (ESTIMATE algorithm). I. 22 Immune cell type scores (CIBERSORT algorithm). J. Ten pathway-related tumor scores. K. Inflammatory factor scores. ns, p ≥ 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

Comparative Analysis of Scores Across Three Subtypes in TCGA-LIHC Dataset. A. CCP scores. B. G1/S phase scores. C. G2M checkpoint scores. D. Telomerase extension scores. E. EMT scores. F. Hypoxia scores. G. Angiogenesis scores. H. Immune scores (ESTIMATE algorithm). I. 22 Immune cell type scores (CIBERSORT algorithm). J. Ten pathway-related tumor scores. K. Inflammatory factor scores. ns, p ≥ 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 6.

CNV and SNV Mutation Analysis. Peak plot of CNV in cluster1 subtype (A), cluster2 subtype (B), and cluster3 subtype (C). D. Waterfall plot of top 15 genes with SNV mutations among subtypes.

Figure 6.

CNV and SNV Mutation Analysis. Peak plot of CNV in cluster1 subtype (A), cluster2 subtype (B), and cluster3 subtype (C). D. Waterfall plot of top 15 genes with SNV mutations among subtypes.

Figure 7.

Differential Gene Screening Among Three Subtypes and Risk Model Construction. Volcano plot for differential analysis of cluster1 vs. no_cluster1 (A), cluster2 vs. no_cluster2 (B), and cluster3 vs. no_cluster3 (C). D. Identification of 729 candidates among differentially expressed genes. E. Trajectory of each independent variable as lambda changes. F. Confidence interval under lambda. G. Coefficients of the seven genes in the model. H. Western blot assay to evaluate G6PD protein expression in HepG2 cells. I. Colony formation assay to evaluate HepG2 cell proliferation. J-K. Transwell assay assesses HepG2 cell migration (J) and invasion (K). *p < 0.05.

Figure 7.

Differential Gene Screening Among Three Subtypes and Risk Model Construction. Volcano plot for differential analysis of cluster1 vs. no_cluster1 (A), cluster2 vs. no_cluster2 (B), and cluster3 vs. no_cluster3 (C). D. Identification of 729 candidates among differentially expressed genes. E. Trajectory of each independent variable as lambda changes. F. Confidence interval under lambda. G. Coefficients of the seven genes in the model. H. Western blot assay to evaluate G6PD protein expression in HepG2 cells. I. Colony formation assay to evaluate HepG2 cell proliferation. J-K. Transwell assay assesses HepG2 cell migration (J) and invasion (K). *p < 0.05.

Figure 8.

Performance Evaluation of Seven-gene Risk Models from TCGA, HCCDB18, and GSE76427 Datasets. A–C. ROC curves and KM curves of the risk model constructed from seven TCGA dataset genes (A), seven HCCDB18 dataset genes (B), and seven GSE76427 dataset genes (C).

Figure 8.

Performance Evaluation of Seven-gene Risk Models from TCGA, HCCDB18, and GSE76427 Datasets. A–C. ROC curves and KM curves of the risk model constructed from seven TCGA dataset genes (A), seven HCCDB18 dataset genes (B), and seven GSE76427 dataset genes (C).

Figure 9.

Association between RiskScore and Clinical Phenotypes and Biomarkers. A–F. Differences in risk scores across clinical phenotypes. Scatter plot demonstrating the correlation between CCP scores and RiskScore (G), between telomerase telomere extension scores and RiskScore (H), between hypoxia scores and RiskScore (I), and between angiogenesis scores and RiskScore (J). K. Heatmap depicting the correlation between immune cell infiltration predicted by CIBERSORT and RiskScore. ns, p ≥ 0.05; p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 9.

Association between RiskScore and Clinical Phenotypes and Biomarkers. A–F. Differences in risk scores across clinical phenotypes. Scatter plot demonstrating the correlation between CCP scores and RiskScore (G), between telomerase telomere extension scores and RiskScore (H), between hypoxia scores and RiskScore (I), and between angiogenesis scores and RiskScore (J). K. Heatmap depicting the correlation between immune cell infiltration predicted by CIBERSORT and RiskScore. ns, p ≥ 0.05; p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

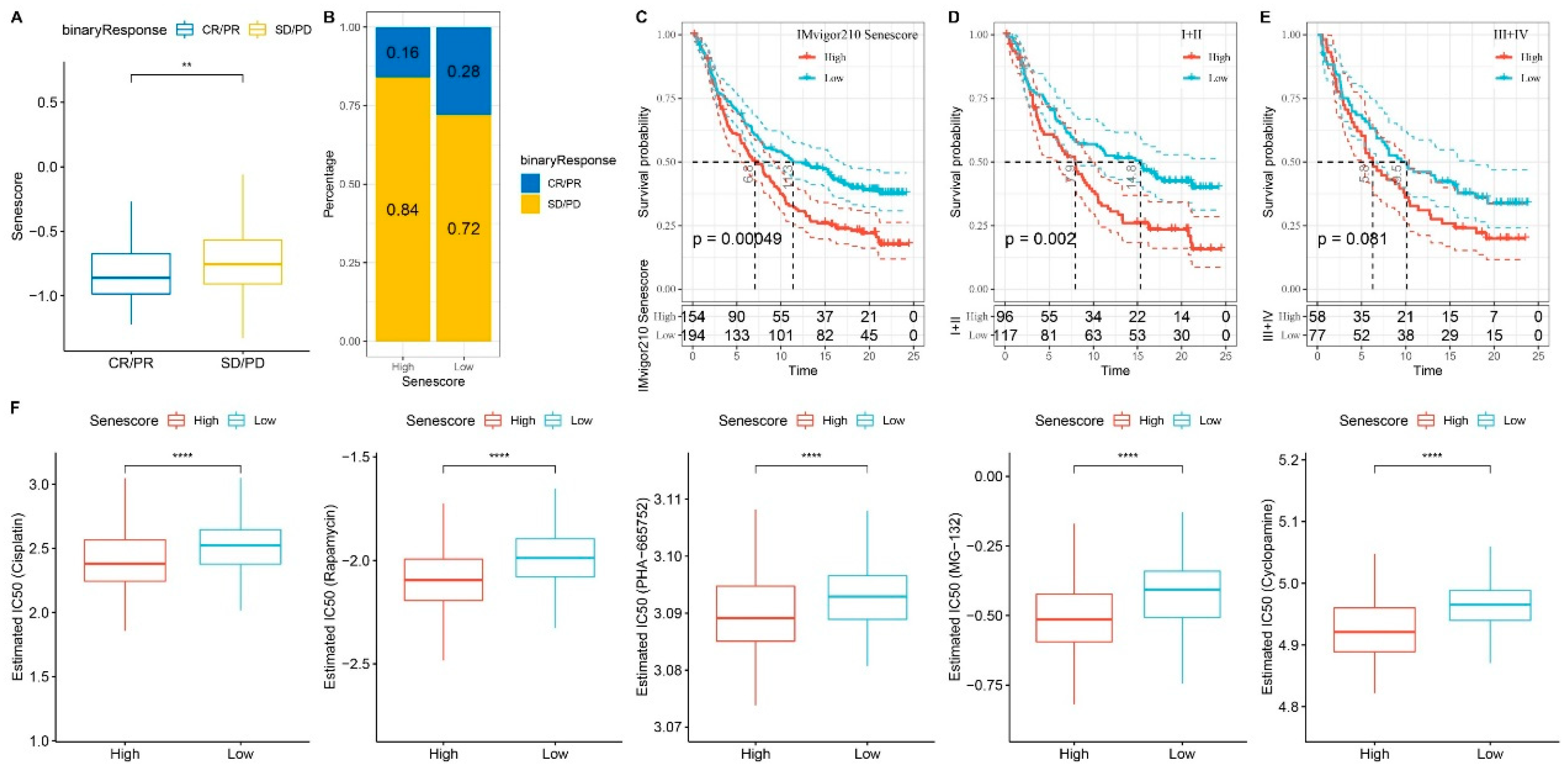

Figure 10.

Exploring RiskScore and its Influence on Immunotherapy and Drug Sensitivity. A. Differential RiskScore among immunotherapy responses. B. Distribution of immunotherapy response among RiskScore groups. C. Prognostic differences among RiskScore groups. Prognostic differences among RiskScore groups in early-stage patients (D) and advanced-stage patients (E). F. Differential drug sensitivity between high and low RiskScore groups in TCGA-LIHC cohort. **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 10.

Exploring RiskScore and its Influence on Immunotherapy and Drug Sensitivity. A. Differential RiskScore among immunotherapy responses. B. Distribution of immunotherapy response among RiskScore groups. C. Prognostic differences among RiskScore groups. Prognostic differences among RiskScore groups in early-stage patients (D) and advanced-stage patients (E). F. Differential drug sensitivity between high and low RiskScore groups in TCGA-LIHC cohort. **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001.

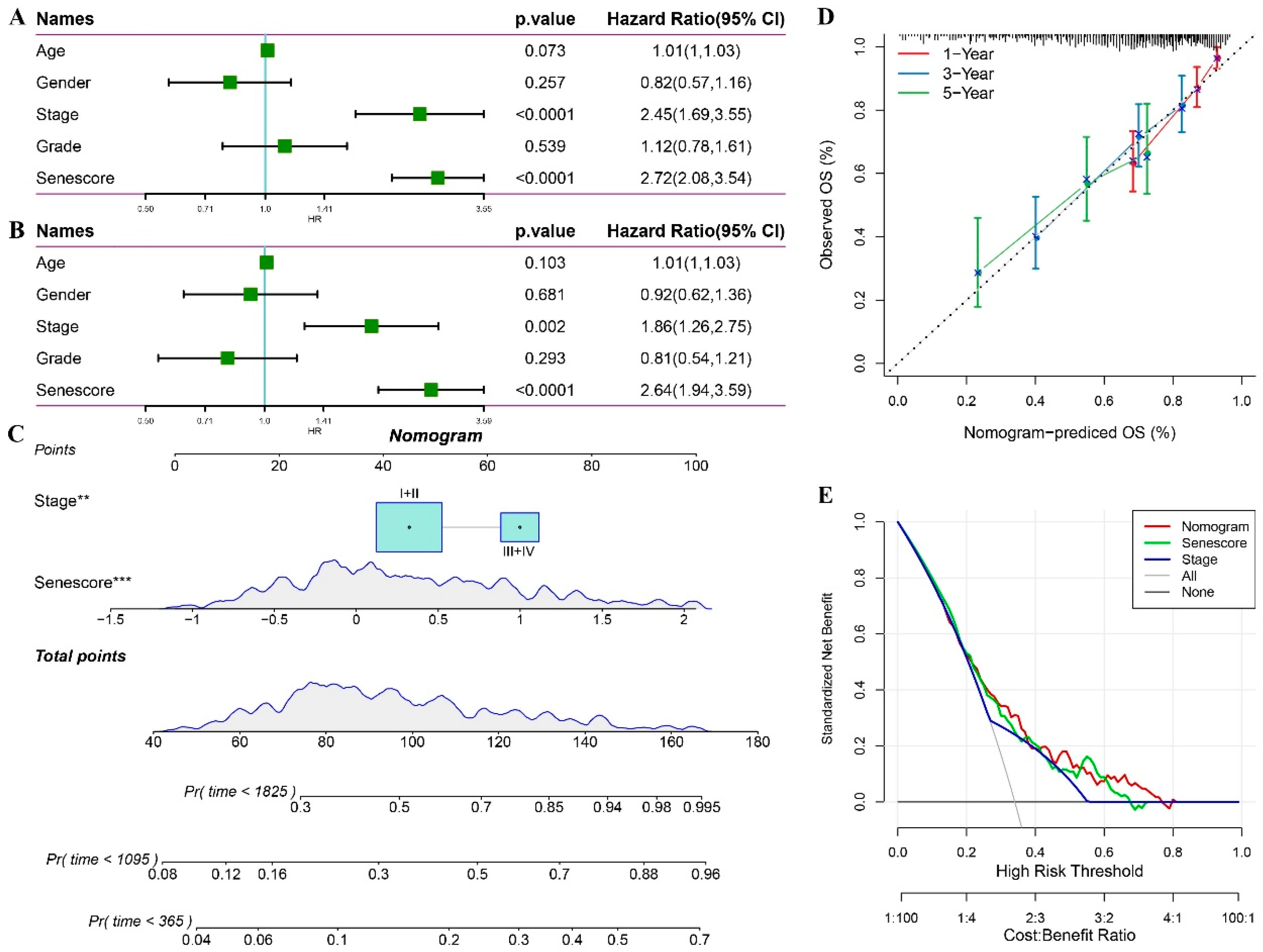

Figure 11.

Statistical Model Analysis of RiskScore and Clinical Clinicopathological Features. Univariate (A) and multivariate (B) Cox analyses of RiskScore and clinical pathological features. C. Nomogram model. D. Calibration curves of the nomogram at one, three, and five years. E. Nomogram decision curve. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Figure 11.

Statistical Model Analysis of RiskScore and Clinical Clinicopathological Features. Univariate (A) and multivariate (B) Cox analyses of RiskScore and clinical pathological features. C. Nomogram model. D. Calibration curves of the nomogram at one, three, and five years. E. Nomogram decision curve. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.